Abstract

Post-radiotherapy (RTx) bone fragility fractures are a late-onset complication occurring in bone within or underlying the radiation field. These fractures are difficult to predict, as patients do not present with local osteopenia. Using a murine hindlimb RTx model, we previously documented decreased mineralized bone strength and fracture toughness, but alterations in material properties of the organic bone matrix are largely unknown. In this study, 4 days of fractionated hindlimb irradiation (4 × 5 Gy) or Sham irradiation was administered in a mouse model (BALB/cJ, end points: 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks, n = 15/group/end point). Following demineralization, the viscoelastic stress relaxation, and monotonic tensile mechanical properties of tibiae were determined. Irradiated tibiae demonstrated an immediate (day after last radiation fraction) and sustained (4, 8, 12 weeks) increase in stress relaxation compared to the Sham group, with a 4.4% decrease in equilibrium stress (p < .017). While tensile strength was not different between groups, irradiated tibiae had a lower elastic modulus (−5%, p = .027) and energy to failure (−12.2%, p = .012) with monotonic loading. Gel electrophoresis showed that therapeutic irradiation (4 × 5 Gy) does not result in collagen fragmentation, while irradiation at a common sterilization dose (25 kGy) extensively fragmented collagen. These results suggest that altered collagen mechanical behavior has a role in postirradiation bone fragility, but this can occur without detectable collagen fragmentation. Statement of Clinical Significance: Therapeutic irradiation alters bone organic matrix mechanics and which contribute to diminished fatigue strength, but this does not occur via collagen fragmentation.

Keywords: bone biomechanics, demineralized bone, radiation therapy

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Radiation therapy (RTx) is a valuable clinical tool for management of cancers and metastatic bone pain. However, RTx is associated with increased risk for late-onset fragility fractures in bones within or underlying the irradiated tissue volume. Incidence of these fragility fractures varies by cancer type and treatment location, but may exceed 33% in some patient populations.1–8 These fragility fractures are characterized by loss of trabecular bone, an abnormal transverse fracture pattern, and little-to-no decrease in bone density.9,10 Collectively, these data indicate that postradiotherapy fragility fractures do not occur as a result of osteopenia, but rather embrittlement of the bone tissue.

Using a mouse model of unilateral hindlimb limited field radiotherapy, we have previously demonstrated that therapeutic radiation results in loss of femoral metaphyseal trabecular structures (decreased trabecular bone volume fraction, decreased trabecular number, decreased connectivity density, and increased trabecular spacing) subsequent to increased osteoclastic activity, diminished bone strength (axial compression testing of distal femur, femoral diaphyseal bending strength), and decreased femoral diaphyseal fracture toughness without loss of bone density.11–14 Work in other labs has supported these findings.15–17 Furthermore, we have shown that the bone matrix (organic and collagen phases) becomes increasingly aligned post-RTx, accompanied by an increase in trivalent:divalent collagen crosslink ratio as measured by Raman spectroscopy, with only small transient changes in pathologic crosslinks and adducts such as advanced glycation end products (AGEs).18–20 The mechanisms driving postradiotherapy loss of mechanical integrity in bone, however, remain poorly defined. In the absence of major changes in bone mineral density or content, it is most likely that post-RTx bone embrittlement (and resulting fragility fracture) occurs due to changes in the organic matrix composition, organization, and/or interaction with the mineral phase.

Data from other models of diminished bone biomechanical integrity (aging, diabetes) suggest that formation of AGEs—a pathologic nonenzymatic crosslink formed via free radical—may play a role in bone embrittlement.21–23 However, in the context of RTx, our data have not supported this hypothesis.11,19 Pendleton et al.24 similarly found that AGEs do not measurably accumulate in irradiated allograft bone until extremely high doses (≥50 Gy) are reached, while Burton et al.25 found no AGE formation at 33 kGy. Data from allograft sterilization studies indicate that collagen fragmentation induced by kGy irradiation contributes to decreased fracture toughness, loss of toughening mechanisms including ligament bridging, and overall loss of bone strength.24–29 However, others have shown that AGE crosslinks, such as those yielded by artificial ribosylation, may increase postyield properties of bone, and even compensate for some damage induced by 30 kGy radiation.30

We previously demonstrated that therapeutic radiation in vivo results in an immediate and sustained loss of resistance to crack propagation (a measure of bone embrittlement) in cortical bone.11 Our complementary biochemical data suggests that this may be due to changes in the organic phase of bone matrix (increased collagen alignment and maturity via Raman spectroscopy) rather than loss of bone mineral density. However, the ways in which these biochemical changes affect the biomechanics of bone collagen are not known. Using our hindlimb model of limited field irradiation in the mouse, we explored how irradiation changes the viscoelastic properties and mechanical strength of demineralized mouse tibiae. We hypothesized that irradiation induces an early and sustained loss of viscoelastic and monotonic strength properties of demineralized bone, and this alteration is associated with collagen fragmentation. We aim to determine if the immediate and sustained loss of resistance to crack propagation in bone could be explained by alterations in monotonic and viscoelastic properties of the organic matrix.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Animal model

The SUNY Upstate Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all methods and procedures (Protocol #362). Female BALB/cJ mice (Jackson Labs) were randomly assigned to a cage by animal facility staff blinded to cage treatment group assignments assigned by lab staff for radiation (RTx) or control (Sham) groups (n = 15 mice/group/time point, total n = 120). Mice were kept in an AAALAC-accredited facility (Public Health Service #D16-00318) in community housing (≤5 mice/cage, 22°C) on a 12 h light/dark cycle with water and pellet chow (Formulab Diet 5008; LabDiet) available ad libitum. Exclusion criteria included any mice that died or developed health conditions indicating euthanasia for humane reasons before their predetermined end point; no animals met these exclusion criteria. Mice received daily welfare observations, with cages and bedding changed every 2 weeks. All mice were 12 weeks of age at the time of the radiation or Sham treatments, and were anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine (100/10 mg/kg intraperitoneal; #501090/51004; MWI Veterinary Supply). Mice were exposed to either bilateral hindlimb irradiation (RTx group: four consecutive daily fractions of 5 Gy each) or Sham irradiation (Sham group: anesthesia with no irradiation). Radiation was administered to the hindlimbs using an orthovoltage X-ray source (1.1 Gy/min, 225 kV, 17 mA, 55 cm source-to-shelf distance, 0.5 mm Cu beam filter, 0.83 mm Cu half-value layer, MultiRad 225; Precision X-ray). The biologically equivalent dose for this radiation protocol was previously determined to be 55.7 Gy. Lead body and tail shielding (4 mm thick, Figure 1A) permitted less than 0.11Gy exposure to the shielded areas per 5 Gy hindlimb treatment.14 The Sham treatment group did not receive radiation, but was subjected to identical anesthesia, handling, and recovery procedures. Animals were anesthetized and irradiated in the same order every day to maintain a 24-h gap between radiation fractions as closely as possible. Experiment end points occurred at 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-RTx with n = 15/group/time point; at these time points mice were euthanized using CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation (mice for the Week 0 end point were euthanized 22–26 h after the last radiation exposure). Tibiae were removed intact, soft tissue was stripped, and bones were wrapped in saline saturated gauze and stored at −80°C.

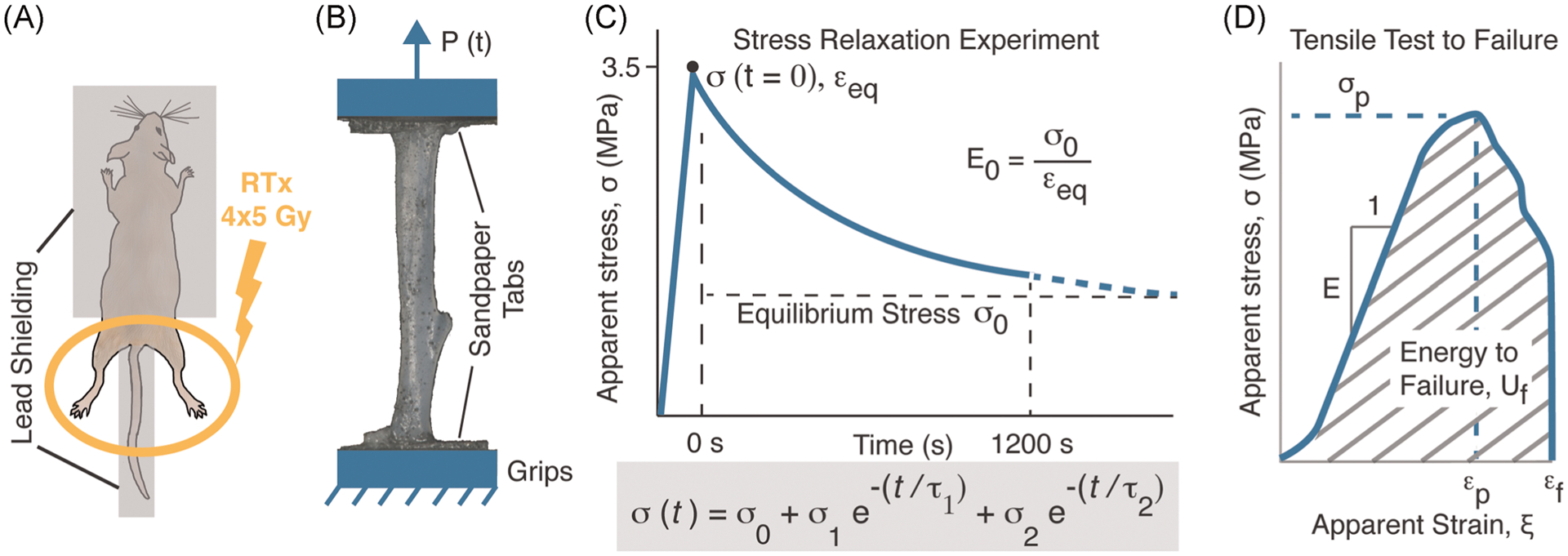

FIGURE 1.

