Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemias (AML) and acute lymphoid leukemias (ALL) are heterogenous diseases encompassing a wide array of genetic mutations with both loss and gain of function phenotypes. Ultimately, these both result in the clonal overgrowth of blast cells in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and other tissues. As a consequence of this, normal hematopoietic stem cell function is severly hampered. Technlogies allowing for the early detection of genetic alterations and understanding of these varied molecular pathologies have helped to advance our treatment regimens towards personalized targeted therapies. In spite of this, both AML and ALL continue to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, in part because molecular therapies for the plethora of genetic abnormalities have not been developed. This underscores the current need for better model systems for therapy development. This article reviews the current zebrafish models of AML and ALL and discusses how novel gene editing tools can be implemented to generate better models of acute leukemias.

1. INTRODUCTION

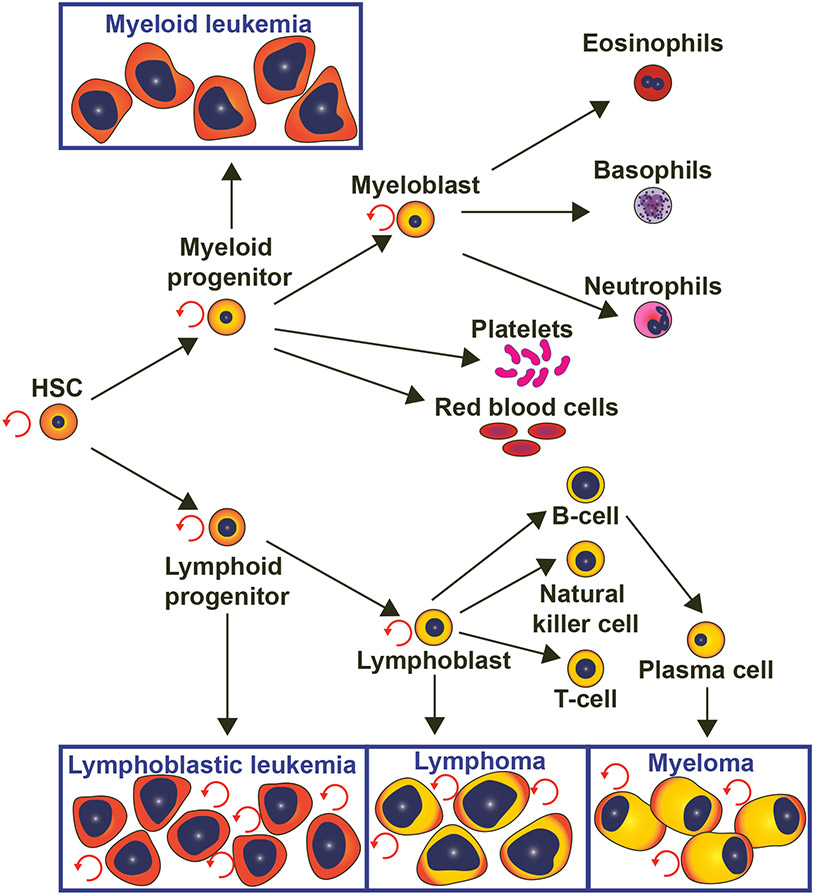

Hematopoiesis is the lifelong formation of blood cells that arise from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), a clonal population of multipotent stem cells that have the capacity to self-renew and differentiate into all mature blood cell types. Progenitor cells that develop from HSCs divide and differentiate into increasingly specialized blood cells. For example, myeloid progenitors differentiate into red blood cells, platelets and granulocytes, while lymphoid progenitors give rise to cells of the adaptive immune system as well as natural killer cells (Figure 1). Although the anatomical sites of hematopoiesis vary amongst organisms, the molecular regulation of HSC development, self-renewal and hematopoietic differentiation are highly conserved, and are reviewed elsewhere (Gomes et al., 2020; Wittamer & Bertrand, 2020; Chapman & Zhang, 2020; Brown, 2020; Wattrus & Zon, 2018).

Figure 1. Hematopoiesis is the life-long formation and turn-over of blood cells:

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) is a multipotent clonal population that has the ability to self-renew and differentiate into myeloid and lymphoid progenitors, which give rise to all functional cells of the blood. Different types of blood cancer originate from different types of blood cells. “Myeloid or myelogenous” leukemia originates from myeloid progenitors and “lymphoid or lymphoblastic” leukemia arises from lymphoid progenitors. Comparably, lymphoma and myeloma originate from lymphocytes and plasma cells, respectively.

When the molecular cues governing hematopoietic homeostasis are misregulated, cancers of the blood arise; every three minutes someone in the United States is diagnosed with a hematopoietic malignancy (Street, 2020). This review focuses on leukemias, which the American Cancer Society predicts will kill approximately 23,000 Americans this year (Siegel et al., 2020). Leukemias are classified in two ways: First, based on the type of blood-forming cells affected, where myeloid (or myelogenous) leukemias result from diseased myeloid cells, and lymphoid (or lymphoblastic) leukemias arise from abnormal lymphocytes (Vardiman et al., 2009; Arber et al., 2016). These are further designated as either acute or chronic. This review discusses acute myeloid leukemias (AML) and acute lymphoid leukemias (ALL), which arise from progenitor cell populations and are relatively fast growing. AML accounts for approximately 50% of leukemia-related deaths, while 6% of these deaths are attributed to ALL (Siegel et al., 2020).

It is hypothesized that both AML and ALL arise from genetic alterations that occur in one of the multipotent blood progenitor subtypes (Brown et al., 2020). Ultimately, this leads to the abnormal proliferation of the progenitor “blast” cells, which interferes with the normal maintenance and production of differentiated blood cells (Figure 1). These genetic abnormalities may be passed on by the parents, or may result from multiple genetic mutations acquired throughout the patient’s lifetime. Early studies on twins suggested that both AML and ALL require two genetic mutations for progression (Brown et al., 2020).

Due to the genetic variances in different subtypes, both AML and ALL can be acquired in childhood or adulthood; the nature of the mutation and the time of onset both affect the prognosis of this heterogenous group of cancers. The diverse nature of these different cancers emphasize the necessity for developing more targeted and personalized therapeutic interventions (Brown et al., 2020; L. Long et al., 2020; F.-L. Huang et al., 2020; Kirtonia et al., 2020). To achieve this, we will ultimately need to develop better model organisms that recapitulate the specific mutations and phenotypes of these diseases, allowing for the development of targeted therapies.

Here, we review some of the classical approaches that have been undertaken to generate animal models of AML and ALL. We discuss the utility of these models in our understanding of the pathogenesis of acute leukemias and for the development of therapeutics. In particular, we highlight the potential for future use of the zebrafish, Danio rerio, as an alternative model organism to study these types of leukemias. Zebrafish have been used as a model organism for nearly five decades (Walker & Streisinger, 1983), and their high fecundity rates, translucent development, amenability to high throughput screens, and ease of genetic manipulation offer many advantages over other animal models. Furthermore, zebrafish and humans use conserved mechanisms in blood development and homeostasis (Howe et al., 2013; de Jong & Zon, 2005; Baeten & Jong, 2018). Finally, with the advances of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing (Xiao et al., 2013; Jao et al., 2013; Cong et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2013; Hruscha et al., 2013; B. Chen et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013; Ablain et al., 2015; Grainger et al., 2017), we can now engineer precise genetic modifications that recapitulate those seen in human disease.

2. ZEBRAFISH AS MODEL ORGANISMS FOR STUDYING THE BLOOD

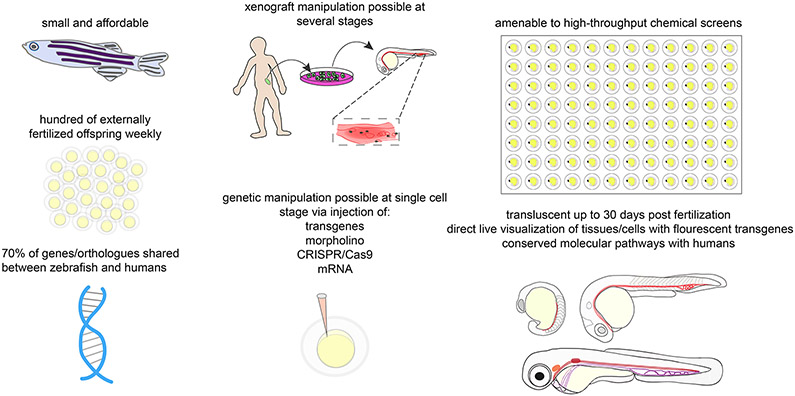

Zebrafish have been popularized as a model organism for studies of developmental biology and cancer (Figure 2). Approximately 70% of human genes can be found in zebrafish, and over 80% of human proteins that can cause disease have an orthologue found in zebrafish (Howe et al., 2013; Vilella et al., 2009). Zebrafish have several salient features that make them attractive as a model system, such as their relatively inexpensive maintenance, external development and ease of genetic manipulation. In addition, females have a high fecundity rate and are capable of laying hundreds of eggs per week, allowing for high experimental throughput. Due to the relatively small size and external development of zebrafish embryos and larvae, growth is possible in small dishes, enabling multiple growth conditions amenable to drug screens. Furthermore, during early stages of their development, zebrafish are translucent, allowing for direct observation of distinct cells and tissues in real-time (such as with fluorescent transgenes) (Chakrabarti et al., 1983; Spitsbergen, 2007; Stoletov et al., 2007). In addition, with the advent of the Casper fish, a pigment-less line of zebrafish, there is also opportunity to image live zebrafish through adulthood (White et al., 2008). Therefore, zebrafish are highly amenable to studying dynamic processes such as hematopoietic development and homeostasis.

