Abstract

Aims

To estimate change in young people's alcohol consumption during COVID‐19 restrictions in Australia in early‐mid 2020, and test whether those changes were consistent by gender and level of consumption prior to the pandemic.

Design

Prospective longitudinal cohort.

Setting

Secondary schools in New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia.

Participants

Subsample of a cohort (n = 443) recruited in the first year of secondary school in 2010–11. Analysis data included three waves collected in September 2017–July 2018, September 2018–May 2019 and August 2019–January 2020), and in May–June 2020.

Measurements

The primary predictors were time, gender and level of consumption prior to the pandemic. Outcome variables, analysed by mixed‐effects models, included frequency and typical quantity of alcohol consumption, binge drinking, peak consumption, alcohol‐related harm and drinking contexts.

Findings

Overall consumption (frequency × quantity) during the restrictions declined by 17% [incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 0.83; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.73, 0.95] compared to February 2020, and there was a 35% decline in the rate of alcohol‐related harms in the same period (IRR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.54, 0.79). Changes in alcohol consumption were largely consistent by gender.

Conclusions

From a survey of secondary school students in Australia, there is evidence for a reduction in overall consumption and related harms during the COVID‐19 restrictions.

Keywords: Alcohol; COVID‐19; epidemiology, prospective cohort; public health, young adults

Introduction

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had consequences beyond disease morbidity and mortality, with social and travel restrictions imposed world‐wide. There are questions regarding the impact of COVID‐19 on alcohol. Restrictions on gatherings could result in declining consumption within social contexts [1, 2, 3]. Conversely, the pandemic and related restrictions have generated financial and psychological distress for many Australians [4]: known risk factors for elevated alcohol consumption [5]. Further, some governments have temporarily relaxed liquor licensing restrictions, facilitating on‐line purchasing and home delivery [1].

Financial analyses showed increased alcohol purchasing in Australia in March 2020 when restrictions were implemented [6], although industry reported declines in total alcohol volume sold [1, 7]. Similarly, wastewater analysis showed a decline in alcohol consumption during initial COVID‐19 restrictions in Adelaide, Australia [8]. By contrast, survey research from Australia and other countries suggest that the majority of adults perceived their alcohol use as stable since COVID‐19 restrictions [9, 10, 11]. Other Australian research indicated that self‐reported alcohol consumption may be elevated relative to benchmark data collected before COVID‐19 restrictions [12]. However, research to date largely does not account for pre‐COVID‐19 levels of alcohol use, highlighting the necessity for prospective, longitudinal data comparing alcohol consumption patterns before and after COVID‐19 restrictions.

Alcohol use is very common among young adults in Australia: 18–24‐year‐olds typically report the highest rates of drinking, binge drinking and alcohol‐related harms of all Australians [13]. There is evidence of an ongoing decline in consumption overall among young Australians [13]; however, it is not clear whether this trend has been impacted by the COVID‐19 pandemic. Young adults are typically less financially stable [14] than older adults, and over‐represented in service industries which have been particularly impacted by COVID‐19 restrictions [9]. Thus, restrictions may have disproportionately impacted younger people. Conversely, young people tend to consume more alcohol outside the home [15] than older adults, so consumption may have declined with restrictions preventing gatherings.

Emerging research also suggests gender differences in the response to the COVID‐19 pandemic and associated restrictions. Men in the United States were more likely to drink following restrictions than women, but their drinking was largely unaffected by stress caused by the pandemic [16]. Australian research [17] also found gender differences in alcohol use, mediated by other factors such as employment, exercise, diet and sleep. However, that study occurred early in the pandemic, when stress from isolation and economic factors may not have fully emerged.

This study used data from the Australian Parental Supply of Alcohol Longitudinal Study (APSALS) to investigate changes in alcohol consumption among young adults in May to June 2020 (i.e. after the implementation of restrictions and the first wave of the pandemic in Australia had peaked in late March), relative to consumption before March 2020. Specifically, we aimed to: (1) evaluate changes in alcohol consumption and harm, compared with pre‐COVID‐19; (2) test whether changes in alcohol consumption and harm were consistent in men and women; and (3) test whether changes in alcohol consumption and harm were consistent across levels of alcohol consumption prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic. We also explored drivers for change in alcohol consumption.

Methods

Sample

We used the APSALS cohort (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02280551) of 1927 families [18]. Participants and a parent/guardian were recruited via an opt‐in process in 2010 and 2011 from grade 7 classes (mean age 12.9 years) in Australian schools across three jurisdictions (New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia), with signed consent obtained from parents. The target sample was n ~ 1800 [18]. Participants completed annual surveys, with parents/guardians surveyed until wave 5. Participants were reimbursed for survey completion ($AUD20 for wave 8; $AUD50 for waves 9/10) and could enter a draw to win one of eight $AUD500 vouchers. Response rates for each wave are presented in Supporting information, Appendix B.

Wave 10 data collection was under way when the first COVID‐19 fatality was recorded in Australia on 15 March 2020 and social distancing restrictions came into effect in late March. We invited participants who had completed wave 10 up to April 30 and had provided an e‐mail address to complete a 10‐minute online survey via Qualtrics assessing alcohol use, other substance use, mental and physical health during COVID‐19 restrictions (hereafter ‘COVID‐19 survey’). Participants could win a $AUD500 gift voucher. Of 813 participants invited, 443 completed COVID‐19 surveys (54% response rate) between 18 May and 25 June 2020 (see Supporting information, Appendix A for time‐line of data collection and the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia and Supporting information, Appendix B for study flow‐chart).

