Abstract

Background

The Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group is supporting two hospitals in Ghana to develop antimicrobial stewardship. Early intelligence gathering suggested that surgical prophylaxis was suboptimal. We reviewed the evidence for use of surgical prophylaxis to prevent surgical site infections (SSIs) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to inform this work.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane, CINAHL and Google Scholar were searched from inception to 17 February 2020 for trials, audits, guidelines and systematic reviews in English. Grey literature, websites and reference lists of included studies were searched. Randomized clinical trials reporting incidence of SSI following Caesarean section were included in two meta-analyses. Narrative analysis of studies that explored behaviours and attitudes was conducted.

Results

This review included 51 studies related to SSI and timing of antibiotic prophylaxis in LMICs. Incidence of SSI is higher in LMICs, infection surveillance data are poor and there is a lack of local guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis. Education to improve appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis is associated with reduction of SSI in LMICs. The random-effects pooled mean risk ratio of SSI in Caesarean section was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.51–1.17) for pre-incision versus post-incision prophylaxis and 0.89 (95% CI: 0.55–1.14) for short versus long duration. Reduction in cost and nurse time was reported in shorter-duration surgical antibiotic prophylaxis.

Conclusions

There is scope for improvement, but interventions must include local context and address strongly held beliefs. Establishment of local multidisciplinary teams will promote ownership and sustainability of change.

Introduction

Antimicrobial stewardship programmes (ASPs) commonly include the use of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to surgical procedures as a key area for improvement.1,2 In addition to reducing the incidence of infection, appropriate prophylaxis contributes to the control of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). In the UK and other high-income countries, guidance on use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis (SAP) to reduce surgical site infections (SSIs) has been in place for many years and the recommendation to use a single dose within 1 h of surgery3 has become routine practice. The ‘Start smart—then focus’ resource4 provides a useful algorithm for SAP together with a summary of components for best practice. In Scotland, SAP has been the focus of improvement work for the Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group (SAPG)5 and associated quality indicators have been used to drive improvements in practice.6

Through research collaborations with teams in African countries and through reviews of global point prevalence studies, we were aware that practice varies considerably from that recommended by WHO.3,7 Recent audits and point prevalence studies in Benin, Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Turkey confirm continued high occurrence of the use of multiple-dose SAP administered for >1 day, which is likely to exacerbate AMR.8–16

In 2019, SAPG received a Commonwealth Partnerships for Antimicrobial Stewardship grant from the Fleming Fund to support partners in two hospitals in Ghana to develop ASPs. This work included data gathering via point prevalence surveys,17 development and delivery of multi-professional education aimed at increasing knowledge and optimizing behaviours and supporting quality improvement interventions. Initial intelligence gathering suggested that antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent SSI was suboptimal, with extended durations of antibiotics common.17 The objective of this scoping review was to inform our approach to supporting change in this area. We reviewed the evidence on the duration of SAP and related incidence of SSI in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) including staff behaviours and attitudes to provide guidance. We are aware that cultural and contextual issues are important for influencing antimicrobial prescribing in LMICs.18

Methods

This scoping review and meta-analysis is reported in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual.19

Inclusion criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were included: all study designs that reported SAP in LMICs or developing countries as measured by SSI in patients undergoing any surgical procedure and studies that discussed clinicians’ perceptions and practices regarding the use of SAP.

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to find both published and unpublished studies. A systematic search of published literature in MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane, CINAHL and Google Scholar from inception to 17 February 2020 was undertaken for trials, audits, guidelines and systematic reviews. The search was limited to studies published in English and involving human subjects. Grey literature, websites and reference lists of included studies were also searched for completeness. Key words and index terms were: antibiotics OR antibiotic prophylaxis; surgical site infection; low-income countries OR middle-income countries; Africa OR (individually named countries). The Medline search strategy is provided in Appendix S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online).

Two authors (L.C. and J.S.) screened all titles and abstracts identified. Full text was obtained for all relevant abstracts and those not satisfying the inclusion criteria were removed. All remaining studies were included in this review in accordance with the aim of scoping reviews to determine the extent of literature on the topic and are reported in accordance with JBI scoping review guidelines.19

Assessment of methodological quality

Publications selected for critical appraisal were assessed independently by two reviewers (L.C. and J.S.) for methodological validity using the standardized critical appraisal instrument from the JBI Meta-analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_RCTs_Appraisal_tool2017_0.pdf). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or a third reviewer (R.A.S.).

Data extraction and data synthesis

Study data were extracted onto a customized form that included study characteristics, interventions, outcomes and recommendations.

Two meta-analyses were conducted using Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3. Primary statistics were extracted from studies to calculate risk ratios for the association of (i) timing or (ii) treatment duration of SAP and incidence of SSI.

Results

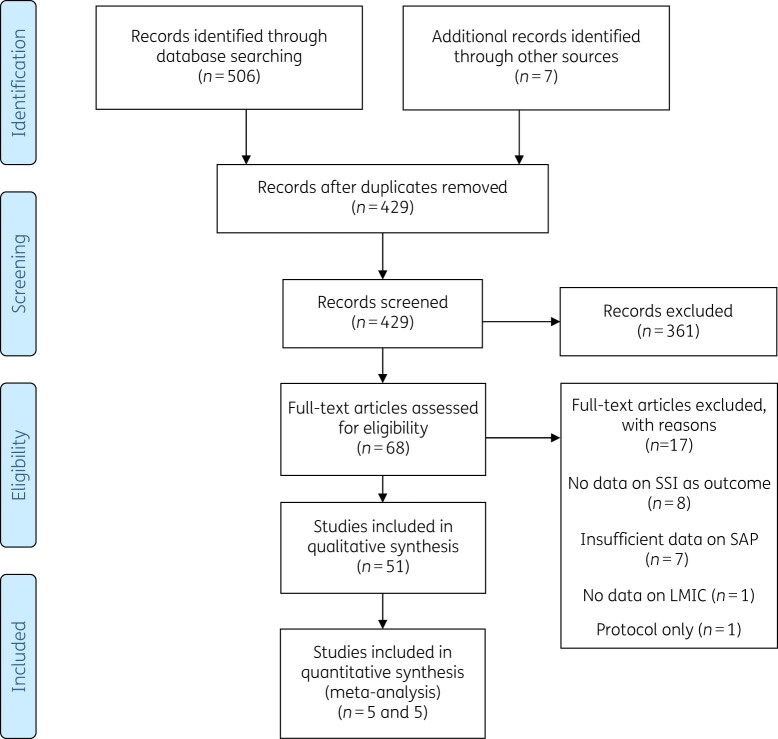

The detailed search results are reported in Figure 1. Of the initial 423 publications identified, full text was retrieved for 68 potentially relevant studies and 51 are included in this review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

Key characteristics and findings of the studies are summarized in Table 1. Publications in this review include 3 reviews, 15 randomized clinical trials (RCTs), 25 prospective studies, 5 retrospective studies, 1 cross-sectional study, 1 survey and 1 qualitative study.

Table 1.

Included studies

| Author/date | Study characteristics | Intervention and findings | Conclusions/recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

|

WHO3 2016 (updated 2018) |

Guideline Global |

1. When SAP is indicated, recommend administration prior to surgical incision. Recommend the administration of SAP within 120 min before incision while considering the half-life of the antibiotic. 2. Strong recommendation against the prolongation of SAP administration after completion of the operation for the purpose of preventing SSI. |

1. Recommendation was based on systematic review of timing of antibiotic administration prior to incision. 2. Recommendation based on meta-analysis of 44 RCT. |

| Allegranzi et al.38 2011 |

Systematic review and meta-analysis International |

SSI was the leading infection in hospitals in developing countries: 5.6 per 100 surgical procedures. Much higher than in developed countries (USA 2.6%; Europe 2.9%). Call for improvements in surveillance and infection control practices. |

WHO-funded review. 220 studies included (57 focused on SSI). HAI is poorly recorded in Africa. |

| Aiken et al.30 2012 |

Systematic review Sub-Saharan Africa |

Review and synthesis of interventions that had been tested in sub-Saharan Africa to reduce the risk of SSI. 24 studies included from Nigeria (n = 8), South Africa (n = 5), Côte d’Ivoire (n = 2), Kenya (n = 2), Tanzania (n = 2) Uganda (n = 2). One study included from each of Ethiopia, Ghana and Mozambique. Antibiotic prophylaxis was the most common intervention (n = 10). |

