Structured Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate real-world effects of enhanced recovery protocol (ERP) dissemination on clinical and economic outcomes after colectomy.

Summary Background Data:

Hospitals aiming to accelerate discharge and reduce spending after surgery are increasingly adopting perioperative ERPs. Despite their efficacy in specialty institutions, most studies have lacked adequate control groups and diverse hospital settings and have considered only in-hospital costs. There remain concerns that accelerated discharge might incur unintended consequences.

Methods:

Retrospective, population-based cohort including patients in 72 hospitals in the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative clinical registry (N=13,611) and/or Michigan Value Collaborative claims registry (N=14,800) who underwent elective colectomy, 2012–2018. Marginal effects of ERP on clinical outcomes and risk-adjusted, price-standardized 90-day episode payments were evaluated using mixed-effects models to account for secular trends and hospital performance unrelated to ERP.

Results:

In 24 ERP hospitals, patients Post-ERP had significantly shorter length of stay than those Pre-ERP (5.1 vs. 6.5 days, p<0.001), lower incidence of complications (14.6% vs. 16.9%, p<0.001) and readmissions (10.4% vs. 11.3%, p=0.02), and lower episode payments ($28,550 vs. $31,192, p<0.001) and post-acute care ($3,384 vs. $3,909, p<0.001). In mixed-effects adjusted analyses, these effects were significantly attenuated—ERP was associated with a marginal length of stay reduction of 0.4 days (95% confidence interval 0.2–0.6 days, p=0.001), and no significant difference in complications, readmissions, or overall spending.

Conclusions:

ERPs are associated with small reduction in postoperative length of hospitalization after colectomy, without unwanted increases in readmission or post-acute care spending. The real-world effects across a variety of hospitals may be smaller than observed in early-adopting specialty centers.

Mini-Abstract

In a population-based cohort from statewide hospital collaboratives, enhanced recovery protocol implementation was associated with a half-day reduction in postoperative hospitalization. The marginal benefit was smaller than differences seen in single-institution studies before and after implementation, but there was no evidence of unintended adverse consequences after discharge.

Introduction

Hospitals are facing unprecedented pressure to improve the efficiency of inpatient care, including major surgery. With the advent of Accountable Care Organizations and episode-based reimbursement, hospitals must reduce practice variation and length of hospitalization, while also attending to payments for care after discharge. An increasingly common strategy to achieve these ends in surgery is the use of enhanced recovery protocols (ERPs) - evidence-based, multidisciplinary perioperative bundles including surgical, anesthetic, nursing, and medical management.1,2 Studies from high-volume, specialty practices in several countries demonstrate that ERP can minimize physiologic stress from surgery, shorten hospitalization, and hasten recovery.3–7

Despite increasing evidence of effectiveness in these settings, the real-world effects of ERP dissemination remain uncertain. First, the expected benefits of ERP may not extrapolate beyond the highly selected centers in which they have been studied. Hospital networks in several countries have mandated ERP for colorectal surgery,8 yet very few studies have evaluated implementation evaluations beyond specialty centers.9–11 Regional evaluations have found significant barriers to ERP adoption in the absence of large-scale coordinated implementation efforts, especially in smaller hospitals.12,13 Because the benefits of ERP are highly dependent on adherence to core elements,14–17 its success will depend on the fidelity of implementation across hospitals and thus may not be uniformly effective in all settings. Second, ERP appears to reduce utilization of hospital services, but few studies have thoroughly evaluated its effect on healthcare spending across the entire surgical episode.18–20 In-hospital efficiencies from ERP could be undermined if early discharge incurs late complications or substitution with outpatient ancillary care services.21–24 And third, most studies have used a simple comparison of outcomes before and after implementation of ERP, without accounting for background trends in efficiency and utilization independent of the intervention.

To address these unanswered concerns, we evaluated trends in ERP adoption within a population-based, statewide, multi-hospital collaborative.13 Unlike previous studies that have relied on comparisons of pre- and post-implementation periods, this analysis accounts for statewide temporal trends and hospital-specific performance, and then estimates the independent marginal effect of ERP implementation on length of hospitalization, rates of readmission, and price-adjusted spending on care around elective colectomy. Rather than evaluating individual patients’ use of ERP, we estimate the overall effect of protocol adoption on the marginal outcomes in hospitals that initiated ERP during the study period.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

This study includes retrospective cohorts from the data registries of two statewide collaborative quality initiatives, both sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC) includes data on a sample of general, gynecological and vascular surgical patients from hospitals representing the full diversity of care settings in the state. Approximately 50,000 cases per year are abstracted, systematically sampling a maximum 25 eligible adult surgical cases selected per 8-day period, with a limitation on some high-volume, very low morbidity operations. Trained and audited nurse abstractors use a case-selection algorithm to minimize selection bias, and collect patient characteristics, perioperative processes of care, and 30-day postoperative outcomes, as described in detail previously.25 The Michigan Value Collaborative (MVC) is a hospital consortium focused on episode spending around hospitalization, and its dataset includes complete adjudicated claims for all services within 90 days after hospital discharge for individuals insured by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Preferred Provider Organization (commercial and Medicare Advantage), Blue Care Network, Blue Care Advantage (Medicare Advantage HMO) and Medicare fee-for-service programs.

In both datasets, we included all adult patients undergoing elective colon or rectal resections with or without stoma creation, between January 2012 and August 2018, according to Current Procedural Terminology codes for colon and rectal resections, with and without stoma creation. We excluded emergency and urgent operations identified in the MSQC registry, and excluded claims from the MVC registry in which the patient underwent unplanned admission through the emergency department. We excluded hospitals that performed less than 10 included cases per year.

