Abstract

Peer coaching may provide a culturally relevant and potentially scalable approach for delivering postpartum obesity treatment. We aimed to evaluate the feasibility of peer coaching to promote postpartum weight loss among ethnic minority women with obesity. This pilot study was a prospective, parallel-arm, randomized controlled trial. Twenty-two obese, Black or Latina mothers ≤6 months postpartum were recruited from the Philadelphia Special Supplemental Nutrition Education Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and randomly assigned to either: (a) a peer-led weight loss intervention (n = 11) or (b) usual WIC care (n = 11). The intervention provided skills training and problem solving via six calls and two in-person visits with a Black mother trained in behavioral weight control strategies. Text messaging and Facebook served as platforms for self-monitoring, additional content, and interpersonal support. Both arms completed baseline and 14 week follow-up assessments. All participants were retained in the trial. Intervention engagement was high; the majority (55%) responded to at least 50% of the self-monitoring text prompts, and an average of 3.4 peer calls and 1.7 visits were completed. Mean weight loss among intervention participants was −1.4 ± 4.2 kg compared to a mean weight gain of 3.5 ± 6.0 kg in usual WIC care. Most intervention participants strongly agreed that the skills they learned were extremely useful (90%) and that the coach calls were extremely helpful for weight control (80%). Results suggest the feasibility of incorporating peer coaching into a postpartum weight loss intervention for ethnic minority women with obesity. Future research should examine the sustained impact in a larger trial.

Keywords: Peer coach, Postpartum, Weight loss, Obesity, Black, Latina

Implications.

Practice: As more attention is being paid to the dearth of postpartum health care for Black and Latina women, the addition of peer counselors may be a feasible and effective way to address postpartum obesity and improve healthy eating behaviors in low-income mothers at the Special Supplemental Nutrition Education Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC).

Policy: Federal and state policymakers may consider supporting health care legislation that includes funding allocations for peer-training and peer-led interventions for obesity treatment in the perinatal period, potentially as part of broader peer-based postpartum support services from perinatal community health workers/doulas.

Research: Further research is needed to refine the selection and training of peer health coaches and test the sustained impact of peer-led behavioral interventions for reducing cardiovascular disease risk through postpartum weight loss among a larger sample of Black and Latina women.

INTRODUCTION

The childbearing period is a critical life stage for excess weight gain and incident cardiometabolic disease [1–4], especially for the nearly three-quarters of Black and Latina women who enter pregnancy already overweight or obese [5]. These women may face particular challenges as they are at the highest risk for retaining weight at the end of the first postpartum year [1] and notably begin gaining weight after 4–6 weeks postpartum [6–9]. Small increases in maternal body mass indices result in a host of new perinatal complications in subsequent pregnancies (e.g., preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and fetal overgrowth), propagating a cycle of obesity and cardiometabolic disease from one generation to the next [10]. Efforts to promote postpartum weight loss have proven challenging, considering relatively few weight loss studies have included ethnic minority women. Even when “gold standard” approaches are used, less intervention engagement, higher attrition rates, and poorer postpartum weight loss outcomes among Black and Latina participants have been reported [11–15].

To remedy this evidence gap, our team of multidisciplinary researchers has spent the past half decade partnering with Black and Latina mothers, primarily those of lower socioeconomic position, to develop an innovative, theory- and evidence-based postpartum obesity treatment that: (a) creates an energy deficit sufficient to produce weight loss by focusing on simple, yet tailored, empirically supported obesogenic behavior change goals and (b) uses low-cost, mobile technologies (text messaging and social media) to deliver intervention content, promote social support, and allow for frequent yet convenient, interactive self-monitoring. To our knowledge, our 14 week randomized controlled trial (Healthy4Baby) testing this novel approach is one of only two studies that demonstrated significant weight loss among low-income, Black and Latina mothers [16,17]. Both interventions in these studies, however, were delivered as adjuncts to clinical care with behavior change counseling provided by experienced, bachelor’s level health coaches—limiting reach, cost, and scalability. A need exists to adapt and test interventions in “real-word” settings using interventionists with various training backgrounds in diverse target populations.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the feasibility of a peer-led adaptation of Healthy4Baby, evaluated in the “real-world” setting of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Education Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) of Philadelphia. We chose a peer-led approach because of its inherent cultural salience and potential for scalability, given its low costs relative to delivery by bachelor’s level professionals [18]. A robust literature exists about the efficacy of using peer coaches (e.g., those individuals who possess experiential knowledge of a specific behavior or stressor and similar characteristics as the target population, including race and culture) to deliver health promotion and disease prevention interventions [19–21]; however, no studies to our knowledge used this approach for delivering obesity treatment among Black women in the postpartum period, and only one investigation explored peer-led groups among Latina mothers for increasing physical activity but did not impact postpartum body fat [22]. While WIC has a well-established breastfeeding peer counseling program [23], peer coaches are not currently reaching WIC participants who are not breastfeeding, nor are they trained to coach women on diet and physical activity, critical topics that could be included if a peer-led adaptation of Healthy4Baby is found to be feasible and effective.

