Abstract

Background: Clinical decision support systems (CDSSs) interventions were used to improve the life quality and safety in patients and also to improve practitioner performance, especially in the field of medication. Therefore, the aim of the paper was to summarize the available evidence on the impact, outcomes and significant factors on the implementation of CDSS in the field of medicine.

Methods: This study is a systematic literature review. PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, EMBASE, and ProQuest were investigated by 15 February 2017. The inclusion requirements were met by 98 papers, from which 13 had described important factors in the implementation of CDSS, and 86 were medicated-related. We categorized the system in terms of its correlation with medication in which a system was implemented, and our intended results were examined. In this study, the process outcomes (such as; prescription, drug-drug interaction, drug adherence, etc.), patient outcomes, and significant factors affecting the implementation of CDSS were reviewed.

Results: We found evidence that the use of medication-related CDSS improves clinical outcomes. Also, significant results were obtained regarding the reduction of prescription errors, and the improvement in quality and safety of medication prescribed.

Conclusion: The results of this study show that, although computer systems such as CDSS may cause errors, in most cases, it has helped to improve prescribing, reduce side effects and drug interactions, and improve patient safety. Although these systems have improved the performance of practitioners and processes, there has not been much research on the impact of these systems on patient outcomes.

Keywords: Clinical decision support system, Medication, Significant factors, Patient outcomes, Systematic review

↑ What is “already known” in this topic:

• CDSSs can help to reduce ADEs, medication errors, DDIs, improve patient safety, and medicine prescriptions.

• CDSSs have the potential to promote practitioners’ performance.

• DSS can lead to improved care and patient safety.

→ What this article adds:

•Studies have shown that DSS has led to improvements in drug-related activities

• The integration of CDSS with other systems, in particular CPOE, is one of their key success factors, helping to enhance the effectiveness of the system.

• The participation of key personnel in the system development is also one of the key success factors of DSS system implementation

• Practitioners’ performance has also been improved with the use of DSS.

• Few studies have been conducted concerning the DSS effect on the outcomes of patients and economies, so it is recommended that further studies should be conducted in this regard.

• Almost all CDSS studies reported positive findings for clinical processes’ outcomes.

Introduction

Recently, extensive attention has been paid to reduce medical error and in particular, medication errors (1) as one of the most common errors in medicine (2, 3). Medication error is one of the main concerns of health care (2). According to the Institute of Medic ine report, nearly 80000 people are admitted to hospital in the United States every year from whom, 7000 die as a result of medication errors that 32-69% of them are definitely or probably preventable (4). The consequences of medication errors, in addition to complications (adverse events) in patients, result in the imposition of financial burdens on the health care system (3), in such a way that it harms at least 1.5 million people a year and adds $ 3.5 billion to the hospital costs (2).

Medication errors often occur during prescribing procedures (5, 6). One study reported that the incidence of prescription error was 3 to 99 errors per 1000 prescriptions in hospitalized patients, leading to adverse events (ADEs) (6), and drug-drug interactions (DDIs) (3) that by accessing timely information and having a sufficient knowledge base, such as using the computer physician order entry system (CPOE) system, CDSS, or both (1) are potentially preventable (7).

It seems that one of the most important strategies to reduce errors is to simplify the work procedures and limit paperwork (5).

Information technology (IT), by automating tasks and monitoring actions, can reduce workload and increase productivity; therefore, it can reduce errors (8), improve patient safety (3) and also solve human problems (7). As a result, the use of IT-based programs has attracted the attention of many healthcare settings (2, 3). CDSS as one of the IT-based interventions has been known as a promising strategy to prevent medication errors (9-15).

It has also been considered as one of the most effective and efficient tools for improving prescription, avoiding adverse events, and optimizing correct drug dosing (16). Computerized decision support through drug recommendations, drug-allergy checks, and DDIs advice can help to select a correct drug (17). Hunt et al. defined computer-based: "clinical decision-making programs designed to specifically assist in matching the characteristic features of each patient with a computerized information base to provide patient-specific evaluation or advice to be sent to the clinician" (18). In this study, we the term CDSS means the computerized physician order entry, the clinical decision support system, or electronic prescription.

DSS compliance with recommendations will enhance the ability to change behavior significantly, appropriately, and consistently. Thus, DSS may result in the appropriate entree to information, thus evidence use, clinical decision-making, and enhanced care quality. In addition, studies have shown that DSS, by reducing side effects, in addition to savings cost, increases the efficiency of patient care and saves the time of physicians (14). DSS can also collect information for easy examination, counseling, and provision of alternative suggestions that are not immediately become apparent to a clinical specialist. Therefore, one of the most important goals of CDSS is improving the quality of care and paying attention to safety features (19).

To our best knowledge, a number of systematic reviews (SRs) has been performed on CDSS impacts, but they have only reviewed a particular aspect of medication, such as drug prescription and management (20-23), ADEs (24), therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (25), DDIs (3), medication dosing assistants (26), reduction of prescription errors (27), reduction of unsafe prescription (28), medication safety (29, 30) and assisting in changing prescription practice (31). Many studies have also been conducted on the factors affecting the implementation of CDSS and several factors have been identified (3, 31-45). Therefore, in the present systematic literature review, we aimed to; comprehensively examine the effects of CDSS on more areas of medicine (reducing ADEs, DDIs, medication errors, prescription improvement, medication adherence, dosing, medication safety, and monitoring) rather than focusing on a particular aspect, to assess the CDSS impact on the performance of practitioner and outcomes of the patient, and finally to identify the most effective factors affecting the implementation of CDSS to help new developers.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, ProQuest, Scopus, besides databases of the Cochrane Library, were searched until 15 February 2017. The searches were not limited by language (studies in other languages were omitted due to incompatibility with the aim of this study).

The search strategy was based on a combination of the following two concepts: CDSS and significant factors affecting the implementation of CDSS. In this regard, the relevant systematic reviews were identified and then screened for inclusion.

The search query for the PubMed database is as follows:

1- ("systematic review" OR "meta analysis")

2- (“Decision Support System” OR “Clinical Decision Support System” OR “Clinical Decision Support” OR (Decision Support AND Clinical) OR (Support AND Clinical Decision))

3- (Achievement OR “success factors” OR “system success” OR “effective systems” OR “effectiveness of CDS systems” OR “critical factor” OR “key features” OR “features critical” OR Effect OR “features effective” OR effectiveness OR “Impact Assessment” OR Influence OR improvement OR quality OR safety OR efficacy OR “quality assurance” OR Enhancing OR development OR “Cost effectiveness” OR “cost-effectiveness”)

4- 1 AND 2 AND 3

Selection of studies

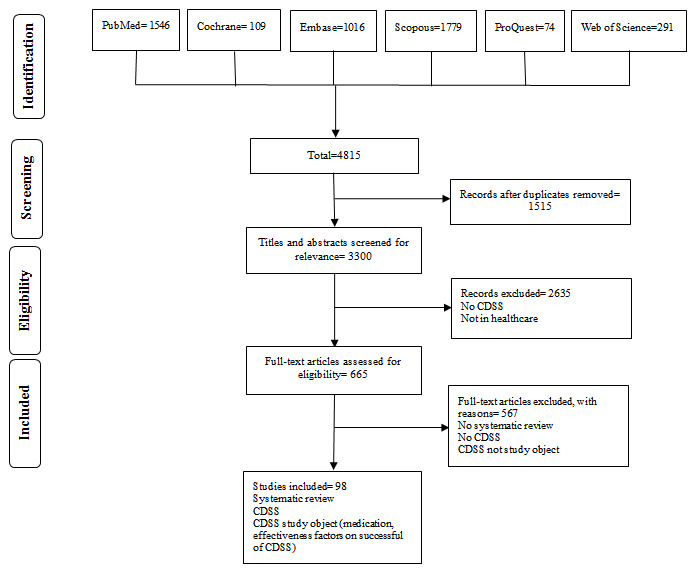

The search results were entered into the EndNote software, and the duplicates were removed and re-checked manually. The articles were then screened based on the titles and abstracts. A total of 665 articles was identified. By reviewing the full text of the articles, 98 papers were eventually included in our study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded studies

