Abstract

Background

To explore the clinical manifestation, imaging examination, and serology of patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19) between China and overseas.

Methods

Ninety patients with COVID‐19 who admitted to Fuzhou Pulmonary Hospital from January 23, 2020, to May 1, 2020, were included in this retrospective study. They were divided into domestic group and overseas group according to the origin regions. The clinical manifestations, imaging examination, serology, treatment, and prognosis between the two groups were compared and analyzed.

Results

The clinical manifestations of patients in the two groups mainly included fever (83.1% and 47.4%), cough (62% and 31.6%), expectoration (47.9% and 31.6%), anorexia (28.2% and 47.4%), fatigue (21.1% and 10.5%), and dyspnea (22.5% and 0%). The main laboratory characteristics in the two groups were decreased lymphocyte count, increased lactate dehydrogenase, decreased oxygenation index, decreased white blood cell count, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and increased C‐reactive protein. The computed tomography (CT) examinations of chest showed bilateral and peripheral involvement, with multiple patch shadows and ground glass shadows. However, pleural effusions were rare.

Conclusion

Fever, cough, and dyspnea are more common in domestic cases than overseas cases. However, patients with COVID‐19 from overseas may have the symptoms of loss of taste and smell that domestic cases do not have.

Keywords: China, clinical characteristics, novel coronavirus pneumonia, overseas

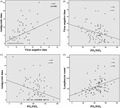

Correlation between clinical symptoms, oxygenation and prognosis in the two groups.

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19) has caused a major harm to global human health since its discovery in Wuhan, China in December 2019. 1 Chinese government has actively adopted a series of measures such as "quarantine, treatment, testing, and containment," which have basically blocked the spread of COVID‐19. 2 However, with the outbreak of overseas epidemics, many imported patients with COVID‐19 came to China. 3 At present, understanding of COVID‐19 is still in the primary stage. It is particularly important in disease prevention and control to fully understand the clinical characteristics and quickly diagnose COVID‐19 in order to achieve early diagnosis, early isolation, and early treatment. Therefore, we aimed to compare the clinical manifestations, imaging examination, and serology of patients with COVID‐19 between China and overseas.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Fuzhou Pulmonary Hospital. All patients signed the informed consent forms. A total of 90 patients with COVID‐19 who admitted to Fuzhou Pulmonary Hospital from January 23, 2020, to May 1, 2020, were included in this retrospective study. There were 42 males and 48 females, with the average age of (46.95 ± 17) years old (ranging from 19 to 93 years old). They were divided into domestic group (71 patients) and overseas group (19 patients) according to the origin regions.

2.2. Clinical diagnosis and classification criteria

The classification criteria were performed as the novel coronavirus pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan developed by the office of the National Health and Health Committee (revised version 7). 4 Diagnostic criteria for mild cases: the clinical symptoms were mild, and the imaging examination showed no pneumonia. Diagnostic criteria for common cases: There were fever, respiratory tract, and imaging examination manifestations of pneumonia. Diagnostic criteria for severe cases: those who met one of the following criteria. (a) There was shortness of breath, with breathing rate of ≥30 times/min; (b) In resting state, blood oxygen saturation was ≤93%; (c) PaO2/FiO2 was ≤300 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa); (d) Imaging examination of the lung showed that the lesions were significantly progressed up to >50% within 24–48 h. In areas with high altitude (over 1000 meters above sea level), PaO2/FiO2 should be corrected according to the following formula: PaO2/FiO2 × (Atmospheric pressure [mmHg]/760). Diagnostic criteria for critical cases: those who met one of the following criteria. (a) Respiratory failure occurred and mechanical ventilation was required; (b) Shock occurred; (c) other organ failure occurred and ICU monitoring and treatment were required.

2.3. Nucleic acid testing

Throat swabs and sputum were collected. RT‐PCR was performed to detect the nucleic acid with SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleic acid testing reagent kit (Sun Yat‐sen University Da'an gene Co., Ltd.) according to the instructions.

2.4. Observation indexes

The clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging examination, treatment methods, and outcomes were observed and recorded.

2.5. Statistical analysis

SPSS19.0 statistical software is used for statistical analysis. Counting data are expressed as the number of cases or percentage and compared by chi‐square test. Measurement data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared by independent sample t test when conforming to the normal distribution. Measurement data are expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared by rank sum test when they do not fit the normal distribution. p < 0.05 is considered as the statistically significant differences.

