Abstract

This study aimed to (1) identify generic questionnaires that measure self-management in people with chronic conditions, (2) describe their characteristics, (3) describe their development and theoretical foundations, and (4) identify categories of self-management strategies they assessed. This scoping review was based on the methodological framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley and completed by Levac et al. A thematic analysis was used to examine self-management strategies assessed by the questionnaires published between 1976 and 2019. A total of 21 articles on 10 generic, self-reported questionnaires were identified. The questionnaires were developed using various theoretical foundations. The Patient Assessment of Self-Management Tasks and Partners in Health scale questionnaires possessed characteristics that made them suitable for use in clinical and research settings and for evaluating all categories of self-management strategies. This study provides clinicians and researchers with an overview of generic, self-reported questionnaires and highlights some of their practical characteristics.

Keywords: chronic condition, questionnaire, scoping review, self-management, self-reported

Introduction

Chronic conditions (CCs) are the leading causes of mortality worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). One of the six objectives set out by the WHO (2013) for the prevention and control of CCs is to improve primary care services by supporting the self-management of people with CCs. Self-management “is the intrinsically controlled ability of an active, responsible, informed, and autonomous individual to live with the medical, role, and emotional consequences of his chronic condition(s) in partnership with his social network and the healthcare provider(s)” (Van de Velde et al., 2019). Based on the literature, this ability falls into one of the following four self-management strategy categories: behavioral/ medical, emotional, cognitive, and social (Grady & Gough, 2014; Miller et al., 2015; Schulman-Green et al., 2012; Unger & Buelow, 2009).

Up to the 2010s, the concept of self-management was often interchanged with related concepts, particularly the “self-care” concept described in the earlier literature (Grady & Gough, 2014). The distinction between self-management and self-care was only made in the last decade by Jones et al. (2011), who proposed that self-management is related to the management of CCs, while self-care is related to health and encompasses accident and disease prevention. Self-management was identified as a subset of self-care (Richard & Shea, 2011).

Problem

Self-management support for people affected by CCs can contribute to an improved quality of life and have a positive impact on the use of health services (Panagioti et al., 2014). In clinical settings, healthcare providers, including nurses, provide self-management support for people with CCs. Particularly in primary care, nurses could benefit from the use of questionnaires designed to document self-management in people with CCs, identify people who need self-management support, justify interventions and evaluate self-management intervention outcomes (Loretz, 2005). In this setting, nearly a quarter of patients have comorbidities (at least two CCs) (Luijks et al., 2016) and suffer from a wide range of CCs (Dain, 2018). Regardless of the type of CCs affecting them, sufferers face similar issues such as pain, fatigue, physical and mental health, and the deterioration of social functioning (Working Group on Health Outcomes for Older Persons with Multiple Chronic Conditions, 2012). It may thus be relevant for healthcare providers and researchers to use a generic questionnaire (Bryan et al., 2013) to get an overview of the practical self-management strategies used by people with CCs following self-management support interventions (Dineen-Griffin et al., 2019). Another advantage of using a generic questionnaire is its usefulness in measuring self-management in a person with more than one CC (Rutherford et al., 2019). Some studies demonstrated no significant differences between generic questionnaires and those focusing on specific conditions (Garster et al., 2009; Seow et al., 2019). Given the large number of available questionnaires on self-management, it can be difficult to select one for clinical or research purposes.

Three literature reviews have been published on self-management/self-care questionnaires. The first review concerning the concept of self-care, conducted by Sidani in 2003 and revised in 2011, aimed to identify self-care questionnaires without examining their theoretical foundations. The second is a scoping review by Matarese et al. (2017) on self-reported questionnaires used to assess self-care in healthy adults (i.e., not for people with CCs). The third, by Packer et al. (2017), is a scoping review on self-management questionnaires administered to adults with one or more CCs. The review covered the questionnaires, their definitions of self-management, their theoretical foundations, the reasons for their development, their target populations, the number of items they included and their dimensions. While the reviews identified 28 to 42 questionnaires on self-care and self-management developed between 1979 and 2015 (Matarese et al., 2017; Packer et al., 2017; Sidani, 2011), they did not focus on generic questionnaires.

To date, none of the literature provides any exhaustive list of generic self-management questionnaires for adults with CCs and the reviews fail to consider the theoretical foundations supporting these questionnaires. Practical characteristics (i.e., short and short item) (Tsang et al., 2017), theoretical foundations (Prinsen et al., 2016), and psychometric properties (i.e., Cronbach’s alpha demonstrating an acceptable level of reliability) (Morgado et al., 2017) can be relevant criteria in identifying the most suitable questionnaires. Therefore, for clinical and research purposes, it is advisable to obtain an overview of the generic questionnaires used to assess self-management in people with CCs.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to answer to following questions: (1) Do any generic, self-reported questionnaires that measure self-management among patients with CCs currently exist? (2) What are the questionnaires’ characteristics (i.e., length, item length, target population, target setting [research, clinical, or both], and psychometric qualities)? (3) What are the developmental and theoretical foundations of the questionnaires? (4) Which self-management strategy categories (behavioral/medical, cognitive/decision-making, emotional, and social) were measured by the instruments identified in this scoping review?

