Abstract

Nematode development is characterized by progression through several larval stages. Thousands of genes were found in large scale RNAi-experiments to block this development at certain steps, two of which target the molecular chaperone HSP-90 and its cofactor UNC-45. Aiming to define the cause of arrest, we here investigate the status of nematodes after treatment with RNAi against hsp-90 and unc-45 by employing an in-depth transcriptional analysis of the arrested larvae. To identify misregulated transcriptional units, we calculate and validate genome-wide coexpression cliques covering the entire nematode genome. We define 307 coexpression cliques and more than half of these can be related to organismal functions by GO-term enrichment, phenotype enrichment or tissue enrichment analysis. Importantly, hsp-90 and unc-45 RNAi induce or repress many of these cliques in a coordinated manner, and then several specifically regulated cliques are observed. To map the developmental state of the arrested nematodes we define the expression behaviour of each of the cliques during development from embryo to adult nematode. hsp-90 RNAi can be seen to arrest development close to the L4 larval stage with further deviations in daf-16 regulated genes. unc-45 RNAi instead leads to arrested development at young adult stage prior to the programmatic downregulation of sperm-cell specific genes. In both cases processes can be defined to be misregulated upon depletion of the respective chaperone. With most of the defined gene cliques showing concerted behaviour at some stage of development from embryo to late adult, the “clique map” together with the clique-specific GO-terms, tissue and phenotype assignments will be a valuable tool in understanding concerted responses on the genome-wide level in Caenorhabditis elegans.

Subject terms: Functional clustering, Gene regulatory networks, Microarrays, Germline development, RNAi

Introduction

Nematode-development is a highly complex process that is defined by temporal and spatial events in different tissues and cell types. Therefore simultaneous events are occurring in this process with chronological timing to enable the highly reproducible development program.

HSP-90 (DAF-21) is a molecular chaperone, crucial for the development of vulva, gonads and oocyte maturation as well as ensuring longevity of C. elegans1–3. It is an indispensable protein, activating and regulating many clients, for example protein kinases, and transcription factors, such as steroid receptors4–6. Inhibition of HSP-90, by either RNAi or specific compounds, therefore has the potential to interfere with several pathways. RNAi arrests the nematode development and reduces motility in later larval stages7,8. Prominent responses induced after hsp-90/daf-21 RNAi include the heat-shock response, which is known to be suppressed by HSP-90 in most organisms1,9,10. Other affected responses are potentially regulated in a more organism-specific manner, like the innate immune response, which is coupled to the heat-shock response in nematodes11,12. Interestingly, both of these responses are also dependent on the developmental state of the nematode, with the heat-shock response being barely inducible in early larvae and also in adult aging nematodes11. The reason for these correlations is unclear, but it could be supported by assigning genes clearly to individual responses, so that the common principles and regulatory patterns become obvious.

The HSP-90 cofactor UNC-45 participates in the muscle-specific functions of HSP-90. Invertebrates possess a single unc-45 gene, which is expressed in muscle cells, where UNC-45 performs HSP-90-dependet folding of the myosin motor domain. It further is expressed in non-muscle tissues of early embryos13–15. Depletion of the HSP-90-cofactor UNC-45 leads to rather specific morphological changes, like paralysis due to muscle cell defects and sterility in C. elegans7.

To see, whether these interacting factors influence common pathways, we compare the transcriptional response to depletion of these two proteins by microarray analysis. Microarrays are high-throuhgput analyses yielding a snapshot of the expression status of each represented gene16. For C. elegans a wealth of data exists, which link different sample conditions to the induction of certain marker genes. Here, as performed before for yeast17, we derive and validate genome-wide coexpression cliques and use statistical analyses to define the cliques responding to hsp-90 and unc-45 RNAi treatment.

Material and methods

Clustering of genes and coexpression clique separation

Construction of the genome-wide coexpression “clique map” for the nematode GPL200 platform was performed as a stepwise procedure as described for the GPL2529 platform of yeast before17. In short, all available microarray datasets for the GPL200 platform (Affymetrix C. elegans Genome Array) were obtained from the GEO repository18. This included 2243 individual microarray experiments (Supplemental Table 1). These were normalized against each other with the software RMAexpress (Bolstad, 2014; http://rmaexpress.bmbolstad.com/19). Based on these normalized values, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were obtained for each probe-probe pair of the 22,620 probes represented on this array type. The resulting list of correlation coefficients was then ranked to generate the ranked coexpression database with information on each probe represented on the GPL200 platform. The probes were then translated from ProbeSetIDs to the given C. elegans gene names. Genes, which were represented by more than one ProbeSetID on this array type, which is the case for 8052 ProbeSets, were specifically labelled to allow distinguishing these ProbeSetIDs in later evaluations. Confirming the quality of the ranked lists, in many cases the top coregulated ProbeSets are two ProbeSets reporting on the same gene (data not shown).

The database was then used to generate a network from these ranked lists by connecting the Top11 genes of each list and collecting these connections for all 22,620 genes employing the algorithm accessible on the webserver clusterEX.de20. In short, 121 connections were generated from the Top11 genes and added to an extensive list collecting all these pairwise interactions, thereby generating a network. The final network contained more than 600,000 unique gene–gene connections from about 2,700,000 gene–gene correlations. Thus on average a connection was obtained 4.5 times, leading to a network density almost on par with that of our previously generated network for yeast17. This genome-wide nematode gene network was then used to extract the individual cliques by isolating high density areas in an automated fashion from the network as described before17. Altogether 307 cliques were obtained, with the largest clique containing 1327 genes and the smallest clique containing 5 genes. The nematode analysis methods are added to the webserver functionality.

GO-term, phenotype and tissue enrichment

GO-term enrichment was analysed to test, whether some of the 307 aforementioned cliques enrich genes with functional similarity. To this end also published information from phenotype and tissue enrichment studies was used. As such the associations between genes and GO-terms were obtained from the “go_dictionary.csv” table available from https://github.com/dangeles/TissueEnrichmentAnalysis21. For phenotype enrichment the table “phenotype_ontology.csv” was employed (PEA22) and for tissue enrichment the tissue sets designated as “genesets_golden” were utilized. In all cases the calculation of the enrichment was performed as described17 (Supplemental Table 2). 20 randomly scrambled clique sets were generated to determine, whether enrichment is considered relevant up to p-values of 1e-3, 1e-4 or beyond 1e-5.

Gene-expression changes after RNAi against hsp-90 and unc-45

RNAi was used to deplete nematodes of hsp-90 or unc-45 mRNA and to induce the growth arrest and the transcriptomic responses of the nematodes. RNAi-treated nematodes were washed off the plates and were shock frozen immediately. Microarray experiments were performed at the Zentrum für Fluoreszente Proteinanalytik in Regensburg. To study the response to hsp-90 RNAi or unc-45 RNAi we analysed independent biological replicates. In these experiments, RNAi did not always yield the same level of growth arrest in the case of hsp-90, where the first microarray experiment produced a weaker response. We used each experiment sample/control-pair to assign all its differential expression values to the coexpression cliques and analysed those in respect to significant induction or repression. As the RNAi experiments were analysed on the more rarely employed GPL19230 Affymetrix platform (Affymetrix C. elegans Gene 1.0 ST Array), we bridged the cliques obtained from GPL200 ProbeSets to the GPL19230 ProbeSets. This bridging was performed by employing the given gene names without the ProbeSet-specific indexing. If a gene was represented by more than one ProbeSet in the cliques, then each of those instances was given the value determined from the GPL19230 expression data. If on the other hand, only one GPL200-derived ProbeSet was present in the cliques and several ProbeSets for this gene are recoded on the GPL19230 arrays, then the GPL19230-values were averaged and this value was used to color the clique map and to derive the statistical parameters for the clique. If the same gene contained two different probes on both platforms, then the averaged GPL19230-value was used in both occurences in the clique map. 1603 ProbeSets of the “clique map” did not receive data from GPL19230 this way and had to be omitted in the analysis. Despite these bridging needs between the platforms, significant changes in many cliques can be detected in each analysed RNAi experiment. The observed experiments were also analysed with the Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC, Thermo Fisher Scientific) as a state-of-art method for analysis of microarray data.

Statistical analysis employing the clique map was done as described before17. In short, color coding of the clique set figures was done by determining the differential values for each gene and then assigning discrete values between − 4 and + 4 for the transcriptional changes of log2 < − 1 to log2 > + 1. For each discrete value a red tone or blue tone was defined in Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/)23. In cases where responses were weak, like both unc-45 experiments, the scale was adjusted to reach from log2 < − 0.25 to log2 > + 0.25. This analysis leads to information on most cliques as to whether they are induced or repressed with statistical significance as described before17. This method to evaluate nematode array data will be implemented for public use in the clusterEX.de webserver, which currently has this functionality only for yeast arrays.

Correlation analysis between different samples was made by plotting the cliques’ expression values against each other and obtaining the coefficient of determination R2 for the regression line. If R2 was closer to 1, the correlation between the two sets was considered to be better. These results were compared to correlations on the gene level in cases where identical array types were utilized.

Analysis of microarray data on development

To define moments of clique relevance during development, time points from developmental series were used to determine a transcriptional status for each clique in the map. In many cases, cliques react to developmental steps as concerted units resulting in a non-random distribution of up- and downregulated hits throughout the 307 cliques. To cover several larval states, three published GPL200 series were obtained from the GEO repository. These represent a time course of early development with data from embryo, L1 and L4 larvae (GSE654724) and a time course describing the aging process with time points at L4 larvae, and adults at day6 and day15 of development (GSE2178425). Lastly, a time-course was included describing different stages of larval development, composed of L3, L3-lethargus, L4, L4-lethargus and young adult (GSE4629126). Expression values were obtained from the normalized data table containing all public GPL200 experiments (see above).

