Abstract

Objective:

To assess the potential for crowdsourcing to complement and extend community advisory board (CAB) feedback on HIV clinical trials. Crowdsourcing involves community members attempting to solve a problem and then sharing solutions.

Methods:

CAB and crowdsourced approaches were implemented in the context of a phase 1 HIV antibody trial to collect feedback on informed consent, participation experiences, and fairness. CAB engagement was conducted through group discussions with members of an HIV CAB. Crowdsourcing involved open events intended to engage the local community, including interactive video modules, animated vignettes, and a creative idea contest. Open coding and analysis of emergent themes were conducted to compare CAB and crowdsourced feedback.

Results:

The crowdsourcing activities engaged 61 people across the three events; 9 people engaged in CAB feedback. Compared to CAB participants, crowdsourcing participants had lower levels of education and income, and higher levels of disability and unemployment. Overlap in CAB and crowdsourced feedback included recommendations for enhancing communication and additional support for trial participants. Crowdsourcing provided more detailed feedback on the impact of positive experiences and socio-economic factors on trial participation. CAB feedback included greater emphasis on institutional regulations and tailoring trial procedures. Crowdsourced feedback emphasized alternative methods for learning about trials and concerns with potential risks of trial participation.

Conclusions:

Conducting crowdsourcing in addition to CAB engagement can yield a broader range of stakeholder feedback to inform the design and conduct of HIV clinical trials.

Keywords: Community engagement, HIV clinical trials, community stakeholders, community advisory boards, crowdsourcing

Introduction

Community engagement is widely recognized as an essential component of HIV clinical trials. We define community engagement as interactive activities used to gain insights from communities affected by HIV on clinical trial design, recruitment, implementation, and dissemination of research findings [1]. Engaging community stakeholders can help researchers address community concerns more effectively and ensure that trial procedures are acceptable to community members [2, 3]. This is particularly important in HIV clinical trials, as failure to sufficiently engage with community members has previously led to mistrust of clinical research [4] and trial shutdown [5–7].

One of the most common community engagement strategies for HIV trials is community advisory boards (CABs) [8]. A CAB is composed of individuals acting as representatives of the wider community where a trial is conducted, who provide independent feedback to trial research teams and disseminate information about trials to the wider community [1]. The CAB model has been extensively studied for its potential to increase community buy-in, recruitment and successful trial implementation [9, 10]. However, CAB engagement is one of many methods for obtaining community input on HIV clinical trials [8]. The UNAIDS/AVAC Good Participatory Practice (GPP) guidelines note the important role of CABs in providing feedback, but also encourage the use of other advisory mechanisms to broaden the range of stakeholder input [1].

There have been few studies examining whether implementing additional engagement strategies alongside CAB feedback can capture broader perspectives from community stakeholders. It is also unclear whether and how the simultaneous use of additional community engagement strategies results in different kinds of community feedback to inform HIV trials. There is some evidence to suggest that the type of community engagement mechanism used can make a difference for trial planning, conduct and communication [11]. To advance our understanding of extended community feedback for HIV clinical trials, we conducted a pilot study to obtain feedback on the design of a phase 1 HIV antibody clinical trial using two different engagement strategies: CAB feedback and crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing refers to a group of individuals solving a problem and then sharing solutions with the public[12]. The goal of this study was to compare feedback from both engagement strategies in order to determine the extent to which crowdsourcing can serve to complement and extend the traditional CAB approach for HIV clinical trials.

Methods

Our pilot study was called the Acceptability of Combined Community Engagement Strategies Study (ACCESS). The engagement activities of ACCESS were conducted alongside a phase 1 clinical trial at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, called the VOR-07 study [13]. This trial examined the safety and effectiveness of combining an HIV antibody (VRC07-523LS) with the latency reversal agent (LRA), vorinostat. LRAs are used to reactivate latent HIV virus in people living with HIV. ACCESS was designed with the knowledge, approval and collaboration of the VOR-07 clinical team, albeit as a separate study from the trial’s own procedures. ACCESS is thus an example of a parallel social science study [14] that could help inform future HIV clinical trials. ACCESS was not designed to directly impact VOR-07 activities (i.e. protocol revision, recruitment/retention, dissemination).