Methods

A scoping review was conducted, as this type of review is considered a “preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature” (Grant & Booth, 2009). This method allows for research questions to be answered by assessing the nature and extent of the literature without taking into account the quality criteria used to design the studies (Levac et al., 2010). It seems appropriate, given that our purpose was to identify a wide range of generic questionnaires.

We used the methodological framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and completed by Levac et al. (2010) to conduct a scoping review in five steps, that is, (1) identifying the research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

Identifying the Research Questions

Stemming from the need to identify generic questionnaires that can be used in clinical and research settings, our team, which included three clinician researchers, used an iterative process and demonstrated theoretical foundations to develop questions covering a wide range of self-management strategies.

Identifying Relevant Studies

We worked with an information specialist to develop a strategy for conducting an electronic search of the CINAHL, Embase and Medline databases for articles published between 1976 and 2019 in English or French. The strategy was developed around the main theme, self-management, and measure and related keywords were included in the search strategy to avoid missing any relevant questionnaires. Among other related concepts, self-efficacy (Richard & Shea, 2011) and patient activation (Hibbard et al., 2007) were excluded because they are considered an antecedent of self-management.

The following keywords and Boolean operators were used to find studies of interest in the databases:

CINAHL: AB ([measur* or tool* or questionnaire* or scale* or psychometr*] N6 [“self management” or “self-management” or “self-care” or “self care”]).

Embase: ([measure* or tool* or questionnaire* or scale* or psychometr*] adj6 [“self management” or “self-management” or “self-care” or “self care”]).ab.

Medline: AB ([measur* or tool* or questionnaire* or scale* or psychometr*] N6 [“self management” or “self-management” or “self-care” or “self care”]).

“AB” means that the strategy was limited to the abstract. “N6” OR “adj6” means that the concepts of self-management and measure must be within six words of one another. After several attempts, this proximity operator allowed us to identify the most relevant articles containing the targeted keywords in the same sentence and avoid noisy data (Elsevier, 2020).The asterisk means that the search includes all alternate endings after it. As previously explained, the term self-care was included during the literature search because the distinction between the two concepts (self-management and self-care) was only made about ten years ago (Jones et al., 2011; Richard & Shea, 2011).

Selecting Studies—Sample

Once the duplicates were eliminated (1,946 articles), 2,309 articles were screened by title and abstract, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, so that one of the research team members could exclude any clearly non-eligible articles. In case of uncertainty, the full articles were retrieved and read by a second team member. To be included, papers had to (1) be in French or English, (2) describe the development and/or validation of a self-reported questionnaire; (3) be designed to specifically measure the self-management or self-care of CCs, (4) be a generic questionnaire (i.e., not designed to measure self-management of a specific condition such as diabetes) as identified by the authors of the original questionnaires, and (5) focus on an adult population (18 or older). Papers concerning a questionnaire on a specific CC were excluded. A total of 296 articles were retained for detailed evaluation by two of the research team members.

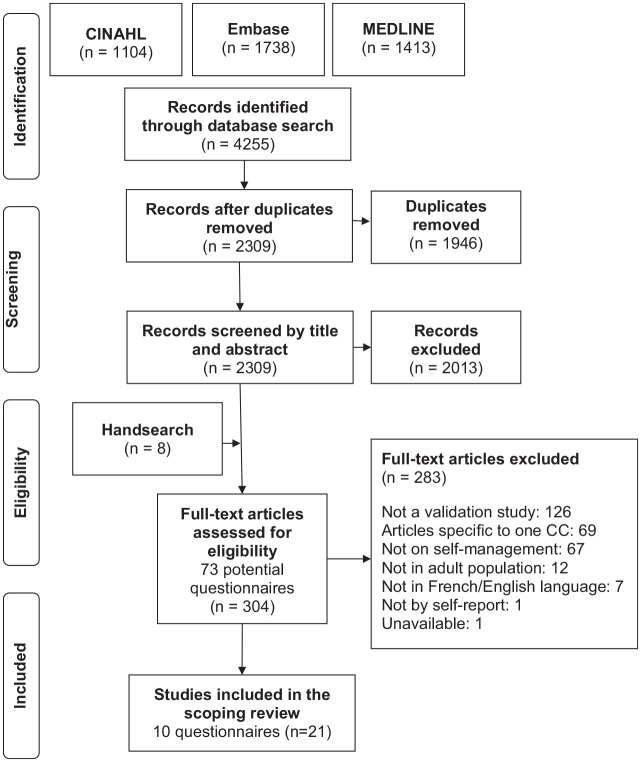

The reference list for each included article was used to search for other relevant articles (hand search). At this stage, the research team attempted to find the identified articles among available databases. The research team also contacted the primary authors to obtain more information on articles that were unavailable, or to obtain the questionnaires not included in the articles. This follow-up resulted in the identification of eight additional articles, all of which were examined by two team members and added to the list of selected articles. Thus, 21 articles describing ten different questionnaires were included in this scoping review, as shown in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram in Figure 1 (Moher et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the literature review process.

Note. CINAHL = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CC = Chronic condition.

Two questionnaires on self-care, that is, the Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale (ASAS) (Evers, 1989) and the Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale—Revised (ASAS-R) (Sousa et al., 2009), were included in this study because they measure psychometric properties among patients with CCs. They also contain items that measured self-management strategies corresponding to other questionnaires included in this review.