METHODS

Design and participants

This study was a prospective, parallel-arm, randomized, pilot feasibility trial of a 14 week, peer-led weight loss intervention compared to usual care. The trial was conducted in partnership with the Philadelphia County WIC program, the largest single-county WIC Program in Pennsylvania, which provides supplemental foods, nutrition education, access to health care, and referrals to health and human service programs for more than 55,000 socioeconomically disadvantaged families annually. The Temple University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures. All participants provided verbal consent, per IRB minimal risk guidelines, at their baseline visit.

From June to August 2015, research staff approached potential participants in the waiting room of WIC’s North Philadelphia clinic. Recruitment flyers explaining our voluntary research study, with a phone number to call for more information, were additionally placed in the waiting area. Interested mothers were screened for eligibility in person or over the phone. Eligibility criteria included: (a) age ≥18 years; (b) singleton infant delivered within the last 2 weeks to 6 months; (c) measured body mass index (BMI) between 30 and 50 kg/m2; (d) cell phone ownership with unlimited texting; (e) Philadelphia WIC recipient; (f) self-identification as Black or Latina; and (g) ability to speak, read, and write fluently in English. We additionally required that participants’ self-reported pre-pregnancy BMI was at least 30 kg/m2 because data suggest that pre-pregnancy obesity is a strong risk factor for weight retention following delivery [1]. We excluded mothers who smoked more than five cigarettes daily or had a medical condition/medications that affected weight status (e.g. diabetes, thyroid disease, prednisone use, gastrointestinal disorders, or disordered eating).

Eligible participants were invited to an in-person enrollment visit at our research offices on Temple University Health Science’s campus, less than 1 mile from WIC’s North Philadelphia clinic. At enrollment, participants were randomized 1:1 by computer-generated numbers in sealed envelopes to the peer-led intervention or usual WIC care. Study staff and the peer coach were blind to randomization until participants completed baseline assessments (anthropometrics and a survey of demographics, mood, food security, and health literacy).

Treatment groups

Peer-led intervention

The intervention was a peer-led adaption of Healthy4Baby, described more fully previously [16]. In brief, Healthy4Baby participants were assigned a set of six empirically supported behavior change goals (e.g., “Limit sugary drinks like juice and soda to no more than 1 per day”; “Limit junk and high fat foods to no more than 1 per day”; and “Walk 5,000 steps per day”), designed to create an energy deficit sufficient to produce weight loss. Goals were implemented one at a time, for 2–4 weeks, after a 15 min telephonic or in-person problem-solving session with a health coach. Interactive self-monitoring text messages (e.g., “Healthy4Baby Check-in: Please text us # cups of sugary drinks u had yesterday. Remember, 1 cup = 8 ounces.”) probed about goal adherence and a private Facebook group provided additional support and behavioral skills training tailored to the target population of low-income Black and Latina mothers. Facebook recipes, videos, and/or tips to increase exposure to weight-related skills were posted to the group one or two times weekly, with each participant having access to more than 20 study posts over the 14 week intervention. We chose to additionally incorporate Facebook because data suggest a strong link between social influence and healthy (or risky) behaviors, particularly among young adults, which we and others have leveraged through Facebook’s unique communication features (e.g., frequent messaging/posts to serve as a catalyst for behavioral modeling; reciprocal interactions through instant messaging; and/or Facebook “likes” for persuasion) [16,24–27].

