Abstract

Background: Nearly 75% of Black non-Hispanic babies born in 2016 ever breastfed. However, Black mothers still experience barriers to breastfeeding, perpetuating disparities in exclusivity and duration.

Subjects and Methods: Using data collected from five focus groups with Black mothers (N = 30) in Washington, District of Columbia during summer 2019, we critically examine the influence of institutionalized and personally mediated racism on breastfeeding. We also explore the counter-narratives Black women use to resist oppression and deal with these barriers.

Results: Themes surrounding institutionalized racism included historic exploitation, institutions pushing formula, and lack of economic and employment supports. Themes regarding how personally mediated racism manifested included health care interactions and shaming/stigma while feeding in public. At each level examined, themes of resistance were also identified. Themes of resistance to institutionalized racism were economic empowerment and institutions protecting breastfeeding. Themes of resistance to personally mediated biases were rejecting health provider bias and building community.

Conclusions: There are opportunities for health providers and systems to break down barriers to breastfeeding for Black women. These include changes in clinical training and practice as well as clinicians leveraging their position and lending their voices in advocacy efforts.

Keywords: breastfeeding, racism, Black mothers, critical race theory

Introduction

Nearly 75% of Blacki non-Hispanic babies born in 2017 in the United States were ever breastfed. Although breastfeeding rates have increased among Black women since the 1970s, they still experience many barriers to breastfeeding, perpetuating disparities in duration and exclusivity.1–3 These barriers are a consequence of the intersection of racialized identity, gender, and class.4,5

Critical race theory (CRT) is a framework explaining connections between race, power, and law.6 CRT strategically considers how people who experience adverse outcomes as a result of racism work to resist oppression. CRT is useful for analyzing the barriers resulting from racism, sexism, and classism, as well as calling attention to the steps Black mothers take to advocate for themselves and counter various forms of racism along their breastfeeding journeys.

Jones7 identifies racism as the “root cause of raceii-associated differences in health outcomes.” Dr. Jones defined three levels of racism: institutionalized, personally mediated, and internalized.8 The research here focuses on two levels: institutionalized racism, “differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race” (p. 1212), and personally mediated racism, “prejudice and discrimination, where prejudice means differential assumptions about the abilities, motives, and intentions of others according to their race, and discrimination means differential actions toward others according to their race” (pp. 1212–1213).

Drawing on Jones's levels of racism and her challenge to ask “how is racism operating here?” we sought to answer the following research question: how does racism create barriers to breastfeeding for Black mothers? Drawing on CRT, we also examined the ways Black women resist racism during their quest to breastfeed.

Methods

Study design

This study was a secondary analysis of deidentified data. The original research was approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board on June 13, 2019 (NCR #191050). Methods for participant recruitment and data collection are described in detail elsewhere and summarized briefly hereunder.9,iii

Participant recruitment

Purposive convenience sampling was used to recruit 30 mothers who self-identified as Black (non-Hispanic), lived in Washington, District of Columbia (DC), and had at least one child between 2016 and 2019. A socioeconomically diverse sample was achieved by promoting the study through a broad range of partner organizations in different parts of the city.

Data source

Five 90-minute focus groups were conducted in 2019. The first author, a Black female expert in focus group facilitation, led groups with a semistructured guide developed for the original study. The focus group guide included broad questions about breastfeeding, how women made the decision to breastfeed or formula feed, and their understanding of the connection between breastfeeding and health. Sample questions from the guide are shown in Figure 1. The second author served as notetaker. Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. It should be noted that this research is a secondary analysis. Therefore, the questions in the focus group guide were not intended to examine racism specifically; however, after initial analysis, the two cofirst authors observed that racism and resistance were dominant in the participant's talk, and thus formed the present research question.

FIG. 1.

Representative sample focus group questions from the original study.