Charting the Data—Data Collection

Using an extraction grid, two review team members independently extracted the following information from the 21 articles: the name of the questionnaire and its abbreviation; authors; year of publication; language of publication; country of development; number of items in the original and revised versions; format for response options; Cronbach’s alpha of the original and revised versions; length; item length; target population; setting (research, clinical, or both); psychometric properties described; development stages; theoretical referents upon which the questionnaire was based; underlying constructs; definition of self-management; and dimensions/domains. Conflicts were resolved by consensus. For this article, we used the author names, year of publication, and country of development for each questionnaire that appeared in the first publication pertaining to it.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results—Data Analysis

The characteristics of the questionnaires are shown in Tables 1 to 3. The data was analyzed using the narrative analysis method (Lucas et al., 2007), which allows for transparent heterogeneity between questionnaires, as identified by Barnett-Page and Thomas (2009). Related studies (one to three per questionnaire) were grouped by questionnaire name. The definitions of self-management and/or other constructs on which the questionnaires were based were reviewed and summarized by two of the scoping review team members.

Table 1.

Questionnaires Measuring Self-Management and Their Origins.

| Name | Authors and year | Language | Country | Number of items in initial version (final version*) | Likert scale levels in initial version (final version*) | Cronbach’s alpha for questionnaire and range for dimensions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial version | Final version* | ||||||

| Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale (ASAS) | Evers (1989) | English | United States Netherlands | 24 (24) | 5 (5) | 0.76 | N/A |

| Dutch | N/A | 0.57–0.82 | |||||

| Van Achterberg et al. (1991) | Danish | ||||||

| Dutch | |||||||

| Norwegian | |||||||

| Söderhamn and Cliffordson (2001) | English | X | X | ||||

| Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised (ASAS-R) | Sousa et al. (2009) | English | United States | 24 (15) | 5 (5) | 0.89 | – |

| 0.79–0.86 | |||||||

| Health education impact Questionnaire (heiQ) | Osborne et al. (2006) | English | Australia | 42 (40) | 6 (4) | 0.86 | – |

| 0.70–0.89 | |||||||

| Patient Assessment of Self-Management Tasks (PAST) questionnaire | Van Houtum et al. (2014) | Dutch | Netherlands | 19 (15) | 4 (4) | N/A | – |

| 0.59–0.82 | |||||||

| Partners in Health (PIH) scale | Battersby et al. (2003) | English | Australia | 11 (12) | 9 (9) | 0.86 | 0.85 |

| Petkov et al. (2010) | English | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Battersby et al. (2015) | English | ||||||

| Smith et al. (2016) | English | X | X | ||||

| Kephart et al. (2019) | English | ||||||

| Perception of/Perceived Self-Care Agency Questionnaire (PS-CAQ) | Hanson (1981) | English | United States | 120 (53) | 5 (5) | 0.96 | – |

| 0.68–0.84 | |||||||

| Self-Management Ability Scale-30 (SMAS-30) | Schuurmans et al. (2005) | English | Netherlands | 30 | 6 | 0.91 | – |

| Cramm et al. (2012) | English | Netherlands | 0.67–0.83 | ||||

| Self-Management Ability Shorter-Scale (SMAS-S) | Cramm et al. (2012) | English | Netherlands | 18 | 6 | N/A | |

| 0.69–0.77 | |||||||

| Self-Management Screening (SeMaS) questionnaire | Eikelenboom et al. (2013) | Dutch | Netherlands | 27 (27) | 7 (4–5) | N/A | |

| Eikelenboom et al. (2015) | Dutch | 0.56–0.87 | |||||

| Eikelenboom et al. (2016) | Dutch | ||||||

| Therapeutic Self-Care (TSC) scale | Sidani and Doran (1999) | English | Canada | 13 (12) | 5 (7) | 0.89 | |

| Richard (2016) | English | 0.62–0.85 | |||||

Note. ASAS = Appraisal of Self-care Agency Scale; ASAS-R = Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised; heiQ = Health education impact Questionnaire; N/A = not available; PAST = Patient Assessment of Self-care Management Tasks; PIH = Partners in Health; PS-CAQ = Perception of/Perceived Self-Care Agency Questionnaire; SMAS-30 = Self-Management Ability Scale-30; SMAS-S = Self-Management Ability Shorter-Scale; SeMaS = Self-Management Screening; TSC = Therapeutic Self-Care.

Shown only if another version is available.

Table 3.

Categories of Self-Management Strategies Evaluated by the Items in the 10 Questionnaires.

| Questionnaire | Category | Behavioral/medical strategies | Cognitive/decision-making strategies | Emotional strategies | Social strategies | Not self-management strategies (functional capacity, hobbies and activities) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASAS (Evers, 1989) | X | X | X | |||

| ASAS-R (Sousa et al., 2009) | X | X | ||||

| heiQ (Osborne et al., 2006) | X | X | X | X | ||

| PAST (Van Houtum et al., 2014) | X | X | X | X | ||

| PIH (Battersby et al., 2003) | X | X | X | X | ||

| PS-CAQ (Hanson, 1981) | X | X | X | X | ||

| SMAS-30 (Schuurmans et al., 2005) | X | X | X | X | ||

| SMAS-S (Cramm et al., 2012) | X | X | X | X | ||

| SeMaS (Eikelenboom et al., 2013) | X | X | X | X | ||

| TSC (Sidani & Diane, 1999) | X | X | X | |||

Note. ASAS = Appraisal of Self-care Agency Scale; ASAS-R = Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised; heiQ = Health education impact Questionnaire; PAST = Patient Assessment of Self-care Management Tasks; PIH = Partners in Health; PS-CAQ = Perception of/Perceived Self-Care Agency Questionnaire; SMAS-30 = Self-Management Ability Scale-30; SMAS-S = Self-Management Ability Shorter-Scale; SeMaS = Self-Management Screening; TSC = Therapeutic Self-Care.

