Abstract

Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) are ion channels that mediate the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum/endoplasmic reticulum, mutations of which are implicated in a number of human diseases. The adjacent C-terminal domains (CTDs) of cardiac RyR (RyR2) interact with each other to form a ring-like tetrameric structure with the intersubunit interface undergoing dynamic changes during channel gating. This mobile CTD intersubunit interface harbors many disease-associated mutations. However, the mechanisms of action of these mutations and the role of CTD in channel function are not well understood. Here, we assessed the impact of CTD disease-associated mutations P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E on Ca2+− and caffeine-mediated activation of RyR2. The G4955E mutation dramatically increased both the Ca2+-independent basal activity and Ca2+-dependent activation of [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2. The P4902S and E4950K mutations also increased Ca2+ activation but had no effect on the basal activity of RyR2. All four disease mutations increased caffeine-mediated activation of RyR2 and reduced the threshold for activation and termination of spontaneous Ca2+ release. G4955D dramatically increased the basal activity of RyR2, whereas G4955K mutation markedly suppressed channel activity. Similarly, substitution of P4902 with a negatively charged residue (P4902D), but not a positively charged residue (P4902K), also dramatically increased the basal activity of RyR2. These data suggest that electrostatic interactions are involved in stabilizing the CTD intersubunit interface and that the G4955E disease mutation disrupts this interface, and thus the stability of the closed state. Our studies shed new insights into the mechanisms of action of RyR2 CTD disease mutations.

Keywords: cardiac arrythmias, ryanodine receptor, C-terminal domain, channel gating, Ca2+ release, Ca2+ activation, [3H]ryanodine binding, single-channel recordings

Abbreviations: cDNA, complementary DNA; CPVT, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; CTD, C-terminal domain; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; NTD, N-terminal domain; RyR, ryanodine receptor; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; KRH, Krebs–Ringer–Hepes

The cardiac ryanodine receptor (RyR2) is an intracellular Ca2+ release channel residing in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane of cardiomyocytes. It plays an essential role in excitation–contraction coupling by controlling the release of Ca2+ from the SR into the cytoplasm (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). RyR2 is also abundantly expressed in the brain and critically involved in learning and memory (6, 7, 8, 9). Because of its important physiological roles, mutations in RyR2 can cause cardiac arrhythmias, cardiomyopathies, and neuronal disorders (4, 10, 11, 12, 13).

RyR2 mutations are primarily associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). CPVT is characterized by emotional or physical stress–induced ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death in structurally normal hearts (11, 14, 15, 16, 17). RyR2 mutations have also been associated with cardiomyopathies as well as cardiac arrhythmias (11, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). To date, more than 300 RyR2 missense/nonsense mutations have been reported in the Human Gene Mutation Database (http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php). Although RyR2 mutations are distributed over the entire primary sequence, most of them are clustered in four hot spots in the linear sequence of RyR2: residues 44 to 466, 2246 to 2534, 3778 to 4201, and 4497 to 4959. Structurally, these four hot spots are located at the N-terminal domain (NTD), helical domain, central domain, and channel domain (10, 11, 25). The NTD (residues 1–642) comprises three subdomains: NTD-A, NTD-B, and NTD-C. We showed that NTD-A is important for Ca2+ release termination, NTD-B is involved in channel suppression, and NTD-C is critical for channel activation and expression (26). Interestingly, the NTD harbors a number of RyR2 mutations associated with cardiomyopathies (16, 21, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33). A common defect of NTD RyR2 mutations is a reduced threshold for Ca2+ release termination and an increased amplitude of fractional Ca2+ release (34). Notably, most NTD disease mutations are located at the interfaces between N-terminal subdomains or between NTD and other RyR2 domains. These mutations may affect normal channel gating by disrupting domain–domain interactions (35).

The central domain is important for channel activation by Ca2+. It contains a high-affinity Ca2+-binding site (36, 37, 38). We have shown that disease-associated RyR2 mutations in the central domain enhanced the cytosolic Ca2+-dependent activation of RyR2, reduced the activation and termination thresholds for spontaneous Ca2+ release in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells, and reduced Mg2+ inhibition (39, 40).

The channel domain includes the transmembrane domain and the C-terminal domain (CTD). The CTD (residues 4887–4968) is highly conserved among RyR isotypes from different species. The CTD at the end of the S6 inner pore helix is clamped by the U-motif from the central domain to stabilize the channel pore formed by four S6 inner pore helices (one from each RyR2 protomer) (25). Structural analysis showed that there is little or no relative motion among the U-motif, CTD, and the cytoplasmic portion of the S6 inner pore helix during channel opening and closing. This rigid connection is further stabilized by a zinc-binding motif within the CTD (25). In addition to coupling the movement of the central domain to the S6 inner pore helix, CTD is also involved in the binding of three important RyR2 modulators: Ca2+, ATP, and caffeine. Ca2+ binds to RyR2 at the interface between CTD and central domain, whereas ATP binds at the interface between CTD and the cytoplasmic portion of S6 inner pore helix. Caffeine binds at the interface among CTD, U-motif, and S2S3 cytoplasmic loop (36, 37, 38).

There are many disease-associated RyR2 mutations located in CTD (16, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51). Most of these mutations are associated with CPVT and sudden death. Interestingly, in addition to cardiac disorders, the CTD RyR2 G4955E mutation is also associated with neuronal phenotypes, including intellectual disability and seizure (45). 3D structural analysis reveals that many CTD mutations are located at domain interfaces. For instance, the P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E mutations are located at the intersubunit interface between two adjacent CTDs. Interestingly, adjacent CTDs interact extensively with each other only in the closed but not in the open RyR2 channel. Thus, the 3D location of these disease mutations suggests that they may disrupt intersubunit CTD–CTD interactions and thus the stability of the closed state of the channel. To test this hypothesis, in the present study, we assessed the impact of disease-associated mutations P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E on channel function. We found that all these four disease mutations reduced the activation and termination thresholds for store overload–induced spontaneous Ca2+ release (SOICR). Particularly, the G4955E mutation severely destabilized the stability of the closed state and dramatically increased the activation of the RyR2 channel by luminal Ca2+, probably by altering the electrostatic interactions at the CTD–CTD intersubunit interface. Our work provides important new insights into the role of CTD in channel function and the pathogenic mechanism of CTD disease mutations.

Results

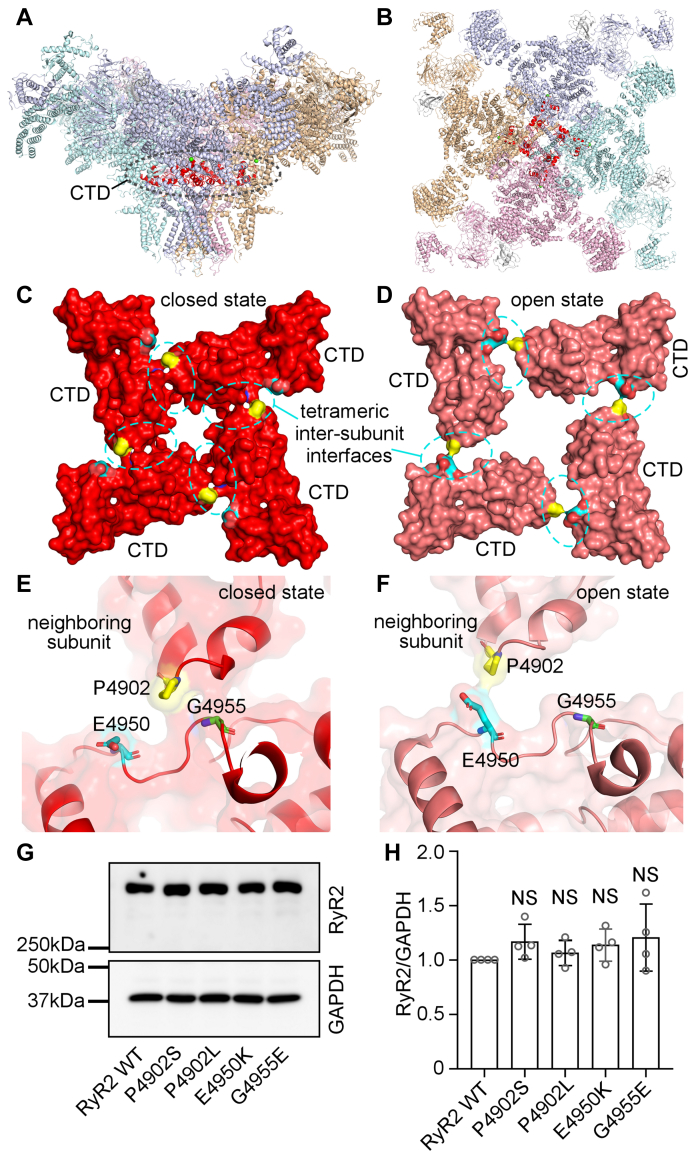

Localization of disease-associated RyR2 CTD mutations at the tetrameric intersubunit interface

The RyR2 CTD contains the last 82 amino acids (residues 4887–4968) and harbors multiple disease-associated mutations, including P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E. The G4955E mutation was associated with severe atrial arrhythmias, intellectual disability, and seizure (45), whereas P4902S, P4902L, and E4950K were associated with CPVT and sudden death (49, 50, 51). The RyR2 channel gate is formed by four S6 inner pore helices, one from each RyR2 protomer. Adjacent CTDs at the C-terminal end of each S6 inner pore helix interact with each other and form a “ring-like” structure that likely plays a role in stabilizing the channel pore (Fig. 1, A and B) (25). Interestingly, these disease-associated RyR2 mutations are located in the CTD tetrameric intersubunit interface (Fig. 1, C and D). Furthermore, this CTD intersubunit interface undergoes substantial conformational changes during channel opening and closing (Fig. 1, E and F). In the closed state, there is an extensive contact between two adjacent CTDs, in which a region encompassing residue P4902 from one RyR2 subunit interacts with a region encompassing residue G4955 from the neighboring subunit. However, in the open state, there is little contact between two adjacent CTDs. The P4902 residue is moved away from G4955 but close to a region encompassing residue E4950 from the neighboring subunit (Fig. 1, E and F). These 3D structural analyses suggest that residues P4902, E4950, and G4955 may be involved in CTD–CTD intersubunit interactions in the closed state, and that mutations of these residues may disrupt CTD intersubunit interface, thus altering closed-state stability and channel gating. However, these hypotheses have yet to be tested. To understand the impact of these disease-associated RyR2 CTD mutations on channel function, we generated these mutations using site-directed mutagenesis and expressed them in HEK293 cells. Western blot analysis showed that the protein expression level of these RyR2 mutants was compatible to that of the RyR2 WT (Fig. 1, G and H). Note that there are no endogenous RyR2 proteins and function detected in HEK293 cells (52, 53). Functional characterization of each of these mutants was then performed as described later.

