Abstract

Background:

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act was enacted to understand financial relationships with industry that might influence provider decisions. We investigated how industry payments within the congenital heart community relate to experience and reputation.

Methods:

Congenital cardiothoracic surgeons and pediatric cardiologists were identified from the Open Payments Database. All payments 2013–2017 were matched to affiliated hospitals’ US News and World Report (USNWR) rankings, Society of Thoracic Surgeons-Congenital Heart Surgery (STS-CHS) public reporting Star Ratings, and Optum Center of Excellence (COE) designation. Surgeon payments were linked to years since terminal training. Univariable analyses were conducted.

Results:

The median payment amount per surgeon ($71, IQR $41–99) was nearly double the median payment amount per cardiologist ($41, IQR $18–84, p<0.05). For surgeons, median individual payment was 56% higher to payees at USNWR Top 10 Children’s Hospitals ($100, IQR $28-$203) versus all others ($64, IQR $23-$140; p<0.001). For cardiologists, median individual payment was 26% higher to payees at USNWR Top 10 Children’s Hospitals ($73, IQR $28-$197) versus all others ($58, IQR $19-$140; p<0.001). Findings were similar across STS-CHS Star Rankings and Optum COE groups. By surgeon experience, surgeons 0–6 years post-training (first quartile) received the highest number of median payments per surgeon (17, IQR 6.5–28, p<0.001). Surgeons 21–44 years post-training (fourth quartile) received the lowest median individual payment ($51, IQR $20–132, p=0.0001).

Conclusions:

Industry payments vary by hospital reputation and provider experience. Such biases must be understood for self-governance and the delineation of conflict of interest policies that balance industry relationships with clinical innovation.

In 2010, the Physician Payments Sunshine Act (PPSA) was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act, to make publicly available data on industry payments to physicians. The primary aims of the legislation were to inform healthcare consumers, uncover potential conflicts of interests, and better understand financial relationships that might increase healthcare costs or impact care.1

Recent literature have described industry payments broadly by physician specialty.2–5 However, biases which influence the magnitude and number of industry payments remain poorly characterized, and are necessary for self-governance and the delineation of conflict-of-interest (COI) policies that balance industry relationships with clinical innovations. Further, payments within the congenital heart community, whose programs drive the revenue of many children’s hospitals,6,7 have yet to be characterized.2,3 We hypothesized that the reputation of physicians’ hospitals and individual physician experience are associated with the magnitude and number of industry payments received. Using congenital heart disease providers as an example cohort, we linked five databases to (1) describe payments to pediatric cardiologists and congenital cardiothoracic surgeons, (2) evaluate how the reputation of physicians’ hospitals relates to payments, and (3) evaluate how experience relates to payments.

Material and Methods

Sample

We included all general payments to US allopathic and osteopathic pediatric cardiologists or congenital cardiothoracic surgeons, August 1, 2013-December 31, 2017.

Data Sources and Elements

Physician Payments:

The PPSA mandates the reporting of all industry payments >$10 to physicians to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which is presented in the Open Payments Database (OPD).2–5 These data include payment amounts, type (https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/About/Natures-of-Payment), year, physician first and last name, and associated hospital city and zip code. Specific examples of payment types include service on data safety and monitoring boards, or honoraria for speaking at industry sponsored educational events. Notices of these payments are sent to receiving physicians for verification. Payments are reported across three categories: general, research, and physician ownership. For this investigation, we focused on general payments, as research payments and ownership accounted for <1% of total dollars.

Hospital Reputation:

Hospital reputation was captured from three sources, 2012–2016, one year prior to the OPD payment year: 1) U.S. News and World Report’s (USNWR) “Best Hospitals for Pediatric Cardiology & Heart Surgery” rankings, 2) the Society of Thoracic Surgeons – Congenital Heart Surgery (STS-CHS) Public Reporting Star Ratings, and 3) Optum Commercial Congenital Heart Disease Center of Excellence (COE) designation. USNWR has ranked U.S. congenital heart centers every year since 1989. We chose this source given its broad circulation and extensive use in academic medical center advertising.8 The STS-CHS is the national forum for public reporting for congenital heart surgery (https://publicreporting.sts.org/chsd?title=&field_state_value=All&order=field_overall_star_rating&sort=desc).9 It is a voluntary forum that uses 4-year mortality and patient characteristics to calculate observed and expected mortality rates. Centers with higher-than-expected mortality for case complexity mix receive one star. Centers with same-as-expected mortality receive two stars. Centers with lower-than-expected mortality receive three stars. We chose this source given its high penetrance among congenital heart surgery programs and use in public hospital reviews.10 Data were available since 2014. Optum, part of UnitedHealth Group, is a health services innovation company that uses claims data and hospital surveys to evaluate hospital subspecialty programs and to designate COE (https://cmcnetworkmanagementtool.uhc.com/clarity-fhcp/standardNetworkMap.do?isInternal=&product=CHD&population=&designation=COE&clientId=&fhcpClientName=&lobCode=COMM). While the exact criteria for congenital heart center COE designation is not public, we chose this source as it is used by ~70% of U.S. health insurance plans, making it an important driver of reimbursement in commercial markets.11 Data were available for 2017.

Surgeon Experience:

Surgeon experience was defined as years since terminal training and was derived from The Pediatric Cardiothoracic Surgeon (PCS) Masterfile. The PCS Masterfile contains linked data on >95% of U.S. congenital cardiothoracic surgeons. All data are validated manually against two separate sources to improve capture of physicians who completed training outside of the U.S. and ensure data accuracy.12 We included only surgeon experience data, as no equivalent vetted database exists for pediatric cardiologists.

Cohort Identification and Data Linkage

Physicians were initially identified in the OPD by subspecialty, including pediatric cardiology, cardiothoracic surgery, and general surgery. We included general surgeons as manual review indicated that some congenital heart surgeons were so listed. To extract congenital heart surgeons from the larger cohort, general and cardiothoracic surgeons in the OPD were fuzzy matched on first and last names against the PCS Masterfile. This methodology was used as the OPD lacks national physician identifiers. Positive fuzzy matches included matches of surgeons’ names in the OPD to full first name and first two letters of the last name in the Masterfile (3% of fuzzy-matched cohort), first two letters of first name and full last name (12%), full first name and first three letters of last name (85%). Matches were validated manually.

Hospital reputation variables were linked by associated hospital zip code and city, and payment year. Fuzzy matching was Jour used to account for hospitals utilizing multiple zip codes. Positive fuzzy matches included payments where zip codes matched exactly on first digit and full city name (84% of fuzzy-matched cohort), and where zip code matched exactly on first digit and first three letters of city (16% of fuzzy-matched cohort). We manually inspected all unmatched payments from the year with the most payments (2016); there were no false negative matches.

Data Management and Linkage Validation

Approximately 15% of payments from 2013 had no associated recipient; these were excluded. After 2013, all payments were associated with recipients.

Payment outliers were identified graphically and with kernel density analyses. Payments >$6,000 to surgeons (50 IQRs above the median) and >$10,000 to cardiologists (70 IQRs above the median) were defined as outliers. One payment of ~$27,000,000 to a single surgeon in a single year was excluded, as this was more than 200,000 IQRs above the median.

Statistical Analysis

All payments were adjusted to 2017 dollars using the U.S. medical consumer price index (https://download.bls.gov/pub/time.series/cu/cu.data.15.USMedical). Payments were described as number of payments per provider; median, interquartile range (IQR) and range of individual payments per provider; and median, IQR, and range of aggregate payments per provider. Aggregate payments per provider were defined as the sum total of all payments that each provider received over the study period.

Payments were compared by provider types (surgeons versus cardiologists) institutional rankings/public reporting status and provider characteristics. We first compared payments to physicians at any ranked or public reporting hospital versus any unranked or non-public reporting hospital, and then within each ranking methodology. We then compared payments to physicians at USNWR Top 10 hospitals versus all others, STS-CHS two or three star hospitals versus all others, and Optum COE hospitals versus non-COE. The association between surgeon experience and payments was nonlinear. Therefore, payments were categorized into quartiles by surgeon years of experience. Comparisons were conducted using Poisson regression or Kruskal-Wallis tests. P-values were adjusted using Bonferroni correction or Dunn’s test for multiple pairwise comparisons. Data were analyzed using Stata v14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). This study was approved by Columbia University Irving Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

Payment Descriptives

In total, 6,691 PPSA payments to 228 congenital cardiothoracic surgeons and 25,847 payments to 1,772 pediatric cardiologists were identified in the OPD (Table 1). The median payment amount per surgeon ($71, IQR $41–99) was nearly double the median payment amount per cardiologist ($41, IQR $18–84, p<0.05).” The median number of payments per surgeon was four times higher (13, IQR 5–31 vs. 3 IQR 1–11; p=0.0001). As a result, median aggregate payments over the study period were ten times higher per surgeon ($1,602, IQR $354–5,642) than per cardiologist ($165, IQR $45–1,343, p=0.0001).

