Abstract

Although evidence for the application of an albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grading system to assess liver function in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is available, less is known whether it can be applied to determine the prognosis of single HCC with different tumor sizes. This study aimed to address this gap.

Here, we enrolled patients who underwent hepatectomy due to single HCC from 2010 to 2014. Analyses were performed to test the potential of the ALBI grading system to monitor the long-term survival of single HCC subjects with varying tumor sizes.

A total of 265 participants were recruited. The overall survival (OS) among patients whose tumors were ≤7 cm was remarkably higher than those whose tumors were >7 cm. The Cox proportional hazards regression model identified the tumor differentiation grade, ALBI grade, and maximum tumor size as key determinants of OS. The ALBI grade could stratify the patients who had a single tumor ≤7 cm into 2 distinct groups with different prognoses. The OS between ALBI grades 1 and 2 was comparable for patients who had a single tumor >7 cm.

We showed that the ALBI grading system can predict disease outcomes in patients with a single HCC with a tumor size ≤7 cm. However, the ALBI grade may not predict the prognosis of patients with a single tumor >7 cm.

Keywords: albumin-bilirubin grade, child-pugh grade, hepatocellular carcinoma, overall survival, tumor size

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a highly aggressive form of cancer. Current statistics rank HCC as the sixth most prevalent cancer disease in the world. Moreover, cancer has been reported to be the third most prevalent cause of cancer-associated deaths worldwide.[1] Treatment of HCC has remained a challenge to date. When diagnosed early, resection can be performed to remove the affected part; other therapeutic options such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy can be used to kill the tumors that may have metastasized. Therefore, surgical resection is still the main treatment option for a single HCC.[2] However, as this form of tumor is very aggressive, recurrence is common even after surgical resection; very early diagnosis is necessary to ensure successful treatment and to improve the disease outcome.

The guidelines of the Barcelona Clinic for Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system stipulates that hepatic surgery is only suitable for early-stage tumors (stages 0 and A: single tumors or multinodular tumors with size ≤3 cm, Child-Pugh A or B, PS 0, and ≤3 nodules with no vascular invasion).[3] The size of a tumor is a significant determinant of disease outcomes of patients with HCC. A tumor with a large diameter is correlated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with HCC.[4,5] Johnson et al proposed a novel way of assessing the function of the liver termed the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade. This has been verified to be an ideal tool for evaluating the liver function of patients with HCC. The model involves the use of only serum albumin and bilirubin and avoids subjective parameters such as ascites and encephalopathy.[6] The ALBI grade was verified as a precise prognostic model for patients with advanced HCC and receiving sorafenib,[7] for patients with solitary HCC within the Milan criteria,[8] for patients with early-stage HCC who have been treated by radiofrequency ablation,[9] and for different BCLC stages of HCC.[10] However, the association between the size of single tumors of patients with HCC and the ALBI grade is not sufficiently understood.

Herein, we examined the potential of the ALBI grade to assess the clinical outcomes of HCC with varying tumor sizes.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

Patients with HCC who received hepatectomy in our ward from 2010 to 2014 were recruited. HCC was diagnosed by pathological examination of prepared liver specimens by a qualified pathologist. Only patients who had the following features were included in the study: ALBI grade 1 or 2 for liver function; no treatment for HCC before hepatectomy, single tumor without macrovascular invasion, and the absence of lymph node metastasis. The patients were classified into subgroups on the basis of the size of tumors: group I, tumor sizes ≤3 cm; group II, tumor sizes >3 and ≤5 cm; group III, sizes >5 and ≤7 cm; group IV, tumor size >7 and ≤10 cm; and group V, tumor size >10 cm. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Board of Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Informed consent was waived for this retrospective study.

