Abstract

In silico screening of drug target interactions is a key part of the drug discovery process. Changes in the drug scaffold via contraction or expansion of rings, the breaking of rings and the introduction of cyclic structures from acyclic structures are commonly applied by medicinal chemists to improve binding affinity and enhance favorable properties of candidate compounds. These processes, commonly referred to as scaffold hopping, are challenging to model computationally. Although relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculations have shown success in predicting binding affinity changes caused by perturbing R-groups attached to a common scaffold, applications of RBFE calculations to modeling scaffold hopping are relatively limited. Scaffold hopping inevitably involves breaking and forming bond interactions of quadratic functional forms, which is highly challenging. A novel method for handling ring opening/closure/contraction/expansion and linker contraction/expansion is presented here. To the best of our knowledge, RBFE calculations on linker contraction/expansion have not been previously reported. The method uses auxiliary restraints to hold the atoms at the ends of a bond in place during the breaking and forming of the bonds. The broad applicability of the method was demonstrated by examining perturbations involving small molecule macrocycles and mutations of proline in proteins. High accuracy was obtained using the method for most of the perturbations studied. The rigor of the method was isolated from the force field by validating the method using relative and absolute hydration free energy calculations compared to standard simulation results. Unlike other methods that rely on λ-dependent functional forms for bond interactions, the method presented here can be employed using modern MD software without modification of codes or force field functions.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

During the process of drug discovery and lead optimization, changes in the scaffold of a candidate compound are frequently performed by medicinal chemists in order to enhance the binding affinity and improve the drug like properties. These include ring opening and closure, as well as changes in ring and linker length. These changes are commonly referred to as scaffold-hopping. In addition to the improvement of pharmaceutical properties, scaffold hopping is used to expand patentable space1. Scaffold hopping is not limited to small molecules and can also be found in the building blocks of biomolecules; mutations involving proline are a notable and important example. The ring topology of the proline sidechain significantly restricts the backbone conformations of proteins and eliminates a backbone hydrogen bond donor, effects that make proline a disruptor of both α-helices and β-sheets. This makes proline substitutions a popular probe for studying the kinetics and thermodynamics of protein folding, binding and aggregation2–7. Mutations involving proline are also widely employed during protein design for shaping proteins into desired geometries and for modulating the thermodynamic/kinetic properties of the designed proteins8–10.

In silico methods of varied accuracy and efficiency have been developed to aid the screening of molecules and reduce efforts in wet labs11–15. These are now a key part of the drug development process. These methods include both data-based machine learning or artificial intelligence models, and rule-based physical models. Among these, alchemical free energy calculations are believed to be capable of delivering highly accurate predictions of binding affinity16–17. One popular variant of the alchemical free energy method is the relative binding free energy (RBFE) calculation used for comparing the binding affinities between a pair of candidate compounds sharing some common chemical groups. This method can minimize the thermodynamic noise by limiting the perturbations to small portions of the two compounds18–19. In the past few years, RBFE calculations have shown high accuracy in benchmarking and validation studies18, 20–23. Moreover, more and more examples have been reported in which RBFE calculations have made a positive impact on real drug-discovery projects in an industry setting24–26. Broadening the impact of RBFE calculations by improving their range of applicability is highly desirable. In particular, improved methodologies for handling scaffold hopping are desired.

RBFE calculations compute the free energy changes using alchemical Hamiltonians, in which the change between initial and final compounds is described as a function of a variable λ; λ=0 corresponds to the initial compound and λ =1.0 corresponds to the final compound. Conformational sampling at steps along λ is performed using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations; in principle, RBFE calculations can better evaluate two compounds with different degrees of flexibility in their scaffolds compared to other fast methods that rely solely on static structures. However, RBFE calculations that involve breaking and forming of covalent bonds were considered to be challenging, thus the application of RBFE calculations has been limited to so-called R-group perturbations and heterocycle replacements, in which the forming and breaking of covalent bonds are not conducted. The problem arises from the quadratic form of the bond interactions in molecular mechanics (MM), whose energy increases drastically as the bond distance moves away from the equilibrium. Thus, if a bond breaking process takes place from λ=0 (bond present) to λ=1 (bond absent), the sampled conformations at λ=1 may have extremely high potential energy under Hamiltonians at other values of λ. This can cause slow convergence when estimating free energy changes using thermodynamic integration or the Bennet acceptance ratio, as well as rounding errors in computation. To overcome this issue, Wang et al. developed a λ-dependent bond interaction functional form, which is referred to as the soft-bond potential27. The method inherits the philosophy of the softcore potential for nonbonded interactions28 and efficiently avoids high energy at extreme bond distances. The λ-dependent bond interaction approach has shown successes in perturbations involving ring opening/closure, ring contraction/expansion and macrocyclization of linear compounds27, 29. However, implementation of this method in MD simulation packages requires modification of the code handling the bond interactions, which is beyond the experience of many RBFE users and limits potential applicability. To our knowledge, OpenMM is the only freely availably software which allows the use of soft-bond like functional forms for bond interactions30

The other method frequently employed for calculating ring opening/closure transformation is the dual-topology approach, in which selected atoms in the ring structures are placed in the non-mixed regions. However, theoretical derivations have shown that conformational biases will be introduced when the non-mixed regions are doubly connected to the mixed regions31–34. Such conformational biases may have subtle effects on ring opening/closure transformations of rigid bicyclic compounds but have shown severe effects on ring opening of tricyclic ring structures31.

This paper describes a novel method that utilizes auxiliary restraints to enable the breaking and forming of covalent bonds in RBFE calculations. The main purpose of the auxiliary restraints is to temporarily keep the atoms at the ends of the modified bond near their equilibrium distance during the breaking and forming of the covalent bonds. This method can be employed using modern MD software without modification of codes because the auxiliary restraints use the most basic functional forms in molecular mechanics. For most of the perturbation pairs studied here, our method combined with the GAFF2 force field35 achieved equivalent accuracy and reliability compared to the soft-bond method27, 29 with OPLS3 force field36. The equivalence of the applicability of the new method and the soft-bond method is demonstrated by conducting multiple transformations involving ring opening/closure, ring and chain contraction/expansion for small molecules as well as transformation involving macrocycles and non-proline to proline mutations in proteins. The rigorousness of the method was then validated using relative and absolute hydration free energy (HFE) calculations on core fragment analogs.

Methods

In this section, the details for ring opening and closure, ring or linker contraction and expansion are described first, followed by a description of the system setup and detailed simulation methods.

Notation used to identify compounds used as test cases.

A number of examples have been taken from the literature to provide tests for the new method. We utilized the same numbering employed in the original publications which described these compounds for clarity. In some cases, the same number has been used in different publications for different compounds. In these cases, a Roman numeral is appended to the numerical identifier.

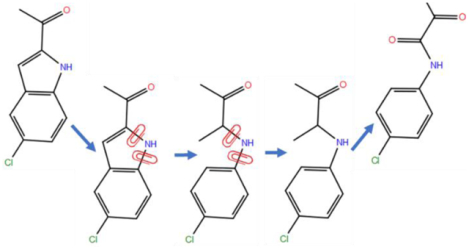

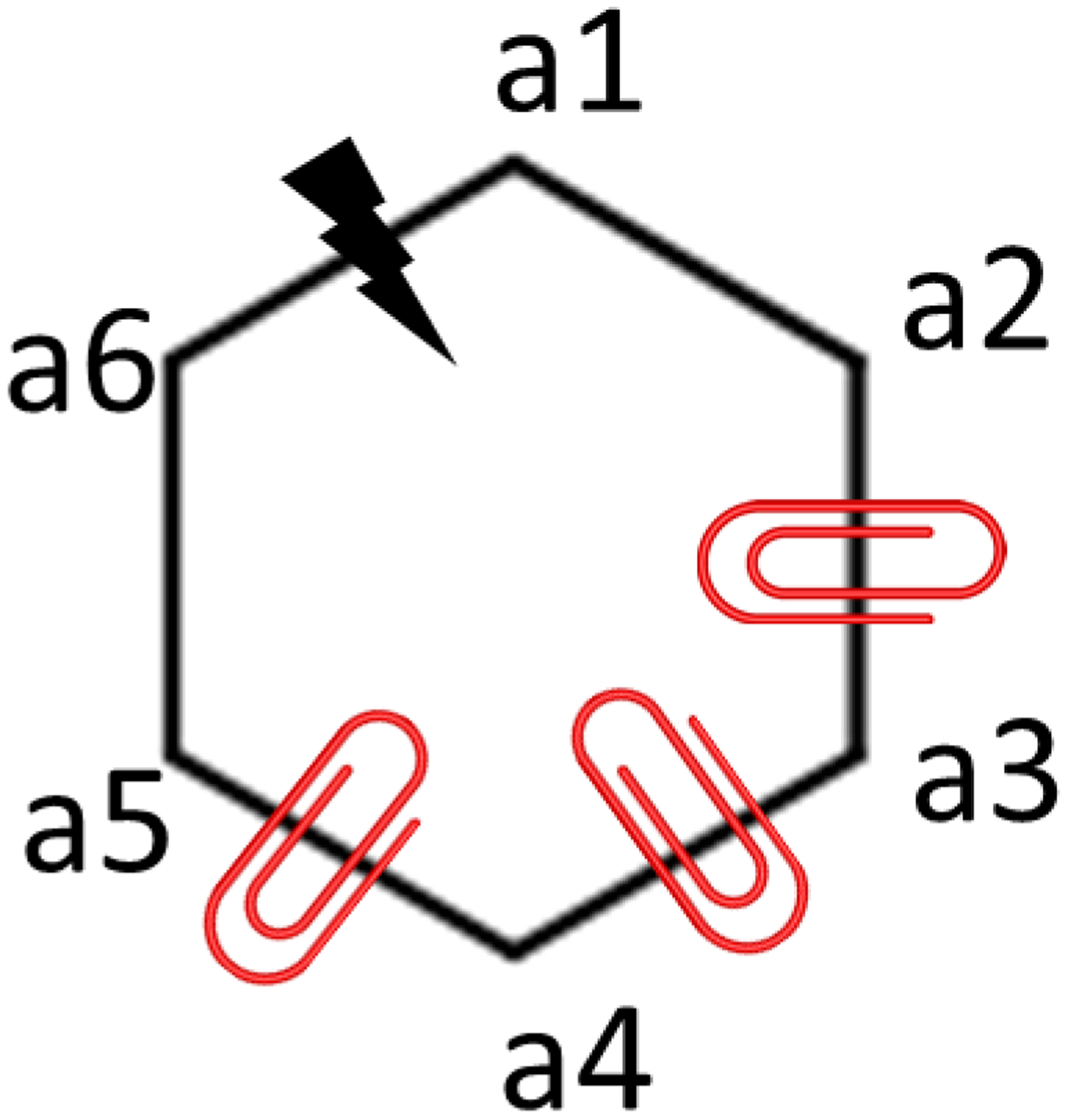

Ring opening/closure

For a ring opening scenario, after identifying the ring topology in ligand L0 that is absent in ligand L1, a bond in L0 is selected such that removal of the bond will result in a bonding topology most similar to the bonding topology of L1. The next step is to apply dihedral restraints on the atoms of the ring that will be opened. For an N-member ring, N-3 auxiliary dihedral restraints are applied on the ring atoms. For example, in order to break the bond between atoms a1 and a6 in a 6-membered ring (Fig. 1), three dihedral restraints are applied on the ring atoms a1-a2-a3-a4, a2-a3-a4-a5 and a3-a4-a5-a6. The strength of the dihedral restraints was chosen to be 10 kcal/mol and the reference angle of each dihedral restraint was obtained from the corresponding values in the equilibrated structure of L0. The strength of the dihedral restraints were based on initial guesses and seem adequate for the pairs calculated in this study. With these dihedral restraints, the selected bond can be broken as the auxiliary restraints keep the distance between atom a1 and a6 near the reference distance of bond a1-a6. The dihedral restraints are released after the selected bond is fully broken. Applying the ring opening process in reverse order results in a ring closure process. During ring closure transformations, the dihedrals may need to be rotated under the auxiliary restraints so the atoms at the ends of the forming bonds adopt values near those with the bond present. Once the ring opening or ring closure process has been finished, additional chemical differences between L0 and L1 may still remain. Traditional R-group RBFE calculations can then be applied to fully transform L0 into L1. The thermodynamic cycle in Fig. 2 illustrates the steps required to obtain the total free energy change of a ring opening transformation.

Figure 1. An illustration of the process of ring breaking.

A 6-membered ring with a lightning bolt indicating the bond to be broken and red clips indicating the dihedrals to be restrained is shown.

