Abstract

Background:

The inhibitory receptor FcγRIIB is expressed on human and murine bone marrow–derived cells and limits inflammation by suppressing signaling through stimulatory receptors.

Objective:

We sought to evaluate the effects of K9.361, a mouse IgG2a alloantibody to mouse FcγRIIB, on murine anaphylaxis.

Methods:

Wild-type and FcγR-deficient mice were used to study anaphylaxis, which was induced by injection of 2.4G2 (rat IgG2b mAb that binds both FcγRIIB and the stimulatory receptor FcγRIII), by actively immunizing IgE-deficient mice and then challenging with the immunizing antigen, and by passive immunization with IgG or IgE anti–2,4,6-trinitrophenyl mAb, followed by injection of 2,4,6-trinitrophenyl–ovalbumin. Pretreatment with K9.361 was assessed for its ability to influence anaphylaxis.

Results:

Unexpectedly, K9.361 injection induced mild anaphylaxis, which was both FcγRIIB and FcγRIII dependent and greatly enhanced by β-adrenergic blockade. K9.361 injection also decreased expression of stimulatory Fcγ receptors, especially FcγRIII, and strongly suppressed IgG-mediated anaphylaxis without strongly affecting IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. The F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 did not induce anaphylaxis, even after β-adrenergic blockade, and did not deplete FcγRIII or suppress IgG-mediated anaphylaxis but prevented intact K9.361-induced anaphylaxis without diminishing intact K9.36 suppression of IgG-mediated anaphylaxis.

Conclusion:

Cross-linking FcγRIIB to stimulatory FcγRs through the Fc domains of an anti-FcγRIIB mAb induces and then suppresses IgG-mediated anaphylaxis without affecting IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. Because IgG- and IgE-mediated anaphylaxis can be mediated by the same cell types, this suggests that desensitization acts at the receptor rather than cellular level. Sequential treatment with the F(ab′)2 fragment of anti-FcγRIIB mAb followed by intact anti-FcγRIIB safely prevents IgG-mediated anaphylaxis.

Keywords: Fc receptors, anaphylaxis, mouse, signaling, IgG, IgE

Anaphylaxis is an acute multisystem syndrome that results from rapid and diffuse release of vasoactive mediators, cytokines, and enzymes by myeloid cells minutes to hours after exposure to an inciting trigger. In mice anaphylaxis can be induced through both the classical and alternative pathways.1–3 The classical pathway depends on IgE-mediated activation of the high-affinity FcεRI on mast cells and basophils, whereas the alternative pathway depends on IgG-mediated activation of multiple myeloid cell types through Fcγ receptors (FcγRs), particularly FcγRIII. The classical pathway is well-established in human subjects, whereas the importance of the alternative pathway in human subjects is supported by considerable but not conclusive evidence.4

FcγRs regulate innate and adaptive immune responses in a coordinated manner that involves positive signals that activate cells and cause proinflammatory responses, as well as negative signals that suppress cellular activation and inflammation. Dysregulation of FcγR-mediated signaling has been implicated in wide-ranging disease processes.5–9 Murine stimulatory FcγRs include FcγRI (expressed by dendritic cells and mononuclear cell subpopulations in peripheral blood), FcγRIII (expressed in varying degrees by all peripheral blood myeloid cells), and FcγRIV (expressed by neutrophils and peripheral blood monocytes and dendritic cells).6,10 Activating FcγRs contain the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation domain (ITAM) on the Fc receptor γ chain (FcRγ). On the other hand, FcγRIIB is inhibitory because it lacks FcRγ but contains a cytosolic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory domain (ITIM) domain.6,9,11,12

Given the central role of murine activating FcγRs in IgG-mediated anaphylaxis and in several autoimmune and inflammatory disorders,13–22 the identification of a therapeutic strategy to modulate cell stimulation through FcγRs would have potential wide-ranging therapeutic implications. We previously characterized a mouse model of IgG-mediated anaphylaxis triggered by 2.4G2, a rat IgG2b mAb that directly binds to and blocks both FcγRIII and FcγRIIB but also inhibits stimulation of mouse myeloid cells through FcγRI and FcγRIV.23–25 Our data suggest that 2.4G2 inhibition of FcγRI and FcγRIV results from an interaction between 2.4G2’s Fc domains and these receptors.

These observations raised questions about the likely effects of injecting mice with an mAb that only binds to FcγRIIB, such as the mouse IgG2a allo-mAb K9.361.26 Theoretically, this mAb can inactivate myeloid cells by directly transmitting negative signals through FcγRIIB, although most evidence suggests that FcγRIIB prevents signaling through stimulatory receptors to which it has been cross-linked rather than by directly making cells refractory to other signals.27 Alternatively, K9.361 might increase the sensitivity of myeloid cells to subsequent ligation of their stimulatory receptors by blocking IgG-associated ligand cross-linking of the stimulatory receptors to FcγRIIB. A third possibility is that K9.361 might bind to stimulatory FcγRs through its Fc domains and affect the expression, responsiveness, or both of those receptors.

Distinguishing among these possibilities would provide insight into the mechanisms involved in inhibitory receptor function and the interactions among stimulatory and inhibitory receptors and might also suggest strategies for suppressing anaphylaxis and other inflammatory disorders. Consequently, we investigated the effects of injecting mice with K9.361 and its F(ab′)2 fragment, which should be capable of binding to and cross-linking FcγRIIB but lacks the Fc domains required to interact with other FcγRs. Our results indicate that K9.361 indirectly induces mild anaphylaxis through an Fc-dependent interaction with FcγRIII and then blocks active and passive IgG-mediated but not IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. In addition, treatment with K9.361 and its F(ab′)2 fragment provides an approach to safely inhibit IgG-mediated anaphylaxis.

METHODS

Mice

Male and female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY) and used at 7 to 15 weeks of age. Some experiments also used BALB/c mice that were bred in house. FcγRI- and FcγRIII-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background were originally obtained from Jeffrey Ravetch (Rockefeller University, New York, NY); these mice were bred to each other to generate mice deficient in both FcγRI and FcγRIII. F2 offspring were typed by using PCR to identify double-deficient offspring. FcγRIIB-deficient mice and FcRγ chain–deficient mice on a BALB/c background were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Me). IgE-deficient mice on a BALB/c background were a gift of Hans Oettgen (Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Mass). All transgenic mice were bred in house.

BALB/c female mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were treated intratracheally 3 times per week for 3 weeks with chicken egg white (EW) protein and assessed for airway hypersensitivity by using Buxco with gradient methacholine challenge. EW-sensitized mice were subsequently challenged by means of oral gavage with 100 mg of protein and assessed for temperature decrease and diarrhea and then grouped according to the severity of sensitization.

Antibodies, antigens, and pharmaceuticals

Monoclonal antibodies or the hybridomas that produce them were obtained as follows: K9.361 (mouse IgG2a anti-mouse FcγRIIB mAb; a gift of Ulrich Hammerling, Sloan-Kettering, New York, NY), 2.4G2 (rat IgG2b anti-mouse FcγRII/RIII mAb; ATCC, Rockville, Md), EM95 (rat IgG2a anti-mouse IgE mAb; a gift of Zelig Eshhar, Rehovot, Israel), CBPC-101 (mouse IgG2a anti-myeloma protein; John Abrams, DNAX, Palo Alto, Calif), SF1–1.1.10 (mouse IgG2a anti–H-2Kd mAb; ATCC), M1/70 (rat IgG2b anti-mouse CD11b mAb; ATCC), J1.2 (rat IgG2b anti–4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl; a gift from John Abrams, DNAX), 1B7.11 (mouse IgG1 anti–2,4,6-trinitrophenyl [TNP] mAb; ATCC), HY1.2 (mouse IgG2a anti-TNP mAb; Shozo Izui, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland; mouse IgE anti-TNP, ATCC). Monoclonal antibodies produced as ascites in pristane-primed athymic nude mice were purified, as previously described.28 A goat antiserum to mouse IgD was produced, as previously described.28 Ovalbumin (OVA) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, Mo). OVA was labeled with 2,4,6-trinitrophenyl-ε-aminocaproyl-O-succinamide (TNP-OSu; Biosearch Technologies, Petaluma, Calif). Biotinylation was achieved by alkalizing stock mAb in NaHCO3 at a pH of 8.0 and then mixing mAb with EZ Link biotin (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Mass) at a 10:1 weight ratio for 2 hours at room temperature, followed by dialysis against normal saline. Propranolol was obtained from Hikma Pharmaceuticals (London, United Kingdom). Histamine ELISA kits were purchased from IBL-America (Minneapolis, Minn).

