ABSTRACT

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA; encoded by Plau) is a serine proteinase that, in the central nervous system, induces astrocytic activation. β-Catenin is a protein that links the cytoplasmic tail of cadherins to the actin cytoskeleton, thus securing the formation of cadherin-mediated cell adhesion complexes. Disruption of cell–cell contacts leads to the detachment of β-catenin from cadherins, and β-catenin is then degraded by the proteasome following its phosphorylation by GSK3β. Here, we show that astrocytes release uPA following a scratch injury, and that this uPA promotes wound healing via a plasminogen-independent mechanism. We found that uPA induces the detachment of β-catenin from the cytoplasmic tail of N-cadherin (NCAD; also known as CDH2) by triggering its phosphorylation at Tyr654. Surprisingly, this is not followed by degradation of β-catenin because uPA also induces the phosphorylation of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6) at Ser1490, which then blocks the kinase activity of GSK3β. Our work indicates that the ensuing cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin is followed by its nuclear translocation and β-catenin-triggered transcription of the receptor for uPA (Plaur), which in turn is required for uPA to induce astrocytic wound healing.

KEY WORDS: Urokinase-type plasminogen activator, uPA, Plasmin, β-catenin, Wnt-β-catenin pathway, Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6

Summary: Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) triggers a switch from N-cadherin-induced cell adhesion to β-catenin cell signaling that promotes astrocytic wound healing.

INTRODUCTION

β-Catenin is the founding member of the armadillo (ARM) repeat protein superfamily (Valenta et al., 2012). It is assembled by a positively charged rigid central region with 12 imperfect ARM repeats flanked by two flexible N- and C-terminal domains (NTD and CTD) (Huber and Weis, 2001; Xing et al., 2003). Several partners share overlapping binding sites over the central region of β-catenin, and thus they cannot bind to it simultaneously. This exclusivity is crucial to switch from β-catenin having a structural role in the formation of cell–cell adhesion contacts (Ozawa et al., 1989), to it having a cell signaling function as the key effector of the Wnt pathway (Brown et al., 2003; Valenta et al., 2012). However, despite these considerations, the mechanisms underlying the transition between structural and cell signaling roles of β-catenin are not yet fully understood.

Cadherins are single-pass transmembrane glycoproteins that establish cell–cell contacts by engaging in Ca2+-dependent homotypic interactions with their extracellular domains (Geiger and Ayalon, 1992). Most of β-catenin is bound through its NTD to the cytoplasmic tail of cadherins, linking them to the actin cytoskeleton and thus securing the formation of cell–cell adhesion complexes (Yamada et al., 2005). The strength of the interaction between β-catenin and the cytoplasmic domain of cadherins is regulated by phosphorylation at multiple sites in both partners. For example, cadherin phosphorylation at Ser684, Ser686 and Ser692 strengthens the cadherin–β-catenin interaction (Huber and Weis, 2001; Sampietro et al., 2006), and β-catenin phosphorylation at Tyr654 by receptor tyrosine kinases and c-Src kinase (Coluccia et al., 2007) dramatically reduces its binding to cadherin.

Loss of cadherin-mediated cell adhesion prompts the release of β-catenin from cytoplasmic domain of cadherin. This is followed by β-catenin phosphorylation at Ser33, Ser37 and Thr41 by GSK3β bound to a cytoplasmic degradation complex assembled by the scaffold proteins axin and adenoma polyposis coli (APC) (Kimelman and Xu, 2006; Xing et al., 2003). In turn, phosphorylated β-catenin is ubiquitylated and degraded by the proteasome (Kitagawa et al., 1999). In contrast, binding of Wnt ligands to frizzled receptors and the low density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 (LRP5 and LRP6, collectively LRP5/6) prompts the binding of the protein dishevelled (Dvl) to the cytoplasmic domains of the frizzled–LRP5/6 complex (Bilic et al., 2007). This is followed by Dvl-mediated recruitment of the axin degradation complex, which in turn triggers the phosphorylation of LRP6 at Ser1490 (Bilic et al., 2007). Phosphorylated LRP6 then blocks GSK3β kinase activity (Zeng et al., 2008), thus abrogating GSK3β-induced β-catenin phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation, and instead facilitating its cytoplasmic accumulation and subsequent nuclear translocation. Once in the nucleus, β-catenin associates with DNA-binding transcription factors of the TCF/Lef family to activate Wnt-β-catenin-target genes (Cadigan and Waterman, 2012).

LRP6 is a single-pass transmembrane protein with an extracellular domain that mediates its interaction with Wnt ligands (Tamai et al., 2000), and an intracellular domain rich in proline, serine and threonine residues (Niehrs and Shen, 2010). Phosphorylation of LRP6 intracellular domain at Ser1490 is necessary and sufficient to stabilize β-catenin and activate Wnt signaling (Ahn et al., 2011; Bafico et al., 2001). Importantly, a growing body of experimental evidence indicates that mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are capable of phosphorylating the LRP6 intracellular domain independently of Wnt ligands binding to its extracellular domain (Cervenka et al., 2011).

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA, encoded by Plau) is a serine proteinase that upon binding to its receptor (uPAR, encoded by Plaur) catalyzes the conversion of plasminogen (Plg) into plasmin on the cell surface (Blasi and Carmeliet, 2002), and activates cell signaling pathways that promote cell adhesion, motility, proliferation, survival and invasion (Smith and Marshall, 2010). In line with these observations, uPA plays a central role in wound healing via a variety of plasminogen-dependent (Romer et al., 1996) and -independent (Carmeliet et al., 1998) mechanisms. The function of uPA in the central nervous system (CNS) is not fully understood. However, it is known that its expression in neurons and oligodendrocytes during development (Dent et al., 1993) is crucial for the formation of dendrites and synapses (Lino et al., 2014; Sumi et al., 1992). In the mature brain, uPA is abundantly found in astrocytes and synapses (Diaz et al., 2020), where it plays a central role in the regulation of astrocytic function (Diaz et al., 2019, 2017) and the repair of axons and synapses that have suffered different forms of injury (Diaz et al., 2020, 2017; Merino et al., 2017).

Here, we show that cerebral cortical astrocytes release uPA following a mechanical injury, and that binding of this uPA to uPAR promotes astrocytic wound healing via a mechanism modulated by plasminogen-activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1, also known as SERPINE1) but independent of plasmin generation. We found that uPA induces the phosphorylation of β-catenin at Tyr654 and its subsequent detachment from the intracellular domain of N-cadherin (NCAD, also known as CDH2). However, this is not followed by the degradation of β-catenin. Instead, our results indicate that uPA also triggers LRP6 phosphorylation mediated by ERK1- and -2 (ERK1/2, also known as MAPK3 and MAPK1, respectively), thus preventing GSK3β-induced phosphorylation of β-catenin. We found that this is followed by the cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin and its ensuing nuclear translocation, where it induces the expression of Wnt-regulated genes. Surprisingly, our data indicate that uPA-activated β-catenin signaling regulates the expression of the uPA receptor (uPAR), and that in turn uPAR is required for uPA to induce astrocytic wound healing. In summary, here we describe a novel role for uPA as activator of Wnt-β-catenin signaling, with important translational implication for neurorepair.

RESULTS

uPA promotes astrocytic wound healing via a plasminogen-independent mechanism

First, we used live microscopy to study the healing of a monolayer of wild-type (Wt) astrocytes following a scratch injury. We found that astrocytes begin to repopulate the wounded area 24 h after the injury (arrows in Fig. 1A), and that this is accompanied by an increase in the concentration of uPA in the culture medium (Fig. 1B). To study whether the observed release of uPA is associated with the repopulation of the wounded zone, we quantified the wounded area covered by astrocytes, as depicted by the red lines in the lower panel of Fig. 1C, 24 h after a scratch injury to a monolayer of Wt and uPA−/− astrocytes. Our data indicate that the repopulation of the wounded area is decreased in monolayers of uPA−/− astrocytes (Fig. 1D; 73.47±16.38% mean±s.d. growth compared to Wt astrocytes; n=10, P=0.002; two-tailed Student's t-test). To study the in vivo relevance of these findings, we quantified the area of the wound populated by astrocytes 72 h after a mechanical injury to the frontal cortex of Wt and uPA−/− mice. Our results confirmed the in vivo translatability of our in vitro observations, as they revealed that genetic deficiency of uPA impairs the ability of astrocytes to occupy the injured cortex (Fig. 1E,F).