Results

A genome-wide coexpression clique map for the nematode C. elegans

To obtain transcriptional units influenced by hsp-90 and unc-45 RNAi-treated nematodes, we first generated gene cliques that are coregulated in C. elegans, in which each of the 22,620 genes is assigned to exactly one clique. We had used the same procedure before to generate a coexpression clique map for S. cerevisiae17. Based on the same stepwise procedure, we grouped every gene reported on standard microarrays of the GPL200 platform into one coexpression clique of at least five genes. The procedure resulted in 307 coexpression cliques, which were visualized in Cytoscape to generate the “coexpression clique map” for C. elegans. We set out to test, whether these 307 coexpression cliques are gene groups with a high level of functional similarity, as it was observed for the yeast clique map before17. Therefore, we investigated all cliques by GO-term enrichment analysis. 220 of the 307 cliques show a GO-term enrichment with a p-value lower than 1e–3, 172 showed less than 1e–4, and 148 of the 307 cliques showed p-values of less than 1e–5 (Best results in Table 1). This is far better than 307 random cliques, which yielded these p-values 18 times, 2 times and zero times. We also found significant enrichments employing phenotype enrichment analysis (PEA22) and tissue enrichment analysis (TEA21) with 145, 106 and 81 cliques being enriched for the same phenotype (20, 3 and 0 times in random cliques) and 45, 37 or 29 cliques being enriched for tissue-specific expression in the three p-value categories (0, 0, and 0 times in random cliques). The values also are far better than cliques composed of random genes. In this way, roughly two thirds of the 307 coexpression cliques were assigned either a function, a related phenotype or a tissue-specific expression with acceptable significance criteria of below 1e–4 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Most relevant coexpression cliques of the clique map, their size and position, GO-term assignment, phenotype enrichment and tissue enrichment.

| Clusternumber | Cluster name | Clique position | Best GO-term | log10(pvalue)_GO | Enrichment-Fold_GO | Best PEA-Term | log10(pvalue)_PEA | Enrichment-Fold_PEA | Best TEA-Term | log10(pvalue)_TEA | Enrichment-Fold_TEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | rps-14_21270-rps-11_20714 | R4 C17 | Structural constituent of ribosome GO:0003735 | 189.66 | 83.29 | Pleiotropic defects severe early emb WBPhenotype:0,000,270 | 120.69 | 43.09 | WBPaper00026980_intestine_enriched_WBbt_0005772_1970 | 1.44 | 1.28 |

| 211 | srj-42-srw-113 | R1 C1 | Sensory perception GO:0007600 | 143.77 | 6.31 | Dauer metabolism variant WBPhenotype:0,001,547 | 10.86 | 2.84 | WBPaper00040420_FLP_enriched_WBbt_0006828_288 | 0.00 | 0.46 |

| 282 | srj-21-srh-32 | R1 C3 | Intrinsic component of membrane GO:0031224 | 128.75 | 2.29 | Dauer metabolism variant WBPhenotype:0,001,547 | 7.14 | 3.04 | WBPaper00040420_FLP_enriched_WBbt_0006828_288 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

| 187 | F45H10.2-R53.4_21676 | R3 C4 | Organelle Inner membrane GO:0019866 | 74.24 | 34.23 | Avoids bacterial lawn WBPhenotype:0,000,402 | 27.00 | 6.57 | WBPaper00026980_intestine_enriched_WBbt_0005772_1970 | 3.37 | 1.50 |

| 93 | flp-5-F17C11.2 | R4 C4 | Neuropeptide signaling pathway GO:0007218 | 56.65 | 67.09 | Sinusoidal movement variant WBPhenotype:0,004,018 | 22.79 | 11.85 | WBPaper00037950_all-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0003679_1013 | 22.28 | 3.93 |

| 90 | ckr-1-T09B9.3 | R1 C5 | Intrinsic component of membrane GO:0031224 | 52.94 | 1.97 | Sinusoidal movement variant WBPhenotype:0,004,018 | 8.60 | 3.85 | WBPaper00037950_all-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0003679_1013 | 53.78 | 4.32 |

| 42 | rab-28-jbts-14_9542 | R3 C5 | Cell projection assembly GO:0030031 | 45.54 | 56.43 | Amphid phasmid sensillum morphology variant WBPhenotype:0,001,527 | 16.40 | 17.48 | WBPaper00037950_BAG-neuron_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006825_454 | 42.10 | 7.48 |

| 203 | sre-33-ZK1025.1_8337 | R1 C2 | Sensory perception GO:0007600 | 45.42 | 4.04 | Dauer metabolism variant WBPhenotype:0,001,547 | 6.13 | 2.24 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.02 | 0.64 |

| 84 | col-84-col-45 | R9 C17 | Collagen trimer GO:0005581 | 44.38 | 77.74 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0,000,583 | 3.04 | 8.11 | WBPaper00040420_FLP_enriched_WBbt_0006828_288 | 0.00 | 0.20 |

| 41 | col-117-col-167_1015 | R9 C25 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | 39.93 | 83.10 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0,000,583 | 5.47 | 7.68 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| 233 | his-46_959-his-64 | R10 C26 | DNA packaging complex GO:0044815 | 39.57 | 191.32 | Sister chromatid segregation defective early emb WBPhenotype:0,000,772 | 26.48 | 94.19 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| 215 | col-138-col-49 | R9 C23 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | 35.30 | 87.06 | Blistered WBPhenotype:0,000,025 | 5.77 | 41.59 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.07 | 0.60 |

| 80 | rps-14_21270-rps-11_20714 | R4 C17 | Structural constituent of ribosome GO:0003735 | 189.66 | 83.29 | Pleiotropic defects severe early emb WBPhenotype:0,000,270 | 120.69 | 43.09 | WBPaper00026980_intestine_enriched_WBbt_0005772_1970 | 1.44 | 1.28 |

| 31 | pbs-3_18439-rpn-5 | R3 C7 | Modification-dependent macromolecule catabolic process GO:0043632 | 23.08 | 13.30 | Meiosis defective early emb WBPhenotype:0,001,041 | 32.03 | 23.37 | WBPaper00031003_24hr_muscle_enriched_WBbt_0003675_918 | 2.78 | 1.65 |

| 187 | F45H10.2-R53.4_21676 | R3 C4 | Organelle inner membrane GO:0019866 | 74.24 | 34.23 | Avoids bacterial lawn WBPhenotype:0,000,402 | 27.00 | 6.57 | WBPaper00026980_intestine_enriched_WBbt_0005772_1970 | 3.37 | 1.50 |

| 233 | his-46_959-his-64 | R10 C26 | DNA packaging complex GO:0044815 | 39.57 | 191.32 | Sister chromatid segregation defective early emb WBPhenotype:0,000,772 | 26.48 | 94.19 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| 93 | flp-5-F17C11.2 | R4 C4 | Neuropeptide signaling pathway GO:0007218 | 56.65 | 67.09 | Sinusoidal movement variant WBPhenotype:0,004,018 | 22.79 | 11.85 | WBPaper00037950_all-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0003679_1013 | 22.28 | 3.93 |

| 2 | rps-5_2365-rpl-15_1655 | R10 C23 | Structural constituent of ribosome GO:0003735 | 24.02 | 68.88 | Pleiotropic defects severe early emb WBPhenotype:0,000,270 | 19.08 | 40.82 | WBPaper00037950_PVD-OLL-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0006831_878 | 0.00 | 0.23 |

| 143 | his-20_965-his-4 | R11 C22 | DNA packaging complex GO:0044815 | 30.10 | 191.32 | Sister chromatid segregation defective early emb WBPhenotype:0,000,772 | 18.37 | 87.98 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| 96 | mup-2-unc-87_284 | R3 C13 | Myofibril GO:0030016 | 31.32 | 27.72 | Muscle system morphology variant WBPhenotype:0,000,603 | 17.34 | 8.57 | WBPaper00031003_0hr_muscle_enriched_WBbt_0003675_761 | 20.71 | 3.64 |

| 218 | H28G03.5_1027-H28G03.5_1042 | R11 C24 | Cell recognition GO:0008037 | 18.80 | 92.91 | Axon fasciculation variant WBPhenotype:0,000,632 | 17.15 | 63.29 | WBPaper00045521_Spermatogenic_WBbt_0005784_2743 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| 42 | rab-28-jbts-14_9542 | R3 C5 | Cell projection assembly GO:0030031 | 45.54 | 56.43 | Amphid phasmid sensillum morphology variant WBPhenotype:0,001,527 | 16.40 | 17.48 | WBPaper00037950_BAG-neuron_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006825_454 | 42.10 | 7.48 |

| 234 | pcn-1-cyb-3_17196 | R7 C12 | DNA replication GO:0006260 | 13.16 | 29.41 | Cytokinesis variant WBPhenotype:0,002,408 | 16.17 | 11.19 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | 0.01 | 0.48 |

| 197 | unc-11_429-unc-11_430 | R12 C11 | Phosphatidylinositol binding GO:0035091 | 15.76 | 172.19 | Mid larval lethal WBPhenotype:0,000,116 | 15.12 | 160.50 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005751_570 | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| 1 | Y40H4A.2-ZK1053.2 | R1 C6 | Phosphorus metabolic process GO:0006793 | 17.12 | 3.03 | Spermatogenesis variant WBPhenotype:0,000,670 | 1.48 | 4.25 | WBPaper00045521_Spermatogenic_WBbt_0005784_2743 | 165.27 | 4.57 |

| 20 | T22D1.5-inx-14 | R2 C1 | Embryo development GO:0009790 | 13.09 | 1.97 | Aneuploidy WBPhenotype:0,001,882 | 11.50 | 6.39 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 73.49 | 5.82 |

| 273 | C01G10.14-dct-9_3227 | R2 C3 | Regulation of cell shape GO:0008360 | 20.29 | 18.38 | Spermatogenesis variant WBPhenotype:0,000,670 | 2.62 | 7.10 | WBPaper00045521_Spermatogenic_WBbt_0005784_2743 | 71.95 | 3.62 |

| 111 | mlt-9_22518-F33D4.6_14044 | R2 C6 | Cuticle development GO:0042335 | 16.79 | 11.64 | Molt variant WBPhenotype:0,002,041 | 12.53 | 5.66 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | 56.15 | 6.08 |

| 90 | ckr-1-T09B9.3 | R1 C5 | Intrinsic component of membrane GO:0031224 | 52.94 | 1.97 | Sinusoidal movement variant WBPhenotype:0,004,018 | 8.60 | 3.85 | WBPaper00037950_all-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0003679_1013 | 53.78 | 4.32 |

| 42 | rab-28-jbts-14_9542 | R3 C5 | Cell projection assembly GO:0030031 | 45.54 | 56.43 | Amphid phasmid sensillum morphology variant WBPhenotype:0,001,527 | 16.40 | 17.48 | WBPaper00037950_BAG-neuron_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006825_454 | 42.10 | 7.48 |

| 213 | xbx-3-DH11.5_20397 | R1 C12 | Signaling GO:0023052 | 15.19 | 2.38 | Backward point velocity increased WBPhenotype:0,002,325 | 7.12 | 8.29 | WBPaper00037950_all-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0003679_1013 | 41.49 | 4.53 |

