Abstract

small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) promote RNA degradation in a variety of processes and have important clinical applications. siRNAs direct cleavage of target RNAs by guiding Argonaute2 (AGO2) to its target site. Target site accessibility is critical for AGO2-target interactions, but how target site accessibility is controlled in vivo is poorly understood. Here, we use live-cell single-molecule imaging in human cells to determine rate constants of the AGO2 cleavage cycle in vivo. We find that the rate-limiting step in mRNA cleavage frequently involves unmasking of target sites by translating ribosomes. Target site masking is caused by heterogeneous intramolecular RNA-RNA interactions, which can conceal target sites for many minutes in the absence of translation. Our results uncover how dynamic changes in mRNA structure shape AGO2-target recognition, provide estimates of mRNA (un)folding rates in vivo, and provide experimental evidence for the role of mRNA structural dynamics in control of mRNA-protein interactions.

Editor summary:

Live-cell single-molecule imaging reveals that the rate-limiting step in AGO2-mediated mRNA cleavage frequently involves unmasking of target sites by translating ribosomes.

Introduction

A family of small RNAs of 20-32 nucleotides (nt), including microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and Piwi interacting RNAs (piRNAs), is an important class of molecules that regulate RNA and protein levels in cells1-5. Small RNAs guide Argonaute (AGO) proteins to target RNAs via Watson-Crick base pairing, resulting in either target cleavage or recruitment of additional effector proteins to induce other types of target repression6-11.

In vitro single-molecule imaging, as well as biochemical and structural approaches1,10,12-16 have shown that initial AGO-target interactions are established by nt 2-4 of the small RNA, and are subsequently extended to nt 2-8 (referred to as the seed region), which further stabilizes the interaction between AGO and the target site12-15. Further base pairing beyond the seed region is required for target cleavage by AGO2, the major human AGO family member with endonucleolytic cleavage activity in somatic cells8,10,17-19. However, AGO-target interaction dynamics in vivo are likely more complex. First, the cytoplasm contains many different RNA species, providing a far more complex environment for the target search process by AGO. Second, hundreds of RNA binding proteins (RBPs) exist in vivo, which may undergo kinetic competition with AGO for target site binding20-23. Third, in vivo, RNA targets are often translated by ribosomes, which may actively displace AGO proteins bound within the open reading frame (ORF)1,24,25. Finally, in vivo RNA targets are typically at least an order of magnitude longer than the RNA oligonucleotides that are frequently used as targets for in vitro studies. Long RNA targets have a far greater potential to adopt one or more secondary and tertiary structures, and RNA structures inhibit target recognition by AGO26-32. Importantly, RNA structural dynamics can take place on timescales spanning several orders of magnitude (ranging from ms to hrs) depending on the type of structural rearrangement (e.g. opening of single nucleotide interactions or large scale tertiary rearrangements)33-35. It is, however, currently unclear which types of RNA dynamics are functionally relevant for processes like AGO-target interactions.

Results

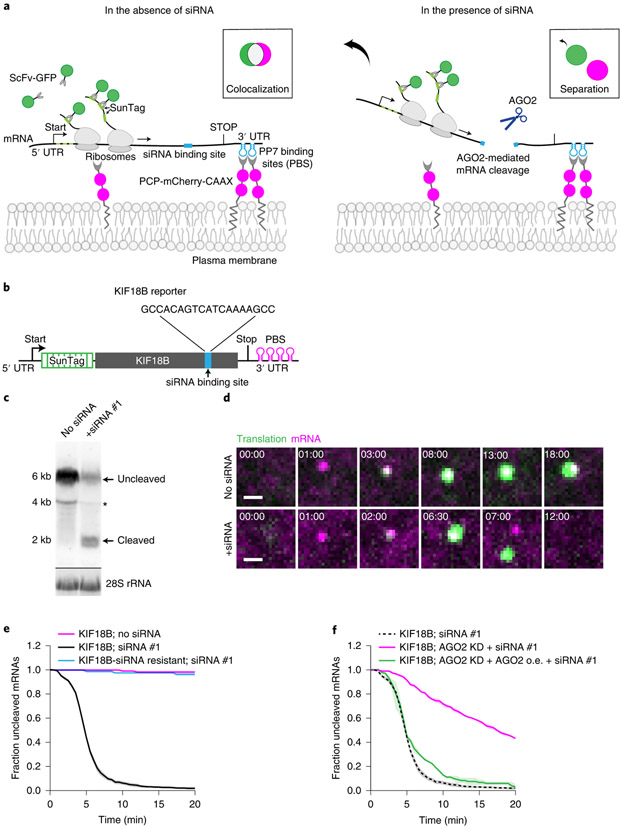

Single-molecule live-cell imaging of AGO2-dependent mRNA target silencing

To study AGO2 activity on single translated mRNA molecules in living cells, we adapted a microscopy-based live-cell imaging method that we and others recently developed to visualize translation of individual mRNA molecules (Fig. 1a, left, and Supplementary Note 1)36-40. We designed an siRNA with full complementarity to a site in the coding sequence (CDS) of a reporter mRNA (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Note 2 for siRNA sequences, and Supplementary Note 3 for plasmid design and sequences). Analysis by northern blot, qPCR, and single-molecule FISH (smFISH) revealed that siRNA transfection induced a reduction in reporter mRNA levels, and the formation of 3’ and 5’ cleavage fragments (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1a-f), indicating that the reporter mRNA was targeted for endonucleolytic cleavage. The 5’ cleavage fragment comprises most of the CDS and is thus likely associated with the majority of ribosomes translating the SunTag epitope, which recruits GFP signal (Fig. 1a, right). The 3’ mRNA cleavage fragment contains a small part of the CDS, as well as the PCP binding sites, which bind to and concentrate mCherry-labeled molecules embedded in the plasma membrane. Upon cleavage, the mCherry-labeled 3' cleavage fragment is thus expected to remain in the field-of-view (until it is degraded by an RNA exonuclease) while the GFP positive 5’ fragment is expected to diffuse out of the field-of-view (where it is likely degraded through the non-stop decay pathway) (Fig. 1a, right). Thus, we reasoned that in live-cell imaging experiments, mRNA cleavage would result in a separation of GFP and mCherry foci.

Figure 1. Observing AGO2-dependent mRNA target silencing by single-molecule live-cell imaging.

a, Schematic of the single-molecule imaging assay used to visualize AGO2-mediated mRNA silencing in the absence (left) or presence (right) of siRNA. Green and magenta spots (insets) show nascent polypeptides (translation) and mRNA, respectively, as observed by microscopy. b, Schematic of the mRNA reporter. c, Northern blot of cells expressing the reporter mRNA shown in (b) either without siRNA or transfected with KIF18B siRNA #1. (top) Upper band (uncleaved) represents full-length reporter mRNA, lower band (cleaved) represents the 3’ cleavage fragment. Asterisk indicates an additional 4 kB band that may represent a shorter isoform of the reporter mRNA. (bottom) 28S rRNA acts as a loading control. d, Representative images of mRNA molecules of the reporter shown in (b) expressed in SunTag-PP7 cells without (top) or with siRNA (bottom). Scale bar, 1 μm. Time is shown in min:sec. e-f, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing indicated reporters were transfected with 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #1, where indicated. The time from first detection of translation until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. f, Cells expressing dCas9-KRAB were infected with sgRNA targeting endogenous AGO2 (AGO2 KD), or with full length AGO2 (AGO2 o.e. (overexpression)), where indicated. Dotted lines indicate that the data is replotted from panel e for comparison. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Uncropped images for c and data for graphs in e,f are available as source data online.

Upon induction of transcription of the reporter mRNA in human U2OS cells, new mRNAs rapidly appeared in the field-of-view and initiated translation (Figure 1d, Supplementary Video 1, and Supplementary Note 1). Strikingly, in siRNA-transfected cells, GFP and mCherry foci frequently separated within minutes of translation initiation (92% of mRNAs in 10 min) (Fig. 1d, bottom, Fig. 1e, Supplementary Note 4, and Supplementary Video 2). Separation of GFP and mCherry foci was due to AGO2-dependent endonucleolytic cleavage as foci separation was largely eliminated by mutation of the siRNA binding site or depletion of AGO2 (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 1g). Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity of most (97%) GFP foci at the time of separation was greater than the intensity of a single SunTag polypeptide, indicative of endonucleolytic cleavage rather than translation termination (Extended Data Fig. 1h, Supplementary Note 4). In contrast, transcription of the reporter mRNA (Extended Data Fig. 1i) and nuclear mRNA levels (Extended Data Fig. 1d,f) were unaffected by AGO2-siRNA complex, consistent with previous studies41. Similarly, no significant effect on translation rates was observed (Extended Data Fig. 1j,k, and Supplementary Note 5). Together, these results show that endonucleolytic cleavage in the cytoplasm is the predominant mechanism of action of AGO2-siRNA complexes.

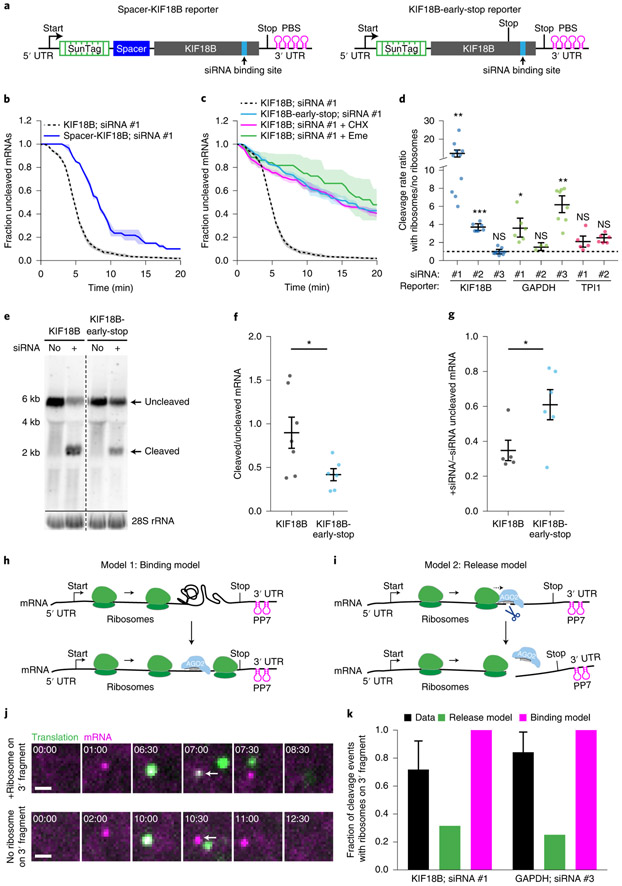

Ribosomes stimulate AGO2-dependent mRNA cleavage

Surprisingly, many mRNAs (56%) were cleaved between 4-6 minutes after the start of translation (i.e. after first appearance of GFP signal on an mRNA) (see Fig. 1e). Intriguingly, this time window represents the approximate time at which the first ribosome arrives at the AGO2 cleavage site (see also Extended Data Fig. 2a, pink bars, and Supplementary Note 5)37. Introduction of a spacer sequence between the SunTag and AGO2 binding site (Fig. 2a, left), substantially delayed cleavage relative to the start of translation (Fig. 2b), suggesting that ribosomes arriving at the AGO2 binding site stimulate AGO2-dependent mRNA cleavage. Furthermore, treatment of cells with the ribosome translocation inhibitors cycloheximide (CHX) or Emetine (Eme), or introduction of a stop codon upstream of the AGO2 binding site all strongly inhibited AGO2-dependent mRNA cleavage (Fig. 2a, right, Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2b). Together, these results show that arrival of translocating ribosomes at the s iRNA binding site stimulates mRNA cleavage by AGO2.