There were 56 MSQC hospitals which met inclusion criteria, based on case volumes, and an additional 6 hospitals that met inclusion criteria in MVC data, but were not participants in MSQC, and are thus included in the analyses of payment data, but not outcomes data. The patient sampling differs between datasets: MSQC includes a systematic sample of operations irrespective of payer, as described above, whereas MVC includes all patients within the payment programs listed above. As a result, the proportion of patients included in both registries is limited, which makes use of a patient-level linkage between the datasets unfavorable. Because no included analysis required comparisons of clinical and payment outcomes for any discrete patient, we did not attempt to match patients between the datasets due to the significant loss of sample size and the potential errors in probabilistic matching between these de-identified datasets. There is still some overlap between patients included in the clinical outcomes analyses in MSQC and the economic outcomes in MVC, but no patient is included twice in any analysis. Because the MSQC registry has audited clinical chart review, we present patient and hospital characteristics from MSQC in the main exhibits, and characteristics from MVC in an eTable, http://links.lww.com/SLA/C876.

The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board deemed this secondary use of registry data to be exempt from human subjects review.

Evaluation of Enhanced Recovery Protocol Adoption

We have previously described in detail the conduct of a statewide survey of ERP adoption among MSQC member hospitals.13 We interviewed the stakeholders at each institution most knowledgeable about the hospital’s protocol for perioperative care of patients undergoing elective colorectal resection. We applied a strict definition of ERP that included, at a minimum, preoperative education, carbohydrate loading, multimodal analgesia, intravenous fluid limitation, early enteral nutrition and ambulation,2 and defined a start date for protocol implementation. We did not attempt to assess rates of use of the ERP within hospitals, or individual patients’ compliance with ERP components, because we sought to evaluate the real world effectiveness of ERP adoption, rather than its efficacy among only those patients to whom it was most successfully applied. Thus, we evaluated the marginal effect on hospitals’ average clinical and payment outcomes associated with the time period of ERP adoption in each institution.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was risk-adjusted, price-standardized 90-day total episode payments, derived from MVC data, and computed according to Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare algorithms26 to account for intended differences from regional wage variation, graduate medical education, and uncompensated care. We measured readmission spending and included all hospital payments for readmissions initiated within 90 days of discharge after the index procedure. We also evaluated post-acute care spending in the 90 days after discharge from index hospitalization (including home health, skilled nursing facility, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation). To conform with emerging bundled payment programs, we prorated readmission and post-acute care payments to home health care and rehabilitation hospitals to the 90-day window. Payments to skilled nursing facilities were based on per diem payments during the episode.

Secondary outcomes, derived from MSQC clinical registry data, included postoperative length of stay, readmissions, complications, and serious complications (including kidney injury with dialysis, anastomotic leak with intervention, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, deep or organ/space surgical site infection, septic shock, severe sepsis, stroke, unplanned intubation), as defined within MSQC.

Statistical Analyses

We categorized the primary predictor for patients in three groups, according to the status of the hospital in which the operation occurred: (i) “Never-ERP” patients treated in hospitals that never implemented an ERP; (ii) “Pre-ERP” patients treated in ERP hospitals before the ERP was implemented; and (iii) “Post-ERP” patients treated in hospitals after full ERP implementation. Differences in case-mix between groups were assessed in the clinical and claims registries using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVA F-tests for continuous variables. Differences in hospitals size and teaching status between ERP vs non-ERP hospitals were evaluated using chi-squared tests. Differences in mean procedure volume were evaluated with t-tests.

Payment outcomes were measured using MVC claims data, and clinical outcomes (length of stay, percentage of readmissions, any complications, and serious complications) were measured using the MSQC outcomes registry data. To compare price-adjusted payments and clinical outcomes after elective colectomy between ERP hospitals and hospitals that did not adopt ERP, we constructed generalized linear mixed effects models for each outcome of interest. Both clinical and payment models included patient comorbidity indicators, colectomy type (partial colectomy, LAR, total colectomy), age, sex, insurance type, hospital size, teaching status, ERP adoption, time trends, an interaction between time trends and ERP adoption, and a hospital-specific random intercept, as these are all available in both datasets. Comorbidities in MSQC data are determined by audited medical record review within a standardized data entry interface, whereas comorbidities in MVC data were classified according to hierarchical condition categories, as defined for administrative claims data. Clinical outcomes models also included race, as it was available in the MSQC registry but not in administrative claims in MVC.

These models are designed to estimate the effect of a treatment on groups exposed to an intervention at different times of implementation, while accounting for the average outcomes of the individual groups both with and without the intervention. From these models, for each outcome, we calculated the predicted outcome levels for patients treated with versus without an ERP, the marginal effect of the ERP, and a 95% confidence interval and p-value for the marginal effect of ERP on the outcome of interest.

As sensitivity analyses, we conducted ordinary least squares regression and hospital-matched difference-in-differences comparisons for the primary and secondary outcomes. We also stratified by the occurrence of postoperative complications and evaluated outcomes among those patients without documented complications, in order to evaluate whether putative benefits of ERP might depend on freedom from adverse postoperative events. We present the mixed-effects analyses, which focus on the association between ERP and the outcomes, accounting for time trend and hospital-specific contributions, rather than difference-in-differences, because of the potential for bias in the one-to-one matching of ERP and control hospitals, given the small sample of hospitals from which to choose well-matched controls.

Statistical significance was set at α=0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 and Stata 15.0.