Fig. 1.

uPA promotes astrocytic growth following a mechanical injury. (A) Representative live micrographs (10× objective magnification) of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes 0 and 24 h after a mechanical injury. White arrows in lower panel depict examples of zones of astrocytic growth in previously injured areas. (B) Mean concentration of uPA (ng/ml) in the culture medium of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes either left intact (control, C) or 24 h after a mechanical injury (I). n=7 (C) and n=6 (I). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (C) Representative live micrographs (10× objective magnification) of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes 0 and 24 h after a mechanical injury. Red lines depict the border of the wounded area immediately after the injury (upper panel) and the area of growth (lower panel) 24 h later. (D) Growth of a monolayer of Wt (n=8) and uPA−/− astrocytes (n=10) 24 h after a mechanical injury. Results are presented as percentage growth of the monolayer of uPA−/− astrocytes compared the growth of the Wt monolayer. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (E) Representative confocal micrographs viewed at 60× objective magnification of GFAP and Hoechst 33259 expression in the frontal cortex of Wt and uPA−/− mice 72 h after a mechanical injury. Scale bars: 50 μm. (F) GFAP-immunoreactive area per 4500 µm2 of cerebral cortex of Wt and uPA−/− mice (n=4) at 72 h after a mechanical injury. Each dot represents the average GFAP-positive area quantified in 5 micrographs per animal. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. (G) Growth of a monolayer of Wt and uPA−/− astrocytes 24 h after a mechanical injury and treatment with 5 nM of uPA [n=15 (Wt) and n=19 (uPA−/−)] or vehicle [control, n=15 (Wt) and n=19 (uPA−/−)]. Results are presented as percentage compared to growth of Wt astrocytes treated with vehicle (control). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. (H) Representative confocal micrographs viewed at 60× objective magnification of the injured border of two astrocytic monolayers stained with Hoechst 33259 (blue) and anti-KI67 antibodies (green) 24 h after a mechanical injury and treatment with vehicle (control; panels a,c) or 5 nM of uPA (panels b,d). White squares in panels a,b depict examples of KI67-positive astrocytes electronically magnified 10× in panels c,d. Scale bars: 100 μm (top panels), 20 μm (bottom panels). (I) Percentage of KI67-positive astrocytes in relation to the total number of cells in the injured border of astrocytic monolayers from four different cultures subjected to the experimental conditions described in H. Each dot represents the average value for each individual culture. n=221 (control) and 358 cells (uPA-treated). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (J) Growth of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes 24 h after a mechanical injury and treatment with vehicle (control; n=9), or 5 nM of uPA (n=11), or 100 nM of AraC (n=10), or a combination of uPA and AraC (n=12). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test. (K) Astrocytic migration (µm/24 h) following a mechanical injury to a monolayer of Wt astrocytes in the presence of vehicle (control; n=14 cuts) or 5 nM of uPA (n=15 cuts). Each dot represents the average migration of 5 cells in the injured border. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (L) Astrocytic migration through a 5 μm pore insert following 24 h of treatment with 5 nM of uPA or a comparable volume of vehicle (control). Values are given as percentage of cells in the underside of the insert in relation to the number of cells in the upper side, normalized to values in vehicle (control)-treated cells. n=5 inserts assembled with astrocytes from three different cultures. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. In all box plots, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the range.

To study the effect of recombinant uPA on astrocytic healing, we quantified the repopulation of the wounded area 24 h after a mechanical injury to monolayers of Wt and uPA−/− astrocytes, alone or in the presence of 5 nM of uPA. We found that recombinant uPA promotes the repopulation of both Wt and uPA−/− astrocytic monolayers (Fig. 1G). Importantly, our confocal microscopy studies revealed that treatment with uPA does not induce cell proliferation in the injured border, as denoted by a lack of increase in the number of KI67 (MKI67)-positive cells (Fig. 1H,I). In line with these observations, the effect of uPA on astrocytic wound healing was not abrogated by inhibition of cell proliferation with cytosine arabinoside (AraC; Fig. 1J), but instead was associated with the migration of injured astrocytes into the wounded area (Fig. 1K). To further characterize this effect, we quantified the migration of astrocytes through 5 μm pore size inserts after 24 h of treatment with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control). These experiments revealed that uPA effectively triggers astrocytic migration (Fig. 1L). Additionally, the findings that uPA induces the healing of a monolayer of Plg−/− astrocytes (Fig. 2A), and that the N-terminal fragment of uPA (ATF, which contains the growth factor-like and kringle uPA domains but not its proteolytic domain; Fig. 2B), but not plasmin (Fig. 2C) also promotes the healing of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes following a mechanical injury, indicate that uPA-induced astrocytic wound healing does not require the conversion of Plg into plasmin. Finally, because PAI-1 modulates cell adhesion and motility by a mechanism that is independent of its protease inhibitory role (Kjoller et al., 1997), we decided to quantify cell migration into the wounded area following a scratch injury to monolayers of Wt and PAI-1−/− astrocytes. Our data indicate that compared to Wt astrocytes, astrocytic migration is increased in PAI-1−/− astrocytes (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

uPA promotes astrocytic healing via a plasminogen-independent mechanism. (A) Growth of a monolayer of Wt and Plg−/− astrocytes 24 h after a wound injury and treatment with 5 nM of uPA [n=27 (Wt) and 27 (Plg−/−)] or vehicle [control; n=37 (Wt) and 39 (Plg−/−)]. Results are presented as percentage compared to growth of Wt astrocytes treated with vehicle (control). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (B) Growth of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes 24 h after a wound injury and treatment with vehicle (control, C, n=11) or 5 nM of uPA ATF (n=14). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (C) Growth of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes 24 h after a wound injury and treatment with vehicle (control, C, n=19) or 100 nM of plasmin (n=21). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (D) Growth of a monolayer of PAI-1−/− astrocytes (n=13) 24 h after a wound injury. Results are presented as percentage compared to growth of a monolayer of astrocytes prepared from Wt littermate controls (n=22) exposed to similar experimental conditions. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. In all box plots, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the range.

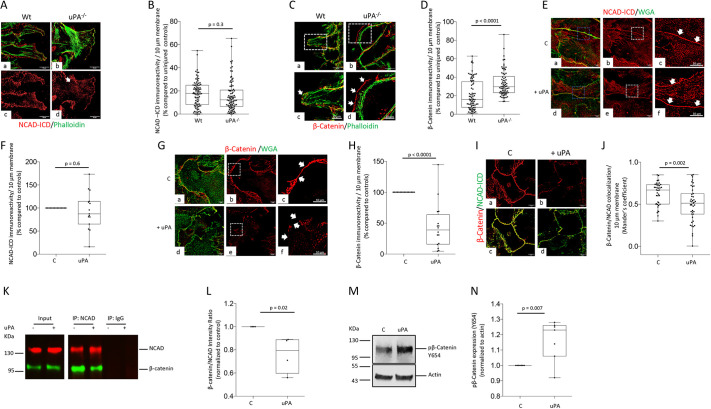

uPA triggers the detachment of β-catenin from the intracellular domain of NCAD

Because NCAD regulates the directionality of astrocytic healing (Dupin et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2012), we decided to study its expression in astrocytes wounded by a scratch injury. However, since its extracellular domain (NCAD-ECD) is damaged by the mechanical insult (Kanemaru et al., 2013), we studied the expression of its intracellular domain (NCAD-ICD) in the membrane of cells growing into the wounded area of a monolayer of Wt and uPA−/− astrocytes 24 h after a scratch injury. Additionally, because β-catenin binds to NCAD-ICD, we performed similar observations with an antibody against β-catenin. Our data indicate that compared to uninjured controls, the scratch injury decreases the abundance of NCAD and β-catenin in the astrocytic membrane. However, while the effect of the mechanical injury on the expression of NCAD-ICD was similar in both groups of cells (Fig. 3A,B; n=90 per group. P=0.3, two-tailed Student's t-test), the decrease in the abundance of β-catenin was significantly attenuated in monolayers of uPA−/− astrocytes (Fig. 3C,D; n=79 cells/group; two-tailed Student's t-test).

Fig. 3.