A bilateral hindlimb murine model (A) was used to deliver four fractionated doses of 5 Gy over a 4-day period. Following demineralization, tibiae were prepared for uniaxial tensile loading (B). Mechanical loading consisted of a stress relaxation experiment (C) with a five-parameter Maxwell–Wiechert model used to characterize the stress relaxation process. This was followed by a monotonic tensile test to failure (D).

2.2 |. Mechanics of the tensile test configuration of the demineralized tibiae

Tissue level mechanical properties of demineralized bone were assessed using a tensile loading configuration of the isolated mouse tibia (Figure 1B). Before demineralization, micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scans of each tibia were obtained at 12 μm isotropic voxel resolution (55 kVp, 145 mA, 200 ms integration time, 1000 projections, binning = 1, no frame averaging, μCT 40; Scanco; Figure 2A). Bone material was identified in the micro-CT scan sets using a global lower threshold of 654 mg HA/cm3 (Gauss sigma = 1, support = 2). The cross-sectional area (CSA), as a function of axial position (Figure 2A) was determined for each tibia, and the CSA over a 1 mm length at the tibial mid-diaphysis was calculated for each tibia to represent nominal CSA. Tibiae were demineralized in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) aqueous solution (EDTA tetrasodium salt dihydrate; #0105-2.5KG; VWR) with 0.1% sodium azide (#S2002; Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C for 14 days. Decalcification was verified using X-ray imaging. Following decalcification, tibiae were again wrapped in saline saturated gauze and stored at −80°C until testing.

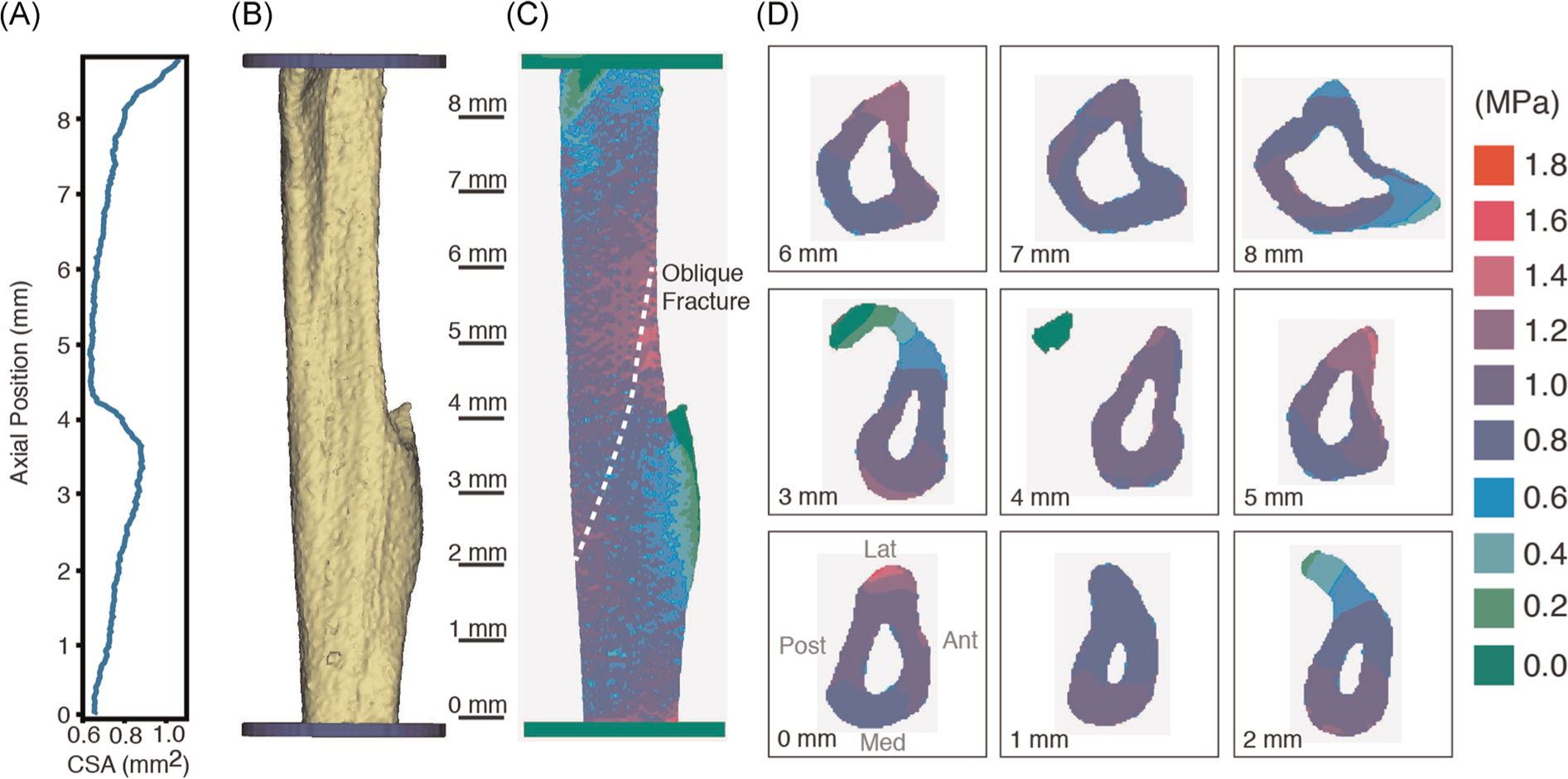

FIGURE 2.

Cross-sectional area of the mouse tibia (A) as a function of axial position determined from micro-CT scans. A solid model of the demineralized tibia (B) was created from thresholded micro-CT scans and converted to a voxel finite element mesh (C). Longitudinal stresses due to an axial tensile load are shown on the tibial surface (C) and cross-sections (D).

A linear elastic finite element (FE) model of a representative demineralized tibia was developed to characterize the linear elastic stress distribution due to tensile loading. To generate the geometry for the model, a micro-CT scan (12 μm isotropic voxel resolution at 45 kVp, 88 mA, 300 ms integration time, 1000 projections, binning = 1) was obtained for a representative demineralized tibia that was fixed in place using a custom made plastic jig, following application of a 1 N tensile preload. This preload was used to remove the natural bow in the tibia, resulting in a conformation of the tibia that matched the physical experiment. The mid-diaphyseal CSA of the representative demineralized tibia (0.62 mm2) was slightly larger than the mean CSA for all non-demineralized samples (0.591 ± 0.045 mm2). We did not specifically explore the changes in CSA with demineralization, but suspect changes to be small based on our representative demineralized tibia measurements.

A three-dimensional solid model of the demineralized tibia (Figure 2B) with idealized loading blocks was created using MIMICS (Materialise) and an isotropic, voxel-based FE mesh (Figure 2C) with 0.018 mm edge length was created (1,494,000 linear hexagonal elements, 1,638,000 nodes). Homogenous and isotropic material properties were assigned to the tibia with a 121 MPa elastic modulus (based on nominal elastic modulus from experiments below) and Poisson’s ratio of 0.21 (based on transverse to axial strain measures from same experiments). Linear elastic FE analysis was performed in MSC Marc (MSC Software Co). The distal end was fixed to prevent translation in x, y, and z directions. To obtain a nominal 1 MPa longitudinal stress, a 0.63 N axial tensile load was applied to the top of the model (nominal CSA = 0.63 mm2).

