Visual Abstract

Keywords: acute kidney injury, dialysis, ESRD, mortality risk, outcomes

Abstract

Background and objectives

About 30% of patients with AKI may require ongoing dialysis in the outpatient setting after hospital discharge. A 2017 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services policy change allows Medicare beneficiaries with AKI requiring dialysis to receive outpatient treatment in dialysis facilities. Outcomes for these patients have not been reported. We compare patient characteristics and mortality among patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We used a retrospective cohort design with 2017 Medicare claims to follow outpatients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis up to 365 days. Outcomes are unadjusted and adjusted mortality using Kaplan–Meier estimation for unadjusted survival probability, Poisson regression for monthly mortality, and Cox proportional hazards modeling for adjusted mortality.

Results

In total, 10,821 of 401,973 (3%) Medicare patients requiring dialysis had at least one AKI claim, and 52,626 patients were Medicare patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis. Patients with AKI requiring dialysis were more likely to be White (76% versus 70%), non-Hispanic (92% versus 87%), and age 60 or older (82% versus 72%) compared with patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis. Unadjusted mortality was markedly higher for patients with AKI requiring dialysis compared with patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis. Adjusted mortality differences between both cohorts persisted through month 4 of the follow-up period (all P=0.01), then, they declined and were no longer statistically significant. Adjusted monthly mortality stratified by Black and other race between patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis was lower throughout month 4 (1.5 versus 0.60, 1.20 versus 0.84, 1.00 versus 0.80, and 0.95 versus 0.74; all P<0.001), which persisted through month 7. Overall adjusted mortality risk was 22% higher for patients with AKI requiring dialysis (1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.17 to 1.27).

Conclusions

In fully adjusted analyses, patients with AKI requiring dialysis had higher early mortality compared with patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis, but these differences declined after several months. Differences were also observed by age, race, and ethnicity within both patient cohorts.

Introduction

Recent studies indicate improved inpatient survival for patients with AKI who require dialysis and that up to 30% may require ongoing hemodialysis in the outpatient setting after hospital discharge. However, outcomes still remain poor for many patients with AKI requiring dialysis (1–6). Patients with AKI requiring dialysis represent a more acutely ill population that is typically older and has a higher prevalence of chronic conditions associated with hospitalizations (7, 8). Prognosis for recovery of kidney function after hospital discharge for patients with AKI requiring dialysis has been poor, typically in the range of only 25%–30%, particularly for those patients with other coexisting conditions (2, 9–12).

Because of a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) policy change in 2017, Medicare beneficiaries with AKI requiring dialysis became eligible to receive treatment in outpatient dialysis facilities (13). To date, there is no CMS regulatory requirement for data reporting on clinical indicators for patients with AKI requiring dialysis, and there are no AKI-specific quality metrics assessing outcomes for patients with AKI receiving dialysis in an outpatient facility. As a result, the number of patients with AKI requiring dialysis receiving treatment in outpatient facilities since this policy change has not been reported. Furthermore, outcomes of patients with AKI requiring dialysis relative to patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis receiving treatment in an outpatient facility remain incompletely documented and are not well understood, given the prior payment policies in place before 2017. We describe the clinical and patient characteristics of patients with AKI receiving outpatient dialysis and patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis and compare differences in unadjusted and adjusted mortality between these patient cohorts over a 1-year follow-up period using 2017 Medicare data. We test whether mortality is similar between both patient cohorts.

