Abstract

Mov10 is a processing body (P-body) protein and an interferon-stimulated gene that can affect replication of retroviruses, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus (HCV). The mechanism of HCV inhibition by Mov10 is unknown. Here, we investigate the effect of Mov10 on HCV infection and determine the virus life cycle steps affected by changes in Mov10 overexpression. Mov10 overexpression suppresses HCV RNA in both infectious virus and subgenomic replicon systems. Additionally, Mov10 overexpression decreases the infectivity of released virus, unlike control P-body protein DCP1a that has no effect on HCV RNA production or infectivity of progeny virus. Confocal imaging of uninfected cells shows endogenous Mov10 localized at P-bodies. However, in HCV-infected cells, Mov10 localizes in circular structures surrounding cytoplasmic lipid droplets with NS5A and core protein. Mutagenesis experiments show that the RNA binding activity of Mov10 is required for HCV inhibition, while its P-body localization, helicase, and ATP-binding functions are not required. Unexpectedly, endogenous Mov10 promotes HCV replication, as CRISPR-Cas9-based Mov10 depletion decreases HCV replication and infection levels. Our data reveal an important and complex role for Mov10 in HCV replication, which can be perturbed by excess or insufficient Mov10.

Keywords: HCV, infectivity, lipid droplets, Mov10, P-body, RNA replication

1 |. INTRODUCTION

An estimated 2%−3% of the world’s population is infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and 3–4 million people are newly infected every year.1–3 More than 80% of HCV infections become chronic and in 20% of patients with untreated chronic HCV, infection leads to liver cirrhosis.2 In the past several years, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma has tripled in the USA and HCV infection is the leading cause of liver transplants in developed countries.3–5 There is no approved vaccine against HCV, and the therapy regimen pegylated interferon (IFN) alpha plus ribavirin (RBV) has not been universally effective6,7 and has significant side effects.6,8,9 The kinetic profiles of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have been well characterized.10–12 Several DAAs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency and have been very helpful in the treatment of HCV infection (reviewed in reference13). Information on the relationship between HCV and host proteins may further advance the understanding of HCV replication and how the virus evades host factors to develop a chronic infection.

HCV, a member of the Flaviviridae family, is an enveloped, positive-sense, and single-stranded RNA virus. The 9.6 kb genome encodes a single polyprotein of approximately 3000 amino acids that is cleaved post-translationally by host and viral proteases into three structural proteins (core, E1, and E2), the hydrophobic peptide p7, and six non-structural (NS) proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B) (reviewed in reference 14). During its replication cycle, HCV interacts with and co-opts several host proteins and processes to establish and maintain infection (reviewed in15). Of these, several proteins facilitate and potentially aid HCV infection, including processing body (P-body) components Rck/p54 (DDX6), PatL1, and LSm1,16–18 while others through diverse and unknown mechanisms affect HCV replication19–22 (reviewed in reference 23).

The innate immune response is the first line of defense against HCV infection. In hepatocytes, RIG-I and MDA5 recognize HCV RNA as foreign and lead to the activation of signaling pathways that result in the production of IFNs.24–27 Once expressed and secreted, IFNs bind their respective receptors, and through the JAK-STAT pathway induce the transcription of hundreds of Interferon stimulated genes (ISGs). Several screens to identify ISGs with antiviral activity against HCV have been performed.28–30 ISGs that significantly reduce HCV replicon activity include IFI6, IRF1, IRF9, ISG20, MX1, OASR1, PKR, and viperin.28,29 ISGs have been identified that affect almost every step of HCV life cycle. However, for some of the most recently identified antiviral ISGs, it is not yet known which stage of HCV infection is inhibited, nor the exact mechanism(s) by which this occurs (reviewed in reference 23).

In a large overexpression screening approach, 380 ISGs were tested for antiviral activity against six viruses, including HCV.30 This screen resulted in the identification of several genes that either had not been characterized as antiviral, or were not known to inhibit the viruses tested. Interestingly, compared to the entire panel of ISGs, proteins with helicase, hydrolase, and nucleic acid binding functionalities were enriched in the pool possessing antiviral properties. Moloney leukemia virus 10 (Mov10) was one such factor whose antiviral activity against HCV was identified in this screen.30 In another screen, Mov10 was identified to associate with HCV subgenomic RNA by using an affinity capture system in conjunction with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.31 The role of Mov10 in the inhibition of retroviral replication has been studied and characterized, in the case of HIV-132–36; Mov10 has also been shown to inhibit HBV gene expression and replication.37–39 The mechanism by which Mov10 affects HCV replication is not known. Mov10, an ISG product, is a component of the mRNA P-body and RNA interference signaling complexes (RISC).40 Mov10 interacts with canonical P-body and RISC proteins including APOBEC3G, Argonaute 1, and Argonaute 2 (Ago2).33,40,41 In addition, Mov10 is a protein that possesses RNA helicase activity and belongs to the DExD superfamily40 and the Upf1-like group of helicases.42

In this study, we examined the effect of Mov10 on HCV infection and demonstrated the inhibition of HCV replication. Moreover, we determined which properties of Mov10 are associated with suppression of HCV replication.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Cell line

All experiments described in this study were performed using human hepatoma cells (Huh7.5.1) provided by Charles M. Rice (Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% of CO2 environment.

2.2 |. Virus constructs and in vitro RNA transcription

The virus constructs Jc1-378-1-Ypet and Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) were provided by Charles M. Rice and encode fully infectious chimeric genotype 2a HCV.43 In these virus chimeras, the core, E1, E2, and 33 amino acids of NS2 are from the J6 clone and the remaining proteins are from JFH1. Jc1-378-1-Ypet is engineered to encode yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) inserted at codon 378 of NS5A (domain III), while Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) contains Gaussia luciferase at the P7-NS2 junction. The luciferase gene is flanked by foot-and-mouth disease 2A protein. Upon HCV infection, translation, and processing of viral proteins, the luciferase protein is expressed and secreted into cell culture medium. To generate HCV RNA, the plasmid DNA was purified using a midi-prep kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). The DNA (2 μg) was linearized by XbaI or ScaI cleavage (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) at a site upstream of a T7 promoter for 4 hours (h) at 37°C. The linearized DNA was purified using the QIAquick PCR-clean up kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and transcribed into RNA using the MEGAScript T7 kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 0.5 μg of linearized DNA per reaction incubated for 5 hours at 37°C. DNase I was added and the reaction mixture was incubated for an additional 20 minutes. The integrity of the RNA was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis and the concentration determined by measurement of the optical density at 260 nm. After purification by RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), the RNA was aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

2.3 |. Overexpression plasmids and transfection

Plasmids expressing YFP-DCP1a, mRFP-DCP1a, FLAG-DCP1a, YFP-Mov10, mRFP-Mov10, and FLAG-Mov10 were constructed as previously described.33 The plasmids express human DCP1a or Mov10 N-terminally tagged with FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK), YFP or mRFP. Expression plasmids for mutant Mov10 proteins (G527A, R730A/N731A, V866A, and DQAG) were constructed as previously described35 and express proteins tagged N-terminally with YFP.

Transfections of 60%−80% confluent cells were performed using Fugene 6 reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). For dose-response experiments, cells were transfected with 0.2–0.8 ng/μL of Mov10 expression plasmids in 24-well plates with 0.5 ml medium per well. In experiments to determine the effect on virus production, we used 0.8 ng/μL of Mov10 expression plasmid in T25 flasks with 4 mL medium each.

2.4 |. Electroporation and virus production

To produce HCV virus, 10 μg of HCV RNA was transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells by electroporation as previously described.44 Briefly, 70% confluent Huh7.5.1 cells were trypsinized from a T75 flask, washed twice with ice-cold DPBS and resuspended in cold DPBS at a concentration of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml. About 700 μL of this suspension was added to a tube containing 10 μg HCV RNA, mixed briefly and transferred to a 0.4 cm cuvette (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA), and electroporated using a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cells were allowed to rest for 10 minutes at room temperature, then, transferred to a T75 flask containing 10 mL growth medium. The next day, the medium was changed and cells were incubated for two additional days. After 72 hours of post electroporation (hpe), virus-containing medium was collected and replaced every 16 hours, filtered through a 0.45 μm filter, and stored in aliquots at −80°C.

To determine the effect of Mov10 on virus production, 10 μg HCV RNA was electroporated into Huh7.5.1 cells as described above. A 5 × 106 electroporated cells were diluted into 20 mL medium and plated onto T25 flasks (4 mL per flask). After 16 hours the media were replaced with fresh medium and transfected with 0.8 ng/μL Mov10 or control plasmids (empty vector/DCP1a). Virus-containing media were collected and replaced 24, 48, and 72 hours post transfection (hpt) and assayed for virus titers (TCID50/mL) and HCV RNA levels by RT-qPCR.

2.5 |. Determining virus titers by limiting dilution assay (TCID50)

A previously described limiting dilution assay was used to determine viral titer.44 For virus released from cells into the medium, 3 × 103 cells were plated onto a 96-well plate and the next day infected with 100 μL of undiluted virus-containing medium (8 wells) or 100 μL diluted virus (five serial dilutions, from 10−1 to 10−5, 8 wells per dilution). For cell-associated virus, infected cells were detached from 6-well plates, washed twice with DPBS, and then, resuspended in medium (at a volume equal to the virus-containing collected medium). Cells were then subjected to four freeze-thaw cycles using a dry-ice ethanol bath and a 37°C water bath and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The supernatant was used to make dilutions and infect cells as described above. For both intra- and extracellular virus titers, cells were fixed at 72 hours post infection (hpi) with 100% of cold methanol for 30 minutes at −20°C, followed by blocking with 1% of BSA and 0.2% of skim milk in 0.1% of Tween-20 in PBS (PBS-T). To quantify infection, cells were stained for HCV NS5A using NS5A monoclonal antibody 9E10 (provided by Charles M. Rice) and a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (ImmPRESS, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), followed by addition of an HRP substrate, diaminobenzene (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). NS5A-positive wells were counted and recorded under a light microscope. TCID50 was calculated by Reed & Muench Calculator as previously described.45

2.6 |. RNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR

To determine HCV RNA levels in released virus, 100 μL TRIzol reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to 300 μL virus-containing medium and total RNA purified following the manufacturer’s instructions. To determine intracellular HCV RNA and IFNβ mRNA, cells were lysed in the plate by addition of TRIzol and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed with the ABI 7500 machine (Applied Biosystems) using the Power SYBR Green RNA-to-CT 1-Step kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Primers specific for the 5′ untranslated region of the HCV genome were 5′-TGCGGAACCGGTGAGTACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCGGAACCGGTGAGTACA-3′ (reverse), while primers specific for Mov10 were 5′-AATTCCAAGGCCAAGAACGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAGATCCAGCTGCACAAA-3′ (reverse). To determine HCV RNA copy numbers, a standard curve was generated by amplifying serially diluted in vitro transcribed HCV RNA ranging from 2 × 107 to 2 × 101 genome copies. To determine relative RNA levels, HCV or Mov10 cycle threshold (CT) was first normalize to GAPDH CT using: ΔCT = CTHCV or Mov1—CTGAPDH, and then, (2(−ΔΔCT)) was calculated using ΔΔCT = ΔCTHCV or Mov10—ΔCTcontrol.