Results

Characteristics of patients and hospitals, by enhanced recovery protocol adoption

There were a total of 13,611 colectomy patients in the MSQC registry data, 6,071 (44.6%) Never-ERP, 3,633 (26.7%) Pre-ERP, and 3,907 (28.7%) Post-ERP.

Although there were statistically significant differences between these groups in many patient and procedure characteristics, most were of small magnitude (Table 1). For example, there were more patients over age 65 in the Never-ERP group (49.4%) than in the Pre-ERP (44.4%) or Post-ERP (43.9%) groups (p<0.001). There were also more patients with fee-for-service Medicare (40.8% vs. 38.2% vs. 33.9%, p<0.001), though not more with Medicare Advantage or Medicaid. There were more patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes in the Never-ERP hospitals. Never-ERP hospitals performed more segmental colectomies, and fewer total colectomy and proctectomy procedures than the ERP hospitals, both before and after ERP adoption. The distribution of surgical indications was statistically different, but the proportions were similar across groups.

Table 1:

Patient and procedure characteristics by enhanced recovery protocol adoption status. Values are presented as N (%) and comparisons evaluated with chi-squared tests.

| Never-ERP N=6071 | Pre-ERP N=3633 | Post-ERP N=3907 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–54 | 1474 (24.3%) | 1086 (29.9%) | 1113 (28.5%) | <0.001 |

| 55–64 | 1599 (26.3%) | 932 (25.7%) | 1077 (27.6%) | ||

| 65–74 | 1704 (28.1%) | 873 (24.0%) | 1017 (26.0%) | ||

| 75+ | 1294 (21.3%) | 742 (20.4%) | 700 (17.9%) | ||

| Sex | Male | 2856 (47.0%) | 1642 (45.2%) | 1831 (46.9%) | 0.18 |

| Female | 3215 (53.0%) | 1991 (54.8%) | 2076 (53.1%) | ||

| Race | White | 5273 (86.9%) | 2904 (79.9%) | 3374 (86.4%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 560 (9.2%) | 554 (15.2%) | 377 (9.6%) | ||

| Other | 238 (3.9%) | 175 (4.8%) | 156 (4.0%) | ||

| Insurance | Medicare | 2475 (40.8%) | 1389 (38.2%) | 1324 (33.9%) | <0.001 |

| Medicare Advantage | 389 (6.4%) | 154 (4.2%) | 297 (7.6%) | ||

| Commercial | 2383 (39.3%) | 1614 (44.4%) | 1602 (41.0%) | ||

| Medicaid | 460 (7.6%) | 202 (5.6%) | 335 (8.6%) | ||

| Other | 364 (6.0%) | 274 (7.5%) | 349 (8.9%) | ||

| Ascites | 14 (0.2%) | 10 (0.3%) | 9 (0.2%) | 0.90 | |

| Bleeding disorder | 154 (2.5%) | 109 (3.0%) | 73 (1.9%) | 0.006 | |

| Body weight loss | 206 (3.4%) | 139 (3.8%) | 170 (4.4%) | 0.049 | |

| Cancer | 2389 (39.4%) | 1472 (40.5%) | 1518 (38.9%) | 0.31 | |

| CHF | 41 (0.7%) | 12 (0.3%) | 9 (0.2%) | 0.002 | |

| COPD | 618 (10.2%) | 288 (7.9%) | 276 (7.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 983 (16.2%) | 476 (13.1%) | 499 (12.8%) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 1114 (18.3%) | 605 (16.7%) | 623 (15.9%) | 0.005 | |

| Dialysis | 28 (0.5%) | 16 (0.4%) | 17 (0.4%) | 0.98 | |

| DVT | 326 (5.4%) | 217 (6.0%) | 231 (5.9%) | 0.36 | |

| ETOH | 238 (3.9%) | 103 (2.8%) | 127 (3.3%) | 0.013 | |

| Hypertension | 3483 (57.4%) | 1963 (54.0%) | 1929 (49.4%) | <0.001 | |

| Open wound | 80 (1.3%) | 57 (1.6%) | 52 (1.3%) | 0.55 | |

| Pneumonia | 15 (0.2%) | 5 (0.1%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0.054 | |

| PVD | 163 (2.7%) | 84 (2.3%) | 68 (1.7%) | 0.009 | |

| Sepsis (pre-op) | 25 (0.4%) | 21 (0.6%) | 12 (0.3%) | 0.19 | |

| Smoker | 1394 (23.0%) | 713 (19.6%) | 822 (21.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Transfusion (pre-op) | 59 (1.0%) | 43 (1.2%) | 13 (0.3%) | <0.001 | |

| Ventilator dependent | 5 (0.1%) | 5 (0.1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0.23 | |

| Type of Resection | Segmental colectomy | 4153 (68.4%) | 2287 (63.0%) | 2533 (64.8%) | <0.001 |

| Proctectomy | 1576 (26.0%) | 1030 (28.4%) | 1104 (28.3%) | ||

| Total colectomy/proctocolectomy | 342 (5.6%) | 316 (8.7%) | 270 (6.9%) | ||

| Indication | Cancer | 2389 (39.4%) | 1472 (40.5%) | 1518 (38.9%) | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | 61 (1.0%) | 118 (3.3%) | 86 (2.2%) | ||

| Diverticulitis | 1397 (23.0%) | 706 (19.4%) | 937 (24.0%) | ||

| Other | 2224 (36.6%) | 1337 (36.8%) | 1366 (35.0%) | ||

In the MVC data, there were 14,800 patients, 5,706 (38.6%) Never-ERP, 4,037 (27.3%) Pre-ERP, and 5,057 (34.2%) Post-ERP. Comparisons of characteristics of patients from the MVC claims registry are presented in the eTable, http://links.lww.com/SLA/C876.

