After intrauterine device placement for emergency contraception, pregnancy risk remains low, regardless of the timing or frequency of unprotected intercourse episodes in the prior 14 days.

Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To assess pregnancy risk after intrauterine device (IUD) placement by the number and timing of unprotected intercourse episodes in the prior 14 days.

METHODS:

This was a secondary analysis of a randomized trial that compared the copper T380A IUD and levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system for emergency contraception. At enrollment, participants had a negative urine pregnancy test result and reported the frequency and timing of any unprotected intercourse in the preceding 14 days. We assessed pregnancies 1 month after IUD placement and compared pregnancy risk by single or multiple unprotected intercourse episodes and by timing (5 or fewer days before IUD placement or 6 or more days before).

RESULTS:

Among the 655 participants, one pregnancy occurred in a patient who reported intercourse once 48 hours before IUD placement. Multiple unprotected intercourse episodes were reported by 286 participants (43.7%), and 95 participants (14.4%) reported at least one unprotected intercourse episode 6 or more days before IUD placement. No pregnancies occurred among those with multiple unprotected intercourse episodes (0%, 97.5% CI 0–1.3%) or with any unprotected intercourse episode 6–14 days before IUD placement (0.0%, 97.5% CI 0.0–3.8%). Pregnancy risk difference did not significantly differ by single compared with multiple unprotected intercourse episodes (0.3%, 95% CI −0.3% to 0.8%), nor by unprotected intercourse 5 or fewer days before IUD placement or 6 or more days before (0.2%, 95% CI −0.2% to 0.5%).

CONCLUSION:

With a negative urine pregnancy test result at IUD placement, 1-month pregnancy risk remains low, regardless of frequency or timing of unprotected intercourse in the prior 14 days.

Clinical Trial Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02175030.

Many people engage in multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse before presenting for emergency contraception,1 including episodes that occur beyond the current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization guidelines of 5 days.2,3 The standard research practice for emergency contraception efficacy studies is to limit participation to only those with a single episode of unprotected intercourse in the prior 5 days.4,5 As such, we lack data on situations in which multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse occurred in the same menstrual cycle of use, especially episodes occurring more than 5 days before emergency contraception use. Therefore, we have used data from a recent randomized clinical trial of 655 participants receiving emergency contraception who were assigned to either the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system (IUS) or the copper T380 intrauterine device (IUD) to assess pregnancy risk based on the number and timing of unprotected intercourse episodes in the 14 days before IUD placement.6

METHODS

We conducted this study as a secondary analysis of a noninferiority randomized control trial that assessed the emergency contraception efficacy of the levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS and the copper T380A IUD. Study methodology details including inclusion and exclusion criteria are published elsewhere.6 We enrolled participants at one of six family planning clinics in Utah between August 2016 and December 2019. The original study included people aged 18–35 years who had at least one unprotected intercourse episode 5 days before enrollment, normal menstrual cycle lengths (21–35 days), and knew their last menstrual period (±3 days). All had a negative urine pregnancy test result (human chorionic gonadotropin level of 20 international units/L or less) immediately before IUD placement. Trained study staff obtained informed consent from all participants before enrollment. Skilled clinicians placed either the levonorgestrel IUS or the copper IUD.

On enrollment, we queried participants, “How many times in the last 2 weeks have you had sex when a method of birth control was not used or you were worried that the method you used did not work?” Using a calendar, participants then identified which of the prior 14 days they had sex either “with no method of birth control,” or “used a method where you were worried you might get pregnant (for example a broken condom, missed birth control pills, etc.).” Participants provided this information as a component of their study enrollment data. This information was not provided to clinicians, and participants were not informed that emergency contraception would not protect against pregnancy from intercourse occurring more than 5 days before IUD placement. We defined frequency of unprotected intercourse episodes as the sum of responses to these two categories. One month after IUD placement, participants reported pregnancy results by at least one of the following: self-administered home urine pregnancy test; an in-clinic urine pregnancy test or phone or web-based electronic data capture indicating no signs of pregnancy, including pregnancy test results; ultrasonography findings; report of normal menstrual cycle; and continuation of IUD use.

As detailed in the manuscript detailing the primary outcome of the parent study, we modified the protocol to add electronic health record review for participants who did not report pregnancy results by any of these methods. In those cases, we conducted an in-depth medical chart review and reviewed participant follow-up surveys from 1, 3, and 6 months after IUD placement to assess evidence of a possible pregnancy occurring in the first month of use. For this analysis we included participants from the main study who received an IUD after randomization and provided 1-month pregnancy outcome data. For this analysis, we aggregated participants from both groups into a single cohort because the levonorgestrel IUS was found to be noninferior to the copper IUD in the parent trial.

