Abstract

Background:

Most patients who undergo bariatric surgery experience significant weight loss and improvements in obesity-related comorbidities in the first 6-18 months after surgery. However, 20-30% of patients experience suboptimal weight loss or significant weight regain within the first few postoperative years. Psychosocial functioning may contribute to suboptimal weight losses and/or postoperative psychosocial distress.

Setting:

Two university hospitals.

Objective:

Assess psychosocial functioning, eating behavior, and impulsivity in patients seeking bariatric surgery.

Methods:

Validated interviews and questionnaires. Impulsivity assessed via computer program.

Results:

The present study included a larger (n = 300) and more racially diverse (70% non-white) sample than previous studies of these relationships. Forty-eight percent of participants had a current psychiatric diagnosis and 78% had at least one lifetime diagnosis. Anxiety disorders were the most common current diagnosis (25%); major depressive disorder was the most common lifetime diagnosis (44%). Approximately 6% of participants had a current alcohol or substance use disorder; 7% had a positive drug screen before surgery. A current psychiatric diagnosis was associated with greater symptoms of food addiction and night eating. Current diagnosis of alcohol use disorder or a lifetime diagnosis of anxiety disorders were associated with higher delay discounting.

Conclusions:

The study identified high rates of psychopathology and related symptoms among a large, diverse sample of bariatric surgery candidates. Psychopathology was associated with symptoms of disordered eating and higher rates of delay discounting, suggesting impulse control issues.

Keywords: Psychopathology, disordered eating, impulsivity, bariatric surgery

Introduction

Patients who undergo bariatric surgery typically reach a maximum weight loss of 20-35% of their body weight 12 months postoperatively.(1-2) These weight losses are associated with significant improvements in obesity-related co-morbidities and decreased risk of mortality.(1-2) Despite these impressive results, approximately 25% of patients fail to reach or maintain the expected postoperative weight loss.(3) Weight regain is associated with deterioration of many of the health benefits seen with substantial weight loss.(4)

Weight regain after bariatric surgery is frequently attributed to preoperative psychosocial and behavioral factors as well as physiological adaptation.(5) More specifically, there has been a great deal of interest in the presence of mental health concerns of patients who present for surgery. For these reasons, and others, many third party payers and bariatric surgery programs require that patients undergo a mental health evaluation prior to surgery.(5) These evaluations typically rely on a clinical interview of patients which are used to make a recommendation to the surgeon about a patient’s behavioral appropriateness for surgery. While this approach is useful in clinical practice for several reasons, it is considered substandard for research purposes because of the potential of clinical bias.

At least six studies have described rates of psychopathology in candidates for bariatric surgery using structured diagnostic interviews, considered the ‘gold standard’ method to assess psychopathology.(6-11) Lifetime rates of any psychiatric diagnoses ranged from 36.8%-72.6%. Mood disorders were the most frequent diagnoses, reported in 22.0%-54.8% of patients. Substance use disorders (SUDs) were found in up to 35.7% of patients and alcohol abuse or dependence in up to 33.2%. Binge eating disorder (BED) has been diagnosed in 4.6% to 27.1% of patients. Current diagnoses (as compared with lifetime) were less common, reported in 20.9%-55.5%. Mood disorders were diagnosed in up to 31.5%. BED ranged from 3.4%-41.9%. Current substance use was observed in less than 2% of patients.(6-11) Further, pathological eating behaviors have been shown to be present in candidates for bariatric surgery. Night eating has been diagnosed in 9% to 55% of patients (12) and addictive-like eating behaviors have been observed in up to 25%. (13-14) Few studies have examined the relationship between these forms of disorder eating with other forms of psychopathology.(14)

While these studies have informed both research and clinical care, they are not without limitations. Several had relatively small sample sizes. Even in studies of larger sample sizes, there has been a lack of racial or ethnic diversity among those studied. Finally, not all have used structured interviews or interviews outside of the pre-bariatric psychological evaluation included in the surgery process.

