Abstract

Objective

This study evaluates the priority given to surgical care for children within national health policies, strategies and plans (NHPSPs).

Participants and setting

We reviewed the NHPSPs available in the WHO’s Country Planning Cycle Database. Countries with NHPSPs in languages different from English, Spanish, French or Chinese were excluded. A total of 124 countries met the inclusion criteria.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We searched for child-specific and surgery-specific terms in the NHPSPs’ missions, goals and strategies using three analytic approaches: (1) count of the total number of mentions, (2) count of the number of policies with no mentions and (3) count of the number of policies with five or more mentions. Outcomes were compared across WHO regional and World Bank income-level classifications.

Results

We found that the most frequently mentioned terms were ‘child*’, ‘infant*’ and ‘immuniz*’. The most frequently mentioned surgery term was ‘surg*’. Overall, 45% of NHPSPs discussed surgery and 7% discussed children’s surgery. The majority (93%) of countries did not mention selected essential and cost-effective children’s procedures. When stratified by WHO region and World Bank income level, the West Pacific region led the inclusion of ‘pediatric surgery’ in national health plans, with 17% of its countries mentioning this term. Likewise, low-income countries led the inclusion of surg* and ‘pediatric surgery’, with 63% and 11% of countries mentioning these terms, respectively. In both stratifications, paediatric surgery only equated to less than 1% of the total terms.

Conclusion

The low prevalence of children’s surgical search terms in NHPSPs indicates that the influence of surgical care for this population remains low in the majority of countries. Increased awareness of children’s surgical needs in national health plans might constitute a critical step to scale up surgical system in these countries.

Keywords: health policy, paediatrics, surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses national health plans as strong indicators to evaluate the priority given to paediatric surgical care in 124 countries.

This study used a comprehensive set of proxy indicators to evaluate paediatric surgical care’s impact on national health plans.

Under-representation of high-income countries was a limitation.

Under-representation of countries with health plans written in languages different from English, Spanish, French or Chinese was a limitation.

Introduction

Worldwide an estimated 1.7 billion children and adolescents, predominantly from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), lack access to safe, affordable and timely surgical and anaesthesia care.1 Although surgery has gained increased awareness in the global health agenda in recent years,2–4 surgery for children has received less attention. The burden of surgical disease among children in LMICs is high, with 15%–20% of children in LMICs having surgically amenable conditions.5–11 In addition, the consequences of untreated surgical conditions for children include life-long disabilities and social stigmatisation.5 9 12–25 National investments in surgical care for children are needed to improve children’s health across all regions and income levels.6 7 19 21 26

National health policies, strategies and plans (NHPSPs) are country-level frameworks to design and operate complex health systems and are critical to aligning national strategies, policies and goals for population health.27 NHPSPs bring together stakeholders from across national and subnational levels to develop a health system in line with national political, socioeconomic and historical complexities. NHPSPs are developed through cooperation with the WHO and facilitate the definition and support of national priorities.28 In addition, NHPSPs are key elements for governmental negotiations regarding fiscal space and budget execution.29 Therefore, these documents are excellent proxies to evaluate health priorities at a national level.

Designing country-level plans within an NHPSP framework is recommended to each WHO Member State.30 Of the 194 Member States, 155 countries have updated an NHPSP in the last 5 years.27 NHPSPs are strong measures of each country’s priority to specific health conditions and can help assess if surgical care is incorporated into national plans. A number of countries have recognised a lack of policy-level strategy for improving surgical care. Eight countries have developed specific national surgical, obstetric and anaesthesia plans (NSOAPs) to address the gap in national strategic planning for improved access to surgical care.31–33 Our study expands our understanding of the prioritisation of children’s surgical care in national health policy and strategies. As such, this study aimed to evaluate the level of priority given to surgical care for children within NHPSPs and provide recommendations on aligning these plans with the use of NSOAPs in LMICs.

Methods

Search strategy and data collection

In the context of this manuscript, priority given to paediatric surgical care at a national level was defined as the inclusion of surgery-specific terms for children in the countries’ NHPSPs. Inclusion criteria included publication in English, Spanish, French or Chinese as these are part of the WHO’s six official languages.34 NHPSPs written in Russian and Arabic were not included due to lack of resources to address these languages. From September to October 2019, five investigators searched NHPSPs available in the WHO’s Country Planning Cycle Database.35 The investigators assessed each country’s NHPSPs mission, vision, goals or strategies using 17 search terms related to child health and surgery-specific issues (table 1). The selected terms were translated to Spanish by one of the coauthors, who is a native speaker. The terms in French were translated by the investigators and were validated by a native speaker health professional with expertise in global surgery (LMK) outside of the group of coauthors. The variations of the terms included for Spanish and French did not always have an exact equivalent in English. In addition to variations in language, different variations of the terms were considered during the search. Online supplemental material 1 includes a complete list of the terms in the three languages assessed in this study.

Table 1.