In the current study, we used the same text messaging platform and Facebook protocol used in Healthy4Baby. However, we simplified our coach protocols from Healthy4Baby for ease of comprehension and delivery by a peer in this study. We hired a Black mother to deliver the intervention that: (a) completed the initial Healthy4Baby program and lost more than 5% of her initial body weight; (b) showed dedication to the community (e.g., worked as an Early Head Start counselor engaging mothers in North Philadelphia for more than 5 years); and (c) had natural leadership skills. Prior to implementing the study protocol with participants, she spent 20 hr training in behavioral weight control methods with a clinical psychologist (B.B.) on our study team using role-play and audio-taped protocol reviews. She additionally met for 1 hr weekly to twice monthly with study staff to discuss participant progress, assess fidelity through audio-taped protocol review, and troubleshoot any issues related to participant engagement or comprehension.

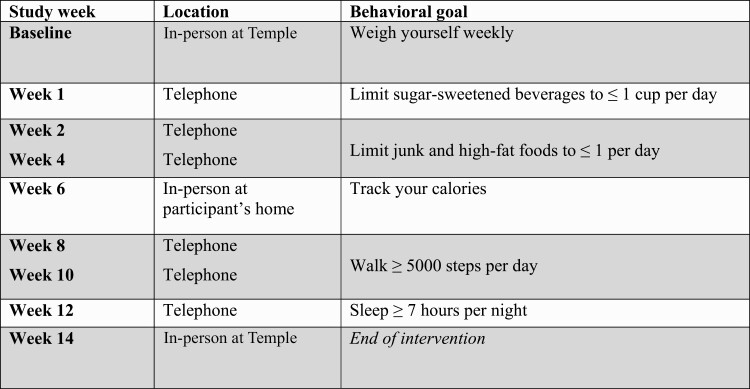

Similar to the schedule in Healthy4Baby, six calls and two in-person visits by the peer coach were planned (see Fig. 1 for schedule). Each call and/or visit followed a general structure that included: (a) evaluating participants’ progress achieving (or not achieving) the behavior change goal set in the previous session; (b) discussing what, why, and how of the next goal; and (c) problem-solving barriers/facilitators to achieving the next goal. While each session focused on a specific topic and included a scripted lesson plan, the coach also encouraged an interactive approach inviting participants to ask questions at any time during the session rather than waiting until the end. Because the second in-person visit was planned as a home visit in this study, hands-on learning techniques were encouraged, such as evaluating nutrition labels from foods in the participants’ homes or using calorie-tracking apps directly on their phones.

Fig 1.

Intervention schedule.

Usual WIC care

Participants randomized to usual care received the current standard of care offered to postpartum mothers at Philadelphia WIC community clinics, which included: (a) an initial visit within the first 10 days after delivery, at which time WIC providers assessed maternal/infant diet and medical history, counseled new mothers about infant feeding, and recommended referrals to health care and social services; (b) follow-up visits every 3–6 months, where providers assessed infant growth and offered nutrition education. All mothers received food/beverage vouchers at each WIC visit, designed to provide access to foods that are good sources of specific nutrients—protein, iron, calcium, and vitamins A and C. Study staff also provided brochures by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists about postpartum weight loss [28,29].

Measures

Feasibility outcomes included recruitment, retention, engagement (the later assessed at study completion by quantifying the number of coach calls and/or visits completed, number of text message self-monitoring responses received, and number of comments or “likes” to Facebook posts), along with participant satisfaction (measured using a survey adapted from Healthy4Baby that asked participants to rate their satisfaction with each intervention component, quantify the degree to which the program was helpful/useful in achieving weight loss goals, and answer one open-ended question about overall intervention experience). The trial also assessed change in body weight (kilograms) at 14 weeks postenrollment. Weight was measured without shoes in lightweight street clothing using a calibrated electronic scale to the nearest 0.1 kg (Detecto digital scale with 758C weight indicator; Detecto Scale Co, Webb City, MO). Additional outcomes included proportion achieving 3% weight loss from baseline and change in cardiovascular risk factors (specifically waist circumference and blood pressure) at 14 weeks postbaseline. Maternal waist circumference was measured by trained research staff to the nearest 0.1 cm using an anthropometric measuring tape on a horizontal plane at the iliac crest [30]. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured using an appropriately sized automatic blood pressure cuff by the OMRON HEM907XL device; two measurements (separated by 1 min intervals after 5 min of sitting) were obtained. All assessments were collected at baseline and 14 weeks after baseline in both groups. Participants were provided $50 at each assessment visit.

