Abstract

Background

It has been reported that neuropathic pain can be overcome by targeting the NR2B subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NR2B). This study aimed to investigate the effects of minocycline on phosphorylated and total expression of NR2B in the spinal cord of rats with diabetic neuropathic pain.

Methods

A total of 32 Sprague–Dawley male rats were randomly assigned into four groups (n = 8); control healthy, control diabetic (PDN), and PDN rats that received 80 µg or 160 µg intrathecal minocycline respectively. The rats were induced to develop diabetes and allowed to develop into the early phase of PDN for two weeks. Hot-plate and formalin tests were conducted. Intrathecal treatment of minocycline or normal saline was conducted for 7 days. The rats were sacrificed to obtain the lumbar enlargement region of the spinal cord (L4-L5) for immunohistochemistry and western blot analyses to determine the expression of phosphorylated (pNR2B) and total NR2B (NR2B).

Results

PDN rats showed enhanced flinching (phase 1: p < 0.001, early phase 2: p < 0.001, and late phase 2: p < 0.05) and licking responses (phase 1: p < 0.001 and early phase 2: p < 0.05). PDN rats were also associated with higher spinal expressions of pNR2B and NR2B (p < 0.001) but no significant effect on thermal hyperalgesia. Minocycline inhibited formalin-induced flinching and licking responses (phase 1: p < 0.001, early phase 2: p < 0.001, and late phase 2: p < 0.05) in PDN rats with lowered spinal expressions of pNR2B (p < 0.01) and NR2B (p < 0.001) in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusion

Minocycline alleviates nociceptive responses in PDN rats, possibly via suppression of NR2B activation. Therefore, minocycline could be one of the potential therapeutic antinociceptive drugs for the management of neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Minocycline, NR2B subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate, Painful diabetic neuropathy, Thermal hyperalgesia, Formalin test

Introduction

Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is characterised by several symptoms that can either be painful or painless. It can also lead to micro- and macro-vascular complications such as hypertension, nephropathy, and retinopathy. The most common symptom of DN is symmetrical sensory polyneuropathy, also known as painful diabetic neuropathy (PDN). Patients suffering from PDN may experience worsening sensations including spontaneous pain, hyperalgesia, and allodynia [1]. Furthermore, PDN is the most frequently manifested complication in advanced stages of type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). Despite the intensive clinical and experimental investigations, the underlying mechanisms of PDN remain unclear and controversial [2]. However, evidence to date attributed the occurrence of PDN to the neurochemical abnormalities occurring at the peripheral, spinal, and supraspinal levels [3].

Glial cells signal transduction that produce central sensitisation has been reported as one of the crucial pathomechanisms in PDN [4]. Microglia and astrocytes are considered to contribute to the development of neuropathic pain. Under normal condition, microglia cells act as the macrophages of the central nervous system (CNS) to engulf any debris and to combat any attacks from pathogens. During the course of neuropathic pain, it is believed that microglia cells play a major role during the early stage of pain as compared to astrocytes that contribute in the later stage [4, 5]. A previous study claimed that activated microglia would communicate with the spinal dorsal horn neurons to transmit aberrant nociceptive signals to induce central hypersensitivity [5]. Furthermore, the activation of microglia following nerve injury was found to lead to the release of several apoptotic and inflammatory cytokines as well as neuronal or glial cells excitatory substances. All these substances promote the activation of NR2B subunit of NMDA receptor (NR2B) that is known to be expressed on neurons and glial cells [4, 6]. Consequently, this results in an increase of the NMDA-mediated current. In short, the activation of NMDA receptors further stimulates the sensitisation of CNS and this is one of the most critical pathogenesis pathways in the development of PDN [7].

In view of the complicated pathogenesis, it is not easy to treat PDN. Although the prevalence of PDN is increasing over the years, there is still no effective therapy that can fully heal the PDN symptoms. In the last few years, a few published clinical trials have reported on the application of aldose reductase inhibitors [8, 9], antioxidants [10], or replacement of nerve growth factor [11] but the outcomes were not optimistic. In contrast, strict glycaemic control has been shown to alleviate this symptom [12]. In recent years, minocycline, an established semisynthetic antibiotic from the tetracycline family has attracted the attention of many researchers due to its potent anti-inflammatory effects in animal models for the treatment of ischaemia, Huntington disease, Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and multiple sclerosis [13]. Furthermore, recent emerging evidence revealed that the minocycline may alleviate the symptoms of neuropathic pain such as mechanical allodynia and hyperalgesia [14, 15]. A similar finding was demonstrated in our previous investigations [16, 17]. Moreover, minocycline has been found to possess a strong inhibitory effect against microglial activation thus explaining the possible alleviation of neuropathic pain symptoms, most likely via the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines released by the activated microglia during the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain [14, 15]. To the best of our knowledge, no study has explored the effects of minocycline on the phosphorylated and total NR2B subunits of N-methyl-D-aspartate on neuropathic pain models, especially on PDN models.

The increased glial cell activation, inflammatory cytokines release, and phosphorylation of NR2B subunit of NMDA receptor (pNR2B) expression have been demonstrated in the spinal cord during the pathogenesis of peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain [18, 19]. However, changes in the phosphorylated and total NR2B subunit of NMDA receptor expression in streptozotocin-induced type-1 PDN rats are unclear. Similarly, it is unknown if and how the administration of minocycline can prevent phosphorylation and the total number of NR2B expression. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the phosphorylation and the total number of NR2B expression as well as its association with formalin-induced flinching and licking responses during the early development of PDN. In addition, the study aimed to determine the effects of minocycline on these parameters during the pathogenesis of PDN in rat models. We hypothesised that the NR2B subunit activation would increase in correlation with the alleviated pain behaviour responses in the rat model.