Studies focusing on the relationship between specific diagnoses and postoperative outcomes may fail to account for psychological constructs that may be shared across individual diagnoses. Mood disorders, BED, and SUDs all share the common psychological construct of impulsivity, considered an important aspect of executive functioning. A lack of impulse control may contribute to the excessive weight gain seen in people with extreme obesity and may impact the results of bariatric surgery.(15) A recent review by Yeo and colleagues concluded that impulsivity may negatively affect weight loss after bariatric surgery.(16) However, this relationship may vary based on whether impulsivity was measured via a questionnaire (i.e., impulsive personality traits) or behavioral task (i.e., impulsive choice or action) was assessed.(16)

The present study was designed to investigate the current and lifetime psychiatric history of a large, diverse sample of candidates for bariatric surgery. In addition to investigating psychiatric diagnoses through structured diagnostic interviews, symptoms of relevant psychological constructs such as eating behavior were assessed via validated questionnaire. Impulsivity was assessed via computer assessment and the relationship of these constructs to psychopathology was explored. Finally, the relationships between psychopathology, pathological eating behaviors, and impulsivity were examined given the lack of previous studies of these relationships. Results of the baseline assessment of the study sample is presented here; the sample is currently being followed through the first few postoperative years.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 260 women (87%) and 40 men (13%), 40.05 ± 11.03 years of age, with a BMI = 45.87 ± 6.24 kg/m2 who were candidates for bariatric surgery at University of Pennsylvania Health System or Temple University Hospital. Sixty-two percent were African American, 30% White, 4% more than one race, and 2% of other ethnicities. Forty-two percent were married and 42% were single. Almost two thirds (62%) reported full time employment.

Recruitment

Individuals interested in bariatric surgery at both institutions initially attended an information session at which they were provided an overview of the program and its requirements. The study was advertised to patients at this session via a flyer. Subsequently, during a preoperative medical weight management visit with the program, approximately 8-10 weeks before surgery, patients were approached by a member of the research team who introduced the study. If patients expressed interest in participation, the staff member conducted a brief screen to assess eligibility. If patients met the inclusion criteria, they provided written informed consent to participate. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania. This project was registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02775071).

Exclusion criteria were based largely on the clinical criteria used for bariatric surgery, including: uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 160 or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 100mmHg); hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 11%; recent history of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction or stroke within the past 6 months); clinically significant hepatic or renal disease; long-term treatment with oral steroids; current use of weight loss medication; and history of bariatric surgery. Non-ambulatory individuals were excluded. Smokers were not excluded.

As recommended by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and required by third party payers in the region, patients underwent a psychosocial evaluation which evaluated their psychological appropriateness for surgery. This clinical evaluation was separate from the research assessments detailed below. Patients with severe, uncontrolled psychopathology (i.e., schizophrenia, active substance abuse) identified during the routine clinical evaluation and considered to be a contraindication for surgery as well as those who reported a history of a psychiatric hospitalization in the past 6 months, were excluded.

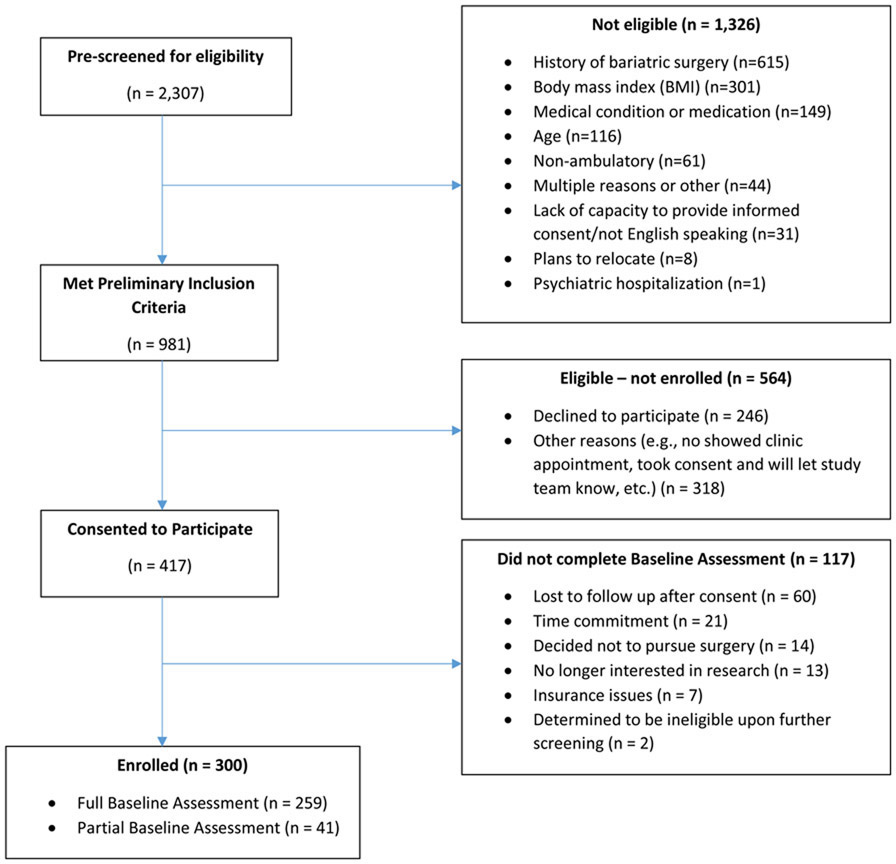

Recruitment occurred from February 2016 through November 2018. During that period, 2,307 individuals were pre-screened and 981 met the preliminary inclusion criteria for the study. Four hundred seventeen individuals were consented. Of those, 300 participants completed a full or partial baseline assessment. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and enrollment of participants into study.

