Abstract

The topic of vaginal discharge is one of the chapters of the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Health Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, published by the Brazilian Ministry of Health in 2020. The chapter has been developed based on scientific evidence and validated in discussions with specialists. This article presents epidemiological and clinical aspects associated with vaginal discharge conditions, as well as guidance to health service managers and health professionals. Screening, diagnosing, and treating these conditions, the main complaints among women seeking health services, caused by infectious or non-infectious factors, also are presented. Besides, information is presented on surveillance, prevention, and control actions to promote knowledge of the problem and provide quality care and effective treatment.

Keywords: Vaginitis, Candidiasis, Vulvovaginal, Vaginosis, Bacterial, Trichomonas Infections, Sexually transmitted diseases

Highlighted excerpt:

In healthcare servicing cases of sexually transmitted infections, vaginal discharge is the main referred symptom, common among pregnant women.

INTRODUCTION

This article approaches the chapter on infections causing vaginal discharge in the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Health Care (PDCT) for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI), published by the Health Surveillance Department of the Brazilian Ministry of Health. For elaborating the PCDT, a selection and analysis of the evidence available in the literature were performed, and a panel of specialists discussed it. The document was approved by the National Committee for Technology Incorporation to the Brazilian National Health System (Conitec) and updated by the team of specialists in STI in 2020 1 .

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL ASPECTS

In clinics addressing STI cases, vaginal discharge is the main referred symptom 2 - 4 , being also a frequent complaint in pregnant women 5 - 7 . Non-infectious causes of vaginal discharge include excessive elimination of physiological mucous material, presence of intravaginal foreign objects, and atrophic vaginitis. It can occur in women after menopause, during breastfeeding, or as an effect of local radiotherapy in oncology treatment 4 , 7 , 8 . Other situations can cause vulvovaginal pruritus without discharge, such as allergic or irritant dermatitis (soap, perfume, and latex) or skin diseases (atopic dermatitis, lichen, and psoriasis) 8 .

Among the infectious causes of vaginal discharge, women can simultaneously present infection by more than one etiologic agent, which causes nonspecific aspect discharge 4 . The agents can be associated with vaginitis or vaginosis, depending on the existence or nonexistence of the inflammatory process. These are conditions of the vulvovaginal stratified epithelium. The most frequent etiologic agents are fungi (mainly Candida albicans), anaerobic bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis, and protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. There can also be cytolytic vaginosis, dysbiosis arising from a significant increase in lactobacilli and the lytic action on squamous cells 4 , 9 , and the possibility of mixed vaginitis.

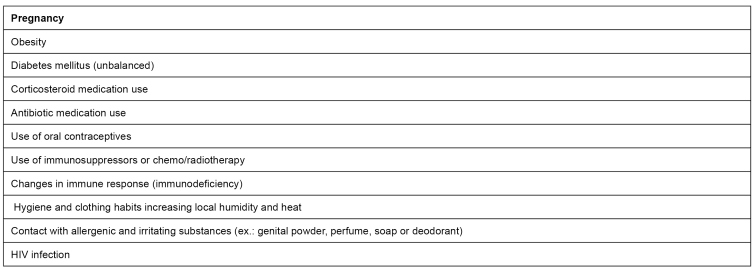

C. albicans is the etiological agent of vulvovaginal candidiasis in 80% to 92% of cases; non-albicans species (Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, Candida parapsilosis) and Saccharomyces cerevisae are less prevalent 9 . Over reproductive life, 10 to 20% of women will be colonized by Candida sp. in an asymptomatic way, not requiring treatment, as yeast can be part of the vaginal environment 10 , 11 . Among factors predisposing vulvovaginal candidiasis, the ones indicated in Figure 1 are highlighted. Vulvovaginal candidiasis is classified as non-complicated and complicated. The first one occurs when all following criteria are present: mild/moderate symptoms and rare frequency; C. albicans as an etiologic agent; and lack of comorbidities. Complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis takes place when at least one of the following criteria are present: intense symptoms; recurrence of four or more episodes in a year; non-albicans etiologic agent (C. glabrata, C. kruzei); presence of comorbidities such as diabetes and human immunodeficiency virus, HIV; or pregnancy 4 , 11 . Most vulvovaginal candidiasis is not complicated and respond to different treatments. Nevertheless, we observe the recurrent form of this disease in 5% of women 11 , 12 .

FIGURE 1: Factors predisposing vulvovaginal candidiasis.

Source: adapted from the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Health Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2020 22 .

