Abstract

Less than 50% of patients with diabetes achieve the glycaemic goals recommended by the American Diabetes Association. The set of factors associated with adherence to treatment is very broad. Evidence suggests that psychosocial factors are related to medication adherence of patients with type 2 diabetes. Due to the lack of a clear statement from researchers regarding the relationship of psychosocial factors to adherence, an electronic search was conducted in PubMed, MEDLINE, Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL Complete, Edition and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition using the following keywords “adherence”, “diabetes”, “social support”, “stress”, “anxiety and depression”, “beliefs about medicine”, “communication”, “older age”, “frailty”, “cognitive impairment”, “addiction”, “acceptance of illness”, “sense of coherence” obtaining 2758 results. After a narrowing of searches and reference scanning, 36 studies were qualified. The studies analysed showed negative effects of anxiety, diabetes distress, older age, poor communication with physicians, stress, concerns about medicines and cognitive impairment on levels of self-care and medication adherence. One study did not confirm the association of depression with adherence. Self-efficacy, social and family support, and acceptance of illness had a beneficial effect on medication adherence. In conclusion, the current evidence suggests that the relationship between psychosocial factors and adherence has reliable scientific support.

Keywords: medication adherence, behaviour, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

The incidence of diabetes mellitus is rising year on year, especially in low- and middle-income countries.1 Around 422 million people globally, and 60 million in Europe, have diabetes.1 Type 2 diabetes accounts for 90% of all these cases, and is considered a major lifestyle disease.1 In 2017, there were approx. 462 million type 2 diabetes patients worldwide, representing 6.28% of the global population.2 Diabetes will be the seventh most common cause of death by the year 2030, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).3

Type 2 diabetes treatment is based on glycemia normalization and prevention of complications.4 This can be achieved through lifestyle changes, administration of oral hypoglycemic drugs and/or insulin injections, and self-care.5 Strict metabolic control and self-care ability can improve diabetes treatment outcomes and considerably reduce the risk of complications.6 Active participation in the treatment process helps patients consciously manage their health. Attaining normal blood glucose levels is only possible when patients adhere to the treatment recommendations.7 Patient cooperation with healthcare professionals, or compliance, plays a major role in type 2 diabetes treatment. Better adherence to treatment favors better control of diabetes and contributes to the prevention of both early (hypo- and hyperglycemia) and long-term complications (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, angiopathy, diabetic foot syndrome).8

The literature data indicate that as few as 50% of patients undergoing chronic treatment adhere to the prescribed protocol in the first year of treatment.9 In the polish diabetic group, only 65.1% adhere to the prescribed treatment, and less than half fully adhere to the recommendations for self-monitoring of blood glucose based on the guidelines of the American Diabetes Association.10 Non-adherence to diabetes treatment may involve diet, exercise, lifestyle, substance use, medication, follow-up visits, and self-monitoring. The literature describes various forms of non-adherence.11,12 It may be intentional (when the patient deliberately decides to discontinue treatment), unintentional (due eg to forgetfulness) or a combination of both.1,13 Unintentional non-adherence typically involves missing individual doses of medication, while intentional non-adherence may consist in delaying or skipping doses, and in extreme cases, completely discontinuing treatment.14 Non-adherence to treatment often results in a deterioration of health and entails significant negative economic effects due to higher treatment costs resulting from rehospitalizations, absence from work, long-term treatment of increasingly severe complications, and ultimately death.15 Therefore, according to the WHO, improvements in the effectiveness of interventions to promote adherence may have a much greater impact on population health than advances in treatment.9 A better understanding of mechanisms behind non-adherence is thus required.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

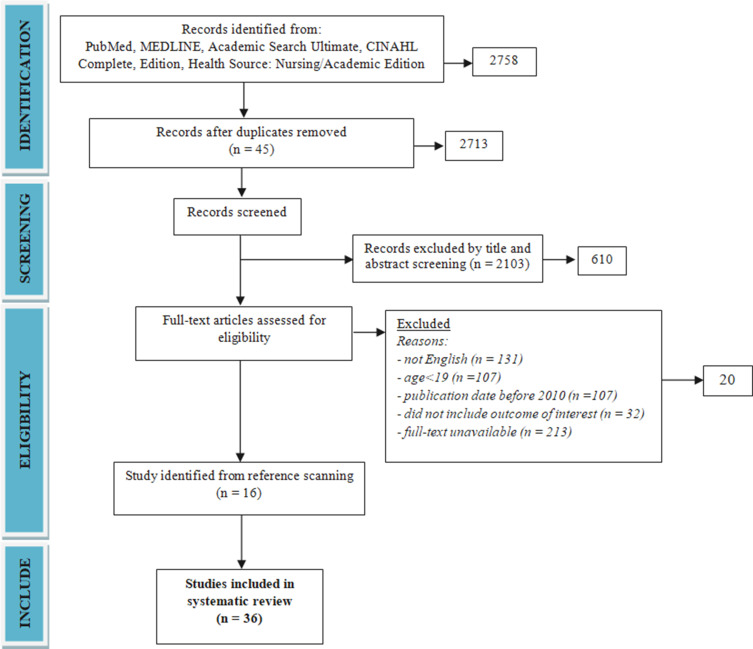

Systematic searches using the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews guidelines (PRISMA) to identify studies that reported the association between psychosocial factors (social support, stress, anxiety, depression, beliefs about medicines, satisfaction with physician-patient communication, frailty syndrome, cognitive impairment, addiction, acceptance of illness, sense of coherence) and adherence were performed.16 Electronic searches were performed (from 2010 to 2021) of PubMed, MEDLINE, Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL Complete, Edition and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition using the following keywords (adherence or compliance or nonadherence or noncompliance or treatment adherence or treatment compliance) AND diabetes AND (social support OR stress OR anxiety and depression OR beliefs about medicine OR communication OR older age OR frailty OR cognitive impairment OR addiction OR acceptance of illness OR sense of coherence) obtaining 2758 results.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Papers were included if they examined the relationship between psychological factors (social support, stress, anxiety, depression, beliefs about medicines, satisfaction with physician-patient communication, frailty syndrome, cognitive impairment, addiction, acceptance of illness, sense of coherence) and adherence. Papers were excluded if the full paper was not available, other reviews, case reports or no assessment of psychological factors using a standardized questionnaire.