Materials and methods

Animals

Thirty-two male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–230 g) were used. Rats were housed individually at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C with a light–dark cycle (light on 8:00 to 20:00) and were allowed free access to food and water. The rats were fasted for a minimum of 14 h to exert a maximal effect of STZ [20]. All the animals used in the present study strictly followed the regulations of housing and care as well as experimentation in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee, Universiti Sains Malaysia [USM/Animal Ethics Approval/2014 (91) (560)].

Early painful diabetic neuropathy model

The most common experimental model of diabetes, the STZ-induced diabetic rat, was used in this study. A single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (60 mg/kg; Sigma Aldrich, Germany) dissolved in ice-cold citrate buffer solution (pH 4.5) was conducted to induce diabetes in the rats. Meanwhile, the control rats were injected intraperitoneally with the iced-cold citrate buffer (pH 4.5) as a vehicle. Blood glucose levels, taken from the tail vein of the rats, were measured using a glucometer (Accu Chek Performa, Roche Diagnostics, Paris, France) before (Day 0; baseline) and three days later to confirm the diabetic status of the rats. Blood glucose level was also measured on Day 14 and Day 21 to confirm the hyperglycaemic condition of the diabetic rats. Only rats with blood glucose levels of more than 15 mmol/L were used as a diabetic model. The rats were allowed to develop diabetic neuropathy for two weeks post-STZ injection. Following that, tactile allodynia assessment was carried out to select rats with PDN. The rats with a reduction of more than 15% of paw withdrawal threshold from the baseline value two weeks post-STZ injection were included in this study [20]. In addition, the changes in body weight and total food intake throughout the experimental period were recorded.

Treatment protocol

In three weeks post-STZ injection, the rats were intrathecally injected with the following substances (n = 8 per group): i. saline (as a vehicle) given to non-diabetic (control) group, ii. saline given to diabetic control (PDN) groups, iii. minocycline (International Laboratory, USA) 80 µg/day (M 80) to PDN rats, and iv. minocycline 160 µg/day (M 160) to PDN rats. The direct intrathecal delivery of the treatment was conducted for seven continuous days based on the method of Lu and Schmidtko [21]. The rat was initially anaesthetised by a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen in a 1:4 ratio using an isoflurane anaesthesia meter. Once the pinch reflex was absent, the rat was placed in a supine position and the hair at the back of the rat was carefully shaved. The correct puncture site between L5 and L6 spinous process (cauda spina) was identified by grasping the iliac crests using the thumb and index finger of the left hand so that both of the hind legs could be moved downwards or upwards. The puncture site was sterilised using a 70% alcohol pad before a 30 ½ G needle containing 20 µL of the minocycline or vehicle (normal saline) was gently injected and slowly released into the region. The correct intrathecal injection was confirmed with the administration of lidocaine (2%, 20 µL) [22]. The reflexive flick or the formation of an S-shape by the tail following the intrathecal injection determined the correct intrathecal injection. Any rats demonstrating motor weakness or paralysis following the intrathecal injection were excluded from the study.

Formalin induced flinching and licking behaviour

On the fourth week following diabetic induction, all rats underwent a formalin test in which 50 μL of 5% formalin solution was injected at the intraplantar region of the right hind paw of the rat. The rat was immediately transferred into a Plexiglass chamber with a mirror placed at a 45◦ angle beneath the floor to allow an unobstructed view of the paw. The nociceptive behaviour responses, specifically licking and flinching responses, were recorded. Each episode of shaking or vibrating the injected paw or shuddering of the back or hind quarters was quantified as one flinch [23, 24]. The number of flinches was counted for the duration of one minute every 5 min, up to 60 min after the injection. Meanwhile, the duration of time (seconds) the rat spent licking the injected paw was recorded for up to 60 min. The data was then summed for phase 1 (acute pain and peripheral actions: 0 to 10 min post-formalin injection), early phase 2 (early chronic pain and central actions: 15 to 35 min), and late phase 2 (late chronic pain and central actions: 40 to 60 min) [25].

Sacrifice of the animals

The rats were deeply anaesthetised by an overdose intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbitone (Alfasan, Holland) on week 4 of experimentation. Following that, the lumbar enlargement region (1 cm length) of the spinal cord at ipsilateral and contralateral sides (L4-L6) were dissected for immunohistochemistry and western blotting purposes.

Immunohistochemistry

Eight rats from each group were used for this procedure. Thoracotomy was conducted and the heart was perfused with 300 mL of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) followed by 500 mL of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). The lumbar enlargement region of the spinal segments (L4-L5) was removed, post-fixed in the same fixative, and cryoprotected overnight in 20% sucrose in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.4. A total of 18 to 24 Sects. (40 µm thickness) were obtained using a freezing microtome. Every six to eight sections were collected in 0.1 M PBS and each set was immunohistochemically reacted for CD11b (microglial marker), NR2B, and phospho-NR2B subunit proteins. Immunohistochemical detection using the avidin–biotin peroxidase procedure was carried out. The sections were initially rinsed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) twice for 5 min each and incubated for 48 h with primary rabbit polyclonal for NR2B (1:500; Thermo-Scientific, USA), phospho-NR2B (pTyr 1336, 1:400; Thermo-Scientific, USA), or primary mouse monoclonal CD11b (1:500; Thermo-Scientific, USA) antibodies in a blocking solution containing 2% normal goat or horse serum and 0.2% Triton X-100, all diluted in TBS. After being washed in TBS-T, the sections were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit anti-serum, Rabbit ABC Staining System or horse anti-mouse, Mouse ABC Staining System, Thermo Scientific, USA) diluted in 1:200 for 1 h. Sections were then washed in TBS-T, incubated for 1 h in the avidin–biotin complex (Thermo Scientific, USA), and stained with 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (0.02% in TBS, 0.2% hydrogen peroxide; Thermo Scientific, USA) as a chromogen. Then, the sections were again washed in TBS, mounted on gelatin-subbed slides, air-dried, and coverslipped with DPX mounting (BDH, France). After that, the sections were observed under a light microscope whereby the images of six random sections were captured using a high-resolution image analyser (Leica MS 60, Japan) under 100 × magnification. The total number of protein expression was counted manually from laminae I to VI according to Molander [26]. The average of the six sections was taken from the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of each rat.

