Abstract

Intermediate filaments (IFs) perform a diverse set of well-known functions including providing structural support for the cell and resistance to mechanical stress, yet recent evidence has revealed unexpected roles for IFs as stress response proteins. Previously it was shown that the type III IF protein vimentin forms cage-like structures around centrosome-associated proteins destined for degradation, structures referred to as aggresomes, suggesting a role for vimentin in protein turnover. However, vimentin’s function at the aggresome has remained largely understudied. In a recent report, vimentin was shown to be dispensable for aggresome formation, but played a critical role in protein turnover at the aggresome through localizing proteostasis-related machineries, such as proteasomes, to the aggresome. Here we review evidence for vimentin’s function in proteostasis and highlight the organismal implications of these findings.

Introduction

Maintaining protein homeostasis (proteostasis) is critical for an organism’s ability to properly function and avoid disease (Douglas and Dillin 2010). To ensure proteostasis is maintained, cells have evolved three primary systems which are thought to respond to elevated levels of misfolded, damaged or mutant proteins: chaperones, the ubiquitin-proteasome system, and autophagy. Chaperones are a class of proteins that, amongst many functions, are able to bind to proteins and assist in their refolding or target them for degradation by protein degradation systems (Barral, Broadley et al. 2004). The ubiquitin-proteasome system involves a network of proteins that first identify proteins destined for degradation, label them with polyubiquitin, and subsequently target them to proteasomes for proteolysis (Collins and Goldberg 2017). Finally, autophagy consists of the loading of larger protein inclusions into autophagosomes which then can fuse with acidified lysosomes to denature proteins via an acidic environment and lysosomal proteases (Wong and Cuervo 2010). Collectively, in healthy organisms and in many pathological contexts, these mechanisms are sufficient to maintain proteostasis. However, there are also many situations in which these systems fail to sufficiently turn over protein which ultimately result in disrupted proteostasis and impaired cellular viability (Douglas and Dillin 2010).

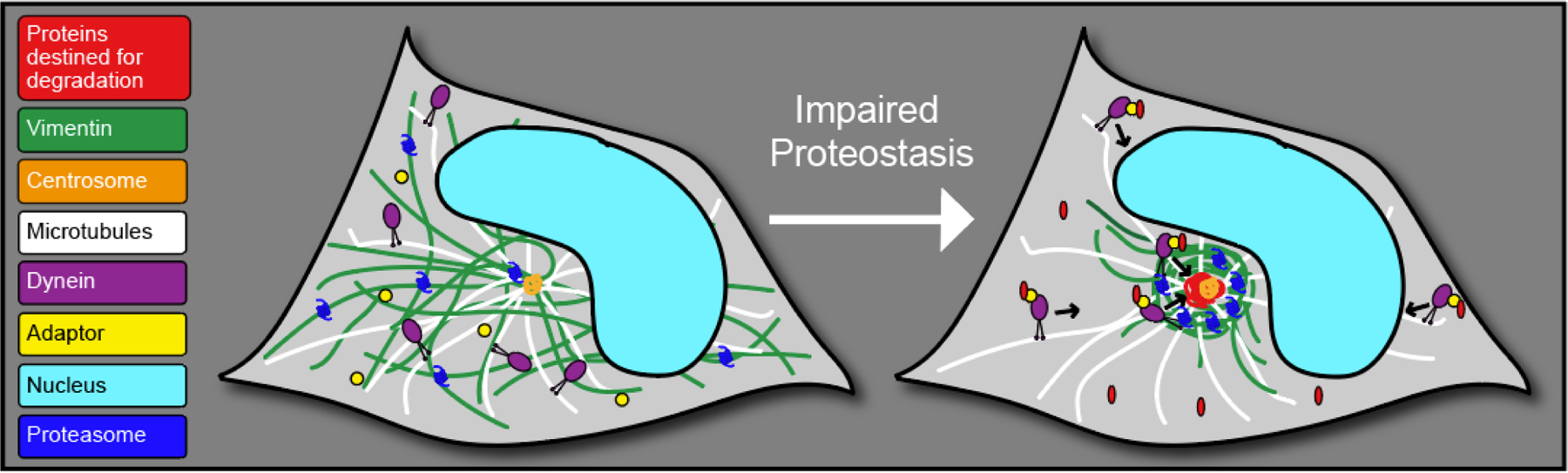

When proteostasis is disrupted, cells may employ additional mechanisms to ensure proper cellular function is maintained. One of these mechanisms involves the trafficking of proteins destined for degradation by dynein motor proteins along microtubules to the centrosome, which is surrounded by a cage composed of the IF vimentin. This structure is referred to as the aggresome (Johnston, Ward et al. 1998, Johnston, Illing et al. 2002, Kawaguchi, Kovacs et al. 2003, Iwata, Riley et al. 2005) (Fig. 1). The terms “inclusion bodies” and “aggresomes” have been used somewhat interchangeably to describe protein aggregates that are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm. However, here we define the “aggresome” as a distinct cytoplasmic structure rich in proteins destined for degradation present at the centrosome/nuclear bay that is dependent on microtubules to form and which resides within a cage comprised of IFs (Johnston, Ward et al. 1998). Since the aggresome was first identified in 1998, much has become clear about mechanisms driving aggresome formation and clearance, and the numerous healthy and pathological contexts in which the aggresome is utilized by cells (French, van Leeuwen et al. 2001, Johnston, Illing et al. 2002, Kawaguchi, Kovacs et al. 2003, Olzmann, Li et al. 2008, Xu, Graham et al. 2013, Morrow, Porter et al. 2020). However, the role of vimentin at the aggresome has remained largely unexplored.

Figure 1 –

Schematic of aggresome formation. During conditions where proteostasis becomes disrupted, proteins destined for degradation (red) are trafficked by dynein (purple) and adapter proteins (yellow) along microtubules (white) to the centrosome (orange), accompanied by a collapse of the IF vimentin (green) and a redistribution of proteasomes (dark blue) to the nuclear bay.