Authors’ conclusions: correct use of SAP (i.e. single dose, pre-op delivery) can, in some circumstances, lead to very dramatic reductions in the risk of SSI and can also reduce costs for the patient or institution. This goes directly against the widely held belief amongst African surgeons (in our experience) that ‘poor hygiene’ or crowding in their wards necessitates prolonged post-op antibiotic usage. |

| Ariyo et al.61 2019 |

Systematic review International |

Summary of implementation strategies to improve adherence to evidence-based interventions that reduce SSI. Studies were across high-income countries and LMICs (mostly high-income countries) Most studies used multifaceted approach (staff engagement, education, standardizing care delivery and evaluation). | Successful HAI prevention should be based on multifaceted strategies, including engagement, education, execution and evaluation. |

| Opoku69 2007 |

RCT Ghana |

320 women admitted for Caesarean section were randomized 1:1 to receive either triple therapy of ampicillin 1 g + metronidazole 500 mg + gentamicin 80 mg all given IV after cord clamping and repeated 12 h after first dose (Group 1) or co-amoxiclav 1.2 g given IV after cord clamping and repeated 12 h after first dose (Group 2). SSI were 13.1% in Group 1 and 3.7% in Group 2. |

In this study both groups had repeated doses of antibiotics administered post-op. Author concluded co-amoxiclav was superior but cost 4× the triple therapy, which may be a deterrent in low-income settings. |

| Dlamini et al.20 2015 |

RCT Uganda |

464 women admitted for emergency Caesarean section were randomized to receive same prophylactic antibiotic either within 1 h before incision or after incision. Patients in experimental group received prophylaxis 26.09 (SD 9.67) min before skin incision. Patients in control group received prophylaxis 13 (SD 12.93) min after incision. Overall infection in experimental group was 65.9% compared with 85.1% in control group (RR 0.77, CI 0.62–0.97) P = 0.022 | Overall high incidence rate of infection, but this was statistically significantly lower in experimental group. |

| Nitrushwa et al.28 2019 |

Conference abstract of RCT Rwanda |

301 women undergoing emergency Caesarean section were randomized to either one dose of 2 g ampicillin 15–60 min prior to skin incision (Group A, n = 147) or 2 g ampicillin prior to skin incision followed by 1 g ampicillin q8h over 72 h (Group B, n = 154). Participants were followed for 30 days. Results: SSI in Group A, n = 8 and SSI in Group B, n = 4 (P = 0.089). Overall infection rate was lower than expected (4%). | This study supports restricting use of extended antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce AMR as no statistically significant difference found in infection rate between groups. |

| Mugisa et al.22 2018 |

RCT Uganda |

174 women undergoing elective Caesarean section were randomized to either one dose of 2 g ceftriaxone IV + 500 mg metronidazole IV 30–60 min before operation (n = 87) or one dose of 1 g ceftriaxone IV + 500 mg metronidazole during the Caesarean section followed by 1 g ceftriaxone IV daily + 500 mg metronidazole IV q8h for 3 days. Following discharge, metronidazole 400 mg q8h and Ampiclox 500 mg q8h for 5 days. Participants were followed up for 14 days for indicators of infection. Results: incidence of post-op wound infection in single-dose group was 1.3% and in the multiple-dose arm was 2.4% (RR: 1.895; 95% CI 0.2–21.4), P = 0.605. |

Common practice at the time of the study was to give multiple doses of antibiotics for 3–7 days post-op. Study concluded that single-dose therapy of metronidazole and ceftriaxone was as effective as multiple doses in the prevention of post-op wound infection and recommends use of single-dose prophylaxis. |

| Kayihura et al.21 2003 |

Cost–benefit RCT Mozambique |

Women (n = 288) with indication for emergency Caesarean section were randomly allotted to two groups. Group 1 (n = 143) received the single, combined dose of prophylactic antibiotics (160 mg gentamicin and metronidazole IV given before incision) and Group 2 (n = 145) received, over 7 days, the post-op standard scheme of antibiotics (crystalline penicillin 4 000 000 UI IV q6h and metronidazole 500 mg IV q8h during the first 24 h; erythromycin 500 mg q6h orally and metronidazole 500 mg q8h orally for 6 days). Outcome measures: post-op infection, measured at Day 7, mean hospital stay and costs of antibiotics used. Post-op infection rate was 5.2% in Group 1 and 6.4% in Group 2. Single-dose cost US$0.78; post-op scheme cost US$8.37. |

This study concluded that single-dose pre-op ampicillin was as effective as usual care but cost 1/10 of the price and saved on staff time. |

| Ahmed et al.25 2004 |

RCT Sudan |

n = 200 women undergoing planned Caesarean section randomly allocated to either 1 g ceftriaxone IV at induction of anaesthesia or 1 g ampicillin/cloxacillin IV q8h started at induction of anaesthesia. SSI: two cases endometriosis and one superficial wound infection in single-dose group compared with one case endometriosis and two superficial wound infections in multiple-dose group. | Single dose reduces nurse time and does not have statistically significant effect on SSI. |

| Agbugui et al.67 2014 |

RCT Benin |

n = 87 men undergoing transrectal prostate biopsy randomly allocated to either 500 mg ciprofloxacin q12h + 400 mg metronidazole q8h orally for 1 day starting 2 h prior to the procedure or 500 mg ciprofloxacin q12h + 400 mg metronidazole q8h orally for 5 days starting 2 h prior to the procedure. SSI: 8/42 had positive urine culture and/or fever at Day 1–3 in 1 day group compared with 7/45 in 5 day group. | No significant difference between short- and long-term prophylactic regimens. |

| Lyimo et al.27 2013 |

RCT Tanzania |

n = 500 women undergoing emergency Caesarean section randomly allocated to either single dose of gentamicin (3 mg/kg) plus metronidazole (500 mg) given 30–60 min before incision or multiple doses of gentamicin (3 mg/kg) plus metronidazole (500 mg) given 30–60 min before incision then followed by gentamicin (3 mg/kg) once a day and metronidazole (500 mg) q8h for 24 h post-op. 4.8% of patients in single-dose group developed SSI by 30 days compared with 6.4% in multiple-dose group. | Between-group difference of 1.6% was not statistically equivalent therefore single dose should be used and is more cost-effective. |

| Osman et al.23 2013 |

RCT Sudan |

n = 180 women undergoing elective Caesarean delivery randomly allocated to either 1 g ceftizoxime single dose 40 min pre-incision or 1 g ceftizoxime single dose post-cord clamping. 6.7% of patients in pre-incision group developed superficial wound infection compared with 3.3% in post-cord-clamping group. | No significant between group difference—either regimen effective. |

| Reggiori et al.24 1996 |

RCT Uganda |

n = 479 patients inguinal hernia repair; n = 250 women ectopic pregnancy; n = 177 total abdominal hysterectomy; n = 194 elective and emergency Caesarean section randomly allocated to either: hernia or ectopic pregnancy, single-dose ampicillin 2 g 30 min before incision; hysterectomy or Caesarean section, ampicillin 3 g + metronidazole 500 mg IV at induction of anaesthesia (single-dose groups); or hernia or ectopic pregnancy, IM fortified procaine penicillin 1–2 megaunits daily for 7 days starting ∼3 h after surgery; hysterectomy or Caesarean section, benzylpenicillins 1 megaunit IV q6h for 1 day starting ∼3 h after surgery then IM fortified procaine penicillin 1–2 megaunits daily for 6 days (multiple-dose groups). Infective complications were 0% in hernia repair, 2.4% in ectopic pregnancy, 3.4% in hysterectomy and 15.2% in Caesarean section for single-dose groups compared with 7.5% hernia repair, 10.7% ectopic pregnancy, 20% hysterectomy and 38.2% Caesarean section in multiple-dose groups. | All differences in infection rates were statistically significant. Pre-operative prophylaxis reduced infection, length of hospital stay and cost. |

| Usang et al.66 2008 |

RCT Nigeria |

n = 88 children with 104 wounds undergoing unilateral or bilateral hernia repair as day case randomly allocated to either single-dose gentamicin at 2 mg/kg body weight administered at induction of anaesthesia or no treatment. There were 0 infections in the treatment group compared with 4.8% in the no-treatment group. | The statistically significant between-group difference (P = 0.041) suggests pre-op gentamicin has a role in the prevention of wound infection in this population. |

| Westen et al.29 2015 |

RCT Tanzania |

n = 176 women undergoing Caesarean section randomly allocated to either 1 g ampicillin and 500 mg metronidazole IV 20 min before Caesarean section or 1 g ampicillin and 500 mg metronidazole IV 20 min before Caesarean section + 500 mg ampicillin and 500 mg metronidazole IV at 8 and 16 h post-op followed by 500 mg amoxicillin and 400 mg metronidazole orally three times a day on Days 2–5. 6.7% developed wound infections up to 30 days in single-dose group compared with 10.3% in multiple-dose group. There were four cases of SSI in the treatment group compared with three cases in the control group. | Between-group difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.40), therefore single dose was shown to be non-inferior, cheaper and increased compliance. |

