Abstract

Objective

Cervical cancer in Cameroon ranks as the second most frequent cancer among women and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths, mainly due to the lack of prevention. Our principal objective was to explore potential barriers to an human papillomavirus (HPV)-based cervical cancer screening from a healthcare provider (HCP) perspective in a low-income context. Second, we aimed to explore the acceptability of a single-visit approach using HPV self-sampling.

Settings

The study took place in the District hospital of Dschang, Cameroon.

Participants

Focus groups (FGs) involved HCPs working in the area of Dschang and Mbouda.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

All FGs were audiorecorded, transcribed and coded independently by two researchers using the ATLAS.ti software. A qualitative methodology was used to capture insights related to the way people perceive their surroundings. Discussion topics focused on perceived barriers, suggestions to improve cervical cancer screening uptake, and acceptability.

Results

A total of 16 HCPs were interviewed between July and August 2019. The identified barriers were (1) lack of basic knowledge on cervical cancer among most women and men and (2) lack of awareness of the role and existence of a screening programme to prevent it. Screening for cervical cancer prevention using HPV self-sampling was considered as an acceptable approach for patients according to HCPs. Traditional chiefs were identified as key entry points to raise awareness because they were perceived as essential to reach not only women, but also their male partners.

Conclusions

Awareness campaigns about cervical cancer, its prevention and the availability of the screening programmes are crucial. Furthermore, involving male partners, as well as key community leaders or institutions was identified as a key strategy to encourage participation in the cervical cancer screening programme.

Trial registration

Ethical Cantonal Board of Geneva, Switzerland (CCER, N°2017-0110 and CER-amendment n°2) and Cameroonian National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research (N°2018/07/1083/CE/CNERSH/SP).

Keywords: community gynaecology, gynaecological oncology, preventive medicine, public health, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A strength of this study was its qualitative approach, with the aim to explore cervical cancer screening barriers in Cameroon from the perspective of healthcare providers (HCPs).

Second, it was conducted on-site with participation of HCPs with different educational backgrounds.

As focus groups (FGs) were conducted by a Cameroonian anthropologist, interviewer bias was intended to be minimised but cannot be excluded due to his higher education and gender.

A limitation of the study was the methodology of the FGs which covered a range of topics considered important by the participants, and results might not be applicable to the general population.

Introduction

According to the WHO, 570 000 cervical cancer cases were diagnosed worldwide and 311 000 deaths were registered in 2018, most of them occurring in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 In sub-Saharan Africa, cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer among women and the leading cause of deaths.2 In Cameroon, a total of 2356 new cases were diagnosed in 2018 and 1546 deaths were documented, with cervical cancer being the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women.2 Therefore, cervical cancer is a major public health concern in Cameroon.

In high-income countries (HICs) organised screening programmes with high coverage rates have shown a significant reduction in the number of new cases and mortality rates.3 As a result, there is an important difference in the incidence of and mortality rates from cervical cancer between LMICs and HICs. Thus, prevention strategies are important to reduce the gap in health inequalities between LMICs and HICs.4

In 2018, the WHO Director-General called all countries to take action to eliminate cervical cancer worldwide. To reach this goal, every country must achieve the following global targets by 20301: (1) increase vaccination coverage against human papillomavirus (HPV), (2) increase screening coverage using HPV testing5 and, (3) offer appropriate management for women with an invasive cervical cancer.

To reach the second goal, HPV-based screening has been suggested that can be performed by women themselves. HPV self-sampling is an innovative approach for cervical cancer prevention, requiring minimal human resources, and sampling kits can be offered anywhere (villages, markets, public squares or homes) increasing reach to vulnerable and underserved populations. Previous studies have demonstrated that, following efficient education and clear instructions, it is a highly acceptable and well-received method for most females eligible for screening and healthcare providers (HCPs).6

HPV self-sampling provides a unique opportunity to reduce cervical cancer mortality in women and diminish the inequalities in access to cervical cancer prevention services. Since 2018, a partnership between University Hospitals of Geneva (Switzerland), University Hospital of Yaoundé (Cameroon) and the University of Dschang (Cameroon) introduced a 5-year programme (2018–2023) based on primary self-sampling for HPV screening. This strategy is based on a ‘1 day visit’ termed the 3T-approach (for Testing, Triage and Treatment). Community-based sensitisation campaigns targeted a population of women aged between 30 and 49 years old for cervical cancer screening based on the 3T-approach at the Dschang District Hospital. HPV self-samples were analysed using a point-of-care test (Xpert HPV assay) followed by VIA/VILI triage if HPV positive and treatment if required.6