As we have reported previously, ERP hospitals were significantly more likely than non-ERP hospitals to be large academic institutions (Table 2). Among 24 ERP hospitals, 17 (71%) had 300 beds or more, versus 10 of 38 (26%) of non-ERP hospitals (p=0.002); and 7 (29%) ERP hospitals were academic teaching institutions, compared with only 1 (3%) non-ERP hospital (p=0.002). ERP hospitals had significantly higher annual number of colectomies recorded in the MVC claims (60 vs. 24, p<0.001; note that MVC claims only represent the sampled payers, not all operations performed in the hospitals).

Table 2:

Characteristics of hospitals, by enhanced recovery protocol adoption. Bed size and teaching status are presented as N (%) and comparisons evaluated with chi-squared tests. Procedural volume is presented as mean (standard deviation) and compared using t-test.

| Non-ERP hospitals N=38 | ERP hospitals N=24 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <300 beds | 28 (74%) | 7 (29%) | 0.002 |

| 300–499 beds | 7 (18%) | 10 (42%) | |

| ≥500 beds | 3 (8%) | 7 (29%) | |

| Academic/Teaching | 1 (3%) | 7 (29%) | 0.002 |

| Community/Non-Academic | 37 (97%) | 17 (71%) | |

| Annual colectomy volume (in MVC claims) | 24 (16) | 60 (51) | <0.001 |

Unadjusted postoperative outcomes, by enhanced recovery protocols adoption status

Comparisons of the clinical and economic outcomes of patients in the Never-ERP, Pre-ERP, and Post-ERP groups are shown in Table 3. Before adjustment for patient and hospital factors, mean postoperative length of stay was significantly longer for Pre-ERP patients (6.5+/−5.1 days) than for Never-ERP (5.6+/−4.2 days) or Post-ERP (5.1+/−4.3 days) patients. The incidence of complications, serious complications, and readmissions were all significantly higher among Pre-ERP patients than those in Never-ERP hospitals or in the Post-ERP group.

Table 3:

Unadjusted outcomes, by enhanced recovery protocol adoption status.

| Clinical Registry (MSQC) | Never-ERP N=6071 | Pre-ERP N=3633 | Post-ERP N=3907 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay, mean (standard deviation) | 5.6 (4.2) | 6.5 (5.1) | 5.1 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Complications, N (%) | 948 (15.6%) | 615 (16.9%) | 571 (14.6%) | <0.001 |

| Serious complications, N (%) | 543 (8.9%) | 355 (9.8%) | 281 (7.2%) | <0.001 |

| Readmission within 30 days, N (%) | 571 (9.5%) | 402 (11.3%) | 407 (10.4%) | 0.02 |

| Claims Registry (MVC) | Never-ERP n=5706 | Pre-ERP n=4037 | Post-ERP n=5057 | p-value |

| Total Episode Payment, mean (standard deviation) | $29,228 ($23,948) | $31,192 ($30,814) | $28,550 ($29,799) | <0.001 |

| Index Payment, mean (standard deviation) | $18,142 ($12,324) | $19,472 ($21,872) | $17,872 ($20,315) | <0.001 |

| Post-Acute Care Payment, mean (standard deviation) | $3,907 ($7,278) | $3,909 ($7,173) | $3,384 ($8,612) | <0.001 |

| Readmission Payment, mean (standard deviation) | $3,156 ($11,054) | $3,208 ($9,363) | $3,150 ($11,208) | 0.96 |

Serious complications include: Kidney injury with dialysis, anastomotic leak with intervention, cardiac Arrest, myocardial infarction, deep or organ/space surgical site infection, septic shock, severe sepsis, stroke, unplanned intubation.

Similarly, the average total episode spending associated with colectomy among the Pre-ERP patients ($31,192+/−$30,814) was significantly greater than the average spending for Never-ERP hospitals’ patients ($29,228+/−$23,948) and Post-ERP patients ($28,550+/−$29,799). The differences were mainly attributable to differences in payments for the index hospitalization. Post-acute care payments were significantly lower for the Post-ERP patients than for non-ERP or never-ERP patients.

Estimated effect of enhanced recovery protocol adoption on postoperative outcomes

