Abstract

The Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Care of People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, published by the Brazilian Ministry of Health in 2020, includes updates concerning acquired syphilis. The document comprises rapid test use, safety and efficacy of benzathine benzylpenicillin, case follow-up, neurosyphilis clinical and laboratory management, approaching sex partners, assistance and monitoring of diagnosed pregnant women, and syphilis and HIV co-infection specificities, as well as a case notification summary. Health managers and professionals must be continuously trained so as to integrate care and surveillance, to strengthen actions for efficient control of syphilis, to broaden the search for sex partners, and to expand access of most vulnerable populations to health services.

Keywords: Syphilis, Clinical protocols, Diagnosis, Therapeutics

Highlighted excerpt:

Most people with syphilis are asymptomatic; this contributes to the maintenance of the transmission chain. Without adequate treatment of pregnant women with syphilis, severe consequences can occur, such as miscarriage, prematurity, low birth weight, natimortality, and congenital syphilis.

INTRODUCTION

This article summarizes the chapter on acquired syphilis, part of the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines (PDCT) for Comprehensive Care of People with Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI). The PDCT was approved by the National Committee for the Incorporation of Technologies to the Brazilian National Health System (Conitec), through Ordinance no. 42, of October 5, 2018 1 . When writing the Protocol, evidence available in literature for analysis was selected, and discussion among specialists was carried out. The PDCT was updated by the technical group and published in 2020 by the Health Surveillance Department of the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL ASPECTS

Syphilis is an STI caused by the Treponema pallidum bacteria, subspecies pallidum. Transmission is mainly sexual (oral, vaginal, or anal). It can also be transmitted vertically, with a fetal mortality rate higher than 40% 2 .

Most people with syphilis are asymptomatic, which contributes to maintenance of the transmission chain. If the disease is not treated, it can lead to severe systemic complications after many years from the initial infection 3 - 5 . Without adequate treatment of pregnant women with syphilis, severe consequences can occur to the fetus or the conceptus, such as miscarriage, prematurity, low birth weight, natimortality, and early or late clinical congenital syphilis manifestations 6 .

Treponema penetrates the mucous membranes directly or enters through skin injuries. Transmission is higher at the infection’s early stages (primary and secondary syphilis), gradually decreasing over time 5 .

In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 6.3 million new cases of syphilis worldwide, with a 0.5% prevalence in men and women, and regional values varying from 0.1% to 1.6% 7 . In Brazil, a national study 8 in 2016 showed a 0.6% syphilis prevalence in conscript young people, who were called for selection commissions, after the military enlistment stage. A high syphilis prevalence was observed in segments of critical populations in Brazil, such as men who have sex with men (9.9%) 9 , female sex workers (8.5%) 10 , and prisoners (3.8%) 11 .

The acquired syphilis detection rate increased from 59.1 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, in 2017, to 75.8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, in 2018, with a higher increasing trend among the population between 20 and 29 years, from 2010 to 2018, according to data from the Notifiable Diseases Information System (Sinan) 12 .

CLINICAL ASPECTS

To guide treatment and clinical and laboratory follow-up, syphilis infection is divided into the stages of recent syphilis (primary, secondary, and recent latent ones) with one year of evolution, and late syphilis (late latent and tertiary ones), longer than a year 4 .

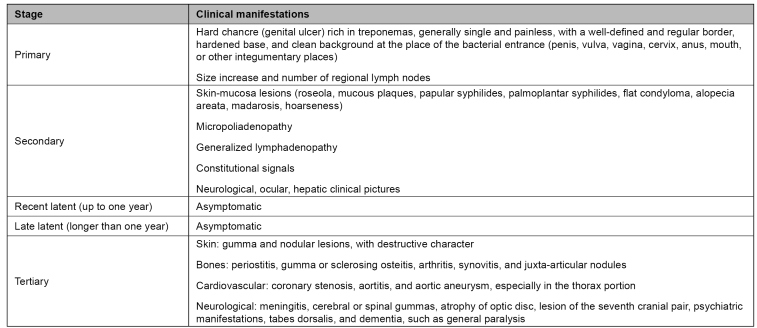

Figure 1 shows the clinical stages of acquired syphilis. At initial phases, symptomatology can vary and disappear, regardless of treatment. Clinical manifestations give room to clinical suspicion, but there is no exclusive signal or symptom; this can lead to misunderstanding concerning other pathologies and make diagnosis more difficult 13 .