Materials and Methods

Data and Study Population

We use Medicare outpatient claims bill type 072X (dialysis claims) to identify patients receiving outpatient dialysis in Medicare dialysis facilities in calendar year 2017 (Figure 1). Patients with AKI requiring dialysis were identified as those who had at least one bill type 072X claim with condition code 84 (dialysis for AKI), CPT G0491 (dialysis for AKI without ESKD), or one of the following ICD-10 codes defining AKI on the outpatient dialysis claim: N17.0 (acute kidney failure with tubular necrosis), N17.1 (acute kidney failure acute cortical necrosis), N17.2 (acute kidney failure with medullary necrosis), N17.8 (other acute kidney failure), N17.9 (acute kidney failure, unspecified), T79.5XXA (traumatic anuria, initial encounter), T79.5XXD (traumatic anuria, subsequent encounter), T79.5XXS (traumatic anuria, sequela), or N99.0 (postprocedural [acute, chronic] renal failure). Patients on incident dialysis were identified as those who did not have any AKI claims and had their date of kidney failure in 2017. Patients with AKI requiring dialysis who did not recover and developed kidney failure remained classified as AKI for the duration of follow-up in our study. This allowed for a more direct comparison that is less subject to crosscontamination between the two patient cohorts during the follow-up period. Patients with any Medicare Advantage coverage during 2017 were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Enrollment flow chart of patients from Medicare outpatient dialysis claims. CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Patient characteristics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, date of maintenance dialysis certification, and modality) for patients requiring incident dialysis were obtained from CROWNWeb and the Medical Evidence Form (CMS Form 2728). Patient characteristics (age, race, sex, and ethnicity) for patients with AKI requiring dialysis were obtained from the CMS Enrollment Database (EDB). Prevalent comorbidities were derived from Medicare claims in the 365 days prior to the first day of the first AKI claim in 2017 for patients with AKI requiring dialysis and 365 days prior to the first date of certified kidney failure on the CMS Form 2728 in 2017 for patients requiring incident dialysis. Comorbidities were grouped into clinical categories using the fiscal year 2015 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification Software single-level diagnoses groupers (14). Vital status was obtained from the Medicare EDB, which includes event data from the Social Security Death Master File. Recovery of kidney function for patients with AKI requiring dialysis was defined as meeting all of these criteria during the study period: no submission of CMS Form 2728 indicating need for maintenance dialysis but appearing in EDB, discontinuation of dialysis as evidenced by no further dialysis claims submission, no evidence of death, and no evidence of receipt of a kidney transplant. For patients with incident kidney failure, recovery is defined as recovery reported by the dialysis facility.

We used a retrospective cohort design. Patients were followed up to 365 days from either the start of the first AKI claim (for patients with AKI requiring dialysis) or the first date of kidney failure certification (for patients requiring incident dialysis). Follow-up was not censored at transplant or recovery of kidney function.

This study is on the basis of work performed for CMS under contract to support quality monitoring and CMS oversight programs; it is, therefore, institutional review board exempt and waived from HIPPA requirements for informed consent.

Methods and Analyses

Calculation of unadjusted and adjusted monthly mortality rates determined patient’s duration at risk on the basis of the total number of days between the start of dialysis and the earlier of death or censoring. For example, if a certain patient died 62 days after the first outpatient dialysis treatment, then the time period is partitioned with monthly at-risk duration being 31, 28, and 3 days, and only the third month leads to a death event. After transforming the data, unadjusted monthly mortality (per 1000 patients) can be readily calculated as the number of deaths divided by the sum of the number of days at risk of all at-risk patients within a certain month period and then multiplied by 1000. To calculate adjusted monthly mortality, we fit a Poisson regression model adjusting for age, race, sex, diabetes, and 41 prevalent comorbidities and including the log of at-risk days in a month as offset. The resulting parameter estimates are then applied to the entire study population to estimate patient-level mortalities by direct standardization, and their average is the adjusted monthly mortality. All analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and R (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Of the 401,973 Medicare patients with dialysis claims, 3% (10,821 patients) had at least one AKI claim during 2017, and 13% (52,626 patients) were patients requiring incident dialysis. Patients with AKI requiring dialysis were more likely to be White (76% versus 70% patients requiring incident dialysis), non-Hispanic (92% versus 87%, respectively), and age 60 or greater (82% versus 72%, respectively) compared with patients requiring incident dialysis (Table 1). The frequencies of the more common prevalent comorbidities, defined as 5% or higher, for the respective patient cohorts are reported in Table 2. Patients with AKI requiring dialysis had approximately 60% more of the most frequent comorbidities relative to patients requiring incident dialysis and at least a 10-percentage point–higher prevalence of several current comorbidities, including diabetes, respiratory failure, atrial fibrillation, and COPD. Among all patients requiring incident dialysis in the study, 977 (10%) had “acute kidney failure” listed as the cause of kidney failure on their CMS Form 2728.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients without AKI on incident dialysis in 2017

| COLUMN HEADING | Patients with AKI Requiring Dialysis, n=10,821 | Patients on Incident Dialysis, n=52,626 | Total Patients, n=63,447 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age on January 1, 2017, yr | |||

| <18 | 20 (0.2) | 135 (0.3) | 155 |

| 18 to <25 | 27 (0.3) | 262 (0.5) | 289 |

| 25 to <60 | 1908 (18) | 14,539 (28) | 16,447 |

| 60 to <75 | 5267 (49) | 23,038 (44) | 28,305 |

| ≥75 | 3599 (33) | 14,652 (28) | 18,251 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 6069 (56) | 30,387 (58) | 36,456 |

| Women | 4752 (44) | 22,239 (42) | 26,991 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 114 (1) | 608 (1) | 722 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 291 (3) | 2471 (5) | 2762 |

| Black | 1948 (18) | 12,462 (24) | 14,410 |

| White | 8268 (76) | 36,828 (70) | 45,096 |

| Unknown/other/missing | 200 (2) | 257 (0.5) | 457 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |||

| Yes | 728 (7) | 6460 (12) | 7188 |

| No | 9925 (92) | 45,684 (87) | 55,609 |

| Unknown | 168 (2) | 482 (0.9) | 650 |

Data are presented as n (%).