| 155 | F42A9.7-T22B3.3 | R3 C11 | Regulation of cell shape GO:0008360 | 9.67 | 17.73 | Dauer metabolism variant WBPhenotype:0,001,547 | 1.51 | 2.28 | WBPaper00045521_Spermatogenic_WBbt_0005784_2743 | 25.38 | 2.62 |

| 83 | sol-1-jnk-1_18695 | R1 C9 | Nervous system development GO:0007399 | 21.52 | 4.87 | Synapse morphology variant WBPhenotype:0,000,616 | 10.59 | 8.04 | WBPaper00031532_Larva_Pan_Neuronal_Enriched_WBbt_0003679_1603 | 25.10 | 2.45 |

| 93 | flp-5-F17C11.2 | R4 C4 | Neuropeptide signaling pathway GO:0007218 | 56.65 | 67.09 | Sinusoidal movement variant WBPhenotype:0,004,018 | 22.79 | 11.85 | WBPaper00037950_all-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0003679_1013 | 22.28 | 3.93 |

| 96 | mup-2-unc-87_284 | R3 C13 | Myofibril GO:0030016 | 31.32 | 27.72 | Muscle system morphology variant WBPhenotype:0,000,603 | 17.34 | 8.57 | WBPaper00031003_0hr_muscle_enriched_WBbt_0003675_761 | 20.71 | 3.64 |

| 34 | dhs-28_22199-acs-14 | R4 C9 | Oxoacid metabolic process GO:0043436 | 14.25 | 9.18 | Lipid metabolism variant WBPhenotype:0,000,725 | 4.43 | 3.34 | WBPaper00037950_intestine_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005772_886 | 20.41 | 3.78 |

hsp-90 RNAi affects embryo development and induces stress responses

Having confirmed that the “clique map” of coexpressed genes also holds information on functional, phenotypic and tissue-specific signatures, we set out to investigating the transcriptional response of hsp-90 RNAi-treated nematodes. We previously had analysed these microarray data based on the Top250 differential regulated genes obtained from three experiments11. hsp-90 depleted nematodes showed sterility, incomplete development of gonad arms and the formation of endomitotic oocytes7,27. Development is mostly blocked at a later larval stage. TAC analysis revealed many genes with substantially different expression levels and showed the strongest response in the experiment 1 (P152), while the experiment 2 (A966) and 3 (P062) showed a weaker response (Fig. 1a). Gene expression changes had implied the induction of the heat-shock response and the innate immune response in analyses before11, but due to the focus on only 500 of the 22,620 genes measured with this array type, information from the many weaker affected genes could not be considered in this study11.

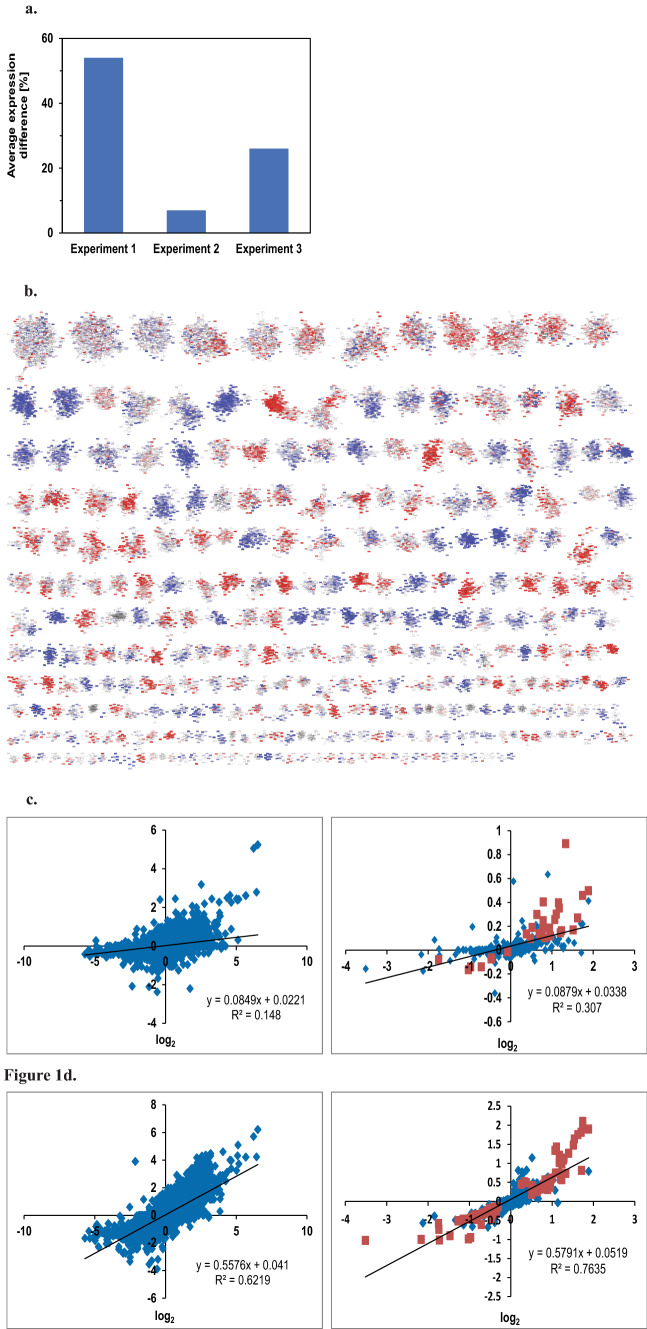

Figure 1.

hsp-90 RNAi affects embryo development and induces stress responses. (a) Average gene expression difference of the experiments, determined with TAC, compared to the control RNAi. (b) Clique map for experiment 1 of hsp-90 RNAi versus young adult of control RNAi. A more detailed description of the most strongly affected cliques can be found in Table 2 and corresponds to the positions in the clique map. (c) Comparison between experiment 1 and 3 on a gene-by-gene basis (left panel) and comparison between experiment 1 and 3 on a clique-by-clique basis (right panel). (d) Comparison between experiment 1 and 2 on a gene-by-gene basis (left panel) and comparison between experiment 1 and 2 on a clique-by-clique basis (right panel). The clique maps of experiment 3 and 2 are shown as Supplemental Fig. 1b and c. Cliques colored in red are induced upon RNAi while cliques in blue are repressed. The linear regression function was generated with Microsoft Excel without weighting, a square value of 1 would indicate a perfect correlation between the cliques.

The genome-wide gene expression cliques as defined here, instead allow visualization and analysis of all values. Significance analysis showed enrichment of up- and downregulation in many cliques for experiment 1 (Fig. 1b), but also for the other experiments 2 and 3 (Supplemental Fig. 1b and c). Indeed almost half of the cliques respond to the RNAi-treatment with a concerted response of their genes (Best cliques in Table 2). We first determined the upregulated cliques: these contain the clique col-138-col-49, which is holding genes related to the “structural constituent of cuticle” and the clique abu-7-abu-8_22491 related to the “response to unfolded protein”. The largest upregulated clique, containing 209 genes, is mlt-9_22518-F33D4.6_14044 (“cuticle development” with phenotype of “molt variant” and localized in the “embryo hypodermis”) and other cliques related to cuticle formation, including R12E2.14_75-R12E2.15, col-117-col-167_1015, col-146-col-133, col-128-cdh-10_9234 (enriched in “peptidase activity”) and sqt-2-dpy-9. Cliques which are strongly upregulated also in experiment 2, include the cliques related to the “immune system response” C10C5.2-Y58A7A.3 and K08D10.9-F46A8.1. Based on the assignment of GO-terms, phenotypes and tissues, the largest and strongest downregulated cliques (Table 2) represent “embryo development” (T22D1.5-inx-14, enriched phenotype of “aneuploidy” and localized in “embryonic germline precursors”), “embryo development” (T24D1.3-egg-1, enriched phenotype of “polar body defective early embryo”) and “reproduction” (puf-3-oma-2_18268, enriched phenotype “meiotic chromosome segregation variant” localized in the “germline_precursors”) among many other cliques hinting at the stalled gonad development in agreement with the sterility phenotype observed. Comparing the three experiments a weak correlation can be found between experiment 2 and 1 (R2 = 0.148) on a gene-by-gene level, which is increased, if cliques are compared (R2 = 0.307, Fig. 1c). The same trend can be seen between experiments 3 and 1 correlating with R2 = 0.622 for a gene-to-gene comparison, which increases to R2 = 0.764, if cliques are compared (Fig. 1d). Moreover the significance analysis employing 20 random cliques shows that the most strongly up- and downregulated cliques also are usually fulfilling the 1e-5 significance criterium in the compared experiments (Fig. 1c and d, colored in red).

Table 2.

Most strongly affected cliques by hsp-90 RNAi and their characteristics.

| Cluster name | Clique position | Best GO-Term | Best PEA-Term | Best TEA-Term | Mean STD | Log10(p) Exp 1 | Log10(p) Exp 2 | Log10(p) Exp 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| col-138-col-49 | R9 C23 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Blistered WBPhenotype:0000025 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 1.43 ± 0.71 | 28.5 | 35.6 | 70.2 |

| abu-7-abu-8_22491 | R8 C26 | Response to unfolded protein GO:0006986 | Dauer constitutive WBPhenotype:0000012 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 1.43 ± 0.66 | 38.9 | 38.4 | 51.4 |

| agmo-1_5527-F53B1.4 | R10 C14 | Pyridoxal phosphate binding GO:0030170 | Molt variant WBPhenotype:0002041 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | 1.29 ± 0.76 | 14.4 | 3.2 | 48.0 |

| bus-8_3160-K04H4.2_2324 | R9 C2 | Amino sugar metabolic process GO:0006040 | Molt variant WBPhenotype:0002041 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 1.25 ± 0.73 | 30.4 | 3.5 | 103.9 |

| R12E2.14_75-R12E2.15 | R6 C9 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0,000,583 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 1.22 ± 0.67 | 51.2 | 21.3 | 182.3 |

| mlt-9_22518-F33D4.6_14044 | R2 C6 | Cuticle development GO:0042335 | Molt variant WBPhenotype:0002041 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | 1.08 ± 0.72 | 137.7 | 2.6 | 133.0 |

| R12A1.3-M195.2 | R6 C19 | Amino sugar metabolic process GO:0006040 | Dauer constitutive WBPhenotype:0000012 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 1.05 ± 0.63 | 42.2 | 14.3 | 46.7 |