Figure 2. Benefits of Zebrafish Models in Cancer Research:

This figure depicts the benefits of zebrafish in research in general as well as specifically in leukemia research. Zebrafish are affordable and easy to maintain in laboratories. Every week, sexually mature zebrafish lay and fertilize eggs that are easily accessible for genetic manipulation at the single cell stage, drug screens, and in vivo fluorescent cell visualization throughout development. Zebrafish are good models for xenograft manipulation at several stages as well. Many human and zebrafish genes are genetically similar and the hematopoeitc pathway is conserved.

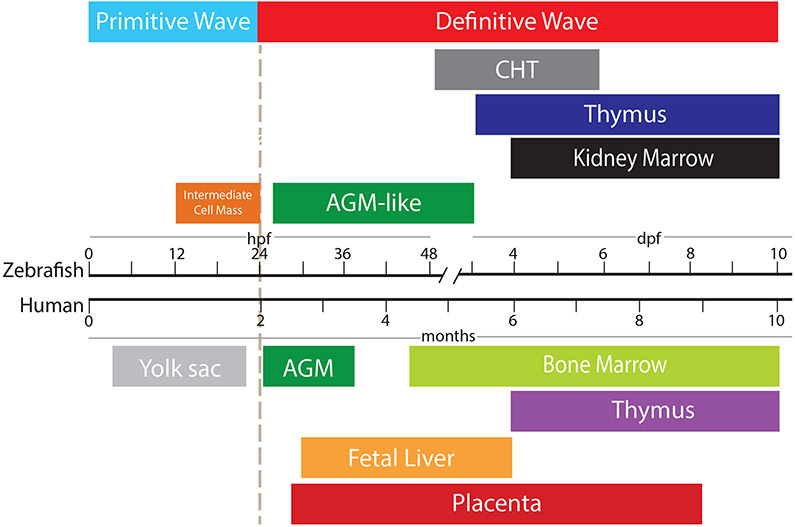

The anatomical locations of blood development vary among species (Figure 3); however, the hematopoietic regulation at the molecular level is highly conserved between zebrafish and humans (de Jong & Zon, 2005). The development of the hematopoietic system requires a concerted program of transcriptional regulators and signalling molecules (Freire & Butler, 2020). During the progression of blood cancers, many of these same regulators are either mutated or dysregulated, leading to aberrant regulation of the HSC and multipotent progenitor pools. Being able to recapitulate these specific genetic changes in zebrafish may be one avenue to therapy development.

Figure 3. Timeline of anatomical locations of hematopoiesis in zebrafish and humans.

Primitive blood cells emerge in the intermediate cells mass in zebrafish, the equivalent to the human yolk sac. Subsequently, definitive blood cells (HSCs) first emerge in the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) in humans and in the aorta (AGM-like) in zebrafish. HSCs now enter circulationand proliferate in the caudal hematopoietic tissue (CHT) in fish and fetal liver in humans. Hereafter, HSCs colonize the kidney marrow (fish) or bone marrow (humans), which is where hematopoiesis will occur during the organism’s lifetime. hpf= hours post-fertilization; dpf= days post-fertilization.

Genetic manipulation has always been an attractive feature of zebrafish, which are easily microinjected at the zygote stage (Stuart et al., 1988). Genetic loss of function can be analysed using antisense morpholinos (Nasevicius & Ekker, 2000); gain of function can be studied through mRNA injection (Ekker et al., 1995). In addition, transgenic lines are easily generated using plasmid injection, allowing for modifications in cell biological processes through the use of dominant-negative constructs, or activating overexpression, or for the visualization of specific cells or tissues with fluorescent reporters (Higashijima et al., 1997; Q. Long et al., 1997). In addition, forward and reverse genetic screening has allowed for the discovery of many novel modifiers of a huge variety of biological processes, including hematopoiesis (North et al., 2009; Ransom et al., 1996; Sood et al., 2006; Weinberg et al., 1996). Mutagenesis can be achieved in a variety of ways, including through the use of: chemicals, irradiation, viral vectors, and more targeted approaches such as Cas9/CRISPR, targeting induced local lesions in genomes (TILLING), zinc finger nucleases (ZFN), or transcription activator effector nuclease (TALEN)-mediated gene editing (Amsterdam et al., 2011; L. Chen et al., 2013; Draper et al., 2004; P. Huang et al., 2011; Hwang et al., 2013; Sander et al., 2011; Solnica-Krezel et al., 1994; Sood et al., 2013; Varshney et al., 2013). Studying developmental biology and cancer in zebrafish has direct implications on human biology as well. For example, the plethora of transgenic zebrafish lines available for the blood and vascular systems make this model particularly amenable to the study of the blood (Bolli et al., 2011; Butko et al., 2015; Corti et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2009; Roman et al., 2002; Shiau et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2010). Furthermore, although HSC development occurs in different anatomical compartments, the molecular mechanisms are conserved, and many techniques to study the hematopoietic system are transferrable (Bertrand et al., 2007; Davidson & Zon, 2006; Stachura & Traver, 2011; Traver et al., 2003, 2007). For example, our group has previously shown that a Wnt9a/Fzd9b signal required during HSC development in zebrafish is also essential for deriving hematopoietic progenitors from human embryonic stem cells (Grainger et al., 2016, 2019; Richter et al., 2018). Due to their translucent nature, zebrafish can also be used to track labeled cancer cells in live imaging assays, enabling the study of metastatic processes, as well as key tumor cell microenvironment growth properties such as angiogenesis (Smith et al., 2010; Vlecken & Bagowski, 2009).

Owing to their genetic conservation with humans, low maintenance costs, ability to be housed densely, and permeability to small molecules, it has previously been shown that transgenic zebrafish are able to serve as useful tools for drug screening for cancer therapeutics (den Hertog, 2005; Jung et al., 2012; Kari et al., 2007; Letrado et al., 2018; Parng et al., 2002; Zon & Peterson, 2005). Small molecules can be directly added to the embryo growth medium (Peterson et al., 2000) and fluorescent transgenes make high throughput analysis of chemical effects possible. More than ten drugs have been approved for various clinical trials after being identified through chemical screens in zebrafish (Cully, 2019). Of note from the list is a prostaglandin E2 derivative, later dubbed ProHema, originally discovered for its requirement in regulating HSC numbers in zebrafish (North et al., 2007). This study gave rise to clinical trials to assess the improvent in umbilical cord HSC engraftment during transplant, which would allow for fewer donor cells to be used during this procedure. Patients administered ProHema showed an increase in early neutrophil engraftment and a reduction of viral infection-related adverse events, showing promise for this strategy. However, clinical trials were eventually discontinued with the development of a more targeted therapy (Fate Therapeutics, 2013, 2017, 2018b, 2018a). Nevertheless, ProHema provides us with an example of how zebrafish molecular discovery can be translated to human disease. Ultimately, a suitable model for drug discovery in zebrafish will require faithful representation of the biology driving diseases like AML and ALL in humans, as well as being able to recapitulate the manifestations of the cancers.

3. HUMAN AML AND ALL

AML and ALL are hematological malignancies that result in the abnormal proliferation of myeloid or lymphoid precursors, respectively. These cancerous blood progenitor cells, termed “blast cells,” quickly proliferate in the bone marrow and subsequently spread to the peripheral blood and other tissues. This rapid expansion of blast cells results in an overpopulated bone marrow with limited capacity to produce mature blood cells (Figure 1). These hematopoietic deficiencies manifest as anemia, leukopenia, or extramedullary (EM) disease (Fernandez et al., 2019; Papaemmanuil et al., 2016). In humans, as well as in animal models, these are characterized experimentally by a direct examination of the proportion of blood cells in circulation, as well as in the mature HSC niche (i.e. the bone marrow in mammals, or the kidney marrow in teleosts). Patients also experience fever, excessive tiredness, as well as excessive loss of appetite and weight, effects which can be measured in animal models as well.

In addition to the mutations discussed below, leukemias can arise from myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), a group of disorders that result in abnormal hematopoiesis and are characterized by cytopenia of the peripheral blood and morphologic dysplasia (Haferlach, 2019). MDS results from the failure to support the homeostatic signals required to maintain HSCs in the bone marrow and it is most often diagnosed by a morphological evaluation of the bone marrow and blood cells (Hasserjian, 2019). According to the American Cancer Society, 30% of MDS patients will progress to AML. Although MDS was previously classified as a pre-cancerous disorder, it is now considered a form of cancer.

For most cancer types, deciphering the stage of the disease is critical for establishing an appropriate treatment regimen for the patient. The usual method of using tumor growth to determine the stage, however, is not feasible for leukemias since they do not always manifest as solid tumors. Therefore, determining the subtype of acute leukemia is extremely important in establishing a treatment regimen. Both AML and ALL can be caused by a plethora of genetic abnormalities, making these extremely heterogenous diseases. This heterogeneity is reflected by numerous subtypes of these cancers. Two main systems of classification for AML and ALL subtypes have been established. In the 1970s, the French-American-British classification system was established, classifying subtypes based on the type of cell the cancer develops from and how mature the cells are. In 1997, the World Health Organization (WHO) established a new classification system for ALL that accounted for morphology and cytogenics of the blast cells (Harris et al., 1999) and was later revised in 2016 (Arber et al., 2016) (Table 1). Similarily, the AML system was replaced in 2008 with the current classification system developed by the WHO (Vardiman, 2010), which was most recently revised in 2016 (Arber et al., 2016). This classification system takes into account genetic alterations, morphological features, and clinical history of patients, providing a more specific mechanism for determining treatment regimens (Table 2). However, even with these classifications, treatment regimens are still largely non-specific and mainly depend on either chemotherapy alone or chemoptherapy with HSC transplants. More specifically targeted therapies could be established with a better understanding of the genetic bases for these leukemic subtypes.