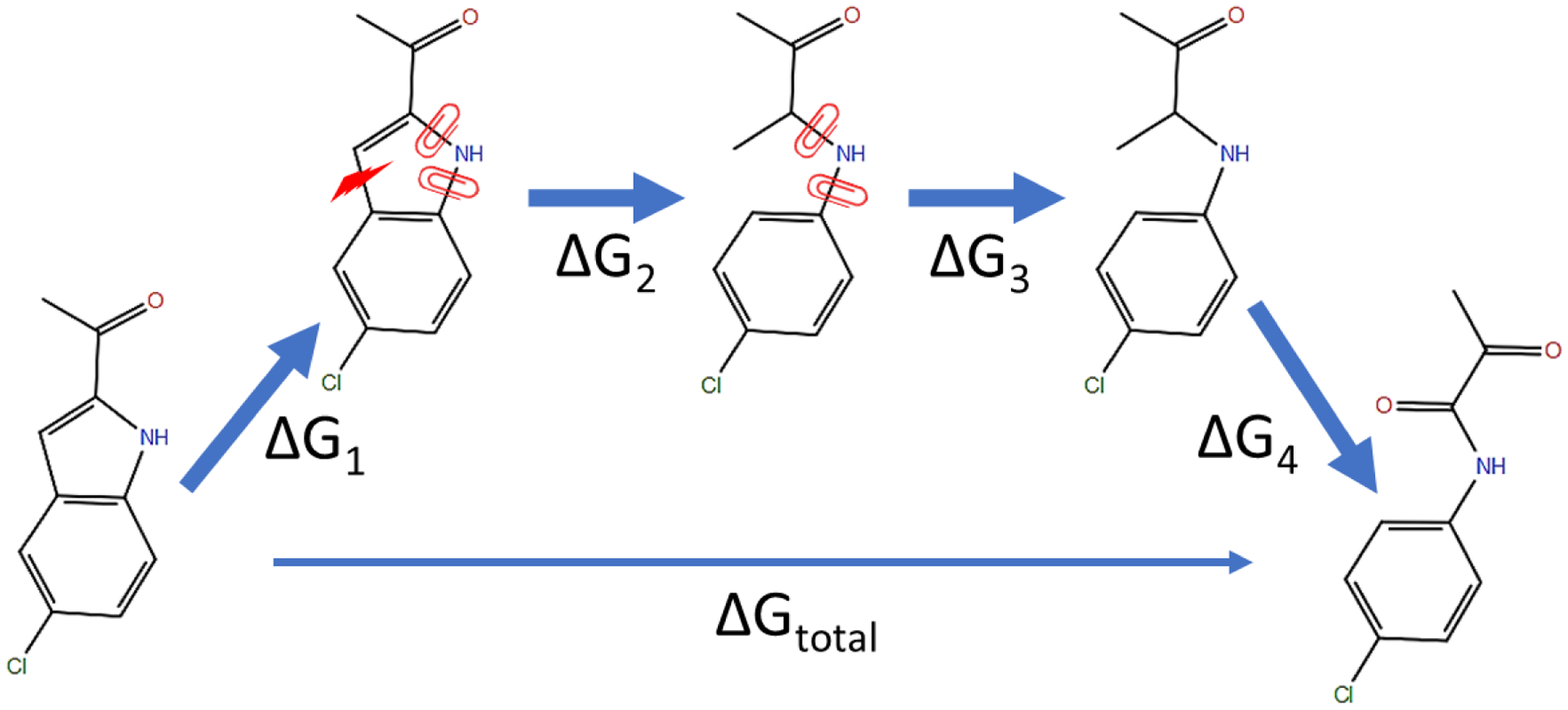

Figure 2. A thermodynamic cycle for a sample ring opening transformation.

ΔG1, ΔG2, ΔG3 and ΔG4 are the free energy changes of applying the auxiliary restraints, breaking the covalent bond, releasing the auxiliary restraints and completing any remaining chemical differences, respectively. ΔGtotal = ΔG1 + ΔG2 + ΔG3 + ΔG4.

To make the calculation more efficient, breaking of bonds (ΔG1) and restraining of dihedrals (ΔG2) can occur simultaneously as λ goes from 0 to 1 in the 1st stage of perturbations. The interaction of the selected bond is gradually scaled off and the auxiliary dihedral restraints are gradually turned on along the λ values. In the 2nd stage, the removal of auxiliary dihedral restraints (ΔG3) gradually occurs along the λ values. Perturbations of non-bonded interactions (ΔG4) can be conducted either in the 1st stage or the 2nd stage or be distributed in both stages. Ring closure transformation can also be completed using two stages of perturbation in a reversed order.

During the 1st stage of ring opening transformation, breaking of bonds includes changes of 1–4 interaction lists and the exclusion list for vdW/electrostatic interactions. Appearing and disappearing of 1–4 interactions and vdW/electrostatic interactions due to breaking of bonds gradually occurs along the λ values. For software like Amber, the associated free energy changes will be accounted as contribution from the 1–4, vdW and electrostatic interactions as we demonstrated in the examples given in the supporting information (SI).

The free energy changes arising from the removal/addition of bonded interactions, changes to the 1–4 interactions and exclusion lists, and perturbations of non-bonded interactions are all accounted. No interaction term was neglected when calculating the total free energy change (ΔGtotal).

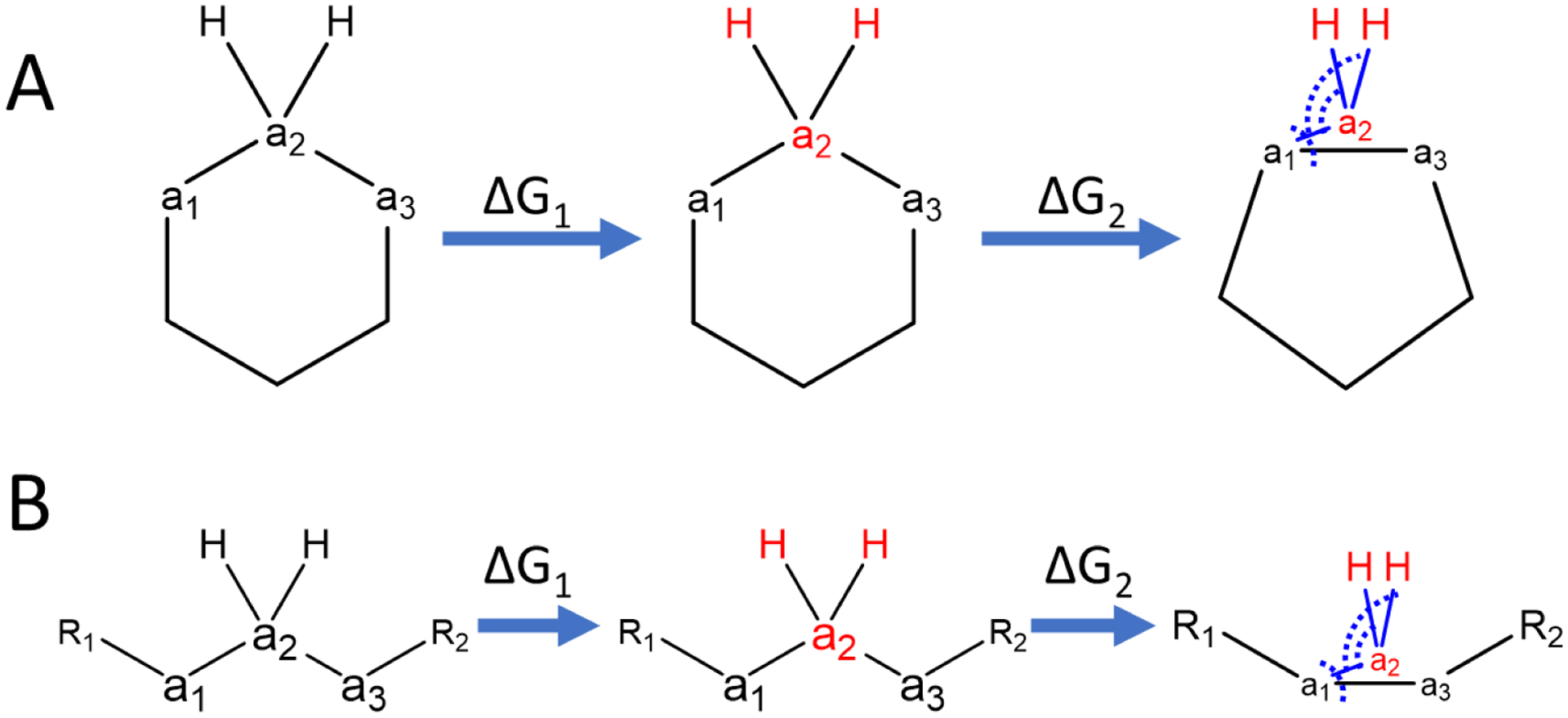

Ring and linker contraction/expansion

Ring contraction/expansion and linker contraction/expansion are treated similarly as they both involve the removal of atoms flanked by other atoms. Fig. 3 shows an example for the contraction of a ring and a linker, in which the transformation from ligand L0 to L1 requires changing a topology of -a1-a2-a3- into a topology of -a1-a3-. This transformation requires the removal of atom a2 between atom a1 and a3 and the formation of bonded interactions between atom a1 and a3. The non-bonded interactions involving atom a2 and the hydrogen atoms attached to atom a2 are turned off first (ΔG1). In the next step (ΔG2), all bonded interactions involving atom a2 are removed and the bonded interactions involving both atom a1 and a3 are turned on. Simultaneously, all bond and angle restraints involving atom a2 and the hydrogen atoms attached to atom a2 are turned on and the associated free energy change calculated. No dihedral restraints are needed in this case. Removal/addition of bonded interactions, applying restraints, appearing/disappearing of 1–4 and non-bonded interactions due to forming/breaking of bonds all occur gradually along λ values. No interaction terms were neglected when calculating the total free energy change.

Figure 3. Illustration of the concept of A) ring and B) linker contraction transformations using auxiliary restraints.

ΔG1 represents the free energy change of removing the non-bonded interaction of atoms a2 and H. ΔG2 represents the free energy change of applying the restraints listed in Table 1. Atoms shown in red are dummy atoms with no nonbonded interactions. The blue lines indicate the auxiliary bond restraints applied on a1-a2 and H-a2. The dashed arcs indicate the auxiliary angle restraints applied on a1-a2-a3 and H-a2-a1.

The participants, strength and reference distances/angles for the bond and angle restraints are listed in Table 1, which are the same for ring contraction and linker contraction. The strengths of restraints were our first guesses that seem adequate for pairs calculated in this study. None of the restraints in Table 1 need to be turned off after the contraction as the restraints can be considered equivalent to the bonded interactions connecting dummy atoms in the end states of regular R-group RBFE calculations. These steps complete the contraction process and give a final state of the contracted ring or linker as illustrated on the right side of Fig. 3. Ring or linker expansion can be accomplished by applying the previous steps in reverse order.

Table 1.

The participants, strength and reference distances/angles for the bond and angle restraints used for ring and linker contraction transformations.

| Bond/Angle | k | r0/θ0 |

|---|---|---|

| a1– a2 | 100 kcal/mol/Å2 | half of the reference distance of bond a1–a3 in L1 |

| H-a2 | Same as the k of the native H-a2 bond | Same as the r0 of the native H-a2 bond |

| a1 – a2 – a3 | 100 kcal /mol/rad2 | π rad (180°) |

| H- a2 – a1 | 50 kcal/mol/rad2 | π/2 rad (90°) |

Protein and ligand setup for test cases

Small molecules were parameterized using GAFF235. Partial charges were assigned using the AM1-BCC method37. The TIP3P water model38 was used to solvate the molecules. The ff14SB force field39 was used to parameterize the protein. For compounds listed in Table 2 & 3, the ligand poses were adopted from the published soft-bond method27. For compounds listed in Table 4, the ligand poses were manually constructed using the X-ray structures listed in Table S1 as templates. The manually constructed ligands poses were briefly energy minimized by using RDKit40 (v 2020.09.1) before parameterization. If present, ions were removed from the experimental structures. Missing hydrogens of the protein were added using MolProbity41. The rotamer states of Asn/Gln/His were adjusted by following the suggestions of MolProbity. The protein/ligand complexes and free ligands were solvated in truncated octahedron water boxes with initial buffer sizes of 8 and 15 Å respectively. Systems were neutralized with minimal numbers of Na+ or Cl− ions.

Table 2.

Comparison of the ΔΔG values for the ring opening/closure transformations calculated using the auxiliary restraints method, calculated using the soft-bond method, and measured by experiments. Units are kcal/mol. “Edo” signifies the compound edoxaban.

| Pairs | Auxiliary restraints/GAFF2 | Soft-bond/OPLS327* | Experimental58–59, 61, 63 | Auxiliary restraints/XFF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHK1 21→19 | −0.23±0.27 | 0.03 | 0.59 | |

| CHK1 21→17 | −1.10±0.32 | 0.22 | −0.57 | |

| CHK1 1→19 | 0.35±0.53 | 0.95 | 1.15 | |

| CHK1 20→17 | −0.59±0.16 | −0.03 | −0.51 | |

| CHK1 1-i→17 | −0.39±0.12 | 0.70 | −0.02 | |

| FacX edo→4d | 0.88±0.06 | 1.69 | 0.87 | |

| FacX edo→4c | 0.93±0.46 | 1.48 | 0.8 | |

| TPSB2 2→1-ii | −2.39±0.21 | −0.16 | −0.62 | −0.28±0.07 |

| BACE-1 7→6 | −1.48±0.35 | −0.67 | −0.12 | |

| BACE-1 7→31 | −1.90±0.53 | −1.24 | −0.64 | |

| MUE/R2/p-value | 0.71±0.08/0.75±0.07/p<0.01 | 0.54/0.62/p<0.01 |

the reported ΔΔG with cycle closure corrections were shown. The reported uncertainties for the soft-bond/OPLS3 method are not shown, as those reported uncertainties were calculated as BAR errors and cycle closure errors rather than independent runs as calculated for our data.

Table 3.

Comparison of the ΔΔG values for the ring and linker contraction/expansion transformations calculated using the auxiliary restraints method, calculated using the soft-bond method and measured by experiments. (Units: kcal/mol)

| Pairs | Auxiliary restraints/GAFF2 | Soft-bond/OPLS327* | Experimental69, 71–72 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHK1 21→20 | −0.04±0.15 | −0.19 | −0.07 |

| ERα 3b→2d | −1.34±0.40 | −1.45 | −1.78 |

| ERα 3b→2e | −2.88±0.54 | −2.80 | −2.44 |

| CatS 35→132 | 0.30±0.08 | 0.26 | |

| MUE/R2/p-value | 0.24±0.13/0.94±0.05/0.03 | 0.27/0.92/0.17 |

The reported ΔΔG with cycle closure corrections are shown. The reported uncertainties for the soft-bond/OPLS3 method are not shown here as the uncertainties, as those reported uncertainties were calculated as BAR errors and cycle closure errors rather than independent runs as calculated for our data.