Figure 1.

C-terminal domain (CTD) intersubunit interface and locations of CTD disease mutations in the 3D structure of RyR2.A, side view of the RyR2 tetramer. B, top view of the RyR2 tetramer. The CTD domain from each subunit is highlighted in red. C and D, the surface presentation of the CTD domain in the closed (C) and open (D) states. Residue P4902 is colored in yellow, E4950 in cyan, and G4955 in green. E and F, transparent CTD surface and ribbon presentation of two neighboring subunits in the closed (E) and open (F) states. Disease-associated CTD mutations are indicated in the same color scheme as in panels C and D. All 3D structure images were generated from Protein Data Bank 5GO9 (closed state) and 5GOA (open state) using PyMOL. G and H, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the RyR2 WT or disease-associated CTD mutant complementary DNAs. Immunoblotting of RyR2 WT and mutants from the same amount of transfected cell lysates (G). Note that the RyR2 band with an expected molecular weight of 565 kDa is located inside the separating gel. The expression levels of the WT and disease-associated mutants were normalized to that of GAPDH (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 0.8741, p = 0.5023) (H). Data shown are mean ± SD from four separate experiments. HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; NS, not significant; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor.

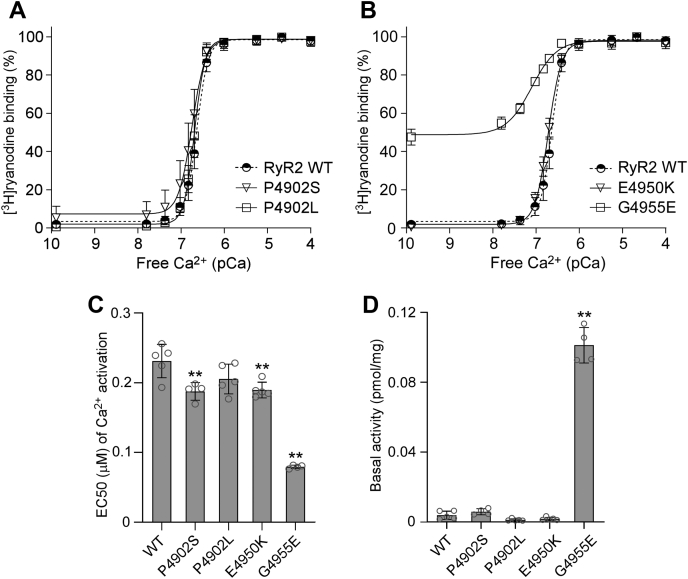

Effect of disease-associated CTD mutations on [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2

[3H]ryanodine binding assay is a widely used method for assessing the open probability of the RyR channel, because ryanodine only binds to the open state of RyRs (54, 55, 56, 57). Here, we performed [3H]ryanodine binding assay to determine the impact of CTD mutations on the basal activity and sensitivity of RyR2 to activation by a wide range of Ca2+ concentrations. As shown in Figure 2 and Fig. S1, the G4955E mutation markedly increased the Ca2+-dependent activation of RyR2 with an EC50 of 0.08 μM, which is significantly lower than that of the RyR2 WT (EC50 = 0.23 μM). Notably, a substantially elevated level of [3H]ryanodine binding to the G4955E mutant was detected in the near absence of Ca2+ (~0.1 nM), indicating that the G4955E mutation dramatically increases the Ca2+-independent basal activity of [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 (Fig. 2, B and D and Table 1). The P4902S and E4950K mutations also significantly decreased the EC50 (0.19 μM for P4902S and 0.19 μM for E4950K) of Ca2+-dependent activation of [3H]ryanodine but did not significantly affect the Ca2+-independent basal activity of [3H]ryanodine binding, compared with RyR2 WT (Fig. 2, A–D and Table 1). On the other hand, the P4902L mutation did not significantly affect the EC50 or the basal activity of [3H]ryanodine binding (Fig. 2, A, C, and D and Table 1). Therefore, disease-associated CTD mutations, G4955E, P4902S, and E4950K, but not P4902L, enhance Ca2+-dependent activation and/or Ca2+-independent basal activity of RyR2.

Figure 2.

Effects of disease-associated CTD mutations on [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2.A and B, [3H]ryanodine binding to cell lysates prepared from HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the RyR2 WT or disease-associated CTD mutant complementary DNAs was carried out at various Ca2+ concentrations (0.1 nM–0.1 mM). The amounts of [3H]ryanodine binding at various Ca2+ concentrations were normalized to the maximal binding (100%). C, EC50 values of Ca2+ activation (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 50.5, p < 0.0001). D, basal activity (in the near absence of Ca2+, ~0.1 nM) of [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 346.5, p < 0.0001). Data shown are mean ± SD from four to five separate experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus WT. CTD, C-terminal domain; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor.

Table 1.

Effects of mutations on [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2

| Mutation | EC50 (μM) of Ca2+ activation | Adjusted p value | Basal activity (pmol/mg) | Adjusted p value | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Disease-associated mutations | |||||

| RyR2 WT | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 3.8 × 10−3 ± 2.3 × 10−3 | 5 | ||

| P4902S | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.0042 | 5.8 × 10−3 ± 1.7 × 10−3 | 0.5207 | 4 |

| P4902L | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.0873 | 1.1 × 10−3 ± 6.2 × 10−4 | 0.1692 | 5 |

| E4950K | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.0039 | 1.7 × 10−3 ± 8.9 × 10−4 | 0.3388 | 5 |

| G4955E | 0.08 ± 0.00 | <0.0001 | 1.0 × 10−1 ± 1.0 × 10−2 | 0.001 | 4 |

| EC50 ANOVA summary: F = 50.5, p < 0.0001; basal activity ANOVA summary: F = 346.5, p < 0.0001 | |||||

| B. Other mutations | |||||

| RyR2 WT | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 3.8 × 10−3 ± 2.3 × 10−3 | 5 | ||

| P4902D | 0.07 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | 9.9 × 10−2 ± 2.5 × 10−2 | 0.0048 | 5 |

| P4902K | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.0003 | 1.2 × 10−2 ± 1.2 × 10−2 | 0.6652 | 4 |

| G4955D | 0.08 ± 0.02 | <0.0001 | 1.1 × 10−1 ± 1.8 × 10−2 | 0.0055 | 4 |

| G4955K | 0.47 ± 0.04 | <0.0001 | 1.2 × 10−4 ± 2.4 × 10−4 | 0.0984 | 4 |

| G4955L | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.0002 | 2.0 × 10−4 ± 4.0 × 10−4 | 0.1082 | 4 |

| D4956A | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.3966 | 1.3 × 10−3 ± 1.5 × 10−3 | 0.3369 | 5 |

| EC50 ANOVA summary: F = 142.7, p < 0.0001; basal activity ANOVA summary: F = 71.9, p < 0.0001 | |||||

Data are presented as mean ± SD. The significance of differences in EC50 and basal activity between WT and mutants was evaluated by performing one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons post hoc testing. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Effect of disease-associated CTD mutations on caffeine activation of RyR2

We used the [3H]ryanodine binding assay to ascertain the impact of disease-associated CTD mutations on RyR2 activity in the context of solubilized RyR2 channels. To assess the impact of CTD mutations on RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release in the cellular context, we measured caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells expressing RyR2 WT or mutants (Fig. 3 and Table 2). It has previously been shown that caffeine induces Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores by sensitizing the RyR2 channel to activation by cytosolic and luminal Ca2+ (58, 59). Here, we performed caffeine-induced Ca2+ release assays in HEK293 cells to assess the impact of disease-associated CTD mutations on the sensitivity of RyR2 to activation by cytosolic and luminal Ca2+. The amplitude of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells transfected with RyR2 WT increased progressively with each cumulative addition of caffeine (from 0.05 to 0.5 mM) with an apparent EC50 of caffeine activation of ~0.20 mM and then decreased with further cumulative additions of caffeine (from 1.0 to 5 mM), likely because of the depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by the prior additions of caffeine (0.025–0.5 mM) (Fig. 3, A and B). All four CTD mutations, P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E, enhanced caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells, shifting the caffeine response curve to the left (Fig. 3, A–C and Table 2). Particularly, the impact of the G4955E mutation was most robust, which is consistent with its effect on [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2. Interestingly, although the P4902L mutation has no significant effect on Ca2+-dependent activation of [3H]ryanodine binding, it markedly increased caffeine activation of RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release (Fig. 3). Thus, RyR2 mutations could differentially affect Ca2+ activation of [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 and caffeine activation of RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release.

Figure 3.

Effects of disease-associated CTD mutations on caffeine activation of RyR2.A, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with RyR2 WT or disease-associated CTD mutant complementary DNAs. The fluorescence intensity of the Fluo-3-loaded transfected cells was monitored continuously before and after each caffeine addition. Note that the small drops in fluorescence signal immediately after additions of caffeine are due to dilution of the Fluo-3 fluorescent dye by the added caffeine solution. B, the relationships between caffeine-induced Ca2+ release and cumulative caffeine concentrations in HEK293 cells transfected with RyR2 WT, P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E. The amplitude of each caffeine peak was normalized to that of the maximum peak for each experiment. C, the apparent EC50 values of caffeine-induced Ca2+ releases in HEK293 cells transfected with RyR2 WT or mutants (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 40.7, p < 0.0001). Data shown are mean ± SD from five separate experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus WT. CTD, C-terminal domain; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor.

