Abstract

Objective

Professional medical interpreters facilitate patient understanding of illness, prognosis, and treatment options. Facilitating end of life discussions can be challenging. Our objective was to better understand the challenges professional medical interpreters face and how they affect the accuracy of provider-patient communication during discussions of end of life.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with professional Spanish medical interpreters. We asked about their experiences interpreting end of life discussions, including questions about values, professional and emotional challenges interpreting these conversations, and how those challenges might impact accuracy. We used a grounded theory, constant comparative method to analyze the data. Participants completed a short demographic questionnaire.

Results

Seventeen Spanish language interpreters participated. Participants described intensive attention to communication accuracy during end of life discussions, even when discussions caused emotional or professional distress. Professional strains such as rapid discussion tempo contributed to unintentional alterations in discussion content. Perceived non-empathic behaviors of providers contributed to rare, intentional alterations in discussion flow and content.

Conclusion

We found that despite challenges, Spanish language interpreters focus intensively on accurate interpretation in discussions of end of life.

Practice Implications

Provider training on how to best work with interpreters in these important conversations could support accurate and empathetic interpretation.

Keywords: interpreter, accuracy, alteration, end of life, limited English proficiency

1. Introduction

According to the 2010 US Census, 25.2 million people in the United States have limited English proficiency (LEP) and this number has grown 80% since 1990[1]. This growth has important implications for hospice and palliative care as culture and language impact patient understanding of serious illness, prognosis, and end-of-life care options[2–7]. Unfortunately, LEP patients are less likely to understand their diagnosis and associated prognosis[2]. Good communication between providers and patients has been shown to improve end of life care[8]. Empathic communication by providers may even reduce patient physiologic stress and improve recall of serious illness discussions[9].

The founders of the VitalTalk curriculum outline “3 core principles” of serious illness communication [10, 11]. These principles include that 1) responsiveness to emotion is more important than the amount of information a provider relays, 2) information should be relayed in discrete, understandable segments, and 3) treatment plans should center on patient values[10]. These principles align with other guidance for improving medical communication[12–14].

The use of interpreters improves medical understanding and outcomes for LEP patients[5, 15–17]. Access to professional interpreters increases appropriate clinical follow up, reduces preventable emergency department encounters, improves medication compliance, and improves patient satisfaction[5, 15, 16]. All of these benefits were accompanied by only a modest increase in the annual cost of patient care per 2004 cost-benefit analysis[17]. Little is known about how interpreters experience and impact end of life discussions.

In a survey by Schenker et al. interpreters felt discussions of bad news were more likely to “go well” if the medical provider understood the role of the interpreter[18]. Thornton et al. indicated that LEP patients in an ICU may actually receive less medical information than their English proficient counterparts, even when an interpreter is used[19]. Interpreters themselves are known to alter clinical communication[20–22]. Such alterations are of unclear clinical significance and their driving forces are not well understood.

The role of the professional medical interpreter is complex. They are asked to facilitate communication between language incongruent providers, patients, and families while maintaining practice standards of accuracy, confidentiality, impartiality, respect, cultural awareness, role boundaries, professionalism, and advocacy[23]. Hsieh has identified the conflict for interpreters between acting as a neutral conduit while also very intentionally modulating clinical interactions to enhance trust. She calls this an “illusion of a dyadic interaction” between patients and providers and recognizes the complexity of the interpreter role and the prompt professional decisions interpreters make to balance competing demands during a clinical interaction[24].

The National Council on Interpreting in Health Care’s Code of Ethics specifies that an interpreter’s approach to communication should not be influenced by personal values[25]. Providers are held to similar standards of objectivity, but personal experiences and value systems are known to influence the options they offer to patients with serious illness[26–31]. At times, providers may even project their personal preferences or stereotypes onto patients without direct assessment of patient values[32–34]. The degree to which interpreter behavior is altered by similar influences is unstudied.

Although the literature shows that interpreters find EOL discussions emotionally and professionally challenging, it is unknown whether interpreter professional behavior is likewise influenced by their own personal beliefs and biases[18]. Because of the pivotal impact of professional interpreters in improving patient understanding of illness, prognosis, and care options, it is important that we better understand the professional, spiritual, and emotional challenges professional medical interpreters confront in EOL discussions, how they respond to those challenges and how those challenges might result in alterations of clinical communication. Our objective was to explore the factors that drive alterations by professional interpreters during EOL communication.

2. Methods

We used a grounded theory method to explore the ways professional medical interpreters navigate perceived professional, spiritual, and emotional challenges in EOL discussions that might influence interpretation accuracy. Grounded theory allows the application of analytic methods to understand and explain complex social phenomena and relationships arising from participants’ answers to open-ended questions [35]. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the Wisconsin IRB Consortium.

