Abstract

Introduction

Efforts to bridge the know–do gap have paved the way for development of the field of knowledge translation (KT). KT aims to understand how evidence use can best be promoted and supported through different activities. For dissemination activities, infographics are gaining in popularity as a promising KT tool to reach multiple health research users (eg, health practitioners, patients and families, decision-makers). However, to our knowledge, no study has yet mapped the available evidence on this tool using a systematic method. This scoping review will explore the depth and breadth of evidence on infographics use and its effectiveness in improving research uptake (eg, raising awareness, influencing attitudes, increasing knowledge, informing practice and changing behaviour).

Methods and analysis

We will use the scoping review methodological framework first proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), improved by Levac et al, and further refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (2020). The search will be conducted in MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Social Science Abstracts, Library and Information Science Abstracts, Education Resources Information Center, Cairn and Google Scholar. We will also search for relevant literature from the reference lists of the included publications. Two independent reviewers will select the studies. All study designs will be eligible for inclusion, with no date or publication status restrictions. The included studies will have evaluated infographics that disseminate health research evidence and target a non-scientific audience. A data extraction form will be developed and used to extract and chart the data, which will then be synthesised to present a descriptive summary of the results.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not required. To inform the research and KT communities, various dissemination activities will be developed, including user-friendly KT tools (eg, webinars, fact sheets and infographics), open-access publication and presentations at KT events and conferences.

Keywords: social medicine, public health, medical education & training

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This scoping review is the first known to systematically uncover and synthesise literature related to infographics use and effectiveness in improving knowledge uptake in health.

This protocol adheres to Levac et al’s methodological guidelines (2010) built on Arksey and O’Malley’s original framework (2005), as well as to guidelines from the Joanna Briggs Institute (2020).

To reduce bias and errors, this review will include multiple reviewers in all phases of study selection and data extraction.

The scope of this review will be limited, in that only literature published in English and French will be included.

Following accepted scoping review guidelines, this review will not formally assess the quality of the included studies, limiting our ability to assess the strength of existing evidence.

Background

Knowledge translation

Efforts to mobilise vast amounts of research results and evidence-based information have paved the way for development of the knowledge translation (KT) field.1–3 The Canadian Institutes of Health Research defines KT as ‘a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge’ to improve health, health services delivery and the healthcare system.4 KT science aims to understand how evidence use can best be promoted and supported through different KT activities.5 The choice of activities will vary depending on KT objectives (eg, raising awareness, improving action through practice change among professionals, influencing political decision making, mobilising public action), knowledge users’ needs, implementation context and the nature and type of knowledge to be shared.6

In this study, we will focus on dissemination activities that require expertise in plain-language communication and popularisation.1 7 8 The primary goal of dissemination activities is to ‘make new knowledge understandable and accessible so as to effectively reach the groups of actors concerned’ (p. 30).8 Studies have shown that passive dissemination of documents poorly suited to the preferences and characteristics of the target audience is often ineffective.5 8 9 Accordingly, the KT field emphasises the importance of developing dissemination tools that are attractive and adapted to users’ preferences.5 Examples of dissemination tools include summary sheets or infographics, practice guides, newsletters, brochures, leaflets, policy briefs, cartoons, videos, books, reports, plain-language articles, etc.8 10 11 Thanks to the KT movement, research dissemination is no longer limited to peer-reviewed publications and scientific conferences. More innovative and promising tools are now used for knowledge sharing. This project will specifically focus on one of these tools, infographics.12–14

Infographics for KT

Infographics—an abbreviated term for informational graphics—have become increasingly popular in today’s digital age.15–17 In fact, however, data visualisation is not a new phenomenon; maps and illustrations, for instance, have been around for many centuries.18 While no single definition has gained wide acceptance, an infographic is often understood as an eye-catching one-page document that uses striking and engaging visuals to communicate complex evidence-based information in an attractive and easily understandable way.17 19 20 An infographic ‘uses visual cues, illustrations and large typography to display facts in a long, vertical orientation, and are distributed through print media, embedded into websites, and shared on social media’ (p. 2).21 It usually presents information in a logical manner to tell a story.13–15 22