However, approaches to scaling up these interventions in rural settings may differ7 and its introduction requires preparatory work before implementation. To better reach the target population, cultural, social, societal and financial barriers, as well as other circumstances that may affect the acceptance and uptake of cervical cancer screening, should be identified. Therefore, the first aim of our study was to identify barriers to cervical cancer screening from the HCPs’ perspective, as they influence women’s prevention behaviour.8 9 The second aim was to identify facilitators and explore acceptability and perception of a single-visit approach.

Methods

Study site

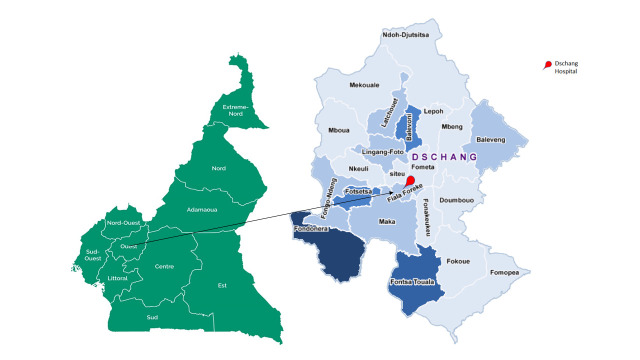

The qualitative data were collected between July and August 2019 in the district of Dschang, a city located in the West of Cameroon, 4 hours from Doula and 5 hours from Yaoundé (figure 1). The Dschang city and surrounding areas have an estimated population of approximately 63 838 inhabitants.10 The present study is part of a large trial termed ‘3T-approach’ implemented with the support of the Ministry of Health in September 2018 for a 5-year period expecting to include 6000 female participants.

Figure 1.

Map of Cameroon and of the districts of health: location of study site.

Study setting and design

A qualitative methodology using focus groups (FGs) was chosen to capture insights related to the way people perceive and interpret their surroundings.11 12 A semistructured questionnaire, inspired by a previous study conducted in Uganda,12 was used to lead the conversation.13 Discussion topics focused on (1) perceived barriers, (2) suggestions to improve cervical cancer screening uptake and (3) acceptability of the 3T-approach. The interview guide was pretested and adapted in Geneva prior to the study in Cameroon, addressing factors such as comprehensibility and time. The FGs took place in a private room in the District Hospital of Dschang and were conducted in French, by a Cameroonian anthropologist (NA).

Recruitment and sampling

The study used a systematic, non-probabilistic sampling approach. According to the standards of qualitative methodology, we applied the principle of saturation. HCPs were invited to participate in the small FGs from the District Hospital of Dschang, where the screening programme was based, from the community setting, where cervical cancer screening is promoted, and from the Mbouda District Hospital, which frequently refers women to the screening site. They were either working as medical or as community healthcare workers. An information document and a consent form were distributed prior to the FGs and only those who provided written consent were included in the study.

Patient and public involvement

Only HCPs were involved.

Data analysis

All FGs were recorded, anonymised and fully transcribed. Transcripts were systematically coded with a thematic approach, using ATLAS.ti CAQDAS. Most codes were a priori defined based on the main research questions. Further codes emerged over the coding process itself after initial reading of the transcripts. Codes were aggregated in overarching themes. Main topics and barriers to access screening that were identified in all the FGs were analysed and classified. Coding was conducted by two coresearchers separately and compared afterwards.

Barriers perception

Identified barriers were classified according to the conceptual framework of Thaddeus and Maine of the three-delay model.7 According to their concept, increasing the availability of services (for instance by building more facilities or expanding health programmes) does not always increase the use of services. Thaddeus and Maine argue that the decision to seek healthcare can be classified into three types of delays: first, the delay in the decision to seek care, including the role of the woman in the decision-making process but also structural factors such as distance from the health facility. Second, the delay to reach adequate care at the health facility mostly due to costs of transportation and poor road conditions. Third, the delay to receive adequate care once at the facility, due to availability of materials or staff. Even though the model was applied originally in the context of maternal mortality, it is adaptable to multiple health situations in order to identify key obstacles and how to address them.

