Abstract

Background: Over the years, cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) has gained momentum because of its robust evidence in the treatment of several disorders. However, there is an issue of religious and cultural appropriateness as CBT principles are based on Western conceptualization. This single‐case study (N = 1) implements a culturally and religiously adapted CBT on a 34‐year‐old male with panic disorder with agoraphobia in Malaysia. The client had symptoms comprising various episodes of sudden onset of breathlessness, accelerated heart rate, and fear of dying for the last 14 years. The CBT was culturally and religiously adapted based on (1) A CBT manual in Bahasa Malaysia that was previously modified and adjusted according to the norms of the Malaysian society and (2) General guidelines in "Religious–Cultural Psychotherapy in the Management of Anxiety Patients" by Razali et al in 2002. The present modified CBT had 3 assessments formulation sessions and 12 intervention sessions.

Methods: The first 6 sessions were based on the behaviour component of CBT (ie, a relaxation technique using Islamic prayer, reciting verses from the Holy Quran, slow breathing exercise, body scan, and progressive muscular relaxation). However, sessions 7 to 12 were focused on cognitive restructuring and exercises, such as identification of negative automatic thoughts, cognitive distortions, dysfunctional thought records, vertical arrow technique, and the coping statement was practised through collaborative empiricism, while implementing Islamic and cultural elements. The focus of termination sessions was on interoceptive exposure, cognitive rehearsal, and in vivo situational exposure.

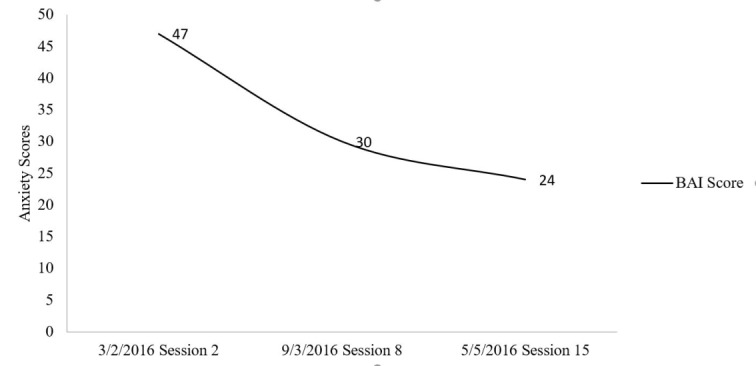

Results: Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was administered at regular intervals. BAI scores revealed the effectiveness of adapting the intervention.

Conclusion: Panic attacks, worry about panic attacks, and anxiety scores reduced remarkably and the client was able to go out of the house, travel independently, and pursue religious/social activities.

Keywords: Psychotherapy, Religion, Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, Culturally Adapted Treatment

↑ What is “already known” in this topic:

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), highly effective in the treatment of panic disorder, has shown robust empirical evidence in numerous patient populations. The Ministry of Health of Malaysia recommends offering CBT with pharmacological treatments to treat bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Malays in Malaysia have difficulty associating cognition, mood, and behaviour with depression or anxiety. Hence, introducing cultural modifications in CBT would resonate in this population’s value system. Past research has demonstrated an increased effectiveness of modifying CBT according to a given population’s cultural values, especially Islamic beliefs.

→ What this article adds:

This study showed that the implementation of culturally and religiously adapted CBT brought substantial reductions in symptomatology. The symptoms were assessed through panic attack progress records demonstrating weekly frequency and percentages of panic attacks, anxiety levels, and worry about panic attacks. Additionally, Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) showed that the client’s anxiety levels at pre-, mid-, and post-assessment were also significantly reduced.

Introduction

The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) with numerous patient populations and problems has been supported through the past empirical evidence (1-3). CBT is a highly effective treatment for panic disorder (4-9). Because of the perceived utility of CBT in clinical settings, its importance is predicted to increase in the future (10, 11).

The history of cognitive therapy in Malaysia dates back to the early 1990s when Prof. Azhar Md. Zain, the first UK-trained Malaysian cognitive behaviour therapist, started educating the Malaysian mental health professionals about the principles of CBT using workshops (12). Considering the wide applications of CBT in Malaysia (13), the Ministry of Health of Malaysia (MOH) recommended offering CBT with pharmacological treatments to treat bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (14, 15). Malaysia is a southeast Asian country having its own heritage, culture, and values (16). Bahasa Malaysia is the national language in Malaysia (17). Islam is the official religion of Malaysia, a legally presumed faith of all ethnic Malays-one of the ethnic groups in Malaysia, while other religions are practised in peace and harmony (18). Islam provides followers with a distinct value system (19). Therefore, to be effective with Muslims, practitioners must use therapeutic strategies that are consistent with religious and cultural values (20). This is due to the various issues, which can have an influence on the application of CBT in non-Western cultures (21-24). In the treatment of anxiety and depression, religiously integrated CBT based on clients’ practices and beliefs have been documented to be as effective as conventional CBT (25). Religion has been known to help clients cope effectively via prayer when dealing with illness, disability, and negative life events (26). Like other culturally unique populations, modifying Western therapeutic strategies can increase their effectiveness with Muslims (27).

A systemic review of treatments for anxiety disorders (ADs) in Malaysia concluded that studies integrating religious-sociocultural psychotherapy or religious-cultural psychotherapy with benzodiazepines (BDZ) were effective compared to studies involving supportive psychotherapy with BDZ only (28). The authors emphasised the importance of religious-cultural elements during psychotherapy for patients with ADs in Malaysia (28). Likewise, an earlier study showed that, compared to standard treatment alone, the incorporation of religion and sociocultural elements in psychotherapy by therapist brought quicker achievement of treatments outcomes among Malays with anxiety and depression (29). In the same way, another study demonstrated that Malay Muslim patients improved as they were encouraged to link and identify negative thoughts with Islamic teaching and culture using the Holy Quran and Hadith as well as emulating healthy lifestyle as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) (30).