| hsp-16.2-F44E5.4_19238 | R12 C4 | Response to heat GO:0009408 | cadmium response variant WBPhenotype:0001653 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 1.03 ± 0.62 | 3.6 | 6.2 | 1.7 |

| lys-3-tsp-1 | R11 C40 | Carbohydrate metabolic process GO:0005975 | Male nervous system development variant WBPhenotype:0001008 | WBPaper00040420_ALM_PLM_enriched_WBbt_0005406_198 | 0.99 ± 0.25 | 6.4 | 28.8 | 6.0 |

| col-117-col-167_1015 | R9 C25 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 0.94 ± 0.47 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 20.0 |

| C38C6.3-acdh-6 | R6 C14 | Intrinsic component of membrane GO:0031224 | Intestinal vacuole WBPhenotype:0001428 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | 0.91 ± 0.59 | 71.0 | 1.4 | 59.3 |

| pqn-54-abu-9 | R6 C11 | Response to unfolded protein GO:0006986 | Shortened life span WBPhenotype:0001171 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 0.91 ± 0.4 | 37.6 | 43.3 | 33.7 |

| col-146-col-133 | R9 C28 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.89 ± 0.46 | 10.0 | 6.5 | 26.7 |

| C36C5.12-F57G8.7 | R11 C9 | Negative regulation of proteolysis GO:0045861 | Male tail morphology variant WBPhenotype:0000070 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.83 ± 0.71 | 13.9 | 1.3 | 5.0 |

| col-128-cdh-10_9234 | R3 C12 | Peptidase activity GO:0008233 | Molt variant WBPhenotype:0002041 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005733_1250 | 0.82 ± 0.56 | 66.1 | 0.6 | 61.0 |

| ptr-23_236-ptr-23_16340 | R12 C6 | Male sex differentiation GO:0046661 | Developmental pigmentation variant WBPhenotype:0001009 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | 0.79 ± 0.56 | 6.0 | 0.2 | 9.5 |

| C10C5.2-Y58A7A.3 | R4 C11 | Immune system process GO:0002376 | Cadmium response variant WBPhenotype:0001653 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.77 ± 0.31 | 36.6 | 83.0 | 39.9 |

| sqt-2-dpy-9 | R9 C6 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005733_1250 | 0.76 ± 0.48 | 13.0 | 1.0 | 18.9 |

| dos-2-grd-2 | R8 C7 | Extracellular region GO:0005576 | Pericellular component morphology variant WBPhenotype:0000912 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | 0.75 ± 0.52 | 15.4 | 0.3 | 36.4 |

| K08D10.9-F46A8.1 | R11 C42 | Immune system process GO:0002376 | Actin organization biogenesis variant WBPhenotype:0001587 | WBPaper00037950_excretory-cell_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005812_528 | 0.72 ± 0.12 | 3.7 | 12.9 | 2.2 |

| vit-2-vit-4_22519 | R12 C22 | Extracellular region GO:0005576 | Pathogen susceptibility increased WBPhenotype:0001013 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | − 1.57 ± 1.42 | 47.9 | 2.5 | 5.7 |

| C17E7.4-T06D4.1 | R5 C13 | ribonucleoprotein granule GO:0035770 | P granule defective WBPhenotype:0001301 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | − 1.07 ± 0.87 | 168.7 | 1.2 | 72.1 |

| 171971_x_at-D1054.11_184 | R11 C37 | Cell GO:0005623 | Egg laying defective WBPhenotype:0000006 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005733_1250 | − 0.96 ± 0.84 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| sea-1-R04D3.4 | R7 C13 | Nucleoside-triphosphatase regulator activity GO:0060589 | Embryonic development variant WBPhenotype:0000749 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | − 0.93 ± 0.69 | 39.7 | 4.0 | 53.7 |

| T24D1.3-egg-1 | R7 C17 | Embryo development GO:0009790 | Polar body defective early emb WBPhenotype:0001147 | WBPaper00037950_GABAergic-motor-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005190_132 | − 0.82 ± 0.72 | 36.0 | 0.3 | 24.0 |

| C46C2.5_15926-W03F11.1 | R9 C22 | Carbohydrate binding GO:0030246 | Apoptosis increased WBPhenotype:0000183 | WBPaper00037950_GABAergic-motor-neurons_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005190_361 | − 0.82 ± 0.57 | 15.7 | 2.5 | 13.8 |

| ZC373.2-Y62H9A.6_1596 | R3 C18 | Flavonoid metabolic process GO:0009812 | Cell membrane organization biogenesis variant WBPhenotype:0001982 | WBPaper00037950_dopaminergic-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0006746_1230 | − 0.8 ± 0.7 | 53.5 | 6.0 | 32.5 |

| ZK1053.4-C08F1.6 | R4 C16 | Embryo development GO:0009790 | Embryonic development variant WBPhenotype:0000749 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | − 0.73 ± 0.4 | 70.9 | 12.9 | 40.5 |

| T05E12.6_12439-T05E12.6_12396 | R10 C3 | Lipid catabolic process GO:0016042 | Transgene expression increased WBPhenotype:0001236 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | − 0.72 ± 0.82 | 28.7 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| fbxc-28-sdz-28 | R7 C8 | Modification-dependent macromolecule catabolic process GO:0043632 | L1 larval development variant WBPhenotype:0000751 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | − 0.69 ± 0.39 | 26.3 | 23.5 | 41.6 |

| K09D9.12-T10C6.10 | R10 C7 | Protein polyubiquitination GO:0000209 | Fat content reduced WBPhenotype:0001183 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | − 0.62 ± 0.54 | 7.6 | 1.2 | 3.8 |

| puf-3-oma-2_18268 | R5 C14 | Reproduction GO:0000003 | Meiotic chromosome segregation variant WBPhenotype:0001499 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | − 0.6 ± 0.53 | 24.0 | 0.8 | 12.3 |

| 172276_x_at-Y116F11B.10_466 | R12 C20 | Chromosome segregation GO:0007059 | Rachis wide WBPhenotype:0001943 | WBPaper00036375_enriched_in_PVD_OLL_WBbt_0006831_2180 | − 0.59 ± 0.47 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| C41G7.3_2766-ani-2_2946 | R8 C2 | Multi-organism reproductive process GO:0044703 | Cytokinesis variant WBPhenotype:0002408 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | − 0.59 ± 0.51 | 26.0 | 0.8 | 9.0 |

| T22D1.5-inx-14 | R2 C1 | Embryo development GO:0009790 | Aneuploidy WBPhenotype:0001882 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | − 0.54 ± 0.48 | 122.7 | 2.0 | 60.1 |

| let-99_22121-B0238.9_11154 | R6 C21 | Organelle fission GO:0048285 | Embryonic development variant WBPhenotype:0000749 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | − 0.52 ± 0.44 | 16.6 | 0.2 | 15.4 |

| Y116A8C.19-F38C2.7 | R10 C25 | Poly(A) RNA binding GO:0044822 | Dauer metabolism variant WBPhenotype:0001547 | WBPaper00040420_FLP_enriched_WBbt_0006828_288 | − 0.49 ± 0.25 | 4.8 | 5.5 | 4.5 |

| daf-18_2911-ced-2_4092 | R8 C23 | Nuclear transport GO:0051169 | Cell death variant WBPhenotype:0000729 | WBPaper00037950_GABAergic-motor-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005190_132 | − 0.48 ± 0.4 | 6.9 | 0.6 | 10.0 |

| pcn-1-cyb-3_17196 | R7 C12 | DNA replication GO:0006260 | Cytokinesis variant WBPhenotype:0002408 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | − 0.47 ± 0.38 | 17.2 | 1.5 | 5.3 |

| C10C5.3-C10C5.5 | R12 C40 | Oxoacid metabolic process GO:0043436 | Dauer constitutive WBPhenotype:0000012 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | − 0.47 ± 0.48 | 2.6 | 5.1 | 2.2 |

Clique positions (letter = row, number = position from left to right) correspond to the clique map shown in Fig. 1b.

unc-45 RNAi leads to delayed conclusion of sperm and vulva development

We then investigated the RNAi treatment against the HSP-90 cofactor unc-45 with the same approach. unc-45 RNAi-treatment leads to developmental disruptions and incomplete fertility at a more adult stage. To see, whether differences in the cliques can be observed we performed two independent RNAi-experiments with subsequent transcriptome analysis on DNA microarrays. Analysis with TAC showed a weaker response compared to the hsp-90 RNAi in both experiments (Fig. 2a, Supplemental Fig. 2a). This also was evident in the analysis of the 307 expression cliques, where the color scheme had to be adjusted to visualize the concerted reactions (Fig. 2b and Supplemental Fig. 2b). Gene–gene comparisons showed a coefficient of determination of 0.15 between the experiments. When cliques were compared a coefficient of determination of 0.48 was obtained (Fig. 2c), confirming that also very weak responses can yield higher levels of repeatability by comparing matched groups of genes and not individual genes.