Data collection

ACCESS collected qualitative data using two types of engagement methods. Our first engagement method, CAB feedback, involved the participation of a pre-existing university-affiliated HIV CAB with extensive experience in providing feedback on locally-conducted HIV clinical trials. The second engagement method in ACCESS was crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing has been used to inform HIV public health research, including the design of HIV testing campaigns [15, 16] and to investigate the meaning of HIV cure among community members [17, 18]. However, crowdsourcing is not currently a widely used engagement strategy for HIV clinical trials [8]. This study breaks new ground by applying a crowdsourcing approach to an HIV clinical trial, creating the opportunity for anyone age 18 years or older to participate in the community feedback process. No background knowledge of HIV clinical trials was required, nor was participation contingent upon HIV serostatus. We did not limit participation only to persons living with HIV in order to avoid the need for participants to self-identify their HIV status, thereby encouraging community participation around a highly stigmatized subject. Additionally, this opened participation to a broad array of individuals in the local community who have a stake in the design and conduct of HIV clinical trials despite not living with HIV themselves or being potential trial participants – for example, family of potential trial participants, HIV treatment advocates, members of community-based HIV organizations, and residents of the area where the trial is being conducted could all be considered stakeholders in HIV clinical trials [1].

Both CAB and crowdsourcing strategies were operationalized into a series of parallel engagement activities to obtain participants’ feedback on three aspects of the design and conduct of the VOR-07 study: 1) the informed consent process, 2) the experience of participating in the clinical trial, and 3) concepts of fairness and reciprocity in HIV clinical trials. These three aspects were chosen for their correspondence to GPP guidelines recommending community input at each stage of a trial, from development of consent documents to post-trial processes [1].

A summary of the CAB and crowdsourcing engagement activities used in ACCESS is provided in Table 1. CAB participants were recruited by contacting the CAB’s coordinator and delivering a brief presentation to CAB members on the purpose and activities of ACCESS. Once CAB members agreed to participate, CAB engagement activities were then integrated into our participating CAB’s regular meetings, taking the form of interviewer-guided group discussions led by one member of our research team (SD) who had no prior relationship with the CAB. A group discussion format was chosen to mimic as closely as possible the usual approach that clinical trial researchers take in obtaining CAB feedback [1]. Three discussions of approximately 1 hour each were held with the CAB in total using semi-structured interview guides. All discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and field notes were recorded at each discussion. We also administered a brief survey of CAB participants’ demographic information. As the CAB receives funding for its meetings, CAB members were not offered additional incentives to participate in ACCESS.

Table 1:

Summary of methods used for CAB and crowdsourcing engagement

| Engagement Topics | CAB Engagement Activities | Crowdsourcing Engagement Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Activity 1: Feedback on VOR-07 informed consent |

|

|

| Activity 2: Feedback on participation in the VOR-07 trial |

|

|

| Activity 3: Ideas for how to enhance fairness and reciprocity in the VOR-07 trial |

|

|

Crowdsourcing engagement activities involved a series of three open community events using a combination of in-person group discussions led by an interviewer from our team (SD) and an idea contest to obtain crowdsourced feedback. Recruitment for crowdsourcing activities involved advertising through posts on our research group’s social media accounts (Facebook and Twitter), physical flyers placed at a local infectious disease clinic and clinical research center, and via local HIV CABs and individual HIV community engagement advocates known to our research group (who were then asked to distribute event information among their community networks). Additional details on the design of our crowdsourcing activities are reported in-depth elsewhere [19].

All engagement activities (both CAB and crowdsourcing) were conducted from July 2018 – February 2019. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and we obtained written informed consent from all participants.

Data analysis

Our analysis was guided by a community-based participatory research (CBPR) framework, an approach to research that seeks to address disparities in knowledge production by involving community members as the experts of their own experiences, local contexts, and ideas for challenging inequitable relations.[20] All transcripts, field notes, and contest submissions were coded using the qualitative analysis software MAXQDA. We used a process of open coding to identify emergent themes in the data [21]. Two study team members generated an initial list of potential parent codes. One coder then used this list to code all transcripts and contest submissions line-by-line, refining codes and developing sub-codes throughout this process. The first draft of a code book resulting from this process was then discussed with a secondary coder and further refined; this secondary coder then used the revised code book to subsequently code all field notes. The final codebook was comprised of 15 parent codes and 70 sub-codes. All coded data were then analyzed using the constant comparative method to identify similarities and divergences in the feedback obtained from both CAB and crowdsourcing, comparing which codes emerged most strongly in each engagement method and how the context of codes varied between CAB and crowdsourced feedback [22]. Demographic survey data were compiled for descriptive quantitative analysis.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

All members of the CAB we approached to join ACCESS agreed to participate, resulting in a total of nine CAB participants. Crowdsourcing activities engaged 61 participants in total: activities 1 and 2 were attended by 38 participants, and we received 43 submissions to the idea contest for crowdsourcing activity 3 from 23 participants (multiple submissions were allowed), including 27 in-person submissions by 19 participants and 16 online submissions by 4 participants. Table 2 presents participant demographic information.