Table 2.

Effects of mutations on caffeine activation of RyR2

| Mutation | Apparent EC50 (mM) | Adjusted p value | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Disease-associated mutations | |||

| RyR2 WT | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 5 | |

| P4902S | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.001 | 5 |

| P4902L | 0.10 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | 5 |

| E4950K | 0.11 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | 5 |

| G4955E | 0.05 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | 5 |

| ANOVA summary: F = 40.7, p < 0.0001 | |||

| C. Other mutations | |||

| RyR2 WT | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 5 | |

| P4902D | 0.05 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | 5 |

| P4902K | 0.09 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | 5 |

| G4955K | 0.43 ± 0.09 | <0.0001 | 4 |

| G4955L | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.0309 | 5 |

| D4956A | 0.38 ± 0.07 | <0.0001 | 4 |

| ANOVA summary: F = 149.7, p < 0.0001 | |||

Data are presented as mean ± SD. The significance of differences in caffeine activation between WT and mutants was evaluated by performing one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons post hoc testing. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

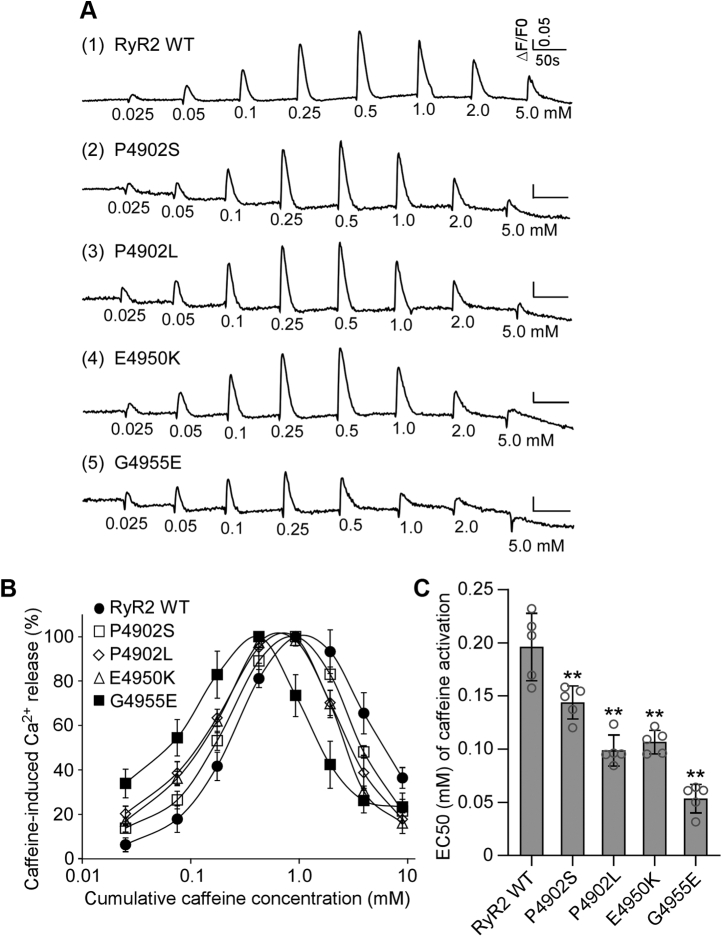

Disease-associated CTD mutations reduce both the activation and termination thresholds for SOICR

We have previously shown that alteration in the threshold for SOICR or spontaneous Ca2+ release is a common mechanism for disease-associated RyR2 mutations (34, 60, 61, 62). To assess whether disease-associated CTD mutations affect the SOICR threshold, we monitored luminal Ca2+ dynamics using FRET-based and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–targeted Ca2+-sensing protein D1ER. As shown in Figure 4 and Fig. S2, HEK293 cells expressing RyR2 WT displayed spontaneous ER Ca2+ oscillations upon elevating extracellular Ca2+ from 0 to 2 mM (to induce Ca2+ overload). We determined the SOICR activation threshold (FSOICR) at which SOICR occurred and the SOICR termination threshold (Ftermi) at which SOICR terminated. All four mutations, P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E, decreased both the activation threshold (WT 92.0%, P4902S 76.4%, P4902L 74.5%, E4950K 83.5%, and G4955E 72.2%) and the termination threshold (WT 58.0%, P4902S 46.0%, P4902L 45.9%, E4950K 48.2%, and G4955E 49.1%) (Fig. 4, A–G). The fractional Ca2+ release (FSOICR − Ftermi) in P4902S (30.5%), P4902L (28.5%), and G4955E (23.2%) but not in E4950K (35.3%) mutant cells was also significantly reduced compared with that of WT cells (34.0%) (Fig. 4H). There was no significant difference in store capacity (Fmax − Fmin) between RyR2 WT and P4902S, P4902L, or E4950K mutant cells. However, the G4955E mutant cells showed slightly reduced store capacity compared with that of the WT (Fig. 4I). Thus, these disease-associated CTD mutations affect SOICR by reducing its activation and termination thresholds.

Figure 4.

Effect of disease-associated CTD mutations on SOICR activation and termination thresholds. Stable and inducible HEK293 cell lines expressing RyR2 WT and mutants were transfected with the FRET-based ER luminal Ca2+-sensing protein D1ER 48 h before single-cell FRET imaging. Expression of the RyR2 WT and mutants was induced 24 h before imaging. The cells were perfused with KRH buffer containing increasing levels of extracellular Ca2+ (0–2 mM) to induce SOICR. This was followed by the addition of 2 mM tetracaine to inhibit SOICR and then 20 mM caffeine to deplete the ER Ca2+ stores. Representative FRET recordings from RyR2 WT (A), P4920S (B), P4902L (C), E4950K (D), and G4955E (E) are shown. To minimize the influence of cyan fluorescent protein/yellow fluorescent protein cross talk, relative FRET measurements were used to calculate the activation threshold (F) and termination threshold (G) using the equations shown in A. FSOICR indicates the FRET level at which SOICR occurs, whereas Ftermi represents the FRET level at which SOICR terminates. The fractional Ca2+ release (H) was calculated by subtracting the termination threshold from the activation threshold. The maximum FRET signal Fmax is defined as the FRET level after tetracaine treatment. The minimum FRET signal Fmin is defined as the FRET level after caffeine treatment. The store capacity (I) was calculated by subtracting Fmin from Fmax. Data shown are mean ± SD from six to seven separate experiments (WT, 89 cells; P4902S, 139 cells; P4902L, 128 cells; E4950K, 79 cells; and G4955E, 75 cells). ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗p < 0.05 versus WT. NS, not significant (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 38.3 and p < 0.0001 for the activation threshold (F); F = 17.9 and p < 0.0001 for the termination threshold (G); F = 29.4 and p < 0.0001 for the fractional Ca2+ release (H); F = 6.1 and p = 0.0011 for the store capacity (I)). CTD, C-terminal domain; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; KRH, Krebs–Ringer–Hepes; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor; SOICR, store overload–induced spontaneous Ca2+ release.

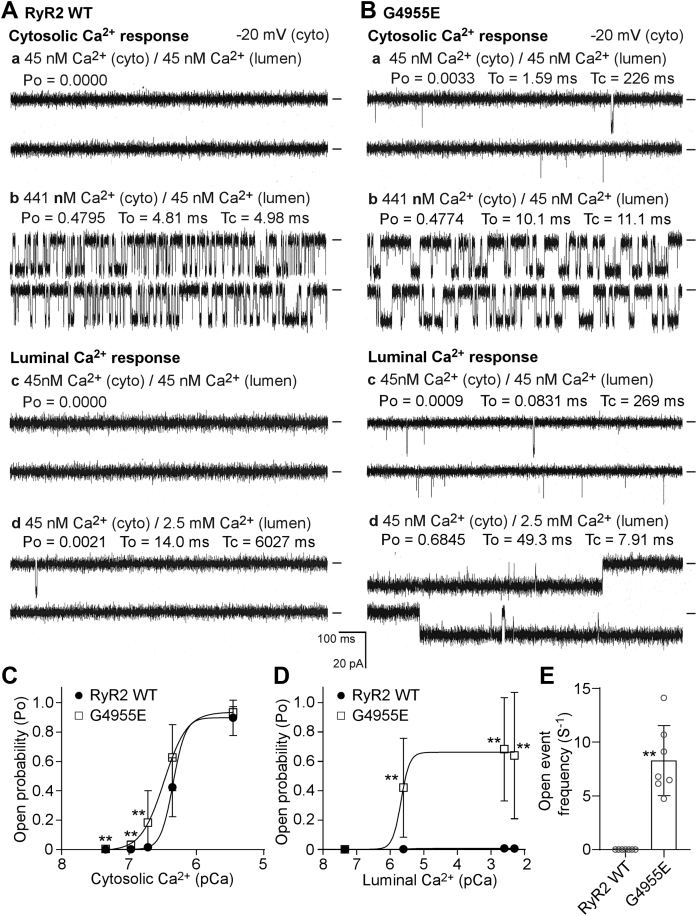

The G4955E mutation dramatically increases luminal Ca2+ activation of single RyR2 channels

Among the four disease-associated CTD mutations characterized, G4955E is the most severe, displaying the highest basal activity and the lowest EC50 for Ca2+ activation. To further understand the mechanism of action of this mutation, we performed single-channel recordings in planar lipid bilayers. Single RyR2 WT or G4955E mutant channels were incorporated into lipid bilayers. To study the response of the channel to cytosolic Ca2+ activation, we kept the luminal Ca2+ concentration constant at 45 nM and increased the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration stepwise from 45 nM to 3.5 μM. As shown in Figure 5, A and C, single G4955E mutant channels were activated by cytosolic Ca2+ at lower concentrations compared with single RyR2 WT channels. As a result, the G4955E mutation slightly shifted the cytosolic Ca2+ response curve of RyR2 to the left, especially at low cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations. To study the response of the channel to luminal Ca2+ activation, we kept the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration constant at 45 nM and increased the luminal Ca2+ concentration stepwise from 45 nM to 5.0 mM. As shown in Figure 5, B and D, single RyR2 WT channels were hardly activated by luminal Ca2+ under these recording conditions (i.e., in the absence of ATP or caffeine). In sharp contrast, single G4955E mutant channels were dramatically activated by luminal Ca2+ as low as 2.5 μM under the same conditions. Notably, single G4955E mutant channels, but not RyR2 WT channels, exhibited spontaneous opening events (8.29 events/s compared with 0 event/s in WT) even in the near absence of cytosolic and luminal Ca2+ (45 nM), which is consistent with the markedly increased basal activity of [3H]ryanodine binding in the near absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 2, B and D). Therefore, these single-channel analyses indicate that the G4955E mutation destabilizes the closed state of the channel and dramatically increases the activation of the RyR2 channel by luminal Ca2+.

