Abstract

Background:

Disasters have many health consequences such as suicide ideation as one of the relatively common psychological consequences after natural disasters, especially earthquakes. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of post-earthquake suicidal ideation in affected people.

Methods:

Related keywords of this systematic review and meta-analysis in English and their Persian equivalents were searched in the data resources including Google Scholar, SID, Magiran, Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science from Jan 2014 to May 2019. The STROBE checklist was used to evaluate the quality of the articles. The I2 index was used to determine the heterogeneity and the random-effects model was used in meta-analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted in the STATA software version 14.

Results:

Overall, 14347 subjects including 6662 males and 7715 females with the mean age of 23.88 ± 15.81yr old were assessed. The prevalence of post-earthquake suicidal ideation was 20.34% (95% CI: 13.60–27.08, P<0.001, I2=99.1). The prevalence of suicidal ideation showed a decreasing trend based on the year of the study and the duration of post-earthquake follow-up.

Conclusion:

Although the prevalence of post-earthquake suicidal ideation showed a decreasing trend, the probability of incidence of these thoughts in the long-term is still noticeable. Therefore, implementing a surveillance system is recommended to monitor the mental health status of earthquakes survivors for the possibility of suicidal thoughts in the short and long term recovery phase.

Keywords: Suicidal ideation, Suicidal thought, Natural disasters, Earthquakes, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Introduction

Suicide is one of the indicators of mental health. Suicidal behaviors include ideation, planning, and attempting suicide. Suicidal ideation is also defined as ideas, wishes, and a tendency to suicide (1, 2). Disasters can exert devastating effects on the health status at individual and social levels and lead to changes in the infrastructure of communities. People affected by disasters are also susceptible to physical and psychological disturbances (3).

The earthquake has many mental health consequences and the risk of depression; anxiety, suicide, and post-trauma stress disorder (PTSD) are increased in the aftermath of survivors. Due to the lack of knowledge, experience, and adaptive skills, adolescents are particularly prone to suicidal behaviors. Increasing the incidence of behavioral problems such as substance abuse after a natural disaster exacerbates the adverse social consequences of the event (4). 81.5% of earthquake survivors were reported unplanned suicide ideation (5).

The rate of prevalence of psychological and behavioral problems among disaster survivors depends on the nature of the disaster, the duration of follow-up, the tools utilized to diagnose the disorders, the extent of supportive services and finally cultural context (6, 7). Different psychological consequences such as suicidal ideation are increased after natural disasters. Various predisposing factors such as major depression, history of previous mental health problems, property damage, economic issues, injury or loss of relatives and life-threatening conditions can exaggerate the suicidal ideation after disasters (8). The rates of suicidal ideation were 16.3% and 20.3% in people who experienced at least one natural or human-made disaster respectively (9).

Considering numerous studies on the prevalence of suicidal ideation over varying periods post-disaster, it is required to validate the results of these studies by meta-analysis to provide an accurate measure for planners and researchers in this field.

Methods

This was an applied study conducted through systematic review and meta-analysis based on the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)(10). To obtain related studies, a comprehensive search was performed in data resources including Google Scholar, SID, Magiran, Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science. The keywords in English and their Persian equivalents included “suicidal ideation*”, “suicidal thought*”, “Psychiatric Disease*”, “Psychiatric Disorder*”, “Mental Health Problem*”, earthquake*, “natural disaster*”, “mental health disorder*”. Boolean operators of (AND) and (OR) were used to conduct combinational searches. Articles published from Jan 2014 to May 2019 were recruited. The search strategy in the PubMed database was as follows: ((“Suicidal Ideation*”[All Fields] OR “Suicidal thought*”[All Fields] OR “Mental Health Problem*”[All Fields] OR “Mental health Disorder*”[All Fields] OR “Psychiatric Disease*”[All Fields] OR “Psychiatric Disorder*”[All Fields]) AND ((“earthquakes”[MeSH Terms] OR “earthquakes”[All Fields] OR “earthquake”[All Fields]) OR “Natural Disaster*”[All Fields])) AND ((“2014/01/01”[PDAT] : “2019/5/31”[PDAT].