Table 2:

Demographic Survey of ACCESS Participants

| Demographic Categories | Community Advisory Board Participants (N = 9) | Crowdsourcing Activity 1 (Informed Consent) (N = 20) | Crowdsourcing Activity 2 (Trial Participation) (N = 18) | Crowdsourcing Activity 3 (Idea Contest) (N = 23)1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Woman | 3 | 33% | 11 | 55% | 7 | 39% | 16 | 70% |

| Man | 6 | 67% | 8 | 40% | 5 | 28% | 7 | 30% | |

| Another identity | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |

| Data missing | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5% | 6 | 33% | 0 | 0% | |

| Race/Ethnicity2 | Black/African American | 6 | 67% | 20 | 100% | 13 | 72% | 16 | 70% |

| White/Caucasian | 2 | 22% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 22% | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 11% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 4% | |

| Native American/American Indian | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5% | 1 | 6% | 0 | 0% | |

| Another identity | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 6% | 1 | 4% | |

| Data missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 28% | 0 | 0% | |

| Highest Level of Education | Did not complete high school | 0 | 0% | 3 | 15% | 1 | 6% | ||

| GED | 0 | 0% | 2 | 10% | 1 | 6% | |||

| High school diploma | 0 | 0% | 5 | 25% | 5 | 28% | |||

| Some college, no degree | 3 | 33% | 4 | 20% | 1 | 6% | |||

| Associate’s degree | 0 | 0% | 2 | 10% | 3 | 17% | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 0 | 0% | 4 | 20% | 2 | 11% | |||

| Master’s degree | 6 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Data missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 28% | |||

| Household Income | Less than $10,000 | 0 | 0% | 10 | 50% | 8 | 44% | ||

| $10,000 to $29,999 | 0 | 0% | 5 | 25% | 3 | 17% | |||

| $30,000 to $39,999 | 2 | 22% | 1 | 5% | 1 | 6% | |||

| $40,000 to $49,999 | 2 | 22% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 5 | 56% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| $100,000 or more | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Data missing | 0 | 0% | 4 | 20% | 6 | 33% | |||

| Employment | Employed for wages | 4 | 44% | 2 | 10% | 1 | 6% | ||

| Self-employed | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Out of work and looking for work | 1 | 11% | 3 | 15% | 1 | 6% | |||

| Out of work but not currently looking for work | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 6% | |||

| A homemaker (taking care of your own house or family) | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5% | 0 | 0% | |||

| A student, going to school | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 11% | |||

| Retired | 0 | 0% | 1 | 5% | 1 | 6% | |||

| Unable to work (disabled) | 2 | 22% | 11 | 55% | 7 | 39% | |||

| On family or maternity leave | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |||

| On medical or disability leave | 0 | 0% | 2 | 10% | 0 | 0% | |||

| Data missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 28% | |||

Only a limited range of demographic data was collected for crowdsourcing activity 3.

Participants could select more than one Race/Ethnicity category.

Nearly all participants of crowdsourcing activities 1 and 2 identified as Black/African American, while CAB and crowdsourcing contest participants were more varied in terms of race/ethnicity. When comparing socio-economic status, CAB participants differed substantially from crowdsourcing participants for whom data were available (crowdsourcing activities 1 and 2 only). All CAB participants had education levels encompassing some college education or higher, with the majority (6; 67%) holding Master’s degrees. In contrast, crowdsourcing participants included a larger proportion of individuals with lower education levels, with 13 (34%) participants reporting school diploma or GED as their highest level of education and 4 (10.5%) participants that did not complete high school. Crowdsourcing participants also had lower levels of employment; only 3 (7%) crowdsourcing participants reported being employed, compared to almost half (4, 44%) of CAB participants. Disability was higher among crowdsourcing participants, with 18 (47%) reporting being unable to work due to disability. Most (5, 56%) CAB participants reported an annual income in the $50,000 to $74,999 range, while almost half (18, 47%) of crowdsourcing participants reported an annual income of $10,000 or less.

Comparison of CAB and Crowdsourced Feedback

While crowdsourcing feedback in some instances overlapped with CAB feedback, there were points at which crowdsourcing provided more contextualization of CAB feedback. There were also instances where CAB and crowdsourcing feedback diverged, revealing unique concerns from the perspective of research-savvy CAB members compared to lay community members. These results are summarized in the infographic of Figure 1 (see Supplementary Table 1 for examples of additional/full-length excerpts of CAB and crowdsourcing feedback pertaining to identified themes).