Results

Setting

Between mid-July and mid-August 2019, four FGs with a total of 16 participants (12 women and 4 men) were conducted in the District Hospital of Dschang. The FGs lasted about 60–75 min. All invited HCPs participated in the study. The majority were professionals working in hospitals, but community healthcare workers were also included, as they were doing outreach for the cervical cancer screening programme. Thirteen HCPs were from the Dschang district and three from the Mbouda district, who frequently sent women to Dschang for screening. Participants of two FGs had received specific training on cervical cancer prevention, while the two other FGs were not specialised. Among the female participants 75% had themselves been screened for HPV.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

The 16 participants were all HCPs with an average of 15 years work experience in healthcare. Most of them (44%) were midwives, married (75%) and on average 41 years old (range 28–62 years). Education level was high; more than three quarters had completed at least secondary education and nearly half had obtained a university degree. In one FG (FG with community healthcare workers), the level of education was lower. Further details can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| Number of participants | 16 |

| Women | 12 (75%) |

| Men | 4 (25%) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 41.7 |

| Range | 28–62 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 12 (75%) |

| In relationship | 0 (0) |

| Single | 4 (25%) |

| Divorced or widowed | 0 |

| Education | |

| Never attended school | 0 (0%) |

| Finished primary education | 2 (12%) |

| Finished secondary education | 6 (38%) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 7 (44%) |

| No answer | 1 (6%) |

| Professional experience | |

| Mean (in years) range from 2 to 33 years | 15.4 |

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 3 (19%) |

| Midwife | 7 (44%) |

| Community healthcare worker | 5 (31%) |

| Other | 1 (6%) |

Barriers to cervical cancer screening

Barriers to cervical cancer screening emerged in different areas and were classified according to the conceptual framework of the three-delay model.7

Phase I: delay in the decision to seek screening

According to Thaddeus and Maine, the healthcare seeking process starts with the decision to seek care and various factors will shape the decision of women to get screened. According to this model, barriers most commonly studied in the first delay are distance, cost, quality of care and sociocultural factors.7 Those barriers also emerged in our study, which revealed the first delay as the most important one.

Costs

The financial cost of receiving care has been extensively studied in the literature.7 Costs can include transportation costs, but also costs for physicians, facility fees, the cost of medications and other supplies.14 Previous studies have noted that costs and distance are often closely linked as longer distance to reach a facility results in higher cost.14 Cost of transportation was indeed frequently mentioned by the HCPs from Mbouda district, from which patients need to travel to the District hHospital of Dschang to get screened.

They [the women] will come [to Dschang] because it is free. But when they think there will be no cost for them and finally they do have to pay transport themselves, it might prevent them from going. (Female hospital staff)

Furthermore, opportunity costs were recognised as an important barrier causing a delay to seek care. Professionals noted that getting screened was not a priority for women because of lack of time. Getting to the screening centre, attending the information sessions while waiting for screening services, was mentioned as important time lost for daily duties that still need to be performed.

For those women, they first focus on the daily issues such as farming, or how to get food for their children. They only get free time to get to town on the day of the market and this is when most come to the center. (Male community healthcare worker)

However, besides the financial constraints, several HCPs noticed mistrust and ambivalence regarding the fact that the screening programme is free of charge:

There are two sides with a program free of charge because some people think that when it is free it means that it is something useless. Because when something is be important it cannot be for free. (Female hospital staff)

Distance to the facility

Distance plays an important role as a disincentive to seek care and increases the disparity between people living in rural versus urban areas.15 16 This barrier influences women’s decision process in seeking care, but also the time she needs to reach the facility, therefore also affecting delay of phase II. Several HCPs recognised distance as an important barrier to attending cervical cancer screening, as an HCP explained:

But the problem is that they [the women] are going to say: I do not have transportation means to arrive from so far. I prefer staying at home because of transport. (Female hospital staff).