Information about participant demographics, weight perception, breastfeeding status, and psychosocial variables were collected at baseline via survey. We assessed mood using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which has high sensitivity (86%) and specificity (78%) for all forms of depression when compared to diagnostic clinical interviews. A score >12 indicates probable depression [31,32]. Food security was assessed with the short form of the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Model. Participants were categorized as food insecure if two or more questions were answered in the affirmative [33]. To evaluate health literacy, we queried participants at baseline using the short form of the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM-R), which has moderate evidence for validity using the Wide Range Achievement Test-Revised as the standard (r = .64) and demonstrated reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.91). We defined “at risk for poor health literacy” as a REALM-R score >6 [34].

As an exploratory analysis, we were additionally interested in evaluating whether gestational weight gain moderated intervention effects; we abstracted prenatal weights from participants’ medical records to calculate total gestational weight gain (last measured weight prior to delivery minus first weight measured in early pregnancy) using methods we have reported previously [35,36]. We categorized gestational weight gain as excessive based on the 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines (>9 kg in women with obesity) [3].

RESULTS

Participant recruitment and retention

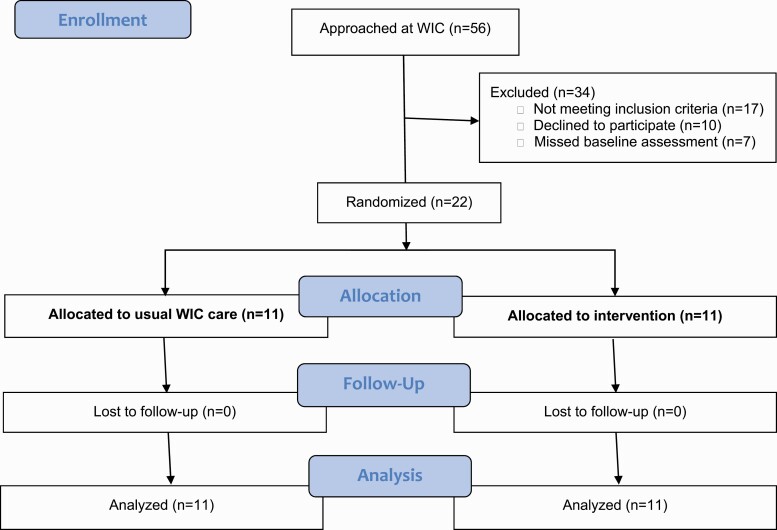

Figure 2 outlines the study enrollment and retention flow. A total of 22 participants were enrolled. One-hundred percent (22/22) were retained for their 14 week follow-up assessment visit and had their weight measured. Baseline participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Fig 2.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics

| Characteristic | Usual care (n = 11) | Intervention (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 26.3 ± 4.0 | 26.1 ± 4.3 |

| Baseline weight (kg) | 97.7 ± 17.3 | 99.1 ± 12.4 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 37.3 ± 5.9 | 38.2 ± 4.5 |

| Parity (live births) | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 0.8 |

| Single | 82% | 82% |

| Currently breastfeeding | 64% | 45% |

| Food insecure | 27% | 45% |

| Poor health literacy | 73% | 73% |

| Depressive symptoms | 18% | 27% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black Hispanic | 82% 18% | 91% 9% |

| Education | ||

| Some high school or less | 9% | 36% |

| High school graduate | 36% | 18% |

| Some college or more | 55% | 36% |

| Weight perception | ||

| Too heavy | 82% | 73% |

| About average | 18% | 27% |

| Too light | 0% | 0% |

| Gestational weight gain (kg)a | 11.9 ± 6.0 | 10.2 ± 8.7 |

| Exceeded IOM gestational weight gain guidelinesa | 57% | 70% |

| Weeks’ postpartum at baseline (weeks) | 9.7 ± 8.9 | 6.1 ± 6.1 |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables.

BMI body mass index; IOM Institute of Medicine.

aGestational weight gain data were unavailable for five participants (n = 4 usual care, n = 1 intervention).