Search terms in English, French and Spanish with frequency of mentions and proportions of policies with no mentions, at least one mention and more than five mentions

| Search terms in English | Search terms in French | Search terms in Spanish | Total mentions, n (%) 3783 (100) |

Policies with no mentions of term, n (%) 124 (100) |

Policies with at least 1 mention of term, n (%) 124 (100) |

Policies with 5 or more mentions of term, n (%) 124 (100) |

| Surgery-specific surg*† | Chirurgi* | Cirug*/ciruj*/quirurgic* | 269 (7.1) | 68 (54.8) | 56 (45.2) | 14 (11.3) |

| Injury | Blessure* | Lesion* | 155 (4.1) | 80 (64.5) | 44 (35.5) | 9 (7.3) |

| Trauma | Traumat* | Trauma* | 102 (2.7) | 88 (71.0) | 36 (29.0) | 6 (5,8) |

| Operation | Operation/intervention | Operacion* | 75 (2.0) | 90 (72.6) | 18 (14.5) | 5 (4.8) |

| Operative | Opératoire | Operativo* | 32 (0.8) | 109 (87.9) | 14 (11.3) | 3 (2.4) |

| Operating | Opératoire/opérant | N/A | 28 (0.7) | 80 (64.5) | 12 (9.7) | 2 (1.6) |

| Open fracture fixation | Fixation de fracture ouverte/ostéosynthèse de fracture ouverte | Fijacion de fractura abierta | 3 (0.1) | 121 (97.6) | 3 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Inguinal hernia | Hernie inguinale | Hernia inguinal | 0 (0.0) | 124 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Pediatric surgery | Chirurgie pédiatrique | Cirujía pediátrica | 9 (0.2)‡ | 115 (92.7) | 9 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Children-specific | ||||||

| Child*§ | Enfant*/naissance | Niñ* | 2142 (56.6) | 16 (12.9) | 108 (87.1) | 85 (68.5) |

| Immuniz*¶ | Immunis*/vaccin* | Vacuna*/inmuniz* | 280 (7.4) | 50 (40.3) | 74 (59.7) | 19 (15.3) |

| Infant | Bébé/infant* | Infant* | 285 (7.5) | 48 (38.7) | 76 (61.3) | 21 (16.9) |

| Malnutrition | Malnutrition | Desnutricion | 242 (6.4) | 67 (54.0) | 57 (46.0) | 17 (13.7) |

| Stunt*†† | Retard de croissance | Retraso en el crecimiento | 67 (1.8) | 89 (71.8) | 35 (28.2) | 4 (3.2) |

| Pedia*‡‡ | Pédiatr* | Pedia* | 44 (1.2) | 101 (81.5) | 23 (18.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Wasting | Dépérissement | Anemia | 33 (0.9) | 106 (85.5) | 18 (14.5) | 1 (0.8) |

| Circumcision | Circoncision/posthectomie | Circuncisión | 17 (0.4) | 115 (92.7) | 9 (7.3) | 0 (0.0) |

For simplicity in the remaining text of this paper, only English terms will be used to describe the statistics revealed by English, French and Spanish search terms.

†Surg* includes surgery, surgeries, surgical, neurosurgery and surgeon.

‡Mentions of ‘pediatric surgery’ were found in NHPSPs from Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo, Chile, Tajikistan, Cambodia, China, Cook Islands and Vietnam.

§Child* includes child, children, childbearing, childbirth and childhood.

¶Immuniz* includes immunization and immunized.

††Stunt* includes stunting.

‡‡Pedia* includes pediatric and pediatrics.

N/A, not available; NHPSPs, national health policies, strategies and plans.

bmjopen-2020-045981supp001.pdf (845.7KB, pdf)

Each NHPSP PDF file was searched using the search function for each term and subsequently counted by frequency. The investigators carefully read the context in which the term appeared and only counted the relevant terms to this study. We selected the search terms based on a review of existing surgical and child health literature and international and national health policy reports. Specifically, search terms were chosen as common terms used in the current global surgery literature.2 7 12 The search terms were grouped into child-specific and surgery-specific to evaluate paediatric surgery priority compared with other well-known priorities in child health and general surgery. We included the terms ‘circumcision’, ‘open fracture fixation’ and ‘inguinal hernia’ as these are the three most commonly performed and cost-effective children’s surgical procedures.21 We followed three different analytic approaches for each search term. First, we counted the total number of mentions of each search term. Second, we counted the number of policies that have no mention of any search term. Third, we counted the number of policies with five or more mentions of each search term. The indicator of at least five mentions was established as a significant number following previous literature that evaluates the inclusion of surgery in African countries’ health plans.36 All data were stored in Microsoft Excel.

Data analysis

The NHPSPs were stratified according to the WHO regional divisions in the African region, region of the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean region, South East Asia region, European region and Western Pacific region to analyse geographical patterns across countries. Likewise, the NHPSPs were stratified according to the World Bank’s Fiscal Year 2019 income classification.37 Descriptive and inference statistics were performed to analyse patterns of inclusion of search terms in NHPSPs across WHO regions and World Bank income levels. We used analysis of variance test and Tukey’s Studentised range test to compare the means of search terms across the mentioned categories. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4.

