Abstract

Bacterial conjugation is a widespread and particularly efficient strategy to horizontally disseminate genes in microbial populations. With a rich and dense population of microorganisms, the intestinal microbiota is often considered a fertile environment for conjugative transfer and a major reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes. In this mini-review, we summarize recent findings suggesting that few conjugative plasmid families present in Enterobacteriaceae transfer at high rates in the gut microbiota. We discuss the importance of mating pair stabilization as well as additional factors influencing DNA transfer efficiency and conjugative host range in this environment. Finally, we examine the potential repurposing of bacterial conjugation for microbiome editing.

Keywords: bacterial conjugation, microbiota, conjugative plasmids (CP), mating pair stabilization, antibiotic resistance

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance continues to rise worldwide, with alarming projections suggesting that antibiotic-resistant infections could become the second most common cause of death by 2050 (O’ Neil, 2014). This led many research groups to study the global collection of antibiotic resistance genes, also called the resistome (Carattoli, 2013; Penders et al., 2013; van Schaik, 2015; Casals-Pascual et al., 2018), and to identify the intestinal microbiota as a major reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes (Ravi et al., 2014). The complex microbial communities found in the gut are dense and composed of diverse bacteria phyla (Turnbaugh et al., 2007; Qin et al., 2010), a context thought to be particularly favorable for horizontal gene transfer (Liu et al., 2012; Soucy et al., 2015) and antibiotic resistance gene dissemination (San Millan, 2018). Given that the intestinal microbiota also contains a variety of pathobionts (Palleja et al., 2018; Bakkeren et al., 2019), understanding the molecular mechanisms driving the spread of antibiotic resistance genes is particularly important to prevent infections that could become difficult or impossible to treat.

Horizontal gene transfer mechanisms include transformation, transduction, and bacterial conjugation. Bacterial conjugation is considered a major contributor to gene transfer and to the emergence of new antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Conjugative transfer is a well characterized phenomenon during which a donor bacterium assembles a type IV secretion system (T4SS) and transfers DNA to a recipient bacterium in close contact (Cascales and Christie, 2003; Alvarez-Martinez and Christie, 2009; Arutyunov and Frost, 2013; Virolle et al., 2020). Although thoroughly investigated in test tubes and Petri dishes, the study of bacterial conjugation in the intestinal microbiota remains far less characterized with most evidence being provided by epidemiologic studies (Norman et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2013; Soucy et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016; San Millan, 2018). IncF, IncI, IncA, IncC, and IncH plasmids are the most frequently encountered in humans and animals (Rozwandowicz et al., 2018) but few studies have quantified the transmission of mobile genetic elements in situ and described the underlying mechanisms. This mini-review summarizes recent findings on bacterial conjugation in the gut microbiome with a focus on enterobacteria.

The Mobility of Genes in the Gut Microbiota

Many studies have reported conjugative transfer of plasmids in the intestinal microbiota (Licht and Wilcks, 2005). For instance, conjugation was found to occur with plasmids of different incompatibility groups (Table 1) harbored by Gram-negative (Kasuya, 1964; Reed et al., 1969; Jones and Curtiss, 1970; Duval-Iflah et al., 1980, 1994; Corpet et al., 1989; Garrigues-Jeanjean et al., 1999; Licht et al., 1999, 2003; García-Quintanilla et al., 2008; Stecher et al., 2012; Aviv et al., 2016; Gumpert et al., 2017; Bakkeren et al., 2019; Neil et al., 2020; Ott et al., 2020) or Gram-positive bacteria (Doucet-Populaire et al., 1991, 1992; McConnell et al., 1991; Schlundt et al., 1994; Igimi et al., 1996; Jacobsen et al., 1999; Moubareck et al., 2003; Lester et al., 2004). Most studies focused on Escherichia coli as the donor bacterium but lactic acid bacteria have also been investigated because of their abundance in fermented food products (Igimi et al., 1996). Despite major implications on microbial evolution and on the emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms facilitating bacterial conjugation in the gut microbiota remains sparse (Norman et al., 2009; Soucy et al., 2015; Casals-Pascual et al., 2018).

TABLE 1.

Transfer rates of various conjugative elements in the intestinal microbiota.

| Name | Inc group | Resistance | Isolated in | Donor strain | Recipient strain | Transfer rates†in vitro** | Transfer rates†in situ | MPS family | Genbank | References |

| pAMβ1 | 18 | Er, Lc | Enterococcus faecalis | Lactococcus lactis IL1403 | Enterococcus faecalis HS32 | 2.3 × 10–3 | <1 × 10–7 (a) | Not reported | NC_ 013514.1 | Igimi et al., 1996 |

| pAT191 (synthetic)* | 18 | Km | Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus faecalis BM4110 | Escherichia coli K802N::Tn10 | 5 × 10–9 | 3 × 10–9 (a) | Not reported | Not deposited | Doucet-Populaire et al., 1992 |

| pAM714 | HIy | Er | Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus faecalis FA2-2 | Enterococcus faecalis JH2SS | ∼1 × 10–2 | 1.4 × 10–1 (b) | Not reported | Not deposited | Huycke et al., 1992 |

| pAM771 | HIy | Er | Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus faecalis FA2-2 | Enterococcus faecalis JH2SS | Not reported | 2.9 × 10–2 (b) | Not reported | Not deposited | Huycke et al., 1992 |

| pCAL1/pCAL2 | Not found | Er | Enterococcus faecium | Enterococcus faecium 160/00 | Enterococcus faecium 64/3-RFS | 2 × 10–5 | ∼1 × 10–6 (a) | Not reported | Not deposited | Lester et al., 2004 |

| pCF10 | Not found | Tc | Enterococcus faecalis | Enterococcus faecalis OG1RFS | Enterococcus faecalis OG1SS | Data not shown | ∼1 × 10–3 (c) | Not reported | NC_ 006827.2 | Licht et al., 2002 |

| Tn1545 | –**** | Km, Er, Tc | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Enterococcus faecalis BM4110 | Listeria monocytogenes LO17RF | 2.5 × 10–7 | 1.1 × 10–8 (a) | Not reported | AM903082.1 | Doucet-Populaire et al., 1991 |

| Tn916 | –**** | Tc | Bacillus subtilis | Enterococcus faecalis OG1SS | Enterococcus faecalis OG1RF | 1.1 × 10–5 | ∼1 × 10–9 (d) | Not reported | KM516885.1 | Bahl et al., 2004 |

| pYD1 | Not found | 14 antibiotic resistance markers | Serratia liquefasciens | Serratia liquefasciens | Escherichia coli | Not reported | ∼1 × 10–6 (a) | Not reported | Not deposited | Duval-Iflah et al., 1980 |