Illness factors and education

The decision to seek healthcare depends on the patient’s recognition of the disease, but also on its perceived severity requiring medical treatment.7 17 Nearly all HCPs mentioned a profound lack of awareness on cervical cancer and its symptoms among women, which inhibits the recognition of cervical cancer and the perceived need of screening. A female community healthcare worker illustrated:

The issue is that information doesn’t come through. They [the women] didn’t know what was happening. They did not know that such things existed. (Female community healthcare worker).

Importantly, nearly all FG participants mentioned that the lack of awareness was more prevalent among women living in rural areas, where formal educational levels were lower. The link between lack of knowledge and education has been frequently mentioned in previous studies15 16 and was confirmed in the current one. One female HCP of the Dschang District Hospital stated:

And for many of them, even when you try to inform them, you realise how important the level of education is. They understand today but they will forget tomorrow. Or maybe they tell you that they understand and they don’t truly. (Female HCP)

As a consequence, HCPs mentioned the importance of using appropriate wording that is easy to understand and will not frighten the patients. For example, the wording seropositivity is not appropriate in the area of HPV testing. However, community workers who are influenced by other campaigns, such as HIV testing, have been using it. As the word ‘seropositivity’ is closely linked to the HIV status, HCPs suggested to use other terms in case of a positive HPV infection.

Seropositive or seronegative is not appropriate. This wording should not be used in our language. (Male community worker)

However, even if women had basic knowledge, two additional factors for not accessing screening were reported. First, misconceptions about symptoms, transmission or risk factors, but also fear of the severity of the disease. One of the female FG participants illustrated misconceptions around cervical cancer as women did not experience signs or symptoms for cervical cancer:

They will tell you : I am not sick ! There is nothing there. (Female hospital staff).

Second, fear towards results was frequently observed especially by the community health workers who tried to motivate women to attend screening. Some women may give up on being tested because they think a positive result might be a synonym to death.

It is fear. Women are afraid of a potentially positive test result, because they wonder how they are going to make it. There is fear. Fear is the barrier. (…) (Male community health worker)

Perceived quality of care

Perceived quality of care and previous experiences with the healthcare system influences the decision of prospective patients. Important factors highlighted include satisfaction or dissatisfaction with previous treatment or screening, friendliness and communication of hospital staff and experience with administrative procedures.7 18 19 Even if HCPs noted that most of the women were pleased with the screening and treatment procedures of the cervical cancer programme, HCPs recognised that some patients perceived structural factors (such as waiting times or administrative procedures) as a barrier. One HCP from Dschang noted:

And some patients told us that it takes a lot of time. For them it should be a 10 minute thing. But they enter, they stay one hour at the informative causerie (Informative causerie refers to the informative talk that is given to women to give information on cervical cancer prior to screening.) then they register, they do the sampling and they wait for the results! (…). This prevents them from coming. (Female hospital staff)

Additionally, the study revealed that administrative procedures could be improved in respect to testing results and respect of privacy. As a male HCP explained:

There is…there is as well the result. When a group of women arrive and we give them the results, we will tell one of them to wait…when we tell her to wait it will draw attention from the others. If the first ones are gone and this one need to wait it means…it means that there is a problem (…) and because the other women knew (…) As soon as she is back at home there will be some gossip. People will say that she had to stay. (Male hospital staff)

Lastly, several HCPs admitted that contact with patients could be improved. They recognised the importance of making the patient feel comfortable as well as the need to address the psychological dimensions of screening such as the fear of the outcome.

Making the patient feel comfortable is important as well…sometimes we do not manage to welcome patients as we should. (Female HCP)

Phase II: delay reaching the screening centr

As mentioned previously, the accessibility of services plays a role in influencing the decision to go to the screening centre. Thaddeus and Maine determine the time spent in reaching a facility as an important second delay, which is very common, particularly in rural areas.7 HCPs participating in the FGs mentioned two important barriers for women to attend the cervical cancer programme. The first one was the financial cost, which has already been illustrated in the first delay. The second equally important barrier was the distribution of facilities. Reaching screening facilities has been linked not only to a lack of transportation, conditions of roads, but also to the distribution of health facilities. The only facility offering cervical cancer screening in Western Cameroon is the District Hospital of Dschang. Therefore, women in rural areas face a double burden in respect to healthcare: costs and difficulty to reach the facility. Additionally, community healthcare workers faced difficulties to reach villages contributing to the lack of knowledge mentioned under the first delay. Therefore, FG participants suggested that motorcycles could be a feasible solution either to educate women and their families about cervical cancer screening or to provide mobile screening facilities.