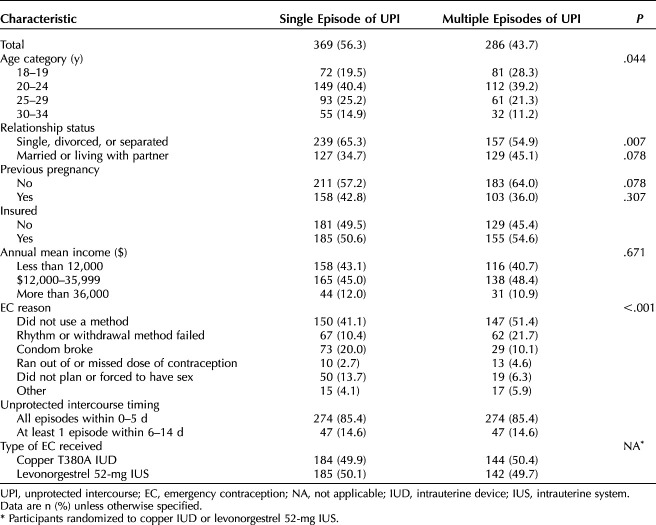

We calculated descriptive statistics for participant demographic characteristics by those reporting single compared with multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse. We compared baseline characteristics between the groups using χ2 tests and calculated the number of unprotected intercourse episodes in the 14 days before IUD placement. For the full complement of participants who received an IUD (either type), we compared pregnancy risk between those reporting single compared with multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse. We then compared pregnancy risk by those with unprotected intercourse only within the first 5 days before IUD placement compared with those with unprotected intercourse 6–14 days before IUD placement, as well as pregnancy risk by those with at least one episode at 6–7, 6–10, and 6–14 days before IUD placement. These data are presented to identify the frequency of these occurrences among IUD emergency contraception users and to potentially inform an expansion of the IUD emergency contraception efficacy window.

We split the time ranges of unprotected intercourse episodes into two categories, 0–5 days and 6–14 days, because current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical guidelines limit IUD placement for emergency contraception to within 5 days from of unprotected intercourse. Based on menstrual cycle information participants provided at enrollment, we calculated the fertile window for the menstrual cycle of study IUD placement. We identified the likely day of next expected menses by adding the usual menstrual cycle length in days to the date of the reported first day of the last menstrual period. From this date we subtracted 14 to estimate the day of ovulation. The fertile window was identified as the period from 5 days before the day of ovulation to 1 day after. We then identified all the episodes of unprotected intercourse that occurred in this window and report them by whether any occurred in the 0–5 days or 6–14 days before IUD placement. We calculated pregnancy rate point estimates with 95% CIs using Clopper-Pearson binomial exact CI. We conducted all statistical analyses using Stata 16. The University of Utah Institutional Review Board approved the study.

RESULTS

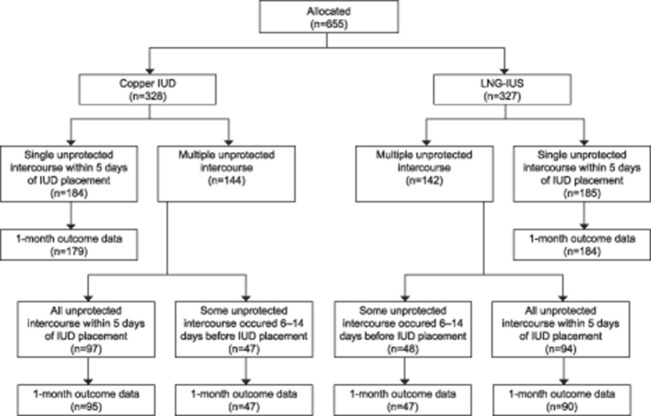

Six hundred fifty-five participants from the parent study met the inclusion criteria, received an IUD for emergency contraception, and provided 1-month pregnancy outcome data for this analysis (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Those in the multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse group were younger, more likely to be unmarried and cohabitating, and more likely to have used emergency contraception because they had not used a method of contraception. The one study pregnancy occurred in a participant reporting a single episode of unprotected intercourse 48 hours before IUD placement.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Figure 1. Participant flow chart and 1-month pregnancy outcomes for study participants with emergency contraception intrauterine device (IUD) placement, by single vs multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse in the 14 days before IUD placement. LNG-IUS, levonorgestrel intrauterine system.

BakenRa. Pregnancy Risk and Unprotected Intercourse for IUD Insertion. Obstet Gynecol 2021.

Multiple unprotected intercourse episodes were reported by 286 participants (43.7%), and 95 participants (14.4%) reported at least one unprotected intercourse episode 6 or more days before IUD placement. Participants who reported multiple unprotected intercourse episodes reported a median of three unprotected intercourse episodes. At 1 month, we lost 1.8% of participants to follow-up (n=12) and 0.2% for early withdrawal (n=1).