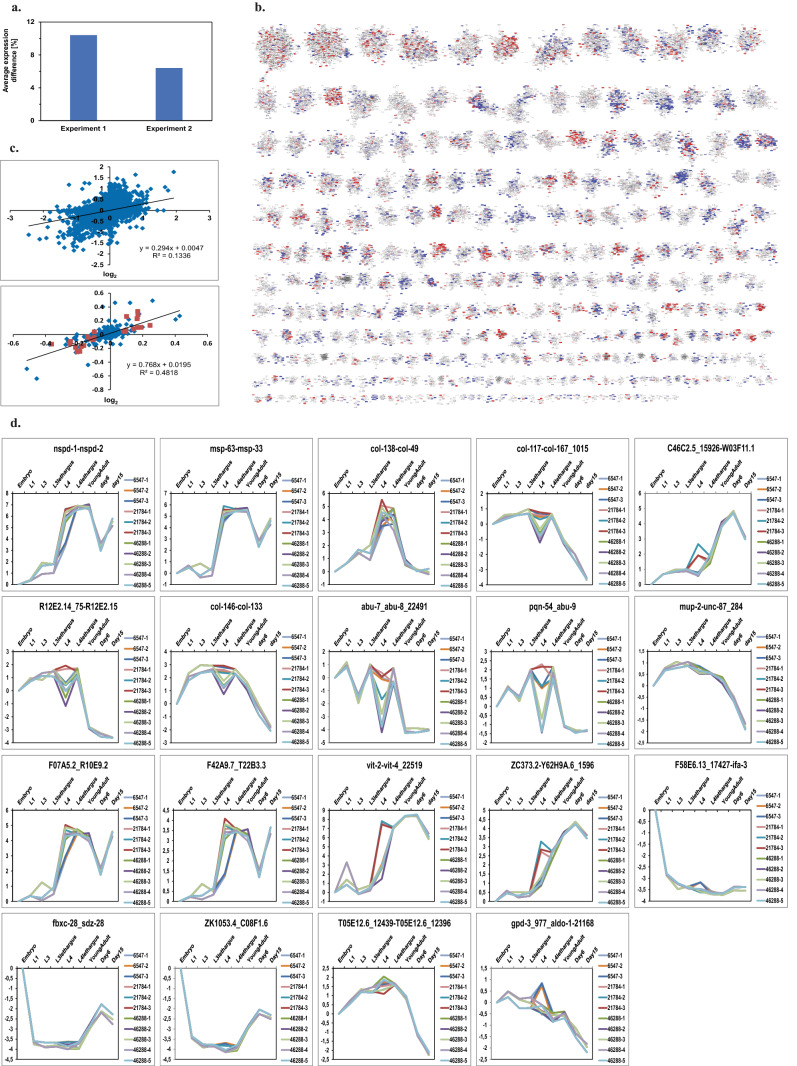

Figure 2.

unc-45 RNAi leads to delayed conclusion of sperm and vulva development. (a) Average gene expression difference of the experiments, determined with TAC, compared to the control RNAi. (b) Clique map for experiment 1 of unc-45 RNAi versus young adult of control RNAi. A more detailed description of the most strongly affected cliques can be found in Table 3 and corresponds to the positions in the clique map. (c) Comparison between experiment 1 and 2 on a gene-by-gene basis (upper panel) and comparison between experiment 1 and 2 on a clique-by-clique basis (lower panel). The clique map of experiment 2 is shown as Supplemental Fig. 2b, d) Clique trends during development of C. elegans. Described interaction between genes involved in sperm development is shown as Supplemental Fig. 2c. Cliques colored in red are induced upon RNAi while cliques in blue are repressed. The linear regression function was generated with Microsoft Excel without weighting, a square value of 1 would indicate a perfect correlation between the cliques.

Like with hsp-90 RNAi, specific cliques were found in all experiments to be significantly altered in their expression behavior. Upregulated are a few smaller cliques, like col-117-col-167_1015, msp-63-msp-33 and abu-7-abu-8_22491. These represent decisions to produce cuticle collagens, linker cell movement and induction of a response to heat. This also is reflected by the induction of hsp-16.2-F44E5.4_19238, a small clique containing the heat-shock proteins. This induction of the heat-shock response has been observed for unc-45 RNAi before7. Downregulated cliques represent the large cliques ZK1053.4-C08F1.6 (embryo development), ZC373.2-Y62H9A.6_1596 (cell membrane biogenesis) and sdz-10-fbxb-62 (L1 larval development). The weak differences, while being statistically significant for the described cliques, correlate with the mostly adult state of the nematode after unc-45 RNAi treatment and the observation that most developmental steps were performed, but the correct embryo development and the development of the vulva structure were affected7.

A hint towards the lacking germ line development may be derived from the misregulation of the cliques msp-36_msp-63 (linker-cell migration variant), which contains several genes related to sperm development and the downregulation of nspc-1_614-nspc-10_22525 (spermatogenesis variant). Thus, while vulva development and sperm development are stalled, certain features of the regulatory pathways are not deviating from the control nematodes and only later stages of the programmatic decision process show deviations that could explain the mismanaged development in the absence of unc-45.

Expression in developmental stages is altered in similarity to the RNAi-induced arrest

Having observed cliques with altered expression, we aimed at understanding, whether these expression changes are specific for one developmental transition occurring at the time point of arrest. We thus generated a time series of development ranging from embryo to late adult and compared the expression of all 307 cliques and in particular of those found relevant for unc-45 RNAi.

Striking differences were observed, when comparing the stages of each series (Supplemental Fig. 3), while differences between experiments of the same stage were small (Supplemental Figs. 4 and 5). Interestingly, also in these comparisons most of the isolated expression cliques showed coordinated expression differences, and also strong responses could be observed for the later developmental stages (Supplemental Fig. 6). In total more then 80% of the cliques show a statistically significant expression change during the development from embryo to 16 day adult and this also relates to most cliques found affected after unc-45 RNAi (Fig. 2d, 2 cliques and their development). While only few cliques were affected upon unc-45 RNAi treatment, hsp-90 RNAi is expected to yield a much stronger response.

Indeed a drop is observed in the expression of most upregulated cliques between L4 and day6 adult. In these cases the developmental delay may be the reason of the observed higher expression. A opposite pattern is observed for the downregulated gene cliques, with the exception of two cliques, which are not appropriately regulated: T05E12.6_12439-T05E12.6_12396 and gpd-3_977-aldo-1_21168, both of which appear to regulate metabolism.

Expression in developmental stages is altered in similarity to the hsp-90 RNAi-induced arrest

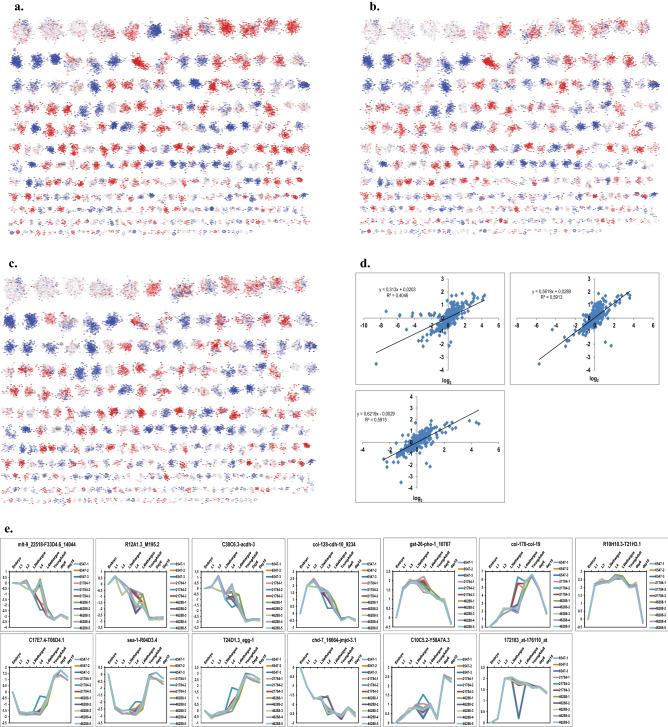

We next tested, whether also for the hsp-90 RNAi-treated nematodes developmental stages can be defined. The complexity of the differential expression between hsp-90 RNAi arrested nematodes and young adults allow to compare the obtained expression patterns with know patterns from larval development. We thus were interested to see, whether the full extent of the transcriptional changes can be explained by the observed developmental delay. Therefore we utilized publicly available microarray experiments on nematode development to help identify transcriptional units in the clique map that report on comparable steps during development. We employed microarray data from three experimental series (Table 4) and initially compared developmental transitions, showing similarity to the differences we observe in the RNAi-treated nematodes. These comparisons were L3/young adult, L4/young adult and L4let/young adult (Fig. 3a–c) as investigated in GSE46288/GSE4628928. Clearly similarities can be observed between the hsp-90 RNAi treated nematodes and the L4 larvae, when each of them is compared to the young adult control. In fact, most of the cliques correlate in color and correlation analysis shows a coefficient of determination with these data of 0.4046, 0.5913 and 0.5915 (Fig. 3d). Based on these values, hsp-90 RNAi-arrested nematodes best correspond to a L4-larval like state. Only few clear differences can be observed compared to L4 or L4-lethargus, while several cliques deviate from L3-like state. Judged from the few differences to L4 state, it might be that the chronological timing of the events during development is misaligned in hsp-90 RNAi-arrested nematodes.

Table 4.

Experiments used for the analysis of the developmental time line of C. elegans, obtained from the GEO expression data repository.

| Series | Sample | Description | Replicate |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSE6547 | GSM146422 | N2 worms at L1 stage | 1 |

| GSM146423 | N2 worms at L1 stage | 2 | |

| GSM147330 | N2 worms at L1 stage | 3 | |

| GSM147334 | N2 worms at L4 stage | 1 | |

| GSM147335 | N2 worms at L4 stage | 2 | |

| GSM147336 | N2 worms at L4 stage | 3 | |

| GSM147340 | N2 worms at embryonic stage | 1 | |

| GSM147341 | N2 worms at embryonic stage | 2 | |

| GSM147342 | N2 worms at embryonic stage | 3 | |

| GSE21784 | GSM542652 | L4 larvae | 1 |

| GSM542653 | L4 larvae | 2 | |

| GSM542654 | L4 larvae | 3 | |

| GSM542655 | Day 6 adult | 1 | |

| GSM542656 | Day 6 adult | 2 | |

| GSM542657 | Day 6 adult | 3 | |

| GSM542658 | Day 15 adult | 1 | |

| GSM542659 | Day 15 adult | 2 | |

| GSM542660 | Day 15 adult | 3 | |

| GSE46288 | GSM1128166 | L3 | 1 |

| GSM1128167 | L3 | 2 | |

| GSM1128168 | L3 | 3 | |

| GSM1128169 | L3-lethargus | 1 | |

| GSM1128170 | L3-lethargus | 2 | |

| GSM1128171 | L3-lethargus | 3 | |

| GSE46289 | GSM1128172 | L4 | 1 |

| GSM1128173 | L4 | 2 | |

| GSM1128174 | L4 | 3 | |

| GSM1128175 | L4 | 4 | |

| GSM1128176 | L4 | 5 | |

| GSM1128177 | L4-lethargus | 1 | |

| GSM1128178 | L4-lethargus | 2 | |

| GSM1128179 | L4-lethargus | 3 | |

| GSM1128180 | L4-lethargus | 4 | |

| GSM1128181 | L4-lethargus | 5 | |

| GSM1128182 | Adult | 1 | |

| GSM1128183 | Adult | 2 | |

| GSM1128184 | Adult | 3 | |

| GSM1128185 | Adult | 4 | |

| GSM1128186 | Adult | 5 |

Figure 3.