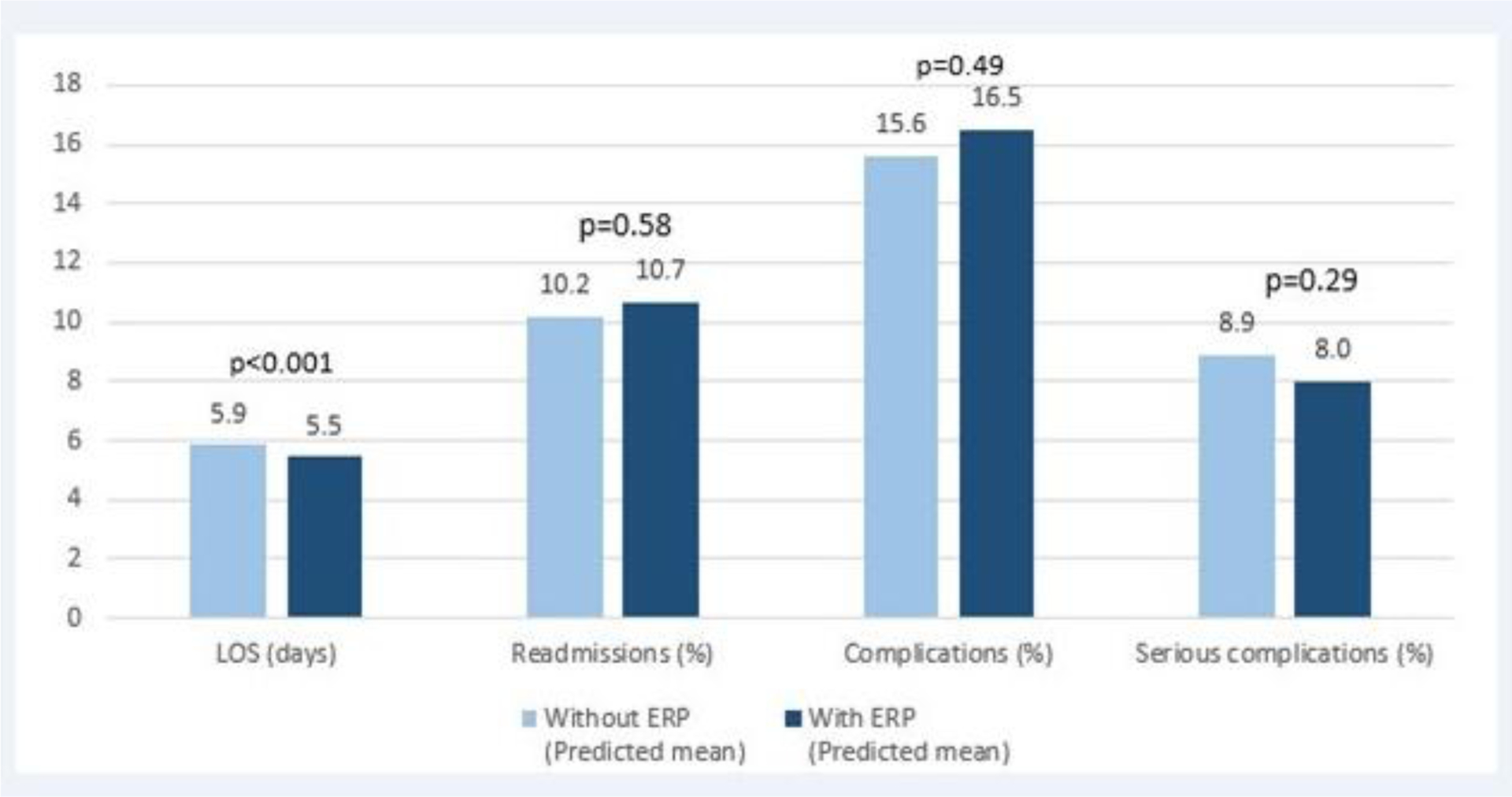

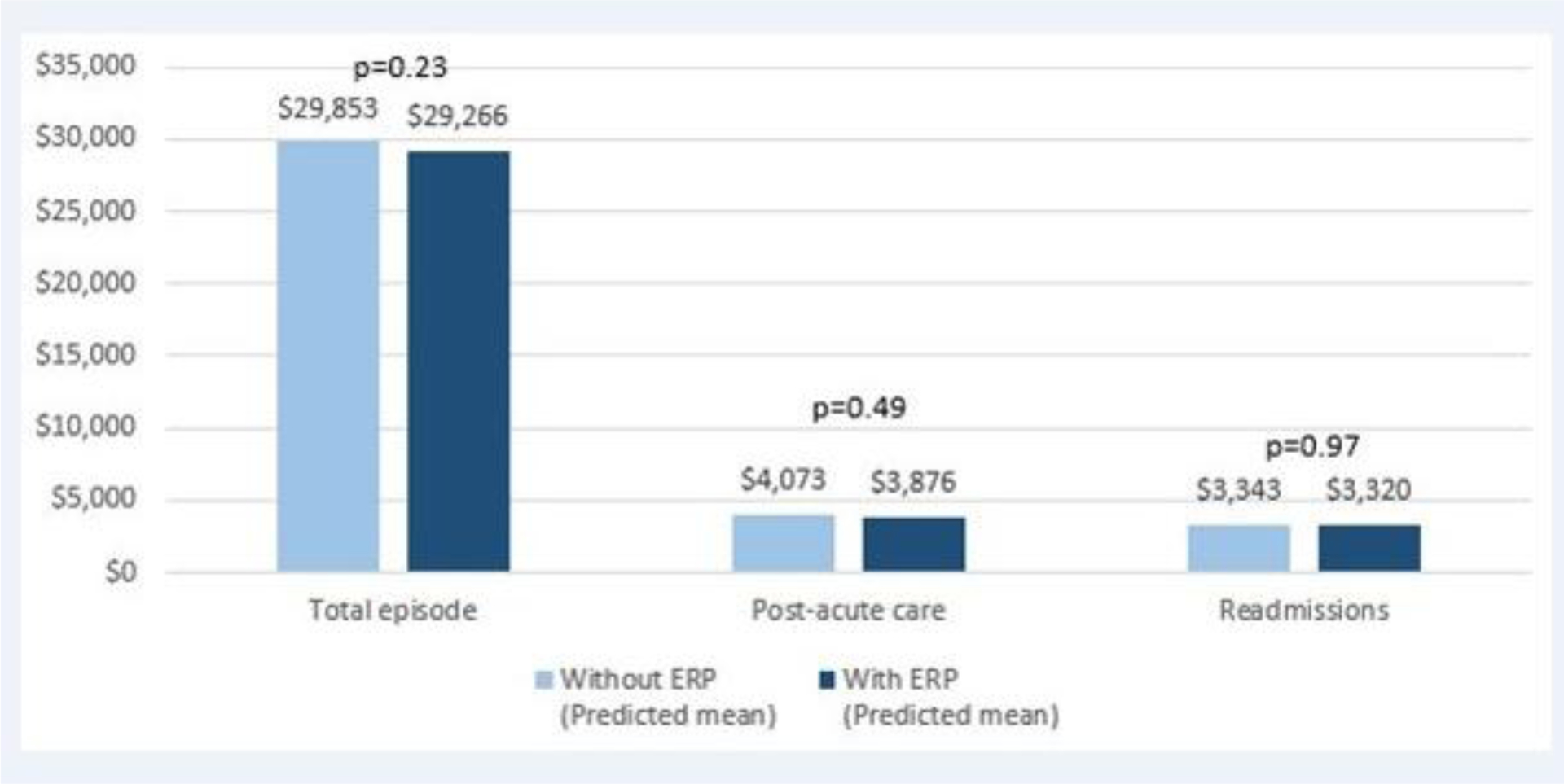

Results of adjusted mixed effects analyses estimate the adjusted effect of exposure to ERP, accounting for temporal trends and differences between hospitals unrelated to their ERP implementation. Findings from analyses of clinical outcomes, displayed in Figure 1, indicate that ERP adoption is associated with a significant marginal average decrease in postoperative length of stay of 0.4 days (95% confidence interval 0.2 to 0.6 days, p=0.001). However, after adjustment there was no significant marginal effect of ERP on the incidence of complications, serious complications, or readmissions. Likewise, the estimated effects of ERP on episode spending were all small and not statistically significant, as shown in Figure 2. The estimated marginal effect of ERP on total episode spending was −$587 (95% confidence interval −$1549 to +$376, p=0.23); on post-acute care spending −$197 (95% confidence interval −$760 to +$365, p=0.49); and on readmission spending −$23 (95% confidence interval −$1093 to +$1047, p=0.97).

Figure 1:

Estimated marginal effects of enhanced recovery protocols on clinical outcomes after colectomy.

Figure 2:

Estimated marginal effects of enhanced recovery protocols on economic outcomes after colectomy.

In sensitivity analyses, the findings after stratification, including only those patients without postoperative complications, were largely similar, except that the estimated marginal effect on post-acute care spending was greater and statistically significant (−$464, 95% confidence interval −$916 to −$11, p=0.04). Likewise, analyses utilizing alternative approaches, including ordinary least squares regression and hospital-matched difference-in-differences reached the same conclusions.

Discussion

In this study of ERP adoption in Michigan hospitals, after accounting for differences in patients, procedures, hospital performance, and statewide secular trends, we found that ERP adoption was associated with an incremental half-day reduction in postoperative length of stay after colectomy. Consistent with previous studies,22,27 there was no evidence that accelerated discharge incurred unintended consequences of increased readmissions or post-acute care expenditures. Therefore, hospitals adopting ERP likely accomplished varied aims, accelerating patient recovery and reducing their internal costs of hospital care, while maintaining clinical revenue from payers.

These findings echo previous studies of enhanced recovery in colorectal surgery, but add a novel, robust assessment of the marginal effect of ERP. By drawing from broad statewide quality collaboratives with a wide diversity of hospitals, and applying an analytic approach to account for secular trends and differences in practices and performance, this study estimates the independent effect of ERP adoption on key clinical and cost outcomes. In addition to adjusting for confounding characteristics of patients and procedures, as a typical regression would, the mixed effects model takes into account within-hospital clustering of outcomes. Inclusion of a time-variable indicator of ERP status, as well as temporals trends, and a term for the interaction between them, the change associated