uPA triggers the detachment of β-catenin from the intracellular domain of N-cadherin. (A) Representative confocal micrographs (viewed at 400×) from the wounded border of a monolayer of Wt (panels a,c) and uPA−/− astrocytes (panels b,d) stained with phalloidin (green) and antibodies against the intracellular domain of N-cadherin (NCAD-ICD; red) 24 h after a mechanical injury. Scale bars: 20 μm. (B) NCAD-ICD immunoreactivity per 10 μm of membrane of cells located in the wounded border of a monolayer of Wt (n=90) and uPA−/− (n=90) astrocytes 24 h after a mechanical injury. Results are presented as NCAD-ICD immunoreactivity per 10 μm of membrane compared to NCAD-ICD immunoreactivity in uninjured astrocytes. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (C) Representative confocal micrographs (viewed at 400×) from the wounded border of a monolayer of Wt (panels a,c) and uPA−/− astrocytes (panels b,d) stained with phalloidin (green) and anti-β-catenin antibodies (red) 24 h after a mechanical injury. Panels c,d correspond to a 2.5× electronic magnification of the area depicted with dashed squares in a,b. Arrows in c,d depict β-catenin-immunoreactive areas on the cell surface. Scale bars: 20 μm (top panels), 10 μm (bottom panels). (D) β-catenin immunoreactivity per 10 μm of membrane of cells along the wounded border of a monolayer of Wt (n=79) and uPA−/− (n=74) astrocytes 24 h after a mechanical injury. Results are presented in relation to β-catenin immunoreactivity in uninjured astrocytes. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (E–H) Representative confocal micrographs viewed at 400× (E,G) of monolayers of uninjured Wt astrocytes treated for 30 min with vehicle (control; C) or 5 nM of uPA, and then stained with WGA (green) and antibodies against either NCAD-ICD (red in E) or β-catenin (red in G). Panels c,f in E,G correspond to a 2.5× electronic magnification of the areas demarcated by the dashed squares in b,e. Arrows in c,f denote membrane staining for NCAD-ICD (E) or β-catenin (G). F,H correspond to NCAD-ICD (F) and β-catenin immunoreactivity (H) on the plasma membrane of uninjured Wt astrocytes treated with vehicle (control; n=15 cells from three different cultures) or 5 nM of uPA (n=15 cells from three different cultures). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. Scale bars: 20 μm (E, a,b,d,e; G, a,b,d,e), 10 μm (E, c,f; G, c,f). (I) Representative confocal micrographs (viewed at 400×) of a monolayer of uninjured Wt astrocytes immunostained with antibodies against NCAD-ICD (green) and β-catenin (red) following 30 min of treatment with vehicle (control, C, panels a,c) or 5 nM of uPA (panels b,d). Scale bars: 20 μm. (J) β-catenin/NCAD colocalization per 10 μm of membrane (Mander's coefficient) in a monolayer of uninjured Wt astrocytes incubated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control, C). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (K,L) Extracts prepared from Wt astrocytes incubated during 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control) were immunoprecipitated with anti-NCAD and IgG antibodies and immunoblotted with antibodies against either β-catenin or NCAD. L depicts the ratio for β-catenin:NCAD intensity of the band in four observations per experimental group. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (M,N) Representative western blot analysis (M) and mean intensity of the band (N) of β-catenin phosphorylated at Tyr654 (pβ-catenin) in Wt astrocytes incubated for 15 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control). n=7. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. In all box plots, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the range.

Because the scratch injury induces the release of uPA (Fig. 1B), and since β-catenin interacts with NCAD-ICD (Geiger et al., 1995), we then asked if the attenuation of the effect of the scratch injury on the abundance of β-catenin on the membrane of uPA−/− astrocytes is caused by uPA-induced disruption of the β-catenin–NCAD-ICD interaction. To test this hypothesis, first we used confocal microscopy to study the expression of NCAD-ICD and β-catenin on the plasma membrane of uninjured astrocytes treated for 30 min with vehicle (control) or 5 nM of uPA. These studies revealed that, compared to vehicle (control)-treated cells, uPA decreases the abundance of β-catenin but not NCAD-ICD on the astrocytic membrane (Fig. 3E–H). Furthermore, we found that uPA treatment decreases the colocalization of NCAD-ICD and β-catenin on the astrocytic membrane (Fig. 3I,J). To further characterize these observations, extracts prepared from cells from both experimental groups were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against NCAD and immunoblotted with anti-β-catenin antibodies. We found that uPA induces the detachment of β-catenin from NCAD-ICD (Fig. 3K,L). Importantly, phosphorylation of β-catenin at Tyr654 reduces its binding to NCAD-ICD, and our data with extracts of Wt astrocytes prepared after 30 min of treatment with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control) indicate that uPA induces the phosphorylation of β-catenin at that tyrosine residue (Fig. 3M,N).

uPA inhibits the cytoplasmic degradation of β-catenin

Because β-catenin undergoes proteasomal degradation following its detachment from NCAD-ICD (MacDonald et al., 2009), we then decided to study its abundance in whole-cell extracts prepared from Wt astrocytes treated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or its ATF, or with a comparable volume of vehicle (control). Surprisingly, we found that uPA not only induces the detachment of β-catenin from NCAD-ICD from the astrocytic membrane (Fig. 3G,H), but increases its abundance in whole-cell extracts (Fig. 4A,B) by a mechanism that does not require plasmin generation (Fig. 4C,D).

Fig. 4.

uPA inhibits the degradation of β-catenin. (A–F) Representative western blot analyses (A,C,E) and quantification of the intensity of the band (B,D,F) of total β-catenin (A–D), and active β-catenin (E,F) in Wt astrocytes incubated for 30 min (A,C), or for 0, 15 and 30 min (E) with vehicle (control, C) or 5 nM of either uPA (A,E) or its ATF (C). n=5 (B,D) and n=6 (F). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was performed in B,D; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test in F. (G) Mean growth of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes 24 h after a mechanical injury and treatment with vehicle (control; n=17), or 5 nM of uPA (n=25), or a combination of 5 nM of uPA and 1 μM of XAV-939 (n=24), or with XAV-939 alone (n=19). Results are presented as percentage of growth of wounded vehicle (control)-treated Wt astrocytes. Two-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak's multiple comparisons test. In all box plots, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the range.

When the Wnt-β-catenin pathway is inactive, GSK3β bound to a cytoplasmic inhibitory complex phosphorylates β-catenin at Ser33, Ser37 and Thr41, thereby prompting its ubiquitiylation and proteasomal degradation. In contrast, Wnt-β-catenin pathway activation promotes the cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin by rendering GSK3β inactive (Kikuchi et al., 2006). Thus, to investigate whether the observed increase in the abundance of β-catenin following uPA treatment is mediated by inhibition of its degradation prompted by GSK3β-induced phosphorylation at Ser33, Ser37 and Thr41, we studied the expression of β-catenin that is not phosphorylated at Ser37 or Thr41 (active β-catenin) in Wt astrocytes treated for 0–30 min with 5 nM of uPA. We found that uPA abrogates GSK3β-induced phosphorylation of β-catenin as denoted by an increase in the abundance of active β-catenin in uPA-treated astrocytes (Fig. 4E,F). To investigate whether the observed increase in active β-catenin mediates uPA-induced astrocytic wound healing, we used live-cell microscopy to quantify the regrowth of cells into the wounded area of a monolayer of Wt astrocytes 24 h after a scratch injury and treatment with either vehicle (control), or 5 nM of uPA, alone or in combination with 1 μM of XAV-939 [a Wnt-β-catenin pathway inhibitor that promotes GSK3β-induced β-catenin phosphorylation (Huang et al., 2009; Stakheev et al., 2019)]. Our results indicated that active β-catenin mediates the observed effect of uPA on astrocytic wound healing (Fig. 4G).

uPA induces ERK1/2-mediated LRP6 phosphorylation

Our data indicate that uPA increases the abundance of β-catenin by preventing its phosphorylation by GSK3β, which denotes Wnt-β-catenin pathway activation. Because phosphorylation of the transmembrane receptor LRP6 at Ser1490 (pLRP6) is necessary and sufficient to activate the Wnt-β-catenin pathway (He et al., 2004), we then decided to study its abundance in extracts prepared from Wt and uPAR−/− astrocytes treated for 15 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control). These experiments revealed that uPA induces the phosphorylation of LRP6 at Ser1490 in Wt but not uPAR−/− astrocytes (Fig. 5A–D). ERK1/2 phosphorylates LRP6 independently of Wnt ligands (Cervenka et al., 2011) and our previous studies show that ERK1/2 mediates the effect of uPA on astrocytic activation (Diaz et al., 2017). In line with these observations, we found that ERK1/2 inhibition with SL327 abrogates uPA-induced LRP6 phosphorylation (Fig. 5E,F).

Fig. 5.

uPA induces LRP6 phosphorylation. (A–F) Representative western blot analyses (A,C,E) and the corresponding quantification of the mean intensity of the band (B,D,F) of LRP6 phosphorylated at Ser1490 (pLRP6) in Wt (A,C,E) and uPAR−/− astrocytes (C) incubated for 15 min with uPA or vehicle (control), alone or in the presence of 10 μM of the ERK 1/2 inhibitor SL327 (E,F). n=5 (B) and n=6 (D,F). Data are compared in each experiment to pLRP6 expression in Wt astrocytes treated with vehicle (control). Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. In all box plots, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the range.

uPA induces the nuclear translocation of β-catenin

Because, after escaping its degradation in the cytoplasm, phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser675 promotes its nuclear translocation and signaling activity (Heuberger and Birchmeier, 2010), we then studied the abundance of β-catenin phosphorylated at serine 675 in extracts prepared from Wt astrocytes treated with uPA or vehicle (control). Our data revealed that uPA induces the phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser675 (Fig. 6A,B), and western blot analyses with nuclear and cytosolic extracts indicate that this is followed by its nuclear translocation (Fig. 6C,D). Importantly, uPA-induced nuclear translocation of β-catenin (indicative of Wnt-β-catenin pathway activation) was confirmed by confocal microscopy with cultured astrocytes treated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control; Fig. 6E,F).