Intervention engagement

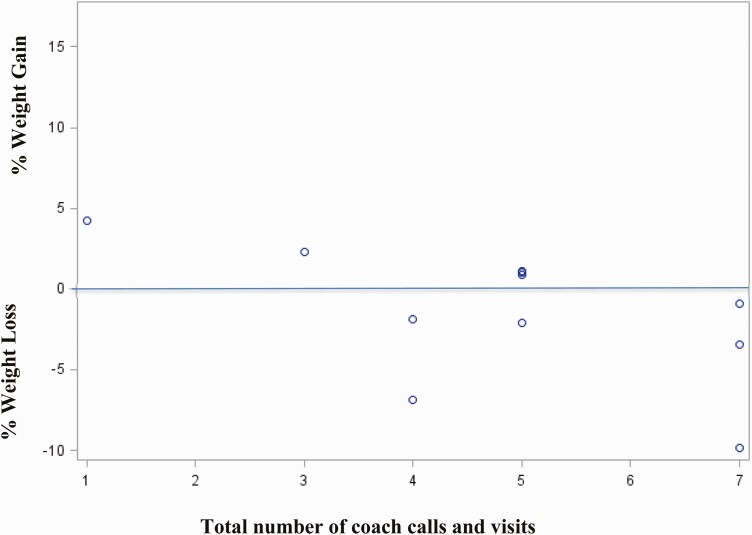

Intervention participants completed an average of 3.4 ± 1.1 calls (out of a possible 6 calls) and 1.7 ± 0.5 visits (out of a total of 2 visits). We observed a trend toward greater peer coach interaction being associated with greater weight loss (Fig. 3). Similar to the high degree of text message engagement in Healthy4Baby, we found that the mean frequency of self-monitoring texts per participant in this study was 32.4 ± 18.4 (expected texts = 57), and the majority of intervention participants (55%) responded to at least 50% of the self-monitoring text prompts. Nearly half (45%) of the intervention participants commented or “liked” at least one post on Facebook; however, the average number of comments or “likes” over the course of the study was low (2.3 ± 3.0 per participant) as each participant had access to over 20 posts.

Fig 3.

Scatterplot of peer coach calls/visits and percentage of weight loss.

Intervention satisfaction

At 14 weeks, most intervention participants strongly agreed (at least an 8 on a 10 point scale) that the skills they learned were extremely useful (90%); the coach calls were extremely helpful in promoting weight control (80%); and the treatment helped improve long-term weight control (90%). Only 2 of 11 found the Facebook group extremely useful (Facebook usefulness scores ranged from 2 to 10, with more than half below 5). Upon intervention completion, participant feedback to study staff included: (a) “The program has been very motivating. The coach and the different things that participants [are asked] to do are good” and (b) “I learned more self-control with eating.”

Weight change and cardiovascular risk factors

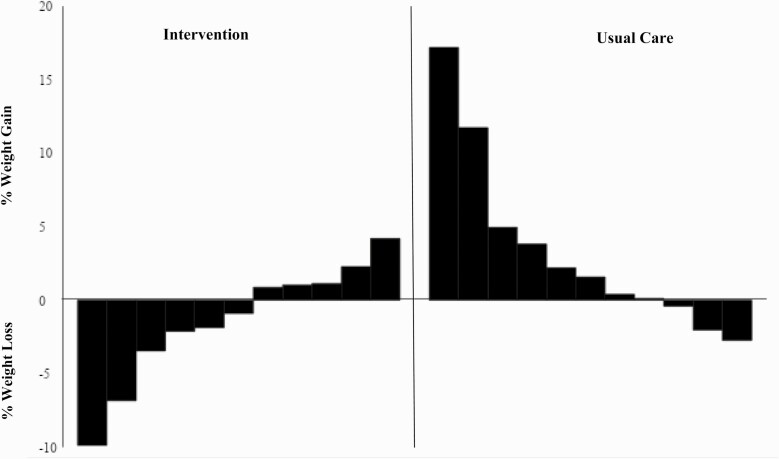

Table 2 highlights changes in weight and cardiovascular risk factors between study groups. Mean weight loss among intervention participants was −1.4 ± 4.2 kg compared to a mean weight gain of 3.5 ± 6.0 kg in usual care. This equates to a percentage of weight loss of −1.4 ± 4.2% in the intervention group, compared to a percentage of weight gain of 3.3 ± 6.1% in the usual care group (Fig. 4). Over one-quarter of intervention participants (27%) and no usual care participants lost at least 3% of their initial body weight by a 14 week follow-up. We did not find appreciable differences in exploratory analyses between treatment groups after stratification by gestational weight gain category.