Data analysis

The cofirst authors conducted iterative pragmatic thematic analysis using MAXQDA Plus 2018 software, applying a priori codes for the two levels of racism (institutionalized and personally mediated) to each transcript. Coders also assigned those two codes to examples of resistance against racism. Multiple discussions of interpretations showed strong agreement on emergent patterns, which were used to identify the themes presented. For each theme reported, coders ensured that there were representative responses. In general, the authors noted a theme if there were four or more similar statements. Sample quotations were selected for inclusion in the figures as evidence for the breadth of each theme. For example, participant 8 was not the only participant to acknowledge historic exploitation of Black women's labor, but the single quotation captures the full scope of that theme, whereas the three comments under the next theme were necessary to show the types of institutions pushing formula that were evidenced in the data.

Results

Participant characteristics

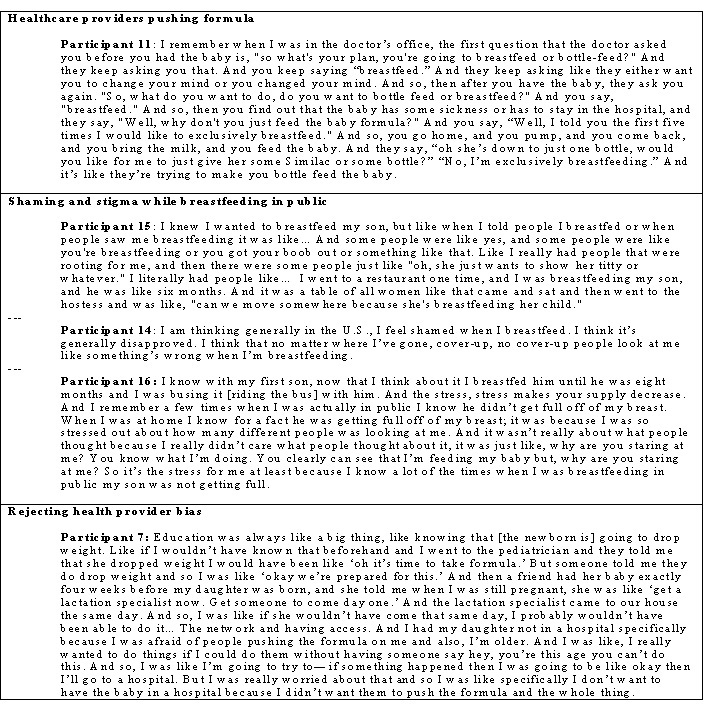

Thirty women participated in the focus groups, 90% of whom reported that they had breastfed or attempted to breastfeed. See Table 1 for detailed participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Focus Group Participants (N = 30)

| Geographic residence | |

| East End of District of Columbia (Wards 7 and 8) | 18 |

| Educational achievement | |

| Some high school | 1 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 6 |

| Vocational training, some college or associate's degree | 11 |

| Bachelor's degree | 4 |

| Master's degree | 6 |

| Doctoral degree | 2 |

| Financial status | |

| Do not meet basic expenses | 4 |

| Just meet basic expenses | 14 |

| Meet needs with little left over | 3 |

| Live comfortably | 9 |

| Ever received government assistance (food, housing, etc.), yes | 17 |

| Mother's age at most recent birth | Range: 18–48 Mean: 32 years |

| Ever breastfed, yes | 27 |

| Number of children | Range: 1–8 Median: 2 children |

| Youngest child's age | Range: newborn to 3 years |

| Relationship status | |

| Romantic relationship, yes | 26 |

| Living with romantic partner, yes | 19 |

| Married, yes | 9 |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Heterosexual | 26 |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 15 |