Table 1:

World Health Organization (WHO) system of ALL classification.

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) |

| B-cell ALL |

| B-cell ALL with certain genetic abnormalities (gene or chromosome changes) |

| B-cell ALL with hypodiploidy (the leukemia cells have fewer than 44 chromosomes [normal cells have 46]) |

| B-cell ALL with hyperdiploidy (the leukemia cells have more than 50 chromosomes) |

| B-cell ALL with a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 [t(9;22)] (the Philadelphia chromosome, which creates the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene) |

| B-cell ALL with a translocation between chromosome 11 and another chromosome |

| B-cell ALL with a translocation between chromosomes 12 and 21 [t(12;21)] |

| B-cell ALL with a translocation between chromosomes 1 and 19 [t(1;19] |

| B-cell ALL with a translocation between chromosomes 5 and 14 [t(5;14)] |

| B-cell ALL with amplification (too many copies) of a portion of chromosome 21 (iAMP21)* |

| B-cell ALL with translocations involving certain tyrosine kinases or cytokine receptors (also known as “BCR-ABL1–like ALL”)* |

| B-cell ALL, not otherwise specified |

| T-cell ALL |

| Early T-cell precursor lymphoblastic leukemia* |

Provisional Entity

Table 2:

World Health Organization (WHO) system of AML classification.

| Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and related neoplasms |

| AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities |

| AML with t(8;21)(q22;q22.1);RUNX1-RUNX1T1 |

| AML with inv(16)(p13.1q22) or t(16;16)(p13.1;q22);CBFB-MYH11 |

| APL with PML-RARA |

| AML with t(9;11)(p21.3;q23.3);MLLT3-KMT2A |

| AML with t(6;9)(p23;q34.1);DEK-NUP214 |

| AML with inv(3)(q21.3q26.2) or t(3;3)(q21.3;q26.2); GATA2, MECOM |

| AML (megakaryoblastic) with t(1;22)(p13.3;q13.3);RBM15-MKL1 |

| Provisional entity: AML with BCR-ABL1 |

| AML with mutated NPM1 |

| AML with biallelic mutations of CEBPA |

| Provisional entity: AML with mutated RUNX1 |

| AML with myelodysplasia-related changes |

| Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms |

| AML, NOS |

| AML with minimal differentiation |

| AML without maturation |

| AML with maturation |

| Acute myelomonocytic leukemia |

| Acute monoblastic/monocytic leukemia |

| Pure erythroid leukemia |

| Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia |

| Acute basophilic leukemia |

| Acute panmyelosis with myelofibrosis |

| Myeloid sarcoma |

| Myeloid proliferations related to Down syndrome |

| Transient abnormal myelopoiesis (TAM) |

| Myeloid leukemia associated with Down syndrome |

AML with genetic abnormalities is the largest and most diverse of these subtypes. Similarly, B-cell ALL with genetic abnormalities is the largest group of ALL. These genetic alterations are often caused by chromosomal translocations that result in fusion proteins of genes associated with hematopoietic development, cellular metabolism and/or homeostasis (Yunis, 1983; Peschle et al., 1984; Wiernik et al., 2013; Yang-Feng et al., 1985). These fusion proteins act as oncogenes with dual functionalities attributed to the two proteins involved. This in turn enhances the unchecked proliferation of precursor cells. In addition to chromosomal translocation generating aberrant fusion proteins, loss of function and activating mutations of a plethora of regulatory factors have been identified.

Over 300 genetic alterations have been associated with AML and new mutations continue to emerge every year for both AML and ALL. These impact on protein function in a variety of contexts. For example, Nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) mutations are the most common in AML, occuring in 30% of AMLs (Falini et al., 2005; Verhaak et al., 2005). These can be both chromosomal translocations, as well as point mutations leading to a truncated protein with aberrant localization and function; this disrupts its normal function in numerous cellular processes including protein aggregation, ribosomal transport and centrosome duplication (Szebeni & Olson, 1999; Tarapore et al., 2002; Cuomo et al., 2008; Sipos & Olson, 1991; Lindström, 2010; Grisendi et al., 2005). Like many mutations, the context of NPM1 mutations is important for prognosis. To illustrate, most translocations involving NPM1 confer overall favourable prognosis (Döhner et al., 2005), while a poor prognosis is seen when combined with mutations in the FLT3 gene (Thiede et al., 2006; Scholl et al., 2008). Transcriptional output can also be affected. For example, mutations in the epigenetic modifier DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) gene have been associated with 25% of AML leukemia cases (Ley et al., 2010; Marková et al., 2012a; Pezzi et al., 2012; Castelli et al., 2018) and are also less commonly associated with T-cell ALL (Choi et al., 2015; Bond et al., 2019). These mutations are thought to lead to hypermethylation and shut down of tumor suppressor genes (Ley et al., 2010). Mutations in cell signalling molecules have effects on the balance of differentiation and proliferation. For instance, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) is normally a regulator of survival, proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic cells (Grafone et al., 2012); mutations occur in approximately 30% of AML cases and have very poor prognoses (Yokota et al., 1997; Kelly et al., 2002; Kiyoi et al., 1999; Abu-Duhier et al., 2000; Daver et al., 2019a).

A characteristic gene associated with both AML and ALL is the Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) gene, a histone lysine N-methyltransferase that is involved in a plethora of chromosomal translocations that result in novel fusion partners (FPs) and cause aggressive forms of leukemia with poor prognosis overall (Slany, 2009). Over 100 MLL translocations have been identified with a significant number of these associated with both AML and ALL (Meyer et al., 2018). These MLL-FP proteins are known to be common driver mutations (Milne, 2017). ALL associated with MLL-AF4 confers around 66% of all MLL-related cases (Prange et al., 2017) and confers very poor prognosis (Pui et al., 2011).

A hallmark genetic abnormality associated with ALL is the BCR-ABL1 rearrangement which results in B-cell ALL (Ribeiro et al., 1987; Gleissner et al., 2002). “BCR-ABL1-like ALL” is a subtype associated with translocations involving certain tyrosine kinases and cytokine receptors that have a function in B-cell development and in general confer poor prognosis (Table 1). Some of the genes involved in “BCR-ABL1-like ALL” include ABL1, JAK2, EPOR, and FLT3 (Roberts et al., 2012)

Finally, despite the fact that AML and ALL associated with genetic alterations are the largest groups of subtypes for each type of acute leukemias, it is important to point out that not all cases are associated with a genetic alteration. When AML cannot be classified by a genetic mutation, it may be classified by morphological features, or by expression profiles using RNA sequencing (SH et al., 2008; Vardiman, 2010; Handschuh, 2019).

Despite major advancements, the therapeutic regimen for leukemia has remained largely unchanged over the last few decades, with the exception of a few more targeted therapies, includingimmunotherapies. Standard treatment for AML and ALL consists of an initial period of intense chemotherapy to deplete the patient’s leukemic cells, commonly achieved with cytarabine (Betcher & Burnham, 1990; Löwenberg et al., 2011). Once patients are in remission, an additional period of chemotherapy is administered, often concurrently with an HSC transplant (Rowe, 2009; Ustun et al., 2019). Two major obstacles to this regimen are development of resistance to chemotherapy post-remission and HSC transplant limitations such as graft-versus-host disease (Estey, 2018; Thol & Ganser, 2020; Khaddour et al., 2020). One way to circumvent these issues is with the use of molecular targeted therapies, which have proven to be highly efficient by blocking specific aberrant molecular events (Y. T. Lee et al., 2018). One example is Midostaurin, a multitarget kinase inhibitor that is efficient in treating FLT3-associated AML (Stone et al., 2017). However, there remain numerous other AMLs and ALLs without targeted therapies. This is a major challenge due to high patient to patient heterogeneity in genetic alterations associated with the leukemia. Additionally, the field has recently focused on the development of immunotherapies, which recruits immune cells from the patient, or uses chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) based targeting to fight off the cancerous cells using cell surface molecules as targets. Current immunotherapies for leukemias include Blinatumomab (Topp et al., 2011) and Interferon α2a (Tura et al., 1994), among others. Being able to develop animal models with the specific genetic alterations in human AML would permit the screening of potential pharmacological modulators. Since zebrafish use molecular processes that are identical to humans during hematopoietic development (Paik & Zon, 2010; Jin et al., 2007) and are highly amenable to large-scale drug and genetic screens, these may play a key role in developing future targeted molecular therapies.

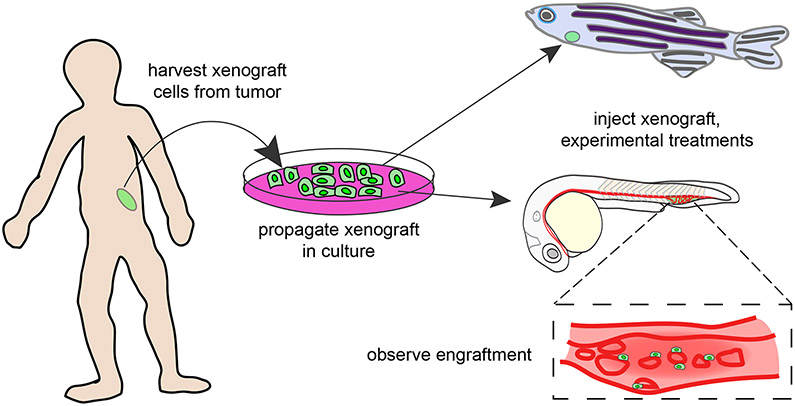

4. CANCER XENOGRAFTS IN ZEBRAFISH

Xenografts, which are cells from one species grown in another, are useful in research as a way to study human cell properties and overcome ethical obstacles associated with human in vivo studies (Figure 4). Most commonly, xenografts are transplanted into immunocompromised mice; however, xenografts in mammals are difficult to monitor live, a drawback that can be overcome using the optically transparent zebrafish model, which is moreover beneficial in that it does not require immune suppression for xenograft transplation without rejection, up to 14 days post fertilization (Lam et al., 2004). In addition, a cheaper and more high throughput strategy for identifying potential therapeutics for diseases prior to clinical studies is required because of the high rates of failure of small molecule treatments in humans (Bleicher et al., 2003), opening the door for human xenografts in zebrafish.