Table 2.

Frequency of prevalent comorbidities for patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients without AKI on incident dialysis in 2017

| Top 5% Prevalent Comorbidities in Patients with AKI Requiring Dialysis, n=10,821, % | Prevalent Comorbidities in Patients on Incident Dialysis,a n=52,626, % | Clinical Classification Software Condition Group |

|---|---|---|

| 60 | 43 | Diabetes mellitusb |

| 42 | 19 | Respiratory failure |

| 35 | 18 | Atrial fibrillation |

| 31 | 17 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| 28 | 16 | Asthma |

| 21 | 11 | Morbid obesity |

| 21 | 12 | Major depressive affective disorder |

| 19 | 11 | Pulmonary heart disease |

| 18 | 8 | Malnutrition/cachexia |

| 16 | 8 | Chronic skin ulcer |

| 16 | 10 | Peripheral and visceral atherosclerosis |

| 14 | 8 | Cardiomyopathy |

| 14 | 7 | Myocardial infarction |

| 12 | 7 | Coronary atherosclerosis |

| 10 | 3 | Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure |

| 9 | 5 | Sinoatrial node dysfunction |

| 8 | 5 | Dementia |

| 8 | 3 | Cirrhosis of liver |

| 7 | 3 | Pancytopenia |

| 7 | 3 | Aspiration pneumonitis |

| 7 | 3 | Paroxysmal tachycardia |

| 6 | 3 | Atrial flutter |

| 6 | 2 | Ileus and intestinal obstruction |

| 6 | 2 | Other liver disease |

| 5 | 2 | Aortic and peripheral artery aneurysm/venous thromboembolism |

List of prevalent comorbidities for patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis sorted on the basis of the top 5% shown in the patients with AKI requiring dialysis column.

Combines Clinical Classification Software 15 (diabetes without complications), Clinical Classification Software 16 (diabetes with complications), and Clinical Classification Software 88 (long-term current use of insulin).

Clinical Outcomes of Patients with AKI Requiring Dialysis

Table 3 shows that among all patients with AKI requiring dialysis, 7108 (66%) did not recover kidney function and were ultimately classified as having kidney failure during the follow-up period. There were 1681 (16%) patients with AKI requiring dialysis who died without being classified as having long-term kidney failure and 2012 (19%) patients who were presumed to recover kidney function. Almost all patients with AKI requiring dialysis who developed kidney failure were treated with in-center hemodialysis, although 3% did have one or more claims for peritoneal dialysis (compared with 14% of patients requiring incident dialysis). Among patients requiring incident dialysis, 1927 (4%) recovered kidney function by the end of the study period. Among those 1927 who recovered kidney function, 157 (8%) had acute kidney failure listed as the “cause of ESKD” on CMS Form 2728. With regard to the 7108 patients with AKI requiring dialysis who did not recover kidney function, only 9% had acute kidney failure listed as the cause of ESKD on CMS Form 2728, whereas 35% were due to diabetes, 24% were due to hypertension, 8% were due to GN, 0.8% were due to cystic kidney disease, and 22% were other/unknown/missing.

Table 3.

Counts and percentages of patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients without AKI on incident dialysis by clinical disposition in 2017

| COLUMN HEADING | Patients with AKI Requiring Dialysis, n=10,821 | Patients on Incident Dialysis, n=52,626 |

|---|---|---|

| Recovered kidney functiona | 2012 (19) | 1927 |

| Died without kidney failure | 1681 (16) | n/a |

| Developed kidney failureb | 7108 (66) | 52,626 |

| Dialysis | 4669 (43) | 40,035 (76) |

| Transplant | 481 (4) | 1756 (3) |

| Death | 1958 (18) | 10,835 (21) |

| Lost to follow-upc | 20 (0.2) | n/a |

Data are presented as n (%).

Patients with AKI who had no first maintenance dialysis date but did appear in the Enrollment Database and no death date or transplant during the follow-up period. These values are on the basis of different definitions and data sources used to determine recovery in patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients requiring incident dialysis, respectively. This limits the ability for direct comparison between these two groups.

Patients with AKI who had first maintenance dialysis dates during the follow-up period.