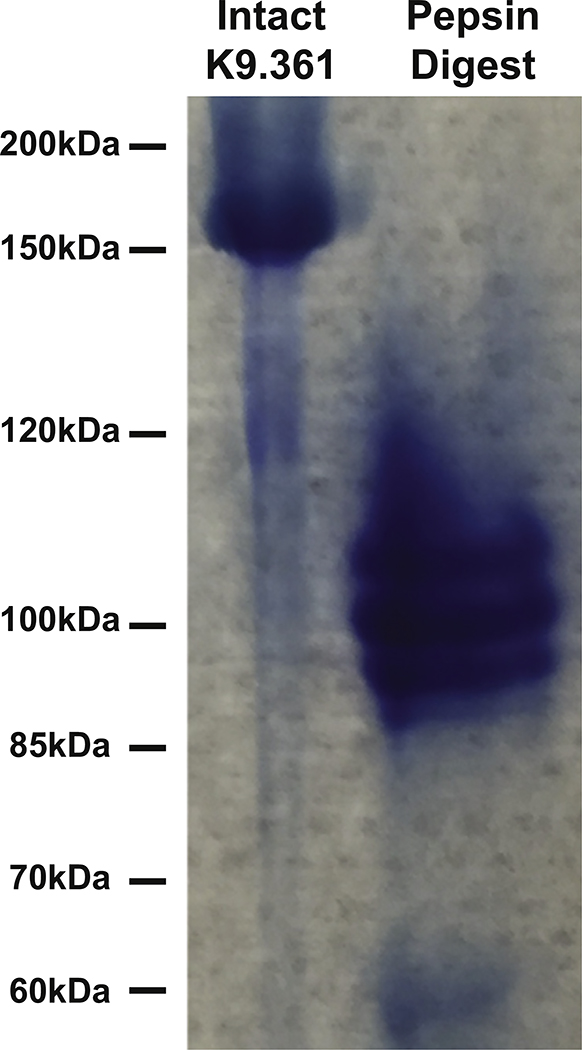

Preparation of F(ab′)2 fragments

K9.361 and 2.4G2 mAbs were digested for 7.5 hours at 37°C with immobilized pepsin (Thermo Scientific) while being rotated and then purified with the NAb Protein A Plus column (Thermo Scientific) and concentrated with centrifugal filter devices (Amicon, EMD Millipore, Norwood, Ohio). Aliquots were compared with undigested intact mAb under nonreducing conditions by using SDS-PAGE with 7% polyacrylamide gels (NuPAGE Tris-Acetate; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and lacked detectable intact IgG (see Fig E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org ).25

Detection of systemic anaphylaxis

Mice were challenged intravenously with the appropriate triggering antibody or antigen, after which serial body temperatures were determined every 5 to 15 minutes for at least 1 hour with a rectal probe to follow and quantify hypothermia, a sign of shock.13 Similar results were seen in male and female mice.

Preparation of nucleated cells

Blood obtained by means of tail vein incision was collected in microtainers that contained K2EDTA (BD Biosciences, San Jose, Calif). Red blood cells were lysed with ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer; cells were washed twice with ice-cold HN (filtered Hanks’ buffer containing 10% newborn calf serum), maintained at 4°C, and resuspended in HNA (HN plus 0.2% NaN3). Single-splenocyte suspensions were prepared, as previously described.29

Immunofluorescence staining

Peripheral blood cells (1 × 106) or splenocytes (2 × 106) in 0.1 mL of HNA were stained with 0.25 to 2 μg each of fluorochrome-labeled mAbs. Neutrophils were identified as Ly6G+ cells (BioLegend, San Diego, Calif) with relatively high forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC). Mononuclear cells were identified as B220−CD3−CD11b+ cells with relatively low FSC and SSC. Mononuclear cell subtypes were identified by using Ly6C and CD11c staining. Basophils were identified as IgE+CD117−B220−CD3− cells that had slightly higher FSC and SSC than monocytes. Alexa Fluor 594 and Alexa Fluor 647 were used, respectively, to label K9.361 and 9E9 (hamster IgG anti-mouse FcγRIV mAb; a gift of Jeffrey Ravetch, Rockefeller University, New York, NY).30 bv421-labeled mouse IgG1 anti-mouse CD64 (anti-FcγRI) was purchased from BioLegend. Fluorescence isothiocyanate–labeled rat IgG2a anti-FcγRIII was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn). The fluorochrome-labeled isotype antibodies bv421-labled mouse IgG1 (BioLegend), Alexa Fluor 594–labeled CBPC101, fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled rat IgG2a (BioLegend), and Alexa Fluor 647–labled Hamster IgG1 (BioLegend) were used as negative controls.

In some experiments cells were incubated at 4°C with 10 μg of unlabeled K9.361 before staining as an additional negative control. Cells were washed twice after staining, fixed with 2% to 4% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed with an LSR II (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed by using FACSDiva software. Similar results were generated by using cells obtained from male and female mice.

Statistics

One-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests or 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison posttesting were calculated to test for statistical significance.

RESULTS

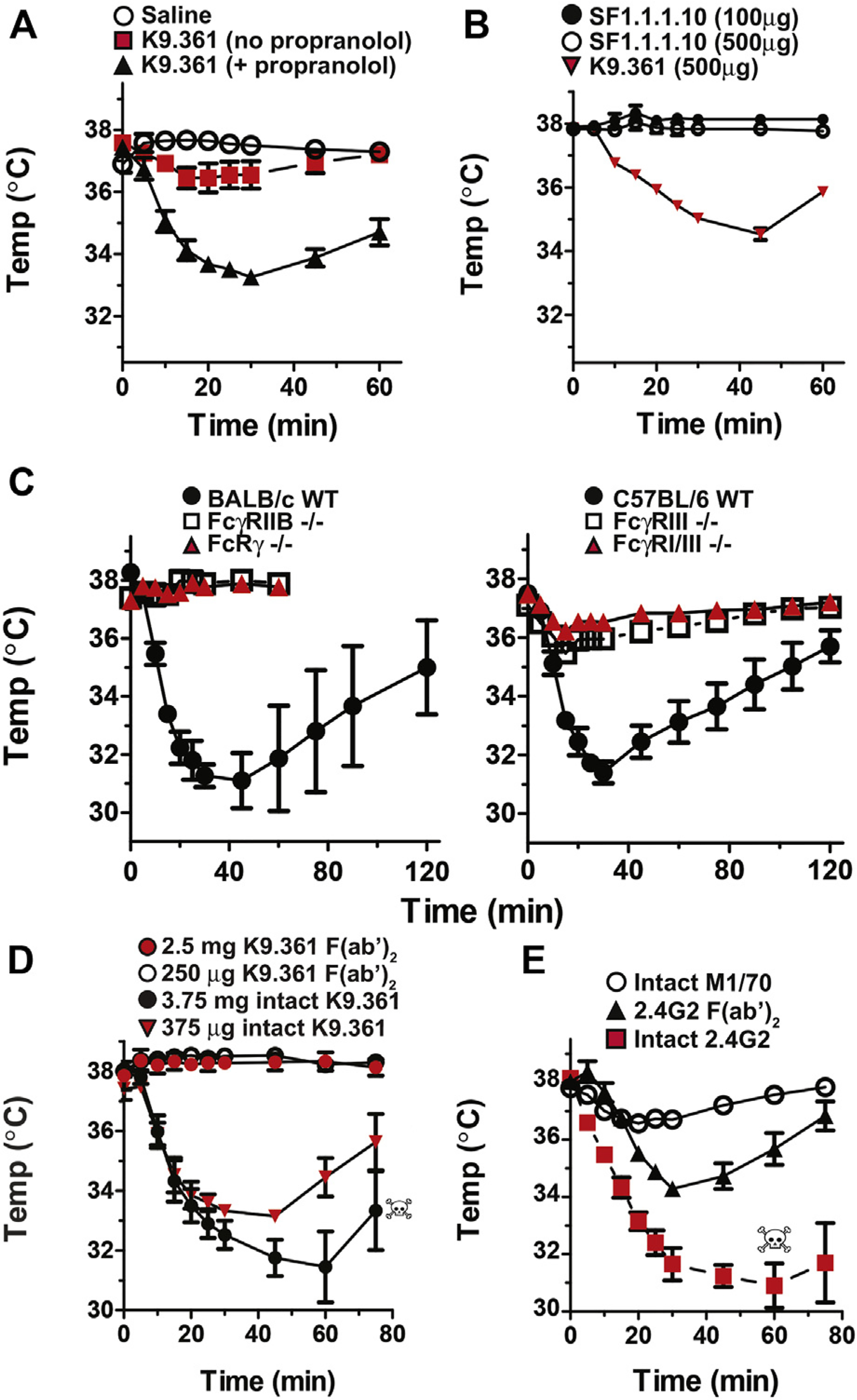

Anti-FcγRIIB mAb induces FcγRIII-dependent anaphylaxis

Our previous studies demonstrated that 2.4G2 (an mAb that binds to both the stimulatory FcγRIII and the inhibitory FcγRIIB) induces FcγRIII-dependent anaphylaxis that is manifested as shock-associated hypothermia. In contrast, we expected that K9.361, a mouse IgG2a allo-mAb that only binds directly to FcγRIIB, would block this receptor and possibly transmit a negative signal to FcγRIIB-expressing cells without inducing anaphylaxis. Surprisingly, a small temperature decrease rapidly developed in BALB/c mice injected with this mAb (Fig 1, A). Because the temperature decrease was not always greater than that observed in mice injected with saline or isotype-control mAbs, we pretreated mice with the β-adrenergic receptor antagonist propranolol, which prevents compensatory mechanisms that minimize anaphylaxis severity,31 to determine whether this would make anaphylaxis easier to appreciate. Indeed, propranolol-pretreated mice had an approximately 4°C decrease in rectal temperature in response to intravenous anti-FcγRIIB mAb (Fig 1, A) but did not have hypothermia in response to intravenous saline or intravenous injection of a mouse IgG2a alloantibody to H-2Kd (SF-1.1.1.10; Fig 1, B).