Figure 2. Ribosomes stimulate AGO2-dependent mRNA cleavage by promoting AGO2-target interactions.

a, Schematic of indicated reporters. b-c, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing indicated reporters were transfected with 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #1 and treated with CHX or Emetine, where indicated. The time from first detection of translation or (c) from CHX or Eme addition (+ Eme, + CHX), until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. Dotted lines indicate that the data is replotted from Fig. 1e for comparison. d, Ratio of the cleavage rates in the presence and absence of translating ribosomes (translation was inhibited by CHX addition) isshown for the indicated siRNAs and reporters (Supplementary Note 4). e, Northern blot of cells expressing the KIF18B or KIF18B-early-stop reporter, either non-transfected (no siRNA) or transfected with 10nM KIF18B siRNA #1 (+ siRNA). (top) Upper band (uncleaved) represents the full-length reporter mRNA; lower band (cleaved) represents the 3’ cleavage fragment. (bottom) 28S rRNA acts as a loading control. f, Ratio of the northern blot band intensity for bands representing cleaved and uncleaved mRNAs for the + siRNA condition. g, Ratio of the intensity of the + siRNA and − siRNA uncleaved bands. f-g, Each dot represents a single experiment and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. h-i, Schematics for h, ‘binding’ and i, ‘release’ models explaining how ribosomes could stimulate AGO2-mediated mRNA cleavage. j, Representative images of mRNA molecules in SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the KIF18B-ext reporter showing cleavage events with (top) or without (bottom) a ribosome on the 3’ cleavage fragment. Arrows indicate 3’ cleavage fragments. Time is indicated as min:sec. k, The fraction of mRNAs that contains a ribosome on the 3’ cleavage fragment is shown for the data (black bars) and for the indicated models (green and pink bars). P-values in d, f-g are based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. P-values are indicated as * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), ns = not significant. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Uncropped images for e and data for graphs in b-d,f-g,k are available as source data online.

Analysis of additional siRNAs and mRNAs (see Supplementary Note 2 and 3) revealed that other siRNAs (4/8) also showed a higher cleavage rate by AGO2 in the presence of translating ribosomes (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 2c-i, and Supplementary Note 4). Ribosome-stimulated cleavage by AGO2 was further confirmed by northern blot analysis (Fig. 2e-g and Extended Data Fig. 2j). Together, these results suggest that ribosome-stimulated cleavage by AGO2 may be a common phenomenon in living cells.

Ribosomes promote AGO2-target interactions

We considered two models explaining how a translating ribosome could stimulate AGO2-dependent mRNA cleavage. First, ribosomes could promote AGO2-mRNA target interactions (‘binding’ model; Fig. 2h). For example, ribosomes may clear the AGO2 binding site of RBPs or unfold RNA structures that mask the AGO2 binding site. Second, it is possible that ribosome collisions with AGO2 stimulate release of the 5’ and 3’ cleavage fragments from AGO2 after endonucleolytic cleavage has occurred (‘release’ model; Fig. 2i) (note that our imaging approach cannot distinguish between mRNA cleavage and fragment release). When imaging mRNA cleavage at higher time-resolution, we frequently found a ribosome on the 3’ cleavage fragment, which is consistent with a model in which the ribosome clears the AGO2 binding site (binding model), but not with the release model (Fig. 2h and 2j upper panel, and Supplementary Note 6). After normalizing the data (see Supplementary Note 6) we found that one or more ribosomes was present on the 3’ cleavage fragment in 76% and 85%, for KIF18B and GAPDH reporters, respectively (Fig. 2k, black bars, and Extended Data Fig. 2k). Using computational modeling, we found that these values were indeed most consistent with the ‘binding’ model (Fig. 2k, Extended Data Fig. 2l and Supplementary Note 6).

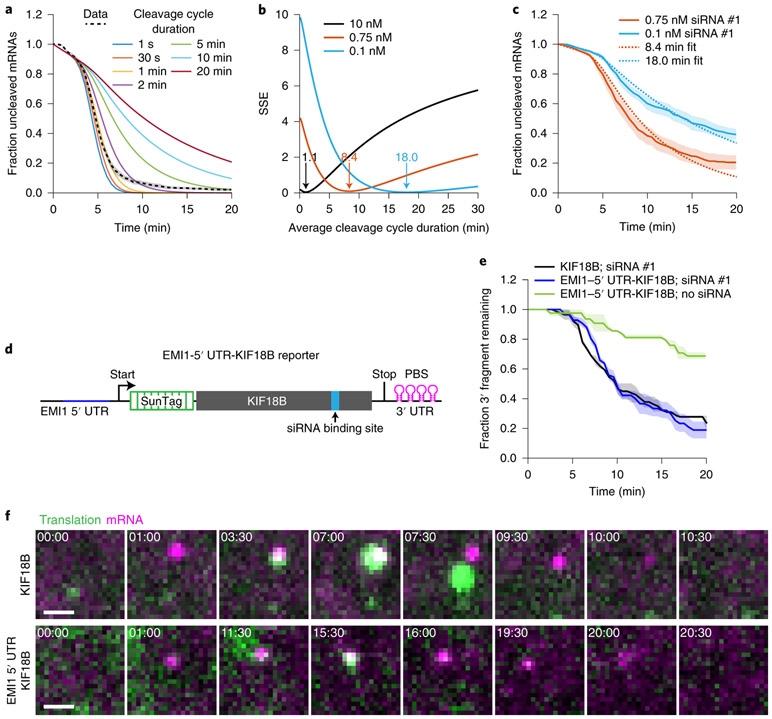

In vivo kinetics of the AGO2 cleavage cycle

While several studies have determined the kinetics of each step of the cleavage cycle of AGO2 in vitro12-16,26,42, very little is known about the cleavage kinetics in vivo. To estimate the duration of the entire cleavage cycle in vivo (from binding site availability to fragment release), we computed cleavage curves using different theoretical AGO2 cleavage cycle durations (Fig. 3a, colored lines show example curves, see Supplementary Note 7). We compared the computed cleavage curves with the experimental cleavage curve (Fig. 3a), which revealed that a cleavage cycle duration of ≤1 min best fit the data (Fig. 3a,b, black line). An in vitro cleavage assay confirmed a cleavage cycle duration of 1-2 min (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3. In vivo kinetics of the AGO2 cleavage cycle.

a, Simulated cleavage curves for indicated (theoretical) durations of the cleavage cycle (solid colored lines) are compared to the data (KIF18B + 10 nM siRNA #1; black dotted line, replotted from Fig. 1e). Time represents time since GFP appearance. b, Sum of squared error values are shown for different average cleavage cycle durations for indicated siRNA concentrations. Arrows and values indicate average cleavage cycle duration of the optimal fit. c, Dotted lines indicate the best cleavage curve fit for the indicated siRNA concentrations. c, e-f, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the KIF18B reporter or e-f, the EMI1-5’UTR-KIF18B reporter were transfected with KIF18B siRNA #1 at indicated concentrations (10 nM in e and f). c, e, The time from first detection of translation until (c) separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) or (e) mCherry disappearance (i.e. exonucleolytic decay of the 3’ cleavage fragment) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. d, Schematic of the EMI1-5’UTR-KIF18B reporter. f, Representative images of a time-lapse movie are shown. Scale bar, 1 μm. Time is shown in min:sec. Note that fluorescent intensities for the KIF18B reporter and the EMI1-5’UTR-KIF18B reporter images are scaled differently to allow visualization of the very dim GFP signal associated with translation by a single ribosome (bottom). Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in a-c,e are available as source data online.

Next, we focused on the binding step in more detail. To assess the effective AGO-siRNA concentration in cells at different transfected siRNA concentrations, we decreased the concentration of siRNA from 10 nM to 1.0 nM, 0.75 nM or 0.1 nM to slow down the binding rate and analyzed cleavage rates (Fig. 3c, solid lines). This analysis revealed a linear correlation between cleavage rate and siRNA concentration between 0.1 and 1.0 nM siRNA, but a lower than expected cleavage rate at 10 nM, possibly due to saturation of siRNA association with AGO2 (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Comparison of the cleavage curves for 0.75 nM and 0.1 nM siRNA with simulated cleavage time distributions revealed a good fit with an average cleavage cycle duration of ~8 min and ~18 min, respectively (Fig. 3b, orange and blue line, Fig. 3c, dotted lines, and Supplementary Note 7). Since the catalysis and release steps are unlikely affected by a decrease in the siRNA concentration, these results suggest that even at moderately high siRNA concentrations (i.e. at least between 0.75 nM and 10 nM), target binding is the rate-limiting step, whereas AGO2 structural rearrangements, catalysis and fragment release all occur relatively fast (<1 min).

It is possible that the estimated time for the release step described above reflects ribosome-stimulated release; our earlier results show that the first ribosome promotes AGO2-target binding by unmasking the target site (see Fig. 2k), but does not exclude the possibility that a following ribosome stimulates fragment release by colliding with AGO2 after catalysis has occurred. However, we observed a very similar cleavage cycle duration for an mRNA reporter translated by a single ribosome (Fig. 3d-f and Supplementary Note 4)37,43,44, further indicating that fragment release occurs rapidly after mRNA cleavage in vivo. Finally, these results also show that a single ribosome translating the siRNA binding site is sufficient to stimulate binding site accessibility for AGO2/siRNA complexes.