Measures

Participants who completed a full baseline assessment completed the following interviews and instruments approximately 4 weeks prior to surgery.

The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5, Research Version (SCID-5-RV)(17) is a semi-structured interview for making Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnoses for mood, anxiety, eating/feeding, substance use, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), trauma, sleep-wake, externalizing and psychotic disorders. The five assessors on this study underwent approximately 16 hours of training in the administration and interpretation of the results of the interview. If an assessor had difficulty establishing a diagnosis, the case was reviewed with the other assessors as well as two licensed clinical psychologists, to finalize the diagnosis.

Symptoms of psychopathology also were assessed by self-report. Symptoms of depression were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).(18) Eating behavior was assessed with two measures. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ)(19) is a 14-item scale that measures symptoms of night eating. The Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS)(20) is a 25-item mixed response scale that is used to identify those who report consuming high sugar/high fat foods and experiencing symptoms that are similar to markers of substance use. Urine drug screens were collected to assess for common drugs of abuse.

Relevant domains of impulsivity were assessed via study laptops programmed with E-Prime® (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.). The Stop Signal Task (SST)(21) is a measure of the ability to inhibit an ongoing or prepotent response (i.e., response inhibition or impulsive action).(22-23) Participants are instructed to respond to left and right-facing arrows (go signal) on the computer screen as quickly as possible by pressing keys on the left and right hand side of the keyboard. On 25% of trials, a stop signal (an 800 hertz, 100 millisecond (ms), 70 decibel (dB) tone) is presented indicating that the participant should inhibit a response. The initial stop delay in each block is 250ms after the go signal and adjusts ± 50ms depending on whether the participant successfully avoids responding to the go signal by pressing a key on the keyboard (i.e., inhibits).(21) Participants complete three 64-trial task blocks. Trials consist of a 500-ms warning stimulus, a 1,000-ms go signal, and 1,000-ms blank screen inter-trial interval. The primary outcome is stop signal reaction time (SSRT), calculated as the mean reaction time (RT) on go-trials (MRT) minus mean stop delay (MSD). Slower SSRT indicates difficulty withholding responses, i.e., poorer response inhibition or more impulsive action. At least one previous study has found that the task is predictive of weight loss following bariatric surgery.(24)

The Stroop Test is a measure of interference control or the ability to suppress habitual responses.(25) Participants view a series of words on a computer monitor and are asked to press the key associated with the color of the word rather than the word itself. Congruent trials are trials in which the word and color match (e.g., the word “green” appears in the color green). Incongruent trials are trials in which the words are printed in colors that do not match the colors of the words. Correct responses and RT for congruent and incongruent trials are recorded. The primary outcome is the interference score, which is calculated as RT (incongruent) minus RT (congruent), with larger interference scores reflecting less interference control. Higher interference scores have been found among those with obesity as compared to those of average weight.(26)

The Delay Discounting Task (DDT) is a measure of impulsive choice in which participants chose between a smaller reward available immediately and a larger reward available after a delay (e.g., $20 today versus $40 in a month). As in previous work, the immediate reward was fixed and the magnitude and delay of the larger, later reward varied from trial to trial. Participants made 51 choices. The primary outcome was the subject’s discount rate, estimated by fitting a logistic regression that assumes a person’s decisions are a stochastic function of the difference in subjective value between the two options.(27) The subjective value (SV) is assumed to be a hyperbolic function of the reward amount (A) and delay (D): SV = A/(1+kD), where k is the participant’s discount rate. Larger values of k indicate a preference for smaller, more immediate rewards and therefore a greater degree of discounting of future rewards (i.e., more impulsive choice). Persons with obesity, compared to those of average weight, have demonstrated greater discounting rates.(28)

Results

Psychopathology

Table 1 presents the percentage of patients diagnosed with current or lifetime psychopathology. There were no differences in rates of current and lifetime history of psychopathology by race or ethnicity. (Of note, race was grouped by African-American; White; American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, or Other. Ethnicity was group by Hispanic or Latino or Not Hispanic or Latino. Non-responses were treated as missing.)