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The systematic reviews assessed the CDSS efficiency in the field of medication were included in this review, including prescription, dosing, reducing medication errors, drug monitoring, Rx CDSS, medication management, medication safety, ADE, drug allergy, and DDIs. We included studies if they had; 1) assessed CDSSs (including clinical decision support system, electronic prescription, and computerized physician order entry system) that had been implemented in the field of medication such as; medication prescription, reducing medication errors, ADEs, drug-allergy checking, drug dosing support, and etc., and 2) evaluated significant factors affecting CDSS implementation. We excluded non-systematic review studies, commentaries, opinion papers, editorials, conference proceedings, summaries etc.

Review procedures and data extraction

We extracted data to summarize the key features of systematic reviews, including information about the researcher and publication year, research objective, assessed outcomes, and the review’s results, as well as information about significant factors affecting CDSS implementation in the included studies.

Three thousand three hundred electronic records (after eliminating copies) were recognized using a combination of search techniques, and then they were examined for eligibility. First, all titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers independently to distinguish related investigations on the basis of the present research aims. For a full review, 665 hypothetically eligible works were chosen among the citations. In the next stage, to be included in the final review, the full-text papers independently were reviewed in detail based on the above-mentioned inclusion criteria. Any disagreement was resolved either through discussion or involving a third reviewer. In order to handle citations, Endnote version X7 was applied.

Classification of interventions and research outcomes

The system was classified in terms of its correlation with medication in which a system was implemented, and our intended results were examined. In this review, the interest outcomes, in turn, were classified as the process outcomes (e.g., prescription, drug-drug interaction, drug adherence, etc.), patient outcomes, and significant factors affecting the implementation of CDSS.

Results

Description of the studies

PRISMA flow diagrams of included and excluded studies are shown in Figure 1. In total, 4815 publications were obtained with the search strategy, from which 3300 studies remained after the duplication removal. We screened the titles and abstracts and also reviewed the full text of 665 articles. Finally, 98 articles met the inclusion criteria from which 86 were medicated-related, and 13 had reported the successful system implementations.

About a third (27/85, 31.7%) of the articles were focused on prescription (14, 23, 32, 40, 46-68), eight reviews had evaluated interventions which were aimed at ADEs (24, 69-75), four studies had followed the drug dosing (25, 76-78), nine reviews were focused on medication error reduction (22, 27, 71, 74, 79-85), five reviews were about medication management (1, 20, 86-88), five reviews had discussed medication practice (89-93), six studies had assessed the effect of system on medication use (94-99), four reviews were about medication safety (28-30, 100), two reviews were on medication monitoring (25, 101) one review was about medication adherence (102), one study had assessed the impact of DDIs (13), thirteen reviews were focused on the effects of CDSS on practitioners’ performance and outcomes of patients (21, 26, 103-113) and thirteen reviews had analyzed the significant factors affecting CDSS implementation (35-38, 43, 107, 114-120).

Synthesis of evidence (interventions’ Efficiency)

In this part, study results were classified based on medication-related processes, patient outcomes, besides significant factors affecting the implementation.

Impact on the medication-related processes

Impact on processes of prescribing:Of twenty-seven studies investigatingprescribing-condition, twenty-four studies showed positive effects such as prescription improvement, improvements in appropriateness of drug prescription, reduction in prescription errors, optimizing prescriptions, and reducing unsafe or unnecessary prescription (14, 23, 32, 40, 46-52, 55, 57-68), and also three studies demonstrated the effectiveness of CDSS on prescription improvement that were not convincing (53) and required more investigation (54, 56).

Impact on adverse drug events (ADEs):Three out of eight studies showed an improvement in reducing drug side effects (24, 71, 74). Results of other studies have shown that using integrated DSS with CPOE prevent prescription of medications that cause side effect (69). Predicting ADE in clinical settings (72), and reducing ADE by 50% using COPE were among other benefits of this system (73). Other studies either did not show any changes in ADE rate or showed a non-conclusive effect of the system on ADE (121, 122). This information is given in Table 1.

Table 1. The effect of CDSS on ADEs .

| References | CDSS focus ( study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (24) | The relationship between CPOE with CDS and the occurrence of an adverse drug event (ADE) | Decreased ADEs | 80% decrease in ADEs by using CPOE with CDS |

| (69) | Identification of automated/non-automated systems that can eliminate/reduce prescriptions that may cause ADEs at the patient level and their effectiveness | Eliminate/reduce prescriptions | Various systems, including CPOE with DSS can reduce/eliminate prescription of medications that cause ADEs. However, little evidence exists for supporting that. To show the benefits of such systems in medical care, further studies are required. |

| (70) | Assessing the effect of computerized laboratory alerts on lowering ADEs rate and process outcomes | Promotion of choosing clinical outcomes and process outcomes | No evidence exists about the usefulness and benefits of computerized clinical alerts. However, there was some improvement in process outcomes, including changes in laboratory behaviors and prescribing behavior. Therefore, more evidence is needed to prove the usefulness of such systems in electronic medical records. |

| (71) | Assessing the effect of CPOE on elimination/decrease in medicine errors and ADE | Elimination/decrease in medicine errors and ADE | Findings showed that automated prescription and decision support system could be useful in the elimination/decrease in medicine errors and ADE in clinical settings such as hospitals. |

| (72) | Assessing various clinical alerts such as pharmacy and laboratory signals currently used to measure ADEs in hospital | Promoting ADEs’ detection | The results showed that clinical alerts such as pharmacy and laboratory signals had been improved to identify ADEs. However, more research on this subject is needed to assess the use of such signals and CDS systems in different settings and analyze the system economically. |

| (73) | Detecting factors that are most effective in the elimination/reduction of medication error and evaluating the effect of CPOE in the elimination/reduction of preventable ADEs. | Substantial decrease in medication errors and preventable ADEs | More than 50% use of CPOE to decrease preventable ADEs and medication errors |

| (74) | Measuring the cost-effectiveness of CPOE and its capability to eliminate/reduce preventable ADEs and medication errors | Elimination/reduction of preventable ADEs and medication errors | The combination of CPOE and decision support systems can eliminate/reduce SDEs and medication errors |

| (75) | Measuring the capability and economic usefulness of drug interaction detection software (DIS) in elimination/reduction of ADEs | ADEs’ rate did not change | The outcomes of DIS (benefits, consequences, and economic usefulness) and its effect on drug safety were not detected. |

Impact on drug dosing: As presented in Table 2, In this category, studies reported that CCDSS could help to improve the care process through drug monitoring and dosing (25), increase the initial dose of the drug with computerized recommendations, reduce the time spending in hospital (77, 78) and control the treatment faster through dose adjustment (76).