2.3 |. Stress relaxation test

To prepare demineralized tibiae for mechanical testing, proximal and distal ends of the tibia (~3 mm) were bonded to 220 grit sandpaper tabs, with the abrasive side facing out, using cyanoacrylate adhesive. The proximal and distal tabs were then clamped in loading grips of a screw-driven mechanical test frame with 45 N load cell (Qtest; MTS Corporation). Graphite powder was lightly sprayed onto the tibial surface to create texture for imaging and strain measurement. A digital imaging camera (SPOT Insight 2Mp, Diagnostic Instruments) with telecentric lens (Computar TEC-M55; CBC America), sampled at 5 Hz, was used to document deformation during the experiments. Hydration was maintained using an atomizer spray of 0.9% saline applied every 30 s for duration of all testing.

Tensile loading was performed in displacement control at 3.0 mm/min for all experiments. The nominal applied stress for each tibia was determined as the applied load divided by the CSA over the mid-diaphysis of the mineralized tibia. Before the stress relaxation test, a 10 cycle preconditioning protocol was performed between 0.05 and 2.5 MPa load limits, to align collagen fibers and achieve a repeatable mechanical response.31 The stress-relaxation sequence loading sequence included loading the tibia in tension to 3.5 MPa, holding the displacement constant at that point for 1200 s, followed by full unloading and a 1200 s hold period (Figure 1C). The viscoelastic behavior of each demineralized tibia was obtained by fitting the stress-time data with a Maxwell–Wiechert phenomenological model using JMP statistical analysis software (JMP V15).32 The five-parameter model (1) includes an asymptotic steady-state stress (σ0) reached during relaxation that is equivalent to the equilibrium stress, exponential decay with two relaxation times (τ1 and τ2), and two corresponding stress relaxation magnitudes (σ1, σ2).

| (1) |

The Maxwell–Wiechert model was found to be useful to describe the stress relaxation profiles of collagen fibrils as a function of time because collagen exhibited two distinct relaxation phases.32 The equilibrium strain (εeq) due to the 3.5 MPa applied stress was calculated as the relative displacement of the central region of the demineralized tibia, determined using points from the speckle pattern in NIH ImageJ, divided by central region gage length. The equilibrium modulus (E0), which represents the time-independent elastic modulus of the Maxwell–Wiechert model, was calculated as the applied stress (3.5 MPa) divided by equilibrium strain (εeq). Similarly, E1 and E2 were calculated as σ1 and σ2 divided by equilibrium strain (εeq), respectively.

2.4 |. Monotonic tensile test to failure

After completion of the stress relaxation test, there was a rest period of 1200 s where no loading was applied to allow recovery of the stress relaxation experiment, followed by 10 preconditioning cycles of loading as described above. Immediately after preconditioning, the tibiae were loaded to failure in tension at a rate of 3.0 mm/min. Apparent stress (σ) was calculated as the applied load divided by the central CSA, and apparent strain was calculated as the grip displacement divided by grip-to-grip distance. Strain measures using the surface graphite texture were not used for the test to failure due to very large deformations and distortion of surface, making identifying specific fiducial points difficult. Outcomes for test to failure include tensile strength (σt), elastic modulus (E) from linear portion of stress-strain curve, energy to failure (Uf) from the area below the apparent stress-strain curve, apparent strain to peak load (εp), and apparent strain to failure (εf).

2.5 |. 25 kGy irradiation as a positive control

A total of 10 mice were euthanized at 12 weeks of age. The tibiae were removed, cleaned of soft tissues, and stored at −80°C in saline-saturated gauze. The bones were then exposed to 25 kGy γ-irradiation at the Oregon State University Radiation Center using a 60Co source. Control specimens were shipped and handled concurrently, but not subjected to irradiation. Demineralized left tibiae were used for load to failure testing as described above and right tibiae were used for collagen fragmentation analysis.

2.6 |. Collagen fragmentation

Tibiae were demineralized in 10% EDTA tetrasodium salt dihydrate for 14 days at 4°C. Demineralized tibiae were rinsed for 30 min in running deionized water, then finely minced into approximately 1 mm pieces with a razor blade. The bone pieces were enzymatically digested (1 mg/ml pepsin in 0.5 M acetic acid; #P7000 and A6283; Sigma-Aldrich) for 72 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker. Insoluble collagen was removed by centrifuging the samples at 4000 rpm for 30 min at room temperature. The supernatant was transferred to a centrifugal concentration device (Millipore Amicon Ultra 15; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff filter. Samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 30 min. The concentrated sample was rinsed with 10 ml ddH2O and the centrifugation step repeated. The resulting concentrate was lyophilized, then resuspended to a concentration of 2 μg/μl in buffer (0.1 M sodium phosphate pH 7.2, 2.0 M urea, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate; #342483, #51456, and #L3771; Sigma-Aldrich) before running on a 4%–20% TRIS glycine gel (#456-1093; BioRad) and stained with GelCode Blue (#24590; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gels were imaged on a flat bed scanner (Perfection V700 Photo; Epson). Tibiae exposed to 0 Gy, 20 Gy, and 25 kGy ex vivo radiation, as well as tibiae from mice exposed to 4 × 5 Gy in vivo irradiation or Sham treatment, were analyzed.

2.7 |. Statistical analysis

The sample size for this study was guided by the previous fracture mechanics study of RTx versus Sham femurs using the same hindlimb irradiation animal model.11 In that study, a large effect size (d) of 1.04 was determined for differences in crack initiation toughness for the two groups. With a sample size of 60/treament group and significance level (α) of .05, a statistical power of greater than 0.999 was determined. Even with an effect size of one half the previous study (d = 0.52), a power of 0.80 to detect a statistically significant (α = .05) difference between groups was found. Therefore, a sample size of n = 60/treatment group was used for the current study.

To test the hypothesis that RTx induces early and sustained loss in the viscoelastic properties of demineralized bone, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used with the five parameters of the Maxwell–Wiechert model as dependent variables, treatment as a two-level independent variable (RTx or Sham), and time (weeks) as a covariate. The ANCOVA included the interaction term treatment × time, to explore if the relationship between the viscoelastic parameters and time in vivo were different (different slope), depending on treatment. A similar ANCOVA analysis was used for the monotonic strength tests with apparent tensile strength, elastic modulus, and energy to failure used as dependent variables. The percent change between RTx and Sham treatments ([{RTx-Sham}/Sham] × 100) for the dependent variables was calculated to show the magnitude of the effect of radiotherapy treatment. Normality of the residual for each regression model was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk W test. For cases where there was not a normally distributed residual, the regression model was repeated with a logarithmic transform of the dependent variable. A log transformation was performed on the two relaxation times (τ1 and τ2), and tensile strength to obtain a normal distribution of the residuals. All of the other parameters had normally distributed residuals. Homoscedasticity was verified graphically in JMP by observing the magnitude of variability of the residual as a function of time.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Body mass

Final body mass did not significantly differ between RTx and Sham groups. At 4 weeks, body mass increase from Week 0 was 8.8 ± 3.4% (mean ± SD) for the Sham group and 6.4 ± 3.9% for the RTx group. Body mass increase at 8 weeks (from Week 0) was 15.6 ± 5.3% for Sham mice and 8.9 ± 5.9% for the RTx group. Twelve-week body mass increase (from Week 0) was 26.1 ± 7.8% for the Sham group and 24.3 ± 6.9% for RTx mice. One mouse in the 8-week RTx group lost body mass (−5.2%). All other mice in the study gained body mass at 4, 8, and 12 weeks.

3.2 |. Stress distribution of demineralized tibial tensile test

The CSA of the tibia varied as a function of axial position with a global minimum occurring just proximal to the tibial-fibular junction (Figure 2A). The CSA in this region was approximately 15% smaller than the mean CSA for the mechanically loaded tibia segment (Figure 2B). The longitudinal stress (stress component aligned with the long axis of the tibia) was used to characterize the stress field in the bone as it represents the largest magnitude stress component in the tibia. As expected, when loaded with a nominal 1.0 MPa stress, there were locally higher stresses in the central region due to the smaller CSA (Figure 2C). There were also portions of the demineralized tibia that had limited longitudinal stress when loaded, including the tibial-fibular junction and proximal tibial tuberosity. These coincided with regions of maximal CSA. In terms of distribution of longitudinal stress in the tibia, 93.4% of the tibia had longitudinal stress between 0.8 and 1.2 MPa, 1.2% had stress greater than 1.2 MPa, and 5.4% had stress less than 0.8 MPa. Failure would be anticipated to initiate in the mid-section of the tibia due to the locally higher stresses. However, it should be acknowledged that this was a linear elastic FE analysis without provision for failure, and that an appropriate failure criterion for the demineralized tibia was not explored and beyond the scope of this study.