Table 1.

Current and Lifetime Psychiatric Diagnoses Assessed Prior to Bariatric Surgery

| n (%) or mean ± Standard Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Current | Lifetime | |

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 128 (47.76) | 210 (78.07) |

| Number of psychiatric diagnoses | 0.94 ± 1.33 | 2.23 ± 2.10 |

| 0 Psychiatric Diagnoses | 140 (52.24) | 58 (21.64) |

| 1 Psychiatric Diagnosis | 61 (22.76) | 67 (25.00) |

| 2 Psychiatric Diagnoses | 36 (13.43) | 47 (17.54) |

| 3+ Psychiatric Diagnoses | 31 (11.57) | 96 (35.82) |

| Any Bipolar and Related Disorder or Depressive Disorders | 19 (7.09) | 130 (48.69) |

| Bipolar I Disorder | 4 (1.49) | 6 (2.24) |

| Bipolar II Disorder | 2 (0.75) | 4 (1.49) |

| Depressive Disorders | ||

| Major Depressive Disorder | 7 (2.61) | 119 (44.40) |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder | 9 (3.36) | 23 (8.58) |

| Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder* | 23 (8.58) | 23 (8.58) |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 68 (25.37) | 88 (32.84) |

| Panic Disorder | 7 (2.61) | 22 (8.21) |

| Agoraphobia | 10 (3.73) | 12 (4.48) |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 19 (7.09) | 22 (8.21) |

| Specific Phobia | 41 (15.30) | 47 (17.54) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 12 (4.48) | 22 (8.21) |

| Other Specified Anxiety Disorder | 1 (0.37) | 2 (0.75) |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 7 (2.61) | 66 (24.63) |

| Substance Use Disorders | 9 (3.36) | 50 (18.66) |

| Sedative/Hypnotic/Anxiolytics | 0 | 5 (1.87) |

| Cannabis | 7 (2.61) | 39 (14.55) |

| Stimulants | 1 (0.37) | 11 (4.10) |

| Opioids | 2 (0.75) | 5 (1.87) |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 9 (3.36) | 12 (4.48) |

| Body Dysmorphic Disorder | 3 (1.12) | 4 (1.49) |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 24 (8.96) | 58 (21.64) |

| Adjustment Disorder | 2 (0.75) | 3 (1.12) |

| Sleep-Wake Disorders* | ||

| Insomnia | 26 (9.70) | 26 (9.70) |

| Hypersomnia | 4 (1.49) | 4 (1.49) |

| Substance/Medication Induced Sleep Disorder | 1 (0.37) | 1 (0.37) |

| Feeding and Eating Disorders | ||

| Bulimia Nervosa | 2 (0.75) | 6 (2.24) |

| Binge Eating Disorder | 16 (5.97) | 27 (10.07) |

| Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder* | 15 (5.60) | 15 (5.60) |

Note: Excluded from this table are those disorders where there were no participants meeting either lifetime or current diagnostic criteria. This includes (cyclothymia, other specified disorders, disorders due to another medical condition and substance/medication induced disorders across all diagnostic categories except anxiety).

Also excluded from this table are those disorders where no participants met diagnostic criteria for a current diagnosis and fewer than 3 met criteria for a lifetime disorder. This includes: depressive disorder due to another medical condition (AMC), schizophrenia, anxiety disorder due to AMC, other hallucinogens, other/unknown substances, other trauma disorder, other specified feeding or eating disorder.

The lifetime occurrence of these disorders is not assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Research Version (SCID-5-RV). Patients are only asked to report whether for symptoms of these during the current diagnostic timeframe. To remain consistent, these are included in both the current and lifetime diagnostic columns.

Approximately 48% of patients received at least one current psychiatric diagnosis and 78% received at least one lifetime diagnosis. Anxiety disorders were the most common current diagnosis seen in 25% of participants. Mood disorders (including bipolar and related disorders or depressive disorders) were diagnosed in 7%. Lifetime diagnoses of anxiety and mood disorders were observed in 33% and 44% of patients, respectively. Nine percent of individuals met diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); 22% had a lifetime history of PTSD.