Table 2. The effect of CDSS on drug dosing .

| References | CDSS focus (study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (25) | Evaluating the effect of CCDSS on therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (TDMD) | Therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (TDMD) process improved | CCDSS can improve the therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (TDMD) process, especially vitamin K and insulin dosing. However, CCDSS should be developed further and then it should be assessed through different studies using different research methods, particularly in terms of drug safety and patient outcomes. CCDSS can improve the therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (TDMD) process, especially vitamin K and insulin dosing. |

| (76) | Assessing the capability of a computerized decision-making system in anticoagulant treatment | The computerized decision-making system improved dose adjustment | Findings referred to the ability of CDSS in adjusting the dose of anticoagulant |

| (77) | The effect of electronic advice on medication dosing | Major reduction in the toxicity of the drug, an increase in serum concentration and primary, dosing and shorter treatment time and hospitalization, thus, no effect on side effects. | Computerized medication dosing had many benefits, including a major reduction in the toxicity of drugs, an increase in serum concentration and primary, dosing, and shorter treatment time and hospitalization, thus, no effect on the side effects. |

| (78) | Evaluating the computerized medication dosing compared to non-computerized medication dosing | Computerized medication dosing has many benefits, including increased serum concentrations, reduced hospitalization, and significant reduction of side effects |

Impact on medication errors: Almost half of the studies (44%) showed that, CDSS system, particularly when integrated with CPOE, lead to a reduction of medication error (27, 74, 80, 84). Other studies have pointed to the effectiveness of electronic prescribing in the reduction of medication error and ADE (71). Moreover, HIT especially DSS, has helped to improve the quality of care by improving disease assessment and compliance with clinical guidelines as well as reducing medication errors (82). DSS models have helped the physicians in selecting collect systems to achieve significant outcomes such as reduction of medical and medication errors (22). However, a study showed that interventions could not exclusively be effective in reducing medication errors (79), as are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. The effect of CDSS on medication errors .

| References |

CDSS focus ( study objective) |

Effect measures | Main findings |

| (79) | Assessing the effect of different interventions on reduction of medication errors in critical care units | Reduction of medication errors | Clinical decision making (SSCD) support system decreased medication errors by 67%. However, there is not much evidence to suggest that such systems can reduce medication errors. |

| (80) | Assessing the effect of different interventions on reduction of medication errors in NICUs | Reduction of medication errors | CPOE with a decision support system, medication errors, and ISs may decrease medication errors |

| (22) | Evaluating the effects of Decision Support System (DSS) in the health care | improving the care quality and patient safety, including elimination/reduction of medication and clinical errors, increasing the economic efficiency, and increase the knowledge of staffs | Decision-making support system (DSS) increased compliance with standard care and medication guidelines and also helps healthcare professionals to eliminate/reduce medication and clinical errors. It also increased economic efficiency and consequently increased the quality of care. |

| (27) | Assessing the effect of different interventions on reduction of medicine errors in children's wards | Reduction of medication errors | Medication errors in pediatric wards will be reduced if correct and standard definitions are to be used, and also assessing economic efficiency would also help to achieve desired outcomes |

| (71) | Evaluating the risk of medication error and ADE by CPOE. | Decrease in medicine error and ADE risk | A computerized prescription system is an effective tool that can eliminate/reduce medication errors and ADEs in clinical settings |

| (74) | Assessing the advantages and barriers to the implementation of the CPOE system in clinical settings, and also assessing the effects of the system in ADEs and medication errors | Decrease in medical errors and ADEs, | The combination of CPOE and CDSS systems can potentially eliminate/reduce medication errors and ADEs. The unwillingness of healthcare professionals and the high implementation costs are among the barriers |

| (84) | Assessing the effect of CPOE on patient safety | CPOE system has a better effect on medication errors and ADEs when is used concurrently with CDSS resulting in increased patient safety | Significant reduction in medication errors and ADEs were not seen when a CPOE system alone was implemented; however, the combination of CPOE and CDSS had a greater impact on medication errors’ reduction and increased patient safety |

| (82) | Evaluating the health information technology impacts on quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of care | Information technology increased the adherence to care based on guidelines, improved monitoring/surveillance, and reduced medicine errors. | The majority of research has been conducted on CDS and electronic health record systems. Several interventions influenced the quality of care, such as increasing adherence to care based on guidelines, improving monitoring/surveillance, and reducing medicine errors |

| (85) | Studying the features of electronic Patient Medication Record (ePMR), including alerts and patient safety measures during the prescribed time at the pharmacy |

Patient Medication Record (ePMR) was effective in alerting staffs about clinical risks |

The features of the electronic Patient Medication Record (ePMR), including alerts and patient safety measures, were effective in alerting staff about clinical risks during the prescribed time. There were also some problems, including false alerts and performance inconsistencies. More study is needed on this subject in different countries and settings. |

Impact on medication management:In regard to the effects of DSS on medication management, as presented in Table 4, studies have shown that such systems promote the quality of care and improve medication management (86). The use of DSSs that offer reminders and feedback is beneficial in improving medication use and different behaviors related to medication management (1). However, few studies have been conducted on patient safety threats or monitoring of side effects (20).

Table 4. The effect of CDSS on medication management .

| References | CDSS focus ( study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (1) | Evaluating the effects of computerized systems (reminders or feedback) to support medication management of patient safety and medication management | Enhanced patient safety and adherence to medication regimen, enhanced medication management, enhanced generic prescribing of medication | Computerized systems (reminders or feedback) can enhance medication management. Factors that affect implementation should also be considered |

| (20) | Exploring the effects of different intervention such as medication management in ambulatory care on patient safety | In general, no risk to patient safety was found | There is no evidence to suggest that, implementation of electronic medication management systems in ambulatory settings can potentially cause risks or harms to patients |

| (86) | Exploring the effect of medication management information technology (MMIT) on all medicine management phases | Enhanced prescribing behavior, adherence to medication advice, and reduced costs | MMIT enhanced medication management. The care quality was improved by approximately half of the MMIT interventions; however, little research has evaluated clinical outcomes |

| (87) | Exploring the effects of multifaceted interventions in the improvement of depression outcomes in primary care | Promote more active medication management | Factors, including qualified care managers, patient support system, patient education, continuous monitoring, and decision support system is important in medication management |

| (88) | Exploring the effects of health information technology on all stages of the medication management process (drug prescribing, ordering, communication, dispensing, administration, and monitoring as well as education and reconciliation). | Moderate to significant improvement in care with the implementation of MMIT | Studies that have been investigating the cost-effectiveness and clinical outcomes of the MMIT system had ambiguous results. However, some qualitative studies have found different perceptions of MMIT effects and outcomes. |

Medication practice:Almost all studies have shown the effect of DSS on the medication interventions, outcomes improvement, drug safety and reducing medication errors (91), promotion of professional activity, change in the field of alcohol and other drugs (AOD) using of reminders or feedback (93), and reduction of the cost (92). These are presented in Table 5.