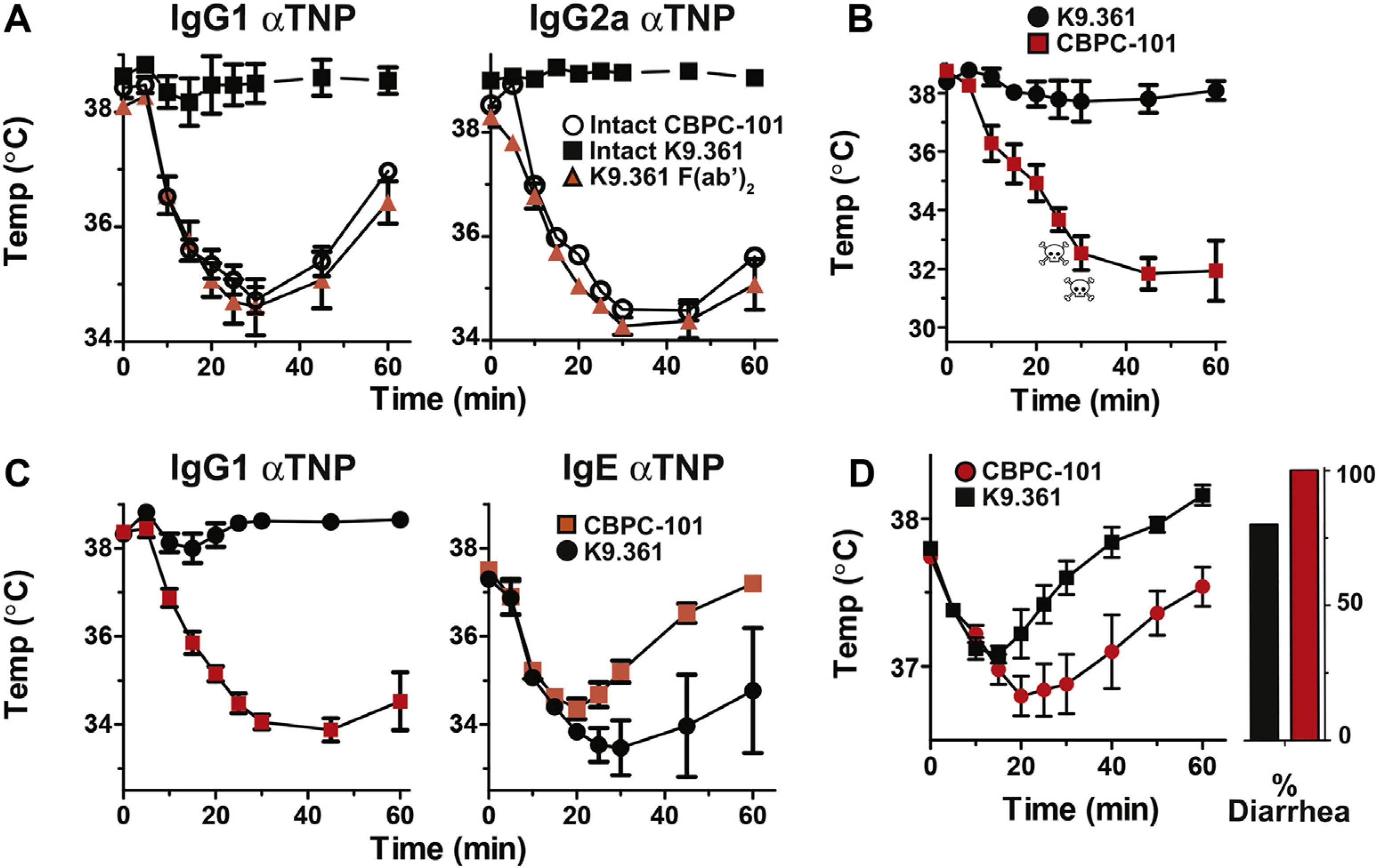

FIG 1.

IgG2a anti-FcγRIIB mAb induces FcγRIIB- and FcγRIII-dependent anaphylaxis. A, BALB/c mice were injected intravenously with saline or propranolol and 15 minutes later with saline or 500 μg of K9.361 mouse IgG2a allo–anti-FcγRIIB mAb. B, Propranolol-pretreated BALB/c mice were injected intravenously with 100 or 500 μg of SF-1.1.1.10 IgG2a allo–anti–H-2Kd mAb or 500 μg of K9.361. C, BALB/c background WT, FcRγ-deficient, and FcγRIIB-deficient and C57BL/6 background WT, FcγRIII-deficient, and FcγRI/RIII double-deficient mice were pretreated with propranolol and then injected intravenously with 500 μg of K9.361. D, BALB/c mice were pretreated with propranolol and then injected intravenously with 375 μg or 3.75 mg of intact K9.361 mAb or 250 μg of 2.5 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Injection of 5 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of mAb K9.361 was also performed and did not induce hypothermia (not shown). E, BALB/c mice were pretreated with propranolol and then injected intravenously with 100 μg of intact 2.4G2 rat IgG2b anti-mouse FcγRIIB/RIII mAb, 500 μg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of 2.4G2, or 100 μg of M1/70 rat IgG2b anti-mouse CD11b mAb. Skulls indicate deaths of individual mice. Means ± SEMs (n = 4) for serial rectal temperatures over 1 to 2 hours are shown. Similar results were seen in male and female mice.

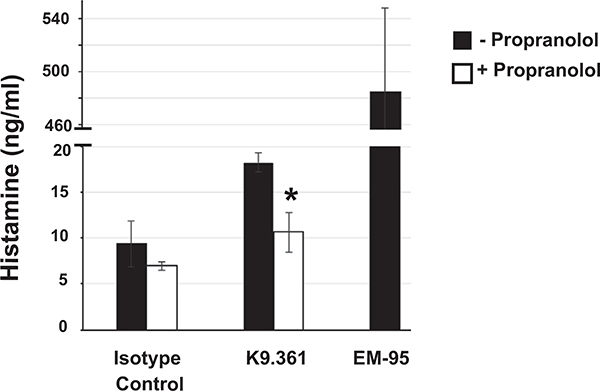

To support the interpretation that propranolol acts to suppress downstream compensatory mechanisms and not to enhance upstream mediator release, mice were treated with propranolol or saline and subsequently challenged with K9.361, the IgG2a isotype control mAb CBPC-101, or EM95 (rat IgG2a anti-IgE mAb used as a positive control for the capacity to induce histamine release). In fact, propranolol-treated mice had lower levels of plasma histamine on K9.361 challenge (see Fig E2 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Anti-FcγRIIB mAb induced anaphylaxis in propranolol-pretreated C57BL/6 mice, as well as BALB/c wild-type (WT) mice, but not in propranolol-pretreated BALB/c background mice that lack FcRγ (a required component of all stimulatory FcRs) or FcγRIIB or in C57BL/6 background FcγRIII-deficient mice or FcγRI/RIII double-deficient mice (Fig 1, C).

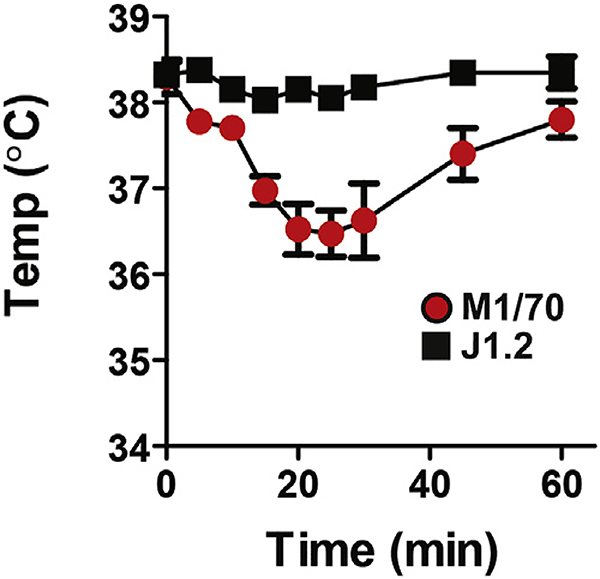

Taken together, these observations suggest that induction of anaphylaxis by anti-FcγRIIB mAb requires 2 interactions: with FcγRIIB through its antigen-binding site and with FcγRIII through its Fc domain. To confirm this, we compared the abilities of intact anti-FcγRIIB mAb and equimolar amounts of its F(ab′)2 fragment to induce hypothermia in propranolol-pretreated mice: only the intact form of this mAb had this effect, even when we varied the quantities of the intact mAb and its F(ab′)2 fragment over a 10-fold range (Fig 1, D). In contrast, the F(ab′)2 fragment of 2.4G2 induced hypothermia in propranolol-pretreated mice, although it was considerably less severe hypothermia than with intact 2.4G2, whereas the intact rat IgG2b anti-CD11b mAb M1/70, which binds to most myeloid cells and also suppresses stimulatory FcγR expression,25 induced less severe hypothermia in these mice than either intact 2.4G2 or its F(ab′)2 fragment (Fig 1, E, and see Fig E3 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