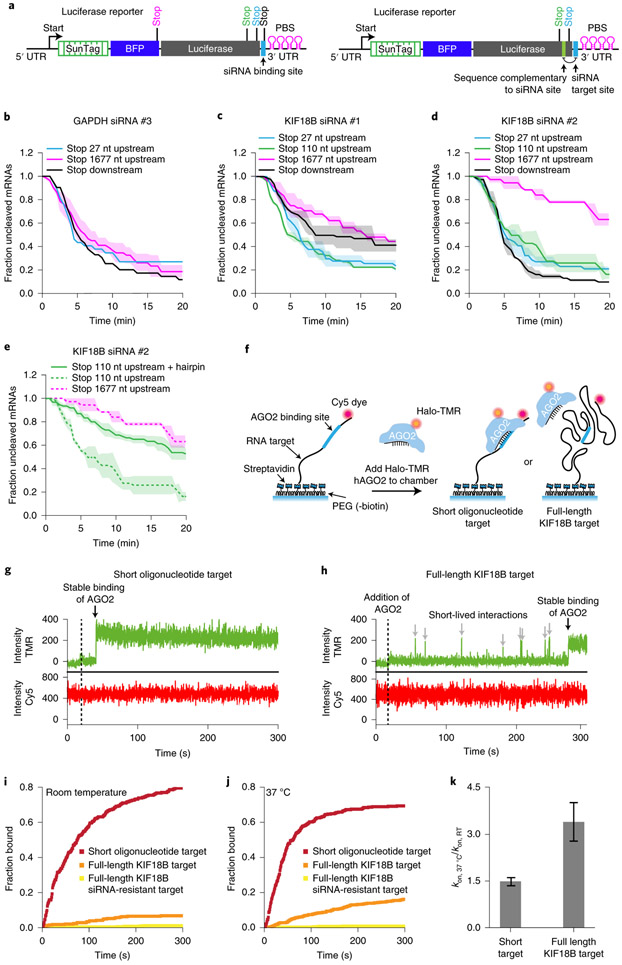

Interactions of the AGO2 target sequence with flanking mRNA sequences drive target site masking

Translating ribosomes can promote binding site accessibility either by displacing RBPs from the binding site, or by unfolding RNA structure(s) that mask the AGO2 binding site. To distinguish between these possibilities, we designed new reporters (referred to as ‘luciferase reporters’ due to the luciferase gene in the CDS) in which the siRNA binding site is positioned close to the 3’ end of the mRNA (immediately upstream of the PCP binding site array). Due to the position of the siRNA binding site, structures masking the AGO2 binding site will arise predominantly from interactions between the AGO2 binding site and upstream mRNA sequences. Stop codons were introduced either 27 nt or 110 nt upstream of the siRNA binding site (‘late stop’ reporters) (Fig. 4a, left). In these ‘late stop’ luciferase reporters ribosomes can disrupt interactions of the AGO2 binding site with upstream mRNA sequences, without displacing RBPs from the binding site (as the AOG2 binding itself is not translated). As controls, we generated reporters in which the stop codon is positioned downstream of the siRNA binding site (‘downstream stop’ reporter) for which ribosomes can remove both structures and RBPs, or reporters with a stop codon 1677 nt upstream of the binding site (‘early stop’ reporters), for which ribosomes remove neither flanking structures nor RBPs (Fig. 4a, left). For these experiments, we selected the target sites of KIF18B siRNAs #1 and #2, and GAPDH siRNA #3, as each of these target sites showed strong stimulation of cleavage by ribosomes (i.e. target site masking) in their original contexts (see Fig. 2d).

Figure 4. Masking of mRNA target sites by RNA structures inhibits AGO2-target interactions.

a, Schematic of the ‘luciferase’ reporter. Position of different stop codons and nt complementary to siRNA target site (right) are indicated. b-e, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the indicated reporters were transfected with 10 nM of the indicated siRNA. The time from first detection of translation until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. Dotted lines in (e) indicate that the data is replotted from Fig. 4d for comparison. f, Schematic of the in vitro single-molecule binding assay. g-h, Representative traces of AGO2-siRNA complex binding to (g) the short oligonucleotide target or (h) the full length KIF18B target. Green line represents Halo-TMR AGO2 (top) and red line represents Cy5 RNA signal (bottom). Grey arrows indicate short binding events by AGO2 and black arrow indicates stable binding by the AGO2-siRNA complex. i-j, The cumulative fraction of target RNAs bound by Halo-TMR AGO2 is plotted as a function of time for the indicated reporters at (i) room temperature (RT) and (j) 37°C. k, Ratio of kon at 37° C and RT for the short oligonucleotide target and the full length KIF18B target. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments). Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in b-e,i-k are available as source data online.

mRNAs containing the GAPDH siRNA #3 site showed fast cleavage even when the AGO2 binding site was positioned in the non-translated region (Fig. 4b), suggesting that the binding site is not masked in these new reporters. In contrast, for the reporters containing either the KIF18B siRNA #1 or #2 site, cleavage was substantially faster for the ‘downstream stop’ reporters compared to the ‘early stop’ reporters (Fig. 4c,d, compare black and pink lines), indicative of target site masking. Importantly, cleavage rates of the ‘late stop’ reporters were at least as fast as cleavage rates of the ‘downstream stop’ reporter (Fig. 4c,d, compare blue and green to black lines), indicating that ribosomes stimulate AGO2 mRNA binding and cleavage by unfolding mRNA secondary structure, rather than displacing RBPs from the binding site for both reporters. To further confirm the role of RNA structure in AGO2 target site masking, we placed two copies of a 7 nt sequence with complementarity to the siRNA binding site just downstream of the stop codon in the 110 nt-early-stop reporter, embedding the AGO2 binding site in a hairpin structure (‘hairpin reporter’) (Fig. 4a, right). The ‘hairpin reporter’ showed a severely reduced cleavage rate compared to its parent reporter (Fig. 4e, compare solid and dotted green lines), confirming that intramolecular RNA interactions inhibit AGO2-target binding, consistent with previous findings27. Surprisingly, for the KIF18B siRNA #1, the rate of cleavage of the ‘early stop’ reporters was even faster than that of the ‘downstream stop’ reporter (Fig. 4c, compare blue and green lines to black line). A possible explanation for this result is that ribosomes passing over the AGO2 binding site impair mRNA cleavage by displacing AGO2 from the mRNA upon collision before cleavage has occurred.

Interestingly, while cleavage by GAPDH siRNA #3 showed strong stimulation by ribosomes when the siRNA binding site was in its native context, the same binding site was no longer ribosome-stimulated in the sequence context of the luciferase reporter (Fig. 4b), suggesting that the interactions between the AGO2 binding site and flanking mRNA sequences determines the degree of binding site masking. Indeed, when AGO2 binding sites were inserted in different mRNAs and at different positions in an mRNA, the magnitude of target site masking (i.e. the ribosome-dependent cleavage stimulation) varied (Extended Data Fig. 4a-g).

To directly test the role of flanking sequences in AGO2 target site masking, we established an in vitro assay to visualize AGO2 binding to either a short RNA oligonucleotide or the full length KIF18B mRNA (Fig. 4f-h). As a control, we mutated the siRNA binding site. AGO2 binding to the oligonucleotide target occurred rapidly (t1/2 = 73 ± 8 s, mean ± SD), while binding to the full length mRNA target was much slower (t1/2 = 4.1 ± 0.7 x 103 s, mean ± SD) (Fig. 4i), indicating that RNA structures formed in the full length transcript inhibit binding of AGO2 to the target site. We did not observe many binding events to the mRNA with a mutated AGO2 target site, suggesting that AGO2 does not stably interact with other sequences in the mRNA (Fig. 4i, yellow line). Since RNA folding is strongly dependent on temperature (with higher temperature resulting in reduced RNA folding), we repeated the binding assay at 37°C instead of room temperature and found that AGO2 bound to the full length KIF18B target 3.4-fold faster at 37°C, while binding to the oligonucleotide target was only 1.5-fold faster at 37°C (Fig. 4j, k), suggesting that structural remodeling of the mRNA driven by thermal fluctuations affects AGO2 binding site availability.

Combinations of multiple weak intramolecular mRNA interactions result in potent AGO2 target site masking

To determine the nature of the structures that mask the AGO2 target sites, we performed structure prediction using mfold45. We generated a new reporter (‘mfold reporter’, based on the GAPDH reporter) that contained 19 substitutions in the mRNA sequence flanking the target site, which disrupted all the strongest predicted RNA structures involving the AGO2 binding site (see Supplementary Note 3). Surprisingly however, mRNA cleavage was still strongly stimulated by ribosomes (Fig. 5a), indicating that the AGO2 binding site remained masked by RNA structures in the ‘mfold reporter’ mRNA.

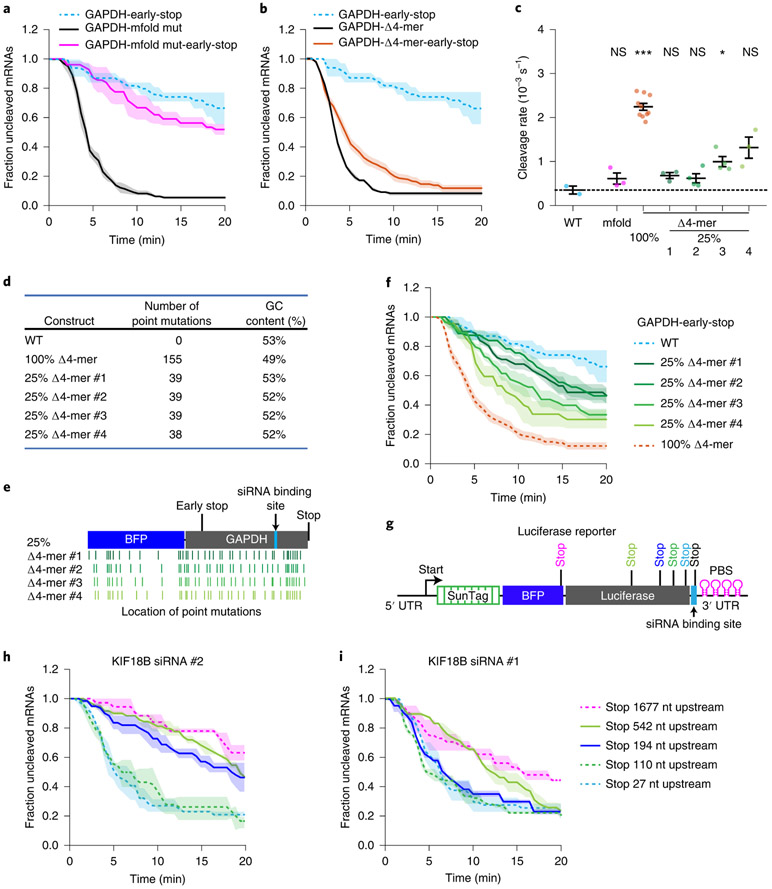

Figure 5: Multiple weak intramolecular mRNA interactions cooperatively mask AGO2-target sites.

a, b, f, h-i, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the indicated reporters were transfected with (a, b, f) 10 nM GAPDH siRNA #3 or (h-i) indicated siRNAs. The time from first detection of translation until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. Dotted lines indicate that the data is replotted from an earlier figure panel for comparison. (a, b) replotted from Extended Data Fig. 1g; (f) replotted from Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 1g; (h) replotted from Fig. 4d; (i) replotted from Fig. 4c. c, Calculated cleavage rates in the absence of ribosomes translating the siRNA target site are shown for indicated reporters treated with GAPDH siRNA #3 (Supplementary Note 4). Each dot represents a single experiment and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. P-values are based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. P-values are indicated as * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), ns = not significant. d, Characteristics of the different Δ4-mer reporters. e, Schematic overview of the location of the single nucleotide substitutions in the 25% Δ4-mer reporters. g, Schematic overview of the luciferase reporters used in (h-i) containing stop codons at variable distances from the siRNA binding site. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in a-c,f,h-i are available as source data online.

Possibly, AGO2 binding site masking arises from numerous weak interactions between the AGO2 binding site and short complementary nucleotide sequences in the target mRNA. To test this hypothesis, we mutated 4-mer sequences in the GAPDH mRNA reporter that showed complementarity to the AGO2 target sequence (i.e. disrupting intramolecular RNA-RNA interactions), referred to as the ‘Δ4-mer’ reporter (see Supplementary Note 3). Removal of 4-mers substantially increased the cleavage rate in the absence of ribosomes translating the AGO2 binding site (~6 fold) (Fig. 5b,c, compare blue and orange dots), indicating that AGO2 binding site masking was largely disrupted in the Δ4-mer mRNA. Removal of complementary 4-mers for KIF18B siRNA #1 in the KIF18B reporter also substantially reduced ribosome-dependent stimulation of mRNA cleavage, although residual cleavage stimulation could still be observed (Extended Data Fig. 5a), possibly due to other short sequences with complementarity (e.g. 3-mers or 6 or 7-mers with single mismatches). Together, these results suggest that multiple nucleotide sequences, each with weak affinity for the AGO2 binding site, together can drive strong target site masking.