3. RESULTS

3.1. General clinical characteristics in the two groups

A total of 71 patients were included in the domestic group, including 34 males and 37 females, aged from 19 to 93 years, with a median age of 46.7 years. Their basic diseases mainly included hypertension (18.3%), respiratory diseases (11.3%), and tumor (9.9%). A total of 19 patients were included in the overseas group, including 8 males and 11 females, aged from 20 to 70 years, with a median age of 46.1 years. Their basic diseases were mainly hypertension (26.3%), respiratory diseases (21.1%), tumor (21.1%), diabetes mellitus (15.8%), and kidney disease (15.8%). There was no significant difference in basic characteristics between the two groups (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

General clinical characteristics between the two groups

| Clinical characteristics |

Domestic group (n = 71) |

Overseas group (n = 19) |

t/z/χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic data | ||||

| Male | 34/71 (47.9%) | 8/19 (42.1%) | 0.201 | 0.654 |

| Age (years) | 46.7 ± 17.6 | 46.1 ± 16.7 | 0.136 | 0.892 |

| BMI | 23.63 ± 3.2 | 22.2 ± 2.7 | 1.659 | 0.101 |

| Basic diseases | ||||

| None | 33/71 (46.5%) | 7/19 (36.8%) | 0.564 | 0.604 |

| Respiratory diseases | 8/71 (11.3%) | 4/19 (21.1%) | 1.242 | 0.271 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5/71 (7.0%) | 3/19 (15.8%) | 1.416 | 0.234 |

| Hypertension | 13/71 (18.3%) | 5/19 (26.3%) | 0.600 | 0.438 |

| Heart disease | 2/71 (2.8%) | 0/19 (0%) | — | 1.000 |

| Tumors | 7/71 (9.9%) | 4/19 (21.1%) | 1.751 | 0.186 |

| Mental diseases | 3/71 (4.2%) | 0/19 (0%) | — | 1.000 |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | 10/71 (14.1%) | 2/19 (10.5%) | 0.164 | 0.685 |

| Kidney disease | 6/71 (8.5%) | 3/19 (15.8%) | 0.897 | 0.344 |

| Nervous system | 5/71 (7.0%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | 0.076 | 0.782 |

3.2. The clinical manifestations in the two groups

The clinical manifestations in the two groups were shown in Table 2. In the domestic group, the main symptoms were fever, cough, expectoration, anorexia, dyspnea, fatigue, diarrhea, and chills. Other symptoms included chest tightness, dizziness, sore body, sore throat, stuffy nose, and runny nose. In the overseas group, the incidences of dyspnea, cough, fever, and total respiratory symptoms were less than those in the domestic group (p < 0.05). Moreover, patients in the overseas group had the symptoms of losses of taste and smell, while those in the domestic group did not have. The other main symptoms in the overseas group were the same as those in the control group.

TABLE 2.

The clinical manifestations in the two groups

| Clinical manifestations |

Domestic group (n = 71) |

Overseas group (n = 19) |

t/z/χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | 44/71 (62%) | 6/19 (31.6%) | 5.607 | 0.018 |

| Expectoration | 34/71 (47.9%) | 6/19 (31.6%) | 1.615 | 0.204 |

| Hemoptysis | 2/71 (2.8%) | 0/19 (0%) | — | 1.000 |

| Dyspnea | 16/71 (22.5%) | 0/19 (0%) | 0.019 | |

| Chest tightness | 7/71 (9.9%) | 2/19 (10.5%) | 0.007 | 0.931 |

| Fever | 59/71 (83.1%) | 9/19 (47.4%) | 10.361 | 0.001 |

| Dizzy | 6/71 (8.5%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | 0.212 | 0.645 |

| Weakness | 15/71 (21.1%) | 2/19 (10.5%) | 1.099 | 0.294 |

| Anorexia | 20/71 (28.2%) | 9/19 (47.4%) | 2.53 | 0.112 |

| Loss of taste and smell | 0/71 (0) | 2/19 (10.5%) | ||

| Nausea | 0/71 (0) | 1/19 (5.3%) | — | 0.211 |

| Abdominal pain | 1/71 (1.4%) | 0/19 (0%) | — | 1.000 |

| The whole body aches | 4/71 (5.6%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | 0.004 | 0.950 |

| Nasal congestion | 2/71 (2.8%) | 0/19 (0%) | — | 0.226 |

| Runny nose | 3/71 (4.2%) | 0/19 (0%) | — | 1.000 |

| Fear of cold and shivering | 9/71 (12.7%) | 4/19 (21.1%) | 0.851 | 0.356 |

| Complicated with respiratory symptoms | 3/71 (4.2%) | 3/19 (15.5%) | 3.221 | 0.073 |

| Proportion of severe and critical illness | 66/71 (93.1%) | 12/19 (63.2%) | 11.519 | 0.001 |