Figure 1:

Summary of overlap, contextualization/extension, and divergences in CAB and crowdsourced feedback

Overlap in CAB and Crowdsourced Feedback

Both CAB and crowdsourced feedback were found to have two themes in common: ideas to enhance trial communication and support of trial participants. Feedback on enhancing communication particularly focused on the VOR-07 informed consent process. The use of videos/visual elements was identified by both CAB and crowdsourcing participants as ways that the informed consent process could be improved. CAB members noted that a video could help clarify information for potential participants; when we screened a video version of the informed consent form during the corresponding crowdsourcing activity, participants responded positively and felt this was preferable to a lengthy paper form for ease of understanding. Digital alternatives to the paper form (e.g. displaying on an iPad/tablet or phone) and quizzes were also independently suggested by both CAB and crowdsourcing participants as useful strategies to enhance communication.

Both CAB and crowdsourcing participants offered similar suggestions for how VOR-07 could include supports for trial participants, particularly in terms of additional psycho-social resources. As one CAB member noted, clinical trial researchers need to consider “not just your physical needs but also your social and emotional support needs as well” when participating in a trial [CAB discussion 2]. Similarly, crowdsourcing participants noted that having psycho-social resources in place would assuage potential concerns of trial participants and that “follow-up support via access to local resources (health-promoting, career building, healthcare access programs, etc.)” would be important after trial completion [crowdsourcing activity 3]. Both CAB and crowdsourcing feedback also described the need to acknowledge and foster the involvement of trial participants’ spouses/partners and other people in their lives as a supportive resource for trial participation. For example, a CAB member suggested that trial participants should be allowed to bring their partner(s) with them to clinic visits for support. A crowdsourcing participant similarly noted that it if she were in the trial, it would be helpful for VOR-07 researchers to provide information that she could use to inform important people in her life about the trial.

Crowdsourced Feedback as Contextualization/Extension of CAB Feedback

We identified two instances where crowdsourced feedback provided further elaboration or contextualization of points raised in CAB feedback: the implications of ensuring a ‘positive’ trial participation experience, and the impact of socio-economic factors on trial participation.

In CAB feedback, the importance of creating a positive experience for trial participants was described in relation to both the trial environment (e.g. ensuring positive interactions between participants/staff) as well as demonstrating appreciation for trial participants. CAB members emphasized that clinical trial researchers could help trial participants feel valued by providing tokens of appreciation at milestones during the trial and/or after trial completion. This would be separate from financial compensation, such as a thank-you letter, a summary of research findings, or even hosting an event for trial participants to celebrate their research contributions.

Crowdsourcing participants similarly noted the importance of making trial participants feel appreciated and suggested ideas for how researchers could demonstrate this both during and after a trial; for example, by hosting a “wrap-party” post-trial for both participants and staff [crowdsourcing activity 3]. However, crowdsourcing feedback also revealed that creating a positive trial experience is important not only for trial participants, but also for future relationships between researchers and the community from which participants are recruited. Noting that word-of-mouth communication through personal networks is one of the main ways that community members find out about new clinical trials, a crowdsourcing participant explained that “if one person participates in this trial and they say all negative stuff, then it’s gonna be really, really hard for the researchers to enroll people. Because all they know is the negativity part of it” [crowdsourcing activity 2]. Creating a positive trial experience also extends beyond the timeline of the trial; as one crowdsourcing participant noted, trial researchers should “continue to keep up with participants to build a relationship in the community and encourage participation in future trials” [crowdsourcing activity 3].

The second area where crowdsourcing feedback provided further contextualization of CAB feedback was regarding the impact of socio-economic factors on trial participation, best illustrated by concerns about transportation and childcare resources for trial participants. CAB members noted that considering transportation to and from clinic visits is an important way that VOR-07 researchers could support trial participants’ retention in the trial; for example, by precisely noting the length of clinic visits so that participants taking public transit can plan accordingly, or by partnering with rideshare programs to make participation more accessible for rurally-located people. While transportation also emerged as a concern in crowdsourced feedback, participants mentioned additional concerns rooted in their experiences with socioeconomic disadvantage. For example, a crowdsourcing participant noted that providing trial participants with bus tickets does not necessarily help people with disabilities for whom city buses can be difficult to navigate, especially in bad weather. Another crowdsourcing participant noted that scheduling clinic visits towards the end of the month would make transportation more difficult as at this point money is tight for people who receive disability payments or other forms of social assistance.

Crowdsourcing feedback also extended CAB feedback on the need for childcare for trial participants by additionally raising questions about what impact the trial might have on other care relationships in trial participants’ lives. This feedback was grounded in experiences of providing and relying on informal (i.e. family-based, unpaid) care. For example, one crowdsourcing participant noted that she was also responsible for caring for her elderly parents, and that “they would need to know [about my trial participation] in case I couldn’t care for them. Or my children. Whoever was looking for me to be healthy, to be available” [crowdsourcing activity 2]. Providing additional care resources beyond childcare could be one way to facilitate participation in VOR-07.