2.7 |. Gaussia luciferase activity assay

To measure replication of the Gaussia luciferase reporter HCV, we used the Gaussia Glow Assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Briefly, 30 μL of cell supernatant was added to 30 μL of Luciferase Cell Lysis Buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in black 96-well microplates and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. About 50 μL of 1× Coelenterazine was added according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and luciferase activity (relative light units (RLU)) was measured with an EnSpire 2300 Multilabel Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Duluth, GA, USA), and normalized to an uninfected control.

2.8 |. Virus infectivity

To determine the effect of host factor over-expression on HCV infectivity, Jc1-378-1-Ypet HCV RNA was electroporated into Huh7.5.1 cells, as described above. About 16 hpe cells were transfected with relevant plasmids coding proteins of interest. Virus containing supernatants were collected at various time points post electroporation. Specific infectivity is defined as the ratio of the extracellular RNA copy number to the infectious viral titer. Total RNA was isolated from 200 μL filtered supernatants and analyzed for the number of HCV RNA copies by RT-qPCR. Infectious titer was determined by infecting naïve Huh7.5.1 cells with 800 μL filtered supernatants. The TCID50/mL values were determined as described above.

In a second assay, virus-containing supernatants were normalized by RT-qPCR for total HCV genome copy number then used to infect naïve Huh7.5.1 cells. To compare the infectivity of the HCV-containing supernatants, cells were imaged by fluorescent microscopy for HCV NS5A-Ypet expression. After imaging, the media and cells were collected and cells were divided into two portions. The first portion was probed for HCV core protein levels (and GAPDH as a loading control) by Western blot analysis. Total RNA was isolated from the second portion and along with the media collected at 72 hpi, analyzed by RT-qPCR for HCV RNA levels.

2.9 |. Western blot analysis

Cells were trypsinized then lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mM of NaCl, 50 mM of Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM of EGTA, 1 mM of EDTA, 0.1% of SDS, and 1% of Triton X-100) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The protein concentration in the whole cell lysate was measured using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). About 10 to 50 μg of protein were electrophoresed on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% of skim milk in PBS for 1 hours, then, probed with anti-HCV core at 1:5000 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat #ab2740), GAPDH at 1:10 000 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, Texas, USA, Cat #sc-365062), or Mov10 at 1:3500 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat #ab80613), diluted in PBS, followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) (anti-mouse Cat #A5278, anti-rabbit Cat #A0545). Bound antibodies were visualized by adding Luminata Forte Western HRP substrate (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) to the membrane and imaged with a Fuji camera system.

2.10 |. Confocal microscopy

2 × 104 cells were plated on 8-well chambered #1 borosilicate cover glass (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were infected with either Jc1-378-1-Ypet or Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) for 48 hours. Infected cells were fixed with 4% of paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature, then, permeabilized with 1% of BSA, 0.1% of skim milk, and 0.1% of Triton-X in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Primary antibodies were stained at room temperature for 1.5 hours at the following dilutions in PBS: NS5A (9E10) 1:500, core (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat #ab2740) 1:500, or Mov10 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat #ab80613) 1:1000. Staining for cytoplasmic lipid droplets (LDs) was with BODIPY 493/503 (Invitrogen, Cat #D3922) at a 1:500 dilution in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were also counterstained for nuclei using Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, Cat #H3570) at a 1:10 000 dilution in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. Following the primary antibodies, secondary antibody anti-mouse Alexa 647 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, Cat #A21235) was used to label NS5A and core, while anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, Cat #A11036) was used to label Mov10 (both at 1:1500 dilutions for 1 hours at room temperature). Images were taken with a confocal laser scanning Leica TCS SP8 (Leica Microsystems, Germany) using 40× (water or oil) and 63× oil objectives.

2.11 |. Knockout of endogenous Mov10

The levels of endogenous Mov10 protein were down regulated using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology.46,47 Guide-RNA (gRNA) sequences were designed to target Cas9 to the 5′end of the Mov10 gene (5′-TGTCCAGTCCCCGAACGACC-3′). A plasmid containing the designed gRNA, Cas9, and GFP as a reporter (pCas9-GFP-Mov10_T1) was purchased from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD, USA). A 0.5 μg of pCas9-GFP-Mov10_T1 plasmid was transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells. About 48 hpt the GFP positive cells were sorted and collected by flow cytometry. Half of the cell population was cultured and designed as Huh7.5.1_R1, while the other half was diluted to a single cell per well on a 96-well plate and expanded. The levels of endogenous Mov10 were evaluated for Huh7.5.1_R1 and the individual clones by immunocytochemistry and western blot. Huh7.5.1_R1, cells with decreased levels of Mov10 (Huh7.5.1_E9), and undetectable levels of Mov10 (Huh7.5.1_D6) were used for HCV infection and replication assays.

2.12 |. Statistical analyses

Prism 6 (Graphpad) was used for plotting graphs and calculation of means and standard deviation, and for significance testing using Student’s t test.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Overexpression of Mov10 inhibits HCV infection