FIGURE 1: Acquired syphilis clinical manifestations and stages.

Source: Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2020 13 .

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement can take place at any stage of clinical syphilis 14 . Early neurosyphilis manifests immediately after syphilis infection and meningitis and abnormalities in the cranial nerves 15 , 16 . Due to the era of antibiotics and the dominant use of beta-lactam antibiotics, neurosyphilis' clinical presentation has changed, with oligosymptomatic and atypical clinical pictures of the disease presenting increase 15 .

DIAGNOSIS

To diagnose syphilis, clinical data, results from diagnostic tests, previous investigation history, and investigation on recent risky sexual exposure must be combined 17 . Analysis of sexual history is relevant to diagnosis, and requires professional skills and confidentiality assurance 18 .

Direct examinations and immunological tests are also used for diagnosis of syphilis. Direct examinations are those in which T. pallidum research or detection in biological samples collected directly from primary and secondary lesions is performed 19 .

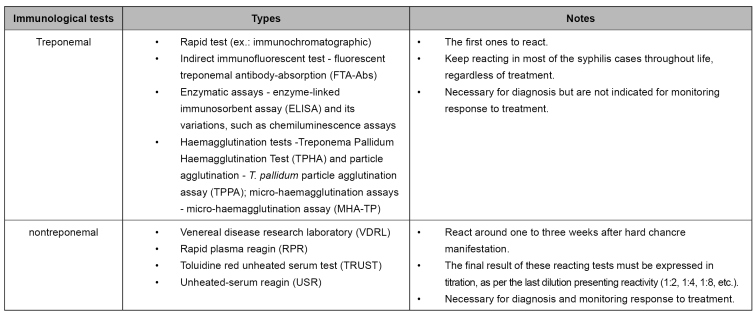

Immunological tests (treponemal and nontreponemal) are the most common in clinical practice for tracking asymptomatic people and diagnosing symptomatic patients 5 . Their characteristic is the research of total antibodies in whole blood, serum, or plasma (Figure 2). Although there is a synthesis of specific IgM antibodies at the initial infection phase, such antibodies are also found in late infection stages; therefore, IgM tests are not recommended on their own 2 , 17 .

FIGURE 2: Immunological test for syphilis diagnosis.

Source: adapted from Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2020 13 .

Treponemal tests detect specific antibodies produced against T. pallidum antigens. For example, rapid tests (immunochromatographic) can be highlighted, and they do not need a laboratory structure. In around 85% of cases, treponemal tests keep reacting throughout life (serological scar), regardless of treatment 19 , which allows for differentiating an active infection from a past one 5 .

Nontreponemal tests, such as the venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), detect anticardiolipin antibodies nonspecific for T. pallidum antigens 19 . They are semi quantitative tests, as, in case of reacting results, dilution of the sample for titration of these antibodies is performed 2 . Such titration may vary, depending on the disease stage and on treatment or lack of it. Low titration (<1:4) of nontreponemal antibodies may be found in the infection’s early and late phases, persisting for months or years. For this reason, there is no specific cut-point, and any titration must be investigated as syphilis 13 . Non-negativity of nontreponemal tests after treatment is called a serological scar. This event can be temporary or persistent, and it can present low or high titration, depending on the initial titration found at the moment of diagnosis 4 , 17 .

