Summary

Background:

Medication non-adherence in paediatric ulcerative colitis (UC) has been associated with negative health outcomes including flares in disease activity. However, no studies to date have examined longitudinal adherence to maintenance medication in a prospective controlled trial.

Aims:

To determine whether objectively measured adherence to standardised mesalazine (mesalamine) therapy over time was related to remission at 52 weeks and the need for treatment escalation in newly diagnosed paediatric patients with UC.

Methods:

PROTECT (NCT01536535) was a prospective, inception cohort, multi-site study of paediatric patients aged 4–17 years with newly diagnosed UC followed for 52 weeks. Patients received standardised mesalazine, with pre-established criteria for escalation to thiopurines or anti-TNFα inhibitors. Patients used pill bottles with electronic caps to monitor mesalazine adherence. We tested whether longitudinal adherence to mesalazine predicted steroid-free remission at week 52 (i.e. quiescent disease on mesalazine alone with no corticosteroids ≥4 weeks prior) and need for treatment escalation (i.e. introduction of immunomodulators, calcineurin-inhibitors or anti-TNFα inhibitors).

Results:

Among 268 patients, average mesalazine adherence trajectories did not predict week 52 steroid-free remission. Declining adherence over time strongly predicted treatment escalation (β = −.037, P = .001). By month 6, adherence rate ≤85.7% was associated with treatment escalation.

Conclusions:

Non-adherence may have affected therapeutic efficacy of standardised mesalazine, thereby contributing to need for treatment escalation. Routine adherence monitoring for at least 6 months following treatment initiation and addressing adherence difficulties early in the disease course are recommended.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Medication non-adherence in youth with chronic conditions can lead to disease progression and poor treatment outcomes,1 unnecessary healthcare utilisation and higher healthcare costs.2 In youth with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), medication non-adherence has also been associated with increased healthcare costs and negative health outcomes, including more frequent flares in disease activity and greater colorectal cancer risk.3–6 Research has also associated poor adherence with negative psychosocial outcomes in children and adolescents, including anxiety and depression symptoms and lower health-related quality of life in those with IBD.7–10 Rates of medication non-adherence in paediatric IBD range from 2% to 93%, and non-adherence is higher in adolescents compared to younger youth.11,12 This is particularly problematic because up to 20% of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and 12% of individuals with ulcerative colitis (UC) are diagnosed before the age of 20.13

Attention to non-adherence to maintenance medication is critical in paediatric IBD as it may lead to unnecessary treatment escalation,12 which has implications for both healthcare utilisation and costs. Additionally, treatment escalation from maintenance therapy to steroids, immunosuppressive medications, biologic agents and surgical interventions involves making often difficult and complex medical decisions14 and has an impact on health-related quality of life.15 Non-adherence tends to be more prevalent for 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) medications such as mesalazine (mesalamine) compared to other oral medications such as immunomodulators (e.g. thiopurines), vitamins and supplements in this population.9,11 Aminosalicylates are compounds that contain 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) which reduce inflammation in the lining of the intestine and are used to induce and maintain remission in paediatric patients with mild to moderate UC. Rates of non-adherence to 5-ASA can be as high as 88% in adolescents with IBD compared to 64% for thiopurines.16 This may be due to increased barriers to adherence given that this treatment involves multiple doses per day and treatment complexity has been documented as a primary predictor of trajectories of medication adherence in youth with IBD.17,18 Barriers to mesalazine adherence reported by adults with IBD are similar to barriers to general medication adherence endorsed by youth, including doubts about efficacy and pill characteristics (eg size, quantity).19,20

In the adult IBD literature, mesalazine adherence has been examined longitudinally, although not in the context of a clinical trial. One study of adults with ulcerative colitis followed patients in remission for 6 months while on maintenance mesalazine. Findings indicated that those who were non-adherent experienced more than five times greater risk of disease relapse than those who were adherent.21 A retrospective 10-year cohort study documented that adults who were non-adherent had a greater risk of flares in disease activity compared to those who were adherent to mesalazine.22

However, these trials did not utilise electronic monitoring of medication adherence, despite recommendations that electronic monitoring be used in clinical trials. In subsequent clinical trials of mesalazine in adults with UC, electronically measured adherence has been found to best distinguish between participants who relapsed and those who remained in remission, though the independent relationship between adherence and remission was not statistically significant.23 While many longitudinal studies of medication adherence in paediatric IBD have used electronic monitoring, few have examined adherence to mesalazine monotherapy longitudinally in favour of research investigating adherence to thiopurine monotherapy or thiopurine/5-ASA combination therapy.16,17,24–26

These existing paediatric studies have several limitations, including single-site designs and examining both newly and previously diagnosed samples, which may contribute to variability in health outcomes related to disease duration and prior treatment exposure. Predicting Response to Standardized Paediatric Colitis Therapy (PROTECT; clincaltrials.govv, NCT01536535) is a multi-centre inception cohort study designed to evaluate the efficacy of standardised treatments for children with newly diagnosed UC. Findings from the trial provide both guidelines to assess how youth newly diagnosed with UC respond to standardised treatment and potential predictors of treatment response and failure, including medication adherence.27

1.1 |. Aims and hypotheses

Aim 1 of the present study was to examine the relationship between electronically measured adherence over study duration and steroid-free remission at the study culmination (week 52). We sought to examine this association for the entire sample, as well as for a subset of participants who met criteria for presenting with mild disease at baseline. We hypothesized that higher adherence over the study duration would predict week 52 steroid-free remission, particularly for the subsample with mild disease at baseline. Aim 2 examines whether adherence to mesalazine was predictive of participants meeting criteria for treatment escalation. We hypothesized that poorer adherence would predict need for treatment escalation. Aim 3 sought to identify a clinical cut-point for adherence, such that adherence rates at or below this cut-point would be clinically indicative of a need for treatment escalation.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