Infographics are ubiquitous and used by many different industries and sectors: business, environment, food, finance, politics, and the healthcare sector, among others.14 Their purpose is to capture users’ attention, help them better understand the information presented, increase their ability to retain and recall the message, and encourage them to act in accordance with the information.23 Infographics are thus gaining ground as a promising research or health information dissemination tool to reach multiple potential knowledge users, such as health practitioners, patients and families, decision-makers and community members. Several research community initiatives have been aimed at producing and distributing infographics in scientific journals or on social media (eg, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Pinterest, Instagram). Moreover, with the recent emergence of user-friendly software for producing infographics, they have become the go-to tool in many contexts, targeting different audiences and using a variety of formats and designs. Thus, research on infographics is essential to better understand their real effectiveness in improving knowledge uptake and to highlight best practices for designing, producing and sharing them. In fact, many empirical studies have explored the use of infographics as an intervention tool for disseminating research results or evidence-based information.20 24–26

Purpose

To our knowledge, no knowledge synthesis has been conducted using a methodology that is both systematic and inclusive of all study designs and evidence sources to map the available evidence on the effectiveness of infographics in supporting dissemination. Although a review of literature was produced related to this topic,27 our review differs in that we use a systematic methodology specific to scoping reviews, include all study designs, and add references published since 2015, to capture the important number of new studies using infographics in recent years. Our overarching goal is to explore the depth and breadth of evidence about the use and effectiveness of infographics as a KT intervention tool to improve knowledge uptake in health (eg, raising awareness, influencing attitudes, increasing knowledge, informing practice, changing behaviour). To produce an evidence synthesis, we will conduct a scoping review. This approach is recommended when the purpose is, for example, to clarify key concepts and definitions in the literature, to identify key characteristics or factors related to a concept, or to examine how research is conducted on a certain topic.28 According to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a scoping review is ‘undertaken when feasibility is a concern—either because the potentially relevant literature is thought to be especially vast and diverse (varying by method, theoretical orientation or discipline) or there is a suspicion that not enough literature exists’ (p. 34).29 As such, a scoping review is useful to identify knowledge gaps that might be addressed in future research.

Methods and analysis

To guide our methodology, we will primarily use the scoping review methodological framework first proposed by Arksey and O’Malley,30 improved by Levac et al 31 and further refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute.32 A scoping review includes six key phases: (1) identifying the research questions; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results and (6) consulting with relevant experts. This protocol is congruent with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), as will be the reporting of the scoping review.33 This scoping review protocol is inspired by and based on previous scoping reviews on similar KT activities and tools.34 35

Stage 1: identifying the research questions

The first stage is to identify research questions related to the purpose of this study. As stated earlier, this scoping review is aimed at determining the scope of evidence on infographics use as a KT intervention tool to disseminate research results or evidence-based information (in health-related sectors) to those who can benefit. Table 1 describes the core elements of the scoping review based on the Population-Concept-Context (PCC) framework.32

Table 1.

PCC framework to illustrate the scope and focus of the review

| Population | Potential knowledge users (non-scientific audience), such as health professionals, decision-makers, patients and families and communities. |

| Concept | An infographic or any shareable tool that uses striking and engaging visuals to communicate complex evidence-based information in a user-friendly way. |

| Context | The use, in health-related sectors, of an infographic intervention to promote and improve knowledge use (eg, raise awareness, influence attitudes, increase knowledge, inform practice, change behaviour) |

PCC, Population-Concept-Context.

We formulated five specific research questions to guide this review. Because the scoping review process can be iterative, we will adopt a reflexive approach and will revise research questions, if needed, as we become more familiar with the body of evidence.

Question 1: what is an infographic?

Given the recent popularity of infographics for KT, and to clarify the nature of this tool, we want to know more about the terms and definitions put forward in the literature to characterise infographics. We will also document the theories or conceptual frameworks most used to study infographics (eg, dual-coding theory, cognitive load theory, theory of planned behaviour, etc.).