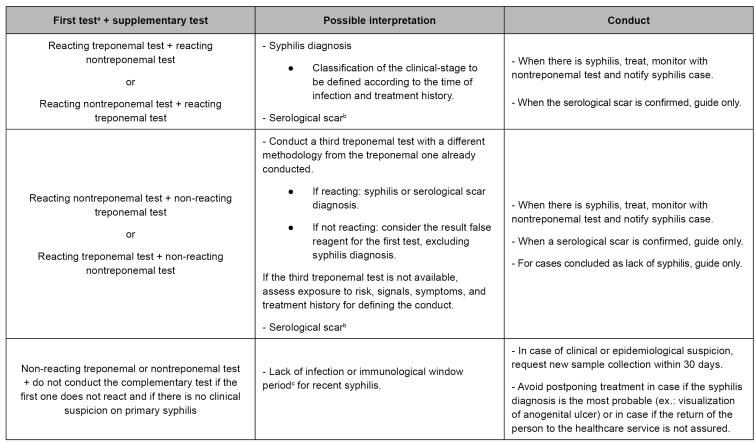

Starting the investigation with a treponemal test, preferably the rapid test, is recommended due to its higher sensitivity 2 , 17 . With the results, there are various combinations of treponemal and nontreponemal tests’ use, with possible interpretation and respective conducts (Figure 3) 13 , 17 .

FIGURE 3: Treponemal and nontreponemal test results, interpretation, and conduct.

Source: adapted from the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2020 13 .

Notes: a) Immediate treatment with benzathine benzylpenicillin after only one syphilis reacting test (treponemal or nontreponemal test) is indicated in situations described in item "Treatment", without exclusion of need for a second test for diagnosis definition; b) Documented previous treatment with titration drop in at least two dilutions; c) Immunological window: the period between infection and sufficient antibody production for immunological test detection.

Healthcare professionals, especially medical and nursing, must explain the purpose of immunological tests in the request form for the laboratory network. In the diagnostic approach, three different situations are considered: syphilis diagnosis, when there is no rapid test in the healthcare service; syphilis diagnosis, after reacting rapid test at the place of service; and treatment follow-up, when the diagnosis and treatment have taken place, and it is needed to monitor the nontreponemal antibody titration for cure control, preferably with the same method used for diagnosis 13 .

There is no gold standard test for neurosyphilis diagnosis. It is based on a combination of clinical findings, alterations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and results of nontreponemal testing in CSF. It is hard to find patients with neurosyphilis who do not present pleocytosis 20 . Although levels of protein in CSF are not sensitive and specific to neurosyphilis diagnosis, protein standardization is essential for post-treatment monitoring 21 - 24 .

TREATMENT

Immediate treatment is recommended, with benzathine benzylpenicillin, following a reacting - treponemal or nontreponemal - test for syphilis in the following cases, regardless of the presence of signs and symptoms: 13 pregnant women; sexual violence victims; people with a chance of follow-up loss (those who will not return to the service); people with signs and symptoms of primary or secondary syphilis; and people without previous syphilis diagnosis.

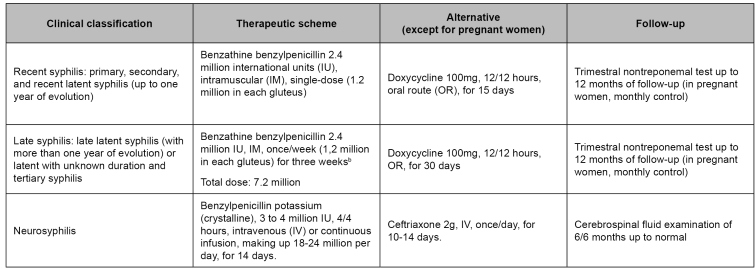

After the first reacting test, treatment does not exclude the need for a second test, clinical and laboratory follow-up, and sex partners’ diagnosis and treatment. There are specific therapeutic schemes as per the clinical classification of syphilis (Figure 4) 13 . Solving signs and symptoms after treatment indicates a response to the therapy. A post-treatment follow-up must be conducted after the nontreponemal test for determining the adequate immune response 25 .

FIGURE 4: Treatment and follow-up of syphilis and neurosyphilis cases.

Source: adapted from Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2020 13 .

Notes: a) Benzathine benzylpenicillin is the only safe and efficient option for adequate treatment of pregnant women. Any other treatment conducted during pregnancy, for purposes of defining the case and therapeutic approach of congenital syphilis, is deemed inadequate treatment for the mother; consequently, the newborn will be notified as having congenital syphilis undergo clinical and laboratory assessment; b) The interval between doses must not be longer than 14 days. In such a case, the scheme must restart 19 .