Table 5. The effect of CDSS on Medication practice .

| References | CDSS focus (study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (89) | Identifying electronic decision support systems that directly support pharmacists in the hospital or community settings | Enhanced medication therapy | Very little evidence exists in the literature that explores electronic decision support system activities for pharmacy or pharmacists, in comparison to the countless related literature for healthcare. |

| (90) | Exploring the implementation of clinical guidelines in pharmacies | CDSS had a significant effect on the outcomes | Currently, very little evidence exists to prove that, implementation of clinical guidelines has a positive impact on outcomes of patients. No evidence exists to suggest the best implementation method |

| (91) | Evaluating the health IT impact on the quality, safety, and efficiency of healthcare | Positive effect on patient safety reduced medication errors | Many studies referred to the benefits of using CDSS and CPOE. Many studies that have explored the effect of implementing health IT on patient improving patient safety and reducing medication errors |

| (92) | Improved adherence to guidelines, increased overall prescription time, increased in unattended alerts | Improved adherence to guidelines, increased overall prescription time, increased in unattended alerts | Not much evidence exist to demonstrate that CPOE systems improve safety and decrease costs in outpatient situations. Nevertheless, many studies have found evidence in favor of improved adherence to guidelines, increased overall prescription time, increased in unattended alerts |

| (93) | Identifying the most effective strategies related to alcohol and other drugs (AOD) | The use of reminders had a moderate to significant effect on process outcomes. Improved prescribing and adherence to guidelines. Major improvement in professional practice and client outcomes. Reminders should be used in general medicine clinics to improve alcohol counseling. Feedback indicated 1-16% improvement in professional practice. |

The results suggested the use of d reminders and feedback to improve AOD. More specific studies are required to explore the use of reminders and feedback in AOD-related activities in clinical settings. |

Impact on medication usage: Table 6 shows that half of the studies have been examining the interventions that facilitate the proper use of polypharmacy in elderly people, which indicated the improvement in reduction of incorrect prescription (94, 98, 99). Furthermore, strategies such as electronic alarms have been proven to be effective in the better use of medications, especially in the short term (95). Studies have shown that the decision-making support system and the use of medication were the most common practice and strategies (56%), (96).

Table 6. The effect of CDSS on Medication usage .

| References | CDSS focus (study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (94) | Evaluating effective interventions in reducing medication- problems and enhancing the suitable application of polypharmacy in the elderly. | Substantial decrease in medication errors and ADEs. | Interventions for improving suitable polypharmacy, like pharmaceutical care, led to clinically significant improvement are yet to be proved; however, the interventions are believed to reduce inappropriate prescribing and medication errors |

| (95) | Exploring interventions to enhance medicine use in controlled care organizations (MCOs). Specifically in the US managed care setting. |

Decreased antibiotic prescribing. Enhanced recommended laboratory drug monitoring. Increased overall medication use. A substantial rise in anti-depressant adherence |

Many studies indicate the changing of drug use in the US managed care setting. Computerized alerts can improve short-term outcomes. Few well-designed studies are yet to test their effect on patient outcomes. |

| (96) | Examining the interventions’ efficiency to decrease low-value treatment. | Reduction in inappropriate prescription acid-suppressive medications. | The studies on decision support targeting drug use were most common. The most significant influence on low-value treatment is multidimensional interventions that consider both patient and provider functions in medication overuse. Although there are comparatively high data on the effectiveness of clinical decision support, it requires more investigation and development. |

| (97) | Assessing interventions’ impacts in order to assist consumers in using medications safely and efficiently. | Improvements in medicines use and adherence. Reduction in adverse events and improved clinical outcomes. |

The most-reported outcome was adherence to the medication regimen. The results of this overview can be used by decision-makers in implementing interventions for improving medication use by consumers to realize the best ones for enhancing particular outcomes. |

| (98) | Summarizing effective interventions in reducing medication- problems and enhancing the suitable use of polypharmacy in the elderly | Decreased inappropriate poly-pharmacy. Enhanced adherence to medication. | Interventions for improving suitable polypharmacy, like pharmaceutical care leading to significant improvement clinically, are still to be demonstrated. They seem, however, useful in decreasing unsuitable prescriptions. |

| (99) | Evaluating the systematic reviews on enhancing the suitable use of polypharmacy in the elderly | Decreased inappropriate prescribing |

Cochrane reviews summarized in this article emphasize the lack of intervention research on enhancing the proper polypharmacy use in old patients. Generally, the interventions mentioned in the review revealed benefits in this regard on the basis of a perceived reduction in unsuitable prescriptions. Nevertheless, if the interventions may result in significant clinical improvements concerning hospital admissions, medication-associated issues, and life quality of patients are yet to be established. Guidance associated with intervention enhancement, assessment, and report would assist in further future research. |

Impact on medication safety:Various studies have been conducted on drug safety and the use of different approaches, which indicated that DSS, in particular when integrated with CPOE, has been associated with the reduced drug errors and improved drug use (30). DSS leads to improvements in care processes and reduction of drug errors and positively effects drug dosing and patient outcomes (29). Also, these interventions have a significant impact on reducing the risks to safety, which consequently leads to a significant reduction in drug errors, especially during the interaction between the doctor and the pharmacist (28) as presented in Table 7.

Table 7. The effect of CDSS on Medication safety .

| References | CDSS focus (study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (28) | Evaluating the effect of IT intervention in the improvement of drug safety in primary care. |

CDS reduced the rate of inappropriate prescriptions |

In general, IT interventions are believed to decrease medication errors. However, IT interventions are not without safety hazards. |

| (29) | The effect of CDSS on drug safety. |

Decrease in medicine error (dose /prescription). enhancement in medicine dosing, care process, and outcomes related to medicine/drug |

CDSS decreased medicine error and enhanced the care process; however, it did not improve outcomes significantly. CDSS, reminders, or medicine alerts may enhance courses of care outcomes; CDSS associated with medicine dosing has the potential to improve patient outcomes. |

| (30) | Improving drug safety by using CPOE and CDSSs. | Reduced medication error rates. | CDSSs and CPOE may dramatically decrease medicine error and provide further vital benefits associated with the use of medicine. |

| (100) | Exploring different interventions to prevent drug safety in hospitals. | Improvement in safety, medication administration, and reduction of drug errors. | Evidence suggests the effectiveness of interventions in reducing medicine errors and negative drug measures. However, the results of a number of studies contradict this. |

Impact on monitoring practices:Nieuwlaat et al. concluded that, for therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (TDMD), CCDSSs help to improve the process of care, but there are no clear results about their effect on patient outcomes(25). Fischer et al. showed that, regarding the role of HIT interventions in monitoring laboratory drugs for ambulatory settings, there are not many studies and conclusive evidence; therefore, more research is needed to clarify it (101). This information is presented in Table 8.

Table 8. The effect of CDSS on medication monitoring .

| References | CDSS focus (study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (25) | Evaluating the effects of CCDSS effects on therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (TDMD) in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | Improved therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing (TDMD) | CDSS can improve TDMD, particularly in the dosing of insulin and vitamin K; however, it needs to be further developed |

| (101) | Identifying studies that have investigated the HIT interventions to enhance laboratory observing of chosen high-risk drugs in the ambulatory situation. | The was not enough evidence to demonstrate the HIT impact in enhancing laboratory observing of particular high-risk drugs for ambulatory patients | Overall, practically half of the randomized controlled experiments demonstrated major enhancements in the laboratory observing of particular high-risk drugs. However, The was not enough evidence to demonstrate the effect of HIT in improving laboratory observing of particular high-risk drugs for patients in ambulatory settings; thus, more studies are required. |

Impact on medication adherence and Drug-drug interactions (DDIs): Table 9 indicate that studies on drug adherence and drug interactions, IT-based interventions, especially DSS, have been the most effective interventions to improve drug adherence and drug interactions (13, 102).