2.2. Definitions

We calculated the ALBI scores as follows: ALBI score = 0.66 × log10 (total bilirubin, μmol/L) – 0.085× (albumin, g/L). The following grading system was employed: grade I (≤−2.60); grade II (>−2.60 to ≤−1.39), and grade III (>−1.39).[6] The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) staging system consists of 4 variables: Child-Pugh grade, tumor morphology, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and portal vein thrombosis.[11]

2.3. Surgical methods

Indocyanine green test was carried out to assess liver function in hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus-infected individuals before the surgery. Preoperative remnant liver volume was mainly assessed by 3-dimensional reconstruction and virtual hepatic resection among patients who underwent a major hepatectomy as per the methods described previously.[12] Most of the patients received open hepatectomy through the right subcostal margin incision. However, a few selective patients (those with tumor size <5 cm positioned in segments 2–6 of the liver) underwent laparoscopic surgery. Intraoperative ultrasonography was conducted to confirm the relationship between tumors and vessels and locate the satellite nodules when necessary. After determining resectability, anatomical liver resection was the preferred option in the case of sufficient future remnant liver functional reserve. Hepatectomy extent was considered minor resection or major (involving 3/more Couinaud liver segments) and minor.[13]

2.4. Post-surgery follow-ups

Follow-up periods were 1 month after discharge and every 3 months for the next 2 years. During the follow-ups, routine tests on blood, AFP, imaging examinations, such as ultrasonography, contrast-enhanced computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging, and liver function tests were performed. In the case of recurrence, the patients were taken through repeated hepatic resection, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, ablation, or systemic therapies. These therapies were administered based on the hepatic function, tumor status, and economic status of the patient. The overall survival (OS) was measured beginning from the first diagnosis of HCC (admission date) until the last follow-up/death/January 2018.

2.5. Data analysis

Data involving continuous variables were assessed by the Mann–Whitney and U test and shown as interquartile range whereas discrete variables were analyzed by Chi-square. Kaplan–Meier plot was employed in the determination of OS. The log-rank test was employed to make comparisons of survival rates. The multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model was applied to identify independent prognostic factors for OS. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to measure the discriminatory power of the staging systems as predictors of survival. These analyses were conducted using SPSS v25.0. A P < .05 represented statistically significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. Clinicopathological features

Approximately 265 patients with HCC, including 231 males and 34 females (median age = 51 years; range: 21–77 years), were enrolled. A total of 60, 62, 46, 52, and 45 patients were classified in groups I, II, III, IV, and V, respectively. Those whose tumors were ≤7 cm presented a higher albumin level, a longer survival time, and a higher proportion of ALBI grade 2 HCC than those who had tumors that were >7 cm (P = .010, P < .001, and P = .036, respectively). However, patients who had tumor size ≤7 cm had a significantly low platelet count, a small tumor size, a short operative time, low blood loss, low rates of ALBI grade 1 HCC, AFP ≥400 ng/mL, major liver resection, and poor differentiation (P < .001, P < .001, P = .015, P < .001, P = .036, P = .003, P < .001, and P = .015, respectively). The baseline features of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 265 HCC patients.

| Variables | Total cohort (n = 265) | ≤7 cm subgroup (n = 168) | >7 cm subgroup (n = 97) | P value (≤7 cm vs >7 cm) |

| Age (years)∗ | 51 (43–60) | 52 (41–60) | 51 (44–60) | 0.825 |

| Male gender† | 231 (87.2%) | 147 (87.5%) | 84 (86.6%) | 0.832 |

| Positive HBsAg† | 228 (86.0%) | 143 (85.1%) | 85 (87.6%) | 0.570 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L)∗ | 13.4 (9.8–18.3) | 13.3 (9.9–19.3) | 13.5 (9.6–17.9) | 0.749 |

| Albumin (g/L)∗ | 38.4 (35.6–41.2) | 39.1 (36.4–41.4) | 37.9 (34.2–40.0) | 0.010 |

| ALBI grade† | 0.036 | |||

| 1 | 147 (55.5%) | 85 (50.6%) | 62 (63.9%) | |

| 2 | 118 (44.5%) | 83 (49.4%) | 35 (36.1%) | |

| Prothrombin time (s)∗ | 13.2 (12.2–14.4) | 13.2 (12.1–14.3) | 13.2 (12.3–14.4) | 0.934 |

| Platelet count (×109/L)∗ | 151 (106–210) | 135 (93–188) | 195 (136–246) | <0.001 |

| Maximum tumor size (cm)∗ | 6.0 (3.5–9.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.5) | 10.0 (8.0–14.0) | <0.001 |