with adoption of ERP can be estimated, regardless of when implementation occurred in the study period. As a result, this approach is less susceptible to common biases of comparisons before and after an intervention, lacking control groups. The need for this approach can be seen by comparing the findings of our unadjusted comparisons against the marginal effects. The differences observed between Pre-ERP and Post-ERP patients would have significantly overestimated the effect of ERP as compared with the findings from the mixed effects models.

This study also offers unique perspective on the economic consequences of ERP implementation, evaluating real payments across an entire surgical episode. Most previous studies evaluated in-hospital costs alone, and do not address concerns that shorter hospital stays incur greater post-discharge ancillary care spending. Because many complications, especially after colectomy, occur after hospital discharge,28,29 and post-acute care accounts for the majority of variation in total episode spending around hospitalization,30,31 data on hospital spending alone do not address the full costs of surgical episodes. Further, many studies rely on submitted charges, an unreliable indicator of actualized payments, whereas this study evaluates real price-standardized payments, which represent payer and societal perspectives on the total costs of surgery. We find that payers’ total episode expenditures for perioperative care were not affected by ERP implementation, except for post-acute care payments among those without complications. The finding in this subgroup may be a spurious finding, or may indicate a tendency toward more efficient use of services across the episode within ERP programs. Regardless, there was certainly no evidence to support concerns that earlier hospital discharge might shift costs toward readmissions or post-acute care.32,33

These findings also reinforce ongoing challenges to dissemination of ERP across US hospitals. These barriers are echoed in qualitative studies of ERP implementation, across a variety of care settings and geography.34,35 There are several published examples of ERP successes outside of specialty centers,9,10,36 but smaller hospitals have numerous challenges, including a lack of centralized department structure, low-volume surgeons with multiple hospital affiliations, and potential misalignment between hospital and surgeon incentives, all of which can inhibit ERP implementation.37

These and other challenges have motivated both the American College of Surgeons’ Enhanced Recovery in National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP)38 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Safety Program for Improving Surgical Care and Recovery,39 consortia that support the rollout of ERP and other care pathways in hospitals across the US. In a province-wide ERP implementation initiative among 15 academic hospitals in Ontario, Canada, key enablers of success were found to be coherence of clinical champions, relationship-building among stakeholders, and organizational prioritization.40 Whether ERPs were rolled out uniformly and sustainably in the settings evaluated in this study is unknown, and variability may have influenced their real-world effectiveness.