| No religion | 11 |

| Other religious identity | 4 |

| One or both parents foreign born, yes | 4 |

| Parent received government support, yes | 20 |

| Mother was nursed as an infant, yes | 10 |

Institutionalized racism and resistance

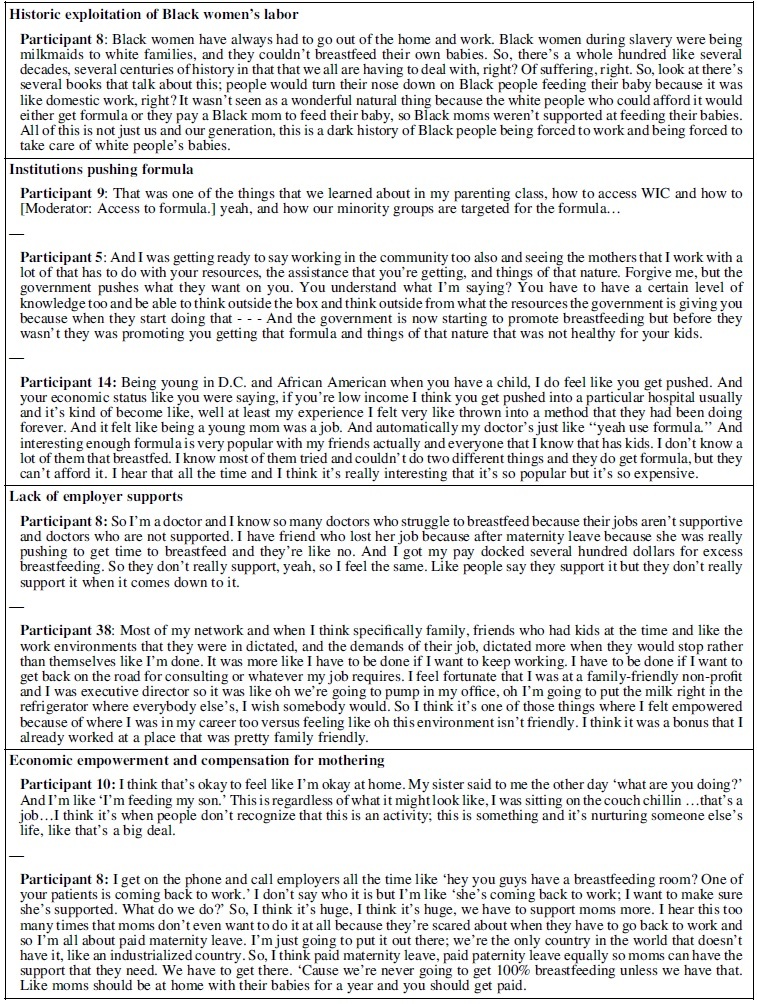

Three forms of institutionalized racism as significant barriers to breastfeeding were culled out as themes, including (1) the historic exploitation of Black women's labor, (2) institutions pushing formula on Black mothers, and (3) lack of economic and employer-based support. Participants suggested policy and systems changes that would serve to counter forms of institutionalized racism. Themes included (1) economic empowerment and compensation for mothering and (2) institutions protecting breastfeeding (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Representative sample quotations for themes related to institutionalized racism and resistance.

In reflecting on their breastfeeding journeys, participants discussed their ancestors' historic exploitation as wet nurses for white children at the expense of their own children.11 They noted this history not only to counter perceptions of breastfeeding as uncommon or unpopular among Black women but also to remark on the ways Black babies had been deprived of breastfeeding. In Figure 2, one participant discusses the meaning of Black women's exploited labor.

Several participants noted that artificial infant formula remains common in Black communities. They suggested that formula's popularity is, in part, due to the subsidizing of formula through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Some participants reported feeling like WIC historically and continuously pushes formula use. In contrast, several participants recognized the power of WIC's change in messaging to promote breastfeeding, provision of peer counselors, and the enhancement of the food package for breastfeeding mothers. These comments reflect an institution both pushing formula and protecting breastfeeding.

Several mothers compared postpartum experiences at different local hospitals to illustrate the importance of institutions protecting breastfeeding. They discussed whether their babies were separated from them, and pointed out that facilities with rooming-in policies facilitated breastfeeding. Participants also described differing access to lactation support staff and receipt of unsolicited formula samples and bottle feeding supplies at discharge.

Participants across focus groups often commented on economic and employment factors as barriers or facilitators to breastfeeding. Discussion around the significance of paid maternity leave and workplace protections for nursing mothers was substantial. Participants with access to paid leave shared how essential it was in their breastfeeding success and those who did not have access to paid leave, or knew friends or family who did not, described the negative impact on breastfeeding intentions and success. Participants described the devaluing of the work of mothering and suggested it should be seen as a job, and compensated as such. Participants reported advocacy around policies to enable new mothers to spend a year at home. One participant, a pediatrician, described advocacy with local employers on behalf of her patients, and another, an executive director at an organization, described feeling empowered partly due to her socioeconomic status (Fig. 2). Several participants reported employers unsupportive or openly hostile to pumping accommodations.