The study was approved by the UNSW Sydney Research Ethics Committee and ratified by the universities of Tasmania, Newcastle and Queensland and Curtin University. Findings are reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement (Supporting information, Appendix B).

Measures

Outcome variables

Five prospective outcome measures were used in addition to retrospective outcomes assessed in the COVID‐19 survey. Further details of the measures are shown in Supporting information, Appendix C.

Frequency of use

Participants were asked how often they consumed alcohol. In the COVID‐19 survey, participants were asked first about the month of February, and then about the past month (not at all, 1 day/month, 2–3 days/month, 1–2 days/week, 3–4 days/week, 5–6 days/week or daily). In the APSALS annual survey they were asked about the past year (daily, 5–6 days/week, 3–4 days/week, 1–2 days/week, 2–3 days/month, 1 day/month, less often or never). This was pro‐rated to past month use (see Supporting information, Appendix C for details).

Typical quantity consumed

Participants who reported any alcohol consumption were asked how many standard drinks (equivalent to 10 g of alcohol) they typically consumed on a drinking occasion, with categorical responses in waves 8–10 (none; a sip or a taste; one to two drinks; three to four drinks; five to siz drinks; seven to 10 drinks; 11–12 drinks; or 13 or more drinks) and a continuous response in the COVID‐19 survey, which was coded to the same categories as the waves 8–10 data. To limit impossibly high responses without making assumptions about maximum levels of consumption, the continuous response was capped at 100 drinks.

Frequency of binge drinking

Participants who reported any alcohol consumption were asked how often they consumed ≥ 5 standard drinks, with the same response options as for frequency of use. Responses in the annual APSALS surveys were pro‐rated to the past month (Supporting information, Table C2).

Overall consumption

We multiplied frequency of use and typical quantity consumed at each time‐point to create a proxy for overall consumption of alcohol in the month [19].

Maximum consumption

Those who reported any alcohol consumption in the COVID‐19 survey were asked the maximum number of standard drinks they consumed on a single occasion in the past month and in February 2020.

Alcohol‐related harms

The COVID‐19 survey included a subset of the harms from the School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project (SHAHRP) scale [20] (range = 0–8; see Supporting information, Appendix C for list of items).

Drinking contexts

The COVID‐19 survey included questions about time spent drinking alone, physically with others or virtually with others, coded as the proportion of time drinking from 0 to 100.

Use of delivery services

Participants were asked in the COVID‐19 survey how often they had alcohol delivered to their home, coded as a binary (no/yes) variable of any use of alcohol delivery services.

Self‐reported change in alcohol use

Participants were asked to self‐report whether their alcohol use had changed since the COVID‐19 restrictions commenced in March. Those reporting increased or decreased consumption were asked to select from a list of possible reasons why the change occurred (with multiple selections possible; Table 1).

Table 1.

Total number of harms, report of any alcohol‐related harms and report of individual alcohol‐related harms, prior to and during the COVID‐19 restrictions.

| Alcohol‐related harms | February 2020 | May–June 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of harms (mean/SD) | 0.70 (0.05) | 0.47 (0.04) |

| Reported any harms | 36.8% | 26.2% |

| Individual harms | ||

| Were sick after drinking | 16.0% | 10.8% |

| Had a hangover | 33.9% | 24.6% |

| Were unable to remember what happened | 13.1% | 7.4% |

| Got into a physical fight | 0.9% | 0.5% |

| Damaged something | 1.6% | 2.3% |

| Got into trouble with friends | 1.4% | 0.9% |

| Had sex that they later regretted | 2.9% | 0.5% |

| Had an accident, injury or fall | 1.8% | 1.6% |

Total number of harms is calculated as the total number of individual harms experienced. Information on harms in February 2020 was obtained in the COVID‐19 survey conducted in May–June 2020. Results are based on multiple imputation with estimates combined using Rubin's rules. SD = standard deviation.

Predictors

The primary predictor was time to assess changes before and during the COVID‐19 restrictions. The primary time variable was a categorical variable with five time‐periods: wave 8 (September 2017–July 2018), wave 9 (September 2018–May 2019), wave 10 (August 2019–January 2020), COVID‐19 survey pre‐restrictions (February 2020; reported retrospectively) and COVID‐19 survey post‐restrictions (May–June 2020). For sensitivity analyses we coded the quarter and year in which the survey was completed (or to which data referred to). We also coded a binary variable of alcohol consumption in wave 8 (above or below/equal to the median for consumption).

Other variables

Participants were asked about their experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic, including whether they had been tested for/diagnosed with the disease, and a range of other potential impacts, such as being required to quarantine or losing employment. Further details are available in Supporting information, Appendix C.

Statistical analysis

We included a range of socio‐demographic characteristics of the sample, with means and standard deviations (for continuous measures and ns and percentages for categorical measures. We compared the characteristics of participants who completed the COVID‐19 survey to all participants who completed ASPALS wave 8, with t‐tests and χ2 tests to assess differences between responders and non‐responders (including those not invited to the COVID‐19 survey). We reported descriptive statistics on alcohol consumption of participants over time. We compared the subjective report of change in alcohol use to a measure of change derived from change in overall consumption between February 2020 and May–June 2020.