In order to guarantee availability of benzathine benzylpenicillin, it began to be acquired in a centralized way by the Brazilian Ministry of Health, as a strategic component of the pharmaceutical care in the Essential Medicines National List, from 2017 26 . Notified syphilis cases (acquired and in pregnant women) served as a base for calculating purchase and distribution 13 .

Benzathine benzylpenicillin must be administered through an intramuscular route (IM) 19 . The ventrogluteal region is the preferable place, as it is free from important vessels and nerves, and is a thinner subcutaneous tissue, which implies few adverse effects and less local pain 27 . Thigh vastus lateralis and dorsogluteal regions are other options for application. When application through the IM route is unfeasible in the indicated places due to the presence of silicone (prosthesis or industrial liquid), alternative treatment through oral route is recommended (Figure 4) 13 .

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is an episode that can happen in the first 24 hours after starting treatment with penicillin, mainly in primary and secondary syphilis. Its manifestation exacerbates skin lesions with erythema, pain or pruritus, general discomfort, fever, headache, and arthralgia 28 . Antipyretics can be used for controlling symptoms, but there is no evidence of reaction prevention 4 . People must be warned of the possibility of such benign and self-limited events 29 , and, especially, of the distinction regarding allergy to penicillin 30 .

According to a systematic review with meta-analysis, anaphylaxis risk in using benzathine benzylpenicillin was 0.002%, with the expectation of 0 to 3 cases of anaphylaxis per 100,000 treated patients of 13 studies. There was no anaphylactic reaction or death in the pregnant population due to the use of benzathine benzylpenicillin in 1,244 women, with a reported case of cutaneous rash 31 .

Adrenalin is the medicine chosen for anaphylactic reaction treatment. In this case, primary health care protocol recommendations regarding spontaneous demands and urgency and emergency must be followed 32 .

Healthcare professionals’ fear of adverse reactions arising from penicillin, beyond sporadic anaphylactic reactions, contributes to the loss of the opportune moment for the treatment of people with syphilis; also, it maintains the infection transmission chain and the occurrence of congenital syphilis 13 . Nursing professionals are backed by the Federal Nursing Council on extensive administration of benzathine benzylpenicillin in primary health care 33 , 34 .

From 80% to 90% of self-reported penicillin allergies are expected to be incorrect; it is challenging to differentiate reactions and disease symptoms in most cases 35 . Some specific situations do not characterize allergies, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, pruritus, family history, and suspected reactions that occurred more than ten years ago. Clinical history must be detailed for risk stratification of allergy to penicillin and to obtain adequate information and correct practice definition, preventing unnecessary referrals for desensitization in a hospital environment 36 .

Monitoring response to treatment is mandatory and must be performed throughout the outpatient healthcare network. The drop in immune response markers to T. pallidum evaluation uses as parameter the non-reacting nontreponemal test or the drop in titration in at least two dilutions within up to six months for recent syphilis and drop in titration in at least two dilutions within up to 12 months for late syphilis 4 , 37 - 40 .

The earlier the diagnosis and treatment, the faster the circulating antibodies will disappear, with negativity of nontreponemal tests or stabilizing this titration as low. The titration record of this nontreponemal examination at the beginning of treatment will serve as the base for clinical and laboratory monitoring 17 .

The following are criteria of benzathine benzylpenicillin retreatment: 13 lack of titration reduction in two dilutions within six months (recent syphilis) or 12 months (late syphilis) after adequate treatment (ex.: from 1:32 to 1:8), or titration increase in two or more dilutions (ex.: from 1:16 to 1:64), or clinical signs’ and symptoms’ persistence or recurrence.

In reinfection cases, investigation of neurosyphilis through a lumbar puncture in the general population is recommended when there is no risk of sexual exposure. For people living with HIV, an investigation is recommended in all retreatment cases, regardless of occurrence or not of new exposure. After adequate treatment, when a new risk of sexual exposure during the analyzed period is dismissed, the persistence of reacting results in nontreponemal tests, with previous titration drop in at least two dilutions, is called a serological scar, and does not characterize therapeutic failure 13 .