Approximately 6% of patients were found to have a current alcohol use disorder (AUD) or substance use disorder (SUD) based on the SCID-5-RV. Nineteen (7%) had a positive urine drug screen. Fifteen (5%) tested positive for marijuana, 2 tested positive for multiple substances (0.7%) (marijuana and opiates and marijuana and amphetamines), 1 (0.3%) tested positive for amphetamines, and 1 tested positive for cocaine (0.3%). In all cases of positive results for opiates and amphetamines, participants were prescribed medications that may have led to the positive result (e.g., methylphenidate and oxycodone). Approximately 25% of patients were found to meet diagnostic criteria for a lifetime AUD and 19% met criteria for a lifetime SUD. Sixteen patients (6%) met current criteria for BED and 2 (0.8%) met criteria for bulimia nervosa (BN). Twenty-seven patients (10%) met lifetime criteria for BED and 6 (2%) for BN.

As assessed by the YFAS, 21 individuals (7%) met criteria for food addiction. Based on the NEQ, 19 (6.53%) patients met the cut-score of 25, suggestive of the night eating syndrome. The mean score on the BDI-II was 7.79 ± 6.98, suggesting minimal symptoms of depression. Two hundred and fifty six participants (85%) endorsed minimal symptoms of depression. Twenty-four patients (8%) had scores indicating mild symptoms of depression (14 to 19), 14 patients (5%) endorsed moderate symptoms (20 to 28) and 6 (2%) severe symptoms (> 29).

Table 2 presents the results for the three impulsivity tasks. For the Stroop task, accuracy was higher for congruent trials compared to incongruent trials and reaction time during incongruent trials (849.89 ± 198.82 ms) was longer compared to congruent trials (724.88 ± 137.75 ms) (p-values <0.001 using one-sample signed rank test). Performance on the SST and DDT were not considered to be reflective of symptoms of psychopathology.(21,29-30)

Table 2.

Results for the Executive Functioning Tasks

| mean ± Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|

| Stroop Task | |

| Congruent Trials (# Correct out of 48) | 46.97 ± 1.78 |

| Incongruent Trials (# Correct out of 48) | 43.82 ± 5.82 |

| Reaction Time (ms): Incongruent - Congruent (Median) | 125.01 ± 111.37 |

| Stop Signal Task | |

| Go Reaction Time (ms) | 549.12 ± 112.93 |

| Stop Signal Reaction Time (ms) | 245.69 ± 42.30 |

| Delay Discounting Task | |

| Log Discount Rate | −4.16 ± 1.12 |

| Discount Rate | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

ms = millisecond

Table 3 shows the correlations between the major variables of interest. The number of current and lifetime diagnoses were significantly associated with greater symptoms of depression, food addiction, and night eating. Night eating was also positively correlated with BDI total score and YFAS symptom count. Total number of current and lifetime diagnoses were not associated with any of the measures of impulsivity.

Table 3.

Correlations between Measures of Psychopathology, Eating Behavior and Impulsivity (Spearman Correlation Coefficients)

| Body Mass Index |

Number of Current Diagnoses (SCID-5- RV)+ |

Number of Lifetime Diagnoses (SCID-5- RV)+ |

Beck Depression Inventory- II Total Score |

Yale Food Addiction Scale Symptom Count |

Night Eating Questionnaire |

Stroop Task |

Stop Signal Task |

Delay Discounting |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Mass Index | 1 | ||||||||

| Number of Current Diagnoses (SCID-5-RV)+ | −0.01 | 1 | |||||||

| Number of Lifetime Diagnoses (SCID-5-RV)+ | 0.04 | 0.72*** | 1 | ||||||

| Beck Depression Inventory-II Total Score | 0.06 | 0.33*** | 0.28*** | 1 | |||||

| Yale Food Addiction Scale Symptom Count | −0.01 | 0.29*** | 0.26*** | 0.34*** | 1 | ||||

| Night Eating Questionnaire | −0.10 | 0.32*** | 0.31*** | 0.34*** | 0.26*** | 1 | |||

| Stroop Task | −0.04 | 0.005 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 1 | ||

| Stop Signal Task | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.14* | 1 | |

| Delay Discounting | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 1 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p< 0.001

SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Diagnosis, Research Version

When comparing patients with and without specific psychiatric diagnoses (using nonparametric tests), current diagnosis of AUD and lifetime diagnosis of an anxiety disorder were associated with higher scores on the delay discounting task than those without these diagnoses (median: −2.56 vs. −4.12, p = 0.02 and median: −3.91 vs. −4.23, p= 0.02, respectively). Current mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders were not related to the measures of impulsivity. Lifetime mood and substance use disorders also were not related to any of the measures of impulsivity.