| ROR-1 | Not found | Tc | Not found | Escherichia coli M7-18 | Escherichia coli x820 | ∼1 × 10–5 | ∼1 × 10–4 (a) | Not reported | Not deposited | Jones and Curtiss, 1970 |

| pIP72 | B/O | Km | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 3.57 × 10–4 | 3.56 × 10–5 (a) | PilV | MN612051.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| pVCR94ΔX3 | C | Km | Vibrio cholerae | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 3.23 × 10–3 | Not detected (a) | TraN | KF551948.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| pSLTΔfinO | F | Km | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium SV5535 | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium SV5534 | 5 × 10–4 | 5 × 10–5 (a) | TraN | AE006471.2 | García-Quintanilla et al., 2008 |

| pOX38 | FI | Sp, Tc, Su | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 6.82 × 10–2 | 4.89 × 10–5 (a) | TraN | MF370216.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| RIP71a | FII | Ap, Tc, Cm, Sm, Sp | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 2.64 × 10–3 | 7.87 × 10–4 (a) | TraN | MN626601 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| R1 | FII | Km, Cm, Su, Sp | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 2.97 × 10–3 | 1.6 × 10–4 (a) | TraN | KY749247.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| R1drd19 | FII | Km, Cm, Su, Sp, Ap | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi B | Escherichia coli BJ4 | Escherichia coli BJ4 | ∼1 × 10–1 | ∼1 × 10–3 (a) | TraN | Not deposited | Licht et al., 1999 |

| pCVM29188_146 | FIIA | Sm, Tc | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Kentucky | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Kentucky | Escherichia coli HS-4 | ∼1 × 10–4 | ∼5 × 10–4 (a) | TraN | CP001122.1 | Ott et al., 2020 |

| TP123 | HI1 | Sm, Cm, Su, Sp | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 8.05 × 10–3 | Not detected (a) | TraN | MN626602.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| R64 | I1α | Sm, Tc | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 5.51 × 10–4 | 1.54 × 10–6 (a) | PilV | NC_ 005014.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| p2kan | I1 | Km | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 | Escherichia coli | 7.53 × 10–3 to 5.20 × 10–9 | ∼1 × 100 (a) | PilV | Not deposited | Stecher et al., 2012 |

| pHUSEC41-1 | I1 | Su, Ap, Sm, Pip | Escherichia coli HUSEC41 | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli | Not reported | Not reported (a) | PilV | NC_ 018995.1 | Gumpert et al., 2017 |

| pES1 | I1 | Tc, Su, Tr | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Infantis | Escherichia coli | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 | 1.2 × 10–6 | 2 × 10–7 (a) | PilV | NZ_ CP047882.1 | Aviv et al., 2016 |

| TP114 | I2 | Km | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 7.05 × 10–3 | 1.12 × 10–1 (a) | PilV | MF521836.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| pIP69 | L/M | Ap, Km, Tc | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 9.73 × 10–7 | Not detected (a) | Not reported | MN626603 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| RP1/RP4 | P1α | Ap, Km, Tc | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Escherichia coli HB101 | Escherichia coli X7 | 2.05 × 10–1 | 9.21 × 10–5 (a) | None | BN000925.1 | Rang et al., 1996 |

| Escherichia coli BJ4 | Escherichia coli BJ4 | 2.56 × 10–2 | Not detected*** (a) | None | BN000925.1 | Licht et al., 2003 | ||||

| pRK24 (derived from RK2) | Ap, Tc | Enterobacter aerogenes | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 4.07 × 10–1 | Not detected (a) | None | Not deposited | Neil et al., 2020 | |

| pRts1 | T | Km, Sp | Proteus vulgaris | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 2.63 × 10–4 | Not detected (a) | TraN | MN626604 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| R388 | W | Su, Tm | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 3.09 × 10–4 | Not detected (a) | None | NC_028464 | Neil et al., 2020 |

| Escherichia coli UB1832 | Escherichia coli UB281 | ∼1 (100) | ∼1 × 10–4 (a) | None | NC_028464 | Duval-Iflah et al., 1994, 1998 | ||||

| R6K | X2 | Ap, Sm | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | Escherichia coli Nissle1917 | 1.21 × 10–2 | 2.5 × 10–4 (a) | Not reported | LT827129.1 | Neil et al., 2020 |

*Derived from pAMβ1 conjugative plasmid, has pBR322 origin of replication.

**Measure taken for conjugation on agar plate.

***In conditions not selecting for transconjugants.

****Conjugative transposons integrate into the chromosome of their host, and hence, plasmid incompatibility groups do not apply.

†Transconjugants/recipients.

(a) Mice model; (b) Hamster model; (c) Pig model; (d) rat model.

MPS family is indicated as “not reported” when the exact mechanism has not been described or with “none” when experimental evidence show that this function is absent.

Several environmental conditions resembling those encountered in the intestinal tract were investigated in vitro and shown to influence conjugation (Rang et al., 1996). For example, the transfer rates of conjugative plasmids pES1 and pSLT were shown to be affected by lower oxygen levels and the presence of bile salt or by other factors such as NaCl concentration and temperature (García-Quintanilla et al., 2008; Aviv et al., 2016). Other plasmids were shown to be inhibited by the presence of mammalian cells in co-cultures, raising the possibility that human host secreted factors could affect plasmid transfer rates (Lim et al., 2008; Machado and Sommer, 2014). A pioneering study reported in 1999 that IncF plasmid R1drd19 can transfer between two E. coli strains within the mouse gut microbiome at rates similar to those obtained on agar plates (Licht et al., 1999). This led to the hypothesis that bacterial mating may occur in a stable matrix, most likely after the formation of biofilm in the gut. In situ transfer rates were also quantified directly in the mouse intestinal microbiota for other conjugative plasmids (Table 1). However, different models with several experimental variables were used. For example, different mice models ranging from germ-free to antibiotic-treated mice have been reported (Licht and Wilcks, 2005). Another important variable comes from the nature of the donor strain and recipient strains, which were shown to affect transfer rates in the gut (Ott et al., 2020). While some studies introduced and probed specific bacteria as recipient cells for conjugation, other investigations used endogenous residents of the microbiota. Furthermore, mixing donors and recipient strains before their introduction in the mice (Stecher et al., 2012) could also introduce differences since conjugation could occur between the two strains before or in the stomach immediately after their introduction in mice rather than in the intestinal microbiota. Taken together, these variations in experimental models make the comparison of transfer rates difficult between studies.