| Ijarotimi et al.26 2013 |

RCT Nigeria |

n = 200 women undergoing elective Caesarean section randomly allocated to either ampicillin/cloxacillin combination as four IV doses of 1 g immediately and 500 mg q6h and metronidazole as three IV doses of 500 mg q8h, both for 24 h, or same combination IV for 48 h and subsequent oral use for 5 days. | Short-term (24 h) course of ampicillin/cloxacillin and metronidazole was as effective as a long-term (7 day) course of same combination in preventing post-elective Caesarean section infection-related morbidity. It is cheaper, easier to administer and may also save nursing time. |

| Goranitis et al.70 2019 |

RCT International |

n = 3412 women undergoing surgical management of miscarriage randomly assigned to SAP or placebo. n = 158/3412 developed pelvic infection, 68 in SAP group and 90 in placebo group. | SAP was effective and cost-effective in low-income countries. |

| Osuigwe et al.68 2006 |

RCT Nigeria |

n = 289 children undergoing clean day-case surgery were randomly allocated to received Ampiclox IV on induction and 6 h post-op + oral for 5 days and vitamin B complex or vitamin B complex only. SSI: 5.1% in experimental and 4.3% in control groups. | SAP not necessary for clean surgery. Omitting SAP would reduce cost of surgery. |

| Weinberg et al.65 2001 |

Segmented time-series analysis of effect of improvements Columbia |

Before intervention, SAP was administered to 71% of women (25% in a timely fashion) in Hospital A and 35% and 50% in Hospital B. Improvement included protocols to administer SAP to all women and increasing availability of antibiotic in the operating room. After intervention, SAP was administered to 95% and 96% in Hospital A and 89% and 96% in Hospital B. SSI rates decreased from 10.5% to 0% in Hospital A and 6.1% to 4.4% in Hospital B. | Simple quality improvements can be used to improve outcomes of care in resource-limited settings. |

| Aiken et al.56 2013 |

Time-series design Quality improvement intervention Kenya |

18 month period of SSI surveillance and introduction of quality improvement intervention. Hospital staff conducted the surveillance daily—diagnosis of SSI within 30 days, antibiotics prescribed. Assessed costs. n = 3343 patients were followed up (Caesarean section, laparotomy, hysterectomy and hernia repair). Before the intervention <2% of patients were prescribed pre-op antibiotics and >99% were prescribed post-op (penicillin, gentamicin and metronidazole IV for 3–5 days followed by oral antibiotics). Locally developed policy: 2 g ampicillin IV + 500 mg metronidazole IV given pre-op; no antibiotics prescribed post-op. Results: at Week 1, 60% and at Week 6, 98% of patients had pre-op prophylaxis and post-op prophylaxis fell to 40% (Week 1) and 10% (Week 6): highly significant changes. Surveillance showed a modest reduction in the risk of superficial SSI (deep SSI results were non-significant). |

There is no evidence to support the use of post-op prophylactic antibiotics. Education was conducted at multidisciplinary seminars to develop an antibiotic prophylaxis policy—seminars were based on review of African and international research papers and national policy documents. Financial and time impacts: cost was reduced by US $2.50 per operation and 450 nurse-hours saved per month. This study emphasizes the importance of local engagement and patient education to facilitate change. |

| Haynes et al.31 2009 |

Prospective pre- and post-intervention study International |

Data were collected before and after the ‘Safe Surgery Saves Lives’ pilot, which was conducted in high-, middle- and low-income settings. Intervention was led by local co-investigator and supported by hospital administration. Local study team introduced the checklist to operating room staff. SAP is included on the 19 item WHO safe-surgery checklist. LMIC sites pre- and post-intervention changes: SAP appropriately given 29.8%–96.2%, 25.4%–50.6%, 42.5%–91.7%, 18.2%–77.6%; SSI rates 20.5%–3.6%; 9.5%–5.8%; 4.1%–2.4%; 6.2%–3.4%. | The introduction of the checklist programme was associated with significant decline in the rate of complications and death from surgery. Implementation was neither costly nor lengthy. |

| Nkurunziza et al.49 2019 |

Prospective Rwanda |

The clinical guideline was based on WHO recommendations from 2015 that pre-op antibiotics be administered 30–60 min before incision and no post-op antibiotics be given. However, 66.7% of women were given 1 g ceftriaxone within 1 h before incision, almost all received post-op antibiotics. SSI was 10.9% at Day 10 and this was attributed to type of skin cleaning. No association was found with either pre- or post-op antibiotics. |

Although the clinical guidelines stated no post-op antibiotics, almost all patients were given post-op antibiotics for 1–3 days or >3 days. The reasons for this are not discussed. |

| Abubakar et al.12 2018 |

Prospective audit Nigeria |

Study objectives were to evaluate compliance with SAP measures (selection of antibiotic, timing and duration) and to determine the DDD of antibiotic per procedure in obs/gyn surgeries. Data were collected from patients’ notes in three hospitals N = 248. Results Antibiotic selection: nitroimidazole (86.2%), β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor (73.4%), third-generation (30.2%) and second-generation (22.6%) cephalosporins were the most frequent antibiotics prescribed for surgical prophylaxis. Timing: pre-op antibiotic was administered within 60 min before incision in 41 (16.5%) procedures (usually at induction of anaesthesia). Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis was inappropriate in >80% of the procedures. Duration: duration of antibiotic prophylaxis was prolonged in all the procedures (range 5–12 days). In ∼99% of cases, antibiotics were prescribed for ≥7 days. The mean duration of antibiotic prophylaxis was 8.7 ± 1.0 days. DDD: SAP was 1675.3 DDD per 100 procedures (16.75 DDD per procedure). |

2/3 hospitals in this study did have infection control teams, but none had a pharmacist to review orders for SAP. The findings of this study highlighted the need for antimicrobial stewardship to reduce the excessive use of antibiotics; inappropriate prescribing of antibiotic prophylaxis may be due to poor knowledge regarding the spectrum of antibiotic activity; non-compliance with timing may be due to lack of a protocol or lack of knowledge regarding optimal timing of antibiotic prophylaxis; extended duration of antibiotic prophylaxis may have occurred as obstetricians and gynaecologists demonstrated lack of belief in single-dose antibiotic prophylaxis, citing poor infection control. There was a misconception that long duration of antibiotic prophylaxis would reduce risk of SSI. |

| Abubakar et al.34 2019 |

Prospective pre- and post-intervention study Nigeria |

Prevalence of SSI in Nigeria 9.1%–30.1%. SSI affects morbidity, mortality and cost. Cost for patients with SSI is double. SAP practice of obstetricians and gynaecologists in Nigeria is not compliant with guidelines. This study evaluated the impact of antibiotic stewardship interventions on prescribing (compliance, choice, timing and duration of antibiotic prophylaxis and antibiotic utilization), clinical (SSI rate) and economic (costs of antibiotic prophylaxis) outcomes. Compliance with timing of antibiotic prophylaxis increased from 14.2% to 43.3%. Compliance with duration increased from 0% to 29.2%. Prescription of third-generation cephalosporin was reduced from 29.2% to 20.6%. Antibiotic utilization significantly decreased and mean cost of SAP was reduced by US $4.20. SSI rates were recorded as 4% pre-intervention and 3.4% post-intervention; however, these measures were limited to period of hospitalization only. |