If we had access to a motocycle, …we could go a little further in the villages. Because we musn’t forget that sometimes you’re ready but you are not able to travel, to travel further… (Community healthcare worker)

Phase III: receiving adequate and appropriate screening and treatment

The third delay includes factors related to the healthcare at the facility such as shortage of supplies, equipment or trained personnel and competence of the available personnel. None of the HCPs mentioned factors related to shortage of supplies, equipment or staff, but they perceived that referral systems inside the medical community were still inadequate. One female HCP working at the Dschang screening site explained:

Honestly doctors here, they are too distant. … I can count maybe only two that have stopped by to see what we are doing here [at the screening facility] since we have started. (Female HCP)

HCPs perceived a lack of cervical cancer awareness and interest even in the medical community and wondered if doctors had enough knowledge on when and how to refer women.

Furthermore, the study explored HCPs’ perception of the single-visit approach using HPV self-sampling testing. Overall, the concept to be tested and treated on the same day was very well regarded by the HCPs. This point was consistent among the various FGs.

There are many advantages because everything is already there. The woman will not need to travel to receive treatment. (Female HCP)

Furthermore, lower loss to follow-up rates due to reduced travel costs was seen as an advantage. However, several HCPs noted that women were sceptical regarding the procedure of the HPV self-sampling. A female HCP stated:

I do not think that they trust themselves [ perfoming the test]. They are already worried that they are doing the test themselves. […] Sometimes the HPV self-sampling is done well but they will ask you to do it again to be psychologically reassured. (Female HCP)

Facilitators of cervical cancer screening

As lack of cervical cancer knowledge was perceived by all FG participants as one of the main barriers. FG participants highlighted the need to increase awareness about cervical cancer symptoms, treatment options and prevention strategies by mentioning the available screening programme. As such, churches or ‘traditional chiefs’ were identified as key actors. While churches already inform attendees about cervical cancer and the possibility of screening, involvement of the ‘traditional chiefs (traditional chiefdoms are entities of various size and importance which were former micro precolonial states. They are organised around the emblematic figure of the chief which have a role both political and spiritual. He has a mediator role between world of the livings and of the ancestors.20 They are physical entities where various meeting are held as they have a political, social and cultural role.)’ was seen as crucial to gain access to meetings organised in the ‘cheffery’. Furthermore, as the ‘traditional chiefs’ have enormous influence, their support was seen as very helpful in reducing barriers to cervical cancer screening, but also in involving men in the cervical cancer screening programmes. As most women need their husband’s permission for screening, informing men about cervical cancer screening by the ‘traditional chiefs’ was seen as an important facilitator in encouraging women to attend the screening.

Discussion

The current study is to our knowledge the first conducted in Cameroon aiming to understand women’s potential barriers to a cervical cancer screening programme from a qualitative perspective.

Barriers were organised around the three-delay model and most barriers were identified in phase I (delay in the decision to seek screening).7 Those identified were mainly around the four themes: (1) health literacy, (2) distance to the screening centre, (3) financial constraints and (4) perceived quality of care. The results were concordant with previous international literature. The following discussion concentrates especially on barriers which can be directly addressed by the cervical cancer screening programme. Factors on the macro level, which are dependent on governmental decisions and policies (such as the distribution of healthcare facilities addressing the existing barrier of distance (theme 2)), will not be addressed.

One of the most important barriers identified in our study was health literacy (theme 1). Health literacy has been defined by the WHO as ‘the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health’.21 According to the results of our FGs, the lack of health literacy was noted particularly in rural areas where education was lower and additional barriers due to financial constraints were higher. Kim and Han reported that increasing woman’s health literacy might be the first step towards promoting cervical cancer screening programmes.22

From a public health perspective, raising awareness through the use of mass media, such as radio and television, can improve uptake.12 23 However, HCPs in our study mainly highlighted the importance of tailored cervical cancer awareness campaigns that are adapted to the heterogenous levels of education as well as using local languages. Furthermore, involving community healthcare workers, who are familiar with the local conditions, frequent misconceptions and fatalistic concepts in the community, was mentioned as crucial. This is in concordance with Thaddeus and Maine,7 who reported that women’s recognition of illness and their perception of its severity are important influences on their decision to seek care. Promoting tailored educational campaigns respecting different levels of cervical cancer literacy might increase attendance of cervical cancer screening.22 24

