Abstract

The underrepresentation of African American (AA) participants in medical research perpetuates racial health disparities in the United States. Open-ended phone interviews were conducted with 50 AA adults from Philadelphia who had previously participated in a genetic study of glaucoma that included complimentary ophthalmic screenings. Recruitment for the genetic study was done in partnership with a Black-owned radio station. Thematic analysis of interview transcripts, guided by the integrated behavior model (IBM), identified self-reported motivations for participating in this care-focused and community-promoted research program. Findings revealed that decisions to enroll were influenced by strong instrumental attitudes regarding learning more about personal health and contributing to future care options for others. Notable normative influences that factored into participants’ decisions to enroll in the study included hearing about the study from a respected community media outlet, friends, and family. About one-third of respondents discussed past and current racial discrimination in medical research as an important sociocultural frame within which they thought about participation, suggesting that experiential attitudes play a continuing role in AA’s decisions to enroll in medical research studies. Medical researchers seeking to recruit AA participants should collaborate with community partners, combine enrollment opportunities with access to health services, and emphasize the potential for new research to mitigate racial inequalities.

Keywords: study recruitment, community-based research, health disparities, Black/African American, integrated behavioral model

Introduction

The well-documented underrepresentation of African American (AA) individuals in medical research, and the inequity of this group’s access to quality medical care, contribute to persisting racial health disparities in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2017). Individuals of European ancestry make up 81% of participants in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted worldwide, while those of African descent make up a mere 2% (Sirugo et al., 2019). The exclusion of AAs, a genetically diverse population, from genomic studies hinders scientific understanding of disease and the development of appropriate diagnosis and treatment options for Black patients (Haga, 2010; Popejoy & Fullerton, 2016; Sirugo et al., 2019). Health researchers have a responsibility to better understand factors that contribute to the under-representation of over affected minorities in health research. One particular area that may be ripe for intervention is the participant recruitment process.

Literature Review

Due to a long history of exploitation of Black patients as research subjects, distrust in medical research has been cited as a barrier to AA study participation (Gamble, 1993; Hussain-Gambles et al., 2004). Previous survey and focus group studies have shown that historical cases of exploitation, such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (Brandt, 1978) and the story of Henrietta Lacks (Skloot, 2011), as well as current institutionalized racism, have contributed to distrust of medical research in the AA community (Bates & Harris, 2004; Gamble, 1993; Hussain-Gambles et al. 2004; Lee et al., 2018). Distrust may be connected to fears of being treated as a “guinea pig” and concerns about privacy violations or exploitation of personal information (Erwin et al., 2013; Luque et al., 2012). Overall, there are serious and persistent concerns within the AA community about medical research.

There is conflicting literature examining how these reservations influence research participation. For example, McDonald et al. (2014) found that distrust of medical research was associated with lower intention to donate biobank specimens and Parikh et al. (2019) found discomfort around sharing genetic information among Black ophthalmology patients was connected to declining to participate in a genetic study. However, other studies have indicated that, while historical cases of exploitation and present-day systemic racism may contribute to skepticism of medical research, this does not sufficiently explain the low rates of AA study participation (Scherr et al., 2019).

Awareness of historical mistreatment of AA patients may increase desire to participate in ethical research focused on mitigating racial disparities. Bates and Harris (2004) and Cohn et al. (2014) found Black focus group participants mentioned Tuskegee and Henrietta Lacks when describing a need for change in research conduct, rather than viewing these cases as deterrents for participation. Ridley-Merriweather and Head (2017) found that AA women who donated to a breast tissue biobank viewed donating as an opportunity to mitigate the history of racial discrimination and disparities in medicine, and directly benefit other Black women. According to several additional studies, a primary motivator for AA participation is the potential for medical research to improve care for the Black community, even when distrust remains in the medical research establishment at large (Hagiwara et al., 2013; Goldenberg et al., 2011; Walker et al., 2014).

A recurring finding in minority recruitment literature is that the greatest barrier to enrollment is a lack of opportunity to participate (Cain et al., 2015; Hagiwara et al., 2013; Scherr et al., 2019). This means outreach by medical researchers is perhaps the most crucial step toward inclusive research. Efforts to increase access to medical research studies for AA individuals, particularly through building community partnerships, communicating through community channels, and providing adequate logistic support and compensation, are imperative to increasing participation rates (Jones et al., 2017; McDonald et al., 2012, 2014; Ochs-Balcom et al., 2015; Skinner et al., 2015). These prior studies highlight an opportunity for medical research recruitment efforts to not only rebuild trust, but to do so in a way that increases access to care.

The POAAGG medical genetic study and recruitment campaign

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is one hereditary disease that disproportionately affects Black individuals (Pleet et al., 2016). POAG causes progressive vision loss, has no known cure, and manifests differently across and between populations. Most genetic variants associated with POAG in European Americans have not been replicated in the genetically diverse AA population (Campbell & Tishkoff, 2008; Hoffmann et al., 2014). The Primary Open-Angle African American Glaucoma Genetics (POAAGG) Study is a National Eye Institute-funded GWAS initiative run by the University of Pennsylvania that seeks to identify genetic variants associated with POAG in individuals of African descent. This genetic study recruited over 10,200 Black participants over eight years (07/2010–09/2018). The majority of participants were patients in ophthalmology clinics associated with the study and enrolled during regular clinical appointments.

To expand the opportunity to participate in the POAAGG Study and to offer specialized glaucoma care to more AAs in Philadelphia, study recruiters partnered with Black community leaders to run a recruitment campaign from 1/30/2018 to 6/30/2018. The target audience was self-identified Black individuals (including Black American, AA, African descent, and African Caribbean), aged 35 years or older, with or at risk of glaucoma. [See Charlson et al. (2015) for full genetic study eligibility criteria.] The recruitment campaign aimed to increase community awareness about glaucoma, provide access to fellowship-trained glaucoma specialists for free second opinions and diagnostic screenings, and enroll eligible individuals into the genetic study. Campaign messages included print flyers distributed throughout the city and a series of commercials and interviews aired on WURD Radio (WURD Radio, n.d.).