Figure 4. Xenograft Between Human and Zebrafish.

Human tumor cells are harvested and cultured in a dish in preparation for a xenograft in zebrafish. The xenograft can take place in the juvenile or adult stage of zebrafish and the fluorescent cells are easily visualized in vivo during the transluscent stage of zebrafish development.

The first reported cancer xenograft in zebrafish used human melanoma cells injected into zebrafish larvae. Although the cells survived the transplant, they remained dedifferentiated and did not progress to tumor formation (L. M. J. Lee et al., 2005). Subsequently, another group was more successful, in part due to a change in parameters and potentially also the cell type used for engraftment (Haldi et al., 2006). Specifically, some key parameters for successful xenotransplants are: incubation at 35°C—which allows for normal growth of both injected human cells and the zebrafish embryos—and 48 hours post fertilization as the ideal time for xenograft injections since at this time zebrafish can handle the temperature shift better, and cell migration is at a stage where it is an active process that can be better monitored (Corkery et al., 2011; Haldi et al., 2006; Pruvot et al., 2011).

Human cancer cell xenografts in zebrafish embryos have also been exploited to study the pharmacological activity of possible cancer treatments for breast cancers, ovarian carcinomas, gliomas, pancreatic cancers, and leukemias (de Boceck et al., 2016; Corkery et al., 2011; Geiger et al., 2008; Lally et al., 2007; Latifi et al., 2011; Vlecken & Bagowski, 2009). For example, leukemia xenografts have been used for chemical drug screens, where injected leukemic cells circulate and proliferate within days, and abrogation of this can be seen after drug administration (Pruvot et al., 2011). This type of system can be used to test a variety of compounds. For instance, known chemotherapeutics, such as Paclitaxel, also kill xenografted human tumor cells in a dose-dependent manner in zebrafish (Jung et al., 2012). Using these types of drug screen and xenograft strategies, human leukemic cells engrafted in zebrafish have been shown to be sensitive to imatinib, all trans-retinoic acid, cyclophosphamide, and mafosfimide in targeted therapy screens (Corkery et al., 2011; Pruvot et al., 2011). Moreover, zebrafish xenografts were used to identify a mutation sensitive to γ-secretase inhibition in a xenograft that was obtained from two children with T-cell ALL (Bentley et al., 2015). Although these studies resulted in successful inhibition of disease in zebrafish, the patients were in remission after the discovery and the results have not yet been translated in vivo. Most recently, an AML xenograft in zebrafish was used as validation in the discovery of a new regulatory mechanism in AML (Arriazu et al., 2020), further demonstrating the feasibility for zebrafish xenografts in cancer studies.

In addition to these embryonic studies, xenografts can also be performed in adult zebrafish. For instance, Casper fish (which lack skin pigment) were preconditioned with busulfan, an immune-suppressant that had not previously been utilized in zebrafish, and found to have higher rates of engraftment in both carcinomas and AML (Khan et al., 2019). Finally, a line with humanized cytokines has been developed, which may help to address the concern that zebrafish lack human microenvironmental cues (Rajan et al., 2019).

Overall, xenografts in zebrafish have been very useful for exploring cancer cell properties as well as drug efficacy; however, human xenografts into zebrafish also have limitations such as the native differences between the grafted cells and the new microenvironment. In addition, human cells and structures are larger than those of zebrafish (Davidson & Zon, 2004), and although transplants of different tumor types have been successful in zebrafish, size differences may affect the biochemical cues present in the model. Similarly, since human cells grow optimally at 37°C and zebrafish grow at 28°C (Detrich et al., 2010), it is difficult to determine if the relatively higher temperature at which the xenografts are commonly grown has confounding effects on the overall model and results. Finally, while injection of human cancer cells into zebrafish embryos does not require any type of immunosuppression (Haldi et al., 2006; Lam et al., 2004; L. M. J. Lee et al., 2005), xenografts performed in adult zebrafish do require immune suppression (Langenau et al., 2004; Patton et al., 2005; Traver et al., 2003), which limits the types of spatiotemporal analysis that may be done in this model as well as the natural immune response to cancer (Stoletov et al., 2007). Altogether, xenotransplants can be an effective way to visualize cancer cell interactions, growth patterns, and abilities.

5. TRANSGENIC ZEBRAFISH MODELS OF LEUKEMIA

The earliest zebrafish models of transgenesis were developed in the 1980s (Stuart et al., 1988, 1990). Transgenic zebrafish have been especially useful in biology research due to the translucent nature of the developing larvae, enabling live-imaging of cells and tissues specifically labeled with fluorescent transgenes. Furthermore, the zebrafish is capable of withstanding heat shock, which can be used to mediate transgene activation in a temporal manner. The facile nature of generating transgenic zebrafish led to the development of a variety of lines useful for modeling leukemia, some with more success than others (Table 3, Table 4).

Table 3: Current Transgenic Models of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Zebrafish.

Models of leukemia that have been generated are listed based on the gene that was modified. Each model lists the type of expression from the transgene, resulting disease state, findings, and model limitations. The group responsible for its initial generation along with important follow-up studies are referenced in the last column.

| Model by Gene Modification |

Type of Expression |

Disease State/Findings |

Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML/MPN | ||||

| 9zspi1:MOZ/TIF2-EGFP | Myeloid fusion of human MYST3/NCOA2 under spi-1 promoter with fluorescence | Fluorescence seen by 22 hpf in myeloid cells and muscle cells in trunk region. Kidney infiltration by invasion of myeloid blast cells, splayed eyes, tumor, and distended abdomen observed | Only 2/180 transgenic embryos demonstrated symptoms of AML which appeared 14-26 months post injection | (Zhuravleva et al., 2008) |

| spi1:IGI:NUP98-HOXA9 | Myeloid fusion of human NUP98-HOXA9 under spi-1 with heat shock inducible excision of IGI (Cre dependent EGFP) | Primitive macrophage differentiation is inhibited. Red blood cell fate and damaged cell arrest and apoptosis is suppressed. Upregulation of protooncogenes bcl2 and bcl2l1 observed along with myeloid cell infiltration | 23% of transgenic fish develop MPN 19-23 months later but not full AML | (Forrester et al., 2011; Deveau et al., 2015) |

| hsp:AML1-ETO | Global expression of human AML1-ETO fusion after heat shock under hsp70 promoter | Myeloid erythroid progenitors redirected to granulocytes by loss of gata1, scl, and increase in pu.1. No circulating blood but blast cell accumulation detected. scl overexpression & TSA rescue phenotype | Expression of transgene is transient and global not restricted to myeloid lineage | (Yeh et al., 2008, 2009; Cunningham et al., 2012) |

| β-actin:LGL-KRASG12D; hsp70:cre | Somatic expression of human KRAS under β-actin activated by heat shock-induced, cre dependent, loss of fluorescence (LoxP-GFP-LoxP; LGL) | Varying tumor types and paleness accompanied with difficulty breathing and swimming seen. Myeloid cell expansion and ineffective erythropoiesis observed. | Juvenile death common in heat-shocked animals. Tumors developed in controls and heat shocked transgenic fish. | (Le et al., 2007) |

| CMV:n-Myc-EGFP | Global expression of murine Myc; heat shock inducible | Blast cells infiltrate organs and erythroid differentiation is downregulated while myeloid is upregulated. scl, lmo2, and mpo upregulated while gata1 is downregulated. Anemia seen in fish | Founders die after 5-13 months since founders become infertile after a year. | (Shen et al., 2013) |

| spi 1-NPMc+ | Myeloid expression of human NPMc+ mutant under spi-1 promoter with fluroescence | Increase in apoptosis observed dependent on p53 mutants which maintain selective advantage | Transient expression of NPMC+ due to mRNA injection | (Bolli et al., 2010) |

| fli1:GAL4-FF-GFP-HRASG12V | Hemogenic endothelial expression of human HRASG12V | Notch downregulates erythroids. The effect can be rescued with Notch intracedullar domain activation. Myeloid progenitor cell proliferation increased. | Primitive hematopoiesis disrupted in embryos | (Alghisi et al., 2013) |

| LDD731:CBLH382T | Mutant zebrafish line with missense point mutation in c-cbl | MPN with increased erythrocytes and monocytes in CHT. Point mutation in c-cbl responsible for phentotype is similar to patients. Primitive hematopoiesis is unaffected. | Lethality seen 14-15dpf in embryos with myeloid expansion | (Peng et al., 2015) |

| irf8 Δ57/Δ57 | Global missense in irf8 by 57 base pair deletion in sequence | MPN-like disease state develops with enhanced myeloid progenitior proliferation and decreased erythroid and lymphoid cells. | Additional unknown mutations lead to reduced apoptosis of leukocytes and neutrophils after larval stage | (Zhao et al., 2018) |

| spi1-SOX4-EGFP | Myeloid expression of human SOX4 under spi-1 with fluorescence | AML, leukomogenesis, Age-dependent increased myeloid infiltration in kidneys by 9-12 months | Destructured kidneys by 9 months | (Lu et al., 2017) |

| spi1:CREB-EGFP | Myeloid expression of human CREB under spi-1 with fluorescence | Tumors developed and fish struggled to swim. Cancer cells invaded kidneys and myeloid differentiation was blocked through c/ebpδ, similar to patients. Increased expression of oncogene bcl2 observed in conjunction with increased gata1 | Disease state requires 9-14 months to develop | (Tregnago et al., 2016) |

| spi1:FLT3/ITD-EGFP | Myeloid expression of human FLT3/ITD under spi-1 with fluorescence | Excess myeloid and blast cell invasion of kidney. 2/6 transgenic fish developed myeloid hyperplasia at 6 months and leukemia at 9 months | Low incidence of disease with only 2/6 transgenic fish developing leukemia | (Lu et al., 2016; He at al., 2014) |

| runx1:FLT3/ITD-EGFP | Hematopoetic stem and progenitor cell expression of human FLT3/ITD with fluorescence | Myeloid and hematopoeitc progenitor cell populations expanded from whole kidney marrow where fst was increased and found to be a CREB target via in silico modeling | Other AML symptoms not yet characterized | (He et al., 2020) |

TSA: Trichostatin A, MPN: Myeloproliferative Neoplasm, CHT: Caudal Hematopoetic Tissue

Table 4: Current Transgenic Models of Acute Lymphoid Leukemia in Zebrafish.