3.3. The laboratory and imaging examinations in the two groups

The main laboratory features in the domestic group and overseas group were decreased lymphocyte count (46.5% and 52.5%), increased lactate dehydrogenase (88.7% and 73.7%), decreased oxygenation index (15.5% and 5.3%), decreased white blood cell count (12.7% and 31.6%), increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (69.0% and 47.4%), and increased C‐reactive protein (47.9% and 36.8%) (Table 3). Moreover, the chest computed tomography (CT) examinations in the two groups were mainly bilateral and peripheral involvement, with multiple ground glass shadow, patchy shadow, and consolidation shadow. However, pleural effusions were rare.

TABLE 3.

The laboratory and imaging examinations in the two groups

| Clinical manifestations |

Domestic group (n = 71) |

Overseas group (n = 19) |

t/z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood gas analysis | ||||

| PH | 7.40 ± 0.036 | 7.40 ± 0.032 | −0.56 | 0.577 |

| PO2 | 106.61 ± 28.51 | 99.21 ± 18.82 | 1.117 | 0.267 |

| PCO2 | 34.33 ± 4.29 | 35.87 ± 4.61 | −1.419 | 0.159 |

| PO2/FiO2 | 442.70 ± 144.70 | 456.38 ± 93.90 | −0.512 | 0.611 |

| SO2 | 97.8 (97.1–98.5) | 97.7 (96.3–98.4) | −0.883 | 0.377 |

| Routine blood test | ||||

| WBC | 5.86 ± 2.36 | 4.58 ± 1.45 | 2.366 | 0.02 |

| NEUT | 4.02 ± 1.71 | 2.88 ± 1.01 | 3.799 | 0.000 |

| NEUT% | 0.68 ± 0.12 | 0.62 ± 0.10 | 1.292 | 0.057 |

| LY% | 0.23 ± 0.11 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | −1.11 | 0.243 |

| LY | 1.13 (0.81–1.62) | 1.11 (0.76–1.69) | −0.018 | 0.985 |

| Monocyte | 0.39 ± 0.19 | 0.38 ± 0.13 | 0.167 | 0.868 |

| HGB | 134.64 ± 21.50 | 133.52 ± 13.59 | 0.224 | 0.823 |

| PLT | 209.06 ± 65.47 | 182.24 ± 63.32 | 0.965 | 0.1 |

| ESR | 37.45 ± 26.95 | 20.52 ± 14.09 | 3.815 | 0.000 |

| CRP | 9.57 (3.94–27.98) | 4.04 (0.84–12.55) | −2.288 | 0.022 |

| PCT | 0.04 (0.02–0.07) | 0.027 (0.02–0.41) | −1.83 | 0.067 |

| D‐Dimer | 0.051 (0.019–0.199) | 0.019 (0.019–0.13) | −0.964 | 0.335 |

| GLB | 28.5 (26.5–30.6) | 26.1 (25.3–29.5) | −1.967 | 0.049 |

| BUN | 3.9 (3.0–4.5) | 3.5 (2.4–3.9) | −1.673 | 0.094 |

| CREA | 61.7 (52–75.5) | 53 (44.5–66.5) | −1.668 | 0.095 |

| CK | 60.5 (38.2–130) | 75.3 (58.2–105) | −0.763 | 0.446 |

| CK‐MB | 0.88 (0.53–1.51) | 1.05 (0.71–1.55) | −0.836 | 0.403 |

| TNT | 5.03 (3.52–7.41) | 5.72 (3.8–9.37) | −0.718 | 0.473 |

| MYO | 23.11 (21–49.48) | 21 (21–36.51) | −1.317 | 0.188 |

| Mg | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | −1.905 | 0.057 |

| Decreased oxygenation | 11/71 (15.5%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | 1.357 | 0.244 |

| Leukopenia | 9/71 (12.7%) | 6/19 (31.6%) | 3.856 | 0.05 |

| Lymphocytopenia | 33/71 (46.5%) | 10/19 (52.5%) | 0.227 | 0.797 |

| CRP | 34/71 (47.9%) | 7/19 (36.8%) | 0.391 | |

| ESR | 49/71 (69%) | 9/19 (47.4%) | 0.08 | |

| Increased LDH | 63/71 (88.7%) | 14/19 (73.7%) | 2.747 | 0.097 |

| Imaging features | ||||

| Bilateral pneumonia | 65/71 (91.5) | 15/19 (78.9%) | 2.41 | 0.121 |

| Multiple patchy shadows and ground glass shadows | 47/71 (66.2%) | 12/19 (63.2) | 0.061 | 0.804 |