| Serum AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL† | 90 (34.0%) | 46 (27.4%) | 44 (45.4%) | 0.003 |

| Operative time (min)∗ | 180 (140–210) | 170 (136–205) | 180 (155–223) | 0.015 |

| Blood loss (mL)∗ | 300 (100–500) | 200 (100–400) | 400 (200–1000) | <0.001 |

| Major hepatectomy† | 42 (15.8%) | 6 (3.6%) | 36 (37.1%) | <0.001 |

| Poor differentiation grade† | 80 (30.2%) | 42 (25.0%) | 38 (39.2%) | 0.015 |

| Survival time (mo)∗ | 43 (25–61) | 49 (37–62) | 26 (15–57) | <0.001 |

3.2. Survival

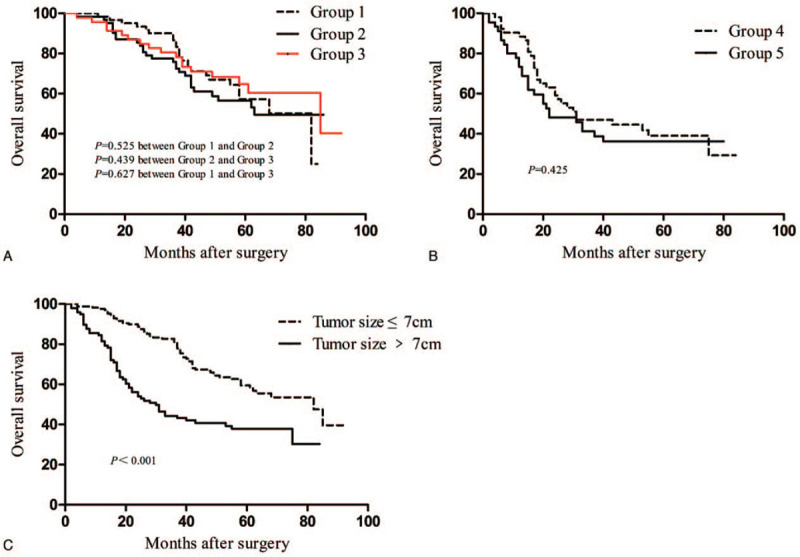

Up until the last follow-up day, 127 (47.9%) patients died. Among the 265 patients, the OS at 1 and 3 years reached 92.8% and 66.8%, respectively. No considerable differences in the OS were observed between groups I and II (P = .525), groups II and III (P = .439), and groups 1 and III (P = .627; Fig. 1A). A similar OS was noted between groups IV and V (P = .425; Fig. 1B). However, the OS among patients with tumor size ≤7 cm was considerably longer than those who had tumor size >7 cm (P < .001; Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Overall survival of patients with single tumor hepatocellular carcinoma (A) among groups I, II, and III; (B) between groups IV and V; and (C) between tumor size ≤7 cm and tumor size >7 cm subgroups.

3.3. Evaluation of OS by multivariate analysis

The Cox proportional hazards regression model assessment of the total cohort identified 3 indices as independent predictive factors for OS: ALBI grade (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.10; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.43–3.08; P < .001), maximum tumor size (HR: 1.72; 95% CI: 1.16–2.56; P = .007), and differentiation grade (HR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.01–2.15; P = .045; Table 2).

Table 2.

Prognostic factors for survival in the total cohort.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Variables | Hazard ratio | P value | Hazard ratio | P value |

| Age | 0.79 (0.51–1.23) | .298 | ||

| Gender | 1.33 (0.75–2.36) | .331 | ||

| Albumin-bilirubin grade | 2.28 (1.57–3.32) | <.001 | 2.10 (1.43–3.08) | <.001 |

| Prothrombin time | 1.46 (1.03–2.07) | .034 | 1.28 (0.90–1.83) | .169 |

| Platelet count | 1.31 (0.88–1.95) | .179 | ||

| Maximum tumor size | 2.08 (1.46–2.96) | <.001 | 1.72 (1.16–2.56) | .007 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein | 1.42 (0.99–2.03) | .054 | 1.16 (0.80–1.70) | .435 |