Bacterial vaginosis is the most frequent abnormality in the lower genital tract among women in reproductive age. It is the most prevalent cause of vaginal discharge with fetid odor. It is associated with the reduction of lactobacillus and the growth of several anaerobic and facultative bacteria, such as Gram-variable short bacilli, short Gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobic Gram-negative cocci, with variation, mainly Gardnerella, Atopobium, Prevotella, Megasphaera, Leptotrichia, Sneathia, Bifidobacterium, Dialister, Mobiluncus, Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma and three species of Clostridium known as bacterial vaginosis associated bacteria, BVAB 1 to 3 13 . Certain changes in vaginal microbiome (dysbiosis) can be associated to higher frequency of bacterial vaginosis. A study on the characteristics of Brazilian women’s microbiome in reproductive age showed the microbiome type (community-state types, CST) corresponding to CST IV, with depletion of lactobacillus and growth in vaginal pH in 27.4%, with bacterial vaginosis present in 79.6% of the cases 14 .

Trichomonas infections are the most common non-viral STI, being present in 140 million people in the world. A flagellated parasite causes it, T. vaginalis 15 , that causes changes to the vaginal microbiome, growth of local inflammatory response, and relevant reduction in the number of Lactobacillus sp. Trichomonas infections are associated with an increasing of the probability of HIV transmission 16 .

In some cases, there is a growth of lactobacillus, with great destruction of intermediate squamous cells (cytolysis), associated with genital irritative symptoms 17 . It is cytolytic vaginosis, a situation that is usually cyclic in women in reproductive years 16 , with a prevalence of 1% to 7%, most frequent for 25 and 40 years 17 , 18 .

Mixed vaginitis is a condition in which two pathogens are causing vulvovaginal symptoms. They can be pathogens with vaginal pH preferences equal to or not to one another. There can be, for example, vaginitis caused by T. vaginalis associated with bacterial vaginosis 19 . Notwithstanding, the most frequent form of mixed vaginosis is the association of Candida infection with bacterial vaginosis. Its frequency varies between 7% and 22% of vaginal discharge cases, depending on the diagnosis method used 20 .

CLINICAL ASPECTS

Vaginal infection and dysbiosis can be associated with different discharge forms, pruritus, irritation, and pain 21 . Hence, it is essential always to identify, in anamnesis, aspects related to consistency, color, and modifications in vaginal discharge, in addition to the presence of pruritus, local irritation and smell. The investigation of clinical history must be detailed, encompassing information on sexual behavior and practices, date of last menstrual period, vaginal hygiene practices, use of topical or systemic medication and other possible local irritating agents, in addition to comorbidities such as diabetes and HIV infection 22 . During the gynecologic examination, the healthcare professional must identify characteristics of vaginal flow as observed in speculum examination and alterations present, such as inflammation (colpitis), ulcer, edema, and erythema 22 .

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Characteristic signs of vulvovaginal candidiasis are erythema, vulvar fissures, clumpy discharge, white plates stuck to the vaginal wall, vulvar edema, excoriations, etc., satellite lesions, which can become pustules through intense scratching 8 . Usually, there is an association between vaginitis and vulvitis, although such conditions can also take place separately. Clinically, vulvovaginal candidiasis can associate with vaginal introitus dyspareunia and external dysuria due to irritation and local lesions 21 .

Bacterial vaginosis

On the other hand, in bacterial vaginosis, women present homogeneous and fluid vaginal discharge, frequently with fetid odor. Unbalances in the vaginal microbiome have been identified as an alteration often associated with some STIs, including HIV, complications in gynecological surgeries, and pregnancy (premature rupture of membrane, chorioamnionitis, prematurity, and post-cesarean endometritis). When it is present during invasive procedures, such as uterine curettage, endometrial biopsy, and insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD), bacterial vaginosis can increase pelvic inflammatory disease risk 13 . The condition has also been associated with higher risk of human papillomavirus (HPV), and precancerous cervical lesions 23 . The reduction of commensal lactobacillus is associated with increased vaginal pH and the growth of anaerobic microbiota, with amino production (putrescine, cadaverine, and trimethylamine) that become volatile when mixed with substances of alkaline pH, releasing these enzymes to the environment and producing an unpleasant odor. This situation happens particularly after intercourse and menstruation (which alkalinizes vaginal contents), contributing to women’s main complaint. In speculum examination, we can observe that the vaginal walls are brown, most integral, and homogeneous to Schiller’s test, bathed in pearly bubbly discharge 24 .