PROTECT was a prospective, inception cohort study that enrolled paediatric patients ages 4–17 undergoing evaluation for ulcerative colitis across 29 centres in North America. Those who received a diagnosis of UC after endoscopic confirmation with biopsies were started on either a standardised mesalazine (Pentasa®, Shire US Inc) or corticosteroid treatment based on disease severity, with pre-established criteria for treatment escalation to thiopurines, calcineurin inhibitor or anti-TNFα agents. Mesalazine was started with weight-based dosing, ranging from 50 mg/kg to 75 mg/kg per day. Patients started on oral or intravenous corticosteroids (Prednisone dose of 1–1.5 mg/kg/day) were guided to start mesalazine after 2 weeks of corticosteroids if disease activity was controlled, and corticosteroid tapering was performed in a standardised manner. Need for additional medical therapy (ie treatment escalation) was based on lack of sustained response/remission with use of mesalazine as a maintenance agent, or an adverse reaction to mesalazine preventing its use. Standardised treatment guidelines with indications for adding mesalazine, stopping steroids or escalation to anti-TNFα therapy or immunomodulators may be found in the supplementary index of the PROTECT main outcomes article (Lancet. 2019; 393:1708–20).

The primary outcome of the year-long study was steroid-free remission at week 52 without the need for medical escalation or colectomy. Throughout the study, those participants taking mesalazine utilised pill bottles equipped with electronic TrackCap technology (Medication Event Monitoring System [MEMS®], Aardex Group), to monitor daily mesalazine adherence. Each site’s Institutional Review Board approved the protocol and safety monitoring plan.

2.2 |. Participants

Four hundred twenty-eight patients were enrolled in PROTECT and started medical therapy of either oral mesalazine or oral/intravenous corticosteroids. Of these a total of 289 participants were prescribed mesalazine as maintenance therapy and monitored for adherence via MEMS track caps. Of these, 21 participants were disqualified due to the following reasons: participant chose to withdraw from the study before week 52 (n = 13), significant deviations from standard treatment regimen (ie gaps in treatment of more than 28 days; n = 6), and participant refused standardised treatment regimen (n = 2). Two hundred sixty-eight participants were eligible for the study.

2.3 |. Outcome variables

The primary outcome for Aim 1 was steroid-free remission at week 52, defined as: clinical remission (PUCAI < 10) with no corticosteroids for ≥4 weeks immediately prior to week 52, no colectomy and no medical therapy beyond mesalazine. The outcome for Aim 2 was a binary indicator of need for treatment escalation at any time in the 52 weeks. Treatment escalation involved introducing immunomodulators (IM), calcineurin-inhibitors (ciclosporin or tacrolimus), anti-TNFα inhibitors or undergoing a colectomy. The outcome for Aim 3 was the adherence percentage that indicated a need for treatment escalation.

2.4 |. Measures

2.4.1 |. Demographic information

At the initial study visit, patients and families provided demographic information (eg age, sex, race/ethnicity) via a study-developed form.

2.4.2 |. Disease information

Clinical disease activity was assessed via the Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI),28 a validated, highly responsive and widely adopted measure of disease activity.29 Scoring is based on data from patient report, clinical examination, laboratory values and growth parameters. The PUCAI uses a scoring algorithm to classify patients into the following disease activity categories based on total score: inactive (PUCAI < 10), mild (10–30), moderate (35–60) or severe (≥65).

In the current study, we sought to evaluate whether adherence trajectory uniquely predicted steroid-free remission at 52 weeks for the whole sample as well as for a subsample of patients with mild disease presentation at baseline. Mild disease presentation was defined using a combination of baseline disease activity (PUCAI < 45) and initial therapy (mesalazine or oral CS with mesalazine prescribed by month 3). The cut-point of PUCAI < 45 was based upon previous observations of this cohort, in which PUCAI < 45 was identified as a significant predictor of steroid-free remission at weeks 1227 and 52.30

2.4.3 |. Laboratory data

Clinical and routine laboratory values were collected at diagnosis (baseline). Laboratory data used in the current study included baseline haemoglobin levels, Vitamin D level and lower rectal biopsy eosinophil count. These variables were selected as covariates in the current study based on previous findings from the PROTECT trial, which found higher baseline haemoglobin was associated with steroid-free remission at week 52, and pre-treatment Vitamin D <20 ng/mL and rectal eosinophils <32/hpf were associated with treatment escalation to anti-TNFα.30

2.4.4 |. Mesalazine adherence

Mesalazine adherence was monitored via Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) Track Caps (AARDEX Ltd). Participants were instructed to use electronic MEMS Track Caps to track daily mesalazine adherence. Given that not all participants were started on mesalazine treatment, the first of three consecutive days of at least one bottle opening was documented as the start of a participant’s adherence data. Participants took mesalazine either once (n = 10) or twice per day (n = 258) and received an adherence score for each day based on the percentage of actual doses taken compared to expected (prescribed) doses as recorded by MEMS Track Cap openings (eg 0%, 50% or 100%). Monthly adherence averages were computed for each participant from start of mesalazine treatment (as defined above) until study completion or until first occurrence of treatment escalation. Monthly averages were utilised in all subsequent analyses.

2.5 |. Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in Mplus (version 8.2)31 using adherence data from months 2 through 7 of the study, as there were sufficient complete data during this period to conduct longitudinal growth models (≤30% missing data).32 Month 1 data were excluded as only 24% (N = 63) of participants were started on mesalazine with electronic adherence monitors immediately following their baseline visit, whereas by month 2, mesalazine adherence data was available for 81% (N = 216) of the sample. Beginning in month 8, more than 30% of participants had discontinued mesalazine due to treatment escalation and therefore there was insufficient data to examine longitudinal trends in adherence for the whole sample beyond month 7. For a given month during the study period, adherence data were missing for 21.7% of participants, on average.