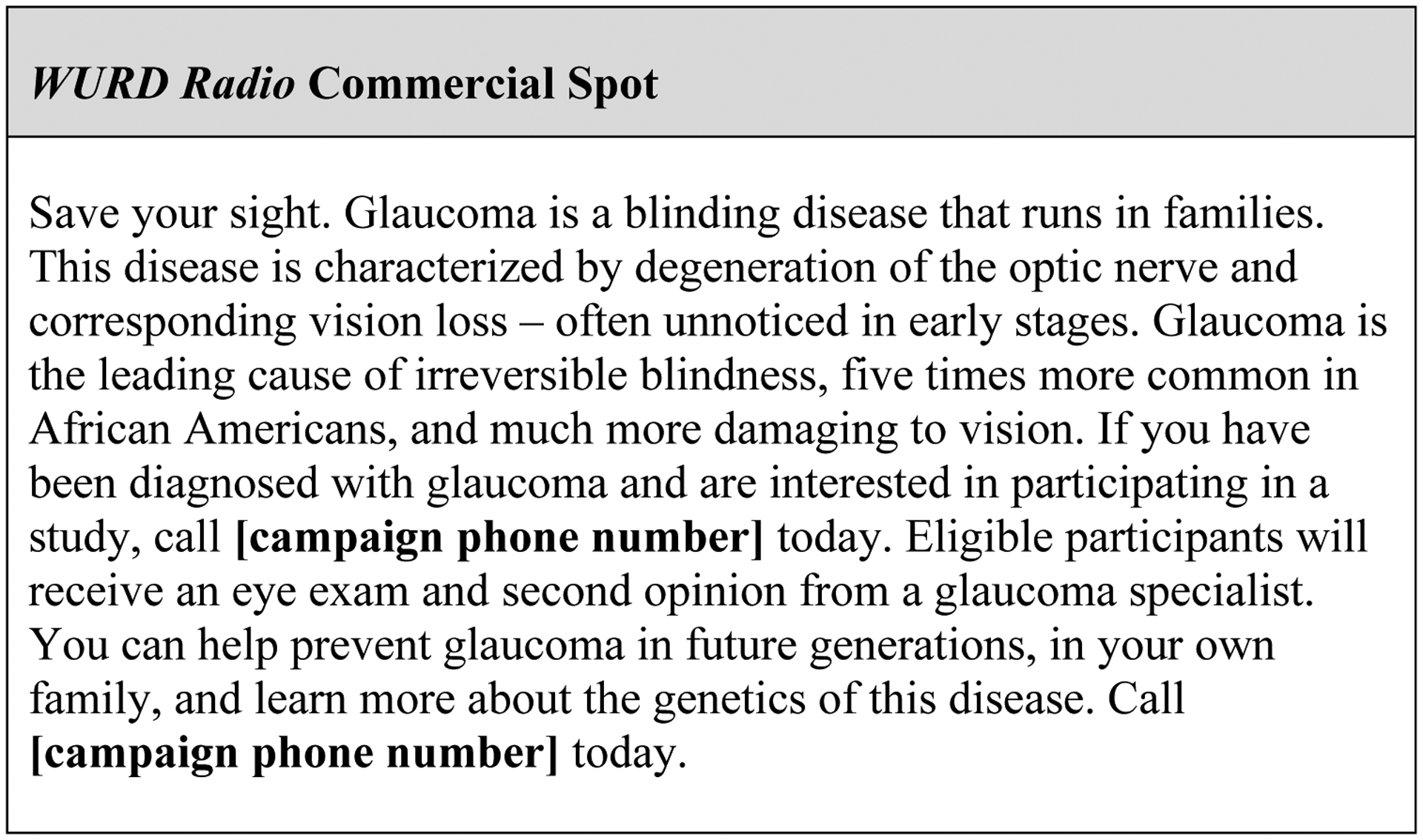

Founded by an African American physician in 2002, WURD is a Black-owned media company in Pennsylvania. WURD covers a variety of issues (ranging from politics to pop culture) through talk radio, social media, and digital media and frequently supports health-related events serving the AA community (WURD Radio, n.d.). WURD program hosts read advertisements, hosted live coverage of a screening event, and interviewed Black glaucoma specialists associated with the POAAGG Study (WURD Radio, n.d.). As exemplified in Figure 1, campaign messages emphasized individual and community benefits of participation in the research program and directed interested individuals to a campaign phone line. Campaign messaging and recruitment strategies are further detailed by Kikut et al. (2020).

Figure 1.

Example genetic study recruitment campaign message

This commercial script was read and recorded by one African American male and one African American female WURD program host. Recordings aired on WURD ~10x/day from 01/31/2018—06/30/2018.

To encourage screening attendance and research enrollment, POAAGG recruiters sought to increase access to clinics, screening events, and logistic support. All individuals who called the campaign phone line were either scheduled for exams with glaucoma physicians in-house or provided with information about upcoming screening events. During the campaign, volunteer physicians and study staff members hosted two Saturday screening events at a church and senior center in different areas of the city. Glaucoma exams, as well as lunch, taxi vouchers, and parking vouchers, were offered to all appointment and event attendees regardless of their decision to participate in the study. The recruitment campaign resulted in 62 additional participants enrolling in the genetic study in five months (Kikut et al., 2020). The POAAGG Study was the first research team to track and report outcomes directly resulting from a health-related WURD-partnership.

Messages: emphasizing outcomes for participant, family, and Black community

Previous studies have shown that benefits to health (Brewer et al., 2014) and the potential to help family and community members (McDonald et al., 2012; Scherr et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2014) are important motivations for research participation in the Black community. The community recruitment campaign for the POAAGG Study mentioned the availability of free screenings and emphasized the importance of early diagnoses (e.g. “[Glaucoma] is characterized by degeneration of the optic nerve and corresponding vision loss – often unnoticed in early stages”) and specialized care. Messages also emphasized that glaucoma is familial (“Glaucoma is a blinding disease that runs in families”) and prevalent in the Black community (“Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness, five times more common in AAs, and much more damaging to vision” [compared to individuals of predominantly European descent]) and that participating in the genetic study could help at-risk family and community members (“You can help prevent glaucoma in future generations in your own family”).