Table 9. The effect of CDSS on medication adherence and Drug-drug interactions (DDIs) .

| References | CDSS focus ( study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (102) | Assessing the most effective factors that influence patients’ adherence to medication therapy in patients with osteoporosis | Patient adherence to drugs improved | Findings indicated that factors such as making dosing regimen simpler, patient decision making support system, patient education, and electronic prescription system were most effective in patients’ drug adherence in patients with osteoporosis. However, the patient decision making support system was the most effective factor. |

| (13) | Evaluating the effects and characteristics of computerized interventions on the outcomes of DDI | Increasing DDI alert adherence and clinical outcomes with computerized interventions | The results showed that DDI alert adherence and clinical outcomes were increased by computerized interventions. The effect of DDI on the medication-related issues such as drug prescription, administration, and dispense at decision making time |

Impact on practitioners’ performance and patient outcomes

In Table 10, thirteen studies showed the positive impact of DSS systems on the quality and efficiency of care (21, 26, 103-113). CPOE and DSS have had a positive effect on patient safety outcomes (113), and have played an important role in the various aspects of drug management, patient outcomes, and cost-cutting (112). Bright et al. reported that CDSS is less effective in clinical and economic activities, and its success depends on providing the correct information at the right moment to the right person (109). With the integration of DSS with workflow, these systems can help improve professional performance in promoting preventive care, medication order, and adherence to guidelines. Computer reminders can lead to improvements in drug interaction warnings, drug prescriptions, and test orders (105, 108). Also, some studies have shown that DSS can improve the performance of experts by up to 76% using reminders and up to 66% using drug prescription or dosage systems, and also it can improve patient outcomes by up to 13% (107). In almost all of these studies, the impact of DSS on patient outcomes has been less widely considered therefore, we can hardly be conclusive about its impact.

Table 10. The effect of CDSS on practitioners’ performance and patient outcomes .

| References | CDSS focus ( study objective) | Effect measures | Main findings |

| (107) | Assessing the effectiveness of CDSSs on practitioner performance and patient outcomes. | Improve practitioner performance, diagnosis, disease prevention and management, and drug dosing and prescribing. | CDSS system improves practitioner performance. However, more studies are required to demonstrate the effects of such systems on patient health. |

| (106) | Assessing the CDSS system impact on the performance of clinician and outcomes of patient |

improved clinical performance in drug dosing, disease prevention |

CDSS may enhance the care quality |

| (105) | Evaluating the effect of a CDSS on the performance of practitioners and outcomes of patients in hospitals | Positive effect on practitioner performance and patient outcome when combined with systems of drug prescription and preventive care reminder | CDSS can have a positive effect on the performance of practitioners and outcomes of patients when combined with preventive care reminder systems and drug prescribing system. CDSS is constantly developing and changing, so newer CDSS systems probably have a greater effect on the performance of practitioners and outcomes of patients |

| (104) | Evaluating CDSS impacts on the performance of clinicians and outcomes of patients | Improved dosing of toxic drugs, quality of preventive care, and patient outcome | Various CDSSs can improve practitioners’ performance. In order to evaluate their impacts and cost-efficiency on outcomes of patients, in particular, more research is required. |

| (21) |

assessing CCDSS impacts on courses of care and outcomes of patients through a cumulative synthesis of related RCTs. |

Improved process of care and patient outcomes | CCDSSs improved the process of care measures and patient outcomes. There was not enough evidence to support patient benefit, harms, and cost-effectiveness in adopting CCDSSs for managing drug treatment. |

| (26) | The role of CCDSSs in the management of medical issues in acute care situations | Improved the process of care in medication dosing and management, alerts/reminders, management, adherence to guidelines and diagnosis | CCDSSs improved the care course; however, outcomes of patients were not evaluated |

| (103) | Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of CDSSs and KMSs, identifying features that influence the success of CDSSs/KMSs, evaluating the impact of CDSSs/KMSs on outcomes, and identifying knowledge that can be integrated into CDSSs/KMSs | The health care process was enhanced by CDSSs/KMSs | Various types of CDSSs/KMSs (systems established locally and commercially) are efficient in healthcare process development in different settings. They're not much evidence on the effectiveness of CDSSs in clinical outcomes and costs. |

| (108) | Reviewing the studies conducted on CDSS and the integration of CDSS into the workflow | Improved disease prevention, adherence to guidelines, and integration into the workflow. | Clinical decision support systems and practitioner performance are important; however, new technologies like them can create new challenges such as data inaccuracies, which may affect the workflow. Therefore, there is a need for further development of such systems to suit the needs of users |

| (112) | Identifying ways to promote the use of antibiotics through an electronic prescribing system in a clinical setting | Enhanced dosing and choosing of antibiotics, enhanced adherence to clinical guidelines, reducing the use of antibiotics to prevent antibiotic resistance, reduced prescription and prescription errors, and reduction in negative medicine measures, duration of hospital stay, and drug hypersensitivity and reaction | CPOE and CDS were the main interventions, but various aspects of drug management were also included. Clinical assessment such considers various factors, including processes, cost-effectiveness, and outcomes in order to better educate the public |

| (109) | Assessing the CDSS impact on clinical outcomes, workload and effectiveness, health care courses, cost, and patient satisfaction, | Positive effect on drug prescribing, preventive care, and clinical outcomes | CDSSs are effective at improving the health care process in diverse settings. However, more evidence is needed for clinical, economic, workload, or efficiency outcomes. |

| (110) | Evaluating the care courses and outcomes using decision support system and computer reminders at the care point | enhanced prescribing behaviors, minor to modest care enhancements | Computer reminders significantly improved care at the point of care. Insignificant improvements across a range of processes. However, in order to implement clinical information systems, the prospect of offering computerized reminders at the care point signifies a substantial drive. In order to ascertain crucial elements that facilitate or predict care promotion, further research is needed. |

| (111) | Exploring the relationship between HIT and medical practices and other health care and providing information for stakeholders to promote and maximize the uptake of HIT. | Considerable increase in physician compliance to drug type and dosage recommendation, reduction in pharmacists’ interventions for incorrect drug doses. | The results of this study may help the adoption of HIT/HIS and increase the uptake of evidence-based practice using HIT/HIS. |

| (113) | Investigating the health IT effects on safety outcomes of patients in all clinical areas. | Positive impact on patient safety outcomes. | There is a need for further research in different sceneries to comprehend better how health IT influences patients. |

Significant factors affecting CDSS implementation: In this section, we describe the most important factors affecting the implementation of CDSS mentioned in the studies as presented in Table 11.