A total 20 potential studies were identified after removal of duplicates, review articles, meta-analysis, after narrowing the criteria to papers in English with adult participation published between 2011 and 2021 (Figure 1, Table 1).17–21,26–31,39–42,45–48 A further 16 study were identified through reference searches.22–25,32–38,43,44,49–52 No studies were found on the association of frailty syndrome and addiction with adherence of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Note: Own elaboration based on the data obtained in the study.

Table 1.

Summary of the Qualified Studies

| No | Author and Year | Study Design | Study Group | Psychosocial Factors Affecting Adherence to Diabetes Treatment | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rao D et al, 202017 | A longitudinal study | 287 black adult patients with T2DM (56.3% male) aged 52.6±12.03 | Physician communication, beliefs about medicines, self-efficacy, depression, illness perception | - Small sample size - No regression models to assess predictors of adherence |

| 2 | Saffari M et al, 201918 | A longitudinal study | 793 patients with T2DM (55.0% male) aged 70.21± 15.10 years. | Social support, religiosity, religious coping | - Social support and religious coping were context-based - No assessment of other factors associated with religiosity, (locus of control, spiritual coping, and self-efficacy) |

| 3 | Adisa R et al, 201719 | A prospective cross-sectional study | 200 patients with T2DM aged 63.7 ± 12.4 years | Access to family support, monthly income, medicine affordability | - Self-report measure (risk of bias)- No assessment of availability and influence of structural support (knowledge and attitudinal barriers on outcome) - A cross-sectional study design |

| 4 | Smalls BL et al, 201520 | A cross-sectional study | 615 adults with T2DM (61.6% male), 53.6% in aged 45–64 years, 53.6 non-Hispanic Black | Social support, social cohension, comorbidities, age 65+, hispanic race, health insurance – medicaid, being employed, food insecurity | - A convenience sample from only the southeastern United States - A cross-sectional study design |

| 5 | Tiv et al, 201221 | A cross-sectional study | 3637 patients with T2DM aged 65.0 ±11.1 years (54.4% male) | Family and social support, age 65–84 years, professional activity, financial difficulties, presence of microvascular or macrovascular complications, | - Use of self-report data on medication adherence -Cross sectional study |

| 6 | Osborn CY and Egede LE, 201222 | A cross-sectional study | 139 patients with T2DM in mean age 62.7 ±11.9 years (71.9% male), 41.4% African American | Social support, depressive symptoms | - No subgroups analysis (gender, race/ethnicity, health literacy status) - The PHQ-9 used to quantify depressive symptoms (other studies have shown that the tool overestimates the prevalence of major depression in samples of people with diabetes and other comorbidities) - A cross-sectional study design |

| 7 | Bouldin ED et al, 201723 | A cross-sectional study | 253 adults age 30–70 with poorly controlled diabetes (45% white, 25% black, and 43% Hispanic) | Caregiver support | - Risk of bias (social desirability) - Using broad definition of having acaregiver (periodic or minimal assistance) -No information about how long the caregiver had provided assistance, what types of support the caregiver provided, the quality of care, or the caregiver’s confidence in promoting self-care - Small number of patients with caregiver - A cross-sectional study design |

| 8 | Song Y et al, 201324 | A descriptive observational study | 83 Korean Americans with T2DM in mean age 56.5 ± 7.9 years (57.8% male). | Unmet needs for social support, self-efficacy, age | - Study was conducted on a relatively small and homogeneous sample from one ethnic minority group -Social support assessed by measuring the patients’ perceptions |

| 9 | Watkins YJ et al, 201325 | A cross-sectional study | 132 African American adults with T2DM (male 33%), in mean age 52.2±12.8 | Spirituality, religion, age, gender, income | -Study focused on African American adults -Self-reported data -No consideration of religious affiliations and associations and the impact they have on health behaviors (smoking, alcohol) - A cross-sectional study design |

| 10 | Anderson JR et al, 201626 | An observational study | 117 couples in which one partner was diagnosed with T2DM (male patients 57.3%), mean age of patients 57.44 ± 9.83 years | Dietary adherence: diabetes stress, depressive symptoms Exercise adherence: comorbidities, T2DM duration, depressive symptoms |