We conducted analyses of change in alcohol use using mixed effects models to control for repeated observations for each participant. Primary analyses were conducted using negative binomial regression, with results reported as incidence rate ratios (IRRs). Because the primary difference of interest was with alcohol use immediately prior to the pandemic, we used February 2020 (or quarter 1, 2020 for analyses using calendar time) as the referent in all analyses. Although participants who completed wave 10 up to April 30 were invited to participate in the COVID‐19 survey, to maintain separation between the wave 10 data and the COVID‐19 restrictions only wave 10 responses to the end of January 2020 were included.

We analysed alcohol outcomes that were only asked in the COVID‐19 survey with mixed‐effects models across two time‐periods (February 2020 and May–June 2020) using linear regression (maximum consumption and drinking contexts), negative binomial regression (alcohol‐related harms) and logistic regression (use of delivery services). Results were reported as changes in mean, IRRs and odds ratios (ORs), respectively.

To examine whether changes over time differed by gender, we reconducted all models with a gender × time interaction effect. Two participants identified as a gender other than male or female and were excluded from all analyses. To examine whether changes differed as a function of the amount of alcohol consumed, we conducted secondary analyses using an interaction between time and wave 8 consumption. As a post‐hoc sensitivity analysis, we conducted an analysis based on Australian government guidelines [21], with participants classified based on reported binge drinking more than once in the month or heavy drinking (10+ drinks per week) at wave 8.

We conducted sensitivity analyses with time considered as continuous, grouped into years/quarters (e.g. quarter 1, 2020) rather than split categorically into waves. Another sensitivity analysis was conducted using the same continuous time measure, but excluding the retrospective data collected concerning February 2020. For both sensitivity analyses, all wave 10 data up to 30 April 2020 were included.

All regression models controlled for confounding, using waves 1 and 8 variables. The confounding variables included: child gender and age [22, 23], socio‐economic status of area of residence [24], family history of alcohol problems [25], having older siblings [22] and peer substance use and disapproval of alcohol and tobacco use [22, 23, 25]. More details on the confounding variables are included in Supporting information, Appendix C. Analysis was conducted using the ‘mi’ commands and mixed effects models (mixed, meologit, menbreg) in Stata version 16.1 [26]. We used a critical P‐value of P < 0.05, and all results of inferential statistics are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The analysis code is available at https://www.philipclare.com/code/apsals/. The specific analyses in this study were not pre‐registered and should be considered exploratory.

Missing data

To reduce the chance of bias due to missing data, we used multiple imputation, implemented using the R package ‘mice’ [27] and combined using the package ‘Amelia’ [28] in R version 4.0.3 [29]. Further details of missing data and the imputation are included in Supporting information, Appendix D.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants who completed the COVID‐19 survey (n = 443) largely recruited from Tasmania (37.5%), Western Australia (26.9%) and New South Wales (25.7%) (Supporting information, Table E1). The COVID‐19 sample was broadly similar to the APSALS cohort, although there was a higher proportion of women (60.8 compared with 49.3%, respectively; Table 2). The COVID‐19 sample also came from slightly more educated (44.0% of parents with university education versus 36.3%) and religious (34.2% of parents' religious versus 29.5%) backgrounds (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of sociodemographic characteristics of the COVID‐19 survey subsample to full sample of all those who completed Wave 8

| Full sample, Wave 8 | COVID Survey Subsample | Statistic; p‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean monthly alcohol consumption (SD) | 18.7 (19.8) | 17.5 (19.7) | t(913)=1.13; p=0.258 | |

| Mean age (SD) | 19.8 (0.5) | 19.7 (0.5) | t(842)=1.18; p=0.239 | |

| Gender | Male | 49.3% | 38.6% | χ2(1)=27.75; p=0.000 |

| Female | 50.7% | 61.4% | ||

| Income | $1‐$12,999 | 42.8% | 46.6% | χ2(3)=3.82; p=0.281 |

| $13,000‐$31,199 | 39.8% | 38.1% | ||

| $31,200‐$67,599 | 15.8% | 14.0% | ||

| $67,600+ | 1.5% | 1.3% | ||

| Single parent household | No | 62.8% | 64.4% | χ2(1)=0.57; p=0.449 |

| Yes | 37.2% | 35.6% | ||

| Older siblings | No | 48.1% | 48.5% | χ2(1)=0.02; p=0.888 |

| Yes | 51.9% | 51.5% | ||

| Parent born in Australia | No | 26.5% | 27.9% | χ2(1)=0.50; p=0.481 |

| Yes | 73.5% | 72.1% | ||

| Parent education | High school or less | 31.7% | 26.3% | χ2(2)=15.77; p=0.000 |

| Diploma, Trade, non‐trade | 32.1% | 29.7% | ||

| University degree | 36.3% | 44.0% | ||

| Parent religiosity | Not/a little | 70.5% | 65.8% | χ2(1)=6.04; p=0.014 |

| Pretty/very | 29.5% | 34.2% | ||

| Parent employment | Employed (full‐time/part‐time) | 81.1% | 83.4% | χ2(2)=2.30; p=0.317 |