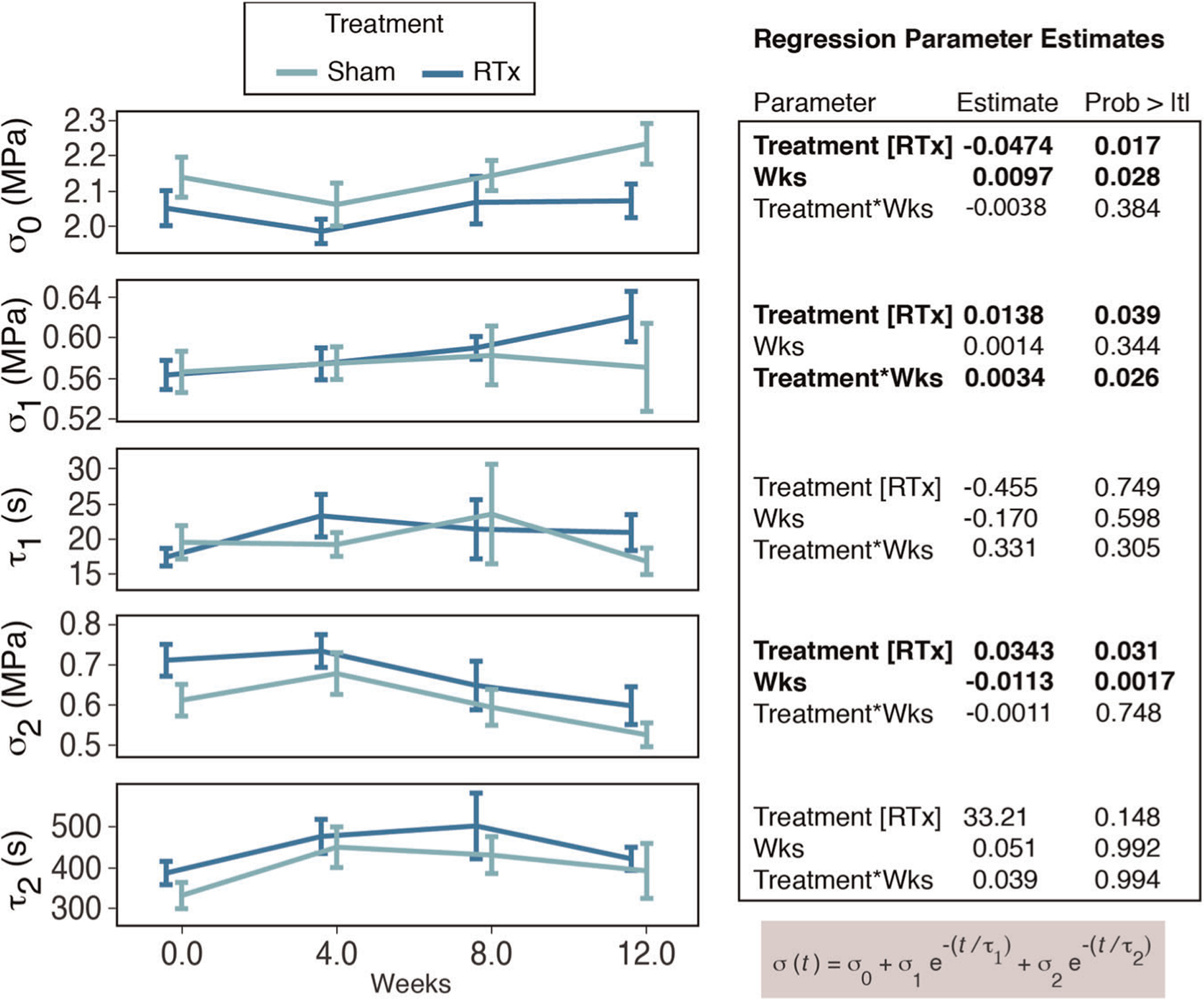

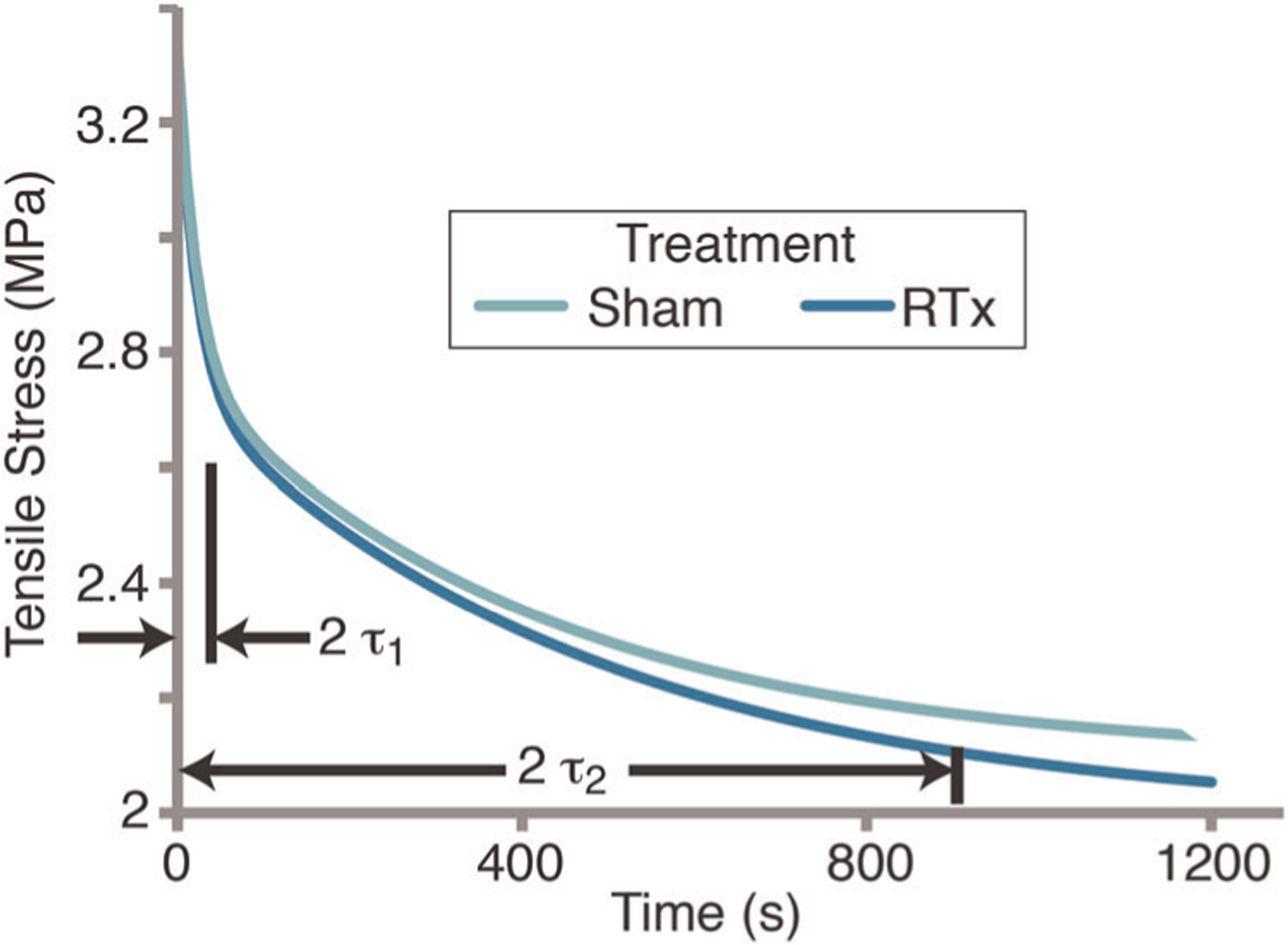

3.3 |. Stress-relaxation

The five-parameter Maxwell–Wiechert model resulted in an excellent fit (r2 = .990 ± .009) for the stress relaxation behavior of the demineralized tibia. The equilibrium stress (σ0) represents the time-independent stress reached during stress relaxation and had a lower least square mean (−4.4%; p = .017; ANCOVA) in the RTx group (2.04 MPa) compared to the Sham group (2.14 MPa; Figure 3). While the equilibrium stress increased with time in vivo (p = .028), the rate of increase was not different (p = .384) for the two treatment groups. The fast-response component (σ1, τ1) of the model had an average time constant of 19.4 s (Table S1). The slow-response component (σ2, τ2) of the model had an average time constant of 450 s. The fast-response magnitude (σ1) was greater for the RTx group compared to the Sham group (+4.8% least square mean, p = .039), but the 12-week time point appears to be primary contributor to this difference. The slow-response magnitude (σ2) was also greater for the RTx group compared to the Sham group (+9.7% least square mean, p = .031), and the mean was greater at all time points for this parameter. The magnitude of the time constants (τ1 and τ2) was not different between the two treatment groups, and also did not vary with time. Plotting the model stress relaxation response (with time in vivo set to 0 weeks) shows that while the overall early time response is similar for the two treatment groups, there is a discrepancy in the amount of stress relaxation over longer time periods (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

The five parameters of the Maxwell–Wiechert phenomenological model are plotted as a function of time in vivo for Sham or RTx treatment groups (mean ± SE). Regression parameter estimates are shown for the independent variables of treatment and time (weeks). Stress (σ) and time constant (τ) components are indicated. RTx, radiation therapy

FIGURE 4.