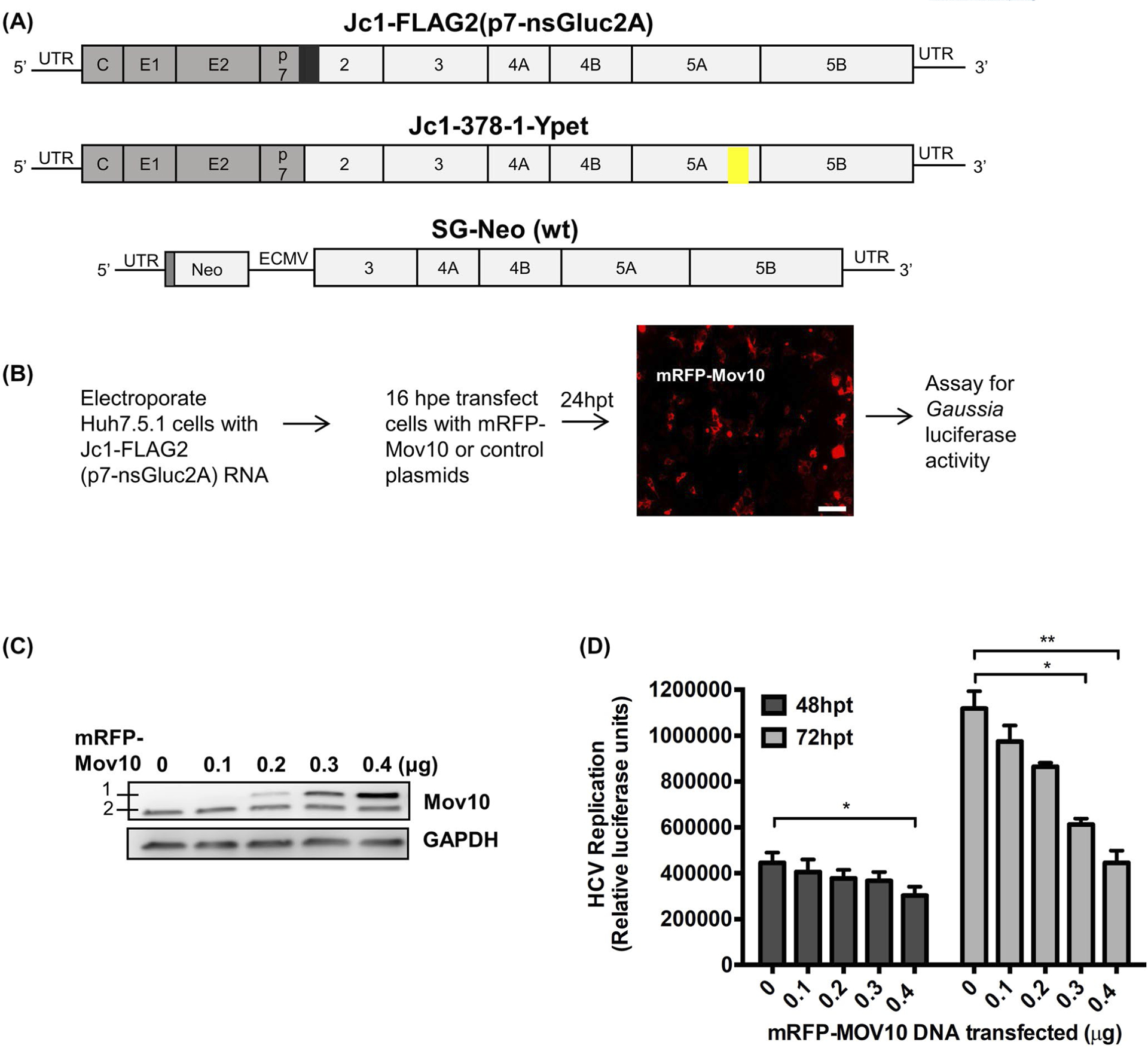

The antiviral activity of Mov10 against retroviruses has been previously described.32,33,35,36,48,49 It has also been reported that Mov10 has antiviral activity against HCV.30 We wished to expand the understanding of how Mov10 inhibits HCV. We began by confirming whether overexpression of Mov10 inhibited HCV infection in Huh7.5.1 cells and whether this inhibition was dose-dependent. Huh7.5.1 cells were electroporated with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) RNA (Figure 1A,B). At 16 hpe cells were transfected with varying amounts of mRFP-Mov10 expression plasmid. The Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) construct expresses fully infectious genotype 2a HCV and upon viral replication, Gaussia luciferase is secreted into the culture medium.43 We assayed the supernatants for Gaussia luciferase activity to determine the level of HCV replication at 48 and 72 hpt. As shown by immunoblotting, increasing amounts of Mov10 plasmid led to increasing exogenous Mov10 expression in Huh7.5.1 cells (Figure 1C). HCV replication was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of Mov10 overexpression on HCV replication. A, Schematic representation of HCV RNA used in this study. The 5′ and 3′ UTR regions are shown as black lines and the viral polyprotein is depicted as an open box with individual proteins separated by vertical lines. The structural proteins are from the J6 clone (gray fill) and non-structural proteins from the JFH1 clone (white fill). Fully infectious genotype 2a chimeric clones Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) carries a Gaussia luciferase reporter gene (black box) at the p7-NS2 junction as a secretable marker for viral replication and Jc1-378-1-Ypet expresses an NS5A-Ypet (yellow box) fusion protein as a marker for viral replication. SG-neo (wt) is a subgenomic replicon (genotype 1a) encoding a neomycin resistance gene and HCV non-structural proteins NS3-NS5B driven by an EMCV IRES. B, Huh7.5.1 cells were electroporated with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) RNA. After 16 hours of post electroporation (hpe) cells were transfected with varying amounts (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 μg) of an mRFP-Mov10 expression plasmid. After 24 hours of post transfection (hpt) cells were checked for Mov10 expression (representative picture is shown). Scale bar represents 100 μm. C, 72 hpt cells were lysed and assayed for Mov10 expression by western blot. A 1 is exogenous mRFP-Mov10 and 2 is endogenous Mov10. D, 48 and 72 hpt cell culture media were assayed for Gaussia luciferase activity. Each data point represents average value of 3 individual experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed by using Student’s t-test (not significant (ns), *P > .05, **P < .01)

3.2 |. Mov10 inhibits HCV RNA replication in both infectious virus and subgenomic replicon systems

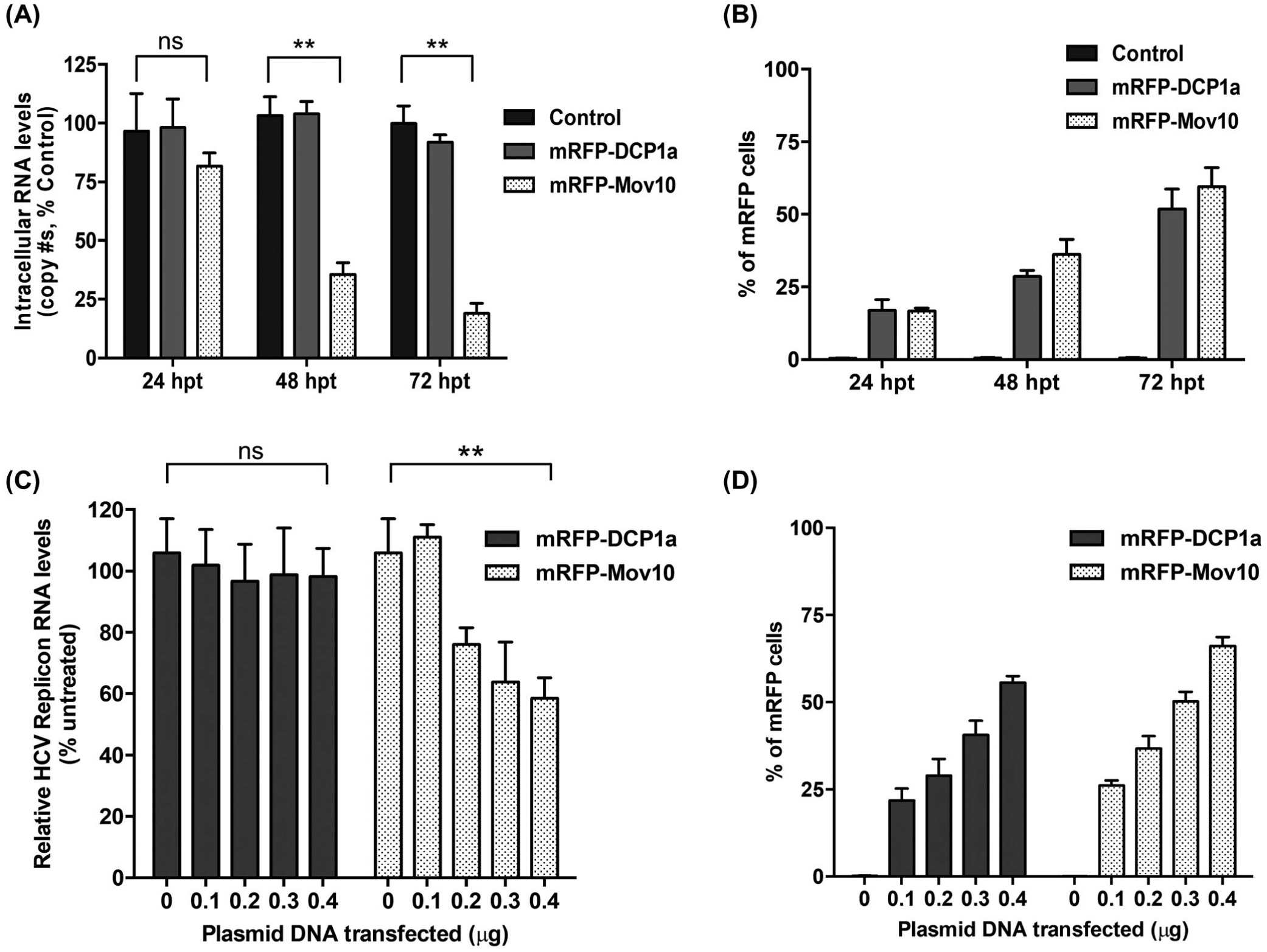

To further characterize the antiviral effect of Mov10 overexpression on HCV replication, we measured the RNA levels of HCV in cells overexpressing Mov10. As a control, we used DCP1a in expression vectors isogenic with those used for Mov10. We transfected a plasmid expressing mRFP-Mov10 into Huh7.5.1 cells harboring HCV RNA (encoding the entire HCV genome, introduced by electroporation) and 24, 48, and 72 hpt assayed cells for HCV RNA levels. As shown in Figure 2A, overexpression of DCP1a had no significant effect on HCV RNA levels. Overexpression of Mov10, however, decreased viral RNA by ~20% at 24 hpt. This inhibition increased over time to ~70% at 48 hpt and ~80% by 72 hpt. Overexpression of mRFP-DCP1a and mRFP-MOV10 was confirmed by quantification of fluorescent cells at each time point (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Mov10 inhibits HCV RNA production from fully infectious virus and subgenomic replicon. A, To determine the effect of Mov10 overexpression on HCV RNA levels, Huh7.5.1 cells were electroporated with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) RNA (10 μg). About 16 hpe cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of control (pUC18), mRFP-DCP1a, or mRFP-Mov10 plasmids. At 24, 48 and 72 hpt total RNA was isolated from the cells (intracellular HCV RNA) and analyzed for HCV RNA levels by RT-qPCR. B, The levels of DCP1a and Mov10 expression were quantified by flow cytometry and presented by percent of mRFP cells. C, SG-neo (wt) replicon RNA (1 μg) was transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells by electroporation. About 16 hpe cells were transfected with either a plasmid expressing mRFP-DCP1a or mRFP-Mov10 (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, or 0.4 μg). Cells were collected at 48 hpt and analyzed for HCV RNA levels by RT-qPCR. D, The levels of DCP1a and Mov10 expression were quantified by flow cytometry and presented by percent of mRFP cells. Data were normalized to data for the empty plasmid control. Each data point represents average value of 3 individual experiments. Error bars represent SD

To further investigate the effect of Mov10 on HCV RNA levels, we examined the replication of a sub-genomic HCV replicon in cells overexpressing Mov10. The replicon “SG-neo (wt)”50 expresses HCV viral proteins NS3 to NS5B that are necessary for RNA replication, but lacks the structural proteins and NS2 that are required to assemble and produce infectious virions (Figure 1A). Use of a replicon system enables one to study stages of the virus life cycle other than entry, assembly, maturation, viral release, and secondary infections. Hence, we initially determined the effect of Mov10 on HCV RNA levels using a replicon system. We overexpressed Mov10 or DCP1a in cells harboring the HCV subgenomic replicon (introduced by electroporation) and assayed HCV RNA levels at 48 hpt by RT-qPCR. The levels of HCV replicon RNA were normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels. Overexpression of DCP1a had no effect on HCV RNA levels, however, overexpression of Mov10 inhibited HCV RNA replication in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C). Overexpression of mRFP-DCP1a and mRFP-MOV10 was confirmed by quantification of fluorescent cells for each amount of plasmid DNA (Figure 2D).

