Abstract

Objectives

The management of the COVID-19 pandemic hinges on the approval of safe and effective vaccines but, equally importantly, on high vaccine acceptance among people. To facilitate vaccine acceptance via effective health communication, it is key to understand levels of vaccine scepticism and the demographic, psychological and political predictors. To this end, we examine the levels and predictors of acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine.

Design, setting and participants

We examine the levels and predictors of acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine in large online surveys from eight Western democracies that differ in terms of the severity of the pandemic and their response: Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Sweden, Italy, UK and USA (total N=18 231). Survey respondents were quota sampled to match the population margins on age, gender and geographical location for each country. The study was conducted from September 2020 to February 2021, allowing us to assess changes in acceptance and predictors as COVID-19 vaccine programmes were rolled out.

Outcome measure

The outcome of the study is self-reported acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine approved and recommended by health authorities.

Results

The data reveal large variations in vaccine acceptance that ranges from 83% in Denmark to 47% in France and Hungary. Lack of vaccine acceptance is associated with lack of trust in authorities and scientists, conspiratorial thinking and a lack of concern about COVID-19.

Conclusion

Most national levels of vaccine acceptance fall below estimates of the required threshold for herd immunity. The results emphasise the long-term importance of building trust in preparations for health emergencies such as the current pandemic. For health communication, the results emphasise the importance of focusing on personal consequences of infections and debunking of myths to guide communication strategies.

Keywords: COVID-19, public health, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large samples that are reflective of the populations of eight different countries, allowing us to examine the generalisability of findings and the factors underlying cross-national differences.

A broad-based assessment of potential correlates of vaccine acceptance, including demographic, political and COVID-specific factors.

Analyses that include observations, both preapproval and postapproval of COVID-19 vaccines.

Observational data which limit causal traction.

Self-reported vaccine acceptance can be subject to social desirability bias and does not necessarily translate into actual vaccination rates.

Background

A vaccine against COVID-19 is a ‘vital tool’ in the management of the current pandemic.1 Accordingly, extraordinary resources have been invested into vaccine development with unprecedented speed. Yet, even as approved vaccines become available, societies across the world still face another challenge: vaccine scepticism.

As of late 2020, researchers estimated that up to 82% of a country’s population may need to be vaccinated in order to reach herd immunity against SARS-CoV-2,2 3 and the emergence of new virus variants implies that individuals may need to get vaccinated repeatedly. However, general vaccine hesitancy has been on the rise in recent years in many countries.4 5 This has been the case for many non-COVID-19 vaccine programmes and is likely to pose a challenge for COVID-19 vaccines.6 7 Consistent with this, initial cross-national survey evidence suggests that substantially fewer people worldwide are willing to get vaccinated than would be necessary, and that some countries—for example, Russia, Poland and France—face strikingly high levels of scepticism.8 Thus, a key challenge for pandemic management is for health authorities across the world to encourage people to accept approved COVID-19 vaccines through careful approval procedures and effective health communication. This latter challenge emphasises the importance of understanding why people are hesitant about taking vaccines. Such knowledge is crucial for guiding communication in a way that increases vaccine acceptance and for understanding how to prepare for future health emergencies.

In this article, we first present descriptive analyses of the acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine approved and recommended by health authorities across eight Western democracies. Second, we investigate individual-level predictors of vaccine acceptance. Third, we also explore macro-level correlations of vaccine acceptance. The study was conducted from the fall of 2020 to the winter of 2021. This data collection thus allows us to track levels and predictors of vaccine acceptance as vaccines were approved using large-scale cross-national surveys including a broad set of potential predictors, eg, political predictors, which are less often explored in traditional health research. Given the scale and broad impact of a pandemic crisis, however, such broader predictors may be particularly relevant to explore.

Potential predictors: who are expected to accept a COVID-19 vaccine?

To organise our expectations about the individual-level predictors of vaccine acceptance during the COVID-19 pandemic, we draw on one of the most comprehensive frameworks for understanding the antecedents of vaccine acceptance; the 5C model from Betsch et al.9 According to the 5C model, five psychological antecedents drive vaccine acceptance: confidence, constraints, complacency, calculation and collective responsibility. While we consider multiple predictors that are often not considered within this model, we strengthen the model’s coverage by theorising the link between the components of the model and the novel predictors that may be important for vaccine acceptance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Confidence is defined as trust in (1) the effectiveness and safety of vaccines, (2) the system that delivers them and (3) the motivation of policy-makers who decide on the need for vaccines.9 10 Here, we consider two categories of predictors that reflect the underlying dimensions of confidence. First, we broadly tap into the second dimension of the definition by focusing on trust in a range of actors. Second, we investigate a range of political attitudes that broadly reflect the third dimension of the definition.