Trichomonas infections

Signals and symptoms of trichomonas infections are comprised of greenish-yellow, sometimes grayish, bubbly, and foamy intense vaginal discharge, with fetid odor and possible pruritus. It can occur bleeding in sexual intercourse and dyspareunia associated with the inflammatory process in more serious cases. It can also occur vulvar edema and urinary symptoms, such as dysuria 25 . Most of the cases of trichomonas infections are asymptomatic and stay without diagnosis or treatment 26 . Although the process is not entirely comprehended, and the protozoan can make easier the transmission of other more aggressive infectious agents, facilitate the evolution to pelvic inflammatory disease and bacterial vaginosis. In pregnancy, when it is not treated, it can be associated with premature rupture of the membranes 27 . In speculum examination, microulcerations are commonly seen in the cervix, similarly to the aspect of a strawberry or raspberry (Schiller’s test with “tiger” or “leopard” aspect). Trichomonas infections can be associated with bacterial vaginosis in an anaerobic environment, with amines being volatilized with its suggestive odor 15 .

Cytolytic vaginosis

In cases of cytolytic vaginosis, at first, the symptoms are very similar to the ones for vulvovaginal candidiasis, when the woman refers to genital irritation associated with a white to yellowish-white vaginal discharge with lumps, but frequently with cyclic behavior 9 .Speculum examination shows white, milky, and lumpy vaginal content stuck to the vaginal walls. Vaginal pH is presented as lower than 4.5, and the test for amines shows negative 18 . On the other hand, in mixed vaginitis, the clinical picture varies, depending on the agents encompassed. In bacterial vaginosis and candidiasis, both odorous discharge and genital pruritus can be the chief complaint 19 .

DIAGNOSIS

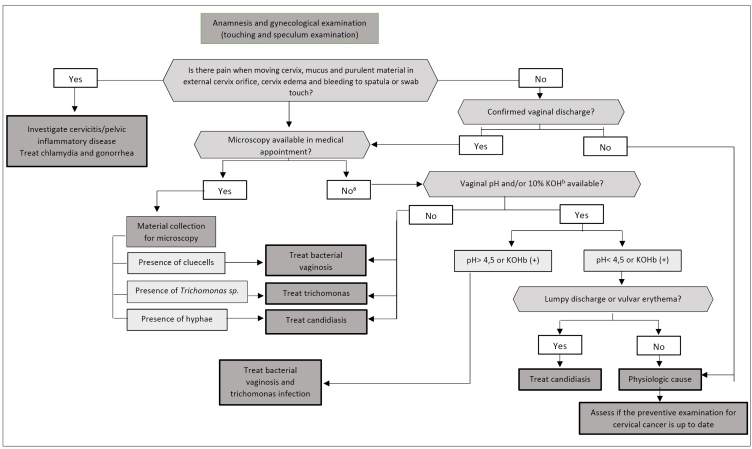

Clinical management of women with vaginal discharge is presented in Figure 2. For diagnosis clarification of the agents causing vaginal flow, we need anamnesis and supplementary examinations 19 .

FIGURE 2: Recommendations for handling vaginal discharge.

Source: adapted from the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Health Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2020 22 .

Note: a) When the collection is conducted for microscopy through Gram-staining, consider the result for managing the case; b) potassium hydroxide.

Vulvovaginal candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis diagnosis must be confirmed through laboratory examinations. The simplest one is the microscopic examination of fresh vaginal content. In this procedure, a sample of the material collected from the vaginal wall is placed on a plate. One to two drops of saline or 10% potassium hydroxide for better evidencing morphotypes of yeasts are added 28 . In addition to this examination, another simple method and low-cost is the Gram-stained vaginal smear bacterioscopy 29 . In cases of recurrent candidiasis, a culture for fungi can be needed (Sabouraud, Nickerson’s, or Microstix-Candida media) in a vaginal sample, aiming at identifying the species of fungi 30 . For a differential diagnosis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, we must consider lichen sclerosus, vulvar vestibulitis, vulvar dermatitis, vulvodynia, cytolytic vaginitis, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, atypical forms of genital herpes, and hypersensitivity reactions 11 .

