Abstract

Background:

To assess prevalence and predictive factors for Nosocomial Infection (NI) in the military hospitals.

Methods:

PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane and PreQuest databases were systematically searched for studies published between Jan 1991 and Oct 2017 that reported the prevalence of NI and predictive factors among military hospitals. We performed the meta-analysis using a random effects model. Subgroup analysis was done for heterogeneity and the Egger test to funnel plots was used to assess publication bias.

Results:

Twenty-eight studies with 250,374 patients were evaluated in meta-analysis. The overall pooled estimate of the prevalence of NI was 8% (95% 6.0–9.0). The pooled prevalence was 2% (95% CI: 2.0–3.0) when we did sensitivity analysis and excluding a study. The prevalence was highest in burn unit (32%) and ICU (15%). Reported risk factors for NI included gender (male vs female, OR: 1.45), age (Age≥65, OR: 2.4), diabetes mellitus (OR: 2.32), inappropriate use of antibiotics (OR: 2.35), received mechanical support (OR: 2.81), co-morbidities (OR: 2.97), admitted into the ICU (OR: 2.26), smoking (OR: 1.36) and BMI (OR: 1.09).

Conclusion:

The review revealed a difference of prevalence in military hospitals with other hospitals and shows a high prevalence of NI in burn units. Therefore careful disinfection and strict procedures of infection control are necessary in places that serve immunosuppressed individuals such as burn patient. Moreover, a vision for the improvement of reports and studies in military hospitals to report the rate of these infections are necessary.

Keywords: Nosocomial infection, Military hospital, Predictive factors

Introduction

Nosocomial infections (NI) are straightly related to hospitalization of patients and considered a critical menace to patients’ health (1, 2). About 8.7% of hospitalized patients worldwide develop it (3, 4). This phenomenon increases the cost of health services and reduces access to hospital care due to the prolongation of treatment and, on the other hand, causes mental and psychological problems for the patient and their families (2). Despite many efforts to control NIs, are estimated that these infections to be responsible for about 80,000 deaths in the US every year (5).

Military hospitals not only have a critical role in providing medical services to special patients such as militaries and their families, heads of state and governors but also play an important role in crisis management. Therefore, the people’s and authority’s expectance from military hospitals is high-quality and safe care production. Moreover, the most common features among the patients are lower extremity amputation and receipt of massive blood transfusions following blast injuries incurred, in essence, the war affected the workload and productivity of military. This profile is consistent with a previous American military report while on foot patrol in southern Afghanistan or British military report in the “green zone” of Helmand province in Afghanistan (6, 7). Various Meta-analyze of NI have been carried out among developing and developed countries and between different types of infections and risk factors (2, 8, 9), while no a comprehensive study on hospital infections among military hospitals has not been done on the prevalence of infections. Considering different of military hospitals management with non-military hospitals and in different countries, therefore it implies that the different results can be expected.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess prevalence and predictive factors for NI in the military hospitals.

Methods

Search strategy

We expected to identify studies on the prevalence of NI in military hospitals. We investigated Pub-Med, Scopus, Cochrane and PreQuest for articles published between Jan 1991, and Oct, 2017, with language restriction. We utilized a general list of terms ((Cross infection*”[mesh], “nosocomial infection*”, “hospital infection”, “healthcare-associated infection*”, “healthcare associated infection*”, “healthcare-acquired infection*”, “hospital acquired infection*”, “nosocomial bacteraemia”, “device-associated infection*”, “device associated infection*”, “bloodstream infection*”, “noso- comial septicaemia”, “urinary tract infection*”[mesh], “surgical site infection*”, “wound infection*”[mesh], “wound infection*”, “hospital-acquired pneumonia”, “hospital acquired pneumonia”, “nosocomial pneumonia”, “hospital pneumonia”,”ventilator-associated pneumonia”, “ventilator associated pneumonia”) AND (navy, “air force”, “armed forces”, military, army, “marine corps”, “coast guard”)).

To exclude studies which did not meet the research question of interest, the titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two authors. The full text of the remaining studies was examined in more detail to determine whether it contained relevant information. References of all assessed articles also were screened for additional eligible publications.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted by two investigators independently with disagreement resolved by consensus. Extracted data included: authors; year(s) conducted; year of publication; country where the study was done; study methods; number of hospitals studied; type of infection including most frequent infections; study methods; total number of subjects recruited; number of subjects with; risk factors of NI.

We evaluated the methodological quality of the articles using a checklist (Quality assessment checklist for prevalence studies) adapted from Hoy et al (10). The checklist consists of nine questions that assesses the representativeness of sample, sampling technique, response rate, data collection method, measurement tools, case definitions, and statistical reporting. Each checked question was scored either as “1” or “0”. The total score ranged from 0 to 9 with the overall score categorised as follows: 7 to 9: “low risk of bias”, 4 to 6: “moderate risk”, and 0 to 3: “high risk”.