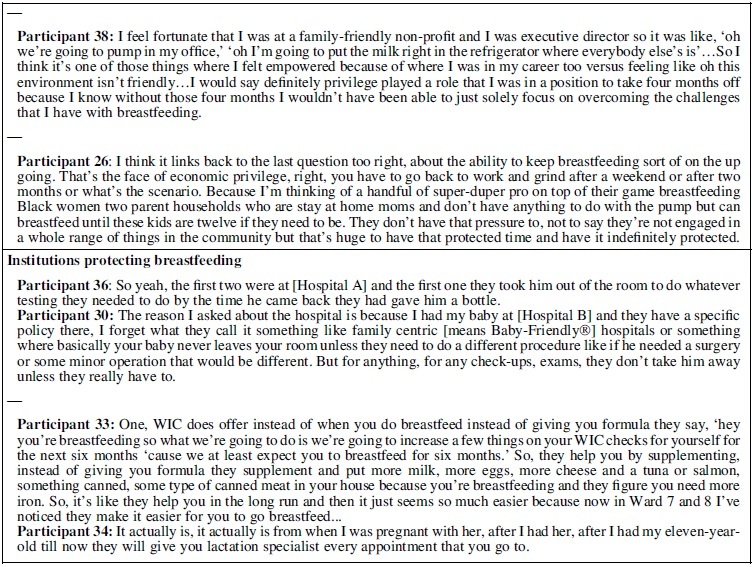

Personally mediated racism and resistance

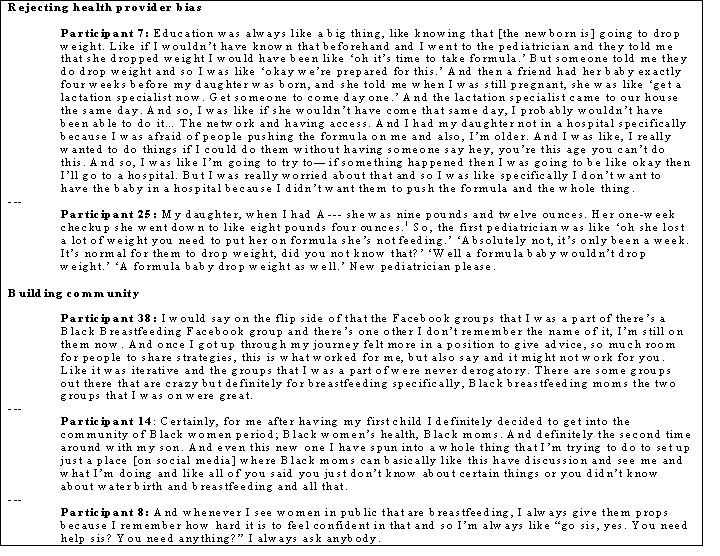

Participants remarked on two forms of personally mediated racism, including (1) negative interactions with health care providers and (2) shaming/stigma while breastfeeding in public.iv Participants likewise described ways they resisted personally mediated racism and bias including themes of (1) rejecting health provider bias and (2) building community.

Across focus group sessions, Black mothers talked about health care providers pushing formula regardless of mothers previously communicating their intentions to exclusively breastfeed, resulting in Black mothers feeling unheard or ignored. One participant described the constant questioning by medical staff when she expressed her desire to breastfeed (Fig. 3). Participants offered numerous examples of hospital staff giving their babies formula without their consent. Providers disregarded Black mothers' intentions to exclusively breastfeed their babies by offering them formula samples at hospital discharge. Participants also described feeling threatened by pediatricians with formula if their baby did not gain weight quickly; several were concerned they might be relying on outdated notions and growth charts based on formula-fed babies. Multiple participants reported not being fully informed about the potential downsides of hormonal contraception—health care providers pushed hormonal contraception either without regard to the mother's breastfeeding status or despite being told by the mother she was breastfeeding. Participants who shared contraception stories all reported suffering milk supply issues, and without referral to lactation support, ultimately stopped nursing.

FIG. 3.

Representative sample quotations for themes related to Personally mediated racism and resistance.