Table 1:

Industry Payments1 to Pediatric Cardiothoracic Surgeons and Pediatric Cardiologists, August 1, 2013 to December 31, 20172

| Surgeons | Cardiologists | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of payments | 6,691 | 25,847 |

| Total number of providers | 228 | 1,772 |

| Median number of payments over 4.5 years per provider (IQR) | 13 (5–29) | 3 (1–11) |

| Aggregate payment in cohort | $1,870,180 | $9,857,154 |

| Median individual payment (IQR) | $67 (23–146) | $60 (23–164) |

| Median aggregate payment over 4.5 years per provider (IQR) | $1,602 (354–5,642) | $165 (45–1,343) |

| United States and World Report (USNWR) Rankings | ||

| Number of payments, USNWR ranked hospital (%) | 2,577 (38.5%) | 12,613 (48.8%) |

| Number of payments, USNWR unranked hospital (%) | 4,114 (61.5%) | 13,234 (51.2%) |

| Aggregate payments, USNWR ranked hospital | $694,642 | $5,640,187 |

| Aggregate payments, USNWR unranked hospital | $1,175,539 | $4,216,966 |

| Median payment, USNWR ranked hospital (IQR) | $70 (24–155) | $73 (28–197) |

| Median payment, USNWR unranked hospital (IQR) | $65 (23–139) | $52 (19–140) |

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons-Congenital Heart Surgery (STS-CHS) Star Ratings | ||

| Number of payments, STS-CHS reporting hospital (%) | 3,399 (54.5) | 15,016 (62.8) |

| Number of payments, STS-CHS non-reporting hospital (%) | 2,836 (45.5) | 8,899 (37.2) |

| Aggregate payments, STS-CHS reporting hospital | $878,612 | $6,162,843 |

| Aggregate payments, STS-CHS non-reporting hospital | $871,834 | $2,934,331 |

| Median payment, STS-CHS reporting hospital (IQR) | $69 (24–150) | $68 (27–181) |

| Median payment, STS-CHS non-reporting hospital (IQR) | $60 (22–145) | $52 (19–143) |

All payments are listed in US 2017 dollars

Data are presented as n (%), aggregate, or median (IQR)

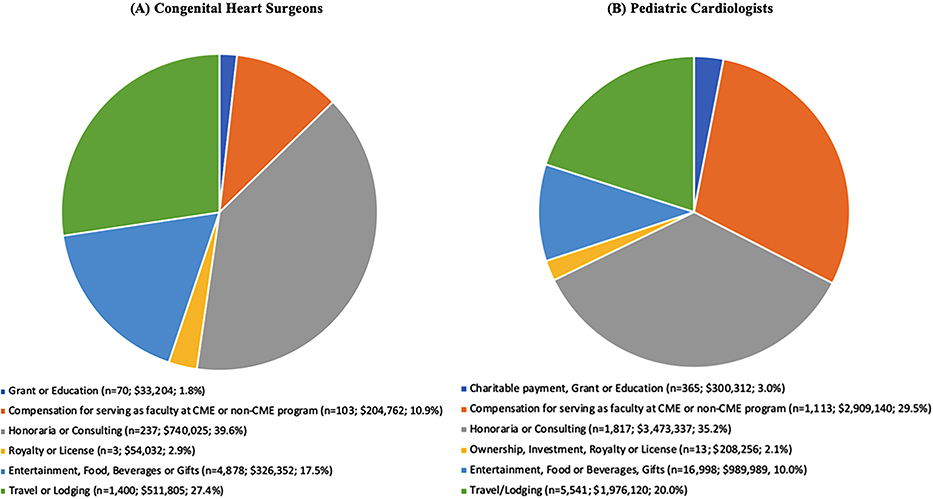

In-person gifts (food, beverage and entertainment) accounted for approximately three-quarters of the total number of payments for both surgeons and cardiologists, though these individual payments were fairly small; the median entertainment/food/beverage payment was $45 (IQR $19–107) for surgeons, and $38 (IQR $18–84) for cardiologists. (Figure 1). Consulting fees, however, accounted for the greatest proportion of absolute dollars (40% for surgeons and 35% for cardiologists), with the median consulting or honoraria payment was $2,069 (IQR $894–3,064) for surgeons, and $616 (IQR $62-$2,300) for cardiologists. For both surgeons and cardiologists, charitable payments, grants, and education payments were negligible (2% for surgeons, and 3% for cardiologists).