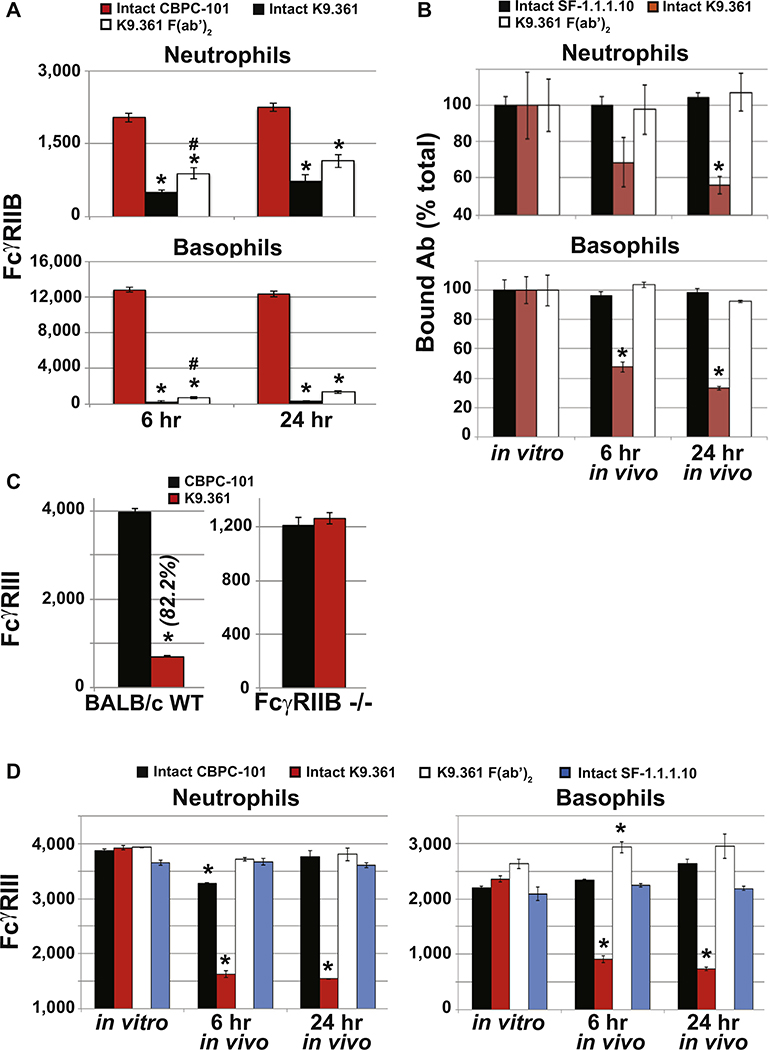

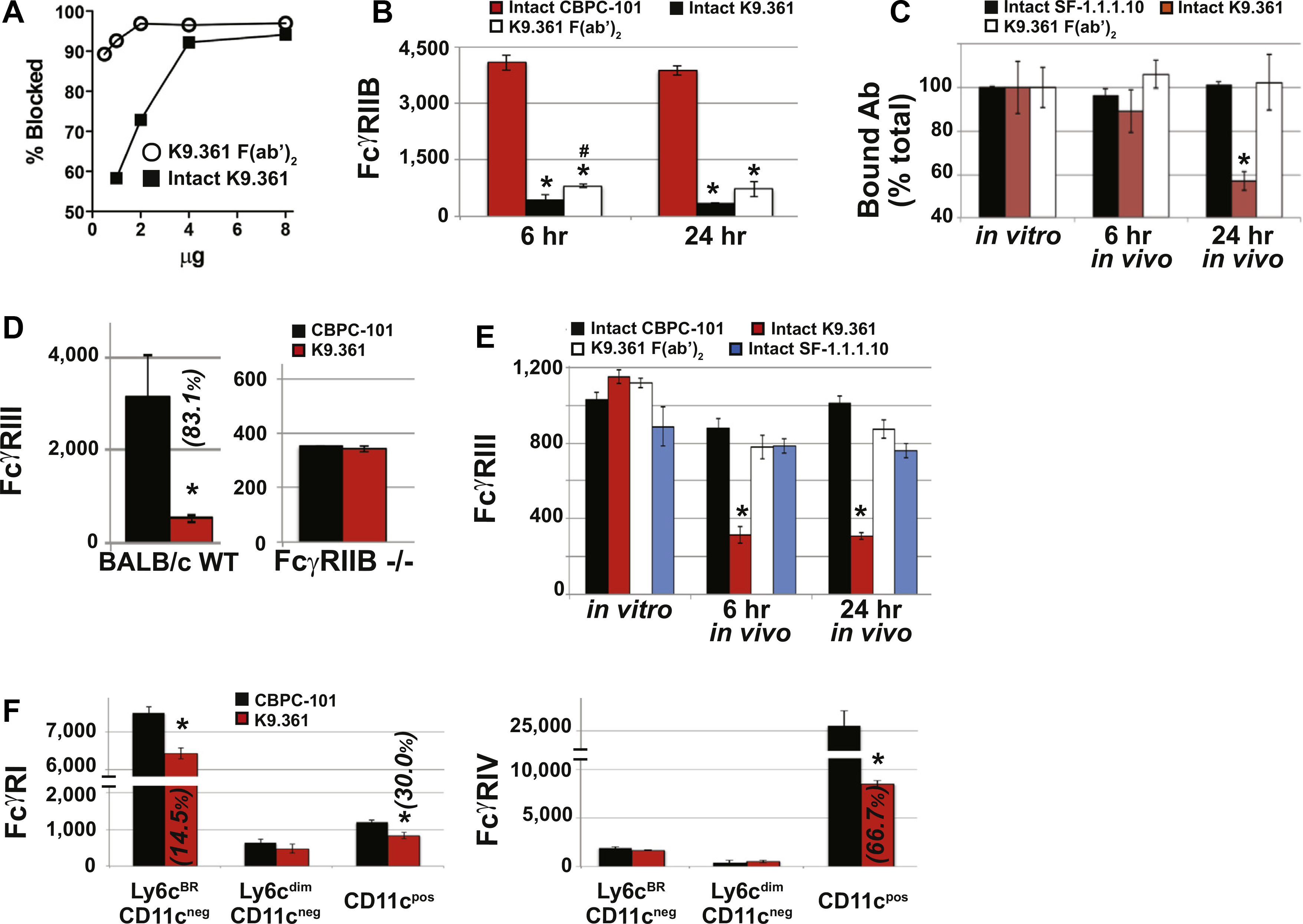

In vivo effects of anti-FcγRIIB mAb on FcγR expression

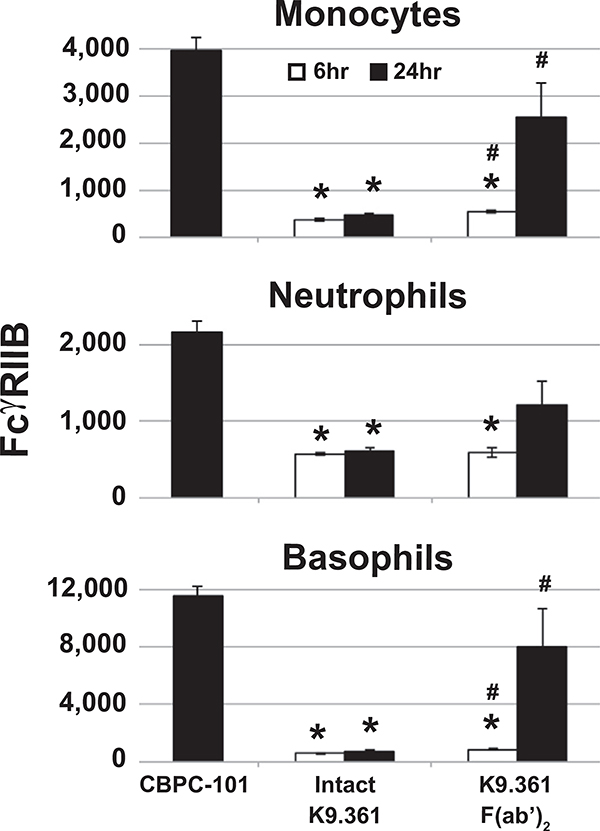

Failure of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 anti-mouse FcγRIIB mAb to induce anaphylaxis did not result from a loss of binding activity inasmuch as it was more potent on a weight basis than intact K9.361 at blocking the binding of fluorochrome-labeled intact K9.361 to FcγRIIB+ spleen cells in vitro (Fig 2, A). Consistent with this, compared with injection with CBPC-101, injection of WTBALB/c mice with intact K9.361 or its F(ab′)2 fragment suppressed ex vivo FcγRIIB staining of peripheral blood monocytes, neutrophils, and basophils (the 3 cell types implicated in IgG-mediated anaphylaxis; Fig 2, B, and see Fig E4, A, in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org ).1,25 Note that mice were injected with 500 μg of intact K9.361 but 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment to partially compensate for the decreased in vivo half-life of F(ab′)2.32 Intact K9.361 was only slightly more effective than the F(ab′)2 fragment of this mAb at blocking ex vivo staining with intact fluorochrome-labeled K9.361, and similar suppression was observed 6 and 24 hours after injection of intact K9.361 or its F(ab′)2 fragment, although relatively little F(ab′)2 of K9.361 remained in serum 24 hours after injection (see Fig E5 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Intact K9.361 also differed from its F(ab′)2 fragment in that only the former decreased the total quantity of FcγRIIB on myeloid cells after in vivo injection (Fig 2, C, and see Fig E4, B). In contrast to intact anti-FcγRIIB mAb, the intact IgG2a anti–H-2Kd allo-mAb SF-1.1.1.10 had no effect on expression of its ligand on myeloid cells.