Patient and public involvement

It was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Results

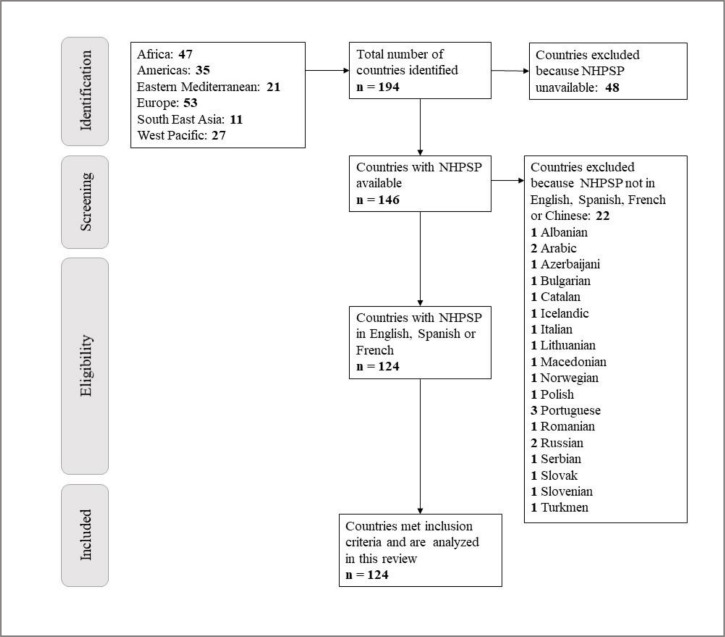

From 194 WHO Member States, 146 countries had NHPSPs available in the WHO’s Country Planning Cycle Database. From the 146 NHPSPs assessed for eligibility, 22 NHPSPs were excluded due to being written in languages different from English, French, Spanish and Chinese. The vast majority of these NHPSPs were written in languages not included as part of the WHO’s six official languages. No NHPSP was written in Chinese. In total, 124 NHPSPs were included in this review (figure 1, online supplemental material 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of data search process. NHPSP, national health policies, strategies and plan.

The term with the most mentions was ‘child*’, with 2142 mentions, followed by the terms ‘infant’ and ‘immuniz*’, with 285 (8%) and 280 (7%) mentions, respectively (table 1). The terms ‘surg*’ and ‘pediatric surgery’ were mentioned at least once in 45% and 7% of NHPSPs, respectively. Sixty-eight (55%) NHPSPs did not mention ‘surg*’. Only 11% of NHPSPs mentioned ‘surg*’ more than five times and no NHPSP mentioned ‘pediatric surgery’ more than five times. In comparison, over 50% of NHPSPs mentioned other common child-specific issues such as ‘immuniz*’ (60% of NHPSPs), ‘infant’ (39%) or ‘malnutrition’ (54%). Nine countries, namely Congo, Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Chile, Tajikistan, Cambodia, China, Cook Islands and Vietnam, mentioned ‘pediatric surgery’ in their NHPSPs. Terms mentioning essential and cost-effective children’s procedures, including ‘circumcision’ (7%), ‘open fracture fixation’ (2%) and ‘inguinal hernia’ (0%), were the least likely to be mentioned. When stratified by WHO region and World Bank income level, the average frequency of inclusion of surg* (4.4 and 4.6) and child* (36.7 and 36.6) was higher for Africa and low-income country (LIC), compared with the other regions and income groups (table 2). Comparisons for ‘pediatric surgery’ and the essential and cost-effective children’s procedures were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of means (ANOVA) of frequency of search terms across WHO regions and World Bank income level

| Search terms | WHO region | World bank income level | ||||||||||

| Africa | Americas | Eastern Mediterranean | Europe | South East Asia | Western Pacific | P value | HIC | UMIC | LMIC | LIC | P value | |

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |||

| Surgery−specific | ||||||||||||

| Surg*† | 4.4 (−1.3) | 0.7 (−0.3) | 1.8 (−1.1) | 0.2 (−0.2) | 2.9 (−1.5) | 1.5 (−0.6) | 0.0198 | 0.5 (−0.2) | 2 (−0.6) | 1.7 (−0.7) | 4.6 (−1.7) | 0.0276 |

| Injury | 3.2 (−0.8) | 0.5 (−0.2) | 0.3 (−0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 1.3 (−1) | 0.3 (−0.2) | 0.0002 | 0.9 (−0.7) | 0.6 (−0.1) | 1.4 (−0.5) | 2.5 (−0.9) | 0.1057 |

| Trauma | 1.9 (−0.5) | 0.6 (−0.2) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.8 (−0.5) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.0009 | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.7 (−0.2) | 1.1 (−0.5) | 1.2 (−0.3) | 0.23 |

| Operation | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0 (0) | 2.7 (−1) | <.0001 | 0 (0) | 1 (−0.4) | 0.9 (−0.6) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.2197 |

| Operative | 0.7 (−0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.3 (−0.2) | 0.026 | 0.2 (−0.2) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.4 (−0.2) | 0.3 (−0.2) | 0.7019 |

| Operating | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0 (0) | 1.1 (−0.3) | <.0001 | 0.3 (−0.2) | 0.4 (−0.2) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.2 (−0.2) | 0.8311 |

| Open fracture fixation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.0869 | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.433 |