Statistical analysis

We used StataCorp version 14.2 to calculate pooled prevalence of NI and subgroups analysis in various variables was also performed. Predictive factors for NIs were estimated through estimating pooled ORs and 95% CIs. The predictive factors were considered significantly associated with NI when P<0.05 and 95% CI did not span 1. The I2 statistic with a cutoff of 50% (11) was used to determine Heterogeneity between studies. Random-effects model was done for pooled effect size for I2> 50%, a fixed-effects model was implemented in low degree of heterogeneity. Also the StataCorp was utilized to generate Forest plots of pooled prevalences. In this study Egger’s test to funnel plots was applied to check the evidence of publication bias and subgroup analysis was done for heterogeneity. To assess the dependency of overall estimate on a single study sensitivity analysis was done.

Results

Study selection

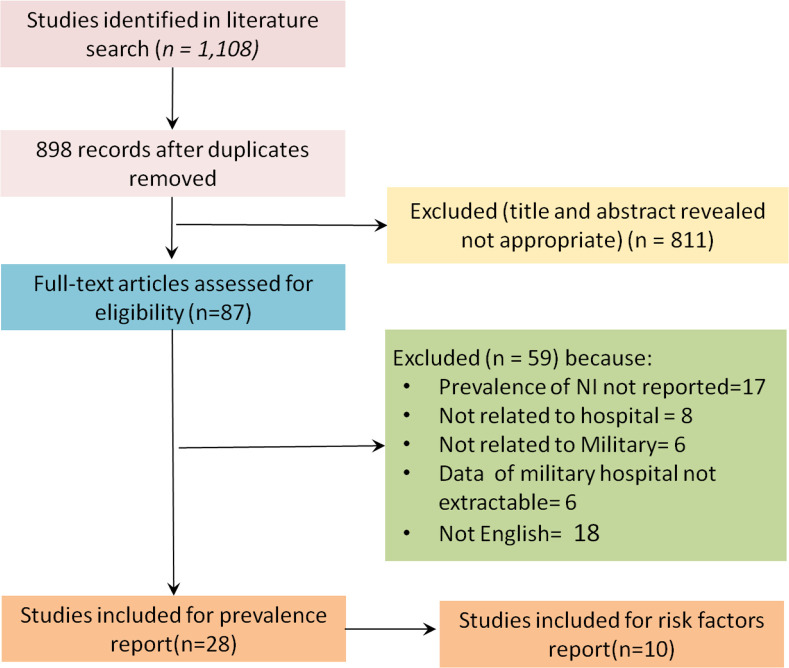

The search identified 87 from 1108 studies were included by excluding duplicate articles (n=210), and scanning titles and abstracts that met the requirements for inclusion in the Meta analysis. Then 59 studies excluded because of prevalence of NI not reported (n=17), not related to hospital (n=8), not related to Military (n=6), data of military hospital not extractable (n=6), and 18 article that were not in English by full-text screening. Overall, 28 articles were selected for prevalence and finally, of 28 included studies, 10 studies identified for risk factor of NI (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

Flow diagram for selection of articles

Characteristics of enrolled articles

The selected information about included articles are shown in Table 1. Twenty-eight studies with 250,374 patients (range from 63–56,644 per study) were evaluated in this meta-analysis.

Table 1:

Characteristics of selected studies

| No | Authors (year of survey) | Country | Method | Sample Size | No. Of Hospital | Risk Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dawn (2002 to 2007) | USA | Retrospective | 75 | One | Moderate Risk |

| 2 | Lesperance (2006 to 2007) | USA | Prospective | 245 | One | Low risk |

| 3 | Chen (2014–2015) | China | Cross sectional | 53,939 | Fifty-two | Low risk |

| 4 | Oncul (2000) | Turkey | Prospective | 63 | One | Moderate Risk |

| 5 | Jonathan (2009–2014) | USA | Retrospective | 6,535 | One | Low risk |

| 6 | Zeng (2010–2015) | China | Randomized, controlled multicenter trial | 235 | Nine | Low risk |

| 7 | Starčević (2007–2010) | Serbia | Prospective | 3,867 | One | Low risk |

| 8 | Al-Asmary (2001–2003) | Saudi Arabia | Case-control | 54,926 | Three | Low risk |

