Abstract

Despite therapeutic gains in the treatment of HER2-positive (HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) advanced/metastatic breast cancer, there remains an urgent need for more effective treatment options. At present, there is no definitive approved standard therapy beyond second-line treatment. One of the major challenges is overcoming treatment resistance. Depending on the underlying resistance mechanism, different strategies are being pursued for new innovative treatment concepts in HER2-positive breast cancer. Specifically designed antibodies for targeted therapy are one important focus to successfully meet these challenges. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd, DS-8201a), an optimised antibody drug conjugate (ADC) is in clinical trials, showing promising outcomes in patients with advanced, nonoperable or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer who had already undergone intensive prior treatment. Based on this data, T-DXd has already been approved in the US and Japan for HER2-positive advanced nonoperable and metastatic breast cancer – in the US after at least two prior anti-HER2 targeted treatment lines and in Japan after prior chemotherapy. T-DXd represents successful “antibody engineering”. Since the beginning of the year, T-DXd has also been approved in Europe as monotherapy for inoperable or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer in patients who are pretreated with at least two anti-HER2 directed therapies. This paper presents strategies for improving treatment options in advanced nonoperable and metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, with the development of T-DXd as an example.

Key words: metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer, HER2-targeted treatment options, antibody, antibody-drug conjugate, T-DXd, DS-8201

Introduction

About one in five breast cancer patients is HER2-(human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-)positive (HER2+). HER2 positivity is assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and/or in situ hybridisation (ISH) 1 . It is defined as IHC 3+ or IHC 2+ /ISH+ and is usually associated with aggressive tumour biology. Most HER2+ breast cancers therefore exhibit an increased rate of proliferation and metastasis 2 . The development and introduction of targeted substances that specifically bind to the HER2 receptor on the tumour cells and thus block the HER2 signalling pathway, which is important for the proliferation of tumour cells, has succeeded in significantly improving the prognosis in this group of patients. In early breast cancer not yet metastasised, this translates into a higher cure rate, including a high rate of long-term survival, and in advanced nonoperable and metastasised HER2+ breast cancer, the risk of progression is significantly reduced and the median overall survival has improved to more than five years.

In addition to the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab, dual antibody blockade with trastuzumab plus pertuzumab – in each case combined with preferably taxane-based chemotherapy – as well as the antibody drug conjugate (ADC) trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) have established themselves as effective treatment options in HER2+ breast cancer. The HER1/HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib is one option for later lines of treatment in the metastatic setting 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 .

Despite the therapeutic gains made in HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (MBC), there is still a need for effective treatment options. At present, there is no definitive approved therapeutic standard for the continued treatment of patients with HER2+ MBC beyond second-line treatment. In addition, pertuzumab and T-DM1 are also administered in the (neo)adjuvant and post-neoadjuvant settings. This raises the question of the continued treatment of these patients in case of a short recurrence-free interval in metastasised disease. Clinical experience suggests that patients with HER2+ breast cancer who relapse on treatment with the now established HER2-targeted agents and regimens often experience an unfavourable course: Up to one third of patients relapsing and developing metastases after (neo)adjuvant trastuzumab/pertuzumab treatment already have CNS metastases as part of the initial metastasis 7 . After failure of post-neoadjuvant T-DM1 therapy, this figure climbed to over 50% of patients initially metastasised 8 .

Challenge: Treatment resistance and inadequate response

The big challenge in oncology is drug resistance mechanisms. The aim is to better understand these mechanisms and overcome them with specific agents and strategies. The HER2 signalling pathway, for example, is an integral part of a complex biological network with other signalling pathways and corresponding “crosstalks”. The development of resistance to HER2-targeted substances therefore is due to various causes, e.g., somatic mutations at the HER2 receptor, a permanently activated truncated HER2 receptor without extracellular domain or simply low HER2 expression. Alternative signal transduction pathways (e.g. PI3K, Akt, mTOR) may be upregulated and serve as so-called “escape” mechanisms for the tumour. Due to the numerous interactions between signalling pathways, deregulation of adjacent signalling pathways (e.g. PI3K, Akt, mTOR) may also induce resistance to HER2-targeted agents 9 , 10 .

Since immunological mechanisms such as the activation of immune effector cells play an important role in the therapeutic efficacy of anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies, genetic polymorphisms in these cells may also affect and, for example, reduce treatment efficacy. This applies, for example, to polymorphisms in the Fc (fragment-crystallisable) receptors. The latter are membrane receptors for different immunoglobulin (Ig) isotypes binding to the Fc domain of an antibody. Depending on the cell type, binding triggers different mechanisms of immune response, for example antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) or antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP). Certain Fc polymorphisms, for instance, result in reduced ADCC 11 , 12 .

Clinical Approaches to Optimising Treatment

Depending on the underlying mechanism of resistance, different strategies are being pursued to overcome resistance mechanisms in HER2+ MBC.

New treatment options with tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) selectively inhibit specific deregulated tyrosine kinases that play a role in tumour development. This then can interrupt unwanted intracellular signal transmissions which play a role in the subsequent pathogenesis of the tumour. TKIs therefore have a much more specific effect than cytostatic agents. The different TKI groups are classified according to the point of attack and protein targeted. Tucatinib and neratinib are two new promising TKIs in the treatment of HER2+ MBC.

Tucatinib

Tucatinib is a new low molecular TKI targeting HER2 that, when combined with trastuzumab plus capecitabine, is showing promising trial data in the randomised trial HER2CLIMB on HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients who had undergone intensive prior treatment. In contrast to patients in the control arm treated with trastuzumab/capecitabine alone, tucatinib prolonged median progression-free survival to 7.8 months (vs. 5.6 months; HR 0.54; p < 0.001) and overall survival to 21.9 months (vs. 17.4 months; HR 0.66; p = 0.005) 13 . Patients with brain metastases benefited to the same extent as those without 13 , 14 . In the US, the triple combination with tucatinib has been approved for patients with advanced HER2+ breast cancer since April 2020 and in Europe since the beginning of 2021 15 , 16 .

Neratinib

Like lapatinib, neratinib is a small molecule. As a pan-HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor, neratinib binds to more than just the one target molecule HER2, but also to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR and HER1) and HER4. Compared to lapatinib, neratinib irreversibly blocks the HER2 signalling pathway 17 . Neratinib has been approved for the extended adjuvant treatment of hormone receptor-positive (HR+) and HER2+ breast cancer and is currently in clinical trials in HER2+ MBC. The phase III NALA trial 18 in patients with HER2+ MBC who had already received multiple prior treatments found that neratinib plus capecitabine reduced the risk of progression by 24% compared to lapatinib plus capecitabine. The onset of symptomatic brain metastases was delayed in the neratinib arm. Data from a US study group indicate that neratinib increases the probability of response compared to standard HER2-targeted therapies (trastuzumab, lapatinib or T-DM1), especially in HER2+ MBC with a specific gene amplification and coexistent HER2 mutation 19 . SUMMIT 20 , a phase II trial studying patients with HER2-mutated and HR+ MBC who had undergone intensive pre-treatment, combined neratinib with fulvestrant. This combination resulted in objective tumour regression in a good one third (33%) of patients with a median response time of 9.2 months. Patients who had already undergone prior treatment with a CDK4/6 inhibitor also benefited.