2.5.1 |. Aim 1: Longitudinal adherence predicting steroid-free remission

Statistical analyses used longitudinal growth curve modelling to test how the average trajectory quantifying adherence to mesalazine over the 6-month period predicted corticosteroid-free remission at week 52 (distal binary outcome). Control covariates were participant age, sex, need for treatment escalation during the trial, as well as baseline disease characteristics, including disease activity (PUCAI) and haemoglobin levels. PUCAI and haemoglobin levels were included as covariates due to findings from the PROTECT trial demonstrating that lower baseline PUCAI and higher baseline haemoglobin were associated with steroid-free remission at week 52.30 The model was first estimated for all participants (N = 268), then estimated for the subset of participants defined as mild at baseline (n = 99) based on disease activity (PUCAI < 45) and initial treatment. The same model (including all aforementioned covariates) was also estimated for participants with no treatment escalation during the study (n = 164).

2.5.2 |. Aim 2: Longitudinal adherence predicting need for treatment escalation

Longitudinal growth curve modelling was also used to test whether longitudinal adherence to mesalazine was associated with need for treatment escalation during the study (binary distal outcome). Covariates were age, sex and baseline disease characteristics, including PUCAI, haemoglobin, Vitamin D and lower rectal biopsy eosinophil count. Vitamin D level at baseline and lower rectal biopsy eosinophil count were included as additional covariates in the model predicting need for rescue as findings from the PROTECT trial demonstrated individuals with pre-treatment Vitamin D levels of 25(OH)D <20 ng/mL and pre-treatment rectal eosinophils <32/hpf were more likely to escalate to anti-TNFα.30 Of note, the current study modelled the association between longitudinal adherence and any treatment escalation, therefore our sample was not identical to the previous study predicting only escalation to anti-TNFα. By controlling for relevant baseline disease characteristics, we were able to examine whether adherence had an independent effect on need for treatment escalation.

2.5.3 |. Aim 3: Modelled adherence trajectories for treatment escalation and no escalation groups

Additional analyses were conducted to identify the adherence cut-point at which, or below, indicated the need for treatment escalation. First, we conducted a longitudinal growth model using the same patient/clinical factors as above to predict adherence trajectories separately for the escalated and never escalated groups. Individual participant trajectory values with standard errors were obtained. Next, average adherence trajectory standard errors (SE) were calculated separately for the escalated and never escalated groups. Separate adherence trajectories for both groups were plotted along with 95% CIs calculated for the observed trajectory SE data. The point at which the 95% CIs for the adherence trajectories did not overlap indicated the adherence percentage which predicted the need for treatment escalation.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Study demographics and clinical characteristics

The 268 participants had a mean (SD) age of 12.3 (3.3) and 50.0% were females. Baseline clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Mean (SD) PUCAI at baseline was 48.1 (19.2), and 25.5% (n = 67) had mild or inactive disease (PUCAI < 35) at baseline. Ninety-five participants were initiated on mesalazine only and 173 were initiated on corticosteroids (96 on oral and 77 on intravenous) and received mesalazine after responding to steroids. In the overall study sample, mean adherence to mesalazine (SD) declined each month, from 86.8% (19.6) in month 2 to 78.8% (24.9) in month 7 (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics grouped by outcomes

| Clinical values | All patients (N = 268) | Week 52 steroid-free remission (n = 122) | No week 52 steroid-free remission (n = 146) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PUCAIa, mean (SD) | 48.1 (19.2) | 45.2 (20.7) | 50.3 (17.6) | .038 |

| Haemoglobin, <100, n (%) | 53 (19.8%) | 16 (13.1%) | 37 (25.3%) | .009 |

| Clinical values | All patients (N = 268) | No Treatment Escalation (n = 164) | Treatment Escalation (n = 104) | P value |

| PUCAIa, mean (SD) | 48.1 (19.2) | 44.7 (19.9) | 53.5 (16.8) | <.0001 |

| 25(OH) Db, mean (SD), ng/mL | 30.0 (9.2) | 30.4 (9.3) | 29.5 (9.1) | .005 |

| Rectal biopsy eosinophil peak count | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 44.2 (30.7) | 46.6 (31.5) | 40.4 (29.1) | .145 |

| Count >32/hpfc, n (%) | 142/228 (62.3%) | 92/140 (65.7%) | 50/88 (56.8%) | .019 |

P values comparing groups (week 52 steroid-free remission versus no steroid-free remission) are from ANOVA tests with continuous variables.

Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index.

25-hydroxyvitamin D.

High power field.

TABLE 2.

Mean adherence rate by month

| Month | No. (%) of 268 with data | Mean adherence rate, % (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 216 (81) | 86.8 (19.6) |

| 3 | 228 (85) | 82.9 (22.8) |

| 4 | 219 (82) | 81.4 (24.6) |

| 5 | 207 (77) | 79.4 (26.9) |

| 6 | 201 (75) | 78.2 (26.9) |

| 7 | 188 (70) | 78.9 (24.9) |

At 52 weeks, 122 patients achieved steroid-free remission and 146 did not. Of those with no steroid-free remission at week 52, 80 received IV steroids and 128 received oral steroids at some point during the study and 29 were currently taking steroids at week 52. Of those in steroid-free remission at week 52, 42 received only one initial steroid treatment at ≤16 weeks and 43 did not receive any steroid treatment for the duration of the study. Among those with steroid-free remission, the mean number of weeks in sustained steroid-free remission at week 52 was 26.5 (SD 18.0).

One hundred and four participants required treatment escalation (ie rescue) prior to the end of the study, and mean (SD) days from baseline to rescue was 176.3 (88.2). Of those, 31 patients were prescribed anti-TNFα as first rescue medication, 1 was prescribed a calcineurin inhibitor and 72 were prescribed an immunomodulatory medication. As per the study definition of steroid-free remission requiring treatment with mesalzine alone at week 52, no participants requiring treatment escalation achieved steroid-free remission at week 52. Of the 164 with no treatment escalation, 122 achieved steroid-free remission at week 52.