-The sample was fairly homogenous with respect to race/ethnicity, education, and geographic location-self-report measures |

| 11 | Bell RA et al, 201027 | A cross-sectional study | 696 patients with T2DM divided into 2 groups: with depression (n=586, aged 74.1 ± 5.3 years, 64.6% male) and without depression (n=110, aged 74.1 ± 5.9 years, 35.4% male) | Depression | -A cross-sectional study -Self-report measures |

| 12 | Zhang Y et al, 201528 | A cross-sectional study | 2538 patients with T2DM (53% male) aged 56.4 ± 10.5 years | Depression | - Patients from metropolitan hospital-based clinics only - No assessment of marital status and income which might have prognostic significance for depression -The PHQ-9 used to quantify depressive symptoms - No formal psychiatric examination to confirm a diagnosis of major depression |

| 13 | Carper MM et al, 201429 | A cross-sectional study | 146 patients with T2DM (57.5% male) aged 56.01 ± 9.28 years | Depression, diabetes distress, quality of life (domains: personal relationships, environmental, achievement, psychosocial growth) | - The ratio of participants to measure items (9:1) - High levels of depression severity and diabetes distress of patients - A cross-sectional study design - recruited primarily non-Hispanic White limiting generalizability of the findings to other racial/ethnic groups |

| 14 | Sweileh WM et al, 201430 | A cross-sectional study | 294 patients with T2DM (44.2% male), 73.5% ≤65 years, | Depression | - A cross-sectional study design -Self-report measures - No multivariate analysis of factors associated with adherence |

| 15 | Zuberi SI et al, 201131 | A cross-sectional study | 286 patients with T2DM (44.8% male) aged 31–60 years | Depression | - A cross-sectional study design - No assessment of educational status and household income - Self-report measures |

| 16 | Derakhshan Shahrabad H et al, 201832 | A prospective observational cohort study | 24 females with T2DM (aged 20–40 years) divided into 2 groups: control (n=12) and experimental (n=12) Intervention:12 weeks Lazarus multimodal psychotherapy |

Depression, anxiety | -No adherence assessment - No formal psychiatric examination to confirm a diagnosis of depression -Self-reported data - No multivariate analysis of factors associated with adherence |

| 17 | Ciebiada M et al, 201733 | An observational study | 55 patients with T2DM (34.5% male) aged 73.7 ± 4.4 years | Depression | - No standardised tool to assess adherence - No formal psychiatric examination to confirm a diagnosis of depression -Self-reported data - No multivariate analysis of factors associated with adherence |

| 18 | Górska-Ciebiada M et al, 201734 | An observational study | 82 patients with T2DM and depressive syndrome aged >65 years | Depression | -A single-centre study with a small sample size - Self-reported data - No standardised tool to assess adherence |

| 19 | Akpalu J et al, 201835 | A cross-sectional study | 400 patients with T2DM (21.5% male) aged 52.7 ± 8.7 years | - | - A cross-sectional study design - Patients were selected from a specialized tertiary hospital in urban Ghana - No standardised tool to assess adherence |

| 20 | Linetzky B et al, 201736 | A multinational prospective observational cohort study | 4341 patients with T2DM in mean age 61.77 ± 11.02 years (50% male) | Diabetes duration, high country income, private insurance status, insulin treatment regimen, communication, diabetes-related distress | - A cross-sectional study design - No standardised tool to assess adherence -Self-reported data |

| 21 | Ratanawongsa N et al, 201337 | A cross-sectional study | 9377 patients with T2DM in mean age 59.5±9.8 years (48.3% male) | Communication | - A cross-sectional study design - Risk of recall bias - Only CMG use to assess adherence and does not evaluate early stages of adherence for newly prescribed medications (primary nonadherence) - Limited pharmacy data on insulin use by patients |

| 22 | Kirkman MS et al, 201538 | An observational study | 218,384 patients with T2DM (47% male) aged 64.9±4.8 years | TYPE of therapy (new or continuing), age, gender, education, income, geographic region, prescriber specialization, prescription factors (pill burden, prescription drug channel, out of pocket costs) | - No race/ethnicity data - No primary nonadherence (not filling an initial prescription for a medication) assessment - MPR measures only refill behavior and not actual medication taking |

| 23 | Xie Z et al, 202039 | A secondary data analysis of a 24-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) | 148 patients with T2DM and hypertension (59.5% male), 52.7% aged ≥64 years | Perceived health status, self-efficacy, older age, gender, living status, diabetes duration | - Self-reported data |

| 24 | Mutyambizi C et al, 202040 | A cross-sectional study | 396 patients with T2DM aged 41–60 years (39% male), 35% were African | Older age, being non-African, gender, professional activity, marital status, education | - A cross-sectional study design - The risk of social desirability bias during the face-to-face interviews - Data collected in two hospitals |

| 25 | Alfian SD et al, 201941 | An observational retrospective inception cohort study | 6669 patients with T2DM (55.1% Male) aged 63.2+11.3 years | Older age, type of prevention, the prescription of diuretics, beta-blocking agents or calcium channel blockers as initial drug class, gender | - Assessment of non-adherence and non-persistence based on drug dispensing (risk of underestimate true rates, because of not taking all the drugs collected at the pharmacy) - Coexisting hypertension |

| 26 | Mahfouz EM and Awadalla HI, 201142 | A cross-sectional analytic study | 206 patients with T2DM (39.8% of male) aged 54±6.3 years | Self-monitoring: older age, education dietary adherence: occupation, duration of diabetes |

- A cross-sectional study design - Self-reported data |

| 27 | Mendes R et al, 201943 | A cross-sectional study | 94 patients with T2DM in mean age of 75.2 ±6.7 years (46.8% male) | Anxiety, insulin use | - A cross-sectional study design - Self-reported data |

| 28 | Akturk U et al, 201844 | A descriptive observational study | 264 patients with T2DM aged 52.33±14.6 years (39.4% male) | Education level, acceptance of illness, professional activity, income, support for care, smoking, comorbidities | - Recruited only the patients registered in the Başharık Family Health Center - Self-reported data |

| 29 | Alyami M et al, 201945 | An observational study | 115 Muslim Saudi nationals patients with T2DM, in mean age 56±12.43 years (58% male) | Age, sense of coherence, illness perception – consequences and illness identity | - Participants were recruited from a single diabetes outpatient clinic using convenience sampling - Self-reported data |