Vimentin is a type III IF comprised of a central rod domain with a head and tail domain on either side, and is expressed in numerous cell types throughout the body in many organisms (Perreau, Lilienbaum et al. 1988, Schaffeld, Herrmann et al. 2001, Herrmann and Aebi 2004, Danielsson, Peterson et al. 2018). Vimentin is able to polymerize either by itself or heteropolymerize with other IFs into non-polar unit length filaments which can assemble into full length filaments (Steven, Hainfeld et al. 1983, Herrmann, Haner et al. 1996). Two decades ago, vimentin knockout (KO) mice were created and observed to develop and reproduce with no obvious phenotypes, suggesting that vimentin may be dispensable for the organism’s general viability (Colucci-Guyon, Portier et al. 1994). However since then, numerous reports have emerged suggesting that although vimentin is not important for early-development, vimentin becomes critical during a response to a wide variety of challenges (Table 1) (Terzi, Henrion et al. 1997, Rogel, Soni et al. 2011, Cheng, Shen et al. 2016, Danielsson, Peterson et al. 2018). For example, vimentin is now recognized as a critical player in directional migration during wound healing (Rogel, Soni et al. 2011). Vimentin also has been observed to dynamically upregulate in response to challenges such as heat shock and cadmium chloride treatment (Vilaboa, Garcia-Bermejo et al. 1997). Thus, the precedent of vimentin being a stress response protein supports the notion that vimentin could be important for recovering proteostasis in the cell after a cellular stress which impairs proteostasis. Here we review investigations of vimentin’s function in maintaining proteostasis at the aggresome, and discuss the implications of vimentin’s function at the aggresome in both healthy organisms and in numerous pathologies and diseases.

Table 1 –

Diverse phenotypes in vimentin KO organisms/cells

| Vimentin KO Phenotype | Source |

|---|---|

| Immune response | |

| Reduced replication of murine cytomegalovirus | (Roy, Kapoor et al. 2020) |

| Reduced activation of the inflammasome | (Xiao, Xie et al. 2018) |

| Reduced fibroblast proliferation, keratinocyte differentiation, and wound healing | (Cheng, Shen et al. 2016) |

| Reduced lung inflammation following bleomycin exposure | (dos Santos, Rogel et al. 2015) |

| Longer tail bleeding time | (Da, Behymer et al. 2014) |

| Increased acute colitis | (Mor-Vaknin, Legendre et al. 2013) |

| Impaired microglia activation | (Jiang, Slinn et al. 2012) |

| Impaired glial scar formation (in combination with GFAP KO) | (Pekny, Johansson et al. 1999) |

| Structural support | |

| Increased mechanical stress generation | (van Loosdregt, Weissenberger et al. 2018) |

| Increased actin stress fiber assembly and contractility | (Jiu, Peranen et al. 2017) |

| Death in response to renal mass reduction | (Terzi, Henrion et al. 1997) |

| Impaired flow-induced dilation in mesenteric resistance arteries | (Henrion, Terzi et al. 1997) |

| Reduced cytoplasmic stiffness | (Guo, Ehrlicher et al. 2013) |

| Reduced lymphocyte rigidity | (Brown, Hallam et al. 2001) |

| Higher expression of sub-endothelial basement membranes | (Langlois, Belozertseva et al. 2017) |

| Reduced collagen production | (Challa and Stefanovic 2011) |

| Compromised endothelial integrity | (Nieminen, Henttinen et al. 2006) |

| Development | |

| Cerebellar development defects and impaired motor coordination | (Colucci-Guyon, Gimenez et al. 1999) |

| Disrupted vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation | (van Engeland, Suarez Rodriguez et al. 2019) |

| Impaired mammary gland development | (Peuhu, Virtakoivu et al. 2017) |

| Disrupted endothelial differentiation of embryonic stem cells | (Boraas and Ahsan 2016) |

| Decreased axonal outgrowth and uptake of C3bot | (Adolf, Leondaritis et al. 2016) |

| Altered arterial remodeling | (Schiffers, Henrion et al. 2000) |

| Disrupted Notch signaling and impaired angiogenesis | (Antfolk, Sjoqvist et al. 2017) |

| Intermediate filament network formation | |

| Disrupted GFAP network | (Galou, Colucci-Guyon et al. 1996) |

| Disrupted nestin polymerization | (Park, Xiang et al. 2010) |

| Impaired desmin filament formation | (Geerts, Eliasson et al. 2001) |

| Motility/Migration | |

| Increased motility of caveolin-1 vesicles | (Shi, Fan et al. 2020) |

| Impaired directional cell migration | (Vakhrusheva, Endzhievskaya et al. 2019) |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Disrupted subcellular localization of Na-glucose transporters | (Runembert, Couette et al. 2004) |

| No obvious phenotypes in vimentin KO mice | (Colucci-Guyon, Portier et al. 1994) |

| Decreased astrocyte activation (in combination with GFAP KO) | (Wilhelmsson, Faiz et al. 2012) |

| Reduced ability to respond to proteotoxic stress | (Morrow, Porter et al. 2020) |

| Increased rearrangement of the mitochondrial genome | (Bannikova, Zorov et al. 2005) |

| Reduced fibroblast proliferation rate and inability to immortalize | (Tolstonog, Shoeman et al. 2001) |

Vimentin’s function at the aggresome

The identification of vimentin’s presence at the aggresome more than 2 decades ago suggested a new role for this IF. Despite this observation, while many studies have utilized vimentin as a marker of aggresome formation, few have addressed vimentin’s function in proteostasis at the aggresome. To address this question, we recently investigated vimentin’s function at the aggresome in mouse primary hippocampal neural stem cells (NSCs) (Morrow, Porter et al. 2020). Interestingly, vimentin KO NSCs were still able to form an aggresome, demonstrating that vimentin is not essential for aggresome formation. However, vimentin KO NSCs displayed a decreased capacity to recover from impaired proteostasis both after a transient challenge with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 in vitro and during NSC quiescence exit in vitro and in vivo, a time when NSCs must clear a wave of proteins to activate and enter the cell cycle. Vimentin KO NSCs not only displayed reduced viability after a transient pulse with the proteasome inhibitor MG132, but also an increased accumulation of aggregated proteins. Vimentin KO NSCs compensated for defects in protein clearance by increasing autophagy, however, were still unable to recover to the same extent as WT NSCs. Further, we identified through co-immunoprecipitation that vimentin bound several types of proteostasis-related machineries at the aggresome, suggesting that vimentin is critical for efficient protein turnover by acting as a scaffold for these machineries at the aggresome. Immunostaining and proximity ligation assays confirmed that proteasomes, identified in the co-immunoprecipitation, were enriched at the aggresome in WT NSCs, but not in vimentin KO NSCs. Thus, this suggested that vimentin’s function at the aggresome was, at least in part, to localize proteasomes to the aggresome for efficient protein turnover. However, the extent to which this mechanism drives the phenotypes reported in vimentin KO NSCs is not fully clear as numerous other proteostasis machineries, such as ribosomal proteins and chaperone proteins, were also pulled down by vimentin in NSCs. Vimentin KO in NSCs also resulted in a loss of nestin and Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) IFs, making it difficult to understand if the phenotypes observed in NSCs were vimentin-specific or due to the loss of these other IF proteins. Interestingly, there was no compensation by any other IF in the absence of vimentin. Together, these findings suggest that vimentin’s repositioning of proteasomes to the aggresome in NSCs following impaired proteostasis is critical to essential cellular functions.