FIG 2.

K9.361 effects on myeloid cell FcγR expression. A, Isolated splenocytes were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with increasing amounts of intact K9.361 or K9.361-derived F(ab′)2 or without mAb (control) and then stained with fluorochrome-labeled intact K9.361. Percentage decrease in mean fluorescence intensity (compared with control values) is shown. B, Mice received 500 μg of CBPC-101 (mouse IgG2a isotype control mAb), 500 μg of intact K9.361, or 1 mg of K9.361-derived F(ab′)2 intravenously. Six and 24 hours later, PBMCs were stained with fluorochrome-labeled K9.361. Mean ± SEM MFIs are shown. *P < .005 compared with CBPC-101; #P < .05 compared with intact K9.361. C, Mice received 500 μg of intact biotin-labeled K9.361 or biotin-labeled SF-1.1.1.10 or 1 mg of biotin-labeled K9.361-derived F(ab′)2 intravenously. PBMCs at 6 and 24 hours were stained with labeled streptavidin. Control PBMCs from untreated mice were incubated in vitro with 20 μg of intact biotin-labeled K9.361, SF-1.1.1.10, or K9.361-derived F(ab′)2 for 30 minutes at 4°C. Mean ± SEM ratios (MFI relative to controls for the given mAb) are shown. *P < .01, 1-way ANOVA with posttest. D, WT and FcγRIIB-deficient mice received 500 μg of intact K9.361 or CBPC-101 intravenously, and PBMCs at 24 hours were stained for FcγRIII. Mean ± SEM MFIs are shown. *P < .005 compared with CBPC-101. E, Mice received 500 μg of CBPC-101, intact K9.361, or SF-1.1.1.10 or 1 mg of K9.361-derived F(ab′)2 intravenously, and PBCMs at 6 or 24 hours were stained for FcγRIII. Mean ± SEM MFIs are shown. (*P < .01, 1-way ANOVA with posttest). F, Mice received 500 μg of intact K9.361 or CBPC-101. Mononuclear cell subpopulations isolated at 24 hours were classified based on Ly6c and CD11c expression and stained for FcγRI and FcγRIV. Mean ± SEM MFIs are shown. (*P < .005). For Fig 2, D and F, percentage decrease in MFI is shown in parentheses. BALB/c background mice (at least 4 per group) were used.

In addition to decreasing FcγRIIB expression, intact K9.361 also induced loss of most FcγRIII on myeloid cells in vivo, an effect not observed in FcγRIIB-deficient mice, indicating that anti-FcγRIIB mAb binding to cells through its antigen-binding site is essential for its downmodulation of FcγRIII (Fig 2, D, and see Fig E4, C). As predicted, the F(ab′)2 fragment of anti-FcγRIIB mAb and intact CBPC-101 had no in vivo effect on the expression of FcγRIII (Fig 2, E, and see Fig E4, D). Intact mouse IgG2a anti–H-2Kd mAb also had no effect on FcγRIII expression, even though its Fc domains should be able to interact with this receptor (Fig 2, E, and see Fig E4, D).

An additional experiment evaluated the ability of intact anti-FcγRIIB mAb to affect expression of FcγRI and FcγRIV, which are expressed on some mononuclear populations and on mononuclear cells, as well as neutrophils, respectively.10 Although there appeared to be some decreases in expression of these stimulatory FcγRs (Fig 2, F), they were variable, cell type dependent, and considerably less than those observed for FcγRIII. This might reflect the higher affinity of FcγRI and FcγRIV than FcγRIII for uncomplexed IgG antibody molecules,10,30 which would allow endogenous serum IgG to better inhibit an interaction between the Fc of FcγRIIB-bound K9.361 with FcγRI and FcγRIV than with FcγRIII.

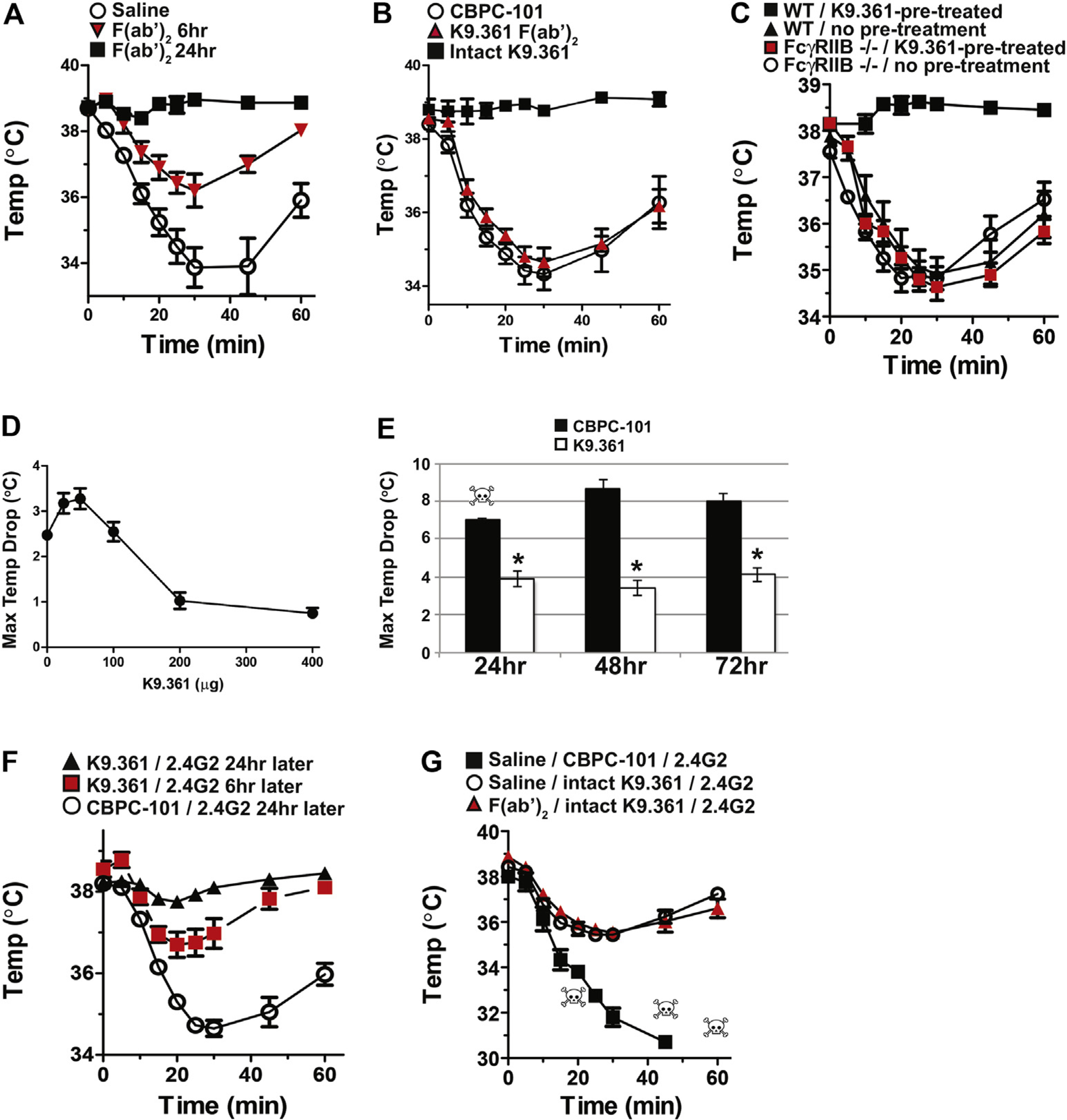

Inhibition of anaphylaxis by anti-FcγRIIB mAb

The ability of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 to bind to FcγRIIB without interacting with stimulatory FcγRs or inducing anaphylaxis, even in propranolol-pretreated mice, and the ability of intact K9.361 to cross-link FcγRIIB, modulate most FcγRIII from myeloid cells, and induce mild anaphylaxis suggested that they might differ in their abilities to inhibit subsequent FcγR-mediated anaphylaxis. To test this, we first treated WT mice with 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 and then, 6 or 24 hours later, treated these mice with propranolol and injected them with intact K9.361. Pretreatment with the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 strongly suppressed the anaphylactic response to intact K9.361 6 hours later and totally blocked anaphylaxis when the intact mAb was injected 24 hours after the F(ab′)2 fragment (Fig 3, A). In contrast, pretreatment of WT mice with intact K9.361 but not with its F(ab′)2 fragment suppressed completely the hypothermia response to intact 2.4G2 (anti-FcγRIIB/RIII mAb) in mice that were not treated with propranolol (Fig 3, B). As expected, K9.361 suppression of the anaphylactic response to 2.4G2 was FcγRIIB dependent (Fig 3, C), reflecting the FcγRIIB requirement for K9.361 binding to cells and was dose dependent (Fig 3, D). A single injection of intact K9.361 suppressed the anaphylactic response to 2.4G2, even when 2.4G2 was given in the presence of propranolol, for at least 3 days (Fig 3, E). K9.361 significantly suppressed 2.4G2-mediated anaphylaxis 6 hours after intravenous injection and protection increased 24 hours after injection (Fig 3, F).

