Abstract

Background:

CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) is introduced as an immune response modulator. The activity of CCR5 influences breast tumour development in a p53-dependent manner. This study aimed to investigate the frequency of CCR5delta32 and its association with the risk of breast cancer in 1038 blood samples in North East of Iran.

Methods:

In this case-control study, we genotyped 570 control samples and 468 breast cancer patients by a gel electrophoresis-based gap-polymerase chain reaction (gap-PCR) method Mashhad, Iran. The data were analyzed using the SPSS software.

Results:

Of 570 controls included, 542 (95.09%) had CCR5delta32 wild/wild (W/W) genotype, 28 samples (4.91%) had CCR5delta32 wild/deletion (W/D) genotype and none of them were CCR5delta32 deletion/deletion (D/D) genotype (0%). While 428 samples of patients (91.45%) had CCR5delta32 W/W genotype, 40 samples (8.55%) had CCR5delta32 W/D and CCR5delta32 D/D homozygous was nil (0%) amongst cases. All samples were in the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P>0.05). According to the allele frequency, D allele, as a risky allele, in the cases was more than the control samples (0.0427 vs 0.0245, respectively) (P=0.0206). Hence, W/D genotype may confer a risk effect (OR=1.77, CI: 1.09–2.90; P=0.0206) compared with WW genotype between case and control groups.

Conclusion:

There is a statistically significant association between CCR5W/D and breast cancer risk. CCR5 may be regarded as a target for the prevention of breast cancer in certain conditions such as interaction with p53 variants, which remains to be further investigated.

Keywords: CCR5delta32, p53 pathway, Breast carcinoma, Immunogenetics, Metastasis

Introduction

One of the most prevalent cancers in women is breast cancer, which increases the mortality rate in women worldwide (1, 2). Breast cancer is introduced as the most frequent malignancy in Iranian women (3, 4). Based on the previous studies, genetic and environmental factors are complicated in the risk as well as the expansion of breast cancer (5–9). A functional correlation exists between cancer and inflammation receptors. The inflammatory responses to the breast cancer tumor site proliferation and development of cancer cells are also involved in metastatic breast cancer (10, 11). In addition, inflammatory factors such as chemokine-like chemokine receptor (CCR5), which affect the chemotactic factors for inflammatory cells, have important roles in leukocyte trafficking, chemotaxis, angiogenesis, lymphocyte development, inflammatory processes, tumor development and metastasis (12).

Chemokines are small soluble molecules secreted by cells, which are greatly well-known for their ability to influence cancer cell development via inflammation and to motivate cellular migration, mostly by leukocyte recruitment in inflammation (13, 14). Moreover, different types of tumour cells express chemokine and chemokine receptors (15). In addition, high levels of CCR5 are great co-receptors for infection of macrophages and T lymphocytes via the macrophage-tropic strains of HIV-1; which their expression has been identified in cancer tissues. The CCR5 may be notably involved in the metastasis and proliferation of various cancers like breast cancer (16, 17). Inadequate and potent CCR5 expression is especially related to the non-metastatic progression of breast cancer. In addition, the local production of the Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5) is also significant in the development of breast tumour and associated with a poor prognosis of breast cancer (16, 17). CCR5 also results in the growth of breast cancer stem cells. Overexpression of the CCR5 cells indicates reduced p-γH2AX-Histone H2AX phosphorylation proteins, which alarms DNA damage and consequently leads to the enhancement of DNA repair (18). The deficiency of CCR5 affects the apoptotic cell death of melanoma via the prohibition of nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and upregulation of IL-1Ra (19). Moreover, the CCR5 expression has an important role in the subpopulation of breast cancer cell lines and affects the functional response to CCL5.