Question 2: why are infographics used, for whom and what do they contain?

Next, we will identify the main characteristics of the studied infographics, such as their goals (eg, to raise awareness, influence attitudes, increase knowledge, inform practice, change behaviour), the nature of their content in relation to the information presented, their target audiences, the process used to develop the tool, as well as the visual appearance and format of the infographics. We will use the basic principles of public health infographic design (eg, coherence, colours, alignment, visual hierarchy, use of charts, imagery, headings) as a general framework to extract data related to the visual quality of the infographics in the selected studies.12

Question 3: how is research conducted in the field of health infographics?

We aim to produce a portrait of how empirical studies on infographics are designed. From each of the selected studies, we will extract and analyse data related to its research design (eg, objectives, methods, comparator(s), study procedure), study population, sample size, indicators (outcomes of interest), measurement tools and types of analyses. We will also document how the infographics were delivered in the studies (eg, online vs printed infographic, targeted mail, social media).

Question 4: how effective have infographics been in achieving their goals?

We will document the available evidence on the effectiveness of infographics as a KT intervention in relation to the objectives of the infographics used. The potential of this tool will be discernable to the extent that the studies will have demonstrated their infographics’ effectiveness in relation to outcomes of interest. Finally, we will document the authors’ conclusions regarding perceived barriers and enablers of infographics effectiveness.

Question 5: what are the knowledge gaps and future research needs?

With this last question, we aim to uncover persisting knowledge gaps. To do this, we will describe the main limitations of the selected studies, with a view to discerning any questions that remain unanswered. We hope to make recommendations on needs for research to further advance knowledge.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed by the first author (EMC) with a senior information specialist. It was then circulated to the research team and further refined. Search terms will include keywords and terms related to1: KT (eg, research dissemination, health communication, knowledge transfer) and2 infographic (eg, informational graphic, data visualisation, visual graphic) (see online supplemental appendix 1). To capture as many relevant publications as possible, the list of terms will be iteratively revised after searching the databases. The search strategy will not be limited by study design, year of publication or publication status. Searches will be limited to English and French language publications, due to resource constraints. The search strategy for the MEDLINE database is presented in online supplemental appendix 2. It will be adapted for the other databases and will also be available from the corresponding author on request. The search strategy will be validated using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies checklist.36

bmjopen-2020-046117supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)

Information sources

A systematic search of the published and grey literature will be conducted to identify relevant publications. We will search the following electronic databases from inception onwards: MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, Social Science Abstracts, Library and Information Science Abstracts, Education Resources Information Center and Cairn. These databases were chosen to capture the most comprehensive body of literature possible. The grey literature (eg, reports, conference proceedings, theses, working papers, evaluations) will be searched using Google Scholar and Google Web search engines. Reference lists of key publications will also be handsearched by the review team to capture any paper missed in the electronic searches. The search in the databases will be conducted by our information specialist. Results will be imported into Covidence, a systematic review software programme, and duplicate citations will be removed before the study selection process.