| 9 | Edward (1991–2002) | USA | Retrospective | 2651 | One | Low risk |

| 10 | Becker (1979–1989) | USA | Retrospective | 2,114 | One | Low risk |

| 11 | Kepler (2002) | USA | Prospective | 758 | One | Low risk |

| 12 | Warkentien (2009–2010) | Germany-USA | Cross sectional | 2413 | Two | Low risk |

| 13 | ABDEL-FATTAH (1999–2003) | Saudi Arabia | Case-control | 56,644 | Three | Moderate Risk |

| 14 | Al-Helali (2001–2003) | Saudi Arabia | Case-control | 54,926 | Three | Moderate Risk |

| 15 | Whitford (2006–2007) | Bahrain | Cross-sectional | 458 | One | Low risk |

| 16 | Hajjej (2012) | Tunisia | Prospective | 260 | One | Low risk |

| 17 | Singh (2012) | India | Hospital-based observational | 88 | One | Low risk |

| 18 | Singh (2009–2010) | India | Hospital-based observational | 204 | One | Low risk |

| 19 | Karacae (2009–2010) | Turkey | Prospective | 2,362 | One | Low risk |

| 20 | JIANG (2008–2013) | China | Prospective | 3042 | One | Low risk |

| 21 | Suljagic (2000) | Serbia | Prospective | 4,711 | One | Moderate Risk |

| 22 | Oncul (2001–2012) | Turkey | Prospective | 658 | One | Low risk |

| 23 | Liu (2010–2013) | China | Prospective | 1,922 | One | Low risk |

| 24 | Xiao (2010–2013) | China | Retrospective | 16,263 | Seven | Low risk |

| 25 | SULJAGIC′ (2006) | Serbia | Prospective | 5,088 | One | Low risk |

| 26 | Mladenović (2006–2011) | Serbia | Case control | 1,369 | One | Low risk |

| 27 | Schaal (2000–2011) | French | Retrospective | 1849 | One | Low risk |

| 28 | Oncul (2004–2005) | Turkiye | Retrospective | 169 | One | Low risk |

Overall prevalence

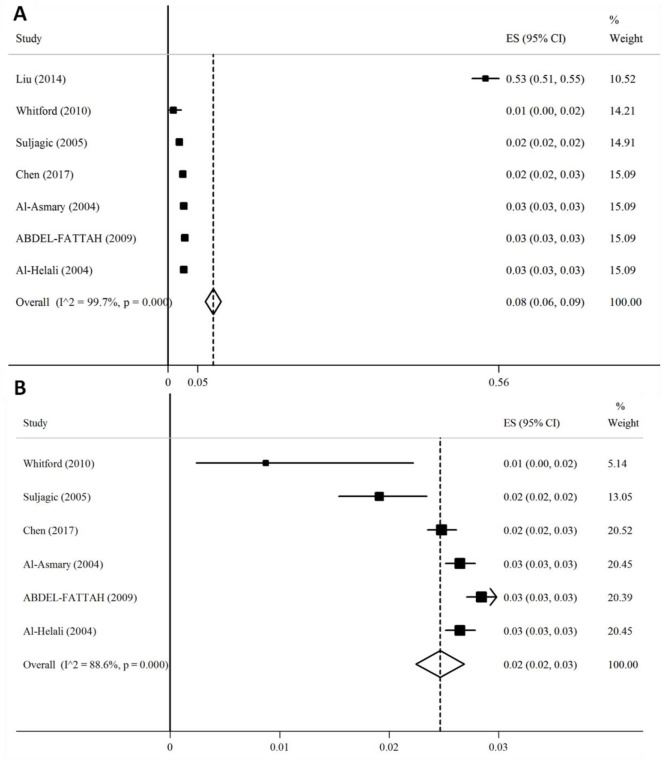

After combining 7 prevalence from seven studies (12–18) with total population of 227,526, we found that 8% (95% 6.0–9.0) of participants were effected (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2:

Forest plot for the overall estimate of the prevalence of NI. (A) Before sensitivity analysis and (B) After sensitivity analysis. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size

In addition, overall prevalence depended on study done by Liu when we did sensitivity analysis. After excluding mentioned study, the prevalence becomes 2% (95% CI: 2.0–3.0) (Fig. 2). Potential sources of heterogeneity (I2= 99.7%, P<0.001) by random effects multivariate and univariate meta-regression were conducted with several assessed covariates, including geographical location, year of survey, sample size, number of hospital, study method, and quality score of bias risk. All of them may be the sources of heterogeneity. No publication bias was found according to the results of Egger’s test (P>0.05) and no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry was seen.