Stress relaxation for Sham and RTx groups based on mean values from the five-parameter Maxwell–Wiechert model. Short (2 τ1) and long time constant (2 τ2) values are shown representing 87% of exponential decay. Results illustrate a similar relaxation response for short time period (<30 s) with more relaxation for the RTx group for long time periods. RTx, radiation therapy

The equilibrium strain (strain induced by the 3.5 MPa applied stress) was not different between groups with least squares mean of 0.0374 mm/mm for RTx and 0.0364 mm/mm for Sham groups (p = .286, ANCOVA). Dividing the stress parameters (σ0, σ1, σ2) by equilibrium strains results in three elastic moduli (E0, E1, E2); these represent three elastic components situated in parallel in the Maxwell–Wiechert model (Table S2). Because these magnitudes are highly correlated with σ0, σ1, σ2, additional statistical analysis was not performed on the elastic modulus magnitudes.

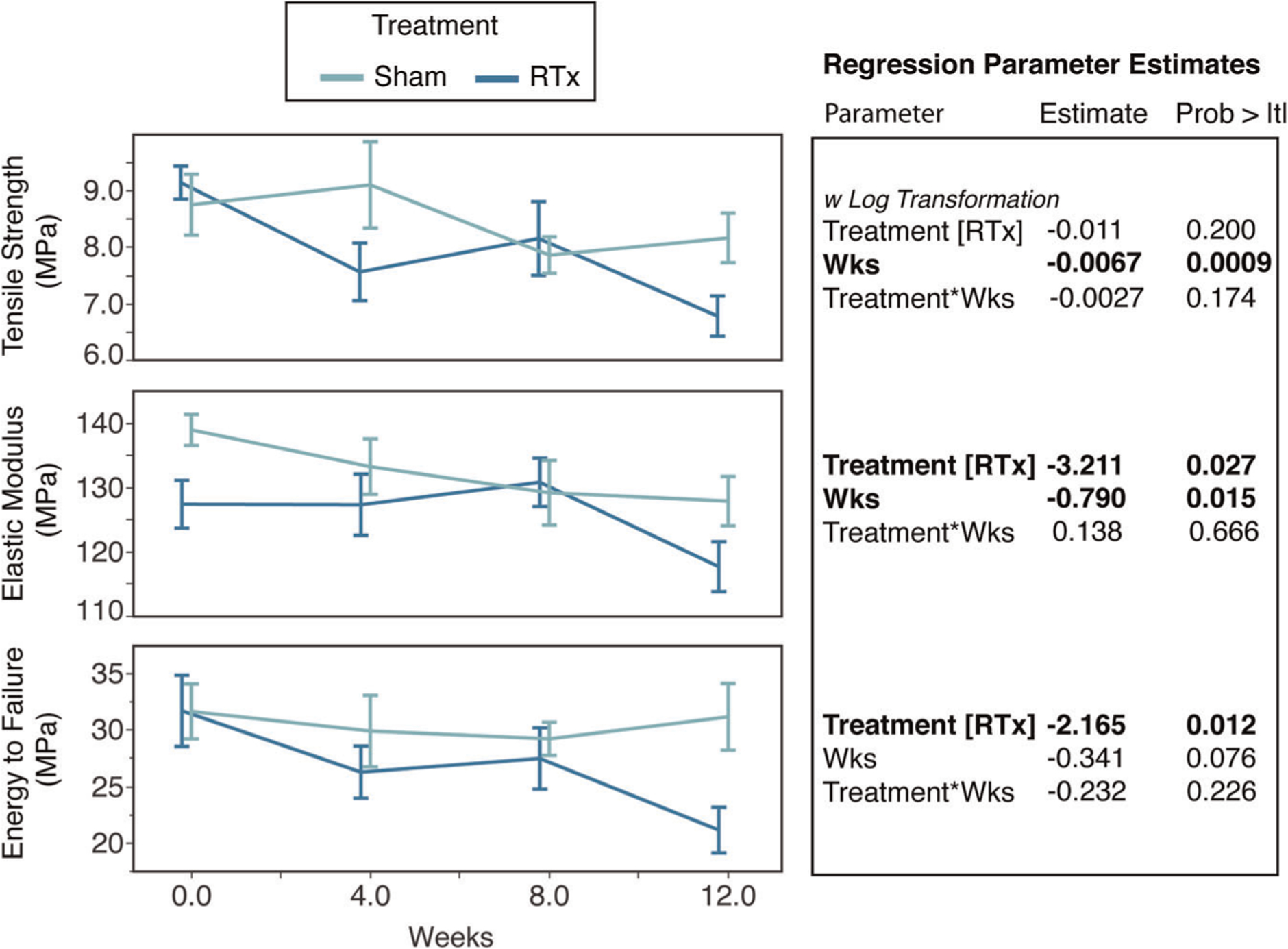

3.4 |. Monotonic tensile test

When tested to failure in tension, there was strain localization of the failure process and the resulting fracture surfaces were generally located in the central third of the demineralized bone gage length with an oblique fracture pattern (Figure 2C). Failure occurred at 47 ± 17% (SD) of the demineralized bone length with distance measured from the distal to proximal grip. The tensile strength (σt) decreased with time (p = .0009; Figure 5), but was not different for the RTx and Sham treatment groups (p = .200; ANCOVA). The elastic modulus (E) of the RTx group (n = 58) was 5.0% lower compared to the Sham group (n = 58; p = .027; ANCOVA; Table S2), and decreased with time (p = .015). The rate of decrease was not different between the two groups (p = .666). The energy to failure (Uf) was also reduced for the RTx treatment group compared to the Sham group (p = .012; ANCOVA) with an average decrease 12.2%. The apparent strain to peak load (εp), with least squares mean of 0.0861 mm/mm for the RTx group and 0.0868 mm/mm for the Sham group, was not different between the two groups (p = .80) and did not depend on time (p = .32). The apparent strain to failure (εf), while 3% lower for the RTx (least squares mean of 0.0998 mm/mm) compared to the Sham group (least squares mean of 0.1029 mm/mm), was not significantly different (p = .23) in the ANCOVA model. Overall, the monotonic tensile tests show that RTx treatment results in decreased elastic modulus and energy to failure compared to Sham treatment, and the decrease is sustained over time.

FIGURE 5.

Monotonic tensile loading results for tensile strength, elastic modulus, and energy to failure are plotted as a function of time in vivo for Sham or RTx treatment groups (mean ± SE). Regression parameter estimates are shown for the independent variables of treatment and time (weeks). RTx, radiation therapy

3.5 |. 25 kGy irradiation as a positive control

Tibiae exposed to 25 kGy γ-irradiation followed by demineralization (25 kGy group) had tensile strength (σt) that was 77% lower (p < .0001; t test) than demineralized bone that was not irradiated (Control group; Table 1). Elastic modulus (E) was 81% lower (p < .0001) and energy to failure was 69% lower (p < .0001) for the 25 kGy group compared to Control group. The apparent strain to peak load (εp) for the 25 kGy group was 60% greater (p < .0001) than the Control group. Similarly, the apparent strain to failure (εf) was 60% greater (p < .0001) for the 25 kGy group compared to Controls.

TABLE 1.

Monotonic tensile test results for samples irradiated with 25 kGy (n = 9 RTx, n = 13 Sham group)

| Parameter | Mean | Median | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σt (MPa) | 25 kGy | 2.00 | 1.96 | 0.65 |

| Control | 8.88 | 9.08 | 1.77 | |

| E (MPa) | 25 kGy | 26.1 | 25.8 | 6.3 |

| Control | 137.5 | 139.3 | 21.8 | |

| Uf (MPa) | 25 kGy | 6.83 | 6.48 | 2.75 |

| Control | 22.3 | 20.1 | 6.56 | |

| εp (mm/mm) | 25 kGy | 0.139 | 0.138 | 0.012 |

| Control | 0.087 | 0.083 | 0.016 | |

| εf (mm/mm) | 25 kGy | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.022 |

| Control | 0.100 | 0.106 | 0.015 |

Note: Tensile strength (σt), elastic modulus (E), energy to failure (Uf), apparent strain to peak load (εp), and apparent strain to failure (εf) are shown.