A thematic analysis (Vaismoradi et al., 2013) of all the items in each questionnaire was used to establish categories for the self-management strategies covered. The items were independently classified by two team members into one of the four strategy categories established by the analysis, that is, behavioral/medical, cognitive/decision-making, emotional, and social. These categories were based on Schulman-Green et al. (2012), Miller et al. (2015), and Unger and Buelow (2009), since in investigating the self-management concept, they identified strategies that people develop to manage their CCs. The categories are summarized as follows:

Behavioral/medical strategies: actions taken to manage the medical aspects of CCs (e.g., treatment adherence, monitoring/managing signs and symptoms) (Battersby et al., 2003; Sidani & Diane, 2014; Van Houtum et al., 2014) and to adopt/maintain healthy behaviors or new roles (Battersby et al., 2003; Eikelenboom et al., 2013; Sidani & Diane, 2014; Sousa et al., 2009; Van Houtum et al., 2014).

Cognitive/decision-making strategies: intellectual processes used for decision-making or to develop self-management skills (Evers, 1989; Jones et al., 2011; Osborne et al., 2006) and knowledge about CCs, medication, and treatment (Battersby et al., 2003).

Emotional strategies: processes used to adapt to or cope with the psychological consequences of CCs (Battersby et al., 2003; Eikelenboom et al., 2013; Van Houtum et al., 2014) by adopting a positive attitude (Osborne et al., 2006; Van Houtum et al., 2014).

Social strategies: processes used to adapt to or cope with the social consequences of CCs (Battersby et al., 2003; Eikelenboom et al., 2013; Van Houtum et al., 2014).

Items not corresponding to a self-management strategy were classified in a new category named Not self-management strategy. The team researchers then compared the results of the classification and discussed any differences of opinion or questions. Finally, the results were compiled into a summary of the self-management strategy categories.

Findings

This scoping review identified 21 articles on ten self-reported questionnaires measuring the self-management of people with a CC. Table 1 lists them in alphabetical order

Characteristics of Self-Management Questionnaires

In order of frequency, the countries of development were the Netherlands, the United States, Australia, and Canada. The oldest questionnaire was the Self-Care Agency Questionnaire, also called the Perception of Self-Care Agency Questionnaire (PS-CAQ) (Hanson, 1981) and the one most recently developed was Patient Assessment of Self-Management Tasks (PAST) (Van Houtum et al., 2014). The questionnaires encompassed 3 to 10 dimensions and all used Likert scales with 4 to 9 response options. Table 2 highlights the characteristics of all 10 questionnaires, that is: they were short (fewer than 25 items), they contained simple items (fewer than 20 words per item) (Burns et al., 2008; Passmore et al., 2002; Vaske, 2008) and the target population was made up exclusively of adults with CCs. According to the authors of the original articles, they were suitable for clinical (n = 8) or research (n = 4) use and their psychometric qualities were described. The Self-Management Ability Scale—30 (SMAS-30) and Self-Management Ability Scale—Shorter (SMAS-S) questionnaires were developed for people with CCs, with particular focus on the senior population (≥65 years) (Cramm et al., 2012; Schuurmans et al., 2005). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the questionnaires varied between 0.56 and 0.96. No coefficient was reported for two of the questionnaires (Cramm et al., 2012; Van Houtum et al., 2014).

Table 2.

Questionnaire Characteristics.

| Questionnaire | Characteristic | Length: short <25 items | Item length: simple items <20 words | Intended exclusively for adults with CCs | Usable in clinical settings according to authors | Usable in research settings according to authors | Psychometric properties described |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASAS (Evers, 1989) | X | X | X | ||||

| ASAS-R (Sousa et al., 2009) | X | X | X | X | |||

| heiQ (Osborne et al., 2006) | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| PAST (Van Houtum et al., 2014) | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| PIH (Battersby et al., 2003) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| PS-CAQ (Hanson, 1981) | X | X | X | ||||

| SMAS-30 (Schuurmans et al., 2005) | X | X | |||||

| SMAS-S (Cramm et al., 2012) | X | X | X | ||||

| SeMaS (Eikelenboom et al., 2013) | X | X | X | X | |||

| TSC (Sidani & Diane, 1999) | X | X | X | X | X | ||

Note. ASAS = Appraisal of Self-care Agency Scale; ASAS-R = Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised; CCs = chronic conditions; heiQ = Health education impact Questionnaire; PAST = Patient Assessment of Self-care Management Tasks; PIH = Partners in Health; PS-CAQ = Perception of/Perceived Self-Care Agency Questionnaire; SMAS-30 = Self-Management Ability Scale-30; SMAS-S = Self-Management Ability Shorter-Scale; SeMaS = Self-Management Screening; TSC = Therapeutic Self-Care.