Traditional chiefs were identified as important entry points to raise cervical cancer awareness, because they were perceived as essential to reach not only women, but also their male partners. Men play a significant role in the healthcare decisions and health-seeking behaviour of women and they are found to lack awareness and basic knowledge with respect to cervical cancer.25 26 Involving traditional leaders emerged as one of the key facilitators. Leveraging the governance system of chiefs could promote access to cervical cancer prevention services, including rural women who are especially difficult to reach. While few studies have investigated these actors to date, a recent study by Kapambwe and colleagues showed that the influence of traditional chiefs facilitated access to cervical cancer prevention services in rural Zambia.27

Financial constraints (theme 3) were another important barrier described by nearly all participants. Costs included opportunistic costs while attending the screening, but also costs for transportation which increased with distance. Distance from a health centre is a major disincentive in the decision to seek care causing disparity between rural and local areas and has been mentioned frequently in the literature.7 As such, the single-visit approach minimises this barrier by screening and treating precancerous lesions on the same day. HCPs suggested organising mobile screening. Offering early detection services through mobile units has been shown to be a practical way to increase physical and economic access to screening.28

The last barrier influencing women’s decision to seek care was the perceived quality of care (theme 4). In contrast to previous studies,7–12 participants in our FGs mentioned an interesting aspect towards the programme free of charge. While HCPs valued the screening option offered free of charge (intended to decrease barriers), FG participants explained that several patients questioned the quality of the care and the intentions of the cervical cancer screening programme due to the fact that it is offered free. Therefore, HCPs highlighted the importance to disclose more information about the financing of the programme in order to increase its acceptance.

Furthermore, long administrative procedures, structural challenges leading to a lack of confidentiality and insufficient friendliness of HCPs were mentioned as important factors influencing patients’ satisfaction, as well as disincentive for peers or family through word of mouth. A study conducted in Malawi showed that patient satisfaction is of utmost importance and was higher when women had an appointment or benefited from shorter waiting time.29 Furthermore, the importance of appropriate communication skills has been highlighted in a recent review.30 As a consequence, addressing these identified structural challenges might have a direct benefit to the programme acceptance.

Even if most barriers were mentioned in the first delay, the study revealed that concerns of the HPV self-sampling persist among patients. While the single-visit approach was acknowledged positively, nearly all HCPs mentioned that most women did not trust self-sampling for HPV and preferred physician sampling. Similar concerns have been found in other studies in low-resource settings, but also in HICs, in which women expressed the fear of doing the test wrong, and then getting wrong results.23 31 A study already conducted in Dschang in 201332 showed similar results. Therefore, our study highlights the need not only to educate women about HPV, cervical cancer and its prevention but also to reassure them about the accuracy of HPV self-sampling. The role of HCPs is central to help women build confidence and trust in themselves as well as in the HPV self-sampling. A reinforced trust in HPV self-sampling could be a real asset in maximising geographical coverage of screening as distance was seen as a major barrier.

The study had strengths and limitations. A strength of this study was its qualitative approach with the aim to explore cervical cancer screening barriers in Cameroon from the perspectives of HCPs. Second, it was conducted on-site with participation of HCPs having different educational backgrounds. A limitation of the study was the methodology of FGs which covered a range of topics considered important and chosen by the participants. Therefore results might not be applicable to the general population as another group may have covered others topics. Also, the methodology of the FG design might have prevented some participants from expressing their honest opinion. However, to limit this influence, small FGs with participants from the same educational background were chosen. Moreover, as FGs were conducted by a Cameroonian anthropologist, interviewer bias was intended to be minimised but cannot be excluded due to his higher education and gender. Finally, this study has been based on the HCPs’ perspective. We would need to further evaluate our results directly with women eligible for screening. Currently a second qualitative study with patients is being planned, based on current results, in order to resolve this limitation.

