Key Points

Reduced-intensity melphalan-based conditioning provides the best survival in older AML patients undergoing stem cell transplantation.

A more intense myeloablative conditioning regimen does not provide a survival benefit in these patients.

Abstract

The optimal conditioning regimen for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) remains unclear. In this study, we compared outcomes of AML patients >60 years of age undergoing allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation at our institution. All 404 consecutively treated patients received 1 of the following conditioning regimens: (1) fludarabine+melphalan 100 mg/m2 (FM100), (2) fludarabine+melphalan 140 mg/m2 (FM140), (3) fludarabine+IV busulfan AUC ≥ 5000/d × 4 d (Bu≥20000), and (4) fludarabine+IV busulfan AUC 4000/d × 4 d (Bu16000). A propensity score analysis (PSA) was used to compare outcomes between these 4 groups. Among the 4 conditioning regimens, the FM100 group had a significantly better long-term survival with 5-year progression-free survival of 49% vs 30%, 34%, and 23%, respectively. The benefit of the FM100 regimen resulted primarily from the lower nonrelapse mortality associated with this regimen, an effect more pronounced in patients with lower performance status. The PSA confirmed that FM100 was associated with better posttransplantation survival, whereas no significant differences were seen between the other regimen groups. In summary, older patients with AML benefited from a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen with lower melphalan doses (FM100), which was associated with better survival, even though it was primarily used in patients who could not receive a more intense conditioning regimen.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHCT) is a potential curative treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, the higher toxicity associated with myeloablative conditioning (MAC) has limited the application to younger and fit individuals. Given that the median age of patients with AML is >60 years of age, most patients with this disease are not eligible for conventional MAC. In an effort to reduce nonrelapse mortality (NRM) and extend AHCT to older or unfit patients, a major step forward was the introduction of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens,1,2 in which tumor eradication relies primarily on the graft-versus-tumor effect.3,4

During the past decade, several RIC regimens have been developed, usually combining a purine analog, primarily fludarabine, with an alkylating agent. These RIC regimens have provided long-term survival ranging between 30% and 60%5-12; however, the optimal RIC regimen for older patients with AML remains unclear.

In this study, we compared outcomes of a large cohort of older patients with AML who received AHCT conditioning with 4 different regimens, including fludarabine and melphalan (FM) and fludarabine with busulfan (FB), using multiple propensity score analyses (PSAs) to determine the true impact of these regimens on transplant outcomes and to learn whether there is an optimal conditioning regimen for older patients with this disease.

Study design

Data from consecutive patients with AML, ≥60 years of age, having undergone the first AHCT at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from January 2005 through August 2018 were analyzed. The primary outcome was progression-free survival (PFS), whereas graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)–free, relapse-free survival (GRFS), NRM, and relapse were secondary outcomes. Patients received 1 of the 4 conditioning regimens: (1) fludarabine 160 mg/m2+melphalan 100 mg/m2 (FM100); (2) fludarabine 160 mg/m2+melphalan 140 mg/m2 (FM140); (3) fludarabine (with or without clofarabine) 160 mg/m2+IV busulfan × 4 d (area under the curve [AUC] ≥ 5000 μmol/min per day; equivalent dose 130 mg/m2 per day [Bu≥20000]); and (4) fludarabine (with or without clofarabine) 160 g/m2+IV busulfan × 4 days (AUC 4000 μmol/min per day; equivalent dose 110 mg/m2 per day [Bu16000]).

The GVHD prophylaxis regimen for haploidentical transplants included high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil, whereas tacrolimus and methotrexate, with or without anti-thymocyte globulin, were used in matched related and unrelated donor transplantations.

To adjust for potential selection bias in choices of conditioning regimen in a nonrandomized study, multiple propensity scores (PSs) were calculated by multinomial logistic regression. Factors included in the PS calculation were age, sex, Karnofsky performance status (KPS), secondary/therapy-related AML, European LeukemiaNet 2017 (ELN2017) genetic risk,13 remission status before transplant, induction failure, donor type, stem cell source, patient and donor cytomegalovirus serostatus, and transplant protocol (treatment in a clinical trial vs standard of care). Multiple PSs were then used as covariates in a multivariable Cox regression model to adjust the impact of conditioning type on outcomes of interest. More details on the statistical analyses are summarized in supplemental Material 1, available on the Blood Web site.

Although several methods of PSA have been introduced, such as PS matching, stratification, or regression analysis with PS adjustment, matching and stratification on multiple PSs can be difficult to conduct in practice, especially when the number of treatments compared is >2, as this may result in very small groups. Therefore, in this study, we used multiple PS-adjusted regression analysis to help obtain meaningful results without losing statistical power.

The Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center approved a retrospective data review protocol for this analysis.