| Inguinal hernia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | n/a | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | n/a |

| Pediatric surgery | 0.1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0 (0) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.3611 | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0) | 0.1 (0) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.7154 |

| Children−specific | ||||||||||||

| Child*‡ | 36.7 (−5) | 7.1 (−1.6) | 7.3 (−2) | 7.9 (−2.7) | 12.6 (−3.1) | 10.6 (−2.4) | <.0001 | 6.7 (−1.2) | 10.7 (−2.5) | 17.7 (−3.5) | 36.6 (−6.2) | <.0001 |

| Immuniz*§ | 3.4 (−0.8) | 1.1 (−0.2) | 1.2 (−0.3) | 1.6 (−0.8) | 3.6 (−1.6) | 2.1 (−0.7) | 0.0984 | 1.3 (−0.4) | 1.4 (−0.4) | 2.5 (−0.6) | 4 (−1.1) | 0.0164 |

| Infant | 3.3 (−0.8) | 1.5 (−0.4) | 1.9 (−0.8) | 1.5 (−0.6) | 2.5 (−1.5) | 2.2 (−0.4) | 0.2736 | 1.8 (−0.5) | 2.2 (−0.6) | 2 (−0.5) | 3.3 (−0.7) | 0.394 |

| Malnutrition | 4.6 (−0.9) | 0.8 (−0.3) | 1.3 (−0.5) | 0.4 (−0.3) | 1.1 (−0.5) | 0.7 (−0.3) | <.0001 | 0.3 (−0.3) | 0.9 (−0.2) | 1.4 (−0.3) | 5.8 (−1.2) | <.0001 |

| Stunt*¶ | 1.3 (−0.3) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.3 (−0.1) | 0 (0) | 0.6 (−0.3) | 0.3 (−0.1) | 0.0002 | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.7 (−0.2) | 1.2 (−0.4) | 0.0026 |

| Pedia*†† | 0.4 (−0.2) | 0.5 (−0.2) | 0.2 (−0.2) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.3 (−0.3) | 0.5 (−0.3) | 0.76 | 0.3 (−0.2) | 0.5 (−0.2) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.5 (−0.2) | 0.648 |

| Wasting | 0.4 (−0.2) | 0.5 (−0.2) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.4 (−0.2) | 0 (0) | 0.3519 | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.3 (−0.1) | 0.1 (−0.1) | 0.6 (−0.3) | 0.1525 |

| Circumcision | 0.4 (−0.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.0219 | 0 (0) | 0.2 (−0.1) | 0.1 (0) | 0.3 (−0.2) | 0.2382 |

Statistically significant different means are in bold (Tukey’s Studentised range).

For simplicity in the remaining text of this paper, only English terms will be used to describe the statistics revealed by English, French and Spanish search terms.

†Surg* includes surgery, surgeries, surgical, neurosurgery, and surgeon.

‡Child* includes child, children, childbearing, childbirth, and childhood.

§Immuniz* includes immunization, and immunized.

¶Stunt* includes stunting.

††Pedia* includes pediatric and pediatrics.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; HIC, high-income country; LIC, low-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country; N/A, not available; UMIC, upper-middle-income country.