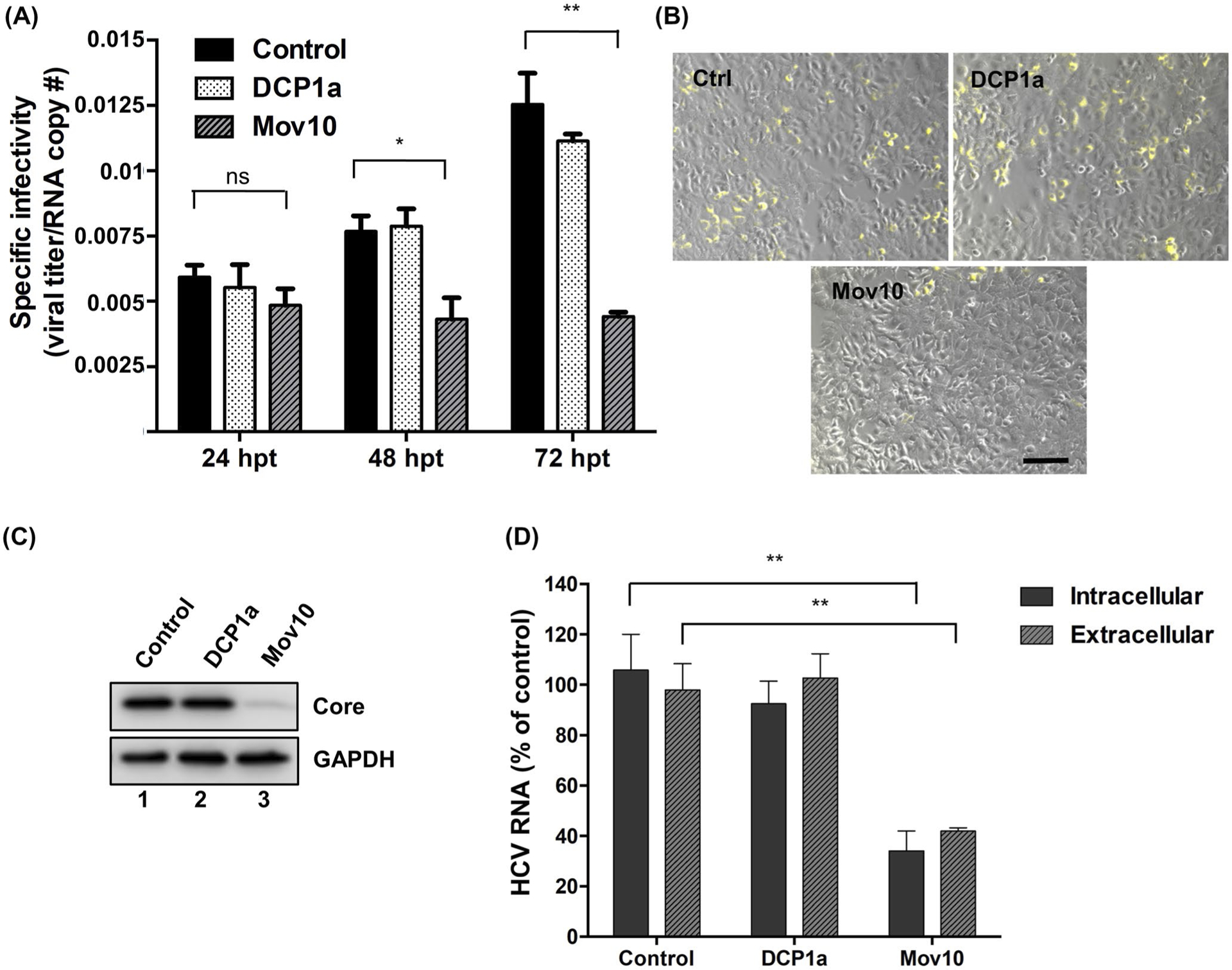

3.3 |. Mov10 overexpression decreases HCV infectivity

To elucidate the mechanistic effects of Mov10 overexpression on HCV production, we used the fully infectious HCV cell culture system. HCV particles were produced from Huh7.5.1 cells that overexpressed Mov10 (producer cells), and the HCV-containing supernatants were used to infect naïve target cells. In addition to the reduced HCV replication in producer cells, shown in Figures 1D and 2A, we found that the specific infectivity was reduced for HCV particles produced from Mov10-overexpressing cells (Figure 3A). The inhibition at 24 hpt was not significantly different from control, but inhibition increased over time to ~50% at 48 hpt and 72 hpt.

FIGURE 3.

HCV virus produced in Mov10 overexpressing cells has decreased specific infectivity and the infectivity of released virus. Jc1-378-1-Ypet RNA (10 μg) was electroporated into Huh7.5.1 cells. About 16 hpe cells were transfected with either empty plasmid (control), or a plasmid expressing 0.4 μg of FLAG-DCP1a or FLAG-Mov10. Virus containing supernatants were collected at 24, 48, and 72 hpt. A, Specific infectivity was determined by quantifying the number of HCV genome copies by RT-qPCR and the HCV titer by limiting dilution assay. The TCID50/mL values were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Specific infectivity is expressed as the ratio of infectious units to genome copies. B, Virus containing supernatants collected from cells overexpressing Mov10, DCP1a, were normalized for total virus by RT-qPCR (6.25 × 103 HCV RNA copy numbers). A 72 hpi cells were imaged by fluorescent microscopy following HCV NS5A-Ypet (yellow) expression (representative pictures are shown). Scale bar represents 100 μm. After imaging, cells were collected into two portions. C, The first portion was probed for HCV core protein levels (and GAPDH as a loading control) by Western blot analysis. D, Total RNA was extracted from cells and supernatant of the second portion and analyzed by RT-qPCR for HCV RNA levels. Data were normalized to data for the empty plasmid control. Each data point represents average value of 2 individual experiments. Error bars represent SD

To ensure that the decreased HCV replication and specific infectivity from Mov10-overexpressing producer cells was not due to cell death, we examined whether overexpression of Mov10-induced cytotoxicity. We found that transfection of the Mov10 expression plasmids and/or overexpression of Mov10 had no effect on cell viability as determined by XTT assay, performed as previously described51,52 (data not shown).

To confirm the effect of Mov10 overexpression in producer cells on the infectivity of released HCV, naïve Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with HCV NS5A-Ypet produced in cells overexpressing DCP1a (control) or Mov10. Prior to infection, supernatants were normalized by RT-qPCR for HCV genome copies. Consistent with our previous findings, fewer infected cells were observed following infection with HCV produced in Mov10 overexpressing cells (Figure 3B). Additionally, western blot analysis for HCV core protein (Figure 3C) and RT-qPCR analysis of HCV RNA levels in the infected cells (Figure 3D) revealed a reduction of viral protein, intracellular, and extracellular RNA in the target cells. As all infections were performed with HCV normalized by genome copies, these data are consistent with reduced specific infectivity, leading to fewer target cells being infected. In each case, the overexpression of the control protein DCP1a had no impact on HCV, indicating that the phenotypes were dependent on Mov10 overexpression.