Messengers: normative influences in the Black community

Previous work has also demonstrated that learning about a study from familiar and trusted sources in the Black community, including family members, friends, community leaders, and physicians, can influence perceived norms and likelihood of research participation (Diaz et al., 2008; Drake et al., 2017; Hoyo et al., 2003). Campaign messages were endorsed and shared by members of the Black community, including AA community leaders, physicians, and study staff members. Specifically, WURD Radio, the primary platform for campaign advertisements, is Black-founded and operated and has a high local following (WURD Radio, n.d.). AA media outlets like WURD play a strong role in reaching Black audiences (Cohen et al., 2008, 2011; Pickle et al., 2002) and serving as trusted sources of health information (Brodie et al., 1999; Padgett & Biro, 2003).

The present study

In the current follow-up qualitative study, open-ended interviews were conducted with 50 Black adults who had enrolled in the genetic study through the 2018 community recruitment campaign. Respondents were asked about their decisions to participate. Subsequent thematic analysis of interview transcripts was guided by the integrated behavioral model (IBM). Stemming largely from the reasoned actioned approach (RAA), the IBM identifies three major constructs that predict intention to perform a health behavior, which in turn predicts the behavior itself (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Montaño & Kaspryzk, 2015). These constructs include behavioral attitudes, normative perceptions, and personal agency. Behavioral attitudes depend on beliefs about anticipated outcomes of performing the behavior (instrumental attitudes) or feelings about the behavior (experiential attitudes). Normative perceptions are guided by the approval of others whose opinions are valued (injunctive norms), as well as the perception of how many other individuals may be engaging in the behavior (descriptive norms). Finally, personal agency is determined by one’s confidence in their own ability to perform the behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Building on RAA, the IBM includes additional predictors of behavior that can fall outside of individual control. These include environmental constraints, salience of the behavior, habit, and relevant knowledge/skills, as well as background factors such as demographics and other individual differences (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015).

Previous studies have used the IBM and RAA to organize analyses of qualitative interviews pertaining to several health behaviors, including breast-tissue donation (e.g. Ridley-Merriweather & Head, 2017; Shafer et al., 2018), organ donation (e.g. Bae & Kang, 2008), prostate health screenings (e.g. Ross et al., 2007), and clinical trial participation (e.g. Amico et al., 2017; Katz et al., 2019). These studies have provided insight into the roles of specific barriers, beliefs, and normative influences affecting health and research decisions within ethnic minority groups (Ridley-Merriweather & Head, 2017; Shafer et al., 2018). These qualitative interview studies are also valuable because they privilege the authentic voices of the ethnic minority participants (Brown & Grothaus, 2019). The current study applies a similar theory-guided analytic approach.

The IBM provides a useful framework for assessing factors influencing participation in the POAAGG genetic study, which may depend on structural factors impacting access as well as individual perceptions. As described above, the POAAGG community recruitment campaign sought to address environmental-level and individual-level constructs described by the IBM, by increasing access to care (eliminating environmental constraints) and communicating the benefits of participating in the program (behavioral outcomes) through community channels (normative influences). The present study examined the specific attitudes and norms expressed by genetic study participants within this context, where participation had already been made possible. The authors sought to address the following questions: (RQ1) How were campaign-emphasized outcomes, normative influences, and other factors linked to respondent reflections regarding their motivations to participate in the POAAGG Study? (RQ2) What, if any, reservations regarding research participation did respondents express? (RQ3) What motivations for participating were mentioned by respondents who expressed reservations?

Methods

Participants and recruitment

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Pennsylvania and followed all IRB parameters. The study population included 62 Black adults who had enrolled in the POAAGG genetic study through the 2018 campaign recruitment program and had consented to being re-contacted for an interview at the time of enrollment (Charlson et al., 2015). Each campaign message (e.g. WURD commercials, WURD physician interviews, print advertisements, etc.) offered a unique phone number, which allowed recruiters to track the original source of campaign information for each participant who called. All but two interviewees enrolled in the POAAGG Study by calling campaign-disseminated phone numbers to schedule appointments or by attending campaign-advertised community screening events. Two participants enrolled in the POAAGG Study during previously booked ophthalmology appointments after hearing about the campaign from physicians.

All 62 campaign participants were re-contacted for a phone interview within an average of six months of participation (lag time between participation and interview ranged from two to eleven months). Some participants were interviewed upon initial contact, whereas others made appointments to be interviewed at a later time. Eleven program participants could not be reached, and one declined to participate in the interview. In total, 50 interviews were conducted (response rate 80.6%). These recorded phone interviews and subsequent analyses were conducted with informed verbal consent from participants.

Data collection

One of this study’s co-first authors, an AA from Philadelphia, was the community outreach expert for the genetic study recruitment campaign. Through her role in the campaign, she became familiar with the study participants, and conducted all 50 interviews. Each interview was approximately 10 minutes long and included nine open-ended questions about reasons and reservations for participating in the genetic study (see Table 1 for full list of questions). At the end of the interview, respondents were asked two closed-ended questions about their household income and education levels. All other demographic data were recorded prior to interviews at the time of study enrollment. Before the first official interview was conducted, the interview guide was piloted with five participants in the genetic study who had agreed to be re-contacted but had not participated through the 2018 recruitment campaign. These interviews were excluded from analyses.

Table 1.

Open-ended interview questions

| Q1 | Can you tell me how you feel about having participated in this study? |

| Q2 | What were your reasons for participating in this study? |

| Q3 | Did you have any reservations about participating in this study? If so, what? |

| Q4 |

If Q3=yes: How did you

overcome those reservations? If Q3=no: What made you feel comfortable about calling to participate? |

| Q5 | How did your experience participating in this study affect your feelings about research? |

| Q6 | How did you feel about participating in genetic research prior to this experience? |

| Q7 | What is your answer when you are asked what your race or ethnicity is? |

| Q8 | What significance, if any, did your racial/ethnic identity play in your decision to participate in this study? |

| Q9 | If we asked you how to motivate other people

who are Black/African American to participate in research studies, what

would you answer? |

An external transcriptionist was hired to type recordings. The transcripts of all 50 participants who agreed to be interviewed were included in this analysis. All participant names were redacted and each respondent was assigned an ID number.

Coding Process

The codebook was developed by an MD/MPH student and a PhD student, the latter who coordinated the initial POAAGG Study recruitment campaign. To start, these two investigators read 35 transcripts (13 overlapping) and generated a list of respondent answers (codes) corresponding with each interview question. For example, in response to “What were your reasons for participating?”, one code was “access to care”. Both investigators coded a random sample of six transcripts and adjusted code definitions to increase intercoder reliability (Krippendorff, 2019). A final codebook provided criteria and asked coders to classify each transcript as true or false for each code [e.g. “Did the respondent cite receiving medical care for him/herself as a reason for participating in the program?” (yes=true; no=false)].