Empirically, trust is a crucial predictor of vaccine acceptance. Guay et al, for example, found that distrust in public health authorities is associated with general vaccine hesitancy.11 Similarly, people who trust official authorities were more likely to accept the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV).12 Initial work on COVID-19 vaccines also demonstrates that those who have higher trust in scientists are more willing to get vaccinated.13

Furthermore, the literature on vaccine hesitancy has found that hesitancy is integrated into a broader set of political attitudes and perceptions. Political ideology has been found to be related to vaccine hesitancy as conservative individuals are less likely to trust authorities.14 Furthermore, it is a standard finding in political science that individuals are less likely to accept decisions from other political parties than the one they identify with or vote for.15 Thus, it is plausible that people who have voted for the government party/candidate are more likely to accept a vaccine, since the vaccine programme is a part of the governments’ response to the pandemic. In addition to these standard political attitudes, more extreme attitudes may also influence confidence in vaccines. Most prominently, people prone to conspiracy thinking are more likely to be hesitant about vaccines.16 17 In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, higher levels of conspiratorial thinking have also been found to be associated with lower acceptance of future vaccines against COVID-19.18–20 Consequently, it can be expected that vaccine acceptance during the COVID-19 pandemic may relate to antisystemic sentiments such as conspiratorial thinking. We examine three levels of antisystemic sentiments and how they relate to vaccine acceptance, including (1) concern for democratic rights, (2) support for public protests against government policies and (3) beliefs in specific conspiracy theories related to COVID-19. Finally, we also examine the role of awareness of misinformation. From the literature, we know that susceptibility to misinformation negatively affects people’s acceptance of a vaccine against COVID-19.21 However, studies have also shown that prebunking can help cultivate ‘mental antibodies’ against misinformation.22 23 Thus, it is likely that awareness of misinformation is positively associated with vaccine acceptance.

Constraints refer to the structural and psychological barriers, impeding the implementation of vaccination intentions into behaviour.9 We consider the feeling of ‘pandemic fatigue’ as such a barrier and thus a potential correlate of vaccine acceptance. While the WHO has been warning about fatigue among populations in the fall of 2020,24 25 it is plausible that people who feel fatigued are willing to do what it takes to end the pandemic, including being vaccinated. However, fatigue could also generate an unwillingness or incapability to comply with further requirements, including vaccinations. Furthermore, we include the sense of having sufficient knowledge about behavioural recommendations as another psychological barrier. A sense of self-efficacy about proper behaviour was one of the best predictors of compliance with physical distancing policies during the first wave of the pandemic.26 Furthermore, perceived insufficient knowledge is significantly associated with general vaccine hesitancy.11 Finally, we assess remaining psychological constraints by assessing to what extent people report being able to change their behaviour in accordance with the recommendations from health authorities during the pandemic. This general measure of behaviour change should serve as a proxy for the range of constraints that may serve as a barrier for action over and beyond the directly assessed factors.

Complacency ‘exists where perceived risks of vaccine-preventable diseases are low and vaccination is not deemed a necessary preventive action’.9 10 Here we consider two types of predictors, including demographic factors and corona-specific risk perceptions.

First, a set of demographic predictors are expected to be associated with complacency. Thus, prior studies have found that men are more likely than women to accept a potential COVID-19 vaccine,27–29 potentially due to sex-based differences in COVID-19 mortality.27 Likewise, older people are expected to be more willing to take a vaccination due to higher risks of severe infections. This is supported by Lazarus et al8 and Hacquin et al,29 while neither Dror et al27 nor Wong et al28 found any age differences in vaccine acceptance. As a final demographic variable, we also consider education, even though this variable may influence vaccine acceptance through other dimensions than complacency (eg, confidence). The findings of prior studies on vaccine hesitancy are mixed with regard to education, indicating that that the association between education and vaccine hesitancy is context specific.30 To illustrate, whereas Guay et al found that lower education was associated with general vaccine hesitancy in Canada,11 Wagner et al found that educational level was not associated with general vaccine hesitancy across five low-income and middle-income countries.30 Similarly, Bertoncello et al found that while low parent education was significantly associated with general vaccine hesitancy, it was not associated with hesitancy in the context of child vaccine programmes in Italy.31 In the context of COVID-19, studies have found that higher education is associated with higher levels of vaccine acceptance.8 29

Second, we also investigate the role of personal risk perceptions. Several studies have found that self-perceived risks of COVID-19 positively predicts acceptance of potential COVID-19 vaccines.19 27 29 Likewise, Wong et al argued that perceived susceptibility to infection predicted the intention to take a future COVID-19 vaccine.28 Thus, we expect that personal risk perception predicts vaccine acceptance.

Collective responsibility is defined as the willingness to protect others by one’s own vaccination by means of herd immunity.9 32 We consider three groups of predictors to be relevant for this category of vaccine antecedents: (1) prosocial concerns (ie, concern for others), (2) support for pandemic restrictions and (3) interpersonal trust.

Focusing first on prosocial concerns, we measure a range of concerns over the disease’s impact on society, including hospitals’ ability to help the sick, society’s ability to help the disadvantaged, social unrest and crime, and the country’s economy. These concerns clearly tap into the collective responsibility and can be expected to positively predict vaccine acceptance, given that vaccine uptake can be viewed as a form of other directed behaviour that protects individuals beyond the self.

