Cholesterol management is the cornerstone for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) prevention. The 2018 American Multi-society Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol outlines a widely applicable framework for ASCVD risk reduction through lipid management.1 There are important racial/ethnic differences and disparities in cholesterol management. Despite elevated ASCVD risk, Black patients have lower prevalence of dyslipidemia compared with non-Hispanic White (NHW) patients, whereas Hispanic and South Asian patients have higher triglyceride levels.2 Asian patients may experience increased statin sensitivity.1 Diverse racial/ethnic participation in trials upon which guidelines are based is paramount for the generalizability of trial results and guidelines and for strategies to address pervasive ASCVD disparities.

We evaluated the reporting and representation of racial/ethnic minority participants in trials cited in the 2018 American Multi-society Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol.

Two authors (A.S, A.V) reviewed the 2018 US cholesterol guidelines for all cited randomized clinical trials (RCTs) describing participant randomization and post-randomization outcomes. We examined manuscripts and supplementary material for participant-level race/ethnicity data. Institutional Review Board approval was not obtained as public manuscripts were reviewed.

RCTs were classified by reporting of NHW, Black, Hispanic, and/or Asian participants, and whether Hispanic or Asian participants were disaggregated. If cohorts consisted of a single race, other group participation was zero. We categorized RCTs by publication year: Before 2000, 2000–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011 or later. For each race/ethnicity, we pooled participation rates among trials that reported participation of that race/ethnicity to determine representation. US census and trial representation were compared by the two-proportion z-test, performed in R, version 4.0.0. Data are available upon request from corresponding author.