| 30 | Özkaptan BB et al, 201946 | A cross-sectional, descriptive study | 200 patients with T2DM in mean age 53.87 ± 11.3 years (37.5% male) | Age, BMI, HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, postprandial blood glucose, acceptance of illness | - A cross-sectional study design - Self-reported data - No analysis of the correlation between acceptance of illness and adherence |

| 31 | Can S et al, 202047 | A cross-sectional, study | 133 patients with T2DM in mean age 57.3±11.7 years (37.6% male) | Acceptance of illness in domain diet, exercise, foot care and total | - A cross-sectional study design - Self-reported data - No analysis of the correlation between acceptance of illness and adherence - No standardised tool to assess adherence |

| 32 | Dhippayom T and Krass I, 201548 | An observational cross-sectional study | 543 T2DM patients (57.6% male) aged 63.0 ± 10.6 years | Age, knowledge of diabetes and treatment, beliefs about medicines - specific-concern, reported having difficulty in paying for medication, insulin use, polypharmacy | - A cross-sectional study design - Self-reported data |

| 33 | Graça Pereira M et al, 201949 | An cross-sectional study | 387 Caucasian patients diagnosed with T2DM (58.1% male) in mean age 59.2 years | Bieliefs about medicines (needs), illness perception (concerns, consequences, personal control, treatment control, emotional response) | - A cross-sectional study design - Self-reported data |

| 34 | Yoel U et al, 201350 | An observational cohort study | 101 low adherent Bedouin patients with diabetes, hypertension and lipid metabolic disorder aged 49.7 ± 12.0 years (51.5% male) and 99 high adherent patients aged 55.3 ± 12.4 years (36.4% male) | Beliefs about medicines | - Coexisting lipid metabolic disorder and hypertension - Questions about the clinic team were asked to patients at the clinic - Self-reported data - Study focused only on Bedouin - No multivariate analysis of factors associated with adherence |

| 35 | Rosland AM et al, 201551 | A community-based participatory study | 108 patients with T2DM divided into 2 groups: intervention (n=56, 25% male, aged 50.2 ±10.2 years) and control (n=52, 32.7% male, aged 56.4 ±12.3 years) Intervention: The six-month intervention included CHW-delivered group diabetes management classes, home visits and accompaniment to physician appointments to model activated participation |

Family and friends support, CHW support | - A cross-sectional study design - Study participants were low-income, racial/ethnic minority adults - Assessment of only one type of diabetes social support(positive support from family and friends) - Self-reported data - No standardised tool to assess adherence |

| 36 | Rosland AM et al, 201452 | An cross-sectional study | 13,366 patients with T2DM (51% male) aged 59±10 years | Healthful eating and physical activity: social support, emotional support | - A cross-sectional study design - Self-reported data - Analysis of 18 multivariable models and risk of one or more false positive findings |

Abbreviations: T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; CHW, community-based health worker; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; MPR, Medication Possession Ratio; CMG, Continuous Measure of Medication Gaps.

Results

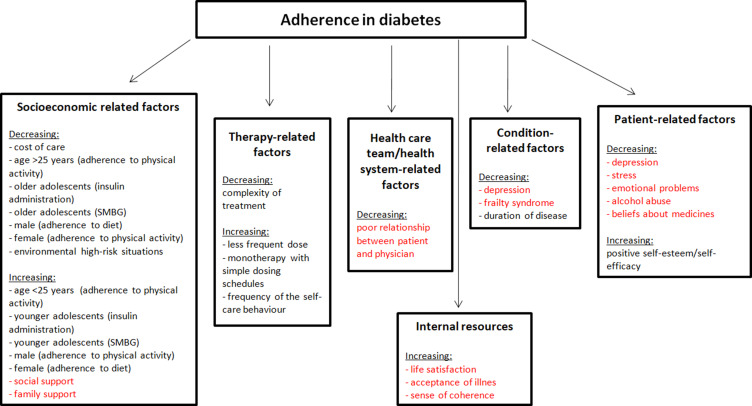

The WHO has identified five groups of factors influencing adherence to treatment in chronic disease: socio-economic factors, health care system-related factors, illness-related factors, treatment-related factors, and patient-dependent factors (Figure 2).53 The importance of other factors, such as acceptance of illness44,46,47 and beliefs about medicines,17,48–50 not included in the initial classification by the WHO has also been recognized since. Psychological or social problems may impair the patients’ self-control and their ability to participate actively in their treatment process.54 Some psychosocial factors can, however, be successfully modified to improve patients’ outcomes.

Figure 2.

Factors influencing adherence to treatment recommendations by patients with diabetes according to WHO modified by own elaboration.

Note: Figure based on data from World Health Organization53 and supplemented with psychosocial factors not included in the WHO report.