Triple-positive breast cancer: Combined chemotherapy with CDK4/6 inhibition

In metastatic triple-positive breast cancer (TPBC) – positive oestrogen and progesterone receptor status (ER+/PR+) plus HER2 positivity (HER2 3+ or HER2 2+ /ISH+) – the additional administration of a CDK (cyclin-dependent kinase) 4/6 inhibitor to endocrine therapy with trastuzumab is being discussed as an effective alternative to chemotherapy plus HER2-targeting agent. CDK4/6-inhibitors inhibit the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases, which play a role in cell cycle control and cell proliferation. In HR+ breast cancer, cyclin D activates CDK4/6 kinases, which phosphorylate and subsequently deactivate the retinoblastoma protein (tumour suppressor protein). Since CDK4/6 inhibition prevents this from happening, the tumour cells can no longer divide and proliferate, but enter apoptosis 21 , 22 . Indeed, there appears to be a complex interplay not only between the cell cycle and ER expression, but also with the HER2 signalling pathway. Evidently the CDK4/6 inhibitors are able to reverse HER2 resistance 23 , 24 . We refer to the monarcHER trial – where the triple combination of fulvestrant/trastuzumab/abemaciclib was superior to combined chemotherapy plus trastuzumab and significantly reduced the risk of progression by 37% (HR 0.63; p = 0.05) 25 .

New option: Continued optimisation of antibody treatment

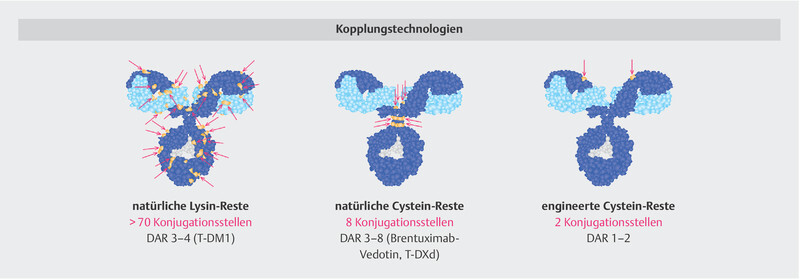

One promising option is antibody engineering. The aim is to use intelligent “engineering” strategies to increase the therapeutic efficacy or specificity of antibody-based treatment. Some particularly promising strategies to optimise antibodies for clinical practice are modified (Fc-optimised) antibodies, bispecific antibodies and technically optimised antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) ( Fig. 1 ) 26 , 27 , 28 .

Fig. 1.

The cytotoxic activity of therapeutic antibodies can be boosted by engineering strategies. Different approaches are being pursued: (1) Fc engineering: Optimisation of the Fc domain through the exchange of amino acids in the protein backbone (e.g. tafasitamab) or modification of the glycosylation pattern (e.g. obinutuzumab). Yellow = amino acid exchange, light grey = sugar structures. (2) Bispecific antibodies for effector cell recruitment, e.g. T-cells (e.g., blinatumomab). (3) Antibody-drug conjugates that, in addition to their natural mechanism of action, transport and deliver a cytotoxic agent to the tumour cell. Pink = linker, purple = toxic agent (so-called payload). PDB structure file provided by M. Clark 28 .

Spotlight on “Antibody Engineering”

Fc engineering

In Fc engineering, the Fc part of the antibody is optimised such that, for example, binding to the Fc receptors on the immune cells is stronger and the immune system is more strongly directed against the tumour or tumour cells. The resulting improved ADCC is said to enhance the immune effect. The reason for this is that it has been shown for trastuzumab that patients with a certain genotype in the Fc receptor respond worse to trastuzumab 29 , 30 , because the Fc part of the antibody only has a low affinity to the Fc receptors on the NK (natural-killer) cells and macrophages. One example of an Fc-optimised HER2 antibody in HER2+ breast cancer is margetuximab. In the randomised phase III study SOPHIA 31 , combined margetuximab/chemotherapy prolonged the median PFS in direct comparison with trastuzumab/chemotherapy, but so far does not demonstrate a convincing survival benefit. However, exploratory analysis of patients with a specific Fc polymorphism (Fcγ receptor III a [FCG3A] or CD16A genotype) revealed a survival benefit compared to treatment with trastuzumab which, however, was not statistically significant. Patients with CD16A-158F allele (85% of patients in the trial) survived a median 23.7 months in the margetuximab arm versus 19.4 months in the trastuzumab arm (p = 0.087). In contrast, homozygous patients with the CD16A-158VV allele (15% of patients in the trial) did not benefit from margetuximab versus trastuzumab 31 .

Bispecific antibodies

Bispecific antibodies comprise two (or more) antigen-recognising components and can thereby bind to two (or more) target structures. The rationale for the development of bispecific antibodies is that several signalling pathways play a role in the pathogenesis of malignancies. Moreover, bispecific antibodies can be used to establish cross-linking between the tumour and certain components of the immune system, especially the T-cells. T cells usually do not have Fc receptors, which is why they cannot be recruited with a monoclonal antibody. With bispecific molecules, it is possible to bind tumour cells to immune cells quasi physically and to activate the patientʼs own immune system 27 .

Bi-specific monoclonal antibodies, so-called BiTE (Bi-specific T-cell engagers), have already demonstrated their benefit in the treatment of some tumour entities. They comprise two scFv fragments, each consisting of the two variable domains of a conventional monoclonal antibody linked by peptide bridges. One scFv fragment binds to a T cell surface protein, usually the CD3 receptor. The second scFv fragment is directed against a surface protein that is expressed as selectively as possible on the target cell. The binding connects one target cell to one T-cell at a time. This activates the T cell and it begins to release cytotoxic proteins inducing programmed cell death and destroying the target cell. The first BiTE antibody employed therapeutically is blinatumomab. It targets the CD3 receptor of T cells and the surface protein CD19 on B cells and is approved as a second-line treatment in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) 32 .

Antibody-drug conjugate (ADC)

ADCs are already being used successfully in clinical practice. The ADC T-DM1 has become the standard of care for second-line treatment of HER2+ MBC after trastuzumab/pertuzumab failure 5 . By now, trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd, DS-8201), a new–optimised–ADC generation, is in clinical trials in HER2+ MBC. The drug has already been approved in the US, Japan and Europe based on convincing phase II clinical trial data 33 , 34 , 35 .