If many different sequences within the mRNA contribute to AGO2 target site masking, it is likely that a high degree of structural heterogeneity can exist. To test this, we generated four new ‘Δ4-mer’ reporters; in each of these reporters a non-overlapping set of 25% of the single nucleotide substitutions were introduced that disrupt the complementary 4-mers (Fig. 5d,e, and Supplementary Note 3). All four ‘25% Δ4-mer’ reporters showed a partial effect on the cleavage rate (Fig. 5f, c, compare blue and green dots, and Extended Data Fig. 5b-e), further suggesting that multiple low affinity interactions cooperatively cause AGO2 target site masking, and that structural heterogeneity underlies robust target site masking.

Finally, we varied the distance between the stop codon and the AGO2 target site to map the distances over which flanking sequences can act to mask the AGO2 target site. This revealed that structures spanning several hundred nucleotides can contribute to AGO2 target site masking (Fig. 5g-i and Extended Data Fig. 5f), consistent with other studies showing that base-pairing interactions can occur over large distances46,47.

mRNA folding kinetics and the translation rate control AGO-target interactions

While several methods are available to capture ‘snapshots’ of RNA structure46,48-56, very little is known about the structural dynamics of mRNAs in vivo. Such dynamics of mRNA (un-)folding are likely important, as structural unmasking of binding sites is a key driver of AGO2-target interactions.

Inhibiting ribosome translocation by addition of CHX results in a decreased cleavage rate (see Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2c-i), suggesting that mRNAs refold after ribosome-dependent unfolding. We reasoned that upon inhibition of ribosome translocation, the cleavage rate will decrease over time as re-folding of the target site occurs. Indeed, for 3 out of 4 reporter-siRNA combinations, we observed a fast initial cleavage rate after CHX addition, followed by a slower cleavage rate at later time points (Fig. 6a and Extended Data Fig. 6a-c, red lines, see Supplementary Note 4 for methods). Fitting these cleavage curves with a double exponential decay distribution and correcting for the delay in ribosome stalling upon addition of CHX (Extended Data Fig. 6d, Supplementary Note 4 and 5) revealed that open AGO2 target sites are masked within ~30-90 s of ribosome-dependent unfolding (Fig. 6a, Extended Data Fig. 6a,b, dotted lines, and Extended Data Fig. 6e). For the fourth reporter-siRNA condition (GAPDH siRNA #3) the cleavage rate was faster than expected (compare Extended Data Fig. 6c, red line, and Extended Data Fig. 2g, pink line), suggesting that the target site remains in a (partially) unmasked state in the presence of stalled ribosomes for this reporter. Possibly, stalled ribosomes near the target site inhibit mRNA re-folding for this region of the mRNA.

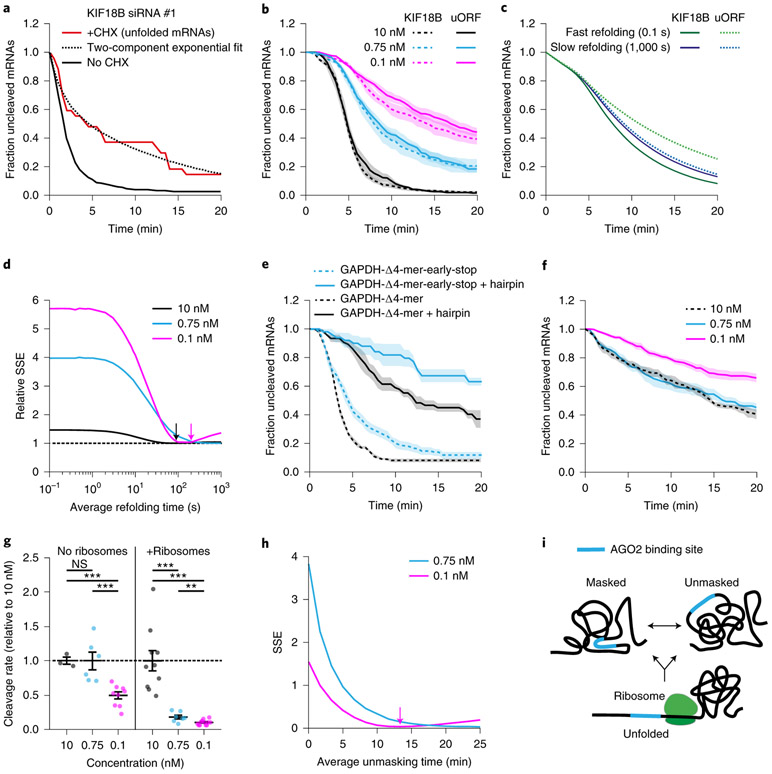

Figure 6: Kinetics of mRNA folding shape AGO2-mRNA interactions.

a, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the KIF18B reporter were transfected with 10 nM siRNA KIF18B #1 and treated with CHX, where indicated. Only mRNAs for which translation initiated between 3.5-6.5 min before CHX addition were included (Supplementary Note 4). The time since CHX addition is shown for the ‘+CHX’ cleavage curve. Dotted line represents optimal fit with a two-component exponential decay distribution. The no CHX cleavage curve is re-normalized and plotted from 3.5 min after the start of translation. b,e-f, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing indicated reporters were transfected with (b,f) KIF18B siRNA #1 as indicated or (e) 10nM GAPDH siRNA 3 and treated (b, e) without or (f) with CHX. The time from (b, e) first detection of translation or (f) CHX addition until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. Dotted lines indicate that the data is replotted from an earlier figure panel for comparison. (b) replotted from Fig. 1e and 3c; (e) replotted from Fig. 4b; (f) replotted from Fig. 2c. c, Simulated cleavage curves for the KIF18B reporter and uORF reporter simulated with a fast or slow mRNA re-folding time. Note that the fast and slow re-folding curves use different AGO2 cleavage rates to generate an optimal fit to the data (Supplementary Note 8). d, Goodness-of-fit score (relative SSE) at different simulated mRNA re-folding times for the data shown in (b) at indicated siRNA concentrations (Supplementary Note 8). Arrows indicate re-folding time of best fit. g, Calculated cleavage rates for different siRNA concentrations (relative to 10 nM siRNA) for the data shown in (b, f). Each dot represents a single experiment and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. P-values are based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. P-values are indicated as * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), ns = not significant. h, Goodness-of-fit score (SSE) at different simulated unmasking times (Supplementary Note 8). Arrow indicates unmasking time of the best fit. i, Schematic model of AGO2 target site masking and unmasking and the role of ribosomes in target site unfolding. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in a-h are available as source data online.

To confirm our measurements of mRNA re-folding kinetics after ribosome-induced unfolding, we examined the relationship between the translation initiation rate, the mRNA re-folding rate, and the mRNA cleavage rate. We reasoned that the cleavage rate depends on the fraction of time that the target site is unmasked. If mRNA re-folding is fast, the target site will be mostly masked and increasing the frequency of ribosome-induced mRNA unfolding (dependent on the translation initiation rate) will increase the cleavage rate. In contrast, if the mRNA re-folds slowly, the target site will still be unmasked when the next ribosome arrives, and increasing the translation initiation rate won’t increase the cleavage rate. Thus, by measuring the cleavage rate at different translation initiation rates the mRNA folding rate can be assessed.

We introduced an upstream open reading frame (uORF) into the KIF18B reporter (‘uORF-KIF18B’ reporter), which reduced the translation initiation rate by 3.3 fold (Extended Data Fig. 6f, and Supplementary Note 5). Measuring mRNA cleavage rates for both the KIF18B and ‘uORF-KIF18B’ reporters at three different siRNA concentrations (10 nM, 0.75 nM, and 0.1 nM) revealed very similar cleavage rates for both reporters at each concentration of siRNA (Fig. 6b), suggestive of a relatively slow mRNA refolding rate. To quantitatively assess the mRNA re-folding rate, we developed a computational framework to simulate mRNA cleavage curves at different (theoretical) AGO2 cleavage rates, mRNA folding rates and translation initiation rates (see Supplementary Note 8). As expected, we found that at fast re-folding rates the simulations predict a relatively large difference between the cleavage rate of the KIF18B and uORF-KIF18B reporter, while a small difference in cleavage rate is predicted at slow mRNA re-folding rates (Fig. 6c). To compare the simulated and experimental cleavage curves at different theoretical mRNA folding rates, we computed a goodness-of-fit score (sum of squared errors (SSE)) (Fig. 6d, and Supplementary Note 8). For both the 10 nM and 0.1 nM, the optimal fit was achieved when simulating an mRNA re-folding time of ~30-180 s, while a somewhat slower re-folding time (>180 s; a precise value could not be given due to the absence of a local minimum) was found for the 0.75 nM condition (Fig. 6d). Overall, these results are in reasonably good agreement with the measurements of mRNA re-folding upon CHX treatment (30-90 s).

Our results suggest that the (complex) mRNA structures that stably mask the AGO2 target site re-fold slowly after ribosome-dependent unfolding, allowing the target site to be unmasked continuously even when a ribosome passes the target site only 1-2 times per minute. In contrast for, a simple RNA structure, such as a hairpin, re-folding is expected to occur rapidly after ribosome-mediated unfolding, limiting the stimulatory effect of ribosomes on AGO2-target interactions. To test this, we introduced the siRNA target site into a hairpin structure (see Supplementary Note 3). For this experiment, we selected different reporters in which the target site is unmasked in the absence of ribosomes (e.g. GAPDH Δ4-mer reporter, see Fig. 5b orange line, or the luciferase reporter, see Fig. 4d green line). As expected, introduction of the hairpin structure strongly reduced the cleavage rate in the absence of ribosomes (Fig. 6e and Extended Data Fig. 6g, compare blue lines). Interestingly, cleavage rates in the presence of translating ribosomes were also reduced in these hairpin reporters (Fig. 6e and Extended Data Fig. 6g, compare black lines), indicating that ribosomes indeed unmask target sites less efficiently when the target site is present in a fast-folding RNA structure (Extended Data Fig. 6h). These results suggest that ribosomes predominantly stimulate AGO2 target binding by unfolding slowly re-folding structures, which likely represent more complex secondary or tertiary structures.

Slow structural dynamics limit AGO2 binding in the 3'UTR

When positioned in non-translated regions of the mRNA (i.e. 3’ UTR), AGO2 binding sites are not unfolded by ribosomes, yet cleavage still occurs (albeit at a slower rate). Therefore, structural unmasking of the target site must occur through alternative mechanisms. One possibility is that mRNAs switch between different structural conformations over time and that AGO2 target sites are only masked in a subset of all possible structural configurations. If structural rearrangements occur on a timescale that is much faster than AGO2-target binding (~1-18 min for 0.1-10 nM siRNA, see Fig. 3b), AGO2-target binding will be rate-limiting for mRNA cleavage in the 3’ UTR, and the mRNA cleavage rate will depend primarily on the AGO2-siRNA concentration. In contrast, if structural rearrangements occur at rates similar to or slower than AGO2-target binding, structural unmasking becomes an (additional) rate-limiting step, and the mRNA cleavage rate will become less sensitive to the siRNA concentration. Interestingly, the cleavage rate in the absence of ribosomes showed a weak dependency on siRNA concentration (Fig. 6f,g and Extended Data Fig. 6i), demonstrating that, in the absence of translating ribosomes, structural unmasking of target sites, rather than AGO2-siRNA concentration in the cell is the main rate-limiting step for mRNA cleavage.

