ABSTRACT

Adherence issues combined with inequitable access to healthcare may increase the risk of discontinuation of care for undocumented migrants with severe mental health illness.

An Ethiopian man with paranoid schizophrenia who relapsed several times after hospitalization was identified by a humanitarian outreach team in Brussels. The team built a relationship with him by offering him access to services including accommodation and mental health care. A treatment buddy was identified to support him adhering to his treatment and accompany him while hospitalized. Effective collaboration between Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) and the hospital led to MSF ensuring continuum of care in an outpatient service with the support of the treatment buddy for treatment adherence. The patient was empowered to adhere to medication and attend appointments after hospitalization. After 6 weeks, the man became autonomous with treatment, coming for his injections and collecting his medication every 2 weeks. There has been no relapse requiring hospitalization since.

INTRODUCTION

Difficulty in adhering to treatment is a well-known issue in people with schizophrenia [1, 2] and non-adherence increases the risk of relapses, further hospitalization and self-harm [3]. Several studies recommend identifying factors affecting adherence to antipsychotic treatments and developing tailored interventions to address them [2, 3]. Recognized interventions include enhancing environmental support and the use of long-acting antipsychotic injectables [2–4].

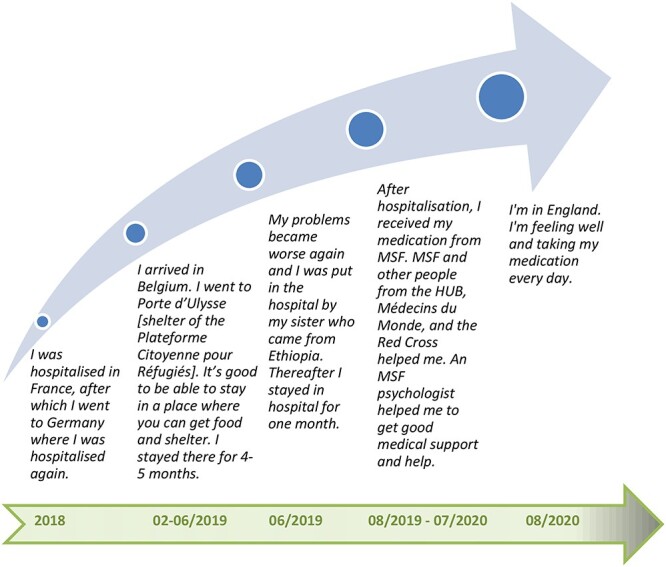

Figure 1 .

Patient perspective.

Table 1.

Clinical chart/timeline

| Date | Symptoms/diagnosis | Treatment plan and objectives |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Paranoid schizophrenia (according to patient) |

Hospitalization in France (1 month)—unknown treatment. Hospitalization in Germany (6 weeks)—unknown treatment. |

| 24/03– 23/04 2019 |

Suspicious, refuse to respond to questions, avoid visual contact, paranoid and delusional speech (hospital report received in May 2019) | 24/03–23/04: Hospitalization in Belgium. Medication: Haloperidol 5 mg, then addition of Clopixol 25 mg due to aggressive behaviour (hospital report received in May 2019) Objectives: Decrease the symptoms and increase clinical insight. |

| 26/04 2019 |

Auditory hallucinations, disorganized speech, paranoiac and suicidal thoughts (MSF) | Identification of the patient by HUB outreach team. Scarce information about treatment provided by the hospital. Medication: Risperidone 2 mg. Objective: Initiate follow-up, reduce symptoms and support the patient to remember to take his medication (dosage) |

| 17/05 2019 |

Calm and collaborating but confused Delusions of persecution Auditory hallucinations Suicidal thoughts (MSF) |

Adherence issues: The patient forgets to take his medication. He wants a ‘medication to stop the voices’. Failed hospitalization attempt (no bed available). Medication: Olanzapine 5 mg. |

| 06/ 2019 |

Continuation of symptoms (MSF) | Identification of a treatment buddy from his family. MSF supports the treatment buddy to fulfil this role. |

| 11/06–27/07 2019 |

Psychotic decompensation Auditory hallucinations Calm and collaborative Confusion Delusion of persecution Reference Suspicious (Hospital) |

