Abstract

There is mounting evidence that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) adults experience disparities across several cardiovascular risk factors compared to their heterosexual and/or cisgender peers. These disparities are posited to be driven primarily by exposure to psychosocial stressors across the lifespan. This American Heart Association scientific statement reviews the extant literature on the cardiovascular health of LGBTQ adults. Informed by the minority stress and social ecological models, the objectives of this statement were to: 1) present a conceptual model to elucidate potential mechanisms underlying cardiovascular health disparities in LGBTQ adults, 2) identify research gaps, and 3) provide suggestions for improving cardiovascular research and care of LGBTQ people. Despite the identified methodological limitations, there is evidence that LGBTQ adults (particularly lesbian, bisexual, and transgender women) experience disparities across several cardiovascular health metrics. These disparities vary by race, sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Future research in this area should incorporate longitudinal designs, elucidate physiological mechanisms, assess social and clinical determinants of cardiovascular health, and identify potential targets for behavioral interventions. There is a need to develop and test interventions that address multi-level stressors that impact the cardiovascular health of LGBTQ adults. Content on LGBTQ health should be integrated in health professions curricula and continuing education for practicing clinicians. Advancing the cardiovascular health of LGBTQ adults requires a multi-faceted approach that includes stakeholders from multiple sectors to integrate best practices into health promotion and cardiovascular care of this population.

Introduction

The approximately 11 million lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) adults in the United States (U.S.) remain a marginalized group with significant health disparities when compared to their heterosexual and/or cisgender (individuals with a gender identity that matches their sex assigned at birth) counterparts (see Table 1 for glossary of terms).1 As described in the 2011 National Academy of Medicine report on LGBTQ health, LGBTQ adults face psychosocial stressors (e.g., discrimination and bias-motivated violence) that negatively impact their health and wellbeing.2 Recognizing the need for increased research on LGBTQ populations, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established the Sexual & Gender Minority Research Office (SGMRO) in 2015 and designated LGBTQ people as a health disparity population in 2016. Despite growing attention to LGBTQ health in the past decade, knowledge gaps remain regarding the health disparities that impact this population.

Table 1.

Glossary of Terms for LGBTQ Health

| Bisexual | Someone who experiences sexual, romantic, physical, and/or spiritual attraction to people of their own gender as well as toward another gender. (sometimes shortened to “bi”) |

| Cisgender | A term used to describe people whose gender identity is congruent with what is traditionally expected based on their sex assigned at birth. |

| Gay | A term used to describe boys/men who are attracted to boys/men, but often used and embraced by people with other gender identities to describe their same-gender attractions and relationships as well. Often referred to as ‘homosexual,’ though this term is no longer used by the majority of people with same-gender attractions. |

| Gender expression | The ways in which a person communicates femininity, masculinity, androgyny, or other aspects of gender, often through speech, mannerisms, gait, or style of dress. Everyone has ways in which they express their gender. |

| Gender identity | A person’s inner sense of being a girl/woman, a boy/man, a combination of girl/woman and boy/man, something else, or having no gender at all. Everyone has a gender identity. |

| Gender minority | A broad diversity of people who experience an incongruence between their gender identity and what is traditionally expected based on their sex assigned at birth, such as transgender and gender non-binary persons. |

| Gender non-binary | A term used by some people who identify as a combination of girl/woman and boy/man, as something else, or as having no gender. Often used interchangeably with “gender non-conforming.” |

| Lesbian | Used to describe girls/women who are attracted to girls/women; applies for cisgender and transgender girls/women. Often referred to as ‘homosexual,’ though this term is no longer used by the majority of women with same-gender attractions. |

| Queer | Historically a derogatory term used against LGBTQ people, it has been embraced and reclaimed by LGBTQ communities. Queer is often used to represent all individuals who identify outside of other categories of sexual and gender identity. Queer may also be used by an individual who feels as though other sexual or gender identity labels do not adequately describe their experience. |

| Sex assigned at birth | Usually based on phenotypic presentation (i.e., genitals) of an infant and categorized as female or male; distinct from gender identity. |

| Sex | Biological sex characteristics (chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, and/or genitals); male, female, intersex. Synonymous with “sex assigned at birth.” |

| Sexual minority | A broad diversity of people who have a sexual orientation that is anything other than heterosexual/straight, and typically includes gay, bisexual, lesbian, queer, or something else. |

| Sexual orientation | A person’s physical, emotional, and romantic attachments in relation to gender. Conceptually separate from gender identity and gender expression. Everyone has a sexual orientation. |

| Straight | A boy/man or girl/woman who is attracted to people of the other binary gender than themselves; can refer to cisgender and transgender individuals. Often referred to as heterosexual. |

| Transgender man | Someone who identifies as male but was assigned female sex at birth. |

| Transgender woman | Someone who identifies as female but was assigned male sex at birth. |

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Despite declining rates of CVD mortality in the U.S., significant disparities (e.g., sex, race, and income) persist.3 There is growing evidence that LGBTQ adults experience worse cardiovascular health (CVH) relative to their heterosexual and/or cisgender peers.4,5 Yet, CVH has received limited attention relative to other health topics (e.g., HIV/AIDS and substance use) in this population. Only 4.0% of all NIH-funded studies on LGBTQ health between 1989–2011 focused on CVD and/or CVD risk factors (e.g., diet, diabetes, and obesity).6 Therefore, in 2011 the National Academy of Medicine recommended increased research on CVD in LGBTQ adults.2

The inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) measures in population-based surveys has provided nationally representative data on the CVH of LGBTQ adults in the U.S. Analyses of population-based data have found a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors among sexual minority (e.g., gay, lesbian, bisexual and other non-heterosexual persons) adults compared to their heterosexual counterparts (e.g., tobacco use,7–10 elevated body mass index [BMI],4 and diabetes8,11). Analyses of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data, the only national health survey that assesses gender identity, have documented a higher prevalence of self-reported tobacco use10 and CVD diagnoses12 in gender minority (i.e., transgender and gender diverse populations) adults relative to cisgender persons. Although LGBTQ people are often grouped together, subgroups within this population have distinct health risks and exposures; multiple studies have identified variations in CVD risk by sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual orientation, and race.12–15

To improve the CVH of LGBTQ adults, a greater understanding of existing evidence is needed. The objective of this scientific statement was to examine research on the CVH of LGBTQ adults to develop a conceptual model that elucidates potential mechanisms underlying CVH disparities in LGBTQ adults, identify research gaps, and provide suggestions for improving CVH research and care of LGBTQ people. The American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7 was used to organize findings for tobacco use, physical activity, diet, BMI, blood pressure, glycemic status, and lipids.16

Conceptual Model

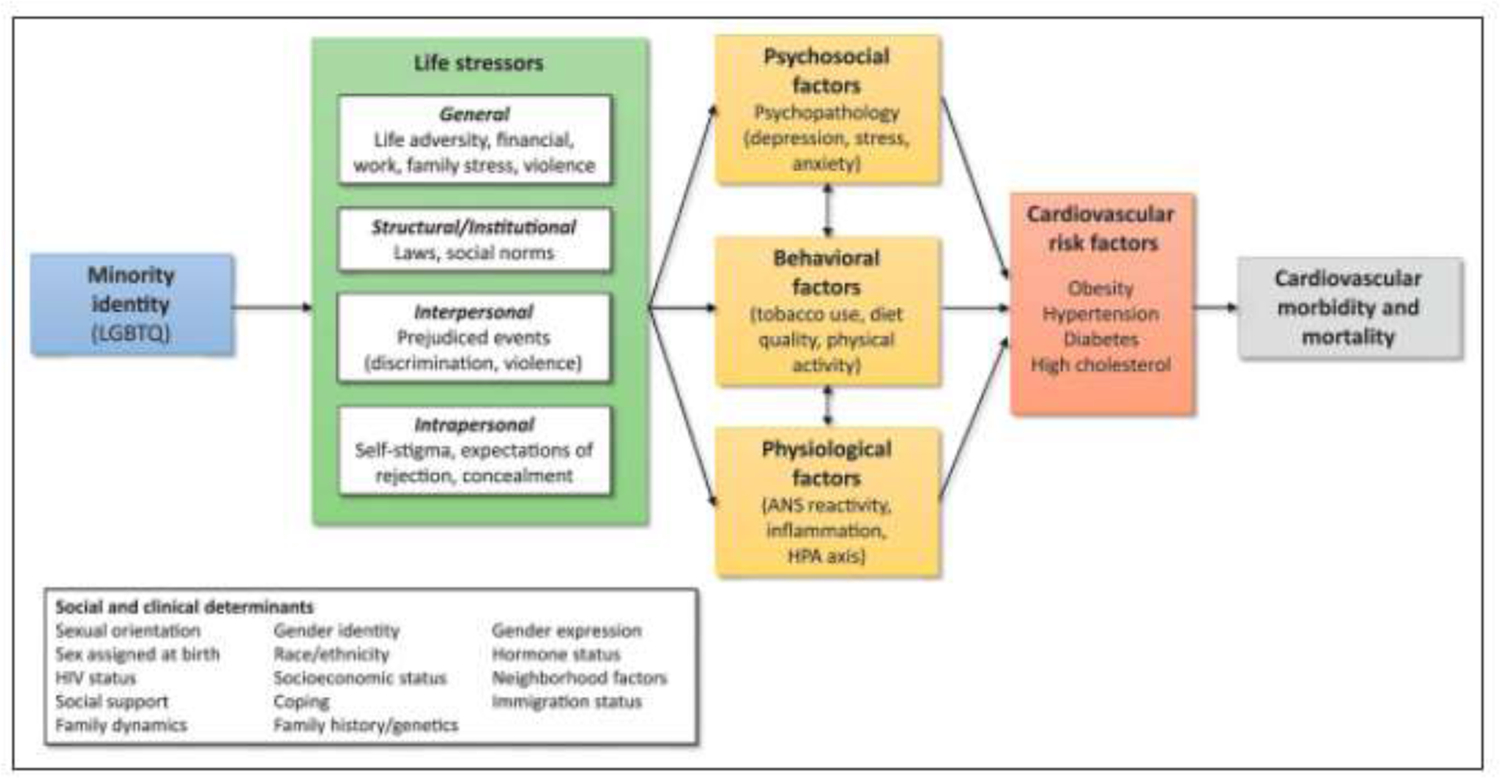

Our review of the literature was guided by the conceptual model (Figure 1) that describes potential mechanisms by which LGBTQ adults experience poor CVH. This conceptual model was informed by existing frameworks used to study LGBTQ health (i.e., the minority stress17,18 and social ecological models)19 and is intended to guide CVH research with LGBTQ adults. Exposure to stress is posited as the main driver of LGBTQ health disparities.17,18 The predominant theory to explain LGBTQ health disparities is the minority stress model, which describes how, in addition to general life stressors, LGBTQ people are exposed to multi-level minority stressors (i.e., intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural) that contribute to health disparities.17,18 Originally developed to study mental health disparities in sexual minorities, the minority stress model was later adapted for gender minority health.20 There are no existing adaptations of the minority stress model tailored for the study of CVH disparities in LGBTQ adults. In addition, the social ecological model recognizes how an individual’s health is influenced by factors in their social environment, including family, interpersonal, community, and societal factors.19

Figure.

Conceptual model of cardiovascular health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning (LGBTQ) adults.

Minority stressors.