Development and Theoretical Foundations

Questionnaire development

The authors of each questionnaire conducted a literature review on self-management, developed the questionnaire and the items in accordance with the dimensions of their theoretical foundation, and then validated it. The authors of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ) (Osborne et al., 2006) and the one on Self-Management Screening (SeMaS) (Eikelenboom et al., 2013) developed their own conceptual framework by consulting various experts (patients, health professionals, managers, and policymakers) and conducting focus groups and individual interviews to specify the final dimensions. Half the authors (Battersby et al., 2003; Eikelenboom et al., 2013; Osborne et al., 2006; Schuurmans et al., 2005; Van Houtum et al., 2014) developed their questionnaires by consulting people with CCs in a clinical setting or within the population.

Theoretical foundations and conceptualization of self-management

Supplemental Appendix 1, available online provides the questionnaires’ theoretical foundations, including theoretical referents and their main constructs and definitions, as well as their dimensions or domains. The following seven theoretical referents were identified: Orem’s Self-care Deficit Theory of Nursing (Evers, 1989; Hanson, 1981; Sidani & Diane, 2014; Sousa et al., 2009); the Program Logic Model for Patient Education (Osborne et al., 2006); the Theory of Stress and Coping (Van Houtum et al., 2014); self-management activities (Van Houtum et al., 2014); the Flinders Model (Battersby et al., 2003); the Theory of Successful Self-Management of Aging based on the Theory of Social Production Functions (Cramm et al., 2012; Schuurmans et al., 2005); and clarification of the difference between the concepts of self-care behavior and self-care ability (Sidani & Diane, 2014). The authors of the SeMaS did not refer to any theoretical referent (Eikelenboom et al., 2013). The definitions of self-management provided by the authors of the questionnaires varied and were most often guided by the theoretical model used.

The main constructs measured varied between questionnaires. They could be grouped into one of two main categories: self-care agency or self-management (tasks, abilities or strategies). All questionnaires measuring self-care agency were based on Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Theory of Nursing. Self-care agency corresponds to a person’s ability or capacity to meet his or her “continuing requirements for care that regulates life processes, maintains or promotes integrity of human structure and functioning and human development, and promotes well-being” or to perform self-care activities. Self-care agency can be considered an antecedent of self-management behaviors (Van de Velde et al., 2019). The dimensions identified by the authors of the questionnaires also varied and the names of some of them did not clearly represent what they were intended to measure (e.g., investment behavior or time ordering) (Cramm et al., 2012; Hanson, 1981; Schuurmans et al., 2005).

Evaluation of the Self-Management Strategies of People With CCs

Most items could be classified into one of the four categories of self-management strategies (Table 3). Some items evaluated more than one strategy, for example, “To maintain my hygiene, I adjust the frequency of bathing and showering to the circumstances” (Evers, 1989), to reflect behavioral/medical strategies and cognitive/decision-making strategies. The ASAS, ASAS-R, PS-CAQ, SMAS-30, SMAS-S, and TSC did not evaluate emotional strategies. The ASAS-R was the only questionnaire that did not evaluate social strategies. The other elements evaluated were functional capacity (flexibility) and recreation (hobbies, activities). The ASAS, ASAS-R, PS-CAQ, PIH, SeMaS, and TSC included items that specifically measured decision-making strategies. The PS-CAQ, SMAS-30, and SMAS-S included items categorized as not being part of a self-management strategy, as they were not related to self-management. It included activities, hobbies, work, and volunteering, for example, “My joints are flexible” (Hanson, 1981), or “Others benefit from the things I do for my pleasure” (Cramm et al., 2012; Schuurmans et al., 2005).

Discussion

This literature review aimed to identify generic questionnaires on self-management in people with CCs, describe the questionnaires’ characteristics, development and theoretical foundations, and identify questionnaires designed to assess the four main self-management strategy categories.

For the first purpose, the review identified ten questionnaires. Other reviews on self-management highlighted 4 to 6 generic questionnaires addressing self-management for adults in various settings but not specific to people with CCs (Matarese et al., 2017; Packer et al., 2017; Sidani, 2011).

For the second purpose, two of the questionnaires—the PAST and PIH—had all the desired characteristics (i.e., contained fewer than 25 items and fewer than 20 words per item, were intended for adults with CCs, were suitable for use by healthcare providers and described psychometrics properties). According its authors, the PIH could also be used for research purposes. These questionnaires were developed in collaboration with experts or population representatives. The PIH Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.86) was consistent with recommendations (Morgado et al., 2017). However, some PAST dimensions’ coefficients were under 0.70.

The questionnaires identified for the third purpose were based on seven theoretical foundations. Packer et al. (2017) identified theoretical foundations for five of the eight generic self-management questionnaires. Similarly, the theoretical foundations underpinning the generic questionnaires identified by Packer et al. (2017) were varied. Our review revealed that Orem’s Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory was most widely used as a theoretical referent, as demonstrated in Matarese et al. (2017). Our scoping review highlights the lack of consensus regarding the theoretical foundations of self-management.