Patients with AKI who had no first maintenance dialysis date and were not found in the Enrollment Database during the follow-up period.

Mortality

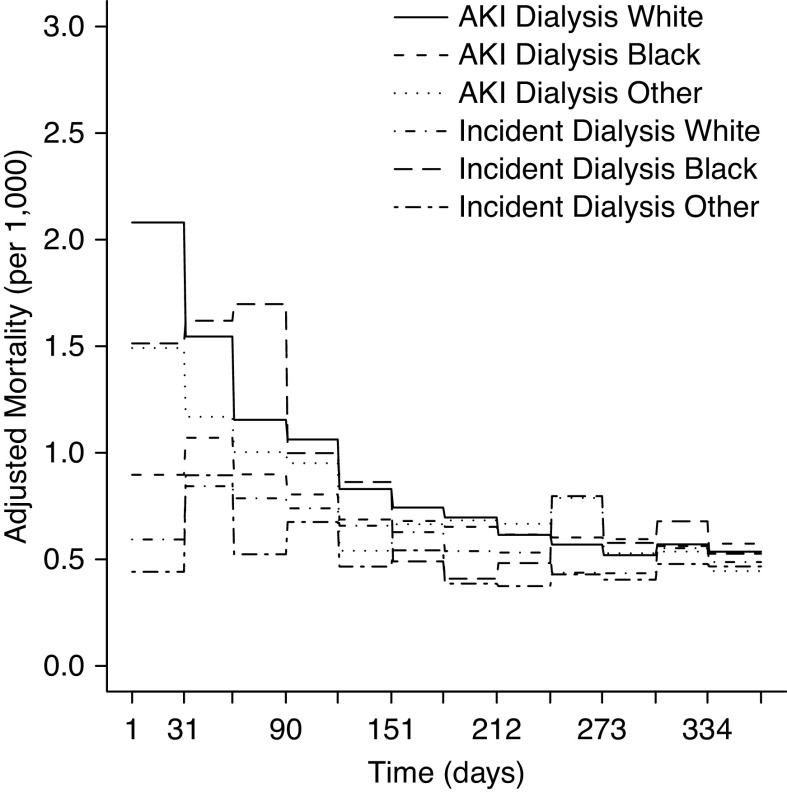

Unadjusted mortality was higher for patients with AKI requiring dialysis when compared with patients without AKI requiring incident dialysis (28% versus 21%, respectively), and patients with AKI requiring dialysis in general had a shorter mean time until death (125.4 days; SD=103.3) from the first AKI claim compared with patients requiring incident dialysis (156.8 days; SD=104.4) from first date of kidney failure. Figure 2 shows unadjusted and adjusted monthly mortality for patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients requiring incident dialysis. Unadjusted monthly mortality rates generally declined over the period for both patient cohorts, but they continued to remain higher for patients with AKI requiring dialysis. Over the first 4 months, adjusted mortality rates for patients with AKI requiring dialysis were 1.95, 1.48, 1.14, and 1.03 per 1000 person-days, respectively, whereas mortality rates for patients requiring incident dialysis were 0.81, 1.02, 0.86, and 0.79 per 1000 person-days, respectively (all P=0.01). By month 7, mortality rates converged and were no longer statistically different.

Figure 2.

One-year unadjusted and adjusted mortality: patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients on incident dialysis.

When stratified by age, adjusted mortality was approximately two-fold higher in each age group for patients with AKI requiring dialysis relative to patients requiring incident dialysis, with differences most pronounced in each of the first 4 months (0.90 versus 0.31, 0.81 versus 0.39, 0.41 versus 0.38, and 0.56 versus 0.40, respectively, for age <60; P=0.01; 1.65 versus 0.70, 1.47 versus 0.91, 1.08 versus 0.76, and 0.97 versus 0.73, respectively, for age 60–74; P<0.001; 2.95 versus 1.32, 1.88 versus 1.63, 1.71 versus 1.38, and 1.45 versus 1.20, respectively, for age 75+; P=0.01) and then converging thereafter (Figure 3). Both patient cohorts aged 75+ had the highest adjusted monthly mortality but more so for patients with AKI requiring dialysis. These differences persisted in most months across the follow-up period.

Figure 3.

One-year adjusted mortality stratified by age: patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients on incident dialysis.