Second, we examine the association between compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine acceptance. Protective behaviour thus might be viewed as a collective good, implying that compliance with health advice might reflect the willingness to protect others rather than being individually rational to protect oneself.33 Here, we specifically investigate support for non-pharmaceutical interventions, that is, government restrictions to stop infection spread as a direct measure of the acceptance of collective responsibility.

Third, interpersonal trust may be a key predictor of the willingness to contribute to collective action during the COVID-19 pandemic.33 Vaccination is a form of collective action, where herd immunity is produced via the collective participation in vaccination programmes,34 and people may be more likely to participate if they trust others to do the same.

Table 1 in the Methods section shows the specific operationalisation of each of these predictors and summarises how these predictors are related to the 5C model. As is evident, we do not include measures that reflect the calculation component of the 5C model. From a communication perspective, however, this component is less important as it refers not to the content of the individual’s considerations but to more stable individual differences in decision-making style (ie, extensive cost–benefit analyses of pros and cons of vaccination and infection).9

Table 1.

Main measures in the study

| Questions | Values | |

| Vaccine acceptance | If the health authorities advise people like me to get an approved vaccine against the coronavirus, I will follow their advice. |

|

| Confidence | Trust in health authorities and scientists How much trust do you have in the following institutions regarding the coronavirus crisis?

|

|

| Trust in the government Give your assessment on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates that you have no confidence in the government at all, and 10 indicates that you have full confidence in the government. |

0. No confidence at all. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Full confidence. |

|

| Attitudes To what extent do you agree with the following statements?

|

|

|

| Vote choice What party/who did you vote for in the last general election/presidential election? (date of last election) |

(country-specific party/candidate categories) | |

| Ideology In political matters, people talk of ‘the left’ and ‘the right’. How would you place your views on this scale, generally speaking? |

1. The left. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. The right. |

|

| Constraints | Fatigue To what extent do you agree with the following statements? I do not think I can keep up with the restrictions against the coronavirus for much longer. |

|

| Behaviour change To what degree do you feel that the current situation with the coronavirus has made you change your behaviour to avoid spreading infection? |

|

|

| Knowledge To what degree do you feel that you know enough about what you as a citizen should do in relation to the coronavirus? |

|

|

| Complacency* | Sex Are you |

|

| Age What is your age? |

(open text box) | |

| Education What is your highest level of completed education? |

(country-specific education categories) | |

| Personal risk perceptions To what degree are you concerned about the consequences of the coronavirus for you and your family? |

|

|

| Collective responsibility | Prosocial concerns To what degree are you concerned about the consequences of the coronavirus

|

|

| Support for restrictions As you may know, many countries have implemented various measures to stop the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic. We are interested in whether you support or oppose the following measures in your country:

|

|

|

| Interpersonal trust Do you think that most people by and large are to be trusted, or that you cannot be too careful when it comes to other people? |

0. You cannot be too careful. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Most people are to be trusted. |

Mean and SD of all measures are available in online supplemental appendix table A2.

*See text for discussion of the relationship between demographic variables and complacency (p. 2–3).

bmjopen-2020-048172supp001.pdf (3.4MB, pdf)

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Data

We fielded quota-sampled surveys in eight countries from 13 September 2020 until 16 February 2021: Denmark, Sweden, the UK, the USA, Italy, France, Germany and Hungary (please see online supplemental appendix table A1 for an overview of the data collection). These countries were chosen to represent a diversity of national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as a diversity in the severity of the local epidemic. The period consists of eight data rounds in Denmark and seven data rounds in the remaining countries, with approximately 500 respondents per data round. In each of the eight countries, the survey company Epinion sampled adult respondents using online panels. Among the panellists invited to take our survey, the response rate across the countries in our sample was between 18% (Hungary) and 64% (the USA). Survey respondents were quota sampled to match the population margins on age, gender and geographical location for each of the eight countries. We address imbalances by poststratifying our sample data to match the demographic margins from the population. All statistical analyses presented in the article employ these poststratification weights.

Measures

All measures are self-reported from participant questionnaires. The key measures are vaccine acceptance, trust in relevant authorities and groups, disease-specific risk-perceptions, disease-specific attitudes and propensities to engage in protective behaviour. Table 1 provides an overview of question wordings and scales for these measures.

Vaccine acceptance

Our outcome, vaccine acceptance, is measured using the following question: ‘If the health authorities advise people like me to get an approved vaccine against the coronavirus, I will follow their advice’. Thus, our measure is framed as an approved vaccine that is recommended by the national health authorities. This choice reflects that (1) we focus on COVID-19 vaccines, specifically (2) during a global health crisis, where health authorities are emergency approving and very actively encouraging people to take up new vaccines. Some of these important factors are overlooked by previous validated vaccine acceptance measures developed prepandemic for measuring attitudes towards vaccines in general. Framing the question in the context of the national health authorities may, however, yield different results than if a standardised and validated measure of vaccine acceptance was used. Furthermore, this choice makes it difficult to compare our results with other studies of vaccine acceptance.9 Although Betsch et al recommend the use of a general scale, they also acknowledge that this might not be useful when the focus of a study is on a specific vaccine.9

Our outcome, vaccine acceptance, is a continuous variable rescaled to range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher levels of vaccine acceptance.