Results and discussion

A total of 404 elderly patients with AML were included in the analysis: 89, 78, 131, and 106 received FM100, FM140, Bu≥20000, and Bu16000, respectively. Median follow-ups of survivors were 40, 74, 30, and 44 mo, respectively (P = .06). Baseline characteristics of the patients in each conditioning group were well balanced after adjustment for multiple PSAs (supplemental Table 1).

Results are presented for the FM100, FM140, Bu≥20000, and Bu16000 regimens.

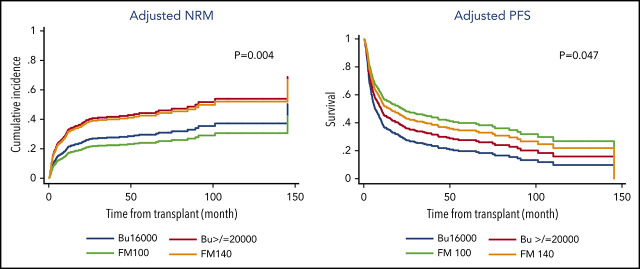

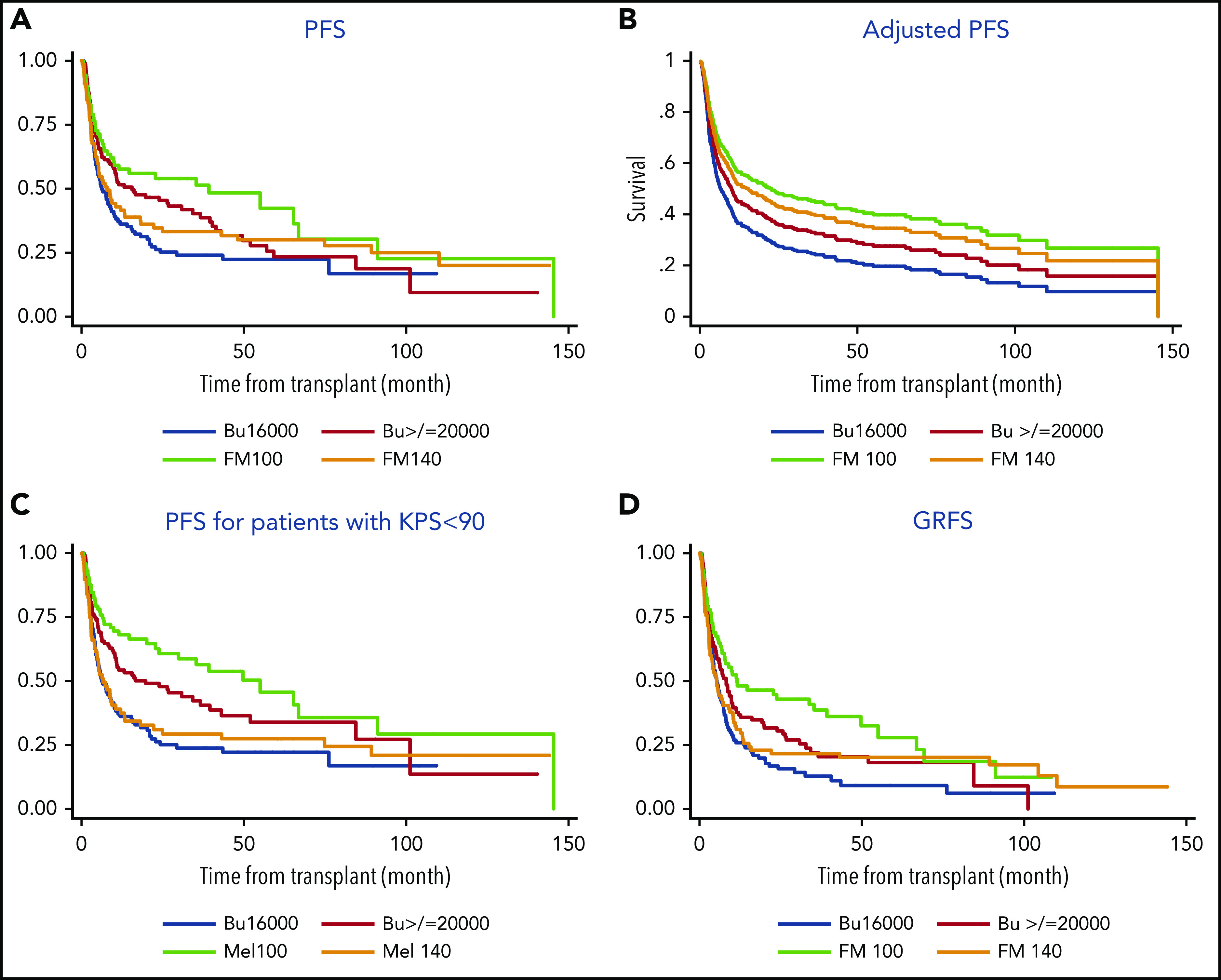

NRMs at 3 years were 19%, 39%, 35%, and 21% (P = .06), and 3-year relapse rates were 32%, 32%, 30%, and 55% (P = .003). Among the 4 treatment groups, the FM100 group had a significantly better PFS and GRFS. Five-year PFSs for these 4 groups were 49%, 30%, 34%, and 23% (P = .02), and 5-year GRFSs were 28%, 20%, 18%, and 9% (P = .006; Figure 1). The benefit of the FM100 regimen was even more pronounced in patients with low performance status, in the >65-year age group, as well as in those without active disease before the transplantation. In the subgroup of patients with KPS <90%, 5-year PFSs were 41%, 27%, 32%, and 22% (P = .007) and 43%, 28%, 29%, and 16% (P = .008) for patients >65 years of age. For patients in remission before transplantation, 5-year PFSs were 52%, 41%, 44%, and 25% (P = .048).

Figure 1.

Transplant outcomes by conditioning regimen type. PFS (A), adjusted PFS (B), PFS for patients with KPS <90% (C), and GRFS for all patients (D).

No significant differences in outcomes were found between the 4 conditioning groups in patients with high-risk AML, defined as either secondary AML, induction failure, high-risk cytogenetics, or adverse ELN2017 genetic risk, suggesting that a more intense conditioning is not beneficial in this group of patients.

The survival benefit of the FM100 regimen persisted after adjustment for baseline factors, transplant characteristics, and multiple PSs in a multivariable analysis (MVA).

In the MVA for PFS, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was 0.57 (P = .013) for FM100, 0.68 (P = .056) for FM140, and 0.77 (P = .137) for Bu≥20000, as compared with that of the Bu16000 group. The pairwise comparisons with adjusted PS also showed that the FM100 regimen provided a PFS benefit over other conditioning regimens, including FM140 (HR 1.2 for FM140 vs FM100; P = .038) and Bu≥20000 (HR 0.73 for FM100 vs Bu≥20000; P = .044), whereas no other differences between treatment groups were found, as summarized in Table 1. In the MVA for GRFS, adjusted HR for FM100, FM140, and Bu≥20000 was 0.53 (P = .005), 0.78 (P = .196), and 0.81 (P = .178), respectively, when compared with that of the Bu16000 group.

Table 1.

Estimated pairwise treatment effects on PFS between the 4 conditioning regimen groups after correction of the multiple PSs and other baseline and transplant characteristics