Eligibility criteria

Studies reporting the prevalence of suicidal ideation in post-earthquake survivors at all age groups were included. Studies unrelated to the topic, not reporting the prevalence of post-earthquake suicidal ideation, Case reports, Letters to the editor, Brief reports, Review articles, Interventional studies and studies that did not report follow-up periods were excluded. Moreover, studies on the prevalence of suicidal attempts or planning, and those reporting suicidal ideation after Man-made or natural disasters other than earthquakes (such as floods, storms, and hurricanes) were also omitted. In the next step, two researchers selected the studies independently.

Evaluation of Studies

The quality of the studies was conducted by two researchers independently through the standard strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (11), which has 22 sections encompassing the minimum and maximum scores of 0 and 44 respectively. Based on the obtained scores, the studies were divided into either poor (<16), moderate (16–30) or good (31–44) quality categories (12). The studies that obtained at least the minimum score of 16, entered the meta-analysis process. The disagreement between the two researchers was resolved through group discussion.

Data extraction

The two researchers using a pre-prepared checklist extracted the data from the included studies independently. The disagreement between them was resolved through group discussion. The extracted data included the first authors’ names, the year of the study, the location of the study, the total sample size, the mean age and the number of women and men, follow-up periods (Month), and finally the prevalence of suicidal ideation after the earthquake.

Statistical analysis

Initially, heterogeneity between studies was determined using the I2 index. The I2 indices of <25, 25–75, and >75 represent low, moderate, high heterogeneities respectively (13). Due to the high heterogeneity among the studies, the random-effects model was used for meta-analysis of the studies. Meta-regression was utilized to investigate the relationship between the prevalence of suicidal ideation and either the year of study and the duration of post-earthquake follow-up. In this meta-analysis, Egger’s test was used to assess the publication bias. The data were analyzed using STATA software (ver. 14).

Results

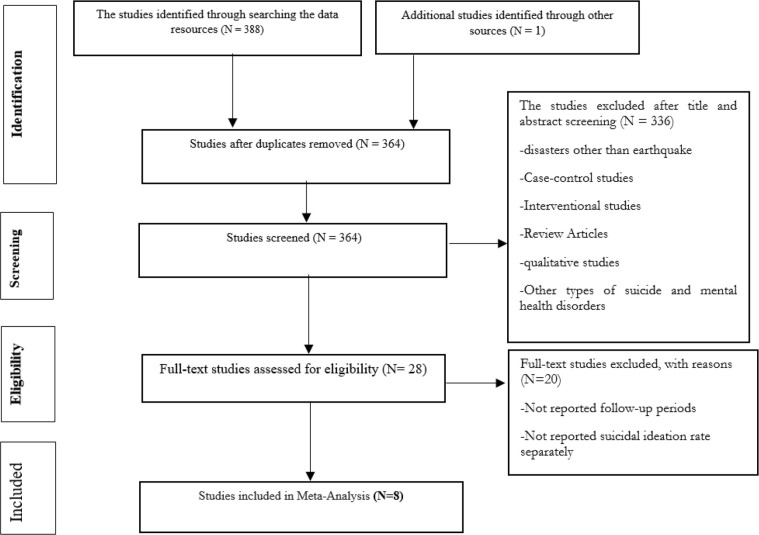

Based on the primary search limited from Jan 2014 to May 2019, 389 records were identified. Out of these, 381 studies were excluded due to the lack of inclusion criteria. Overall, 8 studies were evaluated using the STROBE checklist, and all of them acquired good quality scores and entered the meta-analysis phase. Figure 1 shows the article selection process.