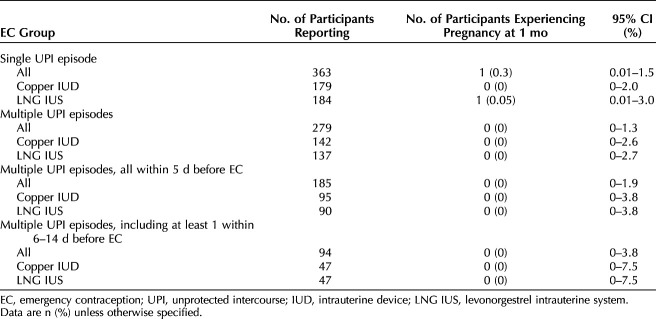

Pregnancy risk did not significantly differ by single compared with multiple unprotected intercourse episodes (risk difference 0.3%, 95% CI −0.3 to 0.8). No pregnancies occurred among those who reported multiple unprotected intercourse episodes (0%, 97.5% CI 0–1.3%) or with an unprotected intercourse episode 6–14 days before IUD placement (0.0%, 97.5% CI 0.0–3.8%). Pregnancy risk was similar between those reporting unprotected intercourse only within the 5 days before IUD placement compared with those reporting unprotected intercourse 6–14 days before (risk difference 0.2%, 95% CI −0.2 to 0.5) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pregnancy Risk by Intrauterine Device Emergency Contraception Treatment Type and History of Recent Unprotected Intercourse

No pregnancies occurred among participants with additional unprotected intercourse episodes 6–7 days before IUD placement (n=59) (0%, 97.5% CI 0–6.1%), 6–10 days before (n=86) (0%, 97.5% CI 0–4.2%), or 6–14 days before (n=95) (0%, 97.5% CI 0–3.8%). Among the 642 women with 1-month outcome data, 187 (29.1%) were in their fertile window at the time of at least one of their reported unprotected intercourse events. Among those allocated to the copper IUD, 65 (67.7%) women reported that all fertile-window unprotected intercourse events occurred in the 5 days preceding IUD placement, and 31 (32.3%) reported that at least one unprotected intercourse episode occurred 6–14 days before enrollment. The corresponding numbers for those allocated to the levonorgestrel IUS, were 67 (73.6%) in the previous 5 days, and 24 (26.4%) 6–14 days before enrollment.

DISCUSSION

We found a low probability of pregnancy, regardless of the frequency or timing of unprotected intercourse episodes in the 14 days before IUD placement. Among people seeking emergency contraception from clinics and obtaining an IUD, 4 out of 10 participants reported multiple recent episodes of unprotected intercourse, including episodes 6–14 days before the IUD placement. All participants had a negative urine pregnancy test result at the time of IUD placement, and this is an important caveat for future clinical care.

Prior randomized trials assessing emergency contraception efficacy rarely have quantified the frequency of unprotected intercourse exposure and have not assessed efficacy for oral emergency contraception beyond 5 days after unprotected intercourse. One randomized controlled trial with 2,221 participants compared oral levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception and reported the proportion with multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse. They found that 11% of participants reported more than one episode of unprotected intercourse before emergency contraception use,7 approximately one quarter of the proportion reporting this outcome in our trial. In the current study considering 14 days before IUD placement, greater time between unprotected intercourse and IUD placement does not appear to affect pregnancy risk, though we have a small proportion of participants reporting unprotected intercourse beyond 5 days before IUD placement, including only eight participants reporting unprotected intercourse 11–14 days before. Although we lack definitive data assessing a decrease in efficacy with oral emergency contraception after multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse, with IUDs we can affirm multiple exposures do not seem to increase pregnancy risk. For these situations with multiple unprotected intercourse episodes and extended time between unprotected intercourse and emergency contraception request, potential users should be informed of the evidence of IUD emergency contraception efficacy, compared with the current state of uncertain data for oral emergency contraception methods. Recent manuscripts with data contributed from this study report more precise one-month pregnancy risk estimates with copper and levonorgestrel IUDs placed 6-14 days after unprotected intercourse.8,9

Study strengths supporting internal validity include the relatively large sample and the prospective assessment of pregnancy risk given unprotected intercourse exposure before treatment in the setting of a randomized controlled trial. The inclusion of emergency contraception users randomly assigned to either a copper T380A or the levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS provides point estimates for both types of IUDs for the exposures. The study population was at high risk of pregnancy. Of note, the multiple unprotected intercourse group further augmented their pregnancy risk because of greater representation with lower age groups, associated with higher fertility rates.