| Unemployed ‐ in workforce | 12.5% | 11.3% | ||

| Unemployed ‐ not in workforce | 6.4% | 5.2% | ||

| Mean parent demandingness (SD) | 23.7 (3.7) | 23.7 (3.5) | t(775)=‐0.01; p=0.993 | |

| Mean parent responsiveness (SD) | 29.7 (4.3) | 29.8 (4.3) | t(739)=‐0.48; p=0.631 | |

| SEIFA | Low | 17.3% | 13.8% | χ2(2)=5.57; p=0.062 |

| Medium | 21.9% | 21.3% | ||

| High | 60.8% | 64.9% | ||

| Family history of alcohol problems | No | 51.1% | 54.6% | χ2(1)=2.57; p=0.109 |

| Yes | 48.9% | 45.4% | ||

| Mean peer substance use (SD) | 14.7 (4.3) | 14.4 (4.1) | t(884)=1.48; p=0.140 | |

| Mean peer disapproval of substance use (SD) | 2.6 (1.8) | 2.8 (1.8) | t(817)=‐1.92; p=0.055 | |

Six per cent of COVID‐19 survey respondents reported having been tested for SARS‐CoV‐2, and one participant reported having received a positive test result. Three‐quarters (74%) reported voluntary home isolation (i.e. only leaving their primary residence for government‐specified essential reasons, including grocery shopping and medical appointments), and one in 10 (9%) reported that they had been in quarantine (i.e. at risk of contracting COVID‐19 and required to quarantine for 14 days). Further details of restrictions during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia are included in Supporting information, Appendix A [30]. There was relatively little concern about COVID‐19 itself, with 17% reporting that they were at least moderately worried about contracting the disease.

Alcohol use

Between 76.6 and 85.4% of respondents reported consuming alcohol in each period from September 2017 to June 2020 (Table 3), while 50.0–64.7% reported binge drinking.

Table 3.

Raw trends in frequency of alcohol consumption, typical consumption and binge drinking reported by the sample over the five waves of the study.

| September 2017–July 2018 | September 2018–May 2019 | August 2019–January 2020 | February 2020 | May–June 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | None | 23.4% | 21.9% | 21.1% | 14.6% | 21.8% |

| Yes: less than weekly | 46.5% | 46.9% | 41.4% | 48.6% | 42.3% | |

| Yes: at least weekly | 30.1% | 31.2% | 37.5% | 36.8% | 35.9% | |

| Typical consumption | None | 23.4% | 21.9% | 21.1% | 14.7% | 21.8% |

| Up to four standard drinks | 31.0% | 35.0% | 46.3% | 53.3% | 60.3% | |

| 5 or more standard drinks | 45.5% | 43.1% | 32.6% | 32.0% | 17.9% | |

| Binge drinking | None | 40.3% | 42.0% | 45.7% | 35.3% | 50.0% |

| Yes: less than weekly | 43.4% | 43.3% | 36.9% | 50.6% | 40.8% | |

| Yes: at least weekly | 16.2% | 14.7% | 17.5% | 14.1% | 9.2% |

Results are based on multiple imputation with estimates combined using Rubin's rules.

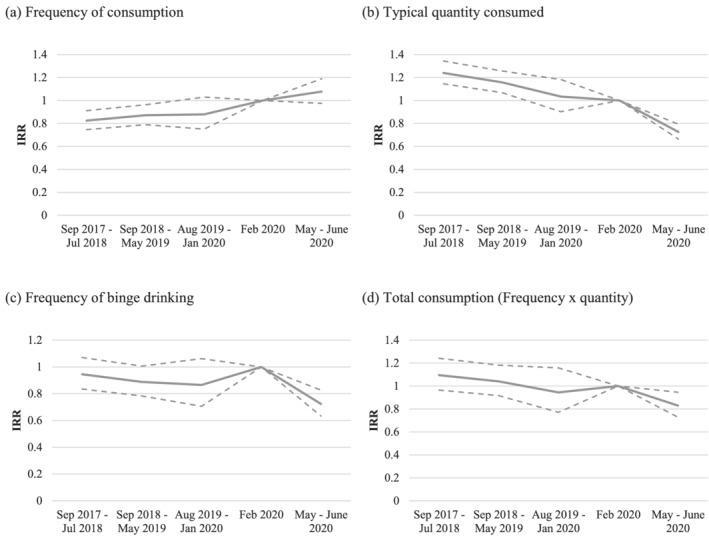

There was evidence of increased frequency of consumption which did not abate during the pandemic, with frequency of alcohol consumption in May–June 2020 31% higher than in wave 8 (Fig. 1a, Supporting information, Table E3), but not different to February 2020 (IRR = 1.08; 95% CI = 0.98, 1.19). In contrast, the typical quantity consumed per occasion in May–June 2020 declined by 27% from February 2020 (Fig. 1b), continuing a downward trend since wave 8 (41% lower than wave 8). Binge drinking was stable throughout the period to February 2020, but then declined by 28% in May–June 2020 (IRR = 0.72; 95% CI = 0.63, 0.83; Fig. 1c). Overall consumption (frequency × quantity) declined 17% from February 2020 (IRR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.73, 0.95; Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