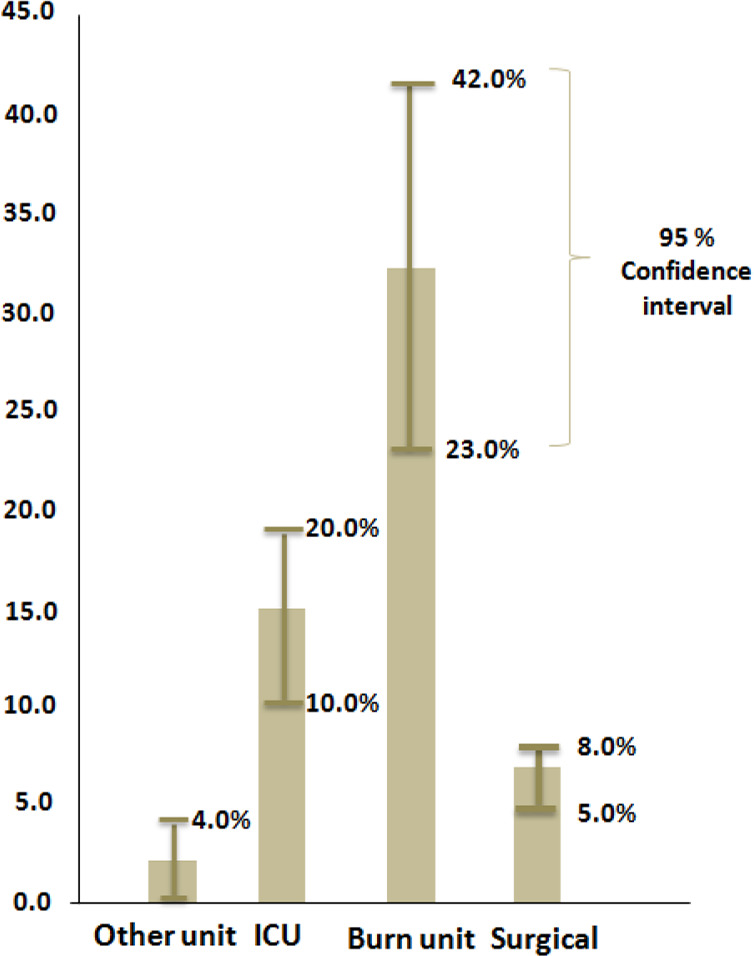

Prevalence in different hospital wards

Ten studies (13, 14, 19–26) reported NI in surgical ward with total population of 54,489. The pooled prevalence was 7% (95% CI: 5.0–8.0) with statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (I2=98.8%, P<0.001), but no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry or other small study effects (Egger test, P=0.03).

The NIs prevalence in other wards including; burn unit with six studies (27–32), ICU with ten studies (15, 17, 18, 20, 33–38) and other ward (including internal wards, gynecology, obstetrics, pediatrics, otorhinolaryngology, dentistry and ophthalmology) with three studies (7, 13, 14) were 32% (95% CI: 23.0–42.0), 15% (95% CI: 10.0–20.0) and 2% (95% CI: 0.0–4.0) respectively. Comparing the pooled prevalence showed in Figure 3. The prevalence was highest in burn unit, however, between studies heterogeneity was seen (I2> 50%, P<0.001). We found publication bias in studies that conducted in burn unit and ICU according to the results of Egger’s test (P>0.05) and no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry was seen.

Fig. 3:

Comparing prevalence of NI in different hospital wards

Predictive factors of NI

Of 28 included studies, 10 studies (14, 15, 18, 20, 21, 24, 28, 29, 36, 37) investigated risk factor for NI. 9 NI related risk factors were analyzed in this study, including Gender, Age, Diabetes Mellitus, inappropriate use of Antibiotics, received Mechanical Support, Comorbidities, Admitted into the ICU, Smoking and BMI. All pooled data about these factors were shown in table 2.

Table 2:

Pooled data about nosocomial infection related risk factors

| Risk factors | Fixed / Random Model | Number of studies | OR | 95 % Confidence interval | I2 (%) | P value for I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male vs female) | Random | 3 | 1.45 | 0.85 – 2.49 | 94.9 | < 0.001 |

| Age≥65 | Random | 3 | 2.04 | 1.29 – 3.22 | 81.5 | 0.004 |

| Diabetes mellitus | Random | 6 | 2.32 | 1.54 – 3.51 | 77.2 | 0.002 |

| Inappropriate use of antibiotics | Random | 3 | 2.35 | 1.34 – 4.12 | 48.7 | 0.142 |

| Received mechanical support | Random | 6 | 2.81 | 1.38 – 5.71 | 92.2 | < 0.001 |

| Co-morbidities | Fixed | 3 | 2.97 | 2.14 – 4.11 | <50 | 0.538 |

| Admitted into the ICU | Random | 3 | 2.26 | 1.42 – 3.60 | 77.0 | 0.013 |

| Smoking | Random | 3 | 1.36 | 0.70 – 2.64 | 90.3 | < 0.001 |

| BMI | Random | 3 | 1.09 | 0.99–1.94 | 89.8 | < 0.001 |

Gender: Combining 3 effect sizes from 3 studies (14, 15, 20) showed that male had greater risk of NI than female (OR=1.45, 95% CI: 0.85–2.49).