When stratified by race, adjusted mortality was highest for White patients with AKI requiring dialysis who had generally higher adjusted monthly mortality (2.08 versus 0.90, 1.55 versus 1.07, 1.16 versus 0.90, 1.06 versus 0.81, and 0.83 versus 0.69, respectively; P=0.01) each month until month 6 of the follow-up period when rates began to converge with those of White patients requiring incident dialysis, and differences were no longer statistically significant. Black patients and patients of other race had generally lower adjusted monthly mortality compared with White patients, but it was lower among patients requiring incident dialysis compared with patients with AKI requiring dialysis (Figure 4). Differences between patients of other race with AKI requiring dialysis and patients of other race requiring incident dialysis were statistically significant across all months. A similar pattern was observed for Black patients with AKI requiring dialysis and Black patients requiring incident dialysis in all months except months 6 and 11. Among both cohorts, there were small differences in adjusted monthly mortality by sex over the period, whereas no difference was observed between diabetic patients with AKI requiring dialysis and diabetic patients requiring incident dialysis (data not shown). Across the study period, the risk of mortality was 22% higher for patients with AKI requiring dialysis compared with patients requiring incident dialysis (Table 4) (hazard ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.17 to 1.27).

Figure 4.

One-year adjusted mortality stratified by race: patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients on incident dialysis.

Table 4.

Adjusted mortality of patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients without AKI on incident dialysis in 2017

| COLUMN HEADING | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| All patients | |

| Patients with AKI requiring dialysis | 1.22 (1.17 to 1.27) |

| Patients on incident dialysis | Reference |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |

| Yes | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.75) |

| No | Reference |

| Unknown | 1.51 (1.3 to 1.77) |

| Sex | |

| Women | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.01) |

| Men | Reference |

| Race | |

| White | Reference |

| Black | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.85) |

| Unknown/other/missing | 0.70 (0.64 to 0.76) |

| Age on January 1st, 2017, yr | |

| <60 | 0.58 (0.55 to 0.61) |

| 60 to <75 | Reference |

| ≥75 | 1.64 (1.59 to 1.71) |

Separate analyses of adjusted survival between patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients requiring incident dialysis were consistent with the results of the mortality analyses showing slightly higher adjusted survival for patients requiring incident dialysis overall and in the stratified analyses. Survival differences between both patient cohorts also generally declined over the follow-up period. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of vascular access on adjusted mortality because virtually all patients with AKI requiring dialysis used a tunneled catheter. When compared with patients requiring incident dialysis who also used a tunneled catheter at the start of maintenance dialysis, patients with AKI requiring dialysis still had significantly higher early mortality, but survival curves between the two groups converged by 2 months rather than 4 months in the primary outcome.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine if mortality was similar or higher for patients with AKI requiring dialysis compared with patients requiring incident dialysis. Unlike previous research in this area that has been limited in identifying patients with AKI requiring dialysis through the CMS Form 2728 after they have been determined to have long-term kidney failure, we look at this through the framework of CMS policy change in 2017 that allowed patients with AKI requiring dialysis to receive treatment in outpatient dialysis centers before a determination of kidney failure has been made. Although much is known about facility care processes and clinical markers associated with poorer outcomes for patients on maintenance dialysis, there is less information available about outcomes (e.g., survival) for patients with AKI receiving dialysis in Medicare dialysis facilities. A critical assessment of the CMS policy change permitting dialysis reimbursement for Medicare patients with AKI in facilities that provide maintenance dialysis should include evaluation of survival of patients with AKI compared with patients requiring incident dialysis and evaluation of the effect of comorbidity burden on the outcomes.

In our fully adjusted analyses, the mortality risk for patients with AKI requiring dialysis was higher compared with in patients requiring incident dialysis, but differences were observed by age and race within the respective patient cohorts. Overall, adjusted monthly mortality between the two groups was most pronounced through month 4; however, it then converged and was similar for patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients requiring incident dialysis by month 7 of the 365-day follow-up period, suggesting that patients with AKI requiring dialysis who survive the first 6 months may have similar long-term survival outcomes to patients requiring incident dialysis.