Expression in developmental stages is altered in similarity to the RNAi-induced arrest. (a) L3 comparison to young adult. (b) L4 comparison to young adult and (c) L4 lethargus to young adult. Other stepwise comparisons, like that of embryo to L1 or that of day6 nematode to day 16 adult nemtode are shown in the Supplemental Figures section as Supplemental Fig. 3, 4, 5 and 6. (d) Clique responses throughout development shown for selected cliques with significant change pattern. Cliques colored in red are induced compared to the earlier developmental stage, while cliques colored in blue are repressed. The linear regression function was generated with Microsoft Excel without weighting, a square value of 1 would indicate a perfect correlation between the cliques.

We further investigated, whether the expression behavior matches the known expression behavior during development and aging. To this end the cliques found relevant for hsp-90 RNAi were investigated throughout development. While the strongly responsive upregulated cliques col-138_col-49, abu-7_abu-8, R12E2.14_75-R12E2.15, col-117_col-167, pqn-54_abu-9, col-146_col-133 already were found in context with the unc-45 RNAi-arrested state (see Fig. 2d), further cliques are identificed as significantly upregulated in hsp-90 RNAi treated nematodes (Fig. 3e). As for unc-45 RNAi before the downregulated cliques vit-2_vit-4, C46C2.5_W03F11, ZC373.2-Y62H9A.6_1596, ZK1053.4-C08F1.6 were identified amid fbxc-28_sdz-28 (see Fig. 2d), plus additional ones not found significant before (Fig. 3e). Interestingly, in few cases, the directionality of the RNAi-induced response does not correlate with the expected behaviour during the arrested L4 state. This is evident for the cliques C17H1.6-C17H1.13, C32F10.4-D1086.2 and C10C5.2-Y58A7A.3.

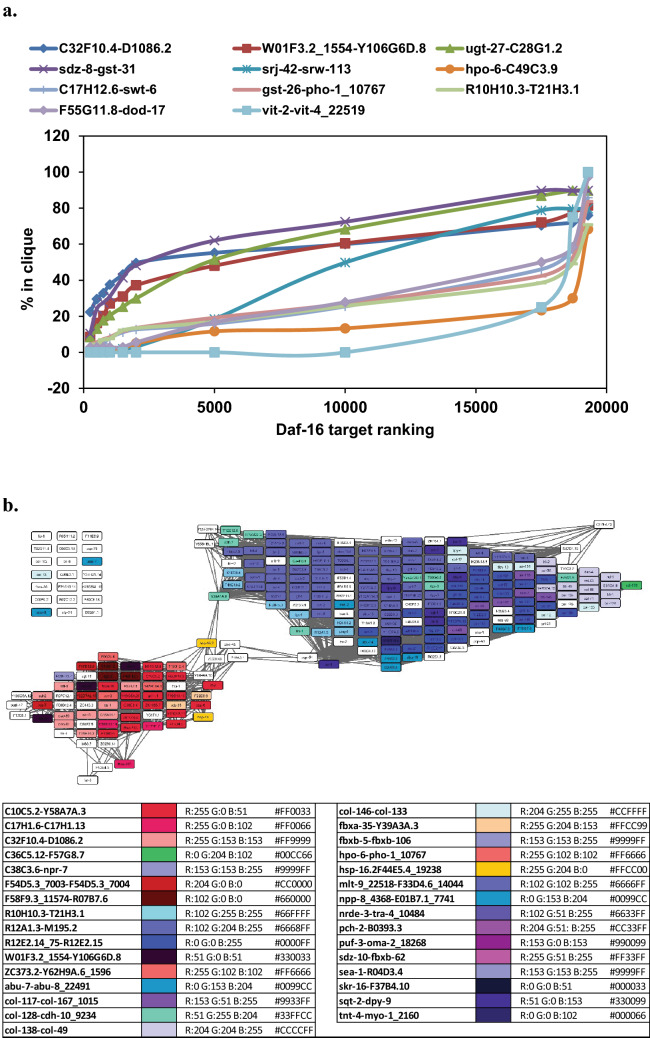

daf-16 target genes deviate from the developmental program in hsp-90 RNAi

We finally aimed at understanding the few cliques that deviate from the developmental progression and the explanation based on developmental delays. To this end we used the information gained previously that a fraction of the misregulated genes are daf-16 targets11. We tested, which of the cliques from the clique map contain daf-16 targets and then tested, whether those are regulated in coordance with developmental progress. Indeed, targets upregulated and suppressed by DAF-16 are enriched in several cliques (the 15 most prominent shown in Table 5, more information in Fig. 4a and b). Comparing the clusters identified in Eckl et al. (2017), with the current cliques we also observe a clear enrichment among several of the 307 cliques (Table 5). As spectulated in Eckl et al., among the cluster “Up1” there are many genes, which are regulated by DAF-16, while cluster “Up2” does not enrich daf-16 targets (Table 5). Mapping all cliques onto the network developed in Eckl et al. the enrichment of these cliques in certain parts of the network becomes evident. For the downregulated genes, also DAF-16 enriching cliques are among those containing these genes11. Therefore, especially among the upregulated genes, cliques are present, which contain an elevated level of daf-16 target genes.

Table 5.

HSP-90-responsive cliques with highest enrichment of daf-16 supported (red) and suppressed (blue) genes.

| Up1 | Up2 | Down1 | Down2 | Down3 | Down4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C10C5.2-Y58A7A.3 | col-138-col-49 | C46C2.5_15926-W03F11.1 | C17E7.4-T06D4.1 | vit-2-vit-4_22519 | C17H12.6-swt-6 |

| K08D10.9-F46A8.1 | R12E2.14_75-R12E2.15 | ZC373.2-Y62H9A.6_1596 | fbxc-28-sdz-28 | C10A4.6-C01A2.6 | F55G11.8-dod-17 |

| hsp-16.2-F44E5.4_19238 | mlt-9_22518-F33D4.6_14044 | C10C5.3-C10C5.5 | sea-1-R04D3.4 | fbxc-28-sdz-28 | R10H10.3-T21H3.1 |

| lys-3-tsp-1 | col-117-col-167_1015 | 171971_x_at-D1054.11_184 | ZK1053.4-C08F1.6 | C17E7.4-T06D4.1 | |

| hpo-6-C49C3.9 | col-146-col-133 | C46C2.5_15925-F17E9.2 | F11A3.2-F47G3.3 | R07E4.5-skp-1_1608 | |

| C32F10.4-D1086.2 | bus-8_3160-K04H4.2_2324 | C03B1.14-F46C3.2 | K09D9.12-T10C6.10 | R10H10.3-T21H3.1 | |

| F13E6.1_2090-C35C5.3_1843 | sqt-2-dpy-9 | col-178-col-19 | K05C4.4-fbxc-46 | sre-33-ZK1025.1_8337 | |

| Y6G8.2_5650-F17B5.1 | abu-7-abu-8_22491 | T24D1.3-egg-1 | fbxb-31-fbxb-119 | ||

| fbxa-35-Y39A3A.3 | agmo-1_5527-F53B1.4 | Y116A8C.19-F38C2.7 | |||

| C17H1.6-C17H1.13 | dos-2-grd-2 | npp-8_4368-E01B7.1_7741 | |||

| ccg-1_12351-ZC410.5 | R12A1.3-M195.2 | sdz-10-fbxb-62 | |||

| C17H12.6-swt-6 | pqn-54-abu-9 | fbxb-13-fbxb-24 | |||

| F58F9.3_11574-R07B7.6 | col-128-cdh-10_9234 | skr-16-F37B4.10 | |||

| T12G3.1_17-T12G3.1_18846 | C38C6.3-acdh-6 | dsh-1_3575-C40A11.4 | |||

| W01F3.2_1554-Y106G6D.8 | C36C5.12-F57G8.7 | dos-2-grd-2 |

Sorted according to the nomenclature estabilshed in Eckl et al., 2017, which grouped the hsp-90 responsive genes in two major groups for upregulation and four groups for downregulation based on co-expression network analysis. Cliques enriched within these groups are listed under the group names (Up1, Up2, Down1, Down2, Down3 and Down4). The groups are labeled in bold, if enrichment reaches the significance level of 1e-5 and they are colored, if the same group is found within the top daf-16 regulated groups. Coloring is red, if it is among upregulated DAF-16 targets and blue if, it is among down regulated DAF-16 targets.

Figure 4.

Correlation between daf-16 target genes and identified cliques for those genes most clearly enriched in daf-16 targets. (a) Enrichted target cliques of DAF-16. The plot shows how many genes per clique are derived from the indicated range of the DAF-16 ranking. Cliques with high percentage values on the left side reflect cliques that are considered to be DAF-16 activatable while cliques with a low percentage up to the bottom to the DAF-16 ranking are considered repressed. (b) Most strongly enriched cliques in the Top750 and Bottom750 of the ranked daf-16 target list.

Interestingly, these cliques are upregulated despite their developmental program, which aims for downregulation. Thus, the presence of these cliques suggests a simultaneous modification to the dauer-program outside the developmental program after hsp-90 RNAi induced growth arrest.

Discussion

In this study, we analysed microarray data from C. elegans based on preformed coregulated expression cliques. This approach has been applied successfully in the yeast model organism by us17, but the applicability of this method to multicellular organisms has not been clear. We thus used the algorithms developed for yeast to also generate high quality coexpression cliques from nematode expression data and then validated them by GO-term enrichment, phenotype enrichment and tissue enrichment and by selective clique responses in individual microarray experiments. Based on our data from the developmental process of C. elegans, we believe that this analysis method could have broader use in the analysis of gene expression data from nematodes. This is evident from the correlated responses of cliques during nematode developmental transitions.

Recently also a different approach was reported to utilize genome-wide co-expression cliques for C. elegans29. In contrast to our appraoch, in this study an individual gene could be assigned to multiple cliques (on average 3) and also negative correlation was included. This makes the construction of a static clique map as used by us more difficult, but may include details missed by our approach. Both approaches will have their advantages. In the method described by us, we focus on the strongest connection and blank out those that might be secondary based on numbers, but still achieve very high levels of correlation with GO-terms, phenotypes and tissue specificity for most of the cliques.

One way to use the cliques could be by employing the popular GSEA platform30, where our cliques can be either used as a single input file covering the whole genome or as part of the global collection of gene sets. Another way to use the cliques can also be via the clusterEX.de webserver that we have set up and will further develop for the purpose of gene expression analysis based on known co-expression relationships. It therefore will be interesting to see, how further useful applications will be developed based on these predefined gene sets.