Conclusion

Results of the current study adds to the literature on the preoperative psychopathology observed in patients seeking bariatric surgery. In general, the rates of the major current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses are consistent with previous studies that have used similar structured clinical interviews.(6-11) Rates of current and lifetime history of psychopathology did not differ by race and ethnicity, as seen in at least one other investigation.(31) The presence of a current psychiatric diagnosis was associated with symptoms of other relevant conditions, including depression, food addiction, and night eating. A current alcohol use disorder and lifetime anxiety disorder diagnosis also was associated with delay discounting, providing some evidence for a desire for an immediate (smaller) reward over a larger reward after a delay in some candidates for surgery.

The results provide further evidence that a large minority of individuals with clinically severe obesity present for bariatric surgery with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. Over 75% have a psychiatric diagnosis in their history. Both percentages are larger than reported in the general population and underscore the psychosocial burden of living with extreme obesity. The size and racial diversity of the study sample are methodological strengths that increase the confidence in the generalizability of the observations.

Anxiety disorders were the most common current diagnoses and mood disorders were the most common lifetime diagnoses. While anxiety disorders are commonly observed in the bariatric population, their relevance to candidacy for bariatric surgery is unclear. Conditions such as specific phobia, diagnosed in 15% of candidates, are likely to be unrelated to appropriateness for surgery. In contrast, social anxiety disorder (diagnosed in 7% of candidates) may interfere with a patient’s ability to appropriately engage with the bariatric surgery team during the preoperative consultation and evaluation process or to utilize resources such as support groups.

The percentage of anxiety disorders observed here is lower than some, but not all, previous studies that have used structured clinical interviews. This is likely an artifact of a recent change to these assessments, in which PTSD is no longer classified as an anxiety disorder. In the present study, approximately 9% of patients had a current diagnosis of PTSD and 22% had a lifetime history. The traumatic events in these cases ranged from physical and sexual trauma, serious accidents, and jobs that exposed them to extremely upsetting things (e.g., collecting human remains, investigating child abuse).

Consistent with other studies, the rate of current SUD in candidates was low (3%). A novel observation in the current study was that 19 patients (7%) had a positive urine drug screen, suggesting that some patients engaged in ‘impression management’ in minimizing their use of illicit substances, even in a setting that was independent from the surgery evaluation. Most of these patients tested positive for marijuana. Given the changing legal status of marijuana from state to state, this observation is not particularly surprising. The field could likely benefit from a consensus statement to guide clinicians as they evaluate marijuana use in candidates for surgery.

Approximately 25% of patients had a history of AUD and 18% has a history of another SUD. King and colleagues found an increased rate of AUD in the second postoperative year as compared to the year prior to surgery or in the first postoperative year.(32) Increases in alcohol or composite substance abuse (drug, alcohol, or cigarettes) have been observed in the first two years after bariatric surgery in other studies.(33) As we follow this cohort postoperatively, we also will be able to report on changes in these diagnoses over time.

Self-reported symptoms of depression were associated with a current psychiatric diagnosis. In addition, symptoms of food addiction and night eating also were associated with the presence of a current diagnosis. While both conditions are not fully recognized diagnoses at this time, food addiction and night eating are routinely assessed prior to bariatric surgery and both have been associated with poor postoperative outcomes.(14,34) When the symptoms of food addiction and night eating are considered along with the presence of BED, the present study further confirms that disordered eating is quite common among candidates for bariatric surgery. Results also suggest that these forms of disordered eating is related to other emotional problems.

The presence of a certain psychiatric diagnoses were associated with greater delay discounting of a future reward. Association between delay discounting, psychopathology, and poor health behaviors have been found in other studies.(35) This observation suggests that individuals with a specific psychiatric diagnoses are willing to forgo a larger, long term reward in exchange for a more immediate reward. Although this relationship was not observed with the Stop Signal and Stroop tasks, these tasks may assess different elements of impulsivity (i.e., response inhibition or impulsive action and interference control, respectively). Interference control and impulsive action reflect the ability to suppress irrelevant or distracting stimuli and the ability to inhibit ongoing or automatic responses, respectively. In addition, there is a lack of consensus as to whether these measures are assessing impulsivity as a state or as a more stable trait. Tasks utilizing food-related stimuli may be more sensitive to detecting associations with these aspects of impulsivity in this population.(36) Nevertheless, it is possible that all three domains of impulsivity are associated with postoperative weight losses and psychosocial adjustment. For example, the physical aspects of bariatric surgery typically prevent individuals from eating the objectively large amount of food necessary to meet the diagnostic criteria of BED. However, many report the feeling of loss of control over their eating. The self-reported inability to control these impulses postoperatively is associated with smaller weight losses and greater emotional distress in the first few postoperative years.(37)