LGBTQ adults face unique individual/intrapersonal stressors due to their SOGI (e.g., self-stigma, expectations of rejection, and concealment of SOGI).17,18 Further, LGBTQ individuals experience a high number of interpersonal stressors (i.e., discrimination, family rejection, and violence)2 that are associated with higher rates of substance use,21,22 poor mental health,22 and cardiometabolic risk across the lifespan.23,24 Despite limited evidence, structural stressors might also compromise the health of LGBTQ adults. In 2018, less than 50% of LGBTQ people lived in states that had employment and/or public accommodation (e.g., hospitals and schools) non-discrimination laws.25 There are also laws that explicitly codify discrimination, such as those preventing transgender people from using public restrooms that align with their gender identity.

Expanding mechanistic knowledge on how LGBTQ-specific minority stressors impact the CVH of LGBTQ adults is crucial to develop and tailor multi-level CVH interventions for this population. There is extensive evidence that stress exposure related to discrimination and stigma can lead to unhealthy coping behaviors and arouse psychological and physiological stress reactions that negatively impact the health of stigmatized people.26 Yet, testing of these mechanisms in LGBTQ adults has been limited.27 Research on the link between stress and CVH in other stigmatized populations (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities) can help inform CVH research with LGBTQ adults. Recent systematic reviews have documented the link between discrimination and CVH health indices (e.g., tobacco use and elevated blood pressure and weight) in stigmatized populations.27,28

General stressors.

Consistent with the minority stress and social ecological models, we hypothesize that complex interactions between LGBTQ-specific minority stressors and general life stressors across multiple levels contribute to CVH disparities in LGBTQ adults. There is mounting evidence that LGBTQ populations experience significant general stressors (e.g., life adversity and financial stress) across multiple levels that negatively influence their health across the lifespan. At the interpersonal level, LGBTQ adults are more likely than non-LGBTQ peers to report physical and sexual abuse in childhood,29 as well as a higher prevalence of interpersonal violence in adulthood.23,30 There is limited evidence of structural-level determinants of health among LGBTQ adults. However, analyses of BRFSS data from 35 states indicate that LGBTQ adults have higher rates of poverty than cisgender heterosexual people (21.6% vs. 15.7%). Poverty rates are highest among bisexual men (19.5%) and women (29.4%), transgender people (29.4%), and LGBTQ people living in rural areas.31 Within the LGBTQ population, Latinx (37.3%), Black (30.8%), and American Indian/Native Alaskan (32.4%) adults are more likely to live in poverty compared to their White peers (15.4%).31 In many circumstances, general stressors are best understood within the context of minority stress. For instance, economic disparities among LGBTQ adults might be driven by structural-level minority stressors as poverty rates are more pronounced among LGBTQ people living in Southwestern states that provide them with no legal protection against employment discrimination.31 Therefore, multi-level minority and general stressors can interact across levels to impair the health of LGBTQ adults by limiting opportunities to proper employment, housing, and access to healthcare.26

Based on existing evidence, we posit that demographic, social, and clinical factors moderate the associations of multi-level LGBTQ-specific and general stressors with CVH outcomes in LGBTQ adults (Figure 1). LGBTQ-specific minority stressors can operate synergistically with general stressors and stress related to other stigmatized identities across multiple levels to confer excess CVD risk through psychosocial, behavioral, and physiological pathways. For instance, a Black bisexual woman may experience stress related to her racial and sexual minority identity as well as being female and low-income that might be distinct from other LGBTQ adults. Thus, the potential influence of intersecting stigmatized identities on the CVH of LGBTQ adults is recognized.

Additional risk factors.

Transgender women and sexual minority men bear a disproportionate burden of HIV compared to non-LGBTQ people.32 HIV is associated with increased risk for CVD due to: a high prevalence of CVD risk behaviors among people with HIV, dyslipidemia and other cardiometabolic changes associated with certain HIV treatments, and the physiological effects of HIV disease itself.33

Moreover, the use of gender-affirming hormone therapy has been identified as a potential contributor to poor CVH in transgender people due to the potential cardiovascular effects of these treatments.5,34–36 Although studies have identified an increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) among transgender women taking estrogen,5,35 data on other CVD outcomes and their causes are limited. Evidence of elevated CVD risk in transgender men remains limited and is generally inconsistent.5,34,35

State of the Science on Cardiovascular Health in LGBTQ Adults

We use the American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7 to organize findings by CVH metrics and also summarize evidence on CVD diagnoses in LGBTQ adults. This statement does not include data on several populations that are part of the LGBTQ community (e.g., queer and questioning people) because, due to limited evidence, we could not provide a reliable report of CVH disparities in these groups. However, we use the term LGBTQ throughout this statement because the conceptual model, limitations, and suggestions for future research and clinical practice also apply to queer and questioning individuals.

Tobacco Use

LGBTQ adults are more likely to report current and lifetime tobacco use than their heterosexual and/or cisgender peers.4,7–10 Sexual minority women are more likely to use tobacco than heterosexual women and men, as well as sexual minority men.7 Despite limited evidence on tobacco use among transgender people, a recent analysis of BRFSS data found a higher prevalence of cigarette and smokeless tobacco use in transgender adults compared to their cisgender counterparts.10 Research on social determinants of tobacco use in LGBTQ populations is scarce but growing. Most notably, analyses of population-based data indicate that past-year sexual orientation discrimination is a predictor of past-year cigarette smoking in sexual minority adults.21

Physical Activity

Findings on physical activity in LGBTQ populations are mixed. A systematic review of 35 studies found that sexual minority men reported higher levels of physical activity than heterosexual men.37 The authors posited that these findings appear to be driven, in part, by social norms including a desire to conform to body ideals (i.e., thinness and muscularity) among sexual minority men, which might influence physical activity.37 Data on sexual minority women are conflicting with some studies reporting lower levels of physical activity than heterosexual women,37 whereas other studies have found higher levels.9,38 Analyses of the Nurses’ Health Study II data indicate that while sexual minority women report higher levels of aerobic physical activity, they also have higher rates of sedentary behaviors relative to heterosexual women.38 Moreover, a systematic review found that transgender adults had lower physical activity levels than their cisgender counterparts.39 A recent study found that transgender individuals taking gender-affirming hormones had greater body satisfaction, which was associated with higher physical activity.40 This suggests that gender-affirming care might play a role in promoting physical activity among transgender people.