3.2 |. Aim 1: association between longitudinal adherence and week 52 steroid-free remission

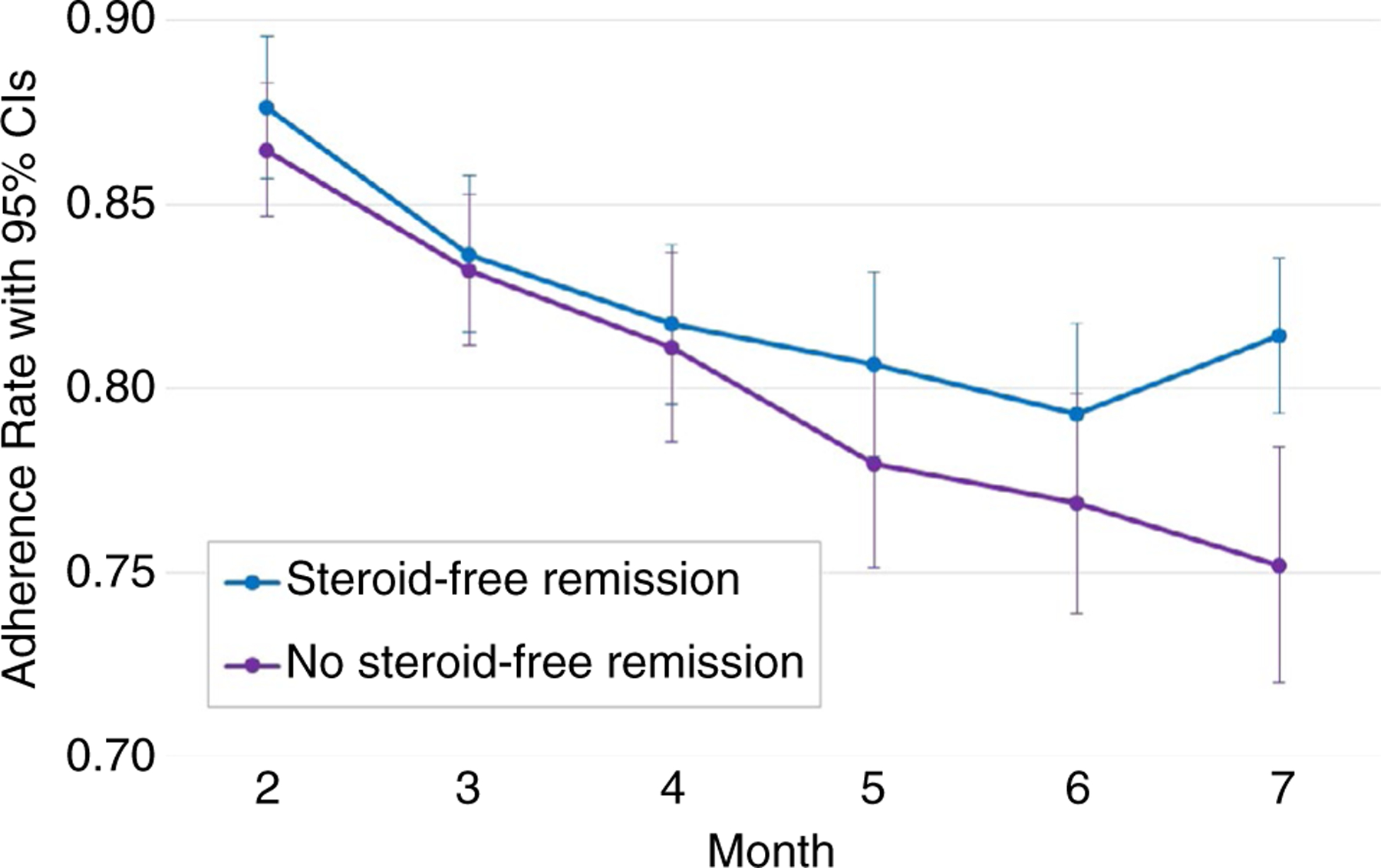

For the model testing the association between adherence and steroid-free remission with the entire sample (N = 268), after controlling for the effects of participant age, sex, need for treatment escalation and baseline disease activity (PUCAI) and haemoglobin levels, the average trajectory quantifying adherence to mesalazine did not predict week 52 steroid-free remission. Observed monthly adherence rates for the group with week 52 steroid-free remission (n = 122) and the group that did not achieve week 52 steroid-free remission (n = 146) are shown in Figure 1. Average adherence in the no steroid-free remission group was lower than the steroid-free remission group for every month of the study. However, the longitudinal growth did not show a significant group effect on adherence intercept or slope.

FIGURE 1.

Observed monthly average mesalazine adherence rates with 95% confidence intervals for Week 52 ‘Steroid-Free Remission’ (n = 122) and ‘No Steroid-Free Remission’ (n = 146) groups

For the model testing, the association between adherence and steroid-free remission in the subsample of participants who were defined as having mild disease at baseline (n = 99), after controlling for the same participant and disease-related characteristics as above, adherence trajectory did not predict week 52 steroid-free remission. Similarly, for the model testing the association between adherence and steroid-free remission in the subsample of participants with no treatment escalation (n = 164), which included the same covariates as above, the average trajectory quantifying adherence to mesalazine did not predict week 52 steroid-free remission.