Factors Affecting Adherence to Diabetes Treatment

Social and Family Support

The direct impact of social support on the health of an individual has been confirmed in a number of studies.18–24,44,51,52 The absence of social support is a limiting factor in adherence to treatment among patients with type 2 diabetes.24 According to Osborn and Egede, more depressive symptoms have an indirect effect on medication non-adherence through the lack of social support, but social support explains the direct effect of depression on medication non-adherence.22 Tiv et al observed the influence of several psychosocial variables on the level of adherence of elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Independent determinants of elderly patients’ adherence included lack of family or social support (OR = 2.5) and need for medical support (OR= 1.6).21 In the Smalls et al study, received social support was a predictor of adherence to diet (β = 0.016), medication (β = 0.009) and foot care (β = 0.010).20 Social support can help one cope with their diabetes, improve patients’ belief in their own efficacy and ability to implement the recommended self-care behaviors, and eliminate barriers to effective diabetes treatment.23 According to Adis et al, the family source of support is the most accessible, but government and non-government organization support was largely desirable. However, mean systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients and fasting glucose levels in T2D patients with access to family and financial support were better than those without any type of support (p>0.05).19 Providing social support to patients with diabetes and concurrent depression helps ameliorate some of the deleterious effects of depressive symptoms on medication non-adherence, but social support alone is not enough.22 In the study by Bouldin et al, patients with type 2 diabetes who had a caregiver were less likely than those without a caregiver to report that they had missed their diabetes medication in the preceding two weeks (31% vs 44%, p=0.04), reduced their medication intake because they felt worse (13% vs 23%, p=0.04) or stopped taking their medication because they felt their glycemia was under control (12% vs 23%, p=0.02).23 Akturk, and Aydinalp estimated that 61.4% of patients with type 2 diabetes did not take support for care, 39.2% of those who took support, took it from their spouses and children.44 Patients receiving support had significantly higher levels of diabetes self-efficacy compared to patients who did not experience social support (50.33±15.3 vs 52.83±15.3).44 The study by Rosland et al demonstrated a positive association between social support and improved health behaviors (exercise, diet), but not adherence to pharmaceutical treatment.52 The difference may be due to the fact that patients with uncontrolled diabetes may require additional support to make significant lifestyle changes, but diabetes-specific care and support may be a way for them to change their daily medicine-related behaviors.23 The study by Rosland et al included 108 diabetes patients. Those in the intervention group received support in the form of community health worker-delivered group diabetes management classes, home visits, and physician appointments.51 These interventions did not increase the level of social support, but the intervention group had significantly improved glycated hemoglobin levels after 6 months (mean change –1.0%, p=<0.01). In addition, the baseline social support level was a significant predictor of HbA1c change (coefficient: –0.39, p=0.02). In the study by Watkins et al, social support was an independent determinant of adherence to diet and foot self-care.25

Stress and Diabetes Distress

Reactions to external stressors can lead to difficulties in adhering to therapeutic recommendations, and more specifically, to non-adherence to diet or difficulties in medication taking. Research suggests that non-adherence may be associated with emotional distress and poor diabetes treatment outcomes.26,36 Anderson et al found that patient and spouse stressors, particularly diabetes-related stress and the number of comorbidities in the patient, were found to be associated with the patient’s adherence to diet and exercise.26 Furthermore, spouse diabetes-related stress (b = −0.40, p<0.001) and comorbidities (b = 0.17, p = 0.038) and patient comorbidities (b = −0.31, p<0.001) and depressive symptoms (b = −0.48, p<0.001) were significantly associated with spouse self-efficacy.26 Similarly, in the study of Linetzky et al poor insulin adherence was associated with a 0.43% increase in HbA1c and greater diabetes-related distress ([aOR] 1.14; 95% CI 1.06–1.22), higher Discrimination (aOR 1.13; 95% CI 1.02–1.27) and Hurried Communication (aOR 1.35; 95% CI 1.20–1.53) scores, and a lower Explained Results score (aOR 0.86; 95% CI 0.77–0.97) of IPC (the Interpersonal Processes of Care).36

Anxiety and Depression

The co-occurrence of diabetes and depression is associated with adverse diabetes outcomes. The relationship between diabetes and depression is bidirectional. The literature features conflicting reports on the impact of anxiety and depression on adherence to treatment in diabetes patients.17,22,26–35,43 However, several studies do confirm the association between depressive disorders and non-adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes.17,22,26–34,43 Patients with type 2 diabetes and comorbid depression have lower adherence to treatment compared to non-depressed patients.17,22,26,28,30,43 Zuberi et al showed that depression was also associated with low adherence to self-care activities, such as taking doses as prescribed (OR = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.14–0.73), dietary restrictions (OR = 0.45; 95% CI = 0.26–0.79) and foot care (OR = 0.38; 95% CI = 0.18–0.83).31 Shahrabad et al demonstrated the impact of Lazarus multimodal psychotherapy on the alleviation of depression symptoms and reduction of blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes.32 Their findings support the notion that psychotherapy can be effective in reducing anxiety, depression, and physical symptoms in patients with diabetes.32 In the Zhang et al study, depressed patients had higher glycated haemoglobin values (7.9 ± 2.0 vs 7.7 ± 2.0%, P = 0.008) and were less likely to achieve a target HbA1c <7.0% (36.2% vs 45.6%, P = 0.004) than non-depressed patients.28 These patients were more likely to report hypoglycaemia and less likely to adhere to recommended diet, exercise, foot care and medication.28 However, the association between depression and glycaemic control became non-significant after accounting for adherence to diet, exercise and medication (OR = 1.48, 95% CI 0.99–2.21, P = 0.058).28 In the study by Ciebiada et al, 75% of patients with depression reported having omitted a planned medication dose, 70% did not take their medication at regular times, 45% omitted subsequent doses when they felt well, and 50% omitted the next dose when they felt bad.29 Poor adherence was found in 50% of patients with depressive symptoms and in 2.8% of those with no symptoms of depression.33 In Górska-Ciebiada and Ciebiada, patients with depression and poor metabolic control had a significantly poorer adherence to diet (66.7% vs 25%, p<0.05), lower exercise levels (64.8% vs 28.5%, p<0.05), and more visits to their physician in a year (3.31±1.04 vs 2.71±1.21, p<0.05) than those with no depression.34 In turn, the study by Akpalu et al of a group of 400 patients with type 2 diabetes aged 52.7±8.7 was among the few that did not confirm an association between depression and metabolic control in diabetes.35 Patients with diabetes and depression are less likely to adhere to self-monitoring, which increases the risk of diabetes complications.22,27 In a study by Bell et al of 696 older African Americans, American Indians and whites, high levels of depression were associated with lower adherence to dietary and physical activity recommendations and more frequent foot checks.27 A surprising result of the Bell study was better foot care of patients with depression.27 The authors of the study exclude ethnic differences and explain that depressed patients are more likely to visit doctors they are prompted to check during these visits.27