Fig. 6.

uPA induces the nuclear translocation of β-catenin. (A,B) Representative western blot analyses (A) and quantification of the intensity of the band (B) of β-catenin phosphorylated at Ser675 in Wt astrocytes treated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control). n=5. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (C) Representative western blot analysis of β-catenin, GAPDH and histone-3 expression in cytosolic (Cyt) and nuclear (N) extracts prepared from Wt astrocytes treated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control). (D) β-catenin expression normalized to histone-3 expression in nuclear extracts prepared from Wt astrocytes exposed to the experimental conditions described in C. n=7. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (E) Panels a and d are representative confocal micrographs viewed at 60× objective magnification of β-catenin expression (green) in Wt astrocytes treated for 30 min with vehicle (control; panel a) or 5 nM of uPA (panel d). Panels b, c, e and f correspond to a 2.5× magnification of the area depicted by the dashed squares in a,d. Blue in b,e is Hoechst 33259. Arrows in c,f depict the absence (c) or presence (f) of β-catenin in the nucleus. Scale bars: 20 μm. (F) β-catenin-immunoreactive area in nuclei of Wt astrocytes treated for 30 min with vehicle (control; n=58 cells from three different cultures) or 5 nM of uPA (n=57 cells from three different cultures). Results are presented as percentage compared to vehicle (control)-treated cells. Mann–Whitney U test. In all box plots, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the range.

uPA regulates the expression of its own receptor via Wnt-β-catenin activation

To further investigate the effect of uPA on Wnt-β-catenin signaling, we studied the expression of Myc mRNA, a Wnt-β-catenin regulated gene (Rennoll and Yochum, 2015), in Wt astrocytes treated for 24 h with uPA, alone or in the presence of XAV-939. Furthermore, because studies with colorectal cell lines have shown that the Wnt-β-catenin pathway regulates the expression of the uPA receptor (uPAR), we also decided to study the expression of Plaur mRNA. We found that uPA increases the expression of Myc and Plaur mRNA (Fig. 7A–C) via Wnt-β-catenin pathway activation (Fig. 7D–F). In line with these results, our results show that uPA increases the abundance of uPAR protein in Wt astrocytes (Fig. 7G,H). The importance of these findings was underscored by the observation that the effect of endogenous and recombinant uPA on astrocytic wound healing is mediated by its binding to uPAR (Fig. 7I).

Fig. 7.

uPA induces β-catenin signaling. (A,D) Representative RT-PCR analyses of Myc (c-myc), Plaur and Actb mRNA expression in Wt astrocytes treated 24 h with 5 nM of uPA, or a comparable volume of vehicle (control), or with a combination of uPA and 1 μM of XAV-939, or with 1 µM of XAV-939 alone. (B,C,E,F) Mean Myc (B,E) and Plaur (C,F) mRNA expression, normalized to Actb mRNA expression and compared to the corresponding mRNA expression in vehicle (control)-treated Wt astrocytes. n=4 per experimental condition. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (B,C) and two-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak's multiple comparisons test (E,F). (G,H). Representative western blot analysis (G) and quantification of the intensity of the band (H) of uPAR expression in Wt astrocytes treated for 24 h with 5 nM of uPA or a comparable volume of vehicle (control). n=4. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. (I) Growth of a monolayer of Wt and uPAR−/− astrocytes 24 h after a mechanical injury and treatment with 5 nM of uPA. Results are presented as percentage of growth compared to vehicle (control)-treated Wt astrocytes. n=32 (Wt treated with vehicle-control), n=43 [uPAR−/− treated with vehicle (control)], n=11 (uPA-treated Wt) and n=15 (uPA-treated uPAR−/−). Two-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak's multiple comparisons test. In all box plots, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the range.

DISCUSSION

Astrocytes play a crucial role in the repair of the damaged CNS (Whalley, 2019). Indeed, following an injury to the brain, astrocytes become migratory by a sequence of genetic, biochemical and morphological changes (Gao et al., 2013). This process, known as astrogliosis, has been linked to wound healing (Suzuki et al., 2012) and the repair of synapses damaged by different forms of injury (Diaz et al., 2019, 2017; Diaz and Yepes, 2018). Our previous studies indicate that uPA promotes astrocytic activation in the CNS (Diaz et al., 2019, 2017). Here, we report that uPA-induced cell migration from the injured border, instead of uPA-induced cell proliferation, is required for the repair of a monolayer of astrocytes that have suffered a scratch injury. Noticeably, we found that this effect does not require plasmin generation and is modulated by PAI-1. Our observations agree with earlier studies showing that uPA induces astrogliosis (Diaz et al., 2019, 2017), and that PAI-1 regulates non-proteolytic functions of uPA (Wind et al., 2002). Significantly, in contrast with results obtained in experimental models of cutaneous injuries (Sulniute et al., 2016), our data show that uPA promotes astrocytic wound healing by a mechanism independent of plasmin generation, which agrees with reports of uPA-induced cell migration via a catalytic-independent mechanism (Carriero et al., 2011; Carriero and Stoppelli, 2011). Moreover, our data support the notion that the reported ability of uPA–uPAR binding to trigger epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Gupta et al., 2011) mediates its effect on astrocytic wound healing. Furthermore, the work presented here indicates that uPA–uPAR binding activates the Wnt-β-catenin pathway through its ability to phosphorylate the intracellular domain of LRP6, thus abrogating GSK3β-mediated inactivation of β-catenin. We show that by increasing the abundance of uPAR on the membrane, the subsequent nuclear translocation of β-catenin promotes the repair of a monolayer of astrocytes that have suffered a mechanical injury.

NCAD is a type I cadherin crucial for the formation of astrocytic cell–cell contacts (Hara et al., 2017). NCAD has a juxtamembrane domain that binds to p120 catenin, and a C-terminal domain that binds to β-catenin (Pokutta and Weis, 2007). In turn, β-catenin interacts with α-catenin, which, by binding to actin, links NCAD to the astrocytic cytoskeleton (Yamada et al., 2005). The interaction of β-catenin with NCAD is pivotal for NCAD-mediated cell–cell adhesion (Shih and Yamada, 2012), and in line with these observations, disruption of the β-catenin–NCAD interaction results in loss of structural integrity of NCAD-based cell junctions (Valenta et al., 2012). The strength of the interaction between β-catenin and NCAD is regulated by phosphorylation of different residues in NCAD and β-catenin. Of particular interest is the fact that phosphorylation of Tyr654 in the last ARM repeat of β-catenin reduces its binding to cadherin (Piedra et al., 2001). Significantly, we found that although uPA does not have an effect on the abundance of the membrane-bound NCAD intracellular domain, it induces the phosphorylation of β-catenin at Tyr654, thus prompting the detachment of the β-catenin–NCAD complex.

The cytoplasmic release of β-catenin prompts its phosphorylation by GSK3β at Ser33, Ser37 and Thr41 by GSK3β, which in turn triggers its recognition by β-Trcp, an E3 ubiquitin ligase subunit that causes its ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation (He et al., 2004; MacDonald et al., 2009). Surprisingly, we found that uPA-induced detachment of β-catenin from NCAD was not followed by its cytoplasmic degradation. Instead, we detected an increase in the abundance of β-catenin in uPA-treated astrocytes. In line with these observations, our experiments show that uPA blocks GSK3β-induced degradation of β-catenin, as denoted by an increase in the abundance of β-catenin that is not phosphorylated at Ser37 or Thr41 (active β-catenin) in uPA-treated astrocytes. The functional relevance of these findings is underscored by the finding that pharmacological induction of GSKβ-triggered degradation of β-catenin with XAV-939 abrogates uPA-induced astrocytic wound healing. Importantly, although previous studies with an animal model of pleural injury have shown that uPA induces the nuclear translocation of β-catenin (Boren et al., 2017), to our knowledge this is the first report indicating that uPA has a direct inhibitory effect on the activity of GSK3β, more specifically on its ability to induce the phosphorylation and ensuing degradation of β-catenin.

Our studies reveal that uPA not only triggers the detachment of β-catenin from NCAD, but also inhibits its cytoplasmic degradation and prompts its nuclear translocation. Together, these results indicate that uPA activates the Wnt-β-catenin pathway in astrocytes. This agrees with work by others indicating that uPA activates Wnt-β-catenin signaling in a medulloblastoma cell line (Asuthkar et al., 2012). Phosphorylation of the intracellular domain of LRP6 at Ser1490 is necessary and sufficient to activate the Wnt-β-catenin pathway (Ahn et al., 2011; Bafico et al., 2001). We found that uPA triggers the phosphorylation of LRP6 at Ser1490, and that this effect requires its binding to uPAR and is mediated by ERK1/2. Because MAPKs phosphorylate the intracellular domain of LRP6 independently of Wnt ligands (Cervenka et al., 2011), then it is plausible to postulate that the formation of an uPA–uPAR–LRP6 complex leads to ERK1/2-induced phosphorylation of LRP6 independently of Wnts binding to its extracellular domain. However, at this point we do not know if uPAR forms a complex with LRP6, if uPA induces the release of Wnt ligands or if the release of Wnts is required for uPA to trigger LRP6 phosphorylation.

