Abstract

Neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 are increasingly being recognised and can arise as a result of direct viral invasion, para-infectious or postinfectious immune mechanisms. We report a delayed presentation of COVID-19 postinfectious immune-mediated encephalitis and status epilepticus occurring in a 47-year-old woman 4 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 pulmonary disease. SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM antibodies were detected in her cerebrospinal fluid with features of encephalitis evident in both magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and electroencephalogram. She made a complete recovery following treatment with high-dose intravenous corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulins. Diagnosis of COVID-19 postinfectious encephalitis may prove challenging in patients presenting many weeks following the initial infection. A high index of clinical suspicion and testing intrathecal SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies are key to its diagnosis. Early immunotherapy is likely to result in a good outcome.

Keywords: COVID-19, Encephalitis, Postinfectious, SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), continues to rage-on in waves, with over 1.5 billion cases and 3.1 million deaths recorded globally from December 2019 to May 2021 [1]. Although predominantly a respiratory illness, COVID-19 has increasingly been recognised to cause disorders of the nervous system including encephalitis, encephalopathy, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, myelitis, Guillain–Barre syndrome, stroke, cerebral venous thrombosis and taste and smell dysfunction [2–4]. Neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 can arise as a result of direct invasion, para-infectious or postinfectious immune mechanisms. Encephalitis related to SARS-CoV-2 is rare and is reported to occur usually within the first 2 weeks following infection [2, 3]. We report a patient manifesting encephalitis as a delayed complication of COVID-19. To our knowledge, this is the first authenticated case of SARS-CoV-2-induced encephalitis reported as late as 28 days after the initial infection.

Case presentation

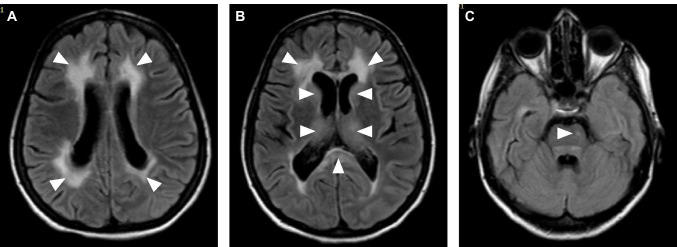

A 47-year-old Sri Lankan woman with a past history of uncomplicated type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with lower respiratory symptoms in early January 2021, which was confirmed to be due to COVID-19 based on positive viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests on nasal swabs and exclusion of other causes. She made an unremarkable recovery from the respiratory infection and returned home after 14 days. Twenty-eight days later, she developed gradual onset confusion and abnormal behaviour. There was no fever, headache or other significant neurological symptoms. Over the next 4 days, her symptoms worsened and she developed generalised seizures. On admission to hospital, she progressed into status epilepticus requiring assisted mechanical ventilation and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). She did not have meningism. Initial blood investigations including her haemoglobin, white cell counts, random blood glucose, liver function tests, creatinine and electrolytes were within normal limits while inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) were mildly elevated. Non-contrast-enhanced CT imaging of the brain showed bi-frontal white matter oedema. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed 10 lymphocytes/cumm, 5 polymorphs/cumm, normal protein and glucose concentrations. CSF viral PCR screening for Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, Japanese encephalitis, Varicella zoster and SARS-CoV-2 were negative. SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies were detected in CSF using a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Abbott). However, NMDAR, LGI1, CASPR2, AMPA1/2R and GABARA/B antibodies were not detected in her CSF. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain on the fifth day of admission revealed confluent T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensities in the periventricular white matter, mainly clustered around frontal and occipital horns. There was no restricted diffusion, contrast enhancement or haemorrhagic changes in these lesions (Fig. 1A). FLAIR hyperintensities were also noted in the splenium, basal ganglia and in the ventral pons (Fig. 1B and C). The electroencephalogram showed generalised slow wave discharges consistent with encephalitis.

Fig. 1.

Axial MRI of the brain showing confluent T2-FLAIR hyperintensities in the periventricular white matter mainly clustered around frontal and occipital horns (A) and (B), in the basal ganglia and splenium of the corpus callosum (B) and a focal hyperintensity in the pons (C)

She was initially treated with intravenous aciclovir until CSF test results were available. Intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days and intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days were administered when it was evident that she had a postinfectious encephalitis. Her seizures were treated with intravenous midazolam and levetiracetam. She made a remarkable recovery following the immunotherapy and antiseizure medication. She was weaned off the ventilator 5 days after completion of IVIg and discharged home 2 weeks later with only minor residual cognitive deficits.

Discussion

Neurological complications have been observed in up to 36% of hospitalised COVID-19 patients [5]. Encephalitis is a rare complication of SARS-CoV-2 and has been reported mostly as a para-infectious manifestation occurring within days to 2 weeks of the initial infection [2–4]. Our patient presented 28 days after PCR confirmed COVID-19 pulmonary disease with a gradual onset encephalitis that rapidly progressed to status epilepticus requiring intensive care management. Inflammatory changes on brain MRI, delta rhythm on electroencephalogram and lymphocytic pleocytosis on CSF analysis were consistent with the clinical diagnosis of encephalitis. Her recent COVID-19 pulmonary disease suggested SARS-CoV-2 as a likely aetiology and the detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies in her CSF in the absence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA coupled with a good response to immunotherapy strongly suggested the encephalitis in our patient to be a postinfectious immune-mediated manifestation of COVID-19.