3.3 |. Aim 2: association between longitudinal adherence and treatment escalation

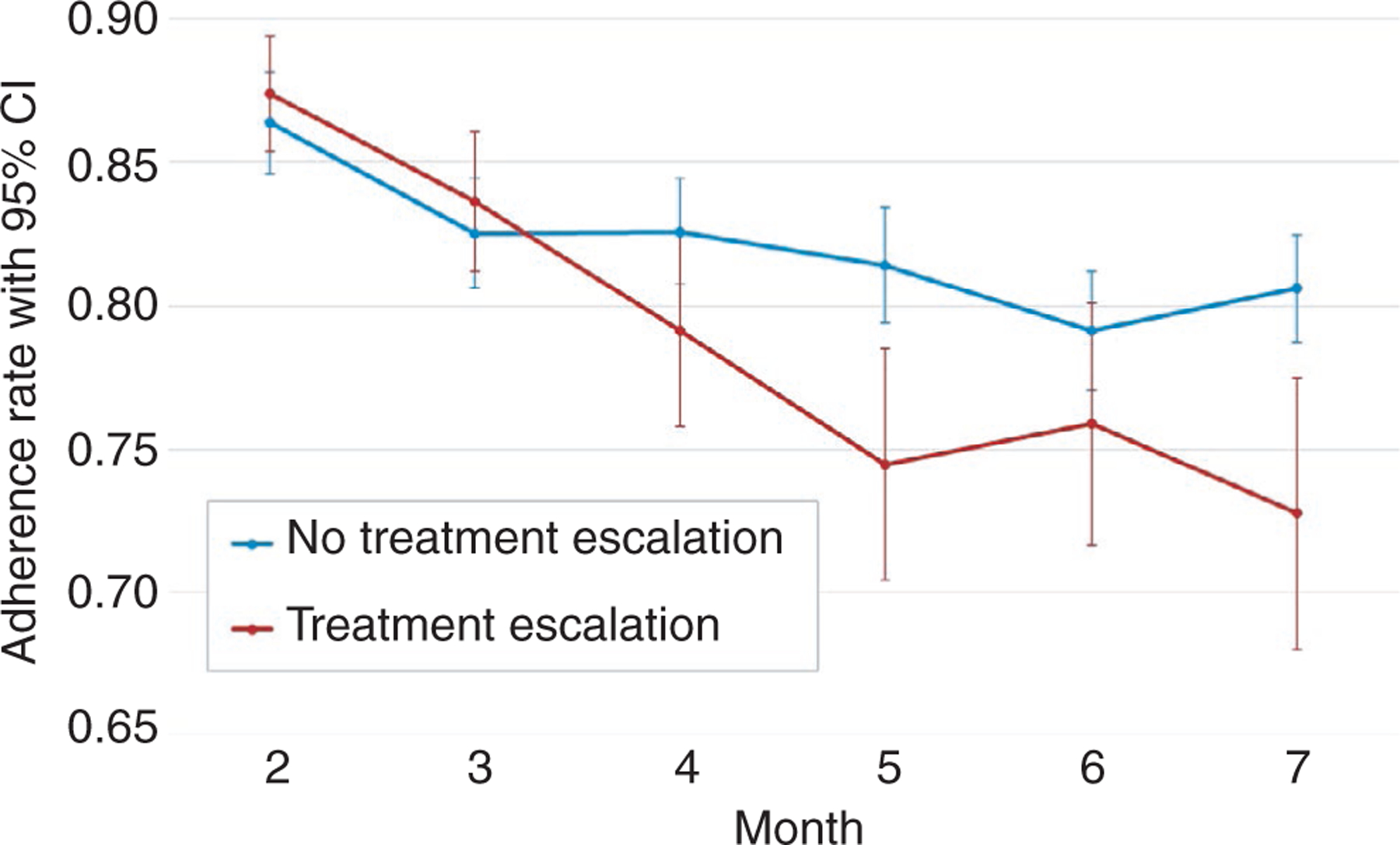

After controlling for age, sex and baseline disease characteristics (PUCAI, haemoglobin level, Vitamin D level and lower rectal biopsy eosinophil count), adherence trajectory slope variance was a significant predictor of the need for treatment escalation (β = −.363, P < .001), such that declining adherence over time strongly predicted the need for treatment escalation. Observed monthly average adherence rates for participants with no treatment escalation (n = 164) and participants that required treatment escalation (n = 104) are shown in Figure 2; participants who were escalated versus never escalated showed greater declines in adherence over time.

FIGURE 2.

Observed monthly average mesalazine adherence rates with 95% confidence intervals for ‘No Treatment Escalation’ (n = 164) and ‘Treatment Escalation’ (n = 104) groups