Age: A few studies (14, 15, 28) suggested that the risk of NI was significantly associated with age.

Our pooled data shown that patients 65 yr old and older had higher risk of NI (odds ratio: 2.04, 95% CI: 1.29 – 3.22).

Diabetes mellitus: The combined data in 6 articles (15, 18, 20, 21, 24, 36)were reported that patients with diabetes mellitus were 2.32 times (95% CI: 1.54 – 3.51) more at risk of being NI.

Inappropriate use of antibiotics: Combining 3 effect sizes from 3 studies (15, 29, 36) were reported that inappropriate use of antibiotics increased the risk of NI 2.35 times (95% CI: 1.34 – 4.12) more likely.

Received mechanical support: The pooled data from 6 studies (14, 15, 21, 29, 36, 37) showed that patients receiving mechanical support are at risk for NI (odds ratio: 2.81, 95% CI: 1.38 – 5.71). Co-morbidities: Three studies (15, 29, 37) identified co-morbidities as a potential risk factor for NI. Our pooled data shown that this factor increased chance of NI three time (odds ratio: 2.97, 95% CI: 2.14–4.11) more.

Admitted into the ICU: The pooled data from 3 studies (14, 15, 18) showed that patients admit to ICU are at high risk for NI (odds ratio: 2.26, 95% CI: 1.42 – 3.60).

Other factors: Smoking (15, 20, 21) BMI (20, 21, 24) were respectively reported in 3 enrolled studies. The results painted that these NI linked to risk factors that mentioned above, can increase risk of NI.

Discussion

The first systematic review and meta-analysis of studies performed to examining global prevalence of NI and predictive factors of NI among military hospitals. Information of more than 250 thousands patients is extracted and pooled by meta-analysis. It was strengthened by our precise methodology in data extraction and data pooled through Metaprop and Metan packages. Use of a random effects model according to the method (39) to collect data, a more conservative estimate of NI prevalence is provided and sensitivity analysis and publication bias were assessed at each stage. We were careful in each study to use only general patient data which were representative of the hospitalized patients to generalization of our results.

The overall prevalence was shown a very low prevalence of 2% and represents a minor burden on military hospitals, with an even smaller epidemiological relevance than in developed countries (40, 41). Pooled prevalence was showed in developing countries were 10.6% (CI: 8.1–13.9) which was substantially higher than the pooled prevalence in military hospitals (2). Similarly, the pooled prevalence in this meta-analysis is lower than the pooled prevalence (7.1%) in Europe (42) and USA (4.5 per 100 patients) (43). Various reasons, such as the sampling procedures, infection prevention protocols, during the study period, may have caused these varieties due to difference local conditions (44). In particular, regarding military hospitals, limiting access to patients’ confidential information will also affect the results of studies. As well as one of the important factors was accessibility and use of a microbiology laboratory (27). However, this fact had an influence on report of the rate and prognosis of NI. Therefore, the hospital management can play an important role in report of NIs prevalence. Even the different of results among countries implies that the different management styles of military hospitals in different countries.

The difference between our meta-analysis and mentioned studies is even more striking, when considering prevalence of ward-acquired infection with rates higher among patients admitted to burn units. In our review, pooled densities of infection in burn patients with prevalence of 32% compare to other patients were two to sixteen times higher than ICU (15%), surgical (7%) and other wards (2%). Since the burn wound is highly susceptible to colonization with all species of microorganisms, colonized microorganisms can be easily multiplied to achieve a high density on the wound. Therefore, large areas of open wounds make burn patients susceptible to infectious diseases. Moreover, the use of ventilator, blood and urine catheter, especially for people with severe burns, increases the basis for bacterial colonization and infection, on the other hand the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics also causes the loss of normal fluorine of patients and make them susceptible to invasion by pathogen bacteria. Therefore, in this study the rate of hospital infection among these patients were observed more (45, 46). However, studies showed the prevalence was highest in ICUs, followed by surgery, etc. (47–49).

Substantially proportion of infection in military hospitals and others are different. In military hospitals high rates of NIs were seen in patients of burn unit. Thus, another factor contributing to the difference in the prevalence of kinds of infections among military hospitals with other hospitals was the difference in the combination of persons referring to military hospitals. These persons are mostly soldiers and survivors of war with their families, which seems to have different requirements than those who come to other hospitals.