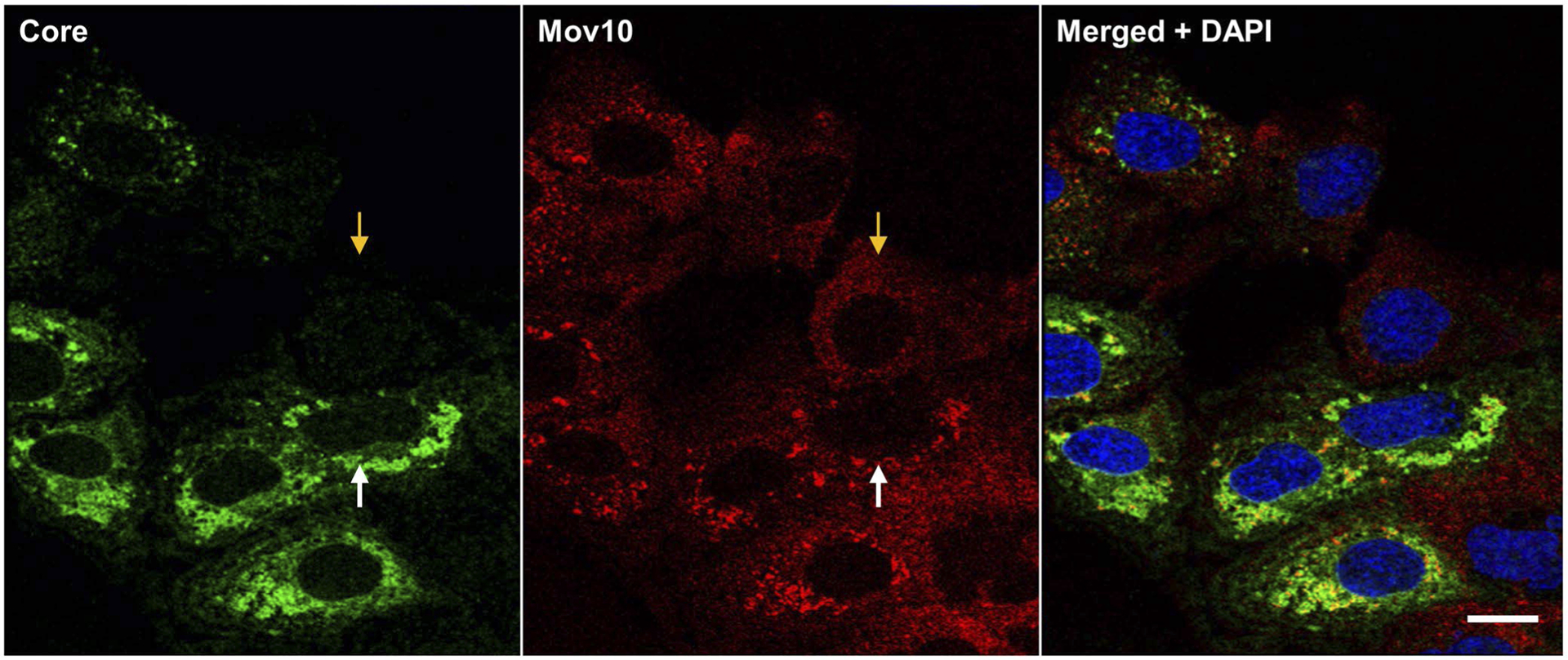

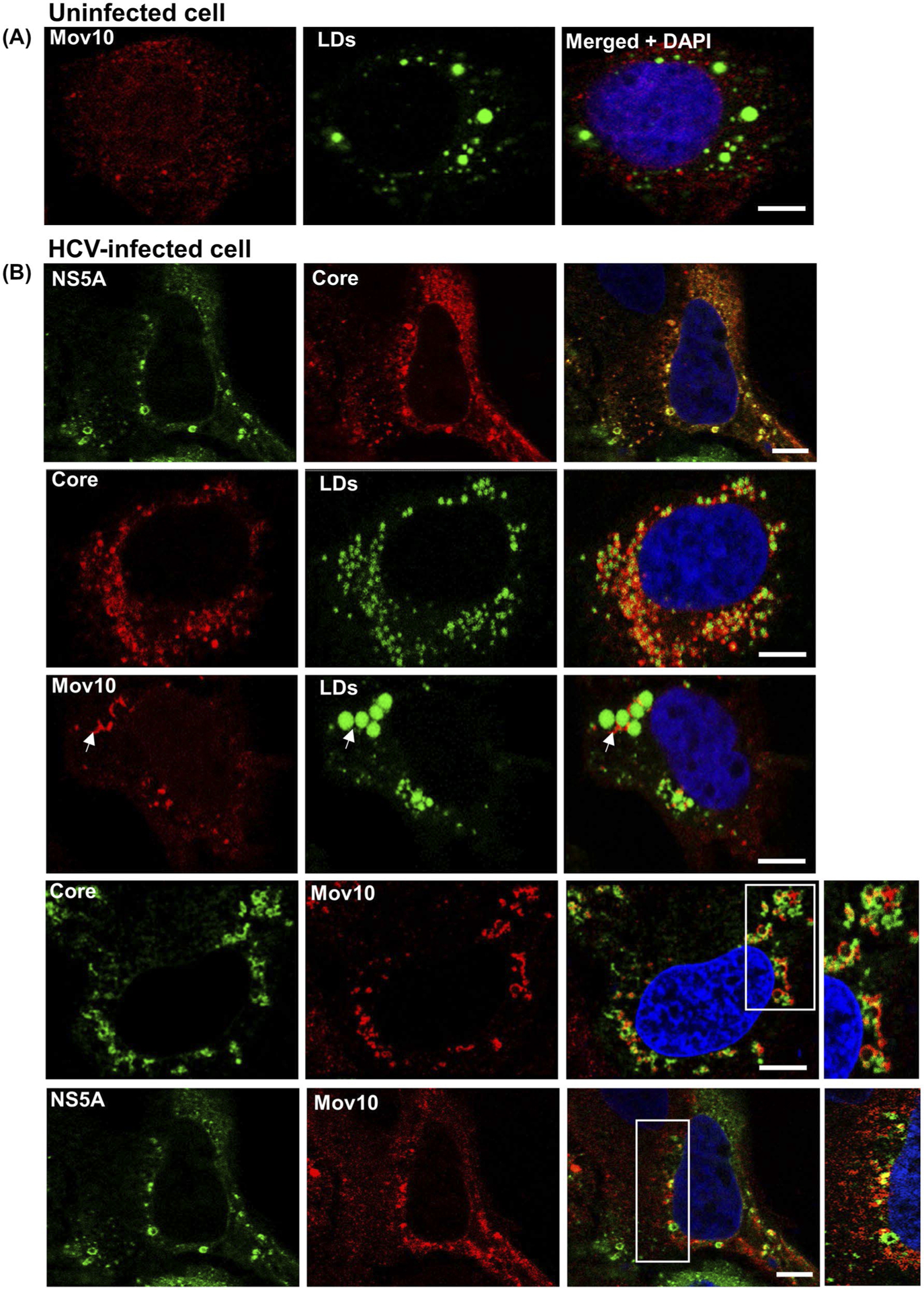

3.4 |. HCV infection alters the distribution of endogenous Mov10

In uninfected cells, endogenous Mov10 is distributed throughout the cytoplasm, with occasional foci that colocalize with canonical P-body proteins DCP1a, APOBEC3G, or DCP2.20,33,35 To determine whether this distribution was altered during HCV infection, uninfected, and HCV-infected cells were fixed then stained for endogenous Mov10 and HCV core as described in Materials and Methods. Imaging by confocal microscopy showed that Mov10 distributed throughout the cytoplasm in uninfected cells (Figure 4, orange arrows), while Mov10 formed distinct foci in close proximity to HCV core in infected cells (Figure 4, white arrows).

FIGURE 4.

HCV infection alters the distribution of endogenous Mov10. Huh7.5.1 cells were infected with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) (0.5 MOI). A 48 hpi cells were fixed in 4% of paraformaldehyde and stained for HCV core (Alexa647—pseudocolored green green), Mov10 (Alexa568—red), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342—blue). Cells were imaged on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope with a 40× water objective. Orange and white arrows indicate an uninfected and an infected cell, respectively. Scale bar represents 15 μm

3.5 |. HCV infection results in endogenous Mov10 localization with lipid droplets (LDs) with HCV core

HCV has been shown to hijack some P-body proteins during infection, redistributing them from P-bodies to viral pre-assembly sites on LDs.53 Hence, we hypothesized that upon HCV infection, Mov10 would be redistributed to LDs where HCV proteins are known to localize in replication and assembly complexes.54 To examine the localization of Mov10, uninfected and infected cells were stained for endogenous Mov10, HCV core, and LDs. In uninfected cells, endogenous Mov10 is mostly diffuse with occasional small puncta and does not localize at or around LDs (Figure 5A). As expected, in HCV infected cells, core protein and NS5A localized around LDs (Figure 5B). In these infected cells, Mov10 was also found at the periphery of LDs (Figure 5B, white arrows) partially overlapping with HCV core and NS5A (Figure 5B), consistent with prior reports of P-body proteins at LDs in HCV-infected cells.20,53,55

FIGURE 5.

HCV infection results in endogenous Mov10 localization at cytoplasmic LDs in close proximity to HCV core and NS5A. A, Uninfected Huh7.5.1 cells were fixed in 4% of paraformaldehyde and stained for endogenous Mov10 (Alexa568—red), lipid droplets (LDs, BODIPY 493/503—green), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342—blue). B, Infected Huh7.5.1 cells were fixed and stained for LDs (BODIPY 493/503—green), and/or HCV core (Alexa647—pseudocolored red or green), and/or endogenous Mov10 (Alexa568—red), and/or NS5A (Ypet—green), and nuclei (Hoechst 33342—blue). White arrows show Mov10 localization at LDs. HCV core and Mov10 crescents are both present at the periphery of LDs. In the inset, Mov10, and core or NS5A appear at distinct and often non-overlapping sites around LDs. Cells were imaged on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope with a 63× oil objective. Scale bars represent 5 μm

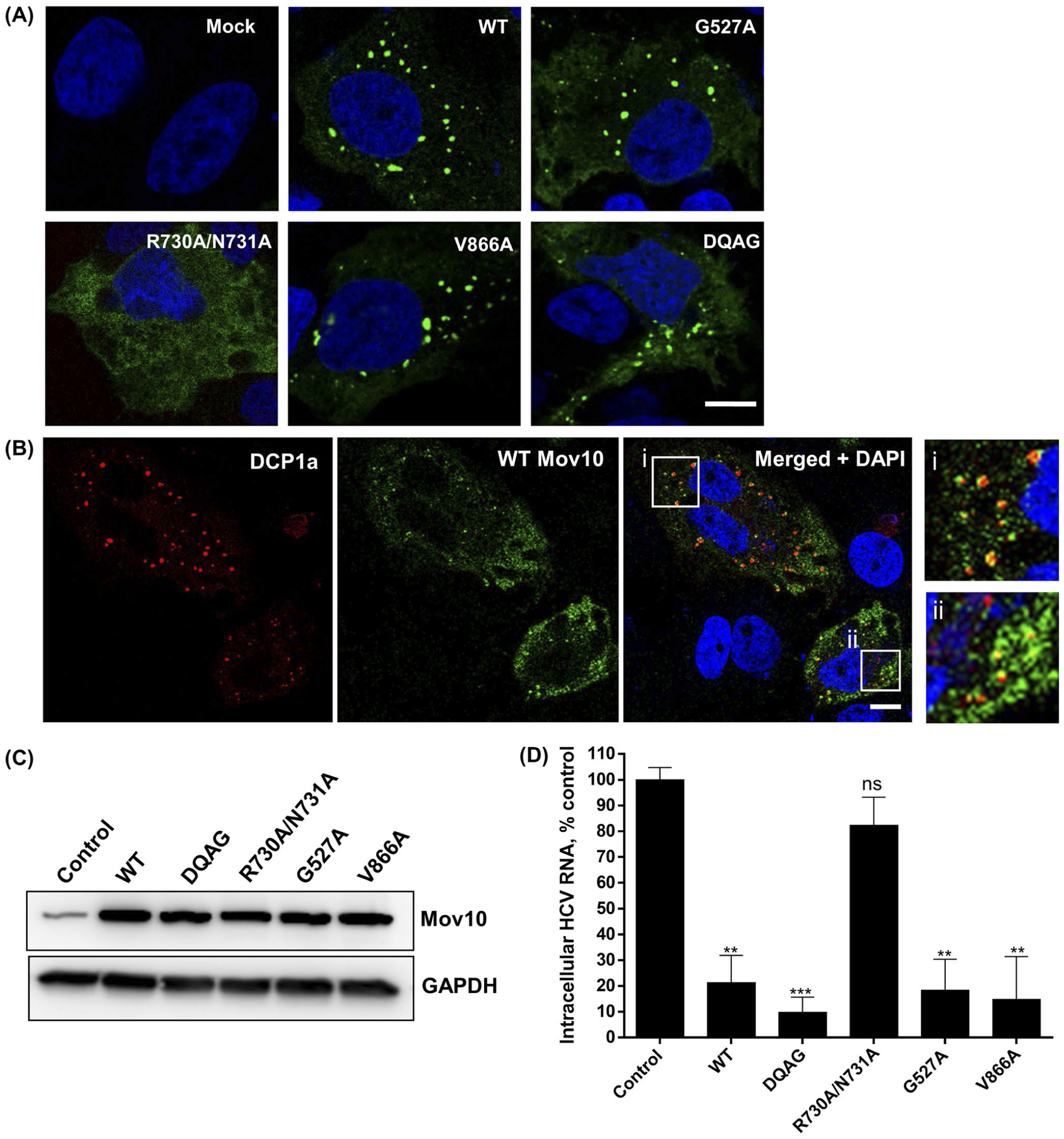

3.6 |. Mov10 RNA binding is required for its antiviral activity

Mov10 has several reported and putative functions involving RNA modulation as a helicase, a component of mRNA P-bodies, and RISC. These functions likely require the RNA binding activity of Mov10. It has been shown that the RNA binding activity of Mov10 contributes to its antiviral activity against HIV-1 infection.33,35 To determine which functions of Mov10 are related to its ability to suppress HCV RNA levels, we used a panel of plasmid constructs that overexpress the Mov10 mutants, which are expected to disrupt the putative functions of Mov10.35 Specifically, the G527A mutation was designed to disrupt ATP binding, and thereby, the helicase function of Mov10; the R730A/N731A mutations were designed to interfere with binding of viral RNA; V866A was shown to disrupt localization of Mov10 at P-bodies; the DQAG active site mutant was designed to have no helicase activity. Some of these Mov10 mutants were reported to decrease the antiviral effect of Mov10 overexpression on HIV infection. The localization of the Mov10 mutants, with the exception of the RNA-binding deficient double mutant, was the same as the wild-type (WT), forming multiple discrete foci in the cytoplasm (Figure 6A), which is consistent with a previous report.35 Mov10 foci co-localized with P-body protein DCP1a (Figure 6B) and have previously been shown to colocalize with DCP235 or APOBEC3G33 also present at P-bodies. Mutants G527A, V866A, and DQAG, however, showed fewer foci per cell and were not localized to P-bodies as efficiently as the WT Mov10 (data not shown). Interestingly, the RNA-binding deficient mutant R730A/N731A was completely diffused throughout the cytoplasm, with no granules seen in any cells.