To quantitatively investigate the dynamics of ribosome-independent structural rearrangements, we simulated the effect of decreasing the siRNA concentration on the mRNA cleavage rate in the absence of ribosomes (see Supplementary Note 8). For slow (simulated) structural dynamics, we found that the simulated mRNA cleavage rate is less sensitive to siRNA concentration (0.1-10 nM) than for fast dynamics (Extended Data Fig. 6j, compare the solid and dotted pink lines to the black line), consistent with the experimental data (Fig. 6f, compare the pink line to the black line). To extract quantitative information about the ribosome-independent unmasking time of our reporter mRNA through simulations, we compared the experimental cleavage curves at different siRNA concentrations (0.75 nM and 0.1 nM) to multiple simulated cleavage curves (each with different unmasking times) using a goodness-of-fit score (SSE). Further analysis revealed that the best fits were obtained with unmasking times of >10 min (Fig. 6h), indicating that target site unmasking becomes a rate-limiting step in mRNA cleavage, especially at higher concentrations of siRNA (between 0.75 nM and 10 nM). Furthermore, these simulations indicate that target site unmasking in the 3’ UTR (i.e. in the absence of translating ribosomes) is much slower (>10 min) than the unmasking rate in the CDS (where target sites are unfolded every ~25 s by a translating ribosome for our reporters), highlighting the importance of ribosome-mediated unmasking of target sites for efficient AGO-target interactions.

Discussion

In this study, we use a live-cell imaging approach to visualize translation and AGO2-mediated cleavage of individual mRNA molecules. This work provides in vivo measurements of AGO2 cleavage kinetics and reveals how mRNA structural dynamics and heterogeneity shape AGO-target interactions.

Paradoxical roles of ribosomes in controlling AGO2-mRNA target interactions

Recent reports showed that ribosomes reduce the overall degree of structure in the CDS of the transcriptome27,54,57,58 and that AGO target sites are less efficiently recognized if they are embedded within a strong structure26,27,29-31. Here, we show that ribosome-dependent unfolding of mRNA structures stimulates AGO-target interactions, thereby providing a direct, causal link between mRNA translation and AGO2-target binding. Interestingly, not all siRNA-target combinations were stimulated to the same extent by ribosomes (see Fig. 2d), indicating that some siRNA target sites are always accessible, or, alternatively, are masked by mRNA structures that re-fold rapidly after ribosome-dependent unfolding.

The observation that siRNA-mediated mRNA cleavage is more efficient in an actively translated region appears to contrast previous reports that miRNAs repress their target more efficiently when bound to the 3’ UTR24,25. It is possible that ribosomes also inhibit AGO-target interactions, for example by displacing AGO from the mRNA through physical collisions24,59. Thus, ribosomes may have two opposing activities that affect AGO-target interactions. The net effect of ribosomes on AGO-dependent target silencing may depend on a number of different factors, including the degree of target masking, the translation initiation rate and the time required for AGO-siRNA complexes to repress their target mRNA upon binding. Interestingly, previous analysis revealed that miRNA target sites positioned immediately downstream of the stop codon are highly active24. Consistent with this, we find that AGO binds very efficiently to target sites positioned immediately downstream of the stop codon, because ribosomes translating upstream mRNA sequences can stimulate unmasking of target sites immediately downstream of the stop codon (see Fig. 4c,d). Therefore, binding sites immediately downstream of the stop codon may be most potent, as they benefit from the stimulatory activity of ribosomes, while being protected from the inhibitory effect of ribosome-AGO collisions. A paradoxical role of ribosomes in both stimulating and inhibiting RBP-mRNA interactions may not be limited to AGO family proteins, but may broadly shape the interactions of RBPs with their target RNAs.

mRNA structural dynamics and heterogeneity

For AGO target sites masked by RNA structure, mutation of all or subsets of short complementary 4-mer sequences in the target mRNA reduced target site masking (see Fig. 5f), indicating that multiple (or many) sequences in the target mRNA can contribute to target site masking and that different structural configurations exist that can mask the AGO2 target site. In addition, mRNA molecules may also form intermolecular RNA-RNA interactions, potentially further inhibiting AGO2-target interactions. Finally, RBPs may also inhibit AGO2 binding at specific target sites, although our results suggest that inhibition through structural masking is a more common mechanism (see Fig. 4c-d).

Individual 4-mer base-pair interactions generally have rapid binding and unbinding kinetics. Surprisingly though, our data suggest that target sites can remain masked for >10 min in the absence of ribosomes (see Fig. 6h). So how can we reconcile these two apparently contradictory findings? One speculative model is that mRNAs form stable 3-dimensional structures in which multiple sequences with weak affinity for the AGO2 target site are positioned in close proximity to the target site, resulting in frequent interactions and robust target site masking (Fig. 6i). In this model, the key activity of ribosomes would be to unfold the stable 3-dimensional structure that facilitates target site masking, rather than directly disrupting target site interactions with complementary sequences. In the absence of translating ribosomes such structures could persist for long periods of time (>10 min), explaining the very slow cleavage kinetics for some reporters in which the AGO2 binding is located in the 3’ UTR (e.g. see Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 2g). Possibly, such 3-dimentional structures stochastically rearrange over time through thermal fluctuations of the mRNA, resulting in AGO2 target site unmasking (without complete unfolding of the mRNA), or structures are unfolded or refolded sporadically by cellular helicases such as EIF4A60 to allow target cleavage. Together, these results provide a high temporal resolution analysis of the structural dynamics of an mRNA molecule in vivo and a framework for understanding the role of mRNA structural dynamics in shaping RBP-mRNA interactions.

Online Methods

Cell culture

Insect Sf9 cells (Expression Systems (Davis, CA), 94-001S) were grown in Insect XPRESS medium (Lonza). Human U2OS cells (ATCC, HTB-96) and HEK293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216) were grown in DMEM (4.5g/L glucose, Gibco) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco). Cells were grown at 37°C and with 5% CO2. Where indicated, Cycloheximide (CHX) (ThermoFisher) was used at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml, and Emetine (Eme) (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. All human cell lines were tested for mycoplasma and found mycoplasma free.

Live-cell imaging experiments were performed using U2OS cells, stably expressing TetR, scFv-sfGFP and PCP-mCherry-CAAX (referred to as SunTag-PP7 cells)37 as well as the reporter of interest. The smFISH imaging experiments were performed in a monoclonal cell line, stably expressing TetR, scFv-sfGFP, PCP-Halo-CAAX and the 24xGCN4-KIF18B-24xPP7 reporter. Northern blot experiments were performed using two monoclonal cell lines, both expressing TetR, scFv-sfGFP, PCP-Halo-CAAX and in addition either the 24xGCN4-KIF18B-24xPP7 reporter or the 24xGCN4-KIF18B-early-stop-PP7 reporter.

Plasmid transfections for stable integration

Plasmid design and sequences can be found in Supplementary Note 3. Cells were plated one day prior to transfection in a 6 cm dish (Greiner Bio-one). A transfection mix, containing 100 μl OptiMEM (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 μl FUGENE 6 (Promega), and ~1 μg of DNA, was added to the cells in a total volume of 1 ml cell culture medium per dish. Selection for stable integration was initiated 24h after transfection, using 0.4 mg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen), and continued for at least 10 days. To generate monoclonal cell lines, single cells from the polyclonal cell line were sorted into 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-one) by FACS, and grown for 14 days. Individual clones were inspected by microscopy and clones in which a high percentage of cells expressed the transgene were selected for further use. For generating stable monoclonal cell lines expressing reporter mRNA, clones were additionally screened for the number of mRNAs expressed per cell. Clones expressing ~10-50 mRNAs per cell were selected.

siRNA transfections

The complete list and sequence of all siRNAs used in this study is provided in Supplementary Note 2. siRNAs were designed using the siDESIGN center (horizon) and ordered from Dharmacon, except KI F18B siRNA #1 (AM16708, 251223; ThermoFisher) and GAPDH siRNA #1 (4390849, ThermoFisher). siRNAs were reverse-transfected at a final concentration of 10 nM (unless stated otherwise) using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. KIF18B siRNA #3 was transfected at a final concentration of 50 nM, as it showed weak target repression at 10 nM. For all microscopy experiments, cells were seeded at a confluency of ~40-50% in 96-well glass-bottom imaging plates (Matriplate, Brooks) in a final volume of 200 μl and imaged 16-24 hr after transfection. For northern blot experiments, cells were seeded at a confluency of ~40-50% in a 6 cm plate (Greiner Bio-one) in a final volume of 3 ml and harvested 16-24 hr after transfection. For qPCR experiments, cells were seeded in a 24-well plate (Greiner Bio-one) and harvested 16-24 hr after transfection.

Lentivirus production and infection

For lentivirus production, HEK293T cells were plated in a 6-well plate (Greiner Bio-one) at 30% confluency, and transfected 24 hr after plating with a mixture of 50 μl OptiMEM (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 μl Polyethylenimine (PEI) (Polysciences Inc) (1mg/ml), 0.4 μg pMD2.g, 0.6 μg psPAX2, and 1 μg of lentiviral vector. The medium was replaced with 2 ml fresh culture medium 24 hr after transfection, and 72 hr after transfection, viral supernatant was collected. For lentiviral infections, cells were seeded in a 6-well plate (Greiner Bio-one) at 70% confluency. Viral supernatant was added to the cells along with Polybrene (10 μg/ml) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc) and the cells were spun at 2000 rpm for 90 min at 37°C (spin infection). After the spin infection, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium, and cells were incubated for at least 48 hr before further analysis.