What are the important predictive factors of NI among military hospitals? The results identified several risk factors associated with NI in the pooled studies. Studies performed on military hospitals have suggested that obesity is associated with an increased risk of infection in these hospitals. Similarly a meta-analysis confirmed that obesity increases SSIs about twofold (50). Newell established a relationship between obesity and increased risk of UTIs (51). Despite these findings, in some studies there was no association between BMI and NI (20, 52). Moreover, in present study showed BMI had less effect on NI. Additional research is necessary to find out the relationship between obesity and increased NI rates.

The current analysis of risk factors identified the factors of smoking, male and age as independently associated with an increased risk of NI. However Suljagic did not support the relationship between smoking and its risk for SSI in a military hospital (20), Watanabe showed that a preoperative smoking habit is a significant risk factor for SSI (53). Previous studies dealing with smoking and its risk for NI in military hospitals are difficult to interpret, because the definition of smoking was not standardized or active smokers was not clearly defined. About sex and age different studies conducted and indicated that the relationship between this factors and the rate of NI varied related to the underlying acute reason for hospitalization (54, 55).

Our pooled data shown that diabetes mellitus and other co-morbidities were the factors most strongly associated with NIs. Patients with diabetes mellitus are considered to be immunocompromised and therefore more susceptible to NI (56)). Diabetes mellitus was reported to be a risk factor for development of NI in many studies (57, 58). Contrary to the current studies, some studies showed that diabetes mellitus was not a risk factor for development of NI (59, 60). Perhaps further research is needed to help determine the impact of diabetes mellitus on the incidence of NI. Other co-morbidity such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurological diseases, solid tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, prostate hypertrophy, atherosclerosis are the disease have been implicated as predisposing factors for infection (61). This type of diseases such as diabetes mellitus, impair leukocyte functions and increased the risk of NI. Chronic diseases in study by Erika were at a substantially greater risk (with a 3.6-fold increased risk) for developing a NI compared with other hospitalized patients (62) that exactly are in agreement with present study.

In addition to above mentioned factors, risk factors of received mechanical support, inappropriate use of antibiotics and admitted into the ICU were strong predictors for NI conformed in many studies. For instance a study indicated received mechanical support is the most important factors in infection’s speed. VAP is seen in 10 to 20% of patients receiving mechanical ventilatory support (63). Totally, there was no difference between military hospitals and other hospitals regarding predictors of NIs, and all the identified risk factors in previous studies also were observed in other hospitals.

This study had some limitations include countries study (most of these countries were part of the Middle East) and even finding accuracy which they can affect on the results of NIs in military hospitals.