Analysis of change in frequency, typical quantity, binge drinking and total consumption of alcohol consumption over time: results of negative binomial mixed effects models. Outcomes were analysed using negative binomial mixed‐effects models, with February 2020 as the reference category, and results presented as exponented coefficients corresponding to incidence rate ratios (IRRs), with bounds of 95% confidence intervals shown in dashed lines. Models are adjusted for covariates; full results are included in Supporting information, Table E2. Results are based on multiple imputation with estimates combined using Rubin's rules

Respondents reported a lower maximum number of drinks consumed in May–June 2020 compared with February (coeff. = −1.58; 95% CI = –1.99, −1.16; Table 4. and Supporting information, Table E3). More than a third (36.8%) reported experiencing an alcohol‐related harm in February 2020, which declined to 26.2% in May–June 2020 (Table 5). Similarly, there was an approximately 30% decline in the number of harms reported (IRR = 0.65; 95% CI = 0.54, 0.79; Table 4.).

Table 4.

Change in maximum alcohol consumed, number of alcohol‐related harms, drinking context and use of delivery services during COVID‐19 restrictions compared to February 2020: results of mixed‐effects models.

| Maximum alcohol consumed in month a | Number of alcohol‐related harms b | Drinking alone c | Drinking with others in person c | Drinking with others virtually c | Use of alcohol delivery services d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | Coeff. (95% CI) | Coeff. (95% CI) | Coeff. (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| February 2020 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| May/June 2020 | −1.58 (−1.99, −1.16) | 0.65 (0.54, 0.79) | 2.15 (0.50, 3.81) | −13.80 (−17.56, −10.04) | 7.80 (5.57, 10.02) | 0.68 (0.43, 1.08) |

Analysed using linear mixed‐effects models, with results presented as a coefficient equating to the difference in the mean maximum alcohol consumed.

Analysed using negative binomial mixed‐effects models, with results presented as incidence rate ratios (IRRs).

Analysed using linear mixed‐effects models with results presented as coefficients equating to the difference in the mean proportion of consumption in each setting.

Analysed using logistic mixed‐effects models, and presented as odds ratios (ORs). Models are adjusted for covariates; full results are included in Supporting information, Table E4. Results are based on multiple imputation with estimates combined using Rubin's rules.

Table 5.

Self‐reported change in alcohol consumption due to COVID‐19 restrictions, with reasons for the change.

| Self‐reported change in drinking since before the COVID‐19 restrictions | % |

|---|---|

| Increased | 19.4 |

| Stayed the same | 57.0 |

| Decreased | 23.5 |

| Reasons for increased consumption (n = 75) | |

| More bored/less things to occupy time | 78.0 |

| More time to use alcohol | 55.7 |

| To cope with anxiety/stress of day‐to‐day activities (e.g. looking after children, work) | 40.2 |

| Greater anxiety/depression with COVID‐19 | 37.0 |

| Larger amounts available on hand because I stocked up | 29.0 |

| To cope with loneliness | 26.3 |

| More money to buy alcohol | 17.9 |

| Buying alcohol more on‐line/via delivery services | 14.5 |

| Reasons for decreased consumption (n = 116) | |

| Fewer opportunities to be with people/go out to drink | 91.2 |

| Didn't feel like using alcohol | 52.5 |

| Because of work/study commitments | 34.5 |

| Less money to spend on alcohol or saving money | 27.8 |

| Avoiding leaving home to obtain alcohol | 26.1 |

| Worried about effects on my mental health | 26.0 |

| Worried about effects on my physical health | 22.3 |

| Living arrangements made it difficult to use alcohol | 17.5 |

| To avoid the hangover | 17.4 |

| Worried that my use was out of control | 13.3 |

| Worried effects of alcohol may make symptoms worse if get COVID‐19 | 12.7 |

| Other people were worried about my use | 12.6 |

Results are based on multiple imputation with estimates combined using Rubin's rules.

In May–June 2020, compared to February 2020, there were increases in the proportion of drinking alone reported by participants (coeff. = 2.15; 95% CI = 0.50, 3.81) and in drinking with others virtually (coeff. = 7.80; 95% CI = 5.57, 10.02) and decreases in drinking with others in person (coeff. = −13.80; 95% CI = –17.56, −10.04) and in the use of alcohol delivery services (OR = 0.68; 95% CI = 0.43, 1.08).

Gender differences

Changes in alcohol consumption were relatively consistent by gender, although men showed higher incidence rates of drinking across the period than women (Supporting information, Fig. E1). However, while there were significant declines in typical quantity consumed and binge drinking for both men and women (Supporting information, Figs E1b and E1c), there was a decline in overall consumption only among women (IRR = 0.72; 95% CI = 0.55, 0.94; Supporting information, Fig. E1d and Table E4).

Both men and women showed declines in the maximum amount of alcohol they consumed on an occasion, with mean declines of 1.74 drinks among men (95% CI = −2.41, −1.07) and 1.47 among women (95% CI = −1.99, −0.95; Supporting information, Fig. E2a and Table E5). Patterns of alcohol‐related harms were consistent across men and women (Supporting information, Fig. E2b). Men drank alone more in May–June than February (Supporting information, Fig. E2c and Table E6), but women did not. Otherwise, the results for drinking context were similar to the overall results. There was no change in the use of alcohol delivery services by gender (Supporting information, Fig. E2f).