Participant Selection

Participants were required to be professional medical interpreters, age 18 or older, employed or contracted by an accredited medical facility within the prior five years. This temporal limit was to allow recent memory on the part of the interpreter and to accommodate for cultural shifts in the way medical providers discuss EOL. Experience interpreting discussions of EOL decision-making in the final months of a patient’s life was required. Spanish and Hmong language interpreters were invited to participate since these are the two most common non-English languages spoken in the geographic region.

Participants were recruited by emails distributed via institutional interpreter listservs at two academic medical centers in Milwaukee and Madison, WI with permission of their interpreter services managers. The primary investigator attended a face-to-face meeting of one interpreter group to invite participation. Interested interpreters contacted study staff directly to schedule a face-to-face interview.

During the face-to-face encounter, each participant was read an informational letter outlining the purpose of the study, their right to decline to respond to any questions, and the minimal risk involved with study participation. This informational letter was approved by the IRB in lieu of an informed consent document due to the minimal risk associated with study participation.

Participants were offered a small stipend as compensation for their time. Recruitment was stopped at “theoretical saturation,” when no new concepts related to our study questions emerged from the interviews [35].

Data Collection

Interviews

We audio-recorded semi-structured interviews in English. Individual interviews were chosen to allow candid discussion of participant behaviors, values, and emotions while minimizing risk they would impact perception by colleagues. Participants were asked about experiences mediating discussions of EOL decision-making for LEP patients. The interview guide was modified during the study when theoretical saturation was reached on specific concepts and to allow exploration of emergent concepts. This use of “theoretical sampling” is a foundational method of grounded theory [35]. Early interviews explored whether and how professional interpreting experiences challenge participants’ personal beliefs and values, how those challenges might alter their approach to interpretation in EOL discussions, and how interpreters determined whether their personal beliefs and values might be shared by the patient and family (Appendix A). Using an iterative process, questions were later modified to further explore emotional and professional challenges participants identified in EOL discussions and their ways of mitigating these challenges. Participants were specifically asked about influences that might lead to alterations in interpretation. During analysis of the initial 14 interviews, we identified the concept of alterations to the flow of challenging conversations and recruitment was reopened to further explore this concept. We used theoretical sampling to complete an additional three interviews using targeted questions to explore this theme (Appendix B)[35].

Questionnaires

Each participant completed a brief demographic questionnaire containing six questions to collect data on participant age, primary language, interpreted language, years of interpreting experience, and national medical interpreter certification.

Data Analysis

We analyzed the transcribed and de-identified interviews using NVivo Software (QRS International Pty Ltd.). We used a constant comparative method with open coding to analyze the data [35, 36]. M.G.R. read and coded all interviews using emergent categories. Intercoder reliability was calculated as a test of coding integrity. Similarities and differences between concepts were explored, recorded in memos, and used to build larger categories and connections in a process of axial coding. Throughout the coding process, relationships between emergent ideas were diagrammed and discussed between authors. These discussions guided decisions regarding theoretical saturation and emergent themes warranting deeper exploration through theoretical sampling. This process was continued until developed concepts were brought together in a selective coding process to form a final cohesive theory explaining the central phenomenon of participant decision making around alterations to clinical communication[36].

3. Results

Seventeen interviews were completed with professional Spanish language interpreters. Demographic information is shown in Table 1. Fifty-four open codes within 24 subcategories were included in our codebook (Appendix C). Four overarching major emergent categories included “Goal of Accuracy,” “Challenges,” “Mitigating Factors,” and “Alterations.” Participants described a variety of professional and emotional challenges confronted in EOL discussions and the ways these converged to produce intentional and unintentional alterations in conversation flow and content. They did not identify conflicts between personal beliefs and discussion content impacting their approach to accuracy. Our participants focused heavily on their goals of ensuring accuracy. Illustrative passages from our interviews are included for context.

Table 1:

Descriptive Data

| Professional Medical Interpreters (n) | 17 |

| Spanish Language (%) | 100 |

| Female (%) | 82.3 |

| Mean Age (years) | 42.7 (SD 12.4) |

| Mean Experience (years) | 11.1 (SD 7.4) |

| National Certification (%) | 94.1 |

| Frequency of EOL Discussions | |

| At Least Monthly, Less than Weekly (%) | 52.9 |

| Less than Monthly (%) | 47.1 |

Table 1. Demographic information describing study participants.