The Need for Optimising Antibody-Drug Conjugates

ADC development is based on tumour-associated antigens (TAA) such as the HER2 receptor, which is expressed on the tumour cell and plays a crucial role in the oncogenesis and pathogenesis of the disease. With specific antibodies that bind to these TAAs, on the one hand the TAAs are blocked, which interrupts the signalling pathways essential for tumour growth, and on the other hand cytotoxic substances can be introduced into the tumour cell, resulting in its death. ADCs are rather complex molecules that take advantage of this. They consist of a tumour-specific, human or humanised monoclonal antibody, a cytotoxic drug (so-called payload) and a linker. The linker binds the cytotoxic drug to the antibody, which transports the drug to the target cell (e.g., HER2+ tumour cell). There, the antibody plus payload binds to the TAAs on the cell surface. This complex is internalised by endocytosis. Then the cytotoxic drug is released within the cell by enzymatic cleavage ( Fig. 2 ) 34 , 36 . In order not to induce systemic (“off-target”) toxicity, the linker technology must ensure a stable bond between the antibody and the drug on its way to the tumour cell 36 – 41 .

Fig. 2.

The free ADC binds specifically to the antigen receptor on the surface of the target cell (tumour cell). Binding to the antigen results in receptor-mediated endocytosis (internalisation). The ADC enters the endosome. The cytotoxic drug (payload) is released intracellularly. In linkers that cannot be cleaved, the payload is released via lysosomal “trafficking” – the ADC complex is degraded by lysosomal enzymes. Since the linker cannot be cleaved, in this case the linker plus one amino acid of the antibody will still be attached to the payload. Linkers that can be cleaved, on the other hand, are cleaved off thereby releasing the pure active ingredient. By detaching the linker, the payload does not have a linker component. As soon as the payload is released, it binds to the intracellular target and induces cell death (apoptosis) 38 .

Despite the successful introduction of the first ADCs into clinical practice, there is a need for optimisation to increase specificity and efficacy, to further minimise the risk of systemic side effects, and to overcome ADC resistance. All three components of the ADC molecule – antibody, linker and toxic payload – provide starting points for further optimisation along the lines of so-called “antibody engineering”. The aim is to develop a highly specific ADC complex that is as homogeneous, stable and potent as possible.

Starting Points for ADC Optimisation

Monoclonal antibody (mab)

Not every antibody is suitable for transporting the cytotoxic drug. A human or humanised antibody is needed to reduce immunogenicity. Moreover, it should be possible to bind a sufficient number of cytotoxic molecules and the antibody must have a high antigen (Ag) specificity and Ag affinity. To ensure intracellular release of the payload, the antibody must have a propensity for internalisation and induce receptor-mediated endocytosis 36 , 37 , 38 , 41 .

IgG1 antibodies, for which intrinsic anti-tumour activity has also been demonstrated, have proven successful. Preclinical trials with different HER2-targeted antibodies have also revealed significant differences depending on the binding domain on the HER2 receptor. Trastuzumab, an IgG1 antibody with biological effector functions, has proven to be very effective in clinical practice and is able to induce immunological mechanisms such as ADCC 38 , 42 .

Linker technology

The linker must ensure high stability of the ADC in plasma to prevent the payload from detaching from the antibody and thereby possibly inducing systemic toxicity. However, it also affects how the cytotoxic active substance is released within the cell. In this respect, the linker has a significant effect on the mechanism of action of the ADC. Linkers are classified as cleavable (e.g., hydrazone, valine-citrulline, disulphide and peptide linkers) and non-cleavable linkers (e.g., thioether moieties) ( Fig. 3 ). Cleavable linkers are sensitive to lysosomal proteases of the tumour cells and acidic pH values or they contain disulphide bridges cleavable by glutathione. The linker remains with the antibody and only the payload is released. In ADCs with non-cleavable linkers, the ADC/AG complex is degraded by proteolysis to release the cytotoxic active substance. This is therefore still linked to the (non-cleavable) linker, the latter still having a lysine or cysteine residue of the degraded antibody attached to it. Since the linker with the amino acid residue is still attached to the released active substance, this reduces the membrane permeability of the active substance – in contrast to an ADC with a cleavable linker 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 43 , 44 .

Fig. 3.

The linker technology of an ADC affects its payload release and efficacy. A distinction is made between ADCs with a cleavable (e.g., T-DXd) or non-cleavable linker (e.g., T-DM1). With a non-cleavable linker, an amino acid residue of the degraded antibody is still attached to the payload, which is why the membrane permeability is lower than with an ADC with cleavable linker 37 , 40 , 43 , 44 .

Cytotoxic active substance (payload)

Since each antibody delivers only a small amount of cytotoxic substance to the target cell (tumour cell), highly potent, possibly optimised cytostatic drugs must be used as a payload. As a rule, these substances are so potent that systemic application – without binding to the antibody – would not be tolerated by the patients. However, due to the stable binding to the antibody and the intracellular release, which only takes place inside the tumour cell, the high efficacy can be used more safely and in a targeted manner. The substanceʼs potency and pharmacokinetics must not be altered by linkage to the antibody. The substance should be sufficiently soluble, as the permeability of the active substance released inside the cell affects the clinical efficacy of the ADC 32 , 33 , 36 .

The choice of cytotoxic agent also plays an important role in circumventing potential ADC resistance mechanisms. MDR1-(multidrug resistance protein 1-)induced resistance, for example, is a common resistance mechanism resulting from upregulated MDR1 expression. The MDR1 protein is an active transporter pumping cytotoxic substances out of the cell. MDR1 is therefore also referred to as the PGP (permeability-glycoprotein) pump. Hydrophobic substances in particular are increasingly channelled out of the cell again, which is why hydrophilic substances should be preferred. Therefore, both the linker and the cytotoxic active substance should be highly hydrophilic 39 .

ADC resistance may also be due to down-regulation of antigen expression or antigen-ADC internalisation, resulting in reduced intracellular degradation of the ADC-antigen complex or release of the payload. In addition, it has been observed that the surface of the tumour cell can effectively renew itself by antigen re-expression 39 . Good permeability of the active substance and good internalisation capacity as well as high potency are therefore crucially important.

Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (T-DXd, DS-8201)

The T-DXd molecule (DS-8201) was specifically developed against the backdrop of this knowledge and optimisation strategy. This may explain why T-DXd demonstrated good efficacy in clinical trials on HER2+ MBC patients who had already undergone intensive prior treatment, with a high response rate and rather long response time. Apparently, T-DXd can overcome HER2 resistance mechanisms that have developed under standard anti-HER2 agents, including T-DM1.