The potential of coronavirus to cause delayed immune-mediated encephalitis has been demonstrated in murine models almost 40 years ago [6]. In humans, establishing SARS-CoV-2 as a cause of postinfectious encephalitis would always prove challenging, and more so, when it occurs as a delayed complication as in our patient. Indeed, in two previously reported cases, an immune-mediated mechanism was postulated without definitive evidence of intrathecal viral RNA or specific antibodies [7, 8]. Exclusion of other common aetiologies of encephalitis and evidence of SARS-CoV-2-specific intrathecal IgG and IgM antibodies in our patient authenticated SARS-CoV-2 as the cause of the postinfectious encephalitis fulfilling criteria for a definitive diagnosis [2]. Brain MRI abnormalities noted in our patient were consistent with imaging abnormalities previously reported in COVID-19 [9]. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis has been shown to trigger subsequent autoimmune encephalitis mediated by neuroglial surface antibodies [10] and CASPR2 antibodies have been reported in relation to COVID-19 [11]. None of the common encephalitogenic neuroglial surface binding antibodies were detected in the CSF of our patient.

Of the immune-mediated neuroinflammatory manifestations of COVID-19, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis appears to be the commonest and manifests at an average of 9 days post-infection [3]. Thus far, our patient is the presumptive first case of COVID-19 postinfectious encephalitis presenting with the longest delay of 4 weeks after the initial infection. Given that the mechanism of disease is immune-mediated, the viral genome was not detected in CSF. However, the PCR assay has not been validated for detection of SARS-CoV-2 in CSF and studies have shown that the viral genome is frequently undetectable in CSF [11].

As the pandemic continues to spread unabated and more and more people are infected worldwide, our case highlights the need to consider postinfectious encephalitis even in patients presenting after a protracted interval following COVID-19, the utility of detecting SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies in the CSF in establishing diagnosis and the favourable response to immunotherapy in such patients. It would be prudent to maintain a high index of suspicion of this treatment-responsive neurological complication given that many patients may have had asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic COVID-19.

Author contribution

All authors were involved in the care of the patient and contributed to the conception of this paper. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Thashi Chang and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not required for case reports.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

The participant has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Champika Gunawardhana, Email: champikagu@yahoo.com.

Geetha Nanayakkara, Email: geetha_nanayakkara@yahoo.com.

Dhanusha Gamage, Email: dhanusha.gamage@gmail.com.

Indika Withanage, Email: aiwithanage@yahoo.com.

Manjeewa Bandara, Email: manjeewa@gmail.com.

Chandima Siriwimala, Email: chandimarks@gmail.com.

Nipun Senaratne, Email: senaratnenipun@gmail.com.

Thashi Chang, Email: thashichang@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael BD, Easton A, Kneen R, Defres S, Sejvar J, Solomon T. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):767–783. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterson RW, Brown RL, Benjamin L, Nortley R, Wiethoff S, Bharucha T, Jayaseelan DL, Kumar G, Raftopoulos RE, Zambreanu L, Vivekanandam V, Khoo A, Geraldes R, Chinthapalli K, Boyd E, Tuzlali H, Price G, Christofi G, Morrow J, McNamara P, McLoughlin B, Lim ST, Mehta PR, Levee V, Keddie S, Yong W, Trip SA, Foulkes AJM, Hotton G, Miller TD, Everitt AD, Carswell C, Davies NWS, Yoong M, Attwell D, Sreedharan J, Silber E, Schott JM, Chandratheva A, Perry RJ, Simister R, Checkley A, Longley N, Farmer SF, Carletti F, Houlihan C, Thom M, Lunn MP, Spillane J, Howard R, Vincent A, Werring DJ, Hoskote C, Jäger HR, Manji H, Zandi MS. The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology: clinical, radiological and laboratory findings. Brain. 2020;143(10):3104–3120. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bridwell R, Long B, Gottlieb M. Neurologic complications of COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1549.e3–1549.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan. China JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe R, Wege H, ter Meulen V. Adoptive transfer of EAE-like lesions from rats with coronavirus-induced demyelinating encephalomyelitis. Nature. 1983;305(5930):150–153. doi: 10.1038/305150a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picod A, Dinkelacker V, Savatovsky J, Trouiller P, Guéguen A, Engrand N. SARS-CoV-2-associated encephalitis: arguments for a postinfectious mechanism. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):658. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukushima EFA, Nasser A, Bhargava A, Moudgil S. Postinfectious focal encephalitis due to COVID-19. Germs. 2021;11(1):111–115. doi: 10.18683/germs.2021.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kihira S, Delman BN, Belani P, Stein L, Aggarwal A, Rigney B, Schefflein J, Doshi AH, Pawha PS. Imaging features of acute encephalopathy in patients with COVID-19: a case series. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41(10):1804–1808. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armangue T, Spatola M, Vlagea A, Mattozzi S, Cárceles-Cordon M, Martinez-Heras E, Llufriu S, Muchart J, Erro ME, Abraira L, Moris G, Monros-Giménez L, Corral-Corral Í, Montejo C, Toledo M, Bataller L, Secondi G, Ariño H, Martínez-Hernández E, Juan M, Marcos MA, Alsina L, Saiz A, Rosenfeld MR, Graus F, Dalmau J, Spanish Herpes Simplex Encephalitis Study Group Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: a prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(9):760–772. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guilmot A, Maldonado Slootjes S, Sellimi A, Bronchain M, Hanseeuw B, Belkhir L, Yombi JC, De Greef J, Pothen L, Yildiz H, Duprez T, Fillée C, Anantharajah A, Capes A, Hantson P, Jacquerye P, Raymackers JM, London F, El Sankari S, Ivanoiu A, Maggi P, van Pesch V. Immune-mediated neurological syndromes in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. J Neurol. 2021;268(3):751–757. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10108-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Not applicable.