Maintaining Accuracy

All participants referenced their firm priority of ensuring accurate content and tone of provider-patient-family communication. Participants referenced the strain of their obligation toward accuracy when providers are vague, euphemistic, or unclear in their messages. Despite this strain, they indicated conscious efforts to remain neutral and accurate to the provider’s message rather than alter language in ways they might consider more effective, even when it caused them personal discomfort.

Sometimes the hardest part, I think, is we need to even use the same tone. You wish – sometimes I wish I could just make it like a little softer, you know…that’s hard, but that’s the way it is, right?

Participants referenced being aware of flaws in communication while observing providers sometimes lacked that insight. Occasionally, they described feeling blamed by providers for patient misunderstandings despite their firm emphasis on accuracy.

Because I had one doctor that looked at me like…like…and then okay, I’m just saying what you’re saying, so, if you want a different result, try something different.

Content Alterations

Participants described situations in which maintaining accuracy was challenging or unrealistic due to approaches taken by the provider or family. The risk of unintentional content alterations was generally attributed to the overall tempo of the conversation and interpreter ability to navigate the quantity of speech.

They just keep talking… We’re here to help you out, but you need to help us to kind of…stopped so we can be able to… relay information.

These were often general communication concerns, compounded during discussions of EOL by the involvement of multiple family members. Participants described providers focusing communication with a specific English-speaking family member rather than the patient. In those cases, participants described attempting to continue interpretation of both the provider and family member’s messages without being allowed proper pause. Participants were distressed by content alterations that felt forced in these situations.

The provider starts a conversation with a relative because the relative speaks English. So you’re just in the – the patient is in the background and you’re with the patient in the background so, sometimes you don’t have time to interpret everything. You find yourself summarizing. And then, you are like, okay, so…first of all, who am I to know what’s important in that conversation and what’s not, because I don’t have time to interpret everything. So you’re caught in that position where you have to say… she should probably know this.

References to intentional content alterations were framed as rare and intended to enhance communication or reduce errors when an essential point of communication was missing. These included details such as medication clarification and were not specific to EOL care. These additions of information were framed as transparent communications with the provider and patient.

No participants attributed communication alterations to their personal beliefs or values related directly to the content of EOL discussions.

My opinion doesn’t count. Sometimes I do have a strong opinion, but I don’t express it neither to the providers or the patients.

A few participants described exceedingly rare intentional alterations in response to concerns for patient emotional well-being, especially when they perceived a provider to be exceptionally non-empathic toward a patient or family coping with EOL. These alterations were described when the interpreter felt unable to reject a patient need or unwilling to cross a line of perceived coldness by conveying the provider’s unaltered message. One example involved inserting the words “he said” instead of interpreting in first person.

And I lowered my voice and I said, and this is one of the few times that I said, ‘he said’…I – we’re supposed to do, you know… and I said “he says that, this and that and that and that.”

Another example involved remaining in the patient’s room to offer support and clarity when they felt a provider had abandoned a patient. While alone in the room, the interpreter was no longer interpreting directly for the provider, but instead offering their own insight to the patient related to the clinical news. In rare reports of intentional alterations, two interpreters offered willingness to stake their careers behind their decisions.

I stayed with the patient. I stayed – I – totally, totally, they can say, oh you broke this rule by…yep. Maybe I broke like five rules. You know what? I don’t care. First, is the wellbeing of my patient. First is how my patient is feeling. How is she doing. Maybe – yeah, maybe I broke five administrative rules. Yeah. Punish me. But you know what? That poor woman was bawling.

Flow Alterations

Some interpreters described alterations of conversation flow when patients and families were under emotional strain. Flow alterations include accepting eye contact from patients and families rather than redirecting gaze between a patient and provider to enhance that direct relationship.

The interpreter is supposed to stay away and I try to keep it that way… But when it comes to palliative care… I’ll find that I’m the eye contact person between the patient and family and the doctor… ‘Cuz it’s a very sensitive topic.

At times, participants referenced use of physical contact with patients and families to demonstrate support. In all instances, these were described as intended to support patients and families emotionally without changing discussion content. These flow modifications were emphasized when interpreters did not feel providers offered the emotional connection patients needed in difficult discussions. Participants indicated they felt their interjections were transparent to the providers and patients.

He wasn’t really making eye contact… there was no way I was not gonna make eye contact...

Participants emphasized their preference to remain neutral and unobtrusive if they perceived the provider was meeting the needs of the patients empathetically.

Like when I’m with providers that are empathetic and compassionate, oh gosh no. It’s just like, buttering warm toast. It, just, just falls, uh, you know, it’s as a matter of fact, I could just even shroud my face and let them, you know, it’s just because they lean, and then maybe they might touch somebody or, you know, their voice changes or they might get teary-eyed. I mean, it, it’s very different when it is an empathetic, compassionate medical provider.

