More than half of children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome develop frequent relapses or steroid dependence and require chronic use of immune suppressants, such as cyclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil, or B cell–depleting therapies, to maintain disease in remission (1). Loss of endogenous antibodies in the nephrotic urines and pharmacologic immune suppression contribute to a higher risk for upper respiratory viral infections and influenza in children with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. These infectious episodes may cause or induce relapse of nephrotic syndrome.

This formed the background for the 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines that recommend pneumococcal, annual influenza, and inactivated vaccines, whereas they contraindicate live attenuated vaccines (measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, rotavirus, and yellow fever), especially in patients on immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents (2). Pathogenic mechanisms of nephrotic syndrome are still not fully elucidated, but increasing evidence points at a dysregulation of the immune system, involving both B and T cells. This also raises the intriguing hypothesis that vaccines, by eliciting an immune response, promote disease relapses (3). Overall, previous retrospective analysis reported that influenza virus vaccination in children with nephrotic syndrome is not associated with a higher risk of relapse (4). Similar data are reported for immunization against Streptococcus pneumoniae (3). However, no data from prospective studies are available that test the risk of nephrotic syndrome relapse after vaccines (4,5).

We have prospectively followed up a cohort of 140 pediatric and young adult patients on chronic immunosuppression due to multidrug-dependent nephrotic syndrome. These patients were part of a single-center, randomized controlled trial comparing the safety/efficacy profile of two B cell–depleting antibodies: rituximab and ofatumumab (NCT02394119). After randomization, no other immune-suppressive treatments were allowed. Further anti–B cell–depleting therapy administrations were allowed, but only after disease relapse (i.e., after patients reached their primary end point). Common vaccinations, recommended by the Italian Ministry of Health according to age, were allowed only after 6 months from the anti-CD20 infusion, whereas influenza vaccination was recommended after at least 1 month from infusion. In the study protocol (NCT02394119), vaccinations were not considered as relevant concomitant interventions permitted or prohibited during the trial. Of the 80 patients (74 children [≤18 years] and six young adults [19–24 years]) who had given written informed consent for the use of medical records and for whom a >24-month follow-up period was available, 19 (24%) received a vaccination during the study period. Sex (boys: 61% versus 57%; P=0.08), age (10±10 versus 10±12 years; P=0.10), and type of B cell–depleting antibodies were similar between vaccinated and nonvaccinated individuals, respectively. More in detail, nine subjects received purified influenza vaccines (48%); nine received the diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis vaccine combined with inactivated poliovirus vaccine (48%); and only one patient received the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (5%). No significant differences in terms of age were reported between subjects receiving influenza and diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis vaccine combined with inactivated poliovirus vaccine vaccination. At the time of vaccination (median: 5 months; interquartile range [IQR], 2–10 months after randomization), total B cells fully recovered (median B cells: 6% of total lymphocytes; IQR, 1–11 versus 8%; IQR, 2–15 at randomization; P=0.08).