Stage 3: selecting studies

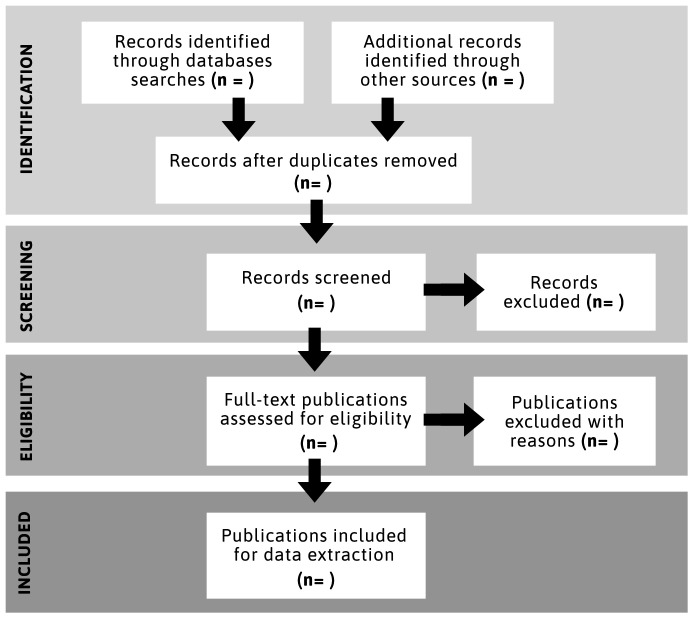

The study selection process will consist of two stages: (1) title and abstract screening and (2) full-text screening by two reviewers, independently. We will use Covidence to manage these two stages of selection. Before beginning the screening, the eligibility criteria (inclusion and exclusion) will be pilot tested on a random sample of publications and modified if low inter-reviewer agreement is observed (eg, a kappa statistic below 60%). If the level of agreement is acceptable, the two reviewers will independently screen the titles and abstracts of all publications retrieved to determine whether they are eligible for full review. The reviewers will meet regularly to discuss uncertainties related to eligibility criteria and to resolve differences in study selection, with a view to ensuring inter-reviewer reliability and reaching consensus. Publications identified as potentially relevant to this scoping review will be retrieved in full text. After completion of the first stage and prior to the full-text review, the two reviewers will meet to revisit the scope of the review and to refine or extend inclusion and exclusion criteria, if necessary. They will also meet regularly during the second stage to discuss and resolve differences. In cases of unresolved decisions related to the inclusion of a study at any stage, a third researcher will adjudicate. A flowchart will be produced using the PRISMA template to report on the selection process (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart detailing identification and selection of studies for inclusion in the review.

Flowchart detailing identification and selection of studies for inclusion in the review

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are based on the PCC framework (see table 1). As such, we will include studies that:

Empirically evaluate an infographic tool (ie, one that includes textual and visual content).

Disseminate research results or other health-related information.

Target a non-scientific audience to improve knowledge use.

All study designs will be eligible for inclusion, with no publication date or status restrictions. Relevant publications that do not meet these inclusion criteria (eg, theoretical paper on information design principles, visual literacy) will be held in a separate folder; if appropriate, they will be used to support data analysis and interpretation.

Exclusion criteria

We will exclude studies that:

Do not focus on health-related issues.

Target children, such as primary school students.

Cconcern one type of graph or charts (eg, bar charts, forest plots, three-dimensional graphs).

Only address interactive data visualisation tools (eg, video, apps, websites).

Uuse health data (eg, personal data contained in electronic health records).

Use infographics as a form of therapy or clinical intervention.

Focus on developing data visualisation skills.

Do not make the evaluated infographic tool available.

Are published in languages other than French and English.

Stage 4: charting the data

After completing the study selection process using Covidence, we will develop a data extraction form using Microsoft Excel to capture the data of interest from the selected studies. Two reviewers will pilot test the form on a random sample of the included studies (10%). They will then meet with the research team to discuss uncertainties and additional potentially relevant information to be included in the form. Data from the remaining studies will be abstracted by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer to ensure correctness and completeness. The data extraction form will be iteratively revised as necessary, to ensure its rigour and ability to capture all relevant data to answer the review questions. Table 2 presents the data to be extracted.

Table 2.

Preliminary data extraction form

| General information |

|

|

| Q1 | What is an infographic? |

|

| Q2 | Why are infographics used, for whom, and what do they contain? |

|

| Q3 | How is research conducted in the field of health infographics? |

|

| Q4 | How effective have infographics been in achieving their goals? |

|

| Q5 | What are the knowledge gaps and future research needs? |

|

Given that the aim of a scoping review is primarily to identify gaps in the evidence base, and consistent with guidance on conducting scoping reviews, we will not conduct a critical appraisal of the selected studies.