Mitigating Challenges to Accuracy

Participants strongly endorsed the value of experience in navigating complex EOL discussions. Several reported prior helpful palliative care-specific training. A few endorsed prior training reinforcing the importance of neutrality, including training aimed at identifying personal “trigger” topics.

He… lays out basically his experiences in the interpreting field and breaking down in the classes…things he teaches you might understand at first, but then when you start and get in those situations you understand why he talked about those things. And so that all helped a lot.

Relationships with providers were perceived as helpful toward minimizing interpretative challenges. Participants appreciated a pre-encounter discussion with the provider to receive a small amount of clinical information and preparation regarding the topics to be discussed during a clinical encounter. Pre-encounter meetings allowed the interpreter to ensure they had allotted adequate time, prepared emotionally, determined physical positioning in the room, and verified anticipated vocabulary. Multiple interpreters referenced a perceived ability to remain more professional and neutral in moments of bad news delivery when they had the opportunity to emotionally prepare prior to the encounter and avoid projecting emotional surprise during the encounter.

But other times you walk in a situation and you don’t even know what’s going on. It’s not until… the conversation starts that you realize, okay, we’re talking about end-of-life. So, yeah…. it will be nice to know ahead of time so you – you prepare yourself mentally because… it can be very stressful.

Interpreters described post-encounter discussions with providers as infrequent. Some interpreters acknowledged the value of having time to provide feedback to providers regarding any patient comprehension concerns or advice on cultural considerations for the next visit.