Black mothers rejected health provider bias when they were empowered to make decisions about where and from whom to seek care. One mother described avoiding potential formula promotion at the hospital by opting for a nonhospital birth (Fig. 3). Multiple mothers discussed changing pediatricians after feeling unsupported in their breastfeeding and pressured to supplement with formula.

An additional barrier was public shaming. Participants discussed the complexities of breastfeeding in public where people “watched” as they breastfed. Participants reported that breastfeeding was met with disapproving looks or stares (Fig. 3). Disapproval could come from many different sources including family, friends, and strangers. Participants worried about nursing in front of men or boys and talked about women commenting on their choice to breastfeed, where they chose to breastfeed, and whether they used a covering.

Black mothers resisted personally mediated racism by building and relying on community. Many participants described examples of emotional, informational, and instrumental supports from their community networks, namely family and close friends. Social media provided one channel for building community. One older mother described how she remains actively engaged in a Facebook group to pass on lessons learned to other breastfeeding Black mothers (Fig. 3). Another younger mom described how she was initiating a project to create virtual space to share and educate her peers on birthing and parenting topics. Other ways participants described building community were through intentionally offering words of support and encouragement to other Black mothers whom they did not know when they encountered them in public spaces, and by intentionally nursing in public, often uncovered, to actively change norms.

Discussion

By highlighting examples of institutionalized racism, participants immediately countered perceptions that infant feeding is reflective only of personal choice. Instead, and in line with Jones' Gardner's Tale8 and prior research in breastfeeding,10,12 they shined a light on broader structural and environmental factors that impede breastfeeding for many Black mothers.

The historic exploitation of Black women's labor draws attention to a phenomenon Andrea Freeman calls “an incident of slavery,” or an event that is a continuation of oppression originating during the antebellum period.12 Some of the barriers Black women experience date back to social practices and policies from the period of enslavement, as noted in Dorothy Roberts' seminal text Killing the Black Body.13 For example, Black women's employment circumstances today are the legacy of historic institutionalized racism. Access to paid parental leave differs by race/ethnicity with Black mothers being less likely to have access than White mothers.14 Yet, paid leave policies help Black mothers the most,15 leading to improved maternal and infant health16 and reduced negative financial impacts of unpaid leave. The Washington, DC's paid family leave program took effect in July 2020 and has the potential to address some needs unfulfilled by employers; however, it falls short of the year-long paid leave advocated by participants. DC must ensure residents are aware of the program as research in California found that workers least likely to be aware were those who stood the most to gain: young, non-White, lower socioeconomic status, and those with no employer-provided benefit.17

Institutional support for breastfeeding from employers and hospitals is an essential ingredient for countering institutionalized racism. Participants' negative workplace pumping stories implied the importance of employers protecting breastfeeding rights. Despite the existence of laws protecting nursing mothers in DC, participants reported noncompliant employer practices, so enforcement should be a priority. To this end, the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee supports a workgroup dedicated to education on employee rights and employer responsibilities, sharing resources, and advocacy around identified gaps in laws to expand protections for employees.18

Greater access to hospitals designated as Baby-Friendly® was implied as another solution to counteract institutionalized and personally mediated racism. Policies advanced through the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative19 would have helped counter some of the biases women reported related to separation during postpartum hospitalization, challenges accessing in-hospital lactation support, and receiving formula samples or the baby being given formula unnecessarily in the hospital. However nationally, access to Baby-Friendly hospitals differs by geography, and due to racial segregation, Black communities have limited access to Baby-Friendly hospitals or birthing facilities implementing effective policies.20,21 Recent research supports the importance of improved maternity care practices to increase breastfeeding, especially in areas of geographical segregation with limited access to lactation supports. Their intervention research suggests that hospital and community-based initiatives can be effective in increasing rates of breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity among Black infants.22

Study participants illustrated the power of changing policies to increase institutional support when they recognized WIC's role in promoting breastfeeding. Evidence has consistently shown that mothers participating in WIC are less likely to breastfeed.23 However, mothers in this study highlighted the positive impact of actively promoting breastfeeding, beginning in 2004 with the new Loving Support marketing and peer counseling program and reinforced by 2009 policy changes to nutrition benefits.24,25