Table 2.

Change in weight and cardiovascular risk factors

| Measure | Mean (SD) change | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n = 11) | Intervention (n = 11) | Difference, mean (SE) | |

| Weight, kg | 3.5 ± 6.0 | −1.4 ± 4.2 | 4.9 (2.2) |

| Percentage of weight loss, % | 3.3 ± 6.1 | −1.4 ± 4.2 | 4.8 (2.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | −1.1 ± 16.6 | 2.5 ± 15.5 | 3.6 (6.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 1.6 ± 8.2 | −1.1 ± 13.8 | 2.7 (4.8) |

| Waist circumference, cm | −2.7 ± 5.6 | −4.0 ± 5.5 | 1.3 (2.4) |

SD standard deviation; SE standard error.

Fig 4.

Percentage of weight change over 14 week follow-up by treatment group.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported our postpartum, technology-based obesity treatment (Healthy4Baby) promoted weight loss in a small sample of socioeconomically disadvantaged Black mothers after childbirth [16]. In this study, we found that the addition of peer coaching to the Healthy4Baby program for support and skills training was both feasible and positively perceived. Our pilot promoted weight loss among intervention participants but, more importantly, prevented the more than 3 kg of weight gain experienced by our usual care group. These results suggest that incorporating peer coaching into a technology-based intervention may provide a viable and potentially lower-cost approach to promoting weight loss in the postpartum period among populations at the highest risk for weight gain.

Peer relations are particularly salient during young adulthood [37,38]. Integrating peers into interventions for interpersonal counseling support improves a variety of health-related outcomes by altering social norms and offering hope, companionship, and encouragement to others facing similar challenges [39]. Sharing a common culture, language, and lived experience allows peer counselors (also referred to as “lay health advisors,” “promotores,” or “community health workers”) to build trust and credibility, equalize power dynamics, normalize challenges of literacy and accountability, and ensure access to care, while at the same time lower costs—the latter of which is related to cost savings generated by using peer-based approaches [40,41]. Engagement in calls and home visits was high in our study, perhaps in part because the use of a peer provided an asset-based approach to counseling (e.g., focusing on what participants value most based on shared lived experiences). More work is needed in partnership with WIC to develop and test avenues for the potential inclusion of diet and physical activity counseling by current peer counselors, enhanced with our technology-based program, to offer personal experience and credibility and emotional and instrumental support, as well as effective postnatal obesity treatment.

We did not find the addition of a Facebook group in this study to be particularly useful for the majority of intervention participants. Engagement was low in this study compared to that of other postpartum weight loss interventions delivered via Facebook [24,25]. However, we did not require that participants were active users of Facebook at enrollment, defined in other studies as logging in and/or posting at least once per week [24,25] and thus, we may have had lower utilization. Facebook was not the primary modality for participant support and content in our study, and participants did not provide input about preferences related to content posted in the group, both of which may have additionally factored into Facebook’s limited engagement and lower acceptability.

While the mean weight loss in the intervention group may appear modest (−1.4 kg), the intervention prevented the more than 3 kg of weight gain observed among usual care participants. High weight gains in the first year after childbirth are particularly common for socioeconomically disadvantaged racial/ethnic minorities [12], weight gains that have been linked to incident diabetes, obesity/extreme obesity, and poorer outcomes in subsequent pregnancies [4,10,42]. Thus, solely preventing weight gain in this high-risk population is of major value, particularly when using inexpensive mHealth technologies and peer coaches to enhance accessibility and scalability as we did. Future research is needed to assess the effect of the intervention on longer-term changes in weight and cardiovascular risk.

Several considerations limit the interpretations drawn from this study. Our sample size was small and limited to a single Philadelphia WIC community clinic, which impacts the generalizability of the findings. Because of the pilot nature of this trial, sample size was determined based on peer coach availability. Furthermore, our small sample size and missing prenatal records for several of our participants may have limited our statistical power to detect differences by treatment group or effect modification by gestational weight gain. While we did not have a Latina peer coach for our Latina mothers, satisfaction scores were high and similar among both Black and Latina participants, with 100% retention through the 14 weeks. However, given benefits in the literature of racially concordant care [20,41], future studies that match Latina mothers with a Latina peer coach may enhance weight loss and acceptability. Finally, the weight loss achieved in this study was somewhat less than we found in our original Healthy4Baby trial; differences in study populations, such as the inclusion of heavier mothers who were not required to retain at least 5 kg before study entry in this trial, may explain this discrepancy.