Models of leukemia that have been generated are listed based off the gene that was modified. Each model lists the type of expression from the transgene, resulting disease state, findings, and model limitations. The group responsible for its initial generation along with important follow-up studies are referenced in the last column.

| Model by Gene Modification |

Type of Expression |

Disease State/Findings |

Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL | ||||

| CMV/spi1:tel-jak2a | Global/myeloid fusion under spi1 endogenous promoter with Flag tag | Increased primitive blood (gata1+) cells and white blood cells observed. Anemic embryos and oncogenic lineage specificity seen. | High embryonic mortality rate prevents stable line generation | (Onnebo et al., 2005, 2012) |

| rag2:EGFP-mMyc/rag2:loxP-dsRED2-loxP-EGFP-mMyc | Fluorescent murine c-myc, endogenous lymphoid expression | ~5% efficiency with development of tumors. Lymphoblasts infiltrate kidney marrow, gut, gills, fins, and brain | Line requires in vitro fertilization to breed | (Langenau et al., 2003, 2005; Feng et al., 2010; Blackburn et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2020) |

| rag2:MYC-ER | Lymphoid human MYC expression inducible by estrogen receptor (ER) activation via 4HT | Tumor formation after inducing expression of MYC and complete tumor regression after removal of 4HT. Mitochondrial apoptosis mediates MYC oncogenicity | Other T-ALL phenotypes not described aside from tumor formation. No fluorescent labels in this line but possible with additional crosses. Additionally, Borga and Garcia et al demonstrated these fish may develop both B and T cell ALL | (Gutierrez et al., 2011, 2014; Ridges et al., 2012; Reynolds et al., 2014; Borga et al., 2018; Garcia et al., 2018) |

| EGFP-TEL-AML1 | Global expression of human fusions proteins under endogenous β-actin or localized endogenous lymphoid expression under rag2 | The first B-cell ALL model in zebrafish. B-cell differentiation arrested, kidney brain, liver and muscle infiltrated by blast cells and ~6% of fish with ALL developed fatal lymphoid hyperplasia. TEL-AML identified as a likely pre-leukemic mutation | Low incidence of disease at 3% | (Sabaawy et al., 2006) |

| rag2:hMYC-GFP/rag2:hMYC:cd79GFP | Lymphoid human MYC expression with fluorescence under the control of lck | Mixed model of both T-cell and B-cell ALL with high similarity to human expression profiles. Pre-B-ALL exhibits lower GFP expression than T-ALL and thirteen distinct ALL types were identified from this model | By 6 months this model can result in progeny with either B-ALL (12%), T-ALL (40%), or both at the same time (7%). | (Borga, et al., 2018, 2019; Park et al., 2020) |

| rag2:ICN1-EGFP | Lymphoid expression of truncated human Notch1 with fluorescence | Characterized by tumors, splayed eyes, distended abdomens, and lymphoblast infiltration in most tissues as well as atypical her4 expression in the thymus. 40% of F1 progeny developed leukemia | Only 2% of fish expressed GFP in thymus | (J. Chen et al., 2007; Blackburn at al., 2012) |

| rag2:TLX1-EGFP | Lymphoid expression of human TLX with fluorescence | Malignant lymphoblasts found in blood. Chromosomal duplications with T-ALL oncogenes and CNVs appeared when line was crossed with phf6 heterozygous mutants | Only 2 fish developed T-cell ALL after 13-14 months indicating additional genetic events necessary for fully-penetrative onset of leukemia | (Loontiens et al., 2020) |

4HT: 4-Hydroxytamoxifen; lck: lymphocyte protein tyrosine kinase

One method of inducing tumorigenesis in zebrafish is to robustly overexpress an oncogene, as in the rag2:EGFP-mMyc, which exhibited similar ALL disease progression to that seen in humans; however, the line is difficult to maintain due to the toll of the disease on adult fish (Langenau et al., 2003), highlighting the need for inducible and/or tissue-specific models (discussed below), and perhaps models more robustly recapitulating human gene variants. However, this model served as an important proof-of concept and was an important catalyst toward the generation of additional, more improved models of cancer in zebrafish.

Tissue-specific overexpression has also been used to model blood cancers in zebrafish. In particular, the cAMP response element binding (CREB) proto-oncogene is overexpressed in human AML and ALL patients (Crans-Vargas et al., 2002; Pigazzi et al., 2007). By using the hematopoietic spi-1 promoter to drive the human CREB, c/ebpδ was identified as the key molecular target after observing canacerous invasion of kidneys and blocked myeloid differentiation resulted through c/ebpδ, which is similar to patients (Tregnago et al., 2016). Interestingly, some pediatric AML patients have also been found to have high levels of the C/EBPδ protein during disease state, suggesting conservation of this mechanism between species (Haferlach et al., 2010; Radtke et al., 2009; Tregnago et al., 2016).

Tissue-specific transgenic models are not always successful. Specifically, when expressing a MOZ/TIF fusion cassette with the same spi-1 promoter, only 2/180 developed AML-like features, and this took up to two years (Zhuravleva et al., 2008). These animals exhibited invasion of the kidney marrow (akin to mammalian bone marrow) by myeloid blast cells, and some morphological defects such as protruding tumors and inflated eyes (Zhuravleva et al., 2008). Although this provided some minimal proof of principle, the efficiency of this model was too low to be useful as a tool to develop therapeutic interventions.

To generate an inducible transgenic model, AML1 and ETO coding sequences were fused downstream of heat shock promoter, enabling induction around 21 hours post fertilization; this recapitulated many aspects of AML, such as blast cell accumulation and disrupted hematopoiesis through scl downregulation (Yeh et al., 2008). The traceabilty of this model also allowed for the observation of cell fate changes wherein granulocytic cells formed from myeloerythroid cells in which pu.1 was upregulated. With the success of this model, the Peterson group was also able to identify Trichostatin A as a modulator of AML, and demonstrate a role for the COX/β-catenin dependent pathway in hematopoietic regulation in zebrafish, mice, and human leukemic cell xenografts (Yeh et al., 2008, 2009; Zhang et al., 2013). As a result of these zebrafish-initiated studies, Trichostatin A is currently in phase 1 clinial trials for treating human hematological maliginacy modulation (Vanda Pharmaceuticals 2018).

Perhaps the most successful strategy to date has been to combine spatial and temporal expression of oncogenes. This was achieved using expression of the human MYC proto-oncogene fused to a tamoxifen-inducible estrogen receptor, under regulatory control of the rag2 (T cell) promoter, which induced T-ALL that could be reversed with withdrawl of tamoxifen (Gutierrez et al., 2011). Using this strategy, the authors identified that a second genetic hit to either pten or Akt2 rendered tumor growth independent of MYC (Gutierrez et al., 2011). In addition, by combining this model with transgenically labelled lymphocytes in vivo, another group identified a drug they named Lenaldekar as being capable of inducing long-term remission in affected zebrafish (Ridges et al., 2012). Lenaldekar also inhibited human T cell expansion, (Cusick et al., 2012), supporting the use of zebrafish models for drug screens of human diseases. This model has been widely used for studying T-ALL; however, recently two groups identified the presence of at least 4 subtypes of ALL, including B-ALL and bi-phenotypic T/B-ALL, in the same syngeneic population of zebrafish previously believed to harbor only T-ALL (Borga et al., 2018, 2019; Garcia et al., 2019). A deeper analysis of previous work in light of these observations may lead to important insights on the molecular mechanisms responsible for the development of different types of leukemia, and these may translate into human treatments. The discovery of the variability in the MYC model may also lead to fruitful research on B-ALL since previously, only one model of B-ALL existed and it was not widely efficient nor practical (Sabaawy et al., 2006). For example, just recently the Frazer group published data on the effectiveness of a known T-ALL steroid, dexamethasone, on fish with B-ALL using the MYC model. The group found the steroid was able to induce remission in 100% of animals, however, after stopping treatment the leukemia returned in 56% of animals (Park at al., 2020).