Table 4.

Comparison of the ΔΔG values for macrocycles, calculated using the auxiliary restraints method, calculated using the soft-bond method and measured by experiments. (Units: kcal/mol)

| Pairs | Auxiliary restraints/GAFF2 | Soft-bond/OPLS329* | Experimental73–79 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrocyclization | |||

| 1→2 | 3.08±0.23 | 2.83 | 2.68 |

| 3→4 | −3.11±1.03 | −2.13 | −2.09 |

| 5→7 | −4.44±0.18 | −6.55 | −5.12 |

| 6→7 | −5.69±1.52 | −4.22 | −4.14 |

| 19→22 | −0.94±0.64 | −0.64 | 0.61 |

| 19→23 | −0.66±0.54 | −0.43 | 0.25 |

| 33→30 | −5.21±1.43 | −6.04 | −5.7 |

| 33→31 | −5.46±0.76 | −4.17 | −5.89 |

| MUE/R2/p-value | 0.88±0.23/0.91±0.06/p<10−3 | 0.71/0.91/p<10−3 | |

| Addition of sub-ring | |||

| 16→13 | −1.16±0.28 | −0.81 | 0.87 |

| 16→15 | −0.50±0.74 | 0.17 | 0.83 |

| 27→30 | −0.06±0.36 | −2.4 | 0.54 |

| 29→32 | 2.31±0.47 | −0.51 | 1.91 |

| MUE/R2/p-value | 1.09±0.20/0.74±0.10/p<1 | 1.93/0.19/p<1 | |

| Contraction of ring size | |||

| 10→9 | 0.15±0.22 | 0.11 | −0.09 |

| 11→10 | 0.09±0.37 | −0.11 | −0.82 |

| 11→9 | −1.47±0.51 | −0.01 | −0.91 |

| 13→12 | 3.06±0.41 | 3.66 | 2.65 |

| 14→12 | 3.40±0.67 | 3.75 | 2.22 |

| 14→13 | 0.22±0.73 | 0.1 | −0.43 |

| 22→20 | 1.39±1.06 | 1.02 | 0.39 |

| 22→21 | −0.03±0.80 | −1.72 | −1.08 |

| 22→23 | 0.64±0.28 | 0.2 | −0.36 |

| 25→24 | −0.34±0.76 | 0.08 | 0.65 |

| 26→24 | 0.26±0.85 | −0.28 | 0.21 |

| 26→25 | −0.67±0.30 | −0.35 | −0.44 |

| 26→27 | −1.70±0.97 | −2.29 | −2.49 |

| 28→27 | 0.71±0.77 | −1.54 | −1.04 |

| 29→28 | −0.45±0.46 | −0.43 | 0.11 |

| 31→30 | −0.90±0.41 | 1.87 | 0.19 |

| 32→31 | −0.49±0.59 | 1.78 | 0.19 |

| 8→9 | −1.65±0.91 | −1.31 | −0.3 |

| MUE/R2/p-value | 0.81±0.12/0.58±0.10/p<10−3 | 0.74/0.78/p<10−5 | |

| Overall MUE/R2/p-value | 0.86±0.10/0.82±0.04/p<10−11 | 0.89/0.78/p<10−9 | |

Data were taken from the 5ns simulations with cycle closure corrections. The reported uncertainties for the soft-bond/OPLS3 method are not shown, as those reported uncertainties were calculated as BAR errors and cycle closure errors rather than independent runs as calculated for our data.

We opted to use the publicly available GAFF2 force field35 with AM1-BCC charges37, 42 to parameterize the small molecule compounds. This will allow our method to be compared with other scaffold hopping methods under the same force field in the future. The force field parameters in Amber format can be found in SI. However, the method is not restricted to the use of this force field. Our in-house force field, XFF, was employed to recalculate transformations that showed large errors using the GAFF2 force field.

Full coordinate sets in PDB and SDF format for all the protein receptors and ligands studied here in their bound conformations are provided in the SI (Table S1). The 2-D structures of all studied molecules can be found in Fig. S1.

General simulation details

All simulations, including the equilibration and production runs, used a Langevin integrator with a 2 fs timestep and a friction coefficient of 2 ps−1. Bonds to hydrogens were constrained via SHAKE43, except when the bond connects a real atom and a softcore atom. Smooth particle mesh Ewald electrostatics with an 8 Å direct space cutoff was used44. The same cutoff distance was used for the hard truncation of Lennard-Jones interactions, which has a long-range continuum correction on the dispersive term.

Equilibration

Initial structures of the complex and the free states of L0 and L1 were minimized using 100 steps of steepest descent plus 100 steps of conjugate gradient. During the minimization, Cartesian restraints were applied to all non-solvent heavy atoms with a strength of 10 kcal/(mol*Å2). The systems were sequentially heated at fixed volume from 100 K to 298 K with an increase of 20 K every 10 ps. Cartesian restraints with a strength of 4 kcal/(mol*Å2) were applied to all non-solvent heavy atoms. A 0.5 ns constant pressure simulation at 1 atm was carried out to equilibrate density and gradually release the Cartesian restraints by reducing the restraint force constant by 0.2 kcal/(mol*Å2) every 0.025 ns. The pressure was regulated using the Monte Carlo barostat45 with pressure coupling constant set to 0.2 ps−1.

Topology and coordinate for the RBFE calculations were constructed by appending the appearing atoms of the equilibrated L1 to the structures of equilibrated L0 using Z-matrix by tLEaP. The appended structure was used for all the λ windows. Under each λ window the appended structures were briefly minimized using 100 steps of steepest descent. The systems were then heated to 298K over 50 ps under constant volume. Cartesian restraints with a strength of 5 kcal/mol*Å−2 were applied to all non-solvent heavy atoms during the minimization and heating. After heating the systems, constant pressure simulations at 1 atm and 298K with a length of 40 ps were used to further equilibrate the volume without any Cartesian restraints. The pressure was regulated by the Monte Carlo barostat45 and the pressure coupling constant was set to be 0.2 ps−1.

RBFE calculations

The softcore vdW potential was applied to all atoms that disappear or appear during the free energy calculations46. The value of α in the softcore vdW potential, which is the softcore radius, was set to be 0.5 Å. The auxiliary restraints were applied when calculating the ΔG for the protein/ligand complexes as well as the ΔG for the free ligands.

Hamiltonian replica exchange (HRE) between adjacent λ windows was used here to facilitate the convergence of the calculations47, but is not required for use of the new method. The number and spacing of λ windows were set to satisfy an exchange success rate of >15% for any two adjacent λ windows. In our experience, 14 λ windows each are sufficient for the 1st stage and 2nd stage of ring opening transformations as well as the 2nd stage of ring/linker contraction transformations. For each λ window, the length of production runs was 5 ns and the number of exchange attempts was 4000. For each λ window at every exchange attempt, the potential energy of the coordinates under the Hamiltonian of the λ window were collected, as well as the potential energies of these coordinates under the Hamiltonian of all other λ windows. From the collected potential energies, the free energy change ΔG was computed by using multi-state Bennet acceptance ratio (MBAR)48–49. Three independent HRE simulations with different initial velocities were conducted to obtain the standard deviation of ΔΔGbinding. ∂U/∂λ for the bond/angle/dihedral terms were collected and thermodynamic integration was used to calculate the contribution from bond/angle/dihedral terms to the total ΔΔGbinding.

Hydration free energy calculations

The core fragment analogs were all parameterized using the GAFF2 force field35. For the relative hydration free energy calculations, the core fragment analogs were solvated in TIP3P water box with an initial buffer size of 20 Å to construct the systems representing the aqueous phase. No ions were added to the systems. Scaffold hopping transformations were performed in both the water and vacuum phase using the auxiliary restraints method. The same equilibration and HREMD protocols as the RBFE calculations were adopted to carry out the calculations.

For the absolute hydration free energy calculations, the core fragment analogs were transferred from the water phase to the vacuum phase in two stages. In the first stage, all the partial charges were turned off by linearly scaling the electrostatic interactions. The λ values were set to be 0.00, 0.20, 0.40, 0.60, 0.80 and 1.00. In the second stage, the vdW interactions of the core fragment analogs were disappeared using softcore potential with a softcore radius of 0.5 Å. The λ values were set to be 0.0, 0.0479, 0.1151, 0.2063, 0.3161, 0.4374, 0.5626, 0.6839, 0.7937, 0.8849, 0.9521 and 1.0.

For both the relative and absolute hydration free energy calculations, three independent HRE simulations with different initial velocities were conducted.

Uncertainty estimation

For the uncertainties estimated for MUE, R2 and Kendall’s τ, the ΔΔG values obtained from the three independent runs were randomly shuffled to form 10,000 sets of data for all of the perturbation pairs. The MUE, R2 and Kendall’s τ were then computed for each set of data. The uncertainties were reported as the standard deviation of the statistical metrics for the 10,000 sets of data.

Software packages and example setup

The method was integrated into the XFEP platform50 to carry out the free energy calculations presented in the main text. Use of other simulation packages should be straightforward, since customized bond interaction functional forms are not required. The auxiliary restraints can be applied as modified dihedral parameters. To illustrate this, a ring opening (CHK1 20→17), a ring contraction (ERα 3b→2d) and a chain contraction (CatS 35→132) FEP calculation were conducted using the standard Amber1851 force field as examples. The calculated ΔΔG values using the Amber18 force field for these three example transformations are presented in Table S2. The standard Amber18 force field reproduced the ΔΔG values calculated using the XFEP platform for all three example transformations. More details as well as the input and output files are provided in the SI, in order to enable the method to be evaluated using publicly available software packages.

Results

We validated our new scaffold hopping method by calculating the relative binding free energy changes resulting from transformations involving ring opening/closure as well as ring and linker expansion. The validation systems include well documented small-molecule compounds that have been studied in previous publications using the soft-bond potential27, 29. Additionally, a set of protein-protein interactions involving proline replacements were used to validate the application of the methodology to protein. In particular, the changes in binding free energy between the turkey ovomucoid third domain (OMTKY3) and its binding partners caused by non-proline to proline mutations were calculated using the new method. This is an excellent model system as high resolution structures of the free proteins and the bound state are available and careful thermodynamic measurements have been reported52–55. Firstly, we summarize the key features of the new method, then we describe the model systems and present results.

The main challenges and the theoretical background involved in the breaking and forming bonds in free energy calculations are well documented27. In short, the problem originates from the functional form of the bond interaction in MM, where the energy increases drastically as the bond distance deviates from the reference value. When a covalent bond is broken as λ goes from 0 to 1, the strength of the bond will gradually be turned off. At λ=1, with zero force constant, the two atoms in the bond can move far apart, which has extremely high bond energy under Hamiltonians (H) at other λ values with non-zero force constants. For thermodynamic integration, ∂H/∂λ values (equal to Hλ=1 - Hλ=0 with linear mixing of Hλ=1 and Hλ=0) are collected at each λ to compute the integration. Thus, ∂H/∂λ values can exceed the optimal numerical precision range and exhibit high fluctuations at λ=1. For MBAR calculations, this leads to poor phase space overlap as coordinates sampled at λ=1 have extreme energy at other λ values. The soft-bond method utilizes a λ-dependent functional form to prevent extreme values of the bond energy when evaluating coordinates from λ=1 using Hamiltonians at other λ values, including λ=0. This is similar to the softcore potential for turning on and off the van der Waals and electrostatic interactions during free energy calculations28.

In contrast to the soft-bond method, our method does not require modification of the functional form of bonded interactions. For ring opening transformations several dihedral restraints are applied on the ring topology to hold the two atoms at the ends of the bond in place and prevent the bond length deviating from the reference distance when breaking the bonded interaction. This prevents extreme values of bond energies that can arise evaluating coordinates sampled at λ=1 using Hamiltonians at λ=0 during the breaking of a bond interaction. After the bond interaction has been removed, the dihedral restraints are also removed and the associated free energy contribution is accumulated in the overall transformation. The dihedral interactions in MM have a cosine functional form (k*cos(n*θ-φ)), which is a periodic function with a maximal difference of 2k between the energy minima and maxima. Thus, the removal of the dihedral restraints in free energy calculations is a much milder transformation than the removal of bond interactions with a quadratic functional form. Ring closure transformations can be accomplished by reversing the steps of ring opening transformations.

Our method is conceptually similar to the attach-pull-release method used for calculating absolute binding free energies between receptors and ligands56. Both methods utilize angle and dihedral restraints to minimize the fluctuation of free energy changes during the more challenging parts of the transformation.