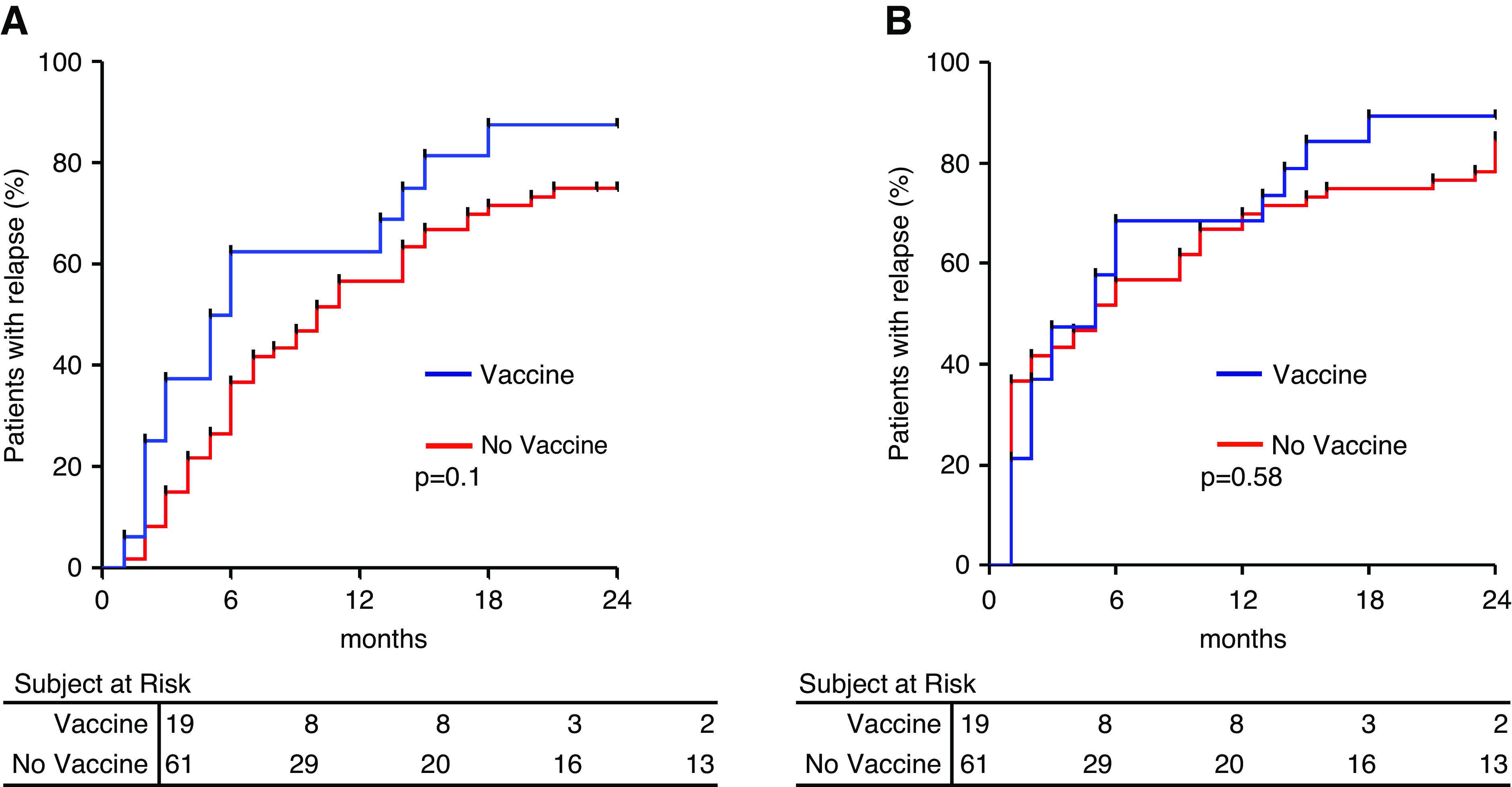

We performed a log-rank test of the hypothesis that vaccines are associated with higher incidence of nephrotic syndrome relapse. In contrast with our hypothesis, we found that, over 24 months of follow-up, 78% of patients experienced a relapse overall: 89% in the vaccination group and 79% in the control group (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.6 to 13.7; P=0.20) (Figure 1A). Within vaccinated patients, there was no difference in the incidence of relapse on the basis of the vaccine type (P=0.10; not shown). Time until relapse was comparable in vaccinated versus nonvaccinated individuals, starting follow-up for vaccinated individuals at the time of vaccination and at 5 months after randomization (median time of vaccination) in the control group (Figure 1B). Vaccines were well tolerated. No disease relapses occurred within 15 days after influenza, but no serologic or swab tests were performed to confirm infection diagnosis. There were no infectious episodes induced by the other pathogens the patients were vaccinated against.

Figure 1.

Vaccines are not associated with a higher risk of nephrotic syndrome relapse. (A) Relapse-free survival by treatment arm: vaccine (blue line) and no vaccine (red line; odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.6 to 13.7). (B) Relapse-free survival considering T0 the time of vaccination in the vaccines group (red line) and 5 months after randomization (median time of vaccination) in the control group (blue line).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective study testing the association between vaccines and relapse of nephrotic syndrome in patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome. The major limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size. However, steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome is a rare disease; therefore, our numbers are still quite informative. Moreover, the fact that only a minority of patients decided to obtain a vaccine suggests that concerns still exist about a potential link with disease relapse. This further supports the importance of our report.

Overall, these data document that administration of vaccines developed by purified proteins is not associated with a higher risk of nephrotic syndrome relapse in patients with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome who received B cell–depleting therapies. Our data are in line with previous studies on the basis of retrospective analysis (4). In absence of specific guidelines for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination for subjects affected by nephrotic syndrome, our data are relevant and could also apply to mRNA vaccines.

Disclosures

A. Angeletti reports employment with Istituto di ricovero e cura a carattere scientifico (IRCCS) Gaslini Pediatric Hospital. M. Bruschi reports employment with the Laboratory of Molecular Nephrology, Istituto Giannina Gaslini. G.M. Ghiggeri reports employment with Istituto Giannina Gaslini IRCCS. F. Lugani reports employment with IRCCS G. Gaslini. C. Montobbio and E. Verrina report employment with IRCCS Istituto Giannina Gaslini. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

For the trial (NCT02394119), G.M. Ghiggeri was supported by Ricerca Finalizzata 2016:WFR: (Italian Ministry of Health) grant PE-2016-02361576.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Ravani P, Rossi R, Bonanni A, Quinn RR, Sica F, Bodria M, Pasini A, Montini G, Edefonti A, Belingheri M, De Giovanni D, Barbano G, Degl’Innocenti L, Scolari F, Murer L, Reiser J, Fornoni A, Ghiggeri GM: Rituximab in children with steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome: A multicenter, open-label, noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2259–2266, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO): The KDIGO practice guideline on glomerulonephritis: Reading between the (guide)lines—application to the individual patient. Available at https://kdigo.org/guidelines/gd/. Accessed May 11, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goonewardene ST, Tang C, Tan LT, Chan KG, Lingham P, Lee LH, Goh BH, Pusparajah P: Safety and efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in pediatric nephrotic syndrome. Front Pediatr 7: 339, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishimori S, Kamei K, Ando T, Yoshikawa T, Kano Y, Nagata H, Saida K, Sato M, Ogura M, Ito S, Ishikura K: Influenza virus vaccination in children with nephrotic syndrome: Insignificant risk of relapse. Clin Exp Nephrol 24: 1069–1076, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes P, Jorge S, Lopes JA: Relapse of nephrotic syndrome following the use of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccine. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 185–186, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]