Past research has demonstrated that Malays have distinct culture, as they are reserved in expressing psychological problems and display characteristics of loyalty and obedience (13, 31, 32). The Malays are shown to have a specific set of psychopathologies, culture, values and belief system with a strong religious background (13, 29). Local studies have shown Malays to be more culturally and religiously orientated than psychologically minded; hence, the Western concepts of psychotherapy would have effectiveness (29). The Malays are shown to struggle with Western psychotherapy concerning perceiving the correlation between emotional disturbances and psychosocial stress (29). Owing to this reservation, the Malays have been shown to not to associate their feelings with thoughts (13). Mukhtar and colleagues (2011) showed that Malays rarely discussed the idea of an association of cognition, mood, and behaviour associated with depression or anxiety. Hence, it appeared imperative to introduce cultural modifications in CBT to make CBT resonate with this population’s value system (33-35). Past research has demonstrated an increased effectiveness of modifying CBT according to a given population’s cultural values (33, 36), especially Islamic beliefs (37, 38). With the increase in cultural diversity in Western societies, a modification in therapeutic procedures, a vital precondition for effective service provision to make them consistent with clients’ value systems, is encouraged (39, 40).

CBT seems to be one of the most commonly used models for adapting to religious orientations (41-43). There are a few research studies that have adapted the CBT concept to suit the client’s spiritual, religious, and cultural background (11, 37, 44-49); for instance, incorporating Taoism into CBT for the neurosis treatment (50), using CBT with Christian beliefs to treat depression (51), culturally adapted CBT for psychosis and depression (52, 53), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (54).

Additionally, the effectiveness of Islamically modified CBT was assessed in 5 studies conducted in Malaysia. For instance, Azhar & Varma (1995) found that devout Muslims suffering from depression or grief and bereavement showed improvement on top of acceptability of the practice and better compliance with Islamic religious psychotherapy as compared to the conventional or Western concept of psychotherapy (55, 56). Likewise, other studies showed similar findings with clients wrestling with anxiety disorders (57, 58) and depression (59). A past study in Malaysia proposed Islamic integrated cognitive behavioural therapy (IICBT), which assimilated Muslim patients’ faith and practices based on the Quran and Hadith (60). The present study presents a successful application of culturally and religiously modified CBT to the treatment of a Malay Muslim male diagnosed with Panic Disorder with agoraphobia.

Description of the Client

This single‐case study (N = 1) implements a culturally and religiously adapted CBT on a 34‐year‐old male with panic disorder and agoraphobia in Malaysia. Danny is a single 34-year-old Malay Muslim male, with symptoms consisting of multiple episodes of sudden onset of breathlessness, increased heart rate, and fear of dying for the last 14 years. Danny was referred by his treating psychiatrist for CBT. Although he was on oral medication (ie, sertraline tablet 150 mg once a day), the psychiatrist believed that he could benefit from CBT as he only showed mild improvements through medication.

Danny had estranged relations with his father and until his late teens, he did not know his father. His father (American citizen of Caucasian descent) returned to the US when Danny was only 3 years old. Due to a major vehicle accident, serious injuries and coma, Danny’s father remained out of contact with his mother, which caused a breakdown in his parents’ marriage, leading to Danny’s mother requesting his father for a divorce (fasakh) under the Malaysian Syariah law. Danny met his father at the age of 17 when he came to Malaysia to transfer his properties in the US to Danny, as he was the only male legal heir. Danny had estranged relations with his mother and never felt emotional attachment with her as she was mostly out of the house. She was described as a conservative, old-fashioned Malay lady who came from the Kelantan- a state in the East Coast of Malaysia.

Danny’s mother remarried a policeman when he was 9 years old. With time, the stepfather became strict, bossy, and short-tempered, and started physically (eg, locking him in the washroom for hours without food or water, or tying him in a gunny sack) and verbally abusing (eg, shouting and cursing) Danny, especially when his mother was not around. As a result, he remained afraid of the stepfather. The stepfather mocked Danny by saying that his biological father abandoned him as he did not love him. He could vividly recall his screams, cries, suffocation, and begging the stepfather to let him go. The abuse made him feel unloved, unwanted, and negatively influenced his self-esteem. Danny’s mother considered this abuse a punishment for his naughty behavior. Danny started to believe that his mother also did not love him as compared to his half-siblings and stepfather.

The stepfather’s quitting of the job from the police department 2 years after marriage, gambling, and loan sharks ended this marriage. Before divorce could be granted, his stepfather died, which brought relief and comfort for Danny. However, loan sharks started chasing Danny and his family to repay his late stepfather’s debt. Once, Danny was held at knifepoint by the loan shark for the repayment and was freed until his mother gave them some money. By the age of 22, he was juggling between his studies and a part-time job, which he took due to financial constraints. He remained worried due to inability to simultaneously manage the job and education. Due to working overtime, he often slept for 1 to 2 hours.

The first episode of panic attack occurred when he went to a supermarket to look for his half-sister and felt suffocated and dizzy. He felt pounding heart, chest discomfort, shortness of breath, nauseous, sweating, trembling, and shaking. He tried to run but felt heaviness and numbness in his limbs. He described it as akin to a heart attack. Right outside the mall, he tripped and fainted. Later his sister found him, with all his belongings stolen. He was immediately taken to the emergency department of a nearby hospital, admitted for a day, and discharged. He took 2 weeks off from college to relax, however, a similar episode of panic attack happened while he was caught in traffic congestion. Due to the fear of losing control and dying, he accidentally freed his car’s handbrake and hit the car behind him. Fortunately, both he and the other driver were not harmed. Both times, the attack peaked within minutes and each episode lasted about 5 to 10 minutes. Since then, he always felt on the edge and was more relaxed at home.