Figure 5.

The G4955E mutation markedly increases the channel sensitivity to luminal Ca2+activation. Recombinant RyR2 WT and G4955E mutant channels were partially purified from cell lysate prepared from HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the RyR2 WT or G4955E mutant complementary DNA. Single-channel activities were recorded in a symmetrical recording solution containing 250 mM KCl and 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.4). Representative current traces of single RyR2 WT (A) and G4955E (B) channels in the presence of different cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and 45 nM luminal Ca2+ (panels a and b) and in the presence of 45 nM cytosolic Ca2+ and different luminal Ca2+ concentrations (panels c and d). The open probability of RyR2 WT or G4955E channels activated by various fixed cytosolic Ca2+ (C) or fixed luminal Ca2+ concentrations (D). The frequency of open events of single RyR2 WT or G4955E mutant channels in the presence of 45 nM cytosolic and 45 nM luminal Ca2+ concentration (E). Data shown are mean ± SD from seven RyR2 WT and seven G4955E single channels. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus WT. HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor.

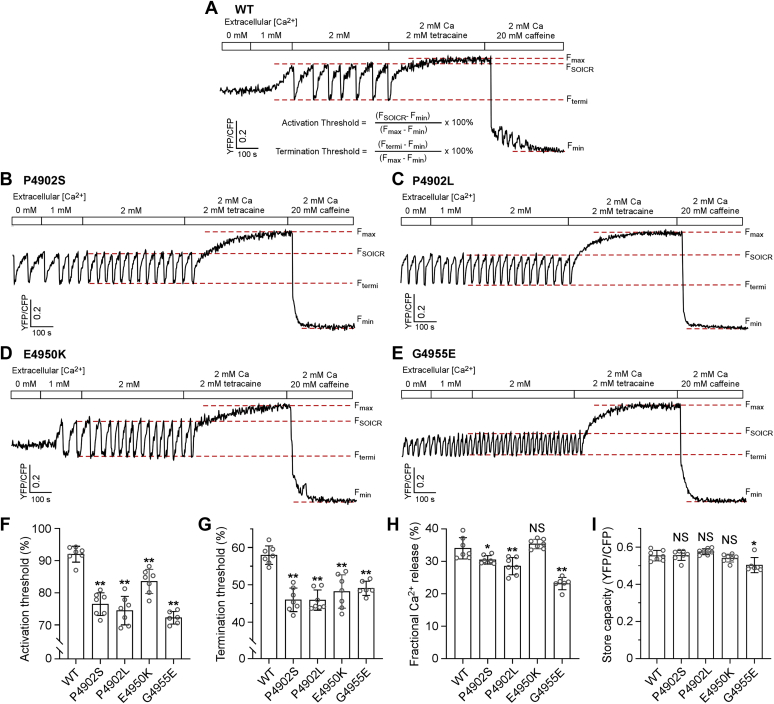

Probing the role of electrostatic interactions at the CTD intersubunit interface

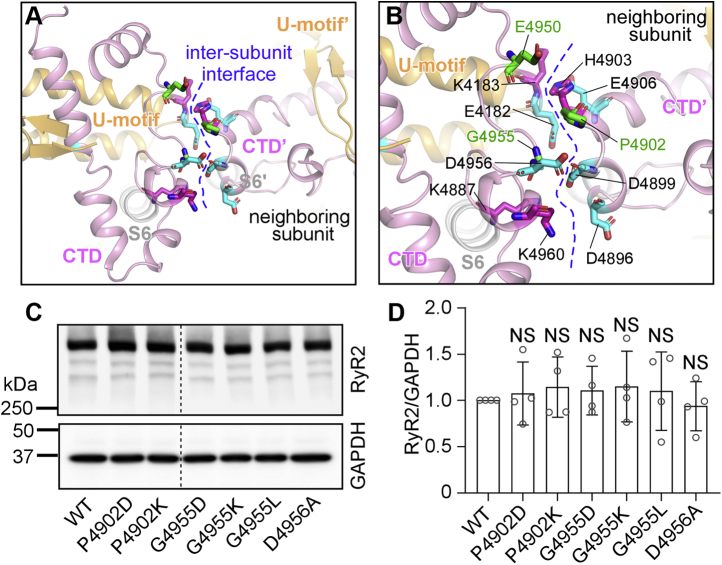

The CTD is clamped by the U-motif from the central domain to form a rigid structural unit that moves together during channel opening and closing (25) (Fig. 6A). There are multiple negatively and positively charged residues located at the intersubunit interface between adjacent CTD/U-motif units (Fig. 6B). These include E4182, K4183, K4887, E4950, D4956, and K4960 from one CTD/U-motif unit and D4896, D4899, H4903, and E4906 from the neighboring CTD/U-motif unit (Fig. 6B). This distribution of charged residues suggests that electrostatic interactions may be involved at the intersubunit interface. Interestingly, the disease-associated mutation G4955E introduces a negative charge near a pocket of negatively charged residues (E4182, D4899, and D4956), whereas the disease-associated mutation E4950K introduces a positive charge near the positively charged residues K4183 and H4903 (Fig. 6B). Thus, these mutations may result in some electrostatic repulsion that would destabilize the closed state and increase channel activation. To further probe the actions of CTD disease mutations, we substituted disease-associated residues G4955 and P4902 with a negatively charged residue aspartate (D) or a positively charged residue lysine (K), respectively, to generate mutations, G4955D, G4955K, P4902D, and P4902K (Fig. 6, C and D). We also substituted residue G4955 with a hydrophobic residue leucine (i.e., G4955L). We also generated the D4956A mutation to assess the role of this negatively charged residue (D4956) next to residue G4955 in channel function. Western blot analysis showed that the protein expression level of each of these mutants was compatible to that of the RyR2 WT (Fig. 6, C and D).

Figure 6.

Mutational analyses of the CTD intersubunit interface.A, 3D structure of the U-motif, S6 helix, CTD, and its neighboring U-motif and CTD. B, disease-affected residues (P4902, E4950, and G4955 in green) and negatively and positively charged residues at the CTD intersubunit interface. C, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the RyR2 WT or CTD mutant complementary DNAs. Immunoblotting of RyR2 WT and mutants from the same amount of transfected cell lysates. Note that the RyR2 band with an expected molecular weight of 565 kDa is located inside the separating gel. D, the expression levels of the WT and mutants were normalized to that of GAPDH (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 0.2461, p = 0.9556). Data shown are mean ± SD from four independent experiments. CTD, C-terminal domain; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; NS, not significant; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor.

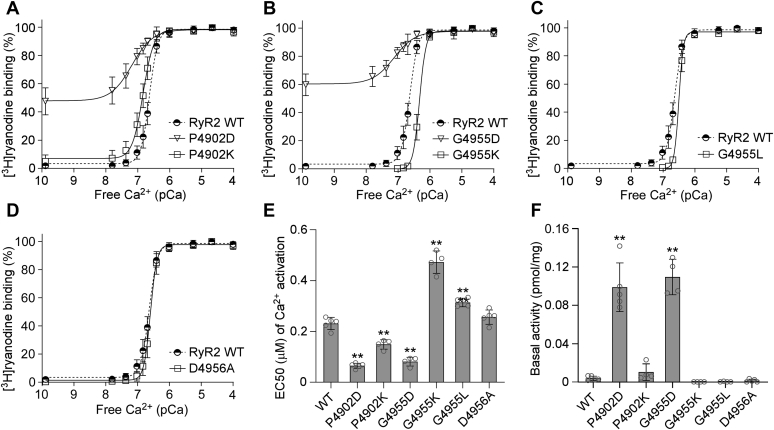

We next determined the impact of each of these mutations on Ca2+-dependent [3H]ryanodine binding. As shown in Figure 7 and Fig. S1, [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 WT was activated by ~100 nM Ca2+ and was fully activated by 1 to 2 μM Ca2+ with an EC50 of 0.23 μM. Very little [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 WT was detected in the near absence of Ca2+ (~0.1 nM), indicating that there was little or no Ca2+-independent basal activity of RyR2 WT (Fig. 7A). However, substitution of G4955 with a negatively charged residue (i.e., G4955D) markedly increased the Ca2+-independent basal activity and Ca2+-dependent activation of RyR2 (Fig. 7, B, E, and F). These effects of the G4955D mutation on [3H]ryanodine binding are similar to those of the disease mutation G4955E. In contrast, the G4955K and G4955L mutations suppressed the Ca2+-dependent activation of [3H]ryanodine binding and diminished Ca2+-independent basal activity (Fig. 7, B, C, E, and F). Similarly, the P4902D mutation, but not the P4902K mutation, markedly increased the Ca2+-independent basal activity and Ca2+-dependent activation of RyR2 (Fig. 7, A, E, and F). Furthermore, the D4956A mutation had no significant effect on either the basal activity or Ca2+ activation of [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 (Fig. 7, D–F).