Stage 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

The synthesis stage of this review will involve producing a descriptive summary and thematic analysis of the extracted data.31 To ensure rigour, two reviewers will conduct the analysis with input from collaborators during the process. A descriptive summary of the publications’ characteristics (year of publication, country of origin, health topic and type of article) will be presented using frequencies and percentages. We will also prepare descriptive summary tables of all data extracted from included studies that are aligned with our research questions (based on the research question variables presented in table 2. These tables will map key findings regarding infographic definitions and theories used, characteristics of the studied infographics (goals, content, target audience, visual and format, development process), characteristics of the research designs, outcomes of interest used to measure the infographic’s effectiveness, main results, author conclusions and future research needs. We will prepare a qualitative descriptive summary to accompany the tabulated results to describe how they relate to our research questions. Finally, if the extracted data allow it, a more in-depth qualitative analysis will be conducted to discuss or nuance the evidence of effectiveness in light of potential barriers and enablers identified by the authors. We will use the PRISMA-ScR to guide the final reporting of our results.

Stage 6: consultation

While consultation is optional, it can be a relevant and useful stage of a scoping review process, adding methodological rigour and enhancing the validity and usefulness of the review results.31 37 Given that all authors of this protocol are members of a multidisciplinary research team on KT in Canada (RENARD team), we will mobilise our network. We will develop a consultation panel made up of KT researchers, including graduate students and practitioners. All RENARD members have expertise in the KT research field and/or in developing and implementing KT activities to improve knowledge uptake. Input from these informants will be essential to: (1) provide additional references to include in the review; (2) contribute valuable insights into our preliminary results and (3) develop, contextualise, and validate recommendations based on the results of our scoping review (eg, research priorities, criteria for developing effective infographics). The consultation exercise will consist of two focus groups (one on preliminary results and one at the final stage) with approximately 10 experts per group.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and members of the public were not involved in the conception and design of this protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

To our knowledge, this will be the first comprehensive and systematic scoping review on the use and effectiveness of infographics as a KT intervention tool to improve knowledge uptake in the health sector. This review will contribute to both dissemination science and practice. In summary, we will identify gaps in the literature as well as research areas that require systematic review or primary research. This scoping review will be helpful not only to improve research carried out in this field (eg, recommendations for study designs, indicators, measurement tools), but also to offer preliminary guidelines to those planning to use infographics for KT. This review will enable us to describe what an infographic is and what form(s) this tool can take (offering a common terminology and definition in the KT field), to identify in which contexts infographics can be effective and for what purposes, and to identify key principles to consider when developing an infographic for KT.

The present study is exempt from ethics approval because it involves no patient or personal data collection. After completion of the search strategy and data extraction process in the spring, the scoping review results are expected to be ready by August 2021. We will then develop a KT plan to disseminate the results. The main objectives will be to inform the research and KT communities on the state of knowledge on this increasingly popular tool and to raise awareness of its potential usefulness (or non-usefulness) in certain contexts, depending on the conclusions of our review. To achieve these objectives, we will use a combination of user-friendly KT activities such as webinars, fact sheets, summaries, and infographics. They will be widely disseminated via our research team’s website (www.equiperenard.org), newsletters and social media. Results will also be published in an open-access peer-reviewed international journal and presented in relevant KT conferences or events (eg, Canadian Knowledge Mobilization Forum).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Julie Desnoyers, the information specialist affiliated with the RENARD research team on knowledge translation at Université de Montréal, for her assistance in adapting the search strategy used in this scoping review. We also want to thank Équipe RENARD - Fonds de recherche du Québec–Société et Culture (FRQ-SC) and Donna Riley, for editing services.

Footnotes

Twitter: @EstherMcSween

Contributors: EMC, CC, AF, TS and CD conceptualised the study. EMC drafted the protocol. CC, AF, TS and CD critically revised the manuscript. EMC and TS wrote the final draft manuscript and all the authors approved it.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a MAP? J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26:13–24. 10.1002/chp.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McKibbon KA, Lokker C, Wilczynski NL, et al. A cross-sectional study of the number and frequency of terms used to refer to knowledge translation in a body of health literature in 2006: a tower of Babel? Implement Sci 2010;5:16. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Straus S, Tetroe J, Graham ID, eds. Knowledge Translation in Health Care: Moving from Evidence to Practice. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) . Knowledge translation: definition. Available: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29529.html [Accessed Jan 2021].