A recent study by our group adopted a standardized assay to evaluate and compare the mobility of conjugative plasmids in the mouse gut microbiota (Neil et al., 2020). Transfer rates were quantified for 13 conjugative plasmids representing 10 of the major conjugative plasmids incompatibility groups found in Enterobacteriaceae (Table 1). This work was performed in streptomycin-treated mice to deplete endogenous enterobacteria and facilitate the establishment of E. coli Nissle, 1917 derivatives as the donor and recipient bacteria. This work revealed that few conjugative plasmids were able to efficiently transfer in situ using this model, without any correlation with in vitro conjugation rates. A surprising finding was that incompatibility group I2 (IncI2) plasmid TP114 displayed only modest conjugation efficiencies in vitro but reached very high transfer rates in the intestinal microbiota, which prompted a more thorough investigation of this plasmid. A first observation was that hypoxic conditions increased the relatively modest TP114 in vitro transfer rates to very high frequencies of conjugation in situ. Transposon mutagenesis coupled to conjugation experiments also highlighted the crucial role of a group of genes encoding an accessory type IVb pilus (T4P) for TP114 conjugation in the intestinal tract (Neil et al., 2020). The T4P is a structure found in I-complex plasmids (IncB/O, IncI1, IncI2, IncK, and IncZ) that was previously proposed to stabilize the mating-pair in order to allow conjugation in unstable environments (Ishiwa and Komano, 2000; Praszkier and Pittard, 2005).

Mating-Pair Stabilization Mechanisms

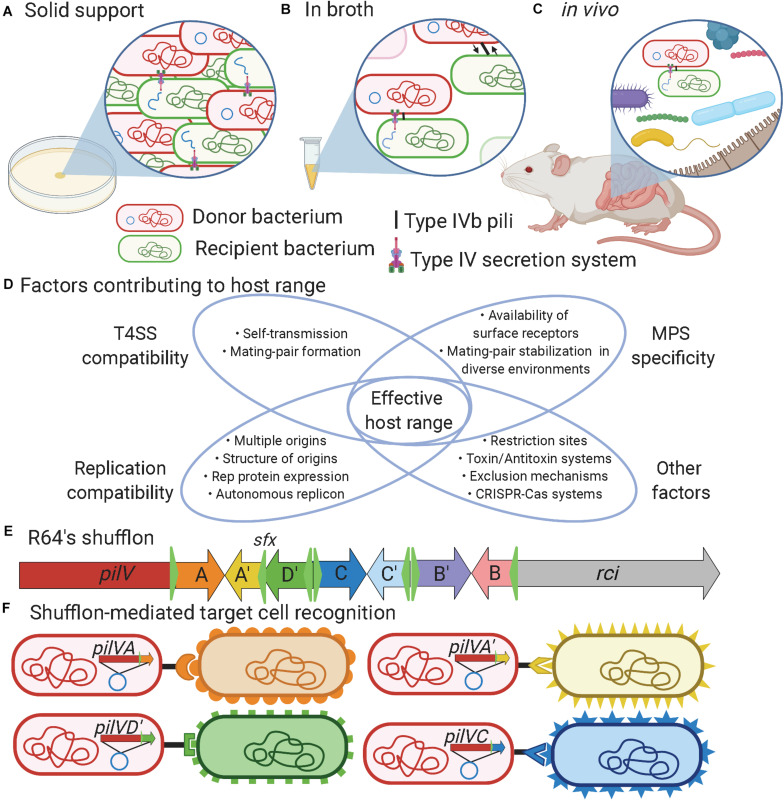

The T4SS is a sophisticated nanomachine that plays an essential role in the transfer of DNA and/or protein macromolecules during bacterial conjugation. An important step during this process is mating-pair formation (MPF), which brings the donor and recipient bacteria in close contact (Chandran Darbari and Waksman, 2015; Christie, 2016; Virolle et al., 2020). In enterobacteria, two basic forms of conjugative pilus are associated with T4SS, either thin flexible or thick rigid, which influences the ability to support conjugation in liquid or solid environments (Arutyunov and Frost, 2013; Chandran Darbari and Waksman, 2015; Virolle et al., 2020). Besides MPF, a generally overlooked step called mating-pair stabilization (MPS) may be needed to keep the donor and recipient cells together long enough to allow successful DNA transfer. MPS is especially important in broth/in vivo conditions where bacterial mobility, flow forces, and other environmental factors could perturb the interaction between the donor and recipient cells (Clarke et al., 2008; Figures 1A–C). MPS relies on adhesins either displayed at the surface of the bacterium or on specialized pili (Hospenthal et al., 2017; González-Rivera et al., 2019). In enterobacteria, conjugative pili involved in MPS can be divided into two groups: conjugative pili and type IVb pili (T4Pb) that respectively comprise the traN or pilV adhesins (Neil et al., 2020). Additional MPS mechanisms might exist, as proposed for plasmid R6K (Neil et al., 2020), since this phenomenon remains poorly characterized in most mobile genetic elements.

FIGURE 1.

Factors influencing bacterial conjugation. (A) Bacterial conjugation taking place on solid support provides high cell density and close proximity between donor and recipient cells that facilitate mating-pair formation to enable plasmid transfer. (B) Bacteria evolving in liquid environments or (C) in vivo benefit from mating-pair stabilization (MPS) provided either by F-pili or type IVb pili to bring cells together and keep them in close contact during plasmid transfer. (D) Venn diagram showing the factors contributing to the effective host range of a mobile genetic element. (E) Schematic representation of R64’s shufflon where the C-terminus region of the pilV gene can undergo DNA rearrangement catalyzed by the shufflase (rci) to allow expression of seven variants of PilV. For example, DNA region A could be exchanged to express A′. (F) DNA rearrangement of the shufflon in the donor strain determines recipient specificity when mating occurred in broth/in vivo conditions. Created in BioRender.com.

Different types of conjugative pilus were reported in enterobacteria (Bradley, 1980), but the most studied is probably the F-pili (Smillie et al., 2010; Arutyunov and Frost, 2013; Koraimann, 2018). The establishment of contact between donor and recipient cells can be considered as the first rate-limiting step in conjugation as well as a key determinant for plasmid host range specificity (Virolle et al., 2020; Figure 1D). F-type pili elaborate long, thin and flexible pili that extend by polymerization of the TraA major pilin into a helical filament ranging from 1 to 20 μm in length (Christie, 2016; Koraimann, 2018). Upon contact, the F-pilus retracts, presumably by depolymerization, enabling donor cells to bring the recipient cell into close proximity for the formation of the mating pore (Clarke et al., 2008; Hospenthal et al., 2017). TraN, also named tivF6 (Thomas et al., 2017), is an essential component for DNA transfer machinery that promotes the formation of stable donor-recipient mating-pair by interacting with OmpA or lipopolysaccharides (Klimke et al., 2005). F-pili have also been shown to promote biofilm formation, which favors plasmid transfer (Ghigo, 2001).