Table 11. Significant factors affecting CDSS implementation .

| References | Result (critical factors in the implementation of CDSS) |

| (37) | Human, organization, and technology factors |

| (123) | External context, the need for supportive laws and regulation, proper standards, policies and incentives, right organization condition, matching innovations with workflows, staffs’ knowledge and beliefs, processes and systems |

| (32, 115, 123) | Integrating systems in current organizational workflow |

| (119) | Users’ perceptions of significant factors in implementation, and technical and organizational support |

| (3, 43, 114) | The systems integration into other systems |

| (43) | Reasons for counseling, providing simultaneous advice to practitioners and patients, as well as |

| (42, 117, 118, 123) | Engagement of key personnel in the system development and implementation processes |

| (41, 42, 117, 118) | Support of managers and key personnel, training and monitoring the system in the early stages of implementation |

| (120) | structure of healthcare organizations; information and decision processes; work policies and staffs’ incentives |

| (38) | Quality of the system and information, and usability of the system |

| (32, 115) | Hardware availability, technical support, and appropriate clinical messages |

| (42) | Features of the system itself and a supportive and appropriate environment to improve the quality of patient services |

| (31, 33, 35, 40) | The need for the predictive role of specific systems or organizational features |

| (45) | Appropriate attitude and skills of user with good leadership, appropriate IT environment and effective communication |

| (114) | Implementation of interventions by the system, the lack of user control over output, the retrieval of data from the electronic medical record and CPOE |

| (34, 35, 44) | Level of computer interface, provision of advice at the right time for decision making |

| (36) | Provision of an automated decision support system |

| (39) | Executive support, understanding the business, IT-business relations, and leadership |

| (42, 123) | Appropriate and right infrastructure and resources |

| (118) | Users’ experience and training |

In general, the findings of this study showed that most studies (about 30%) have considered key employees’ participation in the system development process (42, 117, 118, 123), support of key managers and personnel, training and monitoring of the system in the early stages of implementation (41, 42, 117, 118), and the need for the predictive role of specific systems or organizational features (31, 33, 35, 40) as the most important factors. Approximately 23% of the studies have considered factors such as integration of the system with other systems such as CPOE (3, 43, 114) and organizational workflow (3, 43, 114), and also implementing the system at the right time (34, 35, 44), and about 15% of the studies have considered the infrastructure and adequate resources (42, 123) as effective factors. In other studies, factors such as the provision of advice for practitioners and patients, and providing CDSS by the developers of the system (43), factors of the human, organizational and technology (37), user groups’ perceptions of significant factors affecting the implementation, technical and organizational support (119), the structure of healthcare organizations, information and decision processes, people policies, tasks, and incentives (120) have contributed to the success of the system.

Discussion

Main findings

Previous studies have often measured the effects of CDSS on a particular area of medication, such as a prescription. However, to the best of our knowledge, these systematic reviews have not evaluated a wide range of areas. Therefore, this overview provides a comprehensive picture of the effects of CDSS on more aspects of the medication, such as reducing ADEs, DDIs and drug errors, improving prescription, drug adherence and dosage, drug safety and monitoring rather than focusing on a particular aspect. The present study also evaluated the CDSS impact on the performance of practitioners and outcomes of patients; finally, it identified the most effective factors affecting the implementation of CDSS to help the new developers.

We found evidence that the use of medication-related CDSS improves clinical outcomes. Also, significant results were obtained regarding the reduction of prescription errors and the improvement in quality and safety of medication prescribed. These findings are in line with the results of other studies (33, 124-132). In relation to ADEs, significant improvements have been achieved in the clinical results of ADEs, which has been associated with clinical outcomes in other studies (133-136). Whereas in King et al.'s study, similar effects of ADEs were not found (137). Ranji et al. also showed that the possibility of error occurrence would be reduced if such programs are applied carefully, and the production of safer care systems is more closely followed (138). In regard to the reduction of medication errors, as with other studies, our findings showed that CDSS is one of the most effective strategies to reduce the risks of medication errors (137, 139-145). Our findings showed that CDSS could help physicians to determine the optimal dosage of the drug in proportion to the patient's need, reduce unwanted side effects of the drug, and increase the benefits of treatment, which are consistent with the existing literature (146-150). Furthermore, when CPOE systems are integrated into a CDSS to alert doctors and other health care providers, the reduction of laboratory or medical errors and improvements in medication safety are significant. This is in accordance with the result of other studies (126, 151, 152). Kausha et al. showed that IT interventions might not be able to fully resolve drug safety issues, but they seem to be an effective approach (142). As seen in studies of Bindoff et al. and McCoy et al. (153, 154), our findings showed that CDSS systems could facilitate and improve medication management.

Drug-drug interactions are one of the most important and preventable issues through these systems. Tilson et al. reported that a process should be used to develop and maintain a standard set of DDIs for CDSS (155). Böttiger et al. concluded that, when paired with a clinical decision support system for DDIs, SFINX can be a useful instrument if employed (156). Saverno et al. showed that a comprehensive system, such as a CDSS, is necessary to improve the identification of potential DDIs (157). In our study, like the studies of Cox et al. (158) and Mahoney et al. (159), there were improvements in medication dosing and monitoring.

In regards to the effectiveness of CDSS in clinical practice and patient outcomes, studies have shown CDSSs are effective in changing the care processes and can improve performance (e.g., right drug dosing, appropriate prescribing of medication). However, few studies have demonstrated that CDSSs can improve patient outcomes (33, 160, 161). The results of some studies about improving patient outcomes are still unclear (162, 163). Moreover, Main et al. study indicated that the implementation of CDSS is time-consuming, complex and costly (164).

This study carefully evaluated critical factors that affect the implementation of CDSS from multiple perspectives. Different studies have also pointed to various factors. Participation and involvement of physicians in the process of CDSS development, from the beginning, play a significant role in accepting the usefulness of that system (165, 166). Our research results, like Varonen’s study, showed that having a positive view about the simple use of CDSS and understanding the benefits of patient outcomes as well as the usefulness of CDSS will cause physicians to use the system more, and vice versa, a negative view of doctors about CDSS is a barrier to focusing on the patient, or clinical work (167).

We found that one of the main obstacles to the implementation of CDSS was the threat of physician-patient communication, which was related to the physician's computer skills.

One study found that when physicians pay attention to the computer, patients' emotions are ignored. Patients believed that, if doctors maintain eye contact with them, the use of computer systems does not disturb their communication (168). The results of Trivedi et al.'s study showed that training doctors before the implementation of CDSS is one of the most important and effective strategies for optimal use of CDSS (169). Furthermore, to ensure a better transition period, organizations should emphasize education and training programs at the pre-implementation stage (170-172). In addition, they must familiarize people with the capabilities of the system and software before the actual implementation of the system. They should also change the attitude of personnel towards the tool. The relevance of educational and training programs about computer skills, physicians’ pattern of use, and availability of on-site information technology, and the provision of individual support for doctors can also be significant strategies (168, 169, 173). Moreover, proper training for the end-users and peer-to-peer training has been shown to have a positive impact on CDSS implementation (174).

Several studies showed that automated CDSS should provide advice at the right time and at the point of care for decision making (34, 35, 44); while Berlin et al. found that only in 41% of cases (175). The results of some studies showed that some doctors prefer to see recommendations before the patient's visit or at the end of their working day. This difference can be justified by changing clinical practices and workflows. Therefore, the timing of the CDSS recommendations should be consistent with the doctor's workflow (165, 176). With the direct support of IT, physicians can respond quickly when they encounter problems with the use of the system. The policies and incentives, engagement of key personnel, adequate infrastructure and resources, organizational readiness, the coordination of innovations with workflows, and individuals’ knowledge, beliefs, as well as processes and systems, are important factors that should be considered in the implementation of the system in the healthcare settings (177).