- 5. Langer L, Tripney J, Gough D. The science of using science: researching the use of research evidence in decision-making. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education, University College London, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Graham ID, Tetroe JM. Getting evidence into policy and practice: perspective of a health research funder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;18:46–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Graham ID, Tetroe J, Gagnon M. Knowledge dissemination: end of grant knowledge translation. In: Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID, eds. Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. 2nd ed. Toronto: John Wiley & Sons, 2013: 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lemire N, Souffez K, Laurendeau M-C. Facilitating a Knowledge Translation Process: Knowledge Review and Facilitation Tool. Montreal, QC: Institut national de santé publique du Québec, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lafreniere D, Menuz V, Hurlimann T. Knowledge dissemination interventions: a literature review. SAGE Open 2013;3. 10.1177/2158244013498242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bennett G, Jessani N, eds. The Knowledge Translation Toolkit—Bridging the Know-Do Gap: A Resource for Researchers. Ottawa: SAGE Publications and International Development Research Centre, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Walter I, Nutley S, Davies H. What works to promote evidence-based practice? A cross-sector review. Evid Policy 2005;1:335–64. 10.1332/1744264054851612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stones C, Gent M. 7 G.R.A.P.H.I.C principles of public health Infographic design. Leeds, UK: University of Leeds, Public Health England, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Balkac M, Ergun E. Role of Infographics in healthcare. Chin Med J 2018;131:2514–7. 10.4103/0366-6999.243569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scott H, Fawkner S, Oliver C, et al. Why healthcare professionals should know a little about infographics. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1104–5. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krum R. Cool Infographics: effective communication with data visualization and design. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lankow J, Ritchie J, Crooks R. Infographics: the power of visual Storytelling. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smiciklas M. The power of Infographics: using pictures to communicate and connect with your Audiences. Indianapolis, IN: Que Publishing, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dunlap JC, Lowenthal PR. Getting graphic about infographics: design lessons learned from popular infographics. J Vis Lit 2016;35:42–59. 10.1080/1051144X.2016.1205832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murray IR, Murray AD, Wordie SJ, et al. Maximising the impact of your work using infographics. Bone Joint Res 2017;6:619–20. 10.1302/2046-3758.611.BJR-2017-0313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin LJ, Turnquist A, Groot B, et al. Exploring the role of infographics for summarizing medical literature. Health Professions Education 2019;5:48–57. 10.1016/j.hpe.2018.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Downing Bice CF. The relative persuasiveness of health infographics [Doctoral dissertation]. Colorado State University, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parrish CP. Exploring visual prevention: developing infographics as effective dervical dancer prevention for African American women [Doctoral dissertation]. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, et al. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:173–90. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buljan I, Malicki M, Wager E, et al. No difference in knowledge obtained from infographic or plain language summary of a Cochrane systematic review: three randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;97:86–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crick K, Hartling L. Preferences of knowledge users for two formats of summarizing results from systematic reviews: infographics and critical appraisals. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140029. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Occa A, Suggs LS. Communicating breast cancer screening with young women: an experimental test of didactic and narrative messages using video and infographics. J Health Commun 2016;21:1–11. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stones C. Infographics research: a literature review of empirical studies on attention, comprehension, recall, adherance and appeal. Available: https://visualisinghealth.com/the-evidence-base/

- 28. Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grimshaw J. A guide to knowledge synthesis. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2010. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41382.html [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide, AU: Joanna Briggs Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hall A, Furlong B, Pike A, et al. Using theatre as an arts-based knowledge translation strategy for health-related information: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032738. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barac R, Stein S, Bruce B, et al. Scoping review of toolkits as a knowledge translation strategy in health. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:121. 10.1186/s12911-014-0121-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:15. 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046117supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)