Conclusion

In military hospitals the general infections of hospital were reported to be less than common. Of course, one of the study limitations should be mentioned that most of these countries were part of the Middle East and it is likely that the diagnosis of NIs and their use in future decisions of the organization are not priorities of military hospital or these countries do not have advanced knowledge and tools to identify the infectious agents, therefore, less hospital infections is reported. The rate of infection in the burn unit was significantly higher than other units. Maybe, heavy workload, health workforce shortage, lock of access to desirable hygiene products and skin irritation by hand hygiene products in military hospital have been the major reasons for the rate of infection in the burn unit. Considering that the predictors of NIs detected in military hospitals are common in other studies. To reduce the risk of NIs, the available protocols be used, focusing on these risk factors.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Baqiyatallah University of Medical sciences. The ethical committee approved this research (no = s/340/5/6616, October 24, 2017).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Chen Y, Shan X, Zhao J, et al. (2017). Predicting nosocomial lower respiratory tract infections by a risk index based system. Sci Rep, 7(1): 15933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allegranzi B, Nejad SB, Combescure C, et al. (2011). Burden of endemic healthcare-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 377(9761): 228–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pashman J, Bradley E, Wang H, et al. (2007). Promotion of hand hygiene techniques through use of a surveillance tool. J Hosp Infect, 66(3): 249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansour MGE, Bendary S. (2012). Hospital-acquired pneumonia in critically ill children: Incidence, risk factors, outcome and diagnosis with insight on the novel diagnostic technique of multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Egypt J Med Hum Genet, 13(1): 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B. (2000). Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA, 284(4): 483–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evriviades D, Jeffery S, Cubison T, et al. (2011). Shaping the military wound: issues surrounding the reconstruction of injured servicemen at the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 366(1562): 219–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warkentien T, Rodriguez C, Lloyd B, et al. (2012). Invasive mold infections following combat-related injuries. Clin Infect Dis, 55(11): 1441–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan T, Liu C, Li Y, et al. (2018). Prevalence and predictive factors of urinary tract infection among patients with stroke: A meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control, 46(4): 402–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez-Acelas AL, de Abreu Almeida M, Engelman B, Cañon-Montañez W. (2017). Risk factors for health care–associated infection in hospitalized adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control, 45(12): e149–e156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. (2012). Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol, 65(9): 934–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327(7414): 557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, Zhao J, Xing Y, et al. (2014). Nosocomial infection in adult admissions with hematological malignancies originating from different lineages: a prospective observational study. PLoS One, 9(11): e113506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitford DL, Ofurum KA. (2010). HealthCare Associated Infection Rates among Adult Patients in Bahrain Military Hospital: A Cross Sectional Survey. Bahrain Med Bull, 32(1):11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y, Zhao J, Shan X, et al. (2017). A point-prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infection in fifty-two Chinese hospitals. J Hosp Infect, 95(1): 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdel Fattah M. (2008). Nosocomial pneumonia: risk factors, rates and trends. 83–90. East Mediterr Health J,14(3): 546–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Šuljagiæ V, Èobeljiæ M, Jankoviæ S, et al. (2005). Nosocomial bloodstream infections in ICU and non-ICU patients. Am J Infect Control, 33(6): 333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Helali NS, Al-Asmary SM, Abdel-Fattah MM, et al. (2004). Epidemiologic study of nosocomial urinary tract infections in Saudi military hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 25(11): 1004–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Asmary SM, Al-Helali NS, Abdel-Fattah MM, et al. (2004). Nosocomial urinary tract infection. Risk factors, rates and trends. Saudi Med J, 25(7): 895–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesperance R, Lehman R, Lesperance K, et al. (2011). Early postoperative fever and the “routine” fever work-up: results of a prospective study. J Surg Res, 171(1): 245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suljagiæ V, Jevtic M, Djordjevic B, Jovelic A. (2010). Surgical site infections in a tertiary health care center: prospective cohort study. Surg Today, 40(8): 763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starèeviæ S, Munitlak S, Mijoviæ B, et al. (2015). Surgical site infection surveillance in orthopedic patients in the Military Medical Academy, Belgrade. Vojnosanit Pregl, 72(6): 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mladenoviæ J, Veljoviæ M, Udovièiæ I, et al. (2015). Catheter-associated urinary tract infection in a surgical intensive care unit. Vojnosanit Pregl, 72(10): 883–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X, Ma J, HOu F, et al. (2016). Neurosurgical site infection prevention: single institute experience. Turk Neurosurg, 26(2): 234–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao Y, Shi G, Zhang J, et al. (2015). Surgical site infection after laparoscopic and open appendectomy: a multicenter large consecutive cohort study. Surg Endosc, 29(6): 1384–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seavey JG, Balazs GC, Steelman T, et al. (2017). The effect of preoperative lumbar epidural corticosteroid injection on postoperative infection rate in patients undergoing single-level lumbar decompression. Spine J, 17(9): 1209–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harold DM, Johnson EK, Rizzo JA, Steele SR. (2010). Primary closure of stoma site wounds after ostomy takedown. Am J Surg, 199(5): 621–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oncul O, Yüksel F, Altunay H, et al. (2002). The evaluation of nosocomial infection during 1-year-period in the burn unit of a training hospital in Istanbul, Turkey. Burns, 28(8): 738–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Öncül O, Öksüz S, Acar A, et al. (2014). Nosocomial infection characteristics in a burn intensive care unit: analysis of an eleven-year active surveillance. Burns, 40(5): 835–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oncul O, Ulkur E, Acar A, et al. (2009). Prospective analysis of nosocomial infections in a burn care unit, Turkey. Indian J Med Res,130(6):758–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaal J, Leclerc T, Soler C, et al. (2015). Epidemiology of filamentous fungal infections in burned