Coding was conducted using Qualtrics (Version Aug. 2019). The final coders included the interviewer and the two investigators who developed the codebook. The interviewer helped ensure respondent perspectives were appropriately interpreted and represented throughout the coding process (Caldwell et al., 2015; Krippendorff, 2019). Intercoder reliability for all three coders was .82 overall and above .73 for all codes. Discrepancies were resolved by privileging the interviewer’s code. After completing coding, the sums and proportions of transcripts marked as true for each code were calculated using Stata (Version 15.0).

Results

Respondent characteristics

All participants were self-identified Black individuals (including AA, African Caribbean, and African descent). The majority of respondents either had been diagnosed with (56%) or were at risk of developing (18%) glaucoma. Table 2 summarizes the demographic information for all respondents. Income and education level were not collected for those who declined to interview. There were negligible differences in disease status, age, and sex between interviewed and non-interviewed participants.

Table 2.

Respondent demographic characteristics

| Demographic Category | |

|---|---|

| Annual Income (%) | |

| <$25,000 (or retired) | 42.0 |

| $25-$49,999 | 30.0 |

| $50-$74,999 | 14.0 |

| ≥75,000 | 6.00 |

| NA | 10.0 |

| Education (%) | |

| Some high school | 6.60 |

| High school diploma | 11.1 |

| Some college | 26.7 |

| Junior college/Trade school | 11.1 |

| College degree | 13.3 |

| Graduate degree | 24.4 |

| N/A | 6.60 |

| Female (%) | 44.0 |

| Age M (sd) | 68.7 (11.3) |

| Total | N=50 |

Coding results

Eight codes and five sub-codes emerged during the hand coding process. Codes were classified into four categories: anticipated outcomes, personal factors, normative influences, and reservations. Table 3 describes the definitions and proportion of transcripts meeting the criteria for each code. Details and examples of responses are provided below.

Table 3.

Coding Results: Factors Influencing POAAGG Genetic Study Participation

| Category | Code | Sub-Code | Dimension Mentioned in Interview | Sum* (freq.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticipated outcomes | Benefit to self | Personal benefits of study participation, including improving or maintaining personal health, learning about glaucoma, free and/or convenient access to glaucoma specialists, and compensation | 46 (92%) | |

| Unhappy with current provider | Dissatisfaction with current eyecare provider; mentions of seeking new provider | 6 (12%) | ||

| Accessibility | Program efforts that facilitated study participation, including assistance with transportation, expedited appointment booking, wheelchair and walker accessibility, no charge for appointment, and/or hosting local screening outreach event | 11 (22%) | ||

| Compensation | Compensation for study participation or lunch provided during appointment or outreach event | 8 (16%) | ||

| Desire to improve glaucoma care and treatment options for others through study participation | 25 (50%) | |||

| Personal factors | Family history | Family members diagnosed with glaucoma or at risk of glaucoma | 12 (24%) | |

| Normative influences | Prior conversation | Family member or friend encouraging participation; Learning of study from other participants | 8 (16%) | |

| WURD | Learning about study from WURD | 32 (64%) | ||

| Reservations | Any reservation | Concern about participating in genetic research due to history of exploitation of Black people in research | 17 (34%) | |

| Reservations of others (only) | General concern of others in the Black community, but not explicitly for self | 8 (16%) | ||

| Personal reservations | Concerns for self | 9 (18%) |

Total number of interview transcripts (n=50; 1/ respondent) coded “true” for relevant code. Categories are not mutually exclusive.

Research question 1: Influences on research participation

Anticipated outcomes: Individual benefits.

Consistent with campaign messaging, the majority of respondents (92%) were motivated by the opportunity to improve or maintain personal health. One respondent saw participating as an opportunity to learn more about her diagnosis: “I do have glaucoma. I know that to be a fact. And I just wanted to check it out, see if there were some advantages there for me.” Relatedly, 12% of respondents viewed participation as an opportunity to get a second opinion or switch ophthalmologists, and 22% mentioned study efforts to remove logistic constraints (e.g. providing screening events locally, wheelchair accessibility, organizing and covering the cost of transportation, providing lunch vouchers) facilitated participation and access to care. Sixteen percent of respondents mentioned the $10 study compensation or food provided as contributing factors for participation.

Anticipated outcomes: Benefits to others.

The second primary motivating factor for participation was the desire to help others, which was cited by half of the interviewees. These respondents most often spoke about contributing to a future cure. As one respondent stated, “It might not help me, but it could help someone else save their eyesight.” In many cases, respondents discussed wanting to help others in their family and community, as described below.

Personal factors influencing participation: Family history.

Twenty-four percent of respondents reported having a family history of glaucoma. Some respondents knew their family history put them at higher risk of disease, and therefore wanted to learn more. One respondent said, “My mother was a glaucoma suspect, and I’ve been diagnosed as a glaucoma suspect, and so I was always told that I needed to be checked out from time to time.” Others expressed feeling personally invested in finding a cure due to a family history of vision loss:

For generations in my family, we’ve had a lot of eye problems; you know, the uncle, the father, the sisters… And in fact, we had a couple of people that lost their eyesight. And they never had an answer for it.

In addition to wanting to contribute to finding a cure, some respondents viewed program participation as an opportunity to directly help family members affected by glaucoma. One respondent brought his brother, another glaucoma patient, with him to the free screening appointment. He said, “I wanted to benefit both myself and my brother and [participating in the study] had family benefits so people in the future would have a benchmark or a guideline.” These examples illustrate how family history could motivate screening attendance for personal prevention and participation in a study to help future generations.

Personal factors influencing participation: Racial identity.