Theory

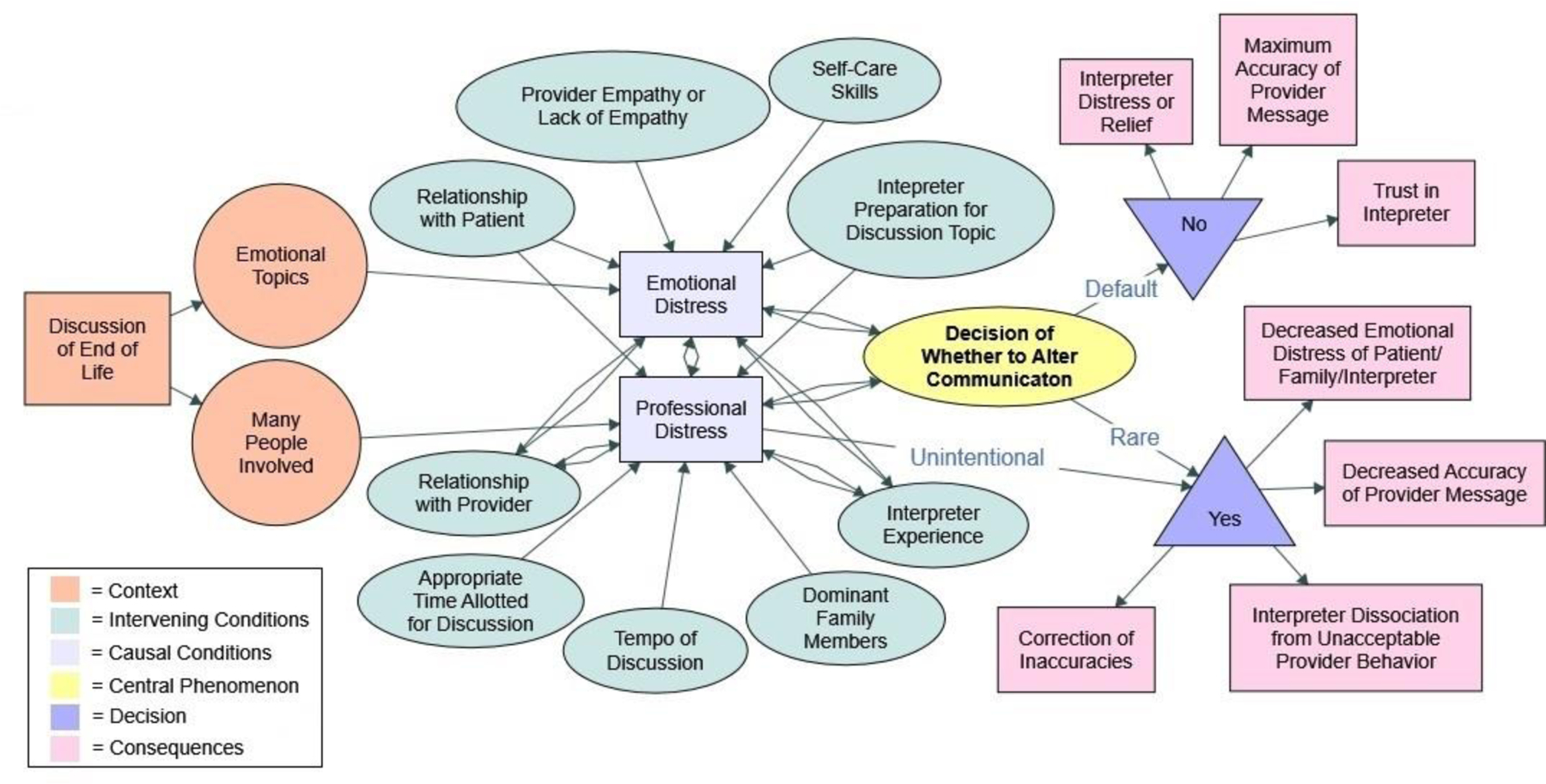

Figure 1 models the complex influences impacting alterations by interpreters in discussions of EOL. In the context of emotion-laden EOL discussions with multiple family members and team members, Spanish language interpreters are impacted by emotional and professional distress related to the discussion topic, provider-interpreter-patient relationships, provider empathy, time constraints, discussion tempo, family member characteristics, interpreter experience level, and self-care skills. These interpreters routinely and consciously choose not to alter communication to keep provider message accuracy and maximize others’ trust in their role. Professional distress may directly result in alterations without conscious interpreter decision making, such as when discussion tempo does not offer adequate time for full interpretation. Rare intentional alterations to EOL communication were largely aimed at decreasing the emotional distress of patients and families while minimizing content modification. Intentional alterations also relieve interpreters by dissociating them from unacceptable, non-empathic behaviors of providers.

Figure 1.

Alterations Theory Model demonstrates the professional and emotional distress that impacts interpreter alterations in the context of EOL discussions. In this model, professional challenges influence unintentional alterations while intentional alterations are rare and impacted by a confluence of emotional and professional distress.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Similar to studies in other settings, we found that Spanish language interpreters overwhelmingly prioritized accuracy during EOL discussions[24, 37, 38]. Participants described holding to unbiased, accurate interpretation even when it led to some form of personal distress. This is consistent with the personal discomfort described by Australian interpreters who prioritized their professional obligation of accuracy while assisting with transitions from oncologic to palliative care[39]. Prior studies have shown that personal distress and associated autonomic activation may impact provider behavior[40].

Silva, et al recently described an “internal conflict” among interpreters struggling to balance accuracy of EOL discussions with cultural values[37]. Hsieh has described the challenge of finding a balance between the “human” and “professional” roles of interpreters[41]. This study builds on those ideas by describing where interpreters might see a boundary between their professional and human obligations in EOL discussions. The clearest boundary presented here is an unwillingness to align with overtly non-empathic providers during EOL communication. Interpreters describe that ethical boundary as a potential driver of volitional alterations in discussion flow and content. They also describe emotional support of patients as a driver of flow alterations without intentional content changes. Injection of emotional support through nonverbal and tonal adjustments in EOL discussions has been previously described[42]. These nonverbal interventions by professional interpreters may promote patient engagement[43].

Recalling the first principle of VitalTalk, which prioritizes emotional responsiveness over information quantity, emotional support work by interpreters may be a positive force in refocusing discussion priorities. The methods and effect of emotional modulation by interpreters of various languages on patient decision making and emotional wellbeing during EOL discussion warrants further exploration. Interpreter approach has been shown to impact patient decision making in other settings[44]. Hsieh et al. caution that emotion work by interpreters may affect patient autonomy, recommending that interpreter decision making be guided by a principle of “quality and equity in care”[41]. The nuanced approaches our participants describe appears to approximate those goals.

Desire to emotionally support patients and disengage from exceptionally nonempathic providers may also be understood as pushing some interpreters from feelings of empathy toward compassionate action[45]. Among diverse health care provider groups, sustained emotional expenditure has been associated with compassion fatigue and resulting decrease in quality of patient care[46]. Emotional arousals may impede provider ability to focus empathy on the patient rather than oneself[47]. Empathy accompanied by self-care and self-awareness are associated with compassion satisfaction[48, 49]. Our participants identified awareness of their motivations when they chose to alter discussion flow or content. Our model suggests infrequent intentional alteration of discussion may have protective benefit to the interpreter although impact on patients is unclear. Although empathy and compassion are widely-valued by caregivers particularly near EOL, acceptable forms of expression are variable between cultures[50, 51].