Fig. 1:

Flowchart of the Study and Selection of Studies Based on PRISMA Steps

The total number of participants was 14347 including 6662 men and 7715 women with the mean age of 23.48 ± 15.81 yr old. Table 1 shows the characteristics of each analyzed study. According to the statistical analysis, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 20.34% (95% CI: 13.60–27.08, P<0.001, I2=99.1) from 4 to 96 months after the earthquake (Fig. 2). The highest prevalence of suicide ideation (35.6%) was reported within 6 to 12 months after the earthquake, and the lowest (7.26%) rate was related to 72 months post-earthquake. In the present study, the heterogeneity among the studies was obtained 99.1% showing a high heterogeneity. The results of meta-regression analyses based on the year of the study and the duration of the follow-up period post-earthquake showed a decreasing trend (Figs. 3 and 4). The publication bias was not significant using Egger’s test (P=0.338) (Fig. 5).

Table 1:

The characteristics of the evaluated studies

| First Author | Year of publication | Location of study | Sample size | Male | Female | Mean age | Follow up (Month) | Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kane (14) | 2018 | Nepal | 513 | 213 | 300 | 42.1 | 4 | 10.9% |

| Ran (15) | 2015 | China | 737 | 321 | 416 | 16.9 | 6 | 35.6% |

| Ran (15) | 2015 | China | 548 | 237 | 311 | 16.9 | 12 | 35.6% |

| Ran (15) | 2015 | China | 548 | 237 | 311 | Not reported | 18 | 30.7% |

| Ying (16) | 2015 | china | 2298 | 1127 | 1164 | 12.7 | 12 | 14.4% |

| Wang (17) | 2016 | China | 67 | 67 | 18 | 32 | 11 | 21.4% |

| Tanaka (4) | 2016 | China | 2641 | 1182 | 1459 | 15 | 72 | 7.26% |

| Fujiwara (18) | 2017 | Japan | 133 | 68 | 65 | 6.99 | 36 | 11.3% |

| Guo (19) | 2017 | China | 1357 | 632 | 725 | 54.34 | 96 | 9.1% |

| Tang (20) | 2018 | China | 5505 | 2541 | 2964 | 14.4 | 36 | 27.8% |

Fig. 2:

Forest Plot shows the prevalence of suicidal ideation post-earthquake based on the random-effects model

Fig. 3:

Meta-regression based on the year of the study

Fig. 4:

Meta-regression based on the follow-up periods

Fig. 5:

Egger’s funnel plot for publication bias

Discussion

In the present study, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was obtained 20.34% (95% CI: 13.60–27.08, P<0.001, I2=99.1) at 4 to 96 months after the earthquake. The prevalence of suicidal ideation showed a decreasing trend over time. In other studies, the rate of suicidal ideation was 33% during the first year after the earthquake (21). The prevalence of suicidal ideation over 12 months was 29.5% at three years following an earthquake (20). In Iran, the rate of suicidal ideation was reported as 4.5% among the survivors of the Bam earthquake (22). By comparing suicide rates in Iran and other countries, this decrease may be due to timely mental health services and psychosocial support for earthquake survivors.

Among the most important factors triggering suicidal behaviors after the earthquake has been the post-trauma stress disorder (PTSD). In Iran, the prevalence of PTSD after the earthquake was reported as 58% with a strong correlation between PTSD and the incidence of suicide after the earthquake. Individuals with undiagnosed and untreated PTSD are particularly exposed to suicide behaviors after the earthquake. By educating stress compatibility strategies to earthquake survivors, it is amenable to reduce the incidence of PTSD after the disaster (23–25). Moreover, it is possible to prevent psychological problems in earthquake survivors by reducing post-trauma stress by providing social support and psychological services and improving their quality of life (26).