Alcohol use by level of consumption prior to the COVID‐19 pandemic

Those in the upper half of drinkers drank more frequently, and in greater quantity, than the lower half of drinkers. Both groups showed similar trends during the course of the study, with no change in frequency, but declines in typical quantity consumed and frequency of binge drinking. However, only those in the upper half of drinkers showed a decline in overall consumption (Supporting information, Fig. E3 and Table E7). Similarly, both the upper and lower half of drinkers showed declines in the maximum number of drinks consumed (Supporting information, Fig. E4a and Table E8) and the number of alcohol‐related harms experienced (Supporting information, Fig. E4b). Neither group reported changes in use of alcohol delivery services (Supporting information, Fig. E4f and Table E9). Sensitivity analysis split by ‘high‐risk’ drinking based on binge drinking or consuming > 10 drinks per week were very similar to the primary analysis (Supporting information, Figs E5–E6 and Tables E10‐E12).

Drivers of change in alcohol use

Approximately one in five participants (19.4%) perceived that their alcohol use had increased since the COVID‐19 restrictions, while approximately a quarter (23.5%) said that their use had decreased. Compared to a measure of change derived from the amount of alcohol reported consumed in in February 2020 and May–June 2020 there was a relatively high degree of discrepancy, with 61% in the same category (alcohol use decreased on both, alcohol use stayed the same on both or alcohol use increased on both measures; Supporting information, Table E13). Of those who reported increased consumption, the most common reasons endorsed related to boredom and having fewer things to occupy them (78.0%) and having more time to drink (55.7%; Table 5). The most common reason for decreased consumption was having fewer opportunities to go out or be with people (91.2%).

Sensitivity analyses using continuous time

Results of the sensitivity analyses using continuous rather than categorical time were broadly consistent with the primary analyses, with increases in the frequency of consumption, but decreases in typical quantity consumed (Supporting information, Fig. E7). These results were similar when split by gender (Supporting information, Fig. E8) and overall drinking in wave 8 (Supporting information, Fig. E9). These results were largely unaffected by the omission of the retrospective data for February 2020 (Supporting information, Figs E10–E12).

Discussion

We examined the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and associated restrictions on alcohol consumption among a cohort of young adults, finding declines in typical quantity consumed, overall consumption and frequency of binge drinking.

The use of alcohol is the leading risk for disability‐adjusted life‐years in 10–24‐year‐olds [31], as well as being linked to a range of other health burdens [32, 33]. As such, altered patterns of alcohol consumption during the pandemic, with young people less likely to drink in large quantities, is of considerable interest. The number of acute alcohol‐related harms (which are more strongly associated with quantity consumed per drinking occasion than frequency of drinking) [34] saw a similar decline. This decline may be driven by the fact that drinking was more likely to occur alone or ‘virtually’ with others due to the need to isolate, which reduces the risk of harms such as fighting with strangers and traffic accidents.

Our findings broadly align with research showing that alcohol consumption in Australia declined due to restrictions early in the pandemic [35], although other research has shown an increase in quantity of alcohol consumed during the pandemic in Australia and internationally [36]. In contrast, past research has shown greater increases in alcohol consumption among women than men during pandemics [37] while this study found relatively similar changes in both men and women, with pre‐existing gender differences remaining.

The changes observed in drinking context also align with other research showing that young people consume more alcohol outside the home [15]. With restrictions preventing people from going out, ‘drinking with others’ was expected to decline. However, this was matched largely by increases in drinking ‘virtually’ with others. That is, it appears that alcohol consumption in this demographic remains a social activity, with only the medium changing.

There were differences based on level of alcohol consumption pre‐COVID‐19, with declines in overall consumption among those drinking at heavier levels before COVID‐19 but not those drinking at lower levels. This suggests that studies examining population‐level changes may miss important nuances in individual‐level changes in consumption. While some of this may be attributable to regression to the mean, the changes in the higher consumption group mirrored the overall changes in the sample while the lower consumption group was more stable, suggesting that declines in overall consumption were driven by reduced consumption by heavier drinkers.

Importantly, the sample reported relatively little concern about the COVID‐19 disease itself, and only one respondent had been diagnosed with the disease. Rather, changes in consumption appear to be driven by the COVID‐19 restrictions although, given the range of resulting social and economic impacts, the precise cause remains unclear. In addition, while restrictions have softened since these data were collected, the pandemic is ongoing and some restrictions will probably remain for some time. As such, it is likely that other impacts may emerge that were not present at the time of this survey and may have implications for alcohol consumption.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of our study is that we used prospective longitudinal data, and thus do not rely upon delayed recall of alcohol consumption prior to the pandemic, an issue underlined by the discrepancy between self‐reported change and changed derived from prospective data. However, not all items were included in our prospective survey, and thus some analyses rely upon recall concerning February 2020, a period 3–4 months prior to the survey completion. Nevertheless, sensitivity analyses were similar regardless of whether or not they included the data for February 2020, providing some reassurance to the reliability of the data collected. In addition, the period covered by the COVID‐19 survey was shorter than the annual APSALS surveys—thus, seasonal differences may affect the COVID‐19 survey that are less present in the main data.