Studies showed that users are looking for a system that is both functional and responsive to their professional needs. In these studies, users indicated that factors such as design and technical support, interoperability, appropriate content, productivity, and resources are important and should be considered (172, 178-181). The system should also be implemented in such a way that it facilitates the exchange of information between organizations (interoperability) (182, 183). Davis (184) refers to Technology Acceptance Model and states that the most common factors in accepting the use of information and communication technology by healthcare professionals include the system's usefulness (a clear understanding of the benefits of innovation) and ease of use, similar to the results of other studies (173, 185-187). Meanwhile, the engagement of leaders and key personnel also helps to understand the usefulness and user-friendliness of the system (186), although this result was not found in Marcy's study (188). Similar to the results of Gagnon et al.'s (117) study, Gravel (189) showed that time constraint is one of the most important obstacles to the adoption of ICT and shared decision-making implementation in clinical practice.

Ross et al. showed that inadequate coordination between ICT applications and clinical workflow is another factor that leads to the unsuccessful implementation of systems (116), and these findings are in line with the results of other studies (45, 190, 191). Other barriers to the implementation of systems that were stated by Reisman included the users’ failure to use CDSS or the rejection of system recommendations by experts (191). Issues related to characteristics of system-specific and organizational and personal issues affect the acceptance of new technologies by physicians (192).

Studies showed that systems that perform the task automatically have a better performance than those that the system's users initiate them, and this is consistent with Kawamoto and Lobach 's findings (36), but Hemens et al.’s study did not find this result (21). Adaptability and cost were two important factors that Lee et al. pointed out in e-health intervention (177).

Given the importance of preventing medication-related errors and safety issues, the use of CDSS systems is one of the main strategies for improving patient safety, practitioners’ performance, and the quality and efficiency of care. There is also a need for the development of decision support tools that are consistent with a clinicians’ workflow that is also customized, as they can have a positive effect on efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Strengths and limitations of the review

One of the most important features of this study was that there was no specific language restriction in this study (studies in other languages were omitted due to incompatibility with the aim of this study). We almost tried to examine more aspects of the medication rather than focusing on a particular aspect.

This study has some limitations. One of these limitations was that related studies such as the grey literature and conferences might have been lost and may be relevant papers have been excluded due to the search terms. However, there are valuable conferences that might be even more relevant to the implementation of CDSS than those in grey literature. A variety of internationally-appropriated keywords and MeSH headings were utilized within areas of the search; however, some relevant papers may have been overlooked.

Implications for further research

Based on the findings of our review, this study highlights future directions in this area of research. Healthcare organizations would be better to be familiar with the system, its capabilities, and its applications in order to make a valuable and extensive investment in this area. Also, system providers can help improve system performance by providing and designing user-friendly CDSS systems and knowledge-based tools to make the system use more effective. Educational programs before the implementation of the system for key users are other important factors that health care organizations should pay attention to. System integration into other systems such as CPOE, EHR, e-prescribing, and workflow and interoperability is also one of the key issues in the development of the system, which will be facilitated according to terminology and standards. Healthcare organizations can continue to encourage the use of this system by providing strong and appropriate infrastructure. However, more studies are needed to examine the effectiveness of CDSS on patient safety outcomes, to determine success factors in its implementation and also to investigate the effect of CDSSs on economic in clinical settings especially in the medication-related fields.

Conclusion

The results of this study show that, although computer systems such as CDSS may cause errors, in most cases, it has helped to improve prescribing, reduce side effects and drug interactions, and improve patient safety. Although these systems have improved the performance of practitioners and processes, there has not been much research on the impact of these systems on patient outcomes. Moreover, the factors such as the participation of key personnel in the process of development and implementation of the system, training, and monitoring of the system in the early stages of implementation, and the integration of the system with other systems, in particular CPOE, have been the most important factors influencing the success of CDSS implementation.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Cite this article as: Shahmoradi L, Safdari R, Ahmadi H, Zahmatkeshan M. Clinical decision support systems-based interventions to improve medication outcomes: A systematic literature review on features and effects. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021 (22 Feb);35:27. https://doi.org/10.47176/mjiri.35.27

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Funding:This work was supported by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (grant number 94-01-31-28873).

References

- 1.Bennett JW, Glasziou PP. Computerised reminders and feedback in medication management: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Med J Austral. 2003;178(5):217–22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marfo K. Evaluation of medication errors via a computerized physician order entry system in an inpatient renal transplant unit. 2011.

- 3.Nabovati E, Vakili-Arki H, Taherzadeh Z, Saberi MR, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A. et al. Information Technology-Based Interventions to Improve Drug-Drug Interaction Outcomes: A Systematic Review on Features and Effects. J Med Syst. 2017;41(1):12. doi: 10.1007/s10916-016-0649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donaldson MS, Corrigan JM, Kohn LT. To err is human: building a safer health system: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed]

- 5.Kazemi A, Ellenius J, Pourasghar F, Tofighi S, Salehi A, Amanati A. et al. The effect of computerized physician order entry and decision support system on medication errors in the neonatal ward: experiences from an Iranian teaching hospital. J Med Syst. 2011;35(1):25–37. doi: 10.1007/s10916-009-9338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sintchenko V, Coiera E, Gilbert GL. Decision support systems for antibiotic prescribing. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21(6):573–9. doi: 10.1097/qco.0b013e3283118932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein MK, Hoffman BB, Coleman RW, Tu SW, Shankar RD, O'Connor M. et al. Patient safety in guideline-based decision support for hypertension management: ATHENA DSS. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(Supplement_6):S11–S6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yazdani A, Ghazisaeedi M, Ahmadinejad N, Giti M, Amjadi H, Nahvijou A. Automated Misspelling Detection and Correction in Persian Clinical Text. J Digit Imaging. 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10278-019-00296-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bennett JW, Glasziou PP. Computerised reminders and feedback in medication management: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Med J Aust. 2003;178(5):217–+. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forni A, Chu HT, Fanikos J. Technology utilization to prevent medication errors. Curr Drug Saf. 2010;5(1):13–8. doi: 10.2174/157488610789869193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Chae YM, Kim S, Ho SH, Kim HH, Park CB. A study on user satisfaction regarding the clinical decision support system (CDSS) for medication. J Healthc Inform Res. 2012;18(1):35–43. doi: 10.4258/hir.2012.18.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y, Bae M, Park J, Choi C, Bae S, Chae Y. Evaluation of the effects of the CDSS for drug prescription for hospitals. J Korea Soc Health Infor Stat. 2007;32(2):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nabovati E, Vakili-Arki H, Taherzadeh Z, Saberi MR, Medlock S, Abu-Hanna A. et al. Information Technology-Based Interventions to Improve Drug-Drug Interaction Outcomes: A Systematic Review on Features and Effects. J Med Syst. 2017;41(1):12. doi: 10.1007/s10916-016-0649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sintchenko V, Magrabi F, Tipper S. Are we measuring the right end-points? Variables that affect the impact of computerised decision support on patient outcomes: a systematic review. Med Inform Int Med. 2007;32(3):225–40. doi: 10.1080/14639230701447701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazdani A, Safdari R, Ghazisaeedi M, Beigy H, Sharifian R. Scalable architecture for telemonitoring chronic diseases in order to support the CDSSs in a common platform. Acta Inform Med. 2018;26(3):195. doi: 10.5455/aim.2018.26.195-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berner ES. Clinical decision support systems: Springer; 2007.