This study has several limitations that could limit generalizability of the findings. First, all hospitals in these registries participate in one or more statewide collaboratives. Participation in these programs has been associated with improvements in clinical and economic outcomes greater than those seen outside Michigan.41 Thus, the results in hospitals outside such collaboratives could differ. Second, although we performed detailed interviews to understand the status of ERP in each hospital, there was no audit of ERP implementation, and it is unknown whether individual patients were treated with an ERP around their operation. On the other hand, by not conditioning hospitals’ ERP status on protocol adherence, the study offers a real-world assessment of the effectiveness ERP dissemination, and evaluates the adoption of the protocol, rather the individual efficacy among patients selected for enhanced recovery practices. Recognizing that the fidelity of adoption likely varies widely between institutions, this approach provides the most realistic appraisal of what happens when hospitals outside select specialty centers take on the adoption of ERPs. Third, we did not account for the duration since ERP adoption, and therefore may be catching some hospitals during a “learning curve”. However, there were not enough patients to evaluate post-ERP adoption trends in outcome, and this may need to await results from the NSQIP enhanced recovery project. Fourth, all analyses are based on observational data, and the payment analyses are derived from administrative claims. It is unknown to what degree missing data, unmeasured confounding, or lack of clinical specificity might bias the conclusions. Finally, we lack measures of patient-centered outcomes, functional recovery, or societal costs beyond reimbursement from payers, and therefore cannot account for any ancillary effects of ERP on unmeasured outcomes.

In conclusion, adoption of enhanced recovery protocols was associated with a significant reduction in average postoperative length of stay in 24 Michigan hospitals that enacted protocols in recent years. There was no evidence that accelerated discharge was associated with increased readmissions or spending on care after discharge. The magnitude of benefit observed in this study is smaller than has been observed in studies from specialty institutions. This difference reflects a combination of factors, including consistency of protocol use across hospitals, but also reinforces the difference between uncontrolled pre/post evaluations of interventions and those that take account of background trends in surgical care independent of the intervention. Finally, recognizing that less than half of Michigan hospitals adopted ERPs, despite years of dissemination work within a statewide collaborative, further expansion of ERP to smaller, non-academic hospitals will require redoubled efforts at logistical and clinical support.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and Funding

The authors thank Emily George and Greta Krapohl, RN,PhD, for their work on the survey of hospital enhanced recovery practices.

Dr. Regenbogen was supported by the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Career Development Award CDG-015, National Institute on Aging Grants for Early Medical/Surgical Specialists Transition to Aging Research R03-AG047860, and National Institute on Aging K08-AG047252.

Dr. Regenbogen, Mr. Syrjamaki and Dr. Norton are supported by a contract from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, for the conduct of the Michigan Value Collaborative.

None of the funding agencies were involved in the analysis or interpretation of the data included, nor in the composition, critical review, or editing of the manuscript. Support for the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and Michigan Value Collaborative is provided by the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Value Partnerships program; however, the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect those of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan or any of its employees.

Footnotes

This manuscript was seen and approved by all authors.