Divergences in CAB and Crowdsourced Feedback

Finally, we observed multiple points of divergence between CAB and crowdsourced feedback, with particular themes emerging most strongly – or in some instances, exclusively – in the feedback of one group or another.

CAB members were particularly concerned with how broader, institution-level regulations may pose barriers to VOR-07 participation. For example, the requirement to state in informed consent forms that the institution running the trial would not be responsible for trial-related injury was identified as a potential barrier to recruitment. CAB participants recognized that this was an issue beyond VOR-07; as one CAB member noted, there are some aspects of a clinical trial that no amount of feedback from community engagement would be able to address as “it does not in the end come down to us. It comes down to institution, it comes down to funders, it comes down to government” [CAB discussion 1]. Since researchers cannot readily implement these broader systemic changes themselves, CAB participants suggested this was a conversation that had to be held at a higher level to improve HIV clinical trial processes.

Compared to crowdsourcing feedback, CAB feedback also more frequently emphasized the value of personalizing trial processes compared to crowdsourced feedback. Supports provided to VOR-07 participants should be “tailored on an individual basis” [CAB discussion 2] to ensure that participants are being treated based on individual needs and preferences. Personalization was suggested as a way to enhance recruitment; for example, by developing a database where persons who were interested in trial participation could upload a descriptive profile, which could then be periodically checked against new trials’ eligibility criteria. CAB participants also expressed a preference for learning about new HIV clinical trials from a primary physician, as one’s doctor can act as a personal “navigator” in deciding on a case-by-case basis whether a trial was an appropriate fit [CAB discussion 2].