High potency payload

As with T-DM1, T-DXd is a HER2-targeted ADC. The HER2 antibody used – a therapeutic IgG1 antibody – has the same amino acid sequence as trastuzumab. The differences are in the linker technology and the cytotoxic active substance. The toxic agent used for T-DXd is not a microtubule inhibitor, as in many other ADCs, but a new topoisomerase I inhibitor, a derivative of exatecan (DXd). Since DXd is up to 10 times more potent than conventional topoisomerase I inhibitors (active irinotecan metabolite SN 38), it is highly effective. By binding to the antibody and only releasing it within the tumour cell, the high efficacy of DXd can be used in a targeted manner and with good overall tolerance. Moreover, since DXd does not belong to the microtubule inhibitors like the taxanes, resistance to T-DXd is less likely. In addition, since DXd is highly permeable, the payload has good membrane permeability 37 , 45 , 46 .

Tetrapeptide linker with enzymatic cleavage

One important benefit of T-DXd is its innovative linker technology: In the T-DXd molecule, trastuzumab is linked to the toxic active substance via a novel tetrapeptide linker that can be enzymatically cleaved within the cell, but ensures high stability in plasma 46 . After intravenous administration of T-DXd, in vivo pharmacokinetic studies in cynomolgus monkeys reveal an ADC complex with systemic stability in plasma and rapid clearance. T-DXd is detectable almost solely in the blood and only in very small amounts in the tissues. The active substance is excreted primarily in the urine and faeces 47 . Other “in vivo” studies on the good systemic tolerance of T-DXd with doses of up to 197 mg/kg in rats and 30 mg/kg in monkeys support this finding. The substance was applied repeatedly in each case, corresponding to its use in the clinical setting 36 , 37 .

Utilising the bystander antitumour effect

Intracellularly (after the ADC complex has been internalised), the enzymatically cleavable linker allows the cytotoxic active substance to be released as a so-called “naked” or “pure” substance. This yields a molecule with high membrane permeability that can also penetrate and destroy neighbouring tumour cells. The cytotoxic active substance penetrates the neighbouring tumour cells regardless of their HER2 status, leading to the so-called bystander antitumour effect ( Fig. 4 ) 40 . Neighbouring tumour cells with low HER2 expression (HER2 2+ /ISH−) and those that do not express HER2 can also be attacked and destroyed in this way. Moreover, it cannot be ruled out that T-DXd also has an inhibitory effect on immunosuppressive cells in the microenvironment of the tumour or the vessels supplying the tumour.

Fig. 4.

The bystander antitumour effect is based on the high permeability of the active substance (payload), which is not affected by the innovative linker technology 40 .

The bystander antitumour effect described is an important differentiating feature of T-DXd over other ADCs. It requires that the active substance is membrane-permeable, which has been demonstrated in the preclinical model 37 , 44 , 48 . For T-DXd, there is a clear correlation between the bystander antitumour effect and the membrane permeability of the payload. In ADCs with a non -cleavable linker, such as T-DM1, the linker plus an amino acid residue remain attached to the cleaved active substance, so permeability may be lower or non-existent 36 .

High drug-to-antibody ratio

The high potency of the cytotoxic active substance DXd is complemented by a high drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR). The DAR represents the capacity of how much cytotoxic active substance is bound to each individual antibody molecule and can be transported to the target cell. Most ADCs developed so far, including T-DM1, for example, have a DAR of 3 – 4 49 . In other words, one antibody transports 3 – 4 payload molecules. T-DXd, on the other hand, has a DAR of 7 – 8, which is why more cytotoxic active substance can be introduced into the HER2+ tumour cell per antibody ( Fig. 5 ) 37 .

Fig. 5.

Different technologies can be used to link drugs to monoclonal antibodies. Here are three examples: (1) Natural cysteine residues as linkage sites. IgG1 antibodies contain more than 70 lysines that are potentially accessible in a linking reaction. This stochastic process results in a final mixture of hundreds/thousands of different end products (e.g. T-DM1). (2) Linkage via “interchain” cysteine residues. The linkage to cysteine residues involved in the intermolecular disulphide bridges in the natural protein can be used for specific linkage. This results in a more homogeneous end product (e.g. T-DXd, brentuximab vedotin). (3) Additional cysteine residues can also be specifically inserted into the antibody molecule by amino acid exchange, allowing rather targeted linkage. PDB structure file provided by M. Clark 28 .

This is possible due to innovative conjugation technology ( Fig. 5 ). The reduction of cysteine disulphide bridges exposes specific binding sites for the “linker payload”, thus resulting in a homogeneous and stable conjugation (“site-specific conjugation”) 28 , 36 . The innovative conjugation technology reduces ADC hydrophobicity, allowing for higher DAR without compromising stability in plasma. Traditional conjugation technology carries an increased risk of systemic instability and reduced half-life as the DAR increases, which is why previous ADCs had a lower DAR. The preclinical studies on T-DXd show that this innovative conjugation does not affect either antibody function or the effect of the cytotoxic drug (DXd) as a component of the T-DXd molecule 28 , 36 .

Breast Cancer with HER2-low Expression

About 20% of breast cancers are HER2+ (HER2 3+ or HER2 2+ /ISH+) 2 , which by implication means that the majority of breast cancers have little or no HER2 overexpression. About 40 – 50% of breast cancers have HER2-low expression (HER2-low: HER2 2+ /ISH− and HER2 1+ ) 50 , 51 , 52 . In patients with HER2-low expression, the standard HER2-targeted drugs and regimens, including T-DM1, do not have sufficient impact, which is why they are not approved for these cancers. In clinical practice, HER2-moderate and HER2-low expression are an important mechanism of resistance to T-DM1.

With T-DXd it is different: Due to the bystander antitumour effect – high DAR and high membrane permeability of the potent cytotoxic payload – T-DXd can also destroy tumour cells with HER2-low expression. Adequate amounts of toxic payload have also been detected in these tumour cells (HER2 1+ and HER2 2+ /ISH−) to exert an HER2-specific cytotoxic effect 36 , 37 , 53 . Preclinical studies also revealed that DAR plays a minor role in HER2-high expression (HER 3+ and HER 2+ /ISH+), but is important in HER2-intermediate and HER2-low expression (HER 2+ /ISH− and HER2 1+ ) 36 , 37 .