In addition to helping family members, several respondents explicitly mentioned wanting to help other AA individuals at risk for glaucoma. Respondents were asked, “What significance, if any, did your racial or ethnic identity play in your decision to participate in the study?” In direct response to this question, over half of respondents (52%) explicitly reported that their racial identity, and the study’s focus on Black people, influenced their decision to enroll. Another 12% mentioned their racial identity elsewhere in the interview (unprompted). For some respondents, racial identity heightened perceived personal benefits; learning about glaucoma’s prevalence and severity in the AA community further motivated the pursuit of screenings and information. As one respondent stated: “I’m a Black male and it affects Black males or AAs in general, so it was a wise decision to, to get it done.” However, most discussions of race pertained to the importance of the study in helping the Black community. One respondent stated, “I thought that searching for why we have a number of AAs who get glaucoma and, more important, leading to ways to help prevent and cure it, would be a good thing.” Another respondent described a sense of responsibility as a community member for participating in research:

For some reason women of color don’t tend to participate in medical studies. So, any time it comes to us being treated, we’re like guestimates, you know. They don’t have a history of how this drug will affect us because we weren’t part of the study…So, we have to participate in some of these things.

As this reflection exemplifies, participation was viewed by several respondents as an opportunity to contribute to better care options for others in the Black community.

Normative influences.

Several respondents reported hearing about the study from a source in the AA community, suggesting that normative influences were important in motivating participation. Sixteen percent of interviewees discussed the study with others before participating and six percent mentioned attending appointments or outreach events with friends or family members. Sixty-four percent initially found out about the study through WURD Radio.

When asked about the characteristics of WURD messaging that influenced participation, 20% of respondents mentioned that WURD was a familiar and credible source of information. For example, one respondent said, “I have WURD Radio on right now. It’s something that I’ve been listening to for years.” One respondent described the value of hearing a Black physician interviewed on a WURD program before seeing the physician for a screening appointment: “I was glad I had an African American female ophthalmologist…where I’ve gone, there were no African American doctors”.

Others mentioned feeling more comfortable participating after speaking to Black study staff members on the phone and during appointments. One respondent recalled:

The young lady that approached me in the beginning when I made the call to say that I would volunteer, I think she also was African American, and I was very impressed with the way she presented the information to me. And even the day that I participated, I saw a couple young Black people and I felt very good about that.

As these quotes capture, interactions with other AA community members were meaningful at every point in the participation process, including first hearing about the study on WURD Radio, discussing participation with family and friends, calling the hotline to schedule an appointment, and during the appointment itself.

Research question 2: Reservations about medical research

To address the second research question, the authors sought to understand how current and past mistreatment of Black patients in research influenced respondents’ decisions to participate in the genetic study. Overall, 34% of respondents described reservations about medical research either for themselves or others in the Black community. While 16% of respondents expressed these concerns more generally (non-personal reservations), 18% said these concerns impacted them personally (personal reservations). One 81-year-old respondent said:

Most likely people in my generation would be apprehensive about participating in studies if it’s touted as something to do with Blacks…Because of things that have happened to our people in the past, the studies that were conducted on Black people.

The same respondent specifically described personal reservations, “When I hear about something just pertaining to Black people, I do get a bit cautious, yes.” However, when asked why she participated, she replied, “To help other people, that was my prime motivation for agreeing to be in the study.” The reflections of this respondent capture how, despite her acknowledgement of the risk of experiencing mistreatment as an AA research participant, she was motivated by the potential for her study participation to benefit others.

Research question 3: Motivations when reservations were expressed

The third research question asked how anticipated outcomes for participating in research differed among respondents who discussed reservations compared to those who did not. Mentioning any reservations (personal or non-personal) was significantly associated with expressing the motivation to benefit others. Specifically, of the 17 respondents who described reservations, 13 (77%) mentioned benefits to others as an important outcome of research participation, whereas only 36% of those who did not state any reservations mentioned this specific motivation.

Differences were smaller for mentions of benefits to self, personal factors, and normative influences between those who expressed reservations and those who did not. Respondents who expressed reservations were slightly more likely to mention family history (38% compared to 18%), racial identity (83% compared to 55%), prior conversations with others about the POAAGG Study (24% compared to 12%), attending appointments with others (9% compared to 0%), and hearing about the POAAGG Study on WURD Radio (71% compared to 58%) as important factors influencing their participation. On the other hand, respondents who expressed reservations were slightly less likely to mention personal benefits (82% compared to 97%), specifically access to care (12% compared to 27%) and compensation (12% compared to 18%), and equally likely to mention seeing the appointment as an opportunity to get a second opinion or switch providers (12% for both groups). These comparisons suggest that, while personal benefits were consistently important, the role of community (e.g. helping family and other community members as well as learning from community members about the POAAGG Study) was particularly meaningful when respondents held reservations about medical research.

Discussion

Recruitment of AAs for medical studies has proven difficult in the past due to barriers to access and reservations about participating, which are rooted in a troublesome history of exploitation of Black research participants. Understanding how medical studies, starting with recruitment, can most effectively address reservations about research is crucial for building inclusive research programs. The IBM identifies behavioral attitudes and normative influences as important determinants of health behavior, and previous work has explored how these constructs may affect research participation across different contexts and populations (Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). The POAAGG Study community recruitment campaign spread awareness about the need for preventative eye screenings and continuous care in a community at elevated risk for glaucoma, provided access to specialists, and recruited participants for a study to elucidate the heterogeneous genetic architecture of POAG and eventually develop precision treatment options in the future (Kikut et al., 2020). The present follow-up study used content analysis of open-ended interviews to learn how campaign-emphasized outcomes and normative sources influenced participation.

Aligning with campaign message themes, the most common anticipated outcome for enrolling in the study was individual benefits, particularly access to glaucoma specialists and health information. Improving care options for others, including family and Black community members, was the second most common anticipated outcome. In addition to sharing these positive instrumental beliefs, over 75% of respondents heard about the genetic study from WURD Radio, discussed the study with others prior to participating, or participated alongside friends or family, suggesting the strong and pervasive role of normative influences in this context. One-third of respondents described reservations about discrimination and/or exploitation associated with participating in research as AAs, either for themselves or for others. Respondents who expressed reservations were more likely to mention helping others as a reason for deciding to participate.