Personally mediated and institutionalized racism are connected. Although not all participants recognized or verbalized the connection between their experiences and race, prior evidence supports this link. Women of color, and particularly Black women, are more likely to experience mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth including loss of autonomy, being scolded, and being ignored, among others forms.26 Mistreatment is worse for mothers of lower socioeconomic status. In addition, one study found that Black babies were more than nine times as likely to receive formula in the hospital than White babies.27 Furthermore, the commonness of participants' experiences shared during focus groups on Black breastfeeding suggests their experiences are undeniably connected to race, and are the result of intersecting patriarchy, classism, and racism. Negative interactions with health care providers as reported here are not inconsequential. Being dismissed may impact Black women's willingness to continue to engage with the health care system, thereby impacting their long-term health outcomes. Killing the Black Body demonstrates the close link between the interpersonal interactions Black women have with providers and the history of racist policies and practices intended to regulate Black women's sexuality and reproduction.

Some study participants felt empowered to make health care choices and resist health provider-mediated racism. This power came from a place of education and privilege, especially having the consumer's power of the purse, choosing to seek care elsewhere if necessary.v Unfortunately, mothers with fewer resources to navigate systems were not as able to push back. One mother even described feeling like being young, Black, and lower income left her with no choice regarding where to seek health care (Fig. 2). Participants spoke highly of peer counselors, midwives, and doulas, often who looked like themselves or had similar lived experiences. Others consulted fellow moms in lieu of traditional health care providers. The negative interactions reported and this dependence on other types of support reinforce that medical education and training does not adequately prepare clinicians to support Black breastfeeding mothers.28 Indeed, some participants remarked on the lack of Black health care providers, which may contribute to personally mediated racism. Recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a statement calling for the dismantling of racism on every level and a recommitment to ending inequities that threaten the health and well-being of children, representing a sense of hope that the medical field may be changing.29

Building and relying on community, especially other Black mothers, were acts of resistance, and consistent with prior research.30 Evoking Audre Lorde's concept of radical self and collective care,31 participants resisted oppression by seeking and accepting sources of social support and by seeking communities of Black mothers or building them when necessary. Their act of resistance was, in Lorde's word, “self-preservation,” and they cared for others by passing on knowledge, encouragement, and tools to succeed in a “common battle.” The building of community with other Black mothers underscores the value and lack of access to culturally congruent, or at least competent,32 lactation support and the value of seeing mothers who look like themselves succeeding at breastfeeding.

Many mothers report feeling uncomfortable or stigmatized when breastfeeding in public.33,34 Although participants did not expound on this connection, public shaming and stigmatizing of Black mothers while breastfeeding may be linked to long held norms about the role and position of women. Through chattel slavery, Black women could not comply with antebellum America's Cult of True Womanhood principals of piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity. In the 20th century, popular media promoted “controlling images” of Black women as hypersexual jezebels. In response to negative representations, some African Americans endorsed “respectability politics,” in which Black people attempted to show their worth (to the wider culture) by policing the behaviors of those within their racial group. For Black women, modesty is part of respectability politics; therefore, the visibility of the breast, even for feeding one's baby, may be deemed inappropriate by some. Thus, these negative public interpersonal interactions are inextricably connected with race and racism. The authors believe this is why several of the more empowered mothers were determined to breastfeed, often uncovered in public to help destigmatize it for other Black mothers.

Taken together, institutionalized and personally mediated racism served as toxic forms of stress for Black mothers. Participants reported being overwhelmed by the stress of dealing with bias at the institutional level, by their interactions with health care providers, and being stigmatized by members of the public. Across focus groups, participants said, “Black women are stressed.” The idea that Black mothers are stressed or have a lot on their shoulders goes to writer Zora Neale Hurston's idea that Black women are “mules of the world.”35 In other words, Black women are defined by their strength, but that strength has its limits and being strong takes a toll. Allostatic load, a measure of cumulative stress, has been associated with preterm birth, low birth weight, and higher rates of Black infant mortality.36,37

Strengths and limitations

This research has strengths and limitations that should be acknowledged. A strength of this study is that there were an equal number of women from socially and economically diverse backgrounds and representative of different parts of the DC. A limitation of the research is that 90% of women in the sample indicated that they breastfed, which may lead to bias in responses. However, we believe that our sample was appropriate to answer the stated research question.