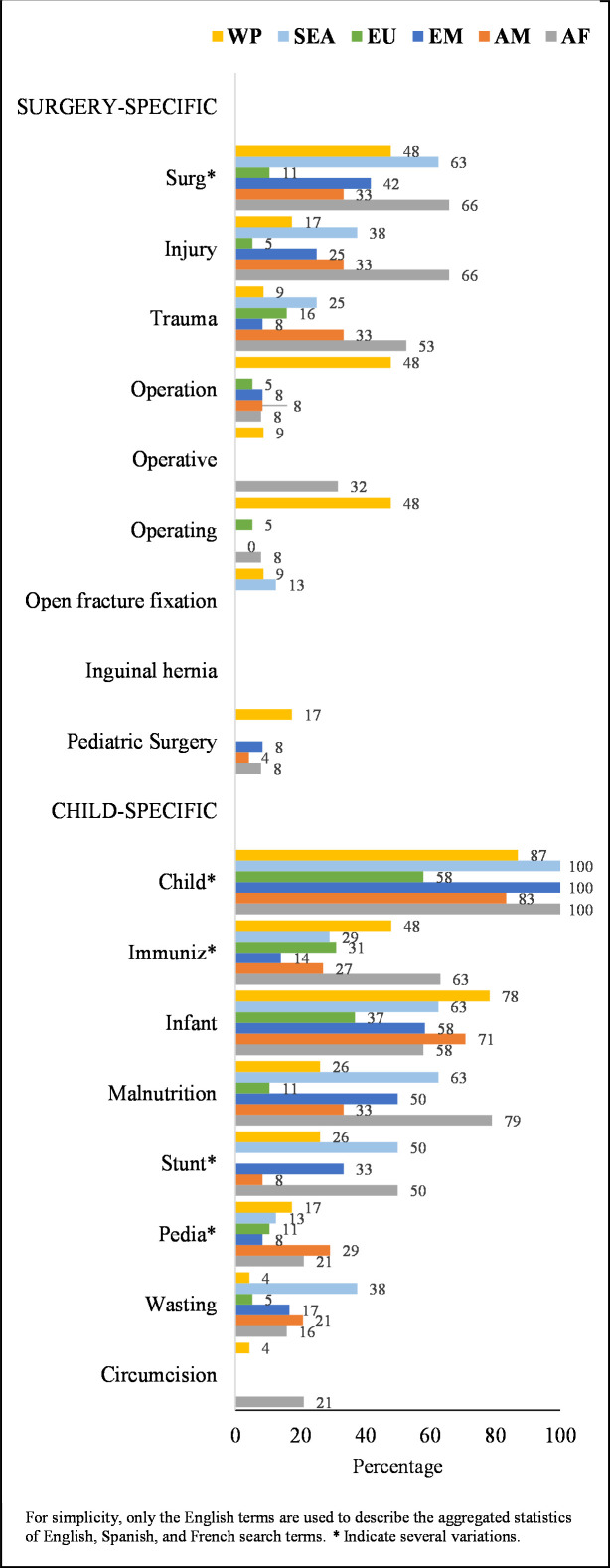

All (100%) countries from Africa, East Mediterranean and South East Asia regions mentioned child* at least once and over 60% of countries from South East Asia and Africa mentioned surg*. In contrast, only 17% of countries from the West Pacific Region (the highest percentage among all regions) mentioned ‘pediatric surgery’ (figure 2). The Eastern Mediterranean region and the South East Asia region had no mentions of ‘pediatric surgery’ in their NHPSPs. The cost-effective paediatric surgical procedures were only mentioned in the West Pacific, South East Asia and Africa regions. The West Pacific region (44%) and the African region (33%) had the most frequent mentions of ‘pediatric surgery’ and combined make up to 77% of mentions for this search term. However, when compared with other terms, ‘pediatric surgery’ only equated to 0.8% and 0.1% of the total search term mentions, respectively (online supplemental materials 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Percentage of countries from each WHO region that mention the search terms in their national health policies, strategies and plans at least once. Weighted per cent was used to facilitate comparison across regions. AF, African region; AM, Americas; EM, Eastern Mediterranean region; EU, European region; SEA, South East Asia region; WP, Western Pacific region.

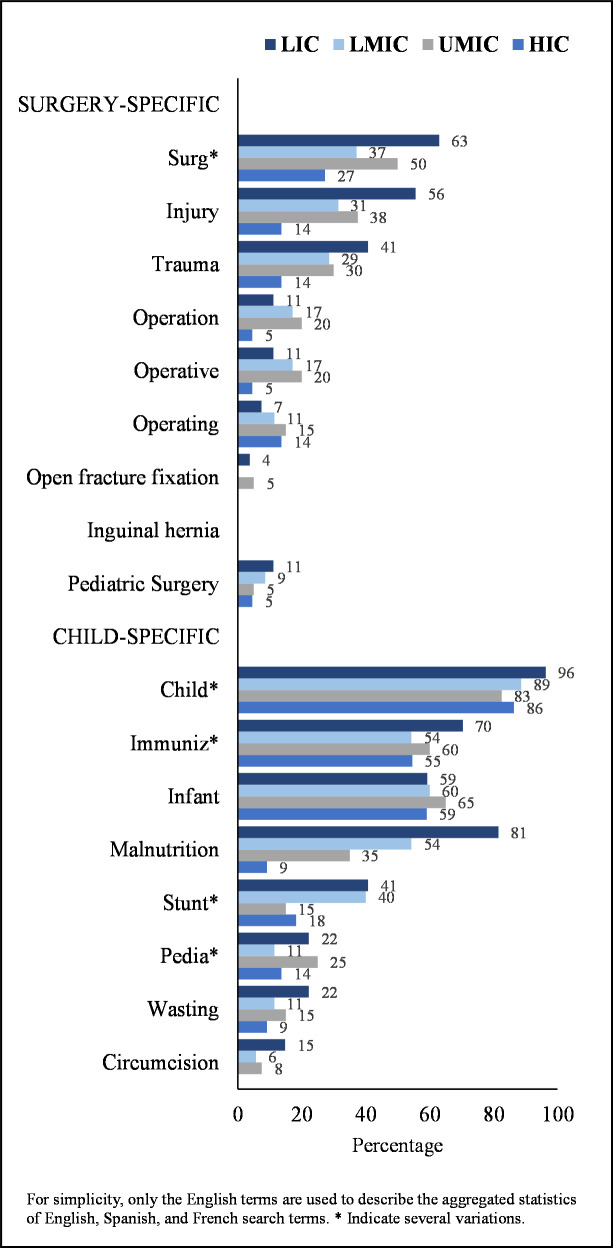

Over 80% of countries from each income level group mentioned child* in their national health plans. LICs lead the inclusion of surg* and ‘pediatric surgery’, with 63% and 11% of countries mentioning these terms, respectively (figure 3). The cost-effective paediatric surgical procedures were not mentioned by high-income countries (HICs) and under 15% of countries from the other regions mentioned these terms. LICs had the highest frequency of mentions for ‘surg*’ (45%), which equates to 8% of the total mentions for this economic group. NHPSPs from LICs (33%) and LMICs (33%) concentrated the majority of mentions for ‘pediatric surgery’ and combined make up to 66% of mentions for this term. However, when compared with other terms, ‘pediatric surgery’ only equates to 0.2% and 0.3% of the total search term mentions, respectively (online supplemental material 5).