While the IBM outlines general constructs likely to predict health behavior, interview and survey studies can help to identify the relative influence of each of these constructs within specific contexts and populations (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Montaño & Kasprzyk, 2015). Additionally, the IBM’s flexibility allows for the identification of medical research recruitment needs related to both developing effective messaging and addressing racial inequalities in access to care. As an example, the present interview analysis examined respondent motivations for participating in a glaucoma genetic study recruitment system designed to simultaneously improve access to glaucoma care. Findings suggest that reservations about medical research (i.e. negative experiential attitudes) in the Black community may be overcome when appropriate communication and institutional efforts are made. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that providing access to care and health information can encourage research participation (Brewer et al., 2014); that helping others is an important motivation (McDonald et al., 2012; Scherr et al., 2019; Walker et al., 2014); and that hearing information from normative sources in the Black community can influence participation decisions (Diaz et al., 2008; Drake et al., 2017; Hoyo et al., 2003). The current study strengthens a growing body of literature demonstrating that community-centered recruitment efforts can help address reservations about research (Jones et al, 2017; McDonald et al., 2012, 2014; Ochs-Balcom et al., 2015; Skinner et al., 2015). Building on prior research, a significant number of respondents in the present study recognized discrimination and exploitation of Black participants as contributing to low representation of AA individuals in research programs. This recognition was associated with the desire to increase representation and to help improve care for the Black community through genetic study participation.

Implications

Racial inequalities and discrimination continue to contribute to distrust of medical research in the Black community, having especially severe consequences in the present moment. According to a Pew Research survey conducted in May 2020, 44% of Black Americans reported that they would not get a COVID-19 vaccine if it became available, compared to 25% of White Americans and 26% of Hispanic Americans (Thigpin & Funk, 2020). Communication efforts, combined with initiatives to improve access to care, are vital when it comes to building trust and mitigating the disproportionate burden of disease in the Black community (HHS, 2017). In light of the present study, three important implications and areas for future work are highlighted below.

First, valid concerns about research injustices and maltreatment persist in the AA community, even among those who elect to participate in research (Bates & Harris, 2004; Gamble, 1993; Hussain-Gambles et al., 2004). However, in addition to improving and maintaining personal health, the desire to help others may balance out negative experiential attitudes, or reservations, about participating in medical research. Previous studies have documented the important role of altruistic motivations for Black research participants (Ridley-Merriweather & Head, 2017). Respondents with reservations about research specifically emphasized their desire to help their families and community, suggesting that recruitment campaigns should emphasize not only benefits to individual participants, but how research participation can lead to benefits for others in the Black community. However, similar to the POAAGG Study, these messages will likely be most effective coming from trusted Black sources in the community.

Second, and related, researchers must recognize the importance of belonging and community in Black culture and in the context of everyday communication, when approaching AA people to participate in research. This recruitment campaign spread information through opinion leaders with credibility in the community, including WURD Radio hosts and AA medical professionals. One of the co-first authors is a Black outreach expert, who helped implement the recruitment campaign and interviewed all respondents in the present study. Potentially as a result of this community-integration, the respondents for the present study participated in the program and agreed to interviews at an exceptionally high response rate (80.6%). Additionally, a number of respondents discussed the study with others prior to participating and attended appointments with others. The authors have recently called for more attention to the role of everyday interpersonal communication in influencing not only when individuals decide to engage with the healthcare system (e.g., go to a doctor’s appointment, enroll in a medical study), but also how it influences the communication that takes place in those encounters (Head & Bute, 2018). In sum, an important finding of this study is a recognition that connections to other Black people are an important element of the Black participants’ motivations for and comfort with being part of a medical study, both during recruitment and participation.

Finally, future research recruitment efforts should partner with Black leaders to emphasize the importance of inclusive research in mitigating racial disparities in medicine and combine recruitment efforts with increased access to clinical services. This may mean a paradigm shift in how traditional medical studies have been conducted with a “typical white research participant” to better address the unique experiences and needs of AAs, and other underserved groups, by involving non-white cultural norms into the research experience (Dutta, 2018). Black media outlets can be instrumental in facilitating these partnerships and reaching AA audiences (Brodie et al., 1999; Padgett & Biro, 2003). Communication channels that integrate medical research and the Black community, through partnerships, outreach, interviews, and recruitment of Black research staff and physicians, are vital for adequately addressing health and research disparities.

Limitations

While this study has several strengths, particularly conveying the perspectives of Black study participants using open-ended questions and systematic quantitative coding methods, there are a few limitations. Of note, the study sample included individuals who agreed to participate in research. This data cannot support judgements about why others did not participate, or which perceptions separated participants from non-participants. Rather than comparing perceptions and reservations among participants and those who chose not to participate, the present objective was to offer insights and suggestions from individuals who had the unique experience of participating in the POAAGG Study’s community-based program.

Additionally, respondent perspectives may have changed as a result of participating, and in the time between participation and interviews for the current study. These interviews were conducted between two and eleven months after respondents participated in the initial POAAGG Study. Therefore, it is possible that certain feelings about research reported at the time of the interview were not present or did not influence participants’ initial decisions to participate. Although the interview specifically asked respondents why they participated in the study, self-reports in response to open-ended questions may not capture all reasons.

Despite these limitations, an open-ended interview approach allowed respondents to offer reflections organically, providing rich qualitative data. The study identified patterns across transcripts to identify perceptions most commonly affecting research participation among respondents and further elaborated on findings with direct quotes from participants. These respondent-generated beliefs can inform future community health campaigns in survey-development, message design, and evaluation (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010).

Conclusion

It is imperative that health researchers prioritize inclusive research design, community partnerships, and tailored messaging to mitigate racial health disparities. Awareness of historical mistreatment of AA patients in medical research is not an absolute barrier to participation. Distrust in health research may be overcome when studies focus on the mutual goals of addressing concerns for individuals’ health and for the health of others. Campaign messages may need to be tailored based on individuals’ past experiences with and current views of medical research. Emphasizing the importance of research to benefit others, as well as offering access to medical care during research enrollment and participation, may help address concerns about exploitation among potential research participants. Recruitment teams should include members of the community, remove barriers to access, and create pathways of communication that emphasize improving health in the community. The findings from this study can inform not only future medical research studies aiming to recruit Black participants, but they can also serve as a framework to inform recruitment, build trust in medical research, and improve care for other underserved populations.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland (grant #1RO1EY023557-01) and Vision Research Core Grant (P30 EY001583). Funds also come from the F.M. Kirby Foundation, Research to Prevent Blindness, The UPenn Hospital Board of Women Visitors, and The Paul and Evanina Bell Mackall Foundation Trust. The Ophthalmology Department at the Perelman School of Medicine and the VA Hospital in Philadelphia, PA also provided support. The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