Conclusion

Understanding barriers associated with underutilisation of cervical cancer screening is key to increasing overall screening uptake. The perspective of HCPs can be leveraged to improve screening programmes as their global view and experience reveal major findings. Although qualitative results cannot be generalised, we believe that our results are confirmed by the national and international literature.12–19 21 22 Therefore, reducing those barriers may improve cervical cancer screening programmes at the personal and institutional level. Key strategies to address some of the most important barriers identified in our study should focus on improving health literacy (including the empowerment with respect to HPV self-sampling), involving influential community leaders or institutions (such as churches or traditional chiefs) and finally addressing administrative procedures including HCP’s communication skills.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the physicians and caregivers who participated in the screening campaign. This study was supported by the Dschang District Hospital, Cameroon, and the University Hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland. We also acknowledge Mr Nedejo and colleagues, Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda, for the input provided by their questionnaire used in Uganda. We would like to thank Chandrani Chatterjee and Elanie Marks for their revision on the manuscript and input as native speakers.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Roux Amandine Noemie amandine.roux.bores@gmail.com. Gynecology Division, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland Kenfack Bruno brunokenfack@gmail.com. Mother and child Unit, Dschang District Hospital, Dschang, Cameroon Ndjalla Alexandre alndjalla@gmail.com. Mother and child Unit, Dschang District Hospital, Dschang, Cameroon Sormani Jessica Jessica.Sormani@hcuge.ch. Gynecology Division, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland Wisnak Ania wisniak.ania@gmail.com. Gynecology Division, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland Tatrai Karoline karoline.tatrai@hcuge.ch. Gynecology Division, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland Vassilakos Pierre pierrevassilakos@bluewin.ch. Gynecology Division, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research, Geneva, Switzerland Petignat Patrick patrick.petignat@hcuge.ch. Gynecology Division, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland Schmidt Nicole Nicole.Schmidt@ksh-m.de. Faculty of Social Science, Catholic University of Applied Science, Munich, Germany Gynecology Division, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

Contributors: ANR supported all phases of the research, was responsible for recruitment of participants, data collection, data synthesis and writing the draft and final manuscript. AN supported the data collection process, and participated in the analysis of the qualitative data. PP developed the main idea, supervised the conception, writing and revision of the manuscript. NS helped in all phases of the research and participated in writing the draft and finalising the manuscript. TK facilitated research and on-site data collection. AW helped in writing the draft and finalising the manuscript. BK, JS and PV assisted with the design of the study, recruitment of the study participants and provided essential comments on the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by funding received by the GRSSGO, grant number GRSSGO-PJH-2020-1.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets (transcripts) generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitivity of the data, but summaries of the transcripts are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Cantonal Board of Geneva, Switzerland (Commission cantonale d’éthique de la recherche, CCER, N°2017-0110 and CER-amendment n°2) and the Cameroonian National Ethics Committee for Human Health Research (N°2018/07/1083/CE/CNERSH/SP).

References

- 1.WHO factsheet: Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer [online], 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer

- 2.Global cancer observatory [online], 2019. Available: http://gco.iarc.fr/ [Accessed 11 Oct 2019].

- 3.IARC handbooks of cancer prevention (Vol. 10) [online]. Available: http://screening.iarc.fr/doc/cervicalcancergep.pdf [Accessed 11 Oct 2019].

- 4.IARC Globocan , 2018. Available: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/23-Cervix-uteri-fact-sheet.pdf [Accessed 19 Mar 2020].

- 5.World Health Organization . WHO guidelines for screening and treatment of precancerous lesions for cervical cancer prevention World Health Organization, WHO library cataloguing-in-publication data 2013. [PubMed]

- 6.Vassilakos P, Tebeu P-M, Halle-Ekane GE. 20 années de lutte contre le cancer du col utérin en Afrique Subsaharienne : collaboration médicale entre Genève et Yaoundé. Rev Med Suisse 2019;15:601–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong LP, Wong YL, Low WY, et al. Knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer and screening among Malaysian women who have never had a Pap smear: a qualitative study. Singapore Med J 2009;50:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hweissa NA, Lim JNW, Su TT. Health-care providers’ perceptions, attitudes towards and recommendation practice of cervical cancer screening. Eur J Cancer Care 2016;25:864–70. 10.1111/ecc.12537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bureau central des recensements et des études de population Du Cameroun, Rapport de présentation des résultats définitifs, 2005. Available: http://www.google.ch/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiO64zR8IzuAhUG-6QKHZhoCCIQFjAAegQIAxAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bucrep.cm%2Findex.php%2Ffr%2Fressources-et-documentations%2Ftelechargement%2Fcategory%2F20-prsentation-des-rsultats%3Fdownload%3D36%3Arapport-de-prsentation-des-rsultats-2005&usg=AOvVaw2vcIBb01-4igrQJv6trUcu