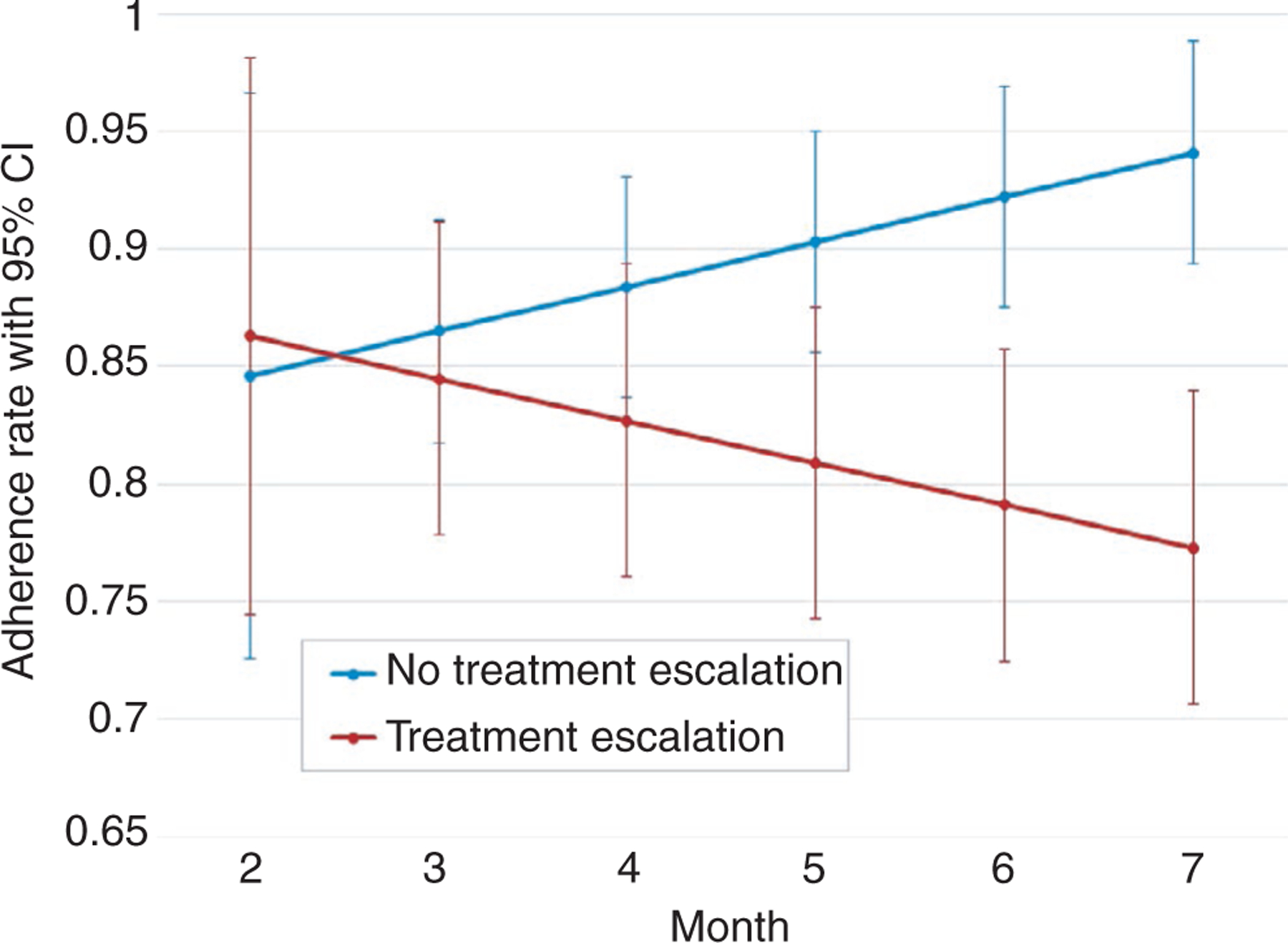

3.4 |. Aim 3: modelled adherence trajectories in treatment escalation and no escalation groups

From the model of treatment escalation predicting adherence (Aim 2), participant-specific trajectory means and standard errors were obtained from Mplus and averaged within both the escalated and never escalated groups so that group-specific model-based adherence trajectories with 95% CIs could be plotted. Figure 3 shows that by month 6, the 95% confidence intervals for the adherence trajectories of the two groups no longer overlapped, demonstrating that an adherence percentage at or below 85.7% (upper bound 95% CI for escalated group) was associated with the need for treatment escalation.

FIGURE 3.

Model-based mesalazine adherence trajectories with 95% confidence intervals for ‘No Treatment Escalation’ and ‘Treatment Escalation’ groups. Trajectories were calculated for each group using trajectory standard error and slope data from model of treatment escalation predicting adherence. By month 6, the 95% CIs for the two groups no longer overlapped, indicating that an adherence percentage at or below 85.7% (upper bound 95% CI for ‘Treatment Escalation’ group) was indicative of need for treatment escalation