Integrating unc-45 into the developmental time line exposes distinct cliques for develeopmental stop

We first analysed unc-45 depleted nematodes. In these nematodes, the depletion of unc-45 leads to developmental arrest and paralysis in almost adult animals. Here the comparison with the young adult nematode shows that certain cliques are misregulated and some of those cliques also represent developmental marker cliques as suggested by our evaluation procedure. These marker genes help to map the developmental status of the unc-45 depleted organisms. Clearly unc-45 depleted nematodes are close to N2 nematodes in this approach, but defined changes in certain genes help to map the events that did not unfold during development.

To evaluate the disruption of vulva development, we individually tested the genes transcriptionally regulated during this process and their specific regulation (Table 3): eff-1 (log2(dExp) = 0.185), egl-18 (− 0.035), egl-17 (0.000), lin-3 (− 0.015), lin-31 (0.00), lin-39 (0.00), egl-30 (0.02), lag-2 (− 0.09), apx-1 (0.055), dsl-1 (− 0.085 as part of fbxc-28-sdz-28) and elt-6 (-0.065), all of which are getting induced during vulva development31. In a critical step during vulva development the VPCs express LIN-39, which together with its cofactors CEH-20 and UNC-62, activates the expression of ref-2, which inhibits the expression of the fusogen EFF-132). In UNC-45 depleted nematodes, ref-2 is not yet upregulated compared to mock treated nematodes (− 0.675 and resides in clique cfz-2_18944-cfz-2_2268, which is downregulated twice significantly, but not very strongly) and also ref-1 is lower expressed in unc-45 RNAi-treated nematodes (− 0.46, ZK1053.4-C08F1.6), even though lin-39 is expressed as in the control and eff-1 is higher expressed (0.185, tnt-4-myo-1_2160), as expected for vulva development33. Thus, based on these expression patterns the induction to generate the vulva is not transmitted properly by the anchor cell from the developing gonad. Also lin-12 (− 0.31, sol-1-jnk-1_18695), cwn-1 (− 0.26, chd-7_16664-jmjd-3.1) and vang-1 (− 0.175, nrde-3-tra-4_10484) are downregulated, further implying that central decisions to induce the vulva have not been made yet.

Table 3.

Most strongly affected cliques by unc-45 RNAi and their characteristics.

| Cluster name | Clique position | Best GO-Term | Best PEA-Term | Best TEA-Term | Mean STD | Log10(p) Exp 1 | Log10(p) Exp 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nspd-1-nspd-2 | R12 C1 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005751_570 | 0.38 ± 0.12 | 4.41 | 1.84 |

| msp-36-msp-55 | R10 C19 | Lipid storage GO:0019915 | Linker cell migration variant WBPhenotype:0001511 | WBPaper00040420_FLP_enriched_WBbt_0006828_288 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 1.15 | 2.54 |

| msp-63-msp-33 | R9 C14 | Lipid storage GO:0019915 | Linker cell migration variant WBPhenotype:0001511 | WBPaper00040420_FLP_enriched_WBbt_0006828_288 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 7.92 | 9.08 |

| hsp-16.2-F44E5.4_19238 | R12 C4 | Response to heat GO:0009408 | Cadmium response variant WBPhenotype:0001653 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.29 ± 0.17 | 16.49 | 1.60 |

| abu-7-abu-8_22491 | R8 C26 | Response to unfolded protein GO:0006986 | Dauer constitutive WBPhenotype:0000012 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 63.31 | 5.15 |

| col-138-col-49 | R9 C23 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Blistered WBPhenotype:0000025 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.24 ± 0.22 | 34.90 | 0.93 |

| col-117-col-167_1015 | R9 C25 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 29.40 | 5.29 |

| pqn-54-abu-9 | R6 C11 | Response to unfolded protein GO:0006986 | Shortened life span WBPhenotype:0001171 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 43.57 | 13.10 |

| R12E2.14_75-R12E2.15 | R6 C9 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_germline-precursors_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006849_974 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 47.12 | 8.99 |

| lys-3-tsp-1 | R11 C40 | Carbohydrate metabolic process GO:0005975 | Male nervous system development variant WBPhenotype:0001008 | WBPaper00040420_ALM_PLM_enriched_WBbt_0005406_198 | 0.18 ± 0.22 | 27.93 | 1.06 |

| C10C5.3-C10C5.5 | R12 C40 | Oxoacid metabolic process GO:0043436 | Dauer constitutive WBPhenotype:0000012 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 4.43 | 2.28 |

| F07A5.2-R10E9.2 | R5 C7 | Sodium ion transport GO:0006814 | Nicotine response variant WBPhenotype:0001573 | WBPaper00045521_Spermatogenic_WBbt_0005784_2743 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 6.82 | 34.38 |

| K11C4.1_20445-rnh-1.1 | R8 C22 | Regulation of cell shape GO:0008360 | Fat content increased WBPhenotype:0001184 | WBPaper00045521_Spermatogenic_WBbt_0005784_2743 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 6.02 | 8.77 |

| ssq-2_16507-ssq-3_1032 | R12 C27 | Response to hormone GO:0009725 | Movement variant WBPhenotype:0001206 | WBPaper00026980_intestine_enriched_WBbt_0005772_1970 | 0.13 ± 0 | 1.96 | 2.06 |

| col-146-col-133 | R9 C28 | Structural constituent of cuticle GO:0042302 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 11.00 | 2.77 |

| F42A9.7-T22B3.3 | R3 C11 | Regulation of cell shape GO:0008360 | Dauer metabolism variant WBPhenotype:0001547 | WBPaper00045521_Spermatogenic_WBbt_0005784_2743 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 7.97 | 29.43 |

| bus-8_3160-K04H4.2_2324 | R9 C2 | Amino sugar metabolic process GO:0006040 | Molt variant WBPhenotype:0002041 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 0.11 ± 0.08 | 8.94 | 0.92 |

| R12A1.3-M195.2 | R6 C19 | Amino sugar metabolic process GO:0006040 | Dauer constitutive WBPhenotype:0000012 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 6.65 | 3.63 |

| T28A11.5-T06C12.14 | R12 C14 | Extracellular region GO:0005576 | Dumpy WBPhenotype:0000583 | WBPaper00037950_excretory-cell_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005812_528 | 0.1 ± 0.05 | 0.71 | 2.01 |

| agmo-1_5527-F53B1.4 | R10 C14 | Pyridoxal phosphate binding GO:0030170 | Molt variant WBPhenotype:0002041 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | 0.1 ± 0.11 | 7.44 | 0.70 |

| 171971_x_at-D1054.11_184 | R11 C37 | Cell GO:0005623 | Egg laying defective WBPhenotype:0000006 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005733_1250 | − 0.55 ± 0.09 | 3.70 | 0.66 |

| gpd-3_977-aldo-1_21168 | R9 C26 | Glycosyl compound metabolic process GO:1901657 | Fat content reduced WBPhenotype:0001183 | WBPaper00031003_24hr_muscle_enriched_WBbt_0003675_918 | − 0.51 ± 0.01 | 9.02 | 4.52 |

| T05E12.6_12439-T05E12.6_12396 | R10 C3 | Lipid catabolic process GO:0016042 | Transgene expression increased WBPhenotype:0001236 | WBPaper00037950_pharyngeal-muscle_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005451_598 | − 0.29 ± 0.15 | 60.37 | 3.63 |

| ZK1053.4-C08F1.6 | R4 C16 | Embryo development GO:0009790 | Embryonic development variant WBPhenotype:0000749 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | − 0.26 ± 0.12 | 26.51 | 73.26 |

| C46C2.5_15926-W03F11.1 | R9 C22 | Carbohydrate binding GO:0030246 | Apoptosis increased WBPhenotype:0000183 | WBPaper00037950_GABAergic-motor-neurons_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005190_361 | − 0.24 ± 0.02 | 8.57 | 10.00 |

| ZC373.2-Y62H9A.6_1596 | R3 C18 | Flavonoid metabolic process GO:0009812 | Cell membrane organization biogenesis variant WBPhenotype:0001982 | WBPaper00037950_dopaminergic-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0006746_1230 | − 0.22 ± 0.03 | 46.68 | 19.54 |

| nspc-1_614-nspc-10_22525 | R10 C12 | Extracellular region GO:0005576 | Spermatogenesis variant WBPhenotype:0000670 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | − 0.21 ± 0.06 | 5.62 | 5.79 |

| C46C2.5_15925-F17E9.2 | R10 C8 | Hydrolase activity—acting on glycosyl bonds GO:0016798 | Embryonic development variant WBPhenotype:0000749 | WBPaper00037950_coelomocytes_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005751_229 | − 0.2 ± 0.01 | 6.65 | 6.25 |

| C03B1.14-F46C3.2 | R8 C21 | Membrane GO:0016020 | Chemical hypersensitive WBPhenotype:0001918 | WBPaper00037950_intestine_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005772_946 | − 0.19 ± 0 | 9.53 | 10.38 |

| fbxc-28-sdz-28 | R7 C8 | Modification-dependent macromolecule catabolic process GO:0043632 | L1 larval development variant WBPhenotype:0000751 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | − 0.18 ± 0.08 | 10.65 | 27.90 |

| fbxb-13-fbxb-24 | R8 C18 | Protein oligomerization GO:0051259 | Cholinergic agonist resistant WBPhenotype:0001578 | WBPaper00024505_pharyngeal_enriched_WBbt_0003681_329 | − 0.17 ± 0.1 | 1.20 | 13.08 |

| dsh-1_3575-C40A11.4 | R5 C17 | Protein oligomerization GO:0051259 | Ectopic expression transgene WBPhenotype:0001276 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | − 0.14 ± 0.07 | 2.78 | 9.72 |

| vem-1-ugt-58 | R12 C35 | Oxoacid metabolic process GO:0043436 | Epithelial cell physiology variant WBPhenotype:0000986 | WBPaper00037950_BAG-neuron_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0006825_454 | − 0.14 ± 0.01 | 2.03 | 0.89 |

| sdz-10-fbxb-62 | R3 C17 | Glycosylation GO:0070085 | L1 larval development variant WBPhenotype:0000751 | WBPaper00037950_hypodermis_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005733_734 | − 0.14 ± 0.09 | 2.82 | 41.16 |

| Y41D4B.17-K10D11.6 | R12 C32 | Immune system process GO:0002376 | Exploded through vulva WBPhenotype:0000038 | WBPaper00037950_intestine_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005772_946 | − 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.77 |

| fbxb-31-fbxb-119 | R11 C28 | Embryo development GO:0009790 | Transgene expression reduced WBPhenotype:0001278 | WBPaper00040420_FLP_enriched_WBbt_0006828_288 | − 0.12 ± 0.09 | 0.64 | 4.30 |

| R03E1.2_7363-ucr-2.1 | R10 C30 | Mitochondrion GO:0005739 | mRNA levels increased WBPhenotype:0000136 | WBPaper00037950_excretory-cell_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005812_528 | − 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.98 | 2.14 |

| C35C5.8_15869-best-1 | R10 C21 | Transmembrane transport GO:0055085 | Fat content increased WBPhenotype:0001184 | WBPaper00037950_excretory-cell_larva_enriched_WBbt_0005812_528 | − 0.12 ± 0.03 | 4.11 | 1.04 |

| pek-1_22220-pek-1_33 | R11 C12 | Aging GO:0007568 | Sluggish WBPhenotype:0000646 | WBPaper00037950_GABAergic-motor-neurons_embryo_enriched_WBbt_0005190_361 | − 0.11 ± 0 | 1.85 | 1.69 |

| iff-2_18754-rpl-25.1 | R12 C37 | Amide biosynthetic process GO:0043604 | Hermaphrodite fertility reduced WBPhenotype:0001259 | WBPaper00037950_PVD-OLL-neurons_larva_enriched_WBbt_0006831_878 | − 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.65 | 1.39 |

Clique positions (letter = row, number = position from left to right) correspond to the clique map shown in Fig. 2b.