It has been reported that the cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin is not sufficient to induce its nuclear translocation, but instead that Rac1 needs to be activated for β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus (Wu et al., 2008). Our previous studies indicate that uPA activates Rac1 (Merino et al., 2017). However, we do not know if uPA-induced Rac1 activation is also required for the observed increase in the abundance of β-catenin in the nucleus of uPA-treated astrocytes, or if the nuclear translocation of β-catenin is just a consequence of its increased cytoplasmic accumulation caused by uPA.

The TCF/Lef family of DNA-bound transcription factors is the main partner of β-catenin in the nucleus. When the Wnt-β-catenin pathway is inactive, TCF inhibits gene expression by interacting with the Groucho (or TLE) repressor family of proteins. In contrast, Wnt-β-catenin pathway activation leads to binding of β-catenin to TCF proteins, which in turn displaces Groucho proteins and recruits transcriptional co-activators (Daniels and Weis, 2005). Importantly, β-catenin needs to be phosphorylated at Ser675 to facilitate the recruitment of transcriptional co-activators (van Veelen et al., 2011), and our studies show an increase in the abundance of β-catenin phosphorylated at Ser675 in uPA-treated astrocytes. These data indicate that uPA not only induces the nuclear translocation of β-catenin but also promotes its signaling activity. The functional relevance of our findings is supported by the observation that β-catenin signaling is required for astrocytic wound healing (Yang et al., 2012).

The Wnt-β-catenin pathway is activated by wound healing, and β-catenin signaling is crucial for tissue regeneration (Whyte et al., 2012, 2013). In agreement with these observations, a growing body of experimental evidence indicates that Wnt signaling is required for the proliferative phase of the healing process in different experimental systems (Sansom et al., 2007). However, to our knowledge this is the first report indicating that Wnt signaling is required for the healing of the mature CNS. Myc is a Wnt-regulated gene (Cadigan and Waterman, 2012; Ramakrishnan and Cadigan, 2017), and our data indicate that uPA induces its expression in cerebral cortical astrocytes via activation of β-catenin signaling. Previous reports reveal that β-catenin binding to TCF/Lef transcription factors induces the expression of uPAR gene (Plaur) in a colorectal carcinoma cell line (Mann et al., 1999). Here, we show that uPA-induced β-catenin signaling induces the expression of Plaur in cerebral cortical astrocytes, and that uPAR is required for uPA to induce astrocytic wound healing.

In summary, our data reveal a role for uPA as mediator of a crosstalk between NCAD and the Wnt-β-catenin pathway (Fig. 8). More specifically, we show that uPA activates the switch from β-catenin-mediated cell adhesion to β-catenin signaling, and that by triggering the expression of its own receptor (uPAR), uPA-triggered β-catenin signaling induces astrocytic repair. This is a novel role for uPA in the CNS with important translational implications for the treatment of the injured brain.

Fig. 8.

Proposed model of uPA-induced astrocytic healing. (A) The homophilic interaction between the extracellular domains of N-cadherin (NCAD-ECD), and the binding of β-catenin to the intracellular domain of NCAD (NCAD-ICD) mediate the formation of cell–cell contacts in a monolayer of uninjured astrocytes. (B–D) A mechanical injury that disrupts the interaction between the extracellular domains of NCAD (B) triggers the release of uPA. Binding of this uPA to its receptor (uPAR) induces the phosphorylation of β-catenin at Tyr654, thus prompting its detachment from NCAD-ICD (C). Simultaneously, uPA–uPAR binding-induced phosphorylation of the LRP6 intracellular domain (LRP6-ICD) at Ser1490, prompts the membrane recruitment of GSK3β, thus abrogating its ability to phosphorylate β-catenin. This not only allows β-catenin to escape proteasomal degradation, but also promotes its cytoplasmic accumulation and subsequent nuclear translocation, whereupon binding to TCF/Lef transcription factors triggers the expression of the uPA receptor (Plaur). Finally, by inducing the migration of cells from the injured border, the resultant increase in the abundance of uPAR on the plasma membrane promotes the healing of the wounded zone (D).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and reagents

Animals were 8–12-week-old male wild-type (Wt) mice and animals used were deficient on uPA (uPA−/−), uPAR (uPAR−/−), plasminogen (Plg−/−) or plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1−/−), or were their Wt littermate controls, and were all on a C57BL/6J background. Cultures and animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (IACUC) of Emory University, Atlanta GA. Experiments were reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines for how to report animal experiments. The ELISA assay for uPA, and recombinant plasmin, murine uPA and its N-terminal fragment (ATF) were purchased from Molecular Innovations (Novi, MI; Cat. # MUPAKT-TOT, # MPLM, # MUPA and # MATF, respectively). Other reagents were XAV-939 and the ERK1/2 inhibitor SL327 (Tocris Bioscience; Cat. # 3748 and # 1969, respectively; Minneapolis, MN), six-well hanging Millicell culture inserts (MilliPore, Burlington, MA; Cat # MCMPO6H48), and antibodies against the intracellular domain of N-cadherin (NCAD-ICD. Abcam; Cat. # ab76057; Cambridge, MA), Normal IgG rabbit and histone H3 (Cell Signaling; Cat. # 2729 and 4499, respectively; Danvers, MA), β-catenin (BD Biosciences; Cat. # 610153; San Jose, CA), rat KI67, donkey anti-rabbit-IgG Alexa 594, donkey anti-mouse-IgG Alexa Fluor 594, goat anti-mouse-IgG Alexa Fluor 488, and goat anti-rabbit-IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat. # 14-5698-81, # A21207, # A21203, # A11017 and # A11008, respectively; Grand Island, NY), β-catenin phosphorylated at Ser675 and LRP6 phosphorylated at Ser1490 (Cell Signaling; Cat. # 4176 and # 2568, respectively; Danvers, MA), uPAR and β-catenin phosphorylated at Tyr654 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Cat. # SC-10815 and # SC-57533, respectively; Dallas, TX), β-catenin non-phosphorylated at Ser37/Thr41 (active β-catenin; Millipore; Cat. # 1620112 and # 05-665, respectively; Burlington, MA), and IRDye 800CW donkey anti-mouse-IgG, IRDye 680RD donkey anti-mouse-IgG, IRDye 680RD donkey anti-rabbit-IgG, IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG1, and Intercept (TBS) Blocking bBuffer (Li-Cor; Cat. # 926-32212, # 926-68072, # 926-68073, # 926-32213, and # 927-60001, respectively; Lincoln, NE). RIPA buffer was from TEKNOVA (Cat. # R3792, Hollister, CA). NP-40 buffer, sample buffer 5×, Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, ProLong gold antifade, 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), Dynabeads Protein G, Alexa Fluor 488–phalloidin, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin, Ultra Pure Agarose, and mouse anti-β-actin were purchased from ThermoFisher (Cat. # FNN0021, # 1859594, # 23225, # P36930, # J64655, # 10004D, # A12379, # W11261, # 16500-500, and # A1978, respectively). 1-β-D-Arabinofuranosylcytosine (AraC), mouse anti-GAPDH, and DMSO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat. # 251010, #MAB374, and #A-1163-1, respectively). EmeraldAMp Max HS PCR master mix was from Takara Bio USA (Cat. # RR330A; Mountain View, CA). The iScript cDNA Synthesis kit was from Millipore (Cat. # 1708891). Primers for Myc (forward 5′-CTGTGGAGAAGAGGCAAACC-3′, reverse 5′-TGTTGCTGATCTGCTTCAGG-3′), PLAUR (forward 5′-TCATCAGCCTGACAGAGACC-3′, reverse 5′-AGCTCCTTTCTGTGCTCTGG-3′) and Actb (forward 5′-ACTGGGACGACATGGAGAAG-3′, reverse 5′-GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA-3′) were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa).

Astrocytic cultures

Wt, uPA−/−, uPAR−/−, Plg−/− and PAI-1−/− astrocytes were cultured as described elsewhere from 1-day-old mice (Diaz et al., 2019). Briefly, the cerebral cortex was dissected, transferred into Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10 mM HEPES, and incubated in trypsin containing 0.02% DNase at 37°C for 15 min. Tissue was triturated, resuspended in 10% FBS-supplemented DMEM, filtered through a 70 μm pore membrane and plated onto poly-l-lysine coated T75 flasks. Upon reaching confluency 10–14 days later, astrocytes were plated and used for individual experiments.