Western blotting

The expression of phospho-NR2B and total NR2B subunits were quantified by western blotting. Eight rats from the control, PDN, (M 80), and (M 160) experimental groups were used for this purpose. The rats were heart-perfused with 0.1 M PBS and the lumbar enlargement regions of the spinal cord (L4–L5) were immediately dissected out without a fixation process. Once dissected, they were cut in the middle into ipsilateral and contralateral regions. The tissues were then homogenised in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) that was freshly mixed with concentrated Halt™ Protease and Phosphatase cocktail kit (Pierce, USA) in a volume of 10 µL/mL per reagent.

The protein concentration was measured using Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assay (Thermofisher Scientific, USA) and adjustment was carried out to equalise protein concentration. Samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and 50 μg protein per lane was loaded, electrophoresed on 15% SDS-PAGE, and blotted onto the nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in either 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (for total NR2B subunit) or 5% skimmed milk (for phospho-NR2B subunit) in TBST for one hour and incubated for 12 to 18 h at 4 °C with polyclonal rabbit anti-NR2B antibody (1:1000 dilution in TBST) or polyclonal rabbit anti-phosphorylated NR2B subunit antibody (Tyr1336, 1:500 dilution in TBST). The membranes were washed and incubated in goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (dilution 1:5000 in TBST for NR2B and phospho-NR2B subunit) for one hour and rinsed in TBST. The signal was identified using a sensitive chemiluminescence reagent (Clarity ™ Western ECL Substrate (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). The antibodies against phosphorylated and total NR2B subunit were stripped by incubating the membranes with Restore™ Stripping buffer for 15 min. Following the blocking with 5% BSA, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C and the signal detection was conducted as previously mentioned. β-actin was used as an internal standard with mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (1:2000 dilution in TBST, Thermofisher Scientific, USA) as the primary antibody. Digital images of western blots were analysed by using the Spot Donso AlphaView™ software in the image analyser. The mean relative intensity of fold change was measured by the formula below:

Mean relative Intensity = (IDV NR2B subunit or phospho-NR2B subunit – IDV endogenous control) target group – (IDV NR2B subunit or phospho-NR2B subunit – IDV endogenous control)calibrator group.

Statistical analysis

SPSS statistics version 22 (IBM, Armonk, New York, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. The distribution of data was determined by histogram and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The data were normally distributed. Formalin-induced flinching response during phase 1, early phase 2, and late phase 2 as well as immunohistochemistry and western blotting on phosphorylated and total NR2B subunits expressions were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Scheffe’s test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was taken at p < 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The values were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or standard deviation (SD).

Results

Minocycline improves body weight in PDN rats

In general, there was a significant difference in the change of body weight between the groups (F3, 44) = 62.28, p < 0.001). In specific, PDN rats had a lower change in body weight compared to control rats (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -199.12 to -126.13). Interestingly, minocycline-treated PDN rats revealed significantly increased change in body weight compared to PDN group (p < 0.05, 95% CI: 1.161 to 73.34 and -0.64 to 72.42 for comparison between (M 80) and (M 160) with PDN group, respectively). No significant difference was detected in body weight change between the doses of minocycline in PDN rats (Table 1).

Table 1.

Change in body weight and total food intake throughout the experimentation between the groups. The values were presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation) (n=12)

| Group | Body weight (g) | Total food intake (g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 26 | Change in body weight | ||

| Control | 212.2 (38.43) | 336.55 (39.77) | 124.41 (31.77) | 590 (78.91) |

| PDN | 212.54 (25.56) | 174.3 (34.54) | -38.25 (33.1)*** | 702 (130.69) |

| (M 80) | 220.3 (35.86) | 219.3 (45.86) | -0.1 (51.18)***, # | 778 (125.4)## |

| (M 160) | 218.1 (31.34) | 215.74 (42.97) | -2.355 (41.93)***, # | 832 (112.31)### |

***p < 0.001 compared to control group, #p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 compared to PDN group

Minocycline increases total food consumption in PDN rats

A significant difference was detected in total food intake throughout the experimentation between the groups ((F3, 44) = 10.221, p < 0.001). Although no difference was identified in PDN group compared to control group in the total food consumption, minocycline-treated PDN rats consumed the food pellet higher than the control rats (p < 0.01, 95% CI: 53.58 to 323.26 between control and M 80; p < 0.001, 95% CI: 106.97 to 376.65 between control and M 160). No difference in the total food consumption detected between the groups which consumed different doses of minocycline (Table 1).

Minocycline gives no effect on thermal hyperalgesia but reduced formalin-induced nociceptive behaviour in PDN rats

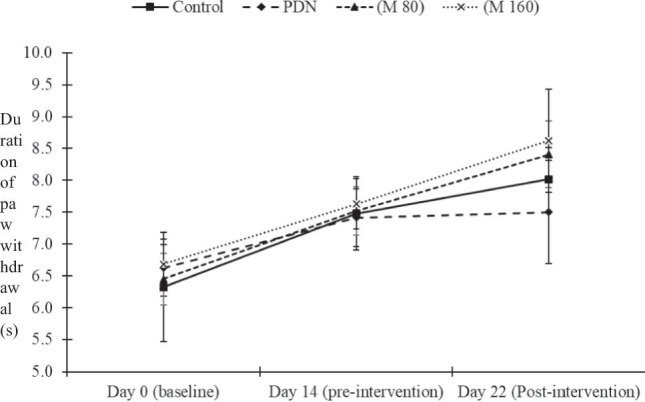

In hot-plate test, one-way repeated measures ANOVA exhibited no significant effect in thermal hyperalgesia as demonstrated in hot-plate test between the groups (F5.116, 75.032) = 0.222, p > 0.05 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Thermal hyperalgesia as indicated by hot-plate test in the groups. The data is expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (S. E. M.) (n = 12). No significant difference was detected between the groups

However, in formalin-induced flinching and licking behaviour responses, one-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between the groups during phase I ((F3, 44) = 20.857, p < 0.001 and (F3, 44) = 19.369, p < 0.001), early phase 2 ((F3, 44) = 26.237, p < 0.01 and (F3, 44) = 91.556, p < 0.001) and late phase 2 ((F3, 44) = 17.272, p < 0.001 and (F3, 44) = 4.582, p < 0.01, respectively). A significantly higher flinching response has been detected in PDN rats during phase 1 (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 18.49 to 67.51), early phase 2 (p < 0.01, 95% CI: 39.08 to 219.92) and late phase 2 (p < 0.01, 95% CI: 30.21 to 246.62) compared to control groups. Meanwhile, PDN rats produced a longer licking response compared to the control group during early phase 2 (p < 0.01, 95% CI: 23.73 to 173.77) (Fig. 2A and B).