This is also important in clinical practice for HER2+ cancer with HER2 heterogeneity, where tumour cells with HER2-high expression and those with HER2-low expression are present. Studies have shown that the clinical effect of the established HER2-targeted substances is limited if the tumour does not express the target structure homogeneously 54 . HER2-positive gastric cancer is known for a highly heterogeneous HER2 expression. In a phase II/III trial in patients with advanced HER2+ gastric cancer, T-DM1 did not meet the trial endpoint – with HER2 heterogeneity in gastric cancer suggested as a possible reason. Intelligently designed molecules such as T-DXd (bystander antitumour effect) may be able to circumvent the clinical problem of HER2 heterogeneity 37 , 55 . Current data from a phase II trial with T-DXd presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting 2020 confirmed this assumption 56 .

Clinical Data on Trastuzumab Deruxtecan

Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) was approved in the US in late December 2019, in Japan in March 2020 and in Europe since 2021 for the treatment of patients with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer who had already undergone chemotherapy. According to FDA (Food and Drug Administration) approval, metastasised patients must have undergone at least two HER2-targeted therapy regimens in the metastatic setting 57 . The European approval requires that patients with locally advanced and inoperable or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer are pretreated with at least two anti-HER2-directed therapies 35 . The approvals are based on the positive results of the pivotal phase II trial DESTINY-Breast01 58 . Several confirmatory, randomised phase III trials are currently underway worldwide.

Phase I trial data

The phase II pivotal trial was preceded by promising results from a phase Ia/b trial in patients with advanced breast or gastric cancer (incl. tumours of the gastro-oesophageal junction), who had undergone intense prior treatment 46 , 59 . The trial included patients with HER2-low and HER2-high expression. No dose-limiting toxicity was observed during the dose-finding phase (phase Ia). The recommended effective dose of T-DXd was 5.4 and 6.4 mg/kg respectively. During the expansion phase (phase Ib), T-DXd was studied in additional patients at the two recommended dosing regimens (T-DXd 5.4 and 6.4 mg/kg respectively, i. v., every 3 weeks). The published data included a cohort of 115 patients with HER2+ advanced breast cancer who had undergone intensive prior treatment, including T-DM1 59 . This already indicated promising efficacy – also for patients with HER2-low expression.

Objective tumour reduction was achieved in almost 60% of all patients (ORR: 59.5%) with a disease control rate of 93.7%. Patients benefited regardless of HR status, the T-DXd dose administered and whether or not they had already undergone prior treatment with pertuzumab. The median response time was 20.7 months and the median PFS was 22.1 months; the median overall survival time had not yet been reached at the time of analysis 59 . The patients with HER2-low expression (HER2 2+ /ISH−; HER2 1+ ; n = 54) had an objective response rate of 37% and a tumour control rate of 87% – this despite the fact that over half of the HER2-low patients had only been tested HER2 1+ . The median time without progression in HER2-low patients was 11.1 months, with a median overall survival of 29.4 months 60 .

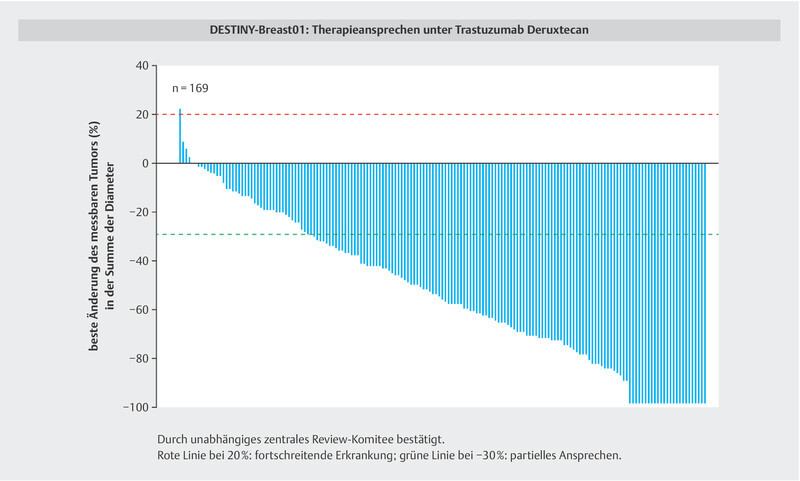

Pivotal phase II trial: DESTINY-Breast01

The first part of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre pivotal phase II study DESTINY-Breast01 58 , 61 tested the pharmacokinetics and T-DXd dosing determined in the phase I trial. T-Dxd monotherapy as 5.4 mg/kg infusion, every three weeks, was confirmed to be effective and well tolerated. A total of 184 patients were treated with this dosage regimen. All patients had nonoperable and/or metastatic HER2+ breast cancer (HER2 3+ ; HER2 2+ /ISH+) and had received a median of six prior treatments. All patients had undergone prior treatment with trastuzumab and T-DM1. More than 60% had also received pertuzumab and just over half had received other HER2-based therapies. Patients with stable brain metastases and prior treatment were also enrolled. The primary endpoint of the trial was the objective response rate (ORR) according to the RECIST criteria (version 1.1), which was confirmed by an independent central review 58 .

Although these were patients with intense prior treatment, the first intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis indicated an ORR of 60.9% (112/184 patients) after a median of 11.1 months, including eleven complete remissions (CR: 6.0%). Only three patients (1.6%) displayed primary progression with a disease control rate (DCR): CR + PR + SD (complete and partial remission plus stabilisation) of 97.3% ( Table 1 ) 61 . The ORR was confirmed in the planned subgroup analysis regardless of whether the patients had already been treated previously with pertuzumab or had brain metastases, and regardless of HR status or HER2 expression level 58 , 61 . The median PFS at that time was 16.4 months for the overall population and 18.1 months for the patients with brain metastases. T-DXd thus also achieves efficacy in the CNS, which is an important observation given the increased incidence of brain metastases after failure following established anti-HER2 therapies.

Table 1 Data on efficacy of T-DXd in the DESTINY-Breast01 trial in patients with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer and intense prior treatment, including T-DM1 (mod. from: 58 , 61 , 62 ).