References

- Amico KR, Wallace M, Bekker L-G, Roux S, Atujuna M, Sebastian E, Dye BJ, Elharrar V, & Grant RM (2017). Experiences with HPTN 067/ADAPT study-provided open-label prep among women in Cape Town: Facilitators and barriers within a mutuality framework. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1361–1375. 10.1007/s10461-016-1458-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H-S, & Kang S (2008). The influence of viewing an entertainment-education program on cornea donation intention: A test of the theory of planned behavior. Health Communication, 23(1), 87–95. 10.1080/10410230701808038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates BR, & Harris TM (2004). The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis and public perceptions of biomedical research: A focus group study. Journal of the National Medical Association, 96(8), 1051–1064. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2568492/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt AM (1978). Racism and research: The case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. The Hastings Center Report, 8(6), 21–29. 10.2307/3561468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer LC, Hayes SN, Parker MW, Balls-Berry JE, Halyard MY, Pinn VW, & Breitkopf CR (2014). African American women’s perceptions and attitudes regarding participation in medical research: The Mayo Clinic/The Links, incorporated partnership. Journal of Women’s Health, 23(8), 681–687. 10.1089/jwh.2014.4751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M, Kjellson N, Hoff T, & Parker M (1999). Perceptions of Latinos, African Americans, and Whites on media as a health information source. The Howard Journal of Communications, 10(3), 147–167. 10.1080/106461799246799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EM, & Grothaus T (2019). Experiences of cross-racial trust in mentoring relationships between Black doctoral counseling students and White counselor educators and supervisors. The Professional Counselor, 9(3), 211–225. 10.15241/emb.9.3.211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cain GE, Kalu N, Kwagyan J, Marshall VJ, Ewing AT, Bland WP, Hesselbrock V, Taylor RE, & Scott DM (2015). Beliefs and preferences for medical research among African-Americans. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 3(1), 74–82. 10.1007/s40615-015-0117-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell WB, Reyes AG, Rowe Z, Weinert J, & Israel BA (2015). Community partner perspectives on benefits, challenges, facilitating factors, and lessons learned from community-based participatory research partnerships in Detroit. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 9(2), 299–311. 10.1353/cpr.2015.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell MC, & Tishkoff SA (2008). African genetic diversity: Implications for human demographic history, modern human origins, and complex disease mapping. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 9(1), 403–433. 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ES, Sankar PS, Miller-Ellis E, Regina M, Fertig R, Salinas J, Pistilli M, Salowe RJ, Rhodes AL, Merritt WT, Chua M, Trachtman BT, Gudiseva HV, Collins DW, Chavali VRM, Nichols C, Henderer J, Ying G, Varma R, … O’Brien JM (2015). The Primary Open-Angle African American Glaucoma Genetics Study. Ophthalmology, 122(4), 711–720. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen EL, Caburnay CA, Luke DA, Rodgers S, Cameron GT, & Kreuter MW (2008). Cancer coverage in general-audience and Black newspapers. Health Communication, 23(5), 427–435. 10.1080/10410230802342176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen EL, Caburnay CA, & Rodgers S (2011). Alcohol and tobacco advertising in Black and general audience newspapers: Targeting with message cues? Journal of Health Communication, 16(6), 566–582. 10.1080/10810730.2011.551990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn EG, Husamudeen M, Larson EL, & Williams JK (2014). Increasing participation in genomic research and biobanking through community-based capacity building. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 24(3), 491–502. 10.1007/s10897-014-9768-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz VA, Mainous AG, McCall AA, & Geesey ME (2008). Factors affecting research participation in African American college students. Family Medicine, 40(1), 46–51. https://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol40Issue1/Diaz46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake BF, Boyd D, Carter K, Gehlert S, & Thompson VS (2017). Barriers and strategies to participation in tissue research among African-American men. Journal of Cancer Education, 32(1), 51–58. 10.1007/s13187-015-0905-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta MJ (2018). Culture-centered approach in addressing health disparities: Communication infrastructures for subaltern voices. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(4), 239–259. 10.1080/19312458.2018.1453057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Moysich K, Kiviniemi MT, Saad-Harfouche FG, Davis W, Clark-Hargrave N, Ciupak GL, Ambrosone CB, & Walker C (2013). Community-based partnership to identify keys to biospecimen research participation. Journal of Cancer Education, 28(1), 43–51. 10.1007/s13187-012-0421-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press. 10.4324/9780203838020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble VN (1993). A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 9(6), 35–38. 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30664-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg AJ, Hull SC, Wilfond BS, & Sharp RR (2011). Patient perspectives on group benefits and harms in genetic research. Public Health Genomics, 14(3), 135–142. 10.1159/000317497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haga SB (2010). Impact of limited population diversity of genome-wide association studies. Genetics in Medicine, 12(2), 81–84. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ca2bbf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Berry-Bobovski L, Francis C, Ramsey L, Chapman RA, & Albrecht TL (2013). Unexpected findings in the exploration of African American underrepresentation in biospecimen collection and biobanks. Journal of Cancer Education, 29(3), 580–587. 10.1007/s13187-013-0586-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head KJ, & Bute JJ (2018). The influence of everyday interpersonal communication on the medical encounter: An extension of Street’s ecological model. Health Communication, 33(6), 786–792. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1306474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann TJ, Tang H, Thornton TA, Caan B, Haan M, Millen AE, Thomas F, & Risch N (2014). Genome-wide association and admixture analysis of glaucoma in the Women’s Health Initiative. Human Molecular Genetics, 23(24), 6634–6643. 10.1093/hmg/ddu364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyo C, Reid MLV, Godley PA, Parrish T, Smith L, & Gammon M (2003). Barriers and strategies for sustained participation of African-American men in cohort studies. Ethnicity & Disease, 13(4), 470–476. https://europepmc.org/article/med/14632266 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, & Leese B (2004). Why ethnic minority groups are under-represented in clinical trials: A review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 12(5), 382–388. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00507.