Scratch injury model

For the induction of a mechanical injury in vitro, monolayers of astrocytes cultured as described above were scratched with a p20 pipette tip and treated with either 5 nM of uPA or its ATF, or 100 nM of plasmin, or 1 μM of XAV-939, or a combination of uPA and either XAV-939, or 10 μM of the ERK1/2 inhibitor SL327, or 100 nM of AraC. Then cells were placed in a 37°C incubator (Tokai Hit, Japan) with a gas mixture of 5% CO2, 21% O2, and 74% N2, attached to a DP80 camera of a live microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Images were taken at 10× objective magnification at the beginning of the experiment (time 0) and 24 h later. To quantify wound healing, a 500 μm line was drawn over the edge of the injured site at time 0 using the drawing tool of the Olympus CellSens Dimension 1.17 software. This line was copied and pasted onto the same XY coordinates 24 h later and the borders of astrocytes growing into the wounded area were outlined. The resultant area was measured and normalized to the area quantified in monolayers of Wt astrocytes treated with vehicle (control) after the scratch injury. For the induction of mechanical injury in vivo, Wt and uPA−/− mice (n=4 each) were placed on a stereotactic frame and a 2 mm long, 0.5 mm deep, cortical injury was performed with the tip of a Hamilton syringe at 1 mm lateral between bregma +1 mm and bregma −1 mm (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001). Brains were harvested 72 h later, cut onto 20 µm coronal sections and stained with the nuclear marker Hoechst 33259 and anti-GFAP antibodies (dilution).

Quantification of astrocytic migration

To quantify cell migration we used two different models. In the first, individual nuclei were identified along the wounded border immediately after the induction of a mechanical injury to monolayers of control- and uPA-treated Wt astrocytes (n=14 monolayers in each experimental group). The migration of each cell into the wounded area was followed over 24 h with a straight line and quantified with live microscopy and the Olympus CellSens Dimension 1.17 software. In the second model, equal number of astrocytes were seeded onto six-well hanging Millicell culture inserts. Upon reaching confluency 2 weeks later, cells were scraped from the underside of the insert and the upper side was treated during 24 h with either vehicle control or 5 nM uPA. Inserts were then washed with PBS and cells in the upper and underside were resuspended in 500 μl of trypsin during 5 min. Then, 500 μl of cell culture medium was added, samples were collected and centrifuged at 1500 g at 4°C, supernatants were discarded, pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of culture medium, and cells were counted with a hemocytometer. Values are expressed as a percentage of cells in the underside of the insert in relation to the number of cells in the upper side, and normalized to percentages obtained in control-treated inserts.

Immunocytochemistry

To study the expression of NCAD and β-catenin, monolayers of Wt and uPA−/− astrocytes were fixed 24 h after a scratch injury. To investigate the effect of uPA on the expression of β-catenin and its colocalization with the intracellular domain of NCAD, monolayers of uninjured Wt astrocytes were treated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control). To study the effect of uPA on astrocytic proliferation, monolayers of Wt astrocytes were fixed 24 h after a scratch injury and treatment with 5 nM of uPA or a comparable volume of vehicle (control). At the end of either 30 min or 24 h, cells were fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed, permeabilized, blocked with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 3% BSA in TBS, and incubated overnight at 4°C with either a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the intracellular domain of NCAD (1:400), an anti β-catenin monoclonal antibody (1:400), or an anti-KI67 rat monoclonal IgG2a antibody, separately or in combination, followed by incubation with donkey anti-rabbit-IgG Alexa 594 antibody (1:500), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse-IgG antibody (1:500), goat anti-rabbit 33342 Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:500) or Alexa Fluor 488–phalloidin (1:500). Coverslips were mounted using ProLong gold antifade mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY). Pictures from the wounded edge and a representative zone in the unwounded area were obtained at 400× magnification with a Fluoview FV10i automated confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) with a pinhole at 1 UA. To quantify the expression of either NCAD or β-catenin, a line was drawn over the cell membrane, and the mean intensity of each channel was quantified with the ImageJ software. To determine NCAD and β-catenin colocalization, the Mander's coefficient was obtained with the software OLYMPUS CellSens Dimension 1.17. To quantify the effect of uPA on the expression of NCAD-ICD and β-catenin on the cell membrane, and on the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, astrocytes treated for 30 min with either vehicle (control) or 5 nM of uPA were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated for 15 min with 5 μg/ml of the membrane marker wheat germ agglutinin- Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (WGA), followed by treatment with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 3% BSA for 20 min (to study the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, in this step samples were incubated 10 min with 1 M HCl), overnight incubation with either mouse anti-β-catenin (1:1000) or rabbit anti-NCAD-ICD (1:1000) antibodies, treatment with Hoechst 33259 and either Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:500) or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (1:500). Pictures were taken at 60× objective magnification with a Fluoview FV10i automated confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) with NA 1.35 oil, pinhole 1 UA (50 µm), and 1024×1024 pixels resolution. The abundance of NCAD-ICD and β-catenin was studied along a line traced over the WGA-demarcated membrane, and results were expressed as percentage of values in vehicle (control)-treated astrocytes. To quantify the nuclear translocation of β-catenin, we used the CellSens dimension 1.17 software to measure the area immunoreactive to β-catenin antibodies in regions of interest drawn around each Hoechst 33259-positive nucleus. To quantify astrocytic proliferation, 60× objective magnification micrographs were taken over the injured border and the number of Hoechst 33259- and KI67-positive astrocytes was counted along a 900 μm line drawn with the Olympus CellSens Dimension 1.17 tool. Values are expressed as percentage of KI67-positive cells in relation to the total number of Hoechst 33259-positive astrocytes.

Immunohistochemistry

To quantify the expression of GFAP in the cerebral cortex following a mechanical injury, brains of Wt and uPA−/− mice (n=4 per strain) were harvested 72 h after a cortical injury, performed as described above, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 10% sucrose and PBS for 2 h, cut onto 30 μm coronal slices, and permeabilized for 1 h with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 3% BSA. Slices were then incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-GFAP antibodies (1:1000), and then washed and incubated with a mixture of Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies (1:500) and Hoechst 33259 (1:5000). Micrographs from a 45,000 μm2 area surrounding the wound and a comparable area in the uninjured cortex were taken at 60× objective magnification with a Fluoview FV10i automated confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). The GFAP immunoreactive area was quantified in each micrograph using CellSens dimension 1.17 Olympus software.

Quantification of uPA concentration in the culture medium

Monolayers of Wt astrocytes underwent a scratch injury as described above. After 24 h, the medium was collected and centrifuged at 21,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and mouse uPA total antigen was measured with an ELISA following the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR

RNA was extracted with a Rneasy mini kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and quantified with a Nanodrop system from Wt cerebral cortical astrocytes treated for 24 h with 5 nM of uPA, 1 μM of XAV-939, or a combination of uPA and XAV-939. cDNA was prepared from 500 ng of RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit. Then, a PCR product to detect Myc, Plaur or Actb was generated with a MultiGene OptiMax Thermal Cycler [72°C×2 min; 30 cycles of 98°C×10 s, 60°C×30 s, 72°C×20 s, and 72°C×10 min (Labnet International, Edison, NJ)], an EmeraldAMp Max HS PCR master mix, and the primers described above. The amplified PCR product was detected with a 2% agarose gel and measured with the LI-COR Odyssey Fc reader and IMAGE STUDIO ver 5.2 (Li-Cor Lincoln, NE).

Isolation of nuclear and cytosolic extracts

Wt astrocytes were incubated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control). Cells were washed with PBS and centrifuged at 1600 g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in a hypotonic buffer containing 10 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl and 1 mM DTT, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors, incubated in ice for 10 min, homogenized with a Pyrex homogenizer with 1 ml volume capacity and centrifuged for 10 min at 3400 g. The supernatant containing the cytosol was saved, and the pellet was resuspended in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 20% glycerol, 0.42 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors before centrifugation for 30 min at 21,000 g. Supernatants containing nuclear and cytosolic extracts were used for western blot analysis.

Western blot analyses

Wt and uPAR−/− cerebral cortical astrocytes were incubated for 0–30 min with 5 nM of uPA or its ATF, or a comparable volume of vehicle (control), or a combination of uPA and 10 μM of the ERK1/2 inhibitor SL327. Nuclear extracts were isolated, as described above, from Wt astrocytes treated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or a comparable volume of vehicle (control). At the end of each time point, cells were homogenized with RIPA buffer and equal amounts of proteins were loaded into mini-protean TGX stain-free 4-15% gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer in TBS (Li-Cor Lincoln, NE). Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against NCAD (1:2000), total β-catenin (1:2000), β-catenin phosphorylated at Ser675 (1:2000), LRP6 phosphorylated at Ser1490 (1:1000), or uPAR (1:1000), active-β-catenin (1:1000), β-catenin phosphorylated at Tyr654 (1:100), β-actin (1:50,000) or histone-3 (1:1000). Membranes were then washed and incubated with either one of the following secondary antibodies prepared at a 1:10,000 dilution: IRDye 800CW donkey anti-rabbit-IgG, IRDye 800CW donkey anti-mouse-IgG, IRDye 680RD donkey anti-mouse-IgG, IRDye 680RD donkey anti-rabbit-IgG or IRDye 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG1. Infrared signal was detected and measured with LI-COR Odyssey Fc reader and IMAGE STUDIO version 5.2 (Li-Cor Lincoln, NE). Values were expressed as a ratio compared with β-actin and normalized to intensity detected in extracts prepared from untreated cells.