CRISPRi-mediated knockdown of endogenous AGO2

To knockdown endogenous AGO2 we made use of CRISPRi, since we reasoned that siRNA-mediated approaches would not be very efficient as they rely on the presence of AGO2. For CRISPRi-mediated knockdown of AGO2 we expressed dCAS9-BFP-KRAB in cells stably expressing TetR, scFv-sfGFP, PCP-Halo-CAAX and 24xGCN4-KIF18B-24xPP7. The 30% highest BFP expressing cells were isolated by FACS sorting for further use. A sgRNA targeting AGO2 (sequence: GCGCGTCGGGTAAACCTGTT) was expressed in cells together with BFP through lentiviral transduction. The BFP signal associated with the sgRNA was much higher than the BFP associated with dCAS9-BFP-KRAB, and thus sgRNA positive cells could be identified in dCAS9-BFP-KRAB-expressing cells. qPCR and imaging were performed 4 to 5 days after infection with the sgRNA. In experiments where cleavage was measured after AGO2-knockdown in combination with expression of an exogenous AGO2 rescue construct (insensitive to the sgRNAs targeting endogenous AGO2), cells were infected with an AGO2 expression construct 10 to 11 days before imaging. As AGO2 rescue construct, we used pLJM1-FH-AGO2-WT, which was a gift from Joshua Mendell (Addgene plasmid #91978; http://n2t.net/addgene:91978)61. Cells expressing exogenous AGO2 were selected with puromycin (2 μg/ml) (ThermoFisher). Infection with exogenous AGO2 was followed by a second infection 4 to 5 days before imaging with the sgRNA targeting AGO2 to knockdown endogenous AGO2.

smFISH

Single-molecule Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (smFISH) was performed as described previously5,62,63. Five oligonucleotide probes against the PP7-array and 48 probes against the SunTag-array were designed, using the website www.biosearchtech.com (the complete list and sequence of smFISH probes used in this study is provided in Supplementary Note 2). Probes were synthesized with a 3’ amine modification. Probes were then coupled to either a Cy5 or an Alexa 594 fluorescent dye (Cy5 succinimidyl ester (GE Healthcare) or Alexa Fluor 594 Fluorcarboxylic acid succinimidyl ester (Molecular probes/Invitrogen), respectively) as described previously63, and HPLC purified (ELLA Biotech GmbH). Purified probes were dissolved in 50 μl TE and used at a final dilution of 1:2000. For hybridization, cells were plated in a 96-wells glass bottom dish (Matriplate, Brooks) 16-24 hr before fixation. Doxycycline (1 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added 40 to 90 min before fixation (as indicated). Cells were fixed in PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Science) for 15 minutes at Room Temperature (RT), washed twice with PBS and incubated for 30 min in 100% ethanol at 4°C. After fixation, cells were washed twice in hybridization buffer with 10% formamide (ThermoFisher) at RT, followed by overnight incubation with the probes in hybridization buffer at 37°C. Following overnight incubation, samples were washed 3x for 1 hour in wash buffer at 37°C. DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the final wash step in order to stain the nuclei. Shortly before imaging, samples were placed in anti-bleach buffer62,63 to reduce fluorescence bleaching.

Expression and purification of TMR-HaloTag-AGO2-siRNA

His6-Flag-TEV-Halo-tagged human AGO2 protein was expressed in Sf9 cells using a baculovirus system (Invitrogen). 750 ml of Sf9 cells at 1.7 x 106 cells/ml were infected for 60 hours at 27°C. Infected cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 30 ml of Lysis Buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mM TCEP). Resuspended cells were lysed by passing twice through an M-110P lab homogenizer (Microfluidics). The resulting total cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation (30,000 x g for 25 min) and the soluble fraction was applied to 1.5 ml (packed) Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) and incubated at 4°C for 1.5 h in 50 ml conical tubes. Resin was pelleted by brief centrifugation and the supernatant solution was discarded. The resin was washed with 50 ml ice cold Nickel Wash Buffer (300 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP, 50 mM Tris, pH 8). Centrifugation and wash steps were repeated a total of three times. Co-purifying cellular RNAs were degraded by incubating with 100 units of micrococcal nuclease (Clontech) on-resin in ~15 ml of Nickel Wash Buffer supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 at room temperature for 45 minutes. The nuclease-treated resin was washed three times again with Nickel Wash Buffer and then eluted in four column volumes of Nickel Elution Buffer (300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP, 50 mM Tris, pH 8). Eluted AGO2 was incubated with a synthetic siRNA and 150 μg of TEV protease during an overnight dialysis against 1–2 liters of Dialysis Buffer (300 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 50 mM Tris, pH 8) at 4°C. The sequence of the siRNA is provided in Supplementary Note 2. Please note that the first nucleotide is a U instead of a G (as in the original KIF18B siRNA #1 sequence) to improve siRNA loading in AGO2, which does not affect AGO2-target binding64. AGO2 molecules loaded with the siRNA were isolated using an immobilized capture oligonucleotide with complementarity to the siRNA, and then eluted by adding competitor DNA with more extensive complementarity to the capture oligonucleotide via the Arpon method65. Sequences of the capture oligonucleotide and competitor DNA are provided in Supplementary Note 2. Loaded AGO2 proteins were further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex Increase 10/300 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in 1 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8, 0.5 mM TCEP. Purified Halo-AGO2-siRNA complex was incubated with Halo-TMR ligand (Promega) and dialyzed against 2 L of 1xPBS (137 mM NaCl, KCl 2.7 mM, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4), concentrated to ~2 mg/ml, aliquoted, flash frozen with liquid N2, and stored at −80°C.

In vitro target RNA synthesis and purification

A short RNA oligonucleotide (sequence provided in Supplementary Note 2) was ordered from IBA Lifesciences, labeled with a Cy5 dye (Sigma-Aldrich), as described previously66, and purified using ethanol precipitation. The labeled oligonucleotide was subsequently ligated to a U30-mer with biotin using T4 RNA ligase II (NEB) and a DNA splint (sequence provided in Supplementary Note 2).

Full length mRNA targets (KIF18B sequence or KIF18B sequence with a mutated siRNA target site) were in vitro transcribed using the HiScribe™ T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB), and purified using phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The complete sequence of the full length mRNA targets is provided in Supplementary Note 2. The full length mRNA targets were ligated to a 22 nt Cy5 labeled and biotinylated RNA oligonucleotide using a 40 nt DNA strand as a splint. The sequences of the oligonucleotide and DNA splint are provided in Supplementary Note 2. After ligation with T4 RNA ligase II (NEB), the ligated constructs were purified from an agarose gel using a Zymo Gel RNA recovery kit (Baseclear).

In vitro cleavage assay

Slicing reactions were carried out with loaded AGO2 proteins. Briefly, 10 nM of loaded AGO2 was added to 1 nM Cy5 labeled siRNA5 target in cleavage buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.15 M Sodium Chloride, 2 mM Magnesium Chloride and 0.5 mM TCEP) at 37°C in a total reaction volume of 100 μl. At each time point, 10 μl was removed and added to 10 μl loading buffer (99.5% formamide and 10 mM EDTA) to quench the reaction. Finally, samples were resolved on a 12.5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized with an Amersham Typhoon Imaging System.

In vitro binding assay

Quartz slides were prepared as described previously67. Briefly, quartz slides and coverslips were treated with KOH after which slides were treated with piranha followed with (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) (Sigma-Aldrich). Slides were subsequently PEGylated with mPEG-SVA (MW 5.000) (Laysan) under a humid atmosphere overnight. Before experiments, an additional round of PEGylation took place with (MS)PEG-4 (ThermoFisher). Quartz slides and coverslips were assembled with double-sided scotch tape after which the chambers were sealed with epoxy glue. Next, slides were incubated with T50 and 1% Tween-20 for > 10 min to further passivate the chambers68. Chambers were subsequently rinsed with T50 and streptavidin (0.1 mg/ml) (ThermoFisher) was introduced inside the chamber for 1 min and rinsed out by T50. The RNA sample was then introduced inside the chamber at a concentration of 100 pM. After 1 minute incubation, unbound RNAs were flushed out with T50. Tubing was attached to the outlet of the microfluidic chambers through epoxy glue and an injection needle was attached to the other side of the tubing. Imaging buffer (150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 1 mM Trolox, 0.8% glucose, 0.1 mg/ml glucose oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 17 μg/ml catalase (ThermoFisher)) was then introduced inside the chamber.

A short movie was taken with the 637 nm laser as a reference for the position of the RNAs of interest (referred to as reference movie), since the RNA molecules are labeled with Cy5. Subsequently, both 532 nm and 637 nm lasers were turned on, and movies were taken for 3500 frames at an exposure time of 0.1 s (referred to as measurement movies). After 200 frames, 1 nM Halo-TMR AGO2 complexes together with imaging buffer were introduced in the microfluidic chamber.

Microscopy

In vitro imaging experiments were performed on a custom built inverted microscope (IX73, Olympus) using prism-based total internal reflection. The Halo-TMR was excited with a 532nm diode laser (Compass 215M/50mW, Coherent), and Cy5 was excited with a 637 nm diode laser (OBIS 637 nm LX 140 mW). A 60x water immersion objective (UPLSAPO60XW, Olympus) was used for imaging. A 532 nm notch filter (NF03-532E-25, Semrock) and a 633 nm notch filter (NF03-633E-25, Semrock) were used to block the scattered light. A dichroic mirror (635 dcxr, Chroma) separates the fluorescence signal into separate channels, and the light is projected onto an EM-CCD camera (iXon Ultra, DU-897U-CS0-#BV, Andor Technology). The in vitro experiments were either performed at RT (20°C) or at 37°C through the use of a custom built heating elements and custom written Labview code. All in vivo imaging experiments were performed using a Nikon TI inverted microscope with perfect focus system equipped with a Yokagawa CSU-X1 spinning disc, a 100x 1.49 NA objective and an iXon Ultra 897 EM-CCD camera (Andor) using Micro-Manager software69 or NIS elements software (Nikon). All live-cell imaging experiments were performed at 37°C, while smFISH experiments were imaged at RT.

For the live-cell imaging of mRNA cleavage experiments, cell culture medium was replaced with prewarmed CO2-independent Leibovitz’s-15 medium (Gibco) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco) 15 to 30 minutes before imaging. Transcription of the reporters was induced by addition of doxycycline (1 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) to the cell culture medium. During the experiments, cells were maintained at a constant temperature of 37°C. Cells were selected for imaging based on the levels of mature protein (an indication of reporter expression) and a small number of mRNAs at the start of imaging70. For CRISPRi experiments, cells were additionally selected based on the presence of BFP. Camera exposure times of 500 ms were used for both GFP (488 laser) and mCherry (561 laser), and images were acquired every 30 s for 45 minutes, unless stated otherwise. Since mRNAs are tethered to the plasma membrane, we focused the objective slightly above the plasma membrane to focus on both mRNAs and translation sites, and single Z-plane images were acquired. For the smFISH experiments, images for all 3 colors (DAPI, Cy5 and Alexa 594) were acquired with a camera exposure time of 50 ms. Z-stacks were acquired for all 3 colors with an inter-slice distance of 0.5 μm each.

Northern blot

Northern blots were performed using Northern Max-Gly kit from ThermoFisher according to the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. In short, cells stably expressing the TetR, scFv-sfGFP, PCP-Halo-CAAX, and 24xGCN4-KIF18B-24xPP7 or 24xGCN4-KIF18B-early-stop-24xPP7 were incubated for 90 min with doxycycline (1 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) to induce expression of the mRNA reporter and RNA was extracted using TRIsure (Bioline). RNA mixed 1:1 with Glyoxal Load Dye was incubated for 30 min at 50°C to denature RNA before loading 10 μg of RNA onto a 0.8% agarose gel. After running the gel, rRNA (18S and 28S) bands were visualized using UV and signal intensities were quantified to ensure that RNA samples were loaded equally and RNA was intact. RNA transfer from the agarose gel to a positively charged nylon membrane was performed for 2 hours at RT, followed by RNA crosslinking to the membrane using UV light (120mJ/cm2 at 254 nm) for 1 min. After prehybridization at 68°C for 1 hour, the membrane was incubated with a DIG-labeled RNA probe targeting the BGH sequence present in the 3’ UTR of the mRNA reporter (the complete sequence of the probe is provided in Supplementary Note 2), and hybridization was performed overnight at 68°C. The membrane was washed 3x, and incubated with the anti-DIG antibody-AP (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 to 40 hours at 4°C. The membrane was washed 9x (6x in PBS-T and 3x in AP buffer) and incubated with a few drops of CDP-star for 5 minutes at RT. The film was exposed and developed for 2 to 10 minutes, using an Amersham Imager 600 (GE).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

The complete list and sequence of primers for RT-PCR used in this study is provided in Supplementary Note 2. To determine the siRNA knockdown efficiency of endogenous KIF18B by qPCR, siRNA treated cells were harvested 24 hr after transfection and RNA was isolated. To measure knockdown levels of endogenous AGO2 by CRIPSRi, cells expressing the dCAS9-BFP-KRAB were infected with sgRNAs targeting AGO2 and harvested 4-5 days later to isolate RNA. RNA was isolated using TRIsure (Bio-line), according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Next, cDNA was generated using Bioscript reverse transcriptase (Bioline) and random hexamer primers. qPCRs were performed using SYBR-Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Rad Real-time PCR machines (CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System). RNA levels were normalized to the levels of GAPDH mRNA.