Figure 1:

Nature of Payments Reported to the Open Payments Database (US 2017$)

With one extreme outlier removed (see methods), payments to cardiologists were more skewed. For surgeons, 37 payments to 18 providers fell 50 IQRs above the median. For cardiologists, 70 payments to 35 providers fell 70 IQRs above the median. The largest payment per surgeon was $67,000 and per cardiologist was $123,000. The largest proportion of outliers were honoraria and consulting fees (36% for surgeons, 59% for cardiologists).

Payments by Center Reputation

United States News and World Report

Median individual payments to physicians at USNWR ranked hospitals were higher than at unranked hospitals (Table 1) and for USNWR top 10 hospitals versus all others (Table 2). Median individual payments were higher to surgeons at USNWR ranked ($70, IQR $24–155) versus unranked hospitals ($65, IQR $23–139; p=0.005) and higher for surgeons at USNWR top 10 hospitals ($100, IQR $28–203) versus those at all others ($64, IQR $23–140; p<0.001). Median individual payments were higher to cardiologists at USNWR ranked ($73, IQR $28–197) versus unranked hospitals ($52, IQR $19–140; p<0.001) and higher for cardiologists at USNWR top 10 hospitals ($76, IQR $30–183) versus those at all other hospitals ($62, IQR $22–174; p<0.0001).

Table 2:

Number of Payments and Median Individual Payment Amount by Hospital Reputation and Provider Type

| Number of payments, USNWR Top 10 (%) | Number of payments, USNWR 11+ or unranked (%) | Median payment, USNWR Top 10 (IQR) | Median payment, not USNWR 11+ or unranked (IQR) | p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Surgeons | 713 (10.7) | 5,978 (89.3) | $100 (28–203) | $64 (23–140) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiologists | 4,273 (16.5) | 21,574 (83.5) | $73 (28–197) | $58 (19–140) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Number of payments, 2 or 3 Star STS Rating (%) | Number of payments, 1 Star STS Rating or Non-Reporting (%) | Median payment, 2 or 3 Star STS Rating (IQR) | Median payment, 1 Star STS Rating or Non-Reporting (IQR) | p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Surgeons | 467 (7.5) | 5,768 (92.5) | $66 (23–146) | $63 (19–147) | 0.3 |

| Cardiologists | 3,168 (13.2) | 20,747 (86.8) | $68 (28–163) | $60 (23–166) | 0.0006 |

|

| |||||

| Number of payments, Optum Center of Excellence (%) | Number of payments, not Optum Center of Excellence (%) | Median payment, Optum Center of Excellence (IQR) | Median payment, not Optum Center of Excellence (IQR) | p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Surgeons | 304 (19.6) | 1,244 (80.4) | $99 (26–166) | $63 (23–139) | 0.0008 |

| Cardiologists | 1,810 (30.2) | 4,175 (69.8) | $76 (30–183) | $62 (22–174) | 0.0001 |

Data represent numbers (%) or medians (IQRs, interquartile ranges). Payment amounts are presented in US 2017 $.

After summing all payments for each provider, the median aggregate payment for surgeons was not different for payees at USNWR top 10 hospitals ($1,615, IQR $254–6,834) versus all others ($1,605, IQR $364–5,530; p=0.9), as the median number of payments to surgeons at top 10 hospitals was lower than for surgeons at non-top 10 hospitals (11.5 vs 15, p<0.0001). For cardiologists, the medium aggregate payment was 2.4 times higher to payees at USNWR top 10 hospitals ($364, IQR $91–2,655) versus all others ($150, IQR $42–1,073; p<0.001; Table 3), though the median number of payments to cardiologists at top 10 hospitals was not statistically different (4 vs 3, p=0.2).