Furthermore, oncogene transformation enforces the expression of CCR5, and the subpopulation of cells, which express functional CCR5 shows enhanced the invading characteristic of the cancer cells. The role of CCR5 in breast tumour cell growth (mostly in luminal breast cancer), suggests it affects the p53 of the MCF-7 cells. Moreover, CCR5 blockade increases the proliferation of MCF-7 cell line in the attendance of p53 but does not affect the proliferation in the xenografts carrying a p53 mutation (20). Additionally, Vicriviroc or Maraviroc, known as the CCR5 antagonists, block the function of CCR5 HIV coreceptor and reduce metastasis of basal breast tumour, but does not affect the cell viability/proliferation in vitro. Maraviroc decreases pulmonary expansion of breast cancer in vivo. Moreover, the antagonists of CCR5 can be used as an adjuvant combination therapy to decrease the possibility of metastatic breast cancer in patients with certain conditions (21). Therefore, prevention of CCR5 via an antagonist decreases the leukocyte influence and tumor growth and subsequently reduces the subcutaneous transfusion of the cells in vivo (22). In addition, a decrease in CCR5 acts as a suppressive receptor in cancer metastasis. The deficiency of CCR5 increases the delay of tumor growth, and the inhibitors of CCR5 prevent a rise in the cancer cells in cancers like breast cancer (23, 24). CCR5delta32 (CCR5D32) has been found in the CCR5 gene, located on chromosome 3p21.3. CCR5D32 induces a strong resistance in homozygote persons against the HIV-1 infection. Moreover, studies have been done on the distribution of CCR5D32 in various populations (25). The effect of CCR5D32 polymorphism is dependent on the type of cancer; although, other studies have not reported the same association (26, 27).

This mutation was not present in Africans as well as most Asian people, but it was detectible in African-Americans, which the reason was explained as an ethnic combination (28, 29). The roles of the CCR5 receptor of chemokine CCL5 remain unclear in breast cancer progression and there is a controversy between articles. These variations might be due to the low statistical power, small sample size, clinical heterogeneity, ethnic difference, as well as the confounding effects that have not been taken into account.

In our study, we removed these limitations and tried to investigate the relation between CCR5D32 and the risks of breast cancer with an appropriate sample size in an Iranian population.

Materials and Methods

Study population and blood collection

In this case–control study, 468 clinically confirmed sporadic breast cancer patients were recruited in Mashhad, Iran. After taking informed consent, 10 ml peripheral blood sample was collected from 1038 individuals (468 cases and the 570 controls). The healthy female individuals were selected among women in the North East of Iran.

The genomic DNA extraction and genotyping

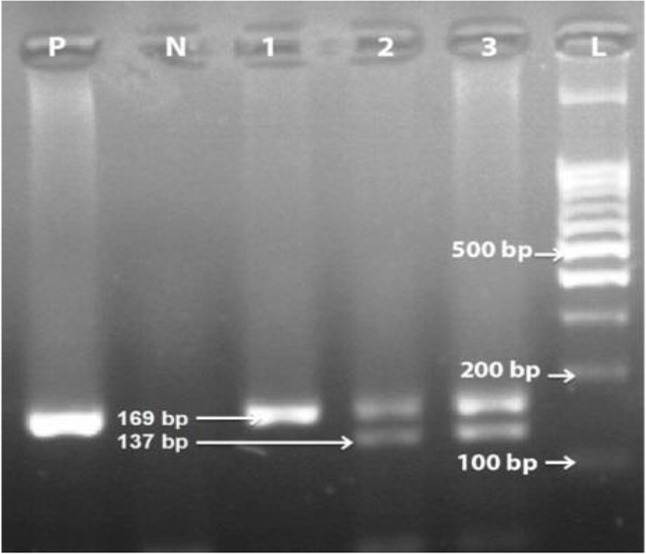

The pure genomic DNA was extracted from 1038 blood samples by the salting-out technique protocol (30, 31). The PCR was performed to identify the genotype of the cases and healthy controls by primers, which flank the 32- base pairs (bp) deletion. The reaction volume (10 μl) was composed of 5–10 ng of the genomic DNA template, 0.1 μM of each primer, 3 μl Master mix PCR mixture (2X) include 1.5 mM MgCl and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase in 2x reaction buffer (from 0.5U/μl) and 4 μl distilled water in the total reaction of 10 μl. The 5′ to 3′ sequence of common forward and reverse primers were as the following; forward primer sequence was 5′ AGG TCT TCA TTACAC CTG CAG C 3′, and reverse primer was 5′ CTT CTC ATT TCG ACACCG AAG C 3′ (Table 1) (32). Genotypes were detected according to the final size of PCR products, in which 169 bp and 137 bp products were related to wild-type and CCR5D32 genotypes, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1:

Primer sequences that used in this study

| Primers | Sequence 5′-3′ | Length | Products | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCR5W/W | CCR5D32 | |||||

| CCR5D/D | CCR5W/D | |||||

| Forward | AGG TCT TCA TTACAC CTG CAG C | 22 bp | 137 bp | 169 & 137 bp | ||

| Reverse | CTT CTC ATT TCG ACACCG AAG C | 22 bp | 169 bp | |||

Wild: W; Deletion: D; Bp: basepairs.

Fig. 1:

The gel electrophoresis of PCR amplified DNA. Lane 1: wild type (CCR5Wild/Wild); lanes 2 and 3: heterozygous genotype (CCR5Wild/Δ32). P: Positive control sample; N: Negative control sample; L: 100 bp DNA size marker

The reaction was performed in an Applied Biosystems PCR (Life Technologies). Under the following thermal conditions including first denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min; 33 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 58 °C for 30 sec, and also 72 °C for 30 sec; and last elongation at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The electrophoresis of PCR products (5–7 μl) was done in 3% agarose gel (Invitrogen), staining with DNA Green Viewer (Pars Tous; Iran) (Consort, Germany), and then they were visualized under UV light using SYNGENE U: genius gel documentation system.

The collected information was analyzed using the SPSS statistics software ver. 12 (Chicago, IL, USA). In addition, differences in the allele and the genotype frequencies of CCR5D32 variant between cases and healthy samples were evaluated using gene count and also the χ2 test. Moreover, Odd ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) using logistic regression test was calculated. In this study, for all analyses, the cut-off values of P≤0.05 were considered to be significant.

Ethical approval

Our study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki after being permitted via the local ethics committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Ethical code: IR.MUMS.fm.REC.1394.399). In this line, written informed consent has been received from all cases and controls.

Results

Demographic data of the patients and controls including age, living place, habits and situation, family history of cancer and clinical information were collected in a questionnaire (Table 2). Of 570 controls included, 542 (95.09%) had CCR5D32 wild/wild (W/W) genotype, 28 samples (4.91%) had CCR5D32 wild/deletion (W/D) genotype and none of them were CCR5D32 deletion/deletion (D/D) genotype (0%). While 428 samples of patients (91.45%) had CCR5D32 W/W genotype, 40 samples (8.55%) had CCR5D32 W/D and CCR5D32 D/D homozygous was nil (0%) amongst cases. All samples were in the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. According to the allele frequency, the frequency of D allele, as a risky allele, in the cases was more than the control samples (0.0427 vs 0.0245, respectively) (P=0.0206). Hence, W/D genotype risk effect was calculated as (OR=1.77, CI: 1.09–2.90; P=0.0206) compared with WW genotype (Table 3).

Table 2:

Summary of clinic-pathological data and several demographic variables of the carcinoma patients and the control groups

| Characteristics | N | Cases | N | Controls | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 359 | 51.6±11.6 | 536 | 42.5±12 | P<0.05* |

| BMI | 320 | 27.4±5 | 513 | 25.3±4.4 | P<0.05* |

| Height | 321 | 159.5±6.8 | 516 | 161.3±5.9 | P<0.05* |

| Weight | 344 | 69.7±13.2 | 529 | 66.2±11.7 | P<0.05* |

| Marital status | 897 | ||||

| Married | 331 (92.2%) | 461 (85.7%) | P<0.05* | ||

| Divorced | 3 (0.8%) | 1 (0.2%) | |||

| Widowed | 6 (1.7%) | 5 (0.9%) | |||

| Never-married | 19 (5.3%) | 71 (13.2%) | |||

| Abortion | 642 | ||||

| Yes | 117 (45.3%) | 115 (29.9%) | P<0.05* | ||

| No | 141 (54.7%) | 269 (70.1%) | |||

| The family history of cancer | 870 | ||||

| Yes | 192 (57.1%) | 371 (69.5%) | P<0.05* | ||

| No | 144 (42.9%) | 163 (30.5%) | |||

| History of cancer | 847 | ||||

| Yes | 23 (7.2%) | 4 (0.8%) | P<0.05* | ||

| No | 298 (92.8%) | 522 (99.2) |

Table 3:

Distribution of the CCR5D32 genotypes and the allelic frequencies

| Genotypes/Models/Alleles | Breast carcinoma | Normal individuals | OR (CI 95%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number () | ||||

| Genotypes | CCR5W/W | 428 (91.45) | 542 (95.09) | ||

| CCR5W/D | 40 (8.55) | 28 (4.91) | 1.77 (1.09–2.90) | 0.0206 | |

| CCR5D/D | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Alleles | W | 896 (95.72) | 1112 (97.54) | ||

| D | 40 (4.28) | 28 (2.46) | 1.77 (1.09–2.90) | 0.0206 | |

Wild: W; Deletion: D.

Discussion

In our study, there was a significant association between heterozygous genotype (W/D) and breast cancer risk in Iranian breast cancer patients. Moreover, D allele, as a risky allele, in the cases was more than the control samples.

The relation between genetic and environmental factors is widely investigated. In recent years, immunogenetics have an essential role in the pathogenesis of breast cancer. CCR5 is the receptor for chemotactic chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP1-α), MIP1β, and RANTES (CCL3, CCL4, CCL5). In addition, the CCR5D32 is located in the CCR5 promoter, which encodes a non-functional receptor (33, 34). Moreover, CCR5D32 allele has been shown to have a high frequency, among the different Caucasian populations (35, 36). A meta-analysis of an Indian population indicates that the CCR5D32 was associated with the risk of breast cancer (37). On the other hand, the CCR5D32 genotype has been correlated with better prognosis in patients of the Nijmegen discovery cohort with postmenopausal breast tumour (Nijmegen, Netherlands). The individuals, carrying the CCR5D32 genotype, demonstrate a longer metastasis-free survival (MFS) in this population (38).

In agreement with our investigation, in a meta-analysis study, the CCR5D32 was associated with the risk of breast cancer in the Indians (37). In the Netherlands population, the individuals carrying the CCR5D32, displayed a longer MFS in the postmenopausal subgroup of the initial cohort (38). In the Turkish population, the frequency of heterozygous genotypes was an independent risk factor for the breast cancer progression (39). In addition, another study reported a significant association between I/I and I/D alleles in the breast cancer patients with the CCR5D32 mutation; carried out with 500 breast cancer patient samples in a Pakistani population (40). Similar to our study, heterozygous genotype (W/D) in the breast patients was more than the control samples in a Pakistani population (41).

Furthermore, there was a strong association between the expressions CXCR5 in the breast cancer tissues from the German population (42). On the other hand, CCR5D32 was not connected to the risk of cancer (43). Moreover, in some studies, there was no significant correlation between this polymorphism and the risk of breast cancer such as in the North of India and Brazil (44–46).

CCR5 increases T cell responses to cancer cells via modulating the activation of helper-dependent CD8+ T cell (47). Besides, CCR5 exerts main regulatory effects on the immunity mediated by CD4 + - and CD8+ T cell. CCR5 has a particular, ligand-dependent role in improving anti-tumor responses. Efficient tumor rejection requires the expression of CCR5 via the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (48). Furthermore, CCR5 was found to be mainly expressed in the CD8+ T lymphocytes, and the frequency of CCR5+CD8+ Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) was higher in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), compared with the human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (48).