Diet

The majority of studies have identified no differences in diet quality between LGBTQ and their heterosexual and/or cisgender peers,4 whereas some suggest differences with variable directionality.41,42 Compared to their heterosexual peers, gay men and sexual minority women report worse diet quality (e.g., lower fruit/vegetable consumption) and less favorable eating environments.41 In contrast, prospective data from the Nurses’ Health Study II indicate that between the ages 26–67 sexual minority women have better diet quality and diets lower in glycemic index than heterosexual women.42 Thus far there is limited research on diet quality in transgender people.

Body Mass Index

Most research has shown sexual minority women have a higher prevalence of subjectively and objectively measured obesity than heterosexual women.4 Racial and ethnic differences in BMI exist among sexual minority women with Black women more likely to be obese than White women.43 Gay men have a similar or lower prevalence of obesity than heterosexual men.4 Recent analyses of objective data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest bisexual men have 69% higher odds of obesity than heterosexual men.13 Data examining elevated BMI in transgender people are limited with mixed results. These studies have generally focused on changes in BMI among transgender men following initiation of gender-affirming hormone therapy.5

Blood Pressure

A systematic review of 31 studies that were published between 1985–2015 found no evidence that sexual minority adults have a higher prevalence of elevated blood pressure relative to their heterosexual counterparts.4 More recent evidence suggests that sexual minority men are more likely to have elevated blood pressure than heterosexual men.13,44 Analyses of data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) have identified higher diastolic blood pressure in gay men relative to heterosexual men.45 Bisexual men in NHANES have two times higher odds of hypertension than heterosexual men,13 and in particular, Black bisexual men have higher diastolic blood pressure than White heterosexual men.14

Overall, studies examining blood pressure in transgender adults are limited.5 Some data suggest transgender women have minimal increases in blood pressure after initiation of feminizing hormones. Similarly, testosterone use has been associated with slight increases in systolic blood pressure in transgender men.5,35 Though these changes in blood pressure were statistically significant, they had small effect sizes and are of questionable clinical significance.

Glycemic Status

Although a systematic review identified few differences in diabetes by sexual orientation,4 the included studies had methodological limitations (e.g., cross-sectional designs and reliance on self-reported data). Analyses of longitudinal data from the Nurses’ Health Study II and Add Health found that sexual minority women had a greater incidence of diabetes than heterosexual women.11,46 These differences were accentuated in younger women (24–39 years) and largely explained by elevated BMI.46 Similarly, analyses of cross-sectional NHANES data found that sexual minority women had a 56% greater prevalence of prediabetes compared to heterosexual women.8 Although most studies indicate there are few sexual orientation differences in diabetes among men,4 data from NHANES suggest that bisexual men have three times higher odds of diabetes than heterosexual men.13 Also, a recent analysis of NHANES found Black sexual minority men have higher glycosylated hemoglobin than their White heterosexual peers.14

Most studies have found few differences in diabetes between transgender and cisgender adults.5 However, two studies analyzing health record data found that transgender men and women had a higher prevalence of diabetes compared to cisgender people.47,48 Wierckx and colleagues found that transgender women were two and six times more likely to have diabetes than cisgender women and men, respectively.47

Total Cholesterol and Lipids

Studies assessing total cholesterol and lipids in LGBTQ adults, particularly objective measures, are limited.4 It appears there are no differences in total cholesterol or lipids between sexual minority and heterosexual adults.4 In transgender individuals, changes in lipid profiles have been linked to use of gender-affirming hormones. A systematic review of 29 studies found higher triglyceride levels in transgender women taking feminizing hormones, but no change in other lipids. In addition, they found that masculinizing hormone therapy for transgender men was associated with lower high-density lipoproteins and higher triglycerides and low-density lipoproteins.36 In contract, a more recent review concluded there is no convincing evidence of lipid abnormalities among transgender men.35 The significance of lipid changes on CVD outcomes (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke) in transgender people. require further investigation.

Additional Risk Factors

This statement focuses on CVH metrics included in Life’s Simple 7, however, additional risk factors, such as heavy alcohol use,16 are elevated in LGBTQ adults. Sexual minority women are more likely to report heavy drinking than heterosexual women.4,8,9,44 Transgender women and gender non-binary persons are more likely to binge drink relative to cisgender women.10 Yet, there is limited research on the cardiovascular effects of heavy drinking in LGBTQ adults.

Inadequate sleep duration and poor sleep quality have been identified as risk factors for incident hypertension, diabetes, and CVD.49 A review of 31 studies identified short sleep duration was higher among sexual minority women compared to heterosexual women. Findings for sexual minority men were mixed, and only four studies were identified that examined sleep duration in transgender people.50 Other dimensions of sleep health (e.g., sleep quality, sleep apnea, and insomnia) remain understudied in LGBTQ adults.50 The study of sleep health in LGBTQ adults is a nascent area that has important implications for understanding their CVH.