| Operation time | 1.51 (1.06–2.15) | .021 | 1.25 (0.86–1.83) | .240 |

| Blood loss | 1.55 (1.05–2.28) | .028 | 1.03 (0.67–1.58) | .891 |

| Major hepatectomy | 1.55 (0.99–2.42) | .054 | 0.95 (0.58–1.56) | .837 |

| Differentiation grade | 1.67 (1.17–2.40) | .005 | 1.47 (1.01–2.15) | .045 |

In the subgroup that had tumor size ≤7 cm, the independent predictive factors for OS included the ALBI grade (HR: 2.37; 95% CI: 1.39–4.05; P = .002) and platelet count (HR: 1.80; 95% CI: 1.07–3.05; P = .027). However, in the subgroup with tumor size >7 cm, the ALBI grade was not identified as a major determinant of OS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for survival divided by tumor size.

| ≤7 cm subgroup | >7 cm subgroup | |||

| Variables | Hazard ratio | P value | Hazard ratio | P value |

| Age | 0.81 (0.43–1.54) | .522 | 0.61 (0.29–1.29) | .194 |

| Gender | 1.33 (0.59–3.01) | .498 | 1.61 (0.65–3.96) | .302 |

| Albumin-bilirubin grade | 2.37 (1.39–4.05) | .002 | 1.74 (0.95–3.18) | .072 |

| Prothrombin time | 1.47 (0.89–2.44) | .133 | 0.93 (0.53–1.64) | .798 |

| Platelet count | 1.80 (1.07–3.05) | .027 | 1.12 (0.39–3.19) | .840 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein | 1.45 (0.81–2.61) | .213 | 0.97 (0.57–1.67) | .924 |

| Operation time | 1.10 (0.65–1.89) | .719 | 1.20 (0.68–2.12) | .533 |

| Blood loss | 1.21 (0.63–2.32) | .570 | 0.84 (0.47–1.49) | .548 |

| Differentiation grade | 1.67 (0.97–2.86) | .064 | 1.33 (0.77–2.31) | .311 |

3.4. Comparison of OS of patients with ALBI grades 1 and 2 HCC stratified by tumor size

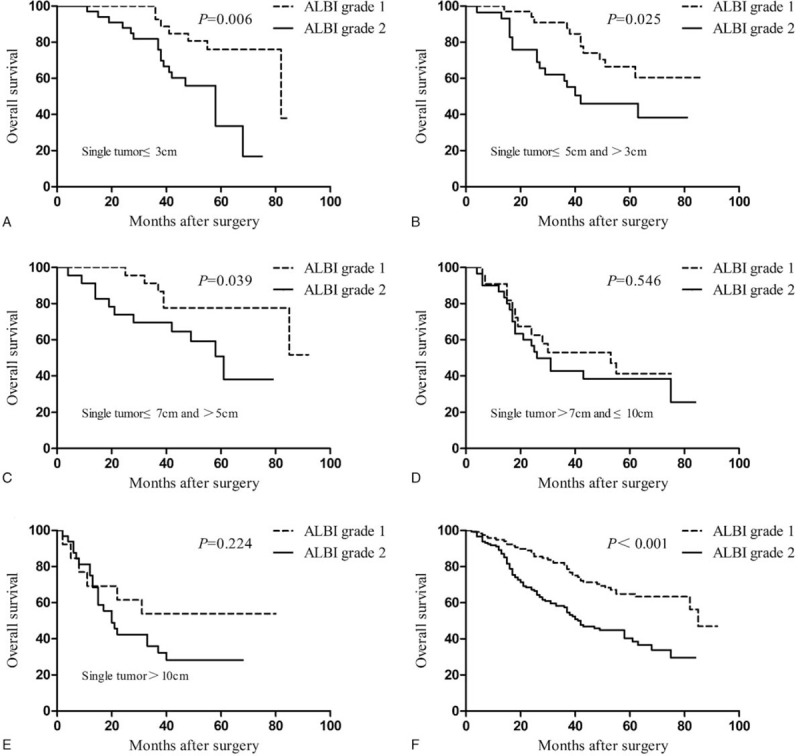

For the total cohort, we observed a remarkable difference in the OS between ALBI grades 1 and 2 patients (Fig. 2F). For groups I, II, and III, the ALBI grade 1 patients showed a significantly longer survival time relative to the ALBI grade 2 patients (P = .006, P = .025, and P = .039; Fig. 2A, B, and C, respectively). However, the OS was comparable between patients in ALBI grades 1 and 2 in groups IV and V (P = .546 and P = .224; Fig. 2D and E, respectively).