Fig. 2.

Formalin-induced nociceptive flinching responses in the groups. The values are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (S. E. M.) (n = 12). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared with control group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 compared with PDN group, §§§p < 0.001 compared with (M 80) group

Interestingly, the treatment with minocycline at a higher dose (M 160) effectively reduced the flinching response compared to PDN group during phase 1 (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -89.84 to -40.83), early phase 2 (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -333.27 to -133.39) and late phase 2 (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -369.37 to -152.96). Similarly, the duration of licking response was significantly lower in (M 160) group during all phases (phase 1: p < 0.001, 95% CI: -117.14 to -22.49, early phase 2: p < 0.001, 95% CI: -251.01 to -184.79 and late phase 2: p < 0.05, 95% CI: -113.23 to -8.01, compared with PDN group). Treatment with a lower dose of minocycline (M 80) prominently lowered the flinching response and duration of licking response during phase 1 (p < 0.01, 95% CI: -55.67 to -6.66) and p < 0.001, 95% CI: -80.71 to -37.96) and early phase 2 (p < 0.01, 95% CI: -120.27 to -25.73 and p < 0.001, 95% CI: -304.64 to -150.53) compared to PDN (Fig. 2A and B).

Minocycline reduced the expression of phosphorylated NR2B in spinal cord of PDN rat

One-way ANOVA revealed strong implications in phosphorylation of NR2B subunit of NMDAR (pNR2B) between the groups from the results of immunohistochemistry (IHC) ((F3, 20) = 48.623, p < 0.001) and western blot (WB) ((F3, 20) = 36.284, p < 0.001) analyses. The similar significant difference was detected in the pNR2B expressions at the contralateral region of the spinal cord as revealed by IHC ((F3, 20) = 34.236, p < 0.001) and WB ((F3, 20) = 34.303, p < 0.001) analyses. Post hoc Dunnett’s T3 demonstrated that the expression of pNR2B was prominently higher in PDN group compared to control group especially as shown in western blot analysis at both ipsilateral (p < 0.05, 95% CI: 0.191 to 1.17) (Fig. 3) and contralateral regions (p < 0.05, 95% CI: 0.005 to 0.491) of the spinal cord (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The total number of phosphorylated NR2B subunit of NMDAR (pNR2B) (A) and mean relative pNR2B protein level (B) in the ipsilateral region of spinal cord in the groups. The values are expressed in mean ± standard error of mean (S. E. M.). Minocycline significantly lowered the expressions of pNR2B in dose-dependent manner in the spinal cord of PDN rats. Arrows indicate the expression of pNR2B (400X magnification). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to control group, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 compared to PDN group and §§p < 0.01 compared to (M 80) group

Fig. 4.

The total number of phosphorylated NR2B subunit of NMDAR (pNR2B) (A) and mean relative pNR2B protein level (B) in the contralateral region of spinal cord in the groups. The values are expressed in mean ± standard error of mean (S. E. M.). The reduced pNR2B expressions was detected in minocycline-treated groups in dose-dependent manner in the spinal cord of PDN rats. Arrows indicate the expression of pNR2B (400X magnification). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to control group, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 compared to PDN group

The intrathecal administration of minocycline at lower and higher doses markedly reduce the pNR2B in the spinal cord of PDN rats ipsilateral (in IHC, p < 0.01, 95% CI: -1264.89 to -428.386 and p < 0.01, 95% CI: -1.42 to -0.46; in WB, p < 0.001, 95% CI: -154.49 to -711.01 and p < 0.01, 95% CI: -1.5 to -0.52 for comparison between M 80 and M 160 with PDN groups, respectively) (Fig. 3). The similar reduction of pNR2B expression was detected in M80 and M 160 groups compared to PDN and control groups in the contralateral region of the spinal cord as demonstrated in IHC (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -907.71 to -310.29 between M80 and PDN groups, p < 0.001, 95% CI: -787.46 to -196.04 between M 80 and control groups; p < 0.001, 95% CI: -1169.84 to -578.41 between M160 and PDN groups, p < 0.001, 95% CI: -1049.59 to -458.16 between M 160 and control groups) and WB results (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -0.82 to -0.338 for comparison between M 80 to PDN groups, p < 0.01, 95% CI: -0.576 to -0.09 between M 80 and control groups; p < 0.001, 95% CI: -0.98 to -0.49 between M 160 and PDN groups, p < 0.001, 95% CI: -0.73 to -0.243 between M 160 and control groups) (Fig. 4).

Minocycline suppressed the expressions of total NR2B subunit of NMDAR in PDN rats

The results exhibited a significant increase in total NR2B subunit of NMDA receptor (NR2B) expression detected between the groups both at ipsilateral ((F3, 20) = 144.622, p < 0.001 for IHC and (F3, 20) = 10.236, p < 0.001 for WB) and contralateral ((F3, 20) = 64.079, p < 0.001 for IHC and (F3, 20) = 9.168, p < 0.01 for WB)) regions of the spinal cord.