- 17.Akçura MT, Ozdemir ZD. Drug prescription behavior and decision support systems. Decis Support Syst. 2014;57:395–405. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, Smith K. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Jama. 1998;280(15):1339–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein MK, Hoffman BB, Coleman RW, Tu SW, Shankar RD, O'Connor M. et al. Patient safety in guideline-based decision support for hypertension management: ATHENA DSS. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2002;9(Supplement 6):S11–S6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carling CLL, Kirkehei I, Dalsbo TK, Paulsen E. Risks to patient safety associated with implementation of electronic applications for medication management in ambulatory care - a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemens BJ, Holbrook A, Tonkin M, Mackay JA, Weise-Kelly L, Navarro T. et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for drug prescribing and management: A decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaghoubi Ashrafi M, Karami M, Safdari R, Nazeri A. Selective overview on decision support systems: Focus on HealthCare. Life Sci J. 2013;10(SPL.ISSUE10):348–55. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yourman L, Concato J, Agostini JV. Use of computer decision support interventions to improve medication prescribing in older adults: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2008;6(2):119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfstadt JI, Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Lee M, Kalkar S, Wu W. et al. The effect of computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support on the rates of adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):451–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0504-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieuwlaat R, Connolly SJ, Mackay JA, Weise-Kelly L, Navarro T, Wilczynski NL. et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for therapeutic drug monitoring and dosing: A decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahota N, Lloyd R, Ramakrishna A, Mackay JA, Prorok JC, Weise-Kelly L. et al. Computerized clinical decision support systems for acute care management: A decision-maker-researcher partnership systematic review of effects on process of care and patient outcomes. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinke ML, Bundy DG, Velasquez CA, Rao S, Zerhouni Y, Lobner K. et al. Interventions to reduce pediatric medication errors: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):338–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lainer M, Mann E, Sonnichsen A. Information technology interventions to improve medication safety in primary care: a systematic review. International journal for quality in health care : Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(5):590–8. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia P, Zhang L, Chen J, Zhao P, Zhang M. The effects of clinical decision support systems on medication safety: An overview. PloS one. 2016;11(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaushal R, Shojania KG, Bates DW. Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety - A systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(12):1409–16. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.12.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson S-A, Moxey A, Robertson J, Hains I, Williamson M, Reeve J. et al. Do computerised clinical decision support systems for prescribing change practice? A systematic review of the literature (1990-2007) BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):154. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baysari MT, Lehnbom EC, Li L, Hargreaves A, Day RO, Westbrook JI. The effectiveness of information technology to improve antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Med Inf. 2016;92:15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux P, Beyene J. et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. Jama. 2005;293(10):1223–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huff S, McClurec R, Parkerc C, Rochac R, Abarbaneld R, Beardd N. et al. Modeling guidelines for integration into clinical workflow. Medinfo. 2004:174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. Bmj. 2005;330(7494):765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38398.500764.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawamoto K, Lobach DF. Clinical decision support provided within physician order entry systems: a systematic review of features effective for changing clinician behavior. AMIA Ann Symp Proc. 2003:361–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilsdonk E, Peute LW, Jaspers MWM. Factors influencing implementation success of guideline-based clinical decision support systems: A systematic review and gaps analysis. Int J Med Inf. 2017;98:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilsdonk E, Peute LW, Knijnenburg SL, Jaspers MW. Factors known to influence acceptance of clinical decision support systems. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2011;169:150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luftman J. Assessing business-IT alignment maturity. Strategies for information technology governance. 2004;4:99. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mollon B, Chong J, Jr Jr. , Holbrook AM, Sung M, Thabane L, Foster G Features predicting the success of computerized decision support for prescribing: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moxey A, Robertson J, Newby D, Hains I, Williamson M, Pearson S-A. Computerized clinical decision support for prescribing: provision does not guarantee uptake. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(1):25–33. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Randell R, Dowding D. Organisational influences on nurses’ use of clinical decision support systems. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(6):412–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roshanov PS, Fernandes N, Wilczynski JM, Hemens BJ, You JJ, Handler SM. et al. Features of effective computerised clinical decision support systems: Meta-regression of 162 randomised trials. BMJ (Online) 2013;346(7899) doi: 10.1136/bmj.f657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saleem JJ, Patterson ES, Militello L, Render ML, Orshansky G, Asch SM. Exploring barriers and facilitators to the use of computerized clinical reminders. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(4):438–47. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yusof MM, Kuljis J, Papazafeiropoulou A, Stergioulas LK. An evaluation framework for Health Information Systems: human, organization and technology-fit factors (HOT-fit) Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(6):386–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tawadrous D, Shariff SZ, Haynes RB, Iansavichus AV, Jain AK, Garg AX. Use of clinical decision support systems for kidney-related drug prescribing: a systematic review American journal of kidney diseases : the official. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(6):903–14. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robertson J, Walkom E, Pearson SA, Hains I, Williamsone M, Newby D. The impact of pharmacy computerised clinical decision support on prescribing, clinical and patient outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18(2):69–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearson SA, Moxey A, Robertson J, Hains I, Williamson M, Reeve J. et al. Do computerised clinical decision support systems for prescribing change practice? A systematic review of the literature (1990-2007) BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:154. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iankowitz N, Dowden M, Palomino S, Uzokwe H, Worral P. The effectiveness of computer system tools on potentially inappropriate medications ordered at discharge for adults older than 65 years of age: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10(13):798–831. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2012-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holstiege J, Mathes T, Pieper D. Effects of computer-aided clinical decision support systems in improving antibiotic prescribing by primary care providers: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc: JAMIA. 2015;22(1):236–42. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Bahar F, Marriott J, Curtis C, Dhillon H. The effects of computer-aided clinical decision support systems on antibiotic prescribing in secondary care: A systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015;23:24. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, Phansalkar S, Stanton W, Bates DW. et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians' prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc: JAMIA. 2009;16(4):531–8. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reckmann MH, Westbrook JI, Koh Y, Lo C, Day RO. Does Computerized Provider Order Entry Reduce Prescribing Errors for Hospital Inpatients? A Systematic Review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):613–23. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S, de Rooij SE, Verheij R, Korevaar JC. et al. Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: a systematic review. PloS one. 2012;7(8):e43617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mitchell E, Sullivan F. A descriptive feast but an evaluative famine: systematic review of published articles on primary care computing during 1980-97. Br Med J. 2001;322(7281):279–82E. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loganathan M, Singh S, Franklin BD, Bottle A, Majeed A. Interventions to optimise prescribing in care homes: systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40(2):150–62. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Delpierre C, Cuzin L, Fillaux J, Alvarez M, Massip P, Lang T. A systematic review of computer-based patient record systems and quality of care: more randomized clinical trials or a broader approach? International journal for quality in health care : Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16(5):407–16. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Rosse F, Maat B, Rademaker CMA, van Vught AJ, Egberts ACG, Bollen CW. The Effect of Computerized Physician Order Entry on Medication Prescription Errors and Clinical Outcome in Pediatric and Intensive Care: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):1184–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay C, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Effect of point-of-care computer reminders on physician behaviour: a systematic review. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182(5):E216–E25. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prgomet M, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI. The Impact of Mobile Handheld Technology on Hospital Physicians' Work Practices and Patient Care: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Inform Assoc: JAMIA. 2009;16(6):792–801. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grindrod KA, Patel P, Martin JE. What interventions should pharmacists employ to impact health practitioners' prescribing practices? Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(9):1546–57. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Black AD, Car J, Pagliari C, Anandan C, Cresswell K, Bokun T. et al. The impact of eHealth on the quality and safety of health care: a systematic overview. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]