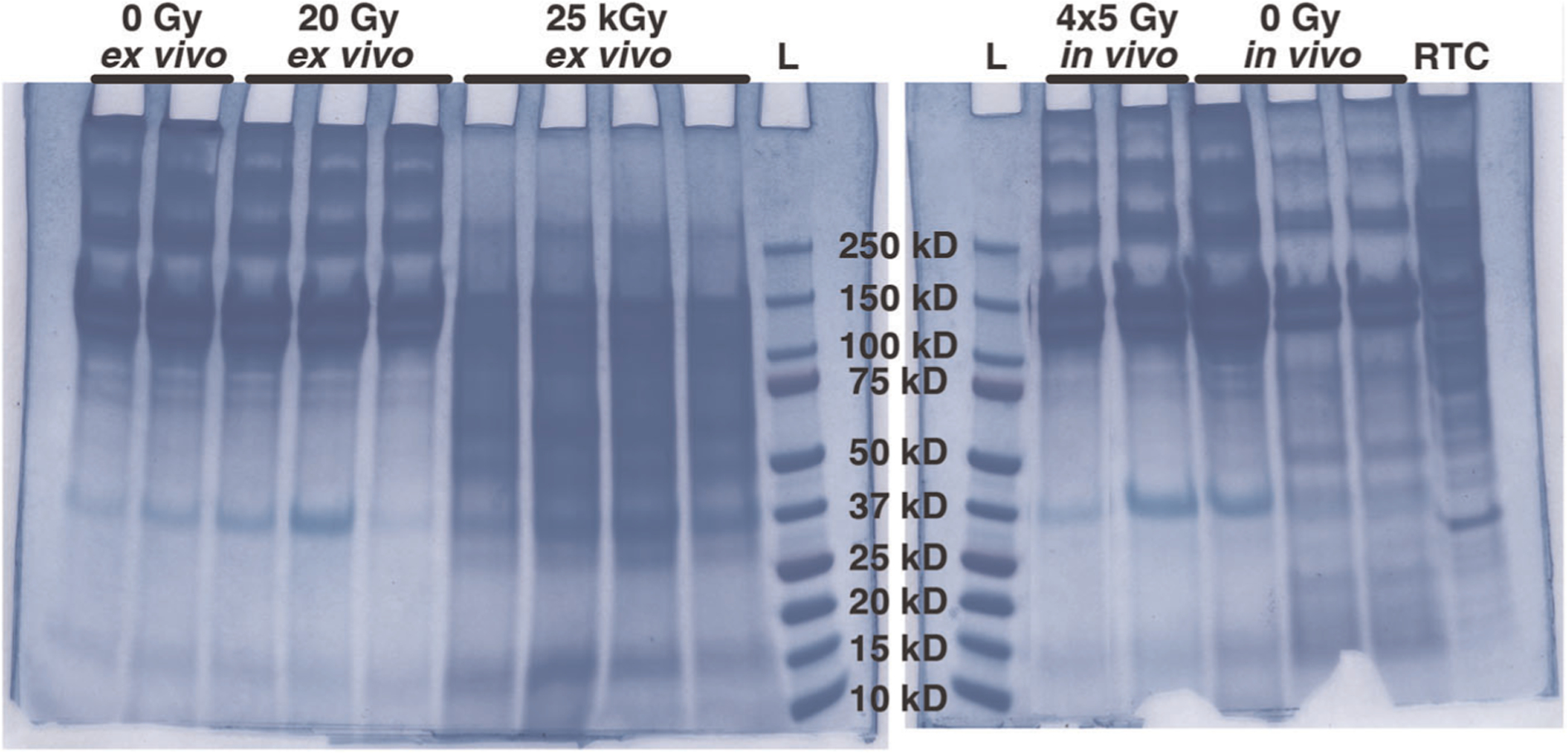

3.6 |. Collagen fragmentation

There was no apparent collagen fragmentation in tibiae from the nonirradiated control group or the groups receiving therapeutic doses of radiation (0 and 12 weeks post-RTx, and 20 Gy ex vivo; Figure 6). The smaller molecular weight bands (<75 kDa) on the 12-week in vivo Sham tibiae are likely a result of normal bone (re)modeling. The positive control, 25 kGy sterilization irradiation, had extensive collagen fragmentation as demonstrated by the decreased signal for higher molecular weight (α, β, γ) collagen bands and increased presence of low molecular weight bands and smearing on the gel (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Collagen fragmentation was assessed using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Intact collagen is observed in the form of α1 and α2 bands (~115–130 kDa) and β11 and β12 bands (~250 kDa) for the 0 Gy, and 20 Gy ex vivo irradiation groups, as well as the 4 × 5 Gy and 0 Gy in vivo groups obtained from animals 12 weeks after treatment. In the 25 kGy ex vivo irradiation group, the α and β bands are diminished, and visible smears indicate collagen fragments less than 100 kDa in size. L, ladder; RTC, rat tail collagen control

4 |. DISCUSSION

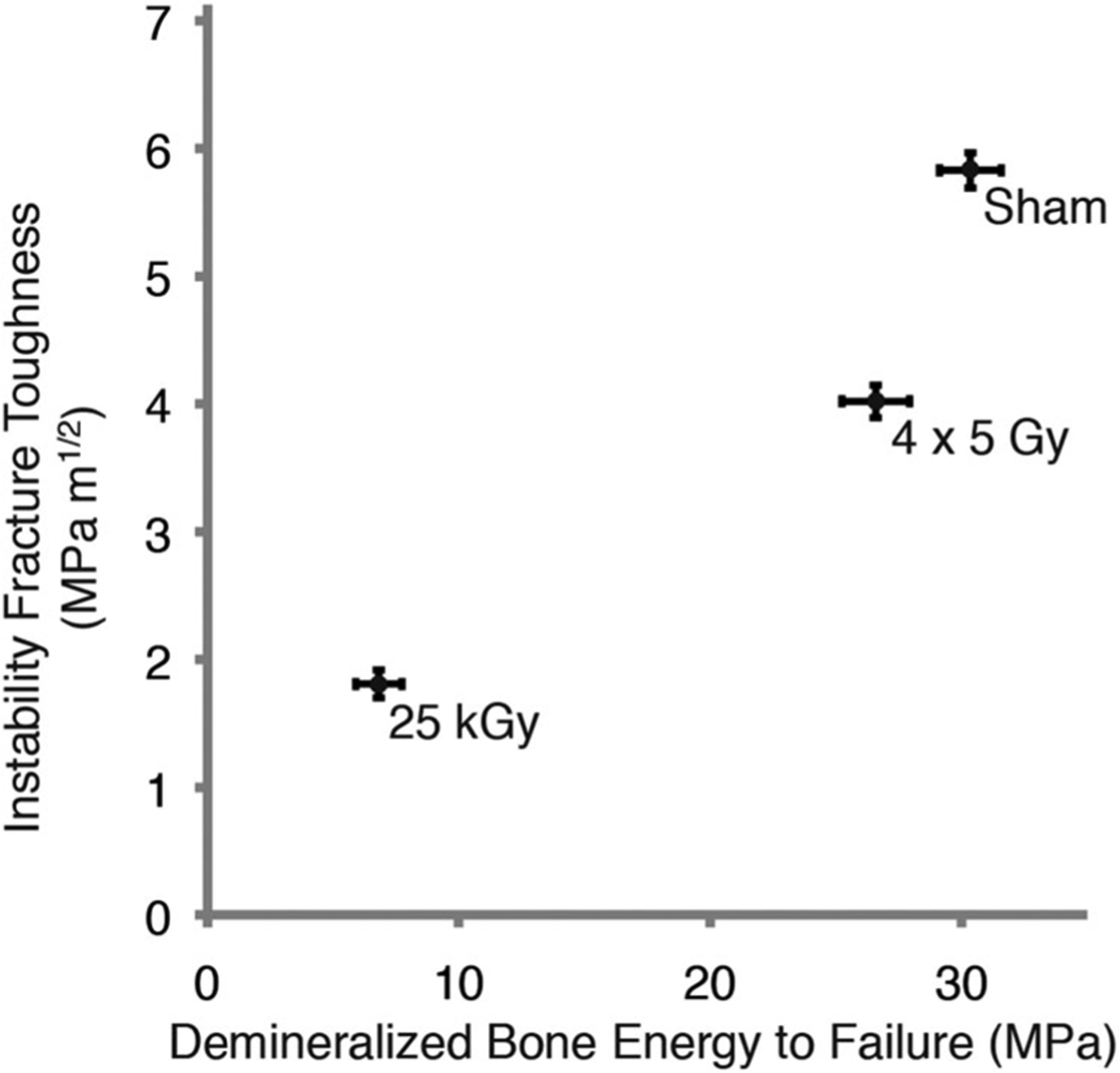

Using a hindlimb model of therapeutic radiation, we found an early and sustained loss of several viscoelastic and monotonic loading mechanical properties (elastic modulus and energy to failure) of demineralized bone, but this alteration was not associated with collagen fragmentation. However, with high dose irradiation, there was extensive collagen fragmentation, and this was associated with a substantial decrease in demineralized bone mechanical properties. There appears to be a correlation between reduced energy to failure of demineralized bone reported here and decreased fracture toughness of mineralized cortical bone (Figure 7)11 with therapeutic doses of radiation, and this effect is amplified with high dose irradiation. These findings suggest that altered collagen mechanical behavior has a role in postradiotherapy bone fragility, but this can occur without detectable collagen fragmentation.