FIG 3.

Suppression of IgG-mediated anaphylaxis by anti-FcγRIIB mAb. A, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with saline or with 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Mice were injected intravenously 6 or 24 hours later with propranolol, followed 15 minutes later by intravenous injection of 500 μg of intact K9.361. B, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of intact CBPC-101 or K9.361 or with 5 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Mice were challenged intravenously 24 hours later with 500 μg of 2.4G2. C, BALB/c background WT and FcγRIIB-deficient mice (4 per group) were pretreated by means of intravenous injection with 500 μg of intact CBPC-101 or K9.361 and challenged intravenously 24 hours later with 500 μg of 2.4G2. In Fig 3, A–C, Rectal temperatures were followed for the next hour after challenge, and means ± SEMs are shown. D, BALB/c mice (3 per group) were injected intravenously with the doses of K9.361 shown and challenged 24 hours later with 500 μg of 2.4G2. Maximum temperature decreases ± SEM during the following hour are shown. E, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of intact CBPC-101 or K9.361 followed 24, 48, or 72 hours later by intravenous injection of propranolol and 15 minutes later by intravenous injection of 100 μg of 2.4G2. Rectal temperatures were followed for the next 2 hours, and mean ± SEM maximum temperature decreases are shown. F, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of intact CBPC-101 or K9.361, followed 6 or 24 hours later by intravenous injection of 500 μg of 2.4G2. Rectal temperatures were followed for the next hour, and means ± SEM are shown. G, BALB/c mice (3 per group) were injected intravenously with saline or 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Twenty-four hours later, mice were injected intravenously with 500 μg of intact CBPC-101 or K9.361. After an additional 24 hours, mice were injected intravenously with propranolol, followed 15 minutes later by intravenous injection of 100 μg of 2.4G2. Rectal temperatures were followed for the next hour, and means ± SEMs are shown. Skulls indicate individual mouse deaths.

These observations suggest that suppression of the anaphylactic response to 2.4G2 might be accomplished without even the mild anaphylaxis that is induced by intact K9.361 by serially injecting mice with F(ab′)2 of K9.361, then intact K9.361, and finally 2.4G2. This was indeed the case. Even in mice that were treated with propranolol, initial treatment with F(ab′)2 of K9.361 did not diminish the ability of intact K9.361 to inhibit 2.4G2-induced hypothermia (Fig 3, G).

Intact anti-FcγRIIB mAb blocks active and passive IgG-mediated anaphylaxis

Suppression of 2.4G2-induced anaphylaxis by pretreatment with intact K9.361 but not its F(ab′)2 fragment suggested that treatment with intact anti-FcγRIIB mAb might be able to suppress antigen-induced IgG-mediated anaphylaxis. To test this, mice were pretreated with 500 μg of intact K9.361 or CBPC-101 or 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Twenty-two hours later, mice were passively sensitized for IgG-mediated anaphylaxis by means of injection of 500 μg of IgG1 or IgG2a anti-TNP mAb and then challenged intravenously 2 hours later with 100 μg of TNP-OVA in the absence of propranolol. Pretreatment with intact K9.361 completely suppressed IgG1- and IgG2a-mediated anaphylaxis, whereas pretreatment with the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 had no effect on the anaphylactic response (Fig 4, A). BALB/c background IgE-deficient mice were immunized with goat anti-mouse IgD antiserum, which stimulates a very large IgG1 anti-goat IgG antibody response, to determine whether intact K9.361 would also suppress IgG-mediated anaphylaxis in actively sensitized mice.33,34 Thirteen days later, mice were treated with 500 μg of intact K9.361 or CBPC-101 and then challenged intravenously 1 day after that with 100 μg of goat IgG. Severe anaphylaxis developed in the mice that had been treated with the control mAb, whereas no hypothermia was seen in the K9.361-treated mice (Fig 4, B).

FIG 4.

Treatment with anti-FcγRIIB mAb suppresses passive and active IgG-mediated anaphylaxis. A, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of intact CBPC-101 or K9.361 or with 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Mice were passively sensitized 22 hours later by means of intraperitoneal injection of 500 μg of IgG1 or IgG2a anti-TNP mAb and challenged 2 hours after that by means of intravenous injection of 100 μg of TNP-OVA. Rectal temperatures were followed for the next hour. B, BALB/c background IgE-deficient mice were actively immunized by means of subcutaneous injection of 200 μL of goat anti-mouse IgD antiserum. Mice were injected intravenously 13 days later with 500 μg of CBPC-101 (n = 5) or K9.361 (n = 6) and challenged intravenously 1 day later with 100 μg of goat IgG. Rectal temperatures were followed for the next hour. C, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of CBPC-101 or K9.361. Mice were passively sensitized 20 hours later by means of intravenous injection with 500 μg of IgG1 anti-TNP mAb or with 10 μg of IgE anti-TNP and challenged 4 hours later by means of intravenous injection of 100 μg of TNP-OVA. Rectal temperatures were followed for the next hour. Means ± SEM are shown. D, BALB/c WT mice (n = 5) were sensitized to EW by means of intratracheal inoculation and then injected intravenously with 500 μg of CBPC-101 or K9.361 24 hours before oral gavage with 100 μg EW. Rectal temperatures ± SEM and the percentage of mice that experienced diarrhea are shown. Skulls indicate deaths of individual mice.

Because FcγRIIB is present on mast cells and basophils and can inhibit IgE-mediated anaphylaxis, we determined whether K9.361 can suppress or exacerbate IgE-mediated anaphylaxis. BALB/c WT mice were treated with 500 μg of K9.361 or CBPC-101 and then passively sensitized 20 hours later by means of intravenous injection of 500 μg of IgG1 anti-TNP or 10 μg of IgE anti-TNP and challenged intravenously 4 hours later with 100 μg of TNP-OVA. K9.361 protected against IgG1-mediated anaphylaxis but not IgE-mediated anaphylaxis (Fig 4, C).

Because the binding of IgG-containing immune complexes to FcγRIIB can suppress IgE-mediated anaphylaxis, it was possible that K9.361 blocking of FcγRIIB might exacerbate IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in an active sensitization model in which mice produced both IgG and IgE antibodies to the immunogen. To evaluate this, we studied mice that had been sensitized intratracheally with EW and then challenged repeatedly with EW by means of oral gavage until they had both diarrhea and hypothermia in response to oral gavage EW. Although mice immunized by using this protocol generate both IgE and IgG anti-EW antibodies, the diarrhea and hypothermia responses to oral EW challenge are entirely IgE dependent. Intravenous treatment of these mice with EW allergy with 500 μg of K9.361, followed 24 hours later by oral gavage with 100 mg of EW, slightly ameliorated anaphylaxis severity (Fig 4, D).

DISCUSSION

Anaphylaxis is induced in mice and most likely in human subjects through aggregation of stimulatory FcγRs by IgG-containing immune complexes.4 We have now shown that K9.361, an IgG2a mAb that binds to and cross-links the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIB, also induces mild anaphylaxis, which becomes severe when homeostatic compensatory mechanisms that depend on β-adrenergic receptors are blocked. Induction of anaphylaxis requires binding of K9.361 to cells through its antigen-binding site because this mAb does not induce anaphylaxis in FcγRIIB-deficient mice. It also requires binding to FcγRIII through this mAb’s Fc domain because it does not induce anaphylaxis in FcγRIII- or FcγR-deficient mice. The induction of anaphylaxis by K9.361 is accompanied by and probably depends on FcγRIII cross-linking because this mAb both decreases the quantity of FcγRIIB expressed by myeloid cells and removes approximately 80% of FcγRIII from these cells, whereas its F(ab′)2 fragment, which does not induce anaphylaxis, has neither effect. This dependence on stimulatory FcγR cross-linking is also suggested by the inability of SF-1.1.1.10, an IgG2a mAb to H-2Kd (an antigen that is strongly expressed by cells that express FcγRIIB), to induce anaphylaxis or decrease the expression of H-2Kd or FcγRIII on myeloid cells (Figs 1, B; 2, C; and 2, E).

Although previous studies have shown that mAbs that bind to one FcγR or other cell-surface targets can interact with other FcγRs through their Fc domains and that this can affect cell function,25,35–39 ours provides the first evidence that antibody binding of an inhibitory receptor through the antibody’s F(ab) domain can activate cells through an interaction between that antibody’s Fc domain and a stimulatory receptor. These observations have important implications for the clinical use of IgG mAbs to cell membrane molecules that can also interact with stimulatory FcγRs on those cells. Our observations also demonstrate that even though FcγRIIB inhibits cell signaling through activation of its ITIM, these inhibitory effects in our model are inadequate to totally suppress anaphylaxis if FcγRIII is also activated. Thus the stimulatory signaling of the FcγRIII-associated ITAM can dominate the inhibitory effects of the FcγRIIB-associated ITIM.