Beliefs About Medication and Therapy

Beliefs about therapy are an important factor in its success. These beliefs may relate to the necessity of taking medication, the harm of medication, medication overuse, and concerns about medication.17,48–50 In literature, particular attention is paid to beliefs about treatment in elderly patients affected by multimorbidity and polypharmacy. In the study by Dhippayom and Krass pharmacological adherence in a sample of the Australian T2D patient population was suboptimal (64.6%).48 However, 53.6% of respondents expressed concerns about taking medication. Age (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.19–2.82), medication concerns (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87–0.96), diabetes knowledge (OR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73–0.99), difficulty paying for medication (OR, 0.51; 95% CI,0.33–0.79), having more than one medicines (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.36–0.95) and insulin use (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.30–0.81) were a potential predictor of adherence.48 Elderly patients may have strong beliefs regarding their medication, often based on their own experience or that of their family members.50 This patient group is at more risk of adverse reactions to medication, while patients themselves may have habits of medication abuse or preconceived ideas about the lack of benefit or even harm from the prescribed medication.50 In a study by Graça Pereira et al on a group of 382 patients with type 2 diabetes, greater concerns about the diabetes, weaker general beliefs about medicines, and stronger needs about medicines were associated with higher levels of adherence to treatment.49 In turn, Yoel et al confirmed the impact of adverse effects of the prescribed medication on adherence.50 Patients with poorer adherence reported that the adverse effects from the prescribed medication were worse than their disease symptoms (65 vs 47%), which represented the main reason for discontinuation of treatment in nearly half of the patients studied. In the Rao et al, study involving Blacks with type 2 diabetes mellitus increased adherence was significantly correlated with lower medication concerns (r = −0.31), higher self-efficacy (r = 0.47), lower depressive symptoms (r = −0.26) and lower negative illness perception (r = −0.26) at both baseline and after 6-month follow-up.17

Satisfaction with Physician–Patient Communication

Communication between the medical staff and the patient has a significant impact on the latter’s attitude toward their illness. Multiple studies have demonstrated widespread dissatisfaction among patients regarding their communication with medical personnel.36,37 Most patients were dissatisfied with the information they received concerning their health and the treatment they were undergoing. A large percentage of patients were unhappy about having insufficient opportunities to talk about their problems. In the study by Linetzky et al,36 patients with type 2 diabetes who were concerned about their disease and dissatisfied with their communication with physicians had a low level of adherence to recommendations regarding insulin administration.

Patient-centered communication can favor collaborative decisions about the treatment. The patient’s active attitude, combined with patient-centered communication, can provide the physician with information on the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed treatment, as perceived by the patient. Ratanawongsa et al reported that a lower level of adherence to refills was associated with such physician characteristics as poor ability to involve patients in decisions, a lack of understanding for patients’ problems with the treatment, and failure to elicit trust and confidence.37 In the study by Ratanawongsa et al, patients who scored their providers lower in terms of involving patients in decisions, understanding patients’ problems with treatment, and eliciting confidence and trust, had significantly lower adherence levels. In addition, low ratings for understanding problems with treatment, putting the patient’s needs first and trust were associated with poor adherence to oral hypoglycemic medications.37

Elderly Age and Cognitive Impairment

There is an ongoing debate in the literature on the impact of older age on adherence. Evidence from previous studies regarding relationships between adherence and age is conflicting. There are studies confirming the positive effect of older age on adherence to treatment recommendations,21,24,25,39,45,48 but there is also evidence that elderly patients have poorer levels of adherence compared to younger patients.40–42,46 In a group of 218,384 patients with type 2 diabetes studied by Kirkman et al, those aged 75 years and above were 41% more likely to be adherent when compared with the 45–64 age group.38

Though the correlation between age and adherence to treatment has been confirmed, researchers also highlight the role of additional factors affecting adherence in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Elderly diabetic patients are significantly more likely to have dementia and mild cognitive impairment compared with similarly aged non-diabetics.55 Impaired cognitive abilities may cause patients to neglect self-control or treatment-related behaviors altogether or selectively forgo more complex tasks, leading to deficits in glycemic control.43 In a study by Mendes et al, patients with cognitive impairment demonstrated low levels of adherence to exercise. However, no association between cognitive function and adherence to diet or pharmaceutical treatment was confirmed.43

Acceptance of Illness and Sense of Coherence

Evidence of any association between illness acceptance and adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes remains scarce. Patient with diabetes demonstrate a moderate level of illness acceptance.44–47 The Akturk and Aydinalp study confirms the positive relationship between diabetes acceptance and self-efficacy of patients with moderate level of disease acceptance and self-efficacy.44 A study by Özkaptan et al involving patients characterised by low illness acceptance, found that there was a significant and negative relationship between the patients’ illness acceptance and treatment adherence (−0.78).46 Alyami et al confirmed a positive association between illness acceptance, sense of coherence and adherence to treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes.45 Multivariable logistic regression revealed that older age (OR=3.76, p=0.023), worse consequences perceptions (OR=0.21, p=0.011), worse illness identity (OR=0.23, p=0.010), and greater illness coherence (OR=3.24, p=0.022) were independent predictors of adherence of Saudi patients with type 2 diabetes.45 Similarly, Can et al found a statistically significant positive correlation between disease acceptance and adherence to diet, foot care and exercise.47

Conclusions

Routine assessment of psychosocial predictors of medication non-adherence will allow the identification of patients at risk of therapeutic failure.