As noted above, the large racially diverse sample is a methodological strength of the study. No differences in psychopathology were seen across racial and ethnic groups. Nevertheless, the diversity of the sample will provide an opportunity to investigate differences in weight loss and the behavioral and psychosocial variables of interest postoperatively. The use of a structured clinical interview to establish diagnoses, joined by psychometrically sound patient reported outcome measures, is another strength. The relatively small percentage of men is a commonly seen limitation in the bariatric surgery literature. The large number of individuals who refused to participate in the study raises some concern about the generalizability of the findings. The preoperative research assessment took approximately 3 hours. While participants received an honorarium for participation, some declined participation because of the time burden. Others may have declined to participate secondary to concerns that their psychiatric status would be shared with the clinical team, despite assurances that the assessments were blinded. If that were a common reason to refuse to participate, our overall rates of psychopathology may have been higher.

While the present results provide important, confirmatory information on the psychiatric status and history of individuals who present for bariatric surgery, the most important research questions regarding the relationship between preoperative psychopathology, both with respect to specific diagnoses and in total, and postoperative weight loss and psychosocial adjustment warrant further investigation. Several studies have suggested that preoperative psychopathology is associated with suboptimal postoperative outcomes; others have failed to identify that association.(38-39) Greater understanding of the relationship can provide further evidence of the importance of the preoperative psychological evaluation as well as identify targets for postoperative mental health and behavioral interventions to enhance outcomes of patients who might be at-risk for less-than-optimal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This review article was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grant #R01DK108628 and an Administrative Supplement #R01DK108628 S1 and by the FY2015 Pennsylvania Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program Formula Funding (PA CURE).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

Author A reports grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease and the FY2015 Pennsylvania Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program Formula Funding (PA CURE) during the conduct of the study and personal fees Merz and Novo Nordisk, Inc outside the submitted work. Author B reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Inc. and WW, outside the submitted work. Author C reports grants from Novo Nordisk, Inc., outside the submitted work. Author K reports grants from National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease, during the conduct of the study. Author M reports grants from Novo Nordisk, personal fees from WW (formerly Weight Watchers, International), outside the submitted work. Authors D, E, F, G, H, I, J, and L have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1).Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, Kolotkin RL, LaMonte MJ, Pendleton RC, et al. Health benefits of gastric bypass surgery after 6 years. JAMA. 2012. 19;308(11):1122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia L, Horlick M, Kalarchian MA, King WC, Mitchell JE, Patterson EJ, Pender JR, Pomp A, Pories WJ, Thirlby RC, Yanovski SZ, Wolfe BM; Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Consortium. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013. December 11;310(22):2416–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Sarwer DB, Dilks R, West Smith L. Dietary intake and eating behavior after bariatric surgery: threats to weight loss maintenance and strategies for success. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2011;7:644–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).DiGiorgi M, Rosen DJ, Choi JJ et al. Re-emergence of diabetes after gastric bypass in patients with mid- to long-term follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Sarwer DB, Heinberg LJ. Psychosocial aspects of extreme obesity. Amer Psychol. 2020. Feb-Mar;75(2):252–264.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Jones-Corneille J, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, Faulconbridge LF, Fabricatore AN, Stack RM, et al. Axis I psychopathology in bariatric surgery candidates with and without binge eating disorder: results of structured clinical interviews. Obes Surg 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, Courcoulas AP, Pilkonis PA, Ringham RM, et al. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: Relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Mauri M, Rucci P, Calderone A, et al. Axis I and II disorders and quality of life in bariatric surgery candidates. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69:295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Mitchell JE, Selzer F, Kalarchian MA, Devlin MJ, Strain GW, Elder KA, Marcus MD, Wonderlick S, Christian NJ, Yanovski SZ. Psychopathology before surgery in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery-3 (LABS-3) psychosocial study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2012;8:533–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Mühlhans B, Horback T, de Zwaan M. Psychiatric disorders in bariatric surgery candidates: a review of the literature and results of a German prebariatric surgery sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:414–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Rosenberger PH, Henderson KE, Grilo CM. Psychiatric disorder comorbidity and association with eating disorders in bariatric surgery patients: A cross-sectional study using structured interview-based diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1080–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).de Zwaan M, Marschollek M, Allison KC. The Night Eating Syndrome (NES) in Bariatric Surgery Patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015:23(6); 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Benzerouk F, Gierski F, Ducluzeau P-H, et al. Food addiction, in obese patients seeking bariatric surgery, is associated with higher prevalence of current mood and anxiety disorders and past mood disorders. Psychiatry Res 2018;267:473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Koball AM, Clark MM, Collazo-Clavell M, et al. The relationship among food addiction, negative mood, and eating-disordered behaviors in patients seeking to have bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(1):165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Sarwer DB, Allison KC, Wadden TA, et al. Psychopathology, disordered eating and impulsivity as predictors of outcomes of bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis, 2019;15(4):650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Yeo D, Toh A, Yeo C, et al. The impact of impulsivity on weight loss after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Eat Weight Dis. 2020. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).American Psychiatric Association. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Research Version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18).Beck AT, Steer RA. BDI Beck Depression Inventory Manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19).Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O'Reardon JP, Martino NS, Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Stunkard AJ. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the night eating syndrome. Eat Behav, 2008; 9:62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD, Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite 2009;52:430–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Logan GD. On the Ability to Inhibit Thought and Action: A User's Guide to the Stop Signal Paradigm. In: Dagenbach DaC TH, editor. Inhibitory Processes in Attention, Memory, and Language. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. p. 189–238. [Google Scholar]