Study weaknesses include report of outcomes for which we did not specifically power the trial. Certain assessment categories lack power for rigorous analysis. Because only one pregnancy was reported in the first month of IUD use, there is little power to compare differences in pregnancy rates by timing or frequency of unprotected intercourse. For some participants (n=48, 7.5% of the study population) we lack 4-week urine pregnancy test results, though we compensated for this by obtaining additional data from follow-up surveys and by assessing the clinic electronic health record. The recruitment of clinic sites only in Utah limits external validity. Underreporting of unprotected intercourse may bias the results to overestimate the risk of pregnancy; however, this is similar to a prior IUD emergency contraception study in one of these six clinics, which showed the same proportion (43%) of participants reporting multiple episodes of unprotected intercourse in the 14 days before IUD placement.1

This secondary analysis informs specific clinical situations that can limit contraceptive access, especially for people requesting IUD placement and reporting unprotected intercourse 6–14 days before placement. It is worth noting that the Canadian emergency contraception guidelines already support use of the copper IUD out to 7 days from unprotected intercourse.10 No pregnancies occurring in the 94 participants who reported unprotected intercourse 6–14 days before IUD placement provides a point estimate and CI for this risk (0%, 97.5% CI 0–3.8%). This is further strengthened by the comparison of the pregnancy risk in this situation to those who only reported unprotected intercourse within 5 days of IUD placement (0.2%, 95% CI −0.2 to 0.5). Sharing this information with clients allows them to make the decision that is right for them. These data help health care professionals and IUD users place an IUD anytime, regardless of recent unprotected intercourse when a pregnancy test result is negative. Given the multitude of barriers that may impede timely presentation to care (insurance and cost concerns, difficulty finding a capable health care professional, or sexual assault trauma), these data are critical to patient-centered family planning care.

These data demonstrate that regardless of frequency and timing of unprotected intercourse within the 14 days preceding IUD placement, the risk of pregnancy is low. Applying these data to clinical care may significantly improve contraceptive access.

Authors' Data Sharing Statement

Will individual participant data be available (including data dictionaries)? Yes.

What data in particular will be shared? Data in Table 1 and pregnancy outcomes.

What other documents will be available? The main study protocol and data analysis plan.

When will data be available (start and end dates)? One year following publication.

Will individual participant data be available (including data dictionaries)? Yes. By what access criteria will data be shared (including with whom, for what types of analyses, and by what mechanism)? By researcher request to the authors.

Footnotes

This project is funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R01HD083340). Additional support came by the University of Utah Population Health Research Foundation, with funding, in part, from the National Center for Research Resources, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant UL1TR002538 (formerly 5UL1TR001067-05, 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764). Use of REDCap was provided by 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764) NCATS/NIH. Team members receive support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Office of Research on Women's Health of the National Institutes of Health via award no. K12HD085852 (J.S.) and award no. K24HD087436 (D.T.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of any of the funding agencies or participating institutions, including the National Institutes of Health, the University of Utah, or Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc.

Financial Disclosure The Division of Family Planning in the University of Utah's Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology receives research funding from Bayer Women's Health Care, Merck & Co. Inc., Cooper Surgical, Sebela Pharmaceuticals, Femasys, and Medicines 360. Rebecca Simmons did a short, 1-week consultancy with a fertility tech company in January 2020 for which she received compensation. David Turok serves as a consultant for Sebela Pharmaceuticals and the national principal investigator for FDA trials of two IUDs. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Planned Parenthood Association of Utah for exceptional patient care and recruitment of participants into this study, especially Penny Davies. The authors also thank Marie Gibson for managing regulatory issues, and Corinne Sexsmith and Indigo Mason for conducting follow-up. The contraceptive products for the project were purchased from the distributors.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal's requirements for authorship.

Peer reviews and author correspondence are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/C341.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanders JN, Howell L, Saltzman HM, Schwarz EB, Thompson IS, Turok DK. Unprotected intercourse in the 2 weeks prior to requesting emergency intrauterine contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:592.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65:1–103. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 5th ed. World Health Organization; 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer DF, Wan L, Frezieres R, Thomas M, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:1089–97. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000239440.02284.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding JH, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2002;360:1803–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11767-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turok DK, Gero A, Simmons RG, et al. The levonorgestrel vs. Copper intrauterine device for emergency contraception. N Engl J Med 2021;384:335–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, Logan SJ, Casale W, Van Horn J, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375:555–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson I, Sanders JN, Schwarz EB, Boraas C, Turok DK. Copper intrauterine device placement 6-14 days after unprotected sex. Contraception 2019;100:219–21. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boraas CM, Sanders JN, Schwarz EB, Thompson IS, Turok DK. Risk of pregnancy with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system placement 6-14 days after unprotected sexual intercourse. Obstet Gynecol 2021;137:623–5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black A, Guilbert E, Co A, Costescu D, Dunn S, Fisher W, et al. Canadian contraception consensus (Part 1 of 4). J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37:936–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60101-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]