The activation of CCR5 in the CD4+ cells contributed to increasing the expression of CD40 ligand, resulting in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) maturation and improved CD8+ T-cell cross-priming as well as tumor infiltration. CCR5 leads to the reduction of chemical (3-methylcholanthrene)-induced fibrosarcoma growth and incidence in mice (47). The CCR5D32 has been associated with the lower expression of CCR5 and higher CC-chemokine secretion levels of CD4+ cells (49). In this respect and from the results of our study, the reduction in CCR5 leads to a decrease in the immune system defense against a tumour (especially a decrease in the T cell response).

Another explanation of our results may be related to the downstream pathways of the CCR5, as a protective factor for breast cancer. The activity of CCR5 regulates breast cancer development in a p53-dependent manner in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines (20). Mutation inactivates the p53 tumor suppressor gene in approximately half of all human tumors (50). Prevention of CCR5 expression leads to increase the proliferation of tumor cells in wild-type p53 without affecting the tumor cell proliferation in p53 mutation carriers in tumour xenograft models (20). In this line, the data from a breast cancer clinical study (547 patients in a cohort study) displayed that disease-free survival (DFS) was shorter in individuals carrying CCR5D32 allele and expressed wild-type p53. The activity of CCR5 affects breast cancer development in a p53-dependent manner. All downstream pathways of CCR5D/D and CCR5W/D are abolished or severely impaired in patients with CCR5D32, respectively. Consequently, activation of p53 mediated by CCR5 is diminished. In this line, p53, as a tumor suppressor, may be silenced in the CCR5D32 patients. Furthermore, two p38-dependent pathways, Gi and JAK2, help CCR5 to regulate p53 transcriptional activity. These p38-dependent pathways seem to be impaired/silenced in the participants with the CCR5D32 allele. Collectively, breast cancers with normal p53, grow quicker and relapse faster in the D32 carriers (20).