Our observations also establish the ability of the K9.361 anti-FcγRIIB mAb to inhibit anti-FcγRIIB/RIII mAb (2.4G2)–induced anaphylaxis, as well as IgG-mediated anaphylaxis induced by antigen challenge of actively or passively sensitized mice. More than 1 mechanism can be involved in this suppressive effect. First, the loss of approximately 80% of FcγRIII by myeloid cells in K9.361-treated mice might diminish the ability of FcγRIII cross-linking to induce anaphylaxis. However, this effect is probably not sufficient to suppress IgG-mediated anaphylaxis because treating mice with M1/70 rat IgG2b anti-mouse CD11b mAb does not inhibit IgG-mediated anaphylaxis, even though it substantially decreases myeloid cell FcγRIII expression.25 Additional possible mechanisms for suppression of IgG-mediated anaphylaxis are (1) negative signaling through FcγRIIB or (2) anergy induction by co–cross-linking of FcγRIIB with FcγRIII, thereby establishing a refractory state with potentially fewer available mediators for secretion. These possibilities are consistent with the considerable time required for maximal suppression of 2.4G2-induced anaphylaxis by K9.361 (greater after 24 hours than after 6 hours; Fig 3, F) and might in part explain K9.361-mediated protection in IgE-mediated anaphylaxis to food protein challenge (Fig 4, D).

The inhibitory effects of FcγRIIB generally depend on coaggregation of this inhibitory receptor with stimulatory receptors through a common surface ligand and the ensuing recruitment of SH2-containing inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase 1, which terminates ITAM-induced phosphoinositide 3-kinase–mediated signaling.40,41 This might explain the failure of intact K9.361 to strongly suppress IgE-mediated anaphylaxis (Fig 4, C). Although this mAb binds FcγRIIB, which is expressed on mouse basophils and mast cells, its Fc domains will not interact with the FcγRI on these cells. Because mouse mast cells and basophils also express FcγRIII, which mediates the participation of these cells in IgG-mediated anaphylaxis, the strong suppression of IgG-but not IgE-mediated anaphylaxis by K9.361 suggests that this suppression is stimulatory Fc receptor specific rather than a result of global desensitization of specific cell types.

The inability of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 to suppress IgG-mediated anaphylaxis could reflect its failure to bind to and activate FcγRIII to decrease FcγRIII expression and/or its limited ability to activate SH2-containing inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase 1 by cross-linking FcγRIIB. Although the F(ab′)2 fragment of an IgG antibody, like the intact antibody, is divalent and consequently has the potential to cross-link its ligand, F(ab′)2 fragments of IgG antibodies are less potent than intact IgG antibodies at cross-linking their ligands in vivo.39 The aggregation of IgG-bound molecules on one cell is enhanced by IgG-Fc interactions with FcγRs on adjacent cells and by Fc-dependent interactions with C1q.42 The greater cross-linking ability of intact K9.361 than its F(ab′)2 fragment is most likely required for the intact antibody’s ability to decrease FcγRIIB and FcγRIII expression (Fig 2, B) through the endocytosis of antibody receptor aggregates.

One result of our study that is somewhat difficult to explain is the ability of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 to cause relatively slow (>6 hours) time-dependent suppression of the response to intact K9.361 (Fig 3, A) without suppressing the anaphylactic response to 2.4G2 (Fig 3, B) or antigen-induced and IgG-mediated anaphylaxis (Fig 4, A).

The time dependence of the suppressive effect cannot be explained by the time required for the F(ab′)2 fragment to saturate its ligand because blocking of intact K9.361 binding to myeloid cells is at least as great 6 hours after F(ab′)2 injection as it is 18 hours later (Fig 2, B), when suppression of anaphylaxis induction by intact K9.361 is considerably greater (Fig 3, A). It is possible that F(ab′)2 binding to FcγRIIB in the absence of FcγRIIB cross-linking to a stimulatory receptor has a cumulative suppressive effect on subsequent activation of stimulatory receptors, including FcγRIII. However, the failure of 24 hours of treatment with the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 to inhibit FcγRIII-dependent anaphylaxis induction by 2.4G2 suggests that this putative inhibitory effect would have to be quite limited. An alternative possibility is that cross-linking of FcγRIIB by the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 physically separates FcγRIIB from FcγRIII on the cell membrane, so that the Fc domain of intact K9.361 that has bound to FcγRIIB is less likely to bind FcγRIII.

Regardless of the explanation for this phenomenon, the ability of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 to prevent any anaphylactic response to intact K9.361 and the ability of intact K9.361 to prevent antigen-induced and IgG-mediated anaphylaxis suggests that sequential treatment with the F(ab′)2 fragment of anti-FcγRIIB mAb, followed by treatment with the intact mAb, provides a safe way to suppress IgG-mediated anaphylaxis (Fig 3, G) and, possibly, other FcγR-mediated immune disorders.

Key messages.

K9.361, an IgG2a anti-FcγRIIB mAb, inhibits IgG-mediated anaphylaxis in mice through a mechanism that involves cross-linking of FcγRIIB with stimulatory FcγRs. K9.361 has relatively little effect on IgE-mediated anaphylaxis.

Although intact K9.361, in the presence of β-blocker, induces mild anaphylaxis through interaction primarily with FcγRIII, this can be inhibited by first treating mice with K9.361-derived F(ab′)2.

This study contributes to the understanding of potential interactions between activating and inhibitory FcγRs, which are considered valuable therapeutic targets in patients with wide-ranging allergic and inflammatory disorders.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 AI113162, a Merit Award to F.D.F. from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the NIH-supported Immunology/Allergy Fellowship Training Program (T32AI060515-11), and the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Cincinnati Medical Center.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest:

C. D. Clay receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). F. D. Finkelman serves as a consultant for Vedanta Bioscience, is an employee of the University of Cincinnati, receives grant support from the NIH and Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE), and has 3 patents pending with the University of Cincinnati. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used

- EW

Chicken egg white

- FcγR

Fcγ receptor

- FcRγ

Fc receptor γ chain

- FSC

Forward scatter

- ITAM

Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation domain

- ITIM

Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory domain

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- OVA

Ovalbumin

- SSC

Side scatter

- TNP

2,4,6-Trinitrophenyl

- WT

Wild-type

FIG E1.

The F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 is devoid of intact mAb. Intact K9.361 mAb and product obtained after digestion with immobilized pepsin followed by Fc removal with protein A were analyzed by means of SDS-PAGE with 7% polyacrylamide gels under nonreducing conditions. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue. The band migrating between 150 and 200 kDa on the left is the typical size for intact mouse IgG2a. F(ab′)2 fragments are typically 100 to 110 kDa, and F(ab) fragments are typically 50 kDa. The band on the right represents F(ab′)2.

FIG E2.

Pretreatment with β-blocker does not enhance plasma histamine levels after challenge with anti-FcγRIIB mAb. BALB/c WT mice (n = 4) received saline or 35 μg of propranolol administered intravenously before receiving 500 μg of CBPC-101 (isotype control) or K9.361 intravenously or 50 μg of EM95 (rat IgG2a anti-mouse IgE mAb that generates robust histamine responses in vivo) intravenously. Plasma histamine concentrations 10 minutes after in vivo treatment ± SEM are shown. *P < .05.

FIG E3.

Mild shock is induced by M1/70 and not J1.2. BALB/c WT mice (n = 4) received propranolol, followed by injection with 100 μg of M1/70 or J1.2 (rat IgG2b isotype control mAb). Mean ± SEM serial rectal temperatures are shown.

FIG E4.

K9.361 effects on FcγRIIB and FcγRIII expression on neutrophils and basophils. A, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of CBPC-101 or intact K9.361 or 1 mg of K9.361 F(ab′)2. Six and 24 hours later, peripheral blood cells were stained to identify neutrophils and basophils and with fluorochrome-labeled K9.361. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SEM is shown. *P < .005 compared with CBPC-101; #P < .05 compared with K9.361. B, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of intact biotin-labeled K9.361 or biotin-labeled SF-1.1.1.10 or 1 mg of the biotin-labeled F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Peripheral blood cells obtained 6 and 24 hours later were stained to identify neutrophils and basophils and with fluorochrome-labeled streptavidin. Additional cells from untreated mice were treated in vitro with 20 μg of intact biotin-labeled K9.361, SF-1.1.1.10, or the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 for 30 minutes at 4°C and then stained with fluorochrome-labeled streptavidin. Data show mean ± SEM ratios (MFI relative to MFI on cells from untreated mice that were stained with the same mAbs in vitro). *P < .001, 1-way ANOVA with posttest. C, BALB/c background WT and FcγRIIB-deficient mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of intact K9.361 or CBPC-101. Neutrophils obtained 24 hours later were stained with fluorochrome-labeled anti-mouse FcγRIII. Mean ± SEM MFIs are shown. *P < .005 compared with isotype control. Percentage decrease in mean MFI compared with isotype controls is shown in parentheses. D, BALB/c mice (4 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of CBPC-101, intact K9.361, or SF-1.1.1.10 or with 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Neutrophils and basophils obtained 6 or 24 hours later were stained for FcγRIII, and mean ± SEM MFIs are shown. *P < .001, 1-way ANOVA with posttest.