Quantification of smFISH experiments

To quantify the number of mRNAs based on smFISH, multiple Z slices were made (with an interslice distance of 0.5 μm each) and maximum intensity Z-projections were created). Dependent on whether we wished to quantify the number of mRNAs in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Extended Data Fig. 1b-f and Extended Data Fig. 2j), or tethered to the membrane (Extended Data Fig. 2j), maximum projections containing different slices were created. For measurements in the nucleus and cytoplasm, maximum projections which included all slices in which the nucleus was present (based on DAPI) were used (to prevent calling cytoplasmic mRNAs nuclear). To quantify the number of mRNAs tethered to the membrane, maximum projections of the two slices containing the bottom membrane were made. Using TransTrack, the nucleus was identified based on DAPI and the number of mRNAs at each location was quantified.

To quantify the percentage of co-localization between the SunTag and PP7 smFISH probes, mRNAs were identified using TransTrack based on the SunTag probe signal (Cy5). For each mRNA we manually determined whether the SunTag smFISH signal co-localized with the PP7 signal (Alexa 594).

To quantify the transcription site intensities, maximum intensity Z-projections were created (images were taken with an interslice distance of 0.5 μm each). To ensure that all the fluorescence signal of the transcription site was captured, the maximum intensity projections included all slices in which the nucleus was present (based on DAPI signal). To quantify the fluorescence intensity of the transcription site, an ROI was manually drawn around the transcription site, and the integrated fluorescence intensity was measured. For each spot the background fluorescence intensity was measured in the cytoplasm using a second ROI with the same dimensions. The background fluorescence intensity was subtracted from the transcription site fluorescence intensity.

Quantification of northern blots

Northern blot images were analyzed using ImageQuant TL. The total intensity of each band was measured and background was subtracted using the manual baseline option (i.e. the background intensity was measured manually). To control for loading differences, the RNA gel was analyzed and both the 18S rRNA and 28S rRNA integrated band intensity were measured. An average normalization factor was calculated based on the 18S rRNA and 28S rRNA integrated intensity and the northern blot band intensities were normalized accordingly.

Quantification of in vitro AGO2 on rate

RNA molecules were first localized in the reference movie through custom code written in IDL. Non-specific interactions of AGO2-siRNA complexes with the chamber surface (i.e. interactions that do not show co-localization with the RNA molecules) are ignored. Next, intensity time traces were created in the measurement movie for each RNA molecule (based on the positions of the RNA molecules in the reference movie) and the resulting intensity time traces were further processed in MATLAB (Mathworks) using custom code. To determine the binding rate, we measured the time between introduction of AGO2-siRNA complexes in the sample chamber and the time when stable binding occurred (stable binding is defined by interactions of > 1 s).

The binding time of AGO2 was calculated as the time between AGO2-siRNA complex introduction into the imaging chamber and the first stable binding event for each RNA molecule. For the short RNA oligonucleotide target, the majority of molecules was bound by an AGO2 molecule within our time window of 350 s. To calculate the on-rate, we fit the data with the following equation,

where F is the fraction of bound molecules, A the maximum bound fraction, t the time and kon the on rate.

For the full length mRNA targets, most molecules were not bound by an AGO2 molecule within our time window of 350 s. Therefore, it was not possible to fit the data with above equation and we instead linearized the equation resulting in,

The approximation is valid as long as the product kon · t is very small. Using the linearized equation, we fit the datapoints from the first hundred seconds to determine the value of A · kon. Next, we calculated the on rate (kon) by dividing with A. We took the value of A that we had fit with the short oligonucleotide target.

Statistics

Statistical comparisons were made using a two-tailed Student’s t-test except for data shown in Extended Data Fig. 1k, which was based on a paired two-tailed Student’s t-test. N values for each experiment can be found in Supplementary Table 1 and exact p values for all statistical comparisons can be found in the source data. All modeling and related statistics are described in Supplementary Notes 4-8.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

Custom code used in this study is available on Mendeley data (http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/h2r32zhgwn.1).

Data availability

A selection of the raw imaging data (related to figures 1-6) used in this study is available on Mendeley data (http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/h2r32zhgwn.1). Source data are available with the paper online.

Extended Data

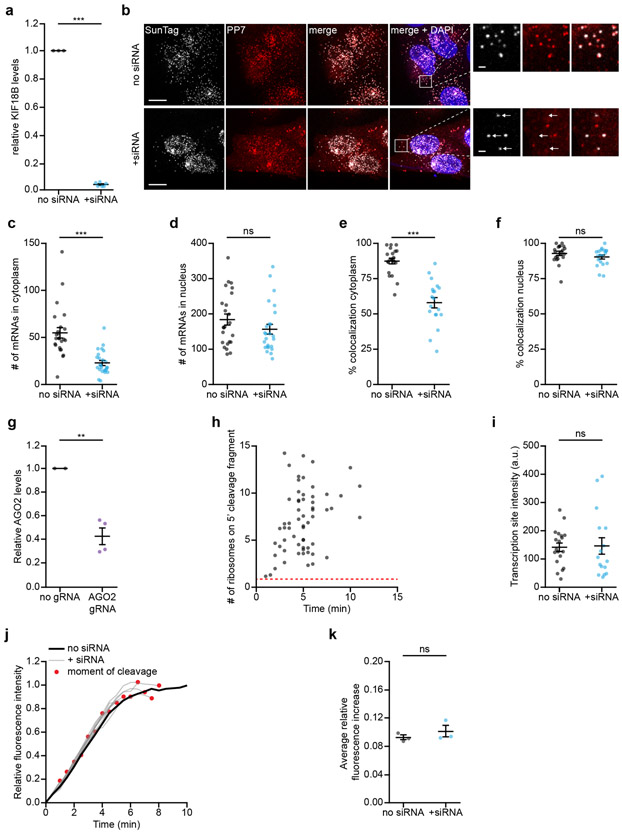

Extended Data Fig. 1. Effects of AGO2-siRNA complexes on mRNA transcription and translation.

a, Relative mRNA levels of endogenous KIF18B based on qPCR in non-transfected cells (no siRNA) and cells transfected with KIF18B siRNA #1 (+ siRNA). Each dot represents an independent experiment and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. b-f, i, Cells expressing the KIF18B reporter without siRNA (no siRNA) or transfected with 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #1 (+ siRNA) were fixed and incubated with smFish probes to visualize reporter mRNAs. b, Representative images of cells incubated with smFISH probes targeting the KIF18B reporter (SunTag-Cy5 and PP7-Alexa594) in no siRNA cells (upper panel) and + siRNA cells (lower panel). Arrows in insets indicate mRNA molecules for which the 5’ end (SunTag-Cy5 probe) and 3’ end (PP7-Alexa594 probe) do not co-localize. Scale bar, 10 μm in large images and 1 μm in insets. c-d, Number of mRNAs in no siRNA and + siRNA cells in (c) the cytoplasm and (d) the nucleus determined based on smFISH using probes targeting the SunTag sequence. Each dot represents a single cell and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. e-f, Percentage of mRNAs for which the 5’ end (labeled with SunTag probes) and 3’ end (labeled with PP7 probes) co-localized in no siRNA and + siRNA cells, either in (e) the cytoplasm or (f) the nucleus. Each dot represents a single cell and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. g, Relative AGO2 mRNA levels based on qPCR in control cells (no gRNA) and cells treated with a CRISPRi guide targeting endogenous AGO2 (AGO2 gRNA). Each dot represents an independent experiment and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. h, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the KIF18B reporter were transfected with KIF18B siRNA #1. The number of ribosomes present on the 5’ cleavage fragment was determined one frame after the moment of cleavage (see Supplementary Note 4). Dotted red line indicates the intensity of a single SunTag array (i.e. the intensity associated with a single ribosome). i, Cells were treated for 40 min with dox and the integrated intensity of transcription sites was determined with smFISH probes targeting the SunTag sequence. Each dot represents a single transcription site and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. j-k, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the KIF18B reporter were untransfected (no siRNA) or transfected with KIF18B siRNA #1 (+ siRNA). j, GFP intensity over time associated with individual mRNAs is shown for no siRNA cells (black line) and + siRNA cells (grey lines). Black line indicates average of all mRNAs in no siRNA cells, while each grey line represents the average GFP intensity of all mRNAs cleaved at the same moment relative to the start of translation (see Supplementary Note 5). The red dot indicates the moment of cleavage. k, Average increase in GFP fluorescence intensity either between 1.5-4 min after the start of translation (no siRNA) or at the moment preceding mRNA cleavage (+ siRNA) is shown (see Supplementary Note 5). Each dot represents the average of an independent experiment and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. a, c-f, g, i, P-values are based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. k, P-value is based on a paired two-tailed t-test. P-values are indicated as * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001), ns = not significant. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in a,c-k are available as source data.