For the last purpose, more than half the questionnaires did not evaluate all self-management strategy categories. Rather, the items they encompassed essentially measured behavioral/medical and cognitive/decision-making strategies. The heiQ, PAST, PIH, and SeMaS were the only questionnaires to address emotional aspects (anxiety, depression, and emotional well-being) and included all measured self-management strategies. What these four questionnaires had in common was that the authors involved patients in their development. Other questionnaires mainly measured behavioral/medical strategies and provided little information on emotional strategies. Van de Velde et al. (2019) previously reported that the literature on self-management provides more evidence on medical management and less on emotional. Packer et al. (2017) examined the strategies measured by some of the questionnaires using their taxonomy, which includes seven domains, based on a close examination of the items they contained. In our review, we also grouped questionnaire items into four self-management strategy categories based on a concept analysis (Miller et al., 2015; Unger & Buelow, 2009) and qualitative metasynthesis (Schulman-Green et al., 2012) of self-management in CCs, which shed light on a more practical point of view.

Theoretical Implications

Our review found that there is still no solid theoretical foundation for the generic measurement of self-management. This is due to the fact that there is no consensus on the definition of self-management, despite the fact that numerous studies of this concept have been conducted. For example, self-management attributes differed significantly between the concept analyses by Van de Velde et al. (2019), Udlis (2011), and Miller et al. (2015). The theoretical foundations used to develop the questionnaires appear to be varied and the lack of understanding of the difference between self-management and self-care (Grady & Gough, 2014) suggests that the self-management concept lacks maturity as it is still only partially developed (Morse et al., 2002) and requires further theoretical exploration. There is still a need for consensus on the definition of self-management and its theoretical foundation to support healthcare providers’ interventions and ensure that patients’ needs are met (Budhwani et al., 2019).

Strengths and Limitations

This study was conducted using the rigorous method developed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and completed by Levac et al. (2010). A more thorough search of the reference lists and communication with the authors allowed us to identify more questionnaires, even though they were not all selected for the study. The study involves a few limitations such as access to information. Some authors referred to unpublished works. The original articles on the development of three of the questionnaires (Evers, 1989; Hanson, 1981; Sidani, 2003) were over 20 years old, making it more difficult to contact the authors. Although this scoping review does not cover all the psychometric properties of each questionnaire, it is possible to compare the questionnaires based on the construct evaluated, dimensions included, number of items, number of studies validated the questionnaires, or Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency (Prinsen et al., 2016). In addition, some of the characteristics (i.e., generic questionnaire, target setting [research, clinical, or both]) were based on information from the original authors, who may not have included it in the original articles. In developing future questionnaires, it would be relevant to review the aspects measured by each item related to a self-management theoretical foundation to ensure an overall assessment of self-management.

Application

This scoping review constitutes a brief overview of generic self-management questionnaires having practical and theoretical characteristics that make them suitable for use by healthcare providers and researchers their clinical practice. Identifying the questionnaires that can be used by healthcare providers could guide them in their choice. Certain characteristics may further inform the selection of a specific questionnaire. For example, using a questionnaire containing as few statements as possible would reduce the time required to administer it in a clinical context and longer items may not be suitable for populations with a low degree of literacy. Lastly, though most questionnaires are unidimensional, healthcare providers could identify which dimensions they need to develop for self-management support interventions based upon the subdimensions in the questionnaire.

Conclusion

The scoping review identified 10 generic, self-reported questionnaires for people with CCs. Most of the questionnaires evaluated behavioral\medical strategies for the self-management of CCs. The PAST and PIH questionnaires were found to have certain clinically advantageous characteristics and evaluated all self-management strategy categories.

According to the original authors, most of the selected questionnaires can be used by healthcare providers to measure the patients’ initial level of self-management and thus, determine whether their self-management support interventions have had a beneficial impact. By using these questionnaires, healthcare providers obtain an overview of patients’ self-management support needs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cnr-10.1177_1054773820974149 for Generic Self-Reported Questionnaires Measuring Self-Management: A Scoping Review by Émilie Hudon, Catherine Hudon, Mireille Lambert, Mathieu Bisson and Maud-Christine Chouinard in Clinical Nursing Research

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the authors Bruno Damásio, PhD and Souraya Sidani, PhD, RN, to provided additional data. We would thank the specialist of information at the University of Sherbrooke Ms. Kathy Rose for helping us to elaborate the search strategy. Finally, we would like to thank Susie Bernier, Bonita Van Doorn and Patricia Hamilton for her help reviewing this paper.

Author Biographies

Émilie Hudon, MSc, RN, Doctoral student, Écoles des sciences infirmières, Faculté de médecine et des sciences de la santé, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada.

Catherine Hudon, PhD, MD, Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Faculté de médecine et des sciences de la santé, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada.

Mireille Lambert, MA, Research professional, V1SAGES Team, Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean, Chicoutimi, Quebec, Canada.

Mathieu Bisson, MA, Research professional, V1SAGES Team, Department of Family Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Faculté de médecine et des sciences de la santé, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada.