The higher expression of NR2B was detected in PDN group on ipsilateral (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 505.16 to 891.34 for IHC and p < 0.01, 95% CI: 0.311 to 1.82 for WB) (Fig. 5) and on contralateral (p < 0.001, 95% CI: 322.39 to 856.49 for IHC and p < 0.05, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.7337 for WB) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

The total number of NR2B subunit of NMDAR (NR2B) (A) and mean relative NR2B protein level (B) in the ipsilateral region of spinal cord in the groups. The values are expressed in mean ± standard error of mean (S. E. M.). Minocycline significantly reduced the expressions of NR2B in dose-dependent manner in the spinal cord of PDN rats. Arrows indicate the expression of NR2B (400X magnification). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to control group, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 compared to PDN group and §§p < 0.01 compared to M 80 group

Fig. 6.

The total number of NR2B subunit of NMDAR (NR2B) (A) and mean relative NR2B protein level (B) in the contralateral region of spinal cord in the groups. The values are expressed in mean ± standard error of mean (S. E. M.). Minocycline significantly lowered the expressions of NR2B in dose-dependent manner in the spinal cord of PDN rats. Arrows indicate the expression of NR2B (400X magnification). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to control group, #p < 0.05 and ###p < 0.001 compared to PDN group

Minocycline-treated PDN rats showed prominently lower NR2B expression in a dose-dependent manner at the ipsilateral region (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -1161.09 to -774.91 for IHC and p < 0.05, 95% CI: -1.68 to -0.17 for WB, between M 80 and PDN groups; p < 0. 001, 95% CI: -1493.09 to -1106.91 for IHC and p < 0.01, 95% CI: -2.02 to -0.508 for WB, between M 160 and PDN groups) (Fig. 5). The similar lower NR2B expression was also detected in minocycline-treated PDN groups at the contralateral region in a dose-dependent manner (p < 0.001, 95% CI: -1193.49 to -659.51 for IHC and p < 0.05, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.734 for WB, between M 80 and PDN groups; p < 0.001, 95% CI: -1440.86 to -905.89 for IHC and p < 0.05, 95% CI: -1.25 to -1.805 for WB, between M 160 and PDN groups) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Hyperalgesia and allodynia are observed in a considerable number of patients with DM. Both conditions result in highly devastating pain. The main objective of this study was to determine the effect of minocycline on pain behaviour responses and the expression of the phosphorylated and total number of NR2B subunits in the spinal cord of rats at the early phase of PDN. The formalin-induced behaviour responses, especially the flinching response, were robust during phase 1 but reduced during the quiescent period. However, it was enhanced again during phase 2, as similarly demonstrated in previous studies [24, 27, 28]. The PDN rats showed increased flinching and licking responses following formalin injection, thus indicating the occurrence of hypersensitivity following formalin injection. This observation echoed the findings in Pabreja et al. [14] and Babaei et al. [24]. Apart from that, the immediate release of neurotransmitters glutamate, aspartate, and substance P right after the formalin injection in the spinal cord [29] could explain the robust licking and flinching behaviour during phase 1. Meanwhile, the prominent enhancement of flinching and licking responses in PDN rats during phase 2 was possibly related to the ongoing signals from the periphery and the increased activity of the spinal dorsal horn neurons even without the additional production of primary afferent neurotransmitters [29]. Previous studies also supported the postulation that the peripheral activities during phase 1 were responsible for the activation of spinal glutamatergic and peptidergic receptors. These activated receptors led to the full development of the central modifications during phase 2 responsible for the amplification of spinal nociceptive processing [28, 30]. One postulated mechanism of the central modifications during phase 2 is the extended-release of pro-inflammatory prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in the spinal cord [28]. Interestingly, treatment with minocycline successfully alleviated the formalin-induced flinching and licking responses in PDN rats, possibly via the inhibition of microglial activation and the subsequent release of pro-inflammatory mediators [14, 16]. Furthermore, minocycline was also associated with the inhibition of the release of PGE2 from the activated microglia via the suppression of TLR2 and TLR4 signalling, both of which are needed for the development of allodynia, hyperalgesia, and spontaneous pain in the event of peripheral nerve damage [31, 32].

Our previous investigation revealed prominent development of tactile allodynia in PDN rats during the early stage. However, the current study revealed no significant development of thermal hyperalgesia during the early stage of PDN. In comparison, a few other studies reported the development of thermal hyperalgesia in PDN rats, especially during later stages [33, 34]. The lack of thermal hyperalgesia development in this study was in line with Malcangio and Tomlinson [35] and DeLeo et al. [36]. Compared to other types of neuropathic pain, different types of peripheral nerves may be selectively impaired during the early stage of PDN [35]. This could be possibly due to the vascular damage that occurs during the pathogenesis of PDN, thus leading to nerve denervation [37]. Moreover, thermal nociceptive activation does not induce as much mechanoreceptor compared to other types of nociceptive stimuli [38]. It is possible that the destruction of low threshold mechanoreceptors or demyelination in diabetic rats could have contributed to reduced functional mechanoreceptors available in the detection of thermal stimuli. Furthermore, some inhibitory controls may become dysfunctional and exaggerate these effects [35]. In addition, substance P that is involved in the development of nerve injury-related thermal hyperalgesia is reduced in the spinal cord of diabetic rats [35]. By taking this into account, the non-occurrence of thermal hyperalgesia during the early course of PDN can be explained. Having said so, some previous studies demonstrated the inconsistent effects of minocycline on thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain models. Abu-Ghefreh and Masocha [39] and Sung et al. [40] showed the effectiveness of minocycline in minimising thermal hyperalgesia in rat models of inflammation and monoarthritis. Meanwhile, Pabreja et al. [14] demonstrated no effect of minocycline on thermal hyperalgesia, even though the duration of experimentation and administration was similar to our study in which minocycline was given chronically for two weeks following the development of PDN in the rats.

