Abstract

COVID-19 has placed a significant burden on the healthcare system, making it necessary to implement new tools that allow patients to be monitored remotely and guarantee quality and continuity of care. The usefulness and acceptance by patients of a virtual caregiver designed for follow-up in the month following hospital discharge for COVID-19 are evaluated. The virtual assistant, based on voice and artificial intelligence technology, made telephone calls at 48 h, seven days, 15 days, and 30 days after discharge and asked five questions about the patient’s health. If the answer to any of the questions was affirmative, it generated an alert that was transferred to a healthcare professional One hundred patients were included in the project and 85 alerts were generated in 45 of the patients, most at one month after hospital discharge. The nursing staff resolved 94% of them by telephone. Patient satisfaction with the virtual caregiver was high.

Keywords: COVID-19, Virtual caregiver, Virtual assistant, Artificial intelligence, Follow-up after discharge

Abstract

La COVID-19 ha supuesto una gran sobrecarga para el sistema sanitario, y ha sido necesario poner en marcha herramientas nuevas para realizar el seguimiento no presencial de los pacientes y garantizar la calidad de sus cuidados. Se evalúa la utilidad y aceptación de los pacientes de un cuidador virtual diseñado para su seguimiento tras el alta hospitalaria por COVID-19. El asistente virtual, con tecnología de voz e inteligencia artificial, realizó llamadas telefónicas a las 48 horas, 7, 15 y 30 días del alta, formulando 5 preguntas sobre su estado de salud. Si la contestación era afirmativa, generaba una alerta que se transfería a un profesional sanitario. Se incluyeron 100 pacientes en el proyecto. Se generaron 85 alertas en 45 de los pacientes, la mayoría de ellas al mes del alta; el 94% lo resolvió enfermería telefónicamente. La satisfacción de los pacientes con el cuidador virtual fue alta.

Palabras clave: COVID-19, Cuidador virtual, Asistente virtual, Inteligencia artificial, Seguimiento tras el alta

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed a challenge to healthcare systems which have been overwhelmed in trying to meet the care needs for affected patients both in primary care and in the hospital setting1. In addition, it has boosted the integration and use of new technologies adapted to the pandemic circumstances in order to aid patient treatment and follow-up.

The aim of this study is to assess the usefulness and user satisfaction of a virtual caregiver designed to monitor the health of patients admitted to hospital for COVID-19 for a period of 30 days post-discharge.

Methods

A total of 100 patients were included who had been infected by SARS-CoV-2 and were discharged between 14 May and 15 August 2020 from La Princesa University Hospital in Madrid.

The hospital’s Internal Medicine service performed follow-up jointly with Tucuvi, a company that has developed a virtual assistant for the healthcare sector, voice technology, and artificial intelligence, with the aim of improving quality of care. The virtual assistant made follow-up phone calls to the patients at 48 h, 7 days, 15 days, and 30 days post-discharge. If contact could not be made with the patient on the first try, a total of 3 attempts were made for each scheduled call.

The virtual assistant asked the following questions to the patient or their caregiver: Do you find it more difficult to breathe now than when you were discharged? Have you had a fever in the past 24 h? How high? Compared to when you were discharged, do you feel better or worse? Have you developed any new discomfort? What type? Have you had to go to the Emergency Department since you were discharged?

Any affirmative answer generated an alert and an Excel report with the patient’s ID and the type of alert. The hospital nursing staff was responsible for contacting the patient personally within the next 24 h to tell them what steps to take. When necessary, the patient was referred to the medial team. The nursing staff also made 3 call attempts in the event that contact could not be established with the patient on the initial call.

One week after completion of the study, a brief telephone survey was performed to determine user satisfaction. The questions were as follows: level of satisfaction with the system to improve communication with the health team; did the system help better control the evolution of their illness, and the level of satisfaction with the voice used by the system that called them. They were asked to respond to the questions with scores between 1 (minimum) and 5 (maximum).

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the La Princesa University Hospital Research Ethics Committee. The patients gave their verbal consent, which was recorded in the medical history, to be included in the study.