We also note that the APSALS cohort were recruited using an opt‐in process, and thus results may not generalize to the general population of young adults. However, APSALS has similar levels of alcohol use and a comparable demographic profile to the Australian population, although families of lower socio‐economic status are under‐represented [18]. While the APSALS sample was broadly representative, the COVID‐19 survey subsample was more likely to be female. However, as the aim of the study was to investigate trends rather than prevalence, this should not impact the reliability of the findings.

Conclusions

We present evidence indicating decreased overall alcohol consumption, binge drinking and alcohol‐related harms among young Australians during the COVID‐19 restrictions, although this differed by levels of alcohol consumption prior to the pandemic.

Author contributions

Philip Clare: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; visualization. Alexandra Aiken: Data curation; funding acquisition; investigation; project administration. Wing See Yuen: Data curation; investigation; project administration. Emily Upton: Investigation; project administration. Kypros Kypri: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; project administration. Louisa Degenhardt: Conceptualization; investigation; project administration. Raimondo Bruno: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; project administration. Jim McCambridge: Funding acquisition; investigation; project administration. Nyanda McBride: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation. Delyse Hutchinson: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; project administration. Tim Slade: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation. Richard Mattick: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; investigation; project administration; supervision. Amy Peacock: Conceptualization; investigation; project administration; supervision.

Supporting information

Data S1 Appendix A – Timeline of survey completion

Figure A1 Dates of survey completion of each wave included in study.

Figure A2 Dates of survey completion shown against COVID‐19 cases in Australia.

Figure A3 Dates of survey completion shown against stringency of Australian response to COVID‐19.

Appendix B – STROBE

Table B1 STROBE checklist.

Figure B1 Study flowchart of recruitment and assessment of APSALS cohort.

Appendix C – Measures

Table C1 Summary of times at which each outcome measure was assessed.

Table C2 Equivalence of frequency response options for pro‐rating of annual to monthly frequency.

Table C3 Items included in reduced SHAHRP harms scale.

Appendix D – Missing data

Table D1 Patterns of missing data

Appendix E – Additional results

Table E1 Location of participants who completed COVID‐19 survey at time of survey completion.

Table E2 Predictors of frequency, typical quantity, binge drinking and total consumption of alcohol consumption over time.

Table E3 Predictors of maximum alcohol consumed, number of alcohol‐related harms, drinking context, and use of delivery services – change during COVID‐19 restrictions.

Figure E1 Frequency, typical quantity, binge drinking and total consumption of alcohol consumption – time by gender interaction.

Table E4 Predictors of frequency, typical quantity, binge drinking and total consumption of alcohol consumption – time by gender interaction.

Figure E2 Change in maximum alcohol consumed, number of alcohol‐related harms, drinking context, and use of delivery services – time by gender interaction.

Acknowledgements

This research includes computations conducted using the computational cluster Katana supported by Research Technology Services at UNSW Sydney.

Clare, P. J. , Aiken, A. , Yuen, W. S. , Upton, E. , Kypri, K. , Degenhardt, L. , Bruno, R. , McCambridge, J. , McBride, N. , Hutchinson, D. , Slade, T. , Mattick, R. , and Peacock, A. (2021) Alcohol use among young Australian adults in May–June 2020 during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a prospective cohort study. Addiction, 116: 3398–3407. 10.1111/add.15599

References

- 1. Colbert S., Wilkinson C., Thornton L., Richmond R. COVID‐19 and alcohol in Australia: industry changes and public health impacts. Drug Alcohol Rev 2020; 39: 435–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dietze P. M., Peacock A. Illicit drug use and harms in Australia in the context of COVID‐19 and associated restrictions: anticipated consequences and initial responses. Drug Alcohol Rev 2020; 39: 297–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marsden J., Darke S., Hall W., Hickman M., Holmes J., Humphreys K., et al. Mitigating and learning from the impact of COVID‐19 infection on addictive disorders. Addiction 2020; 115: 1007–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Melbourne Institute Taking the Pulse of the Nation. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keyes K. M., Hatzenbuehler M. L., Hasin D. S. Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: the epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology 2011; 218: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clifton K. Global Economic and Markets Research report: CBA Card Spend—week ending 3 April 2020. Sydney, Australia: Commonwealth Bank of Australia; 2020.

- 7. Alcohol Beverages Australia . Impact of COVID‐19 on the drinks industry. Sydney, Australia: Alcohol Beverages Australia; 2020. Available at: https://www.alcoholbeveragesaustralia.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/ABA‐Industry‐report‐on‐coronavirus.pdf (accessed 13 July 2020).

- 8. Bade R., Simpson B. S., Ghetia M., Nguyen L., White J. M., Gerber C. Changes in alcohol consumption associated with social distancing and self‐isolation policies triggered by COVID‐19 in South Australia: a wastewater analysis study. Addiction 2021; 116: 1600–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Household Impacts of COVID‐19 Survey, cat. no. 4940.0. 2020. [13/07/2020]. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4940.0 (accessed 13 July 2020).

- 10. Stanton R., To Q. G., Khalesi S., Williams S. L., Alley S. J., Thwaite T. L., et al. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID‐19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chodkiewicz J., Talarowska M., Miniszewska J., Nawrocka N., Bilinski P. Alcohol consumption reported during the COVID‐19 pandemic: the initial stage. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biddle N, Edwards B, Gray M, Sollis K. Alcohol Consumption During the COVID‐19 Period: May 2020. COVID‐19 Briefing Paper. Canberra, Australia: Australian National University; 2020.