There are currently no published studies that compare mortality outcomes among the national population of Medicare patients with AKI requiring dialysis with patients with incident kidney failure receiving outpatient dialysis since the CMS policy change in 2017. However, a recent study using United States Renal Data System (USRDS) data reported similar results to our own, with higher mortality during the first 6 months of dialysis in patients with AKI requiring dialysis compared with patients requiring incident dialysis due to either diabetes or other causes. The study by Shah et al. (15) determined cause of kidney failure from the CMS Form 2728 Medical Evidence form, raising the concern that patients with AKI requiring dialysis who either recovered kidney function or died before reaching kidney failure could not be accounted for in their study. Despite the different methodology, as well as using an earlier cohort of patients prior to the CMS policy change in 2017, they found similar adjusted mortality rates of 28% at 3 months and 16% at 6 months compared with our overall rate of 22% for patients with AKI requiring dialysis relative to patients requiring incident dialysis, observed in the period after the CMS policy change. However, kidney recovery rate of 34% for patients with AKI requiring dialysis at 12 months in their study was almost twice as high as our finding of only 19%. This is noteworthy because some dialysis providers implemented policies in 2017 to provide tailored care for patients with AKI that is different from that provided to patients requiring incident dialysis. For example, weekly monitoring of kidney function for patients with AKI along with more conservative ultrafiltration rates and more frequent interdisciplinary team interactions are all intended to maximize kidney recovery for patients with AKI. Although it is possible that patients in our cohort had more severe AKI accounting for lower rates of recovery, it may also be that prior to 2017, providers had a lower threshold to certify a patient as having kidney failure to facilitate placement in an outpatient dialysis clinic.

Although other observational research has found generally poor outcomes for patients with AKI who are dialysis dependent (3, 16), these typically have been smaller studies, relied on less granular data, or did not have as robust a comorbidity adjustment as this study. For example, Lee et al. (17) found higher risk of short-term mortality and hospitalization for congestive heart failure in patients on dialysis with kidney failure with a prior history of AKI requiring dialysis when compared with patients on dialysis without AKI. In addition, patients with AKI requiring dialysis who recovered kidney function had better outcomes (lower risk of death) compared with patients with AKI requiring dialysis who went on to develop kidney failure. Censoring of patients who died in the first 90 days in that study may explain in part the larger effect size observed when compared with our study that included such patients.

The period of acute care and severity of hospitalization may be predictive of short- and long-term prognosis for patients with AKI requiring dialysis. In addition, vascular access for dialysis may also affect short-term mortality because the vast majority of patients with AKI initiate dialysis with a tunneled catheter, and there are often additional delays in proceeding with a surgical access while awaiting kidney recovery. Thus, differentiating early mortality related to acuity of underlying illness, catheter-related morbidity, or dialysis practice patterns is an unresolved challenge. We observed initial mortality that was consistently higher for patients with AKI requiring dialysis even after comorbidity adjustment, suggesting that the acuity of a hospitalization resulting in AKI requiring dialysis may be a strong driver in primary outcomes for patients who survive to discharge to continue outpatient dialysis. Moreover, over 60% of patients with AKI remained dialysis dependent and progressed to kidney failure after discharge. A few small studies that followed patients with AKI requiring dialysis over a period of time after hospital discharge found generally poorer outcomes and that nonrecovery of kidney function was associated with prior AKI, kidney failure status, baseline kidney function, and dialysis dependence (3, 16, 18, 19). A few other studies looked specifically at rapid decline of eGFR in patients with AKI prior to development of kidney failure and its association with higher mortality (20–22). In contrast, one study using USRDS data reported that recovery of kidney function among patients requiring incident dialysis with prior AKI requiring dialysis was higher when compared with patients requiring incident dialysis who did not have prior AKI (23).

Overall, the poorer outcomes for survival and mortality of patients with AKI on dialysis indicate the severe acuity of AKI, which might result in shorter-term higher mortality and kidney failure incidence as competing risks. This would explain why monthly mortality over time converged between these groups. In other words, patients with AKI requiring dialysis who survive the initial period are at higher risk of developing kidney failure but then experience similar outcomes to patients requiring incident dialysis. These results have implications for care delivery and quality monitoring in the postacute and outpatient dialysis clinic setting.

The CMS policy change in 2017 facilitates hospital discharge of patients with AKI requiring dialysis to outpatient programs. This has the potential to reduce length of hospital stay, and for some patients, allow for dialysis closer to home in facilities designed for outpatient care rather than acute hospital-based units. Despite concerns that were initially expressed about outpatient dialysis facility providers being unfamiliar with the needs of patients with AKI, maintenance dialysis providers were able to recognize when patients with AKI requiring dialysis had regained enough kidney function to discontinue dialysis. However, the absence of national standardized data for all patients with AKI requiring dialysis limits our ability to better track and understand mortality and other outcomes, such as vascular access and recovery of kidney function, in this population. In addition, standardized data collection and reporting may facilitate improved oversight in care and research in outcomes for patients with AKI requiring dialysis who are at higher risk of short-term mortality. Moreover, given the likely increase in patients with AKI who require dialysis over time due to an aging population and in light of the effect of coronavirus disease 2019 infection resulting in more people with impaired kidney function, it is important that CMS continues to support outpatient care for patients with AKI requiring dialysis.