Similar to our hypothesis that vimentin is critical for positioning cellular components in the cell, it has also been proposed that vimentin is a regulator of autophagosome and lysosome distribution in HEK293 cells, and that vimentin potentiates autophagy (Biskou, Casanova et al. 2019). This study utilized treatment with the compound Withaferin A (WFA), which binds vimentin and inhibits filament formation, to perturb the filamentous vimentin network and probe for downstream consequences. WFA treatment induced a redistribution of vimentin protein to the aggresome along with autophagosomes and lysosomes. Further, WFA perturbed autophagy through disruption of autophagosome-lysosome fusion (Biskou, Casanova et al. 2019). However, WFA has been found to be cytotoxic even in vimentin KO cells, suggesting that WFA is not specific to targeting vimentin (Bargagna-Mohan, Hamza et al. 2007). For example, WFA also has been observed to perturb the cell’s microtubule network (Grin, Mahammad et al. 2012). WFA’s prevention of vimentin polymerization also could result in increases in vimentin degradation which could overwhelm protein turnover systems and lead to measurable perturbations in autophagy such as what was reported. This scenario is further supported by the recent observation that vimentin can be degraded by autophagy (Park, Yoon et al. 2020). Thus, it would be interesting to reexamine these findings in a vimentin KO or KD cell line which may be less limited by the non-specific activities of WFA.

Additionally in line with the view that vimentin can function through binding and localizing of cellular components to different regions within the cytoplasm, vimentin has been reported to increase activity of the intracellular calcium channel inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptor type 1 (IP3R1) through sequestering the negative IP3R1 regulator, IP3R1-interacting protein released with IP3 (IRBIT), to the aggresome (Bauer, Hudec et al. 2012). However, this role for vimentin was suggested to be detrimental to the cell’s capacity to maintain proteostasis, as increased IP3R1 activity was previously connected with increased aggregation of overexpressed mutant Huntington protein in Neuro-2a cells (Bauer, Hudec et al. 2011). In line with this model, vimentin overexpression in Neuro-2a cells increased levels of overexpressed aggregated Huntingtin protein and mild vimentin knock-down (KD) decreased levels of overexpressed aggregated Huntingtin protein (Bauer, Hudec et al. 2012). Whereas overexpressing proteins such as vimentin could be detrimental to a cell by introducing an overabundance of proteins that interfere with cellular processes or compete with endogenous proteins that require degradation, how vimentin KD results in an increased capacity to maintain proteostasis in Neuro-2a cells overexpressing Huntingtin protein is less clear compared with our model in which vimentin is beneficial for the cell’s capacity to maintain proteostasis (Morrow, Porter et al. 2020). As mutant Huntingtin has an increased propensity to aggregate, rendering it resistant to degradation by the proteasome, vimentin’s function in localizing proteasomes to the aggresome may be less consequential for degrading these proteins (Thibaudeau, Anderson et al. 2018). Further, due to the complexity and variety of dynamically regulated pathways that are able to compensate for impaired nodes of the cell’s proteostasis network, it is also possible that weak KD of vimentin could be acting as a type of hormesis for the cell which then becomes exacerbated in a stronger KD or full vimentin KO cells. Finally, as the authors utilized both Neuro-2a cells and HeLa cells, both of which are cancer cell lines, it may be interesting to see if similar effects are seen in primary cells, as cancer cells may have modified their methods of responding to disruptions in proteostasis (see below a further discussion on cancer in part II).

Vimentin and the aggresome also can be asymmetrically inherited during mitosis (Rujano, Bosveld et al. 2006, Ogrodnik, Salmonowicz et al. 2014, Moore, Pilz et al. 2015, Morrow, Porter et al. 2020). Thus, any functions that vimentin may serve in interphase, such as what is described above, can be asymmetrically distributed between two daughter cells after mitosis and could lead to distinct cell behavioral outcomes. Indeed, the daughter cell inheriting more vimentin and the aggresome is associated with a relatively longer cell-cycle length and an increased chance of undergoing apoptosis (Ogrodnik, Salmonowicz et al. 2014, Moore, Pilz et al. 2015). However, it remains unclear if inheriting more vimentin and the aggresome would always be bad for the cell. For example, daughter cells inheriting more vimentin-associated proteins, such as proteasomes, could be better equipped to handle specific circumstances compared to daughter cells with less inherited proteasomes (Morrow, Porter et al. 2020). It has not yet been determined whether daughter cells which inherit more or less vimentin have different capacities to maintain proteostasis after mitosis.

Together, while the field has now answered several key questions about vimentin’s function in proteostasis, this topic remains largely understudied. Additional research is needed to reconcile unresolved discrepancies, as numerous elements could factor into conflicting findings, such as: cell type, KO of vimentin as opposed to KD of vimentin, and different techniques to measure or enhance protein accumulation (endogenous labeling of aggregated proteins as opposed to mutant Huntingtin overexpression). What these studies do agree upon is that vimentin interacts with a diverse set of proteins and that, whether for the better or the worse, perturbing vimentin potentiates the cell’s capacity to maintain proteostasis.