Immunoprecipitation

Wt cerebral cortical astrocytes treated for 30 min with 5 nM of uPA or vehicle (control) were homogenized in 1000 µl of NP-40 buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Then, 1000 µg were precleared for 1 h with 2 µg of anti-IgG normal antibody and 20 µl of Dynabeads Protein G in a volume of 1500 µl under rotation at 4°C. Beads were removed using magnetic force, samples were split into volumes of 700 µl and incubated overnight at 4°C with 2 µg of antibodies against either NCAD or IgG normal. Samples were then incubated with 50 µl of Dynabeads Protein G for 2 h, washed, and eluted with 30 μl of 2× loading buffer at 95°C for 10 min. Equal volumes of each sample were loaded and analyzed with immunoblotting using antibodies against NCAD and β-catenin as above. Results are given as a ratio of β-catenin:NCAD signal intensity in uPA-treated cells over β-catenin:NCAD signal intensity in vehicle (control)-treated astrocytes.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 6 software with an unpaired Student's t-test and one- or two-way ANOVA with corrections as deemed appropriate and described in each figure legend. P-values of <0.05 were considered as significant.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.Y.; Methodology: A.D., C.M.-J., E.T.; Formal analysis: M.Y.; Investigation: A.D., C.M.-J., Y.X., P.M., Y.W., M.Y.; Writing - review & editing: M.Y.; Supervision: M.Y.

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant NS-091201 (to M.Y.), Office of Patient Care Services, Department of Veterans Affairs MERIT award IO1BX003441 (to M.Y.), and American Heart Association post-doctoral fellowship grant 19POST34380009 (to A.D.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Peer review history

The peer review history is available online at https://journals.biologists.com/jcs/article-lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.255919