| Intent-to-treat analysis | August 2019 Mean T-DXd 5.4 mg/kg (n = 184) |

June 2020 Mean T-DXd 5.4 mg/kg (n = 184) |

|---|---|---|

| ORR = objective response rate; ICR = independent central review committee; CR = complete remission; PR = partial remission; SD = stable disease; PD = progressive disease; NR = not reached Median overall survival was estimated at 35% maturity, with 119 censored patients and only 17 patients at risk at 24-months; additional follow-up is needed for more mature data. | ||

| Duration of follow-up (range) | 11.1 months (0.7 – 19.9 months) | 20.5 months (0.7 – 31.4 months) |

| Patients still on treatment | 42.9% (n = 79) | 20.1% (n = 37) |

| ORR confirmed by ICR | 60.9% (n = 112) (95% CI 53.4 – 68.0%) | 61.4% (n = 113) (95% CI 54.0 – 68.5%) |

|

6.0% (n = 11) | 6.5% (n = 12) |

|

54.9% (n = 101) | 54.9% (n = 101) |

|

36.4% (n = 67) | 35.9% (n = 66) |

|

1.6% (n = 3) | 1.6% (n = 3) |

|

1.1% (n = 2) | 1.1% (n = 2) |

| Response time, median | 14.8 months (95% CI 13.8 – 16.9 months) | 20.8 months (95% CI 15.0 months – NR) |

| Time to response, median | 1.6 months (95% CI 1.4 – 2.6 months) | |

| Progression-free survival, median | 16.4 months (95% CI 12.7 months – NR) | 19.4 months (95% CI 14.1 months – NR) |

| Overall survival, median | NR | 24.6 months (95% CI 23.1 months – NR) |

The second, updated ITT analysis confirmed consistent and sustained efficacy after a median follow-up of 20.5 months 62 , with an ORR of 61.4% and a median response duration of 20.8 months. A good 20% of patients were still being treated with T-DXd, including 80 patients (43.4%) for more than 12 months and 11 patients (6.0%) for more than 24 months. Median PFS had increased to 19.4 months. Initial survival data revealed a median overall survival under T-DXd of over two years (24.6 months) with a survival rate at 18 months of 74% ( Table 1 and Fig. 6 ) 62 .

Fig. 6.

In the DESTINY-Breast01 trial, almost all patients with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer benefited from treatment with T-DXd despite intense prior treatment, including T-DM1 58 , 62 .

The updated analysis 62 also confirmed the data on tolerance from the first interim analysis. Most adverse treatment-related events were mild/moderate (grade 1 – 2) in severity. The main symptoms were gastrointestinal complaints, for example, nausea/vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea and/or reduced appetite as well as fatigue and alopecia. The most common adverse event grade ≥ 3 was neutropenia. Cardiac tolerance was good 58 , 61 , 62 . No cumulative adverse events were observed. This also applied to interstitial lung disease (ILD), which – if it occurred – was primarily seen during the first twelve months. During the initial analysis, 25 patients (13.6%) had interstitial lung disease, the majority of which was mild/moderate (grade 1 – 2; NCI CTCAE criteria), but which resulted in death in four patients (grade 5: 2.2%). During the second analysis, three more ILDs were confirmed 62 . Since interstitial lung disease can be treated well with early corticosteroid intervention, patients on T-DXd treatment should be assessed regularly for relevant symptoms. If ILD is suspected, T-DXd treatment must be stopped and treatment with corticosteroids initiated.

Extensive Trial Programme with Trastuzumab Deruxtecan

An extensive trial programme with T-DXd in various solid organ tumours with different HER2 expression levels has been ongoing worldwide. Several randomised phase III trials are currently ongoing in HER2-expressing advanced breast cancer, including trials in patients with HER2-low expression. Other trials are ongoing in HER2+ advanced gastric cancer, HER2+ advanced colorectal cancer (CRC) and HER2+ and HER2-mutated metastatic non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). As part of these trials, T-DXd is also being tested in combination with other oncological therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors 63 .

Trial programme in breast cancer

An extensive trial is validating T-DXd in metastatic breast cancer (DESTINY Breast Trial Programme). This not only includes phase IB/II trials, but also several randomised phase III trials:

DESTINY-Breast02 [NCT03523585]

DESTINY-Breast02 is considered a confirmatory phase III trial of DESTINY-Breast01. Enrolled are patients with nonoperable and/or metastatic HER2+ (HER2 3+ or HER2 2+ /ISH+) breast cancer who had already undergone prior treatment with standard anti-HER2 therapies, including T-DM1. T-DXd will be compared with a HER2-based treatment as chosen by the treating physician (control arm). The primary endpoint of the trial is PFS.

DESTINY-Breast03 [NCT03529110]

The phase III DESTINY-Breast03 trial compares T-DXd directly with T-DM1. Enrolled are patients with nonoperable and/or metastatic HER2+ (HER2 3+ or HER2 2+ /ISH+) breast cancer who had undergone prior trastuzumab/taxan-based treatment. The primary endpoint of the trial is PFS.

DESTINY-Breast04 [NCT03734029]

DESTINY-Breast04, a phase III trial, focuses on patients with HER2-low expression (“HER2-low”: IHC 2+ /ISH− or IHC 1+ ). T-DXd is compared with treatment as chosen by the treating physician (TPC. treatment physicianʼs choice: Capecitabin, eribulin, gemcitabin, paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel). Stratification factors are HER2/IHC status, number of prior chemotherapies and hormone receptor (HR) status. The primary endpoint of the trial is PFS.

DESTINY-Breast05 [NCT04622319]

The interventional phase III trial DESTINY-Breast05, which is running under the sponsorship of the GBG (German Breast Group), is comparing T-DXd with T-DM1 in high-risk patients with early HER2+ breast cancer. These are patients with invasive tumour remnants after neoadjuvant systemic therapy or a primary tumour already nonoperable at initial diagnosis. Primary endpoint of the trial is invasive disease-free survival (iDFS).

DESTINY-Breast06 [NCT04494425]

This phase III trial is validating T-DXd in patients with metastatic or advanced HR-positive (HR+) breast cancer and HER2-low status. All patients have already undergone prior endocrine treatment for advanced/metastatic disease and are in progression. The patients in the control arm receive chemotherapy as chosen by the treating physician – either paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel or capecitabine. The primary endpoint of the trial is PFS.

Outlook

Against the backdrop of clinical challenges, new molecules can be successfully developed and submitted to clinical trials. One such example is the development of T-DXd in HER2-expressing breast cancer. It is necessary to identify additional targets beyond HER2 in order to further specify treatment not only in breast cancer but also in other tumour entities.

Therapeutic algorithms will change significantly against the backdrop of an ever better understanding of tumour pathogenesis and the resulting new therapeutic options. Challenges remain in understanding and overcoming treatment resistance and, especially in HER2-positive breast cancer, the treatment – and possible prevention – of brain metastases. In addition to T-DXd, tucatinib is also a substance with promising trial outcomes 14 , 64 .

One future strategy is to integrate immuno-oncology into HER2-targeted treatment and to combine checkpoint inhibitors and HER2-targeted agents and, if necessary, chemotherapy. Cancer immunotherapy involving the bodyʼs own immune system is a promising concept to circumvent resistance and increase the efficacy of oncological treatment. The first checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for metastatic TNBC. The first trials with immunotherapy are also underway in HER2+ breast cancer – including in combination with HER2-targeted ADCs 38 .