Predictors of vaccine acceptance

All measures of trust, concern and disease-specific attitudes are treated as continuous variables and rescaled from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher levels of trust, concern and agreement with the disease-specific statements. For our compliance measures, behaviour change and knowledge are treated as continuous variables and rescaled to range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher levels of behaviour change and knowledge. Furthermore, we create an index of support for restrictions by adding together the nine measures of support for restrictions. The index is scaled from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher levels of support for restrictions. ‘Do not know’ answers are classified as missing and are not included in the analysis. Sex is an indicator variable (0 for men and 1 for women). Age is a continuous variable rescaled from 0 to 1 with 0 being the minimum age in the sample (18 years) and 1 being the maximum age (99 years). Education is an indicator variable based on the internationally comparable International Standard Classification of Education scale (ISCED) (0 for non-tertiary education and 1 for tertiary education). Vote choice is an indicator variable (0 for opposition and 1 for government) (see online supplemental appendix table A3 for the coding of this variable). Finally, political ideology is a continuous variable rescaled to range from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the ideological standpoint to the utmost right.

To ease the interpretation of the results, both the outcome and all predictors are scaled from 0 to 1 in the following analyses. Online supplemental appendix table A2 reports the descriptive statistics for all the aforementioned correlates in our overall sample. Moreover, online supplemental appendix figure A1 shows an overview of all bivariate correlations.

Statistical analyses

Since our dependent variable, vaccine acceptance, is continuous, we used ordinary least squares regression models to investigate the individual-level predictors of vaccine acceptance. In the Results section, we present two models: (1) model I, a model with all the bivariate correlations of vaccine acceptance, and (2) model II, a full model that includes all predictors described earlier. Model II includes country dummies to control for country-specific effects. Thus, our aim was to identify individual-level predictors of acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. To account for the fact that individuals are nested within countries, we cluster the SEs at the country level.

In the online supplemental appendix, we conduct a range of sensitivity analyses that probe the robustness of our benchmark results. First, we replicate the main analyses while treating the 4-point scale measures of trust, concern, behaviour change and knowledge as categorical variables instead of continuous variables (see online supplemental appendix figure A2–A5). Second, we similarly replicate the analyses while using a dichotomous—rather than a continuous—coding of the outcome (for the dichotomous outcome measure, respondents who answered ‘somewhat agree’ or ‘completely agree’ are coded as 1, indicating vaccine acceptance) (see online supplemental appendix figure A6). Third, the present results reflect the analysis period between 13 September 2020 and 16 February 2021. Thus, we included data both preapproval and postapproval of the COVID-19 vaccines. In the online supplemental appendix, we compared the results before and after COVID-19 vaccines were approved (see online supplemental appendix figure A7). Fourth, in some contexts—most notably the countries with federal states (the USA and Germany) in our sample—much of the COVID-19 response is done on a regional level. To account for state-specific heterogeneity, we analysed the individual-level predictors separately in Germany and the USA while controlling for state-level rather than country-level dummies (see online supplemental appendix figure A8–A10). The results are essentially similar to those presented in the main text.

Results

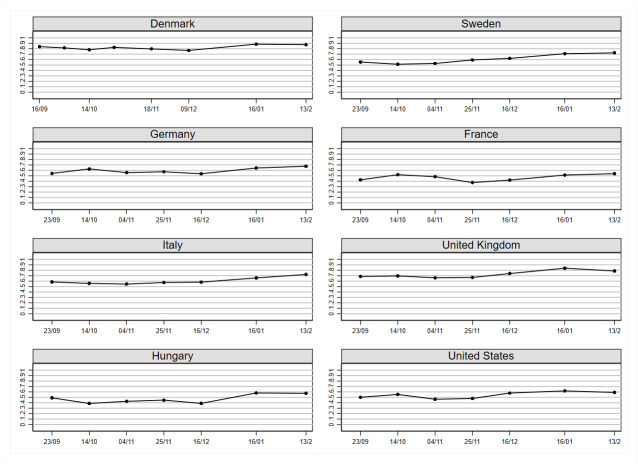

Figure 1 shows the development in vaccine acceptance by country. For the following descriptive analyses, we refer to the percentage who accept the vaccine (ie, share of respondents who answered ‘somewhat agree’ or ‘completely agree’ to whether they will follow the advice of the health authorities and get an approved vaccine). This percentage refers to the level of vaccine acceptance for the full analysis period, that is, September 2020—February 2021.

Figure 1.