Figure 3.

Percentage of countries from each World Bank income level that mention the search terms in their national health policies, strategies and plans at least once. Weighted per cent was used to facilitate comparison across income levels. HIC, high-income country; LIC, low-income country; LMIC, low-income and middle-income country; UMIC, upper-middle-income country.

Discussion

Inclusion of children’s surgical care coverage in NHPSPs and NSOAPs is improving the health of children and alignment of surgical care with Universal Health Coverage (UHC) frameworks.38–40 Our study provides evidence that the financing of surgical care for children and penetration of UHC policies for surgical coverage for children in NHPSPs are quite limited, with under 18% and 15% of countries addressing paediatric surgical care across income levels and regions. Furthermore, the majority (93%) of countries did not mention selected essential and cost-effective children’s procedures. Given that children’s surgical care requires a unique set of workforce and infrastructure, this gap in the inclusion of surgical needs for children is an opportunity to define children’s surgical care as a part of national essential benefit packages.

Surgical care was more frequently discussed within NHPSPs in the African region in comparison with other regions. Fewer countries from the European region addressed surgical-specific and paediatric surgery terms. This finding could reflect the number of countries, particularly in the WHO African region, that have created NSOAPs.32 More countries from the Western Pacific region mentioned ‘pediatric surgery’, despite a lack of NSOAPs in that region. Furthermore, the Western Pacific region used language including ‘operation’ more frequently than other regions, a finding that could indicate a lack of international consensus on NSOAP language. The Western Pacific region has had a long-standing collaborative partnership in surgical training and provision of specialist surgical services in the region with the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. Over the first 15 years of the partnership, operations done by trainees increased from 10% to 77%, and nurse anaesthetists were trained and deployed in each hospital.41 In addition, collaborations between nations have recently resulted in 13 of the 14 countries collectively measuring the first four Lancet Commission global surgery indicators.42 This type of collaborative partnerships could serve as key examples of integrating surgical care on national levels.

When stratified by income level, LICs were most likely to mention surgery-specific search terms in addition to children-specific search terms compared with HICs, a finding consistent with the increasing number of LICs that are developing NSOAPs. Overall, however, the low frequency of children-specific surgical procedures could be reflective of a lack of global consensus on defining essential surgical procedures for children. This finding suggests an opportunity to define surgical procedures for children such that future NHPSPs and NSOAPs can target prevalent surgical conditions and cost-effective care to improve the health of children in national UHC goals. This has partially been done with the latest edition of the Disease Control Priorities 3, mainly for congenital conditions.38

Although surgical conditions are a high burden for children in many LMICs, a list of cost-effective, essential surgical procedures for children still needs to be defined for the inclusion of children’s surgical care in NHPSPs and NSOAPs. Furthermore, because children’s surgical care is subspecialised in nature, organised referral systems, specialised centres and specialised workforce are required simultaneously for optimal outcomes. The Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery (GICS), a collaborative organisation with over 150 providers worldwide, developed guidelines in the Optimal Resources for Children’s Surgery (OReCS) document to support the provision of care at every healthcare level based on infrastructure, service delivery, training and research.21 26 43 44 The OReCS document outlines a multifaceted strategy for integrating procedure-specific surgical care for children into NSOAPs. The OReCS document serves as a specific guide to scale up surgical care in an organised manner by addressing all levels of healthcare in the country, including referral systems and workforce expansion. The utility of the OReCS document in conjunction with national child health policy plans, NHPSPs and NSOAPs could serve as a starting point for integrating child-specific surgical care into existing or developing national health plans.

Nigeria can serve as an example of successfully integrating the OReCS document with NSOAPs and NHPSPs through the lens of UHC (figure 4). Nigeria’s robust development of a national surgical plan is integrated into the national health plan and includes the provision and strengthening of children and adolescents’ surgical care within the existing healthcare systems. This model highlights the utility of using national plans that can address multiple sectors of surgical delivery in a coordinated manner. Going forward, the success of Nigeria’s integration of children’s surgical care within national health plans can serve as a template for other countries to follow.

Figure 4.

Example in Nigeria: inclusion of children’s surgical care within national health plans.