Bacterial vaginosis

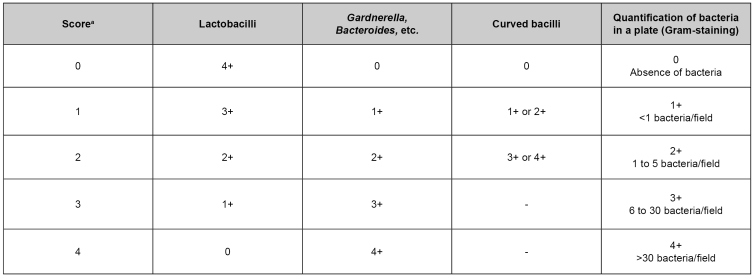

Bacterial vaginosis diagnosis is based on Amsel’s criteria 31 , with the need for the diagnosis, complying with three of the four following criteria: pH higher than 4,5; grayish and homogeneous vaginal discharge; positive amine discharge; and identification of clue cells in microscopic examination. The Nugent score has replaced this diagnosis criterion 13 , 32 . Both criteria can be associated, although the gold pattern is the Nugent laboratory procedure, using Gram staining and objective score system, indicated as evidence II-2 32 , 33 . This evaluation attributes a score for three morphotypes: lactobacilli, Gram-variable coccobacilli, and Gram-negative curved bacilli. After the sum of all agents’ scores, 7-10 indicates bacterial vaginosis, 4-6 is intermediate, and 0-3 is normal 32 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: Nugent score for bacterial vaginosis diagnosis.

Source: Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Health Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections 2020 22 .

Note: Result interpretation: 0 to 3 - negative for bacterial vaginosis; 4 to 6 - changed microbiota; 7 or more - bacterial vaginosis.

Trichomonas infections

In trichomonas infections, the most used laboratory microbiological diagnosis in clinical practice is the microscopic examination of fresh vaginal content in saline, observing the parasite in the microscope. The protozoan movement, a flagellated one, can be seen, as well as a significant number of leukocytes. pH is almost always higher than 5.0 29 . In most cases, the test for amines is positive, and we can observe Gram-negative bacteria in bacterioscopy when there are tests for diagnosis with Gram-staining. On the other hand, T. vaginalis is a flagellated protozoan stained through Papanicolaou or Giemsa techniques. Culture can be requested in cases of challenging diagnosis. Culture media vary, and they can include Diamond’s, Trichosel, and InPouch TV 34 . The diagnosis can also be conducted with molecular biology through a polymerase chain reaction, PCR, including multiplex tests that can detect more than one pathogen and allow for identifying even asymptomatic cases 15 , due to its high sensitivity.

The current pattern of diagnosis test for vulvovaginitis depends on the structure available at the place of attendance. Most of the diagnoses are conducted empirically and based on clinics, although the availability of a microscope for fresh examination is an important supplementary examination. Molecular tests directed to bacterial vaginosis diagnosis, Candida sp. and T. vaginalis can improve diagnostic accuracy and reduce result time compared to culture 35 , 36 . This can be especially important for bacterial vaginosis, which encompasses multiple organisms in vaginal microbiota 37 .

Cytolytic vaginosis

Cytolytic vaginosis diagnosis must comply with the following criteria: white discharge, pruritus or genital burning, vaginal pH between 3.5 and 4.5, and examination of fresh vaginal content without any pathogen, with identification of a significant population of medium bacilli, some naked nuclei, and cell detritus 38 . Gram bacterioscopy and Papanicolaou examination can present the same microscopic findings 22 .

In cases of mixed vaginitis, the presence of two microorganisms in the same moment not necessarily implies that both are pathogenic, especially when it comes to bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis, considering that both yeast and bacteria in bacterial vaginosis not always cause the disease. Therefore, it is important to differentiate between mixed vaginitis and co-occurrence 18 . In the first case, both the agents are pathogenic, which does not necessarily occur in the second case, as the change in the vaginal microbiome can be the agent causing a recurrence. More advanced methods, such as PCR, can lead to inconclusive results if they are not correctly interpreted. Cases with bacterial vaginosis criteria presenting identified inflammatory infiltration were sometimes identified as suggesting a picture of mixed vaginitis 39 . The association can be observed using fresh examination, bacterioscopy, cytology, or molecular biology 40 .