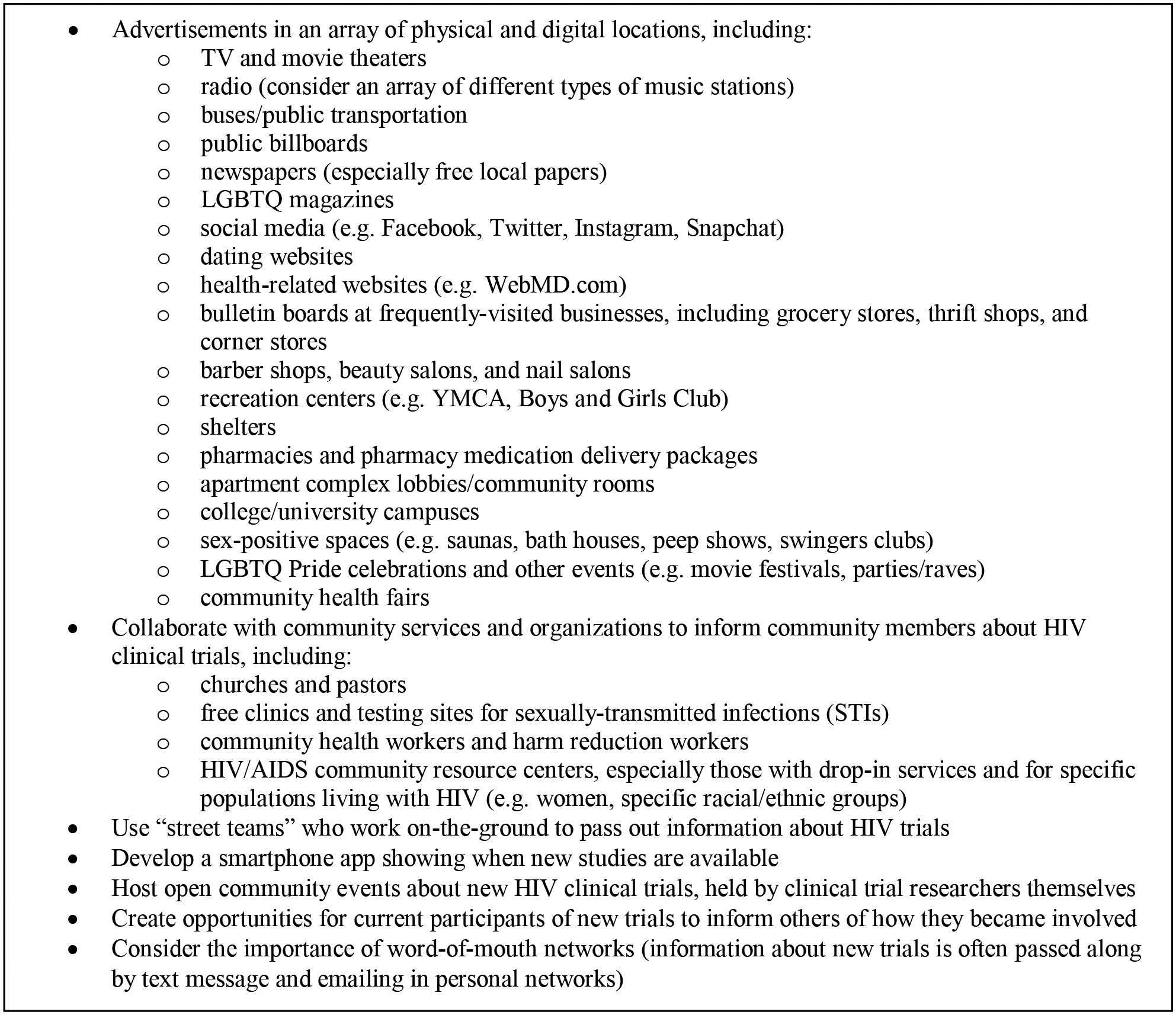

In contrast, learning about new HIV trials through one’s doctor did not resonate with crowdsourcing participants. They explained that going to the doctor is an infrequent event for most people, so participation opportunities may be missed if this is the route to recruitment. Instead, crowdsourcing participants felt that to effectively recruit for new HIV clinical trials, researchers need to “go where the people are” [crowdsourcing activity 3]. This feedback resulted in an extensive crowdsourced list of alternative strategies for raising awareness about trial participation opportunities in communities (see Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Crowdsourced ideas for alternative ways to learn about new HIV clinical trials

Compared to CAB participants, crowdsourced feedback expressed substantially more concern with the potential risks of VOR-07, particularly bodily harm (e.g. potential side effects of the trial medications/procedures, potential for injury or death during the trial, etc.) Crowdsourcing participants also questioned how blood samples taken during the trial would be used and whether it would be possible for the government to access personal information from these samples, and worried about the implications of reactivating latent viral cells in the body using vorinostat. Given these concerns, crowdsourcing participants felt that VOR-07 compensation was insufficient. As one noted, “the compensation doesn’t balance with what you’re giving up to do that [participating in the trial] or what else that it may cost on you” [crowdsourcing activity 1]. Another expressed that for her, the compensation simply would not be worth the potential risks, explaining “it’s just not enough…I think my life is worth more” [crowdsourcing activity 1].

Discussion

The ACCESS pilot sought to understand the extent to which crowdsourcing can extend and complement CAB feedback on an HIV cure clinical trial. Comparisons of demographic data and feedback from both engagement strategies suggest there are multiple benefits to using a crowdsourcing engagement strategy in addition to CAB feedback.

Demographic results show that while the majority of both CAB and crowdsourcing participants were African American, our crowdsourcing activities reached sub-populations underrepresented by the CAB, namely those with lower income, more unemployment, and more disability. This suggests that crowdsourcing can be a way to engage a wider range of community stakeholders, helping clinical trial researchers to extend voices that are not well-represent in CABs [23]. Engaging low-income African American community stakeholders is particularly important given this population’s experiences with being disproportionately impacted by the HIV epidemic [24], mistrust of biomedical research [25], and persistent underrepresentation in HIV research [26].

Our finding of overlap in the feedback obtained from both CAB and crowdsourcing suggests that CAB feedback can at least to some extent be considered representative of the concerns of broader community stakeholders. However, in some instances crowdsourcing served to further extend or contextualize CAB feedback. While CAB participants raised the issue that positive trial experiences and socioeconomic factors may impact trial participation, crowdsourcing revealed the meaning of these concerns from the perspective of community members who face multiple socioeconomic barriers to trial participation and may have had negative research experiences in the past. Conducting crowdsourcing alongside CAB engagement presents an opportunity to advance HIV clinical trial researchers’ socio-cultural competency in relation to the local community [23] and address UNAIDS/AVAC GPP guideline recommendations to consider the engagement of vulnerable populations [1].

We identified multiple divergences in CAB and crowdsourced feedback, providing unique insights from both trial-informed and lay perspectives. The emphasis in CAB feedback on regulatory requirements and tailoring of HIV trial processes is likely due to CAB members’ greater familiarity with trial processes through ongoing involvement in HIV research and subsequent access to advanced training opportunities [27]. CAB feedback may thus be well positioned to identify broader institutional or systemic concerns inherent to HIV clinical trials. Crowdsourced feedback emphasizing the need for alternative methods of advertising new HIV clinical trials provides researchers with community-identified solutions for enhancing recruitment. Additionally, crowdsourced concerns about the risks associated with trial participation suggest a need for greater community education and outreach regarding clinical trial procedures. This may be particularly important given evidence that fear is a barrier to the participation of underrepresented populations in HIV clinical trials [28–30]. These findings additionally demonstrate the value of conducting multiple engagement strategies, as implementing only one or the other strategy would have resulted in limited feedback compared to implementing both. This evidence supports the argument that researchers should consider an array of different engagement strategies when developing HIV clinical trials [1, 11, 31].