| Peripheral pneumonia | 42/71 (59.2%) | 10/19 (52.6%) | 0.261 | 0.613 |

| Interstitial lesions | 42/71 (59.2%) | 12/19 (63.2%) | 0.100 | 0.752 |

| Ground glass opacity | 47/71 (66.2%) | 13/19 (68.4%) | 0.033 | 0.855 |

| Multiple plaques | 64/71 (90.1%) | 17/19 (89.5%) | 0.007 | 0.931 |

| Multiple exudates | 59/71 (83.1%) | 17/19 (89.5%) | 0.464 | 0.496 |

| Nodular shadow | 43/71 (60.6%) | 12/19 (63.2%) | 0.042 | 0.837 |

| Pleural effusion | 6/71 (8.5%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | 0.212 | 0.645 |

Abbreviation: ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; WBC, White blood cell; NEUT, Neutrophils; LY, lymphocyte; HGB, Hemoglobin; PLT, platelet; CRP, C‐reactive protein; PCT, Procalcitonin; GLB, Globulin; BLUN, Blood urea nitrogen; CREA, creatinine; CK, creatine kinase; CK‐MB, creatine kinase isoenzyme; TNT, Troponin T; MYO, myoglobin; CRP, C‐reactive protein; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

3.4. Clinical treatment and prognosis in the two groups

As shown in Table 4, the prognosis of the domestic group was not consistent with that of the overseas group. The time of turning negative was longer in the overseas group than that in the domestic group (p < 0.05). Moreover, the time of abatement of fever was also longer in the overseas group than that in the domestic group (p < 0.05).

TABLE 4.

Clinical treatment and prognosis in the two groups

| Clinical treatment and prognosis |

Domestic group (n = 71) |

Overseas group (n = 19) |

t/z/χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||||

| Use of antibiotics | 25/71 (35.2%) | 6/19 (31.6%) | 0.088 | 0.522 |

| Use of hormones | 10/71 (14.1%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | 1.087 | 0.2297 |

| Oxygen supply | 34/71 (47.9%) | 7/19 (36.8%) | 0.737 | 0.397 |

| Prognosis | ||||

| Time of turning negative | 12 ± 5 | 18 ± 6 | −3.946 | 0.000 |

| Antipyretic time | 3 (0–8) | 7.5 (3–11) | −1.616 | 0.106 |

3.5. Correlation between clinical symptoms, oxygenation, and prognosis in the two groups

There was a significant correlation between antipyretic time and virus negative time (Figure 1A). There was a significant correlation between virus negative time and oxygenation (Figure 1B). Moreover, there was a significant correlation between antipyretic time and oxygenation (Figure 1C). There was also a significant correlation between lymphocyte count and oxygenation (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Correlation between clinical symptoms, oxygenation, and prognosis in the two groups

4. DISCUSSION

Coronaviruses are a large class of viruses widely existing in nature. The newly discovered 2019‐nCoV is the seventh known coronavirus to infect human. 5 , 6 2019‐nCoV has caused a considerable number of infections and deaths in China and overseas and has become a worldwide public health emergency to an increasing degree. In this study, we compared the clinical manifestation, imaging examination, and serology of patients with COVID‐19 between domestic and overseas. We found that the clinical characteristics of domestic cases are similar to those of overseas cases. Fever, cough, and dyspnea were more common in domestic cases than in overseas cases. However, overseas patients with COVID‐19 may have the symptoms of loss of taste and smell that domestic cases did not have. The time of nucleic acid test turning negative in overseas cases was longer than that in domestic cases.

A recent study has shown that patients with severe and critical COVID‐19 have a high mortality rate, and the occurrence of ARDS or MODS greatly increases its mortality. 7 In this study, most of the 64 patients with severe COVID‐19 were complicated with hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other basic diseases. Respiratory symptoms were the main clinical manifestations when they sought medical advice. It is reported in the literature that NCP infection is mainly male. 8 However, in this study, the patients in the two groups were mainly female. It may be related to the small sample size and the large number of female patients in our hospital. The proportion of severe and critical patients in the domestic group was higher than that in the overseas group, suggesting that the detection of domestic cases in early stage was later. Moreover, compared with the domestic group, the proportion of the elderly over 60 years old in the overseas group was less.