| Conditioning type | Reference: Bu16000 | Reference: Bu≥20000 | Reference: FM100 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P* | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P* | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | P* | |

| Bu≥20000 | 0.77 (0.55-1.09) | .137 | Reference | — | — | — |

| FM100 | 0.57 (0.36-0.89) | .013 | 0.73 (0.46-0.98) | .044 | Reference | — |

| FM140 | 0.68 (0.45-1.01) | .056 | 0.87 (0.57-1.34) | .554 | 1.20 (1.03-1.42) | .038 |

CI, confidence interval.

Variables included in the multivariable Cox regression model were propensity score, age (>65 vs ≤65 y), KPS >90 vs ≤90), secondary AML, ELN2017 genetic risk, remission status before transplant, induction failure, donor type, stem cell source, patient and donor cytomegalovirus serostatus, and transplant protocol (on protocol vs standard of care).

AHCT for elderly AML patients is more challenging,3 as the procedure-related mortality usually increases with age. The use of RIC regimens can allow older and debilitated patients to safely undergo AHCT. To date, it remains unclear whether some patients can benefit from a MAC or whether there are differences among different RIC conditioning regimens for older AML patients. A prospective study of elderly AML patients undergoing AHCT with a RIC of fludarabine and low-dose busulfan showed that nearly half of the patients experienced a disease relapse.5 Similar results were found in the current study, with 55% of patients who received the Bu16000 regimen relapsing within 3 years. With the use of the RIC FM140 regimen, better disease control can be achieved, with several retrospective studies reporting significantly lower risk of relapse compared with the FB regimen; yet, overall survival remained similar, mainly because the relapse benefit was offset by an increase in NRM.14-16

To further reduce toxicity and make the regimen more tolerable, especially in older patients, FM100 has been studied. Our group previously reported encouraging long-term outcomes and low treatment-related mortality when the FM100 regimen was used in younger patients receiving HLA-matched and alternative donor transplants.17,18 However, it remains unclear how well this regimen performs in older AML patients compared with other conditioning regimens used in this age group.

In the current study, we demonstrated that lower melphalan doses significantly improved NRM without an increase in relapse rate when compared with another RIC (Bu16000 AUC, FM140) or the more myeloablative busulfan-based conditioning regimen (Bu20000 AUC). The beneficial effect of FM100 was mainly attributable to patients with low- to intermediate-risk disease, whereas, interestingly, patients with higher risk disease did not benefit more by using a more intense conditioning regimen. Moreover, to further confirm the excellent tolerability of the FM100 regimen, we found that this RIC regimen was associated with much better survival in the subgroup of patients older than 65 years or those with lower performance status.