Development in vaccine acceptance for an approved COVID-19 vaccine. Note: N=18 231. The figure illustrates the development in vaccine acceptance across countries. Vaccine acceptance is defined here as the proportion who answers ‘somewhat agree’ or ‘completely agree’ to the question ‘If the health authorities advise people like me to get an approved vaccine against the coronavirus, I will follow their advice’.

Across the eight countries, we observed large differences in the level of vaccine acceptance. Specifically, we observed the highest level of vaccine acceptance in Denmark (83 %). Furthermore, we observed a high level of vaccine acceptance in the UK (73 %). However, we observed only moderate levels of vaccine acceptance in Sweden (61 %), Germany (60 %), Italy (60 %) and the USA (54 %). The lowest levels of vaccine acceptance were observed in France (47 %) and Hungary (47 %). However, it is worth noticing that in most of the countries, we observed increasing levels of vaccine acceptance over the course of the pandemic as COVID-19 vaccines were being approved and rolled out.

The results indicate that vaccine scepticism is present in most of the countries in our sample. These results underscore two important points. First, the presence of vaccine scepticism demonstrates the importance of understanding the individual-level variation of vaccine acceptance in order to understand the targets of health communication. Second, the large variation across countries emphasises the need of a more thorough understanding of the importance of national context. Therefore, we also move beyond the individual-level focus to explore macro-level correlations of vaccine acceptance.

On this basis, we first turn towards understanding the individual-level predictors of acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Figure 2 presents the results of the analyses (see online supplemental appendix table A4). In the following discussions of results, we specifically focus on the estimated correlations from model II in online supplemental appendix table A4 (the full model). The size of the estimated coefficients reported further reflects the difference in vaccine acceptance when we compare individuals at the minimum and maximum values, respectively, for each of the correlates.

Figure 2.

Individual-level correlations of vaccine acceptance. N=18 231. Black circles are the estimated correlations based on models I and II in online supplemental appendix table A4. Model II (the full model) includes control for country dummies. Horizontal bars are the associated 95% CIs.

Examining the confidence predictors, we observe that trust in the health authorities and trust in scientists are the strongest predictors of vaccine acceptance. Respondents who have the highest level of trust in the national health authorities have 17 (95% CI 14 to 20) percentage points higher acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine compared with those with the least trust. The same pattern is observed for trust in scientists. Respondents with the highest level of trust have 21 (95% CI 16 to 26) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine compared with those with the lowest trust level. Furthermore, trust in the government is also significantly positively predicting vaccine acceptance. Respondents high in government trust have 5 (95% CI 0 to 10) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine compared with those with the lowest level of trust. Focusing on the attitudinal aspect of confidence predictors, we observe that conspiracy beliefs significantly negatively predict vaccine acceptance, while awareness of misinformation significantly positively predicts vaccine acceptance. Specifically, respondents who score highest in thinking that the government is hiding information about the coronavirus and its cures (conspiracy beliefs) have 8 (95% CI 5 to 12) percentage points lower acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine compared with those who do not subscribe to conspiracies. Respondents who think that they have been exposed to misinformation have 4 (95% CI 1 to 7) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine. Both concern about democratic rights and support for protests are negatively, but not significantly, associated with vaccine acceptance. Finally, neither political ideology nor vote choice is significantly associated with vaccine acceptance.

Moving to the constraints predictors, we observe that behaviour change is a significant positive predictor of vaccine acceptance. Specifically, respondents who have changed their behaviour the most to avoid spreading infection have 11 (95% CI 7 to 14) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine compared with respondents who have changed their behaviour the least. Neither fatigue nor knowledge is a significant predictor of vaccine acceptance.

Focusing on the complacency predictors, we observe that being male, older and having tertiary education are associated with higher vaccine acceptance. Specifically, women have 5 (95% CI 3 to 7) percentage points lower acceptance of an approved vaccine compared with men. Age positively predicts vaccine acceptance: when comparing respondents at the minimum and maximum levels of age in the sample (18–99 years), the difference is 19 (95% CI 12 to 26) percentage points. Furthermore, respondents with tertiary education have 2 (95% CI 1 to 3) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine compared with respondents with non-tertiary education. Finally, personal risk perception is also a positive predictor of vaccine acceptance. The respondents who are the most concerned about the consequences of the corona crisis for themselves and their families have 9 (95% CI 3 to 14) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine compared with the least concerned.

Finally, looking at the collective responsibility predictors, the strongest predictors of vaccine acceptance is support for restrictions. Specifically, respondents who are most supportive of restrictions have 13 (95% CI 9 to 17) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved vaccine compared with respondents who are the least supportive of restrictions. Furthermore, interpersonal trust positively predicts vaccine acceptance. Respondents with the highest level of interpersonal trust have 6 (95% CI 3 to 9) percentage points higher acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine compared with respondents with the lowest interpersonal trust level. Concern for the capacity of hospitals is also a positive predictor of vaccine acceptance. Comparing those who are the most concerned for the capacity of hospitals to those who are the least concerned shows a 5 (95% CI 2 to 8) percentage point increase in vaccine acceptance. Additionally, concern for social unrest and crime negatively predicts vaccine acceptance. Comparing those who are the most concerned for social unrest and crime to those who are the least concerned shows a 3 (95% CI 1 to 5) percentage point decrease in vaccine acceptance. Finally, neither concern for the society’s ability to help the disadvantaged nor concern for the country’s economy is significantly associated with vaccine acceptance.