Figure 7.

Effects of CTD mutations on [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2. [3H]ryanodine binding to cell lysate prepared from HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the RyR2 WT or CTD mutant complementary DNAs was carried out at various Ca2+ concentrations (0.1 nM–0.1 mM). The amounts of [3H]ryanodine binding at various Ca2+ concentrations were normalized to the maximal binding (100%). [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 WT, P4902D, P4902K (A), to RyR2 WT, G4955D, G4955K (B), to RyR2 WT, G4955L (C), or to RyR2 WT and D4956A (D). EC50 values of Ca2+ activation (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 142.7, p < 0.0001) (E) and basal activity (in the near absence of Ca2+, ~0.1 nM) (F) of [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 71.9, p < 0.0001). Data shown are mean ± SD from four to five separate experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus WT. CTD, C-terminal domain; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; RyR2, cardiac ryanodine receptor.

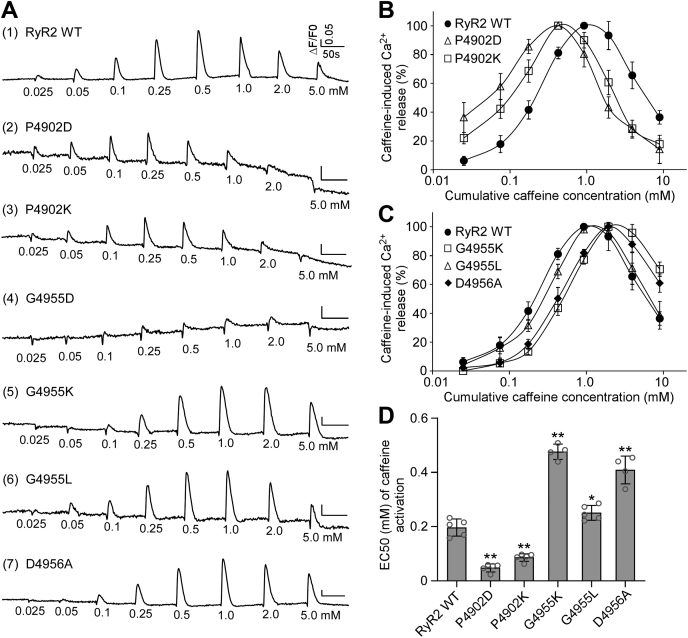

We also determined the impact of each of these CTD mutations on caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells. As shown in Figure 8, G4955K and G4955L mutations suppressed caffeine activation, shifting the caffeine response curve to the right (Fig. 8, A, C, and D). On the other hand, both the P4902D and P4902K mutations enhanced caffeine activation, shifting the caffeine response curve to the left (Fig. 8, A, B, and D). Although D4956A mutation had no significant effect on the Ca2+ activation or basal activity of [3H]ryanodine binding to RyR2 (Fig. 7, D–F), it markedly suppressed caffeine activation, shifting the caffeine response curve to the right (Fig. 8, A, C, and D). Note that the amplitudes of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells expressing the G4955D mutation were too small to accurately estimate its EC50 of caffeine activation. These data suggest that electrical charges at the CTD intersubunit interface are an important determinant of closed-state stability.

Figure 8.

Effects of CTD mutations on caffeine activation of RyR2.A, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with RyR2 WT or mutant complementary DNAs. The fluorescence intensity of the Fluo-3-loaded transfected cells was monitored continuously before and after each caffeine addition. The relationships between caffeine-induced Ca2+ release and cumulative caffeine concentrations in HEK293 cells transfected with RyR2 WT, P4902D, or P4902K (B), with RyR2 WT, G4955K, G4955L, or G4956A (C). D, the apparent EC50 values of caffeine-induced Ca2+ releases in HEK293 cells transfected with RyR2 WT or mutants (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test, F = 149.7, p < 0.0001). Note that the data for RyR2 WT shown here are the same as those shown for Figure 3 as the caffeine response of all mutants shown in these figures was characterized together. Data shown are mean ± SD from four to five separate experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗p < 0.05 versus WT. CTD, C-terminal domain; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; RyR2, cardiac cardiac ryanodine receptor.

Discussion

The RyR2 channel gate is formed by four S6 inner pore helices. The CTD, which is located at the C-terminal end of S6, controls the movement of S6 and thus the opening and closing of the channel gate. The CTD also acts as a joint connecting the central domain to the channel gate by interacting with the U-motif in the central domain, thus allowing the transmission of conformational changes in the central domain to the channel gate (25, 37). Therefore, the CTD is believed to play a critical role in channel gating. Consistent with this view, the CTD is a mutation hot spot, containing 14 known disease-associated mutations. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the actions of these CTD disease mutations are not well understood.

Previous studies have shown that CPVT-causing RyR2 mutations increase the basal activity and sensitivity to cytosolic and/or luminal activation of the RyR2 channel (11). This RyR2 hyperactivity is believed to cause CPVT by increasing the propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ release (Ca2+ waves) during SR Ca2+ overload as a result of emotional and physical stress. These Ca2+ waves can in turn provoke delayed afterdepolarizations and triggered activities, leading to CPVT. In the present study, we assessed the impact of four disease-associated CTD mutations (P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E). We found that all these four mutations reduced the activation threshold for SOICR (i.e., the SOICR activation threshold). We also found that these mutations increased the sensitivity of RyR2 to caffeine activation. We have previously shown that caffeine induces Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells by reducing the threshold for SOICR activation (59). Thus, both the D1ER luminal Ca2+ imaging analysis and caffeine-induced Ca2+ release assay revealed that these four disease-associated CTD mutations reduced the threshold for SOICR activation. By reducing the SOICR activation threshold, these mutations would decrease the level of the attainable store Ca2+ content and increase the propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ release during store Ca2+ overload. Thus, as with other CPVT RyR2 mutations, these four CTD mutations may increase the susceptibility to CPVT by enhancing the propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ release, delayed afterdepolarizations, and triggered activities under conditions of SR Ca2+ overload (e.g., during emotional and physical stress).

Notably, among the four disease-associated CTD mutations we have characterized, the G4955E mutation displays the highest basal activity and sensitivity to activation by Ca2+ and caffeine. Consistent with its severe impact on RyR2 channel function, the G4955E mutation was associated with severe atrial arrhythmias and neurological disorders such as seizure and intellectual disability in addition to CPVT (45). Thus, our data demonstrate a critical role of CTD in channel stability and gating and the pathogenesis of cardiac and neurological disorders.

3D structural analysis reveals that, among the 14 known disease-associated RyR2 CTD mutations, namely N4895D (51), P4902L (50), P4902S (49), G4904D (43), F4905L (46), L4919S (47), G4935R (16), Q4936K (44), S4938F (41), Y4939F (42), E4950K (51), G4955E (45), R4959Q (50), and Y4962C (48), many are located at the interfaces between CTD and other domains. For instance, the L4919S mutation is located at the interface between CTD and U-motif. G4935R, Q4936K, S4938F, and Y4939F are at the interface among CTD, the Ca2+-binding site, and the U-motif. The Y4962C mutation is at the interface between CTD and the central domain. Notably, in the tetrameric RyR2 structure, the CTD of one RyR2 subunit interacts with the CTD of the neighboring subunit, forming the CTD–CTD intersubunit interface (25). Interestingly, the P4902S, P4902L, E4950K, and G4955E mutations are located at this CTD tetrameric intersubunit interface. Hence, domain–domain interfaces are a common target of disease-associated RyR2 CTD mutations, as with disease mutations located in other RyR2 domains (63).

The role of the CTD intersubunit interface in channel function is unclear but is probably involved in stabilizing the closed state of the channel. In line with this view, we found that mutating residue G4955 to a negatively charged residue aspartic acid (D) or glutamic acid (E) markedly enhanced the basal channel activity. In contrast, mutating this G4955 residue to a positively charged residue lysine (K) suppressed channel activity. Similarly, substituting P4902 with a negatively charged residue aspartic acid (D), but not with a positively charged residue lysine (K), also dramatically increased the basal channel activity. These results suggest that electrostatic interactions are involved in the CTD–CTD intersubunit interactions that are important for stabilizing the closed state of the channel. Thus, mutations that impair CTD–CTD intersubunit interactions would destabilize the closed state, leading to spontaneous channel openings as detected in single-channel recordings in the near absence of Ca2+.

Most of the disease-associated RyR2 CTD mutations are associated with CPVT and sudden cardiac death. Interestingly, in addition to cardiac phenotypes, the CTD G4955E mutation is also associated with neuronal phenotypes, including delayed development, intellectual disability, attention deficit, hyperactivity, and seizure (45). Similarly, previous studies have also linked RyR2 mutations to intellectual disability (13) and seizures (64, 65, 66). However, the mechanism by which RyR2 mutations cause neuronal phenotypes is not completely understood. In addition to the heart, RyR2 is also abundantly expressed in the brain, especially in the hippocampus and cortex. Since RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release plays a crucial role in regulating membrane excitability and basal activity of different cells (9, 67, 68, 69, 70), altered RyR2 function may affect neuronal excitability. Consistent with this view, we have recently shown that suppressing the activity of RyR2 by reducing the open time of the channel prevented neuronal hyperexcitability and hyperactivity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in a mouse model (5xFAD) of Alzheimer's disease (9). Thus, it is possible that increased RyR2 activity may enhance neuronal excitability. The markedly augmented channel activity of the G4955E mutation may cause intellectual disability, attention deficit, hyperactivity, and seizure by altering neuronal excitability. Further studies will be needed to directly determine the effect of G4955E on neuronal function.