Although we use national CMS claims and administrative data in the immediate period after the 2017 CMS policy change, there are several limitations of our study. First, our analysis is restricted to patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients requiring incident dialysis who are active Fee-for-Service Medicare beneficiaries. To reduce potential bias, we restricted to the Medicare Primary population and excluded non-Medicare patients for whom we have no inpatient or outpatient claims-based information, and those with Medicare Advantage as outpatient claims are not available for this subpopulation. Without these data, we do not know the underlying health status and comorbidity profile of patients with AKI requiring dialysis and patients requiring incident dialysis covered by private insurance, who have no insurance, or who receive care under Medicare Advantage. Studies in the general Medicare population suggest beneficiaries with Medicare Advantage typically have lower utilization and better outcomes than Fee-for-Service beneficiaries (24, 25), and a recent study reported that ESKD beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans had lower mortality and hospital utilization compared with ESKD Fee-for-Service beneficiaries (26).

Another limitation is that we rely on claims data for ascertaining comorbidities. This can potentially bias assessment of comorbidity status because patients who seek health care are likely to be sicker and have more comorbidities reported on claims. However, claims are the primary source for obtaining diagnostic information, and they are used in many large national cohort studies and by registries, such as USRDS. Accounting for prevalent comorbidities likely results in a smaller bias versus not including comorbidity information. Additionally, we followed patients for only up to 1 year; therefore, we do not know how mortality risk and survival patterns might differ beyond that observational time frame.

Because the CMS 2017 policy change may be associated with improved care tailored to patients with AKI requiring dialysis that may reduce risk of mortality after the first few months, future studies should examine other outcomes, such as short- and long-term hospitalization risk, among patients with AKI requiring dialysis compared with patients requiring incident dialysis to better understand disease progression in patients with AKI receiving outpatient dialysis. This might yield information that could inform tailored care plans and monitoring of patients with AKI who receive treatment in outpatient dialysis facilities. Finally, given the observed demographic differences between the AKI and incident dialysis populations by race and sex, further research is warranted to see if these differences have persisted since the policy change and if so, to better understand their potential effects on longer-term outcomes.

Disclosures

S. Chen, J.M. Messana, and W. Wu report employment with the University of Michigan. C. Dahlerus reports employment with the University of Michigan, Department of Internal Medicine, Michigan Medicine and serving as a guest editor for Medical Care for a 2019 supplement on patient-reported outcomes scoring methodologies. K. He and X. Li report employment with the Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center, University of Michigan. A. Pearson reports ownership interest in Anglona Corporation. J.H. Segal reports employment with the University of Michigan Health System and serving on ESRD Network 11 medical review/executive committees. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported through Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Utilization of Data Indicators in the ESRD, Transplant, and OPOs’ Survey Processes contract 500-2016-00085C.

Acknowledgments

The statements in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CMS, although CMS supported the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. CMS did not participate in the study design, analysis, or reporting for this study. Data were obtained from CMS under the contract and associated Data Use Agreement.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Dialyzing Acute Kidney Injury Patients after Hospital Discharge,” on pages 848–849.