The rationale to combine ADC and checkpoint inhibition is based on preclinical data. According to “in vivo” studies in an immunocompetent mouse model, for example, T-DXd is able to support antitumour immunity and activate the (mouse) immune system. It is suggested that the conjugate increases the number of CD8 T-cells in the tumour and PD-L1 expression on the tumour cells, thereby facilitating PD-L1 blockade 48 , 65 . Clinical trials of combined ADC plus cancer immunotherapy are ongoing in several solid organ tumours with HER2 expression.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by Daiichi Sankyo. The final approval of the contents of the manuscript is the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors would like to thank Birgit-Kristin Pohlmann, Nordkirchen, for her editorial support during the preparation of the manuscript.

Danksagung

Die Manuskripterstellung wurde von der Firma Daiichi Sankyo unterstützt. Die finale Freigabe der Inhalte des Manuskripts liegt in der alleinigen Verantwortung der Autoren. Für die redaktionelle Begleitung der Manuskripterstellung danken die Autoren Birgit-Kristin Pohlmann, Nordkirchen.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt Prof. Diana Lüftner received honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Esai, Genomic Health, GSK, Lilly, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Puma Biotechnology, Riemser, Roche, Tesaro Bio, Teva. Prof. Matthias Peipp received honoraria or research funding from Daiichi Sankyo, Affimed, Merck, Gritstone Oncology, Maxcyte, Inc.

References/Literatur

- 1.American Cancer Society Breast Cancer HER2 Status. Page 27–29Accessed November 19, 2020 at:https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/CRC/PDF/Public/8580.00.pdf

- 2.American Cancer Society Treating Breast Cancer 2019. Targeted therapy for HER2-positive breast cancerPage 56. Accessed April 25, 2020 at:https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/CRC/PDF/Public/8581.00.pdf

- 3.Giordano S H, Temin S, Chandarlapaty S. Systemic therapy for patients with advanced human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: ASCO clinical update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2736–2740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denduluri N, Chavez-MacGregor M, Telli M L. Selection of optimal adjuvant chemotherapy and targeted therapy for early breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2433–2443. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thill M, Friedrich M, Kolberg-Liedtke C. AGO Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Locally Advanced and Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC): Update 2021. Breast Care. 2021 doi: 10.1159/00051620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Früherkennung, Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms. Langversion 4.3 – Februar 2020. AWMF-Registernummer: 032–045OLAccessed April 26, 2020 at:http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom

- 7.Piccart M, Procter M, Fumagalli D. Interim Overall Survival Analysis of APHINITY. A randomised multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing chemotherapy plus trastuzumab plus Pertuzumab versus chemotherapy plus Trastuzumab plus placebo as adjuvant therapy in patients with operable HER2-positive early breast cancer. SABCS 2019, San Antonio/Texas/USA, Dezember 2019. Oral presentation GS1-4

- 8.Geyer C E, Huang C-S, Mano M S. Phase III Study of Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) vs. Trastuzumab as Adjuvant Therapy in Patients with HER2-positive Early Breast Cancer with Residual Invasive disease after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and HER2-Targeted Therapy Including Trastuzumab: Primary Results from KATHERINE. SABCS 2018. San Antonio/Texas/USA, Dezember 2018. Oral presentation GS1-10

- 9.Verniere C, Milano M, Brambilla M. Resistance Mechanisms to anti-HER2 Therapies in HER2-positive Breast Cancer: Current Knowledge, New Research Directions and Therapeutic Perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;139:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larionov A A. Current Therapies for Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients. Front Oncol. 2018;8:89. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veeraraghavan J, De Angelis C D, Reis-Filho J S. De-escalation of treatment in HER2-positive breast cancer: Determinants of response and mechanisms of resistance. Breast. 2017;34 01:S19–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pernas S, Tolaney S M. HER2-positive breast cancer: new therapeutic frontiers and overcoming resistance. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1–16. doi: 10.1177/1758835919833519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murthy R K, Loi S, Okines A. Tucatinib, trastuzumab and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:597–609. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin N U, Borges V, Anders C.Intracranial Efficacy and Survival With Tucatinib Plus Trastuzumab and Capectabine for Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer With Brain Metastases in the HER2CLIMB Trial J Clin Oncol ASCO 2020#1005Accessed November 26, 2020 at:http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.20.00775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accessed May 22, 2021 at:https://www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/novel-drug-approvals-2020

- 16.Accessed May 22, 2021 at:https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/tukysa-epar-product-information_de.pdf

- 17.Collins D M, Conlon N T, Kannan S. Preclinical Characteristics of the Irreversible Pan-HER Kinase Inhibitor Neratinib Compared with Lapatinib: Implications for the Treatment of HER2-Positive and HER2-Mutated Breast Cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:737. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saura C, Oliveira M, Feng Y H. Neratinib + capecitabine versus lapatinib + capecitabine in patients with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer previously treated with ≥ 2 HER2-directed regimens: Findings from the multinational, randomized, phase III NALA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15:suppl.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cocco E, Carmona F J, Razavi P. Neratinib is effective in breast tumors bearing both amplification and mutation of ERBB2 (HER2) Sci Signal. 2019 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aa9773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smyth L M, Piha-Paul S A, Saura C. Neratinib + fulvestrant for HER-mutant HR-positive metastatic breast cancer: Updated results from the phase 2 SUMMIT trial. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. 2018:PD3-06. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS18-PD3-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah M, Nunes M R, Stearns V. CDK4/6 Inhibitors: Game Changers in the Management of Hormone Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer? Oncology. 2018;32:216–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott S C, Lee S, Abraham J. Mechanisms of Therapeutic CDK4/6 Inhibition in Breast Cancer. Semin Oncol. 2017;44:385–394. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goel S, Wang Q, Watt A C. Overcoming therapeutic resistance in HER2-positive breast cancers with CDK4/6 inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:255–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schedin T B, Borges V F, Shagisultanova E. Overcoming Therapeutic Resistance of Triple Positive Breast Cancer with CDK4/6 Inhibition. Int J Breast Cancer. 2018;2018:7.835095E6. doi: 10.1155/2018/7835095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolaney S M, Wardley A M, Zambelli S. MonarcHER: a randomized phase 2 study of abemaciclib plus trastuzumab with or without abemaciclib versus trastuzumab plus chemotherapy in women with HR+, HER2+ advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30 05:v851–v934. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Kong D, Cui Q. Prognostic Genes of Breast Cancer Identified by Gene Co-expression Network Analysis. Front Oncol. 2018;8:374. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu S, Liu Q, Han X. Development and clinical application of anti-HER2 monoclonal and bispecific antibodies for cancer treatment. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2017;6:31. doi: 10.1186/s40164-017-0091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark M R. IgG effector mechanisms. Chem Immunol. 1997;65:88–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musolino A, Naldi N, Bortesi B. Immunglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphismus and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER1/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1789–1796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gavin P G, Song N, Kim S R. Association of Polymorphisms in FCGR2A and FCGR3A With Degree of Trastuzumab Benefit in the Adjuvant Treatment of ERBB2/HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: Analysis of the NSABP B-31 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:335–341. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rugo H S, Im S A, Cardoso F. Phase 3 SOPHIA study of margetuximab + chemotherapy vs. trastuzumab + chemotherapy in patients with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer after prior anti-HER2 therapies: second interim overall survival analysis. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2019. AACR Cancer Res. 2020;80 (4 Suppl.):Abstract GS1-02. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baeuerle P A, Reinhardt C. Bispecific T-cell engaging antibodies for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4941–4944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Accessed November 26, 2020 at:https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-option-patients-her2-positive-breast-cancer-who-have-progressed-available