Maud-Christine Chouinard, PhD, RN Professor, Faculté des sciences infirmières, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Quebec, Canada.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Réseau de recherche en interventions en sciences infirmières du Québec. The first author was financially supported through her master’s scholarships by the Faculté de médecine et des sciences de la santé de l’Université de Sherbrooke (2017–2018), and the Fondation ma vie of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean (2016–2017). Sources of funding were not implied in the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent: This article was not produced using human or animal subjects.

ORCID iD: Émilie Hudon  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0735-5528

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0735-5528

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material (Appendix 1) for this article is available online.

References

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett-Page E., Thomas J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battersby M. W., Ask A., Reece M. M., Markwick M. J., Collins J. P. (2003). The partners in health scale: The development and psychometric properties of a generic assessment scale for chronic condition self-management. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 9(3), 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Battersby M., Harris M., Smith D., Reed R., Woodman R. (2015). A pragmatic randomized controlled trial of the flinders program of chronic condition management in community health care services. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(11), 1367–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan S., Broesch J., Dalzell K., Davis J., Dawes M., Doyle-Waters M. M., Lewis S., McGrail K., McGregor M. J., Murphy J. M. (2013). What are the most effective ways to measure patient health outcomes of primary health care integration through PROM (Patient Reported Outcome Measurement) instruments. Centre for Clinical Epidemiology & Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani S., Wodchis W. P., Zimmermann C., Moineddin R., Howell D. (2019). Self-management, self-management support needs and interventions in advanced cancer: A scoping review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 9(1), 12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns K. E., Duffett M., Kho M. E., Meade M. O., Adhikari N. K., Sinuff T., Cook D. J. (2008). A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 179(3), 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramm J. M., Strating M. M., de Vreede P. L., Steverink N., Nieboer A. P. (2012). Validation of the self-management ability scale (SMAS) and development and validation of a shorter scale (SMAS-S) among older patients shortly after hospitalisation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dain K. (2018). Challenges facing global health networks: The NCD alliance experience: Comment on “four challenges that global health networks face”. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 7(3), 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineen-Griffin S., Garcia-Cardenas V., Williams K., Benrimoj S. I. (2019). Helping patients help themselves: A systematic review of self-management support strategies in primary health care practice. PloS One, 14(8), e0220116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelenboom N., Smeele I., Faber M., Jacobs A., Verhulst F., Lacroix J., Wensing M., van Lieshout J. (2015). Validation of self-management screening (SeMaS), a tool to facilitate personalised counselling and support of patients with chronic diseases. BMC Family Practice, 16(165), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelenboom N., van Lieshout J., Jacobs A., Verhulst F., Lacroix J., van Halteren A., Klomp M., Smeele I., Wensing M. (2016). Effectiveness of personalised support for self-management in primary care: A cluster randomised controlled trial. British Journal of General Practice, 66(646), e354–e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikelenboom N., van Lieshout J., Wensing M., Smeele I., Jacobs A. E. (2013). Implementation of personalized self-management support using the self-management screening questionnaire SeMaS: A study protocol for a cluster randomized trial. Trials, 14(1), 336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsevier. (2020, April 29). How can I best use the Advanced search? https://service.elsevier.com/app/answers/detail/a_id/11365/supporthub/scopus/~/how-can-i-best-use-the-advanced-search%3F/

- Evers G. C. M. (1989). Appraisal of self-care agency A.S.A.-Scale. Van Gorcum. [Google Scholar]