Conclusion and Implications for Practice

This research documented that racism is a present barrier to breastfeeding at multiple levels, yet most participants were breastfeeding mothers. Echoing Dr. Stuebe's recent call to action,38 breastfeeding medicine and other maternal and infant health providers can join Black mothers in resisting racism on several fronts. Dismantling racism in clinical care starts with examining and countering our own biases, diversifying recruitment, and improving training for future providers. Clinicians must leverage their positions to advocate alongside and on behalf of Black women and mothers, for equitable access to economic empowerment including living wages, affordable housing, paid family leave, workplace protections, and for access to breastfeeding friendly birthing facilities, WIC for eligible mothers, and culturally sensitive lactation support for all.

Authors' Contributions

Dr. C.D. contributed to conceptualization of the research presented, participated in data collection and analysis, and led in article writing. Dr. A.V.K.V. led conceptualization of the research presented, participated in data collection and analysis, and contributed to article writing. Dr. M.M.T., Dr. S.L., and M.K.L.: contributed to study design and critically reviewed the initial article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants who generously shared their time and entrusted their stories to us. We also thank our community partners who facilitated recruitment, and Mamatoto Village and the East of the River Lactation Support Center for serving as focus group sites. The authors also acknowledge the advice of coinvestigator, Anayah Sangodele-Ayoka, CNM, MSN, MSEd, Clinical Instructor, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Disclaimer

The article contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This research was generously supported by the Clara Schiffer Fellowship for Women's Health and a fellowship from the Sumner M. Redstone Global Center for Prevention and Wellness. REDCap™ infrastructure that made this project possible was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (award number UL1TR001876).

In this article to economize words, we use the term Black to refer to women with African heritage across the diaspora who were born and raised in the United States. The term African American could be used interchangeably.

Critical race scholars and Camara Jones's work operate from the premise that there is no biological basis for race; racialized identity is, therefore, socially constructed and is an important influence on health outcomes as a proxy measure of experienced racism.

Villalobos A, Davis C, Turner MM, et al. Breastfeeding in context: African American women's normative referents, salient identities and perceived social norms. (In review).

Most participants did not explicitly link these biases with racism, however, due to the commonalities in stories from women across socioeconomic statuses and through examination of existing evidence, the researchers connect the dots and explain the relevance of the intersection of gender, race, and class for these themes.

A new platform helps birthing people navigate this choice. “Irth is a “Yelp-like” review and rating app for hospitals and physicians made by and for Black women & birthing people of color.” See birthwithoutbias.com

References

- 1. Anstey EH, Chen J, Elam-Evans LD, et al. Racial and geographic differences in breastfeeding-United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:723–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeVane-Johnson S, Woods-Giscombé C, Thoyre S, et al. Integrative literature review of factors related to breastfeeding in African American women: Evidence for a potential paradigm shift. J Hum Lact 2017;33:435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hillard TK. A Black woman's commentary on breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med 2014;9:349–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity, politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev 1991;43:1241–1299 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spencer B, Wambach K, Domain EW. African American women's breastfeeding experiences: Cultural, personal, and political voices. Qual Health Res 2015;25:974–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, et al. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. New York: The New Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones CP. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: Launching a national campaign against racism. Ethn Dis 2018;28(Suppl 1):231–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1212–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Villalobos A. Examining normative influences on breastfeeding intentions among African American women: Implications for health communication [dissertation]. Washington, DC: ProQuest, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Griswold MK, Crawford SL, Perry DJ, et al. Experiences of racism and breastfeeding initiation and duration among first-time mothers of the Black Women's Health Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2018;5:1180–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson K, Fial A, Hanson L. Racism, bias, and discrimination as modifiable barriers to breastfeeding for African American women: A scoping review of the literature. J Midwifery Womens Health 2019;64:734–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Freeman A. Unmothering Black women: Formula feeding as an incident of slavery. Hastings Law J 2018;69:1545–1606 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roberts D. Killing the Black Body: Race and Reproduction and the Meaning of Liberty. New York: Vintage Books, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bartel AP, Kim S, Nam J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: Evidence from four nationally representative datasets. Monthly Labor Rev 2019; https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2019/article/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-access-to-and-use-of-paid-family-and-medical-leave.htm