Results

Of the 100 patients included, 59 were men and 41 women, with their ages ranging from 18 to 93 years. Some 5% were aged between 18 and 31 years; 10% between 31 and 44 years; 8% between 44 and 57 years; 29% between 57 and 70 years; 26% between 70 and 83 years; and 22% between 83 and 93 years. All the patients had been admitted for pneumonia due to COVID-19 or readmitted for complications following discharge for COVID-19.

A total of 680 called were made, of which 423 were answered (62%) and 278 completed (66%). The average length of the calls was 2 min 16 s.

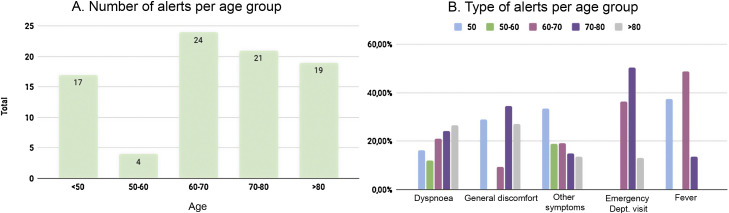

Some 15.25% of the calls led to an alert and were generated by 45 patients. The total number of alerts detected was 85, and their distribution according to age was: <50 years, 17 alerts; 50–60 years, 4 alerts; 60–70 years, 24 alerts; 70–80 years, 21 alerts; and >80 years, 19 alerts. The mean number of alerts detected per each call was 1.35. Fig. 1 shows the alert frequency and type by age group.

Figure 1.

Frequency (A) and type of alert (B) by age groups.

The alert for difficulty breathing was the most common as age increased, while fever was the least common alert among the older patients. The most frequent alerts in patients under the age of 80 were dyspnoea and general discomfort, however globally fever was the most common alert.

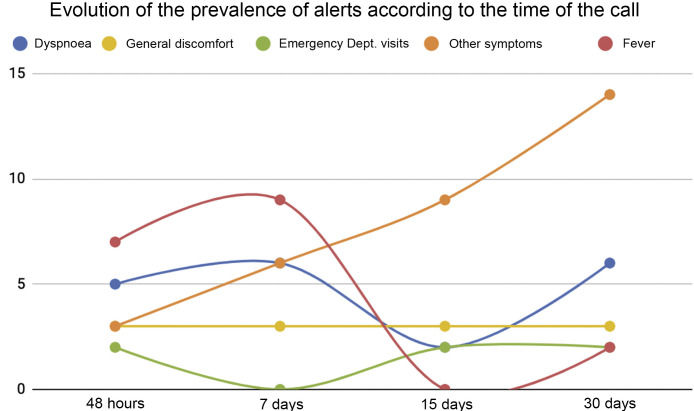

Fig. 2 shows the evolution of the prevalence of alerts according to the time of the call.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the prevalence of alerts according to the time of the call.

The highest number of alerts was detected in the calls made at 30 days, the majority in relation to the onset of new symptoms unrelated to COVID-19.

Five patients went to the Emergency Department, two referred by the primary care team and three of their own volition. On two occasions, due to causes directly related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, general discomfort, and fever, patients attended the Emergency Department of their own volition on a day prior to the follow-up call. Neither of the two patients required admission.

Of the 87 calls made by the nursing staff, 49 (56%) calls were alerts generated by the Tucuvi telephone assistant, 42 (86%) of which were confirmed by the nursing staff. Contact was not made with the patient in four calls and the alert was not confirmed in three calls due to the following reasons: having not understood the question, not accurately explaining their situation leading to the generation of an alert, or wanting to speak with the nursing staff.

The nursing staff made a total of 38 (44%) calls due to the assistant not being able to contact a patient. The alert was confirmed in six of them; in 17, the patient/caregiver did not report any alert symptoms, and in 15 no response was obtained.

In total, the nursing staff confirmed 48 (55% of all calls) alerts and referred 6% to the medical team.