Table 3:

Median Number of Payments per Provider and Median Aggregate Payments per Provider by Hospital Reputation and Provider Type

| Median number of payments per provider, USNWR Top 10 (IQR) | Median number of payments per provider, not USNWR Top 10 or unranked (IQR) | Median aggregate payments per provider, USNWR Top 10 (IQR) | Median aggregate payments per provider, not USNWR Top 10 or unranked (IQR) | p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Surgeons | 11.5 (3–35) | 15 (5–31) | $1,615 (254–6,834) | $1,605 (364–5,530) | 0.9 |

| Cardiologists | 4 (1–12) | 3 (1–11) | $364 (91–2,655) | $150 (42–1,073) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Median number of payments, two or three STS star rating (IQR) | Median number of payments, one or no STS stars (IQR) | Median aggregate payment, two or three STS stars (IQR) | Median aggregate payment, one STS star or non-reporting (IQR) | p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Surgeons | 5 (4–16) | 7.5 (3–16) | $172 (105–904) | $731 (180–3,021) | 0.07 |

| Cardiologists | 3 (1–10) | 2 (1–6) | $222 (54–1,121) | $120 (30–518) | 0.005 |

|

| |||||

| Median number of payments, Optum COE (%) | Median number of payments, not Optum COE (%) | Median aggregate payment, Optum COE (IQR) | Median aggregate payment, not Optum COE (IQR) | p-value | |

|

|

|||||

| Surgeons | 1(1–2) | 4.5 (2–8) | $125 (41–134) | $681 (126–4,115) | 0.1 |

| Cardiologists | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | $104 (22–211) | $45 (19–132) | 0.08 |

Data represent numbers (%) of medians (IQRs).

Payment amounts are presented in US 2017$.

Of the surgeon outlier payments, six payments (16%) were made to three surgeons at USNWR top 10 hospitals. Of the cardiologist outlier payments, 17 (24%) payments were made to 12 cardiologists at USNWR top 10 hospitals.

Society of Thoracic Surgery-Congenital Heart Surgery Star Ratings

For surgeons, median individual payments were higher at public reporting hospitals ($69, IQR $24–150) versus non-public reporting ($60, IQR $22–14; p=0.002, Table 1). For cardiologists, median individual payments were higher at public reporting hospitals ($68, IQR $27–181) versus non-reporting ($52, IQR $19–143; p<0.001). Within public reporting hospitals, median individual payments were not statistically different for surgeons at two or three star centers versus all others ($66, IQR $23–146 vs. ($63, IQR $19–147; p=0.2). For cardiologists, median individual payment was higher at two or three star centers ($68, IQR $28–163) versus all others ($60, IQR $23–166; p<0.001).

Median aggregate payments per surgeon were not statistically different between payees at two or three star centers ($172, IQR $105–904) versus all others ($731, IQR $180–3,021; p=0.07), as the median number of payments to surgeons at two and three star centers was lower (8 vs 6, p<0.001). Median aggregate payments per cardiologist at two or three star centers were 1.8 times ($222, IQR $54–1,121) greater than at all others ($120, IQR $30–518; p=0.005; Table 3), despite a similar median number of payments to cardiologists at two or three star centers hospitals (2 vs 2, p=0.2).

Of the surgeon outlier payments, 28 payments (76%) were made to 14 surgeons at STS two or three-star hospitals. Of the cardiologist outlier payments, 61 payments (87%) were made to 29 cardiologists at STS two or three-star hospitals.

Optum Center of Excellence

The median number of payments and the median individual payments were higher to physicians at hospitals with Optum COE designations than without. For surgeons, median individual payments were higher at COE hospitals ($99, IQR $26–166) than at non-COE hospitals ($63, IQR 23–139; p<0.001, Table 2). For cardiologists, median individual payments were higher ($76, IQR $30–183 versus $62, IQR $22–174; p<0.001).

The median aggregate payments for neither surgeons nor cardiologists were statistically different at COE versus non-COE hospitals (Table 3). Of the four surgeon outlier payments in the year 2017, one payment was made to a surgeon at an Optum COE hospital. Of the 21 cardiologist outlier payments in the year 2017, six payments were made to six cardiologists at an Optum COE hospital.

Payments by Surgeon Years of Experience

Using the third quartile of experience as reference, the median number of payments per surgeon was highest to junior surgeons 0–6 years from terminal training (17, IQR 6.5–28, p<0.0001), and lowest to senior surgeons 21–44 years from training (10, IQR 4–29, p<0.0001). The median individual payment amount was lowest for senior surgeons 21–44 years from terminal training, $51 (IQR $20–132, p=0.001). See Table 4.