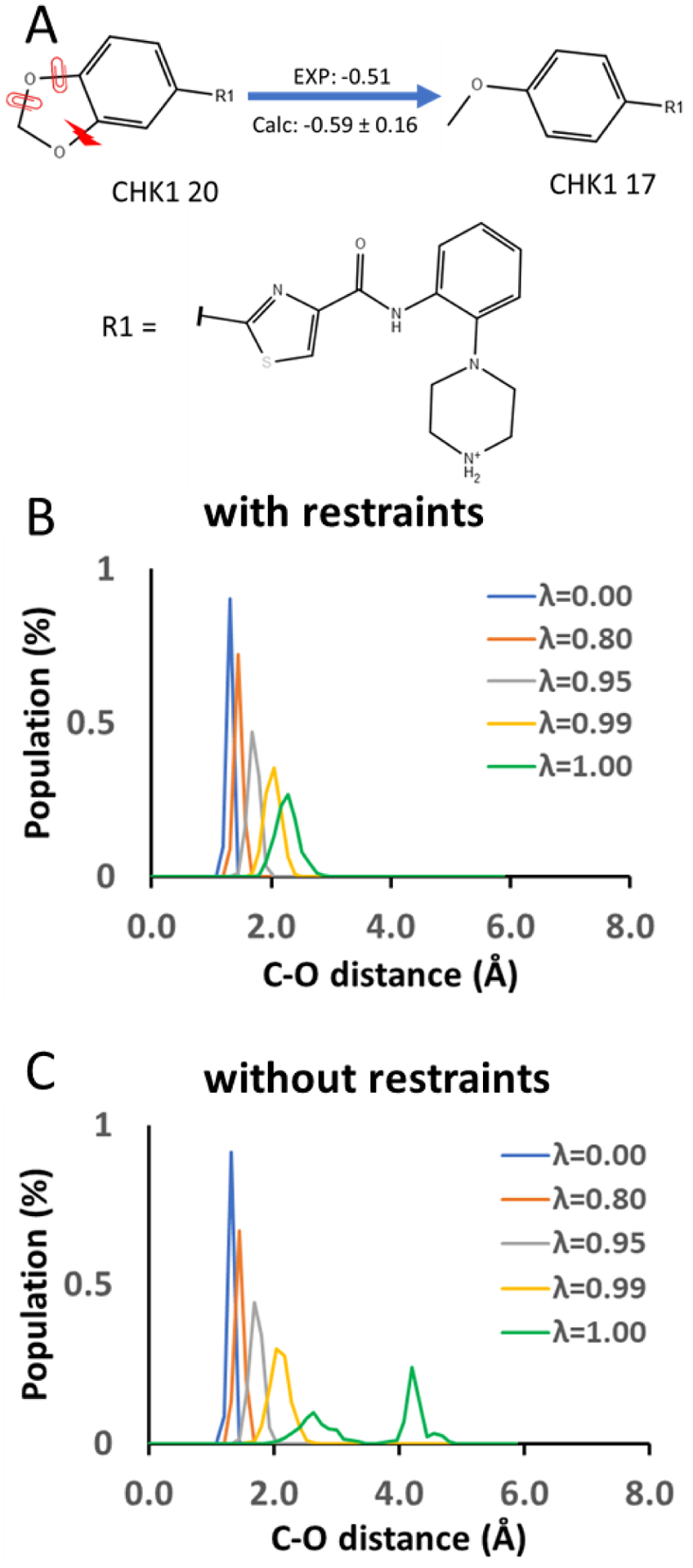

As an example of the application of auxiliary restraints to ring opening, we show the effect of the restraints on bond removal using the transformation of compound 20 to 17 (Fig. 4A). A bond connecting atoms C and O was selected to be broken in the ring opening transformation. The bond interaction between the C and O atoms is linearly scaled by λ. The bond interaction is intact when λ = 0.00 and is removed when λ = 1.00. We compared the distance distribution between the atoms C and O of 20 at λ=0.00, 0.80, 0.95, 0.99 and 1.00 with dihedral restraints of k = 10 kcal/mol (Fig. 4B) and without the dihedral restraints (Fig. 4C). The distance distribution overlaps are similar among λ=0.00, 0.80, 0.95, 0.99 with the dihedral restraints and without the dihedral restraints. However, under no dihedral restraints (Fig. 4C), a significantly poorer overlap between λ = 0.99 and 1.00 was obtained compared to the overlap obtained with the dihedral restraints (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

A) An example of the ring opening transformation between ligands 20 and 17 of Chk1. The red lightning bolt indicates the bond being broken during the ring opening transformation, and the red clips indicate the auxiliary dihedral restraints. B) Distance distribution between atoms C and O at the ends of the breaking bond under dihedral restraints of k= 10 kcal/mol at different λ values. C) Distance distribution between atoms C and O at the ends of the breaking bond under no dihedral restraint at different λ values. The bond interaction is scaled linearly by λ.

As the bond interaction between the atoms C and O is weakened when λ approaches 1.00, the distance between the two atoms gradually deviates from the reference distance even with dihedral restraints. This is because releasing the C–O bond allows the inner angles of the 1,3-dioxolane to return to their reference angles defined by the GAFF2 force field. We believe that it is not necessary to keep the distance between the atoms C and O centered at the reference distance under all λ values, as long as the distance distribution has sufficient overlap between adjacent λ windows when the bond interaction is gradually turned off. Restraining the C–O distance to center at the reference distance may require much stronger restraints. This could eventually cause the same problems of breaking bonds without auxiliary measures when calculating the free energy changes of releasing these restraints.

We tested our method on the perturbation pairs studied previously using the soft-bond method27. Indexing of the compounds was adopted from the citations associated with each protein target. Here, we provide a brief summary of these model systems and compounds used for the RBFE calculations.

Applications to ring opening/closure

Checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1) is a key participant in the S and G2/M checkpoints and is critical for the survival of cancer cells with p53 mutations57. A series of compounds, including compounds 17, 19, 20 and 21, were designed to improve the affinity to CHK1 and the selectivity against CDK2( cyclin-dependent kinase 2) of the initial hit compound (1-i)58.

Factor Xa (FacX), which converts prothrombin to thrombin in the coagulation cascade, is a target enzyme for treating thromboembolic disease. Edoxaban and the two other candidates proposed during drug development, 4c and 4d, all bind to the S1 and the S4 pockets of FacX59. Edoxaban exhibits both higher affinity to FacX and anticoagulant activity than 4c and 4d59–61.

β-tryptase (TPSB2) is reported to be strongly correlated with inflammatory and allergic disorders62. Although compound 2 has a lower affinity to TPSB2 compared to compound 1-ii, compound 2 has significantly less off-target binding, which was believed due to the higher rigidity of the tropanylamide scaffold of compound 2 than the piperidinylamide scaffold of compound 1-ii63.

Beta-secretase 1 (BACE-1) is a promising target for treating Alzheimer’s disease64. Knockout of BACE-1 completely abolishes the generation of amyloid β-peptides and reverses the cognitive decline in a mouse model65–66. Compound 7 is a BACE-1 inhibitor with a bridged ring scaffold which is intentionally designed to be more conformationally constrained than the lead compound 6 which has a bicyclic ring scaffold67. Compound 31 was designed to achieve a higher in vivo brain penetration.

RBFE calculations of these compounds can be accomplished by ring opening/closure transformations, which serve as good examples to validate our method. The RBFE values calculated for these systems, using the auxiliary restraints method with the GAFF2 force field, generally show good correlation with the experimentally measured ΔΔG values (Table 2). Contributions from the bonded terms are presented in Table S3. The mean unsigned error (MUE), R2 and p-value are 0.71±0.08 kcal/mol, 0.75±0.07 and <0.01 which are comparable to the results obtained using the soft-bond method with the OPLS3 force field.

Some transformation pairs resulted in larger errors. Significant deviations (>1 kcal/mol) between the ΔΔG values calculated using our method and measured by experiments were found for pairs TPSB2 2→1-ii, BACE-1 7→6 and BACE-1 7→31.

For BACE-1 7→6 and BACE-1 7→31, the sidechain rotamer state of Y120 depends on whether the core contains the bridged ring of ligand 7 or the bicyclic rings of ligand 6 and 31, which can be observed in PDB 4ZSQ and 4ZSP (Fig. S2). Besides the sidechain of Y120, the backbone traces of the β-sheets harboring Y120 do not align well between the bridged ring complex (PDB 4ZSQ) and the bicyclic ring complex (PDB 4ZSP). Thus, accurate modeling of the perturbations of BACE-1 7→6 and BACE-1 7→31 requires sufficient sampling of the protein conformational changes of Y120 and its neighboring residues. Even if a sufficient sampling of the conformational changes can be achieved using enhanced sampling methods, the accuracy of the calculated ΔΔG values for the perturbations will still depend on whether the protein force fields can accurately describe the energetics of the two conformations observed in 4ZSP and 4ZSQ. For these reasons, we suggest avoiding BACE-1 7→6 and BACE-1 7→31 in future benchmarking of scaffold hopping methods, as the complications prevent a fair evaluation of the scaffold hopping methods themselves.

For TPSB2 2→1-ii, the ΔΔG value was recalculated using ligands parameterized by the XFF force field instead of GAFF2 (Table 2). Using the XFF force field significantly decreases the error of the ΔΔG between TPSB2 2 and 1-ii, which indicates that the GAFF2 force field may be inadequate for modeling the binding free energy difference between TPSB2 2 and 1-ii. By visually examining the conformational ensemble of TPSB2 1-ii & 2 in the unbound state, we found that the conformations of TPSB2 1-ii & 2 given by the GAFF2 and XFF force fields mainly differ at the planarity of the thiophene-2-carboxamide. The GAFF2 force field prefers a more planar conformation of the thiophene-2-carboxamide, while the XFF force field prefers a more perpendicular conformation. The more perpendicular conformation given by the XFF force field is consistent with the conformation of 2 observed in the X-ray structure of 2 co-crystalized with TPSB263. TPSB2 2 may experience more internal steric clashes in the perpendicular conformation, which explains why TPSB2 2 is overly favored in the unbound state when using the GAFF2 force field. Note that the ΔΔG value for TPSB2 2→1-ii calculated using the GAFF2 force field was included when computing the MUE, R2 and p-value. XFF was used here to show that disagreement between calculated and experimental values can be a result of inadequate force field rather than a faulty method for handing scaffold hopping in free energy calculations.

We performed three independent control calculations on CHK1 20→17 using Amber18, in which the dihedral restraints were not applied during breaking of the bond. Two out of the three independent runs crashed at random simulation steps during HREMD due to numerical instability. The crashes always occur at λ = 1.0 during the 1st stage and can happen no matter whether the compound was bound or unbound. Details of the simulation setup for the control calculations can be found in the SI.

Expansion/contraction of ring and linker

Contraction of rings and linkers involves the removal of atom a2 and formation of a bond between atom a1 and a3 in a bond topology of -a1-a2-a3- (Figure 3). We believe that the choice of location to restrain the atom a2 after the contraction is critical for ring and linker contraction transformations in free energy calculations. To prevent extreme bond distances between a1 and a2 as well as between a2 and a3, a2 must be kept within the proximity of both a1 and a3 after the contraction. We chose to keep a2 at the exact center between a1 and a3 after the contraction. We believe that placing a2 at the center between a1 and a3 increases the symmetry of a2 and reduces the available conformational space of a2, which also may benefit the convergence of the free energy calculations involving chain and linker contractions. The expansion of rings and linkers can be accomplished by reversing the contraction transformations of rings and linkers.

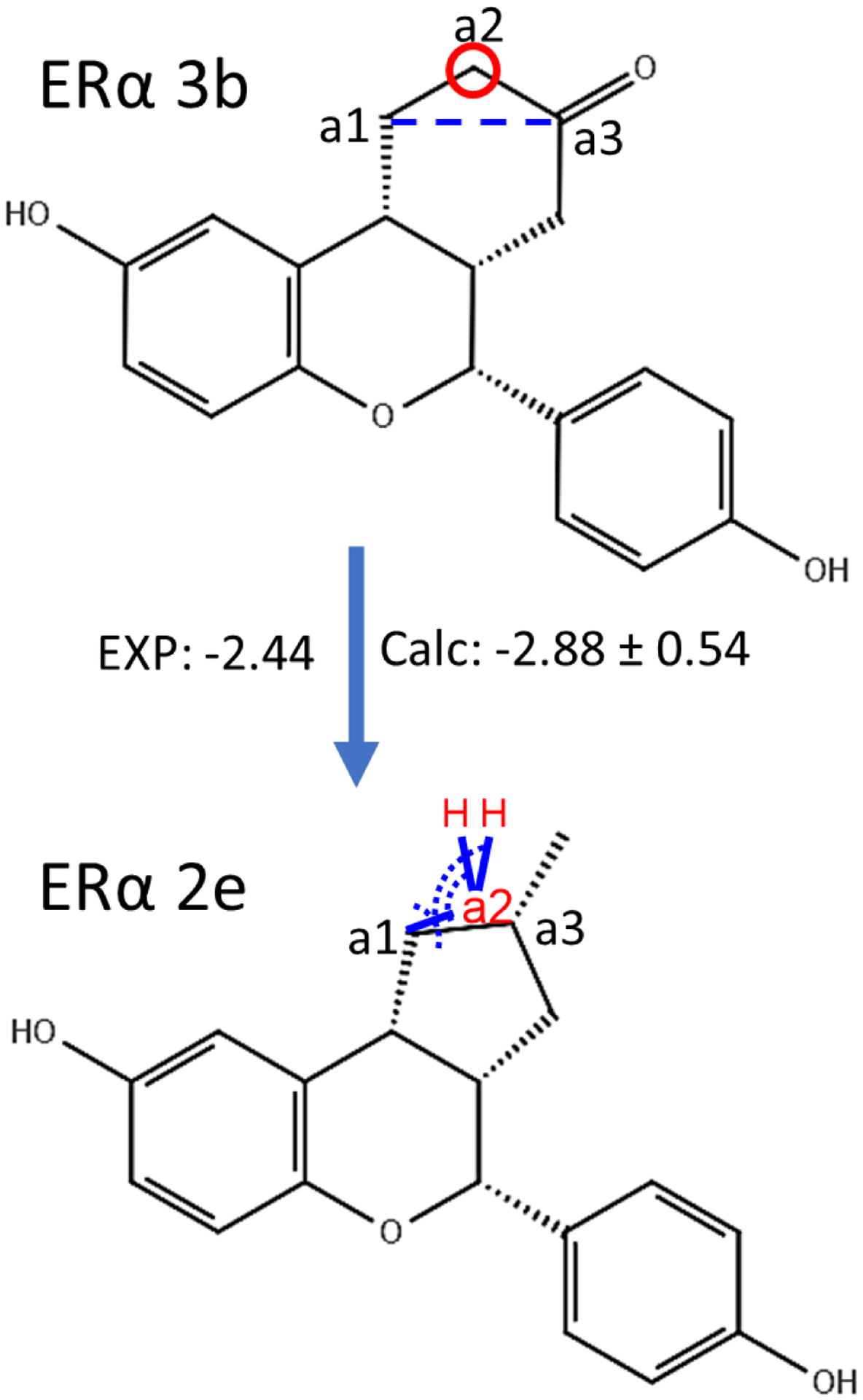

We tested our ring contraction/expansion method on perturbation pairs studied previously by using the soft-bond method27, involving the estrogen receptor subtype alpha (ERα). ERα is expressed in many cells and tissues with key roles in physiological function, which makes it a popular target for treating various diseases68. A series of compounds, including compounds 3b, 2e and 2d, were designed to improve the selectivity against ERβ of the lead compound SERBA-169. The strategy for a representative ring contraction using auxiliary restraints is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

An example illustrating the ring contraction transformation from Erα ligands 3b to 2d studied using the auxiliary restraints method. The atom to be removed from the ring (a2) is indicated by a red circle, and the bond to be formed (a1-a3) is indicated by a blue dashed line. The blue lines indicate the auxiliary bond restraints applied on a1-a2 and H-a2. The dashed arcs indicate the auxiliary angle restraints applied on a1-a2-a3 and H-a2-a1. Chirality is indicated using the wedge-dash notation. Further changes are required in addition to the ring contraction.