Notably, most of the identified causes of alterations stemmed from circumstances under the control of the provider. This supports Lor, et al.’s description of alterations being often “initiated by others” or used to enhance the relationships between providers and patients[38]. In both studies, descriptions of rapid discussion pacing and high register word use conflict with the second VitalTalk principle, which recommends information be delivered in discrete segments with comprehensible “headlines”[10]. If rapid discussion pacing limits accurate interpretation, it also heightens concern over whether providers are adequately exploring patient values to align clinical care. Formal provider training to work effectively with interpreters is of known value[52]. Our findings indicate the need for providers who suspect their message is being modified by an interpreter to seek feedback on the clarity and empathy of their own communication. If the cause of any alteration is related to provider communication clarity, speed of discussion, inconsistent use of interpreters, or demonstrations of empathy, seeking the feedback of the interpreter may be the provider’s best method for promptly correcting perceived inaccuracies. Future studies may explore the effect of active interpreter feedback on quality and accuracy of EOL communication, as well as interpreter distress.

The subjective challenges described by our participants could be used to develop measurable outcomes for future study of triggers for alterations in interpreted discussions of EOL. These include 1) a lack of conversational space for accurate interpretation to occur, specifically conversation tempo, quantity of information relayed by provider, and language-congruent exchanges between providers and family members excluding the patient, 2) provider language choice, including vague or high-register word choice, and 3) deficiencies in empathic expressions of providers. Findings by Silva, et al. strengthen concern that medical jargon hampers effective end of life communication through interpreters[37]. This study underscores the potential value in measuring both the verbal and non-verbal alterations that occur with these triggers.

The generalizability of our findings is limited by involvement of only Spanish speaking professional interpreters, geographic location within one Midwestern state, and relatively high interpreter certification level. Interpreters of other languages associated with distinct cultural values, backgrounds, or experiences with discrimination might perceive different challenges in EOL discussions related to their languages themselves, common cultural frameworks, racism, and relationships with health care providers, systems, and decision-making models. Our findings are consistent with challenges described by Spanish and Chinese language interpreters in New York City[37]. Additionally, the nationally certification held by the majority of our study population requires documentation of a high school diploma or equivalent, at least 40 hours of dedicated healthcare-related interpreter training, proof of dual language proficiency, and satisfactory completion of a 100-question multiple choice exam covering the core knowledge of healthcare interpreting[53]. Interpreters with lower levels of professional training may have less consistent approaches to professional role or ability to navigate the complexities of emotion-laden discussions. Future study could explore whether similar priorities and concerns are held by interpreters of more varied backgrounds, languages, geography, and training levels.

The authors also acknowledge the potential for unintentional bias in data analysis given interviews and coding performed by the primary author. Use of intercoder reliability testing was completed to ensure integrity of coding methods and study findings.

4.2. Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest three major sources of verbal and non-verbal alterations by Spanish language interpreters in discussions of end of life. These sources of alterations may occur because of a lack of appropriate conversational space for interpretation, provider language choice, and deficiencies in provider empathic expressions. These factors are heavily influenced by provider communication skills and ability to work collaboratively with professional medical interpreters.

4.3. Practice Implications

Our findings highlight the need for provider training in working appropriately with Spanish language interpreters and demonstrating empathy in certain clinical scenarios. It also substantiates the need to support and train professional interpreters to balance their human and professional obligations in caring for patients at end of life.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Professional interpreters prioritize accuracy even when it causes personal distress

Speed and inconsistent interpreter use hinder accuracy of end of life discussions

Provider empathy may affect accuracy of end of life communication with interpreters

Feedback between interpreters and clinicians may improve end of life communication

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to Dr. David Weissman, Dr. Ryan Spellecy, Dr. Zeno Franco, and Dr. Ruta Brazauskas for early mentorship. Support and engagement by medical interpreters and leadership in Language Services at Froedtert Hospital and Interpreter Services at the University of Wisconsin Hospital were vital to this study. We would also like to acknowledge contributions of Jeanne Tyszka for device support and Nadine Desmarais for transcription.