Table 4:

Number of payments and median payment amounts by surgeon years since terminal training

| N surgeons (%) | Median N payments per surgeon (IQR) | P-value | Median Individual Payments (IQR) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon experience | |||||

| 0–6 years | 52 (22.8) | 17 (6.5–28) | <0.0001 | $76 (24–158) | 0.7 |

| 7–13 years | 59 (25.9) | 13 (5–35) | 0.003 | $79 (25–147) | 0.7 |

| 14–20 years | 51 (22.4) | 15 (5–31) | reference | $73 (24–149) | reference |

| 21–44 years | 61 (26.8) | 10 (4–29) | <0.0001 | $51 (20–132) | 0.0001 |

Comment

In this national study of industry payments to pediatric cardiologists and congenital heart surgeons, we found that surgeons received median aggregate payments nearly 10 times higher than cardiologists, in large part because surgeons received more than four times higher number of payments per capita. Furthermore, we found that payments were higher for physicians employed at hospitals with higher reputation scores as measured by USNWR, STS-CHSD, and Optum. Finally, we found that junior surgeons tend to receive a higher number of payments than those later in their careers, and senior surgeons tend to receive lower payment amount.

The three aims of the PPSA legislation were to help consumers make informed healthcare decisions, to uncover potential conflicts of interests, and to better understand financial relationships that might increase healthcare costs or decisions impacting care.1 Early inferential studies have shown that patients tend to be less trusting of the medical profession since the institution of PPSA,13 yet that <5% of adult patients know about their physicians’ industry relationships.14,15 Other studies have revealed inconsistent reporting of physician financial conflicts interests to hospitals; this has resulted in substantial policy changes at numerous centers.16,17

Our study revealed that congenital heart surgeons four times the median number of payments compared to pediatric cardiologists, and nearly double the median payment. There may be few fields in which surgeons and non-surgeon physicians collaborate as intimately as they do in the congenital heart community. This, therefore, raises questions as to why surgeons receive a higher median aggregate payment compared to cardiologists. Perhaps there is simply a dilutional effect, with many more cardiologists than surgeons at each center (and fewer cardiologists doing procedures that might require industry collaboration). Perhaps surgeons approach innovation or industry collaboration differently than do cardiologists, or perhaps industry approaches these subspecialists differently.

While a median payment difference of $20 between payees at USNWR top and non-top 10 hospitals may seem small, the median aggregate payments per cardiologists at USNWR top 10 hospitals were nearly 2.5 times those at non-top 10 hospitals. These findings might reflect the propensity for industry to seek collaboration and key opinion leaders from “reputable” academia—either to promote science or influence, or a reverse relationship whereby collaboration and innovation drive reputation.13,14 The latter might be a sign of industry partnership at its best, yet centers with high reputations may bear greater burden in guarding against false reciprocity. Our findings are in line with previous studies that have shown positive correlations between physician research productivity and industry payment amounts.15 To explain why the association between center reputation and aggregate payments might be more pronounced among cardiologists than among surgeons, one might hypothesize that, given the relatively small number of congenital heart surgeons, surgeons’ reputations might be more tied to themselves, and carried with them as they move from center to center, while cardiologists’ reputations might be more entwined with their hospitals of employment. The already high and increasing proportion of outlier payments going to physicians at ranked centers suggests that it is important for these centers to be particularly cognizant of potential COI. Regulations that limit the number and amount of payments for honoraria and consulting fees, which constituted the highest proportion of dollars spent for both groups, are in place at many, though not all centers. That said, the surprisingly low total dollar amounts going to the majority of congenital providers may be reassuring that most congenital heart providers are already paying attention to potential COI.

Our study was the first to describe the relationship between provider experience and payment amounts. We found that the surgeons earliest in their careers had the highest median number of payments per surgeon while the most experienced surgeons had a 33% lower median individual payment by comparison. The reason for this generational trend is unclear, and it is also unknown if it is specific to congenital heart surgeons or is more generalizable. One might hypothesize that it reflects initiative on the part of younger surgeons to collaborate with industry or the propensity of companies to more actively engage younger surgeons. The most experienced quartile of congenital heart surgeons were operating as the field was still being pioneered, inventing and perfecting procedures with broad strokes. Perhaps as these techniques have become more ubiquitous, younger surgeons have found their creative venues in devices, drugs, stem cells and tissue therapies. Or perhaps industry targets these younger providers as influencers in their field. The directionality of this relationship would be an interesting avenue for further study.