Figure 2.

Overall survival of patients with ALBI grades 1 and 2 (F) in the total cohort, (A) groups I, (B) II, (C) III, (D) IV, and (E) V. ALBI = albumin-bilirubin.

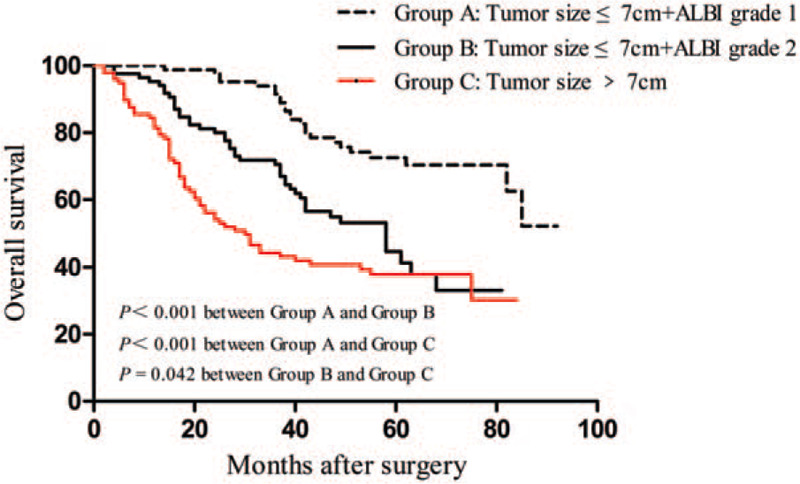

3.5. Comparison of patients’ OS in tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 1 vs tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 2 vs tumor size >7 cm subgroups

Given their importance in predicting OS, we further evaluated the effects of tumor size and ALBI grade on the prognosis of patients with HCC. With regard to tumor size and ALBI grade, considerable differences in the OS were observed among the 3 patient subgroups (Fig. 3). The tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 1 subgroup presented a remarkably higher OS compared with the tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 2 and tumor size >7 cm subgroups. The patients in the tumor size >7 cm subgroup exhibited the poorest OS among the 3 subgroups.

Figure 3.

Overall survival curves for patients stratified by ALBI grade and tumor size following hepatic resection. Significant differences were observed in patients between tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 1 and tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 2 subgroups (P < .001); patients in tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 1 and tumor size >7 cm subgroups (P < .001); and patients in tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 2 and tumor size >7 cm subgroups (P = .042). ALBI = albumin-bilirubin.

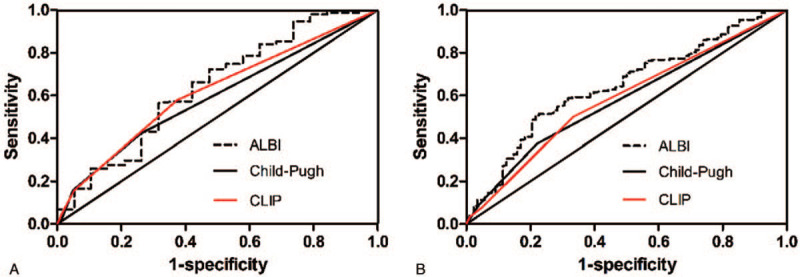

3.6. Discriminative ability of different scoring systems for patients’ survival

ROC curve analyses of ALBI score, Child-Pugh score, and CLIP score were performed to predict 1- and 3-year survival. The area under the ROC curve for ALBI score, Child-Pugh score, and CLIP score were 0.640 (P = .043), 0.590 (P = .191), and 0.617 (P = .090) in predicting 1-year survival (Fig. 4A), respectively, and 0.645 (P < .001), 0.580 (P = .034), and 0.584 (P = .025) in predicting 3-year survival (Fig. 4B), respectively.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of the area under the curve for (A) 1-year survival and (B) 3-year survival prediction among the ALBI, child-pugh, and CLIP systems using ROC curves. ALBI = albumin-bilirubin, CLIP = Cancer of the Liver Italian Program, ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

4. Discussion

Herein, the effectiveness of the ALBI grading system to predict the disease progress of HCC subjects with different tumor sizes was evaluated. We observed that a large tumor size (>7 cm) and a high ALBI grade are indicators of the poor clinical progress of patients with single HCC following surgery.