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BL, Vyhlidal CA, Bradley-Ewing A, Sherman A, & Goggin K (2017). If we would only ask: How Henrietta Lacks continues to teach us about perceptions of research and genetic research among African Americans today. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4(4), 735–745. 10.1007/s40615-016-0277-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz AWK, Mensch BS, Woeber K, Musara P, Etima J, & van der Straten A (2019). Understanding women’s motivations to participate in MTN-003/VOICE, a phase 2b HIV prevention trial with low adherence. BMC Women’s Health, 19(1), 18–18. 10.1186/s12905-019-0713-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikut A, Vaughn M, Salowe R, Sanyal M, Merriam S, Lee R, Becker E, Lomax-Reese S, Lewis M, Ryan R, Ross A, Cui QN, Addis V, Sankar PS, Miller-Ellis E, Cannuscio C, & O’Brien J (2020). Evaluation of a multimedia marketing campaign to engage African American patients in glaucoma screening. Preventive Medicine Reports, 17, 101057. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS-J, Cho MK, Kraft SA, Varsava N, Gillespie K, Ormond KE, Wilfond BS, & Magnus D (2018). “I don’t want to be Henrietta Lacks”: Diverse patient perspectives on donating biospecimens for precision medicine research. Genetics in Medicine, 21(1), 107–113. 10.1038/s41436-018-0032-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Quinn GP, Montel-Ishino FA, Arevalo M, Bynum SA, Noel-Thomas S, Wells KJ, Gwede CK, Meade CD, & Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network Partners. (2012). Formative research on perceptions of biobanking: What community members think. Journal of Cancer Education, 27(1), 91–99. 10.1007/s13187-011-0275-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JA, Barg FK, Weathers B, Guerra CE, Troxel AB, Domchek S, Bowen D, Shea JA, & Halbert CH (2012). Understanding participation by African Americans in cancer genetics research. Journal of the National Medical Association, 104(7–8), 324–330. 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30172-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JA, Vadaparampil S, Bowen D, Magwood G, Obeid JS, Jefferson M, Drake R, Gebregziabher M, & Hughes Halbert C (2014). Intentions to donate to a biobank in a national sample of African Americans. Public Health Genomics, 17(3), 173–182. 10.1159/000360472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaño DE, & Kasprzyk D (2015). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In Glanz K, Rimer BK, & Viswanath K (Eds.), Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (5th ed., pp. 95–124). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs-Balcom HM, Jandorf L, Wang Y, Johnson D, Meadows Ray V, Willis MJ, & Erwin DO (2015). “It takes a village”: Multilevel approaches to recruit African Americans and their families for genetic research. Journal of Community Genetics, 6(1), 39–45. 10.1007/s12687-014-0199-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett J, & Biro FM (2003). Different shapes in different cultures: Body dissatisfaction, overweight, and obesity in African-American and Caucasian females. Journal of Pediatric & Adolescent Gynecology, 16(6), 349–354. 10.1016/j.jpag.2003.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh R, O’Keefe L, Salowe R, Mccoskey M, Pan W, Sankar P, Miller-Ellis E, Addis V, Lehman A, Maguire M, & O’Brien J (2019). Factors associated with participation by African Americans in a study of the genetics of glaucoma. Ethnicity & Health, 24(6), 694–704. 10.1080/13557858.2017.1346189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickle K, Quinn SC, & Brown JD (2002). HIV/AIDS coverage in Black newspapers, 1991–1996: Implications for health communication and health education. Journal of Health Communication, 7(5), 427–444. 10.1080/10810730290001792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleet A, Sulewski M, Salowe RJ, Fertig R, Salinas J, Rhodes A, Merritt III W, Natesh V, Huang J, Gudiseva HV, Collins DW, Chavali VRM, Tapino P, Lehman A, Regina-Gigiliotti M, Miller-Ellis E, Sankar P, Ying G-S, & O’Brien JM (2016). Risk factors associated with progression to blindness from primary open-angle glaucoma in an African-American population. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 23(4), 248–256. 10.1080/09286586.2016.1193207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popejoy AB, & Fullerton SM (2016). Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature, 538(7624), 161–164. 10.1038/538161a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley-Merriweather KE, & Head KJ (2017). African American women’s perspectives on donating healthy breast tissue for research: Implications for recruitment. Health Communication, 32(12), 1571–1580. 10.1080/10410236.2016.1250191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Kohler CL, Grimley DM, Green BL, & Anderson-Lewis C (2007). Toward a model of prostate cancer information seeking: Identifying salient behavioral and normative beliefs among African American men. Health Education & Behavior, 34(3), 422–440. 10.1177/1090198106290751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr CL, Ramesh S, Marshall-Fricker C, & Perera MA (2019). A review of African Americans’ beliefs and attitudes about genomic studies: Opportunities for message design. Frontiers in Genetics, 10, 548–548. 10.3389/fgene.2019.00548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer A, Kaufhold K, & Luo Y (2018). Applying the health belief model and an integrated behavioral model to promote breast tissue donation among Asian Americans. Health Communication, 33(7), 833–841. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1315678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirugo G, Williams SM, & Tishkoff SA (2019). The missing diversity in human genetic studies. Cell, 177(4), 1080–1080. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HG, Calancie L, Vu MB, Garcia B, DeMarco M, Patterson C, Ammerman A, & Schisler JC (2015). Using community-based participatory research principles to develop more understandable recruitment and informed consent documents in genomic research. PloS One, 10(5), e0125466–e0125466. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skloot R (2011). The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. Broadway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Thigpin CL & Funk C (2020, May 21). Most Americans expect a COVID-19 vaccine within a year; 72% say they would get vaccinated. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/21/most-americans-expect-a-covid-19-vaccine-within-a-year-72-say-they-would-get-vaccinated/?utm_source=pew+research+center&utm_campaign=d756d107ab-weekly_2020_05_23&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_3e953b9b70-d756d107ab-399504101 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017, July). 2016 National healthcare quality and disparities report. (Publication No. 17–001). https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr16/2016qdr.pdf

- Walker ER, Nelson CR, Antoine-LaVigne D, Thigpen DT, Puggal MA, Sarpong DF, Smith AM, Stewart AL, & Henderson FC (2014). Research participants’ opinions on genetic research and reasons for participation: A Jackson Heart Study focus group analysis. Ethnicity and Disease, 24(3), 290–297. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25065069/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WURD Radio. (n.d.). About WURD. https://wurdradio.com/about-us/