It is important to note that while these models allow for studies such as gene expression profiles and drug screenings, transgenic animal models present a set of inherent limitations due to the random fashion of genomic integration. As a result of the lack of specific control over insertion of transgenes, the inserted DNA is subjected to epigenetic expression control from the surrounding DNA sequences. For example, if the transgene were inserted adjacent to a genomic region encoding genes not expressed in blood progenitors, it may be difficult to elicit a tumorigenic effect in these cells. Various types of chromatin and epigenetic silencing are always at risk of repressing the intended effect of the transgene. This may be part of the reason that the MOZ/TIF2 zebrafish displayed such low penetrance of AML (Zhuravleva et al., 2008). In fact, commonly used transgenic models frequently have structural variation and insertional mutagenesis that may lead to confounding genetic events and experimental analyses (Goodwin et al., 2019). Uncontrolled overexpression of transgenes can also present a problem for transgenic animals, where the resultant zebrafish are not viable long-term, or have fertility deficiencies (Kimura et al., 2014; Onnebo et al., 2005; Yeh et al., 2008; Zhuravleva et al., 2008). The key to generating more useful zebrafish models may therefore be precisely editing the genome to mimic the mutations seen in human disease.

6. TOWARD THE FUTURE: ZEBRAFISH GENETIC KNOCK-IN MODELS OF LEUKEMIA

More successful recapitulation of human disease has been accomplished using precisely targeted knock-in mouse models that recapitulate the mutations seen in human disease (Table 5). For example, animals harboring one of the most common AML mutations, MLL-AF9, display phenotypic attributes of AML such as an enlarged spleen and a blast overpopulated bone marrow (Corral et al., 1996; Dobson et al., 1999). These were subsequently used to determine that additional hits are required for leukemic pathogenesis (Johnson et al., 2003), which is a general theme with leukemic mutations (W. Chen et al., 2006; B. H. Lee et al., 2007; Stubbs et al., 2008; Dovey et al., 2017; Chou et al., 2012). In addition, inducible chromosomal translocations have also been engineered using Cre-loxP technologies (Collins et al., 2000; Drynan et al., 2005; Langenau et al., 2005), allowing for a refined temporal analysis after genetic disruption. For example, tamoxifen-inducible Cre-recombinase models allow for temporal control of oncogenic activity; this has been demonstrated in a triple transgenic mouse model with tamoxifen-inducible FLT3ITD driven AML (Solovey et al., 2019). Similarily, this has been achieved in the T cell ALL zebrafish model expressing MYC-ER under regulatory control of the rag2 promoter discussed above, where formed tumors when treated with tamoxifen and regressed in size when the treatment was withdrawn (Gutierrez et al., 2011).

Table 5.

Genetic Alterations associated with AML in humans

| Mutation | Incidence | Prognosis | Specific Mutations Involved |

Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMT3A | 25% of AML cases(Marková et al., 2012) | Poor prognosis, especially in double mutated | Missense mutations | (Marková et al., 2012a; Ley et al., 2010) | |

| FLT3 | 30% of AML FLT3-ITD-25% |

Poor prognosis | FLT3-ITD-25% This is a driver mutation. |

(Daver et al., 2019a) | |

| CEBPAdm | 7.5-11% | Poor prognosis | -p30 | This is a new entity 40% of patients experience relapse after remission |

(Tien et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2020) |

| CSF3R | Low | 5 year survival of CEBPA patients a lot lower with CSF3R mutations (57.4 vs 17.5%) | CBFB-MYH11 [inv(16)/t(16;16)]) | Associated with CEBPAdm | (Su et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018; Tarlock et al., 2020) |

| MLL associated | 15-20% of pediatric AML cases | Intermediate to poor outcome |

Mll-Af9-30% of Mll related cases(intermediate to poor prognosis) Mll-Af4- 66% of Mll related cases (poor prognosis) |

Prognosis depends of various factors (fusion partner, age, etc.) | (Balgobind et al., 2011; Prange et al., 2017b) |

| TP53 | Only 5-10% | Poor | Large deletions and karyotypic abnormalities in chromosomes 5, 7, and 17 | Associated with therapy related AML Poor survival rate of 5-9 months |

(Welch, 2018; Hunter & Sallman, 2019; Kadia et al., 2016) |

| NPM1 | 1/3 of newly diagnosed cases | Favorable, in the absence of Flt3-ITD | t(3;5)- results in NPM-MLF1 | Mislocalization of this protein leads to malignancy | (Brunetti et al., 2019; Schnittger et al., 2005) |

| CALM-AF10 | 7% of T cell ALL | Intermediate to poor | t(10;11)(p13;q14) | Therapeutic strategies are inefficient for this | (Barbosa et al., 2019; Ben Abdelali et al., 2013; Lange et al., 2019) |

| GATA2 | Not high incidence but poor prognosis | Poor | Dominant heterozygous missense mutation These are sometimes familial and heritable |

High expression linked to patients with resistant AML | (Hahn et al., 2011; Luesink et al., 2012; McReynolds et al., 2019) |

The use of mice as models for blood cancers is advantageous for a variety of reason such as high genome similarity to humans, conservation of organ anatomy and physiology, and a track record in recapitulating human disease (Table 6). However, while murine models have provided much of what we know of the pathogeneisis of leukemias, they are expensive to maintain. Additionally, their in utero development and small litter sizes make them less than ideal to use in a high throughput drug screens.

Table 6.

Pros and cons of mouse and zebrafish as model organisms.

| Mouse models | |

|---|---|

| Pros | Cons |

| Mammals/Vertebrates | Expensive to maintain |

| Existing model | HSCs develop in utero |

| Well characterized | Small litter size |

| High genetic conservation to humans | Slow development |

| Organ anatomy more similar to humans | Difficult genetic manipulation |

| Not translucent | |

| Immunocompromised mice required for xenografts | |

| Zebrafish models | |

| Pros | Cons |

| Vertebrates | Not mammals |

| Cost effective | Develop at lower temperatures than mammals |

| External fertilization | Less genetic conservation |

| Rapid development | Organ anatomy less similar to humans |

| Large offspring size | Less studied as a cancer model |

| Ease of genetic manipulation | Gene duplication complicates analysis |

| 80% conserved gene orthologues for disease causing genes | Different anatomical locations of HSC development and maintenance |

| Immune suppression for xenografts not required | Lack of specific antibodies |

| Simple tracing of xenografts | |

| Translucent | |

The high heterogenicity of leukemias underscores the need for an organism that can be used to generate numerous models of the numerous genetic alterations associated with AML and ALL in a rapid and efficient manner. Zebrafish develop faster than mice, are more cost-effective to maintain, have large numbers of offpsirng that develop ex vivo, and are their genetics are easily manipulated. The advantages for zebrafish modelling blood development and homeostasis and success of other types of zebrafish models are encouraging in pushing toward better models of leukemia. Until recently, it was not possible to introduce targeted genetic mutations in zebrafish; with the advent of CRISPR/Cas9 technology, as well as technologies like ZFN and TALENs, this is now a possibility (Doyon et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2013; Jao et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2013; Hruscha et al., 2013; Ablain et al., 2015; Grainger et al., 2017).

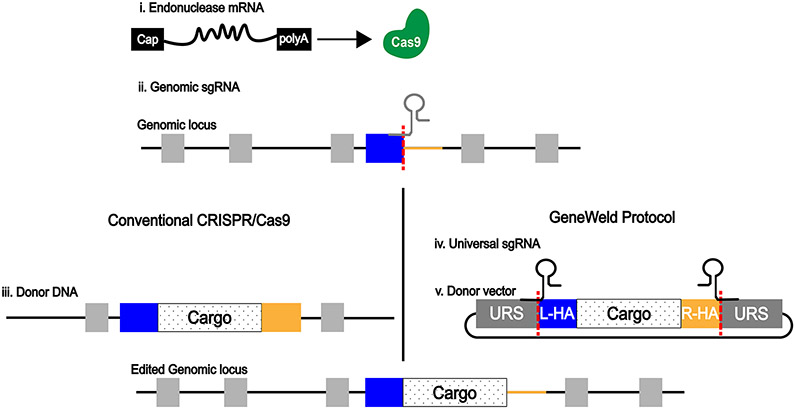

Cas9 endonucleases introduce double-stranded breaks (DSBs) directed to a specific site by a guide-RNA (Figure 4), which can subsequently be repaired by either non-homologous end joining or homology directed repair (HDR). We can exploit the HDR to introduce genomic alterations by providing a cell with a repair template containing the mutation. Conventional CRISPR/Cas9 uses a linear DNA molecule with significantly large homology arms (Figure 4). The large size of the homology arms greatly reduce the efficiency of the induced mutation. This method has proven to be successful for introducing pieces of DNA stably into the zebrafish genome (Hwang et al., 2013; Chang et al., 2013; Armstrong et al., 2016; Y. Zhang et al., 2016).

Wierson et al. have described a novel method that uses CRISPR/Cas9 to generate knock-in models of several organisms including zebrafish. Several components are injected to fertilized zebrafish embryos including an mRNA for the expression of the Cas9 endonuclease (Figure 5i). The Cas9 endonuclease when guided by a genomic single-guide RNA (sgRNA) will introduce a DSB at a specific site in the genomic DNA (Figure 5ii). These components are injected along with a donor vector (Figure 5iii) containing the “cargo” to be inserted at the targeted genomic site which is surrounded by short homology arms that correspond to the target genomic site. By surrounding the cargo by short homology arms the cell will repair the DSB in the genome and introduce the cargo DNA from the donor vector at the specific genomic site. The homology arms of the donor vector are liberated by the clavage of Cas9 at the Universal gRNA Site (URS). This system has been demonstrated to be highly efficient as well as highly specific, which are two important attributes of systems to generate knock-in models (Wierson et al., 2020). The zebrafish model organism along with these novel gene editing tools represent an efficient manner to generate accurate models of acute leukemias that are needed in order to generate targeted molecular therapies for the plethora of genetic abnormalities associated with these hematological malignancies.