Tumor size has been regarded as one of the primary determinants of tumor recurrence and OS.[4,14] Huang et al identified tumor size as a major determinant of HCC patient prognosis, particularly among patients with solitary tumors without vascular invasion.[15] Another study also reported that tumor size is an independent prognostic factor of recurrence-free survival among patients with solitary HCC and who received curative liver resection.[16] However, other studies showed that large HCC does not conform to BCLC staging and treatment guidelines.[17,18] Among patients with HCC at the BCLC stage A, single tumors >5 cm showed a similar prognosis as patients with single tumors ≤5 cm.[19,20] In the present study, tumor size served as an independent predictor of OS for a single HCC without macrovascular invasion. Patients who had a tumor size >7 cm exhibited a significantly poorer OS than those who had a tumor size ≤7 cm. To further assess the effect of tumor size on long-term survival, we compared the OS in subgroups divided by the tumor size. No differences were noted in the OS of groups I, II, and III. Groups IV and V exhibited a similar OS. These findings indicate that patients with tumor size ≤7 cm or tumor size >7 cm may feature similar survival times. Therefore, patients who have a single tumor size >7 cm should not be ascribed to the same BCLC stage as those with a single tumor size ≤7 cm.

Several factors may explain why patients who had a single tumor ≤7 cm showed a remarkably better OS than those with tumor size >7 cm. We observed that patients whose tumors were >7 cm presented a lower albumin level, greater blood loss, and a higher proportion of serum AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL and poor differentiation than patients with tumor size ≤7 cm. AFP is regarded as an important prognostic indicator for HCC undergoing liver resection.[18,21] A high level of preoperative AFP often indicates poor survival time after surgery.[22] Tumor differentiation is positively correlated with the OS of patients with HCC after hepatectomy.[23] In our study, poor differentiation was found to be an independent OS predictor in multivariate analysis. The low histologic grade is correlated with a high risk of recurrence and low OS in patients with HCC following curative resection.[24]

The disease outcomes of patients with HCC post-liver resection are partly affected by the existing liver physiological status. For years, various prognostic staging systems for HCC have been proposed.[11] Our study showed that the ALBI score might have a better value in predicting 1- and 3-year survival than the Child-Pugh score and CLIP score. This finding is similar to the results of some previous studies.[6,25,26] The patients who had an ALBI grade 1 presented a better survival time than those who had an ALBI grade 2 in the total cohort. Additionally, we analyzed the ALBI grade in the different subgroups to further validate its value in predicting the prognoses of HCC. The OS rates were higher in ALBI grade 1 patients compared with those in ALBI grade 2 patients in groups I, II, and III. However, when the OS rates were analyzed in groups IV and V, no marked differences were found between the subjects with ALBI grades 1 and 2. Multivariate analysis identified the lack of predictive capability of ALBI grade for the tumor size >7 cm subgroup. Therefore, ALBI grade could predict the prognosis of patients with HCC and a small single tumor. However, ALBI grade alone might be insufficient in determining the prognosis of patients with HCC and single tumor >7 cm. For large HCC, tumor burden could have a more significant function in determining the OS compared with liver function. Microvascular invasion (MVI) is a critical risk factor for HCC prognosis.[27–29] Previous studies demonstrated that the incidence of MVI increased with tumor size.[30] In solitary HCC, the incidence of MVI progressively increased from 4.1% to 30.7% as the tumor size increases from <2 cm to 8.1–9.9 cm, to 12.8% in tumor size ≤5 cm, and to 27.7% in tumor size measuring 5.1 to 9.9 cm.[4] Therefore, MVI might play a more crucial function in determining the prognosis compared with liver function for large single tumors.