Funding:

The project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR001436. The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Funding for materials and participant incentives were provided by the Medical College of Wisconsin, Department of Medicine, Faculty Development Award. The funding sources were not involved in project design, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest

None

I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

References

- [1].Pandya C, McHugh M, Batalova J, Limited English Proficient Individuals in the United States: Number, Share, Growth, and Linguistic Diversity, Migration Policy Institute, Washington D.C., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Costas-Muniz R, Sen R, Leng J, Aragones A, Ramirez J, Gany F, Cancer stage knowledge and desire for information: mismatch in Latino cancer patients?, J Cancer Educ 28 (2013) 458–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tchen N, Bedard P, Yi QL, Klein M, Cella D, Eremenco S, Tannock IF, Quality of life and understanding of disease status among cancer patients of different ethnic origin, Br J Cancer 89 (2003) 641–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chan A, Woodruff RK, Comparison of palliative care needs of English- and non-English-speaking patients, J Palliat Care 15 (1999) 26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bhargava A, Wartak SA, Friderici J, Rothberg MB, The Impact of Hispanic Ethnicity on Knowledge and Behavior Among Patients With Diabetes, Diabetes Educator 40 (2014) 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Carrion IV, Cagle JG, Van Dussen DJ, Culler KL, Hong S, Knowledge About Hospice Care and Beliefs About Pain Management: Exploring Differences Between Hispanics and Non-Hispanics, Am J Hosp Palliat Care 32 (2015) 647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Park NS, Jang YR, Ko JE, Chiriboga DA, Factors Affecting Willingness to Use Hospice in Racially/Ethnically Diverse Older Men and Women, Am J Hosp Palliat Me 33 (2016) 770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J, Dying in the hospital setting: A systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important, Palliat Med 29 (2015) 774–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sep MS, van Osch M, van Vliet LM, Smets EM, Bensing JM, The power of clinicians’ affective communication: how reassurance about non-abandonment can reduce patients’ physiological arousal and increase information recall in bad news consultations. An experimental study using analogue patients, Patient Educ Couns 95 (2014) 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Back A, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Communication Skills in the Age of COVID-19, Ann Intern Med 172 (2020) 759–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Back AL, Arnold, Robert, Tulsky, James. VitalTalk. https://www.vitaltalk.org/resources/. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Krupat E, Frankel R, Stein T, Irish J, The Four Habits Coding Scheme: validation of an instrument to assess clinicians’ communication behavior, Patient Educ Couns 62 (2006) 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kurtz SM, Silverman JD, The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes, Med Educ 30 (1996) 83–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Serious Illness Conversation Guide, 2017. https://www.ariadnelabs.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/04/Serious-Illness-Conversation-Guide.2017-04-18CC2pg.pdf. (Accessed 09/25/2020.

- [15].Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S, Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature, Health services research 42 (2007) 727–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA, Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-English-proficient patients, J Gen Intern Med 16 (2001) 468–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jacobs EA, Shepard DS, Suaya JA, Stone EL, Overcoming language barriers in health care: costs and benefits of interpreter services, Am J Public Health 94 (2004) 866–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Kerr K, O’Riordan D, Pantilat SZ, Interpretation for discussions about end-of-life issues: results from a National Survey of Health Care Interpreters, J Palliat Med 15 (2012) 1019–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR, Families with limited English proficiency receive less information and support in interpreted intensive care unit family conferences, Crit Care Med 37 (2009) 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pham K, Thornton JD, Engelberg RA, Jackson JC, Curtis JR, Alterations during medical interpretation of ICU family conferences that interfere with or enhance communication, Chest 134 (2008) 109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, Zuckerman B, Abreu M, Medina L, Hardt EJ, Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters, Pediatrics 111 (2003) 6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jackson JC, Nguyen D, Hu N, Harris R, Terasaki GS, Alterations in medical interpretation during routine primary care, J Gen Intern Med 26 (2011) 259–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ruschke K, Bidar-Sielaff S, Beltran Avery MP, Downing B, Green CE, Haffner L, National Standards of Practice for Interpreters in Health Care, National Council on Interpreting in Health Care, 2005.

- [24].Hsieh E, “I am not a robot!” Interpreters’ views of their roles in health care settings, Qual Health Res 18 (2008) 1367–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Paz Avery M, Alvarado Little W, Michalczyk M, Quinn E, Morris L, Roat CE, Ruschke K, Bidar Sielaff S, Jacobs EA, Chen A, Connell J, Diaz E, Burns J, Martorell S, A National Code of Ethics for Interpreters in Health Care, The National Council on Interpreting in Health Care, 2004.