Conclusion

CCR5D32 may affect the risk of the breast cancer in our population. The potential use of CCL5/CCR5 may be a target for preventing breast cancer metastasis. In addition, it can be used as a marker of DNA damage/repair in the tumor cells. Thus, further functional studies are needed to investigate pathways related to the CCR5, p53 and T cell response influencing the risk of breast cancer.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was supported by the Student Research Committee of Mashhad University of science (Grant Numbers: 951734 & 961689).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wu JT, Kral JG. (2005). The NF-ϰB/IϰB signaling system: a molecular target in breast cancer therapy. J Surg Res, 123(1): 158–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turashvili G, Bouchal J, Burkadze G, Kolar Z. (2005). Differentiation of tumours of ductal and lobular origin: II. Genomics of invasive ductal and lobular breast carcinomas. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 149 (1): 63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashemi M, Fazaeli A, Ghavami S, et al. (2013). Functional polymorphisms of FAS and FASL gene and risk of breast cancer–pilot study of 134 cases. Plos One, 8 (1): e53075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashemi M, Eskandari-Nasab E, Fazaeli A, et al. (2012). Bi-directional PCR allele-specific amplification (bi-PASA) for detection of caspase-8− 652 6N ins/del promoter polymorphism (rs3834129) in breast cancer. Gene 505 (1): 176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tajbakhsh A, Javan FA, Rivandi M, et al. (2019). Significant association of TOX3/LOC643714 locus-rs3803662 and breast cancer risk in a cohort of Iranian population. Mol Biol Rep, 46(1):805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tajbakhsh A, Pasdar A, Rezaee M, et al. (2018). The current status and perspectives regarding the clinical implication of intracellular calcium in breast cancer. J Cell Physiol 233 (8): 5623–5641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tajbakhsh A, Mokhtari-Zaer A, Rezaee M, et al. (2017). Therapeutic Potentials of BDNF/TrkB in Breast Cancer; Current Status and Perspectives. J Cell Biochem 118 (9): 2502–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Easton DF, Pooley KA, Dunning AM, et al. (2007). Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature 447 (7148): 1087–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tajbakhsh A, Farjami Z, Darroudi S, et al. (2019). Association of rs4784227-CASC16 (LOC643714 locus) and rs4782447-ACSF3 polymorphisms and their association with breast cancer risk among Iranian population. EXCLI J, 18: 429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghilardi G, Biondi ML, La Torre A, et al. (2005). Breast cancer progression and host polymorphisms in the chemokine system: role of the macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)− 2518 G allele. Clin Chem 51 (2): 452–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaday GG, Peehl DM, Kadam PA, Lawrence DM. (2006). Expression of CCL5 (RANTES) and CCR5 in prostate cancer. Prostate 66 (2): 124–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eskandari-Nasab E, Hashemi M, Ebrahimi M, et al. (2014). Evaluation of CCL5-403 G> A and CCR5 Δ32 gene polymorphisms in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Biomark 14 (5): 343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rotondi M, Chiovato L. (2011). The chemokine system as a therapeutic target in autoimmune thyroid diseases: a focus on the interferon-γ inducible chemokines and their receptor. Curr Pharm Des 17 (29): 3202–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotondi M, Lazzeri E, Romagnani P, Serio M. (2003). Role for interferon-γ inducible chemokines in endocrine autoimmunity: an expanding field. J Endocrinol Invest 26 (2): 177–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X, Lee VC, Chevalier E, Hwang ST. (2009). Chemokine receptors as targets for cancer therapy. Curr Pharm Des 15 (7): 742–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bièche I, Lerebours F, Tozlu S, et al. (2004). Molecular profiling of inflammatory breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 10 (20): 6789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valdivia-Silva JE, Franco-Barraza J, Silva ALE, et al. (2009). Effect of pro-inflammatory cytokine stimulation on human breast cancer: implications of chemokine receptor expression in cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett 283 (2): 176–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiao XM, Velasco M, Li ZP, et al. (2016). CCR5 contributes to breast cancer stem cell expansion by enhancing DNA damage repair. Cancer Res 78 (7): 1657–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song JK, Park MH, Choi DY, et al. (2012). Deficiency of C-C chemokine receptor 5 suppresses tumor development via inactivation of NF-kappaB and upregulation of IL-1Ra in melanoma model. PLoS One, 7(5): e33747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mañes S, Mira E, Colomer R, et al. (2003). CCR5 expression influences the progression of human breast cancer in a p53-dependent manner. J Exp Med 198 (9): 1381–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velasco-Velázquez M, Jiao X, De La Fuente M, et al. (2012). CCR5 antagonist blocks metastasis of basal breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 72 (15): 3839–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson SC, Scott KA, Wilson JL, et al. (2003). A chemokine receptor antagonist inhibits experimental breast tumor growth. Cancer Res 63 (23): 8360–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng-Cashin J, Kuhns JJ, Burkett SE, et al. (2003). Host absence of CCR5 potentiates dendritic cell vaccination. J Immunol 170 (8): 4201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halama N, Zoernig I, Berthel A, et al. (2016). Tumoral Immune Cell Exploitation in Colorectal Cancer Metastases Can Be Targeted Effectively by Anti-CCR5 Therapy in Cancer Patients. Cancer