To the editor:

We read with interest the recent reports of gross hematuria occurring in 4 patients with IgA nephropathy shortly following the second dose of mRNA vaccine for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1, 2, 3 These include 2 cases following the Moderna vaccine1 and 2 following the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine.2 , 3 As only 1 of these patients had a postvaccination biopsy performed,3 we report the biopsy findings in 2 additional patients who underwent their first kidney biopsy due to the development of gross hematuria shortly following the second dose of the Moderna vaccine for COVID-19.

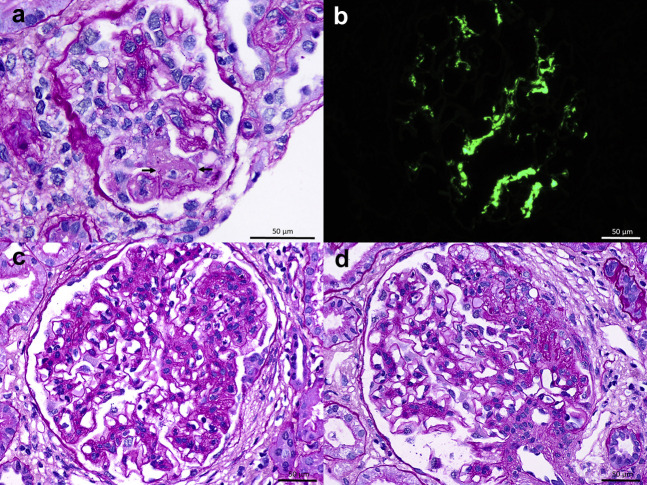

A 50-year-old White woman with hypertension since age 18 years, obesity, and anti–phospholipid syndrome presented with gross hematuria 2 days after the second dose of the Moderna vaccine for COVID-19, accompanied by low-grade fever and generalized body aches. After the first dose, the patient had experienced only generalized weakness and decreased appetite for several days. Medications included amlodipine, furosemide, and olmesartan, with the more recent addition of warfarin and enoxaparin 3 months prior to presentation. There was no past history of gross hematuria. Laboratory evaluation revealed a serum creatinine of 1.7 mg/dl and a urine protein-creatinine ratio of 2 g/g (increased from baseline values of 1.3 mg/dl and 1.3 g/g, respectively, 7 months prior to presentation). Urinalysis demonstrated >50 red blood cells per high-power field (increased from baseline 10–20 red blood cells 7 months prior to presentation). Serologies included negative or normal anti-nuclear antibody, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibody, PLA2R antibody, C3, and C4. The biopsy, performed 19 days after the onset of macrohematuria, demonstrated IgA nephropathy (Figure 1 a and b). Among 12 glomeruli sampled, 3 were globally sclerotic and 1 contained a segmental scar. The remainder had mild diffuse mesangial hypercellularity, and 1 glomerulus displayed active segmental fibrinoid necrosis with mild leukocyte infiltration, rupture of glomerular basement membrane, and an overlying segmental cellular crescent. There was 30% tubulointerstitial scarring and moderate arterio- and arteriolosclerosis. Immunofluorescence revealed global granular mesangial staining for IgA (3+), C3 (1+), kappa (2-3+), and lambda (3+). The Oxford MEST-C score (where M is mesangial hypercellularity; E is endocapillary hypercellularity; S is segmental sclerosis; T is tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis >25%; C is active cellular or fibrocellular crescent) was M1E0S1T1C1. The gross hematuria resolved within 5 days.

Figure 1.

(a) Light microscopy from patient 1 shows a glomerulus with fibrinoid necrosis associated with rupture of the glomerular basement membranes (arrows), and a small cellular crescent (periodic acid–Schiff). Original magnification ×1000. (b) Immunofluorescence demonstrates 3+ granular global mesangial staining for IgA. Original magnification ×600. (c) Light microscopy from patient 2 shows a glomerulus with segmental endocapillary hypercellularity including infiltrating neutrophils on a background of mesangial hypercellularity (periodic acid–Schiff). Original magnification ×600. (d) A glomerulus with a segmental scar contains an overlying segmental fibrous crescent with rupture of Bowman’s capsule (periodic acid–Schiff). Original magnification ×600. (a–d) Bars = 50 μm. To optimize viewing of this image, please see the online version of this article at www.kidney-international.org.

A 19-year-old White man with a 6-month history of microhematuria presented with gross hematuria 2 days after receiving the second dose of the Moderna vaccine. The patient had no prior history of gross hematuria, was on no medications, and had no family history of kidney disease. Serum creatinine was 1.2 mg/dl (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration glomerular filtration rate, 87 ml/min per 1.73 m2), and urinalysis revealed numerous red blood cells and no proteinuria. Kidney biopsy, performed 18 days later, demonstrated IgA nephropathy (Figure 1c and d). Among 25 glomeruli sampled, 1 was globally sclerotic. There was mild to moderate, diffuse and global, mesangial hypercellularity. Two glomeruli had segmental endocapillary hypercellularity including infiltrating monocytes and neutrophils. One glomerulus with an incipient segmental scar contained an overlying segmental fibrous crescent. Mild tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis involved approximately 10% of the cortex. Immunofluorescence revealed 1 to 2+ granular global mesangial staining for IgA, C3, kappa, and lambda. The Oxford MEST-C score was M1E1S1T0C0. The gross hematuria resolved within 2 days.

Our 2 patients were diagnosed, for the first time, with active IgA nephropathy, including focal endocapillary hypercellularity, fibrinoid necrosis, and crescents, following a second dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. Anticoagulation with warfarin in 1 case may have potentiated the development of gross hematuria. The history of prior microhematuria, as noted in other reported cases,1, 2, 3 and the presence of focal glomerular and tubulointerstitial scarring in both biopsies support the notion that immune response to vaccination exacerbated a preexisting IgA nephropathy. The rapid development of gross hematuria within several days of the second vaccination implicates a systemic cytokine-mediated flare, possibly via induction of heightened IgA1 anti-glycan immune responses. These reports are analogous to our previous observation that infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 itself can be associated with flares of underlying autoimmune glomerular diseases.4 It remains unclear how the postvaccination setting should be factored into the design of optimal therapy for these active glomerular lesions.

References

- 1.Negrea L., Rovin B.H. Gross hematuria following vaccination for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in 2 patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2021;99:1487. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahim S.E.G., Lin J.T., Wang J.C. A case of gross hematuria and IgA nephropathy flare-up following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Kidney Int. 2021;100:238. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan H.Z., Tan R.Y., Choo J.C.J. Is COVID-19 vaccination unmasking glomerulonephritis? Kidney Int. 2021;100:469–471. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudose S., Batal I., Santoriello D. Kidney biopsy findings in patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1959–1968. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020060802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]