Cardiovascular Disease

Although sexual minority adults exhibit elevated risk for CVD compared to heterosexual adults, few differences in CVD diagnoses have been identified.4 There is a notable discrepancy between observed CVD risk and CVD prevalence in sexual minorities. The higher prevalence of CVD among transgender women versus cisgender adults found in the few studies that have used health records,34,51 suggests this paradox in sexual minorities might be due to a lack of appropriate measurement of CVD endpoints. Analyses of health record data indicate transgender women on gender-affirming hormones have higher incident myocardial infarction,51 VTE,51 ischemic stroke,51 and cardiovascular mortality34 than their cisgender peers. Also, analyses of data from the BRFSS have found transgender women report higher odds of CVD than cisgender people.12,52 Despite evidence of higher risk in transgender women, findings for CVH disparities among transgender men are inconsistent.5,35 Further, several reviews have concluded that evidence of higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in transgender people is limited by methodological issues, including the use of retrospective cohorts with short follow-up, cross-sectional designs, inadequate data on gender-affirming hormones, and a lack of inclusion of transgender older adults.5,34,35

Limitations of Existing Research

Testing of Mechanisms

There is a lack of understanding about mechanisms that link LGBTQ-specific stressors with CVH in LGBTQ adults, which impedes the development of interventions to promote their CVH. Despite increased risk, there is a dearth of evidence-based interventions for CVD risk reduction in LGBTQ people. Longitudinal research is needed to elucidate potential psychosocial and behavioral targets for interventions to improve the CVH of LGBTQ adults. In particular, qualitative research to understand how attitudes and beliefs within LGBTQ subgroups influence their CVH is needed prior to designing interventions. For instance, a desire to confirm to body ideals in their community may drive sexual minority men to engage in more compulsive exercising compared to heterosexual men.25 On the contrary, among sexual minority women, a greater acceptance of diverse body types and rejection of heteronormative standards of female beauty may contribute to differences in physical activity and BMI.37,53 Increasing knowledge about group-specific attitudes and beliefs regarding health behaviors is needed to enhance the acceptability of interventions designed to improve the CVH of LGBTQ adults. These interventions should account for the influence of interpersonal and structural drivers of CVH in LGBTQ adults.

Lack of Existing Data

The methodological weaknesses of the existing literature limit our understanding of causes of CVH disparities in LGBTQ adults. Most studies on CVH in LGBTQ adults analyze self-reported data from population-based surveys, which do not capture the sociocultural and clinical factors relevant to understand their CVH. There has generally been a focus on identifying differences in CVD risk factors between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ adults with little examination of the causes of CVH disparities. Further, the lack of objective measures limits the reliability of existing data. This is particularly important given that several studies have found that sexual minorities have higher odds of objectively measured hypertension and hyperglycemia relative to heterosexuals.8,11,13,14,45

To date, there are no published data on the CVH of sexual minority adults using health record data. Given evidence that LGBTQ adults experience discrimination in healthcare settings,54 electronic health records (EHRs) can be used to examine potential variations in care delivery among LGBTQ adults living with CVD. The inclusion of SOGI measures in EHRs provides an opportunity to leverage these data to examine CVH in LGBTQ individuals including healthcare utilization among those with CVD. In addition, the availability of data on social determinants (e.g., interpersonal violence, poverty, and food insecurity) in EHRs could allow researchers and clinicians to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of social factors associated with CVH in LGBTQ adults. It is important to recognize EHR data are biased towards LGBTQ adults who engage in healthcare and those who feel comfortable disclosing their SOGI to clinicians.

Data from population-based studies are based on primarily White cisgender samples of LGBTQ adults with relatively high educational attainment, limiting the ability to examine intersectional differences in CVH (e.g., by SOGI, race, and socioeconomic status). There is growing evidence that Black and Latinx LGBTQ adults, particularly sexual minority women, have higher BMI, blood pressure, and glycosylated hemoglobin than their heterosexual peers.14,15,43 There is a need to examine CVH in stigmatized groups within the LGBTQ population that may face additional structural barriers to achieving optimal CVH (e.g., people of color). Additional CVH research on subgroups within the LGBTQ community that were not included in this statement (e.g., queer and questioning persons) is critically needed.

Social and Clinical Determinants of LGBTQ Cardiovascular Health

Consistent with the minority stress and social ecological models, there is a need for research that examines multi-level social determinants of CVH in LGBTQ adults. There is evidence that sexual orientation discrimination contributes to higher odds of tobacco use in sexual minorities.21,55 The strong evidence linking discrimination with poor CVH in racial and ethnic minorities warrants further examination of discrimination as a social determinants of CVH in LGBTQ adults.27,28 Among sexual minority women interpersonal violence is associated with higher odds of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.24 Further, despite evidence of economic disparities in LGBTQ populations, only one study has assessed the influence of economic strain on the CVH of sexual minority adults (ages 24–32).56 Conducting an analysis of Add Health data, investigators found the associations of economic strain with metabolic syndrome did not differ between sexual minority and heterosexual adults. Since the prevalence of metabolic syndrome increases with age, the null findings in that study might be explained by the young age of participants.56 In addition, although findings from qualitative studies suggest that social support is associated with higher physical activity and diet quality in sexual minority adults,53,57 there is limited research examining whether resilience factors (e.g., social support and stress-related coping) can buffer the cardiovascular effects of life adversity in LGBTQ adults.

Researchers should examine the influence of multi-level social determinants of CVH in LGBTQ adults rather examining solely one level. For instance, researchers could examine the associations of discriminatory policies (e.g., anti-discrimination laws) with interpersonal discrimination (e.g., experiences of discrimination) and intrapersonal stressors (e.g., concealment of SOGI) to estimate their combined influence on CVH metrics in LGBTQ adults. This further supports the need for data sources that include SOGI and social determinants data and research that combines multiple sources (e.g., EHR data with state-level anti-discrimination policies) to examine CVH disparities in LGBTQ adults.