This retrospective observational study has limitations associated with such analyses. However, these results not only are very compelling, but also are surprising. Patients receiving the FM100 conditioning regimen had better survival despite the use of the treatment preferentially in patients who could not tolerate more intense conditioning. In addition, these results were confirmed in a pairwise comparison analysis. Even though, there were some imbalances in baseline characteristics between groups, we used multiple PSAs to help eliminate selection bias in these comparisons and allow a sensible estimation of the true impact of the commonly used RIC regimens on transplantation outcomes of elderly AML patients.

In summary, our results, representing a single-center experience, suggest that a RIC regimen with fludarabine 160 mg/m2 and lower doses of melphalan (100 mg/m2) is associated with better outcomes in older patients with AML who undergo allogeneic stem cell transplantation, whereas the more intense MAC does not appear to be beneficial in this age group. Prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Footnotes

Presented in abstract form at the 61st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, Orlando, FL, 7-10 December 2019.

For original data, please send an e-mail to the corresponding author.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: S.O.C. designed the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; P.K. conducted the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; A.V., G.R., and J.C. collected the data; S.S., Q.B., A.A., R.M., B.O., U.P., C.H., A.O., N.D., and M.K. cared for the patients; R.E.C. designed the study and analyzed the data; and all authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stefan O. Ciurea, Department of Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 423, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: sciurea@mdanderson.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giralt S, Thall PF, Khouri I, et al. Melphalan and purine analog-containing preparative regimens: reduced-intensity conditioning for patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing allogeneic progenitor cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;97(3):631-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91(3):756-763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciurea SO, Rodrigues M, Giralt S, de Lima M. Aging, acute myelogenous leukemia, and allogeneic transplantation: do they belong in the same sentence? Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(4):289-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClune BL, Weisdorf DJ, Pedersen TL, et al. Effect of age on outcome of reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission or with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1878-1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devine SM, Owzar K, Blum W, et al. Phase II Study of Allogeneic Transplantation for Older Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia in First Complete Remission Using a Reduced-Intensity Conditioning Regimen: Results From Cancer and Leukemia Group B 100103 (Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology)/Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trial Network 0502. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(35):4167-4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YB, Coughlin E, Kennedy KF, et al. Busulfan dose intensity and outcomes in reduced-intensity allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(6):981-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devillier R, Crocchiolo R, Castagna L, et al. The increase from 2.5 to 5 mg/kg of rabbit anti-thymocyte-globulin dose in reduced intensity conditioning reduces acute and chronic GVHD for patients with myeloid malignancies undergoing allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(5):639-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: replacing high-dose cytotoxic therapy with graft-versus-tumor effects. Blood. 2001;97(11):3390-3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niederwieser D, Maris M, Shizuru JA, et al. Low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) and fludarabine followed by hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors and postgrafting immunosuppression with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can induce durable complete chimerism and sustained remissions in patients with hematological diseases. Blood. 2003;101(4):1620-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warlick ED, DeFor TE, Bejanyan N, et al. Reduced-Intensity Conditioning Followed by Related and Unrelated Allografts for Hematologic Malignancies: Expanded Analysis and Long-Term Follow-Up. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(1):56-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lima M, Anagnostopoulos A, Munsell M, et al. Nonablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning regimens in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: dose is relevant for long-term disease control after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104(3):865-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al Malki MM, Nathwani N, Yang D, et al. Melphalan-Based Reduced-Intensity Conditioning is Associated with Favorable Disease Control and Acceptable Toxicities in Patients Older Than 70 with Hematologic Malignancies Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(9):1828-1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129(4):424-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baron F, Labopin M, Peniket A, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning with fludarabine and busulfan versus fludarabine and melphalan for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121(7):1048-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damlaj M, Alkhateeb HB, Hefazi M, et al. Fludarabine-Busulfan Reduced-Intensity Conditioning in Comparison with Fludarabine-Melphalan Is Associated with Increased Relapse Risk In Spite of Pharmacokinetic Dosing. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(8):1431-1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamura K, Kako S, Mizuta S, et al. Comparison of Conditioning with Fludarabine/Busulfan and Fludarabine/Melphalan in Allogeneic Transplantation Recipients 50 Years or Older. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(12):2079-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popat U, de Lima MJ, Saliba RM, et al. Long-term outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic SCT in patients with AML in CR. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(2):212-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaballa S, Ge I, El Fakih R, et al. Results of a 2-arm, phase 2 clinical trial using post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for the prevention of graft-versus-host disease in haploidentical donor and mismatched unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2016;122(21):3316-3326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.