Antibiotic stewardship interventions in this study included: development and dissemination of a departmental protocol for SAP; educational meeting with the obstetricians and gynaecologists; audit and feedback using baseline data and reminder in the form of wall-mounted posters. In both hospitals, the protocol was developed by a team that comprised four to five consultant obstetricians and gynaecologists and a clinical pharmacist. The protocol presented by the clinical pharmacist recommended: antibiotic prophylaxis administered 60 min before incision and discontinued within 24 h after surgery and type of antibiotic to be used. The educational session focused on the principles of SAP for obs/gyn surgery and the data collected during pre-intervention period highlighting areas where practice did not align with guidelines. |

| Brink et al.50 2017 |

Prospective audit and feedback South Africa |

Study included 34 urban and rural South African hospitals. The aim of the study was to promote multidisciplinary, collaborative action of pharmacist-driven audit and feedback improvement model and to achieve a sustainable reduction in SSI. Started by multidisciplinary team working to achieve consensus on a PAP guideline. Defined four process measure and indicators: antibiotic choice, dose, timing of administration and duration. Workshops to introduce model to surgeons, anaesthetists and nurses. Learning cycles at 8–10 week intervals. 4 week survey of compliance preintervention. Results Pre-intervention: an antimicrobial was administered to 34.7% (95% CI 31.7%–37.7%) of patients within 1 h before incision. Antimicrobial agents consistent with the guideline were administered to 81.2% (95% CI 78.5%–83.8%) of the patients and at the recommended dose in 70.5% (95% CI 67.1%–73.9%). Antimicrobial prophylaxis was limited to one dose or discontinued within 24 h of the end of surgery in 80.8% (95% CI 79.0%–82.5%). The mean SSI rate for the hospital group was 2.46 (95% CI 2.18–2.73). Post-intervention: Timely administration occurred in 56.4% (95% CI 53.1%–59.6%) (P < 0.0001), antibiotic choice consistent with the guideline was administered in 95.9% (95% CI 89.9%–100%) (P = 0.0004), at the recommended dose in 87.0% (95% CI 81.3%–92.8%) (P = 0.0002) and the duration of PAP was appropriate for 93.9% (95% CI 88.1–99.6) (P = 0.0005). SSI rate 1.97 (95% CI 1.79–2.15) (P = 0.0029). |

These authors question the effectiveness of previous interventions aimed at improving adherence to antimicrobial prophylaxis guidelines. Emphasized the need to develop effective teams and coordinate processes to institutionalize new approaches in order to make them sustainable. |

| Allegranzi et al.64 2018 |

Before and after cohort study 5 hospitals in Kenya, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe |

The programme aim was to reduce SSI rates. Intervention was multimodal. Technical work (designed to change procedural aspects of care) was combined with an adaptive approach (which is designed to change attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviours) aimed at facilitating adoption of the measures to reduce SSI including antibiotic use (other measures included pre-op bathing, avoiding hair removal, optimal surgical and skin preparation using locally produced alcohol-based production and improving operating-room discipline). SSI reduced from 8% pre-intervention to 3.8% post-intervention. | SUSP teams were established at each participating study hospital, composed of surgical team leader, nurse and surgeon champions; role was to advocate local implementation of the SUSP to colleagues. Local teams adapted and implemented SUSP interventions. Coordination and technical expertise were provided by WHO staff. Motivation of local staff to improve their practices was key to the success of the intervention. |

| Saied et al.51 2015 |

Before and after study Egypt |

Study included five tertiary acute care surgical hospitals (herniorrhaphy, colectomy, joint replacement, spinal fusion, obs/gyn). 6 month intervention aiming to improve timing of the first dose before surgery (at least one dose administered within 60 min before incision) and the duration (no longer than 24 h) of therapy. Surgeons and anaesthetists were targeted and programme was established within the hospitals’ infection control teams. International guidelines formed basis of education activities. Posters were used to remind prescribers of the optimal timing and duration for antibiotic prophylaxis. Results: post-intervention, 41.6% of patients received optimal antimicrobial prophylaxis and there was a significant reduction in amount of antimicrobials used. |

Few hospitals in Egypt have policies or guidelines on antimicrobial use either in general or specifically for surgical prophylaxis. After the intervention, surgeons were less compliant with duration than timing. Authors attribute this finding to poor awareness of AMR, surgeons’ resistance to changing routine practices and strong belief that hospitals in Egypt are different in terms of increased contamination. Beliefs should be explored and discussed. |

| Saxer et al.54 2009 |

Before and after study Tanzania |

Routine ampicillin (88% post incision + continued for 5 days) pre-intervention (commonly chloramphenicol 60%, aminopenicillins 23% and benzylpenicillins 15%; 118/527 patients received more than one agent). Intervention: 2.2 g amoxicillin/clavulanate given IV 10–30 min before incision (target was 30 min before incision but not always achieved). N = 527 pre-intervention group, n = 114 (21.6%) developed SSI. N = 276 intervention group, n = 11 (4%) developed SSI. Authors concluded timing was less crucial as long as antibiotic was administered before incision. |

Facilities for prevention of HAI were very poor in this hospital (no difference in the pre- and post-intervention phases): ventilation achieved by malfunctioning air conditioner and open windows; household soap for scrubbing (technique did not meet investigators’ requirements); and inconsistent sterilization due to unstable power supply. |

| Ntumba et al.62 2015 |

Poster presentation Before and after study Kenya |

This presentation presents the results of the SUSP project from AIC Kijabe hospital in rural Kenya at 18 months. SSI rate significantly decreased from 9.3% to 5% post-intervention. Patients receiving post-op antibiotics decreased from 50% to 26%. | Important to note that six SSI prevention methods were introduced in this project. Appropriate use of antibiotic prophylaxis was only one of them. |

| Elbur et al.53 2013 |

Prospective cross-sectional study Sudan |

Patients in obs/gyn SSI detected by surveillance during admission and by structured telephone call post-discharge until Day 28. SAP given to 98.8% of patients in the operating room. Time of first dose was proper (30–60 min before incision) in 11.6%, late (1–29 min before incision) in 58.8% and too late (after incision) in 24.4%. All patients had post-op prophylaxis prescribed (average 8 days). SSI rate was 7.8% overall. |

There was a lack of consistency in prescribing in this study. Extended duration of post-op prophylaxis was attributed to lack of awareness of evidence-based guideline among healthcare providers and fear of negative consequences of infections. Authors recommend intervention is required to improve SSI rate. |

| Billoro et al.41 2019 |

Prospective cohort study Ethiopia |

n = 42/255 (16.5%) of patients receiving various types of surgery developed SSI. Patients who received SAP >1 h before surgery were more likely to develop SSI than those who were given SAP ≤1 h (20% versus 11.4%). | Surveillance on rate of SSI and associated factors should be conducted and feedback given to surgeons and hospital authorities. |

| De Nardo et al.47 2016 |

Prospective observational study Tanzania |

n = 664 patients who had Caesarean section. N = 10 (2.1%) given pre-incision SAP. Most patients received 3 days IV ceftriaxone + metronidazole then 5 days oral ampicillin/cloxacillin + metronidazole commenced >60 min after procedure. SSI occurred in 48.2%. | No protocol for the administration of SAP currently exists; the type, dose and timing depend on individual clinician’s preference. Need to review national guidelines. |

| Eriksen et al.42 2003 |

Prospective observational survey Tanzania |

n = 77/396 (19.4%) of patients developed SSI after surgery (e.g. laparotomy, appendectomy, hernia repair, colonic surgery, thyroidectomy). n = 300/396 were given SAP median 5 days (range 1–14 days). n = 6/300 patients received SAP before the operation (time not specified). | SAP was not optimal and should be re-evaluated. Better use of SAP may reduce incidence of SSI and be more cost-effective. Post- discharge SSI surveillance is important to achieve accurate SSI rates. |

| Halawi et al.48 2018 |

Prospective observational study Ethiopia |

n = 27/131 (20.6%) of patients developed SSI following surgery. 68.7% of patients had SAP administered pre-op (37.8% within 1 h of incisions). n = 80 (88.9%) received SAP for >24 h after surgery. | No local guideline and type of antibiotic used not consistent with international guidelines. |

| Fehr et al.43 2006 |

Prospective cohort study Tanzania |

n = 114/613 (21.6%) of patients developed SSI following surgery (Caesarean sections, gynaecological surgery). n = 524/527 received SAP. 88% SAP administered after incision, 5% within 60 min before surgery; >90% received SAP for 5 days. | Inappropriate SAP may have contributed significantly to rate of SSI. Important to establish surveillance programmes. |

| Mwita et al.44 2018 |

Prospective study Botswana |

Aim was to describe current SSI burden and antibiotic surgical patterns. Emergency and elective surgery included (laparotomy, appendectomy, excisions and mastectomy). 73.3% of patients prescribed antibiotics: 15% pre-op (majority continued these post-op), 58.3% post-op and 26.8% no antibiotics. Post-op antibiotics were started for suspected infections in patients with peritonitis (n = 8), abscesses (n = 4) and appendicitis (n = 50). Mean duration of post-op antibiotics was 5 ± 2 days. Drugs used: cefotaxime (80.7%), metronidazole (63.5%), cefradine (13.6%) and amoxicillin/clavulanate (11.6%). Co-administration of cefotaxime and metronidazole was found in 134 (48.6%) patients post-op. Oral antibiotics cloxacillin, amoxicillin, doxycycline and metronidazole were also prescribed. SSI rate = 8.5% in emergency and 9.9% in elective. 88.2% of patient with culture-positive SSI had not received pre-op antibiotics. |