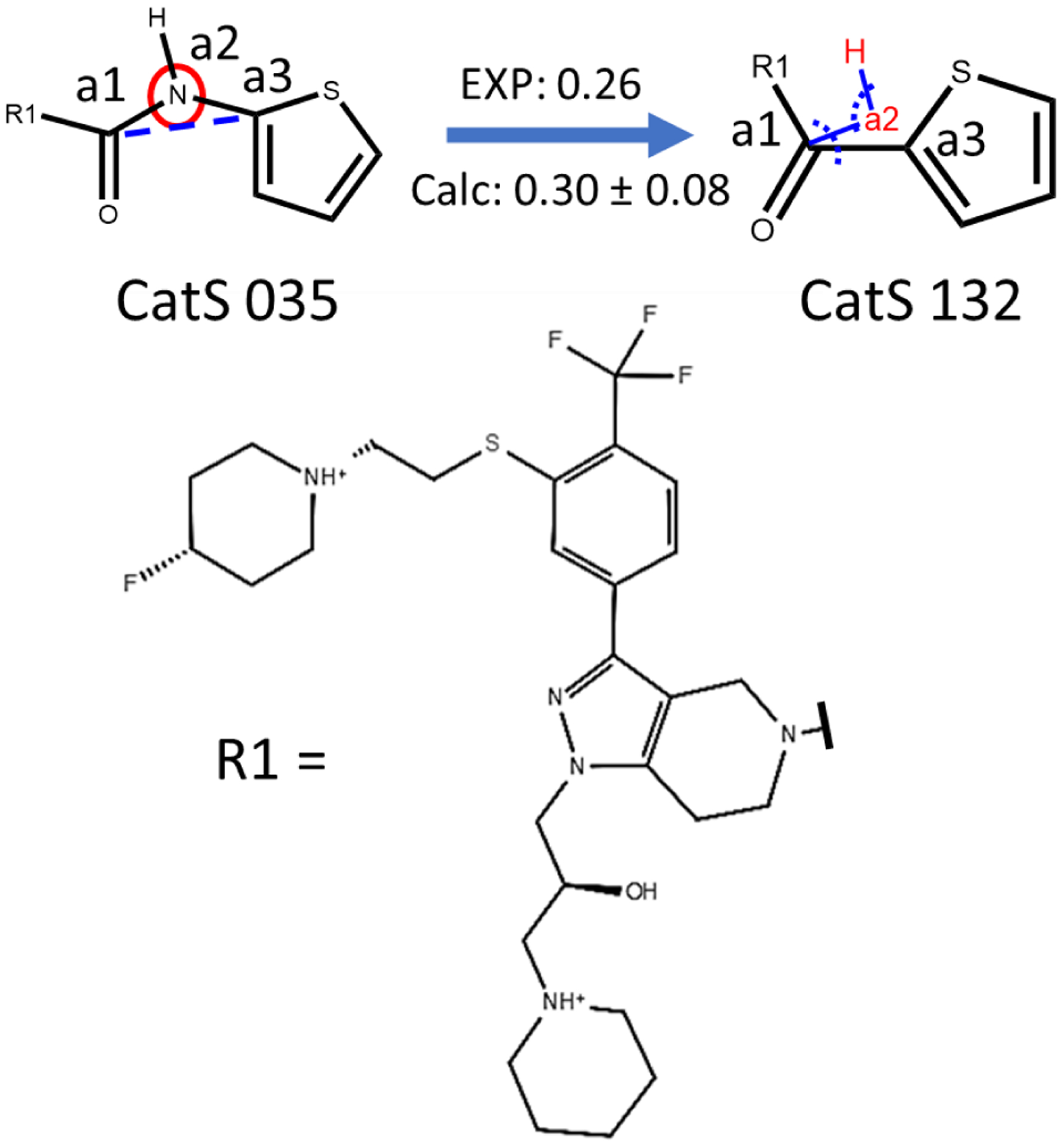

Cathepsin S (CatS) mediates the cleavage of major histocompatibility class II (MHC-II) associated invariant chain (Ii), which is crucial in the initiation of MHC-II related immune response to an antigen. Inhibition of CatS can treat various autoimmune disorders and inflammatory diseases70. A perturbation between a pair of Cathepsin S (CatS) ligands (compound 35 and 132) was also included here, which involve contraction of the linker between the core and the thiophene group (Fig. 6). To our knowledge, examples for handling expansion and contraction of linkers in free energy calculations have not been published previously.

Figure 6.

An example illustrating the linker contraction transformation from CatS ligands 35 to 132 studied using the auxiliary restraints method. Atom (a2) to be removed from the linker is indicated by the red circle and the bond (a1-a3) to be formed is indicated by the blue dashed line. The blue lines indicate the auxiliary bond restraints applied on a1-a2 and H-a2. The dashed arcs indicate the auxiliary angle restraints applied on a1-a2-a3 and H-a2-a1. Chirality is indicated using the wedge-dash notation. Units: kcal/mol.

Calculated and experimental RBFE values for the ring and linker contraction/expansion transformations are provided in Table 3. Contributions from the bonded terms are presented in Table S3. For all of these transformations, the auxiliary restraints method and the GAFF2 force field show unsigned errors under 0.5 kcal/mol, which is comparable to the soft-bond method with the OPLS3 force field.

Control calculations using Amber18 were also performed on ERα 3b→2d and CatS 35→132, in which the bond a2-a3 was broken and the bond a1-a3 was formed without restraining the positions of atoms a2 and H during the calculations of ΔG2 in Fig. 3. All three independent simulations failed during equilibration due to numerical instability. Details of the simulation setup for these control calculations can be found in the SI.

Macrocyclization, ring-size changing and rigidification of macrocycles.

Macrocyclization of drug compounds is frequently used to improve binding affinities of acyclic compounds and can be considered as a special case of scaffold hopping73–76. The binding affinity and drug likeness of macrocyclized compounds often can be further improved by rigidifying the cyclic scaffolds and changing the ring sizes of the macrocycles74–79. The ability to model these changes is an important part of any in silico method. Consequently, the performance of the auxiliary restraints method was also tested on transformations that involve macrocyclization of linear compounds, changing ring-size of macrocycles and rigidification of macrocycles by adding sub-rings onto the primary rings. All the transformations were accomplished using the method described above for ring opening/closure and expansion/contraction.

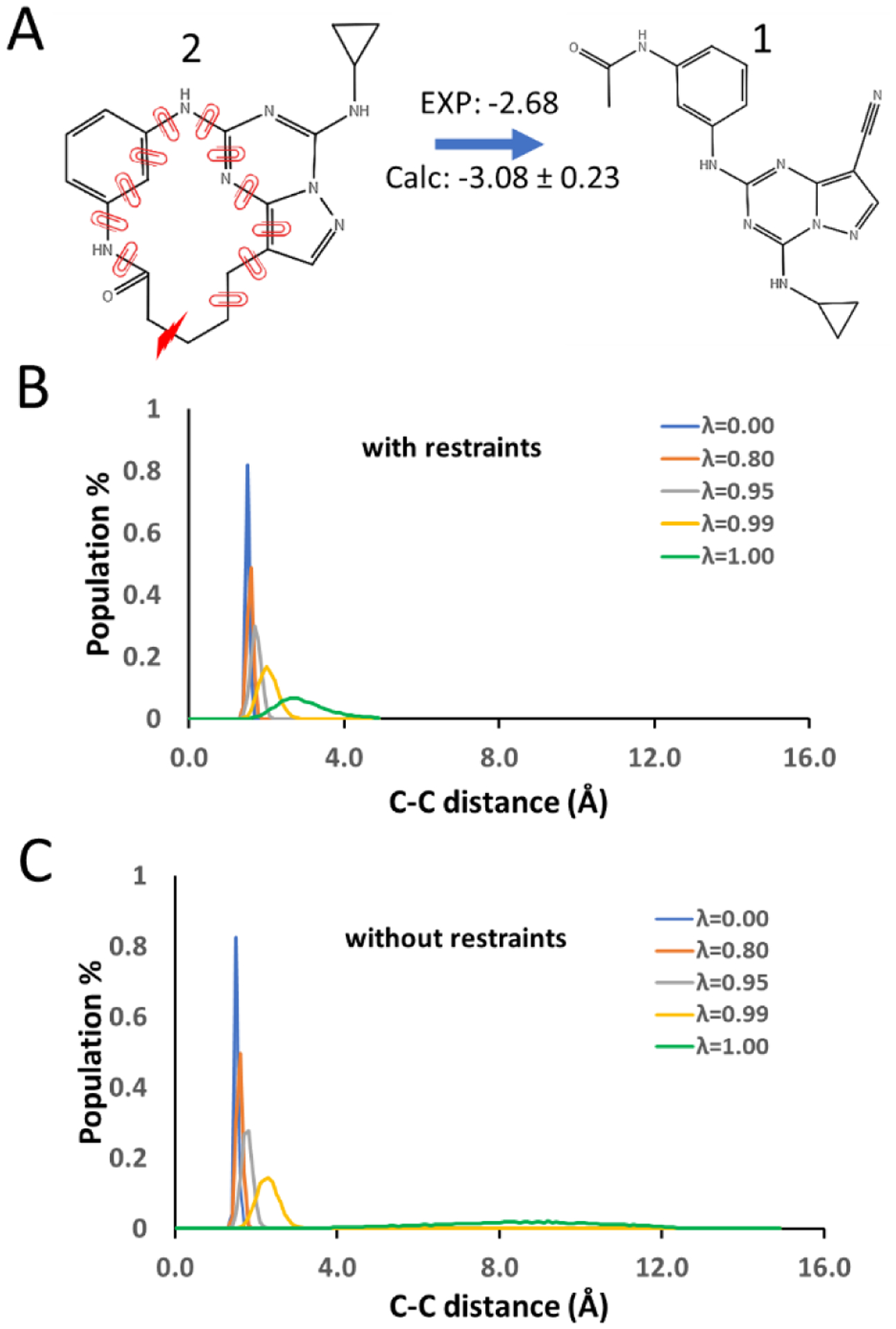

We chose several model systems which have been previously studied using the soft-bond method29. A brief description of the test compounds follows: The down-regulation of casein kinase 2 (CK2), a serine/threonine kinase, has been shown to decrease proliferation and increased apoptosis of cancer cells80. The macrocyclic compound 2 has a significantly lower binding affinity to CK2 compared to the acyclic compound 176, which is contradictory to expectation. However, compound 2 shows significantly enhanced cellular activity due to its higher membrane permeability. The macrocyclization of BACE-1 compound 3 results in compound 4, which shows a higher binding affinity79. Compound 19 binds to BACE-1 with a hairpin shape. A series of macrocycles were designed based on this structure, including compounds 20-23, by linking the two ends of compound 1978.

MTH1 is a member of the Nudix phosphohydrolase superfamily of enzymes, which hydrolyses oxidized purines and prevents their incorporation into DNA81. The macrocyclized compound 7 shows a significantly improved binding affinity to MTH1 compared to the two acyclic compounds 5 and 674. However, inhibition of MTH1 did not display any significant suppression of cancer cells74.

Compound 8 to 11 are macrocyclic CHK1 inhibitors which mainly differ at the ring size. Synthesis and study of compounds 8 to 11 were meant to find the optimal ring size of the macrocycles75.

Cancer cells can adapt to solo target inhibition by up-regulating alternative pathways. Inhibition of chaperon proteins, such as heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), disrupts the function of a wide range of client proteins, which can eliminate alternative pathways for cancer cell survival82. A series of macrocyclic compounds (12–18) were designed to improve the binding affinity to HSP90 of an initial lead compound with satisfactory pharmacokinetics77.

Compounds 24 to 32 are from another series of macrocyclic HSP90 inhibitors which have significantly improved binding affinity compared to the acyclic compound 3373.

Macrocycles require more dihedral auxiliary restraints during the removal of bond interactions. It is possible that the length of the bond may still be too long to be broken due to the accumulation of small fluctuations of restrained dihedrals far along the chain from the bond being removed. To test this, the distance distribution between C–C for CK2 1→2 was collected during the removal of the bond interaction under dihedral auxiliary restraints with k = 10 kcal/mol (Fig. 7A) at λ=0.00, 0.80, 0.95, 0.99 and 1.00. For the macrocyclic compound CK2 2, a wider distance distribution at λ = 1.00 (Fig. 7B) was obtained than the distance distribution (Fig. 4B) for CHK1 20, which has a small ring, under dihedral auxiliary restraints with the same strength. Similar to the bond distribution of C–O of CHK1 20 in Fig. 4A, the C–C bond distance also deviates from the reference distance under auxiliary restraints. However, the auxiliary restraints still provide sufficient overlap of the distance distribution between C–C of CK2 2 over the same set of λ values, especially between λ = 0.99 and 1.00. In contrast, there is almost no overlap between the distance distribution for λ =0.99 and 1.00, when no dihedral restraints are applied (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

A) The ring opening transformation between macrocycles CK2 2 and 1. The red lightning bolt indicates the bond broken during ring opening transformation. B) Distance distribution between atoms C and C at the ends of the breaking bond under dihedral restraints of k= 10 kcal/mol. C) Distance distribution between atoms C and C at the ends of the breaking bond under no dihedral restraint. Bond interaction is scaled linearly by λ.