- 11.Merry L, Clausen C, Gagnon AJ, et al. Improving qualitative interviews with newly arrived migrant women. Qual Health Res 2011;21:976–86. 10.1177/1049732311403497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ndejjo R, Mukama T, Kiguli J, et al. Knowledge, facilitators and barriers to cervical cancer screening among women in Uganda: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016282. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandelowski M. Focus on qualitative methods, sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health 1995;18:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young JC. Non-use of physicians: methodological approaches, policy implications, and the utility of decision models. Soc Sci Med B 1981;15:499–507. 10.1016/0160-7987(81)90024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roghmann KJ, Zastowny TR. Proximity as a factor in the selection of health care providers: emergency room visits compared to obstetric admissions and abortions. Soc Sci Med 1979;13D:61–9. 10.1016/0160-8002(79)90028-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stock R. Distance and the utilization of health facilities in rural Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 1983;17:563–70. 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90298-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein CM, Muir J. The causes of delayed diagnosis of cancer of the cervix in Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med 1986;32:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wedderburn M, Moore M. Qualitative assessment of attitudes aflecting childbirth choices of jamaican women. Working paper No. 5 prepared for the U.S. agency for international development. MotherCare project #936-5966. MotherCare project and manoff group. Arlington, VA: John Snow, Inc, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bamisaiye A. Selected factors influencing the coverage of an MCH clinic in Lagos, Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr 1984;30:256–61. 10.1093/tropej/30.5.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loumpet-Galitzine A. chefferies et royaumes Au Cameroun, 2015. Available: https://cm.ambafrance.org/Chefferies-et-royaumes-au-Cameroun [Accessed 1 Jun 2020].

- 21.World Health Organization . Health promotion. track 2: health literacy and health behaviour, 2009. Available: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/7gchp/track2/en/ [Accessed 28 May 2020].

- 22.Kim K, Han H-R. Potential links between health literacy and cervical cancer screening behaviors: a systematic review. Psychooncology 2016;25:122–30. 10.1002/pon.3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isa Modibbo F, Dareng E, Bamisaye P, et al. Qualitative study of barriers to cervical cancer screening among Nigerian women. BMJ Open 2016;6:e008533. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bazaz M, Shahry P, Latifi SM, et al. Cervical cancer literacy in women of reproductive age and its related factors. J Cancer Educ 2019;34:82–9. 10.1007/s13187-017-1270-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maree JE, Wright SCD, Makua TP. Men’s lack of knowledge adds to the cervical cancer burden in South Africa. Eur J Cancer Care 2011;20:662–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binka C, Doku DT, Nyarko SH, et al. Male support for cervical cancer screening and treatment in rural Ghana. PLoS One 2019;14:e0224692. 10.1371/journal.pone.0224692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kapambwe S, Mwanahamuntu M, Pinder LF, et al. Partnering with traditional Chiefs to expand access to cervical cancer prevention services in rural Zambia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019;144:297–301. 10.1002/ijgo.12750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenwald ZR, El-Zein M, Bouten S, et al. Mobile screening units for the early detection of cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2017;26:1679–94. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maseko FC, Chirwa ML, Muula AS. Client satisfaction with cervical cancer screening in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:420. 10.1186/1472-6963-14-420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abukari K, Pammla MP. Communication in nurse-patient interaction in healthcare settings in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Int J Africa Nurs Sci 2020;12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fargnoli V, Petignat P, Burton-Jeangros C. To what extent will women accept HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening? A qualitative study conducted in Switzerland. Int J Womens Health 2015;7:883–8. 10.2147/IJWH.S90772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berner A, Hassel SB, Tebeu P-M, et al. Human papillomavirus self-sampling in Cameroon: women's uncertainties over the reliability of the method are barriers to acceptance. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013;17:235–41. 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31826b7b51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets (transcripts) generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitivity of the data, but summaries of the transcripts are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.