There are some limitations to consider in this pilot study. Crowdsourcing activities 1 and 2 were conducted during the workday, which likely influenced the sociodemographic profile of participants. This limitation may be somewhat mitigated by our idea contest for crowdsourcing activity 3, which included submission opportunities at an in-person evening event and online. However, it is unknown whether these opportunities reached a different segment of the community as we did not collect long-form sociodemographic survey data with contest submissions. In future scale-up efforts based on this pilot, we recommend that crowdsourcing events be held at a variety of times, including weekends and evenings; this may also help to increase the sample size. Additionally, we invited participation from only one CAB for the CAB feedback portion of the pilot, and thus may have limited our ability to benefit from CABs with different kinds of experiences in providing input on HIV clinical trials. Finally, we recognize that while all discussion questions and contest prompts used in crowdsourcing were the same as those used in discussion with the CAB., presenting CAB and crowdsourcing participants with different kinds of engagement activities is a potential confounding factor in comparing the feedback obtained from each engagement strategy. However, the purpose of our comparison of CAB and crowdsourced feedback (i.e. assessing the ability of crowdsourcing to complement and extend CAB feedback) does not require engagement activities to be replicated. Furthermore, our adaptation of CAB materials was necessary in order to open our crowdsourcing activities to a broad range of potential participants (e.g. laypersons unfamiliar with clinical research, persons with varying levels of literacy, etc.)

Our pilot study provides evidence that conducting crowdsourcing in addition to CAB engagement yields a broader range of stakeholder feedback to inform HIV clinical trials. Crowdsourcing as a community engagement strategy enhances and extends CAB feedback in useful and at times unique ways, and increases engagement of subpopulations typically underrepresented in HIV research. HIV clinical trial researchers are thus encouraged to consider crowdsourcing as one potential promising strategy for meeting the GPP guideline recommendations to use an array of engagement strategies for obtaining community stakeholder feedback [1].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all participants of our CAB and crowdsourcing community engagement activities, without whom this research would not have been possible. We also gratefully acknowledge the VOR-07 study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03803605) and VOR-07 clinical team for their collaboration and contributions to the ACCESS pilot.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIAID project number 5R01A108366 and 1K24AI143471). VOR-07 is also supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIAID project number UM1-AI-26619 and U01-AI-117844).