Organismal implications for vimentin’s function at the aggresome

Although vimentin KO mice retain the ability to develop and reproduce normally, vimentin plays numerous critical roles throughout the body, and can be upregulated in pathological contexts (Danielsson, Peterson et al. 2018). As mounting evidence supports a role for vimentin in the cell’s proteostasis network, vimentin’s action at the aggresome could be a putative mechanism underlying previously established vimentin KO phenotypes.

Many reports have demonstrated general reduced cellular function in vimentin KO cells (Galou, Gao et al. 1997, Terzi, Henrion et al. 1997, Vilaboa, Garcia-Bermejo et al. 1997, Lundkvist, Reichenbach et al. 2004, Perez-Sala, Oeste et al. 2015, Boraas and Ahsan 2016, Cheng, Shen et al. 2016). For example, vimentin KO fibroblasts display a slower proliferation rate (Cheng, Shen et al. 2016), and vimentin KO embryonic stem cells have a reduced capacity to differentiate down a endothelial lineage (Boraas and Ahsan 2016). These findings suggest that vimentin’s functions within the cell are important for maintaining basic cellular functions which could translate into the numerous phenotypes reported in vimentin KO organisms (Table 1) (Danielsson, Peterson et al. 2018). Although vimentin’s previously established mechanisms of action could contribute to these phenotypes, such as vimentin’s function in cell motility and adhesion, it is also possible that these phenotypes are the result of an impaired capacity to maintain proteostasis through mechanisms such as what is described above (Danielsson, Peterson et al. 2018). Closer examination for the presence of aggresome formation in these cells would shed light on whether vimentin’s function at the aggresome is playing a role in these phenotypes.

Vimentin’s function in proteostasis may also be important for an organism’s defense against pathologies and diseases throughout the body. For example, vimentin and the aggresome are studied in the lung where they respond to insults such as exposure to cigarette smoke or lung pathologies such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), which can display elevated ubiquitinated protein levels and impaired proteostasis (Min, Bodas et al. 2011, Tran, Ji et al. 2015, Shivalingappa, Hole et al. 2016). Further, many diseases and stimuli can induce disrupted proteostasis in the liver, some of which culminate in aggresome formation (French, van Leeuwen et al. 2001, Bardag-Gorce, Riley et al. 2004, French, Mendoza et al. 2016, French, Masouminia et al. 2017). Thus, there are plenty of pathological contexts which may warrant vimentin’s action at the aggresome. However, not all cell types throughout the body express vimentin. Therefore, it would be important to verify that the cell type being studied either already expressed vimentin or upregulated vimentin as a complement to aggresome formation to understand if vimentin is playing a role in these circumstances. In the event that vimentin is not expressed, other IFs could play an analogous role to vimentin. Indeed, in mouse motor neuron-neuroblastoma cells the neurofilament network was observed to collapse around aggresomes formed by overexpression of a truncated androgen receptor with a 112-glutamine repeat in vitro (Taylor, Tanaka et al. 2003). It remains unclear if this observation would translate to bonafide neurons in vivo. Further, as many intermediate filaments heteropolymerize, it is likely that many intermediate filament proteins (such as nestin and GFAP) could be similarly enriched in the cage surrounding the aggresome and that these proteins could be performing functions analogous to vimentin (Steven, Hainfeld et al. 1983, Morrow, Porter et al. 2020).

Further supporting the notion that vimentin plays a role in pathologies across the body, vimentin is also upregulated in tissues during several pathologies where proteostasis is disrupted. For example, neurons in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease (Tg2576), which normally don’t express vimentin once mature, upregulate vimentin during disease progression (Levin, Acharya et al. 2009). Further, vimentin also has been found in human Alzheimer’s Disease amyloid plaques (Liao, Cheng et al. 2004, Rudrabhatla, Jaffe et al. 2011). Finally, vimentin expression is increased generally during aging in tissues, such as the brain (Xu, Gao et al. 2016, Benayoun, Pollina et al. 2019). A recent quantitative proteomic analysis during aging in the hippocampus, an area critical for learning and memory, found vimentin as one of 35 upregulated genes out of 4582 that were analyzed (Xu, Gao et al. 2016). One explanation may be that vimentin is upregulated in reactive astrocytes; however, it could also be that vimentin becomes activated to respond to the disruptions in proteostasis that are sustained in the brain during aging (Wang, Bekar et al. 2004).

While there are numerous scenarios in which vimentin’s activity at the aggresome could be interpreted as beneficial, there are also scenarios in which the organism sustains greater consequences from an optimally functioning vimentin-caged aggresome such as in cancers and viral infection. Aggresomes and vimentin are widely studied chemotherapeutic targets in combination with proteasome inhibitors in cancers such as multiple myeloma, breast cancer and pancreatic cancer (Nawrocki, Carew et al. 2006, Komatsu, Moriya et al. 2013, Mishima, Santo et al. 2015, Park, Yoon et al. 2020). Interestingly, indirectly inhibiting aggresome function synergistically increases cytotoxicity associated with proteasome inhibition in a pancreatic cancer xenograft (Nawrocki, Carew et al. 2006). Other studies have reported that vimentin KO tumors have an impaired ability to metastasize, which may be mediated by a reduced capacity to migrate (Liu, Lin et al. 2015). However, an alternative explanation may be that vimentin KO tumors have a decreased capacity to maintain proteostasis. Together, these findings combined with vimentin’s role in proteostasis suggest that vimentin could be viewed as a target for not only reducing tumor metastasis, but also the tumor’s ability to maintain proteostasis.

Aggresomes have also been implicated in the cell’s response to viral infection. While the precise mechanism(s) by which viruses benefit from hijacking the aggresome are not fully clear, cells with impaired aggresome formation display reduced viral propagation, suggesting that an optimally functioning aggresome would be beneficial for viruses and detrimental for the organism (Nozawa, Yamauchi et al. 2004, Liu, Shevchenko et al. 2005). Thus, vimentin also could be viewed potentially as a target to reduce the virus’ capacity to propagate. These examples suggest that an optimally functioning aggresome may provide cellular benefits that may not always be beneficial to the organism and that it may not always be desirable to utilize vimentin to increase the cell’s capacity to recover proteostasis.