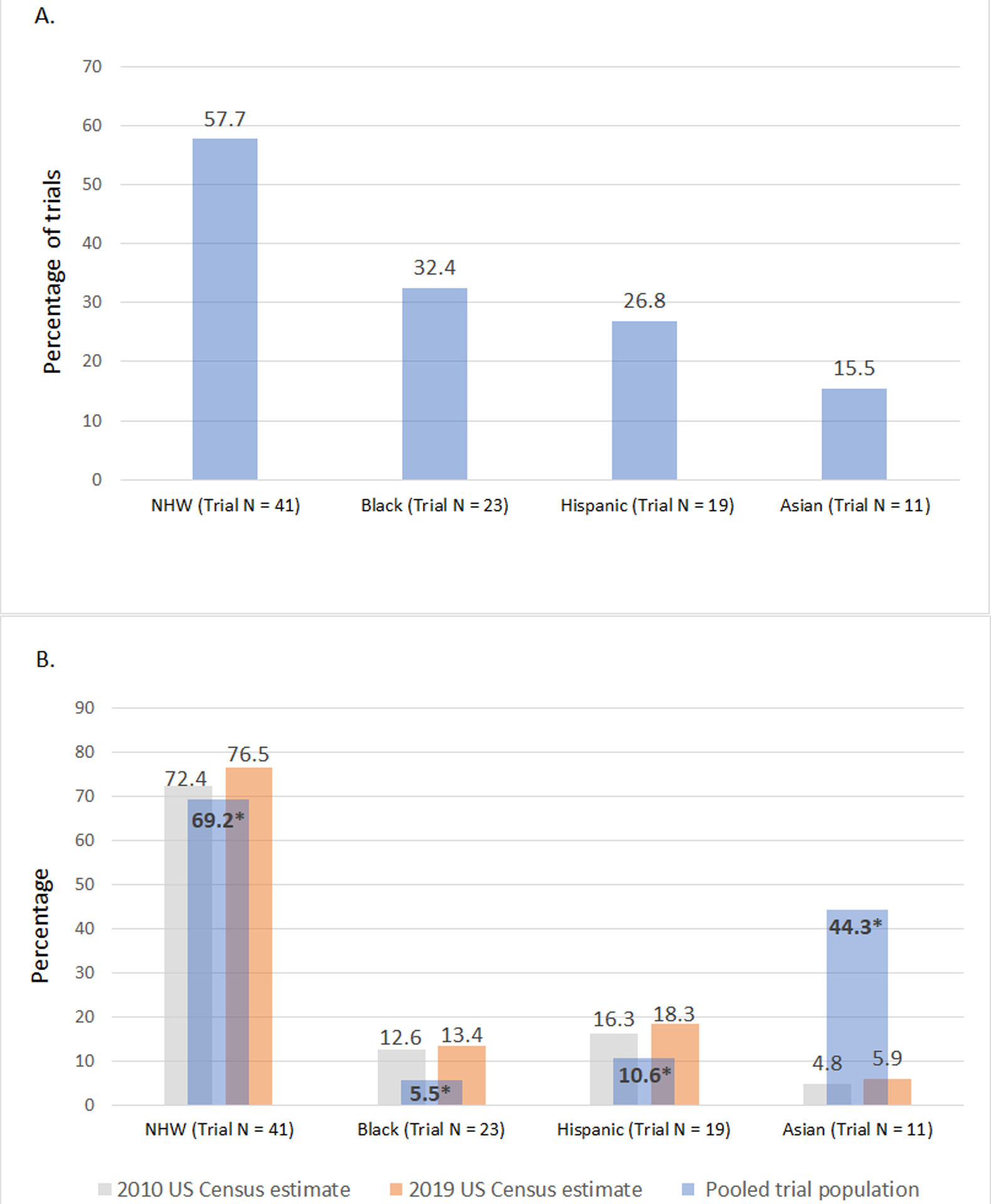

We identified 71 cited RCTs from 1984 through 2017. Only 42 trials (59.1%), from 1997 through 2017, reported participant-level race/ethnicity data. NHW participation was reported in 41 trials (57.7%) (Figure 1A). Black, Hispanic, and Asian participation was reported in 23 (32.4%), 19 (26.8%), and 11 trials (15.5%), respectively. Non-reporting trials were distributed as follows over time: 7 published before 2000, 5 published between 2000 and 2005, 11 published in the 2006–2010 period, and 6 trials published in 2011 or later. Among the 27 trials that reported any Black, Hispanic, or Asian participant-level data, only 8 reported all three. Four disaggregated Asian data further into subgroups, and no studies disaggregated Hispanic data.

Figure 1.

Reporting and representation of racial/ethnic minority participants in randomized trials cited in the 2018 US Multi-society Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. Panel A: Percentage of cited trials reporting specific participant-level race/ethnicity data, Panel B: Racial/ethnic representation among pooled trial participants compared to the US population per 2010 and 2019 US Census estimates.

*P-value <0.001 for trial population versus 2010 and 2019 Census data.

Figure 1B outlines pooled participation rates compared to 2010 and 2019 United States (US) Census representation.3, 4 Black trial participation was only 44% and 41% of expected based on 2010 and 2019 Census representation, respectively (trial: 5.5%, US 2010: 12.6%, US 2019: 13.4%, P<0.001). Hispanic trial participation was 65% and 58% of expected based on 2010 and 2019 US Census representation, respectively (trial: 10.6%, US 2010: 16.3%, US 2019: 18.3%, P<0.001). NHW trial participation, by contrast, was 96% and 90% of expected based on 2010 and 2019 US Census data, respectively (trial: 69.2%; US 2010: 72.4%; US 2019: 76.5%, P<0.001). Asian participation was higher than US census representation.

Among RCTs supporting the 2018 US cholesterol guidelines, 59% of trials reported participant-level race/ethnicity data, with infrequent reporting of Black, Hispanic, and Asian participation and minimal disaggregation. Black and Hispanic patients were significantly under-represented compared to 2010 and 2019 US Census data. These findings have important implications for the real-world applicability of cholesterol RCTs and guidelines.

Under-reporting of race/ethnicity data limits our ability to assess the generalizability of trials and guidelines across diverse populations. Our study suggests that racial/ethnic minority groups are under-reported, likely owing to under-inclusion. Minority representation is critical given disproportionate burden of ASCVD risk factors among specific groups. For example, compared with NHW patients, Black individuals may experience higher post-treatment cholesterol levels.5 Indeed, the 2018 guidelines highlight the importance of race/ethnicity for ASCVD risk and lipid treatment – such as increased statin sensitivity in East Asian patients – and the need to disaggregate racial/ethnic groups. Decreased trial participation may also reflect longstanding structural racism and associated distrust in clinical studies among historically marginalized populations. Adequate trial representation is an important link in understanding and mitigating cardiovascular health inequities.

Our analysis has limitations. We only included trials cited in 2018 guidelines. International trials may have uncertain applicability to US populations. However, the included trials were used to formulate US cholesterol guidelines, so should be analyzed. We were unable to consistently differentiate Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black or White patients due to limited reporting. US Census estimates may include those reporting only one race.3

In conclusion, we found frequent under-reporting of race/ethnicity in trials informing the 2018 American Multi-society Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. Compared to US population demographics per 2010 and 2019 Census estimates, Black and Hispanic trial participants remain significantly under-represented. These factors may indicate structural bias, limit generalizability of cholesterol treatment trial results and guidelines, and should inform efforts to mitigate inequities through standardized reporting and sustained efforts to recruit and retain minority participants.

Funding Sources

Dr. Rodriguez was funded by National Institute of Health grant 1K01HL144607-01 and the American Heart Association/Robert Wood Johnson Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program. Dr. Knowles was funded by National Institute of Health grants U41HG009649 and P30DK116074.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168–3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank AT, Zhao B, Jose PO, Azar KM, Fortmann SP and Palaniappan LP. Racial/ethnic differences in dyslipidemia patterns. Circulation. 2014;129:570–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts. Census.gov. 2018. Available at https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- 4.United States Census Bureau. US Population - 1940 to 2010. Census.gov. 2012. Available at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/cspan/1940census/CSPAN_1940slides.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- 5.Nanna MG, Navar AM, Zakroysky P, Xiang Q, Goldberg AC, Robinson J, Roger VL, Virani SS, Wilson PWF, Elassal J, et al. Association of Patient Perceptions of Cardiovascular Risk and Beliefs on Statin Drugs With Racial Differences in Statin Use: Insights From the Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:739–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]