He remained persistently worried about having another attack, losing control, or having a heart attack. Due to a strong family history of heart disease on both sides of his biological parents, he also believed that he had heart issues. Whenever he had a panic attack, he would isolate himself, hug something comfortable like his pillows, shut his eyes tightly, lean against the wall, or lie on the floor and perform his Muslim prayers to alleviate his attack. He feared that if the symptoms recurred or if he had a heart attack and was dying, he would not be able to escape, and no one would help him. Gradually, he avoided closed areas or spaces (eg, being alone in an elevator, shopping malls, or other crowded places), refused to drive due to the fear of getting stuck in traffic, or tried to persuade someone else to accompany him to the mall. Because of his inability to stand in a queue, take a bus, or other public transport, he dropped out of college, quit his job, lost contact with friends, and stayed at home. He refused to go out, however, to earn money, he learnt web designing from an online course and launched his own online web designing company. He managed and earned from this new job while staying at home. He was diagnosed by a general practitioner with hypertension and prescribed Amlodipine 10 mg once a day, however, the results of his other routine blood investigations and multiple ECGs were always normal. Danny sought traditional treatment for his symptoms upon the advice of his mother as she attributed Danny’s symptoms to evil spirits and believed in the Dark Arts. Malays from Kelantan are generally more religious compared to the well-developed state of the West Coast. Malays from the East coast differ in stigmatizing mental health issues and attribute such issues to supernatural agents, witchcraft, and possession by an evil spirit (29). These patients are more willing to see the locally accepted traditional healers who integrate religious and cultural aspects in their treatments (29). However, in Danny’s case, there were no improvements in his symptoms despite going to the traditional healers. He denied any other symptoms of anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, psychosis, or thyroid issues. Danny has never had any seizures, fever, or any other debilitating infection for the last 14 years. He denied a history of taking excessive amounts of caffeine or carbonated drinks every day, as he only consumed 1 or 2 cups of coffee every day. He denied any history of consuming illicit substances, alcohol, or smoking.

Assessment

Before enrolment in CBT, diagnostic status was assessed using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; 61), Mental State Examination (MSE), clinical interview, and physical examinations. Additionally, panic attack progress records were administered each week to track the client’s levels of anxiety and worry about panic as well as the number of panic attacks. Danny’s score on BAI was 47, indicating severe anxiety despite taking medicines. He had negative automatic thoughts (NATs) and frequently ruminated about his problems. Results of MSE indicated that Danny’s mood was euthymic and affect was congruent to his thoughts. Upon discussing abuse by his stepfather, his demeanor changed, he became nervous and distressed, sat at the edge of his seat, and started fidgeting with his bag. Additionally, to consciously hide his fidgeting, he would hide his hands in his slack pockets or fidget with his fingers. Overall, he was forthcoming, cooperative, and attentive to the conversation throughout the interview. Although he was a native Bahasa Malaysia speaker, his command of English was equally good. He denied any perceptual disturbances nor were there any disorders of thought. Danny’s cognitive assessment was intact with good abstract thinking and all aspects of judgement were good. His insight was good – he had good emotional insight. He was aware that he was not well and needed help. He attributed his problem to his childhood experiences and admitted that he had poor coping skills to handle stress. He was willing to get treatment, motivated to improve himself, and expand his business. Furthermore, his reports of physical examination (ie, full blood count, renal profile test, liver function test, fasting lipid profile, fasting blood sugar, thyroid function test, and electrocardiogram) revealed no general medical condition.

Case Conceptualization

Studies have shown that Asians, particularly Malaysians of Malay and Chinese ethnicity, would rather interpret psychological problems in physical or somatic terms (62). Malays project their psychological problems as physical symptoms to avoid shame and stigma from being diagnosed with a mental illness, as physical symptoms are more acceptable (62). Catastrophic cognition in anxiety disorder depends on the local ideas about the psychological and physiological significance of arousal symptoms (62). In the present case, Danny viewed his panic attacks as a recurrent heart attack due to the genetic predisposition of heart issues on both his father’s and mother’s side. The distressing feelings related to shortness of breath and choking further reinforced his catastrophic cognitions about anxiety (62).

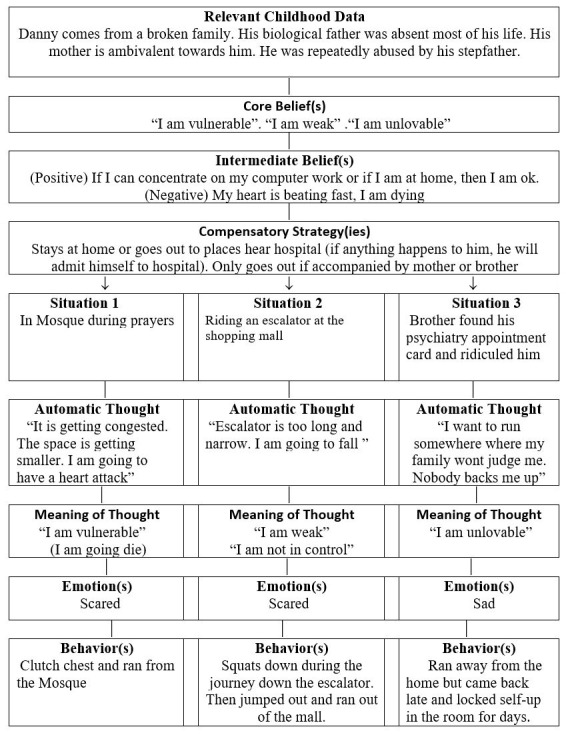

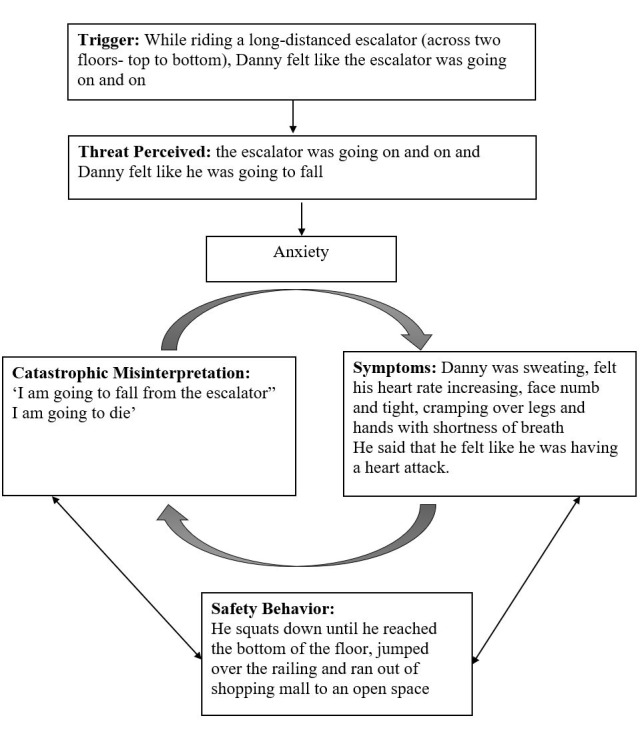

From the earliest stages of therapy, a shared conceptualization of the problems was designed with Danny, and self-monitoring of panic attacks between sessions was used to identify those key components of the attacks. Recent episodes of panic were reviewed to highlight key variables, and he completed the weekly self-report charts. Through a process of guided discovery, he was able to identify how the thoughts, feelings, and behaviours in these situations interacted and reinforced one another. A cognitive conceptualization diagram (Fig. 1) illustrates some of the typical symptoms, compensatory strategies, automatic thoughts, and behaviours that characterized his panic attacks (63). Additionally, a cognitive model of a panic attack (Fig. 2) was also used to develop a thorough understanding of different episodes of panic attacks (64).