Theoretically, the combination of tumor size and liver function could effectively predict the prognosis of HCC following hepatic resection. We integrated tumor size and ALBI grade, to generate an accurate model for determining the prognosis of patients with a single tumor. The results showed that patients in the tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 1 subgroup presented a remarkably higher OS rate than those in the tumor size ≤7 cm + ALBI grade 2 and tumor size >7 cm subgroups. Patients in the single tumor >7 cm subgroup achieved the poorest OS among the 3 subgroups. Thus, the prognosis of a single small tumor might be remarkably affected by liver function, whereas tumor burden could play a leading role in the prognosis of single large tumors. In clinical practice, patients having a single tumor >7 cm and who are undergoing liver resection may likely suffer from relapse. Thus, additional postoperative treatments may be necessary for these patients.

This study features several limitations. First, the conclusions are based on the retrospective analysis of data from a single liver center and weakened by small sample size, so selective bias may exist. Multicenter prospective research is required to verify and extend the results of the present study. In addition, our study did not assess the influence of ALBI grade on disease-free survival. Lastly, we did not evaluate the role of microvascular invasion in relation to ALBI grade, which we hope to do in the future.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, ALBI grade is valuable in determining the prognosis of patients with a single HCC with tumor size ≤7 cm. However, the ALBI grade shows no predictive capability among patients with a single tumor >7 cm. Patients with a single tumor >7 cm may constitute an independent group distinct from the classic BCLC stage A.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Fanhua Kong, Heng Zou; Data collection: Wenhao Chen, Zijian Zhang; Formal analysis: Jiangjiao Zhou, Li Xiong, Xianrui Fang. Methodology: Heng Zou, Yu Wen. Supervision: Heng Zou. Writing-original draft: Wenhao Chen, Zijian Zhang, Fanhua Kong. Writing-review and editing: Xianrui Fang, Heng Zou, Fanhua Kong.

Conceptualization: Fanhua Kong, Heng Zou.

Data curation: Wenhao Chen, Zijian Zhang.

Formal analysis: Xianrui Fang, Li Xiong, Jiangjiao Zhou.

Methodology: Yu Wen.

Supervision: Yu Wen.

Writing – original draft: Wenhao Chen, Zijian Zhang, Fanhua Kong.

Writing – review & editing: Wenhao Chen, Xianrui Fang, Fanhua Kong, Heng Zou.

Correction

When originally published, the affiliation for Zijian Zhang, Li Xiong, Yu Wen, Jiangjiao Zhou, Fanhua Kong, and Heng Zou was mistakenly removed. It has been added as affiliation b, and the original affiliation b has been updated to c. The indicators on the author list have been updated accordingly.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AFP = alpha-fetoprotein, ALBI = albumin-bilirubin, BCLC = Barcelona Clinic for Liver Cancer, CLIP = Cancer of the Liver Italian Program, HBV = hepatitis B virus, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, MVI = microvascular invasion, OS = overall survival, ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

How to cite this article: Chen W, Zhang Z, Fang X, Xiong L, Wen Y, Zhou J, Kong F, Zou H. Prognostic value of the ALBI grade among patients with single hepatocellular carcinoma without macrovascular invasion. Medicine. 2021;100:24(e26265).

WC and ZZ contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the Big Data Project of Xiangya Medical School, Central South University, and the Research Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (No. B20180130).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

AFP = α-fetoprotein, ALBI = albumin-bilirubin, HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma.

Values are median (interquartile range).

Values are number (%).