For neurosyphilis, all people presenting reacting VDRL in CSF must be treated, regardless of neurological or eye signals, and of symptoms. Those presenting non-reacting VDRL in CSF and biochemical alterations in CSF and presence of neurological or eye symptoms or changes in CNS image characteristic for the disease, since other diseases cannot explain such changes, must also be treated. Patients with an initial negative examination in CSF must undergo control fluid puncture as well after six months from the end of treatment (Figure 4) 13 .

In the case of CSF alteration persistence, retreatment with benzathine benzylpenicillin is recommended. In blood samples, the drop in nontreponemal test titration in at least two dilutions or seroreversion for non-reagent may be a parameter to be considered as a response to neurosyphilis, especially in an unavailable lumbar puncture scenario 41 .

SURVEILLANCE, PREVENTION, AND CONTROL

Acquired syphilis has been under compulsory notification in Brazil since 2010, as per Consolidation Ordinance no. 4, of September 28, 2017 42 . Such notification is mandatory for physicians, other healthcare professionals, or those responsible for public and private healthcare services providing care to patients 43 . Thus, the need for timely notification of all cases to Sinan is reinforced to subsidize the formulation and implementation of public STI policies in Brazil.

Between 46% and 60% of the sex partners of people with syphilis (primary and secondary) are estimated to be infected 44 . If there is recent exposure (up to 90 days), even in case the person presents non-reacting immunological tests 4 , the recommendation is the presumptive treatment with a single dose of benzathine benzylpenicillin 2.4 million international units (IU), IM (1.2 million IU in each gluteus). It must be stressed that the clinical assessment and laboratory follow-up are crucial 13 . The approach to the sex partners contributes to decreasing the infection burden in the community, tracking asymptomatic people, and identifying sexual risk networks 45 .

For clinical and laboratory follow-up of people with acquired syphilis, nontreponemal test titration must be conducted every three months up to the 12th follow-up month (3, 6, 9, and 12 months). This monitoring contributes to classifying the response to treatment, identifying possible reinfection, and establishing adequate conduct for each case 13 .

In most laboratory routines, nontreponemal tests are not automatized, which can cause a difference between readings when different methods are used or performed by more than one observer. Thus, variations in dilution titration (ex.: from 1:16 for 1:8) do not have clinical significance. Follow-up is recommended, as possible, using the same diagnostic method 17 .

In the PDCT chapter on acquired syphilis, there is a section on the clinical decision algorithm for syphilis in pregnant women management of (acquired and in pregnant women), with a recommendation summary for case screening, diagnosis, treatment, notification and clinical and laboratory monitoring 13 .

SPECIAL POPULATIONS AND SITUATIONS

Pregnant women

Pregnant women must be tested for syphilis at their first prenatal care appointment (ideally in the first three months), at the beginning of the third trimester, and at the hospitalization for giving birth, in case of miscarriage or natimortality or exposure to risk or sexual violence history. Clinical and laboratory monitoring with nontreponemal testing must be conducted monthly during pregnancy 46 . After birth, this follow-up is trimestral up to the 12th follow-up month 13 .

It is crucial to assure pregnant women and sex partners’ diagnosis and treatment and register the procedure on the prenatal care notebook. Such conducts contribute to avoiding that the newborn undergoes unnecessary biomedical interventions 46 . It is also essential to stimulate the father’s or partner’s participation throughout the prenatal care process for strengthening healthy affection relations 47 .

HIV infections

For all people living with HIV diagnosed with syphilis, appointments with specialists must be early in case of neurological or eye signals or symptoms, and lumbar puncture is a diagnostic imposition. Recommendations for lumbar puncture in people living with HIV to investigate neurosyphilis encompass the presence of neurological or ophthalmologic symptoms, evidence of active tertiary syphilis, and clinical treatment failure, regardless of sexual history 13 .