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not consistent with international or national guidelines in terms of timing, choice of antibiotics and duration of prophylaxis. Low compliance with Botswanan guideline increases hospital costs and poses an increased risk of resistance. |

| Laloto et al.32 2017 |

Prospective study Ethiopia |

Aim was to show incidence and predictors of SSI. 20/105 (19.1%) developed SSI following head and neck, gastrointestinal, urologic, breast or hernia surgery. Administration of the first dose of SAP >1 h of incision was an independent predictor of SSI. | Administration of SAP for >24 h was not protective and may increase AMR, therefore should be avoided. Surveillance on incidence and predictors of SSI could reduce rate of SSI. |

| Muchuweti et al.33 2015 |

Prospective study Zimbabwe |

Aim was to determine frequency and risk factors for abdominal SSI. n = 74/285 (26%) of patients developed SSI. 82% of patients had SAP: infection rate was lower in patients who had SAP administered pre- or intra-op compared with post-op. | Delayed used of SAP is a risk factor for the development of SSI. |

| Ameh et al.35 2009 |

Prospective study Sub-Saharan Africa |

Aim was to determine the burden and risk factors for SSI in children. n = 76/322 (23.6%) developed SSI. SAP was administered before incision (timing not reported) but not repeated during operation. SAP was continued for 5 days in patients with contaminated or dirty incisions. No SAP given for clean surgery. | Long duration of surgery was a major problem in this setting. No antibiotic or infection control guidelines. |

| Brisibe et al.40 2014 |

Cross-sectional comparative study Nigeria |

Aim of the study was to compare adherence to WHO guidelines in two hospitals. Hospital A followed government directive to follow WHO guidelines and had a multidisciplinary responsibility for education and adherence to the policy. Hospital B did not have an infection control committee or a policy. Data were collected from staff caring for women having Caesarean section using a semi-structured questionnaire and observations. The appropriate timing of the administration of prophylactic antibiotics (intra-op administration) was observed by 57.58% of the respondents in A, compared with 22.86% in B (P = 0.00). |

Emphasize the importance of a committee responsible for surveillance and education as well as regular supply of necessary antiseptics and consumables. Also need for a dedicated infection control team. Clinicians in Hospital A attributed their non-compliance to poor supervision by the infection control team and lack of training. Hospital B: lack of training and absence of a hospital policy on infection control. |

| Habte-Gabr et al.39 1988 |

Observational study Ethiopia |

n = 165/1006 (16.4%) of patients admitted to surgical unit developed nosocomial infection. SSI infections were most common (59% of all infections). 72% of patients were given SAP started days before or on the day of operations for a week or longer. | HAIs are costly and effective control methods are needed to reduce incidence. |

| Sway et al.55 2020 |

Observational study Kenya |

Primary focus was timing of PAP. Outcome measure was SSI. Compared rates of SSI in two hospitals in Nairobi. Hospital A provided antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to incision for all patients and Hospital B provided only post-op prophylaxis to all patients. Results: the SSI rate was 4.0% (12/299; 11 superficial SSI, 1 deep SSI) at Hospital A and 9.3% (28/301; 18 superficial SSI, 7 deep SSI, 3 organ/space SSI) at Hospital B. |

Correctly timed SAP reduced rate of SSI and should be promoted. |

| Bhangu et al.36 2018 |

Multicentre prospective cohort study International |

Primary outcome measure was the 30 day SSI incidence comparing high-, middle- and low-HDI countries. Data were collected on the incidence and length of antimicrobial treatment surgery. Results: the unadjusted SSI incidence high HDI (n = 691/7339 [9.4%] patients), middle HDI (n = 549/3918 [14.0%] patients) and low HDI (n = 298/1282 [23.2%] patients). Administration of pre-op or prophylactic antibiotics, or both, was higher in groups with low HDI (n = 1224/1282 [95.5%]) than in countries with middle HDI (n = 3392/3918 [86.6%] patients) and high HDI (n=6446/7339 [87.8%] patients). Patients in LMICs were more likely to receive post-op antibiotics than those in high-HDI countries (3376/7339 [46.0%] patients in high-HDI countries versus 3135/3918 [80.0%] patients in middle-HDI countries versus 1098/1282 [85.6%] patients in low-HDI countries; P<0.001). Courses of post-op antibiotics were longer in patients in LMICs than in high-income countries, with the number of patients receiving antibiotics for 5 days or more increasing from countries with high HDI to low HDI [1830/7339 (24.9%) patients in high-HDI countries versus 1837/3918 (46.9%) patients in middle-HDI countries versus 650/1282 (50.7%) patients in low-HDI countries; P<0.001]. |

This study included 12 539 participants from 343 hospitals in 66 countries (15 countries in Africa). |

| Shankar63 2018 |

Intervention India |

The main aim of this study was to introduce use of WHO surgical safety checklist. Checking administration of pre-op antibiotic prophylaxis is part of the checklist. The author stated that although 100% of patients were given pre-op antibiotics these were administered to all patients in the morning regardless of timing of operation, thus some patients received them too early. Correct practice was introduced with the checklist. 27 patients were identified as not having had SAP and this was corrected. Infection rate was 2%. No pre-intervention data given. | Initially surgeons were resistant to change, indicating it was not needed; however, following presentations about WHO guidelines and research supporting efficacy, all staff participated. |

| Anand Paramadhas et al.9 2019 |

Point prevalence survey Botswana |

Across the four hospitals studied, duration of surgical prophylaxis of >1 day occurred in 66.7% specialist hospitals, 100% tertiary, 90.32% district and 100% primary. | This finding of extended prophylaxis was consistent with other studies. |

| Momanyi et al.10 2019 |

Point prevalence survey Kenya |

76.9% of patients on multiple-dose prophylaxis, 9.6% on single-dose. Ceftriaxone was the most prescribed agent for single-dose surgical prophylaxis. | Concern regarding prolonged use for surgical prophylaxis and well as use of ceftriaxone. |

| Ahoyo et al.8 2014 |

Point prevalence survey Benin |

39/45 hospitals participated: n = 3130 patients. SSI prevalence was 24.7%. 64.6% of patients surveyed were treated with antibiotics: 30% were non-infected. 40.8% self-medications. |

High levels of resistance. Authors cited ease of accessibility of antibiotics and indiscriminate use in non-infected patients as cause of resistance and called for standardized approach to HAI surveillance in Africa. |

| Bediako-Bowan et al.11 2019 |

Point prevalence survey Ghana |

88.4% of patients given SAP were treated for >1 day; 1.6% as single dose. | Guidelines need to be re-emphasized and tailored stewardship programmes are recommended. |

| van der Sandt et al.45 2019 |

Retrospective chart review South Africa |

Chart review in a teaching hospital n = 112 and a private hospital n = 112. Prescription of antimicrobials compared with current SAP guidelines. Criteria: appropriate antimicrobial selection, dosing, timing of administration, re-dosing and duration of treatment. Teaching hospital: 77.3% received SAP when indicated, 21.1% when not indicated. Met 3/5 criteria on 58.8% of situations. Private: 100% received SAP when indicated, 45.9% when not indicated. |

Recommend local evidence-based SAP guidelines to improve care. Non-compliance with guidelines attributed to inappropriate selection and dosing. |

| King52 1989 |

Retrospective chart review Zimbabwe |

Reported SSI rates following Caesarean section when different antibiotic regimes were used. Limited details about timing of SAP. SSI rate was 26%. | Recommend that SAP should be administered peri-operatively: this is not in line with current recommendations. |

| Aulakh et al.57 2018 |

Retrospective case series Gambia |

Records of n = 682/777 cases of Caesarean section. 7.4% received SAP, all received multiple-dose post-op antibiotics: IV for 2/3 days followed by 5–7 days oral. SSI rate was 13.2%. | Compliance with guidelines would reduce staff workload, conserve antibiotic resources and reduce costs. |

| Argaw et al.46 2017 |

Retrospective cross-sectional study Addis Ababa |

Assessment of the practice of SAP and development of SSI in orthopaedic and trauma unit. N = 200 patients. 80% had pre-op prophylaxis—n = 153/160 (96%) also received post-op prophylaxis. Timing of SAP not recorded in 54% of patients’ charts, 23% received SAP >2 h before incision, 21% during induction. Duration of post-op was 61% for >72 h, 23% 48–72 h and 4% <24 h. 16% SSI within 1 year after surgery. | No local guideline for administration of SAP. When compared with international guidelines, timing and duration of antibiotics was inappropriate. Lack of documentation was a major issue. Recommend development of local evidence-based guidelines. |

| Gutema et al.37 2018 |

Retrospective study Ethiopia |

Aim was to assess prevalence of antibiotic use and identify indications for use. n = 2231 patients reviewed. 63.6% and 41.3% of obs/gyn and surgery patients given prophylactic antibiotics (timing not reported) and 44.1% and 65.3% developed an infection. High antibiotic consumption in this hospital. | Need to implement ASPs that focus on rational prescribing and better procedures to prevent HAI. |

| Gyedu et al.59 2019 |

Survey Ghana |

Survey to assess the perceptions and practices of surgeons in Ghana regarding the use of antibiotics for groin hernia repair in relation to evidence-based guidelines. Structured questionnaire: 117/146 (80%) response rate. 62% no antibiotics, 10% pre-op, 15% pre- and post-op antibiotics when no mesh used. 53% pre- and post-op antibiotics when mesh was used. |