There are many examples of vimentin and the aggresome dynamically responding to numerous different healthy and pathological stimuli. Recent data investigating vimentin’s role in maintaining proteostasis at the aggresome provides a new consideration for vimentin in a myriad of diverse cellular functions and phenotypes. Future research will be needed to fully understand how this mechanism functions with other established roles of vimentin in these diverse conditions.

Future Directions

Evidence suggests that vimentin plays numerous unique roles in the cell, many of which fall under the umbrella of the cell’s response to stress. While many components of vimentin’s function in these processes are known, the field is still limited by the absence of critical and effective tools. For example, currently there is no mouse line that allows for conditional knock-out of vimentin, but only a full vimentin KO mouse that has had vimentin removed throughout development in all cell types. Therefore, all studies to date in vimentin KO mice are limited by any compensatory mechanisms that this line has generated to adapt to vimentin KO, and in the inability to determine cell-specific effects. Further, many studies investigating vimentin’s presence and function at the aggresome have relied on visualizing vimentin through overexpression of vimentin fused to a fluorophore, which could also be inducing artificial phenotypes that are less reminiscent of endogenous vimentin. Despite technical limitations, it is clear that vimentin expression and distribution in the cell are dynamic and functionally important in many cell types in numerous contexts. Improved tools can be used to resolve discrepancies in the understanding of vimentin’s role in proteostasis and further reveal how in vitro studies in cell lines translate into organismal changes in vivo.

As vimentin and IFs are expressed in a tissue-specific manner, it will be interesting to determine how cell types that don’t express vimentin maintain proteostasis through compensation by other nodes of the proteostasis network. For example, it is well-established that impairments in the ubiquitin-proteasome system can lead to increases in autophagy and vice versa (Dikic 2017). Further, revealing how species such as Drosophila melanogaster were able to evolve in the absence of IFs may reveal mechanisms of compensation by other mechanisms (Bohnekamp, Cryderman et al. 2016). Both of these phenomena may be explained by the fact that many roles of vimentin involve increased resilience to cellular challenges that would only become important in specific settings. These roles are also often redundant and provide increased efficiency in a cellular process, rather than an essential function that the cell could not complete otherwise. Additionally, as expression of vimentin has been shown to be harmful for organisms in specific scenarios such as cancer or viral infection, it may be that organisms have carefully evolved to only use vimentin in places where they are needed most to minimize their potential to cause harm to the organism. Vimentin’s cell-type specific expression raises the prospect that not all cells are using all of the tools nature has provided them with to maintain proteostasis. Identifying the molecular determinants driving vimentin’s function in maintaining proteostasis could lead to development of targeted therapies that can modulate cellular proteostasis and ultimately improve diseases resulting from impaired proteostasis.