Hospitalization in Brussels (1.5 month). GAF scale (on general functioning) score: 40 (on arrival). Objective: Reduce symptoms and increase psychosocial adaptation. Medication: Clopixol depot 200 mg/3 weeks, Trazodone 100 mg and Olanzapine 10 mg. GAF scale score: 55 (on discharge). Improved functioning and decreased symptoms. |

| 08/ 2019 |

Diminution of symptoms Stabilization (MSF) |

Continuum of care ensured by MSF: Clopixol depo IV 200 mg/every 2 weeks, Olanzapine 10 mg/day. The treatment buddy supports the patient. Objective: Adherence to treatment and stabilization. Autonomy with the treatment after 6 weeks: Patient comes for injections, collects and takes his daily medication. |

| 12/ 2019 |

Reappearance of auditory hallucinations and insomnia Stabilization (MSF) |

The patient is arrested and sent to a detention centre. He contacts MSF psychologist to inform about his symptoms. MSF collaborates with the detention centre to adapt the treatment: Clopixol (idem) and Olanzapine 10 mg/twice daily. |

| 01/ 2020 |

Stabilization (MSF) | The patient is back in Brussels and autonomous with treatment: Clopixol (idem) and Olanzapine 10 mg/twice daily. |

| 02/ 2020 |

Stabilization (MSF) | The patient has been arrested again. Communication between MSF and the medical service of the detention centre ensures the continuum of care (idem). |

| 03/to 06/ 2020 |

Stabilization (MSF) | MSF and Médecins du Monde (MDM) provide his medication (idem) in a hotel provided by the Plateforme Citoyenne (PFC) during Covid19 lock down in Brussels every 2 weeks. |

| 08/20 to 02/21 |

Stabilization (MDM and contacts with the patient) | The patient has reached England. MDM linked him to a general practitioner and he adheres to his medication (Olanzapine 10 mg twice daily). No hospitalization occurred. |

Adherence issues combined with a lack of equity regarding treatment opportunities for migrants in high-income countries [5] may be overcome by enhancing collaboration of non-governmental and governmental institutions in ensuring access to patient-centred mental health services for all, particularly for minorities. To optimize mental health care, the WHO recommends sharing information among the various levels of care, patients’ involvement, effective worker–patient partnerships, and community care to optimize mental health care [6].

CASE REPORT

The humanitarian Hub is an emergency support centre for migrants in Brussels run by non-governmental organizations including Médecins du Monde (MDM), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the Belgian Red Cross, the Plateforme Citoyenne de Soutien aux Réfugiés (PFC) and SOS Jeunes. They provide medical and psychological care, administrative and social advice, family tracing, phone facilities, clothing and hygienekits.

In April 2019, the Hub’s outreach activities led to the identification of a 35-year-old, undocumented migrant from Ethiopia aiming to reach the UK, who suffered from mental health issues and was sheltering in Brussels’ North station. The man accepted to follow the advice of a cultural mediator who accompanied him to see the MSF psychologist at the HUB. He had been experiencing hallucinations, paranoiac and suicidal thoughts. The man reported he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia in Ethiopia. He had been hospitalized in France and Germany in 2018 and was discharged form a hospital in Belgium 3 days before arriving at the HUB. The man showed Haloperidol (antipsychotic) oral solution received at the hospital but did not recall how many drops he was supposed to take or when to take it, nor was he aware of any follow-up appointments. The psychologist contacted the hospital where he had been recently discharged from after he expressed the wish to return, although the hospital could not ensure further hospitalization but did provide limited information at that time. The MSF psychiatrist prescribed Risperidone (atypical antipsychotic) in tablet dose and referred him to the PFC to secure accommodation for the patient.

After the patient missed his follow-up appointment 1 week later, the psychologist searched for him in the nearby area. Once located, he told her that he forgot to take his medication and wanted to be hospitalized again. Despite the intensity of symptoms, due to lack of bed space, this was not an option.

The Hub’s multidisciplinary approach favoured a productive relationship between various HUB organizations and the patient, by offering him services encompassing health care, access to shelter, clothes, phone charging and calling.

A few weeks later, a worker from the PFC shelter for women contacted MSF to inform them that a young woman from his family had arrived in Belgium and was sheltering there. The psychologist met her and the patient near the North station. She asked them if the sister could become his ‘treatment buddy’, and they agreed. This was an ad hoc intervention to support him adhering to treatment. Several days later, the sister informed MSF that he had been hospitalized and she visited him frequently at the hospital.