Previous published rates of SSI for groin hernia surgery in Ghana 1%–3% thus low risk—recommendations state no need for antibiotic prophylaxis. 25% practice inconsistent with evidence-based guidelines—55% in mesh repairs. Most common reason was concern for SSI. Authors advise other measures of infection control such as bathing and strict aseptic technique. |

| Clack et al.71 2019 |

Qualitative study Sub-Saharan Africa (Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe) |

Qualitative study investigating the impact of SUSP. Study was guided by two primary study questions: What are the facilitators and barriers to implementation of a comprehensive unit-based safety programme to reduce SSI in these five African hospitals? What influence, if any, did SUSP have on the safety culture in participating hospitals? |

A central facilitator to implementation was the establishment of local multidisciplinary teams: they actively included other stakeholders to promote wider ownership of change and became a driving force and helped overcome barriers. Results related to optimization of antibiotic prophylaxis: regular feedback of data on SSI surveillance and compliance with SSI preventative measures was important to create a tension for change and to sustain engagement with the project: it was important to show staff that SSI rate was reducing at the same time as the number of patients receiving post-op antibiotics was reducing. |

HDI, human development index; IM, intramuscular; intra-op, intra-operative; obs/gyn, obstetrics/gynaecology; PAP, perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis; post-op, post-operative; pre-op, pre-operative; RR, risk ratio; SUSP, Surgical Unit-based Safety Programme.

Methodological quality

Ten studies were critically appraised prior to inclusion in the meta-analysis. Five studies20–24 compared pre- and post-operative SAP. Five studies25–29 compared short- and long-term SAP. Overall quality scores ranged from 8 to 12 out of 13; the risk of selection bias was deemed high in 4 studies21,24–26 and the risk of detection bias was deemed high in 5 studies.23–26,28 The results of the critical appraisal process are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Critical appraisal scores of selected studies

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dlamini et al.20 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 12 |

| Mugisa et al.22 2018 | Y | Y | Y | UC | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| Kayihura et al.21 2003 | Y | UC | Y | UC | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Osman et al.23 2013 | Y | Y | Y | UC | N | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Reggiori et al.24 1996 | Y | UC | UC | UC | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Nitrushwa et al.28 2019 | Y | Y | Y | UC | N | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Ahmed et al.25 2004 | UC | UC | Y | UC | N | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Lyimo et al.27 2013 | Y | Y | Y | UC | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

| Ijarotimi et al.26 2013 | Y | UC | Y | UC | N | UC | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10 |

| Westen et al.29 2015 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 11 |

Publications were assessed using the JBI Meta-analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument.

Y, yes; N, no; UC, unclear.

Incidence of SSI

Several studies in this review, including a recent international cohort study, confirmed that the incidence of SSI is significantly higher in LMICs than in higher-income countries.30–37 SSIs have been reported as the leading hospital-acquired infection (HAI) in LMICs,38,39 with highly variable reported rates, e.g. 8.5%–23.2% following gastrointestinal surgery and one study reported an incidence of 85.1% for SSI following Caesarean section.20 However, surveillance data regarding HAI are generally poorly recorded across LMICs.32,38,40–43

Compliance with SAP guidelines

Patients in LMICs are more likely to receive post-operative antibiotics with treatment lasting for more than 5 days than patients in high-income countries.21,22 The WHO guidelines on SAP are not always adhered to and local guidelines are not always available or followed.34,35,40,44–52 Studies reported low compliance with recommended timing of SAP and patients being given antibiotics for long periods post-operatively or when they were not indicated.12,32,42–44,46,48,51,53–55 Despite a lack of evidence to support the use of post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis, many surgeons in developing countries continue to use post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis.12,30,32,51,53,56,57Non-compliance with WHO guidelines may be due to poor knowledge of spectrum of antibiotic activity and of optimal timing of antibiotic prophylaxis.12,45 Clinicians cite lack of an infection control committee and lack of policy and education40,58 as well as concerns about SSI59,60 as factors in non-compliance.

Interventions to increase adherence to SAP guidelines

A recent systematic review advocated the use of multifaceted strategies including staff engagement and education, as well as evaluation of the success of interventions in reducing SSI.61 Several individual projects in LMICs that aim to reduce the incidence of SSI have included compliance with WHO guidelines on SAP as part of a wider programme, e.g. WHO surgical safety checklist, pre-operative bathing, avoiding hair removal, optimal surgical hand and skin preparation using locally produced alcohol-based products and improving operating room discipline.31,62–64 Most of the individual projects demonstrated success in reducing the incidence of SSI, with the longest follow-up being 18 months.64 Interventions to promote the correct use of SAP have been shown to be successful in reducing incidence of SSI, even in low-resource settings.30,31,50,65

Several clinical trials assessed different SAP regimens; however, even in recent studies not all of the treatment arms complied with WHO guidelines regarding single dose and timing of administration. Details for individual studies are reported in Table 1. The majority of RCTs were conducted in women having elective and/or emergency Caesarean section;20–29 other studies investigated SAP in patients having surgical treatment for hernias,24,66 transrectal prostate biopsy67 and clean day-case surgery for children.68 Five studies investigated the efficacy of single-dose pre-incision SAP versus single-dose or prolonged post-incision treatment in patients undergoing emergency or elective Caesarean section20–24 and were included in a meta-analysis. Six studies compared a short duration of SAP to a long duration of SAP with patients in both groups receiving a first dose pre-incision and five were conducted in patients undergoing emergency or elective Caesarean section25–29 and were included in a meta-analysis. One study that assessed SAP in patients undergoing transrectal biopsy was not included in the meta-analysis due to heterogeneity of the study population.67 Other studies compared different types of antibiotics69 and single-dose SAP with placebo.66,68,70 Studies consistently reported either a reduction or no change in the incidence of SSI between groups, thereby supporting the use of single-dose pre-incision or short-duration SAP in LMICs.

Meta-analyses of primary outcome—SSI incidence

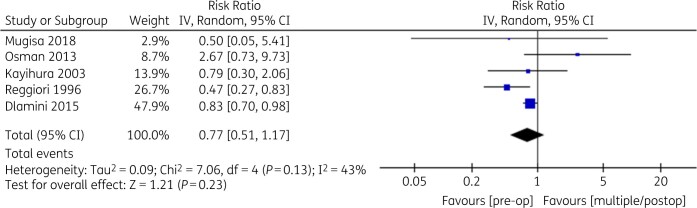

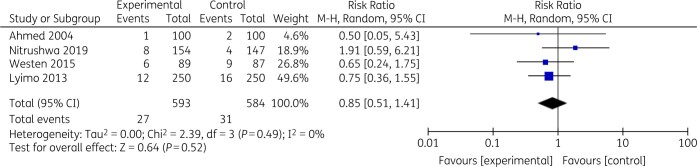

The random-effects pooled results across five studies (n = 1268 participants) showed the risk ratio for the development of SSI was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.51–1.17) (P = 0.23) for the single-dose pre-incision group versus the single- or multiple-dose post-incision group (Figure 2). Heterogeneity was moderate (Tau2 = 0.09, I2 = 43%). The random-effects pooled results across five studies (n = 1377 participants) showed the risk ratio for the development of SSI was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.55–1.14) (P = 0.63) for the short-duration group versus the long-duration group (Figure 3). Heterogeneity was low (Tau2 = 0.00, I2 = 0%).

Figure 2.

Single-dose pre-incision versus single/multiple post-incision SAP.

Figure 3.

Short-duration versus long-duration SAP.