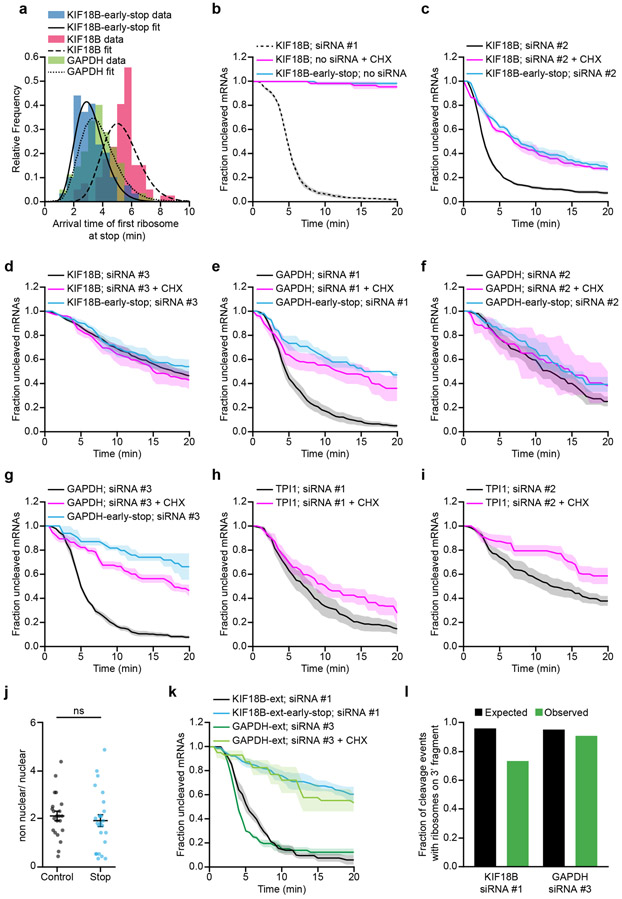

Extended Data Fig. 2. Ribosomes stimulate AGO2-dependent mRNA cleavage.

a, The moment at which the first ribosome arrived at the stop codon was calculated for indicated reporters. The experimental data (colored bars) was fit with a gamma distribution (black lines) (See Supplementary Note 5). b-i, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the indicated reporters were transfected with 50 nM (KIF18B siRNA #3) or 10 nM (all others) siRNA and treated with CHX, where indicated. The time from first detection of translation or from CHX addition until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. Dotted line indicates that the data is replotted from an earlier figure panel for comparison. j, Ratio of non-nuclear and nuclear mRNAs 90 min after addition of dox in cells expressing the KIF18B reporter (control) or KIF18B-early-stop reporter (Stop) as determined by smFISH using SunTag probes. Note that mRNA localization is similar for the two cell lines used for northern blot analysis (see Fig. 2e). Each dot represents one cell and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. P-value is based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. k, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the indicated reporters were transfected with 10 nM siRNA and treated with CHX, where indicated. The time from first detection of translation or from CHX addition (+ CHX) until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. l, The fraction of mRNAs that contains a ribosome on the 3’ cleavage fragment is shown for mRNAs on which translation started at least 7.5 minutes (KIF18B) or 6 minutes (GAPDH) before the moment of cleavage. On these mRNAs it is expected that the first ribosome has passed the AGO2 target site in ~95% of mRNAs (indicated by black bars) based on the experimentally-derived ribosome elongation rate. The expected fraction (black bars) and observed fraction (green bars) of mRNAs that contains a ribosome on the 3’ cleavage fragment is shown. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in a-l are available as source data.

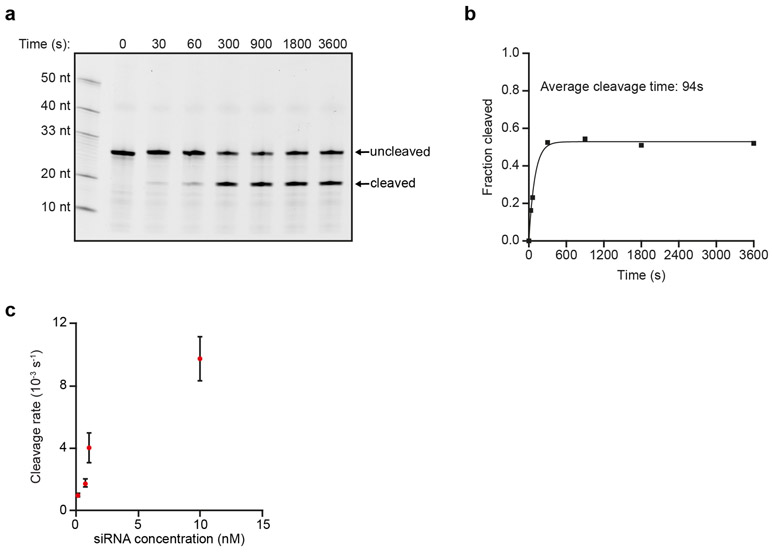

Extended Data Fig. 3. In vivo and in vitro kinetics of the AGO2 cleavage cycle.

a, In vitro AGO2 cleavage reaction with purified AGO2 loaded with KIF18B siRNA #1 and a short oligonucleotide target containing the KIF18B siRNA #1 target sequence. b, Quantification of the cleaved fraction of blot in (a). c, Calculated cleavage rates in the presence of translating ribosomes are shown for different siRNA concentrations (see Supplementary Note 4). Dots and error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in b,c are available as source data.

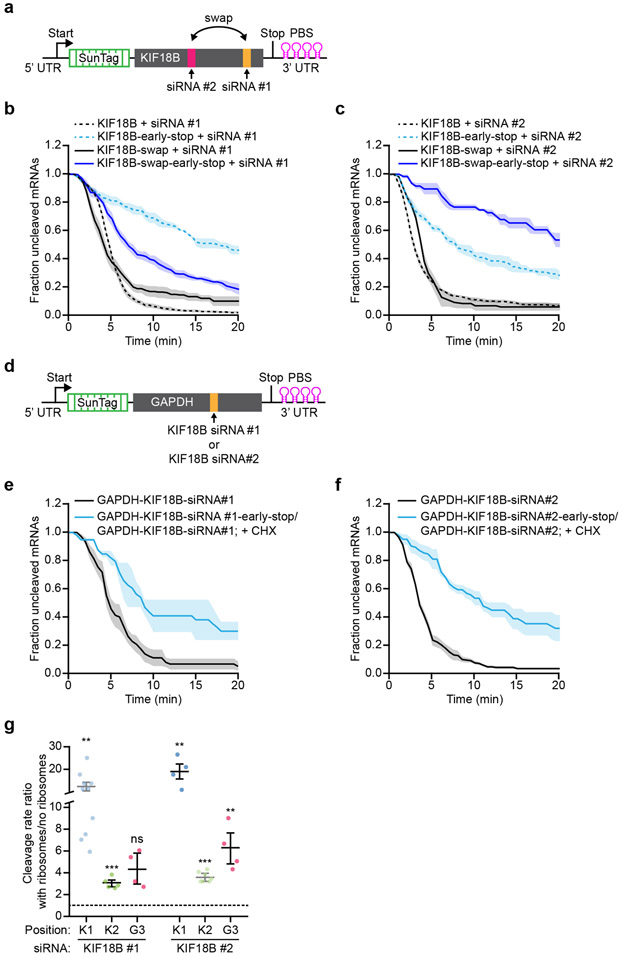

Extended Data Fig. 4. Degree of structural masking depends on the AGO2 binding sequence and the surrounding sequence.

a, Schematic of the KIF18B reporter in which the position of the siRNA #1 and siRNA #2 binding sites are swapped. b-c, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing indicated reporters were transfected with (b) 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #1 or (c) 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #2. The time from first detection of translation until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. Dotted lines indicate that the data is replotted from an earlier figure panel for comparison. d, Schematic of the GAPDH reporter in which the KIF18B siRNA #1 or KIF18B siRNA #2 binding site is placed at the position of GAPDH siRNA #3. e-f, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the indicated reporters were transfected with (e) 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #1 or (f) 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #2. The time from first detection of translation or CHX addition until mRNA cleavage is shown. Note that data of the KIF18B-early-stop reporter and KIF18B reporter treated with CHX are combined to generate the cleavage curve for cleavage in the absence of ribosomes. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. g, Ratio of cleavage rate in the presence and absence of ribosomes is shown for the indicated siRNAs and reporters (see Supplementary Note 4). Each dot represents a single experiment and lines with error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. P-values are based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. P-values are indicated as * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), *** (p < 0.001). K1, K2 and G3 indicate the position of the indicated siRNA. K1 refers to the position of KIF18B siRNA #1, K2 to KIF18B siRNA #2 and G3 to GAPDH siRNA #3. Light blue and light green data points are replotted from an earlier experiment. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in b,c,e-g are available as source data.

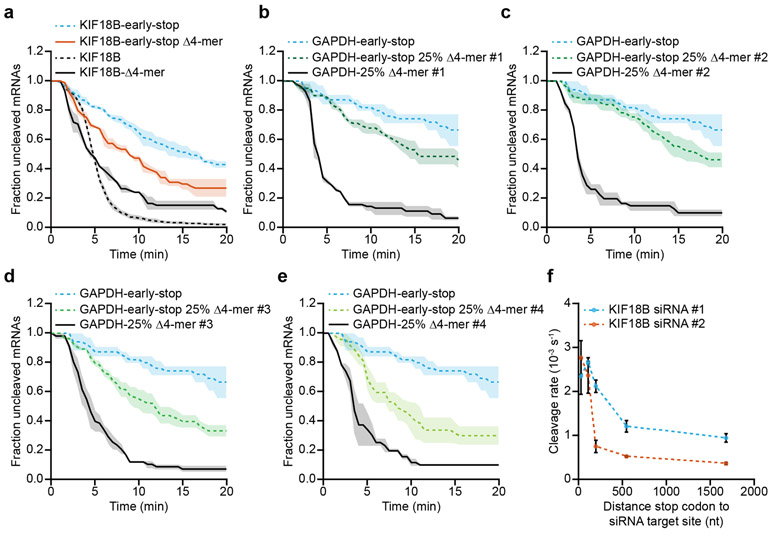

Extended Data Fig. 5. Multiple weak intramolecular mRNA interactions together result in potent AGO2 target site masking.

a-e, SunTag-PP7 cells expressing the indicated reporters were transfected with (a) 10 nM KIF18B siRNA #1 or (b-e) 10 nM GAPDH siRNA #3. The time from first detection of translation until separation of GFP and mCherry foci (i.e. mRNA cleavage) is shown. Solid lines and corresponding shaded regions represent mean ± SEM. Dotted lines indicate that the data is replotted from an earlier figure panel for comparison. f, Cleavage rates for the ‘luciferase’ reporters with indicated siRNA target sites and with different distances between the stop codon and the siRNA target site are shown. Each dot and error bar indicate the mean ± SEM. Dotted lines are only for visualization. Number of measurements for each experiment is listed in Supplementary Table 1. Data for graphs in a-f are available as source data.

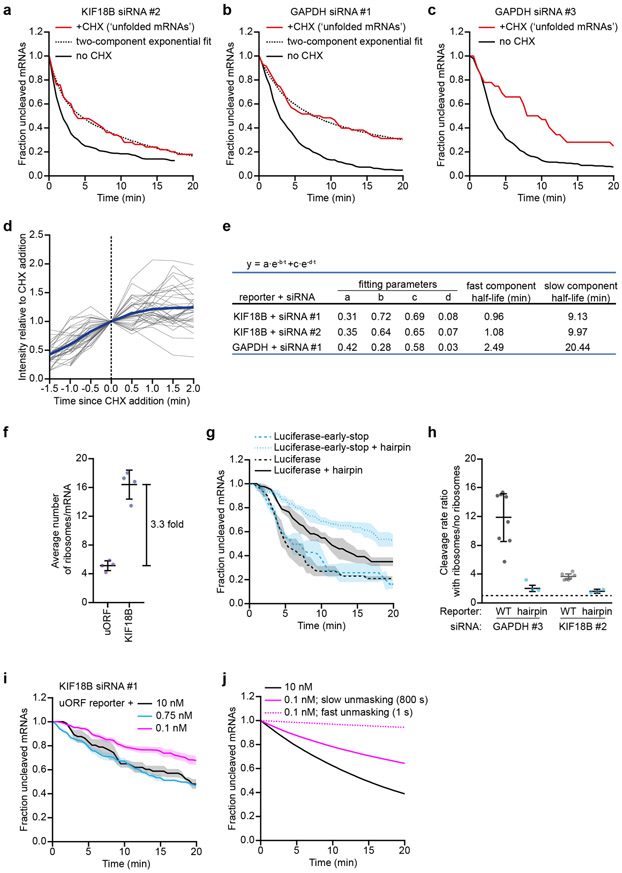

Extended Data Fig. 6. Structural dynamics of RNA folding.