Research on the CVH of transgender adults is limited due to methodological weaknesses in the extant literature and should be interpreted with caution.5,34,35 There is evidence that despite their hypothesized cardiovascular effects, gender-affirming hormones might reduce psychosocial and behavioral risk factors in transgender people.40 Therefore, the potential cardiovascular effects of gender-affirming hormones should be evaluated against the benefits on their mental health and health behaviors. Also, there is limited data that examines CVH between transgender individuals taking gender-affirming hormones and those that are not. Overall, given the methodological limitations of studies on the CVH of transgender people,5,34,35 rigorous research is needed to ascertain the potential cardiovascular effects of gender-affirming hormones.

Suggestions for Research and Clinical Practice

Our suggestions for cardiovascular research and clinical practice with LGBTQ adults are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Suggestions for Research and Clinical Practice with LGBTQ Adults

| Cardiovascular Research | Clinical Practice |

|---|---|

| • Develop standardized sexual orientation and gender identity measures and integrate these in current and future NIH-funded cardiovascular prospective cohort studies to allow for data harmonization • Integrate biobehavioral measures into cardiovascular research with LGBTQ populations • Leverage electronic health record data to increase understanding of LGBTQ cardiovascular health • Partner with LGBTQ communities for measurement development, study design and conduct, and research dissemination to ensure research reflects the needs of LGBTQ adults, especially stigmatized groups • Develop and test multi-level interventions for cardiovascular risk reduction in LGBTQ adults • Examine social and clinical determinants of cardiovascular health in LGBTQ adults • Characterize the role of resilience in buffering the cardiovascular effects of stress in LGBTQ people |

• Ensure collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in electronic health records through providing clinicians with training on LGBTQ health disparities and the proper assessment of sexual orientation and gender identity in healthcare settings • Incorporate LGBTQ content in the curricula of health professions schools and post-graduate training • Require continuing education on LGBTQ health for all practicing clinicians that includes content on cardiovascular health disparities |

Research Implications

The lack of SOGI data in existing studies limits the applicability and generalizability of research on CVH in LGBTQ adults. Despite calls to include SOGI data in ongoing CVH studies, a search in April 2020 of the National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute’s Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/search/) revealed zero out of 223 studies collect SOGI data. While population-based data have provided a greater understanding of the CVH of LGBTQ people,8–12,44,45,58 they collect limited information on relevant social and clinical determinants for LGBTQ adults. Only two cardiovascular cohorts, the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (SOL) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA), have plans to collect SOGI data. Current and future NIH-funded cardiovascular cohort studies should include standardized SOGI measures that will permit data harmonization to achieve larger samples of understudied groups within the LGBTQ population.

Incorporating biobehavioral approaches into CVH research will help elucidate mechanisms by which minority stressors contribute to CVH disparities in LGBTQ adults. The proposed conceptual model is not only intended to inform future observational research, but also facilitate the development and testing of interventions that target modification of multi-level stressors.

Several steps should be taken to increase LGBTQ people’s trust of the research community. This is particularly important for stigmatized groups within the LGBTQ community (e.g., people of color and individuals with disabilities). Research teams conducting LGBTQ research should reflect the diversity that exists within the population. Researchers should also partner with LGBTQ communities during all stages of the scientific process to increase trust in research.

Clinical Implications

The ability to collect SOGI data in EHRs has been required since 2018 as part of meaningful use of EHRs, however, this policy does not require clinicians to collect this information.59 Nearly 56% of sexual minority and 70% of gender minority adults report having experienced some form of discrimination from clinicians (including use of harsh/abusive language).54 Perhaps most alarming is that approximately 8% and 25% of sexual minority and transgender individuals, respectively, have been denied healthcare by clinicians.54 It is important for practicing clinicians and health professions students to receive education on LGBTQ health and the proper assessment of SOGI in healthcare settings.

Even though several organizations provide curricular recommendations about caring for LGBTQ adults, substantial resources are needed to reduce LGBTQ health disparities. While The Joint Commission and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have comprehensive plans to improve LGBTQ health, the healthcare workforce remains unprepared to enact them. Accrediting bodies and organizations responsible for recommending curricular content, such as the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant (ARC-PA), American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), and Physician Assistant Education Association (PAEA), provide little to no requirements for LGBTQ health content in the curricula. Notably, while the AAMC provided recommendations, but not requirements, for LGBTQ health content in 2013, the ARC-PA will begin requiring LGBTQ curricular content in 2020.

Although clinicians and public health professionals need competence in providing care for LGBTQ patients, there are limited efforts to include relevant content in health professions curricula.60 With no LGBTQ-related accreditation or licensure requirements, health professions curricula (including for nurses,61 physicians,62 physician assistants,63 and public health practitioners64) have minimal content on LGBTQ health. A 2018 online survey of students at 10 medical schools found that approximately 80% of students felt not competent at treating transgender patients.65 Furthermore, a recent study of over 800 residents across 120 internal medicine residencies in the U.S. found no difference in baseline knowledge across post-graduate years (e.g., PGY-1 versus PGY-2) related to LGBTQ health topics.62 Although that study was limited to internal medicine residencies, these trends likely apply to clinicians across specialties. The knowledge of LGBTQ health and preparation of clinicians specialized in cardiology is currently unknown. The lack of LGBTQ health content in health professions curricula may limit the quality of care that LGBTQ adults receive and further exacerbate existing disparities in CVH and other health outcomes.