Another important factor predisposing to post-disaster suicidal ideation is the history of psychological problems. In today’s societies, as well as financial and familial conflicts, can exaggerate the risk of suicidal behaviors and other psychological disorders in earthquake survivors. Therefore, identifying the risk factors of suicidal ideation is the first step to prevent and treat suicidal ideation and behaviors (27, 28). In 2017, Iran experienced an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.3 Richter in Kermanshah Province (29, 30). In a study (31), low and high-risk suicidal ideation were reported as 49.2% and 34.7% among widowed women in Kermanshah. Considering the recent earthquake in Kermanshah and the high reported rate of suicide in western Iranian provinces, earthquake-affected residents of western regions of Iran are at high risk of suicide. Therefore, it is important to augment psychological restraints and adaptive behaviors by providing long-term and continuous mental health services to prevent suicide in these individuals.

In the present study, the meta-regression analysis regarding 96-month follow-up and the year of the study conduction showed a decreasing trend in the rate of suicidal ideation; nevertheless, there is still a possibility for suicide even at long periods after the earthquake. In a study on the death rate from suicidal attempts over 10 years following the 1999 Taiwan earthquake, a decreasing trend was noticed over time (32). On the other hand, a 5-year follow-up of the survivors of the Fukushima disaster showed an increasing trend in the prevalence of suicidal ideation over time (33). The opposite trends observed in our study and that of the Fukushima catastrophe can be related to the extent of the physical and psychological consequences of the Fukushima incident in which an earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear incident happened at the same time. Overall, long-term and continuous mental health services are required to prevent suicidal ideation and other suicidal behaviors in survivors of man-made disasters.

Limitations

In most studies, the prevalence of suicidal ideation had not been expressed by gender, and therefore it was not possible to calculate the prevalence and the tendency to suicidal ideations in men and women separately. In one study, the rate of suicidal ideation after the earthquake was reported within three different periods and along with different sample sizes. This study was repeated three times in the forest plot to calculate the total prevalence. In some studies, the research team used the weighted average percentage to report the overall prevalence of suicidal ideation.