FIG E5.

Decreased half-life of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361 versus intact K9.361. BALB/c mice (3 per group) were injected intravenously with 500 μg of CBPC-101, intact K9.361, or 1 mg of the F(ab′)2 fragment of K9.361. Six or 24 hours later, peripheral blood was obtained and centrifuged to produce serum. Pooled peripheral myelocytes from WT BALB/c mice treated with CBPC-101 were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with 20 μL of serum taken from antibody-injected mice; washed; stained with fluorochrome-labeled K9.361 and markers for monocytes, neutrophils, and basophils; and analyzed by means of flow cytometry. Mean ± SEM MFIs are shown. *P < .05 compared with CBPC-101 controls; #P < .05 compared with intact K9.361.

Footnotes

The CrossMark symbol notifies online readers when updates have been made to the article such as errata or minor corrections

REFERENCES

- 1.Strait RT, Morris SC, Yang M, Qu X-W, Finkelman FD. Pathways of anaphylaxis in the mouse. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;109:658–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strait RT, Morris SC, Finkelman FD. IgG-blocking antibodies inhibit IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in vivo through both antigen interception and FcγRIIb cross-linking. J Clin Invest 2006;116:833–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oettgen HC, Martin TR, Wynshaw-Boris A, Deng C, Drazen JM, Leder P. Active anaphylaxis in IgE-deficient mice. Nature 1994;370:367–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelman FD, Khodoun MV, Strait R. Human IgE-independent systemic anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137:1674–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcγ receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruhns P Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood 2012;119:5640–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boruchov AM, Heller G, Veri MC, Bonvini E, Ravetch JV, Young JW. Activating and inhibitory IgG Fc receptors on human DCs mediate opposing functions. J Clin Invest 2005;115:2914–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boross P, Arandhara VL, Martin-Ramirez J, Santiago-Raber ML, Carlucci F, Flierman R, et al. The inhibiting Fc receptor for IgG, FcγRIIB, is a modifier of autoimmune susceptibility. J Immunol 2011;187:1304–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clynes R, Maizes JS, Guinamard R, Ono M, Takai T, Ravetch JV. Modulation of immune complex-induced inflammation in vivo by the coordinate expression of activation and inhibitory Fc receptors. J Exp Med 1999;189:179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruhns P, Jonsson F. Mouse and human FcR effector functions. Immunol Rev 2015;268:25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillis C, Gouel-Cheron A, Jonsson F, Bruhns P. Contribution of human FcγRs to disease with evidence from human polymorphisms and transgenic animal studies. Front Immunol 2014;5:254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Getahun A, Cambier JC. Of ITIMs, ITAMs, and ITAMis: revisiting immunoglobulin Fc receptor signaling. Immunol Rev 2015;268:66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyajima I, Dombrowicz D, Martin TR, Ravetch JV, Kinet JP, Galli SJ. Systemic anaphylaxis in the mouse can be mediated largely through IgG1 and FcγRIII. Assessment of the cardiopulmonary changes, mast cell degranulation, and death associated with active or IgE- or IgG1-dependent passive anaphylaxis. J Clin Invest 1997;99:901–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe N, Akikusa B, Park SY, Ohno H, Fossati L, Vecchietti G, et al. Mast cells induce autoantibody-mediated vasculitis syndrome through tumor necrosis factor production upon triggering Fcγ receptors. Blood 1999;94:3855–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radeke HH, Janssen-Graalfs I, Sowa EN, Chouchakova N, Skokowa J, Loscher F, et al. Opposite regulation of type II and III receptors for immunoglobulin G in mouse glomerular mesangial cells and in the induction of anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) nephritis. J Biol Chem 2002;277:27535–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ioan-Facsinay A, de Kimpe SJ, Hellwig SM, van Lent PL, Hofhuis FM, van Ojik HH, et al. FcγRI (CD64) contributes substantially to severity of arthritis, hypersensitivity responses, and protection from bacterial infection. Immunity 2002;16:391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto T, Ishii N, Ohata C, Furumura M. Pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, an autoimmune subepidermal bullous disease. J Pathol 2012; 228:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gessner JE, Heiken H, Tamm A, Schmidt RE. The IgG Fc receptor family. Ann Hematol 1998;76:231–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fossati-Jimack L, Ioan-Facsinay A, Reininger L, Chicheportiche Y, Watanabe N, Saito T, et al. Markedly different pathogenicity of four immunoglobulin G isotype-switch variants of an antierythrocyte autoantibody is based on their capacity to interact in vivo with the low-affinity Fcγ receptor III. J Exp Med 2000;191:1293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergtold A, Gavhane A, D’Agati V, Madaio M, Clynes R. FcR-bearing myeloid cells are responsible for triggering murine lupus nephritis. J Immunol 2006;177: 7287–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baudino L, Nimmerjahn F, Azeredo da Silveira S, Martinez-Soria E, Saito T, Carroll M, et al. Differential contribution of three activating IgG Fc receptors (FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV) to IgG2a- and IgG2b-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia in mice. J Immunol 2008;180:1948–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandukwala HS, Clay BS, Tong J, Mody PD, Cannon JL, Shilling RA, et al. Signaling through FcγRIII is required for optimal T helper type (Th)2 responses and Th2-mediated airway inflammation. J Exp Med 2007;204:1875–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unkeless JC. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody directed against mouse macrophage and lymphocyte Fc receptors. J Exp Med 1979;150:580–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirano M, Davis RS, Fine WD, Nakamura S, Shimizu K, Yagi H, et al. IgEb immune complexes activate macrophages through FcγRIV binding. Nat Immunol 2007;8:762–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khodoun MV, Kucuk ZY, Strait RT, Krishnamurthy D, Janek K, Clay CD, et al. Rapid desensitization of mice with anti-FcγRIIb/FcγRIII mAb safely prevents IgG-mediated anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:1375–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura S, Tada N, Nakayama E, Liu Y, Hammerling U. A new mouse cell-surface antigen (Ly-m20) controlled by a gene linked to Mls locus and defined by monoclonal antibodies. Immunogenetics 1981;14:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muta T, Kurosaki T, Misulovin Z, Sanchez M, Nussenzweig MC, Ravetch JV. A 13-amino-acid motif in the cytoplasmic domain of FcγRIIB modulates B-cell receptor signalling. Nature 1994;368:70–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finkelman FD, Kessler SW, Mushinski JF, Potter M. IgD-secreting murine plasmacytomas: identification and partial characterization of two IgD myeloma proteins. J Immunol 1981;126:680–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khodoun MV, Kucuk ZY, Strait RT, Krishnamurthy D, Janek K, Lewkowich I, et al. Rapid polyclonal desensitization with antibodies to IgE and FcεRIα. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:1555–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nimmerjahn F, Bruhns P, Horiuchi K, Ravetch JV. FcγRIV: a novel FcR with distinct IgG subclass specificity. Immunity 2005;23:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khodoun M, Strait R, Orekov T, Hogan S, Karasuyama H, Herbert DR, et al. Peanuts can contribute to anaphylactic shock by activating complement. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:342–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chames P, Van Regenmortel M, Weiss E, Baty D. Therapeutic antibodies: successes, limitations and hopes for the future. Br J Pharmacol 2009;157:220–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svetic A, Finkelman FD, Jian YC, Dieffenbach CW, Scott DE, McCarthy KF, et al. Cytokine gene expression after in vivo primary immunization with goat antibody to mouse IgD antibody. J Immunol 1991;147:2391–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Champion BR, Buckham S, Page K, Obray H, Zanders ED. Secondary immunoglobulin responses of BALB/c mice previously stimulated with goat anti-mouse IgD. Immunology 1991;72:336–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tipton TR, Mockridge CI, French RR, Tutt AL, Cragg MS, Beers SA. Anti-mouse FcγRIV antibody 9E9 also blocks FcγRIII in vivo. Blood 2015; 126:2643–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y, Szalai AJ, Zhou T, Zinn KR, Chaudhuri TR, Li X, et al. FcγRs modulate cytotoxicity of anti-Fas antibodies: implications for agonistic antibody-based therapeutics. J Immunol 2003;171:562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim SH, Vaughan AT, Ashton-Key M, Williams EL, Dixon SV, Chan HT, et al. Fcγ receptor IIb on target B cells promotes rituximab internalization and reduces clinical efficacy. Blood 2011;118:2530–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beers SA, Glennie MJ, White AL. Influence of immunoglobulin isotype on therapeutic antibody function. Blood 2016;127:1097–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goroff DK, Finkelman FD. Activation of B cells in vivo by a Fab/Fc fragment of a monoclonal anti-IgD antibody requires an interaction between the antibody fragment and a cellular IgG Fc receptor. J Immunol 1988;140:2919–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ono M, Bolland S, Tempst P, Ravetch JV. Role of the inositol phosphatase SHIP in negative regulation of the immune system by the receptor FcγRIIB. Nature 1996; 383:263–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolland S, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory pathways triggered by ITIM-containing receptors. Adv Immunol 1999;72:149–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vidarsson G, Dekkers G, Rispens T. IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions. Front Immunol 2014;5:520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]