The relationship between the predictors and vaccine acceptance is essentially the same across the bivariate and the full model. However, ideology changes from being significant and negative in the bivariate model to insignificant and positive in the full model. Furthermore, concern for the society’s ability to help the disadvantaged changes from being significant and positive in the bivariate model to insignificant and negative in the full model. Overall, the empirical patterns are relatively stable across countries, but we do observe some notable cross-country differences with respect to specific predictors (see online supplemental appendix figures A11 and A12). In Denmark, neither trust in scientists nor personal risk perceptions are significant predictors of vaccine acceptance (see online supplemental appendix figure A11). Focusing on heterogeneity across individual-level demographic subgroups, we see that results are essentially homogenous across sex, age and educational level (see online supplemental appendix figures A13–A15). Even though the levels of vaccine acceptance have changed over the course of the pandemic, the results of the individual-level predictors of vaccine acceptance are essentially the same when results preapproval and postapproval of COVID-19 vaccines are compared (see online supplemental appendix figure A7).

While trust in the national health authorities and scientists are the most prominent factors together with personal risk perceptions when everything is assessed individually, the data also show that vaccine scepticism during the pandemic is interwoven into a larger web of attitudes and behaviours related to antisystemic sentiments. Hence, in addition to trust in health authorities, a lack of vaccine acceptance was also related to endorsement of conspiracy beliefs, support for other non-pharmaceutical interventions and a lack of compliance with advice about changing behaviour to avoid spreading infections.

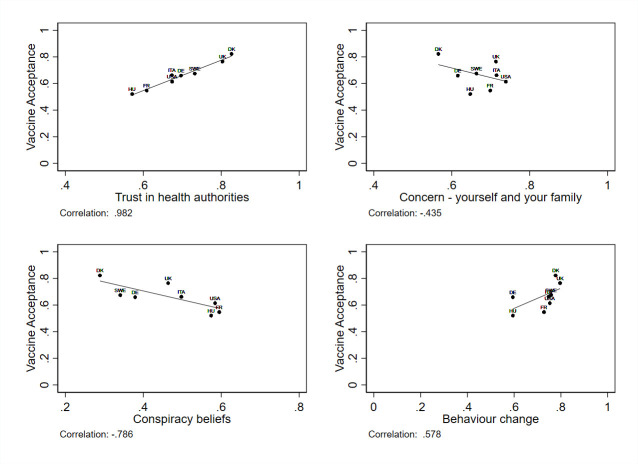

As a final explorative analysis, we therefore assess whether the highlighted factors also help explain the cross-national variation in vaccine acceptance. To this end, we examine the correlations between vaccine acceptance at the national level and each of the different independent measures aggregated for each country. All of these correlations are available in online supplemental appendix figure A16. In figure 3, we present the correlations for key variables highlighted previously: trust in health authorities, personal risk perceptions, conspiracy beliefs and behaviour change. While the analysis is highly limited by the fact that it only includes eight national cases, it is nonetheless strikingly informative. While differences in personal risk perceptions are not strongly related to cross-national differences, country averages in the antisystemic measures, especially (lack of) trust in health authorities, are exceptionally closely related to country averages in vaccine acceptance. Thus, trust in health authorities does not just explain differences in vaccine acceptance between individuals but also between countries.

Figure 3.

Macro-level correlations of vaccine acceptance. The figure plots country averages for vaccine acceptance and country averages for four measures: trust in health authorities, egotropic concern related to COVID-19, endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and the degree of changed behaviour to avoid spreading infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reported correlations are Pearson’s r.

Discussion

In this article, we investigated (1) the level of vaccine acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine, (2) individual-level predictors of vaccine acceptance and (3) macro-level correlations of vaccine acceptance. While levels of vaccine acceptance generally increased when COVID-19 vaccines were approved during the winter of 2020–2021, the results also demonstrate that for many of the countries in our sample, people are only moderately willing to receive a vaccine. This highlights the need for understanding the individual-level variation underlying vaccine scepticism and identifying potential targets for guiding health communication to increase vaccine acceptance.