Fig. 1.

Cognitive conceptualization diagram. Adapted from cognitive behaviour therapy worksheet packet. Copyright 2011 by Judith S. Beck. Bala Cynwyd, PA: Beck Institute for cognitive behaviour therapy (Beck & Beck, 2011).

Fig. 2.

A cognitive model of a panic attack. Adapted from “A cognitive approach to panic,” by D. M. Clark, 1986, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 4(24) 461–470. Copyright 2020 by the American Psychological Association.

Treatment

Danny was offered 15 sessions of CBT. Each session was approximately 60 minutes and conducted every week for 15 weeks (Table 1). The CBT therapy sessions were arranged based on the 2 CBT anxiety/panic disorder program workbooks (65, 66). Mukhtar and Oei (2011) modified and adjusted the workbooks according to the norms of Malaysian society (67). The Bahasa Malaysia Manual was administered on Danny. General guidelines of religion-cultural psychotherapy were adapted and modified according to the client based on Razali et al (2002)’s paper (29, 58). Not all of the guidelines were implemented. The therapist was a non-Muslim who was supervised by a senior Muslim clinical psychologist. Razali et al highlighted that implementing religious psychotherapy helps clients revive their spiritual strength to cope with an anxiety disorder (29, 58).

Table 1. Structure of therapy sessions.

| Sessions | Focus |

| Session 1 to 6 | Initiation of CBT |

| Session 7 to 12 | Mid sessions |

| Session 13 to 15 | Termination of CBT |

BAI was administered before starting CBT, at the eighth session and at the termination of CBT (ie, session 15).

Initiation of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

From Session 1 to session 6, the emphasis was on the behaviour part of CBT. Danny was taught the aetiology of the illness and theories behind panic disorder using handouts from the Malaysian CBT/anxiety disorder program workbook that was culturally sensitive to the Malaysian culture (66, 68) and tools from an online therapy resource website (Evidence-based CBT worksheets, https://www.psychologytools.com/download-therapy-worksheets/) which are user-friendly and highly informative. Each week began with recording panic attack progress to assess his progress. At first, each session was crammed to one day, however, later the sessions were broken up: aiming for 1 or 2 goals each session. During the subsequent therapy sessions, the client felt better and was able to cope with sessions. This was evident in his panic attack records over the weeks. However, during session 4, he admitted having a major setback. After session 3, he felt getting ‘better’ and decided to go to a shopping mall, which was on his way home. While on a long escalator, he experienced a panic attack and ran out of the shopping mall. On re-evaluation of the sessions, the therapist realised Danny’s eagerness to please the therapist, and his ‘rush’ to get better. Danny also admitted the need to get well fast as he had been unwell for many years and was missing out a lot in his life. However, he was reminded to be patient with the therapy.

In the next session, Danny was taught slow breathing exercise. After a few practice sessions with the therapist, he was encouraged to practice and maintain a journal of his breathing practices at home as part of his homework. Danny could practice his slow breathing exercise after his Fajr and Isha’a (early morning and evening) prayers for 3 to 5 minutes. He found it easier to schedule his practice after his Fajr and Isha’a (early morning and evening) prayers and diligently did his homework. Danny was also encouraged to pray 5 times a day regularly following the second Pillar of Islam, a form of meditation, which encourages a sense of being and promotes relaxation. Through daily prayers, Danny reported cultivating a good spiritual relationship with God as well as ability to rely on Him in times of anxiety. The psychological changes through prayers have shown to be effective for overtly tense clients (29, 55-57). To help with his spirituality, he was encouraged to read verses of the Holy Quran and zikr (commemoration of Allah’s name) after his prayers (29). In later sessions, he was taught the body scan, which he liked doing because he was finally able to target the areas that he felt had the highest muscle tension and later progressed to doing the progressive muscular relaxation. All his homework was well-written and commended. During the session, he finally realized that there was no need to rush ‘to get better’ and he came to accept the slow-paced recovery. Danny was advised to adopt a healthy lifestyle and live by his Islamic values (ie, to follow the customs of Prophet Muhammad PBUH) (29).

During the sixth session, a review of all the previous sessions was carried out to refresh the client’s memory. This was done to see whether he had understood the fundamental aspects of panic disorder and check on his relaxation techniques. The therapist found this session useful as Danny had a lot of questions regarding the panic disorder and tended to talk a lot about his past. The therapist had to gently remind him that the therapy was for ‘now’. The therapist encouraged the client to be kind to himself and be proud that he was progressing gradually.

Midway Through CBT

From session 7 to session 12, the therapist educated Danny about cognitive therapy (ie, a cognitive component of CBT). Danny was educated on the core message of CBT ‘change the way you feel by changing the way you think.’ The aim was to teach Danny not to indulge in catastrophizing and to distinguish his thoughts from his feelings using a handout from psychology tools, which helped him identify the negative automatic thoughts (NAT). He was also taught cognitive distortions - characteristic thinking styles associated with emotional disturbances. Danny was taught that faulty information processing and biased thinking affected his perception, lead to inaccurate decision-making, biased actions and emotions. With this information, he was educated that some of the cognitive distortions worsened his panic attack.

During session 8, the BAI was administered, which showed improvement in Danny’s scores from 47 to 30. Although the scores were in the category of severe anxiety, symptoms of Danny improved. Most of the symptoms were either mild or moderate (during the first BAI he had some severe symptoms). The next 2 sessions focused on completing the dysfunctional thought records (DTR) - one of the essential tools in CBT. In DTR, together with cognitive bias, patients are encouraged to identify NATs to see if their characteristic cognitive styles are distorted. Through these exercises, the client finally acknowledged that negative thinking could increase anxiety which expressed itself through physical symptoms and eventually impacted performance (ie, especially anxiety-provoking tasks).