References

- 1.Adamina M, Kehlet H, Tomlinson GA, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP. Enhanced recovery pathways optimize health outcomes and resource utilization: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in colorectal surgery. Surgery 2011;149:830–840. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg 2009;144:961–969. (In eng). DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ronellenfitsch U What are the effects of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) compared with conventional recovery strategies in people undergoing colorectal surgery? Cochrane Clinical Answers 2016;DOI: 10.1002/cca.545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhuang C-L, Ye X-Z, Zhang X-D, Chen B-C, Yu Z. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Programs Versus Traditional Care for Colorectal Surgery: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum 2013;56:667–678 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182812842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholson A, Lowe MC, Parker J, Lewis SR, Alderson P, Smith AF. Systematic review and meta-analysis of enhanced recovery programmes in surgical patients. Br J Surg 2014;101(3):172–88. (In eng). DOI: 10.1002/bjs.9394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH, Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 2010;29:434–440. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greco M, Capretti G, Beretta L, Gemma M, Pecorelli N, Braga M. Enhanced recovery program in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World journal of surgery 2014;38(6):1531–41. (In eng). DOI: 10.1007/s00268-013-2416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee L, Feldman LS. Improving Surgical Value and Culture Through Enhanced Recovery Programs. JAMA Surg 2017;152(3):299–300. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedrick TL, Thiele RH, Hassinger TE, et al. Multicenter Observational Study Examining the Implementation of Enhanced Recovery Within the Virginia Surgical Quality Collaborative in Patients Undergoing Elective Colectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2019;229(4):374–382.e3. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson G, Kiyang LN, Crumley ET, et al. Implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Across a Provincial Healthcare System: The ERAS Alberta Colorectal Surgery Experience. World journal of surgery 2016;40:1092–1103. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-016-3472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillissen F, Hoff C, Maessen JM, et al. Structured synchronous implementation of an enhanced recovery program in elective colonic surgery in 33 hospitals in The Netherlands. World journal of surgery 2013;37(5):1082–93. (In eng). DOI: 10.1007/s00268-013-1938-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springer JE, Doumouras AG, Lethbridge S, Forbes S, Eskicioglu C. A Provincial Assessment of the Barriers and Utilization of Enhanced Recovery After Colorectal Surgery. The Journal of surgical research 2019;235:521–528. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George E, Krapohl GL, Regenbogen SE. Population-based evaluation of implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol in Michigan. Surgery 2018;163(6):1189–1190. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berian JR, Ban KA, Liu JB, Ko CY, Feldman LS, Thacker JK. Adherence to Enhanced Recovery Protocols in NSQIP and Association With Colectomy Outcomes. Ann Surg 2019;269(3):486–493. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000002566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Group EC. The Impact of Enhanced Recovery Protocol Compliance on Elective Colorectal Cancer Resection: Results From an International Registry. Ann Surg 2015;261(6):1153–9. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pecorelli N, Hershorn O, Baldini G, et al. Impact of adherence to care pathway interventions on recovery following bowel resection within an established enhanced recovery program. Surg Endosc 2017;31(4):1760–1771. (In eng). DOI: 10.1007/s00464-016-5169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pisarska M, Pedziwiatr M, Malczak P, et al. Do we really need the full compliance with ERAS protocol in laparoscopic colorectal surgery? A prospective cohort study. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2016;36(Pt A):377–382. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Portinari M, Ascanelli S, Targa S, et al. Impact of a colorectal enhanced recovery program implementation on clinical outcomes and institutional costs: A prospective cohort study with retrospective control. International journal of surgery (London, England) 2018;53:206–213. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee L, Mata J, Ghitulescu GA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Enhanced Recovery Versus Conventional Perioperative Management for Colorectal Surgery. Ann Surg 2015;262(6):1026–33. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee L, Li C, Landry T, et al. A systematic review of economic evaluations of enhanced recovery pathways for colorectal surgery. Ann Surg 2014;259:670–6. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318295fef8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King PM, Blazeby JM, Ewings P, et al. The influence of an enhanced recovery programme on clinical outcomes, costs and quality of life after surgery for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:506–513. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regenbogen SE, Cain-Nielsen AH, Norton EC, Chen LM, Birkmeyer JD, Skinner JS. Costs and Consequences of Early Hospital Discharge After Major Inpatient Surgery in Older Adults. JAMA Surg 2017;152(5):e170123. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakobsen DH, Sonne E, Andreasen J, Kehlet H. Convalescence after colonic surgery with fast-track vs conventional care. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:683–687. (In eng). DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris M, Deierhoi R, Richman JS, et al. Measuring surgical complications as a quality metric: Looking beyond hospital discharge. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2012;215:S97–S98. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell DA Jr., Englesbe MJ, Kubus JJ, et al. Accelerating the pace of surgical quality improvement: the power of hospital collaboration. Arch Surg 2010;145:985–991. (In eng). DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottlieb D, Zhou W, Song Y, Andrews KG, Skinner J, Sutherland J. A standardized method for adjusting Medicare expenditures for regional differences in prices. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice. (http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/papers/std_prc_tech_report.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendren S, Morris AM, Zhang W, Dimick J. Early discharge and hospital readmission after colectomy for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:1362–1367. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822b72d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raval MV, Hamilton BH, Ingraham AM, Ko CY, Hall BL. The importance of assessing both inpatient and outpatient surgical quality. Ann Surg 2011;253:611–618. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318208fd50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilimoria KY, Cohen ME, Ingraham AM, et al. Effect of postdischarge morbidity and mortality on comparisons of hospital surgical quality. Ann Surg 2010;252:183–190. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e4846e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller DC, Gust C, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer N, Skinner J, Birkmeyer JD. Large variations in Medicare payments for surgery highlight savings potential from bundled payment programs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(11):2107–15. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen LM, Norton EC, Banerjee M, Regenbogen SE, Cain-Nielsen AH, Birkmeyer JD. Spending On Care After Surgery Driven By Choice Of Care Settings Instead Of Intensity Of Services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(1):83–90. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carey K Measuring the hospital length of stay/readmission cost trade-off under a bundled payment mechanism. Health economics 2015;24:790–802. (In eng). DOI: 10.1002/hec.3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frakt A The Hidden Financial Incentives Behind Your Shorter Hospital Stay. New York Times, The Upshot 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearsall EA, Meghji Z, Pitzul KB, et al. A qualitative study to understand the barriers and enablers in implementing an enhanced recovery after surgery program. Ann Surg 2015;261(1):92–6. (In eng). DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyon A, Solomon MJ, Harrison JD. A Qualitative Study Assessing the Barriers to Implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery. World journal of surgery 2014;38(6):1374–1380. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-013-2441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geltzeiler CB, Rotramel A, Wilson C, Deng L, Whiteford MH, Frankhouse J. Prospective Study of Colorectal Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in a Community Hospital. JAMA Surgery 2014;149(9):955–961. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayman A Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in Community Hospitals. The Surgical clinics of North America 2018;98(6):1233–1239. (In eng). DOI: 10.1016/j.suc.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berian JR, Ban KA, Liu JB, et al. Association of an Enhanced Recovery Pilot With Length of Stay in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. JAMA surgery 2018;153(4):358–365. (In eng). DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.AHRQ Safety Program for Improving Surgical Care and Recovery. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gotlib Conn L, McKenzie M, Pearsall EA, McLeod RS. Successful implementation of an enhanced recovery after surgery programme for elective colorectal surgery: a process evaluation of champions’ experiences. Implementation science : IS 2015;10:99. (In eng). DOI: 10.1186/s13012-015-0289-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Share DA, Campbell DA, Birkmeyer N, et al. How a regional collaborative of hospitals and physicians in Michigan cut costs and improved the quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:636–645. (In eng). DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.