Despite these limitations, our pilot study has yielded important findings about the feasibility of a peer-led approach for reducing cardiovascular disease risk through postpartum weight loss among ethnic minority women with obesity. There is a growing awareness of the need for more and better postpartum care and services for all women, but especially for Black women, who face an enormous crisis of maternal mortality and morbidity [43]. This is coupled with widespread recognition of the negative health impacts of racism and the implicit bias of providers on perinatal outcomes, which can be further exacerbated when there is a lack of racial congruence or shared lived experience between patients and providers, propagated in part by the overall lack of racial diversity in the current perinatal workforce [44,45]. Whether as an essential component of postpartum obesity treatment like in this pilot program or as a vital part of a more comprehensive perinatal community health worker/doula program offering support in a range of areas throughout both pregnancy and the postpartum period, peer-based interventions and support for low-income women of color are of increasing importance for mitigating perinatal racial health disparities.

Acknowledgments

We would especially like to thank Teeah Mccall who coached participants in the intervention arm of this study along with Jane Cruice, RN, Gary Foster, PhD, Gary Bennett, PhD, and Adam Davey, PhD, who helped develop and evaluate our original Healthy4Baby intervention.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL130816. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: Currently, V.M.B. is a consultant for Do It Better Wellness and the owner of LoveLife Nutrition and Wellness, LLC, neither of which has provided financial support for this study, nor did they have any influence on the methods in this study. C.M.S. is the owner of Motherland Midwifery, LLC, and S.J.M. is the owner and CEO of Oshun Family Center, work that is not directly related to this study. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions:

S.J.H., V.M.B., and B.B. designed the study and performed the research. S.J.H., V.M.B., C.S., S.J.M., and L.M.K. made scientific contributions to the analysis and interpretation of the data. S.J.H., V.M.B., and C.S. wrote the paper. All authors had final approval of the submitted paper.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Temple University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: All individual participants provided verbal consent, per IRB minimal risk guidelines, at their baseline visit.

References

- 1. Gore SA, Brown DM, West DS. The role of postpartum weight retention in obesity among women: A review of the evidence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davis EM, Zyzanski SJ, Olson CM, Stange KC, Horwitz RI. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences in the incidence of obesity related to childbirth. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):294–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Institute of Medicine. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kew S, Ye C, Hanley AJ, et al. Cardiometabolic implications of postpartum weight changes in the first year after delivery. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(7):1998–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lederman SA, Alfasi G, Deckelbaum RJ. Pregnancy-associated obesity in black women in New York City. Matern Child Health J. 2002;6(1):37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walker LO. Low-income women’s reproductive weight patterns. Empirically based clusters of prepregnant, gestational, and postpartum weights. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19(6):398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Østbye T, Peterson BL, Krause KM, Swamy GK, Lovelady CA. Predictors of postpartum weight change among overweight and obese women: Results from the Active Mothers Postpartum study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(2):215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gunderson EP, Abrams B, Selvin S. Does the pattern of postpartum weight change differ according to pregravid body size? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(6):853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Interpregnancy weight change and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1164–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Østbye T, Krause KM, Lovelady CA, et al. Active mothers postpartum: A randomized controlled weight-loss intervention trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(3):173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Walker LO, Sterling BS, Latimer L, Kim SH, Garcia AA, Fowles ER. Ethnic-specific weight-loss interventions for low-income postpartum women: Findings and lessons. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(5):654–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krummel D, Semmens E, MacBride AM, Fisher B. Lessons learned from the mothers’ overweight management study in 4 West Virginia WIC offices. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42(3 Suppl):S52–S58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chang MW, Brown R, Nitzke S. Results and lessons learned from a prevention of weight gain program for low-income overweight and obese young mothers: Mothers in Motion. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilmore LA, Klempel MC, Martin CK, et al. Personalized mobile health intervention for health and weight loss in postpartum women receiving women, infants, and children benefit: A randomized controlled pilot study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(7):719–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herring SJ, Cruice JF, Bennett GG, Davey A, Foster GD. Using technology to promote postpartum weight loss in urban, low-income mothers: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(6):610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Phelan S, Hagobian T, Brannen A, et al. Effect of an internet-based program on weight loss for low-income postpartum women: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2381–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldman ML, Ghorob A, Eyre SL, Bodenheimer T. How do peer coaches improve diabetes care for low-income patients?: A qualitative analysis. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(6):800–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eng E, Smith J. Natural helping functions of lay health advisors in breast cancer education. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1995;35(1):23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andrews JO, Felton G, Wewers ME, Heath J. Use of community health workers in research with ethnic minority women. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36(4):358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pérez-Escamilla R, Hromi-Fiedler A, Vega-López S, Bermúdez-Millán A, Segura-Pérez S. Impact of peer nutrition education on dietary behaviors and health outcomes among Latinos: A systematic literature review. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40(4):208–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keller C, Ainsworth B, Records K, et al. A comparison of a social support physical activity intervention in weight management among post-partum Latinas. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Collins A, Rappaport CD, Burstein N. WIC Breastfeeding Peer Counseling Study, Final Implementation Report, WIC-10-BPC. Alexandria, VA: Office of Research and Analysis, Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silfee VJ, Lopez-Cepero A, Lemon SC, et al. Adapting a behavioral weight loss intervention for delivery via Facebook: A pilot series among low-income postpartum women. JMIR Form Res. 2018;2(2):e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waring ME, Moore Simas TA, Oleski J, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of delivering a postpartum weight loss intervention via Facebook: A pilot study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50(1):70–74.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silfee VJ, Lopez-Cepero A, Lemon SC, Estabrook B, Nguyen O, Rosal MC. Recruiting low-income postpartum women into two weight loss interventions: In-person versus Facebook delivery. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(1):129–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim SJ, Marsch LA, Brunette MF, Dallery J. Harnessing Facebook for smoking reduction and cessation interventions: Facebook user engagement and social support predict smoking reduction. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(5):e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Frequently asked questions: Getting in shape after your baby is born. 2011. Available at http://www.acog.org/~/media/ForPatients/faq131.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20140327T1451433365. Accessed 5 February 2015.