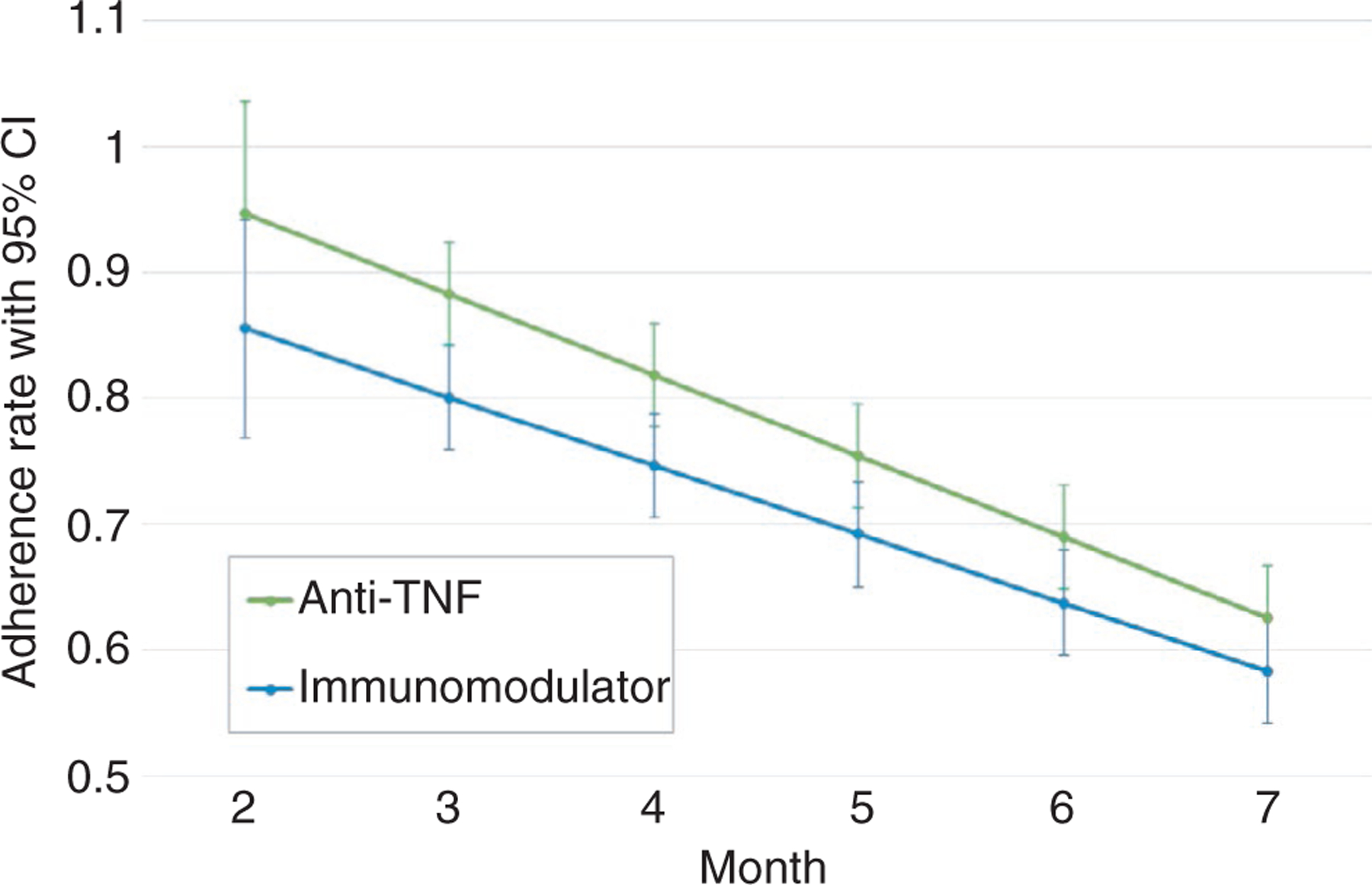

As an additional exploratory analysis, we modelled group-specific mesalazine adherence trajectories for only participants with treatment escalation by type of first rescue therapy (anti-TNFα versus immunomodulators). The immunomodulator group had a significantly lower adherence intercept (β = −.266, P = .047), however the slopes between groups were not significantly different, meaning adherence declined at similar rates for both groups (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Model-based adherence to mesalazine trajectories with 95% confidence intervals for participants with treatment escalation (n = 103). Trajectories were calculated for each group using trajectory standard error and slope data from model of rescue intervention type predicting adherence. The green line represents patients who were prescribed Anti-TNF as first rescue medication (n = 31) and the blue line shows patients who were prescribed an immunomodulator as first rescue medication (n = 72). Only one patient was prescribed a calcineurin inhibitor for first rescue medication, and no patients received colectomy as first rescue intervention, therefore these groups were not modelled

4 |. DISCUSSION

This is the first study to objectively measure adherence to standardised mesalazine therapy in the context of a paediatric UC inception cohort study. Average adherence by month was high (86.8% in month 2); however, adherence deteriorated over the 6-month period (78.9% in month 7). Contrary to our hypothesis, adherence to standardised mesalazine therapy did not predict achievement of steroid-free remission at week 52 for the whole sample nor the subsample of participants defined as having mild disease at baseline. These findings reflect the complexity of achieving remission in youth with UC, as a number of factors have been shown to contribute to future remission status, including disease activity early in the disease course.31 Specifically, in the PROTECT main study, lower baseline severity, higher baseline haemoglobin and initial response to therapy (ie clinical remission at week 4) were all significantly associated with steroid-free remission at week 52.30 In adults with UC, electronically monitored adherence to mesalazine was the distinguishing factor between disease relapse and remission. However, like findings from the current study, adherence alone did not independently predict future remission.21

Declining adherence to mesalazine over the 6-month period was highly predictive of need for treatment escalation. This relationship held even after controlling for other known factors associated with need for therapeutic escalation, including baseline severity, haemoglobin, Vitamin D and rectal eosinophil count. Results indicate that non-adherence may have threatened the efficacy of standardised mesalazine therapy, especially for youth presenting with mild disease, thereby contributing to the need for treatment escalation due to disease relapse during the study period. Of note, the PROTECT study used a relatively high mesalazine dosing schedule of about 67 mg/kg per day (maximum 4 g) compared to previous paediatric studies. Treatment escalation due to relapse is a common consequence of non-adherence in youth with IBD33 and can result in increased morbidity21 as well as increased costs to the healthcare system and family.3,4 Importantly, declining or suboptimal adherence to maintenance medication is not a basis for treatment escalation; rather, the decision to escalate treatment is based on disease response (or lack of response) to maintenance medication. Given the emphasis on achieving optimal nutrition, growth and development in this population, treatment escalation from 5-ASA is often indicated to promote mucosal healing and avoid steroid dependence. Despite these advances in treatment, compared to adults, the rate of surgical needs in youth with UC remains higher,33 which may be indicative of continued difficulties with adherence to immunomodulators or biologic medications as reported in the literature.7,16,34 As such, it is important for providers to recognise and intervene around non-adherence whether the patient is on maintenance therapy or another type of therapy. Behavioural interventions have been shown to effectively increase adherence to medications, which could support optimal disease control for patients who respond to mesalamine. Similarly, for patients who do not respond to maintenance therapy and require treatment escalation, it is equally important to monitor adherence and provide adherence promotion intervention if needed.

This study was the first to evaluate differences in group-specific adherence trajectories for patients who required treatment escalation versus those who did not. By plotting trajectories for each group, we were able to identify the point at which the 95% confidence intervals between the two group trajectories no longer overlapped. At month 6, an adherence rate at or below 85.7% distinguished participants who needed treatment escalation from those who did not. This finding has critical clinical implications for adherence monitoring and management. First, in contrast to the majority of previous IBD adherence studies, which have utilised a consensus cut-point and classify non-adherence as <80%7,11 the current study showed that when adherence fell below 86%, the likelihood of treatment escalation significantly increased. Second, the two adherence trajectories did not diverge until month 6, indicating the importance of continued assessment of adherence over at least the first 6 months following diagnosis in order to identify whether adherence is deteriorating and the likelihood that adherence may be a factor in the need for treatment escalation.