FIGURE 6.

Mov10 residues that are required for RNA binding are also required for HCV inhibition. Mutations DQAG, R730A/N731, G527A, V866A that affect helicase activity, RNA binding activity, ATP binding activity for helicase, localization to P-body, respectively, were tested for their effect on HCV replication (A and B). Images were acquired on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscopy with 63× oil objectives. Scale bar represents 5 μm. A, 0.4 μg of plasmid (YFP-tagged Mov10 WT or mutants) was transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells. A 48 hpt cells were fixed and stained for nuclei (blue). B, YFP-tagged WT Mov10 and mRFP-DCP1a (0.4 μg of each) were transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells. A 48 hpt cells were fixed and stained for nuclei. Colocalization of Mov10 and P-body protein DCP1a is shown in insets i and ii. C, 10 μg of HCV RNA (Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A)) was electroporated into Huh7.5.1 cells. A 16 hpe cells were transfected with FLAG-Mov10 expression plasmids (0.4 μg/well, WT, or mutants). A 72 hpt expression levels of the FLAG-tagged WT and mutant Mov10 proteins were checked by Western blot analysis. D, 72 hpt cells were also assayed for intracellular HCV RNA levels by RT-qPCR. Data were normalized to data for the empty plasmid control. Data points represent average of 3 individual experiments. Error bars represent SD

To determine whether the Mov10 mutations affected antiviral activity, we overexpressed the mutants in Huh7.5.1 cells that had been electroporated with Jc1-FlAG2(p7-nsGluc2A). Expression levels of all Mov10 proteins were comparable (Figure 6C). At 72 hpt, cells were harvested and assayed for HCV RNA levels by RT-qPCR. We found that mutants G527A, V866A, and DQAG retained their antiviral activity, decreasing HCV RNA levels as efficiently as the WT Mov10. However, the double mutant R730A/N731A lost its antiviral activity (Figure 6D), suggesting that RNA binding is required for the antiviral activity of Mov10.

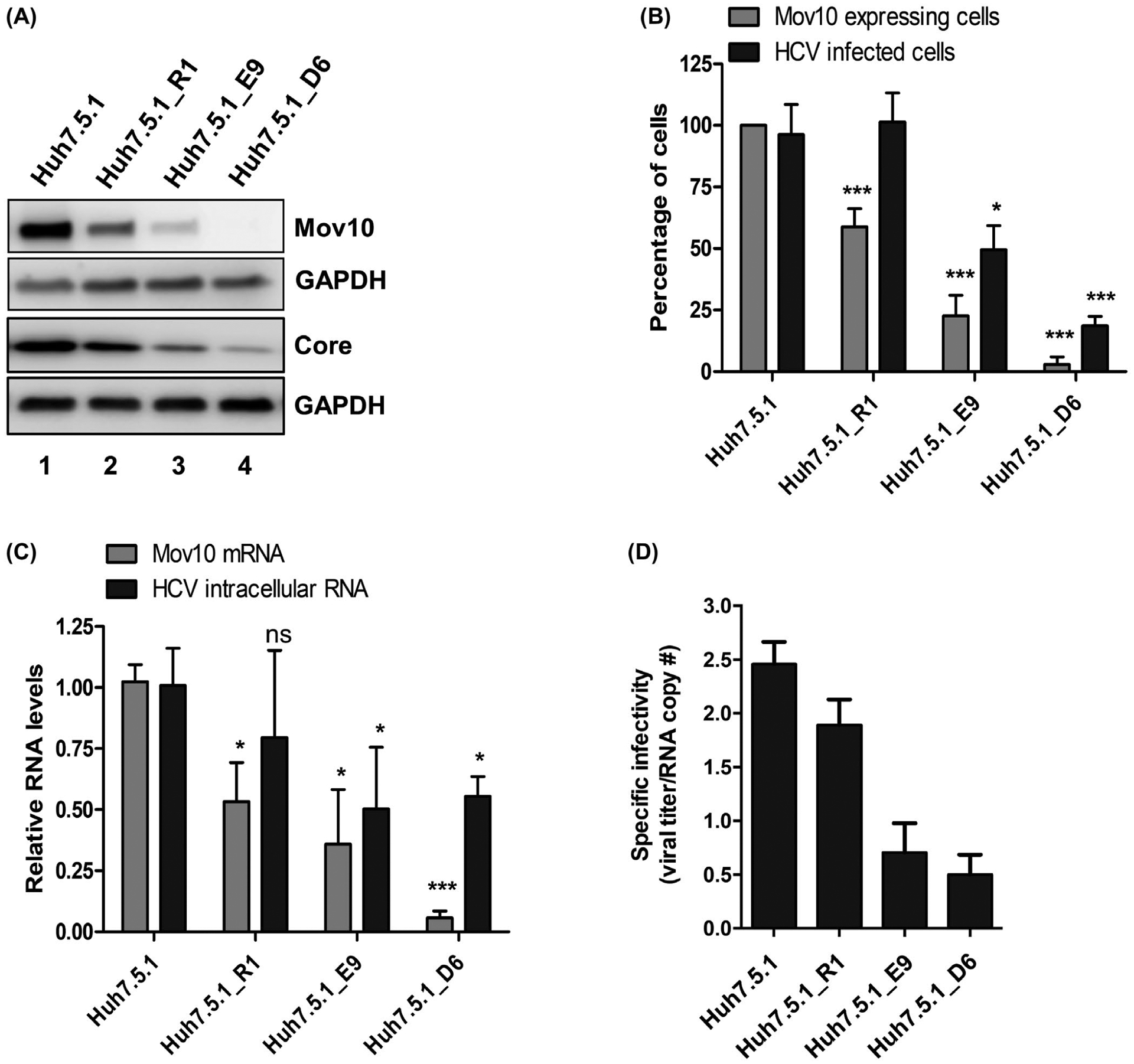

3.7 |. Targeting Mov10 with CRISPR-Cas9 decreases HCV replication

Following our observations that Mov10 overexpression impaired HCV infection and replication, we utilized the CRISPR-Cas9 technology46,56 to knockout endogenous Mov10 from Huh7.5.1 cells to reveal the effects of a lack of Mov10. We designed a gRNA that was complementary to the 5′end of the Mov10 gene. Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing the gRNA, Cas9, and reporter GFP. At the peak of GFP expression, GFP-positive cells were collected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Half of these cells were expanded and referred to as Huh7.5.1_round 1 (Huh7.5.1_R1), the other half were plated at ~1 cell/well and expanded. After screening for Mov10 protein levels via immunocytochemistry, to identify clones displaying efficient Mov10 knockout, Huh7.5.1_E9 and Huh7.5.1_D6 were selected for further analysis. To address the relationship between knockout of Mov10 and HCV infection, parental cells and knockout cells were infected with HCV, incubated for 72 hours then analyzed by western blotting, imaging and RT-qPCR. By western blot, Huh7.5.1_R1 had decreased levels of Mov10, compared to the parent cell line Huh7.5.1 (Figure 7A, lane 2). In contrast, Huh7.5.1_E9 had much less Mov10 (Figure 7A, lane 3), and Huh7.5.1_D6 had no detectable Mov10 (Figure 7A, lane 4). Levels of HCV core protein confirmed that HCV protein expression correlated with Mov10 expression. Similarly, quantification of Mov10-expressing cells and HCV infected cells revealed that populations with few Mov10-expressing cells correlated with fewer HCV infected cells (Figure 7B). No HCV core protein was visible in clone D6 by western blot, consequently, we suspect that the small number of cells counted by flow cytometry are false positives. Finally, the cells with the lowest levels of Mov10 mRNA measured by RT-qPCR, also possessed the lowest levels of HCV RNA (Figure 7C). In addition to verifying the role of Mov10 in supporting HCV replication, we confirmed the importance of Mov10 for production of infectious HCV particles. The clones were electroporated with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) and at 72 hpt, supernatant collected and assayed for HCV genome copies and viral titer, to determine specific infectivity. As previously observed with Mov10 overexpression (Figure 3A), knockout of Mov10 reduced the infectivity of released HCV particles (Figure 7D). In each of these analyses, the strongest phenotype was found in D6, the cells with the lowest level of Mov10 expression, providing further evidence for the role of Mov10 in HCV replication.

FIGURE 7.

CRISPR/Cas9-based suppression of endogenous Mov10 levels also suppresses HCV replication. Huh7.5.1 cells were transfected with pCas9-GFP-Mov10_T1 expressing Cas9 endonuclease, and a guide-RNA that recruits the endonuclease to the 5′ end of the Mov10 gene. Clones were isolated at various steps of selection as described in Materials and Methods. Before selection (parental cell line Huh7.5.1); first round selection (R1); second round selection (E9 and D6. A, Equal numbers of cells were infected with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) at an MOI of 0.5, then, harvested 72 hpi for western blot to analyze Mov10 and HCV core protein levels, and loading control GAPDH. B, Cells expressing Mov10 were counted and plotted as a percent of the total number of cells. About 400–500 cells were counted per clone. In parallel, the same clones were infected with Jc1-378-1-Ypet (0.5 MOI) for 3 days and collected for flow cytometry to quantify the percentage of cells expressing NS5A-Ypet. Data are normalized to the parental cell line Huh7.5.1. C, Total RNA was isolated from the infected cells and analyzed by RT-qPCR for Mov10 and GAPDH mRNA levels. D, To determine the specific infectivity, supernatant was collected from clones following electroporation with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A). Total RNA was isolated from 200 μL filtered supernatants and analyzed for the number of RNA copies by RT-qPCR and 800 μL filtered supernatants were used to infect naïve Huh7.5.1 cells by limiting dilution assay. The TCID50/mL values were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Each data point represents average value of 3 individual experiments. Error bars represent SD. Statistical analysis was performed by using Student’s t-test (not significant (ns): P > .05, *P < .05, ***P < .001)