In both immunohistochemistry and western blotting analyses, the expressions of the phosphorylated and total number of NR2B were significantly higher in diabetic rats with PDN following the injection of 5% formalin. In studies without the challenge of formalin injection, the phosphorylation of NR2B subunit was also found to increase in the spinal cord dorsal horn of PDN rats with type 2 DM [41] and rats with spinal nerve ligation-induced neuropathic pain [42]. The injection of 5% formalin in this study was aimed to exaggerate the nerve injury that might have already occurred in the PDN rats [43]. Therefore, it is agreed that the increased phosphorylation of NMDA receptors is critical for the development of central sensitisation induced by nerve damage, as revealed in the neuropathic pain model of L5 spinal nerve transection [44]. It is also supported by Liu et al. [45] that diseases leading to peripheral nerve injury such as PDN may increase the tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2B in the spinal dorsal horn without affecting the total NR2B protein level. In addition, the activation of cells in the lateral hypothalamic area that contains many NMDA receptors, including NR2B, may explain the increased feeding behaviour in PDN rats [46]. Even though the weight of the PDN rats was not significantly different from the control rats in the present study, the effect was still visible via the change of body weight in the PDN rat. However, since the rats were diabetic, the excessive weight loss could have been implicated by other factors associated with diabetes itself. Insulin deficiency that resulted from pancreatic β-cell destruction results in chronic hyperglycaemia that contributes to decreased protein synthesis, increased release of amino acids from the muscle, reduced glucose uptake by the muscle and adipose tissue, as well as delayed growth in diabetic rats [47]. We found that minocycline was incapable of reversing the body weight and total food intake in PDN rats, as similarly reported by Sun et al. [48]. The metabolic effect of diabetes is possibly stronger than the incapability of minocycline in correcting the body weight loss. However, several molecular modifications may be implicated and further investigation is warranted to identify this postulated mechanism.

In addition, the intrathecal administration of minocycline was found to strongly inhibit the NR2B phosphorylation of tyrosine residue (pTyr1336) of the NR2B subunit in the spinal cord of the PDN rats in a dose-dependent manner. It was associated with the prominent inhibition of activated microglia in the spinal cord of PDN rats by minocycline as demonstrated in our previous investigation [16]. Another explanation of the higher pNR2B expression at Tyr1336 in PDN rats was related to the activation of Janus Kinase 2/Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription 3 (JAK2/STAT3) as revealed by Tang et al. [49] and Zhou et al. [22], but not STAT1 [13]. The activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway is reported to be induced by microglia and astrocytes during the pathogenesis of chronic and neuropathic pain [50]. Moreover, it is proven by Li et al. [4] that the expression of phosphorylated JAK2, phosphorylated STAT3, caveolin-1 (CAV1), and pNR2B was upregulated in the spinal cord of PDN rats. As phosphorylated STAT3 is believed to be mainly expressed in activated microglia that is relatively persistent for two weeks following the development of PDN [4], therefore it is highly inferred that the reduction in flinching and licking responses following formalin injection in minocycline-treated PDN rats can be associated with the inhibition of activated microglia by minocycline.

Furthermore, our previous investigation also revealed that minocycline could inhibit the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the spinal cord of PDN rats [16], possibly via the inhibition of microglial activation. BDNF is one of the signalling nociceptive markers that plays a critical role in the development of pain. It is released by activated microglia. In addition, it has been demonstrated that BDNF may contribute to the phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit, thus resulting in its activation by upregulating the phosphorylation of tyrosine-kinase B (TrkB) [51]. Apart from that, the binding of BDNF to TrkB receptors may lead to the downregulation of voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels. The activity of these channels contributes to an elevated frequency of firing and broadening action potential. Eventually, this mechanism activates the NR2B subunit via the increased Ca2+ influx and glutamate release and results in increased neuronal excitability [52]. The administration of minocycline can halt these mechanisms and therefore, inhibit the phosphorylation of the NR2B subunit and subsequently reduce the spinal hypersensitivity.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrated that formalin-induced flinching and licking responses were enhanced without any development of thermal hyperalgesia during the early phase of PDN. The increased nociceptive behaviour responses are possibly associated with the increased phosphorylation and total expression of NR2B subunit in the spinal cord of PDN rats. The intrathecal administration of minocycline strongly reduced the phosphorylated and total NR2B subunit expression, thus possibly explaining the reduced formalin-induced flinching and licking responses observed in PDN rats. Furthermore, this study provides insights regarding the role of spinal-activated microglia in the pathogenesis of PDN that leads to the enhanced hypersensitivity responsible for the development of tactile allodynia. However, no development of thermal hyperalgesia was observed during the early course of PDN. In summary, minocycline could be one of the potential therapeutic drugs for the treatment of PDN. Further studies are needed to determine the effects of minocycline on patients with PDN to identify its effectiveness in human subjects.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Universiti Sains Malaysia and Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia for the funding provided; Research University grant numbered RUI 1001/PPSK/812139 and Fundamental Research Grant Scheme numbered 203/PPSK/6171189. We also thank the staffs of Physiology Laboratory, Animal Research and Service Center, Central Research Laboratory, Cranial and Maxillofacial and Molecular and Molecular Laboratory for the direct and indirect technical guides.

Author’s contribution

Ismail CAN is responsible for the whole manuscript including figures and table. Ghazali AK guides on statistical analyses of the experimental data. Suppian R and Ab Aziz CB are responsible for proofreading and improving the quality of the manuscript. Long I provides research funding and finalizes the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded under Research University (RUI) grant (1001/PPSK/812139) by Universiti Sains Malaysia and Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) (203/PPSK/6171189) by Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia.

Data Availability

All the data are shown in the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All the experimentation of the study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee, Universiti Sains Malaysia [USM/Animal Ethics Approval/2014 (91) (560)].