References

- 1.Cerdá J, Liu KD, Cruz DN, Jaber BL, Koyner JL, Heung M, Okusa MD, Faubel S; AKI Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology: Promoting kidney function recovery in patients with AKI requiring RRT. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1859–1867, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wald R, McArthur E, Adhikari NK, Bagshaw SM, Burns KE, Garg AX, Harel Z, Kitchlu A, Mazer CD, Nash DM, Scales DC, Silver SA, Ray JG, Friedrich JO: Changing incidence and outcomes following dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury among critically ill adults: A population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 870–877, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rathore AS, Chopra T, Ma JZ, Xin W, Abdel-Rahman EM: Long-term outcomes and associated risk factors of post-hospitalization dialysis-dependent acute kidney injury patients. Nephron 137: 105–112, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heung M: Outpatient dialysis for acute kidney injury: Progress and pitfalls. Am J Kidney Dis 74: 523–528, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Negi S, Koreeda D, Kobayashi S, Yano T, Tatsuta K, Mima T, Shigematsu T, Ohya M: Acute kidney injury: Epidemiology, outcomes, complications, and therapeutic strategies. Semin Dial 31: 519–527, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding JL, Li Y, Burrows NR, Bullard KM, Pavkov ME: US trends in hospitalizations for dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury in people with versus without diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis 75: 897–907, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go AS, Hsu CY, Yang J, Tan TC, Zheng S, Ordonez JD, Liu KD: Acute kidney injury and risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic events. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 833–841, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Heung M, Saran R, Shahinian VB, Pavkov ME, Burrows NR, Powe NR, Hsu CY; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance Team: Exploring potential reasons for the temporal trend in dialysis-requiring AKI in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 14–20, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allegretti AS, Steele DJ, David-Kasdan JA, Bajwa E, Niles JL, Bhan I: Continuous renal replacement therapy outcomes in acute kidney injury and end-stage renal disease: A cohort study. Crit Care 17: R109, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gammelager H, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB, Tønnesen E, Jespersen B, Sørensen HT: Five-year risk of end-stage renal disease among intensive care patients surviving dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury: A nationwide cohort study. Crit Care 17: R145, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickson LJ, Chaudhary S, Williams AW, Dillon JJ, Norby SM, Gregoire JR, Albright Jr. RC, McCarthy JT, Thorsteinsdottir B, Rule AD: Predictors of outpatient kidney function recovery among patients who initiate hemodialysis in the hospital. Am J Kidney Dis 65: 592–602, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao CC, Yang JY, Chen L, Chao CT, Peng YS, Chiang CK, Huang JW, Hung KY: Factors associated with poor outcomes of continuous renal replacement therapy. PLoS One 12: e0177759, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS: Medicare program; end-stage renal disease prospective payment system, coverage and payment for renal dialysis services furnished to individuals with acute kidney injury, end-stage renal disease quality incentive program, durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics and supplies competitive bidding program bid surety bonds, state licensure and appeals process for breach of contract actions, durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics and supplies competitive bidding program and fee schedule adjustments, access to care issues for durable medical equipment; and the comprehensive end-stage renal disease care model: Final rule Fed Regist 81: 77834–77969, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Palmer L; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM, 2019. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed 5/16/2019

- 15.Shah S, Leonard AC, Harrison K, Meganathan K, Christianson AL, Thakar CV: Mortality and recovery associated with kidney failure due to acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 995–1006, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautam SC, Brooks CH, Balogun RA, Xin W, Ma JZ, Abdel-Rahman EM: Predictors and outcomes of post-hospitalization dialysis dependent acute kidney injury. Nephron 131: 185–190, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee BJ, Hsu CY, Parikh RV, Leong TK, Tan TC, Walia S, Liu KD, Hsu RK, Go AS: Non-recovery from dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury and short-term mortality and cardiovascular risk: A cohort study. BMC Nephrol 19: 134, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo LJ, Go AS, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Hsu CY: Dialysis-requiring acute renal failure increases the risk of progressive chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 76: 893–899, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pajewski R, Gipson P, Heung M: Predictors of post-hospitalization recovery of renal function among patients with acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. Hemodial Int 22: 66–73, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu RK, Chai B, Roy JA, Anderson AH, Bansal N, Feldman HI, Go AS, He J, Horwitz EJ, Kusek JW, Lash JP, Ojo A, Sondheimer JH, Townsend RR, Zhan M, Hsu CY; CRIC Study Investigators: Abrupt decline in kidney function before initiating hemodialysis and all-cause mortality: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 193–202, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovesdy CP, Naseer A, Sumida K, Molnar MZ, Potukuchi PK, Thomas F, Streja E, Heung M, Abbott KC, Saran R, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Abrupt decline in kidney function precipitating initiation of chronic renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int Rep 3: 602–609, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hare AM, Batten A, Burrows NR, Pavkov ME, Taylor L, Gupta I, Todd-Stenberg J, Maynard C, Rodriguez RA, Murtagh FEM, Larson EB, Williams D: Trajectories of kidney function decline in the 2 years before initiation of long-term dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 513–522, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, Lee BJ, McCulloch CE, Burrows NR, Heung M, Hsu RK, Pavkov ME, Powe NR, Saran R, Shahinian V, Hsu C-Y; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Kidney Disease Surveillance Team: The relation between dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury and recovery from end-stage renal disease: A national study. BMC Nephrol 20: 342, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beveridge RA, Mendes SM, Caplan A, Rogstad TL, Olson V, Williams MC, McRae JM, Vargas S: Mortality differences between traditional medicare and medicare advantage: A risk-adjusted assessment using claims data. Inquiry 54: 46958017709103, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henke RM, Karaca Z, Gibson TB, Cutler E, Barrett ML, Levit K, Johann J, Nicholas LH, Wong HS: Medicare advantage and traditional medicare hospitalization intensity and readmissions. Med Care Res Rev 75: 434–453, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powers BW, Yan J, Zhu J, Linn KA, Jain SH, Kowalski J, Navathe AS: The beneficial effects of Medicare advantage special needs plans for patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood) 39: 1486–1494, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]