He realised that realistic and rational thinking reduced panic disorder, kept the physical symptoms at par, and managed his anxiety. Danny recognized that his negative/distorted thoughts caused incorrect anxiety-provoking predictions and made him treat them as beliefs rather than facts. He was taught to challenge such thoughts by questioning if they were accurate, helpful, and necessary. Through all these exercises, his negative thoughts could be replaced with realistic and positive/realistic ones, which substantially managed his anxiety. Furthermore, the vertical arrow technique was taught and practised, which was a practical, simple, and effective skill to identify the core of his negative thoughts and unhealthy beliefs about himself. Danny was asked to identify a situation that provoked his negative emotions. To uncover NATs, Danny was asked, ‘What this situation says about you, others and/or the world around you?’ The aim was to keep asking the same question until he came to an absolute or conclusive statement (ie, core belief). In Danny’s case, at first, it was difficult to identify the thoughts, but after a few tries, his core beliefs were identified. His core beliefs were ‘I am vulnerable’, ‘I am weak’, and ‘I am unlovable’. Here, the therapist avoided preaching or going against Danny’s view. This identification of core beliefs was attained collaboratively by the therapist and the client (29). Accepting his views and interpretation of his symptoms strengthened the therapeutic alliance.

During the session, Danny was taught a mutually formulated coping statement ‘I don’t like it, but it’s ok, I can cope with it’. With that coping statement, he understood that even if things were out of his control, he was still able to cope with himself and be ‘ok’. At the end of session 12, Danny was more receptive and was able to participate and complete the DTR with ease. He finally understood that his panic attacks were not dangerous. That term seemed important to him because he underlined the sentence multiple times. Overall, the client and therapist were pleased with the progress and there was a breakthrough in improvements to his symptoms.

Termination of CBT

Danny was taught the interoceptive exposure exercise, cognitive rehearsal and the in vivo situational exposure during sessions 13 and 14. The aim of the interoceptive exposure was to correct the catastrophic interpretation of physical symptoms experienced by him as part of anticipatory anxiety or panic attack (69). This exercise, a stepwise experience, was provided to the client so that he could become comfortable with his physical sensations. By intentional provocation of symptoms using physical exercises, the client became comfortable with these sensations, which then allowed him to identify automatic thoughts and catastrophic interpretations associated with physical sensations and restructure them. The scenarios were first practised during the sessions, and then the client was asked to continue practising at home and document his experience in a chart prepared by the therapist. This technique helped him to improve his ability to manage his anxiety associated with stressful situations.

During the cognitive rehearsal part, Danny was taught to visualize an impending situation that he found stressful. He pictured himself dealing with the unpleasant situation and imagined himself successfully overcoming these problems. This rehearsal was repeated several times until he was comfortable with the scenario. This technique helped in reducing the apprehension associated with the anticipated stressful event because the client focused on dealing with it positively rather than being concerned that it could go wrong.

As part of his spiritual growth, throughout the sessions, Danny was educated on the ‘lifeline’ which were as follows:

Do not bring the past into the future. Do not allow memories to punish you now.

Do not bring the future back to the present. He was encouraged not to worry over things which he could not control.

Live your present now. Be kind to yourself.

Be grateful, focusing on the Islamic-based gratitude.

Danny was encouraged to be grateful to God, people, and his surroundings through gratitude exercises. He was encouraged to refer to the Holy Quran and the work and experiences of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) in the Holy Quran who showed the highest level of gratitude to God despite unimaginable sufferings (30).

As for the in vivo situational exposure, Danny was asked to practice a fear hierarchy and record the anxiety level and automatic thoughts that arouse in these situations. In vivo exposure is a technique used to overcome agoraphobic avoidance (69). This exposure was practised for the situations that were less anxiogenic to him and he showed a willingness to confront them. This technique is considered effective if exposure is prolonged in time (ie, remain in each situation for approximately twice if it takes to become comfortable in that situation). The anxiety level should be felt during the task, monitored by both the client and the therapist (69). Danny was encouraged to record this experience and apply the techniques learnt before practising this. As for the in vivo situational exposure, Danny admitted that although he was scared, he was willing to try it out in 2 situations: going on an escalator and going to the mosque. He later felt confident while facing the situations. In vivo situational exposure, Danny surprisingly performed 3 situational exposures. He documented the experiences and gave feedback regarding the situation. One of the situational exposures was related to mandatory Friday Islamic prayers in a mosque. Such exercises made him strong and he wanted to attend them regularly. The therapist gave positive feedback on the client’s improvements and a willingness to take chances.

Session 15

Throughout the sessions, Danny was informed about the risk of relapse upon completion of the therapy. Therefore, he needed to be consistent and continue practising what he had learnt. He was taught to be kind to himself and not blame himself in case he failed. Hence, this session was dedicated to helping him build and identify his support system and relapse prevention. The building of a support system was explained to Danny and its importance was emphasized. During this session, Danny came up with a support system that included work (He has an online web-designing business, which is also helping him out financially.), family (He has his younger half-brother who loves him and does not judge him.), religion (He considers himself a religious Muslim and believes in God,), extracurricular activities (He wants to join a society near his house to hang out with people of the same age.), and pets (He had a pet rabbit that he adored.). He was praised and commended for coming up with many support systems. During the session, he was asked to draw and colour his support system in a pictorial diagram (eg, drawing the soil, flower, and petals). He was happy with the picture and wanted to put it on his wall to see his amazing improvement.

As for relapse prevention, Danny was informed that after the sessions, he had to be prepared for high-risk situations and needed to incorporate what he had learnt before experiencing them. He was given a hypothetical situation where he could incorporate what he had learnt. He was praised on how he handled the situation. As for maintenance, he was told that improvements were gradual, and this was a slow-paced work. He was informed that he could not be perfect all the time and that failures are expected in this journey as failures are part and parcel of life. Most importantly, he needed to be consistent and practice whatever he had learnt.