- 22).Ashare RL, Hawk LW Jr. Effects of smoking abstinence on impulsive behavior among smokers high and low in ADHD-like symptoms. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;219:537–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Mole TB, Irvine MA, Worbe Y, et al. Impulsivity in disorders of food and drug misuse. Psychol Med 2015;45:771–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Kulendran M, Borovoi L, Purkayastha S, Darzi A, Vlaev I. Impulsivity predicts weight loss after obesity surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(6):1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol 1935;18:643–62. [Google Scholar]

- 26).Cohen JI, Yates KF, Duong M, Convit A Obesity, orbitofrontal structure and function are associated with food choice: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 2011. 1(2):e000175. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Wileyto EP, Audrain-McGovern J, Epstein LH, Lerman C. Using logistic regression to estimate delay-discounting functions. Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers : a journal of the Psychonomic Society, Inc 2004;36:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Lavagnino L, Arnone D, Cao B, Soares JC, Selvaraj S. Inhibitory Control in Obesity and Binge Eating Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Neurocognitive and Neuroimaging Studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;28:714–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Miglin R, Kable JW, Bowers ME, Ashare RL. Withdrawal-Related Changes in Delay Discounting Predict Short-Term Smoking Abstinence. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2017;19(6):694–702. PMCID: PMC5423100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).To C, Falcone M, Loughead J, Logue-Chamberlain E, Hamilton R, Kable J, Lerman C, Ashare RL. Got chocolate? Bilateral prefrontal cortex stimulation augments chocolate consumption. Appetite. 2018;131:28–35. PMCID: PMC6197906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Ivezaj V, Fu E, Lydecker JA, Duffy AJ, Grilo CM. Racial Comparisons of Postoperative Weight Loss and Eating-Disorder Psychopathology Among Patients Following Sleeve Gastrectomy Surgery. Obesity 2019;27(5):740–745. doi: 10.1002/oby.22446. Epub 2019 Mar 29.King WC, Chen JY, Mitchell JE, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Kalarchian MA, Steffen KJ, Engel SG, Courcoulas AP, Pories WJ, Yanovski SZ. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2012;307:2516–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Ivezaj V, Saules KK, Schuh LM. New-onset substance use disorder after gastric bypass surgery: rates and associated characteristics. Obes Surg 2014;24:1975–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Ivezaj V, Widemann AA, Grilo CM. Food addiction and bariatric surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev, 2017;18(12): 1386–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Snider SE, DeHart WB, Epstein LH, Bickel WK. Does delay discounting predict maladaptive health and financial behaviors in smokers? Health Psychol, 2019;38(1):21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Hagan KE, Alasmar A, Exum A, Chinn B, Forbush KT. A systematic review and meta-analysis of attentional bias toward food in individuals with overweight and obesity. Appetite. 2020;151:104710. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Grilo CM. The prognostic significance of regular binge eating in extremely obese gastric bypass patients: 12-month postoperative outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1928–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).de Zwaan M, Enderle J, Wagner S, Mühlhans B, Ditzen B, Gefeller O, et al. Anxiety and depression in bariatric surgery patients: a prospective, follow-up study using structured clinical interviews. J Affect Disord 2011;133:61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Chao AM, Wadden TA, Faulconbridge LF, et al. Binge-eating disorder and the outcome of bariatric surgery in a prospective, observational study: Two year results. Obesity, 2016;24(11):2327–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]