The MSF psychologist had built up a therapeutic relationship with the patient through informal encounters at the station and by visiting him at the hospital. She organized meetings with the patient and the hospital psychiatrist and subsequently learned of his paranoid delusional thoughts towards the hospital team. Due to the trust built between the patient and the MSF psychologist, he agreed for her to accompany him to a head scanner that he was reluctant to undergo. This created an efficient collaboration between MSF and the hospital. When the patient expressed his will to leave the hospital, even though the psychiatrist thought it was too early to discharge him, the treatment team respected his decision to leave and suggested that MSF ensures the continuum of care by providing Clopixol (antipsychotic) injections and Olanzapine (atypical antipsychotic) until the following appointment every 2 weeks at the Hub. His treatment buddy also accompanied him to his appointments and ensured that he took his daily medication.

The therapeutic alliance became institutional and a strong feeling of trust had been created between the patient, the treatment buddy and various organizations of the HUB. Organizations communicated among each other to ensure the patient needs were addressed appropriately.

After 6 weeks, the patient became fully autonomous with his treatment. Despite being hospitalized three or four times in the previous year, there has been no relapse requiring hospitalization for more than ayear.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

This case highlights how non-adherence to treatment may lead to acute reactions and further hospitalizations for people with schizophrenia [3], especially for undocumented migrants whose access to healthcare is jeopardized by a number of barriers including communication, continuity of care and confidence [5].

Even in countries guaranteeing access to healthcare for migrants, some healthcare workers feel the need to address non-governmental organizations to overcome administrative and referral barriers to provide healthcare to migrants, as seen in the continuum of care for this patient [7].

Strategies such as building trusting relationships, assisting with wider needs, connecting with other healthcare services, working in multiagency teams to deliver holistic care and flexibility in primary healthcare system have shown to be effective with undocumented migrants [8].

On the other hand, some studies suggest that enhancing flexibility and fostering patient–team relationships may create a paradox by keeping patients in a HUB whereas people should be encouraged to learn to navigate the existing healthcare system [9].

In this case, access to healthcare regardless of legal status, the integration of services, the development of a trustful relationship, patient empowerment and support through a treatment buddy system created opportunities to overcome the barriers to the continuum of mental healthcare for this undocumented migrant with paranoid schizophrenia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to the patient, his sister and to the staff of the Humanitarian Hub. We acknowledge the medical writing services of Marta A. Balinska. No funding was received from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

No ethical approval was required as the interventions implemented are part of standard care procedures.

CONSENT

The article has been shared with the patient. He has provided written informed consent before submission.

GUARANTOR

Hélène Duvivier is the guarantor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Buckley PF, Wirshing DA, Bhushan P, Pierre JM, Resnick SA, Wirshing WC. Lack of insight in schizophrenia: impact on treatment adherence. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:129–41. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Misdrahi D, Delgado A, Bouju S, Comet D, Chiariny JF. Rationale for the use of long-acting injectable risperidone: a survey of French psychiatrists. Encephale. 2013 May;39:S8–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haddad PM, Brain C, Scott J. Nonadherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: challenges and management strategies. Patient Relat Outcome Meas 2014;5:43–62. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S42735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, Scott J, Carpenter D, Ross R et al. Strategies for addressing adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness: recommendations from the expert consensus guidelines. BMC Public Health 2019;19:755. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7049-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brandenberger J, Tylleskär T, Sontag K, Peterhans B, Ritz N. A systematic literature review of reported challenges in health care delivery to migrants and refugees in high-income countries - the 3C model. BMC Public Health 2019;19:755. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7049-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO . Improving Health Systems and Services for Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, World Health Organization, 2009.

- 7. Suphanchaimat R, Kantamaturapoj K, Putthasri W, Prakongsai P. Challenges in the provision of healthcare services for migrants: a systematic review through providers’ lens. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:390. 10.1186/s12913-015-1065-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robertshaw L, Dhesi S, Jones LL. Challenges and facilitators for health professionals providing primary healthcare for refugees and asylum seekers in high-income countries: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015981. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mills ED, Burton CD, Matheson C. Engaging the citizenship of the homeless — a qualitative study of specialist primary care providers. Fam Pract 2015;32:462–7. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]