One week after the end of follow-up, user satisfaction was evaluated by means of a short survey. A total of 46 patients completed the survey. The averages ratings were: the question regarding satisfaction with use of the system to improve communication with the health team: 3.8/5; regarding whether the system helped to better control the evolution of their illness: 3.4/5; and regarding the level of satisfaction with the voice used by the system that called them: 4/5 (1 being the minimum and 5 the maximum rating).

Thirty-nine patients stated their appreciation for the virtual assistant service due to: follow-up, concern for the patients, rapid communication, frequency of contact.

Discussion

Telephone follow-up with patients following hospital discharge has been identified as a useful and cost-effective tool2, 3, 4 that tends to be implemented in chronic pathologies such as heart failure, COPD, or diabetes mellitus5, 6. However, this strategy uses nursing staff resources as it requires nurses to call all the discharged patients7. The option of selecting those that truly require a personalised call by means of an alert system that uses new technologies stands out as a significant advance. Automatic calling systems are a pragmatic and economic manner of improving telephone follow-up8, 9, 10, 11.

In our experience, the virtual assistant facilitated follow-up for a highly vulnerable group, namely patients admitted for COVID-19. It enabled the identification of patients requiring specific health interventions and prevented any feelings of neglect or difficulty to access the health system that they might have experienced.

The age range of the patients included in this project is wide and representative of all patients admitted for COVID-19. The calls from nursing staff to patients that could not be contacted by the virtual assistant reduced the number of patients that could not be contacted down to 15 out of 100 patients. The nurses resolved 94% of the alerts and those that could not be solved were associated with the care pathway that the patient was to be following.

One of the limitations to evaluating satisfaction is the small number of patients/caregivers that responded to the survey. Regardless, it represents almost half of the sample.

In summary, the virtual caregiver is a useful tool for performing follow-up on patients following discharge, regardless of their age. The majority of alerts can be resolved by the nursing staff and patient satisfaction with the virtual caregiver alert system was high.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Please cite this article as: García Bermúdez I, González Manso M, Sánchez Sánchez E, Rodríguez Hita A, Rubio Rubio M, Suárez Fernández C. Utilidad y aceptación del seguimiento telefónico de un asistente virtual a pacientes COVID-19 tras el alta. Rev Clin Esp. 2021;221:464–467.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 situation report — 51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinberger M., Tierney W.M., Booher P., Katz B.P. Can the provision of information to patients with osteoarthritis improve functional status? A randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1577–1583. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780321212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBusk R.F., Houston Miller N., Superko H.R., Dennis C.A., Thomas R.J., Lew H.T., et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:721–729. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasson J., Gaudette C., Whaley F., Sauvigne A., Paribeau P., Welch H.G., et al. Telephone care as a substitute for routine clinic follow-up. JAMA. 1992;267:1788–1793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piette J.D., Weinberger M., McPhee S.J., Mah C.A., Kraemer F.B., Crapo L.M. Do automated calls with nurse follow-up improve self-care and glycemic control among vulnerable patients with diabetes? Am J Med. 2000;108:20–27. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H., Park J.-B., Choi S.W., Yoon Y.E., Park H.E., Lee S.E., et al. Impact of a telehealth program with voice recognition technology in patients with chronic heart failure: feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5:e127. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.7058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson J.E., Nelson D.E., Wilson R.W. Telephone coverage and measurement of health risk indicators: data from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1392–1395. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leirer V.O., Morrow D.G., Pariante G., Doksum T. Increasing influenza vaccination adherence through voice mail. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:1147–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb06679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman R.H. Automated telephone conversations to assess health behavior and deliver behavioral interventions. J Med Syst. 1998;22:95–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1022695119046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dini E.F., Linkins R.W., Chaney M. Effectiveness of computer-generated telephone messages in increasing clinic visits. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:902–905. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170210076013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leirer V.O., Morrow D.G., Tanke E.D., Pariante GM. Elders’ nonadherence: its assessment and medication reminding by voice mail. Gerontologist. 1991;31:514–520. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]