Our results suggest that fever, cough, cough and fatigue are the main clinical symptoms in both domestic and overseas groups. A few patients may have systemic toxicity symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms and so on. However, the proportion of patients with dyspnea in the domestic group is significantly higher than that in the overseas group, which may be related to the higher proportion of severe and critical patients in the domestic group. The incidences of cough, fever, and respiratory symptoms in domestic group are higher than those in overseas group. Patients with COVID‐19 are in critical condition and the conditions progress rapidly, so they should be identified and treated as soon as possible. Furthermore, the patients in the overseas group have the loss of smell and taste, which may be related to the different subtypes of COVID‐19, resulting in the different symptoms.

Risk factors, including neutrophil count, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, creatine kinase, and blood urea nitrogen, can help to early screen critically ill patients with COVID‐19 of poor prognosis. 9 Our results also show that the main laboratory features in the two groups include decreased lymphocyte count, decreased leukocyte count, decreased oxygenation, increased lactate dehydrogenase, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased C‐reactive protein. Those results are similar with the previous study. 8 However, compared with the overseas group, the values of ESR and CRP in the domestic group are significantly higher. Chest CT examination is an important means for screening and evaluating lung disease. Imaging examination suggests that the main part of the lesion involved in the patients with COVID‐19 is the periphery of the lungs, followed by the periphery and the center at the same time, and a few of them simply involve the center. The image properties in the two groups are mostly ground glass and solid shadows. Our results suggest that the chest CT examinations in the two groups are mainly bilateral and peripheral involvement, with multiple ground glass shadow, patchy shadow, and consolidation shadow. However, pleural effusions are rare. Those imaging examinations are also similar with the previous studies. 10 , 11

Our results show that the prognosis of patients in the domestic group and the overseas group is inconsistent. Compared with the patients in the domestic group, patients in the overseas group have a longer time to turn negative. In addition, the correlation analysis of clinical symptoms, oxygenation, and prognosis is carried out on 90 patients. The antipyretic time is significantly correlated with the virus negative time, and the virus negative time is notably associated with oxygenation. It has been reported that the SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleic acid test may still be positive in convalescent patients, but most of the re‐positive patients have no deterioration in lung CT. 12 , 13 Continuous isolation and close follow‐up of convalescent patients can inhibit the recurrence and spread of COVID‐19.

There are also some limitations in this study. This study is a retrospective single‐center study with small sample size and lack of more detailed epidemiological information (such as treatment measures and prognosis). We will continue to follow up and expand the sample size and conduct multi‐center studies for further verification.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the clinical characteristics of domestic group and overseas group are similar, but the symptoms of dyspnea in domestic group are more than those in overseas group. However, the clinical manifestations of patients with COVID‐19 are not characteristic, so it is necessary to be vigilant for patients with atypical epidemiological and clinical characteristics. At the time of admission to confirm the diagnosis and discharge from the hospital to judge the condition, the negative virus nucleic acid test of the throat swab sample is used as the criterion to cure, which also needs to be careful to avoid misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis. Furthermore, COVID‐19 should be more quickly and accurately diagnosed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Funding information

This study was supported by the Special Project for COVID‐19 prevention and Control in Fuzhou in 2020 (2020‐XG‐20).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kannan S, Shaik Syed Ali P, Sheeza A, Hemalatha K. COVID‐19 (Novel Coronavirus 2019) ‐ recent trends. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(4):2006‐2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu X, Li N. How Did Chinese government implement unconventional measures against COVID‐19 pneumonia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:491‐499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xu T, Chen C, Zhu Z, et al. Clinical features and dynamics of viral load in imported and non‐imported patients with COVID‐19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:68‐71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chinese Research Hospital Association; Respiratory Council . Expert recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of interstitial lung disease caused by novel coronavirus pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2020;43(10):827‐833.Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wenfu Z, Junmei He, Jinfeng Tie, et al. Resistance and disinfection of coronavirus. Chin J Disinfect. 2020;1:1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shi M, Chen L, Yang Y, et al. Analysis of clinical features and outcomes of 161 patients with severe and critical COVID‐19: a multicenter descriptive study. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(9):e23415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen X, Yan L, Fei Y, Zhang C. Laboratory abnormalities and risk factors associated with in‐hospital death in patients with severe COVID‐19. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(10):e23467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhu H, Fu L, Jin Y, et al. Clinical features of COVID‐19 convalescent patients with re‐positive nucleic acid detection. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(7):e23392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao G, Su Y, Sun X, et al. A comparative study of the laboratory features of COVID‐19 and other viral pneumonias in the recovery stage. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(10):e23483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.