- 15. Rossin-Slater M, Ruhm CJ, et al. The effects of California's paid family leave program on mothers' leave-taking and subsequent labor market outcomes. J Policy Anal Manage 2013;32:224–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stearns J. The effects of paid maternity leave: Evidence from temporary disability insurance. J Health Econ 2015;43:85–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Appelbaum E, Milkman R.. Leaves that Pay: Work and Employer Experiences with Paid Leave in California. Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Workplace Support Constellation. U.S. breastfeeding committee. Available at www.usbreastfeeding.org/p/cm/ld/fid=395 (accessed January5, 2021)

- 19. The Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. Baby-friendly USA. Available at https://www.babyfriendlyusa.org/for-facilities/practice-guidelines/10-steps-and-international-code/ (accessed January5, 2021)

- 20. Lind JN, Perrine CG, Li R, et al. Racial disparities in access to maternity care practices that support breastfeeding—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63:725–728 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henley Jensen R. ‘Baby-Friendly’ hospitals bypass Black communities. W e-news. 2013. Available at https://www.womensenews.org/2013/08/baby-friendly-hospitals-bypass-black-communities/ (accessed January5, 2021)

- 22. Merewood A, Bugg K, Burnham L, et al. Addressing racial inequities in breastfeeding in the southern United States. Pediatrics 2019;143:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang Q, Lamichhane R, Wright M, et al. Trends in breastfeeding disparities in US Infants by WIC eligibility and participation. J Nutr Educ Behav 2019;51:182–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collins A, Dun Rappaport C, Burstein N. WIC breastfeeding peer counseling study final implementation report (No. WIC-10-BPC). Alexandria, VA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research and Analysis. 2010. Available at https://www.fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/WICPeerCounseling.pdf (accessed on January5, 2021)

- 25. Whaley SE, Koleilat M, Whaley M, et al. Impact of policy changes on infant feeding decisions among low-income women participating in the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children. Am J Public Health 2012;102:2269–2273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, et al. The giving voice to mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health 2019;16:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McKinney CO, Hahn-Holbrook J, Chase-Lansdale PL, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2016;138:e20152388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meek JY, Nelson JM, Hanley LE, et al. Landscape analysis of breastfeeding-related physician education in the United States. Breastfeed Med 2020;15:401–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jenco M. ‘Dismantle racism at every level’: AAP president. AAP News. 2020. Available at https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/06/01/racism060120 (accessed January5, 2021)

- 30. Asiodu IV, Waters CM, Dailey DE, et al. Infant feeding decision-making and the influences of social support persons among first-time African American mothers. Matern Child Health J 2017;21:863–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lorde, A. A Burst of Light: Essays. Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noble L, Noble A, Hand IL. Cultural competence of healthcare professionals caring for breastfeeding mothers in urban areas. Breastfeed Med 2009;4:221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hauck YL, Bradfield Z, Kuliukas L.. Women's experiences with breastfeeding in public: An integrative review. Women Birth 2020; [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bresnahan M, Zhu Y, Zhuang J, et al. “He wants a refund because I'm breastfeeding my baby”: A thematic analysis of maternal stigma for breastfeeding in public. Stigma Health 2020;5:394–403 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hurston ZN. Their Eyes Were Watching God. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott, 1937 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wallace ME, Harvill EW. Allostatic load and birth outcomes among white and Black women in New Orleans. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1025–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gross E, Efetevbia V, Wilkins A. Racism and sexism against Black women may contribute to high rates of Black infant mortality. Child trends. 2019. Available at https://www.childtrends.org/blog/racism-sexism-against-black-women-may-contribute-high-rates-black-infant-mortality (accessed on January5, 2021)

- 38. Stuebe A. #BlackLivesMatter and breastfeeding medicine: A call to action. Breastfeed Med 2020;15:479–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]