- 34. ENHERTU ® for intravenous drip infusion 100 mg. Japan Prescibing Information. April 28, 2020

- 35.Accessed May 22, 2021 at:https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/enhertu-epar-product-information_de.pdf

- 36.Ogitani Y, Aida T, Hagihara K. DS-8201a, A Novel HER2-targeting ADC with a Novel DNA Topoisomerase I Inhibitor, Demonstrates a Promising Antitumor Efficacy with Differentiation from T-DM1. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5097–5108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogitani Y, Hagihara K, Oitata M. Bystander killing effect of DS-8201a, a novel anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibody-drug conjugate, in tumors with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterogeneity. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1039–1046. doi: 10.1111/cas.12966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deng S, Lin Z, Li W. Recent Advances in Antibody-Drug Conjugates for Breast Cancer Treatment. Curr Med Chemistry. 2017;24:1–23. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170530092350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nature Reviews. 2017;16:315–335. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trail P A, Dubowchik G M, Lowinger T B. Antibody drug conjugates for treatment of breast cancer: Novel targets and divers approaches in ADC design. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;181:126–142. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakada T, Sugihara K, Jikoh T. The Latest Research and Development into the Antibody-Drug-Conjugate, [fam-] Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (DS-8201a). for HER2 Cancer Therapy. Chem Pharm Bull. 2019;67:173–185. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c18-00744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Goeij . Peipp M, de Haij S. HER2 monoclonal antibodies that do not interfere with receptor heterodimerization-mediated signalling induce effective internalization and represent valuable components for rational antibody-drug conjugate design. Mabs. 2014;6:392–402. doi: 10.4161/mabs.27705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gramatzki M, Peipp M. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH+CoKGaA; 2014. Chapter 7: Fc Engineering; pp. 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuchikama K, An Z. Antibody-drug conjugates: recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries. Protein Cell. 2018;9:33–46. doi: 10.1007/s13238-016-0323-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitsui I, Kumazawa E, Hirota Y. A New Water-soluble Camptothecin Derivative, DX-8951 f, Exhibits Potent Antitumor Activity against Human Tumors in vitro and in vivo. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86:776–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb02468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doi T, Shitara K, Naito Y. Safety, pharmacokinetics and antitumour activity of trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201), a HER2-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with advanced breast and gastric or gastrooesophageal tumours: a phase 1 dose-escalation study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1512–1522. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30604-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagai Y, Oitate M, Shiozawa H. Comprehensive Preclinical Pharmacokinetic Evaluations of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (DS-8201a), a HER2-atrgeting antibody-drug conjugate, in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Xenobiotica. 2019;49:1086–1096. doi: 10.1080/00498254.2018.1531158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iwata H, Tamura K, Doi T. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in subjects with HER2-expressing solid tumors: Long-term results of a large phase 1 study with multiple expansion cohorts. JCO ASCO. 2018;36 15:2501a. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poon K A, Flagella K, Beyer J. Preclinical Safety Profile of Trastuzumab Emtansine: Mechanism of Action of Its Cytotoxic Component Retained With Improved Tolerability. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;273:298–313. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giuliani S, Ciniselli C M, Leonardi E. In a cohort of breast cancer screened patients the proportion of HER2 positive cases is lower than that earlier reported and pathological characteristics differ between HER2 3+ and HER2 2+ /HER2 amplified cases . Virchows Arch. 2016;469:45–50. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-1940-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lal P, Salazar P A, Hudis C A. HER2-testing in breast cancer using immunohistochemical analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization: A single-institution experience of 2,279 cases and comparisons of dual-color an single-color scoring. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:631–636. doi: 10.1309/VE78-62V2-646B-R6EX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schalper K A, Kumar S, Hui P. A retrospective population-based comparison of HER2 immunhistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization in breast carcinomas: Impact of 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists criteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:213–219. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0617-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamura K, Shitara K, Naito Y.Single Agent Activity of DS-8201a, a HER2-targeting antibody-drug conjugate, in breast cancer patients previously treated with T-DM1: phase 1 dose escalation. ESMO 2016 Ann Oncol 2016271–36.LBA 1732645814 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metzger-Filho O, Viale G, Trippa L. HER2 heterogeneity as apredictor of response to neoadjuvant T-DM1 plus Pertuzumab: Results from a prospective clinical trial. ASCO 2019. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37 15:502a. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee H E, Park K U, Yoo S B. Clinical significance of intratumoral HER2 heterogeneity in gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1448–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shitara K, Bang Y J, Sugimoto N. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2419–2430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Accessed April 28, 2020 at:https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761139s000lbl.pdf

- 58.Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:610–621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamura K, Tsurutani J, Takahashi S. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with advanced HER2-positive breast cancer previously treated with trastuzumab emtansine: a dose-expansion, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:816–826. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30097-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Modi S, Park H, Murthy R K. Antitumor Activity and Safety of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Patients With HER2-Low-Expressing Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From a Phase Ib Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Krop I, Saura C, Yamashita T. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Previously Treated With T-DM1: DESTINY-Breast01 Study. SABCS 2019, San Antonio/Texas, USA, Dezember 2019, oral presentation GS1-03

- 62.Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T. Updated Results From DESTINY-Breast01, a Phase 2 Trial of Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (T-DXd) in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. SABCS 2020, Poster-Präsentation PD3-06

- 63.Accessed November 26, 2020 at:http://www.clinicaltrials.gov

- 64.Jerusalem G, Park Y H, Yamashita T. CNS Metastases in HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Treated With Trastuzumab Deruxtecan: DESTINY-Breast01 Subgroup Analyses. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Breast Cancer Virtual Meeting, May 2020. #1380

- 65.Iwata T N, Ishii C, Ishida A. A HER2-Targeting Antibody-Drug-Conjugate, Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (DS-8201a), Enhances Antitumor Immunity in a Mouse Model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17:1494–1503. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]