Acknowledgements

We thank the funding sources that supported this work: NIH T32 GM008688 (to C.S.M.), AFAR Young Investigator Award (to D.L.M.), the Sloan Foundation Fellowship (to D.L.M.), Shaw Scientist Award (to D.L.M.), and a DP2 NIH New Innovator Award (to D.L.M.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adolf A, Leondaritis G, Rohrbeck A, Eickholt BJ, Just I, Ahnert-Hilger G and Holtje M (2016). “The intermediate filament protein vimentin is essential for axonotrophic effects of Clostridium botulinum C3 exoenzyme.” J Neurochem 139(2): 234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antfolk D, Sjoqvist M, Cheng F, Isoniemi K, Duran CL, Rivero-Muller A, Antila C, Niemi R, Landor S, Bouten CVC, Bayless KJ, Eriksson JE and Sahlgren CM (2017). “Selective regulation of Notch ligands during angiogenesis is mediated by vimentin.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(23): E4574–E4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannikova S, Zorov DB, Shoeman RL, Tolstonog GV and Traub P (2005). “Stability and association with the cytomatrix of mitochondrial DNA in spontaneously immortalized mouse embryo fibroblasts containing or lacking the intermediate filament protein vimentin.” DNA Cell Biol 24(11): 710–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardag-Gorce F, Riley NE, Nan L, Montgomery RO, Li J, French BA, Lue YH and French SW (2004). “The proteasome inhibitor, PS-341, causes cytokeratin aggresome formation.” Exp Mol Pathol 76(1): 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargagna-Mohan P, Hamza A, Kim YE, Khuan Abby Ho Y, Mor-Vaknin N, Wendschlag N, Liu J, Evans RM, Markovitz DM, Zhan CG, Kim KB and Mohan R (2007). “The tumor inhibitor and antiangiogenic agent withaferin A targets the intermediate filament protein vimentin.” Chem Biol 14(6): 623–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral JM, Broadley SA, Schaffar G and Hartl FU (2004). “Roles of molecular chaperones in protein misfolding diseases.” Semin Cell Dev Biol 15(1): 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PO, Hudec R, Goswami A, Kurosawa M, Matsumoto G, Mikoshiba K and Nukina N (2012). “ROCK-phosphorylated vimentin modifies mutant huntingtin aggregation via sequestration of IRBIT.” Mol Neurodegener 7: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PO, Hudec R, Ozaki S, Okuno M, Ebisui E, Mikoshiba K and Nukina N (2011). “Genetic ablation and chemical inhibition of IP3R1 reduce mutant huntingtin aggregation.” Biochem Biophys Res Commun 416(1–2): 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benayoun BA, Pollina EA, Singh PP, Mahmoudi S, Harel I, Casey KM, Dulken BW, Kundaje A and Brunet A (2019). “Remodeling of epigenome and transcriptome landscapes with aging in mice reveals widespread induction of inflammatory responses.” Genome Res 29(4): 697–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biskou O, Casanova V, Hooper KM, Kemp S, Wright GP, Satsangi J, Barlow PG and Stevens C (2019). “The type III intermediate filament vimentin regulates organelle distribution and modulates autophagy.” PLoS One 14(1): e0209665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnekamp J, Cryderman DE, Thiemann DA, Magin TM and Wallrath LL (2016). “Using Drosophila for Studies of Intermediate Filaments.” Methods Enzymol 568: 707–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boraas LC and Ahsan T (2016). “Lack of vimentin impairs endothelial differentiation of embryonic stem cells.” Sci Rep 6: 30814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MJ, Hallam JA, Colucci-Guyon E and Shaw S (2001). “Rigidity of circulating lymphocytes is primarily conferred by vimentin intermediate filaments.” J Immunol 166(11): 6640–6646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challa AA and Stefanovic B (2011). “A novel role of vimentin filaments: binding and stabilization of collagen mRNAs.” Mol Cell Biol 31(18): 3773–3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F, Shen Y, Mohanasundaram P, Lindstrom M, Ivaska J, Ny T and Eriksson JE (2016). “Vimentin coordinates fibroblast proliferation and keratinocyte differentiation in wound healing via TGF-beta-Slug signaling.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(30): E4320–4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GA and Goldberg AL (2017). “The Logic of the 26S Proteasome.” Cell 169(5): 792–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci-Guyon E, Gimenez YRM, Maurice T, Babinet C and Privat A (1999). “Cerebellar defect and impaired motor coordination in mice lacking vimentin.” Glia 25(1): 33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci-Guyon E, Portier MM, Dunia I, Paulin D, Pournin S and Babinet C (1994). “Mice lacking vimentin develop and reproduce without an obvious phenotype.” Cell 79(4): 679–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Q, Behymer M, Correa JI, Vijayan KV and Cruz MA (2014). “Platelet adhesion involves a novel interaction between vimentin and von Willebrand factor under high shear stress.” Blood 123(17): 2715–2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson F, Peterson MK, Caldeira Araujo H, Lautenschlager F and Gad AKB (2018). “Vimentin Diversity in Health and Disease.” Cells 7(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic I (2017). “Proteasomal and Autophagic Degradation Systems.” Annu Rev Biochem 86: 193–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos G, Rogel MR, Baker MA, Troken JR, Urich D, Morales-Nebreda L, Sennello JA, Kutuzov MA, Sitikov A, Davis JM, Lam AP, Cheresh P, Kamp D, Shumaker DK, Budinger GR and Ridge KM (2015). “Vimentin regulates activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.” Nat Commun 6: 6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas PM and Dillin A (2010). “Protein homeostasis and aging in neurodegeneration.” J Cell Biol 190(5): 719–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French BA, van Leeuwen F, Riley NE, Yuan QX, Bardag-Gorce F, Gaal K, Lue YH, Marceau N and French SW (2001). “Aggresome formation in liver cells in response to different toxic mechanisms: role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and the frameshift mutant of ubiquitin.” Exp Mol Pathol 71(3): 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SW, Masouminia M, Samadzadeh S, Tillman BC, Mendoza A and French BA (2017). “Role of Protein Quality Control Failure in Alcoholic Hepatitis Pathogenesis.” Biomolecules 7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SW, Mendoza AS and Peng Y (2016). “The mechanisms of Mallory-Denk body formation are similar to the formation of aggresomes in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.” Exp Mol Pathol 100(3): 426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galou M, Colucci-Guyon E, Ensergueix D, Ridet JL, Gimenez y Ribotta M, Privat A, Babinet C and Dupouey P (1996). “Disrupted glial fibrillary acidic protein network in astrocytes from vimentin knockout mice.” J Cell Biol 133(4): 853–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galou M, Gao J, Humbert J, Mericskay M, Li Z, Paulin D and Vicart P (1997). “The importance of intermediate filaments in the adaptation of tissues to mechanical stress: evidence from gene knockout studies.” Biol Cell 89(2): 85–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts A, Eliasson C, Niki T, Wielant A, Vaeyens F and Pekny M (2001). “Formation of normal desmin intermediate filaments in mouse hepatic stellate cells requires vimentin.” Hepatology 33(1): 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grin B, Mahammad S, Wedig T, Cleland MM, Tsai L, Herrmann H and Goldman RD (2012). “Withaferin a alters intermediate filament organization, cell shape and behavior.” PLoS One 7(6): e39065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Ehrlicher AJ, Mahammad S, Fabich H, Jensen MH, Moore