These findings contribute to our understanding of the consequences of non-adherence to mesalazine in newly diagnosed youth with UC; however, the present study is not without limitations. First, adherence data were collected in the context of a pharmaceutical clinical trial and not a behavioural trial; therefore, participants did not receive an adherence intervention. Future clinical trials incorporating objective measures of adherence may benefit from including evidence-based adherence interventions (eg problem-solving skills training) to enhance understanding of the role of adherence in the need for treatment escalation in youth with paediatric IBD. Second, missing data impacted our ability to assess adherence across the entirety of the study duration; however, we were able to effectively assess trajectories across a 6-month period and draw statistically significant and meaningful conclusions from the data. Third, while our models accounted for baseline disease activity, we were not able to account for changes in disease severity over time in our models.

Overall, findings from the present study suggest that among newly diagnosed youth with UC, declining adherence to mesalazine and rates of adherence to mesalazine of less than 86% both predict likelihood of treatment escalation, even in the context of other disease-related factors. Therefore, targeting adherence difficulties early in the disease course is necessary in reducing the likelihood of the need for treatment escalation in this population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of personal and funding interests:

There are no personal or funding conflicts of interest to declare for any authors.

Funding information

Support for this study was provided by NIDDK 5U01DK095745 and P30 DK078392, Integrative Morphology and Gene Expression Cores, NIDDK DK043351 and AT009708, CSIBD DK043351, Center for Microbiome Informatics and Therapeutics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology; www.protectstudy.com, Clinical trials: NCT 01536535.

REFERENCES

- 1.Santer M, Ring N, Yardley L, Geraghty AW, Wyke S. Treatment non-adherence in pediatric long-term medical conditions: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies of caregiver views. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrady ME, Hommel KA. Medication adherence and health care utilization in pediatric chronic illness: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132:730–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins PD, Rubin D, Kaulback K, Schoenfield P, Kane S. Systematic review: impact of non-adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid products on the frequency and cost of ulcerative colitis flares. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hommel KA, McGrady ME, Peugh J, et al. Longitudinal patterns of medication nonadherence and associated health care costs. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1577–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliva-Hemker MM, Abadom V, Cuffari C, Thompson RE. Nonadherence with thiopurine immunomodulator and mesalamine medications in children with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samson CM, Mager D, Frazee S, Yu F. Remission in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease correlates with prescription refill adherence rates. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan W, Chen A, Tiao D, Selinger C, Leong R. Medication adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. Intestinal Research. 2017;15:434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: the collective impact of barriers to adherence and anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;37:282–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hommel KA, Greenley RN, Maddux MH, Gray WN, Mackner LM. Self-management in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:250–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed-Knight B, Lewis JD, Blount RL. Association of disease, adolescent, and family factors with medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;36:308–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeLeiko NS, Lobato D, Hagin S, et al. Rates and predictors of oral medication adherence in pediatric patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:832–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spekhorst LM, Hummel TZ, Benninga MA, van Rheenen PF, Kindermann A. Adherence to oral maintenance treatment in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, Cook SF. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;58:519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel CA. Making therapeutic decisions in IBD: the role of patients. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chouliaras G, Margoni D, Dimakou K, Fessatou S, Panayiotou I, Roma-Giannikou E. Disease impact on the quality of life of children with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1067–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hommel KA, Davis CM, Baldassano RN. Objective versus subjective assessment of oral medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:589–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenley RN, et al. Trajectories of oral medication adherence in youth with inflammatory bowel disease. Health Psychol. 2015;34:514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenley RN, Stephens M, Doughty A, Raboin T, Kugathasan S. Barriers to adherence among adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devlen J, Beusterien K, Yen L, Ahmed A, Cheifetz AS, Moss AC. Barriers to mesalamine adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a qualitative analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20:309–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ingerski LM, Baldassano RN, Denson LA, Hommel KA. Barriers to oral medication adherence for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;35:683–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan N, Abbas AM, Bazzano LA, Koleva YN, Krousel-Wood M. Long-term oral mesalazine adherence and the risk of disease flare in ulcerative colitis: nationwide 10-year retrospective cohort from the veterans affairs healthcare system. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillespie D, et al. Electronic monitoring of medication adherence in a 1-year clinical study of 2 dosing regimens of mesalazine for adults in remission with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenley RN, Kunz JH Biank V, et al. Identifying youth nonadherence in clinical settings: data-based recommendations for children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1254–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LeLeiko NS, Lobato D, Hagin S, et al. 6-Thioguanine levels in pediatric IBD patients: adherence is more important than dose. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2652–2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plevinsky JM, Wojtowicz AA, Miller SA, Greenley RN. Longitudinal barriers to thiopurine adherence in adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019,44;52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyams JS, Davis S Mack DR, et al. Factors associated with early outcomes following standardised therapy in children with ulcerative colitis (PROTECT): a multicentre inception cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:855–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: A prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner D, Hyams J, Markowitz J, et al. Appraisal of the pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index (PUCAI). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1218–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyams JS, Davis Thomas S, Gotman N, et al. Clinical and biological predictors of response to standardised paediatric colitis therapy (PROTECT): a multicentre inception cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin T, Davison ML, Long JD. Maximum likelihood versus multiple imputation for missing data in small longitudinal samples with non-normality. Psychol Methods. 2017;22:426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kane S, Shaya F. Medication non-adherence is associated with increased medical health care costs. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53: 1020–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruemmele FM, Turner D. Differences in the management of pediatric and adult onset ulcerative colitis – lessons fro mthe joint ECCO and ESPGHAN consensus guidelines for the management of pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]