The analyses of individual-level predictors demonstrate that the key drivers of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance are (1) trust in the national health authorities and scientists, and (2) personal health concerns. These results are consistent with findings of similar studies that emphasise that those who have more trust in experts and scientists are more willing to vaccinate.13 35 Likewise, several studies have also found personal risk perception to be an important predictor of acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine.20 27 29 36 Furthermore, Neumann-Böhme and Sabat find that the most frequently used reason for vaccination is to protect the respondents own and family members health.37 Motta et al also find that messages emphasising the personal risks at failing to vaccinate are effective in convincing people to plan to get vaccinated.38 Thus, in the framework of the 5C model from Betsch et al, scepticism towards a COVID-19 vaccine primarily results from complacency or a lack of confidence.9 Using these insights is essential to guide health communication in a way that can potentially increase vaccine acceptance.39 Specifically, our findings suggest that efforts should be focused on motivating the complacent, that is, those who lack concerns about the personal consequences of the pandemic. This can be done through informational interventions to explain disease risks and stress the social benefits of vaccination.39 When it comes to individuals with a lack of confidence, they usually possess a considerable amount of incorrect knowledge that distorts risk perceptions and undermines the general trust in vaccination.39 Consistent with this, the present findings also highlight conspiracy beliefs as a key predictor of vaccine hesitancy. Following Betsch et al, this implies that interventions aiming at debunking myths is key for increasing vaccine acceptance among those who lack confidence.39 At the same time, it is relevant to note that strategies aimed at those who lack confidence are scarce and there may thus also be value in focusing on motivating the complacent.39

In sum, these analyses point to the significant challenges involved in convincing vaccine sceptics. The web of antisystemic attitudes and distrust that vaccine scepticism is interwoven in makes it difficult to craft efficient health communication, as the effectiveness of communication is fundamentally contingent on the preceding existence of trust in its source. This challenge might be further deepened during the COVID-19 pandemic as research suggests that the stress of the pandemic and the restrictions itself fuel antisystemic beliefs.40 The results thus, first, emphasise the general importance of building trust prior to the onset of crises and of investing significant resources into maintaining trust as a crisis unfolds.41 Second, for most short-term oriented communication purposes, the results suggest that the best communication targets are the consequences of infections for the self and close others and debunking of myths.

The conclusions should however be considered in the light of the following limitations. First, the results are based on observational data, which limits causal traction. Second, we investigate self-reported vaccine acceptance and, thus, not actual vaccination behaviour. Therefore, we cannot be certain that acceptance of the vaccine translates into actual vaccination rates, since self-reported vaccine acceptance can be subject to social desirability bias. Importantly, several studies have found a high level of consistency between self-reported vaccine acceptance and actual vaccination rates.42–44

Conclusion

The results demonstrate that vaccine scepticism is present in most of the countries in our sample, even after vaccines have been approved. Consistent with similar studies, the analyses of the individual-level predictors show that the key individual drivers of acceptance of an approved COVID-19 vaccine are (1) trust in the national health authorities and scientists and (2) personal health concerns. The results suggest that an important communication target is the consequences of infections for the self and close others. Furthermore, these results emphasise that anything that erodes trust in health authorities and scientists are problematic for vaccination efforts and, thus, underscore the key importance of health and political authorities to strive to uphold trust to the maximum extent during the pandemic. This is not just crucial for managing the pandemic here and now but also as a preparation for the next health emergency.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for research assistance from Magnus Storm Rasmussen.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Fly_Lindholt

Contributors: MFL, FJ, AB and MBP designed the study and collected data; MFL and FJ analysed the data; MFL, FJ, AB and MBP wrote the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by The Carlsberg Foundation grant number CF20-0044 to MBP.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository at Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/27y3z/.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study complies with Aarhus University’s Code of Conduct as well as the Committee Act of the Danish National Committee of Health Research Ethics, which states that ‘Surveys using questionnaires and interviews that do not involve human biological material (section 14(2) of the Committee Act)’ are exempted from approval (https://en.nvk.dk/how-to-notify/what-to-notify).

References

- 1.WHO . WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 21 August 2020, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-21-august-2020

- 2.Britton T, Ball F, Trapman P. A mathematical model reveals the influence of population heterogeneity on herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020;369:846–9. 10.1126/science.abc6810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanche S, Lin YT, Xu C, et al. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:1470–7. 10.3201/eid2607.200282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2013;9:1763–73. 10.4161/hv.24657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson H, de Figueiredo A, Karafillakis E, Rawal M. State of vaccine confidence in the EU 2018. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The DELVE Initiative . SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Development & Implementation; Scenarios, Options, Key Decisions, 2020. Available: http://rs-delve.github.io/reports/2020/10/01/covid19-vaccination-report.html