- Garster N. C., Palta M., Sweitzer N. K., Kaplan R. M., Fryback D. G. (2009). Measuring health-related quality of life in population-based studies of coronary heart disease: Comparing six generic indexes and a disease-specific proxy score. Quality of Life Research, 18(9), 1239–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady P. A., Gough L. L. (2014). Self-management: A comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. American Journal of Public Health, 104(8), e25–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M. J., Booth A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson B. M. (1981). Development of a questionnaire measuring perception of self-care agency. University of Missouri. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard J. H., Mahoney E. R., Stock R., Tusler M. (2007). Self-management and health care utilization. Health Services Research, 42(4), 1443–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. C., MacGillivray S., Kroll T., Zohoor A. R., Connaghan J. (2011). A thematic analysis of the conceptualisation of self-care, self-management and self-management support in the long-term conditions management literature. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness, 3(3), 174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kephart G., Packer T. L., Audulv Å., Warner G. (2019). The structural and convergent validity of three commonly used measures of self-management in persons with neurological conditions. Quality of Life Research, 28(2), 545–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loretz L. (2005). Measurement tools and rating scale. In Loretz L. (Ed.), Primary care tools for clinicians: A compendium of forms, questionnaires, and rating scales for everyday practice (pp. 191–194). Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas P. J., Baird J., Arai L., Law C., Roberts H. M. (2007). Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7(1), 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luijks H. D., Lagro-Janssen A. L., van Weel C. (2016). Multimorbidity and the primary healthcare perspective. SAGE Publications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarese M., Lommi M., De Marinis M. G. (2017). Systematic review of measurement properties of self-reported instruments for evaluating self-care in adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(6), 1272–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R., Lasiter S., Bartlett Ellis R., Buelow J. M. (2015). Chronic disease self-management: A hybrid concept analysis. Nursing Outlook, 63(2), 154–161. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgado F., Meireles J., Neves C., Amaral A., Ferreira M. (2017). Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 30, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M., Hupcey J. E., Penrod J., Mitcham C. (2002). Integrating concepts for the development of qualitatively-derived theory. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 16(1), 5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne R. H., Elsworth G. R., Whitfield K. (2006). The Health education impact Questionnaire (heiQ): An outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions. Patient Education and Counseling, 66(2), 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer T. L., Fracini A., Audulv Å., Alizadeh N., van Gaal B. G., Warner G., Kephart G. (2017). What we know about the purpose, theoretical foundation, scope and dimensionality of existing self-management measurement tools: A scoping review. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(4), 579–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagioti M., Richardson G., Small N., Murray E., Rogers A., Kennedy A., Newman S., Bower P. (2014). Self-management support interventions to reduce health care utilisation without compromising outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore C., Dobbie A. E., Parchman M., Tysinger J. (2002). Guidelines for constructing a survey. Family Medicine, 34(4), 281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov J., Harvey P., Battersby M. (2010). The internal consistency and construct validity of the partners in health scale: Validation of a patient rated chronic condition self-management measure. Quality of Life Research, 19(7), 1079–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinsen C. A., Vohra S., Rose M. R., Boers M., Tugwell P., Clarke M., Williamson P. R., Terwee C. B. (2016). How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set”–a practical guideline. Trials, 17(1), 449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard A. A. (2016). Psychometric testing of the Sidani and Doran Therapeutic Self-Care Scale in a home health care population. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 24(1), 92–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard A. A., Shea K. (2011). Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 43(3), 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford C., Campbell R., Brown J. M., Smith I., Costa D. S., McGinnis E., Wilson L., Gilberts R., Brown S., Coleman S. (2019). Comparison of generic and disease-specific measures in their ability to detect differences in pressure ulcer clinical groups. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 27(4), 396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman-Green D., Jaser S., Martin F., Alonzo A., Grey M., McCorkle R., Redeker N. S., Reynolds N., Whittemore R. (2012). Processes of self-management in chronic illness. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 44(2), 136–144. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01444.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurmans H., Steverink N., Frieswijk N., Buunk B. P., Slaets J. P., Lindenberg S. (2005). How to measure self-management abilities in older people by self-report: The development of the SMAS-30. Quality of Life Research, 14(10), 2215–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow L. S. E., Tan T. H. G., Abdin E., Chong S. A., Subramaniam M. (2019). Comparing disease-specific and generic quality of life measures in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 273, 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidani S. (2003). Self-Care. In Doran D. (Ed.), Nursing-sensitive outcomes: State of the science (1st ed., pp. 65–113). Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Sidani S. (2011). Self-Care. In Doran D. (Ed.), Nursing outcomes: The state of the science (2nd ed., p. xiv, 522). Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Sidani S., Diane I. D. (1999). Evaluation of the care delivery model and staff mix redesign initiative: The collaborative care study. Unpublished report.

- Sidani S., Diane I. D. (2014). Development and validation of a self-care ability measure. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 46(1), 11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D., Harvey P., Lawn S., Harris M., Battersby M. (2016). Measuring chronic condition self-management in an Australian community: Factor structure of the revised Partners in Health (PIH) scale. Quality of Life Research, 26(1), 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderhamn O., Cliffordson C. (2001). The internal structure of the Appraisal of Self-care Agency (ASA) Scale. Nursing Science, 10(4), 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa V. D., Zauszniewski J. A., Bergquist-Beringer S., Musil C. M., Neese J. B., Jaber A. F. (2009). Reliability, validity and factor structure of the Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised (ASAS-R). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16(6), 1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang S., Royse C. F., Terkawi A. S. (2017). Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 11(Suppl. 1), S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udlis K. A. (2011). Self-management in chronic illness: Concept and dimensional analysis. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness, 3(2), 130–139. 10.1111/j.1752-9824.2011.01085.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Unger W. R., Buelow J. M. (2009). Hybrid concept analysis of self-management in adults newly diagnosed with epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior, 14(1), 89–95. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi M., Turunen H., Bondas T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Achterberg T., Lorensen M., Isenberg M. A., Evers G. C., Levin E., Philipsen H. (1991). The Norwegian, Danish and Dutch version of the appraisal of self-care agency scale; Comparing reliability aspects. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 5(2),101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Velde D., De Zutter F., Satink T., Costa U., Janquart S., Senn D., De Vriendt P. (2019). Delineating the concept of self-management in chronic conditions: A concept analysis. BMJ Open, 9(7), e027775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtum L., Rijken M., Heijmans M., Groenewegen P. (2014). Patient-perceived self-management tasks and support needs of people with chronic illness: Generic or disease specific? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49(2), 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaske J. J. (2008). Survey research and analysis: Applications in parks, recreation and human dimensions. Venture Publishing State College. [Google Scholar]

- Working Group on Health Outcomes for Older Persons with Multiple Chronic Conditions. (2012). Universal health outcome measures for older persons with multiple chronic conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(12), 2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013). Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013-2020. https://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/

- World Health Organization. (2017). Top 10 causes of death worldwide. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cnr-10.1177_1054773820974149 for Generic Self-Reported Questionnaires Measuring Self-Management: A Scoping Review by Émilie Hudon, Catherine Hudon, Mireille Lambert, Mathieu Bisson and Maud-Christine Chouinard in Clinical Nursing Research