Figure 5. CRISPR-Cas9 components to inject in zebrafish embryos for the generation of zebrafish knock-in models.

i. mRNA for expression of Cas9 endonuclease. ii. Genomic single-guide RNA for cleavage of target site of genomic locus. iii. Donor linear DNA with large homology arms for conventional CRISPR/Cas9 protocol. iv. Universal single-guide RNA for cleavage of donor vector and release of short homology arms (GeneWeld protocol). v. Donor vector carrying cargo DNA to be inserted at target site and homology arms, flanked by Universal gRNA Site (URS).

7. CONCLUSION

In addition to their role in developmental biology, zebrafish have emerged as tools for studying a variety of cancers, including those of the blood. Transgenic and xenograft models have been useful in studying leukemia and associating specific phenotypes to specific mutations and cancer subtypes, and have set the stage for future studies using more targeted approaches. With the advancement of new technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9, genomic DNA may be targeted in a more specific manner to more faithfully recapitulate human diseases in zebrafish.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Karilyn Sant and Cayleen Bileckyj for their reading of the manuscript.

Funding Information

This publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00HL133458 (awarded to SG).

Contributor Information

Brandon Molina, Biology Department, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, California, 92182, USA.

Jasmine Chavez, Biology Department, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, California, 92182, USA.

Stephanie Grainger, Biology Department, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, California, 92182, USA.