Conclusion

LGBTQ adults experience significant psychosocial stressors that compromise their CVH health across the lifespan. There is consistent evidence that LGBTQ adults have higher tobacco use than their heterosexual and/or cisgender peers. Sexual minority women are more likely to have elevated BMI than heterosexual women. Differences in CVH metrics between sexual minority and heterosexual adults are more pronounced in studies that have used objective measures. Among transgender women the use of gender-affirming hormones might be associated with cardiometabolic changes but the strength of existing data is limited by methodological issues. Given the lack of evidence on CVH in queer and questioning persons, this is a critical area for future work. To address knowledge gaps in the literature, longitudinal research that examines mechanisms that link social and clinical determinants with CVH in LGBTQ adults is needed. In addition, future research should employ qualitative and mixed methods to identify and develop culturally appropriate interventions for CVD risk reduction in LGBTQ adults. LGBTQ health content should be incorporated in health professions curricula and LGBTQ-related accreditation and licensure requirements are needed. There are opportunities for research, clinical, and public health efforts to better understand and reduce CVH disparities in the underserved population of LGBTQ adults.

Footnotes

Statement from Writing Group

The writing group included scholars with extensive experience conducting research on the health of LGBTQ populations with many identifying as LGBTQ themselves.

References

- 1.Newport F In U.S., estimate of LGBT population rises to 4.5%. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/234863/estimate-lgbt-population-rises.aspx. Published 2018.. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 2.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2015;132(9):873–898. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caceres BA, Brody A, Luscombe RE, et al. A systematic review of cardiovascular disease in sexual minorities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(4):e13–e21. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Streed CG, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: A narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):256–267. 10.7326/M17-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulter RWS, Kenst KS, Bowen DJ. Research funded by the National Institutes of Health on the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):105–112. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman L, Delahanty J, Johnson SE, Zhao X. Sexual and gender minority cigarette smoking disparities: An analysis of 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data. Prev Med. 2018;113:109–115. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caceres BA, Brody AA, Halkitis PN, Dorsen C, Yu G, Chyun DA. Cardiovascular disease risk in sexual minority women (18–59 years old): Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2001–2012). Women’s Health Issues. 2018;28(4):333–341. 10.1016/j.whi.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caceres BA, Makarem N, Hickey KT, Hughes TL. Cardiovascular disease disparities in sexual minority adults: An examination of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (2014–2016). Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(4):576–585. 10.1177/0890117118810246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azagba S, Latham K, Shan L. Cigarette, smokeless tobacco, and alcohol use among transgender adults in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;73:163–169. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Chen I-C, Wilkinson L, Pearson J, Zhang Y. Sexual orientation and diabetes during the transition to adulthood. LGBT Heal. 2019;6(5):227–234. 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alzahrani T, Nguyen T, Ryan A, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and myocardial infarction in the transgender population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(4):e005597. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caceres BA, Brody AA, Halkitis PN, Dorsen C, Yu G, Chyun DA. Sexual orientation differences in modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular disease diagnoses in men. LGBT Health. 2018;5(5):284–294. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caceres BA, Ancheta AJ, Dorsen C, Newlin-Lew K, Edmondson D, Hughes TL. A population-based study of the intersection of sexual identity and race/ethnicity on physiological risk factors for CVD among U.S. adults (ages 18–59). Ethn Health. March 2020:1–22. 10.1080/13557858.2020.1740174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Katz-Wise SL, Blood EA, Milliren CE, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in BMI among U.S. adolescents and young adults in three race/ethnicity groups. J Obes. 2014:537242. 10.1155/2014/537242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: The American Heart Association’s Strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks VR. Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Testa RJ, Habarth J, Peta J, Balsam K, Bockting W. Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2015;2(1):65–77. 10.1037/sgd0000081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Matthews AK, et al. Sexual orientation discrimination and tobacco use disparities in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(4):523–531. 10.1093/ntr/ntx283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein A, Golub SA. Family rejection as a predictor of suicide attempts and substance misuse among transgender and gender nonconforming adults. LGBT Health. 2016;3(3):193–199. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caceres BA, Markovic N, Edmondson D, Hughes TL. Sexual identity, adverse life experiences, and cardiovascular health in women. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(5):380–389. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caceres BA, Veldhuis CB, Hickey KT, Hughes TL. Lifetime trauma and cardiometabolic risk in sexual minority women. J Women’s Health. 2019;28(9):1200–1217. 10.1089/jwh.2018.7381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Movement Advancement Project. LGBT Policy Spotlight: Public Accommodations Nondiscrimination Laws.; 2018. http://www.lgbtmap.org/file/Spotlight-Public-Accommodations-FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 26.Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, Calabrese SK. Stigma and its implications for health: Introduction and overview. In: Major B, Dovidio JF, Link BG, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Stigma, Discrimination, and Health. 1st Editio. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2017:3–28. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190243470.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panza GA, Puhl RM, Taylor BA, Zaleski AL, Livingston J, Pescatello LS. Links between discrimination and cardiovascular health among socially stigmatized groups: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217623. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis TT, Williams DR, Tamene M, Clark CR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2014;8(1):365. 10.1007/s12170-013-0365-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(3):477–487. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown TNT, Herman JL. Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Abuse Among LGBTQ People. Los Angeles, CA; 2015. 10.1177/1524838012470034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badgett MVL, Choi SK, Wilson BDM. LGBT poverty in the United States: A study of differences between sexual orientation and gender identity groups. 2019. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/National-LGBT-Poverty-Oct-2019.pdf?utm_campaign=hsric&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and gay and bisexual men. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html. Published 2019. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 33.Feinstein MJ, Hsue PY, Benjamin LA, et al. Characteristics, prevention, and management of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019:1–27. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Defreyne J, Van de Bruaene LDL, Rietzschel E, Van Schuylenbergh J, T’Sjoen GGR. Effects of gender-affirming hormones on lipid, metabolic, and cardiac surrogate blood markers in transgender persons. Clin Chem. 2019;65(1):119–134. 10.1373/clinchem.2018.288241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connelly PJ, Marie Freel E, Perry C, et al. Gender-affirming hormone therapy, vascular health and cardiovascular disease in transgender adults. Hypertension. 2019;74(6):1266–1274. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maraka S, Singh Ospina N, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Sex steroids and cardiovascular outcomes in transgender Individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3914–3923. 10.1210/jc.2017-01643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrick SSC, Duncan LR. A systematic scoping review of engagement in physical activity among LGBTQ+ adults. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(3):226–232. 10.1123/jpah.2017-0292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.VanKim NA, Bryn AS, Hee-Jin J, Corliss HL. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women: Findings from the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Women’s Health. 2017;26(10):1077–1085. 10.1089/jwh.2017.6389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones BA, Arcelus J, Bouman WP, Haycraft E. Sport and transgender people: A systematic review of the literature relating to sport participation and competitive sport policies. Sport Med. 2017;47(4):701–716. 10.1007/s40279-016-0621-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones BA, Haycraft E, Bouman WP, Arcelus J. The levels and predictors of physical activity engagement within the treatment-seeking transgender population: A matched control study. J Phys Act Health. 2018;15(2):99–107. 10.1123/jpah.2017-0298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minnis AM, Catellier D, Kent C, et al. Differences in chronic disease behavioral indicators by sexual orientation and sex. J Public Heal Manag Pract. 2016;22(2):S25–32. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VanKim NA, Austin SB, Jun H-J, Hu FB, Corliss HL. Dietary patterns during adulthood among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women in the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;S2212–2672(16):31195–31199. 10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caceres BA, Veldhuis CB, Hughes TL. Racial/ethnic differences in cardiometabolic risk in a community sample of sexual minority women. Health Equity. 2019;3(1):350–359. 10.1089/heq.2019.0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson CL, Agénor M, Johnson DA, Austin SB, Kawachi I. Sexual orientation identity disparities in health behaviors, outcomes, and services use among men and women in the United States: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(807):1–11. 10.1186/s12889-016-3467-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Slopen N. Sexual orientation disparities in cardiovascular biomarkers among young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(6):612–621. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corliss HL, VanKim NA, Jun H-J, et al. Risk of type 2 diabetes among lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women: Findings from the Nurses’ Health Study II. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(7):1448–1454. 10.2337/dc17-2656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wierckx K, Elaut E, Declercq E, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease and cancer during cross-sex hormone therapy in a large cohort of trans persons: A case-control study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169(4):471–478. 10.1530/EJE-13-0493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dragon CN, Guerino P, Ewald E, Laffan AM. Transgender medicare beneficiaries and chronic conditions: Exploring fee-for-service claims data. LGBT Health. 2017;4(6):404–411. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.St-Onge M-P, Grandner MA, Brown D, et al. Sleep duration and quality: Impact on lifestyle behaviors and cardiometabolic health: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(18):e367–e386. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butler ES, McGlinchey E, Juster R-P. Sexual and gender minority sleep: A narrative review and suggestions for future research. J Sleep Res. 2020;29(1):e12928. 10.1111/jsr.12928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Getahun D, Nash R, Flanders WD, et al. Cross-sex hormones and acute cardiovascular events in transgender persons: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. July 2018:1–10. 10.7326/M17-2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Caceres BA, Jackman KB, Edmondson D, Bockting WO. Assessing gender identity differences in cardiovascular disease in US adults: an analysis of data from the 2014–2017 BRFSS. J Behav Med. 2020;43(2):329–338. 10.1007/s10865-019-00102-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roberts SJ, Stuart-Shor EM, Oppenheimer RA. Lesbians’ attitudes and beliefs regarding overweight and weight reduction. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(13–14):1986–1994. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lamda Legal. When Health Care Isn’t Caring Lambda Legal’s Survey on Discrimination Against LGBT People and People Living with HIV. New York, NY; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ylioja T, Cochran G, Woodford MR, Renn KA. Frequent experience of LGBQ microaggression on campus associated with smoking among sexual minority college students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(3):340–346. 10.1093/ntr/ntw305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldberg SK, Conron KJ, Halpern CT. Metabolic syndrome and economic strain among sexual minority young adults. LGBT Health. 2019;6(1):1–8. 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.VanKim NA, Porta CM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Laska MN. Lesbian, gay and bisexual college student perspectives on disparities in weight-related behaviours and body image: A qualitative analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(23–24):3676–3686. 10.1111/jocn.13106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Streed CG, McCarthy EP, Haas JS. Self-reported physical and mental health of gender nonconforming transgender adults in the United States. LGBT Health. 2018;5(7):443–448. 10.1089/lgbt.2017.0275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ONC fact sheet: 2015 edition Health Information Technology (Health IT) certification criteria, base electronic health record (EHR) definition, and ONC health IT certification program modifications final rule. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/certification-ehrs/2015-edition. Published 2015. Accessed April 12, 2020. [PubMed]

- 60.Streed CG, Davis JA. Improving clinical education and training on sexual and gender minority health. Curr Sex Heal Reports. 2018;10(4):273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim F, Johnson M, Eliason M. A national survey of faculty knowledge, experience, and readiness for teaching lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health in baccalaureate nursing programs. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2015;36:144–152. 10.5480/14-1355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Streed CG, Hedian HF, Bertram A, Sisson SD. Assessment of internal medicine resident preparedness to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):893–898. 10.1007/s11606-019-04855-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seaborne LA, Prince RJ, Kushner DM. Sexual health education in U.S. physician assistant programs. J Sex Med. 2015;12(5):1158–1164. 10.1111/jsm.12879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Talan AJ, Drake CB, Glick JL, Claiborn CS, Seal D. Sexual and gender minority health curricula and institutional support services at U.S. schools of public health. J Homosex. 2017;64(10):1350–1367. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zelin NS, Hastings C, Beaulieu-Jones BR, et al. Sexual and gender minority health in medical curricula in new England: A pilot study of medical student comfort, competence and perception of curricula. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1461513. 10.1080/10872981.2018.1461513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]