Type IVb pili encoded on conjugative plasmids are required only for conjugation in broth (Kim and Komano, 1997) or in the gastrointestinal tract but not on solid support (Neil et al., 2020). T4Pb are thin, flexible, helical fibers distinct from the T4SS that are mainly composed of major pilin and PilV minor adhesins that are thought to be localized to the tip of the pilus. A single motor ATPase encoding gene is predicted in T4Pb, making the extension and retraction of the pilus uncertain since two ATPases are generally present in other types of T4P (Craig et al., 2019; Ellison et al., 2019). T4Pb structures can be found encoded in all plasmid families within the I-complex (IncB/O, IncI1, IncI2, IncK, and IncZ), which were grouped based on similar morphological and serological properties of their pili (Falkow et al., 1974; Bradley, 1984; Rozwandowicz et al., 2020). The adhesin gene in I-complex plasmids is generally the last gene of the T4Pb operon and its C-terminal portion comprises a shufflon (Figure 1E). The shufflon is a dynamic DNA locus that can be re-arranged by a shufflase, encoded by rci (recombinase for clustered inversion), thought to be constitutively active in IncI plasmids (Brouwer et al., 2019). The shufflase recognizes specific DNA sequences called sfx (green triangles in Figure 1E) and promotes the recombination by inversion between two head-to-head sfx sites (Gyohda et al., 2002). This results in variations of the C-terminal sequence of the minor pilin PilV (Komano, 1999), thus changing the specificity of these pili to recognize different structures in lipopolysaccharides (Ishiwa and Komano, 2000) or other cell surface appendages (Figure 1F).

Factors Influencing Conjugation in the Gut Microbiota

The gut microbiota is a complex assembly of microorganisms (Lloyd-Price et al., 2016). The high density of bacteria in this environment could thus be seen as a favorable context for conjugative elements to promote their dissemination (Norman et al., 2009). However, several factors that can act at different steps of conjugative transfer can limit the host spectrum or affect the transfer rates of conjugative elements (Figure 1D). The first barrier to bacterial conjugation in the gut is the regulation of mobile genetic element transfer genes by environmental conditions (Fernandez-Lopez et al., 2014; Getino and de la Cruz, 2018). For example, plasmid TP114 was found to be active by low oxygen concentrations (Neil et al., 2020). Many conjugative plasmids respond to specific conditions that may not be found in the gut and hence cannot reach high transfer rates in this environment (García-Quintanilla et al., 2008; Aviv et al., 2016; Neil et al., 2020). In some cases, MPS could be essential or significantly increase transfer rates by establishing and stabilizing the contact between the donor and recipient bacteria (Neil et al., 2020). For this purpose, conjugative elements may use adhesins that recognize receptors at the surface of recipient bacteria (Ishiwa and Komano, 2004). However, in certain environmental niches such as in a biofilm, the role of adhesins and MPS might not be as important, allowing the T4SS to enter in contact with potentially more diverse bacterial species (Król et al., 2013). The T4SS of the conjugative element also has to penetrate the recipient bacterium cell wall and membrane. The drastically different structures of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria represent a physical barrier that is likely restraining the host range of some conjugative plasmids (Domaradskiǐ, 1985). Surface or entry exclusion represent more sophisticated mechanisms that impact conjugation (Garcillán-Barcia and De La Cruz, 2008; Arutyunov and Frost, 2013). In addition, DNA molecules that are successfully transferred must not be targeted by restriction enzymes or CRISPR-Cas systems (Wilkins, 2002; Garneau et al., 2010; Roy et al., 2020). Conjugative plasmids also have to interact with the cellular machinery of their new host to allow the expression of their genes and their maintenance. Establishing the host range of a particular conjugative element is thus a complex task that requires careful investigation of several factors (Jain and Srivastava, 2013) such as the environmental conditions, the nature of the host and recipient bacteria along with other key phenomena such as MPS, MPF, gene expression, and plasmid replication (Figure 1D).

The Relation Between Conjugative Plasmids in the Gut

Most in situ conjugation studies to date have used simplified models involving a single conjugative element present in the donor bacterium (Neil et al., 2020; Ott et al., 2020). This does not necessarily represent natural conditions as gut Enterobacteriaceae isolates often harbor multiple plasmids (Lyimo et al., 2016; Martino et al., 2019). Mobile genetic elements were shown to have complex relationships (Getino and de la Cruz, 2018). Some conjugative plasmids, such as IncI plasmids, encode transcription factors that inhibit IncF plasmid conjugation (Gasson and Willetts, 1975, 1976, 1977; Gaffney et al., 1983; Ham and Skurray, 1989). In other cases, the regulatory proteins from a conjugative plasmid or an integrative and conjugative element (ICE) can activate gene expression in other mobile genetic elements such as genomic islands. In an elegant study, it was also shown that some mobile genetic islands such as SGI1, encodes for T4SS subunits that can reshape the mating apparatus of IncC plasmid pVCR94 to promote SGI1 self-propagation over pVCR94 conjugation (Carraro et al., 2017). SGI1 was also found to destabilize pVCR94 maintenance mechanisms. Examples of these types of relationships are plentiful, illustrating how frequent the interaction between mobile genetic elements must be in natural environments (Harmer et al., 2016).

Some plasmids, such as the P-type systems (RP4, R388, and pKM101) lack MPS and display lower conjugation rates in unstable environments such as culture broth or the gut microbiota (Chandran Darbari and Waksman, 2015; Neil et al., 2020). For instance, IncP plasmid RP4 showed no transfer in the intestinal tract in absence of antibiotic selection for the transconjugants (Licht et al., 2003). However, conjugation was shown to have implications in the stability of IncP plasmid pKJK5 in the intestinal microbiota of germ-free rats (Bahl et al., 2007). Other evidence suggests that these plasmids could highjack MPS mechanisms from other conjugative elements found in the same donor cells in a parasitic manner (Gama et al., 2017). This strategy could be beneficial to some plasmids, allowing their own transfer in a stable environment while taking advantage of other plasmids MPS systems in unstable environments. Therefore, plasmids that do not encode MPS systems should not be deemed strictly incapable of transferring in the gut microbiota. Additional work will be needed to evaluate, characterize and quantify this phenomenon and could bring new insights on the mobility of genes in the gut microbiota.

