Abstract

Illegally induced abortions remain a significant public health issue in developing countries. We report a case that was complicated by a vesicovaginal fistula with intravesical calcification of the piece of wood used to perform the illegal abortion. A trans-vesical approach allowed extraction of the calcified foreign body and closure of the vesicovaginal fistula. The postoperative course was uneventful.

Keywords: Vesicovaginal fistula, Abortion, Lithiasis

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Senegal vesicovaginal fistulas are most often of obstetrical origin occurring after a dystocic delivery.1 These vesicovaginal fistulas, because of their psychosocial repercussions, represent an absolute tragedy for the women who suffer from them.1,2 More rarely, vesicovaginal fistulas can be of traumatic origin, occurring after an illegal induced abortion.3 We report a case of post-abortive vesicovaginal fistula due to self-introduction of a piece of wood into the vagina, which afterwards calcified in the bladder.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old female patient who was admitted in the urological emergency department for intense hypogastric pain with diffuse radiations that had been evolving for 7 months. These symptoms were associated with involuntary loss of urine through the vagina. The interrogation had revealed a notion of abortion in 2 months of gestation, by self-introduction of a stick in the vagina. On admission the patient was afebril and had a good general condition. There was tenderness on deep palpation of the hypogastrium. The vulva was soiled by unclear urine with a pungent odor. Vaginal speculum examination revealed a tapered object, about 3 cm long, whose mobilization causes urine to exit the vagina. Urine culture showed a urinary infection with Escherichia coli sensitive to amikacin. The patient was managed with amikacin 15 mg/Kg/day in two doses for 7 days. Cystoscopy showed a piece of wood of about 4 cm with significant calcification around it (Fig. 1). A computer tomography (CT) scan of the urinary tract reported a vesicovaginal invasion by a tubular foreign body strongly calcified in the bladder (Fig. 2). A cystostomy allowed extraction of the calcified piece of wood (Fig. 3) and objectified a supra-trigonal vesicovaginal fistula. In the same operation, we performed a cure of the fistula by vesicovaginal splitting, followed by closure of the vaginal plane (with 2/0 absorbable threads) and then of the bladder (with 0 absorbable threads). Spectrophotometric examination of the stone was in favor of phosphates lithiasis. The patient was put on long-term contraception and after 12 months, there was no recurrence of the vesicovaginal fistula.

Fig. 1.

Cystoscopy showing lithiasis.

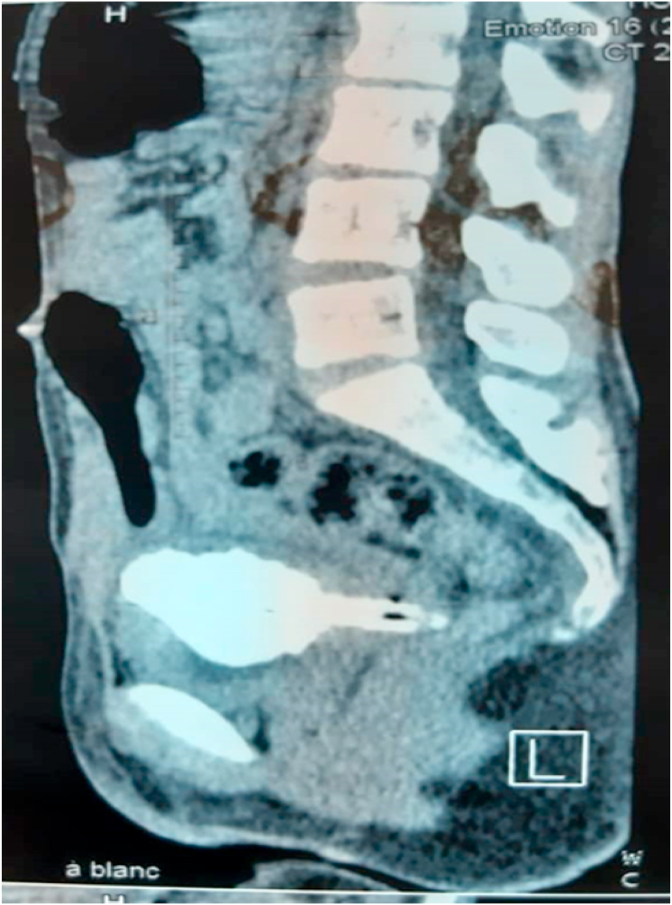

Fig. 2.

Computer tomography (CT) scan of the urinary tract showed a vesicovaginal invasion by a tubular foreign body strongly calcified in the bladder.

Fig. 3.

The piece of calcified wood extracted after cystotomy.

Discussion

Post-abortive vesicovaginal fistulas represent a rare entity. In India Kallol et al. reported two cases of post-abortive vesicovaginal fistulas in a series of 23 patients with urogenital fistula.3 In developing countries, illegally induced abortions are the cause of hemorrhagic, infectious and traumatic complications.4 This is the first case of post-abortive vesicovaginal fistula reported in Senegal. Illegally induced abortion is most often performed by non-medical personnel, outside of a hospital setting. In 45% of cases, it is a self-abortion, as in the case of our patient.4 The means utilized for abortion are variable: curettes, metal probes, and plant stem.4 The stone formation in our patient was favored by the presence of a foreign body associated with a urinary infection by Escherichia Coli. Bouya et al. reported a series of six vesicovaginal fistulas complicated with bladder lithiasis.5 They noticed lithogenesis was due to urinary tract infection associated with the presence of non-resorbable sutures.5 Post-abortive vesicovaginal fistulas are most often supra-trigonal.3 This topography allowed us to approach the vesicovaginal fistula by the upper approach. So, in the same operating time, we performed the extraction of a massive stone and the closure of the vesicovaginal fistula.

Conclusion

In Senegal, despite the penalization of illegal induced abortion and the popularization of contraceptive methods, illegal induced abortion stays widespread. It can be the cause of dramatic complications like as a vesicovaginal fistula.

Authors' contributions

A S, A N and O S: Drafting manuscript and bibliographic research through a review of the literature. B S, C Z O and A K N: Correction and elaboration of the final manuscript. They constituted the ethics committee that approved the document. All authors participated in the management of the patient.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Gueye S.M., Diagne B.A., Mensah A. Les fistules vésico-vaginales: aspects étio-pathogéniques et thérapeutiques au Sénégal. Med Afri Noire. 1992;39(8/9):559–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarr A., Sow Y., Thiam A. Fistules vésico-vaginales post hystérectomie. Prog Urol. 2013;23(10):884–889. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallol K.R., Neena M., Sunesh K., Amlesh S., Bonilla N. Genitourinary fistula - an experience from a tertiary care hospital. JK Sci. 2006;8(3):144–147. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iloki L.H., Zakouloulou-Massala A., Gbala-Sapoulou M.V. Complications des avortements clandestins : a propos de 221 cas observés au CHU de Brazzaville (Congo) Med Afri Noire. 1997;44(5):262–264. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouya P.A., OdzébéA W.S., Ondongo Atipo M.A., Andzin M. Fistules vésico-vaginales avec calculs enclavés. Prog Urol. 2012;22(9):549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]