Behavioral interventions focused on reducing stress and depression, increasing the sense of self-efficacy and involvement in the therapeutic process should be an important element of diabetes therapy.

Implications for Practice

The above review shows that the set of factors associated with adherence to treatment is very broad. Some of these factors are well-understood, while others require further investigation. With each study on adherence, additional causes are found, calling for the identification of a variety of underlying factors. The importance of these factors may vary between different patient groups. To identify factors affecting adherence, an individualized approach is necessary. The problem of patients’ poor adherence to therapeutic recommendations in long-term treatment requires special interventions. Daily medical practice should include continuous evaluation of adherence to diabetes treatment, and the reasons behind the identified levels of adherence must be properly understood. Patients need information to understand the nature of their illness and the importance of adherence to treatment. Each visit should be accompanied by counseling in order to improve adherence to treatment and the patient’s perception of the illness. Healthcare providers need to focus on patients’ behaviors that may interfere with adherence to treatment in order to achieve control of diabetes in the community. Healthcare professionals should identify potential viable strategies for increasing adherence in their daily practice, for example simplifying regimen characteristics, modifying patient beliefs, imparting knowledge, patient communication, assessment of social support and family involvement in treatment and evaluating adherence, anticipating and precluding interruption in adherence, assurance against harm due to drug side effects.56,57 Patient groups at a particularly high risk of non-adherence should also be selected in clinical practice. Better understanding of underlying mechanisms and introduction of corrective actions in the form of educational interventions will result in better glycemic control, prevention of early and late complications, and potential economic benefits for the health care system.

Acknowledgments

All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/909883/retrieve. Accessed March25, 2021.

- 2.Khan MAB, Hashim MJ, King JK, et al. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes – global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2019;10(1):107–111. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.191028.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Diabetes. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/. Accessed January28, 2021.