References

- Ablain J, Durand EM, Yang S, Zhou Y, & Zon LI (2015). A CRISPR/Cas9 vector system for tissue-specific gene disruption in zebrafish. Developmental Cell, 32(6), 756–764. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Duhier FM, Goodeve AC, Wilson GA, Gari MA, Peake IR, Rees DC, Vandenberghe EA, Winship PR, & Reilly JT (2000). FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations in adult acute myeloid leukaemia define a high-risk group. British Journal of Haematology, 111(1), 190–195. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alghisi E, Distel M, Malagola M, Anelli V, Santoriello C, Herwig L, … Mione MC (2013). Targeting oncogene expression to endothelial cells induces proliferation of the myelo-erythroid lineage by repressing the Notch pathway. Leukemia, 27(11), 2229–2241. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsterdam A, Varshney GK, & Burgess SM (2011). Retroviral-mediated Insertional Mutagenesis in Zebrafish-Chapter 4. In Detrich HW, Westerfield M, & Zon LI (Eds.), Methods in Cell Biology (Vol. 104, pp. 59–82). Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-374814-0.00004-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, & Vardiman JW (2016). The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood, 127(20), 2391–2405. 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong GAB, Liao M, You Z, Lissouba A, Chen BE, & Drapeau P (2016). Homology Directed Knockin of Point Mutations in the Zebrafish tardbp and fus Genes in ALS Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System. PLOS ONE, 11(3), e0150188. 10.1371/journal.pone.0150188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriazu E, Vicente C, Pippa R, Peris I, Martínez-Balsalobre E, García-Ramírez P, Marcotegui N, Igea A, Alignani D, Rifón J, Mateos MC, Cayuela ML, Nebreda AR, & Odero MD (2020). A new regulatory mechanism of protein phosphatase 2A activity via SET in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Cancer Journal, 10(1). 10.1038/s41408-019-0270-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten JT, & de Jong JLO. (2018). Genetic Models of Leukemia in Zebrafish. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 10.3389/fcell.2018.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balgobind BV, Zwaan CM, Pieters R, & Van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM (2011). The heterogeneity of pediatric MLL -rearranged acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia, 25(8), 1239–1248. 10.1038/leu.2011.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa K, Deshpande A, Chen B-R, Ghosh A, Sun Y, Dutta S, Weetall M, Dixon J, Armstrong SA, Bohlander SK, & Deshpande AJ (2019). Acute myeloid leukemia driven by the CALM-AF10 fusion gene is dependent on BMI1. Experimental Hematology, 74, 42–51.e3. 10.1016/j.exphem.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Abdelali R, Asnafi V, Petit A, Micol J-B, Callens C, Villarese P, Delabesse E, Reman O, Lepretre S, Cahn J-Y, Guillerm G, Berthon C, Gardin C, Corront B, Leguay T, Béné M-C, Ifrah N, Leverger G, Dombret H, & Macintyre E (2013). The prognosis of CALM-AF10-positive adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias depends on the stage of maturation arrest. Haematologica, 98(11), 1711–1717. 10.3324/haematol.2013.086082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley VL, Veinotte CJ, Corkery DP, Pinder JB, LeBlanc MA, Bedard K, Weng AP, Berman JN, & Dellaire G (2015). Focused chemical genomics using zebrafish xenotransplantation as a pre-clinical therapeutic platform for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica, 100(1), 70–76. 10.3324/haematol.2014.110742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand JY, Kim AD, Violette EP, Stachura DL, Cisson JL, & Traver D (2007). Definitive hematopoiesis initiates through a committed erythromyeloid progenitor in the zebrafish embryo. Development, 134(23), 4147–4156. 10.1242/dev.012385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betcher DL, & Burnham N (1990). Cytarabine. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing: Official Journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses, 7(4), 154–157. 10.1177/104345429000700406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn JS, Liu S, Raiser DM, Martinez SA, Feng H, Meeker ND, … Langenau DM (2012). Notch signaling expands a pre-malignant pool of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia clones without affecting leukemia-propagating cell frequency. Leukemia, 26(9), 2069–2078. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn JS, Liu S, Wilder JL, Dobrinski KP, Lobbardi R, Moore FE, … Langenau DM (2014). Clonal evolution enhances leukemia-propagating cell frequency in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia through Akt/mTORC1 pathway activation. Cancer Cell, 25(3), 366–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleicher KH, Böhm H-J, Müller K, & Alanine AI (2003). Hit and lead generation: Beyond high-throughput screening. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery, 2(5), 369–378. 10.1038/nrd1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli N, Payne EM, Grabher C, Lee J-S, Johnston AB, Falini B, Kanki JP, & Look AT (2010). Expression of the cytoplasmic NPM1 mutant (NPMc+) causes the expansion of hematopoietic cells in zebrafish. Blood, 115(16), 3329–3340. 10.1182/blood-2009-02-207225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolli N, Payne EM, Rhodes J, Gjini E, Johnston AB, Guo F, Lee J-S, Stewart RA, Kanki JP, Chen AT, Zhou Y, Zon LI, & Look AT (2011). Cpsf1 is required for definitive HSC survival in zebrafish. Blood, 117(15), 3996–4007. 10.1182/blood-2010-08-304030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond J, Touzart A, Leprêtre S, Graux C, Bargetzi M, Lhermitte L, Hypolite G, Leguay T, Hicheri Y, Guillerm G, Bilger K, Lhéritier V, Hunault M, Huguet F, Chalandon Y, Ifrah N, Macintyre E, Dombret H, Asnafi V, & Boissel N (2019). DNMT3A mutation is associated with increased age and adverse outcome in adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica, 104(8), 1617–1625. 10.3324/haematol.2018.197848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borga C, Foster CA, Iyer S, Garcia SP, Langenau DM, & Frazer JK (2019). Molecularly distinct models of zebrafish Myc-induced B cell leukemia. Leukemia, 33(2), 559–562. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0328-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borga C, Park G, Foster C, Burroughs-Garcia J, Marchesin M, Shah R, … Frazer JK (2018). Simultaneous B and T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias in zebrafish driven by transgenic MYC: implications for oncogenesis and lymphopoiesis. Leukemia, 33(2), 333–347. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0226-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G (2020). Towards a New Understanding of Decision-Making by Hematopoietic Stem Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(7). 10.3390/ijms21072362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G, Sánchez L, & Sánchez-García I (2020). Are Leukaemic Stem Cells Restricted to a Single Cell Lineage? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(1), 45. 10.3390/ijms21010045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti L, Gundry MC, & Goodell MA (2019a). New insights into the biology of acute myeloid leukemia with mutated NPM1. International Journal of Hematology, 110(2), 150–160. 10.1007/s12185-018-02578-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti L, Gundry MC, & Goodell MA (2019b). New insights into the biology of acute myeloid leukemia with mutated NPM1. International Journal of Hematology, 110(2), 150–160. 10.1007/s12185-018-02578-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butko E, Distel M, Pouget C, Weijts B, Kobayashi I, Ng K, Mosimann C, Poulain FE, McPherson A, Ni C-W, Stachura DL, Del Cid N, Espín-Palazón R, Lawson ND, Dorsky R, Clements WK, & Traver D (2015). Gata2b is a restricted early regulator of hemogenic endothelium in the zebrafish embryo. Development (Cambridge, England), 142(6), 1050–1061. 10.1242/dev.119180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli G, Pelosi E, & Testa U (2018). Targeting histone methyltransferase and demethylase in acute myeloid leukemia therapy. OncoTargets and Therapy, 11, 131–155. 10.2147/OTT.S145971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Streisinger G, & Walker C (1983). FREQUENCY OF Y-RAY INDUCED SPECIFIC LOCUS AND RECESSIVE LETHAL MUTATIONS IN MATURE GERM CELLS OF THE ZEBRAFISH, BRACHYDANIO RERIO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chang N, Sun C, Gao L, Zhu D, Xu X, Zhu X, Xiong J-W, & Xi JJ (2013). Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Research, 23(4), 465–472. 10.1038/cr.2013.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J, & Zhang Y (2020). Histology, Hematopoiesis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534246/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Gilbert LA, Cimini BA, Schnitzbauer J, Zhang W, Li G-W, Park J, Blackburn EH, Weissman JS, Qi LS, & Huang B (2013). Dynamic Imaging of Genomic Loci in Living Human Cells by an Optimized CRISPR/Cas System. Cell, 155(7), 1479–1491. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Jette C, Kanki JP, Aster JC, Look AT, & Griffin JD (2007). NOTCH1-induced T-cell leukemia in transgenic zebrafish. Leukemia, 21(3), 462–471. 10.1038/sj.leu.2404546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Stuart L, Ohsumi TK, Burgess S, Varshney GK, Dastur A, Borowsky M, Benes C, Lacy-Hulbert A, & Schmidt EV (2013). Transposon activation mutagenesis as a screening tool for identifying resistance to cancer therapeutics. BMC Cancer, 13(1), 93. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Li Q, Hudson WA, Kumar A, Kirchhof N, & Kersey JH (2006). A murine Mll-AF4 knock-in model results in lymphoid and myeloid deregulation and hematologic malignancy. Blood, 108(2), 669–677. 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Goh G, Walradt T, Hong BS, Bunick CG, Chen K, Bjornson RD, Maman Y, Wang T, Tordoff J, Carlson K, Overton JD, Liu KJ, Lewis JM, Devine L, Barbarotta L, Foss FM, Subtil A, Vonderheid EC, … Lifton RP (2015). Genomic landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nature Genetics, 47(9), 1011–1019. 10.1038/ng.3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S-H, Ko B-S, Chiou J-S, Hsu Y-C, Tsai M-H, Chiu Y-C, Yu I-S, Lin S-W, Hou H-A, Kuo Y-Y, Lin H-M, Wu M-F, Chou W-C, & Tien H-F (2012). A Knock-In Npm1 Mutation in Mice Results in Myeloproliferation and Implies a Perturbation in Hematopoietic Microenvironment. PLOS ONE, 7(11), e49769. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins EC, Pannell R, Simpson EM, Forster A, & Rabbitts TH (2000). Inter-chromosomal recombination of Mll and Af9 genes mediated by cre-loxP in mouse development. EMBO Reports, 1(2), 127–132. 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, & Zhang F (2013). Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science, 339(6121), 819–823. 10.1126/science.1231143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkery DP, Dellaire G, & Berman JN (2011). Leukaemia xenotransplantation in zebrafish – chemotherapy response assay in vivo. British Journal of Haematology, 153(6), 786–789. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08661.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral J, Lavenir I, Impey H, Warren AJ, Forster A, Larson TA, Bell S, McKenzie AN, King G, & Rabbitts TH (1996). An Mll-AF9 fusion gene made by homologous recombination causes acute leukemia in chimeric mice: A method to create fusion oncogenes. Cell, 85(6), 853–861. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81269-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti P, Young S, Chen C-Y, Patrick MJ, Rochon ER, Pekkan K, & Roman BL (2011). Interaction between alk1 and blood flow in the development of arteriovenous malformations. Development (Cambridge, England), 138(8), 1573–1582. 10.1242/dev.060467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crans-Vargas HN, Landaw EM, Bhatia S, Sandusky G, Moore TB, & Sakamoto KM (2002). Expression of cyclic adenosine monophosphate response-element binding protein in acute leukemia. Blood, 99(7), 2617–2619. 10.1182/blood.V99.7.2617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cully M (2019). Zebrafish earn their drug discovery stripes. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 18(11), 811–813. 10.1038/d41573-019-00165-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham L, Finckbeiner S, Hyde RK, Southall N, Marugan J, Yedavalli VR, … Liu P (2012). Identification of benzodiazepine Ro5–3335 as an inhibitor of CBF leukemia through quantitative high throughput screen against RUNX1-CBFbeta interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109(36), 14592–14597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200037109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo ME, Knebel A, Morrice N, Paterson H, Cohen P, & Mittnacht S (2008). P53-Driven apoptosis limits centrosome amplification and genomic instability downstream of NPM1 phosphorylation. Nature Cell Biology, 10(6), 723–730. 10.1038/ncb1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick MF, Libbey JE, Trede NS, Eckels DD, & Fujinami RS (2012). Human T cell expansion and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inhibited by Lenaldekar, a small molecule discovered in a zebrafish screen. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 244(1–2), 35–44. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daver N, Schlenk RF, Russell NH, & Levis MJ (2019a). Targeting FLT3 mutations in AML: Review of current knowledge and evidence. Leukemia, 33(2), 299–312. 10.1038/s41375-018-0357-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daver N, Schlenk RF, Russell NH, & Levis MJ (2019b). Targeting FLT3 mutations in AML: Review of current knowledge and evidence. Leukemia, 33(2), 299–312. 10.1038/s41375-018-0357-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AJ, & Zon LI (2004). The ‘definitive’ (and ‘primitive’) guide to zebrafish hematopoiesis. Oncogene, 23(43), 7233–7246. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AJ, & Zon LI (2006). The caudal-related homeobox genes cdx1a and cdx4 act redundantly to regulate hox gene expression and the formation of putative hematopoietic stem cells during zebrafish embryogenesis. Developmental Biology, 292(2), 506–518. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JLO, & Zon LI (2005). Use of the Zebrafish System to Study Primitive and Definitive Hematopoiesis. Annual Review of Genetics, 39(1), 481–501. 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.095931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boeck M, Cui C, Mulder AA, et al. : Smad6 determines BMP-regulated invasive behaviour of breast cancer cells in a zebrafish xenograft model. Sci Rep. 2016;6: 24968. doi: 10.1038/srep24968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kouchkovsky I, & Abdul-Hay M (2016). “Acute myeloid leukemia: A comprehensive review and 2016 update.” Blood Cancer Journal, 6(7), e441. 10.1038/bcj.2016.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hertog J (2005). Chemical Genetics: Drug Screens in Zebrafish. Bioscience Reports, 25(5–6), 289–297. 10.1007/s10540-005-2891-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detrich HW, Westerfield M, & Zon LI (2010). The zebrafish: Cellular and developmental biology, part A. Preface. Methods in Cell Biology, 100, xiii. 10.1016/B978-0-12-384892-5.00018-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau AP, Forrester AM, Coombs AJ, Wagner GS, Grabher C, Chute IC, … Berman JN (2015). Epigenetic therapy restores normal hematopoiesis in a zebrafish model of NUP98-HOXA9-induced myeloid disease. Leukemia, 29(10), 2086–2097. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson CL, Warren AJ, Pannell R, Forster A, Lavenir I, Corral J, Smith AJ, & Rabbitts TH (1999). The mll-AF9 gene fusion in mice controls myeloproliferation and specifies acute myeloid leukaemogenesis. The EMBO Journal, 18(13), 3564–3574. 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döhner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, Scholl C, Rücker FG, Corbacioglu A, Bullinger L, Fröhling S, & Döhner H (2005). Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: Interaction with other gene mutations. Blood, 106(12), 3740–3746. 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey OM, Cooper JL, Mupo A, Grove CS, Lynn C, Conte N, Andrews RM, Pacharne S, Tzelepis K, Vijayabaskar MS, Green P, Rad R, Arends M, Wright P, Yusa K, Bradley A, Varela I, & Vassiliou GS (2017). Molecular synergy underlies the co-occurrence patterns and phenotype of NPM1-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Blood, 130(17), 1911–1922. 10.1182/blood-2017-01-760595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon Y, McCammon JM, Miller JC, Faraji F, Ngo C, Katibah GE, … Amacher SL (2008). Heritable targeted gene disruption in zebrafish using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol, 26(6), 702–708. doi: 10.1038/nbt1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper BW, McCallum CM, Stout JL, Slade AJ, & Moens CB (2004). A high-throughput method for identifying N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced point mutations in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol, 77, 91–112. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)77005-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drynan LF, Pannell R, Forster A, Chan NMM, Cano F, Daser A, & Rabbitts TH (2005). Mll fusions generated by Cre-loxP-mediated de novo translocations can induce lineage reassignment in tumorigenesis. The EMBO Journal, 24(17), 3136–3146. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekker SC, Ungar AR, Greenstein P, von Kessler DP, Porter JA, Moon RT, & Beachy PA (1995). Patterning activities of vertebrate hedgehog proteins in the developing eye and brain. Current Biology, 5(8), 944–955. 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00185-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, Alcalay M, Rosati R, Pasqualucci L, La Starza R, Diverio D, Colombo E, Santucci A, Bigerna B, Pacini R, Pucciarini A, Liso A, Vignetti M, Fazi P, Meani N, Pettirossi V, Saglio G, … GIMEMA Acute Leukemia Working Party. (2005). Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. The New England Journal of Medicine, 352(3), 254–266. 10.1056/NEJMoa041974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fate Therapeutics. (2013). Safety and Efficacy of ProHema Modulated Umbilical Cord Blood Units in Subjects With Hematologic Malignancies. - Full Text View—ClinicalTrials.gov (Clinical Trial Registration No. NCT00890500). clinicaltrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00890500

- Fate Therapeutics. (2017). A Phase 2 Controlled Trial of a Single ProHema®-CB Unit (Ex Vivo Modulated Human Cord Blood) As Part of a Double Umbilical Cord Blood Transplant Following Myeloablative or Reduced Intensity Conditioning For Patients Age 15–65 Years With Hematologic Malignancies. (Clinical Trial Registration No. NCT01627314). clinicaltrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01627314

- Fate Therapeutics. (2018a). A Phase 1 Trial of a Single ProHema® CB Product as Part of Single Cord Blood Unit Transplant After Busulfan/Cyclophosphamide/ATG Conditioning for Pediatric Patients With Inherited Metabolic Disorders (Clinical Trial Registration No. NCT02354443). clinicaltrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02354443