Conclusion and Applications of this Knowledge

Bacterial conjugation can reach high transfer rates in the gut microbiota. Direct evidence suggests that MPS plays an important role in this environment but the genes that are involved in this mechanism are not encoded in all plasmid families (Neil et al., 2020). MPS has been overlooked by many groups since it is not required in classical bacterial conjugation assays on agar plates where cells are already in close contact. Plasmids encoding MPS genes could hence be seen as the most versatile conjugation machinery since they can promote DNA transfer under a wider diversity of conditions. Conjugative elements that do not encode MPS mechanisms could exploit plasmids that possess this feature to promote their dissemination. Understanding the interactions between plasmids in the gut microbiota could thus provide important insights on the dissemination of antibiotic resistance.

Alternatives to conventional antibiotics include, among other, vaccines (Scully et al., 2015), phage therapy (Ando et al., 2015; Nobrega et al., 2015), predatory bacteria (Dwidar et al., 2012), and anti-plasmid or anti-conjugation strategies (Thomas and Nielsen, 2005; Williams and Hergenrother, 2008; Oyedemi et al., 2016; Cabezón et al., 2017; Getino and de la Cruz, 2018). Inhibiting horizontal gene transfer in the intestinal microbiota will require the identification of potential drug targets. Given that MPS appears to be important for bacterial conjugation in the gut (Neil et al., 2020), strategies to limit or abolish this function could lower the spread of antibiotic resistance (Craig et al., 2019). This type of technology could be used in conjunction with antibiotic treatments or before medical procedures to limit the risk of resistance to treatment (Buelow et al., 2017).

Increased knowledge of bacterial conjugation in situ will also be instrumental to the development of microbiome editing technologies. Using a highly effective conjugative system, genes providing benefits to their host could be transferred and integrated into the chromosome of natural residents of the microbiota, avoiding probiotic colonization resistance (Ronda et al., 2019). This DNA mobilization technology could also be used as a CRISPR-Cas delivery vehicle (Bikard et al., 2014; Citorik et al., 2014; Yosef et al., 2015; Getino and de la Cruz, 2018; Neil et al., 2019). CRISPR could be programmed to eliminate specific bacteria causing dysbiosis, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, or pathogens, providing a precision tool for microbiome editing (Bikard and Barrangou, 2017). One could also imagine that MPS could be tuned to facilitate transfer to targeted bacterial populations while leaving other microorganisms untouched by the procedure. The study of bacterial conjugation could thus provide important knowledge that could be applicable in several aspects of the fight against antibiotic resistance.

Author Contributions

KN, NA, and SR contributed to the initial conceptualization of the review. KN and NA did initial literature reviews and manuscript drafting. SR contributed to the literature review and extensive manuscript editing. All authors contributed to the final proofs and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have filed a patent application for the use of conjugative plasmids for microbiome editing. KN and SR are co-founders of TATUM bioscience.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com software.

Footnotes

Funding. SR held a chercheur boursier junior 2 fellowship from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS). KN was the recipient of a graduate research scholarship from the Fond de Recherche du Québec-Nature et Technologie (FRQNT) and from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). NA was supported by a doctoral scholarship from the Université de Sherbrooke.