There are limitations to our study. Most importantly, the directionality of the associations we observed is unknown. Second, we assume that congenital heart surgeons and pediatric cardiologists report payments honestly; there might be data errors within the PPSA database either due to data cleaning or reporting. Third, we are unable to stratify cardiologists by their subspecialties (e.g. interventionalists, electrophysiologists, etc.). Finally, given reputation metric collinearity, multivariable analyses were not possible.

The long-term impacts of the PPSA remain unknown, and concerns have been raised regarding patient misconceptions about industry relationships16 and the potential stifling of innovation that might result.17 Indeed, the comparative lack of funding for pediatric research may mean that partnering with industry is paramount in order to provide children the same devices and drugs as their adult counterparts. Yet for all of the well-intended partnerships, one must acknowledge that PPSA legislation was born out of concern for true conflicts of interest and improper leverage of influence.1 CMS has proposed a rule for 2020 payments to include physician extenders, expanding nature of payment categories to include debt forgiveness and device loans, and including more specific device and drug identifiers. While our findings do not describe glaring conflicts of interest within the congenital heart community, they do suggest potential for biases in payment numbers and amounts. Given the necessity of industry collaboration for pediatric congenital heart disease care, it is especially important to understand these biases to strike a balance between industry leverage and scientific innovation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Congressional Record 153:S1072–3. 2007. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/crec/2007/08/02/CREC-2007-08-02-pt1-PgS10719.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parikh K, Fleischman W, Agrawal S. Industry relationships with pediatricians: findings from the Open Payments Sunshine Act. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20154440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed R, Bae S, Hicks CW, et al. Here comes the sunshine: industry’s payments to cardiothoracic surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:567–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao AH, Gangopadhyay N. Industry financial relationships in plastic surgery: analysis of the Sunshine Act Open Payments Database. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:341e–348e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez J, Ahmed R, Bae S, et al. A new culture of trans parency: industry payments to orthopedic surgeons. Ortho pedics. 2016;39:e1058–e1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banja JD. Patient Safety Ethics: How Vigilance, Mindfulness, Compliance, and Humility Can Make Healthcare Safer. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baughman KL, Crawford MH. 30th Bethesda Conference: the future of academic cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33: 1091–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad V, Goldstein JA. US News and World Report cancer hospital rankings: do they reflect measures of research productivity? PloS One. 2014;9:e107803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs JP, Mayer JE Jr, Pasquali SK, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery database: 2019 update on outcomes and quality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107: 691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.lnterlandi J. Top hospitals for congenital heart disease: what to do if your baby needs heart surgery. Consumer Reports, April 6, 2017. Available at: https://www.consumerreports.org/children-s-health/top-hospitals-for-congenital-heartdisease/. Accessed November 18, 2020.

- 11.Optum® Performance Analytics: a unified health care data and analytics platform, 2019. Available at https://www.optum.com/content/dam/optum3/optum/en/resources/brochures/opabrochure.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2020.

- 12.Anderson BR, Wallace AS, Hill KD, et al. Association of surgeon age and experience with congenital heart surgery outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Qual. 2017;10:e003533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanter GP, Carpenter D, Lehmann LS, Mello MM. US nationwide disclosure of industry payments and public trust in physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e191947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanter GP, Carpenter D, Lehmann L, Mello MM. Effect of the public disclosure of industry payments information on patients: results from a population-based natural experiment. Br Med J Open. 2019;9:e024020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young PD, Xie D, Schmidt H. Towards patient-centered conflicts of interest policy. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7: 112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ornstein CT, Thomas K. Top cancer researcher fails to disclose corporate financial ties in major research journals. New York Times; September 8, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/08/health/jose-baselga-cancer-memorial-sloankettering.html. Accessed January 13, 2020.

- 17.Ornstein CT, Thomas K. Memorial Sloan-Kettering leaders violated conflict-of-interest rules, report finds. New York Times; April 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/04/health/memorial-sloan-kettering-conflicts-.html. Accessed January 13, 2020.