He was taught to be aware of unrealistic expectations, accept the things that he could not change (eg, his family) and change the things he could (eg, himself). He had to be kind to himself, practice the relaxation techniques by incorporating Islamic religious practices, use behavioural strategies in the event of his panic attacks, and reduce his expectations by not being hard on himself. In case of a full-blown attack, he was advised to ask himself “what are the worst possible consequences?” and practice Socratic questioning. He was advised to keep in mind that there has been no evidence in the past that validated his NATs. He was also advised to maintain good physical and mental health through lifestyle change. During this session, BAI was administered as postassessment and he achieved a score of 24, mostly in the categories of ‘mild’ (16 symptoms), ‘moderate’ (4 symptoms) and ‘not at all’ (unable to relax), which is a huge improvement from his first preassessment when most of his symptoms were either severe or moderate.

Results

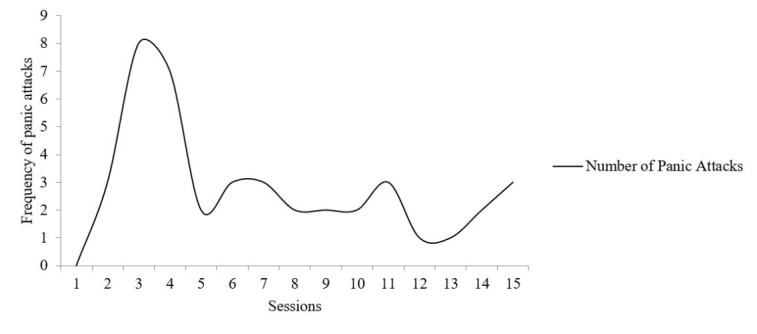

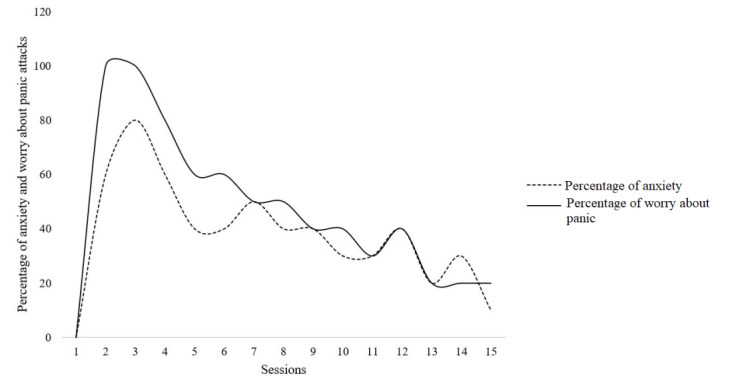

Figures 3 and 4 summarize the client’s panic attack progress records, demonstrating weekly frequency and percentages of panic attacks, anxiety levels, and worry about panic attacks. Substantial reductions in symptomatology are evident on all measures.

Fig. 3.

Panic attack progress record showing the client’s frequency of weekly panic attacks

Fig. 4.

Panic attack progress record showing the client’s percentage of anxiety and worry about panic each week

Additionally, the client’s anxiety levels were assessed at pre-, mid-, and post- assessment stages using the BAI (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Sowing pre-, mid-, and post-assessment scores on the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI).

Discussion

Overall, the client showed improvements; after the therapy Danny was able to understand the fundamentals of panic disorder, the ABC models, and was able to do the DTR. Although there were improvements on BAI, his anxiety level was still at a moderate level. With the help of CBT, he managed to get his panic disorder under control. On the hindsight, the client also had to deal with his past, surroundings, and conflicts with his family members. It was unresolved as CBT does not deal with the past issues (Table 2). In terms of his general health, his general practitioner was pleasantly surprised with his blood pressure readings. There was a noticeable improvement in his blood pressure readings- his blood pressure readings normalized at the end of the CBT sessions and the general practitioner decided to stop his antihypertensive medications.

Table 2. Comparison between the traditional CBT module and adapted Religion-cultural CBT .

| Traditional CBT | Adapted Religion-cultural CBT | |

| Language | CBT manuals mostly in the English language | CBT manual in Bahasa Malaysia – the national language of Malaysia |

| Manual | CBT manual is designed by westerners using Western concepts that may not be compatible with the Malay culture | CBT Manual that is modified and adjusted according to the norms of Malaysian society, therefore, is culturally appropriate |

| Relaxation techniques |

Traditional relaxation techniques – slow breathing techniques, progressive muscular relaxation Clients encouraged to practice twice a day and grade before and after |

On top of the traditional relaxation techniques, Danny was asked to practice the slow breathing techniques after his Fajr and Isha’a prayers for 3-5 minutes. He was encouraged to pray five times a day regularly following the second Pillar of Islam. Prayer, a form of meditation, encourages a sense of being and promotes relaxation |

| Lifestyle modification | Lifestyle modification in the form of exercise, healthy eating |

For Danny, he was encouraged to read verses of the Holy Quran and zikr (commemoration of Allah’s name) after his prayers, as part of enhancing his spirituality. He was advised to live a healthy lifestyle and live per his Islamic values – to follow the customs of Prophet Muhammad S.A.W (PBUH). |

| Gratitude exercises – gratitude is appreciating what is meaningful and valuable to self. it represents a state of being thankful and appreciating. | Clients are taught to be grateful for their life, situations, family etc. | Danny was taught to focus on the Islamic based on gratitude. He was encouraged to be grateful to God, people, and his surroundings through gratitude exercises. He was encouraged to refer to the Holy Quran and the work and experiences of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) in the Holy Quran who showed the highest level of gratitude to God despite unimaginable sufferings. |

| Invivo situational exposure | Clients choose the agoraphobic situations which they’ve avoided previously | Danny opted to perform this at a place close to his heart- the Mosque |

| Spirituality when discussing support system in CBT | Western CBT mentions spirituality without extra emphasis on it |

Danny particularly mentioned religion and spirituality when talking about the support system. He considers himself a spiritual Muslim and believes in God. |

Therefore, other therapies that would help Danny are as follows:

Psychodynamic psychotherapy: to deal with unresolved issues from the past and help to cope with it;

Family therapy: if it is possible, his family should be brought in to help them understand that he has a problem and needs their support to get better.