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Talbot S, Chahmi E, Dias JP, Couture R. Key role for spinal dorsal horn microglial kinin B 1 receptor in early diabetic pain neuropathy. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sima AA. Diabetic neuropathy in type 1 and type 2 diabetes and the effects of C-peptide. J Neurol Sci. 2004;220:133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreiber AK, Nones CF, Reis RC, Chichorro JG, Cunha JM. Diabetic neuropathic pain: physiopathology and treatment. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:432. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i3.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C-D, Zhao J-Y, Chen J-L, Lu J-H, Zhang M-B, Huang Q, Cao Y-N, Jia G-L, Tao Y-X, Li J, Cao H. Mechanism of the JAK2/STAT3-CAV-1-NR2B signaling pathway in painful diabetic neuropathy. Endocrine. 2019;64:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-01880-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark AK, Gruber-Schoffnegger D, Drdla-Schutting R, Gerhold KJ, Malcangio M, Sandkühler J. Selective activation of microglia facilitates synaptic strength. J Neurosci. 2015;35:4552–70. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2061-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kaindl AM, Degos V, Peineau S, Gouadon E, Chhor V, Loron G, Charpentier TL, Josserand J, Ali C, Vivien D, Collingridge GL, Lombet A, Issa L, Rene F, Loefflier J-P, Kawellars A, Verney C, Mantz J, Gressens P. Activation of microglial N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors triggers inflammation and neuronal cell death in the developing and mature brain. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:536–549. doi: 10.1002/ana.23626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji R-R, Berta T, Nedergaard M. Glia and pain: is chronic pain a gliopathy? Pain®. 2013; 154 Suppl:S10–28. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Ramirez MA, Borja NL. Epalrestat: an aldose reductase inhibitor for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:646–655. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.5.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotta N, Akanuma Y, Kawamori R, Matsuoka K, Oka Y, Shichiri M, Toyota T, Nakashima M, Yoshimura I, Sakamoto N, Shigeta Y. Long-term clinical effects of epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor, on diabetic peripheral neuropathy: the 3-year, multicenter, comparative Aldose Reductase Inhibitor-Diabetes Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1538–1544. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziegler D, Hanefeld M, Ruhnau K, Mei H, Lobisch M, Schűtte K, Gries FA. Treatment of symptomatic diabetic peripheral neuropathy with the anti-oxidant α-lipoic acid. Diabetologia. 1995;38:1425–1433. doi: 10.1007/BF00400603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apfel SC, Schwartz S, Adornato BT, Freeman R, Biton V, Rendell M, Vinik A, Giuliani M, Stevens C, Barbano R, Dyck PJ. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human nerve growth factor in patients with diabetic polyneuropathy: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:2215–2221. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.17.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickup J, Mattock M, Kerry S. Glycaemic control with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion compared with intensive insulin injections in patients with type 1 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials Br Med J. 2002;324. 10.1136/bmj.324.7339.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Nikodemova M, Watters JJ, Jackson SJ, Yang SK, Duncan ID. Minocycline down-regulates MHC II expression in microglia and macrophages through inhibition of IRF-1 and protein kinase C (PKC) α/βII. J Bio Chem. 2007;282:15208–15216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pabreja K, Dua K, Sharma S, Padi SS, Kulkarni SK. Minocycline attenuates the development of diabetic neuropathic pain: possible anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;661:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moini-Zanjani T, Ostad S-N, Labibi F, Ameli H, Mosaffa N, Sabetkasaei M. Minocycline effects on IL-6 concentration in macrophage and microglial cells in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Iran Biomed J. 2016;20:273–79. 10.22045/ibj.2016.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Ismail CAN, Suppian R, Ab Aziz CB, Long I. Minocycline attenuates the development of diabetic neuropathy by modulating DREAM and BDNF protein expression in rat spinal cord. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019;18:181–190. doi: 10.1007/s40200-019-00411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ismail CAN, Suppian R, Ab Aziz CB, Long I. Minocycline and Ifenprodil Prevent Development of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy in Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Rat Model. Int J Life Sci. 2018;6:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang L-E, Guo S-H, Thitiseranee L, Yang Y, Zhou Y-F, Yao Y-X. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subtype 2B antagonist, Ro 25–6981, attenuates neuropathic pain by inhibiting postsynaptic density 95 expression. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7848. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26209-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y, Zhang K, Miao J, Zhao P, Lv M, Li J, Fu Z, Luo X, Zhu P. The spinal NR2BR/ERK2 pathway as a target for the central sensitization of collagen-induced arthritis pain. PLoS ONE. 2018 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daulhac L, Mallet C, Courteix C, Etienne M, Duroux W, Privat A-M, Sechalier A, Fialip J. Diabetes-induced mechanical hyperalgesia involves spinal mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in neurons and microglia via N-methyl-D-aspartate-dependent mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1246–1254. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu R, Schmidtko A. Direct intrathecal drug delivery in mice for detecting in vivo effects of cGMP on pain processing. In: Guanylate Cyclase and Cyclic GMP: Methods and Protocol. Springer; 2013. pp 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhou R, Xu T, Liu X, Chen Y, Kong D, Tian H, Yue M, Huang D, Zeng J. Activation of spinal dorsal horn P2Y13 receptors can promote the expression of IL-1β and IL-6 in rats with diabetic neuropathic pain. J Pain Res. 2018;11:615. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S154437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wheeler-Aceto H, Cowan A. Standardization of the rat paw formalin test for the evaluation of analgesics. Psychopharmacology. 1991;104:35–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02244551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babaei BF, Zare S, Heydari R, Farokhi F. Effects of melatonin and vitamin E on peripheral neuropathic pain in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2010;2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long I, Suppian R, Ismail Z. The effects of pre-emptive administration of ketamine and norbni on pain behavior, c-fos, and prodynorphin protein expression in the rat spinal cord after formalin-induced pain is modulated by the dream protein. Korean J Pain. 2013;26:255–264. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molander C, Xu Q, Grant G. The cytoarthritic organization of the spinal cord in the rat. I. The lower throacic and lumboscaral cord. J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:133–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Juárez-Rojop IE, Granados-Soto V, Díaz-Zagoya JC, Glores-Murrieta FJ, Torres-López JE. Involvement of cholecystokinin in peripheral nociceptive sensitization during diabetes in rats as revealed by the formalin response. Pain. 2006;122:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freshwater JD, Svensson CI, Malmberg AB, Calcutt NA. Elevated spinal cyclooxygenase and prostaglandin release during hyperalgesia in diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2002;51:2249–2255. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. Cyclooxygenase inhibition and the spinal release of prostaglandin E2 and amino acids evoked by paw formalin injection: a microdialysis study in unanesthetized rats. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2768–2776. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02768.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto T, Yaksh TL. Comparison of the antinociceptive effects of pre-and posttreatment with intrathecal morphine and MK801, an NMDA antagonist, on the formalin test in the rat. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:757–763. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199210000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim D, Kim MA, Cho I-H, Kim MS, Lee S, Jo E-K, Choi S-Y, Park K, Kim JS, Akira S, Na HS, Oh SB, Lee SJ. A critical role of toll-like receptor 2 in nerve injury-induced spinal cord glial cell activation and pain hypersensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14975–14983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bastos LF, Godin AM, Zhang Y, Jarussophon S, Ferreira BC, Machado RR, Maier SF, Konishi Y, de FreitasRP, Fiebich BL, Watkins LR, Coelho MM, Moraes MFD. A minocycline derivative reduces nerve injury-induced allodynia, LPS-induced prostaglandin E2 microglial production and signaling via toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Neurosci Lett. 2013;543:157–62. 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Anjaneyulu M, Chopra K. Quercetin, a bioflavonoid, attenuates thermal hyperalgesia in a mouse model of diabetic neuropathic pain. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1001–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00160-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma S, Kulkarni SK, Agrewala JN, Chopra K. Curcumin attenuates thermal hyperalgesia in a diabetic mouse model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;536:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malcangio M, Tomlinson DR. A pharmacologic analysis of mechanical hyperalgesia in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Pain. 1998;76:151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeLeo JA, Coombs DW, Willenbring S, Colburn RW, Fromm C, Wagner R, Twitchcll BB. Characterization of a neuropathic pain model: sciatic cryoneurolysis in the rat. Pain. 1994;56:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tesfaye S, Malik R, Ward J. Vascular factors in diabetic neuropathy. Diabetologia. 1994;37:847–854. doi: 10.1007/BF00400938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Besson J-M, Chaouch A. Peripheral and spinal mechanisms of nociception. Physiol Rev. 1987;67:67–186. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abu-Ghefreh AAA, Masocha W. Enhancement of antinociception by coadminstration of minocycline and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin in naïve mice and murine models of LPS-induced thermal hyperalgesia and monoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;1:276. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sung C-S, Cherng C-H, Wen Z-H, Chang W-K, Huang S-Y, Lin S-L, Chan K-H, Wong C-S. Minocycline and fluorocitrate suppress spinal nociceptive signaling in intrathecal IL-1β–induced thermal hyperalgesic rats. Glia. 2012;60:2004–2017. doi: 10.1002/glia.22415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dang J-K, Wu Y, Cao H, Meng B, Huang C-C, Chen G, Li J, Song X-J, Lian Q-Q. Establishment of a rat model of type II diabetic neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15:637–646. doi: 10.1111/pme.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morel V, Pickering G, Etienne M, Dupuis A, Privat AM, Chalus M, Eschalier A, Daulhac L. Low doses of dextromethorphan have a beneficial effect in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Fund Clin Pharmacol. 2014;28:671–680. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandireddy R, Yerra VG, Areti A, Komirishetty P, Kumar A. Neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic neuropathy: futuristic strategies based on these targets. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;674987:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2014/674987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abe T, Matsumura S, Katano T, Mabuchi T, Takagi K, Xu L, Yamamoto A, Hattori K, Yagi T, Watanabe M, Nakazawa T, Yamamoto T, Mishina M, Nakai Y, Ito S. Fyn kinase-mediated phosphorylation of NMDA receptor NR2B subunit at Tyr1472 is essential for maintenance of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;2:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu XJ, Gingrich JR, Vargas-Caballero M, Dong YN, Sengar A, Beggs S, Wang S-H, Ding HK, Frankland PW, Salter MW. Treatment of inflammatory and neuropathic pain by uncoupling Src from the NMDA receptor complex. Nat Med. 2008;14:1325. doi: 10.1038/nm.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan AM, Curràs MC, Dao J, Jamal FA, Turkowski CA, Goel RK, Giliard ER, Wolfsohn SD, Stanley BG. Lateral hypothalamic NMDA receptor subunits NR2A and/or NR2B mediate eating: immunochemical/behavioral evidence. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;276:R880–R891. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.3.R880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aronoff SL, Berkowitz K, Shreiner B, Want L. Glucose metabolism and regulation: beyond insulin and glucagon. Diabetes Spect. 2004;17:183–190. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.17.3.183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun JS, Yang YJ, Zhang YZ, Huang W, Li ZS, Zhang Y. Minocycline attenuates pain by inhibiting spinal microglia activation in diabetic rats. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:2677–2682. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang J, Li Z-H, Ge S-N, Wang W, Mei X-P, Wang W, Mei X-P, Wang W, Zhang T, Xu L-X, Li J-L. The inhibition of spinal astrocytic JAK2-STAT3 pathway activation correlates with the analgesic effects of triptolide in the rat neuropathic pain model. Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/185167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salaffi F, Giacobazzi G, Di Carlo M. Chronic pain in inflammatory arthritis: mechanisms, metrology, and emerging targets—a focus on the JAK-STAT pathway. Pain Res Manag. 2018;1–14. 10.1155/2018/8564215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Carreño FR, Walch JD, Dutta M, Nedungadi TP, Cunningham JT. BDNF-TrkB pathway mediates NMDA receptor NR2B subunit phosphorylation in the supraoptic nuclei following progressive dehydration. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo W, Robbins MT, Wei F, Zou S, Dubner R, Ren K. Supraspinal brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling: a novel mechanism for descending pain facilitation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:126–37. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3686-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are shown in the manuscript.