The resulting ΔΔG values are compared to those reported from calculations using the soft-bond method29 in Table 4. The comparison includes all the perturbation pairs studied using the soft-bond method except those that can be transformed using regular R-group perturbations. Contributions from the bonded terms are presented in Table S4. For macrocyclization transformations, the auxiliary restraints method successfully predicted 1→2 to be the only pair with significantly weakened binding affinity after macrocyclization. Macrocyclization was predicted to have mild effect on the binding affinity of compound 19 and strong enhancement on the binding affinity of compounds 3, 5, 6, and 33, which are consistent with the experimentally measured changes in affinity. Our method achieved an R2 and p-value of 0.91±0.06 and <10−3, which is the same as the reported results calculated using the soft-bond method. The MUE of the calculated ΔΔG values using our method is 0.88±0.23 kcal/mol, which is slightly higher than the MUE of the reported results calculated using the soft-bond method.

Our method achieved MUE and R2 of 1.09 kcal/mol and 0.74, respectively, for the transformation involving addition of sub-rings, which is better than the reported results calculated using the soft-bond method. However, the ΔΔG value of 16→13 calculated using auxiliary restraints has an error of > 2.0 kcal/mol .

For transformation involving ring contractions, our method combined with GAFF2 achieved MUE, R2 and p-value of 0.81±0.12, 0.58±0.10 and < 10−3. Our method successfully predicted that ring contractions, like 13→12, 14→12 and 26→27, have dramatic effects on the binding affinities. However, our results using GAFF appear less accurate than those reported using the soft-bond method in predicting the consequences of ring contractions involving smaller changes in binding affinities.

Though the overall correlation and MUE of our results are slightly better than the results calculated using the soft-bond method, it is important to note that macrocycles usually have high internal friction due to their cyclic nature and large sizes, which significantly dampens the sampling of their conformations in MD simulations. This can lead to issues in the calculation of ΔΔG values. For example, in previous studies of the same set of macrocycles using the soft-bond method29, MD simulation lengths of 5 ns and 25 ns led to differences in the calculated ΔΔG of up to 2.1 kcal/mol. It was reported that extending the simulation length from 5 ns to 25 ns lowered the overall MUE from 0.89 to 0.68 and improved the R2 from 0.73 to 0.78 for the soft-bond method. Thus, having macrocycles with initial conformations in high energy local minima affects both the accuracy and precision of the calculated ΔΔG, apart from issues with the quality of force fields and the method used for handling scaffold hopping83. Methods have been developed to aid the search of bioactive conformations of macrocycles, but they emphasize the search of conformations instead of giving thermodynamically equilibrated conformational ensembles84–85. For these reasons, we opted not to use the XFF force field to verify the source of errors for macrocycles whose calculated ΔΔG values significantly deviated from the experimental values. However, the results clearly showed that our method and the soft-bond method are of comparable applicability for studying various scaffold hopping transformations involving macrocycles29.

Overall correlation for scaffold hopping in drug-like compounds

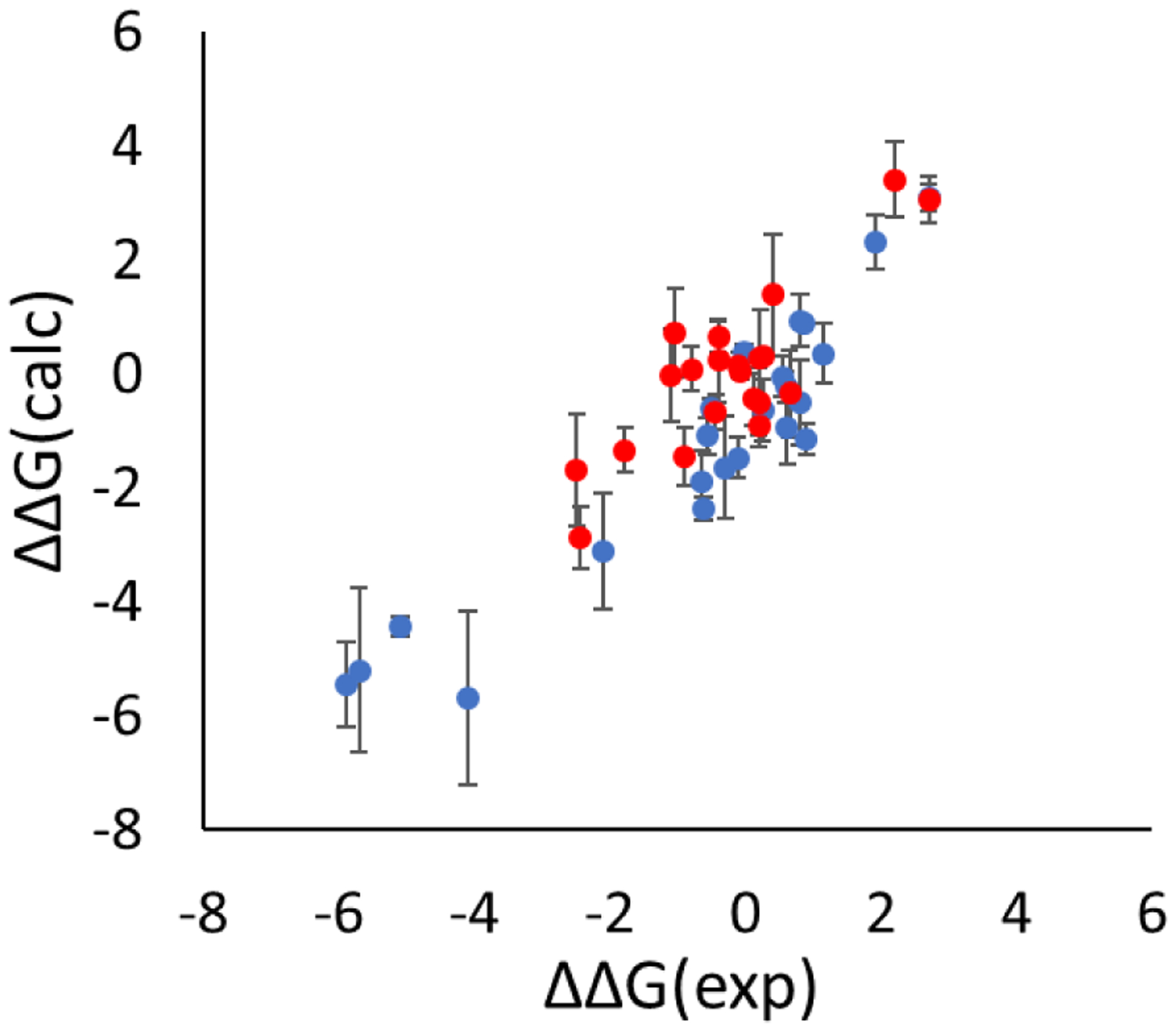

The correlation between the calculated (using auxiliary restraints) and experimental ΔΔG for all scaffold hopping transformations of drug compounds studied here is shown in Fig. 8. The correlation is excellent. For all the ring opening/closure, ring and linker contraction/expansion transformations of non-macrocyclic and macrocyclic compounds, the calculated and experimental ΔΔG values were fit to a trendline of y = 0.95*x − 0.23 with a p-value of <10−15. The MUE, R2 and Kendall’s τ were 0.77±0.07 kcal/mol, 0.79±0.04 and 0.54±0.04 respectively. A similar comparison cannot be tested for the softcore bond approach due to the lack of data for many of the transformations calculated here.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the calculated and experimental ΔΔG for the ring opening/closure transformations (blue dots), the linker and chain contraction/expansion transformations (red dots). A total of 44 transformations were studied. Calculated values used the auxiliary restraints method. Units: kcal/mol.

Proline mutations

Correct handling of the ring topology of the amino acid proline is critical for modeling mutations involving proline in free energy calculations. The gain and loss of the backbone conformations will not be accounted for in free energy calculations if the ring topology of proline remains intact or is absent during the perturbation. Here, proline to non-proline mutations and non-proline to proline mutations were treated as ring opening and closure transformations respectively using the auxiliary restraints.

We opted to validate our method by calculating the protein-protein binding free energy changes caused by proline mutations rather than calculating the thermostability change induced by proline mutations. The reason is that thermostability changes involve modeling both the folded and unfolded state of proteins. It is still infeasible to rigorously model the unfolded state of proteins in explicit water simulations as the unfolded state is highly expanded and dynamic. Though modeling the unfolded state using a short peptide model has shown successes in some cases86–88, the short peptide models will be inadequate if the unfolded state is highly structured and has significant long-range interactions, which is common for many proteins89–93.

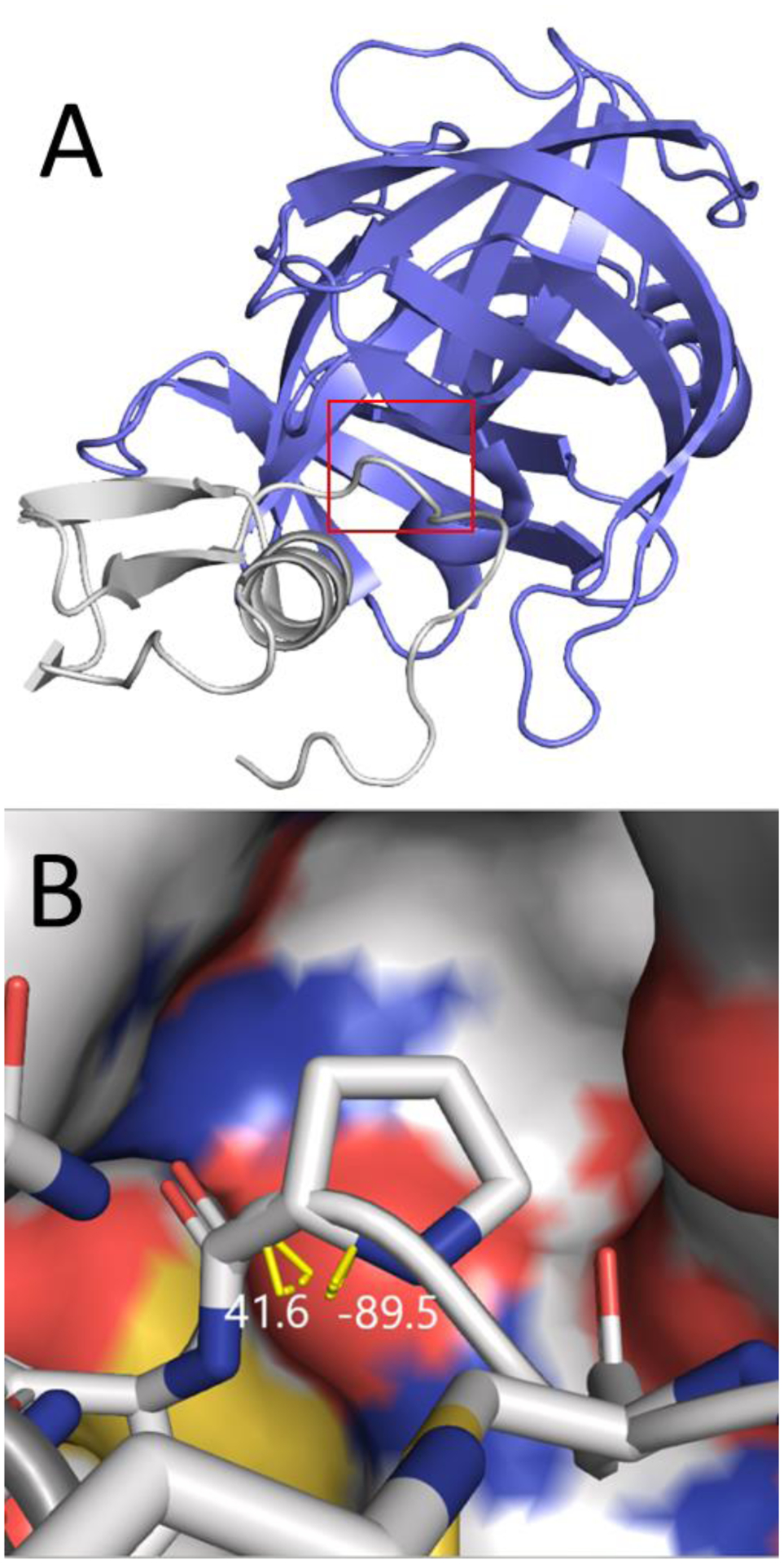

The effect of Leu18-to-Pro mutations on the binding of OMTKY3 to four of its receptors, bovine chymotrypsin Aa52 (CHYM), Streptomyces griseus proteinase B53 (SGPB), human leukocyte elastase54 (HLE) and subtilisin Carlsberg55 (CARL), were calculated using the auxiliary restraints method. The OMTKY3 binding complexes are popular testing systems used for validating the performance of free energy calculations on predicting ΔΔG caused by mutations23, 94. Leu18-to-Pro mutations have a deleterious effect on the binding between OMTKY3 and its receptor as Pro18 has to adopt a backbone conformation with φ/ψ=−89.5°/41.6°, which is energetically unfavorable, in the bound complex95 (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

A) Cartoon representation of the SGPB/OMTKY3-L18P complex (PDB code 2sgp). The red box indicates the enlarged area shown in panel B. B) The binding complex of OMTKY3-L18P and SGPB. SGPB is shown as a surface. OMTKY3 is shown as licorice, with P18 in the center. Carbon, Nitrogen, Oxygen and Sulfur atoms are shown in white, blue, red and yellow respectively. The backbone φ/ψ dihedrals are indicated by yellow bars and their values are shown in white. Hydrogen atoms and water are omitted.