- 7.Schuster M, Duclos P. Who recommendations regarding vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine 2015;33:4155–218.25896381 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazarus J, Ratzan SC, Palayew A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 2020:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Betsch C, Schmid P, Heinemeier D, et al. Beyond confidence: development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS One 2018;13:e0208601. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy . Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33:4161–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guay M, Gosselin V, Petit G, et al. Determinants of vaccine hesitancy in Quebec: a large population-based survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019;15:2527–33. 10.1080/21645515.2019.1603563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nan X, Zhao X, Briones R. Parental cancer beliefs and trust in health information from medical authorities as predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability. J Health Commun 2014;19:100–14. 10.1080/10810730.2013.811319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roozenbeek J, Schneider CR, Dryhurst S, et al. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R Soc Open Sci 2020. a;7:201199. 10.1098/rsos.201199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumgaertner B, Carlisle JE, Justwan F. The influence of political ideology and trust on willingness to vaccinate. PLoS One 2018;13:e0191728. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolsen T, Druckman JN, Cook FL. The influence of partisan motivated Reasoning on public opinion. Polit Behav 2014;36:235–62. 10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jolley D, Douglas KM. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS One 2014;9:e89177. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomljenovic H, Bubic A, Erceg N. It just doesn't feel right - the relevance of emotions and intuition for parental vaccine conspiracy beliefs and vaccination uptake. Psychol Health 2020;35:538–54. 10.1080/08870446.2019.1673894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman D, Waite F, Rosebrock L, et al. Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol Med 2020:1–30. 10.1017/S0033291720001890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salali GD, Uysal MS. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and turkey. Psychol Med 2020:1–3. 10.1017/S0033291720004067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McManus S, D'Ardenne J, Wessely S. Covid conspiracies: misleading evidence can be more damaging than no evidence at all. Psychol Med 2020;21:1–2. 10.1017/S0033291720002184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roozenbeek J, van der Linden S, Nygren T. Prebunking interventions based on the psychological theory of “inoculation” can reduce susceptibility to misinformation across cultures. Harv Kennedy Sch Misinformation Rev 2020. b;1. 10.37016//mr-2020-008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roozenbeek J, van der Linden S. The fake news game: actively inoculating against the risk of misinformation. J Risk Res 2019;22:570–80. 10.1080/13669877.2018.1443491 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Linden S, Maibach E, Cook J, et al. Inoculating against misinformation. Science 2017;358:1141–2. 10.1126/science.aar4533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . Pandemic fatigue: reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19: policy framework for supporting pandemic prevention and management: revised version November 2020 (NO. WHO/EURO: 2020-1573-41324-56242) Regional office for Europe; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michie S, West R, Harvey N. The concept of "fatigue" in tackling covid-19. BMJ 2020;371:m4171. 10.1136/bmj.m4171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jørgensen FJ, Bor A, Petersen MB. Compliance without fear: predictors of protective behavior during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv 2020;19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol 2020;35:775–9. 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong LP, Alias H, Wong P-F, et al. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2020;16:1–11. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1790279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hacquin AS, Altay S, de Araujo E. Sharp rise in vaccine hesitancy in a large and representative sample of the French population: reasons for vaccine hesitancy. PsyArXiv preprints 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner AL, Masters NB, Domek GJ, et al. Comparisons of vaccine Hesitancy across five low- and middle-income countries. Vaccines 2019;7:155. 10.3390/vaccines7040155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertoncello C, Ferro A, Fonzo M, et al. Socioeconomic determinants in vaccine Hesitancy and vaccine refusal in Italy. Vaccines 2020;8:276. 10.3390/vaccines8020276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DL. "Herd immunity": a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:911–6. 10.1093/cid/cir007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson T, Dawes C, Fowler J, et al. Slowing COVID-19 transmission as a social dilemma: lessons for government officials from interdisciplinary research on cooperation. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration 2020;3. 10.30636/jbpa.31.150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegal G, Siegal N, Bonnie RJ. An account of collective actions in public health. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1583–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Callaghan T, Moghtaderi A, Lueck JA, et al. Correlates and disparities of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19. Soc Sci Med 2021;272:113638. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guidry JPD, Laestadius LI, Vraga EK, et al. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control 2021;49:137–42. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann-Böhme S, Sabat I. Now, we have it. will we use it? New results from ECOS on the willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

- 38.Motta M, Sylvester S, Callaghan T. Encouraging COVID-19 vaccine uptake through effective health communication (No. 4d25e) Center for Open Science; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betsch C, Böhm R, Chapman GB. Using behavioral insights to increase vaccination policy effectiveness. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci 2015;2:61–73. 10.1177/2372732215600716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartusevičius H, Bor A, Jørgensen FJ. The psychological burden of the COVID-19 pandemic drives anti-systemic attitudes and political violence. PsyArXiv Preprints 2020. 10.31234/osf.io/ykupt [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WHO . Vaccination and trust: how concerns arise and the role of communication in mitigating crises, 2017. Available: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/329647/Vaccines-and-trust.PDF [Accessed 4 Mar 2021].

- 42.Irving SA, Donahue JG, Shay DK, et al. Evaluation of self-reported and registry-based influenza vaccination status in a Wisconsin cohort. Vaccine 2009;27:6546–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irving SA, Donahue JG, Shay DK, et al. Evaluation of self-reported and registry-based influenza vaccination status in a Wisconsin cohort. Vaccine 2009;27:6546–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith R, Hubers J, Farraye FA, et al. Accuracy of self-reported vaccination status in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2020;113:1–7. 10.1007/s10620-020-06631-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-048172supp001.pdf (3.4MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository at Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/27y3z/.