SD, SR and JDT developed the initial concept for the study, with substantial input from AM, MB and TV as well as in collaboration with CLG, JDK and DMM. Data collection tools were developed by SD and AM, with input from MB, SR, JDT, CLG, and JDK. Data were collected and analyzed by SD, MB, TV, and HM, with additional review and feedback on the final analysis by SR, JDT, CLG, JDK, and DMM. The manuscript was initially drafted by SD, with literature reviews provided by AM, TV and HM, as well as input from MB, SR, JDT, JDK, CLG, and DMM. All authors contributed to finalizing the manuscript through substantial review, feedback and revisions.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIAID project numbers 5R01A108366, 1K24AI143471, UM1-AI-26619, and U01-AI-117844). Dr. Allison Mathews is CEO and founder of Community Expert Solutions. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.UNAIDS/AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition. Good participatory practice: guidelines for biomedical HIV prevention trials. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brizay U, Golob L, Globerman J, Gogolishvili D, Bird M, Rios-Ellis B, et al. Community-academic partnerships in HIV-related research: a systematic literature review of theory and practice. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18:19354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman PA, Rubincam C, Slack C, Essack Z, Chakrapani V, Chuang DM, et al. Towards a Science of Community Stakeholder Engagement in Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials: An Embedded Four-Country Case Study. PLoS One 2015; 10(8):e0135937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thabethe S, Slack C, Lindegger G, Wilkinson A, Wassenaar D, Kerr P, et al. “Why Don’t You Go Into Suburbs? Why Are You Targeting Us?”: Trust and Mistrust in HIV Vaccine Trials in South Africa. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics : JERHRE 2018; 13(5):525–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills EJ, Singh S, Singh JA, Orbinski JJ, Warren M, Upshur RE. Designing research in vulnerable populations: lessons from HIV prevention trials that stopped early. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2005; 331(7529):1403–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh JA, Mills EJ. The abandoned trials of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: what went wrong? PLoS medicine 2005; 2(9):e234–e234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ukpong M, Peterson K. Oral Tenofovir Controversy II: Voices from the field: a series of reports of the oral tenofovir trials from the perspectives of active community voices engaged on the field in Cambodia, Cameroon, Nigeria, Thailand and Malawi. New HIV Vaccine and Microbicide Advocacy Society 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day S, Blumberg M, Vu T, Zhao Y, Rennie S, Tucker JD. Stakeholder engagement to inform HIV clinical trials: a systematic review of the evidence. J Int AIDS Soc 2018; 21 Suppl 7:e25174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isler MR, Miles MS, Banks B, Perreras L, Muhammad M, Parker D, et al. Across the Miles: Process and Impacts of Collaboration with a Rural Community Advisory Board in HIV Research. Progress in community health partnerships : research, education, and action 2015; 9(1):41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacKellar DA, Gallagher KM, Finlayson T, Sanchez T, Lansky A, Sullivan PS. Surveillance of HIV risk and prevention behaviors of men who have sex with men--a national application of venue-based, time-space sampling. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974) 2007; 122 Suppl 1:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo YR, Chu C, Ananworanich J, Excler JL, Tucker JD. Stakeholder Engagement in HIV Cure Research: Lessons Learned from Other HIV Interventions and the Way Forward. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015; 29(7):389–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker JD, Day S, Tang W, Bayus B. Crowdsourcing in medical research: concepts and applications PeerJ 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.clinicaltrials.gov. Study to Assess Safety and Activity of Combination Therapy of VRC07-523LS and Vorinostat on HIV-infected Persons. In: NIH U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corneli A, Meagher K, Henderson G, Peay H, Rennie S. How Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials Incorporate Behavioral and Social Sciences Research: A Typology of Approaches. AIDS and Behavior 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang W, Wei C, Cao B, Wu D, Li KT, Lu H, et al. Crowdsourcing to expand HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: A closed cohort stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLOS Medicine 2018; 15(8):e1002645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tucker JD, Tang W, Li H, Liu C, Fu R, Tang S, et al. Crowdsourcing designathon: a new model for multisectoral collaboration. BMJ Innovations 2018; 4(2):46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews A, Farley S, Blumberg M, Knight K, Hightow-Weidman L, Muessig K, et al. HIV cure research community engagement in North Carolina: a mixed-methods evaluation of a crowdsourcing contest. Journal of Virus Eradication 2017; 3(4):223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang A, Pan X, Wu F, Zhao Y, Hu F, Li L, et al. What Would an HIV Cure Mean to You? Qualitative Analysis from a Crowdsourcing Contest in Guangzhou, China. AIDS research and human retroviruses 2018; 34(1):80–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day S, Mathews A, Blumberg M, Vu T, Rennie S, Tucker JD. Broadening community engagement in clinical research: Designing and assessing a pilot crowdsourcing project to obtain community feedback on an HIV clinical trial. Clinical Trials 2020; DOI 10.1177/1740774520902741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health promotion practice 2006; 7(3):312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss A, and Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boeije H A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity 2002; 36(4):391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman PA, Rubincam C. Advancing community stakeholder engagement in biomedical HIV prevention trials: principles, practices and evidence. Expert review of vaccines 2014; 13(12):1553–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cargill VA, Stone VE. HIV/AIDS: a minority health issue. The Medical clinics of North America 2005; 89(4):895–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Kressin NR, Green BL, Wang MQ, James SA, et al. The Tuskegee Legacy Project: willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved 2006; 17(4):698–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Cohn SE, Krishnan S, Cespedes M, Floris-Moore M, Schulte G, et al. Minorities Remain Underrepresented in HIV/AIDS Research Despite Access to Clinical Trials. HIV clinical trials 2014; 15(1):14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kagee A, De Wet A, Kafaar Z, Lesch A, Swartz L, Newman PA. Caveats and pitfalls associated with researching community engagement in the context of HIV vaccine trials. Journal of health psychology 2017; DOI 10.1177/1359105317745367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman PA, Duan N, Roberts KJ, Seiden D, Rudy ET, Swendeman D, et al. HIV vaccine trial participation among ethnic minority communities: barriers, motivators, and implications for recruitment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006; 41(2):210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks RA, Newman PA, Duan N, Ortiz DJ. HIV vaccine trial preparedness among Spanish-speaking Latinos in the US. AIDS Care 2007; 19(1):52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toledo L, McLellan-Lemal E, Arreola S, Campbell C, Sutton M. African-American and Hispanic perceptions of HIV vaccine clinical research: a qualitative study. American journal of health promotion : AJHP 2014; 29(2):e82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West Slevin K, Ukpong M, Heise L. Community engagement in HIV prevention trials: evolution of the field and opportunities for growth. Aids2031 Science and Technology Working Group 2008; (11). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Community Expert Solutions. Community Expert Solutions. In; 2019.

- 33.Zhang Y, Kim JA, Liu F, Tso LS, Tang W, Wei C, et al. Creative Contributory Contests to Spur Innovation in Sexual Health: 2 Cases and a Guide for Implementation. Sex Transm Dis 2015; 42(11):625–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.