Cell 29 (4): 587–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucotte G, Dieterlen F. (2003). More about the Viking hypothesis of origin of the Δ32 mutation in the CCR5 gene conferring resistance to HIV-1 infection. Infect Genet Evol 3 (4): 293–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucukgergin C, Isman FK, Dasdemir S, et al. (2012). The role of chemokine and chemokine receptor gene variants on the susceptibility and clinicopathological characteristics of bladder cancer. Gene, 511(1): 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zambra FMB, Biolchi V, Brum IS, Chies JAB. (2013). CCR2 and CCR5 genes polymorphisms in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Human Immunology 74 (8): 1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucotte G. (2002). Frequencies of 32 base pair deletion of the (Δ32) allele of the CCR5 HIV-1 co-receptor gene in Caucasians: a comparative analysis. Infect Genet Evol 1 (3): 201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrington M, Dean M, Martin MP, O’Brien SJ. (1999). Genetics of HIV-1 infection: chemokine receptor CCR5 polymorphism and its consequences. Hum Mol Genet 8 (10): 1939–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. (1988). A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res, 16 (3): 1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mardan-Nik M, Saffar Soflaei S, Biabangard-Zak A, et al. (2019). A method for improving the efficiency of DNA extraction from clotted blood samples. J Clin Lab Anal, 33 (6): e22892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandford AJ, Zhu S, Bai TR, et al. (2001). The role of the CC chemokine receptor-5 Δ32 polymorphism in asthma and in the production of regulated on activation, normal T cells expressed and secreted. J Allergy Clin Immunol,108 (1): 69– 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stone MJ, Hayward JA, Huang C, et al. (2017). Mechanisms of Regulation of the Chemokine-Receptor Network. Int J Mol Sci, 18 (2):342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Oliveira CE, Oda JM, Losi Guembarovsk R, et al. (2014). CC chemokine receptor 5: the interface of host immunity and cancer. Dis Markers, 2014: 126954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinson JJ, Chapman NH, Rees DC, et al. (1997). Global distribution of the CCR5 gene 32-basepair deletion. Nat Genet 16 (1): 100–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stephens JC, Reich DE, Goldstein DB, et al. (1998). Dating the origin of the CCR5-Δ32 AIDS-resistance allele by the coalescence of haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet 62 (6): 1507–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YH, Song GG. (2015). Association between chemokine receptor 5 delta32 polymorphism and susceptibility to cancer: A meta-analysis. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 35 (6): 509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Span PN, Pollakis G, Paxton WA, et al. (2015). Improved metastasis-free survival in nonadjuvantly treated postmenopausal breast cancer patients with chemokine receptor 5 del32 frameshift mutations. Int J Cancer, 136(1): 91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Degerli N, Yilmaz E, Bardakci F. (2005). The Δ32 allele distribution of the CCR5 gene and its relationship with certain cancers in a Turkish population. Clinical Biochemistry 38 (3): 248–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azhar A, Fatima F, Hameed A, Saleem S. (2015). Delta 32 mutation in CCR5 gene and its association with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol, 33 (28_suppl): 17. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fatima F, Saleem S, Hameed A, et al. (2019). Association analysis and allelic distribution of deletion in CC chemokine receptor 5 gene (CCR5Delta32) among breast cancer patients of Pakistan. Mol Biol Rep 46 (2): 2387–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panse J, Friedrichs K, Marx A, et al. (2008). Chemokine CXCL13 is overexpressed in the tumour tissue and in the peripheral blood of breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer 99 (6): 930–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ying HQ, Wang J, Gao XR. (2014). CCL5-403, CCR5-59029, and Delta32 polymorphisms and cancer risk: a meta-analysis based on 20,625 subjects. Tumour Biol 35 (6): 5895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banin-Hirata BK, Losi-Guembarovski R, Oda JMM, et al. (2016). CCR2-V64I genetic polymorphism: a possible involvement in HER2+breast cancer. Clin Exp Med 16 (2): 139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guleria K, Sharma S, Manjari M, et al. (2012). p.R72P, PIN3 Ins16bp Polymorphisms of TP53 and CCR5 Delta 32 in North Indian Breast Cancer Patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 13 (7): 3305–3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aoki MT, Do Amaral Herrera ACDS, Amarante MK, et al. (2009). CCR5 and p53 codon 72 gene polymorphisms: Implications in breast cancer development. Int J Mol Med 23 (3): 429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez-Martin A, Gomez L, Lustgarten J, et al. (2011). Maximal T Cell-Mediated Antitumor Responses Rely upon CCR5 Expression in Both CD4(+) and CD8(+) T Cells. Cancer Res 71 (16): 5455–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu JY, Li F, Wang LP, et al. (2015). CTL- vs T-reg lymphocyte-attracting chemokines, CCL4 and CCL20, are strong reciprocal predictive markers for survival of patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 113 (5): 747–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paxton WA, Neumann AU, Kang S, et al. (2001). RANTES production from CD4+ lymphocytes correlates with host genotype and rates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease progression. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 183 (11): 1678–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woods DB, Vousden KH. (2001). Regulation of p53 function. Exp Cell Res 264 (1): 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]