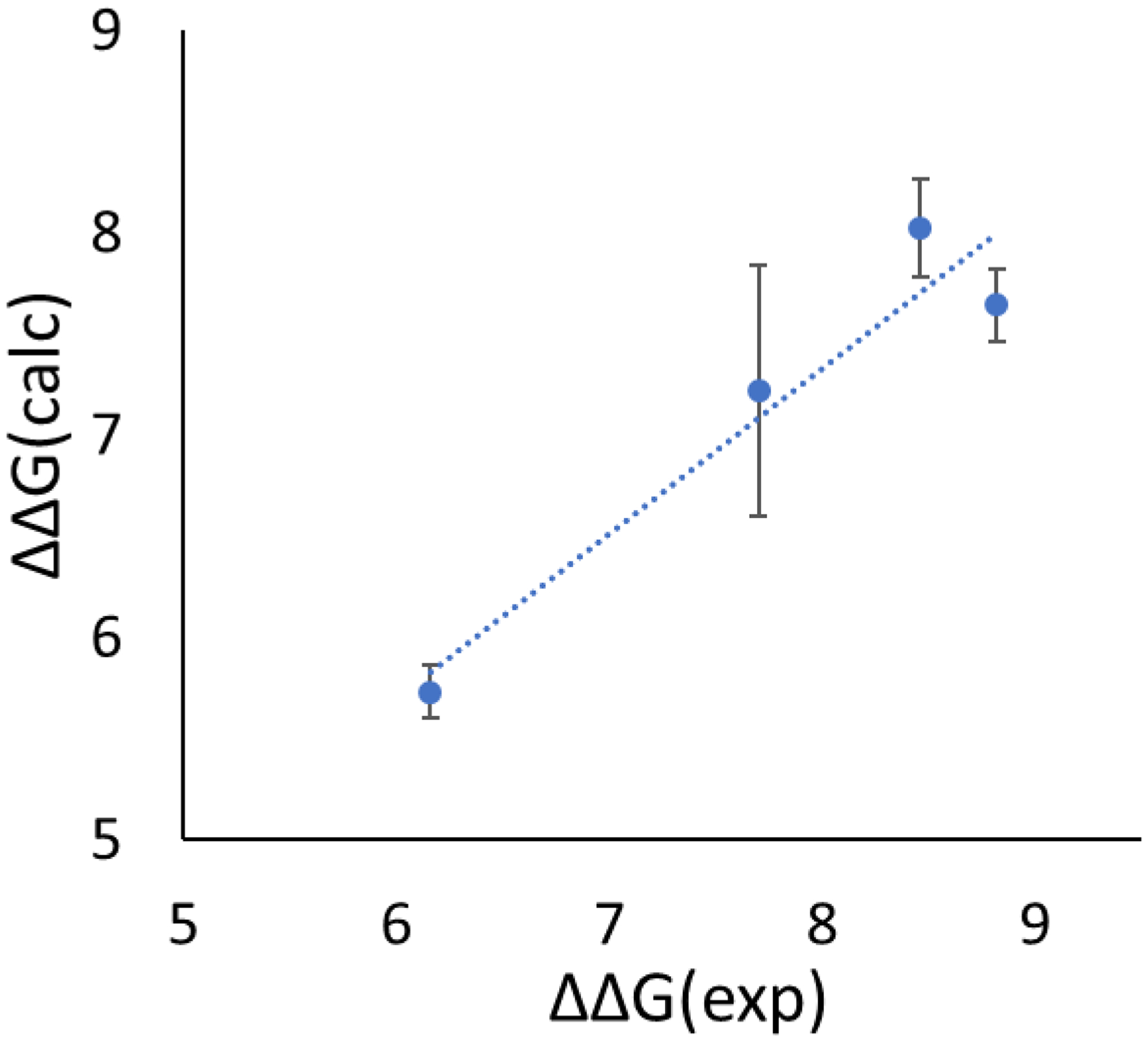

The comparison between the calculated and experimental ΔΔG values are presented in Table 5. The MUE and R2 are 0.63 ± 0.12 kcal/mol and 0.92 ± 0.07 respectively (Fig. 10), which is comparable to the MUE and R2 of 0.57 kcal/mol and 0.82 for the non-proline to non-proline mutations studied in our previous publication23. This indicates that the auxiliary restraints method extends the range of RBFE calculations to those involving ring transformations, while maintaining the same accuracy that we previously obtained for these systems for transformations that did not involve ring opening.

Table 5.

Comparison between the calculated (using auxiliary restraints) and experimental ΔΔG values of Leu18-to-Pro mutations in OMTKY3 complexes. (Units: kcal/mol).

| Calculated ΔΔG | Experimental ΔΔG95 | |

|---|---|---|

| CHYM/OMTKY3-L18P | 7.64 ± 0.18 | 8.82 |

| SGPB /OMTKY3-L18P | 8.02 ± 0.24 | 8.46 |

| HLE /OMTKY3-L18P | 5.73 ± 0.13 | 6.16 |

| CARL/OMTKY3-L18P | 7.22 ± 0.62 | 7.70 |

| MUE/R2/p-value | 0.63±0.12/0.92±0.07/p=0.04 |

Figure 10.

Comparison of the calculated and experimental ΔΔG for the Leu18-to-Pro mutations in OMTKY3 complexes. Units: kcal/mol.

Validation by comparing relative and absolute hydration free energy calculations

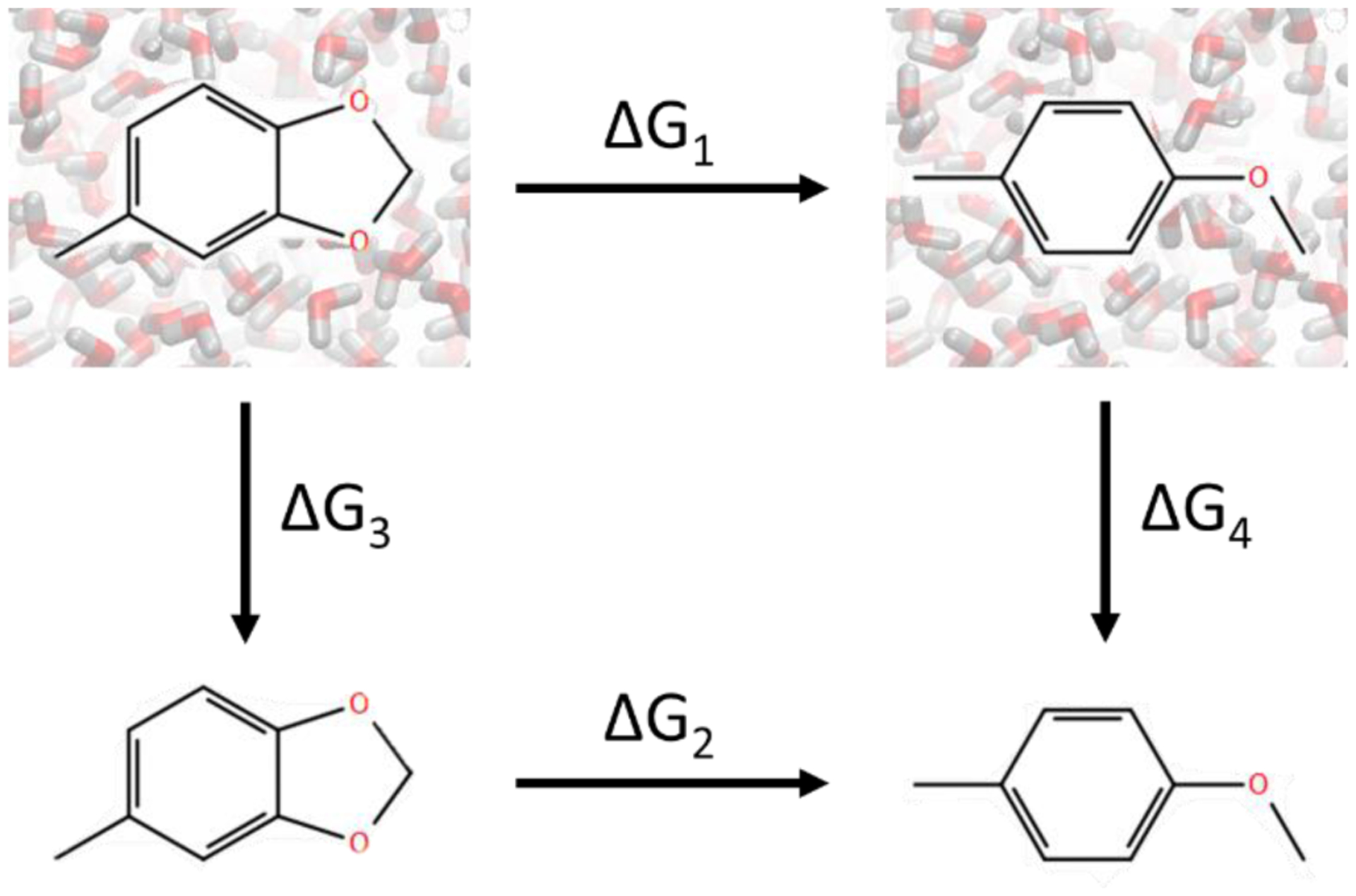

Relative and absolute HFE calculations have been used to validate the correctness of free energies calculated by major MD engines96. We carried out similar validation here to isolate the impact of the method from any inaccuracy of the force field, which complicates validation against experimental data. During the validation, four ΔG values were computed as indicated in Fig. 11. ΔG1 and ΔG2 are free energy changes that can be computed using dual topology, scaffold hopping approach or other methods to be validated. ΔG3 and ΔG4 are two absolute hydration free energy changes which can be computed by transferring the molecules from water to vacuum as a whole. Fully robust and rigorous methods should yield identical values of ΔG1 – ΔG2 and ΔG3 – ΔG4. Calculations of ΔG3 and ΔG4 have well established protocols and are straightforward to carry out. Thus, discrepancy between ΔG1 – ΔG2 and ΔG3 – ΔG4 usually indicates that the methods for calculating ΔG1 and ΔG2 are faulty. Unlike comparison between calculated and experimental ΔΔG of protein-ligand binding, in which discrepancy can be results of inadequate force field, comparison between ΔΔG values calculated by relative and absolute HFE changes avoids such obfuscation and ensures a more conclusive validation of the scaffold hopping method itself.

Figure 11.

The thermodynamic cycle for validating free energy calculations. ΔG1 and ΔG2 are the free energy changes calculated using ring opening transformations in water and in vacuum, respectively. ΔG3 and ΔG4 are the free energy changes calculated by transferring the whole molecules from water to vacuum without breaking bonds.

We validated the auxiliary restraints method by calculating ΔG1 – ΔG2 and ΔG3 – ΔG4 for perturbation pairs listed in Tables 2&3. To further enhance the convergence of the calculations, we extracted the core fragment analogs (Fig. S3) in which ring opening/closure, ring and linker contraction/expansion transformations were carried out to calculate the values of ΔG1 – ΔG2. Pairs FacX edo→4d, BACE-1 7→31 and ERα 3b→2d are excluded as they share highly similar or identical scaffold hopping transformations as pair FacX edo→4c, BACE-1 7→6 and ERα 3b→2e. The calculated values of ΔG1 – ΔG2, ΔG3 and ΔG4 are presented in Table 6. The overall MUE between ΔG1 – ΔG2 and ΔG3 – ΔG4 is 0.08 ± 0.03 kcal/mol (uncertainty calculated by bootstrapping resampling), which is comparable to the reported discrepancy observed in the previous validation on regular R-group perturbations using different major MD engines96. Both our ΔG values calculated using relative and absolute HFE calculations have larger standard deviation than the calculated ΔG in the previous validation96. We believe that this may be due to the use of GPU-accelerated MD simulations in this work. Nonetheless, the comparison between the values of ΔG1 – ΔG2 and ΔG3 – ΔG4 supports that the auxiliary restraints method is theoretically rigorous and correct for various scaffold hopping transformations.

Table 6.

Comparison between the calculated relative (using auxiliary restraints) and absolute hydration free energies for core fragment analogs. (Units: kcal/mol).

| Pairs | ΔG1 – ΔG2a | ΔG3a | ΔG4a | ΔG1 – ΔG2 – (ΔG3 – ΔG4)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHK1 21 →19 | −0.07 ± 0.27 | 4.07 ± 0.05 | 3.96 ± 0.19 | −0.19 ± 0.27 |

| CHK1 21→17 | 1.52 ± 0.23 | 4.07 ± 0.05 | 2.48 ± 0.10 | −0.08 ± 0.21 |

| CHK1 1→19 | −0.69 ± 0.20 | 3.36 ± 0.04 | 3.96 ± 0.19 | −0.09 ± 0.22 |

| CHK1 20→17 | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 3.32 ± 0.08 | 2.48 ± 0.10 | 0.15 ± 0.13 |

| CHK1 1-i→17 | 0.76 ± 0.12 | 3.36 ± 0.04 | 2.48 ± 0.10 | −0.12 ± 0.13 |

| FacX edo→4c | −1.88 ± 0.08 | 7.02 ± 0.08 | 8.92 ± 0.07 | 0.01 ± 0.11 |

| TPSB2 2→1-ii | −0.33 ± 0.05 | 3.64 ± 0.06 | 4.04 ± 0.04 | 0.07 ± 0.07 |

| BACE-1 7→6 | 3.16 ± 0.05 | 10.81 ± 0.10 | 7.60 ± 0.01 | −0.05 ± 0.09 |

| CHK1 21→20 | 0.81 ± 0.14 | 4.07 ± 0.05 | 3.32 ± 0.08 | 0.06 ± 0.14 |

| ERα 3b→2e | 4.81 ± 0.26 | 6.04 ± 0.11 | 1.22 ± 0.03 | −0.01 ± 0.23 |

| CatS 35→132 | 3.80 ± 0.13 | 4.51 ± 0.09 | 0.82 ± 0.10 | 0.10 ± 0.15 |

uncertainty calculated as standard deviation of the three independent runs.

uncertainty calculated by bootstrapping resampling.