Regarding the germline, asb-2 is reduced (− 0.21, tars-1-AFFX-r2-3026-5_at) and the nspd-proteins are still upregulated together with msp-proteins (Fig. 2d34), implying that sperm development is not completed yet, while the expression of the upstream regulators spn-4 and neg-135 is at the same level as in the normally developed adult. Also the regulators of msp-expression set-17 and csr-1 are expressed at the level of the control nematodes36, implying that sperm-development is almost finished37,38.

Integrating hsp-90 into the time line data exposes defined clusters for developmental stop

We used this clique map to also analyse the depletion of hsp-90. While depletion of hsp-90 leads to developmental arrest and reduced motility in late larval stages, it also leads to defined transcriptional changes. To analyse the causes, we performed microarray experiments under wildtype conditions and under conditions, where the chaperone is depleted. Based on the clique analysis, it is obvious that certain developmental milestones are not reached yet in the HSP-90 depleted animals. Based on this analysis these nemtodes arrest in a late larval stage with additional misregulation of DAF-16 target genes.

Previously it had been observed that the Top300 genes from the hsp-90 RNAi analysis showed partial overlap with daf-16 regulated genes. We thus employed the gene-list from this previous study to identify the cliques, which now represent these genes. Indeed the correlation is fairly clear, with the cliques C17H1.6-C17H1.13, C32F10.4-D1086.2 and C10C5.2-Y58A7A.3 being mostly overlapping with the previous cluster1_up and the cliques col-138-col-49, R12E2.14_75-R12E2.15, mlt-9_22518-F33D4.6_14044 being mostly overlapping with the cluster2_up. Utilizing the ranked list of daf-16 target genes, we also determined which cliques most strongly are enriched in the Top750 and Bottom750 of this ranked list. These cliques are found mostly in cluster1_up confirming that the identification of this correlation also is visible from the clique map. Interestingly these cliques represent those that are differently regulated compared to the L4 larval stage. Thus the HSP-90 depletion leads to higher exression levles in a daf-16 regulated cluster (cluster1_up) and a daf-16 independent cluster (cluster2_up). With the daf-16 independent cluster containing mostly cliques related to larval development, apparently the depletion of HSP-90 induces both of these processes. Whether they are connected via secondary effects is unclear to date, especially as the developmental timing of DAF-16 activity is a well described phenomenon.

Thus, based on several clearly regulated marker cliques, hsp-90 arrested nematodes, like unc-45 arrested nematodes, can be positioned in respect to a developmental time axis.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for funding the research grant RI1873/1-4 and the Heisenberg position RI1873/5-1. We also thank the distributors of free and open source software that we could use during this study. This includes Cytoscape (Cytoscape Consortium), RMAexpress (Ben Bolstad) and Transcriptome Analysis Console (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Author contributions

L.S. and K.R. designed the experiments. L.S. performed the experiments. L.S. and K.R. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

All data will be made fully available without restriction at http://www.richterlab.de/DataSets and on the GEO repository. Tables containing GO terms, PEA and TEA enrichment results for all cliques can be obtained from the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-91690-6.

References

- 1.Somogyvari M, Gecse E, Soti C. DAF-21/Hsp90 is required for C. elegans longevity by ensuring DAF-16/FOXO isoform A function. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12048. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inoue T, et al. Cell cycle control by daf-21/Hsp90 at the first meiotic prophase/metaphase boundary during oogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Growth Differ. 2006;48:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillan V, Maitland K, McCormack G, Him NA, Devaney E. Functional genomics of hsp-90 in parasitic and free-living nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009;39:1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClellan AJ, et al. Diverse cellular functions of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone uncovered using systems approaches. Cell. 2007;131:121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan DF, Lindquist S. Mutational analysis of Hsp90 function: interactions with a steroid receptor and a protein kinase. Mol. Cell Biol. 1995;15:3917–3925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt WB, Toft DO. Regulation of signaling protein function and trafficking by the hsp90/hsp70-based chaperone machinery. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2003;228:111–133. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaiser AM, Kaiser CJ, Haslbeck V, Richter K. Downregulation of the Hsp90 system causes defects in muscle cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roe SM, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the Hsp90 molecular chaperone by the antitumor antibiotics radicicol and geldanamycin. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:260–266. doi: 10.1021/jm980403y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sreedhar AS, Kalmar E, Csermely P, Shen YF. Hsp90 isoforms: functions, expression and clinical importance. FEBS Lett. 2004;562:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(04)00229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picard D. Heat-shock protein 90, a chaperone for folding and regulation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:1640–1648. doi: 10.1007/pl00012491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckl J, Sima S, Marcus K, Lindemann C, Richter K. Hsp90-downregulation influences the heat-shock response, innate immune response and onset of oocyte development in nematodes. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0186389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prithika U, Deepa V, Balamurugan K. External induction of heat shock stimulates the immune response and longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans towards pathogen exposure. Innate. Immun. 2016;22:466–478. doi: 10.1177/1753425916654557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barral JM, Hutagalung AH, Brinker A, Hartl FU, Epstein HF. Role of the myosin assembly protein UNC-45 as a molecular chaperone for myosin. Science. 2002;295:669–671. doi: 10.1126/science.1066648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L, Srikakulam R, Winkelmann DA. Unc45 activates Hsp90-dependent folding of the myosin motor domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:13185–13193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800757200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kachur T, Ao W, Berger J, Pilgrim D. Maternal UNC-45 is involved in cytokinesis and colocalizes with non-muscle myosin in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5313–5321. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao S, Fung-Leung WP, Bittner A, Ngo K, Liu X. Comparison of RNA-Seq and microarray in transcriptome profiling of activated T cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e78684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sima S, Schmauder L, Richter K. Genome-wide analysis of yeast expression data based on a priori generated co-regulation cliques. Microb. Cell. 2019;6:160–176. doi: 10.15698/mic2019.03.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucl. Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papsdorf K, Sima S, Richter G, Richter K. Construction and evaluation of yeast expression networks by database-guided predictions. Microb Cell. 2016;3:236–247. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.06.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angeles-Albores D, Lee RY, Chan J, Sternberg PW. Tissue enrichment analysis for C. elegans genomics. BMC Bioinform. 2016;17:366. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1229-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angeles-Albores D, Lee R, Chan J, Sternberg P. Two new functions in the WormBase Enrichment Suite. MicroPubl. Biol. 2018 doi: 10.17912/W25Q2N. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirienko NV, Fay DS. Transcriptome profiling of the C. elegans Rb ortholog reveals diverse developmental roles. Dev. Biol. 2007;305:674–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Youngman MJ, Rogers ZN, Kim DH. A decline in p38 MAPK signaling underlies immunosenescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.George-Raizen JB, Shockley KR, Trojanowski NF, Lamb AL, Raizen DM. Dynamically-expressed prion-like proteins form a cuticle in the pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biol. Open. 2014;3:1139–1149. doi: 10.1242/bio.20147500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaiser AM, Brandt F, Richter K. The non-canonical Hop protein from Caenorhabditis elegans exerts essential functions and forms binary complexes with either Hsc70 or Hsp90. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;391:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trojanowski NF, Nelson MD, Flavell SW, Fang-Yen C, Raizen DM. Distinct mechanisms underlie quiescence during two caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like states. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:14571–14584. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1369-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cary M, Podshivalova K, Kenyon C. Application of transcriptional gene modules to analysis of caenorhabditis elegans' gene expression data. G3 (Bethesda) 2020;10:3623–3638. doi: 10.1534/g3.120.401270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sternberg PW. Vulval development. WormBook. 2005 doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.6.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinstein N, Mendoza L. A network model for the specification of vulval precursor cells and cell fusion control in Caenorhabditis elegans. Front. Genet. 2013;4:112. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shemer G, Podbilewicz B. LIN-39/Hox triggers cell division and represses EFF-1/fusogen-dependent vulval cell fusion. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3136–3141. doi: 10.1101/gad.251202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma X, et al. Characterisation of Caenorhabditis elegans sperm transcriptome and proteome. BMC Genom. 2014;15:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsukamoto T, et al. LIN-41 and OMA ribonucleoprotein complexes mediate a translational repression-to-activation switch controlling oocyte meiotic maturation and the oocyte-to-embryo transition in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2017;206:2007–2039. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.203174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engert CG, Droste R, van Oudenaarden A, Horvitz HR. A Caenorhabditis elegans protein with a PRDM9-like SET domain localizes to chromatin-associated foci and promotes spermatocyte gene expression, sperm production and fertility. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaMunyon CW, et al. A new player in the spermiogenesis pathway of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2015;201:1103–1116. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.181172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell AC, Updike DL. CSR-1 and P granules suppress sperm-specific transcription in the C. elegans germline. Development. 2015;142:1745–1755. doi: 10.1242/dev.121434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data will be made fully available without restriction at http://www.richterlab.de/DataSets and on the GEO repository. Tables containing GO terms, PEA and TEA enrichment results for all cliques can be obtained from the authors.