For Danny, his good prognostic factors were his strong Islamic values, good intelligence, being of good insight, and awareness of his illness. He was motivated to learn and willing to practice things learnt from psychotherapy (CBT). His response to the psychotherapy was fair. However, factors against him were the long duration of untreated illness (14 years), being diagnosed with early onset-hypertension (with a strong family history of cardiac illness), on-going stressors like poor relationship and support from family, unresolved conflicts from the past, and his dissatisfaction with his family. While weighing the good and bad prognostic factors, his prognosis guarded as he still had a lot of ongoing unresolved conflicts. However, to be fair to him, if he follows the recommendations, there is no doubt his prognosis will improve.

Conclusion

A culturally and religiously modified CBT was applied to the treatment of a male Malaysian Muslim having a 14-year history of panic disorder with agoraphobia. His attacks had severely influenced his occupational, educational, and social life. These symptoms also generated the secondary problems of low self-esteem. The success of this approach was attributed by the client with the realization that his cognitive distortions worsened his panic attack. He acknowledged that negative thinking exacerbated his anxiety which was manifested through physical symptoms. The interoceptive exposure, cognitive rehearsal, and in vivo situational exposure helped in correcting the client’s catastrophic interpretation of physical symptoms experienced as a part panic attack. Through regular homework practice and exercise, he gradually learned how to manage his anxiety and target body areas having the highest muscle tension. Danny’s report of improved psychological status is encouraging and indicates that further investigation of this topic is needed in the form of controlled trials.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Director-General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article. Also, the authors would like to thank the client for giving permission for publishing the study.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted per the Ethical Standards of the National and/or Institutional Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its Later Amendments or Comparable Ethical Standards. Written Informed Consent was obtained from the participant. Also, formal approval was taken from the respective authors of the tools for data collection.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Cite this article as: Subhas N, Mukhtar F, Munawar Kh. Adapting cognitive-behavioral therapy for a Malaysian muslim. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2021 (25 Feb);35:28. https://doi.org/10.47176/mjiri.35.28

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Funding:None

References

- 1. Tyrer H. Tackling health anxiety: A CBT handbook. RCPsych Publications; 2013.

- 2.Tolin DF. Is cognitive–behavioral therapy more effective than other therapies?: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(6):710–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Apeldoorn F, Van Hout W, Mersch P, Huisman M, Slaap B, Hale III W. et al. Is a combined therapy more effective than either CBT or SSRI alone? Results of a multicenter trial on panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(4):260–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arch JJ, Craske MG. Implications of naturalistic use of pharmacotherapy in CBT treatment for panic disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1435–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westen D, Morrison K. A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: an empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Addis ME, Hatgis C, Cardemil E, Jacob K, Krasnow AD, Mansfield A. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder versus treatment as usual in a managed care setting: 2-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(2):377. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heldt E, Manfro GG, Kipper L, Blaya C, Isolan L, Otto MW. One-year follow-up of pharmacotherapy-resistant patients with panic disorder treated with cognitive-behavior therapy: outcome and predictors of remission. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(5):657–65. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peter H, Brückner E, Hand I, Rohr W, Rufer M. Treatment outcome of female agoraphobics 3–9 years after exposure in vivo: a comparison with healthy controls. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2008;39(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Souza R, Rodrigo A, Keks N, Tonso M, Tabone K. An open randiomised control study of an add on spiritually augmented cognitive behavior therapy in patients with depression and hopelessness. Aust New Z J Psychiatr. 2003;37 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Husain A, Hodge DR. Islamically modified cognitive behavioral therapy: Enhancing outcomes by increasing the cultural congruence of cognitive behavioral therapy self-statements. Int Soc Work. 2016;59(3):393–405. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varma S, Zain AM. In the field: Cognitive therapy in Malaysia. J Cogn Psychother. 1996;10(4):305–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukhtar F, Oei TP, Yaacob M. Effectiveness of group cognitive behaviour therapy augmentation in reducing negative cognitions in the treatment of depression in Malaysia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2011;12(1):50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. MOH. Management of Major Depressive Disorder. In: Malaysia MoH, editor.; 2019.

- 15. MOH. Management of Bipolar Disorder in Adults. In: Malaysia MoH, editor.; 2014.

- 16.Muzaini H. Informal heritage-making at the Sarawak cultural village, East Malaysia. Tour Geogr. 2017;19(2):244–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.How SY, Heng CS, Abdullah AN. Language Vitality of Malaysian languages and its Relation to Identity. GEMA Online J Lang Studies. 2015;15(2) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmad Z. Multiculturalism And Religio-ethnic Plurality. Cult Relig. 2007;8(2):139–53. doi: 10.1080/14755610701424008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halstead JM. Islamic values: a distinctive framework for moral education? J Moral Educ. 2007;36(3):283–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham JR, Bradshaw C, Trew JL. Cultural considerations for social service agencies working with Muslim clients. Soc Work. 2010;55(4):337–46. doi: 10.1093/sw/55.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwamasa GY. Asian Americans and cognitive behavioral therapy. Behaviour Therapist. 1993;16:233. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pande SK. The mystique of" Western" psychotherapy: an Eastern interpretation. J Nerv Ment Disease. 1968 doi: 10.1097/00005053-196806000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Padesky CA, Greenberger D. Clinician's guide to mind over mood. Guilford Press; 2012.

- 24. Laungani P. Asian perspectives in counselling and psychotherapy. Routledge; 2004.

- 25.McCullough ME. Research on religion-accomodative counseling: Review and meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol. 1999;46(1):92. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pargament KI. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York, NY: Guilford press; 1997.