Surgically amenable conditions will increasingly impact children around the world, as over a quarter of the global population are under 15 years of age and approximately 50% of the population in LICs are under the age of 15.39 40 Inclusion of children’s surgical policies in NHPSPs and WHO regional health plans might constitute a critical step in the efforts to meet the United Nation’s Strategic Development Goals 3 of achieving 80% coverage of essential healthcare services while protecting 100% of patients from impoverishing and catastrophic health expenditures.45

Limitations

Our study limitations include being unable to locate NHPSPs for all countries in the WHO’s Country Planning Cycle Database. Of the 48 countries not included, 73% were from HICs or upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), which may have biased the results as HICs and UMICs were less likely to report surgical-specific and child-specific search terms than LICs or LMICs. Additionally, our study excluded 22 NHPSPs written in languages other than English, Spanish and French. Of the 22 studies, 91% were from HICs or UMICs. We also used limited search terms to assess the inclusion of children’s surgery in the NHPSP reviews, potentially underestimating the number of plans with surgical care embedded. Although this occurrence may be small as we searched for the major terms of surg* and ped*, there is a possibility of missing key terms. Deeper analyses of NHPSPs through additional search terms and other qualitative approaches may provide a more robust and thorough search through the plans. Finally, NHPSPs represent only one part of UHC schemes. Further study on the national budget and health policy literature and documents is important in defining the penetration of UHC schemes on surgical care provision for children at national health system levels.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that paediatric surgical care has a very low impact on the majority of national health plans. NHPSPs are developed to guide national health priorities. Therefore, we have a golden opportunity to incorporate children’s surgical care as part of these health plans and, in this way, contribute to the scale-up of surgical care systems for children at a national and global scale. From our findings, we propose the following key policy recommendations for the Member States:

Countries should use the GICS OReCS guidelines to assess the current state of surgical care for children across multiple health system perspectives and facilitate collaboration with a broad range of health policy and children’s surgery stakeholders.

Individual countries should define an essential package of children’s surgical care across all specialties based on country-level surgical needs for children using language consistent across the Member States.

The inclusion of children’s surgical needs in WHO NHPSPs and NSOAPs should be prioritised in order to address country-level surgical needs for children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery (GICS) and the Center for Spatial Research at Baylor University for their support of this work. GICS (www.globalchildrenssurgery.org) is a network of children’s surgical and anaesthesia providers from low-income, middle-income and high-income countries collaborating for the purpose of improving the quality of surgical care for children globally. We also thank Dr Luc Malemo Kalisya for his valuable contribution to the validation of the search terms and their variations in French.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ptrucheMD

KL and CFC-C contributed equally.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published. Middle initial has been added for Dr. John G Meara.

Contributors: Conceptualisation: ERS, HER, KL, CFC-C, YL, JR, NT, RG. Methodology: ERS, HER, KL, CFC-C, YL, JR, NT, RG. Data collection: CFC-C, YL, JR, NT, RG. Formal analysis and investigation: CFC-C. Writing-original draft preparation: ERS, KL, CFC-C, YL. Writing-review and editing: ERS, KL, CFC-C, PT, EA, SB, LS, JM, HER. Supervision: ERS.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data for this study are available in a public, open access repository.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants. Therefore, research approval was not applicable.

References

- 1.Mullapudi B, Grabski D, Ameh E, et al. Estimates of number of children and adolescents without access to surgical care. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97:254–8. 10.2471/BLT.18.216028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet 2015;386:569–624. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botman M, Meester RJ, Voorhoeve R, et al. The Amsterdam Declaration on essential surgical care. World J Surg 2015;39:1335–40. 10.1007/s00268-015-3057-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price R, Makasa E, Hollands M. World Health Assembly Resolution WHA68.15: "Strengthening Emergency and Essential Surgical Care and Anesthesia as a Component of Universal Health Coverage"—Addressing the Public Health Gaps Arising from Lack of Safe, Affordable and Accessible Surgical and Anesthetic Services. World J Surg 2015;39:2115–25. 10.1007/s00268-015-3153-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith ER, Vissoci JRN, Rocha TAH, et al. Geospatial analysis of unmet pediatric surgical need in Uganda. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1691–8. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Concepcion T, Mohamed M, Dahir S, et al. Prevalence of pediatric surgical conditions across Somaliland. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e186857. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler EK, Tran TM, Nagarajan N, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric surgical needs in low-income countries. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170968. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler EK, Tran TM, Fuller AT, et al. Quantifying the pediatric surgical need in Uganda: results of a nationwide cross-sectional, household survey. Pediatr Surg Int 2016;32:1075–85. 10.1007/s00383-016-3957-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bearden A, Fuller AT, Butler EK, et al. Rural and urban differences in treatment status among children with surgical conditions in Uganda. PLoS One 2018;13:e0205132. 10.1371/journal.pone.0205132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdul-Mumin A, Anyomih TTK, Owusu SA, et al. Burden of neonatal surgical conditions in northern Ghana. World J Surg 2020;44:3–11. 10.1007/s00268-019-05210-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelgadir J, Smith ER, Punchak M, et al. Epidemiology and characteristics of neurosurgical conditions at Mbarara regional referral hospital. World Neurosurg 2017;102:526–32. 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bickler SW, Rode H. Surgical services for children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 2002;80:829. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagarajan N, Gupta S, Shresthra S, et al. Unmet surgical needs in children: a household survey in Nepal. Pediatr Surg Int 2015;31:389–95. 10.1007/s00383-015-3684-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yousef Y, Lee A, Ayele F, et al. Delayed access to care and unmet burden of pediatric surgical disease in resource-constrained African countries. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:845–53. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bickler SW, Kyambi J, Rode H. Pediatric surgery in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Surg Int 2001;17:442–7. 10.1007/s003830000516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okoye MT, Ameh EA, Kushner AL, et al. A pilot survey of pediatric surgical capacity in West Africa. World J Surg 2015;39:669–76. 10.1007/s00268-014-2868-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kushner AL, Groen RS, Kamara TB, et al. Assessment of pediatric surgery capacity at government hospitals in Sierra Leone. World J Surg 2012;36:2554–8. 10.1007/s00268-012-1737-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lalchandani P, Dunn JCY. Global comparison of pediatric surgery workforce and training. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50:1180–3. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith ER, Concepcion TL, Mohamed M, et al. The contribution of pediatric surgery to poverty trajectories in Somaliland. PLoS One 2019;14:e0219974. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith ER, van de Water BJ, Martin A, et al. Availability of post-hospital services supporting community reintegration for children with identified surgical need in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:727. 10.1186/s12913-018-3510-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saxton AT, Poenaru D, Ozgediz D, et al. Economic analysis of children's surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165480. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuller AT, Haglund MM, Lim S, et al. Pediatric neurosurgical outcomes following a neurosurgery health system intervention at Mulago national referral hospital in Uganda. World Neurosurg 2016;95:309–14. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Concepcion TL, Smith ER, Mohamed M, et al. Provision of surgical care for children across Somaliland: challenges and policy guidance. World J Surg 2019;43:2934. 10.1007/s00268-019-05079-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Concepcion TL, Dahir S, Mohamed M, et al. Barriers to surgical care among children in Somaliland: an application of the three delays framework. World J Surg 2020;44:1712–8. 10.1007/s00268-020-05414-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith ER, Concepcion TL, Shrime M, et al. Waiting too long: the contribution of delayed surgical access to pediatric disease burden in Somaliland. World J Surg 2020;44:656–64. 10.1007/s00268-019-05239-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith ER, Concepcion TL, Niemeier KJ, et al. Is global pediatric surgery a good investment? World J Surg 2019;43:1450–5. 10.1007/s00268-018-4867-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . Supporting National health policies, strategies, plans, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/activities/supporting-national-health-policies-strategies-plans [Accessed 14 Feb 2020].