FIGURE 7.

Instability fracture toughness of mineralized cortical bone (as we previously reported)11 increased with greater demineralized bone energy to failure. Mean and SE of mean shown with all-time points grouped together

This work has several experimental limitations. Ideally, a demineralized mouse tibia would exhibit a constant CSA over a long gage length to achieve a large uniform stress field during loading. In this work, we characterized the elastic stress field in the tibiae and describe the variation in the stress field. The central CSA was used to calculate the apparent stress in each tibia, with the understanding that the true peak stress (and strain) were not determined. This is consistent with 3-point bend testing of small laboratory animal bone,33 where uniform geometry along the longitudinal length is assumed. In addition to a nonuniform stress field, a nonuniform strain field develops, particularly during the latter stages of the failure process due to strain localization. The results reported here represent global apparent strains without regard to heterogeneity of the strain field. One alternative approach to address a nonuniform stress/strain field is to fabricate a waisted planar section of demineralized mouse bone.34 This creates some aspects of a near-uniform cross-section but also introduces large strains in the demineralized bone from unfolding and flattening of the medial quadrant of the diaphysis. Nonetheless, the mechanical properties of SAMR1 demineralized femurs using a waisted geometry were similar to results reported here on BALB/cJ mouse tibiae including elastic modulus (waisted: 96 ± 23, tibia: 132 ± 15 MPa), ultimate strain (waisted: 11.9 ± 4.3, tibia: 10.3 ± 1.7%), and ultimate stress (waisted: 9.3 ± 1.5, tibia: 7.9 ± 2.0 MPa).

Compared to therapeutic radiation, bone damage following radiation doses in the kGy range—such as those used to sterilize bone allografts—is relatively well-characterized. Radiation at kGy doses results in loss of bone strength,24,25,35 diminished fracture toughness,35,36 and fragmentation of bone collagen.24–26,36 Our work demonstrates that there is no observable collagen fragmentation following a 20 Gy irradiation exposure. AGEs have been associated with altered bone biomechanics in severe disease states such as uncontrolled diabetes, primarily by stiffening the bone matrix.37 However, there is very little evidence supporting AGEs as a key contributor to postirradiation fractures, and in our model, we do not observe post-RTx stiffening of demineralized bone.37 Postirradiation, AGEs do not accumulate at concentrations sufficient to modulate mechanical properties of bone37 for either kGy24,25 or therapeutic radiation doses.11,19

While neither AGEs nor collagen fragmentation appear to play a significant role in post-radiotherapy bone embrittlement, from the literature on bone matrix-mechanics interactions we can identify several potential factors that may be worthy of future investigation. For example, it is known that collagen fiber integrity (degree of denaturation) and orientation contribute to post-yield toughness of bone.38 Irradiation at kGy doses can increase both collagen denaturation and bound water.39 While loosely bound water is more closely associated with toughness, collagen bound water also contributes to bone toughness (but is not associated with modulus/stiffness).40 Bound water may help to stabilize the mechanical integrity of collagen in some way, perhaps through interaction with matrix glycoproteins, as it has a strong positive correlation with toughness, flexural strength, and post-yield toughness in 3-point bending.41,42 Fragmentation of the amino acid chain, or other forms of denaturation including loss of connectivity, may alter collagen biomechanics directly (e.g., permitting increased molecular uncoiling or slipping between molecules/fibrils) or indirectly (e.g., altering bound water content or mineral-matrix interactions).43 Our previous data from Raman spectroscopy studies of irradiated bone indicate changes in trivalent:divalent collagen crosslink ratio and increased alignment of both mineral and organic phases.18,20 While an increase in trivalent:divalent crosslinking could increase bone strength,44 the role of physiologic crosslink ratios in regulating bone toughness is likely modest. However, increased trivalent crosslinking may also indicate persistence of older bone matrix, which could be associated with increased accumulation of microdamage due to diminished bone remodeling. Increased mineral and matrix alignment may reduce fracture toughness by permitting crack propagation. Mineral crystallinity could contribute to mechanics, as has been shown in aged mice,45 but our Raman data from this model have not shown consistent changes in mineral crystallinity post-RTx.

Like any longitudinal study, the aging of our animals over the duration of the study may impact the outcomes. For this reason, we used age-matched non-irradiated control animals for our Sham group. In our previous studies using this model, we have found animal age does not significantly affect bone morphometry outcomes (as determined by micro-CT), Raman spectroscopy metrics for matrix composition, or biomechanics (3-point bending, axial compression) until 26 weeks post-irradiation (animal age of 32 weeks).12–14,18,20 The effects of radiation on bone are generally much larger than the effects of aging in this model until the animals mature to the point of developing age-related osteopenia. Bone morphology parameters in this model change relatively early post-RTx, where loss of trabecular bone occurs by 4 weeks after radiation, accompanied by a small decrease in mid-diaphyseal femur cross-section and an increase in metaphyseal cortical thickness.12,14 Bone loss from 4 to 26 weeks in irradiated femora is minimally progressive, in part due to diminished local osteoclast activity.12 Biomechanically, the irradiated femora do not progressively lose strength in this model, and age-matched controls lose strength over time, reaching levels comparable to the irradiated femora by 26 weeks post-RTx.13; 14Assessment of the role of aging in this model would depend on the animal age at the time of irradiation, as well as the selected end points. Post-irradiation changes to bone are not monotonic, particularly at time points before 4 weeks, where bone often goes through a transient stage of increased mineral density and strength. If end points occurring between 4 and 26 weeks post-irradiation were evaluated in a study with a large sample size, the effects of aging after irradiation could be quantified. The mouse strain selected for study would also be a key variable, as bone density and bone mass accrual vary greatly between common inbred mouse strains.

Relating collagen biomechanics back to bone fragility is not straightforward. Testing of demineralized bone does not account for the collagen-mineral interactions that also functionally contribute to the material strength of mineralized bone. In the oim/oim mouse model, which lacks the α2 collagen chain, tensile tests of demineralized femurs demonstrated no change in biomechanical behavior compared to controls, while 3-point bending biomechanics of mineralized bone was significantly compromised.46 While increased collagen disorder is associated with decreased bone fatigue failure cycle number in human bone,47 these correlations explain only a subset of the mineralized tissue biomechanics. Bone possesses numerous toughening mechanisms, and correlations between fracture toughness and other bone properties are typically weak-to-moderate (R2 ≈ 25%).48 The numerous, nuanced mechanisms that may regulate post-radiotherapy bone fragility are not well characterized in models of therapeutic radiation dosing, although somewhat better understood from kGy irradiation experiments. It has long been recognized that the viscoelastic properties of bone can be related to bone strength.49 In addition, bone creep has been shown to contribute to bone damage and reduced fatigue life of bone.50 In the current study, we found more stress relaxation for the irradiated group compared to the Sham group. Although the relationship between creep and stress relaxation was not evaluated as part of this study, it would be expected that demineralized bone with extensive stress relaxation would also exhibit more bone creep. Future work could explore creep damage and fatigue damage in demineralized and mineralized bone subjected to therapeutic radiation.

This study specifically illustrates that radiation at therapeutic doses results in more viscoelastic stress-relaxation and reduced energy to failure of organic matrix strength, but this does not occur via collagen fragmentation. Furthermore, neither pathologic accumulation of AGEs nor osteopenia are driving mechanisms behind post-radiotherapy bone fragility. It is likely that these insufficiency fractures result from bone collagen disorganization, denaturation, altered water content, or altered mineral-collagen interactions. These potential mechanisms merit further study, as they could apply not only to RTx models but also other bone damage/fragility pathologies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AR065419 (TAD) and R01AR070142 (MEO), and the David G. Murray Endowment (TAD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Mr. James Boyer for his assistance with the electrophoretic collagen fragmentation assay.