Conclusion

Although the prevalence of post-earthquake suicidal ideation showed a decreasing trend, the probability of incidence of these thoughts in the long-term is still noticeable. Therefore, implementing a surveillance system is recommended to monitor the mental health status of earthquakes survivors for the possibility of suicidal thoughts in the short and long term recovery phase. In present review, the heterogeneity among the studies was high. In order to prevent the impact of heterogeneity, it is recommended to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis on studies using same tools and methodologies to determine the prevalence of post-trauma suicidal ideation. On the other hand, it is suggested to perform a meta-analysis to ascertain the risk factors of suicidal ideations after earthquake.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors declared that they received no financial support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ziaei R, Viitasara E, Soares J, et al. (2017). Suicidal ideation and its correlates among high school students in Iran: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazyar J, Jahangiri K, Safarpour H, et al. (2018). The Estimation of Survival and Associated Factors in Self-Immolation Attempters in Ilam Province of Iran (2011–2015). Open Access Maced J Med Sci, 6(11):2057–2061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thordardottir EB, Gudmundsdottir B, Petursdottir G, et al. (2018). Psychosocial support after natural disasters in Iceland-implementation and utilization. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct, 27:642–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka E, Tsutsumi A, Kawakami N, et al. (2016). Long-term psychological consequences among adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake in China: a cross-sectional survey six years after the disaster. J Affect Disord, 204:255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begum N, Malik AA, Shahzad S. (2014). Prevalence of psychological problems among survivors of the earthquake in northern areas of Pakistan. Asian Journal of Management Sciences & Education, 3:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kar N. (2009). Psychological impact of disasters on children: review of assessment and interventions. World J Pediatr, 5:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pfefferbaum B, Jacobs AK, Griffin N, Houston JB. (2015). Children’s disaster reactions: the influence of exposure and personal characteristics. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 17(7):56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratta P, Capanna C, Carmassi C, et al. (2014). The adolescent emotional coping after an earthquake: A risk factor for suicidal ideation. J Adolesc, 37(5):605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reifels L, Spittal MJ, Dückers ML, et al. (2018). Suicidality risk and (repeat) disaster exposure: findings from a nationally representative population survey. Psychiatry, 81(2):158–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. (2014). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg,12(12):1500–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahebi A, Jahangiri K, Sohrabizadeh S, Golitaleb M. (2019). Prevalence of Workplace Violence Types against Personnel of Emergency Medical Services in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iran J Psychiatry, 14(4):325–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazemzadeh M, Shafiei E, Jahangiri K, et al. (2019). The Preparedness of Hospital Emergency Departments for Responding to Disasters in Iran; a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med, 7(1):e58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kane JC, Luitel N, Jordans M, et al. (2018). Mental health and psychosocial problems in the aftermath of the Nepal earthquakes: findings from a representative cluster sample survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci, 27(3):301–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ran M-S, Zhang Z, Fan M, et al. (2015). Risk factors of suicidal ideation among adolescents after Wenchuan earthquake in China. Asian J Psychiatr, 13:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ying L, Chen C, Lin C, et al. (2015). The Relationship Between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms and Suicide Ideation Among Child Survivors Following the W enchuan Earthquake. Suicide Life Threat Behav, 45(2):230–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang XL, Yip PS, Chan CL. (2016). Suicide prevention for local public and volunteer relief workers in disaster-affected areas. J Public Health Manag Pract, 22(3):E39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiwara T, Yagi J, Homma H, et al. (2017). Suicide risk among young children after the Great East Japan Earthquake: A follow-up study. Psychiatry Res, 253:318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo J, He H, Fu M, et al. (2017). Suicidality associated with PTSD, depression, and disaster recovery status among adult survivors 8 years after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Psychiatry Res, 253:383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang W, Zhao J, Lu Y, et al. (2018). Suicidality, posttraumatic stress, and depressive reactions after earthquake and maltreatment: a cross-sectional survey of a random sample of 6132 Chinese children and adolescents. J Affect Disord, 232:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yousefi K, Rezaie Z, Sahebi A. (2019). Suicidal Ideation During a Year After the Earthquake: A Letter to Editor. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci, 13(2):e86667. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ardalan A, Mazaheri M, Naieni KH, et al. (2010). Older people’s needs following major disasters: a qualitative study of Iranian elders’ experiences of the Bam earthquake. Ageing and Society, 30:11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panagioti M, Gooding PA, Triantafyllou K, Tarrier N. (2015). Suicidality and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 50(4):525–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rezaeian M. (2013). The association between natural disasters and violence: A systematic review of the literature and a call for more epidemiological studies. J Res Med Sci, 18(12):1103–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sepahvand H, Hashtjini MM, Salesi M, et al. (2019). Prevalence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Iranian Population Following Disasters and Wars: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci, 13(1):e66124. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du B, Ma X, Ou X, et al. (2018). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress in adolescents eight years after the Wenchuan earthquake. Psychiatry Res, 262:262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull, 143(2):187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohamadian F, Cheraghi F, Narimani S, Direkvand-Moghadam A. (2019). The Epidemiology of Suicide Death and Associated Factors, Ilam, Iran (2012–2016): A Longitudinal Study. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci, 13(2): e11460. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yousefi K, Pirani D, Sahebi A. (2018). Lessons learned from the 2017 Kermanshah earthquake response. Iran Red Crescent Med J, 20(12): e87109. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharififar S, Khoshvaghti A, Jahangiri K. (2019). Management Challenges of Informal Volunteers: The Case of Kermanshah Earthquake in Iran (2017). Disaster Med Public Health Prep, 1–8. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ariapooran S, Khezeli M. (2018). Suicidal Ideation Among Divorced Women in Kermanshah, Iran: The Role of Social Support and Psychological Resilience. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci, 12(4):e3565. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen SL-S, Lee C-S, Yen AM-F, et al. (2016). A 10-year follow-up study on suicidal mortality after 1999 Taiwan earthquake. J Psychiatr Res, 79:42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orui M, Suzuki Y, Maeda M, Yasumura S. (2018). Suicide rates in evacuation areas after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Crisis, 39(5):353–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]