JR, Fredberg JJ, Goldman RD and Weitz DA (2013). “The role of vimentin intermediate filaments in cortical and cytoplasmic mechanics.” Biophys J 105(7): 1562–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrion D, Terzi F, Matrougui K, Duriez M, Boulanger CM, Colucci-Guyon E, Babinet C, Briand P, Friedlander G, Poitevin P and Levy BI (1997). “Impaired flow-induced dilation in mesenteric resistance arteries from mice lacking vimentin.” J Clin Invest 100(11): 2909–2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H and Aebi U (2004). “Intermediate filaments: molecular structure, assembly mechanism, and integration into functionally distinct intracellular Scaffolds.” Annu Rev Biochem 73: 749–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Haner M, Brettel M, Muller SA, Goldie KN, Fedtke B, Lustig A, Franke WW and Aebi U (1996). “Structure and assembly properties of the intermediate filament protein vimentin: the role of its head, rod and tail domains.” J Mol Biol 264(5): 933–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata A, Riley BE, Johnston JA and Kopito RR (2005). “HDAC6 and microtubules are required for autophagic degradation of aggregated huntingtin.” J Biol Chem 280(48): 40282–40292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang SX, Slinn J, Aylsworth A and Hou ST (2012). “Vimentin participates in microglia activation and neurotoxicity in cerebral ischemia.” J Neurochem 122(4): 764–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiu Y, Peranen J, Schaible N, Cheng F, Eriksson JE, Krishnan R and Lappalainen P (2017). “Vimentin intermediate filaments control actin stress fiber assembly through GEF-H1 and RhoA.” J Cell Sci 130(5): 892–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JA, Illing ME and Kopito RR (2002). “Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin mediates the assembly of aggresomes.” Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 53(1): 26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JA, Ward CL and Kopito RR (1998). “Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins.” J Cell Biol 143(7): 1883–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kovacs JJ, McLaurin A, Vance JM, Ito A and Yao TP (2003). “The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress.” Cell 115(6): 727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu S, Moriya S, Che XF, Yokoyama T, Kohno N and Miyazawa K (2013). “Combined treatment with SAHA, bortezomib, and clarithromycin for concomitant targeting of aggresome formation and intracellular proteolytic pathways enhances ER stress-mediated cell death in breast cancer cells.” Biochem Biophys Res Commun 437(1): 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois B, Belozertseva E, Parlakian A, Bourhim M, Gao-Li J, Blanc J, Tian L, Coletti D, Labat C, Ramdame-Cherif Z, Challande P, Regnault V, Lacolley P and Li Z (2017). “Vimentin knockout results in increased expression of sub-endothelial basement membrane components and carotid stiffness in mice.” Sci Rep 7(1): 11628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin EC, Acharya NK, Sedeyn JC, Venkataraman V, D’Andrea MR, Wang HY and Nagele RG (2009). “Neuronal expression of vimentin in the Alzheimer’s disease brain may be part of a generalized dendritic damage-response mechanism.” Brain Res 1298: 194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L, Cheng D, Wang J, Duong DM, Losik TG, Gearing M, Rees HD, Lah JJ, Levey AI and Peng J (2004). “Proteomic characterization of postmortem amyloid plaques isolated by laser capture microdissection.” J Biol Chem 279(35): 37061–37068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Lin HH, Tang MJ and Wang YK (2015). “Vimentin contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition cancer cell mechanics by mediating cytoskeletal organization and focal adhesion maturation.” Oncotarget 6(18): 15966–15983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A and Berk AJ (2005). “Adenovirus exploits the cellular aggresome response to accelerate inactivation of the MRN complex.” J Virol 79(22): 14004–14016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundkvist A, Reichenbach A, Betsholtz C, Carmeliet P, Wolburg H and Pekny M (2004). “Under stress, the absence of intermediate filaments from Muller cells in the retina has structural and functional consequences.” J Cell Sci 117(Pt 16): 3481–3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min T, Bodas M, Mazur S and Vij N (2011). “Critical role of proteostasis-imbalance in pathogenesis of COPD and severe emphysema.” J Mol Med (Berl) 89(6): 577–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima Y, Santo L, Eda H, Cirstea D, Nemani N, Yee AJ, O’Donnell E, Selig MK, Quayle SN, Arastu-Kapur S, Kirk C, Boise LH, Jones SS and Raje N (2015). “Ricolinostat (ACY-1215) induced inhibition of aggresome formation accelerates carfilzomib-induced multiple myeloma cell death.” Br J Haematol 169(3): 423–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DL, Pilz GA, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Barral Y and Jessberger S (2015). “A mechanism for the segregation of age in mammalian neural stem cells.” Science 349(6254): 1334–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor-Vaknin N, Legendre M, Yu Y, Serezani CH, Garg SK, Jatzek A, Swanson MD, Gonzalez-Hernandez MJ, Teitz-Tennenbaum S, Punturieri A, Engleberg NC, Banerjee R, Peters-Golden M, Kao JY and Markovitz DM (2013). “Murine colitis is mediated by vimentin.” Sci Rep 3: 1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow CS, Porter TJ, Xu N, Arndt ZP, Ako-Asare K, Heo HJ, Thompson EAN and Moore DL (2020). “Vimentin Coordinates Protein Turnover at the Aggresome during Neural Stem Cell Quiescence Exit.” Cell Stem Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Pino MS, Highshaw RA, Andtbacka RH, Dunner K Jr., Pal A, Bornmann WG, Chiao PJ, Huang P, Xiong H, Abbruzzese JL and McConkey DJ (2006). “Aggresome disruption: a novel strategy to enhance bortezomib-induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells.” Cancer Res 66(7): 3773–3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen M, Henttinen T, Merinen M, Marttila-Ichihara F, Eriksson JE and Jalkanen S (2006). “Vimentin function in lymphocyte adhesion and transcellular migration.” Nat Cell Biol 8(2): 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa N, Yamauchi Y, Ohtsuka K, Kawaguchi Y and Nishiyama Y (2004). “Formation of aggresome-like structures in herpes simplex virus type 2-infected cells and a potential role in virus assembly.” Exp Cell Res 299(2): 486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodnik M, Salmonowicz H, Brown R, Turkowska J, Sredniawa W, Pattabiraman S, Amen T, Abraham AC, Eichler N, Lyakhovetsky R and Kaganovich D (2014). “Dynamic JUNQ inclusion bodies are asymmetrically inherited in mammalian cell lines through the asymmetric partitioning of vimentin.