Study limitations

In our caffeine-induced Ca2+ release assay, we transiently transfected HEK293 cells with RyR2 WT and mutant complementary DNAs (cDNAs). We then harvested the transfected HEK293 cells and loaded the cells with fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-3 AM for measuring intracellular Ca2+ levels before and after additions of different concentrations of caffeine. We found that the levels of the Fluo-3 fluorescence signals in RyR2 WT or mutant transfected cells varied substantially from experiments to experiments even with the same batch of HEK293 cells or cDNAs, probably because of differences in the transfection efficiency, expression level, numbers of vital cells after harvesting, level of Fluo-3 Ca2+ dye loading to the cells, and so on. Because of these variabilities, we cannot compare the absolute values of the Fluo-3 fluorescence signals in RyR2 WT and mutant expressing HEK293 cells. As such, our caffeine-induced Ca2+ release assay was not designed to compare the absolute amplitudes of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release between RyR2 WT and mutants. Instead, we used this assay to assess the impact of disease-associated RyR2 mutations on the sensitivity (EC50) of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release, which is highly consistent from experiments to experiments. We have used this caffeine-induced Ca2+ release assay to characterize a large number of disease-associated RyR2 mutations and revealed that altered sensitivity to caffeine activation is a common defect of disease-associated RyR2 mutations (13, 40, 71, 72).

In summary, our present study shows that disease-associated RyR2 mutations located at the CTD tetrameric subunit interface increased basal channel activity and Ca2+/caffeine activation of RyR2. Electrostatic interactions are importantly involved in stabilizing the CTD tetrameric subunit interfaces. Disease mutations may disrupt these intersubunit interfaces and destabilize the closed state of the channel. Our work provides important new insights into the role of CTD in channel gating and stability and the pathogenic mechanism of CTD disease mutations.

Experimental procedures

Materials

[3H]ryanodine was purchased from PerkinElmer. Ryanodine was purchased from Abcam. Caffeine was obtained from Sigma.

Generation of RyR2 mutations

The RyR2 CTD mutations, P4902D, P4902K, P4902S, P4902L, G4955D, G4955E, G4955K, G4955L, and D4956A, were generated by the overlap extension method using PCR (73, 74). Briefly, the NruI–NotI (in the vector) fragment containing the mutation was obtained by overlapping PCR and used to replace the corresponding WT fragment in the full-length mouse RyR2 cDNA in pcDNA5. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Generation of stable and inducible cell lines expressing RyR2 WT and mutants

Stable and inducible HEK293 cell lines expressing RyR2 WT and mutants were generated using the Flp-In T-REx Core Kit from Invitrogen. Briefly, Flp-In T-REx HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the inducible expression vector pcDNA5/Flp Recombination Target/TO containing the WT or mutant RyR2 cDNA and the pOG44 vector encoding the Flp recombinase in 1:5 ratios using the Ca2+ phosphate precipitation method. The transfected cells were washed with PBS 24 h after transfection, followed by a change into fresh medium for 24 h. The cells were then washed again with PBS, harvested, and plated onto new dishes. After the cells had attached, the growth medium was replaced with a selection medium containing 200 μg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen). The selection medium was changed every 3 to 4 days until the desired number of cells was grown. The hygromycin-resistant cells were pooled, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. These positive cells are believed to be isogenic because the integration of RyR2 cDNA is mediated by the Flp recombinase at a single Flp Recombination Target site.

Preparation of HEK293 cell lysates

HEK293 cells were transfected with RyR2 WT or CTD mutant cDNAs using the calcium phosphate precipitation method as described previously (74, 75). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and resuspended in the lysis buffer containing 25 mM Tris, 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 137 mM NaCl, 1% CHAPS, 0.5% egg phosphatidylcholine, 2.5 mM DTT, and a protease inhibitor mix (1 mM benzamidine, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.5 mM PMSF) on ice for 60 min. Cell lysates were obtained after removing insolubilized materials by centrifugation.

[3H]Ryanodine-binding assay

Equilibrium [3H]ryanodine binding to cell lysates was performed as described previously (74, 75) with some modifications. Cell lysates were incubated with 5 nM [3H]ryanodine at 37 °C for 2 h in 300 μl of a binding solution containing 500 mM KCl, 25 mM Tris, and 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.4). Free [Ca2+] was adjusted by EGTA and CaCl2 solutions using the computer program of Fabiato and Fabiato (76). Free [Mg2+] was adjusted by EGTA and MgCl2 solutions according to the Maxchelator program. At the completion of incubation, samples were diluted with 5 ml of ice-cold washing buffer containing 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 250 mM KCl and filtered through Whatman GF/B filters presoaked with 1% polyethylenimine. Filters were washed immediately with 2 × 5 ml of the same buffer. The amount of [3H]ryanodine retained in filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Specifically bound [3H]ryanodine was calculated by subtracting nonspecific binding that was determined in the presence of 50 μM-unlabeled ryanodine. All binding assays were performed in duplicate. [3H]ryanodine-binding data were fitted with the Hill equation using the Prism 8 (GraphPad Software), from which EC50 values for Ca2+ activation were calculated.

Western blotting

The RyR2 WT and mutant proteins collected from transfected HEK293 cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE (5% gel) (77) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes at 100 V for 2 h at 4 °C in the presence of 0.01% SDS (78). The nitrocellulose membranes containing the transferred proteins were blocked for 60 min with 5% nonfat milk. The blocked membrane was incubated with anti-RyR2 antibody (Alomone Labs; ARR-002, 1:2000 dilution) and then incubated with secondary antimouse IgG (heavy and light) antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:20,000 dilution). After washing for 10 min three times, the bound antibodies were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit from Thermo. The intensity of each band was determined from its intensity profile obtained by ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare/Life Sciences). Note that we always use nonsaturated gel images for determining the band intensities for all our immunoblots. We loaded the same amount of RyR2 WT and mutant proteins onto one gel and normalized the intensity of each band to that of GAPDH.

Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells

The free cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in transfected HEK293 cells was measured using the fluorescence Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-3 AM (Molecular Probes). HEK293 cells grown on 100-mm tissue culture dishes for 18 to 20 h after subculture were transfected with RyR2 WT or mutant cDNAs. Cells grown for 18 to 20 h after transfection were washed four times with PBS and incubated in Krebs–Ringer–Hepes (KRH), 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 6 mM glucose, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM Hepes, and pH 7.4 buffer without MgCl2 and CaCl2 at room temperature for 40 min and at 37 °C for 40 min. After being detached from culture dishes by pipetting, cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 2 min in a Beckman TH-4 rotor. Cell pellets were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-3 AM in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium at room temperature for 30 min, followed by washing with KRH buffer plus 2 mM CaCl2 and 1.2 mM MgCl2 (KRH+ buffer) three times and resuspended in 150 μl KRH+ buffer plus 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin and 250 μM sulfinpyrazone. The Fluo-3 AM-loaded cells were added to 2 ml (final volume) KRH+ buffer in a cuvette. The fluorescence intensity of Fluo-3 AM at 530 nm was measured before and after repeated cumulative additions of various concentrations of caffeine (0.025–5 mM) in an SLM-Aminco series 2 luminescence spectrometer with 480 nm excitation at 25 °C (SLM Instruments). The peak levels of each caffeine-induced Ca2+ release was determined and normalized to the highest level (100%) of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release for each experiment. The normalized data of the ascending part of the caffeine dose response curve were fitted with the Hill equation to calculate the apparent EC50 value of caffeine activation for each construct using the curve-fitting module of Prism 8 (GraphPad Software).

Single-cell luminal Ca2+ imaging

Luminal Ca2+ concentrations in HEK293 cells expressing RyR2 WT or the CTD mutants were measured using single-cell Ca2+ imaging and the FRET-based ER luminal Ca2+-sensitive chameleon protein D1ER as described previously (62, 79). The cells were grown to 95% confluence in a 75-cm2 flask, passaged with PBS, and plated in 100-mm–diameter tissue culture dishes at ~10% confluence 18 to 20 h before transfection with D1ER cDNA using the Ca2+ phosphate precipitation method. After transfection for 24 h, the growth medium was changed to an induction medium containing 1 μg/ml tetracycline. In intact cell studies, after induction for ~22 h, the cells were perfused continuously with KRH buffer containing various concentrations of CaCl2 (0, 1, and 2 mM) for inducing SOICR and tetracaine (2 mM) for estimating the store capacity or caffeine (20 mM) for estimating the minimum store amplitude by depleting the ER Ca2+ stores at room temperature (23 °C). Images were captured with Compix Simple PCI 6 software every 2 s using an inverted microscope (Nikon TE2000-S) equipped with an S-Fluor ×20/0.75 objective. The filters used for D1ER imaging were λexcitation of 436 ± 20 nm for cyan fluorescent protein and λexcitation of 500 ± 20 nm for YFP and λemission of 465 ± 30 nm for cyan fluorescent protein and λemission of 535 ± 30 nm for YFP with a dichroic mirror (500 nm). The amount of FRET was determined from the ratio of the light emission at 535 and 465 nm.

Single-channel recordings

Recombinant RyR2 WT and G4955E mutant channels were purified from cell lysate prepared from HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the RyR2 WT or mutant cDNAs by sucrose density gradient centrifugation as described previously (74). Heart phosphatidylethanolamine (50%) and brain phosphatidylserine (50%) (Avanti Polar Lipids), dissolved in chloroform, were combined and dried under nitrogen gas and resuspended in 30 μl of n-decane at a concentration of 12 mg lipid per ml. Bilayers were formed across a 250 μm hole in a Delrin partition separating two chambers. The trans chamber (800 μl) was connected to the head stage input of an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments). The cis chamber (1.2 ml) was held at virtual ground. A symmetrical solution containing 250 mM KCl and 25 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 was used for all recordings, unless indicated otherwise. A 4-μl aliquot (~1 μg protein) of the sucrose density gradient–purified recombinant RyR2 WT or mutant channels was added to the cis chamber. Spontaneous channel activity was always tested for sensitivity to EGTA and Ca2+. The chamber to which the addition of EGTA inhibited the activity of the incorporated channel presumably corresponds to the cytosolic side of the Ca2+ release channel. The direction of single-channel currents was always measured from the luminal to the cytosolic side of the channel, unless mentioned otherwise. Recordings were filtered at 2500 Hz. Data analyses were carried out using the pclamp 8.1 software package (Axon Instruments). Free Ca2+ concentrations were calculated using the computer program of Fabiato and Fabiato.