Funding information

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Grant/Award Numbers: AR065419, AR070142; David G. Murray Endowment

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baxter NN. Risk of pelvic fractures in older women following pelvic irradiation. Jama. 2005;294:2587–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickie CI, Parent AL, Griffin AM, et al. Bone fractures following external beam radiotherapy and limb-preservation surgery for lower extremity soft tissue sarcoma: relationship to irradiated bone length, volume, tumor location and dose. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75: 1119–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gortzak Y, Lockwood GA, Mahendra A, et al. Prediction of pathologic fracture risk of the femur after combined modality treatment of soft tissue sarcoma of the thigh. Cancer. 2010;116:1553–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guise TA. Bone loss and fracture risk associated with cancer therapy. The oncologist. 2006;11:1121–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon JW, Huh SJ, Yoon YC, et al. Pelvic bone complications after radiation therapy of uterine cervical cancer: evaluation with MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh D, Huh SJ, Nam H, et al. Pelvic insufficiency fracture after pelvic radiotherapy for cervical cancer: analysis of risk factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1183–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SH, Kim JC, Lee JE, Park IK. Pelvic insufficiency fracture after radiotherapy in patients with cervical cancer in the era of PET/CT. Radiation Oncol J. 2011;29:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulino AC Late effects of radiotherapy for pediatric extremity sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen HHW, Lee BF, Guo HR, Su WR, Chiu NT. Changes in bone mineral density of lumbar spine after pelvic radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2002;62:239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhakal S, Chen J, McCance S, Rosier R, O’Keefe R, Constine LS. Bone density changes after radiation for extremity sarcomas: exploring the etiology of pathologic fractures. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:1158–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartlow CM, Mann KA, Damron TA, Oest ME. Limited field radiation therapy results in decreased bone fracture toughness in a murine model. PloS one. 2018;13:e0204928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oest ME, Franken V, Kuchera T, Strauss J, Damron TA. Long-term loss of osteoclasts and unopposed cortical mineral apposition following limited field irradiation. J Orthop Res. 2015;33:334–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oest ME, Mann KA, Zimmerman ND, Damron TA Parathyroid Hormone (1–34) transiently protects against radiation-induced bone fragility. Calcif tissue int. 2016;98:619–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oest ME, Policastro CG, Mann KA, Zimmerman ND, Damron TA. Longitudinal effects of single hindlimb radiation therapy on bone strength and morphology at local and contralateral sites. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:99–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green DE, Adler BJ, Chan ME, et al. 2013. Altered composition of bone as triggered by irradiation facilitates the rapid erosion of the matrix by both cellular and physicochemical processes. PloS one 8:e64952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willey JS, Lloyd SAJ, Robbins ME, et al. Early increase in osteoclast number in mice after whole-body irradiation with 2 Gy X rays. Radiat Res. 2008;170:388–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright LE, Buijs JT, Kim HS, et al. Single-Limb Irradiation Induces Local and Systemic Bone Loss in a Murine Model. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:1268–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong B, Oest ME, Mann KA, Damron TA, Morris MD. Raman spectroscopy demonstrates prolonged alteration of bone chemical composition following extremity localized irradiation. Bone. 2013;57:252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oest ME, Damron TA. Focal therapeutic irradiation induces an early transient increase in bone glycation. Radiat Res. 2014;181:439–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oest ME, Gong B, Esmonde-White K, et al. Parathyroid hormone attenuates radiation-induced increases in collagen crosslink ratio at periosteal surfaces of mouse tibia. Bone. 2016;86:91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt HB, Torres AM, Palomino PM, et al. Altered tissue composition, microarchitecture, and mechanical performance in cancellous bone from men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:1191–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Illien-Jünger S, Palacio-Mancheno P, Kindschuh WF, et al. Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products Have Sex- and Age-Dependent Effects on Vertebral Bone Microstructure and Mechanical Function in Mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33:437–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viguet-Carrin S, Roux JP, Arlot ME, et al. Contribution of the advanced glycation end product pentosidine and of maturation of type I collagen to compressive biomechanical properties of human lumbar vertebrae. Bone. 2006;39:1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pendleton MM, Emerzian SR, Liu J, et al. Effects of ex vivo ionizing radiation on collagen structure and whole-bone mechanical properties of mouse vertebrae. Bone. 2019;128:115043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton B, Gaspar A, Josey D, Tupy J, Grynpas MD, Willett TL. Bone embrittlement and collagen modifications due to high-dose gamma-irradiation sterilization. Bone. 2014;61:71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Açil Y, Springer IN, Niehoff P, et al. Proof of direct radiogenic destruction of collagen in vitro. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie. 2007;183:374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akkus O, Belaney RM, Das P. Free radical scavenging alleviates the biomechanical impairment of gamma radiation sterilized bone tissue. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernández-García M, Yañez RM, Sánchez-Domínguez R, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells enhance the engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells in an autologous mouse transplantation model. Stem Cell Res Therap. 2015;6:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen H, Cassady AI, Bennett MB, et al. Reducing the radiation sterilization dose improves mechanical and biological quality while retaining sterility assurance levels of bone allografts. Bone. 2013;57: 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attia T, Woodside M, Minhas G, et al. Development of a novel method for the strengthening and toughening of irradiation-sterilized bone allografts. Cell Tissue Bank. 2017;18:323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller KS, Connizzo BK, Feeney E, et al. 2012. Collagen Fiber Re-Alignment and Mechanical Properties in a Mouse Supraspinatus Tendon Model: Examining Changes With Age and Location. ASME 2012 Summer Bioengineering Conference. Fajardo, Puerto Rico, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen ZL, Kahn H, Ballarini R, Eppell SJ. Viscoelastic properties of isolated collagen fibrils. Biophys J. 2011;100:3008–3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vashishth D Small animal bone biomechanics. Bone. 2008;43: 794–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva MJ, Brodt MD, Wopenka B, et al. Decreased collagen organization and content are associated with reduced strength of demineralized and intact bone in the SAMP6 mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barth HD, Launey ME, Macdowell AA, Ager JW, Ritchie RO. On the effect of X-ray irradiation on the deformation and fracture behavior of human cortical bone. Bone. 2010;46:1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akkus O, Rimnac CM. Fracture resistance of gamma radiation sterilized cortical bone allografts. J Orthop Res. 2001;19: 927–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vashishth D, Gibson GJ, Khoury JI, Schaffler MB, Kimura J, Fyhrie DP. Influence of nonenzymatic glycation on biomechanical properties of cortical bone. Bone. 2001;28:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unal M, Jung H, Akkus O. Novel raman spectroscopic biomarkers indicate that postyield damage denatures bone’s collagen. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:1015–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flanagan CD, Unal M, Akkus O, Rimnac CM. Raman spectral markers of collagen denaturation and hydration in human cortical bone tissue are affected by radiation sterilization and high cycle fatigue damage. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2017;75:314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manhard MK, Uppuganti S, Granke M, Gochberg DF, Nyman JS, Does MD. MRI-derived bound and pore water concentrations as predictors of fracture resistance. Bone. 2016;87:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Unal M, Creecy A, Nyman JS. The role of matrix composition in the mechanical behavior of bone. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018;16:205–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unal M, Akkus O. Raman spectral classification of mineral- and collagen-bound water’s associations to elastic and post-yield mechanical properties of cortical bone. Bone. 2015;81:315–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willett TL, Dapaah DY, Uppuganti S, Granke M, Nyman JS. Bone collagen network integrity and transverse fracture toughness of human cortical bone. Bone. 2019;120:187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banse X, Sims TJ, Bailey AJ. Mechanical properties of adult vertebral cancellous bone: correlation with collagen intermolecular cross-links. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akkus O, Adar F, Schaffler MB. Age-related changes in physicochemical properties of mineral crystals are related to impaired mechanical function of cortical bone. Bone. 2004;34:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller E, Delos D, Baldini T, Wright TM, Pleshko Camacho N. Abnormal mineral-matrix interactions are a significant contributor to fragility in oim/oim bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;81:206–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du JY, Flanagan CD, Bensusan JS, Knusel KD, Akkus O, Rimnac CM. Raman biomarkers are associated with cyclic fatigue life of human allograft cortical bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Unal M, Uppuganti S, Timur S, Mahadevan-Jansen A, Akkus O, Nyman JS. Assessing matrix quality by Raman spectroscopy helps predict fracture toughness of human cortical bone. Sci Rep. 2019;9: 7195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter DR, Hayes WC. The compressive behavior of bone as a two-phase porous structure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:954–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bowman SM, Guo XE, Cheng DW, et al. Creep contributes to the fatigue behavior of bovine trabecular bone. J Biomech Eng. 1998; 120:647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.