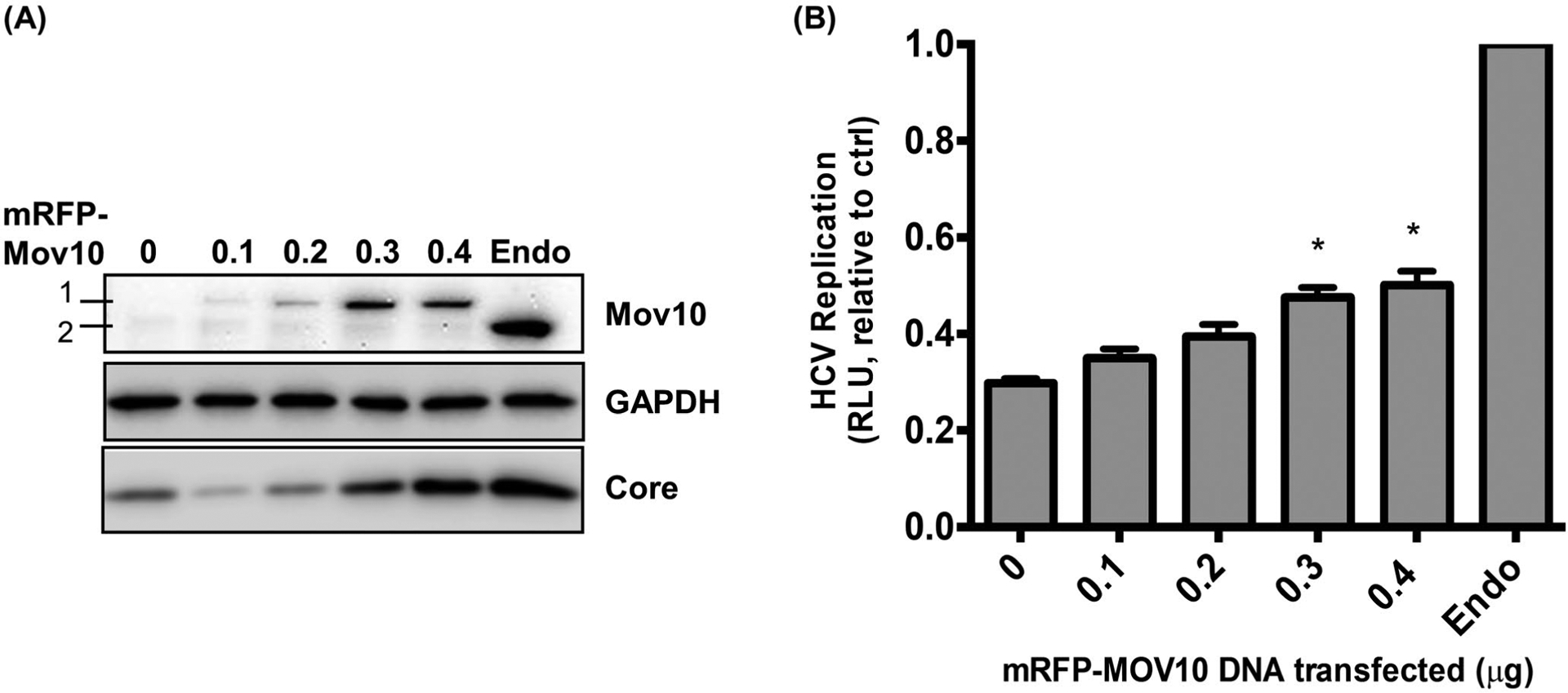

3.8 |. Rescue of HCV replication in Mov10 knockout cell lines

To determine whether the loss of HCV replication induced by knockout of Mov10 could be rescued by exogenous expression, Mov10 knockout clone D6 was electroporated with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A), then, transfected with varying amounts of mRFP-Mov10. At 72 hpt, cells were harvested and analyzed by western blotting. The mRFP-Mov10 can be differentiated from endogenous Mov10 by size and can be seen to increase concomitantly with the amount of expression vector transfected (Figure 8A). At the higher levels of mRFP-Mov10 expression, HCV core expression appears to be recovered. The cells were also analyzed for Gaussia luciferase production. Consistent with the western blot data, the luciferase expression was enhanced with increasing Mov10 (Figure 8B). In neither analysis was the rescue complete; however, incomplete rescue was expected, as the transfection efficiency observed in earlier experiments was approximately 50% under these conditions (Figure 2B,D).

FIGURE 8.

Rescue of HCV replication by exogenous expression of Mov10. D6 cells that have Mov10 suppressed by CRISPR/Cas9 were electroporated with Jc1-FLAG2(p7-nsGluc2A) RNA. A 16 hpe cells were transfected with varying amounts (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 μg) of an mRFP-Mov10 expression plasmid. A, 72 hpt cells were lysed and assayed for Mov10 expression and HCV core by western blot. A 1 is exogenous mRFP-Mov10 and 2 is endogenous Mov10. B, Cell culture media were assayed for Gaussia luciferase activity at 72 hpt. Data are normalized to the parental cell line Huh7.5.1. Each data point represents average value of 3 individual experiments. Error bars represent SD. Statistical analysis was performed by using Student’s t-test (*P < .05, **P < .01)

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the role of the P-body protein Mov10 on HCV infection. We have shown that overexpression of Mov10, and not of control P-body protein DCP1a, decreased viral RNA production in cells infected with fully infectious HCV. This decrease was also observed with a subgenomic replicon that circumvents early and late steps of HCV life cycle, including viral entry, assembly, and release. HCV produced in cells overexpressing Mov10 generated a lower yield of particles and with reduced specific infectivity, compared to virus produced in untreated cells, or cells overexpressing DCP1a. The reduced specific infectivity manifested in lower RNA and protein levels in newly infected cells, and consequently reduced HCV production from those cells.

Using confocal microscopy, we observe the HCV proteins NS5A and core to be present at viral replication, packaging, and assembly sites on cytosolic LD structures in the cytoplasm, as previously reported.54,57–59 These cellular compartments are made up of a phospholipid monolayer derived from outer endoplasmic reticulum, around a hydrophobic core of neutral lipids and cholesterol esters. Interestingly, HCV has been shown to hijack some P-body proteins during infection, redistributing them from P-bodies to LDs.20,53,55 Our study further shows that HCV infection results in clear changes in the subcellular distribution of Mov10. Whereas in uninfected cells endogenous Mov10 localizes in P-bodies in the cytoplasm, during HCV infection Mov10 changed to localize at and around LDs; as other P-body proteins have also been reported at LDs in HCV-infected cells,20,53,55 it is possible the P-bodies themselves are re-localized, however, we did not address that question specifically. Unlike other P-body proteins, Mov10 is not known to be essential for generation or turnover of P-bodies. Future studies may determine whether Mov10 has an effect on virus assembly and whether Mov10 overexpression results in aberrant HCV genome packaging that prevents efficient replication. As Mov10 overexpression suppresses intracellular HCV RNA levels, it is likely to also inhibit exosome-mediated transfer of HCV genomes,60,61 although we did not explicitly explore effects on exosomal transfer here. It is also possible that Mov10 perturbation could impact the distribution of HCV genomes between virions and exosomes, which could also contribute to apparent effects on the specific infectivity HCV.

It was shown that purified recombinant Mov10 has a 5′−3′ RNA helicase activity.62 Additionally, Mov10 has been reported to associate with HIV-1 RNA.33,35 Overexpression of the double mutant Mov10 protein R730A/N731A, which is deficient for RNA binding, does not inhibit HCV RNA replication and virus production. This failure to inhibit viral replication is not due to decreased levels of expression. The Mov10 double-mutant also failed to inhibit HIV-1 and was shown to have lost its ability to interact with HIV-1 RNA.35 Collectively, these results suggest that (i) the RNA binding ability of Mov10 is required for inhibition of both HIV-1 and HCV, and (ii) residues R730 and N731 are involved in and required for RNA binding, acting either directly on the viral RNA, or indirectly via interactions with host RNAs.

Early reports predicted Mov10 to have helicase activity based on the presence of ATP binding (residues 524 to 531) and unwinding motifs (residues 645 to 648). Recently, Mov10 was purified and shown to have a 5′−3′ unwinding activity.62 Moreover, it was demonstrated that ATP-binding and active site residues are required for the helicase function of Mov10. We tested whether the helicase activity of Mov10 interfered with RNA replication, possibly by disrupting double-stranded RNA intermediates or secondary structures of the viral RNA genome. Interestingly, both Mov10 mutants that were designed to impair the helicase function of Mov10 (DQAG and G527A) retained their antiviral properties against HCV, as they did with HIV-1.34,35 This suggests that the antiviral effect of Mov10 overexpression does not require helicase activity. Unlike WT Mov10, DQAG, and G527A, R730A/N731A Mov10 mutant does not colocalize with P-bodies (as shown by the decreased co-localization with P-body marker DCP2); instead, it is distributed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm of infected and uninfected cells and formed no foci at LDs or with HCV proteins.35 It was therefore possible that localization to P-bodies was required for inhibition of HCV; however, as Mov10 V866A lacks P-body localization, but retained its antiviral activity, localization to P-bodies is probably not a requirement for Mov10 inhibition of HCV infection.

Interestingly, we observed that decreasing Mov10 levels also decreased HCV infection levels, at both the protein and RNA level. The fact that both overexpression and ablation of Mov10 decreased HCV replication is intriguing, but not unique. Other groups have reported a similar finding for HIV-1 infection.33,34 Such pleiotropic effects may be in part due to the possible multi-functional nature of Mov10. Mov10 is a component of the RISC where it has been reported to interact with Ago2.40,63,64 Depletion of Mov10 affects microRNA-mediated repression of protein translation.65 Because HCV utilizes microRNAs (primarily miR-122) in complex with Ago2 in order to bind and stabilize its RNA,66–68 it is possible that a decrease in Mov10 levels disrupts the beneficial interactions of HCV RNA genome with Ago2 and miR-122 leading to a destabilization of HCV RNA and a decrease in infection levels.

Aside from the effects on viral infection, perturbation of Mov10 expression levels has conflicting effects on regulation of cellular mRNA. A recent study showed that Mov10 and Ago2 both bind the 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTRs) of some cellular mRNAs.69 That study found that when the two proteins bind at the same nucleic acid position, decreasing Mov10 expression levels increase Ago2 binding, resulting in suppression of the bound mRNA. Conversely, the two proteins can bind to the same RNA, but at distant positions. In this case, decreasing Mov10 expression levels decreases Ago2 binding, resulting in decreased repression of the bound mRNA. Both outcomes seemingly facilitated at least in part by the fragile X mental retardation protein. Studies to determine the interaction between Mov10, Ago2, and viral RNA, specifically the positions of the two proteins on the HCV genome, might provide insights into the multiple effects on HCV RNA replication we observed from overexpression vs knockdown of Mov10.