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(22): 8049–8054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olzmann JA, Li L and Chin LS (2008). “Aggresome formation and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications.” Curr Med Chem 15(1): 47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Xiang AP, Mao FF, Zhang L, Di CG, Liu XM, Shao Y, Ma BF, Lee JH, Ha KS, Walton N and Lahn BT (2010). “Nestin is required for the proper self-renewal of neural stem cells.” Stem Cells 28(12): 2162–2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Yoon SJ, Choi S, Kim JS, Lee MS, Lee SJ, Lee SH, Min JK, Son MY, Ryu CM, Yoo J and Park YJ (2020). “Bacterial type III effector protein HopQ inhibits melanoma motility through autophagic degradation of vimentin.” Cell Death Dis 11(4): 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekny M, Johansson CB, Eliasson C, Stakeberg J, Wallen A, Perlmann T, Lendahl U, Betsholtz C, Berthold CH and Frisen J (1999). “Abnormal reaction to central nervous system injury in mice lacking glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin.” J Cell Biol 145(3): 503–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sala D, Oeste CL, Martinez AE, Carrasco MJ, Garzon B and Canada FJ (2015). “Vimentin filament organization and stress sensing depend on its single cysteine residue and zinc binding.” Nat Commun 6: 7287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreau J, Lilienbaum A, Vasseur M and Paulin D (1988). “Nucleotide sequence of the human vimentin gene and regulation of its transcription in tissues and cultured cells.” Gene 62(1): 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peuhu E, Virtakoivu R, Mai A, Warri A and Ivaska J (2017). “Epithelial vimentin plays a functional role in mammary gland development.” Development 144(22): 4103–4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogel MR, Soni PN, Troken JR, Sitikov A, Trejo HE and Ridge KM (2011). “Vimentin is sufficient and required for wound repair and remodeling in alveolar epithelial cells.” FASEB J 25(11): 3873–3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Kapoor A, Zhu F, Mukhopadhyay R, Ghosh AK, Lee H, Mazzone J, Posner GH and Arav-Boger R (2020). “Artemisinins target the intermediate filament protein vimentin for human cytomegalovirus inhibition.” J Biol Chem 295(44): 15013–15028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudrabhatla P, Jaffe H and Pant HC (2011). “Direct evidence of phosphorylated neuronal intermediate filament proteins in neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs): phosphoproteomics of Alzheimer’s NFTs.” FASEB J 25(11): 3896–3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rujano MA, Bosveld F, Salomons FA, Dijk F, van Waarde MA, van der Want JJ, de Vos RA, Brunt ER, Sibon OC and Kampinga HH (2006). “Polarised asymmetric inheritance of accumulated protein damage in higher eukaryotes.” PLoS Biol 4(12): e417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runembert I, Couette S, Federici P, Colucci-Guyon E, Babinet C, Briand P, Friedlander G and Terzi F (2004). “Recovery of Na-glucose cotransport activity after renal ischemia is impaired in mice lacking vimentin.” Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287(5): F960–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffeld M, Herrmann H, Schultess J and Markl J (2001). “Vimentin and desmin of a cartilaginous fish, the shark Scyliorhinus stellaris: sequence, expression patterns and in vitro assembly.” Eur J Cell Biol 80(11): 692–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffers PM, Henrion D, Boulanger CM, Colucci-Guyon E, Langa-Vuves F, van Essen H, Fazzi GE, Levy BI and De Mey JG (2000). “Altered flow-induced arterial remodeling in vimentin-deficient mice.” Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20(3): 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Fan C and Jiu Y (2020). “Unidirectional Regulation of Vimentin Intermediate Filaments to Caveolin-1.” Int J Mol Sci 21(20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivalingappa PC, Hole R, Westphal CV and Vij N (2016). “Airway Exposure to E-Cigarette Vapors Impairs Autophagy and Induces Aggresome Formation.” Antioxid Redox Signal 24(4): 186–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven AC, Hainfeld JF, Trus BL, Wall JS and Steinert PM (1983). “The distribution of mass in heteropolymer intermediate filaments assembled in vitro. Stem analysis of vimentin/desmin and bovine epidermal keratin.” J Biol Chem 258(13): 8323–8329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JP, Tanaka F, Robitschek J, Sandoval CM, Taye A, Markovic-Plese S and Fischbeck KH (2003). “Aggresomes protect cells by enhancing the degradation of toxic polyglutamine-containing protein.” Hum Mol Genet 12(7): 749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzi F, Henrion D, Colucci-Guyon E, Federici P, Babinet C, Levy BI, Briand P and Friedlander G (1997). “Reduction of renal mass is lethal in mice lacking vimentin. Role of endothelin-nitric oxide imbalance.” J Clin Invest 100(6): 1520–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaudeau TA, Anderson RT and Smith DM (2018). “A common mechanism of proteasome impairment by neurodegenerative disease-associated oligomers.” Nat Commun 9(1): 1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolstonog GV, Shoeman RL, Traub U and Traub P (2001). “Role of the intermediate filament protein vimentin in delaying senescence and in the spontaneous immortalization of mouse embryo fibroblasts.” DNA Cell Biol 20(9): 509–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran I, Ji C, Ni I, Min T, Tang D and Vij N (2015). “Role of Cigarette Smoke-Induced Aggresome Formation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Emphysema Pathogenesis.” Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 53(2): 159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakhrusheva A, Endzhievskaya S, Zhuikov V, Nekrasova T, Parshina E, Ovsiannikova N, Popov V, Bagrov D, Minin Acapital A C and Sokolova OS (2019). “The role of vimentin in directional migration of rat fibroblasts.” Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 76(9–10): 467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Engeland NCA, Suarez Rodriguez F, Rivero-Muller A, Ristori T, Duran CL, Stassen O, Antfolk D, Driessen RCH, Ruohonen S, Ruohonen ST, Nuutinen S, Savontaus E, Loerakker S, Bayless KJ, Sjoqvist M, Bouten CVC, Eriksson JE and Sahlgren CM (2019). “Vimentin regulates Notch signaling strength and arterial remodeling in response to hemodynamic stress.” Sci Rep 9(1): 12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loosdregt I, Weissenberger G, van Maris M, Oomens CWJ, Loerakker S, Stassen O and Bouten CVC (2018). “The Mechanical Contribution of Vimentin to Cellular Stress Generation.” J Biomech Eng 140(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaboa NE, Garcia-Bermejo L, Perez C, de Blas E, Calle C and Aller P (1997). “Heat-shock and cadmium chloride increase the vimentin mRNA and protein levels in U-937 human promonocytic cells.” J Cell Sci 110 (Pt 2): 201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Bekar LK, Furber K and Walz W (2004). “Vimentin-expressing proximal reactive astrocytes correlate with migration rather than proliferation following focal brain injury.” Brain Research 1024(1–2): 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson U, Faiz M, de Pablo Y, Sjoqvist M, Andersson D, Widestrand A, Potokar M, Stenovec M, Smith PL, Shinjyo N, Pekny T, Zorec R, Stahlberg A, Pekna M, Sahlgren C and Pekny M (2012). “Astrocytes negatively regulate neurogenesis through the Jagged1-mediated Notch pathway.” Stem Cells 30(10): 2320–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong E and Cuervo AM (2010). “Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases.” Nat Neurosci 13(7): 805–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao HS, Xie Q, Zhong JY, Gerald Rukundo B, He XL, Qu YL and Cao H (2018). “[Effect of vimentin on activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in the brain of mice with EV71 infection].” Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 38(6): 704–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Gao Y, Zhan S, Xiong F, Qiu W, Qian X, Wang T, Wang N, Zhang D, Yang Q, Wang R, Bao X, Dou W, Tian R, Meng S, Gai WP, Huang Y, Yan XX, Ge W and Ma C (2016). “Quantitative protein profiling of hippocampus during human aging.” Neurobiol Aging 39: 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Graham K, Foote M, Liang F, Rizkallah R, Hurt M, Wang Y, Wu Y and Zhou Y (2013). “14-3-3 protein targets misfolded chaperone-associated proteins to aggresomes.” J Cell Sci 126(Pt 18): 4173–4186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]