patients: a French retrospective study. Burns, 41(4): 853–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becker WK, Cioffi WG, McManus AT, et al. (1991). Fungal burn wound infection: a 10-year experience. Arch Surg, 126(1): 44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horvath EE, Murray CK, Vaughan GM, et al. (2007). Fungal wound infection (not colonization) is independently associated with mortality in burn patients. Ann Surg, 245(6): 978–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng J, Wang C-T, Zhang F-S, et al. (2016). Effect of probiotics on the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled multicenter trial. Intensive Care Med, 42(6): 1018–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S, Goyal R, Ramesh G, et al. (2015). Control of hospital acquired infections in the ICU: A service perspective. Med J Armed Forces India, 71(1): 28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh S, Chaturvedi R, Garg S, et al. (2013). Incidence of healthcare associated infection in the surgical ICU of a tertiary care hospital. Med J Armed Forces India, 69(2): 124–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hajjej Z, Nasri M, Sellami W, et al. (2014). Incidence, risk factors and microbiology of central vascular catheter-related bloodstream infection in an intensive care unit. J Infect Chemother, 20(3): 163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karacaer Z, Oncul O, Turhan V, et al. (2014). A surveillance of nosocomial candida infections: epidemiology and influences on mortalty in intensive care units. Pan Afr Med J, 19: 398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis KA, Stewart JJ, Crouch HK, et al. (2004). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) nares colonization at hospital admission and its effect on subsequent MRSA infection. Clin Infect Dis, 39(6): 776–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DerSimonian R, Laird N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials, 7(3): 177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danchaivijitr S, Dhiraputra C, Santiprasitkul S, Judaeng T. (2005). Prevalence and impacts of nosocomial infection in Thailand 2001. J Med Assoc Thai, 88 Suppl 10:S1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izquierdo-Cubas F, Zambrano A, Frometa I, et al. (2008). National prevalence of nosocomial infections. Cuba 2004. J Hosp Infect, 68(3): 234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (2008). Annual epidemiological report on communicable diseases in Europe 2008. Stockholm: Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/0812_SUR_Annual_Epidemiological_Report_2008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Jr, et al. (2007). Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in US hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep, 122(2): 160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guggenheim M, Zbinden R, Handschin AE, et al. (2009). Changes in bacterial isolates from burn wounds and their antibiograms: a 20-year study (1986–2005). Burns, 35(4): 553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emaneini M, Beigverdi R, van Leeuwen WB, et al. (2018). Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from burn patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 12:202–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emaneini M, Jabalameli F, Rahdar H, et al. (2017). Nasal carriage rate of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Iranian healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop, 50(5): 590–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lahsaeizadeh S, Jafari H, Askarian M. (2008). Healthcare-associated infection in Shiraz, Iran 2004–2005. J Hosp Infect, 69(3): 283–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kallel H, Bahoul M, Ksibi H, et al. (2005). Prevalence of hospital-acquired infection in a Tunisian hospital. J Hosp Infect, 59(4): 343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jroundi I, Khoudri I, Azzouzi A, et al. (2007). Prevalence of hospital-acquired infection in a Moroccan university hospital. Am J Infect Control, 35(6): 412–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan K, Chen H-L. (2013). Obesity and surgical site infections risk in orthopedics: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg, 11(5): 383–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Newell MA, Bard MR, Goettler CE, et al. (2007). Body mass index and outcomes in critically injured blunt trauma patients: weighing the impact. J Am Coll Surg, 204(5): 1056–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serrano PE, Khuder SA, Fath JJ. (2010). Obesity as a risk factor for nosocomial infections in trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg, 211(1): 61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe A, Kohnoe S, Shimabukuro R, et al. (2008). Risk factors associated with surgical site infection in upper and lower gastrointestinal surgery. Surg Today, 38(5): 404–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eckenrode S, Bakullari A, Metersky ML, et al. (2014). The association between age, sex, and hospital-acquired infection rates: results from the 2009–2011 National Medicare Patient Safety Monitoring System. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 35 Suppl 3:S3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen B, Choi YJ, Hyman S, et al. (2013). Gender differences in risk of bloodstream and surgical site infections. J Gen Intern Med, 28(10): 1318–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saeed MJ, Olsen MA, Powderly WG, et al. (2017). Diabetes mellitus is associated with higher risk of developing decompensated cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Clin Gastroenterol, 51(1): 70–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee SC, Hua CC, Yu TJ, et al. (2005). Risk factors of mortality for nosocomial pneumonia: importance of initial anti-microbial therapy. Int J Clin Pract, 59(1): 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rello J, Ausino V, Ricart M, et al. (1993). Impact of previous antimicrobial therapy on the etiology and outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest, 104(4): 1230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vardakas KZ, Siempos II, Falagas ME. (2007). Short report Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for nosocomial pneumonia and associated mortality. Diabet Med, 24(10): 1168–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cavalcanti M, Ferrer M, Ferrer R, et al. (2006). Risk and prognostic factors of ventilator-associated pneumonia in trauma patients. Crit Care Med, 34(4): 1067–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liang SY, Mackowiak PA. (2007). Infections in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med, 23(2): 441–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.D’Agata EM, Mount DB, Thayer V, Schaffner W. (2000). Hospital-acquired infections among chronic hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis, 35(6): 1083–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ylipalosaari P, Ala-Kokko T, Laurila J, Ohtonen P, Syrjälä H. (2006). Epidemiology of intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired infections in a 14-month prospective cohort study in a single mixed Scandinavian university hospital ICU. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 50(10): 1192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]