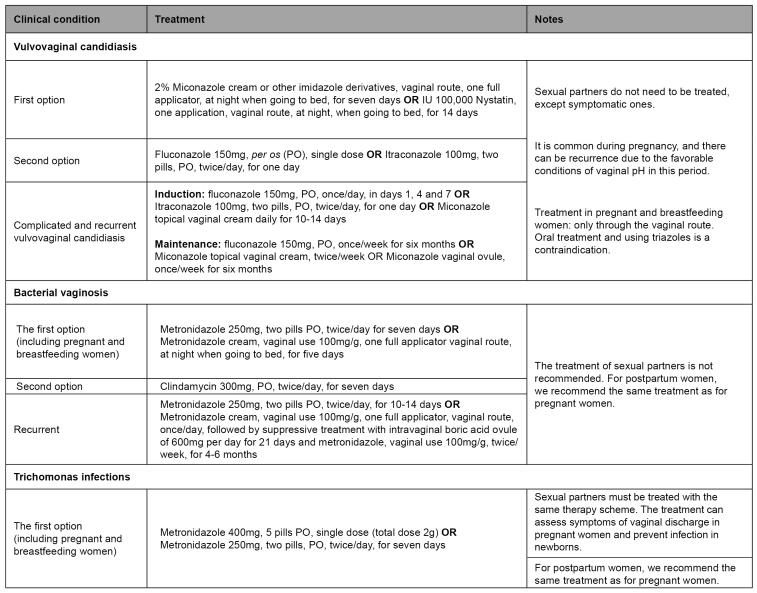

Treatment

Options for treating the vulvovaginitis caused by Candida, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomonas infections are described in Figure 4. It is crucial to suspend sexual relations to prevent contaminations during treatment, which must be kept during the menstrual period. In the treatment with metronidazole, drinking alcoholic beverages must be avoided, due to the antabuse effect, caused by the interaction with imidazole derivatives with alcohol and characterized by discomfort, nausea, vertigo, and a metallic taste in the mouth 22 .

FIGURE 4: Treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomonas infections.

Source: adapted from the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for Comprehensive Health Care for People with Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2020 22 .

Cytolytic vaginosis is treated through using sodium bicarbonate 38 in vaginal baths (15g to 30g of sodium bicarbonate in 0.5L of warm water), twice to three times a week, for two to six weeks 18 . The treatment on cases of mixed vaginitis uses concomitant therapy for each of the pathogens. In case of candidiasis and vaginosis, using antifungal medications with metronidazole is recommeded 19 .

It is essential to highlight that trichomonas infections can change the evaluation of oncological cytology. In cases in which cellular morphological alterations and trichomonas infections, the treatment must be conducted, and the cytology repeated after three months to identify if the changes persist 22 . In recurrent bacterial vaginosis, the triple regime (use of metronidazole cream for ten days, followed by boric acid for 21 days and maintenance with metronidazole cream twice a week, for four to six months) seems successful albeit requiring validation by randomized and controlled clinical assays. The role of boric acid is to remove the bacterial biofilm formed on the vaginal wall that facilitates the persistence of such a picture 41 .

In the vulvovaginal candidiasis cases that are recurrent or difficult to control, we must investigate predisposing systemic causes, such as diabetes, immunodepression (including HIV infection), and the use of corticosteroids. Among the rare adverse reasons (0.01% to 0.1%) of fluconazole use, we can cite agranulocytosis, leukopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anaphylaxis, angioedema, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypokalemia, toxicity, and hepatic insufficiency; for this reason, it is essential to investigate liver functioning 29 .

There is no recommendation for screening bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic women. The treatment is recommended for all symptomatic women with the potential risk of complications, as before IUD insertion, gynecological surgeries, and invasive examinations of the genital tract. The treatment must be simultaneous to the procedure, with no reason for suspension or delay 22 . Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis after treatment is common: around 15% to 30% of women present symptoms for the period of 30 to 90 days after antibiotics therapy, while 70% of women experience a recurrence within nine months 42 , 43 . Some factors justify the lack of therapeutic response to the conventional schemes; among them, frequent sexual activity with no use of condoms, vaginal douche, UID use, improper immune response, and bacterial resistance to imidazole medication. Strains of Atopobium vaginae resistant to metronidazole medication are identified in different women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis; however, such bacilli are sensible to clindamycin and cephalosporins 22 , 41 .

The recurrence of infection by T. vaginalis, whose cause is still not clear, occurs between 5% and 31% of treated women. We need to assess the partner’s treatment, the exposure to new partners, and, finally, the therapeutic failure 44 . Treatment with a single dose and the presence of HIV infection seem to be the factors most associated with therapeutic failure 45 . The molecular mechanism of clinical resistance by T. vaginalis is not clear 44 .

In the follow-up of women with Candida infections, we can observe an increased frequency of recurrences in the presence of changes in cell immunity, such as in women living with HIV or diabetes and those with Candida non-albicans infections. In combination with behavioral changes, prolonged treatment has been used with some response in the treatment of recurrences 46 .The etiological diagnosis is vital in recurrence cases, aiming at identifying the species present and confirm fungal infection, considering the existence of differential diagnoses such as cytolytic vulvovaginitis, allergic reactions, and mixed infections 47 .

SURVEILLANCE, PREVENTION, AND CONTROL

STI diagnosis, different from endogenous and iatrogenic infections, implies the need for guidance and treatment of sexual partners. It is essential to assess the woman’s perception of the existence of physiological vaginal discharge and recommend investigating other STI 22 .