Cost savings of compliance with SAP guidelines

Several studies reported on the difference in the cost between SAP regimens, with mixed findings depending on type of antibiotic given. Single-dose pre-operative prophylaxis was shown to cost a tenth of post-operative prophylaxis,21 reducing costs by US $2.5056 or $4.20 per procedure.34 There was overall agreement that correct use of SAP would reduce the costs for patients or institutions.26,27,29,30,57,70 Studies also mentioned greater compliance with regimen and nurse-time saving as a result of a reduced need to administer IV antibiotics for lengthy post-operative periods.25,26 It was proposed that emphasizing the potential cost savings would promote the engagement of hospital managers who have the power to drive changes such as production of local evidence-based guidelines and interventions to reduce SSI.56

Resistance to change

Studies reported that non-compliance with guidelines occurred for a variety of reasons. Several studies found that clinicians believed that extended duration of post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis is needed due to poor hygiene, poor infection control and overcrowding in hospitals.12,30,51 There was also widespread belief that a long duration of antibiotic prophylaxis would reduce the risk of SSI and lack of belief in the efficacy of single-dose prophylaxis.12 Patient expectation of longer duration of SAP may also be an important factor.56 A qualitative study showed that at the same time as the number of patients on post-operative antibiotics was reducing, the SSI rate was also reducing, which provided proof of impact and encouraged compliance with new approaches.71

Education interventions

In order to be successful, education interventions must be relevant to local circumstances and promote the development of effective local teams.31,34,50 The process should encourage clinicians to discuss their beliefs, emphasize the importance of surveillance and involve them in the development of local guidelines that are consistent with evidence and WHO guidelines.56 Education of patients may also reduce their expectation of extended use of SAP.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to consider the effectiveness of SAP in the prevention of SSI in LMICs to support an education intervention in Ghana specifically but acknowledge there would be implications for practice in other LMICs. Clinicians in LMICs undoubtedly face environmental challenges that are exacerbated by scarce resources; however, studies in this review have demonstrated that improvements in practice can be successful in low-resource environments. Even though the sizes of absolute effect were small (risk ratio of 0.77 and 0.89) and not statistically significant, single-dose and short-duration SAP in Caesarean section was associated with lower risk of SSI. Although this cannot be directly extrapolated to other procedures it provides support for adherence to local, national and international guidelines on SAP, including single-dose and short-duration SAP. This can contribute significantly to reduction of SSI and control of AMR, as well as conserving resources and potentially reducing duration of hospitalization. Conversely, inappropriate post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to increase costs and promote AMR. Additionally, this review supports the need for improvement in LMICs across all core components of infection control identified by the WHO. Staff education was highlighted in several studies as a key element to build infection surveillance and control skills in LMICs. An audit of SAP in Nigeria suggested that poor knowledge regarding the spectrum of antibiotic activity may lead to inappropriate prescribing12 and an implementation study in Kenya found limited awareness of national policy documents, poor access to appropriate medicines and lack of awareness of the potential for cost savings.56 Successful programmes to improve antimicrobial stewardship have identified the establishment of local multidisciplinary and cross-departmental teams to promote ownership of change. All ASPs require high-level support including resources, which can be a concern in LMICs.72 Consequently, hospital managers must be made aware of the potential for cost and time saving with appropriate SAP as well as a potential reduction in AMR and its future consequences on costs as well as on morbidity and mortality.73,74 Other essential factors include the development of a local SAP policy informed by review of research and guidelines, as local cultural and contextual issues are important for successful programmes to improve future antibiotic use,18 and the establishment of a robust method of collection of process and outcome measurement data such as SSI surveillance and monitoring of compliance with local policy. Regularly sharing local data with clinical teams is essential to engage the workforce as well as identifying local champions to become the driving force to overcome barriers to change and sustain new ways of working.

In order to address the common misconceptions, education programmes should include interactive workshops to explore clinicians’ beliefs and perceptions of factors that contribute to increased risk of SSI. Education sessions should also be used to raise awareness of national policy guidelines and relevant international research findings. Education of patients in terms of their expectations regarding SAP is also important. Patients in LMICs may believe that receiving more medicines is better for outcomes or for achieving value from national insurance schemes. Studies indicated that posters were a useful resource for the education of both clinicians and patients, and also served to reinforce key messages.56

Conclusions and further work

This literature review provided useful evidence to support compliance with WHO recommendations around using a single dose of surgical prophylaxis to prevent SSI in LMICs. We have utilized the findings to develop and deliver multi-professional interactive learning sessions in two hospitals in Ghana to share the evidence and promote compliance with WHO and national guidelines. Both hospitals, with the help of their AMS teams, are developing evidence-based local SAP policies for different surgical subspecialties and this review will help to guide this work. Local policies are being promoted to clinical staff through posters in wards and theatres as well as being included in ongoing training as part of their ASPs. We hope this work will be of interest as other countries seek to improve their use of antimicrobials to reduce high AMR rates and implement ASPs to optimize SAP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Healthcare Improvement Scotland and Ghana Hospitals partnership for engaging with the results of this review to inform training and support improvements in SAP.

Funding

This research/project was part of the Commonwealth Partnerships on Antimicrobial Stewardship (CwPAMS) (grant number A11) supported by Tropical Health and Education Trust (THET) and Commonwealth Pharmacists Association (CPA) using Official Development Assistance (ODA) funding, through the Department of Health and Social Care’s Fleming Fund. UK partners involved were volunteers supported by their NHS host organizations.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the Fleming Fund, the Department of Health and Social Care, THET or CPA.

Supplementary data

Appendix S1 is available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online.

References

- 1. Donà D, Luise D, La Pergola E et al. Effects of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis in pediatrics. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019; 8: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vicentini C, Politano G, Corcione S et al. Surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis prescribing practices and impact on infection risk: results from a multicenter surveillance study in Italy (2012-2017). Am J Infect Control 2019; 47: 1426–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. Global Guidelines on the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. 2018. https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/publications/ssi-guidelines/en/.

- 4. PHE. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Start Smart—Then Focus. 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/antimicrobial-stewardship-start-smart-then-focus.

- 5. Scottish Antimicrobial Prescribing Group. Surgical Prophylaxis. https://www.sapg.scot/quality-improvement/hospital-prescribing/surgical-prophylaxis/.