Statistical analysis

All data shown are means ± SD as indicated. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test or Mann–Whitney test (two-tailed) was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 8, to assess the difference between mean values. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All data are contained within the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

W. G. is a recipient of the Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions Graduate Studentship Award; J. W. is a recipient of the Libin Cardiovascular Institute and Cumming School of Medicine Postdoctoral Fellowship Award; B. S. is a recipient of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada Junior Fellowship Award and the Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions Fellowship Award; and S. R. W. C. is the Heart and Stroke Foundation Chair in cardiovascular research. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

W. G., R. W., B. S., and S. R. W. C. conceptualization; W. G., J. W., J. P. E., L. Z., and R. W. data curation; W. G., L. Z., B. S., and S. R. W. C. formal analysis; W. G., B. S., and S. R. W. C. validation; W. G., B. S., and S. R. W. C. visualization; W. G., J. W., J. P. E., L. Z., B. S., and S. R. W. C. methodology; W. G., R. W., B. S., and S. R. W. C. writing-original draft; W. G., B. S., and S. R. W. C. writing-review and editing; J. P. E. and B. S. project administration; B. S. and S. R. W. C. supervision; B. S. and S. R. W. C. funding acquisition; B. S. and S. R. W. C. investigation; S. R. W. C. resources.

Funding and additional information

This work was supported by research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and Heart and Stroke Foundation Chair in Cardiovascular Research (to S. R. W. C.).

Edited by Roger Colbran

Contributor Information

Bo Sun, Email: sunbo1025@hotmail.com.