- [26].Cohen CJ, Chen Y, Orbach H, Freier-Dror Y, Auslander G, Breuer GS, Social values as an independent factor affecting end of life medical decision making, Med Health Care Philos 18 (2015) 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Curlin FA, Lawrence RE, Chin MH, Lantos JD, Religion, conscience, and controversial clinical practices, N Engl J Med 356 (2007) 593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Curlin FA, Nwodim C, Vance JL, Chin MH, Lantos JD, To die, to sleep: US physicians’ religious and other objections to physician-assisted suicide, terminal sedation, and withdrawal of life support, Am J Hosp Palliat Care 25 (2008) 112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hall DE, Curlin F, Can physicians’ care be neutral regarding religion?, Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges 79 (2004) 677–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schenker Y, Tiver GA, Hong SY, White DB, Association between physicians’ beliefs and the option of comfort care for critically ill patients, Intensive Care Med 38 (2012) 1607–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wilkinson DJ, Truog RD, The luck of the draw: physician-related variability in end-of-life decision-making in intensive care, Intensive Care Med 39 (2013) 1128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kai J, Beavan J, Faull C, Challenges of mediated communication, disclosure and patient autonomy in cross-cultural cancer care, Br J Cancer 105 (2011) 918–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Loewenstein G, Projection bias in medical decision making, Med Decis Making 25 (2005) 96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Scheunemann LP, Cunningham TV, Arnold RM, Buddadhumaruk P, White DB, How clinicians discuss critically ill patients’ preferences and values with surrogates: an empirical analysis, Crit Care Med 43 (2015) 757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Glaser BG, Strauss AL, The discovery of grounded theory : strategies for qualitative research, Aldine Publishing, Chicago, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Strauss AL, Corbin JM, Basics of qualitative research : grounded theory procedures and techniques, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, Calif., 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Silva MD, Tsai S, Sobota RM, Abel BT, Reid MC, Adelman RD, Missed Opportunities When Communicating With Limited English-Proficient Patients During End-of-Life Conversations: Insights From Spanish-Speaking and Chinese-Speaking Medical Interpreters, J Pain Symptom Manage (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [38].Lor M, Bowers BJ, Jacobs EA, Navigating Challenges of Medical Interpreting Standards and Expectations of Patients and Health Care Professionals: The Interpreter Perspective, Qual Health Res 29 (2019) 820–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kirby E, Broom A, Good P, Bowden V, Lwin Z, Experiences of interpreters in supporting the transition from oncology to palliative care: A qualitative study, Asia-Pacific journal of clinical oncology 13 (2017) e497–e505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Del Piccolo L, Finset A, Patients’ autonomic activation during clinical interaction: A review of empirical studies, Patient Educ Couns 101 (2018) 195–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hsieh E, Hong SJ, Not all are desired: providers’ views on interpreters’ emotional support for patients, Patient Educ Couns 81 (2010) 192–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Norris WM, Wenrich MD, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Jackson JC, Curtis JR, Communication about end-of-life care between language-discordant patients and clinicians: insights from medical interpreters, J Palliat Med 8 (2005) 1016–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Krystallidou D, Pype P, How interpreters influence patient participation in medical consultations: The confluence of verbal and nonverbal dimensions of interpreter-mediated clinical communication, Patient Educ Couns 101 (2018) 1804–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Preloran HM, Browner CH, Lieber E, Impact of interpreters’ approach on Latinas’ use of amniocentesis, Health Educ Behav 32 (2005) 599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E, Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review, Psychol Bull 136 (2010) 351–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Cavanagh N, Cockett G, Heinrich C, Doig L, Fiest K, Guichon JR, Page S, Mitchell I, Doig CJ, Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Nurs Ethics 27 (2020) 639–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Deuter CE, Nowacki J, Wingenfeld K, Kuehl LK, Finke JB, Dziobek I, Otte C, The role of physiological arousal for self-reported emotional empathy, Auton Neurosci 214 (2018) 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sansó N, Galiana L, Oliver A, Pascual A, Sinclair S, Benito E, Palliative Care Professionals’ Inner Life: Exploring the Relationships Among Awareness, Self-Care, and Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue, Burnout, and Coping With Death, J Pain Symptom Manage 50 (2015) 200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kearney MK, Weininger RB, Vachon ML, Harrison RL, Mount BM, Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “Being connected... a key to my survival”, Jama 301 (2009) 1155–64, e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Singh P, King-Shier K, Sinclair S, The colours and contours of compassion: A systematic review of the perspectives of compassion among ethnically diverse patients and healthcare providers, PLoS One 13 (2018) e0197261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ortega-Galán Á M, Ruiz-Fernández MD, Carmona-Rega MI, Cabrera-Troya J, Ortíz-Amo R, Ibáñez-Masero O, Competence and Compassion: Key Elements of Professional Care at the End of Life From Caregiver’s Perspective, Am J Hosp Palliat Care 36 (2019) 485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Jacobs EA, Diamond LC, Stevak L, The importance of teaching clinicians when and how to work with interpreters, Patient Educ Couns 78 (2010) 149–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].CCHI: Eligibility. https://cchicertification.org/certifications/eligibility/. (Accessed December 13, 2020.)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.