In conclusion, while the presence of Mov10 at proper levels during HCV infection is essential for efficient viral replication, both overexpression and suppression of Mov10 is detrimental HCV replication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr Charles Rice for reagents, Dr Robert Ralston for editing, discussions, and training contributions. This work was supported by NIH (R01 AI099284 and R01 AI121315).

Abbreviations:

- Ago2

Argonaute 2

- DCP1a

decapping enzyme 1A

- DAAs

direct-acting antiviral agents

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- h

hours

- hpe

hours post electroporation

- hpi

hours post infection

- hpt

hours post transfection

- IFN

interferon

- ISG

interferon-stimulated gene

- LDs

lipid droplets

- Mov10

Moloney leukemia virus 10

- NS

non-structural

- P-body

processing body

- RBV

ribavirin

- RISC

RNA interference signaling complexes

- WT

wild-type

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57:1333–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006;45:529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam R, McMaster P, O’Grady JG, et al. Evolution of liver transplantation in Europe: report of the European liver transplant registry. Liver Transplant. 2003;9:1231–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiesner RH, Sorrell M, Villamil F, and International Liver Transplantation Society Expert, P. Report of the first International Liver Transplantation Society expert panel consensus conference on liver transplantation and hepatitis C. Liver Transplant. 2003;9:S1–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M. Living donor liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis C virus cirrhosis: Tokyo experience. Clinical Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S122–S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. New Engl J Med. 2009;361:580–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeuzem S Interferon-based therapy for chronic hepatitis C: current and future perspectives. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:610–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu D, Ji J, Ndongwe TP, et al. Fast hepatitis C virus RNA elimination and NS5A redistribution by NS5A inhibitors studied by a multiplex assay approach. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:3482–3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGivern DR, Masaki T, Williford S, et al. Kinetic analyses reveal potent and early blockade of hepatitis C virus assembly by NS5A inhibitors. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(453–462):e457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Targett-Adams P, Graham EJ, Middleton J, et al. Small molecules targeting hepatitis C virus-encoded NS5A cause subcellular redistribution of their target: insights into compound modes of action. J Virol. 2011;85:6353–6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawlotsky JM. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C: current and future. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;369:321–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim CW, Chang KM. Hepatitis C virus: virology and life cycle. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19:17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moriishi K, Matsuura Y. Host factors involved in the replication of hepatitis C virus. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jangra RK, Yi M, Lemon SM. DDX6 (Rck/p54) is required for efficient hepatitis C virus replication but not for internal ribosome entry site-directed translation. J Virol. 2010;84:6810–6824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts APE, Doidge R, Tarr AW, Jopling CL The P body protein LSm1 contributes to stimulation of hepatitis C virus translation, but not replication, by microRNA-122, Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:1257–1269. 10.1093/nar/gkt941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheller N, Mina LB, Galao RP, et al. Translation and replication of hepatitis C virus genomic RNA depends on ancient cellular proteins that control mRNA fates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13517–13522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huys A, Thibault PA, Wilson JA. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA accumulation and translation by DDX6 and miR-122 are mediated by separate mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pager CT, Schutz S, Abraham TM, Luo G, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance and virus release by dispersion of processing bodies and enrichment of stress granules. Virology. 2013;435:472–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poenisch M, Metz P, Blankenburg H, et al. Identification of HNRNPK as regulator of hepatitis C virus particle production. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grunvogel O, Esser-Nobis K, Reustle A, et al. DDX60L is an interferon-stimulated gene product restricting hepatitis C virus replication in cell culture. J Virol. 2015;89:10548–10568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoggins JW, Rice CM. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1:519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horner SM Activation and Evasion of Antiviral Innate Immunity by Hepatitis C Virus, Journal of Molecular Biology. 2014;426:1198–1209. 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang D, Liu N, Zuo C, et al. Innate host response in primary human hepatocytes with hepatitis C virus infection. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao X, Ding Q, Lu J, et al. MDA5 plays a critical role in interferon response during hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2015;62:771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Israelow B, Narbus CM, Sourisseau M, Evans MJ. HepG2 cells mount an effective antiviral interferon-lambda based innate immune response to hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;60:1170–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itsui Y, Sakamoto N, Kurosaki M, et al. Expressional screening of interferon-stimulated genes for antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus replication. J Viral Hepatitis. 2006;13:690–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang D, Guo H, Xu C, et al. Identification of three interferon-inducible cellular enzymes that inhibit the replication of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2008;82:1665–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472:481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upadhyay A, Dixit U, Manvar D, Chaturvedi N, Pandey VN. Affinity capture and identification of host cell factors associated with hepatitis C virus (+) strand subgenomic RNA. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:1539–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abudu A, Wang X, Dang Y, Zhou T, Xiang SH, Zheng YH. Identification of molecular determinants from Moloney leukemia virus 10 homolog (MOV10) protein for virion packaging and anti-HIV-1 activity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1220–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burdick R, Smith JL, Chaipan C, et al. P body-associated protein Mov10 inhibits HIV-1 replication at multiple stages. J Virol. 2010;84:10241–10253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furtak V, Mulky A, Rawlings SA, et al. Perturbation of the P-body component Mov10 inhibits HIV-1 infectivity. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izumi T, Burdick R, Shigemi M, Plisov S, Hu W-S, Pathak VK Mov10 and APOBEC3G Localization to Processing Bodies Is Not Required for Virion Incorporation and Antiviral Activity, Journal of Virology. 2013;87:11047–11062. 10.1128/jvi.02070-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu C, Luo Z, Jager S, Krogan NJ, Peterlin BM. Moloney leukemia virus type 10 inhibits reverse transcription and retrotransposition of intracisternal a particles. J Virol. 2012;86:10517–10523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu T, Sun Q, Liu Y, Cen S, Zhang Q. The MOV10 helicase restricts hepatitis B virus replication by inhibiting viral reverse transcription. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:19804–19813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma YX, Li D, Fu LJ, et al. The role of Moloney leukemia virus 10 in hepatitis B virus expression in hepatoma cells. Virus Res. 2015;197:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puray-Chavez M, Farghali M, Yapo V, et al. Effects of Moloney Leukemia Virus 10 Protein on Hepatitis B Virus Infection and Viral Replication. Viruses. 2019;11:651 10.3390/v11070651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meister G, Landthaler M, Peters L, et al. Identification of novel argonaute-associated proteins. Curr Biol. 2005;15:2149–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallois-Montbrun S, Kramer B, Swanson CM, et al. Antiviral protein APOBEC3G localizes to ribonucleoprotein complexes found in P bodies and stress granules. J Virol. 2007;81:2165–2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fairman-Williams ME, Guenther UP, Jankowsky E. SF1 and SF2 helicases: family matters. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:313–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marukian S, Jones CT, Andrus L, et al. Cell culture-produced hepatitis C virus does not infect peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Hepatology. 2008;48:1843–1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309:623–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Y, Zhu S, Cai C, et al. High-throughput screening of a CRISPR/Cas9 library for functional genomics in human cells. Nature. 2014;509:487–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Han Y, Dang Y, et al. Moloney leukemia virus 10 (MOV10) protein inhibits retrovirus replication. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14346–14355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodier JL, Cheung LE, Kazazian HH Jr. MOV10 RNA helicase is a potent inhibitor of retrotransposition in cells. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blight KJ, McKeating JA, Rice CM. Highly permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Virol. 2002;76:13001–13014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adedeji AO, Singh K, Calcaterra NE, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication inhibitor that interferes with the nucleic acid unwinding of the viral helicase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4718–4728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirby KA, Marchand B, Ong YT, et al. Structural and inhibition studies of the RNase H function of xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus reverse transcriptase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:2048–2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ariumi Y, Kuroki M, Kushima Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus hijacks P-body and stress granule components around lipid droplets. J Virol. 2011;85:6882–6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyanari Y, Atsuzawa K, Usuda N, et al. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1089–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez-Vilaro G, Scheller N, Saludes V, Diez J. Hepatitis C virus infection alters P-body composition but is independent of P-body granules. J Virol. 2012;86:8740–8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niu J, Zhang B, Chen H. Applications of TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 in human cells and their potentials for gene therapy. Mol Biotechnol. 2014;56:681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barba G, Harper F, Harada T, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein shows a cytoplasmic localization and associates to cellular lipid storage droplets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1200–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boulant S, Vanbelle C, Ebel C, Penin F, Lavergne JP. Hepatitis C virus core protein is a dimeric alpha-helical protein exhibiting membrane protein features. J Virol. 2005;79:11353–11365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masaki T, Suzuki R, Murakami K, et al. Interaction of hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 5A with core protein is critical for the production of infectious virus particles. J Virol. 2008;82:7964–7976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dreux M, Garaigorta U, Boyd B, et al. Short-range exosomal transfer of viral RNA from infected cells to plasmacytoid dendritic cells triggers innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:558–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ramakrishnaiah V, Thumann C, Fofana I, et al. Exosome-mediated transmission of hepatitis C virus between human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13109–13113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gregersen LH, Schueler M, Munschauer M, et al. MOV10 Is a 5’ to 3’ RNA helicase contributing to UPF1 mRNA target degradation by translocation along 3’ UTRs. Mol Cell. 2014;54:573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chendrimada TP, Finn KJ, Ji X, et al. MicroRNA silencing through RISC recruitment of eIF6. Nature. 2007;447:823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wulczyn FG, Smirnova L, Rybak A, et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of the let-7 microRNA during neural cell specification. FASEB J. 2007;21:415–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu C, Zhang X, Huang F, et al. APOBEC3G inhibits microRNA-mediated repression of translation by interfering with the interaction between Argonaute-2 and MOV10. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29373–29383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Conrad KD, Giering F, Erfurth C, et al. MicroRNA-122 dependent binding of Ago2 protein to hepatitis C virus RNA is associated with enhanced RNA stability and translation stimulation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shimakami T, Yamane D, Jangra RK, et al. Stabilization of hepatitis C virus RNA by an Ago2-miR-122 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:941–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson JA, Zhang C, Huys A, Richardson CD. Human Ago2 is required for efficient microRNA 122 regulation of hepatitis C virus RNA accumulation and translation. J Virol. 2011;85:2342–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kenny PJ, Zhou H, Kim M, et al. MOV10 and FMRP regulate AGO2 association with microRNA recognition elements. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1729–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]