- 13. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) . National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Contract No.: PHE 270. Canberra, Australia: AIHW; 2020.

- 14. Sinha G., Tan K., Zhan M. Patterns of financial attributes and behaviors of emerging adults in the United States. Child Youth Serv Rev 2018; 93: 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Callinan S., Livingston M., Room R., Dietze P. Drinking contexts and alcohol consumption: how much alcohol is consumed in different Australian locations? J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2016; 77: 612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodriguez L. M., Litt D. M., Stewart S. H. Drinking to cope with the pandemic: the unique associations of COVID‐19‐related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addict Behav 2020; 110: 106532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neill E., Meyer D., Toh W. L., van Rheenen T. E., Phillipou A., Tan E. J., et al. Alcohol use in Australia during the early days of the COVID‐19 pandemic: initial results from the COLLATE project. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020; 10.1111/pcn.13099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aiken A., Wadolowski M., Bruno R., Najman J., Kypri K., Slade T., et al. Cohort profile: the Australian parental supply of alcohol longitudinal study (APSALS). Int J Epidemiol 2017; 46: e6–e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gmel G., Rehm J. Measuring alcohol consumption. Contemp Drug Probl 2004; 31: 467–540. [Google Scholar]

- 20. McBride N., Farringdon F., Meuleners L., Midford R. The School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project: Details of Intervention Development and Research Procedures. Perth, Australia: National Drug Research Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Health and Medical Research Council Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks From Drinking Alcohol. Canberra, Australia: Department of Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fisher L. B., Miles I., Austin S., Camargo C. A., Colditz G. A. Jr. Predictors of initiation of alcohol use among US adolescents: findings from a prospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161: 959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swendsen J., Burstein M., Case B., Conway K. P., Dierker L., He J., et al. Use and abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs in US adolescents: results of the national comorbidity survey–adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012; 69: 390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pink B. Information Paper: An Introduction to Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), 2006. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuperman S., Chan G., Kramer J. R., Wetherill L., Bucholz K. K., Dick D., et al. A model to determine the likely age of an adolescent's first drink of alcohol. Pediatrics 2013; 131: 242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2019.

- 27. van Buuren S., Groothuis‐Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011; 45; 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Honaker J., King G., Blackwell M. Amelia II: a program for missing data. J Stat Softw 2011; 45: 47. [Google Scholar]

- 29. R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, 4.0.3 edn. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith P. Hard lockdown and a ‘health dictatorship’: Australia's lucky escape from covid‐19. BMJ 2020; 371: m4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gore F. M., Bloem P. J. N., Patton G. C., Ferguson J., Joseph V., Coffey C., et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2011; 377: 2093–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patton G. C., Coffey C., Cappa C., Currie D., Riley L., Gore F., et al. Health of the world's adolescents: a synthesis of internationally comparable data. Lancet 2012; 379: 1665–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hall W. D., Patton G., Stockings E., Weier M., Lynskey M., Morley K. I., et al. Why young people's substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3: 265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Midanik L. T., Tam T. W., Greenfield T. K., Caetano R. Risk functions for alcohol‐related problems in a 1988 US national sample. Addiction 1996; 91: 1427–1437 discussion 39–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Newby J. M., O'Moore K., Tang S., Christensen H., Faasse K. Acute mental health responses during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia. PLOS ONE 2020; 15: e0236562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winstock A. R., Zhuparris A., Gilchrist G., Davies E. L., Puljevic C., Potts L. et al. GDS Special Edition on COVID‐19 Key Findings Report. London, UK: Global Drug Survey; 2020.

- 37. Rehm J., Kilian C., Ferreira‐Borges C., Jernigan D., Monteiro M., Parry C. D. H., et al. Alcohol use in times of the COVID 19: implications for monitoring and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev 2020; 39: 301–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Appendix A – Timeline of survey completion

Figure A1 Dates of survey completion of each wave included in study.

Figure A2 Dates of survey completion shown against COVID‐19 cases in Australia.

Figure A3 Dates of survey completion shown against stringency of Australian response to COVID‐19.

Appendix B – STROBE

Table B1 STROBE checklist.

Figure B1 Study flowchart of recruitment and assessment of APSALS cohort.

Appendix C – Measures

Table C1 Summary of times at which each outcome measure was assessed.

Table C2 Equivalence of frequency response options for pro‐rating of annual to monthly frequency.

Table C3 Items included in reduced SHAHRP harms scale.

Appendix D – Missing data

Table D1 Patterns of missing data

Appendix E – Additional results

Table E1 Location of participants who completed COVID‐19 survey at time of survey completion.

Table E2 Predictors of frequency, typical quantity, binge drinking and total consumption of alcohol consumption over time.

Table E3 Predictors of maximum alcohol consumed, number of alcohol‐related harms, drinking context, and use of delivery services – change during COVID‐19 restrictions.

Figure E1 Frequency, typical quantity, binge drinking and total consumption of alcohol consumption – time by gender interaction.

Table E4 Predictors of frequency, typical quantity, binge drinking and total consumption of alcohol consumption – time by gender interaction.

Figure E2 Change in maximum alcohol consumed, number of alcohol‐related harms, drinking context, and use of delivery services – time by gender interaction.