References

- Alvarez-Martinez C. E., Christie P. J. (2009). Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol. Mol.Biol.Rev. 73 775–808. 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando H., Lemire S., Pires D. P., Lu T. K. (2015). Engineering modular viral scaffolds for targeted bacterial population editing. Cell Syst. 1 187–196. 10.1016/j.cels.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arutyunov D., Frost L. S. (2013). F conjugation: back to the beginning. Plasmid 70 18–32. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviv G., Rahav G., Gal-Mor O. (2016). Horizontal transfer of the Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis resistance and virulence plasmid pESI to the gut microbiota of warm-blooded hosts. mBio 7 e1395–e1416. 10.1128/mBio.01395-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahl M. I., Hansen L. H., Licht T. R., Sørensen S. J. (2007). Conjugative transfer facilitates stable maintenance of IncP-1 plasmid pKJK5 in Escherichia coli cells colonizing the gastrointestinal tract of the germ-free rat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 341–343. 10.1128/AEM.01971-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahl M. I., Sørensen S. J., Hansen L. H., Licht T. R. (2004). Effect of tetracycline on transfer and establishment of the tetracycline-inducible conjugative transposon Tn916 in the guts of gnotobiotic rats. App. Environ. Microbiol. 70 758–764. 10.1128/AEM.70.2.758-764.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkeren E., Huisman J. S., Fattinger S. A., Hausmann A., Furter M., Egli A., et al. (2019). Salmonella persisters promote the spread of antibiotic resistance plasmids in the gut. Nature 573 276–280. 10.1038/s41586-019-1521-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikard D., Barrangou R. (2017). Using CRISPR-Cas systems as antimicrobials. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 37 155–160. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikard D., Euler C. W., Jiang W., Nussenzweig P. M., Goldberg G. W., Duportet X., et al. (2014). Exploiting CRISPR-Cas nucleases to produce sequence-specific antimicrobials. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 1146–1150. 10.1038/nbt.3043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D. E. (1980). Determination of pili by conjugative bacterial drug resistance plasmids of incompatibility groups B, C, H, J, K, M, V, and X. J. Bacteriol. 141 828–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D. E. (1984). Characteristics and function of thick and thin conjugative pili determined by transfer-derepressed plasmids of incompatibility groups I1, I2, I5, B, K, Z. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130 1489–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer M. S. M., Jurburg S. D., Harders F., Kant A., Mevius D. J., Roberts A. P., et al. (2019). The shufflon of IncI1 plasmids is rearranged constantly during different growth conditions. Plasmid 102 51–55. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelow E., Bello González T. d. j, Fuentes S., de Steenhuijsen Piters W. A. A., Lahti L., Bayjanov J. R., et al. (2017). Comparative gut microbiota and resistome profiling of intensive care patients receiving selective digestive tract decontamination and healthy subjects. Microbiome 5:88. 10.1186/s40168-017-0309-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabezón E., de la Cruz F., Arechaga I. (2017). Conjugation inhibitors and their potential use to prevent dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 8:2329. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A. (2013). Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303 298–304. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro N., Durand R., Rivard N., Anquetil C., Barrette C., Humbert M., et al. (2017). Salmonella genomic island 1 (SGI1) reshapes the mating apparatus of IncC conjugative plasmids to promote self-propagation. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006705. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casals-Pascual C., Vergara A., Vila J. (2018). Intestinal microbiota and antibiotic resistance: perspectives and solutions. Hum. Microbiome J. 9 11–15. 10.1016/j.humic.2018.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E., Christie P. J. (2003). The versatile bacterial type IV secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1 1–7. 10.1038/nrmicro753.THE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran Darbari V., Waksman G. (2015). Structural biology of bacterial type IV secretion systems. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 84 603–629. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062911-102821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chavda K. D., Al Laham N., Melano R. G., Jacobs M. R., Bonomo R. A., et al. (2013). Complete nucleotide sequence of a blaKPC-harboring IncI2 plasmid and its dissemination in New Jersey and New York hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 5019–5025. 10.1128/AAC.01397-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie P. J. (2016). The mosaic type IV secretion systems. EcoSal Plus 7 1–34. 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0020-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citorik R. J., Mimee M., Lu T. K. (2014). Sequence-specific antimicrobials using efficiently delivered RNA-guided nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 1141–1145. 10.1038/nbt.3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M., Maddera L., Harris R. L., Silverman P. M. (2008). F-pili dynamics by live-cell imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 17978–17981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpet D. E., Lumeau S., Corpet F. (1989). Minimum antibiotic levels for selecting a resistance plasmid in a gnotobiotic animal model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33 535–540. 10.1128/AAC.33.4.535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig L., Forest K. T., Maier B. (2019). Type IV pili: dynamics, biophysics and functional consequences. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17 429–440. 10.1038/s41579-019-0195-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domaradskiǐ I. V. (1985). The role of surface structures of recipient cells in bacterial conjugation. Mol. Gen. Microbiol. Viruses 12 3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet-Populaire F., Trieu-Cuot P., Andremont A., Courvalin P. (1992). Conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Enterococcus faecalis to Escherichia coli in digestive tracts of gnotobiotic mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36 502–504. 10.1128/AAC.36.2.502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet-Populaire F., Trieu-Cuot P., Dosbaa I., Andremont A., Courvalin P. (1991). Inducible transfer of conjugative transposon Tn1545 from Enterococcus faecalis to Listeria monocytogenes in the digestive tracts of gnotobiotic mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35 185–187. 10.1128/AAC.35.1.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval-Iflah Y., Gainche I., Ouriet M. F., Lett M. C. (1994). Recombinant DNA transfer to Escherichia coli of human faecal origin in vitro and in digestive tract of gnotobiotic mice. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 15 79–87. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1994.tb00232.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duval-Iflah Y., Maisonneuve S., Ouriet M. F. (1998). Effect of fermented milk intake on plasmid transfer and on the persistence of transconjugants in the digestive tract of gnotobiotic mice. Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 73 95–102. 10.1023/A:1000603828184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval-Iflah Y., Raibaud P., Tancrede C., Rousseau M. (1980). R-plasmid transfer from Serratia liquefaciens to Escherichia coli in vitro and in vivo in the digestive tract of gnotobiotic mice associated with human fecal flora. Infect. Immun. 28 981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwidar M., Monnappa A. K., Mitchell R. J. (2012). The dual probiotic and antibiotic nature of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. BMB Rep. 45 71–78. 10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.2.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison C. K., Kan J., Chlebek J. L., Hummels K. R., Panis G., Viollier P. H., et al. (2019). A bifunctional ATPase drives Tad pilus extension and retraction. Sci. Adv. 5:eaay2591. 10.1126/sciadv.aay2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkow S., Guerry P., Hedges R. W., Datta N. (1974). Polynucleotide sequence relationships among plasmids of the I compatibility complex. J. Gen. Microbiol. 85 65–76. 10.1128/jb.107.1.372-374.1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez R., del Campo I., Revilla C., Cuevas A., de la Cruz F. (2014). Negative feedback and transcriptional overshooting in a regulatory network for horizontal gene transfer. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004171. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney D., Skurray R., Willetts N., Brenner S. (1983). Regulation of the F conjugation genes studied by hybridization and tra-lacZ fusion. J. Mol. Biol. 168 103–122. 10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80325-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama J. A., Zilhão R., Dionisio F. (2017). Conjugation efficiency depends on intra and intercellular interactions between distinct plasmids: plasmids promote the immigration of other plasmids but repress co-colonizing plasmids. Plasmid 93 6–16. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Quintanilla M., Ramos-Morales F., Casadesús J. (2008). Conjugal transfer of the Salmonella enterica virulence plasmid in the mouse intestine. J. Bacteriol. 190 1922–1927. 10.1128/JB.01626-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcillán-Barcia M. P., De La Cruz F. (2008). Why is entry exclusion an essential feature of conjugative plasmids? Plasmid 60 1–18. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau J. E., Dupuis M. È, Villion M., Romero D. A., Barrangou R., Boyaval P., et al. (2010). The CRISPR/cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA. Nature 468 67–71. 10.1038/nature09523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigues-Jeanjean N., Wittmer A., Ouriet M. F., Duval-Iflah Y. (1999). Transfer of the shuttle vector pRRI207 between Escherichia coli and Bacteroides spp. in vitro and in vivo in the digestive tract of axenic mice and in gnotoxenic mice inoculated with a human microflora. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 29 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gasson M. J., Willetts N. S. (1975). Five control systems preventing transfer of Escherichia coli K 12 sex factor F. J. Bacteriol. 122 518–525. 10.1128/jb.122.2.518-525.1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasson M. J., Willetts N. S. (1976). Transfer gene expression during fertility inhibition of the Escherichia coli K12 sex factor by the I-like plasmid R62. Mol. Gen. Genet. 149 329–333. 10.1007/BF00268535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasson M. J., Willetts N. S. (1977). Further characterization of the F fertility inhibition systems of “unusual” Fin+ plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 131 413–420. 10.1128/jb.131.2.413-420.1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getino M., de la Cruz F. (2018). Natural and artificial strategies to control the conjugative transmission of plasmids. Microbiol. Spectr. 6 33–64. 10.1128/microbiolspec.mtbp-0015-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghigo J. M. (2001). Natural conjugative plasmids induce bacterial biofilm development. Nature 412 442–445. 10.1038/35086581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Rivera C., Khara P., Awad D., Patel R., Li Y. G., Bogisch M., et al. (2019). Two pKM101-encoded proteins, the pilus-tip protein TraC and Pep, assemble on the Escherichia coli cell surface as adhesins required for efficient conjugative DNA transfer. Mol. Microbiol. 111 96–117. 10.1111/mmi.14141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumpert H., Kubicek-Sutherland J. Z., Porse A., Karami N., Munck C., Linkevicius M., et al. (2017). Transfer and persistence of a multi-drug resistance plasmid in situ of the infant gut microbiota in the absence of antibiotic treatment. Front. Microbiol. 8:1852. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyohda A., Furuya N., Kogure N., Komano T. (2002). Sequence-specific and non-specific binding of the Rci protein to the asymmetric recombination sites of the R64 shufflon. J. Mol. Biol. 318 975–983. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00195-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham L. M., Skurray R. (1989). Molecular analysis and nucleotide sequence of finQ, a transcriptional inhibitor of the F plasmid transfer genes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216 99–105. 10.1007/BF00332236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C. J., Hamidian M., Ambrose S. J., Hall R. M. (2016). Destabilization of IncA and IncC plasmids by SGI1 and SGI2 type Salmonella genomic islands. Plasmid 8 51–57. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospenthal M. K., Costa T. R. D., Waksman G. (2017). A comprehensive guide to pilus biogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15 365–379. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huycke M. M., Gilmore M. S., Jett B. D., Booth J. L. (1992). Transfer of pheromone-inducible plasmid between Enterococcus faecalis in the Syrian hamster gastrointestinal tract. J. Infect. Dis. 166 1188–1191. 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igimi S., Ryu C. H., Park S. H., Sasaki Y., Sasaki T., Kumagai S. (1996). Transfer of conjugative plasmid pAMβ1 from Lactococcus lactis to mouse intestinal bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 23 31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwa A., Komano T. (2000). The lipopolysaccharide of recipient cells is a specific receptor for PilV proteins, selected by shufflon DNA rearrangement, in liquid matings with donors bearing the R64 plasmid. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263 159–164. 10.1007/s004380050043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwa A., Komano T. (2004). PilV adhesins of plasmid R64 thin pili specifically bind to the lipopolysaccharides of recipient cells. J. Mol. Biol. 343 615–625. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen B. L., Skou M., Hammerum A. M., Jensen L. B. (1999). Horizontal transfer of the satA gene encoding streptogramin a resistance between isogenic Enterococcus faecium strains in the gastrointestinal tract of gnotobiotic rats. Microbial Ecol. Health Dis. 11 241–247. 10.1080/08910609908540834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Srivastava P. (2013). Broad host range plasmids. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 348 87–96. 10.1111/1574-6968.12241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. T., Curtiss R. (1970). Genetic exchange between Escherichia coli strains in the mouse intestine. J. Bacteriol. 103 71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya M. (1964). Transfer of drug resistance between enteric bacteria induced in the mouse intestine. J. Bacteriol. 88 322–328. 10.1128/JB.88.2.322-328.1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. R., Komano T. (1997). The plasmid R64 thin pilus identified as a type IV pilus. J. Bacteriol. 179 3594–3603. 10.1128/jb.179.11.3594-3603.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimke W. A., Rypien C. D., Klinger B., Kennedy R. A., Rodriguez-Maillard J. M., Frost L. S. (2005). The mating pair stabilization protein, TraN, of the F plasmid is an outer-membrane protein with two regions that are important for its function in conjugation. Microbiol. 151 3527–3540. 10.1099/mic.0.28025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano T. (1999). Shufflons: multiple inversion systems and integrons. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33 171–191. 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koraimann G. (2018). Spread and persistence of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes: a ride on the F plasmid conjugation module. EcoSal Plus 8 1–23. 10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0003-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Król J. E., Wojtowicz A. J., Rogers L. M., Heuer H., Smalla K., Krone S. M., et al. (2013). Invasion of E. coli biofilms by antibiotic resistance plasmids. Plasmid 70 110–119. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester C. H., Frimodt-Moller N., Hammerum A. M. (2004). Conjugal transfer of aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance between Enterococcus faecium isolates in the intestine of streptomycin-treated mice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 235 385–391. 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.04.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht T. R., Wilcks A. (2005). Conjugative gene transfer in the gastrointestinal environment. Advan. Appl. Microbiol. 58 77–95. 10.1016/S0065-2164(05)58002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht T. R., Christensen B. B., Krogfelt K. A., Molin S. (1999). Plasmid transfer in the animal intestine and other dynamic bacterial populations: the role of community structure and environment. Microbiol. 145 2615–2622. 10.1099/00221287-145-9-2615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht T. R., Laugesen D., Jensen L. B., Jacobsen B. L. (2002). Transfer of the pheromone-inducible plasmid pCF10 among Enterococcus faecalis microorganisms colonizing the intestine of mini-pigs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68 187–193. 10.1128/AEM.68.1.187-193.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht T. R., Struve C., Christensen B. B., Poulsen R. L., Molin S., Krogfelt K. A. (2003). Evidence of increased spread and establishment of plasmid RP4 in the intestine under sub-inhibitory tetracycline concentrations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 44 217–223. 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00016-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y. M., de Groof A. J. C., Bhattacharjee M. K., Figurski D. H., Schon E. A. (2008). Bacterial conjugation in the cytoplasm of mouse cells. Infect. Immun. 76 5110–5119. 10.1128/IAI.00445-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Chen X., Skogerbø G., Zhang P., Chen R., He S., et al. (2012). The human microbiome: a hot spot of microbial horizontal gene transfer. Genomics 100 265–270. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Price J., Abu-Ali G., Huttenhower C. (2016). The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 8:51. 10.1186/s13073-016-0307-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo B., Buza J., Subbiah M., Temba S., Kipasika H., Smith W., et al. (2016). IncF plasmids are commonly carried by antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli isolated from drinking water sources in northern Tanzania. Int. J. Microbiol. 