- 29. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Weight control: Eating right and keeping fit.FAQ064: Women’s Health.2013. Available at https://www.acog.org/~/media/For%20Patients/. Accessed 5 February 2015.

- 30. Centers for Disease Control. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Anthropometry procedures manual. 2007. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_07_08/manual_an.pdf. Accessed 5 February 2015.

- 31. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale detection of postnatal depression development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;150:782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Matthey S, Henshaw C, Elliott S, Barnett B. Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Implications for clinical and research practice. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(6):309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, Briefel RR. The effectiveness of a short form of the household food security scale. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8):1231–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bass PF III, Wilson JF, Griffith CH. A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1036–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herring SJ, Nelson DB, Davey A, et al. Determinants of excessive gestational weight gain in urban, low-income women. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(5):e439–e446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Herring SJ, Cruice JF, Bennett GG, Rose MZ, Davey A, Foster GD. Preventing excessive gestational weight gain among African American women: A randomized clinical trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(1):30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Albert D, Chein J, Steinberg L. Peer influences on adolescent decision making. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(2):114–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leahey TM, Gokee LaRose J, Fava JL, Wing RR. Social influences are associated with BMI and weight loss intentions in young adults. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(6):1157–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Community Preventive Services Task Force T. Using evidence to improve health outcomes: Annual report to Congress, federal agencies, and prevention stakeholders.2016. Available at www.thecommunityguide.org. Accessed 12 January 2020.

- 40. Vaughan K, Kok MC, Witter S, Dieleman M. Costs and cost-effectiveness of community health workers: Evidence from a literature review. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fleury J, Keller C, Perez A, Lee SM. The role of lay health advisors in cardiovascular risk reduction: A review. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;44(1–2):28–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rooney BL, Schauberger CW, Mathiason MA. Impact of perinatal weight change on long-term obesity and obesity-related illnesses. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1349–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Flanders-Stepans MB. Alarming racial differences in maternal mortality. J Perinat Educ. 2000;9(2):50–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Prather C, Fuller TR, Jeffries WL IV, et al. Racism, African American women, and their sexual and reproductive health: A review of historical and contemporary evidence and implications for health equity. Health Equity. 2018;2(1):249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Serbin JW, Donnelly E. The impact of racism and midwifery’s lack of racial diversity: A literature review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61(6):694–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]