S. R. Wayne Chen, Email: swchen@ucalgary.ca.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Bers D.M. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fill M., Copello J.A. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:893–922. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bers D.M. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:23–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Petegem F. Ryanodine receptors: Structure and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:31624–31632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.349068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bers D.M. Cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak: Basis and roles in cardiac dysfunction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2014;76:107–127. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuichi T., Furutama D., Hakamata Y., Nakai J., Takeshima H., Mikoshiba K. Multiple types of ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels are differentially expressed in rabbit brain. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:4794–4805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04794.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannini G., Sorrentino V. Molecular structure and tissue distribution of ryanodine receptors calcium channels. Med. Res. Rev. 1995;15:313–323. doi: 10.1002/med.2610150405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murayama T., Ogawa Y. Properties of Ryr3 ryanodine receptor isoform in mammalian brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:5079–5084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao J., Sun B., Institoris A., Zhan X., Guo W., Song Z., Liu Y., Hiess F., Boyce A.K.J., Ni M., Wang R., Ter Keurs H., Back T.G., Fill M., Thompson R.J. Limiting RyR2 open time prevents Alzheimer's disease-related neuronal hyperactivity and memory loss but not beta-amyloid accumulation. Cell Rep. 2020;32:108169. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLennan D.H., Chen S.R. Store overload-induced Ca2+ release as a triggering mechanism for CPVT and MH episodes caused by mutations in RYR and CASQ genes. J. Physiol. 2009;587:3113–3115. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Priori S.G., Chen S.R. Inherited dysfunction of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ handling and arrhythmogenesis. Circ. Res. 2011;108:871–883. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denniss A., Dulhunty A.F., Beard N.A. Ryanodine receptor Ca(2+) release channel post-translational modification: Central player in cardiac and skeletal muscle disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018;101:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lieve K.V.V., Verhagen J.M.A., Wei J., Bos J.M., van der Werf C., Roses I.N.F., Mancini G.M.S., Guo W., Wang R., van den Heuvel F., Frohn-Mulder I.M.E., Shimizu W., Nogami A., Horigome H., Roberts J.D. Linking the heart and the brain: Neurodevelopmental disorders in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priori S.G., Napolitano C., Tiso N., Memmi M., Vignati G., Bloise R., Sorrentino V., Danieli G.A. Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (hRyR2) underlie catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2001;103:196–200. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Napolitano C., Priori S.G. Diagnosis and treatment of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:675–678. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medeiros-Domingo A., Bhuiyan Z.A., Tester D.J., Hofman N., Bikker H., van Tintelen J.P., Mannens M.M., Wilde A.A., Ackerman M.J. The RYR2-encoded ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel in patients diagnosed previously with either catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or genotype negative, exercise-induced long QT syndrome: A comprehensive open reading frame mutational analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:2065–2074. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lieve K.V., van der Werf C., Wilde A.A. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ. J. 2016;80:1285–1291. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiso N., Stephan D.A., Nava A., Bagattin A., Devaney J.M., Stanchi F., Larderet G., Brahmbhatt B., Brown K., Bauce B., Muriago M., Basso C., Thiene G., Danieli G.A., Rampazzo A. Identification of mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene in families affected with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy type 2 (ARVD2) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:189–194. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauce B., Rampazzo A., Basso C., Bagattin A., Daliento L., Tiso N., Turrini P., Thiene G., Danieli G.A., Nava A. Screening for ryanodine receptor type 2 mutations in families with effort-induced polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death: Early diagnosis of asymptomatic carriers. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002;40:341–349. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01946-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tester D.J., Spoon D.B., Valdivia H.H., Makielski J.C., Ackerman M.J. Targeted mutational analysis of the RyR2-encoded cardiac ryanodine receptor in sudden unexplained death: A molecular autopsy of 49 medical examiner/coroner's cases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2004;79:1380–1384. doi: 10.4065/79.11.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.d'Amati G., Bagattin A., Bauce B., Rampazzo A., Autore C., Basso C., King K., Romeo M.D., Gallo P., Thiene G., Danieli G.A., Nava A. Juvenile sudden death in a family with polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias caused by a novel RyR2 gene mutation: Evidence of specific morphological substrates. Hum. Pathol. 2005;36:761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishio H., Iwata M., Suzuki K. Postmortem molecular screening for cardiac ryanodine receptor type 2 mutations in sudden unexplained death: R420W mutated case with characteristics of status thymico-lymphatics. Circ. J. 2006;70:1402–1406. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noboru F., Hidekazu I., Kenshi H., Katsuharu U., Mitsuru N., Tetsuo K., Hiromasa K., Yuichiro S., Toshinari T., Kazuo O., Sumio M., Masakazu Y. A novel missense mutation in cardiac ryanodine receptor gene as a possible cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Evidence from familial analysis. Circulation. 2006;114:165. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarado F.J., Bos J.M., Yuchi Z., Valdivia C.R., Hernandez J.J., Zhao Y.T., Henderlong D.S., Chen Y., Booher T.R., Marcou C.A., Van Petegem F., Ackerman M.J., Valdivia H.H. Cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmia in mice induced by a mutation in ryanodine receptor 2. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng W., Shen H., Wu J., Guo W., Pan X., Wang R., Chen S.R., Yan N. Structural basis for the gating mechanism of the type 2 ryanodine receptor RyR2. Science. 2016;354:aah5324. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y., Sun B., Xiao Z., Wang R., Guo W., Zhang J.Z., Mi T., Wang Y., Jones P.P., Van Petegem F., Chen S.R. Roles of the NH2-terminal domains of cardiac ryanodine receptor in Ca2+ release activation and termination. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:7736–7746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.618827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhuiyan Z.A., van den Berg M.P., van Tintelen J.P., Bink-Boelkens M.T., Wiesfeld A.C., Alders M., Postma A.V., van Langen I., Mannens M.M., Wilde A.A. Expanding spectrum of human RYR2-related disease: New electrocardiographic, structural, and genetic features. Circulation. 2007;116:1569–1576. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marjamaa A., Laitinen-Forsblom P., Lahtinen A.M., Viitasalo M., Toivonen L., Kontula K., Swan H. Search for cardiac calcium cycling gene mutations in familial ventricular arrhythmias resembling catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. BMC Med. Genet. 2009;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szentpali Z., Szili-Torok T., Caliskan K. Primary electrical disorder or primary cardiomyopathy? A case with a unique association of noncompaction cardiomyopathy and cathecolaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia caused by ryanodine receptor mutation. Circulation. 2013;127:1165–1166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.144949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohno S., Omura M., Kawamura M., Kimura H., Itoh H., Makiyama T., Ushinohama H., Makita N., Horie M. Exon 3 deletion of RYR2 encoding cardiac ryanodine receptor is associated with left ventricular non-compaction. Europace. 2014;16:1646–1654. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell M.J., Czosek R.J., Hinton R.B., Miller E.M. Exon 3 deletion of ryanodine receptor causes left ventricular noncompaction, worsening catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and sudden cardiac arrest. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2015;167A:2197–2200. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dharmawan T., Nakajima T., Ohno S., Iizuka T., Tamura S., Kaneko Y., Horie M., Kurabayashi M. Identification of a novel exon3 deletion of RYR2 in a family with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2019;24 doi: 10.1111/anec.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohli U., Aziz Z., Beaser A.D., Nayak H.M. A large deletion in RYR2 exon 3 is associated with nadolol and flecainide refractory catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2019;42:1146–1154. doi: 10.1111/pace.13668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Y., Tian X., Wang R., Fill M., Chen S.W. Abnormal termination of Ca2+ release is a common defect of RyR2 mutations associated with cardiomyopathies. Circ. Res. 2012;110:968–977. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lobo P.A., Van Petegem F. Crystal structures of the N-terminal domains of cardiac and skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors: Insights into disease mutations. Structure. 2009;17:1505–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.des Georges A., Clarke O.B., Zalk R., Yuan Q., Condon K.J., Grassucci R.A., Hendrickson W.A., Marks A.R., Frank J. Structural basis for gating and activation of RyR1. Cell. 2016;167:145–157 e117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong D., Chi X., Wei J., Zhou G., Huang G., Zhang L., Wang R., Lei J., Chen S.R.W., Yan N. Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor 2 by calmodulin. Nature. 2019;572:347–351. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1377-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chi X., Gong D., Ren K., Zhou G., Huang G., Lei J., Zhou Q., Yan N. Molecular basis for allosteric regulation of the type 2 ryanodine receptor channel gating by key modulators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019;116:25575–25582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914451116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao Z., Guo W., Sun B., Hunt D.J., Wei J., Liu Y., Wang Y., Wang R., Jones P.P., Back T.G., Chen S.R.W. Enhanced cytosolic Ca2+ activation underlies a common defect of central domain cardiac ryanodine receptor mutations linked to arrhythmias. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:24528–24537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.756528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo W., Sun B., Estillore J.P., Wang R., Chen S.R.W. The central domain of cardiac ryanodine receptor governs channel activation, regulation, and stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:15622–15635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujii Y., Itoh H., Ohno S., Murayama T., Kurebayashi N., Aoki H., Blancard M., Nakagawa Y., Yamamoto S., Matsui Y., Ichikawa M., Sonoda K., Ozawa T., Ohkubo K., Watanabe I. A type 2 ryanodine receptor variant associated with reduced Ca(2+) release and short-coupled torsades de pointes ventricular arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hata Y., Kinoshita K., Mizumaki K., Yamaguchi Y., Hirono K., Ichida F., Takasaki A., Mori H., Nishida N. Postmortem genetic analysis of sudden unexplained death syndrome under 50 years of age: A next-generation sequencing study. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:1544–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fokstuen S., Makrythanasis P., Hammar E., Guipponi M., Ranza E., Varvagiannis K., Santoni F.A., Albarca-Aguilera M., Poleggi M.E., Couchepin F., Brockmann C., Mauron A., Hurst S.A., Moret C., Gehrig C. Experience of a multidisciplinary task force with exome sequencing for Mendelian disorders. Hum. Genomics. 2016;10:24. doi: 10.1186/s40246-016-0080-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohno S., Hasegawa K., Horie M. Gender differences in the inheritance mode of RYR2 mutations in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia patients. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamdan F.F., Srour M., Capo-Chichi J.M., Daoud H., Nassif C., Patry L., Massicotte C., Ambalavanan A., Spiegelman D., Diallo O., Henrion E., Dionne-Laporte A., Fougerat A., Pshezhetsky A.V., Venkateswaran S. De novo mutations in moderate or severe intellectual disability. PLoS Genet. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ware J.S., John S., Roberts A.M., Buchan R., Gong S., Peters N.S., Robinson D.O., Lucassen A., Behr E.R., Cook S.A. Next generation diagnostics in inherited arrhythmia syndromes : A comparison of two approaches. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2013;6:94–103. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9401-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawamura M., Ohno S., Naiki N., Nagaoka I., Dochi K., Wang Q., Hasegawa K., Kimura H., Miyamoto A., Mizusawa Y., Itoh H., Makiyama T., Sumitomo N., Ushinohama H., Oyama K. Genetic background of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in Japan. Circ. J. 2013;77:1705–1713. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Werf C., Nederend I., Hofman N., van Geloven N., Ebink C., Frohn-Mulder I.M., Alings A.M.W., Bosker H.A., Bracke F.A., van den Heuvel F., Waalewijn R.A., Bikker H., Peter van Tintelen J., Bhuiyan Z.A., van den Berg M.P. Familial evaluation in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: Disease penetrance and expression in cardiac ryanodine receptor mutation–carrying relatives. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2012;5:748–756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.970517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Postma A.V., Denjoy I., Kamblock J., Alders M., Lupoglazoff J.M., Vaksmann G., Dubosq-Bidot L., Sebillon P., Mannens M.M., Guicheney P., Wilde A.A. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: RYR2 mutations, bradycardia, and follow up of the patients. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:863–870. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laitinen P.J., Swan H., Kontula K. Molecular genetics of exercise-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: Identification of three novel cardiac ryanodine receptor mutations and two common calsequestrin 2 amino-acid polymorphisms. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;11:888–891. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Priori S.G., Napolitano C., Memmi M., Colombi B., Drago F., Gasparini M., DeSimone L., Coltorti F., Bloise R., Keegan R., Cruz Filho F.E., Vignati G., Benatar A., DeLogu A. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002;106:69–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020013.73106.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang D., Xiao B., Zhang L., Chen S.R. Enhanced basal activity of a cardiac Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) mutant associated with ventricular tachycardia and sudden death. Circ. Res. 2002;91:218–225. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000028455.36940.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas N.L., George C.H., Lai F.A. Functional heterogeneity of ryanodine receptor mutations associated with sudden cardiac death. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;64:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inui M., Saito A., Fleischer S. Isolation of the ryanodine receptor from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum and identity with the feet structures. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:15637–15642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du G.G., MacLennan D.H. Functional consequences of mutations of conserved, polar amino acids in transmembrane sequences of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) of rabbit skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:31867–31872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen S.R., Li P., Zhao M., Li X., Zhang L. Role of the proposed pore-forming segment of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) in ryanodine interaction. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2436–2447. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75587-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang R., Zhang L., Bolstad J., Diao N., Brown C., Ruest L., Welch W., Williams A.J., Chen S.R.W. Residue Gln4863 within a predicted transmembrane sequence of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) is critical for ryanodine interaction. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:51557–51565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rousseau E., Meissner G. Single cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel: Activation by caffeine. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;256:H328–333. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.2.H328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kong H., Jones P.P., Koop A., Zhang L., Duff H.J., Chen S.R. Caffeine induces Ca2+ release by reducing the threshold for luminal Ca2+ activation of the ryanodine receptor. Biochem. J. 2008;414:441–452. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang D., Xiao B., Yang D., Wang R., Choi P., Zhang L., Cheng H., Chen S.R. RyR2 mutations linked to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death reduce the threshold for store-overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:13062–13067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402388101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang D., Wang R., Xiao B., Kong H., Hunt D.J., Choi P., Zhang L., Chen S.W. Enhanced store overload–induced Ca2+ release and channel sensitivity to luminal Ca2+ activation are common defects of RyR2 mutations linked to ventricular tachycardia and sudden death. Circ. Res. 2005;97:1173–1181. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000192146.85173.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones P.P., Jiang D., Bolstad J., Hunt D.J., Zhang L., Demaurex N., Chen S.R. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ measurements reveal that the cardiac ryanodine receptor mutations linked to cardiac arrhythmia and sudden death alter the threshold for store-overload-induced Ca2+ release. Biochem. J. 2008;412:171–178. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kimlicka L., Lau K., Tung C.C., Van Petegem F. Disease mutations in the ryanodine receptor N-terminal region couple to a mobile intersubunit interface. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1506. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lehnart S.E., Mongillo M., Bellinger A., Lindegger N., Chen B.X., Hsueh W., Reiken S., Wronska A., Drew L.J., Ward C.W., Lederer W.J., Kass R.S., Morley G., Marks A.R. Leaky Ca2+ release channel/ryanodine receptor 2 causes seizures and sudden cardiac death in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2230–2245. doi: 10.1172/JCI35346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aiba I., Wehrens X.H., Noebels J.L. Leaky RyR2 channels unleash a brainstem spreading depolarization mechanism of sudden cardiac death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:E4895–4903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605216113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yap S.M., Smyth S. Ryanodine receptor 2 (RYR2) mutation: A potentially novel neurocardiac calcium channelopathy manifesting as primary generalised epilepsy. Seizure. 2019;67:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nelson M.T., Cheng H., Rubart M., Santana L.F., Bonev A.D., Knot H.J., Lederer W.J. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bogdanov K.Y., Vinogradova T.M., Lakatta E.G. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger: Molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ. Res. 2001;88:1254–1258. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mandikian D., Bocksteins E., Parajuli L.K., Bishop H.I., Cerda O., Shigemoto R., Trimmer J.S. Cell type-specific spatial and functional coupling between mammalian brain Kv2.1 K+ channels and ryanodine receptors. J. Comp. Neurol. 2014;522:3555–3574. doi: 10.1002/cne.23641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alkon D.L., Nelson T.J., Zhao W., Cavallaro S. Time domains of neuronal Ca2+ signaling and associative memory: Steps through a calexcitin, ryanodine receptor, K+ channel cascade. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:529–537. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun B., Yao J., Ni M., Wei J., Zhong X., Guo W., Zhang L., Wang R., Belke D., Chen Y.X., Lieve K.V.V., Broendberg A.K., Roston T.M., Blankoff I., Kammeraad J.A. Cardiac ryanodine receptor calcium release deficiency syndrome. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aba7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roston T.M., Guo W., Krahn A.D., Wang R., Van Petegem F., Sanatani S., Chen S.R., Lehman A. A novel RYR2 loss-of-function mutation (I4855M) is associated with left ventricular non-compaction and atypical catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J. Electrocardiol. 2017;50:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ho S.N., Hunt H.D., Horton R.M., Pullen J.K., Pease L.R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction [see comments] Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li P., Chen S.R. Molecular basis of Ca(2)+ activation of the mouse cardiac Ca(2)+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) J. Gen. Physiol. 2001;118:33–44. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guo W., Sun B., Xiao Z., Liu Y., Wang Y., Zhang L., Wang R., Chen S.R. The EF-hand Ca2+ binding domain is not required for cytosolic Ca2+ activation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:2150–2160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.693325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Calculator programs for computing the composition of the solutions containing multiple metals and ligands used for experiments in skinned muscle cells. J. Physiol. (Paris) 1979;75:463–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: Procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1979;76:4350–4434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Palmer A.E., Jin C., Reed J.C., Tsien R.Y. Bcl-2-mediated alterations in endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ analyzed with an improved genetically encoded fluorescent sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:17404–17409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.