References

- Ahn, V. E., Chu, M. L.-H., Choi, H.-J., Tran, D., Abo, A. and Weis, W. I. (2011). Structural basis of Wnt signaling inhibition by Dickkopf binding to LRP5/6. Dev. Cell 21, 862-873. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asuthkar, S., Gondi, C. S., Nalla, A. K., Velpula, K. K., Gorantla, B. and Rao, J. S. (2012). Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR)-mediated regulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling is enhanced in irradiated medulloblastoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 20576-20589. 10.1074/jbc.M112.348888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bafico, A., Liu, G., Yaniv, A., Gazit, A. and Aaronson, S. A. (2001). Novel mechanism of Wnt signalling inhibition mediated by Dickkopf-1 interaction with LRP6/Arrow. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 683-686. 10.1038/35083081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilic, J., Huang, Y.-L., Davidson, G., Zimmermann, T., Cruciat, C.-M., Bienz, M. and Niehrs, C. (2007). Wnt induces LRP6 signalosomes and promotes dishevelled-dependent LRP6 phosphorylation. Science 316, 1619-1622. 10.1126/science.1137065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, F. and Carmeliet, P. (2002). uPAR: a versatile signalling orchestrator. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 932-943. 10.1038/nrm977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boren, J., Shryock, G., Fergis, A., Jeffers, A., Owens, S., Qin, W., Koenig, K. B., Tsukasaki, Y., Komatsu, S., Ikebe, M.et al. (2017). Inhibition of Glycogen synthase Kinase 3β blocks mesomesenchymal transition and attenuates streptococcus pneumonia–mediated pleural injury in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 187, 2461-2472. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. C., Mark, K. S., Egleton, R. D., Huber, J. D., Burroughs, A. R. and Davis, T. P. (2003). Protection against hypoxia-induced increase in blood-brain barrier permeability: role of tight junction proteins and NFκB. J. Cell Sci. 116, 693-700. 10.1242/jcs.00264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan, K. M. and Waterman, M. L. (2012). TCF/LEFs and Wnt signaling in the nucleus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a007906. 10.1101/cshperspect.a007906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet, P., Moons, L., Dewerchin, M., Rosenberg, S., Herbert, J.-M., Lupu, F. and Collen, D. (1998). Receptor-independent role of urokinase-type plasminogen activator in pericellular plasmin and matrix metalloproteinase proteolysis during vascular wound healing in mice. J. Cell Biol. 140, 233-245. 10.1083/jcb.140.1.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriero, M. V. and Stoppelli, M. P. (2011). The urokinase-type plasminogen activator and the generation of inhibitors of urokinase activity and signaling. Curr. Pharm. Des. 17, 1944-1961. 10.2174/138161211796718143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriero, M. V., Franco, P., Votta, G., Longanesi-Cattani, I., Vento, M. T., Masucci, M. T., Mancini, A., Caputi, M., Iaccarino, I. and Stoppelli, M. P. (2011). Regulation of cell migration and invasion by specific modules of uPA: mechanistic insights and specific inhibitors. Curr. Drug Targets 12, 1761-1771. 10.2174/138945011797635777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervenka, I., Wolf, J., Masek, J., Krejci, P., Wilcox, W. R., Kozubik, A., Schulte, G., Gutkind, J. S. and Bryja, V. (2011). Mitogen-activated protein kinases promote WNT/β-catenin signaling via phosphorylation of LRP6. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 179-189. 10.1128/MCB.00550-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccia, A. M. L., Vacca, A., Duñach, M., Mologni, L., Redaelli, S., Bustos, V. H., Benati, D., Pinna, L. A. and Gambacorti-Passerini, C. (2007). Bcr-Abl stabilizes β-catenin in chronic myeloid leukemia through its tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 26, 1456-1466. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, D. L. and Weis, W. I. (2005). β-catenin directly displaces Groucho/TLE repressors from Tcf/Lef in Wnt-mediated transcription activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 364-371. 10.1038/nsmb912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dent, M. A. R., Sumi, Y., Morris, R. J. and Seeley, P. J. (1993). Urokinase-type plasminogen activator expression by neurons and oligodendrocytes during process outgrowth in developing rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 5, 633-647. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, A. and Yepes, M. (2018). Urokinase-type plasminogen activator promotes synaptic repair in the ischemic brain. Neural Regen. Res. 13, 232-233. 10.4103/1673-5374.226384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, A., Merino, P., Manrique, L. G., Ospina, J. P., Cheng, L., Wu, F., Jeanneret, V. and Yepes, M. (2017). A cross-talk between Neuronal Urokinase-type Plasminogen Activator (uPA) and Astrocytic uPA Receptor (uPAR) promotes astrocytic activation and synaptic recovery in the ischemic brain. J. Neurosci. 37, 10310-10322. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1630-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, A., Merino, P., Manrique, L. G., Cheng, L. and Yepes, M. (2019). Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) protects the tripartite synapse in the ischemic brain via ezrin-mediated formation of peripheral astrocytic processes. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39, 2157-2171. 10.1177/0271678X18783653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, A., Merino, P., Guo, J.-D., Yepes, M. A., McCann, P., Katta, T., Tong, E. M., Torre, E., Rangaraju, S. and Yepes, M. (2020). Urokinase-type plasminogen activator protects cerebral cortical neurons from soluble Aβ-induced synaptic damage. J. Neurosci. 40, 4251-4263. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2804-19.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupin, I., Camand, E. and Etienne-Manneville, S. (2009). Classical cadherins control nucleus and centrosome position and cell polarity. J. Cell Biol. 185, 779-786. 10.1083/jcb.200812034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, K., Wang, C. R., Jiang, F., Wong, A. Y. K., Su, N., Jiang, J. H., Chai, R. C., Vatcher, G., Teng, J., Chen, J.et al. (2013). Traumatic scratch injury in astrocytes triggers calcium influx to activate the JNK/c-Jun/AP-1 pathway and switch on GFAP expression. Glia 61, 2063-2077. 10.1002/glia.22577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, B. and Ayalon, O. (1992). cadherins. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8, 307-332. 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.001515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, B., Yehuda-Levenberg, S. and Bershadsky, A. D. (1995). Molecular interactions in the submembrane plaque of cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions. Acta Anat. 154, 46-62. 10.1159/000147751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R., Chetty, C., Bhoopathi, P., Lakka, S., Mohanam, S., Rao, J. S. and Dinh, D. E. (2011). Downregulation of uPA/uPAR inhibits intermittent hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in DAOY and D283 medulloblastoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 38, 733-744. 10.3892/ijo.2010.883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara, M., Kobayakawa, K., Ohkawa, Y., Kumamaru, H., Yokota, K., Saito, T., Kijima, K., Yoshizaki, S., Harimaya, K., Nakashima, Y.et al. (2017). Interaction of reactive astrocytes with type I collagen induces astrocytic scar formation through the integrin-N-cadherin pathway after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 23, 818-828. 10.1038/nm.4354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., Semenov, M., Tamai, K. and Zeng, X. (2004). LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/β-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development 131, 1663-1677. 10.1242/dev.01117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuberger, J. and Birchmeier, W. (2010). Interplay of cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and canonical Wnt signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a002915. 10.1101/cshperspect.a002915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.-M. A., Mishina, Y. M., Liu, S., Cheung, A., Stegmeier, F., Michaud, G. A., Charlat, O., Wiellette, E., Zhang, Y., Wiessner, S.et al. (2009). Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature 461, 614-620. 10.1038/nature08356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, A. H. and Weis, W. I. (2001). The structure of the β-catenin/E-cadherin complex and the molecular basis of diverse ligand recognition by β-catenin. Cell 105, 391-402. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00330-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemaru, K., Kubota, J., Sekiya, H., Hirose, K., Okubo, Y. and Iino, M. (2013). Calcium-dependent N-cadherin up-regulation mediates reactive astrogliosis and neuroprotection after brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 11612-11617. 10.1073/pnas.1300378110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, A., Kishida, S. and Yamamoto, H. (2006). Regulation of Wnt signaling by protein-protein interaction and post-translational modifications. Exp. Mol. Med. 38, 1-10. 10.1038/emm.2006.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimelman, D. and Xu, W. (2006). β-catenin destruction complex: insights and questions from a structural perspective. Oncogene 25, 7482-7491. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa, M., Hatakeyama, S., Shirane, M., Matsumoto, M., Ishida, N., Hattori, K., Nakamichi, I., Kikuchi, A., Nakayama, K.-i. and Nakayama, K. (1999). An F-box protein, FWD1, mediates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of β-catenin. EMBO J. 18, 2401-2410. 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjøller, L., Kanse, S. M., Kirkegaard, T., Rodenburg, K. W., Rønne, E., Goodman, S. L., Preissner, K. T., Ossowski, L. and Andreasen, P. A. (1997). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 represses integrin- and vitronectin-mediated cell migration independently of its function as an inhibitor of plasminogen activation. Exp. Cell Res. 232, 420-429. 10.1006/excr.1997.3540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lino, N., Fiore, L., Rapacioli, M., Teruel, L., Flores, V., Scicolone, G. and Sanchez, V. (2014). uPA-uPAR molecular complex is involved in cell signaling during neuronal migration and neuritogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 243, 676-689. 10.1002/dvdy.24114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, B. T., Tamai, K. and He, X. (2009). Wnt/β-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell 17, 9-26. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, B., Gelos, M., Siedow, A., Hanski, M. L., Gratchev, A., Ilyas, M., Bodmer, W. F., Moyer, M. P., Riecken, E. O., Buhr, H. J.et al. (1999). Target genes of β-catenin-T cell-factor/lymphoid-enhancer-factor signaling in human colorectal carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1603-1608. 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino, P., Diaz, A., Jeanneret, V., Wu, F., Torre, E., Cheng, L. and Yepes, M. (2017). Urokinase-type Plasminogen Activator (uPA) binding to the uPA Receptor (uPAR) promotes axonal regeneration in the central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 2741-2753. 10.1074/jbc.M116.761650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehrs, C. and Shen, J. (2010). Regulation of Lrp6 phosphorylation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 2551-2562. 10.1007/s00018-010-0329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa, M., Baribault, H. and Kemler, R. (1989). The cytoplasmic domain of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin associates with three independent proteins structurally related in different species. EMBO J. 8, 1711-1717. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03563.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos, G. and Franklin, K. B. J. (2001). The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Piedra, J., Martínez, D., Castaño, J., Miravet, S., Duñach, M. and de Herreros, A. G. (2001). Regulation of β-catenin structure and activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20436-20443. 10.1074/jbc.M100194200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokutta, S. and Weis, W. I. (2007). Structure and mechanism of cadherins and catenins in cell-cell contacts. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 237-261. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, A.-B. and Cadigan, K. M. (2017). Wnt target genes and where to find them. F1000Research 6, 746. 10.12688/f1000research.11034.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennoll, S. and Yochum, G. (2015). Regulation of MYC gene expression by aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer. World J. Biol. Chem. 6, 290-300. 10.4331/wjbc.v6.i4.290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rømer, J., Bugge, T. H., Fyke, C., Lund, L. R., Flick, M. J., Degen, J. L. and Danø, K. (1996). Impaired wound healing in mice with a disrupted plasminogen gene. Nat. Med. 2, 287-292. 10.1038/nm0396-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampietro, J., Dahlberg, C. L., Cho, U. S., Hinds, T. R., Kimelman, D. and Xu, W. (2006). Crystal structure of a β-catenin/BCL9/Tcf4 complex. Mol. Cell 24, 293-300. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom, O. J., Meniel, V. S., Muncan, V., Phesse, T. J., Wilkins, J. A., Reed, K. R., Vass, J. K., Athineos, D., Clevers, H. and Clarke, A. R. (2007). Myc deletion rescues Apc deficiency in the small intestine. Nature 446, 676-679. 10.1038/nature05674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih, W. and Yamada, S. (2012). N-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion promotes cell migration in a three-dimensional matrix. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3661-3670. 10.1242/jcs.103861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H. W. and Marshall, C. J. (2010). Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 23-36. 10.1038/nrm2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stakheev, D., Taborska, P., Strizova, Z., Podrazil, M., Bartunkova, J. and Smrz, D. (2019). The WNT/β-catenin signaling inhibitor XAV939 enhances the elimination of LNCaP and PC-3 prostate cancer cells by prostate cancer patient lymphocytes in vitro. Sci. Rep. 9, 4761. 10.1038/s41598-019-41182-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulniute, R., Shen, Y., Guo, Y.-Z., Fallah, M., Ahlskog, N., Ny, L., Rakhimova, O., Broden, J., Boija, H., Moghaddam, A.et al. (2016). Plasminogen is a critical regulator of cutaneous wound healing. Thromb. Haemost. 115, 1001-1009. 10.1160/TH15-08-0653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi, Y., Dent, M. A., Owen, D. E., Seeley, P. J. and Morris, R. J. (1992). The expression of tissue and urokinase-type plasminogen activators in neural development suggests different modes of proteolytic involvement in neuronal growth. Development 116, 625-637. 10.1242/dev.116.3.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T., Sakata, H., Kato, C., Connor, J. A. and Morita, M. (2012). Astrocyte activation and wound healing in intact-skull mouse after focal brain injury. Eur. J. Neurosci. 36, 3653-3664. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08280.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai, K., Semenov, M., Kato, Y., Spokony, R., Liu, C., Katsuyama, Y., Hess, F., Saint-Jeannet, J.-P. and He, X. (2000). LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature 407, 530-535. 10.1038/35035117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenta, T., Hausmann, G. and Basler, K. (2012). The many faces and functions of β-catenin. EMBO J. 31, 2714-2736. 10.1038/emboj.2012.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veelen, W., Le, N. H., Helvensteijn, W., Blonden, L., Theeuwes, M., Bakker, E. R. M., Franken, P. F., van Gurp, L., Meijlink, F., van der Valk, M. A.et al. (2011). β-catenin tyrosine 654 phosphorylation increases Wnt signalling and intestinal tumorigenesis. Gut 60, 1204-1212. 10.1136/gut.2010.233460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley, K. (2019). Reprogramming astrocytes for repair. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 647. 10.1038/s41583-019-0227-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, J. L., Smith, A. A. and Helms, J. A. (2012). Wnt signaling and injury repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a008078. 10.1101/cshperspect.a008078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, J. L., Smith, A. A., Liu, B., Manzano, W. R., Evans, N. D., Dhamdhere, G. R., Fang, M. Y., Chang, H. Y., Oro, A. E. and Helms, J. A. (2013). Augmenting endogenous Wnt signaling improves skin wound healing. PLoS ONE 8, e76883. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wind, T., Hansen, M., Jensen, J. K. and Andreasen, P. A. (2002). The molecular basis for anti-proteolytic and non-proteolytic functions of plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1: roles of the reactive centre loop, the shutter region, the flexible joint region and the small serpin fragment. Biol. Chem. 383, 21-36. 10.1515/BC.2002.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X., Tu, X., Joeng, K. S., Hilton, M. J., Williams, D. A. and Long, F. (2008). Rac1 activation controls nuclear localization of β-catenin during canonical Wnt signaling. Cell 133, 340-353. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y., Clements, W. K., Kimelman, D. and Xu, W. (2003). Crystal structure of a β-catenin/axin complex suggests a mechanism for the β-catenin destruction complex. Genes Dev. 17, 2753-2764. 10.1101/gad.1142603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, S., Pokutta, S., Drees, F., Weis, W. I. and Nelson, W. J. (2005). Deconstructing the cadherin-catenin-actin complex. Cell 123, 889-901. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., Iyer, R. R., Yu, A. C. H., Yong, R. L., Park, D. M., Weil, R. J., Ikejiri, B., Brady, R. O., Lonser, R. R. and Zhuang, Z. (2012). β-catenin signaling initiates the activation of astrocytes and its dysregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of astrocytomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6963-6968. 10.1073/pnas.1118754109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X., Huang, H., Tamai, K., Zhang, X., Harada, Y., Yokota, C., Almeida, K., Wang, J., Doble, B., Woodgett, J.et al. (2008). Initiation of Wnt signaling: control of Wnt coreceptor Lrp6 phosphorylation/activation via frizzled, dishevelled and axin functions. Development 135, 367-375. 10.1242/dev.013540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.