- 6. Malcolm W, Nathwani D, Davey P et al. From intermittent antibiotic point prevalence surveys to quality improvement: experience in Scottish hospitals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2013; 2: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Versporten A, Zarb P, Caniaux I et al. Antimicrobial consumption and resistance in adult hospital inpatients in 53 countries: results of an internet-based global point prevalence survey. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6: e619–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahoyo TA, Bankolé AS, Adéoti FM et al. Prevalence of nosocomial infections and anti-infective therapy in Benin: results of the first nationwide survey in 2012. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2014; 3: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anand Paramadhas BD, Tiroyakgosi C, Mpinda-Joseph P et al. Point prevalence study of antimicrobial use among hospitals across Botswana; findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2019; 17: 535–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Momanyi L, Opanga S, Nyamu D et al. Antibiotic prescribing patterns at a leading referral hospital in Kenya: a point prevalence survey. J Res Pharm Pract 20198: 149–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bediako-Bowan AAA, Owusu E, Appiah-Korang L et al. Antibiotic use in surgical units of selected hospitals in Ghana: a multi-centre point prevalence survey. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abubakar U, Syed Sulaiman SA, Adesiyun AG. Utilization of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for obstetrics and gynaecology surgeries in Northern Nigeria. Int J Clin Pharm 2018; 40: 1037–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karaali C, Emiroglu M, Atalay S et al. A new antibiotic stewardship program approach is effective on inappropriate surgical prophylaxis and discharge prescription. J Infect Dev Ctries 2019; 13: 961–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Al Matar M, Enani M, Binsaleh G et al. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in 26 Saudi hospitals in 2016. J Infect Public Health 2019; 12: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saleem Z, Hassali MA, Versporten A et al. A multicenter point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in Punjab, Pakistan: findings and implications. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2019; 17: 285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Singh SK, Sengupta S, Antony R et al. Variations in antibiotic use across India: multi-centre study through Global Point Prevalence survey. J Hosp Infect 2019; 103: 280–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Afriyie DK, Sefah IA, Sneddon J et al. Antimicrobial point prevalence surveys in two Ghanaian hospitals: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2020; 2: dlaa001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Charani E, Smith I, Skodvin B et al. Investigating the cultural and contextual determinants of antimicrobial stewardship programmes across low-, middle- and high-income countries—a qualitative study. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0209847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aromataris E, Munn Z. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dlamini LD, Sekikubo M, Tumukunde J et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section at a Ugandan hospital: a randomised clinical trial evaluating the effect of administration time on the incidence of postoperative infections. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015; 15: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kayihura V, Osman NB, Bugalho A et al. Choice of antibiotics for infection prophylaxis in emergency cesarean sections in low-income countries: a cost-benefit study in Mozambique. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003; 82: 636–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mugisa G, Kiondo P, Namagembe I. Single dose ceftriaxone and metronidazole versus multiple doses for antibiotic prophylaxis at elective caesarean section in Mulago hospital: a randomized clinical trial [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. AAS Open Res 2018; 1: 11. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Osman B, Abbas A, Ahmed MA et al. Prophylactic ceftizoxime for elective cesarean delivery at Soba Hospital, Sudan. BMC Res Notes 2013; 6: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reggiori A, Ravera M, Cocozza E et al. Randomized study of antibiotic prophylaxis for general and gynaecological surgery from a single centre in rural Africa. Br J Surg 1996; 83: 356–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahmed ET, Mirghani AO, Gerais AS et al. Ceftriaxone versus ampicillin/cloxacillin as antibiotic prophylaxis in elective caesarean section. East Mediterr Health J 2004; 10: 277–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ijarotimi AO, Badejoko OO, Ijarotimi O et al. Comparison of short versus long term antibiotic prophylaxis in elective caesarean section at the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 2013; 20: 325–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lyimo FM, Massinde AN, Kidenya BR et al. Single dose of gentamicin in combination with metronidazole versus multiple doses for prevention of post-caesarean infection at Bugando Medical Centre in Mwanza, Tanzania: a randomized, equivalence, controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013; 13: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nitrushwa D, Ghebre R, Unyuzimana MA et al. Single vs. extended antibiotics for prevention of surgical infection in emergent cesarean delivery in Rwanda. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 220: S414–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Westen EHMN, Kolk PR, Van Velzen CL et al. Single-dose compared with multiple day antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean section in low-resource settings, a randomized controlled, noninferiority trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2015; 94: 43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aiken AM, Karuri DM, Wanyoro AK et al. Interventional studies for preventing surgical site infections in sub-Saharan Africa–a systematic review. Int J Surg 2012; 10: 242–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haynes A, Weiser TG, Berry WR et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Laloto TL, Gemeda GH, Abdella SH. Incidence and predictors of surgical site infection in Ethiopia: prospective cohort. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17: 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muchuweti D, Jonsson KUG. Abdominal surgical site infections: a prospective study of determinant factors in Harare, Zimbabwe. Int Wound J 2015; 12: 517–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abubakar U, Sulaiman SAS, Adesiyun AJ. Impact of pharmacist-led antibiotic stewardship interventions on compliance with surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in obstetric and gynecologic surgeries in Nigeria. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0213395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ameh EA, Mshelbwala PM, Nasir AA et al. Surgical site infection in children: prospective analysis of the burden and risk factors in a sub-Saharan African setting. Surg Infect 2009; 10: 105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bhangu A, Ademuyiwa AO, Aguilera ML et al. Surgical site infection after gastrointestinal surgery in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: a prospective, international, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 516–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gutema G, Håkonsen H, Engidawork E et al. Multiple challenges of antibiotic use in a large hospital in Ethiopia—a ward-specific study showing high rates of hospital-acquired infections and ineffective prophylaxis. BMC Health Serv Res 2018; 18: 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011; 377: 228–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Habte-Gabr E, Gedebou M, Kronvall G. Hospital-acquired infections among surgical patients in Tikur Anbessa Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Am J Infect Control 1988; 16: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brisibe SB, Ordinioha B, Gbeneolol PK. Knowledge, attitude, and infection control practices of two tertiary hospitals in Port-Harcourt, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2014; 17: 691–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Billoro BB, Nunemo MH, Gelan SE. Evaluation of antimicrobial prophylaxis use and rate of surgical site infection in surgical ward of Wachemo University Nigist Eleni Mohammed Memorial Hospital, Southern Ethiopia: prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19: 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eriksen HM, Chugulu S, Kondo S et al. Surgical-site infections at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center. J Hosp Infect 2003; 55: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fehr J, Hatz C, Soka I et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis to prevent surgical site infections in a rural sub-Saharan hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006; 12: 1224–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mwita JC, Souda S, Magafu MGMD et al. Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent surgical site infections in Botswana: findings and implications. Hosp Pract (1995) 2018; 46: 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van der Sandt N, Schellack N, Mabope L et al. Surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis among pediatric patients in South Africa comparing two healthcare settings. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019; 38: 122–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Argaw NA, Shumbash KZ, Asfaw AA et al. Assessment of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis in Orthopaedics and Traumatology Surgical Unit of a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Addis Ababa. BMC Res Notes 2017; 10: 160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. De Nardo P, Gentilotti E, Nguhuni B et al. Post-caesarean section surgical site infections at a Tanzanian tertiary hospital: a prospective observational study. J Hosp Infect 2016; 93: 355–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Halawi E, Assefa T, Hussen S. Pattern of antibiotics use, incidence and predictors of surgical site infections in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. BMC Res Notes 2018; 11: 538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nkurunziza T, Kateera F, Riviello R et al. Prevalence and predictors of surgical-site infection after caesarean section at a rural district hospital in Rwanda. Br J Surg 2019; 106: e121–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Brink AJ, Messina AP, Feldman C et al. From guidelines to practice: a pharmacist-driven prospective audit and feedback improvement model for peri-operative antibiotic prophylaxis in 34 South African hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72: 1227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Saied T, Hafez SF, Kandeel A et al. Antimicrobial stewardship to optimize the use of antimicrobials for surgical prophylaxis in Egypt: a multicenter pilot intervention study. Am J Infect Control 2015; 43: e67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. King C. Infection following caesarean section: a study of the literature and cases with emphasis on prevention. Cent Afr J Med 1989; 35: 556–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Elbur AI, Yousif MAER, Elsayed ASA et al. An audit of prophylactic surgical antibiotic use in a Sudanese Teaching Hospital. Int J Clin Pharm 2013; 35: 149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Saxer F, Widmer A, Fehr J et al. Benefit of a single preoperative dose of antibiotics in a sub-Saharan district hospital: minimal input, massive impact. Ann Surg 2009; 249: 322–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sway A, Wanyoro A, Nthumba P et al. Prospective cohort study on timing of antimicrobial prophylaxis for post-cesarean surgical site infections. Surg Infect 2020; 21: 552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Aiken AM, Mwangi J, Juma F et al. Changing use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in Thika Hospital, Kenya: a quality improvement intervention with an interrupted time series design. PLoS One 2013; 8: e78942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Aulakh A, Idoko P, Anderson ST et al. Caesarean section wound infections and antibiotic use: a retrospective case-series in a tertiary referral hospital in The Gambia. Trop Doct 2018; 48: 192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Branch-Elliman W, Pizer SD, Dasinger EA et al. Facility type and surgical specialty are associated with suboptimal surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis practice patterns: a multi-center, retrospective cohort study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2019; 8: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gyedu A, Katz M, Agbedinu K et al. Antibiotics for groin hernia repair according to evidence-based guidelines: time for action in Ghana. J Surg Res 2019; 238: 90–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Butt SZ, Ahmad M, Saeed H et al. Post-surgical antibiotic prophylaxis: impact of pharmacist’s educational intervention on appropriate use of antibiotics. J Infect Public Health 2019; 12: 854–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ariyo P, Zayed B, Riese V et al. Implementation strategies to reduce surgical site infections: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2019; 40: 287–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ntumba P, Mwangi C, Barasa J. Multimodal approach for surgical site infection prevention – results from a pilot site in Kenya. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2015; 4 Suppl 1: P87. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shankar R. Implementation of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist at a teaching hospital in India and evaluation of the effects on perioperative complications. Int J Health Plann Manage 2018; 33: 836–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Allegranzi B, Aitken AM, Kubilay NZ et al. A multimodal infection control and patient safety intervention to reduce surgical site infections in Africa: a multicentre, before-after, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weinberg M, Fuentes JM, Ruiz AI et al. Reducing infections among women undergoing cesarean section in Colombia by means of continuous quality improvement methods. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 2357–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Usang UE, Sowande OA, Adejuyigbe O et al. The role of preoperative antibiotics in the prevention of wound infection after day case surgery for inguinal hernia in children in Ile Ife, Nigeria. Pediatr Surg Int 2008; 24: 1181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Agbugui JO, Obarisiagbon EO, Osaigbovo EO et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for transrectal prostate biopsy: a comparison of one-day and five-day regimen. Niger Postgrad Med J 2014; 21: 213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]