- 4.McKenzie AL, Athinarayanan SJ, McCue JJ, et al. Type 2 diabetes prevention focused on normalization of glycemia: a Two-Year Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):749. doi: 10.3390/nu13030749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. 1. Improving care and promoting health in populations: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Supplement1):S7–S14. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehravar F, Mansournia MA, Holakouie-Naieni K, et al. Associations between diabetes self-management and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016004. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2016004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel S, Abreu M, Tumyan A, et al. Effect of medication adherence on clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes: analysis of the SIMPLE study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2019;7(1):e000761. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association. Implications of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl1):28–32. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosworth HB, Fortmann SP, Kuntz J, et al. Recommendations for providers on person-centered approaches to assess and improve medication adherence. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):93–100. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3851-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rokicka D, Wróbel M, Szymorska-Kajanek A, et al. Assessment of compliance to self monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetic patients and level of implementation of Polish Diabetes Association recommendation for general practitioners — results of multicenter, prospective educational health programme — DIABCON study. Clin Diabetol. 2018;7(3):129–135. doi: 10.5603/DK.2018.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koech C, Nguka G, Oloo PAJ. Factors affecting treatment compliance among type 2 diabetes patients on follow-up at Moi Teaching & Referral Hospital. J Heal Med Nurs. 2019;4(5):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mugo IM. Compliance to Recommended Dietary Practices Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Attending Selected Hospitals in Nakuru County. Kenyatta Univ; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molloy GJ, Messerli-Bürgy N, Hutton G, et al. Intentional and unintentional non-adherence to medications following an acute coronary syndrome: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(5):430–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clifford S, Barber N, Horne R. Understanding different beliefs held by adherers, unintentional nonadherers, and intentional nonadherers: application of the necessity–concerns frarnework. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leporini C, De Sarro G, Russo E. Adherence to therapy and adverse drug reactions: is there a link? Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):41–55. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.947260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao D, Maurer M, Meyer J, et al. Medication adherence changes in blacks with diabetes: a Mixed Methods Study. Am J Health Behav. 2020;44(2):257–270. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.44.2.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saffari M, Lin C-Y, Chen H, et al. The role of religious coping and social support on medication adherence and quality of life among the elderly with type 2 diabetes. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(8):2183–2193. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02183-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adisa R, Olajide OO, Fakeye TO. Social support, treatment adherence and outcome among hypertensive and type 2 diabetes patients in ambulatory care settings in southwestern Nigeria. Ghana Med J. 2017;51(2):64–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smalls BL, Gregory CM, Zoller JS, et al. Assessing the relationship between neighborhood factors and diabetes related health outcomes and self-care behaviors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):445. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1086-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tiv M, Viel JF, Mauny F, et al. Medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: the ENTRED study 2007, a French Population-Based Study. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osborn CY, Egede LE. The relationship between depressive symptoms and medication nonadherence in type 2 diabetes: the role of social support. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(3):249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bouldin ED, Trivedi RB, Reiber GE, et al. Associations between having an informal caregiver, social support, and self-care among low-income adults with poorly controlled diabetes. Chronic Illn. 2017;13(4):239–250. doi: 10.1177/1742395317690032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Y, Song H-J, Han H-R, et al. Unmet needs for social support and effects on diabetes self-care activities in Korean Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(1):77–85. doi: 10.1177/0145721711432456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watkins YJ, Quinn LT, Ruggiero L, et al. Spiritual and religious beliefs and practices and social support’s relationship to diabetes self-care activities in African Americans. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(2):231–239. doi: 10.1177/0145721713475843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JR, Novak JR, Johnson MD, et al. A dyadic multiple mediation model of patient and spouse stressors predicting patient dietary and exercise adherence via depression symptoms and diabetes self-efficacy. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):1020–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9796-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell RA, Andrews JS, Arcury TA, et al. Depressive symptoms and diabetes self-management among rural older adults. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(1):36–44. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Ting RZ, Yang W, et al. Depression in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: associations with hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and poor treatment adherence. J Diabetes. 2015;7(6):800–808. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carper MM, Traeger L, Gonzalez JS, et al. The differential associations of depression and diabetes distress with quality of life domains in type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2014;37(3):501–510. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9505-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweileh WM, Abu-Hadeed HM, Al-Jabi SW, et al. Prevalence of depression among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross sectional study in Palestine. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):163. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuberi SI, Syed EU, Bhatti JA. Association of depression with treatment outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study from Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shahrabad HD, Bayazi MH, Zafari Z, et al. The effect of lazarus multimodal therapy on depression, anxiety, and blood glucose control in women with type 2 diabetes. J Fundam Mental Health. 2018;20(4):302–309. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ciebiada M, Barylski M, Górska-Ciebiada M. Ocena stopnia przestrzegania zaleceń lekarskich u starszych chorych na cukrzycę z towarzyszącymi objawami depresyjnymi. Geriatria. 2017;11:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Górska-Ciebiada M, Ciebiada M. Predictors of poor glycaemic control in type 2 diabetic elderly patients with depressive syndrome. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17(6):504–505. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akpalu J, Yorke E, Ainuson-Quampah J, et al. Depression and glycaemic control among type 2 diabetes patients: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary healthcare facility in Ghana. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):357. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1933-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linetzky B, Jiang D, Funnell MM, et al. Exploring the role of the patient-physician relationship on insulin adherence and clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes: insights from the MOSAIc study. J Diabetes. 2017;9(6):596–605. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratanawongsa N, Karter AJ, Parker MM, et al. Communication and medication refill adherence: the diabetes study of Northern California. J Am Med Assoc Intern Med. 2013;173:210–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirkman MS, Rowan-Martin MT, Levin R, et al. Determinants of adherence to diabetes medications: findings from a large pharmacy claims database. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):604–609. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie Z, Liu K, Or C, et al. An examination of the socio-demographic correlates of patient adherence to self-management behaviors and the mediating roles of health attitudes and self-efficacy among patients with coexisting type 2 diabetes and hypertension. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1227. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09274-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mutyambizi C, Pavlova M, Hongoro C, et al. Inequalities and factors associated with adherence to diabetes self-care practices amongst patients at two public hospitals in Gauteng, South Africa. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12902-020-0492-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alfian SD, Denig P, Coelho A, et al. Pharmacy-based predictors of non-adherence, non-persistence and reinitiation of antihypertensive drugs among patients on oral diabetes drugs in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahfouz EM, Awadalla HI. Compliance to diabetes self-management in rural El-Mina, Egypt. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2011;19(1):35–41. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mendes R, Martins S, Fernandes L. Adherence to medication, physical activity and diet in older adults with diabetes: its association with cognition, anxiety and depression. J Clin Med Res. 2019;11(8):583–592. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akturk U, Aydinalp E. Examining the correlation between the acceptance of the disease and the diabetes self-efficacy of the diabetic patients in a family health center. Ann Med Res. 2018;25(3):359–364. doi: 10.5455/annalsmedres.2018.05.075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alyami M, Serlachius A, Mokhtar I, et al. Illness perceptions, HbA1c, and adherence in type 2 diabetes in Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1839–1850. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S228670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Özkaptan BB, Kapucu S, Demirci I. Relationship between adherence to treatment and acceptance of illness in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cukurova Med J. 2019;44(Suppl 1):447–454. doi: 10.17826/cumj.554402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Can S, Can Cicek S, Ankarali H. The effect of illness acceptance on diabetes self care activities in diabetic individuals. Int J Caring Sci. 2020;13(3):2191–2200. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhippayom T, Krass I. Medication-taking behaviour in New South Wales patients with type 2 diabetes: an observational study. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(4):429–437. Erratum in: Aust J Prim Health. 2016;22(6):576. doi: 10.1071/PY14062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graça Pereira M, Ferreira G, Machado JC, et al. Beliefs about medicines as mediators in medication adherence in type 2 diabetes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;25(5):e12768. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoel U, Abu-Hammad T, Cohen A, et al. Behind the scenes of adherence in a minority population. Isr Med Assoc J. 2013;15(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosland AM, Kieffer E, Spencer M, et al. Do pre-existing diabetes social support or depressive symptoms influence the effectiveness of a diabetes management intervention? Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(11):1402–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosland AM, Piette JD, Lyles CR, et al. Social support and lifestyle vs. medical diabetes self-management in the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Ann Behav Med. 2014;48(3):438–447. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9623-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies – evidence for action. Available from: https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4883e/8.5.4.html. Accessed January27, 2021.

- 54.Gonzalez JS, Tanenbaum ML, Commissariat PV. Psychosocial factors in medication adherence and diabetes self-management: implications for research and practice. Am Psychol. 2016;71(7):539–551. doi: 10.1037/a0040388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biessels GJ, Despa F. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(10):591–604. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0048-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Basu S, Garg S, Sharma N, et al. Enhancing medication adherence through improved patient-provider communication: the 6A’s of intervention. J Assoc Physicians India. 2019;67(7):69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Atreja A, Bellam N, Levy SR. Strategies to enhance patient adherence: making it simple. MedGenMed. 2005;7(1):4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]