References

- [1].Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2016;150:835–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Vitale A, Burra P, Frigo AC, et al. Survival benefit of liver resection for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across different Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages: a multicentre study. J Hepatol 2015;62:617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].European Association for the Study of the Liver; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hwang S, Lee YJ, Kim KH, et al. The impact of tumor size on long-term survival outcomes after resection of solitary hepatocellular carcinoma: single-institution experience with 2558 patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:1281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zheng YW, Wang KP, Zhou JJ, et al. Portal hypertension predicts short-term and long-term outcomes after hepatectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 2018;53:1562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kuo YH, Wang JH, Hung CH, et al. Albumin-Bilirubin grade predicts prognosis of HCC patients with sorafenib use. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;32:1975–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dong ZR, Zou J, Sun D, et al. Preoperative albumin-bilirubin score for postoperative solitary hepatocellular carcinoma within the milan criteria and child-pugh A cirrhosis. J Cancer 2017;8:3862–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Oh IS, Sinn DH, Kang TW, et al. Liver function assessment using albumin-bilirubin grade for patients with very early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radiofrequency ablation. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:3235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pinato DJ, Sharma R, Allara E, et al. The ALBI grade provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each BCLC stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017;66:338–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tellapuri S, Sutphin PD, Beg MS, Singal AG, Kalva SP. Staging systems of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. Indian J Gastroenterol 2018;37:481–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zou H, Wen Y, Yuan K, et al. Combining albumin-bilirubin score with future liver remnant predicts post-hepatectomy liver failure in HBV-associated HCC patients. Liver Int 2018;38:494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mullen JT, Ribero D, Reddy SK, et al. Hepatic insufficiency and mortality in 1,059 noncirrhotic patients undergoing major hepatectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:854–62. discussion 62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Prognostic indicators in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of 72 studies. Liver Int 2009;29:502–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Huang WJ, Jeng YM, Lai HS, Sheu FY, Lai PL, Yuan RH. Tumor size is a major determinant of prognosis of resected stage I hepatocellular carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2015;400:725–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Goh BK, Teo JY, Chan CY, et al. Importance of tumor size as a prognostic factor after partial liver resection for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma: implications on the current AJCC staging system. J Surg Oncol 2016;113:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Torzilli G, Belghiti J, Kokudo N, et al. A snapshot of the effective indications and results of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in tertiary referral centers: is it adherent to the EASL/AASLD recommendations?: an observational study of the HCC East-West study group. Ann Surg 2013;257:929–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhong JH, Pan LH, Wang YY, et al. Optimizing stage of single large hepatocellular carcinoma: a study with subgroup analysis by tumor diameter. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yang LY, Fang F, Ou DP, Wu W, Zeng ZJ, Wu F. Solitary large hepatocellular carcinoma: a specific subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma with good outcome after hepatic resection. Ann Surg 2009;249:118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cho YB, Lee KU, Lee HW, et al. Outcomes of hepatic resection for a single large hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg 2007;31:795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fang KC, Kao WY, Su CW, et al. The prognosis of single large hepatocellular carcinoma was distinct from Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer Stage A or B: the role of albumin-bilirubin grade. Liver Cancer 2018;7:335–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chan MY, She WH, Dai WC, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level in patients receiving curative hepatectomy – an analysis of 1,182 patients in Hong Kong. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shen J, Liu J, Li C, Wen T, Yan L, Yang J. The impact of tumor differentiation on the prognosis of HBV-associated solitary hepatocellular carcinoma following hepatectomy: a propensity score matching analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2018;63:1962–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Han DH, Choi GH, Kim KS, et al. Prognostic significance of the worst grade in hepatocellular carcinoma with heterogeneous histologic grades of differentiation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28:1384–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shao YY, Liu TH, Lee Y, Hsu CH, Cheng AL. Modified CLIP with objective liver reserve assessment retains prognosis prediction for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;31:1336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhao S, Wang M, Yang Z, et al. Comparison between Child-Pugh score and Albumin-Bilirubin grade in the prognosis of patients with HCC after liver resection using time-dependent ROC. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shen J, Wen J, Li C, et al. The prognostic value of microvascular invasion in early-intermediate stage hepatocelluar carcinoma: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Cancer 2018;18:278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Han J, Li ZL, Xing H, et al. The impact of resection margin and microvascular invasion on long-term prognosis after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a multi-institutional study. HPB (Oxford) 2019;21:962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang XP, Wang K, Wei XB, et al. An eastern hepatobiliary surgery hospital microvascular invasion scoring system in predicting prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and microvascular invasion after R0 liver resection: a large-scale, multicenter study. Oncologist 2019;24:e1476–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, et al. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2005;11:1086–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]