The treatment of sexual partners, when recommended, must be conducted ideally face-to-face, with the due guidance, request of examinations for diagnosis of other STI and identification, summoning and treatment of other different sexual partners, aiming at blocking the chain of infection 22 . In trichomonas infections, as it is an STI, we recommend treating the sexual partners with the same therapeutic scheme as the diagnosed case 47 . In cases of bacterial vaginosis, the sexual partners do not need to be treated. In situations of vulvovaginal candidiasis, the partners only need to be treated if they present symptoms. However, we need to emphasize the role of counseling to the sexual partners 22 .

Cases of infections causing vaginal discharge do not present compulsory notification at the national level, and trichomonas infections can be included, if it is considered convenient, in the list of reports of municipalities and states.

SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Pregnant women

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy, and there can be recurrence due to the favorable conditions of vaginal pH in this period. The treatment in pregnant and breastfeeding women must be conducted only through the vaginal route. Oral treatment and the use of triazole medications is contraindication 22 , 48 . Although a systematic review showed a lack of benefits in tracing bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic pregnant women 49 , other studies showed advantages when the disease is associated with other agents 50 . Despite being controversial, there are suggestions for the treatment of asymptomatic pregnant women. The benefit is defined for those with preterm delivery history with comorbidities.

HIV infections

The treatment must be conducted with the usual schemes for vulvovaginal candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomonas infections 22 , but drug interaction between metronidazole and ritonavir must be observed which can increase nausea and vomit occurrence, reducing antiretroviral adherence. To avoid this occurrence, we recommend a two-hour interval between the administrations of both medications. Bacterial vaginosis has also been observed to provide a set of microorganisms that can increase the levels of viral copies of genital HIV and make vulvovaginal candidiasis episodes more severe and complicated 51 .

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge this article’s contribution by the members of the technical group of specialists responsible for developing the PDCT for Comprehensive Health Care for People with STI 2020.