Contribution from the bonded terms to the values of ΔG1 – ΔG2 are listed in Table S5. For most of the pairs, the bonded terms have significant magnitudes which cannot be neglected in ΔG1 – ΔG2. Clearly, neglecting the contribution from the bonded terms results in an unclosed thermodynamic cycle in Fig. 10.

Force constants and reference values of auxiliary restraints

For all the above perturbations, the strength and reference value (length or angle) of the auxiliary restraints were set to the values given in Methods. These values were our initial guesses and appear to be robust enough to cover all the transformations presented here, but it may be possible to further optimize these values to improve phase space overlap between intermediate states. In general, overly-weak restraints are inadequate to hold the bond at the desired distance during the breaking of bond interactions, while too-strong restraints are more difficult to be released. Optimal auxiliary restraint parameters may be system dependent, just as the number and spacing of λ windows used in a perturbation is. However, we believe that the auxiliary restraint parameters are likely to be less important for the calculated ΔΔG than other factors, such as docking poses and force fields, since they serve to constrain sampling, and the energetic impact of these restraints is expected to cancel across the free energy cycle.

Conclusions

In this study, we have presented a novel method for handling scaffold hopping transformations in RBFE calculations. The method relies on auxiliary restraints to prevent sampling of extreme bond distances during the breaking and forming of bonds. Free energy calculations involving ring opening/closure transformations, and ring contraction/expansion transformations were performed using the new method for datasets previously studied using the soft-bond method, augmented with additional transformation pairs. In total 44 transformations of drug-like compounds were tested. In addition, a linker contraction transformation was applied using the new method, which, to our knowledge, has not been reported before. Our method in combination with the GAFF2 force field shows satisfactory accuracy for most of the compounds. It is noteworthy that accuracy is comparable to the accuracy of transformations that did not involve these challenging topology changes. The auxiliary restraints method presented here achieved the same applicability as the soft-bond method, as demonstrated by the transformations involving macrocycles and the proline mutations. However, precautions should be taken when comparing the quantitative ΔΔG values calculated using the auxiliary restraints and the ΔΔG values calculated using the soft-bond approach, because different small molecule force fields were used in the two studies. An important feature of the auxiliary restraints method is that it is not tied to any specific force field, and can be used without modification as small-molecule force fields are improved97–100. We also showed that the method can be accomplished without modifying the code of simulation packages using examples calculated by off-the-shelf programs such as Amber.

The method was further validated by comparing calculated relative and absolute HFE using core fragment analogs. The validation shows that the auxiliary restraints can achieve closed thermodynamic cycles and path-independent ΔG values in HFE calculations. This is ensured by explicitly accounting contributions from all interaction terms in the total free energy changes, including the bonded terms, which have a non-negligible magnitude in both the RBFE and RHFE calculations.

In the examples demonstrated using Amber18, the ring opening, ring contraction and linker contraction transformations were conducted by splitting the perturbations into two stages. This results in more computational cost compared to transformations performed using a united protocol, in which perturbations can be accomplished using only one stage. However, to our knowledge, the united protocol is usually tied with the dual topology approach, which leaves dummy atoms doubly connected to the physical regions and has been shown to be theoretically inadequate for handling scaffold hopping transformation31, 34. Thus, caution must be taken when comparing methods involving breaking/forming of bonds with methods using the dual topology approach.

To apply the auxiliary restraints method on a large scale, platforms for analyzing molecular topologies, setting up multiple perturbation steps for applying and releasing the auxiliary restraints and preparing input files with the corresponding restraints for each compound will be useful. While a description of their development is beyond the scope of this work we note that the XFEP platform50 offers a highly automated workflow for handling the non-trivial preparations necessary for carrying out the auxiliary restraint method.

In summary, we have presented a new approach to calculate free energy changes arise from scaffold hopping transformations which can be utilized with existing MD code without modification. The accuracy and precision of the methodology were validated using a wide range of compounds including examples of macrocycles and protein-protein complexes. The method is expected to broaden the impact and applicability of RBFE calculations during drug discovery and protein characterization.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was partially supported by NIH GM078114, GM107104 and NSF grant MCB-1330259 along with the Shenzhen Special Fund for the Development of Strategic Emerging Industries. JZ was partially supported by the Laufer Center for Physical and Quantitative Biology at Stony Brook University.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

JZ, ZL(i), SL, CP, DF, XW, ZL(in) and MY are employees of Xtalpi Inc. TL, CS and DPR declare no conflicts.

Supporting information

Additional tables and figures referenced in the main text; files for the complex structures used in this study in pdb and sdf format, complete description and simulation inputs for the example transformations conducted using standard Amber18, XFF force field parameters for the transformations reported here.

References

- 1.Sun H; Tawa G; Wallqvist A, Classification of scaffold-hopping approaches. Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17 (7–8), 310–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osváth S; Gruebele M, Proline can have opposite effects on fast and slow protein folding phases. Biophys. J 2003, 85 (2), 1215–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abedini A; Raleigh DP, Destabilization of human IAPP amyloid fibrils by proline mutations outside of the putative amyloidogenic domain: Is there a critical amyloidogenic domain in human IAPP? J. Mol. Biol 2006, 355 (2), 274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan LE; Dunkelberger EB; Tran HQ; Cheng PN; Chiu CC; Cao P; Raleigh DP; de Pablo JJ; Nowick JS; Zanni MT, Mechanism of IAPP amyloid fibril formation involves an intermediate with a transient β-sheet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110 (48), 19285–19290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy JA; Nelson HCM, Proline in α-helical kink is required for folding kinetics but not for kinked structure, function, or stability of heat shock transcription factor. Protein Sci. 2000, 9 (11), 2128–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creighton TE, Possible implications of many proline residues for the kinetics of protein unfolding and refolding. J. Mol. Biol 1978, 125 (3), 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams AD; Portelius E; Kheterpal I; Guo J.-t.; Cook KD; Xu Y; Wetzel R, Mapping Aβ amyloid fibril secondary structure using scanning proline mutagenesis. Journal of Molecular Biology 2004, 335 (3), 833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi EJ; Mayo SL, Generation and analysis of proline mutants in protein G. Protein Eng., Des. Sel 2006, 19 (6), 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melnikov S; Mailliot J; Rigger L; Neuner S; Shin BS; Yusupova G; Dever TE; Micura R; Yusupov M, Molecular insights into protein synthesis with proline residues. EMBO Rep. 2016, 17 (12), 1776–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remeeva A; Nazarenko VV; Goncharov IM; Yudenko A; Smolentseva A; Semenov O; Kovalev K; Gülbahar C; Schwaneberg U; Davari MD; Gordeliy V; Gushchin I, Effects of proline substitutions on the thermostable LOV domain from Chloroflexus aggregans. Crystals 2020, 10 (4). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ain QU; Aleksandrova A; Roessler FD; Ballester PJ, Machine-learning scoring functions to improve structure-based binding affinity prediction and virtual screening. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci 2015, 5 (6), 405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C; Greene DA; Xiao L; Qi R; Luo R, Recent developments and applications of the MMPBSA method. Front. Mol. Biosci 2018, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitchen DB; Decornez H; Furr JR; Bajorath J, Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2004, 3 (11), 935–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiménez J; Škalič M; Martínez-Rosell G; De Fabritiis G, KDEEP: Protein–ligand absolute binding affinity prediction via 3D-convolutional neural networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2018, 58 (2), 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mobley DL; Klimovich PV, Perspective: Alchemical free energy calculations for drug discovery. J. Chem. Phys 2012, 137 (23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwanzig RW, High‐temperature equation of state by a perturbation method. I. Nonpolar gases. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1954, 22 (8), 1420–1426. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkwood JG, Statistical mechanics of fluid mixtures. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1935, 3 (5), 300–313. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee T-S; Allen BK; Giese TJ; Guo Z; Li P; Lin C; McGee TD; Pearlman DA; Radak BK; Tao Y; Tsai H-C; Xu H; Sherman W; York DM, Alchemical binding free energy calculations in AMBER20: Advances and best practices for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2020, 60 (11), 5595–5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cournia Z; Allen B; Sherman W, Relative binding free energy calculations in drug discovery: Recent advances and practical considerations. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2017, 57 (12), 2911–2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He X; Liu S; Lee T-S; Ji B; Man VH; York DM; Wang J, Fast, Accurate, and Reliable Protocols for Routine Calculations of Protein–Ligand Binding Affinities in Drug Design Projects Using AMBER GPU-TI with ff14SB/GAFF. ACS Omega 2020, 5 (9), 4611–4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raman EP; Paul TJ; Hayes RL; Brooks CL, Automated, accurate, and scalable relative protein–ligand binding free-energy calculations using lambda dynamics. J. Chem. Theory. Comput 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou J; Tian C; Simmerling C, Blinded prediction of protein-ligand binding affinity using Amber thermodynamic integration for the 2018 D3R grand challenge 4. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des 2019, 33 (12), 1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou J; Simmerling C; Raleigh DP, Dissecting the energetics of intrinsically disordered proteins via a hybrid experimental and computational approach. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123 (49), 10394–10402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schindler CEM; Baumann H; Blum A; Böse D; Buchstaller H-P; Burgdorf L; Cappel D; Chekler E; Czodrowski P; Dorsch D; Eguida MKI; Follows B; Fuchß T; Grädler U; Gunera J; Johnson T; Jorand Lebrun C; Karra S; Klein M; Knehans T; Koetzner L; Krier M; Leiendecker M; Leuthner B; Li L; Mochalkin I; Musil D; Neagu C; Rippmann F; Schiemann K; Schulz R; Steinbrecher T; Tanzer E-M; Unzue Lopez A; Viacava Follis A; Wegener A; Kuhn D, Large-scale assessment of binding free energy calculations in active drug discovery projects. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2020, 60 (11), 5457–5474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn B; Tichý M; Wang L; Robinson S; Martin RE; Kuglstatter A; Benz J; Giroud M; Schirmeister T; Abel R; Diederich F; Hert J, Prospective evaluation of free energy calculations for the prioritization of cathepsin L inhibitors. J. Med. Chem 2017, 60 (6), 2485–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenselink EB; Louvel J; Forti AF; van Veldhoven JPD; de Vries H; Mulder-Krieger T; McRobb FM; Negri A; Goose J; Abel R; van Vlijmen HWT; Wang L; Harder E; Sherman W; Ijzerman AP; Beuming T, Predicting binding affinities for GPCR ligands using free-energy perturbation. ACS Omega 2016, 1 (2), 293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L; Deng Y; Wu Y; Kim B; LeBard DN; Wandschneider D; Beachy M; Friesner RA; Abel R, Accurate modeling of scaffold hopping transformations in drug discovery. J. Chem. Theory. Comput 2016, 13 (1), 42–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beutler TC; Mark AE; van Schaik RC; Gerber PR; van Gunsteren WF, Avoiding singularities and numerical instabilities in free energy calculations based on molecular simulations. Chem. Phys. Lett 1994, 222 (6), 529–539. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu HS; Deng Y; Wu Y; Sindhikara D; Rask AR; Kimura T; Abel R; Wang L, Accurate and reliable prediction of the binding affinities of macrocycles to their protein targets. J. Chem. Theory. Comput 2017, 13 (12), 6290–6300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gentleman R; Eastman P; Swails J; Chodera JD; McGibbon RT; Zhao Y; Beauchamp KA; Wang L-P; Simmonett AC; Harrigan MP; Stern CD; Wiewiora RP; Brooks BR; Pande VS, OpenMM 7: Rapid development of high performance algorithms for molecular dynamics. PLOS Computational Biology 2017, 13 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu S; Wang L; Mobley DL, Is ring breaking feasible in relative binding free energy calculations? Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2015, 55 (4), 727–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boresch S; Karplus M, The role of bonded terms in free energy simulations: 1. Theoretical analysis. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 1998, 103 (1), 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boresch S; Karplus M, The role of bonded terms in free energy simulations. 2. Calculation of their influence on free energy differences of solvation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 1998, 103 (1), 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boresch S, The role of bonded energy terms in free energy simulations - Insights from analytical results. Molecular Simulation 2010, 28 (1–2), 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J; Wolf RM; Caldwell JW; Kollman PA; Case DA, Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem 2004, 25 (9), 1157–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harder E; Damm W; Maple J; Wu C; Reboul M; Xiang JY; Wang L; Lupyan D; Dahlgren MK; Knight JL; Kaus JW; Cerutti DS; Krilov G; Jorgensen WL; Abel R; Friesner RA, OPLS3: A force field providing broad coverage of drug-like small molecules and proteins. J. Chem. Theory. Comput 2015, 12 (1), 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakalian A; Jack DB; Bayly CI, Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem 2002, 23 (16), 1623–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorgensen WL; Chandrasekhar J; Madura JD; Impey RW; Klein ML, Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys 1983, 79 (2), 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maier JA; Martinez C; Kasavajhala K; Wickstrom L; Hauser KE; Simmerling C, ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory. Comput 2015, 11 (8), 3696–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JC; Gutell RR, Helix capping in RNA structure. PloS one 2014, 9 (4), e93664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams CJ; Headd JJ; Moriarty NW; Prisant MG; Videau LL; Deis LN; Verma V; Keedy DA; Hintze BJ; Chen VB; Jain S; Lewis SM; Arendall WB 3rd; Snoeyink J; Adams PD; Lovell SC; Richardson JS; Richardson DC, MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018, 27 (1), 293–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]