- 27.Abu Raiya H, Pargament KI. Religiously integrated psychotherapy with Muslim clients: From research to practice. Prof Psychol Research Prac. 2010;41(2):181. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khaiyom JH, Mukhtar F, OT P. Treatments for anxiety disorders in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2019;26(3):24. doi: 10.21315/mjms2019.26.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Razali S, Hasanah C, Aminah K, Subramaniam M. Religious—sociocultural psychotherapy in patients with anxiety and depression. Aust New Z J Psychiatr. 1998;32(6):867–72. doi: 10.3109/00048679809073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabki ZA, Sa’ari CZ, Muhsin SB, Kheng GL, Sulaiman AH, HG HG. K Islamic Integrated Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Shari’ah-Compliant Intervention for Muslims with Depression. Malays J Psychiatry. 2019;28(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furlong M, Oei TP. Changes to automatic thoughts and dysfunctional attitudes in group CBT for depression. Beh Cogn Psychother. 2002;30(3):351–60. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Razali S, Najib M. Help-seeking pathways among Malay psychiatric patients. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46(4):281–9. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rathod S, Kingdon D, Phiri P, Gobbi M. Developing culturally sensitive cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis for ethnic minority patients by exploration and incorporation of service users' and health professionals' views and opinions. Beh Cogn Psychother. 2010;38(5):511–33. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rathod S, Naeem F, Phiri P, Kingdon D. Expansion of psychological therapies. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(3):256–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.193.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rathod S, Kingdon D. Cognitive behaviour therapy across cultures. Psychiatry. 2009;8(9):370–1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haque A, Khan F, Keshavarzi H, Rothman AE. Integrating Islamic traditions in modern psychology: Research trends in last ten years. J Muslim Ment Health. 2016;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodge DR, Nadir A. Moving toward culturally competent practice with Muslims: Modifying cognitive therapy with Islamic tenets. Soc Work. 2008;53(1):31–41. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naeem F, Gobbi M, Ayub M, Kingdon D. Psychologists experience of cognitive behaviour therapy in a developing country: a qualitative study from Pakistan. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2010;4(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sue D, Sue D. Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

- 40.Wolf MM. Social validity: the case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart 1. J Appl Behav Ana. 1978;11(2):203–14. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paukert AL, Phillips L, Cully JA, Loboprabhu SM, Lomax JW, Stanley MA. Integration of religion into cognitive-behavioral therapy for geriatric anxiety and depression. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(2):103–12. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000348363.88676.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodge DR. Alcohol treatment and cognitive-behavioral therapy: Enhancing effectiveness by incorporating spirituality and religion. Soc Work. 2011;56(1):21–31. doi: 10.1093/sw/56.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearce M, Koenig HG. Cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of depression in Christian patients with medical illness. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2013;16(7):730–40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamdan A. Cognitive restructuring: An islamic perspective. J Muslim Ment Health. 2008;3(1):99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas J, Ashraf S. Exploring the Islamic tradition for resonance and dissonance with cognitive therapy for depression. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2011;14(2):183–90. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vasegh S, editor. Psychiatric treatments involving religion: Psychotherapy from an Islamic perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

- 47.Vasegh S. Cognitive therapy of religious depressed patients: Common concepts between Christianity and Islam. J Cogn Psychother. 2011;25(3):177–88. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vasegh S. Religious Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Muslim version 2014; Available from: http://www.spiritualityandhealth.duke.edu/images/pdfs/RCBT%20Manual%20Final%20Muslim%20Version%203-14-14.pdf.

- 49.Rathod S, Gega L, Degnan A, Pikard J, Khan T, Husain N. et al. The current status of culturally adapted mental health interventions: a practice-focused review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatr Diseas Treat. 2018;14:165. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S138430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao S, Young D, Zhang H. Taoistic cognitive psychotherapy for neurotic patients: A preliminary clinical trial. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci. 1998;52(S6):S238–S41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb03232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawkins RS, Tan S-Y, Turk AA. Secular versus Christian inpatient cognitive-behavioral therapy programs: Impact on depression and spiritual well-being. J Psychol Theol. 1999;27(4):309–18. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naeem F, Waheed W, Gobbi M, Ayub M, Kingdon D. Preliminary Evaluation of Culturally Sensitive CBT for depression in Pakistan: Findings from developing Culturally-Sensitive CBT project (DCCP) Beh Cogn Psychother. 2011;39(2):165–73. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naeem F, Saeed S, Irfan M, Kiran T, Mehmood N, Gul M. et al. Brief culturally adapted CBT for psychosis (CaCBTp): A randomized controlled trial from a low income country. Schizophr Res. 2015;164(1):143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gangdev PS. Faith-assisted cognitive therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Aust New Z J Psychiatr. 1998;32(4):575–8. doi: 10.3109/00048679809068333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Azhar MZ, Varma SL. Religious Psychotherapy in Depressive Patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1995;63(3-4):165–8. doi: 10.1159/000288954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azhar MZ, Varma SL. Religious psychotherapy as management of bereavement. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91(4):233–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Azhar MZ, Varma SL, Dharap AS. Religious psychotherapy in anxiety disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(1):1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Razali SM, Aminah K, Khan UA. Religious–Cultural Psychotherapy in the Management of Anxiety Patients. Transcult Psychiatry. 2002;39(1):130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Razali SM, Hasanah CI, Aminah K, Subramaniam M. Religious—Sociocultural Psychotherapy in Patients with Anxiety and Depression. Aust New Z J Psychiatr. 1998;32(6):867–72. doi: 10.3109/00048679809073877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sabki ZA, Sa’ari CZ, Muhsin SBS, Kheng GL, Sulaiman AH, Koenig HG. Islamic Integrated Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Shari’ah-Compliant Intervention for Muslims with Depression. Malays J Psychiatr. 2019;28(1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abdul Khaiyom JH, Mukhtar F, Ibrahim N, Mohd Sidik S, Oei TPS. Psychometric Properties of the Catastrophic Cognitions Questionnaire‐Modified (CCQ‐Modified) Among Community Samples in Malaysia. Stress Health. 2016;32(5):543–50. doi: 10.1002/smi.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Beck J, Beck AT. Cognitive behavior therapy. New York: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Publication; 2011.

- 64.Clark DM. A cognitive approach to panic. Behav Res Thery. 1986;24(4):461–70. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Oei TP. CBT Anxiety/Panic Disorder Program work book.. Toowong Private Hospital; 2000.

- 66. Mukhtar F, Oei TP. Terapi Kognitif Tingka Laku begi Rawatan Kemurungan.. Penerbit Universiti Putra Malaysia; 2011.

- 67. Mukhtar F, Tian PO. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of depression. Serdang, Selangor: Universiti Putra Malaysia; 2011.

- 68. TP. O. CBT Anxiety/Panic Disorder Program work book.: Toowong Private Hospital; 2000.

- 69.Manfro GG, Heldt E, Cordioli AV, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy in panic disorder. Rev Brasil Psiquiat. 2008;30 Suppl 2:s81–7. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462008000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]