In HIV infections, syphilis clinical manifestations and therapeutic response can be distinct due to each person's immunity. The presence of multiple chancres, higher frequency of secondary lesions, and Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction can be highlighted 48 , 49 . Diagnosis criteria and treatment of syphilis for people living with HIV are the same for people without HIV infection 4 .

The update of the PCTD chapter on acquired syphilis converges with the need to train health managers and professionals continuously, to integrate care and surveillance, strengthen effective syphilis prevention actions, tracking asymptomatic people, and case diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, and surveillance, in addition to broadening the search for sex partners, and expanding the access of the most vulnerable populations to the health services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the substantial contribution to this work by the technical group of specialists responsible for developing the 2020 PCDT for Comprehensive Care for People with STI.

Referências

- 1.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Diário Oficial da União. Brasília (DF): Oct, 2018. [2020 out 15]. Portaria MS/SCTIE nº 42, de 5 de outubro de 2018. Torna pública a decisão de aprovar o Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Atenção Integral às Pessoas com Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis (IST), no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS. Seção 1:88. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/sctie/2018/prt0042_08_10_2018.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lasagabaster MA, Guerra LO. Syphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019 Jun-Jul;37(6):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2018.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hook EW., 3rd Syphilis. Lancet. 2017 Apr;389(10078):1550–1557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32411-4. Epub 2016 Dec 18. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Mar 9;393(10175):986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. [2020 Oct 15];MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Jun;64(RR-03):1–137. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6403a1.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peeling RW, Mabey D, Kamb ML, Chen X-S, Radolf JD, Benzaken AS. Syphilis. [2020 May 29];Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017 Oct;3:17073–17073. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.73. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/nrdp201773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez GB, Kamb ML, Newman LM, Mark J, Broutet N, Hawkes SJ. Untreated maternal syphilis and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [2020 Oct 15];Bull World Health Organ. 2013 91(3):217–226. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.107623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, Low N, Unemo M, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. [2020 Oct 15];Bull World Health Organ. 2019 Aug;97(8):548–562. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.228486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motta LR, Sperhacke RD, Adami AG, Kato SK, Vanni AC, Paganella MP, et al. Syphilis prevalence and risk factors among young men presenting to the Brazilian Army in 2016: Results from a national survey. [2020 Oct 15];Medicine (Baltimore) (e13309). 2018 Nov;97(47) doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000013309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunha CB, Friedman RK, de Boni RB, Gaydos C, Guimarães MR, Siqueira BH, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and syphilis among men who have sex with men in Brazil. [2020 Oct 15];BMC Public Health. 2015 Jul;15:686–686. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira-Júnior ODC, Guimarães MDC, Damacena GN, Almeida WS, Souza-Júnior PRB, Szwarcwald CL, et al. Prevalence estimates of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and C among female sex workers (FSW) in Brazil, 2016. [2020 Oct 15];Medicine (Baltimore) 2018 May;97(1S Suppl 1):S3–S8. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000009218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correa ME, Croda J, Castro ARCM, Oliveira SMVL, Pompilio MA, Souza RO, et al. High Prevalence of Treponema pallidum Infection in Brazilian Prisoners. [2020 Oct 15];Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017 Oct;97(4):1078–1084. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Doenças de Condições Crônicas e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis Sífilis | 2019. [2020 out 15];Bol Epidemiol. 2019 Oct;(especial) Available from: http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2019/boletim-epidemiologico-sifilis-2019v. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Doenças de Condições Crônicas e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis . Protocolo clínico e diretrizes terapêuticas para atenção integral às pessoas com infecções sexualmente transmissíveis (IST) Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2015. [2020 out 15]. 248. Available from: http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2015/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-para-atencao-integral-pessoas-com-infeccoes. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marra CM. Neurosyphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015 Dec;21(6):1714–1728. doi: 10.1212/con.0000000000000250v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuddenham S, Ghanem KG. Neurosyphilis: knowledge gaps and controversies. [2020 Oct 15];Sex Transm Dis. 2018 Mar;45(3):147–151. doi: 10.1097/olq.0000000000000723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musher DM. Editorial commentary: polymerase chain reaction for the tpp47 gene: a new test for neurosyphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Nov;63(9):1187–1188. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância, Prevenção e Controle das Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis, do HIV/Aids e das Hepatites Virais . Manual técnico para diagnóstico da sífilis. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2016. [2020 out 15]. Available from: http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2016/manual-tecnico-para-diagnostico-da-sifilis. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Çakmak SK, Tamer E, Karadag AS, Waugh M. Syphilis: a great imitator. [2020 Oct 15];Clin Dermatology. 2019 May;37(3):182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization - WHO . WHO Guideline for the treatment of Treponema pallidum (syphilis) Genebra: World Health Organization; 2016. [2020 Jun 6]. 60. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/249572/1/9789241549806-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Dunaway SB, Sahi SK, Tantalo LC. Cerebrospinal fluid Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay for neurosyphilis diagnosis. [2020 Oct 15];J Clin Microbiol. 2017 Jun;55(6):1865–1870. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00310-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marra CM, Critchlow CW, Hook EW, Collier AC, Lukehart SA. Cerebrospinal fluid treponemal antibodies in untreated early syphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Arch Neurol. 1995 Jan;52(1):68–72. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540250072015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merritt HH, Adams RD, Solomon HC. Neurosyphilis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooshmand H, Escobar MR, Kopf SW. Neurosyphilis. A study of 241 patients. [2020 Oct 15];JAMA. 1972 Feb;219(6):726–729. doi: 10.1001/jama.219.6.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musher DM. Editorial commentary: polymerase chain reaction for the tpp47 gene: a new test for neurosyphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Nov;63(9):1187–1188. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seña AC, Wolff M, Behets F, Martin DH, Leone P, Langley C, et al. Rate of decline in nontreponemal antibody titers and seroreversion after treatment of early syphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Sex Transm Dis. 2018 Jan;44(1):6–10. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000541v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Ciência, Tecnologia e Insumos Estratégicos. Departamento de Assistência Farmacêutica e Insumos Estratégicos . Relação nacional de medicamentos essenciais: RENAME 2017. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2017. [2020 out 15]. 210. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/relacao_nacional_medicamentos_rename_2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conselho Federal de Enfermagem - COFEN (BR) Parecer nº 09/2016/CTAS/COFEN, de 6 de maio de 2016. Solicitação de parecer sobre a administração de medicamentos por via IM em pacientes que usam prótese de silicone. Brasília: COFEN; 2016. [2020 out 15]. Available from: http://www.cofen.gov.br/parecer-no-092016ctascofen_42147.html. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler T. The jarisch-herxheimer reaction after antibiotic treatment of spirochetal infections: a review of recent cases and our understanding of pathogenesis. [2020 Oct 15];Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017 Jan;96(1):46–52. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arando M, Fernandez-Naval C, Mota-Foix M, Alvarez A, Armegol P, Barberá MJ. The jarisch-herxheimer reaction in syphilis: could molecular typing help to understand it better? [2020 Oct 15];J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018 Oct;32(10):1791–1795. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.See S, Scott EK, Levin MW. Penicillin-induced Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. [2020 Oct 15];Ann Pharmacother. 2005 Dec;39(12):2128–2130. doi: 10.1345/aph.1g308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galvao TF, Silva MT, Serruya SJ, Newman LM, Klausner JD, Pereira MG, et al. Safety of benzathine penicillin for preventing congenital syphilis: a systematic review. [2020 May 20];PLoS One. 2013 8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica . Acolhimento à demanda espontânea: queixas mais comuns na Atenção Básica. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2013. [2020 out 15]. (Cadernos de Atenção Básica, n. 28, v. II). Available from: https://aps.saude.gov.br/biblioteca/visualizar/MTIwNA== [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conselho Federal de Enfermagem - COFEN (BR) Decisão nº 0094/2015, de 8 de julho de 2015. Revoga o Parecer de Conselheiro 008/2014. PAD COFEN 032/2012. Administração de penicilina pelos profissionais de enfermagem. Brasília: COFEN; 2015. [2020 out 15]. Available from: http://www.cofen.gov.br/decisao-cofen-no-00942015_32935.html?undefined=undefined. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conselho Federal de Enfermagem - COFEN (BR) Nota Técnica COFEN/CTLN nº 03/2017, de 14 de junho de 2017. Esclarecimento aos profissionais de enfermagem sobre a importância da administração da Penicilina Benzatina nas Unidades Básicas de Saúde (UBS) do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS) Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2017. [2020 out 15]. Available from: http://www.cofen.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/NOTA-TÉCNICA-COFEN-CTLN-N°-03-2017.pdfv. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solensky R. Allergy to ß-lactam antibiotics. [2020 Oct 15];J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 130(6):1442–2.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. [2020 Oct 15];JAMA. 2019 Jan;321(2):188–199. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, Mooney D, Love EJ. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Ann Intern Med. 1991 Jun;114(12):1005–1009. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-12-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong ML, Lin LR, Liu GL, Zhang HL, Zeng YL, Zheng WH, et al. Factors associated with serological cure and the serofast state of HIV-negative patients with primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary syphilis. [2020 Oct 15];PLoS One. 2013 Jul;8(7):e70102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clement ME, Okeke NL, Hicks CB. Treatment of syphilis. [2020 May 30];JAMA. 2014 Nov;312(18):1905–1917. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang RL, Wang QQ, Zhang JP, Yang LJ. Molecular subtyping of Treponema pallidum and associated factors of serofast status in early syphilis patients: Identified novel genotype and cytokine marker. [2020 Oct 15];PLoS One. 2017 Apr;12(4):e0175477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Tantalo LC, Sahi SK, Lukehart SA. Normalization of serum rapid plasma reagin titer predicts normalization of cerebrospinal fluid and clinical abnormalities after treatment of neurosyphilis. [2020 Oct 15];Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Oct;47(7):893–899. doi: 10.1086/591534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Diário Oficial da União. Brasília (DF): Oct, 2017. [2020 out 15]. Portaria de Consolidação MS/GM nº 4, de 28 de setembro de 2017. Consolidação das normas sobre os sistemas e os subsistemas do Sistema Único de Saúde . Seção 1:288. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2017/prc0004_03_10_2017.html. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brasil. Presidência da República . Diário Oficial da União. Brasília (DF): Oct, 1975. [2020 out 15]. Lei nº 6.259, de 30 de outubro de 1975. Dispõe sobre a organização das ações de Vigilância Epidemiológica, sobre o Programa Nacional de Imunizações, estabelece normas relativas a notificação compulsória de doenças, e dá outras providências. Seção 1:14433. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l6259.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schober PC, Gabriel G, White P, Felton WF, Thin RN. How infectious is syphilis? [2020 Oct 15];Br J Vener Dis. 1983 Aug;59(4):217–219. doi: 10.1136/sti.59.4.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N, Unemo M, Tiplica GS, Potocnik M, et al. 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. [2020 Oct 15];J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Dec;28(12):1581–1593. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Doenças de Condições Crônicas e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis . Protocolo clínico e diretrizes terapêuticas para prevenção da transmissão vertical do HIV, sífilis e hepatites virais. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2015. [2020 out 15]. 248. Available from: http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2015/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-para-prevencao-da-transmissao-vertical-de-hiv. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Coordenação Nacional de Saúde do Homem . Guia do pré-natal do parceiro para profissionais de saúde. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2016. [2020 out 15]. 55. Available from: https://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2016/agosto/11/guia_PreNatal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hutchinson CM, Hook EW III, Shepherd M, Verley J, Rompalo AM. Altered clinical presentations and manifestations of early syphilis in patients with human immunodeficiency vírus infection. [2020 Oct 15];Ann Intern Med. 1994 Jul;121(2):94–99. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-2-199407150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rolfs RT, Joesoef MR, Hendershot EF, Rompalo AM, Augenbraun MH, Chiu M, et al. The syphilis and HIV Study Group. A randomized trial of enhanced therapy for early syphilis in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. [2020 Oct 15];N Engl J Med. 1997 Jul;337(5):307–314. doi: 10.1056/nejm199707313370504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]