Referências

- 1.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Diário Oficial da União. Brasília (DF): Oct, 2018. [2020 set 4]. Portaria MS/SCTIE nº 42, de 5 de outubro de 2018. Torna pública a decisão de aprovar o Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas para Atenção Integral às Pessoas com Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis (IST), no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS. [Internet] Seção I:88. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/sctie/2018/prt0042_08_10_2018.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bastos LM, Passos MR, Tiburcio AS. Gestantes atendidas no setor de doenças sexualmente transmissíveis da Universidade Federal Fluminense. [2020 set 8];JBras Doenças SexTransm. 2000 12(2):5–12. [Internet] Available from: http://www.dst.uff.br. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menezes ML. Validação do fluxograma de corrimento vaginal em gestantes. Campinas, SP: Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 2003. http://www.dst.uff.br/revista16-1-2004/6.pdf tese. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spence D, Melville C. Vaginal discharge. [2020 Sep 8];BMJ. 2007 Nov;335(7630):1147–1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39378.633287.80. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Passos MR, Appolinario MA, Varella RQ. Atendimento de gestantes numa clínica de DST. [2020 set 08];JBrasDoenças SexTransm. 2003 15(1):23–29. [Internet] Available from: http://www.dst.uff.br. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behets FM, Ward E, Fox L, Reed R, Spruyt A, Bennett L, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases are common in women attending Jamaican family planning clinics and appropriate detection tolls are lacking. [2020 Sep 8];Sex Transm Inf. 1998 Jun;74(Suppl 1):S123–S127. [Internet] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10023362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costello Daly C, Wangel AM, Hoffman IF, Canner JK, Lule GS, Lema VM, et al. Validation of the WHO diagnostic algorithm and development of an alternative scoring system for management of women presenting with vaginal discharge in Malawi. [2020 Sep 8];Sex Transm Inf. 1998 Jun;74(Suppl 1):S50–S58. [Internet] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10023354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goje O, Munoz JL. Vulvovaginitis: find the cause to treat it. [2020 Sep 8];CleveClin JMed. 2017 Mar;84(3):215–224. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.84a.15163. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eleutério J, Júnior, Ferreira RN, Freitas SF, Rodrigues FE, Moreira JC. Vaginosecitolítica: novos conceitos. Femina. 1995;23(5):423–424. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holland J, Young M, Lee O. Vulvovaginal carriage of yeasts other than Candida albicans. [2020 Sep 8];SexTransmInfect. 2003 79(3):249–250. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.3.249. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidosis. [2020 Sep 8];Lancet. 2007 Jun;369(9577):1961–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobel JD, Wiesenfeld HC, Martens M, Danna P, Hooton TM, Rompalo A, et al. Main tenance fluconazol e therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. [2020 Sep 8];NEngl J Med. 2004 Aug;351(9):876–883. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa033114. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasioudis D, Linhares IM, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Bacterial vaginosis: a critical analysis of current knowledge. [2020 Sep 8];BJOG. 2017 Jan;124(1):61–69. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14209. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marconi C, El-Zein M, Ravel J, Ma B, Lima MD, Carvalho NS, et al. Characterization of the vaginal microbiome in women of reproductive age from five regions in Brazil. [2020 Sep 8];Sex Transm Dis. 2020 Aug;47(8):562–569. doi: 10.1097/olq.0000000000001204. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graves KJ, Ghosh AP, Kissinger PJ, Muzny CA. Trichomonas vaginalis virus: a review of the literature. [2020 Sep 8];Int J STD AIDS. 2019 Apr;30(5):496–504. doi: 10.1177/0956462418809767. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards T, Burke P, Smalley H, Hobbs G. Trichomonasvaginalis: clinical relevance, pathogenicity and diagnosis. [2020 Sep 8];Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016 May;42(3):406–417. doi: 10.3109/1040841x.2014.958050. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang S, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wang J, Chen S, Li S. Clinical significance and characteristics clinical differences of cytolytic vaginoses in recurrent vulvovaginitis. [2020 Sep 8];Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017 82(2):137–143. doi: 10.1159/000446945. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares R, Vieira-Baptista P, Tavares S. Cytolyticvaginosis: anunder diagnosed pathology that mimics vulvovaginal candidiasis. [2020 Sep 8];Acta Obstet Ginecol Port. 2017 Jun;11(2):106–112. [Internet] Available from: http://www.scielo.mec.pt/pdf/aogp/v11n2/v11n2a07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobel JD, Subramanian C, Foxman B, Fairfax M, Gygax SE. Mixed vaginitis-more than coinfection and with therapeutic implications. [2020 Sep 8];Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013 Apr;15(2):104–108. doi: 10.1007/s11908-013-0325-5. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eleutério J, Júnior, Passos MRL, Giraldo PC, Linhares IM, Carvalho NS. Estudo em citologia em meio líquido (SurePath) da associação de Candida sp. em mulheres com diagnóstico de vaginose bacteriana. [2020 set 8];J Bras Doenças Sex Transm. 2012 24(2):122–123. doi: 10.5533/DST-2177-8264-201224211. [Internet] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - CDC . STD treatment guidelines: diseases characterized by vaginal discharge. Washington, D.C.: CDC; 2015. [2020 Sep 4]. [Internet] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/vaginal-discharge.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Doenças de Condições Crônicas e Infecções Sexualmente Transmissíveis . Protocolo clínico e diretrizes terapêuticas para atenção integral às pessoas com infecções sexualmente transmissíveis (IST) Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2020. [2020 set 4]. 248. [Internet] Available from: http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/pub/2015/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-para-atencao-integral-pessoas-com-infeccoes. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillet E, Meys JF, Verstraelen H, Bosire C, De Sutter P, Temmerman M, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with uterine cervical human papillomavirus infection: a meta-analysis. [2020 Sep 8];BMC Infect Dis. 2011 Jan;11:10–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-10. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hillier SL. Diagnostic microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. [2020 Sep 8];Pt 2Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993 Aug;169(2):455–459. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90340-o. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sood S, Kapil A. An update on trichomonas vaginalis. [2020 Sep 8];Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2008 29(1):7–14. [Internet] Available from: http://www.ijstd.org/article.asp?issn=2589-0557 ;year=2008;volume=29;issue=1 spage=7;epage=14;aulast=Sood. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allsworth JE, Ratner JA, Peipert JF. Trichomoniasis and other sexually transmitted infections: results from the 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. [2020 Sep 8];Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Dec;36(12):738–744. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e3181b38a4b. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mann JR, McDermott S, Gill T. Sexually transmitted infection is associated with increased risk of preterm birth in South Carolina women insured by Medicaid. [2020 Sep 8];J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010 Jun;23(6):563–568. doi: 10.3109/14767050903214574. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hainer BL, Gibson MV. Vaginitis: diagnosis and treatment. [2020 Sep 8];Am Fam Physician. 2011 Apr;83(7):807–815. [Internet] Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0401/p807.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paladine HL, Desai UA. Vaginitis: diagnosis and treatment. [2020 Sep 8];Am Fam Physician. 2018 Mar;97(5):321–329. [Internet] Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/0301/p321.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. [2020 Sep 8];Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Mar;48(5):503–535. doi: 10.1086/596757. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. [2020 Sep 8];Am J Med. 1983 Jan;74(1):14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Realibility of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis in improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. [2020 sep 8];J Clin Microbiol. 1991 Feb;29(2):297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [Internet] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC269757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Schalkwyk J, Yudin MH. Infectious Diseases Committee Vulvovaginitis: screening for and management of trichomoniasis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and bacterial vaginosis. [2020 Sep 8];J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015 Mar;37(3):266–274. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(15)30316-9. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haefner HK. Current evaluation and management of vulvovaginitis. [2020 Sep 8];Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Jun;42(2):184–195. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199906000-00004. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kusters JG, Reuland EA, Bouter S, Koenig P, Dorigo-Zetsma JW. A multiplex real-time PCR assay for routine diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. [2020 Sep 8];Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015 Sep;34(9):1779–1785. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2412-z. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwebke JR, Gaydos CA, Nyirjesy P, Paradis S, Kodsi S, Cooper CK. Diagnostic performance of a molecular test versus clinician assessment of vaginitis. [2020 Sep 8];J Clin Microbiol. 2018 May;56(6):e00252-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00252-18. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasan S, Fredricks DN. The human vaginal bacterial biota and bacterial vaginosis. [2020 Sep 8];Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2008 Feb;:750479. doi: 10.1155/2008/750479. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cibley LJ, Cibley LJ. Cytolyticvaginosis. [2020 Sep 8];Pt 2Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Oct;165(4):1245–1249. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(12)90736-X. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eleuterio J, Júnior, Eleuterio RMN, Martins LA, Giraldo PC, Gonçalves AKS. Inflammatory cells in liquid-based cytology smears classified as bacterial vaginosis. [2020 Sep 8];Diagn Cytopathol. 2017 Dec;45(12):1100–1104. doi: 10.1002/dc.23830. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eleutério J, Júnior, Eleuterio RMN, Valente ABGV, Queiroz FS, Gonçalves AKS, Giraldo PC. Comparison of BD affirm VPIII with gram and liquid-based cytology for diagnosis of bacterial vaginoses, candidiasis and Trichomonas. [2020 Sep 8];Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Mar;66(1):32–35. doi: 10.1309/AJCP7TBN5VZUGLZU. [Internet] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado D, Castro J, Palmeira-de-Oliveira A, Martinez-de-Oliveira J, Cerca N, et al. Bacterial vaginosis biofilms: challenges to current therapies and emerging solutions. [2020 Sep 8];Front Microbiol. 2016 Jan;6:1528–1541. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01528. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, Garland SM, Morris MB, Moss LM, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazol e therapy and factors associated with recurrence. [2020 Sep 8];J Infect Dis. 2006 Jun;193(11):1478–1486. doi: 10.1086/503780. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterman TA, Tian LH, Metcalf CA, Satterwhite CL, Malotte CK, DeAugustine N, et al. High incidence of new sexually transmitted infections in the year following a sexually transmitted infection: a case for rescreening. [2020 Sep 8];Ann Intern Med. 2006 Oct;145(8):564–572. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00005. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kissinger P. Trichomonas vaginalis: a review of epidemiologic, clinical and treatment issues. [2020 Sep 8];BMC Infect Dis. 2015 Aug;15(307) doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1055-0. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kissinger P, Secor WE, Leichliter JS, Clark RA, Schmidt N, Curtin E, et al. Early repeated infections with Trichomonasvaginalis among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. [cited 2020 Sep 8];Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Apr;46(7):994–999. doi: 10.1086/529149. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blostein F, Levin-Sparenberg E, Wagner J, Foxman B. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. [2020 Sep 8];Ann Epidemiol. 2017 Sep;27(9):575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.08.010. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sobel JD. Genital candidiasis. [2020 Sep 8];Medicine. 2014 Jun;42(7):364–368. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2014.04.006. [Internet] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wendel KA, Workowski KA. Trichomoniasis: challenges to appropriate management. [2020 Sep 8];Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Apr;44(Suppl 3):S123–S129. doi: 10.1086/511425. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brocklehurst P, Gordon A, Heatley E, Milan SJ. Antibiotics for treating bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. [2020 Sep 8];Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan;1:CD000262. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd000262.pub4. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foxman B, Wen A, Srinivasan U, Goldberg D, Marrs CF, Owen J, et al. Mycoplasma, bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria BVAB3, race, and risk of preterm birth in a high-risk cohort. [2020 Sep 8];Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar;210(3):226.e1–226.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.10.003. [Internet] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reda S, Gonçalves FA, Mazepa MM, Carvalho NS. Women infected with HIV and the impact of associated sexually transmitted infections. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018 Aug;142(2):143–147. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12507. [Internet] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]