2016:3103672. 10.1155/2016/3103672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado A. M. D., Sommer M. O. A. (2014). Human intestinal cells modulate conjugational transfer of multidrug resistance plasmids between clinical Escherichia coli isolates. PLoS One 9:e100739. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino F., Tijet N., Melano R., Petroni A., Heinz E., De Belder D., et al. (2019). Isolation of five Enterobacteriaceae species harbouring blaNDM-1 and mcr-1 plasmids from a single pediatric patient. PLoS One 14:e0221960. 10.1371/journal.pone.0221960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell M. A., Mercer A. A., Tannock G. W. (1991). Transfer of plasmid pAMβl between members of the normal microflora inhabiting the murine digestive tract and modification of the plasmid in a Lactobacillus reuteri host. Microbial. Ecol. Health Dis. 4 343–355. 10.3109/08910609109140149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moubareck C., Bourgeois N., Courvalin P., Doucet-Populaire F. (2003). Multiple antibiotic resistance gene transfer from animal to human enterococci in the digestive tract of gnotobiotic mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47 2993–2996. 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2993-2996.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil K., Allard N., Grenier F., Burrus V., Rodrigue S. (2020). Highly efficient gene transfer in the mouse gut microbiota is enabled by the Incl2 conjugative plasmid TP114. Commun. Biol. 3:523. 10.1038/s42003-020-01253-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil K., Allard N., Jordan D., Rodrigue S. (2019). Assembly of large mobilizable genetic cargo by Double Recombinase Operated Insertion of DNA (DROID). Plasmid 104:102419. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2019.102419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega F. L., Costa A. R., Kluskens L. D., Azeredo J. (2015). Revisiting phage therapy: new applications for old resources. Trends Microbiol. 23 185–191. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman A., Hansen L. H., Sørensen S. J. (2009). Conjugative plasmids: vessels of the communal gene pool. Phil. Trans. R. Soc.B Biol. Sci. 364 2275–2289. 10.1098/rstb.2009.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’ Neil J. (2014). Antimicrobial Resistance?: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations. In Rev. Antimicrob. Resist. Available online at: https://amrreview.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf (accessed 28 January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Ott L. C., Stromberg Z. R., Redweik G. A. J., Wannemuehler M. J., Mellata M. (2020). Mouse genetic background affects transfer of an antibiotic resistance plasmid in the gastrointestinal tract. MSphere 5:e847–19. 10.1128/msphere.00847-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyedemi B. O. M., Shinde V., Shinde K., Kakalou D., Stapleton P. D., Gibbons S. (2016). Novel R-plasmid conjugal transfer inhibitory and antibacterial activities of phenolic compounds from Mallotus philippensis (Lam.) Mull. Arg. J. Glob. Antimicrobial Resis. 5 15–21. 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palleja A., Mikkelsen K. H., Forslund S. K., Kashani A., Allin K. H., Nielsen T., et al. (2018). Recovery of gut microbiota of healthy adults following antibiotic exposure. Nat. Microbiol. 3 1255–1265. 10.1038/s41564-018-0257-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penders J., Stobberingh E. E., Savelkoul P. H. M., Wolffs P. F. G. (2013). The human microbiome as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 4:87. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praszkier J., Pittard A. J. (2005). Control of replication in I-complex plasmids. Plasmid 53 97–112. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Li R., Raes J., Arumugam M., Burgdorf K. S., Manichanh C., et al. (2010). A human gut microbial gene catalog established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464 59–65. 10.1038/nature08821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang C. U., Kennan R. M., Midtvedt T., Chao L., Conway P. L. (1996). Transfer of the plasmid RP1 in vivo in germ free mice and in vitro in gut extracts and laboratory media. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 19 133–140. 10.1016/0168-6496(95)00087-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi A., Avershina E., Ludvigsen J., L’Abée-Lund T. M., Rudi K. (2014). Integrons in the intestinal microbiota as reservoirs for transmission of antibiotic resistance genes. Pathogens 3 238–248. 10.3390/pathogens3020238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed N. D., Sieckmann D. G., Georgi C. E. (1969). Transfer of infectious drug resistance in microbially defined mice. J. Bacteriol. 100 22–26. 10.1128/jb.100.1.22-26.1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronda C., Chen S. P., Cabral V., Yaung S. J., Wang H. H. (2019). Metagenomic engineering of the mammalian gut microbiome in situ. Nat. Methods 16 167–170. 10.1038/s41592-018-0301-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D., Huguet K. T., Grenier F., Burrus V. (2020). IncC conjugative plasmids and SXT/R391 elements repair double-strand breaks caused by CRISPR-Cas during conjugation. Nucl. Acids Res. 48 8815–8827. 10.1093/nar/gkaa518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozwandowicz M., Brouwer M. S. M., Fischer J., Wagenaar J. A., Gonzalez-Zorn B., Guerra B., et al. (2018). Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73 1121–1137. 10.1093/jac/dkx488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozwandowicz M., Hordijk J., Bossers A., Zomer A. L., Wagenaar J. A., Mevius D. J., et al. (2020). Incompatibility and phylogenetic relationship of I-complex plasmids. Plasmid 109:102502. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2020.102502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Millan A. (2018). Evolution of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in the clinical context. Trends Microbiol. 26 978–985. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlundt J., Saadbye P., Lohmann B., Jacobsen B. L., Nielsen E. M. (1994). Conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA between Lactococcus lactis strains and distribution of transconjugants in the digestive tract of gnotobiotic rats. Microbial Ecol. Health Dis. 7 59–69. 10.3109/08910609409141574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scully I. L., Swanson K., Green L., Jansen K. U., Anderson A. S. (2015). Anti-infective vaccination in the 21st century-new horizons for personal and public health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 27 96–102. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie C., Garcillán-Barcia M. P., Francia M. V., Rocha E. P. C., de la Cruz F. (2010). Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74 434–452. 10.1128/mmbr.00020-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy S. M., Huang J., Gogarten J. P. (2015). Horizontal gene transfer: building the web of life. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16 472–482. 10.1038/nrg3962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B., Denzler R., Maier L., Bernet F., Sanders M. J., Pickard D. J., et al. (2012). Gut inflammation can boost horizontal gene transfer between pathogenic and commensal Enterobacteriaceae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 1269–1274. 10.1073/pnas.1113246109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Li X. P., Yang R. S., Fang L. X., Huo W., Li S. M., et al. (2016). Complete nucleotide sequence of an IncI2 plasmid co-harboring blaCTX-M-55 and mcr-1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 5014–5017. 10.1128/AAC.00774-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. M., Nielsen K. M. (2005). Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3 711–721. 10.1038/nrmicro1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. M., Thomson N. R., Cerdeño-Tárraga A. M., Brown C. J., Top E. M., Frost L. S. (2017). Annotation of plasmid genes. Plasmid 91 61–67. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Ley R. E., Hamady M., Fraser-Liggett C. M., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2007). The human microbiome project. Nature 449 804–810. 10.1038/nature06244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik W. (2015). The human gut resistome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 370:20140087. 10.1098/rstb.2014.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virolle C., Goldlust K., Djermoun S., Bigot S., Lesterlin C. (2020). Plasmid transfer by conjugation in Gram-negative bacteria: from the cellular to the community level. Genes 11:1239. 10.3390/genes11111239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins B. M. (2002). Plasmid promiscuity: meeting the challenge of DNA immigration control. Environ. Microbiol. 4 495–500. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. J., Hergenrother P. J. (2008). Exposing plasmids as the Achilles’ heel of drug-resistant bacteria. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12 389–399. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.015.Exposing [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosef I., Manor M., Kiro R., Qimron U. (2015). Temperate and lytic bacteriophages programmed to sensitize and kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 7267–7272. 10.1073/pnas.1500107112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]