- 28.United Nations . Sustainable development goals, 2019. Available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 [Accessed 14 Oct 2019].

- 29.World Health Organization Schmets G, Kadandale S, Porignon D, eds. Strategizing National health in the 21st century: a Handbook, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization . A framework for national health policies, strategies and plans; 2010.

- 31.Citron I, Jumbam D, Dahm J, et al. Towards equitable surgical systems: development and outcomes of a national surgical, obstetric and anaesthesia plan in Tanzania. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001282. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truché P, Shoman H, Reddy CL, et al. Globalization of national surgical, obstetric and anesthesia plans: the critical link between health policy and action in global surgery. Global Health 2020;16:1–8. 10.1186/s12992-019-0531-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters AW, Roa L, Rwamasirabo E, et al. National surgical, obstetric, and anesthesia plans supporting the vision of universal health coverage. Glob Health Sci Pract 2020;8:3–9. 10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization . Multilingualism and WHO, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/multilingualism [Accessed 27 Aug 2020].

- 35.World Health Organization . Country planning cycle database, 2019. Available: http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/planning-cycle/afg [Accessed 27 Aug 2019].

- 36.Citron I, Chokotho L, Lavy C. Prioritisation of surgery in the National health strategic plans of Africa: a systematic review. Lancet 2015;385 Suppl 2:779–83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60848-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Bank . New world bank GDP and poverty estimates for Somaliland, 2014. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2014/01/29/new-world-bank-gdp-and-poverty-estimates-for-somaliland [Accessed 16 Jul 2019].

- 38.Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A. Disease Control Priorities. In: Essential surgery. Volume 1. Third Edition. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Population Reference Bureau . 2018 world population data sheet with focus on changing age structures, 2020. Available: https://www.prb.org/2018-world-population-data-sheet-with-focus-on-changing-age-structures/ [Accessed 14 Feb 2020].

- 40.Smith ER, Concepcion T, Lim S, et al. Disability weights for pediatric surgical procedures: a systematic review and analysis. World J Surg 2018;42:3021–34. 10.1007/s00268-018-4537-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guest GD, Scott DF, Xavier JP, et al. Surgical capacity building in Timor-Leste: a review of the first 15 years of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons-led Australian Aid programme. ANZ J Surg 2017;87:436–40. 10.1111/ans.13768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guest GD, McLeod E, Perry WRG, et al. Collecting data for global surgical indicators: a collaborative approach in the Pacific region. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000376–e76. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery . Optimal resources for children's surgical care: Executive summary. World J Surg 2019;43:978–80. 10.1007/s00268-018-04888-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Global Initiative for Children’s Surgery . Global initiative for children's surgery: a model of global collaboration to advance the surgical care of children. World J Surg 2019;43:1416–25. 10.1007/s00268-018-04887-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boerma T, Eozenou P, Evans D, et al. Monitoring progress towards universal health coverage at country and global levels. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001731. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-045981supp001.pdf (845.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. All data for this study are available in a public, open access repository.